1. Introduction

Mexico is a country with a vast herbal and ethnobotanical heritage, ranked within the four countries with the greatest diversity on the planet is documented that holds between 10-12% of all terrestrial species, and a significant percentage of which are classified as endemic to Mexico. Furthermore, it ranks fifth globally in plant biodiversity with approximately 10,958 vascular plants and 4,702 non-vascular plants, around 10% of the world's flora reported for 2015, of which 4,000 have been identified with therapeutic effects [

1,

2,

3], of which it is estimated that in Mexico, chemical, pharmacological and biomedical validation has only been carried out in 5% of these species [

3].

Randia echinocarpa Moc. & Sessé ex DC. is an endemic shrub species of Mexico belonging to the Rubiaceae family. It’s distributed along the Pacific coast in the conserved tropical deciduous forest [

4]. Present in family orchards, pastures, roadsides, and cultivated areas due to various uses. Commonly known as papache in the Sinaloa state, this plant produces an irregularly structured fruit with edible pulp, which has been used in traditional medicine to treat various diseases such as cancer, malaria, diabetes, and various kidney, lung, circulatory, and gastrointestinal ailments [

4,

5]. The antioxidant, and antimutagenic activities of fractions of the fruit of

Randia echinocarpa were first reported in samples from Sinaloa in 2007 [

6]. In 2014, soluble melanin’s were isolated from the fruit of

R. echinocarpa which showed inhibitory capacity of α-glucosidase activity, exhibiting their possible utility as a retardant in the absorption of carbohydrates in the intestine, to treat type II diabetes [

7]. It has been determined that fruit’s soluble melanin’s exhibit

in vivo antioxidant and immunomodulatory activity and are innocuous, thus they could be used as bioactive ingredients in the formulation of foods, functional supplements, and phyto-therapeutic agents [

8]. Additionally, methanolic extracts of seedlings and calli (mass of undifferentiated somatic plant cells) of

R. echinocarpa have been evaluated, yielding positive results in the scavenging of the DPPH free radical and the ABTS+ cation radical, exhibiting their antioxidant activity [

9]. The various activities (antioxidants, anti-inflammatory, anti-tumor, among others) are attributed to the phenolic compounds in the plant tissues, and recent reports have identified ten phenolic compounds in dry cell biomass and dry supernatants of

R. echinocarpa, with chlorogenic and salicylic acids being the main ones, portraying antioxidant, hypoglycemic, antiviral, analgesic, and anti-inflammatory properties [

10]. The objective of the present study was to determine the phenolic profile and antioxidant capacity of ethanolic extracts from the leaf, bark, and fruit pulp of

R. echinocarpa and to compare these profiles among seasons.

2. Results

2.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

The concentration of total phenolics was determined in fruit pulp, leaf, and bark of

R. echinocarpa dried via lyophilization (0.045-0.090 mbar, -65°C) and oven at 45°C and 75°C. The highest concentration was found in the leaf during the autumn season across all drying methods, while the lowest concentrations were observed in the bark during the winter season for all drying methods (

Table 1).

2.2. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

The concentration of total flavonoids was determined in fruit pulp, leaf, and bark of

R. echinocarpa dried via lyophilization (0.045-0.090 mbar, -65°C) and oven at 45°C and 75°C. The highest concentrations were found in the leaf during the autumn season dried at 45°C, although similar concentrations were found in the winter and spring seasons across all drying methods (

Table 2).

2.3. Condensed Tannin Content (CTC)

The concentration of condensed tannins was determined in fruit pulp, leaf, and bark of

R. echinocarpa dried via lyophilization (0.045-0.090 mbar, -65°C) and oven at 45°C and 75°C. The highest concentrations were found in the leaf during the autumn season, while the lowest concentrations were found in the bark during winter, across all drying methods (

Table 3).

2.4. HPLC/DAD Analysis

The phenolic profile was determined only in leaf and pulp due to the higher concentrations of polyphenols obtained in them in comparison to other tissues and their well-known use in traditional medicine. Five different phenolic compounds were identified in the leaf, and three in the fruit pulp, using HPLC-DAD analysis, as shown in

Table 4. Among the eight phenolic compounds identified, chlorogenic and ferulic acid exhibited the highest concentration, followed by rutin, caffeic acid, and catechin.

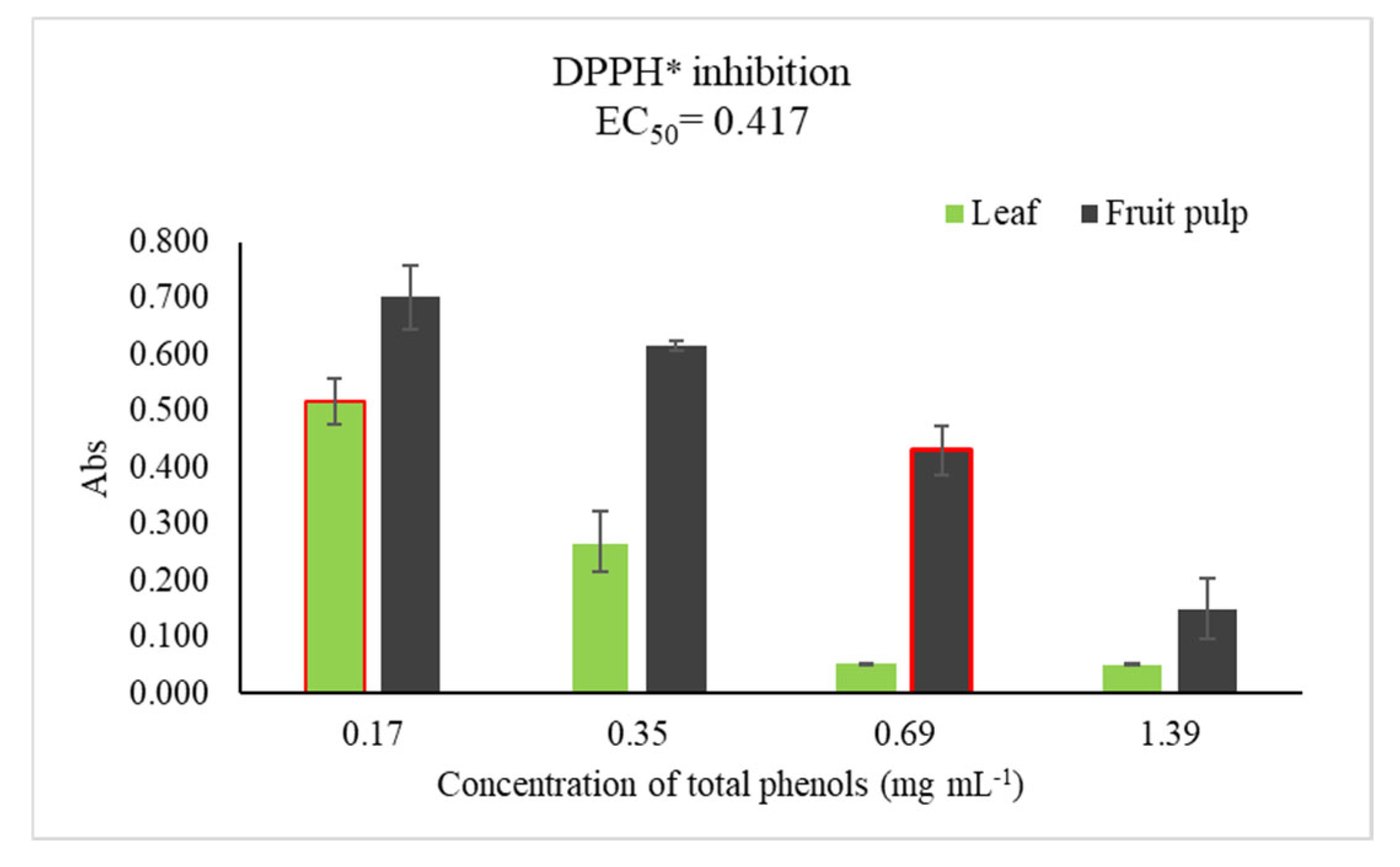

2.5. DPPH* Assay

Since higher concentrations of polyphenols were found in the leaf and fruit pulp, in addition to the fact that they are the parts used in traditional medicine, the antioxidant capacity (AC) was only determined in these two tissues mentioned, both considering the higher concentrations of total phenols found in the autumn season, and the tissues dried at 45°C (

Table 1). The highest AC was found in the leaf extracts, showing the ability to inhibit the DPPH* radical at all the different concentrations, finding its median effective concentration (EC

50) at the lowest concentration (0.17 mg mL

-1), while the pulp showed a lower antioxidant capacity with its EC

50 at 0.69 mg mL

-1 (

Figure 1).

3. Discussion

3.1. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

Some authors have reported similar concentrations of total phenols to this study, such as those found in methanolic (0.64 mg g

-1) and aqueous extracts (2.27 mg g

-1) of the fruit of

Randia echinocarpa [

6]. Moreover others have reported higher concentrations using aqueous extraction at room temperature and aqueous extraction at boiling temperature (4.84 and 6.28 mg g

-1, respectively) [

7]. Recently, lower concentrations (0.9 mg g

-1) were reported in dry cell biomass of

R. echinocarpa, compared to those reported in the present study with extracts of fruit pulp, leaf and bark [

10]. The variations in these concentrations across this and previous investigations could be influenced by harvesting or cultivation season, as well as the specific tissue analyzed, as shown in

Table 1.

3.2. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

Flavonoids are natural pigments in plants that protect against damage from oxidative agents such as UV rays, environmental pollution, pathogens, etc., and over 5,000 different flavonoids have been identified [11-15]. There are studies limited to detect only flavonoids presence but studies on the concentration of flavonoids in

R. echinocarpa are scarce or nonexistent [16-18]. Therefore, this study represents the first report on the concentration of these compounds. Confirming their presence in the phenolic profile via HPLC/DAD, two flavonoid compounds were identified: rutin and catechin (

Table 4).

3.3. Condensed Tannin Content (CTC)

These compounds have some antinutritional effects due to their chemical characteristics, causing a bitter taste and inhibiting proteins and digestive enzymes [

19]. Similar to flavonoids, studies on concentrations of condensed tannin in

R. echinocarpa are scarce or nonexistent, limited to their detection only [

16,

18]. In this study, higher concentrations were found in leaves during the autumn season (Possibly derived as a response to increased temperature), although these concentrations do not pose a significant risk for human health when consumed due to their low levels [

20].

3.4. HPLC/DAD Analysis

Analyses of the phenolic profile of

Randia echinocarpa are extremely scarce; a previous investigation focused on dry cell biomass and dry supernatants of this species, identified 11 phenolic compounds, with salicylic acid and chlorogenic acid being the most concentrated [

10]. Phenolic profiling has also been conducted on species within the same genus, such as

Randia monantha, where fruit pulp and seed were analyzed using ultra-high performance liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry (UPLC-MS-MS), revealing 15 phenolic compounds, with chlorogenic acid and rutin being the most concentrated, respectively [

21]. These studies reveal a similar trend in phenolic compound diversity within the genus Randia. However, other studies on different plant species have reported greater diversity, such as

Maclura tinctoria with 33 compounds in bark extracts [

22] and

Fouquieria splendens with 15 phenolic compounds [

23]. Differences in the number of phenolic compounds found in this study and those mentioned may be due to specific properties of phenolic compounds in response to biotic and abiotic factors. Additionally, the quantity, type, and concentration of phenolic compounds depend on several factors, including plant tissue and developmental stage [

24].

3.5. DPPH Assay

The highest antioxidant capacity (AC) was found in the leaf ethanolic extracts (EC

50 at 0.17 mg mL

-1), while the pulp showed a lower AC (EC

50 at 0.69 mg mL

-1). The AC of both tissues were lower than those reported in another plant species, with hydroalcoholic extracts of

Caesalpinia spinosa pods with an EC

50 at 3.2 µg mL

-1 [

25], although higher than acetone extracts of

Oxalis tuberosa peel with an EC

50 at 5.37 mg mL

-1 [

26]. Similarly, the AC in this study was higher in both tissues than that reported in methanolic extracts of

Randia monantha fruit pulp with an EC

50 a 1mg mL

-1 [

21], the difference in antioxidant capacity could be due, first of all, to the type of plant tissue used, the diversity of antioxidant compounds, as well as the solvent used for the extraction of the compounds, due to the polarity or affinity of the compounds to be extracted with the solvents used. Antioxidants are essential because they can neutralize or stabilize free radicals (ROS), which can cause oxidative stress. In addition, they have been found to possess antimicrobial properties by interfering with protein synthesis and altering the cell membrane, thereby affecting the metabolism of microorganisms [11,12,26-28], furthermore, plants are the main source of bioactive metabolites (e.g., phenolics, quinones, flavonoids, terpenoids and alkaloids), and a relationship between these activities and antioxidant capacity has already been demonstrated [

6,

17,

29].

4. Materials and Methods

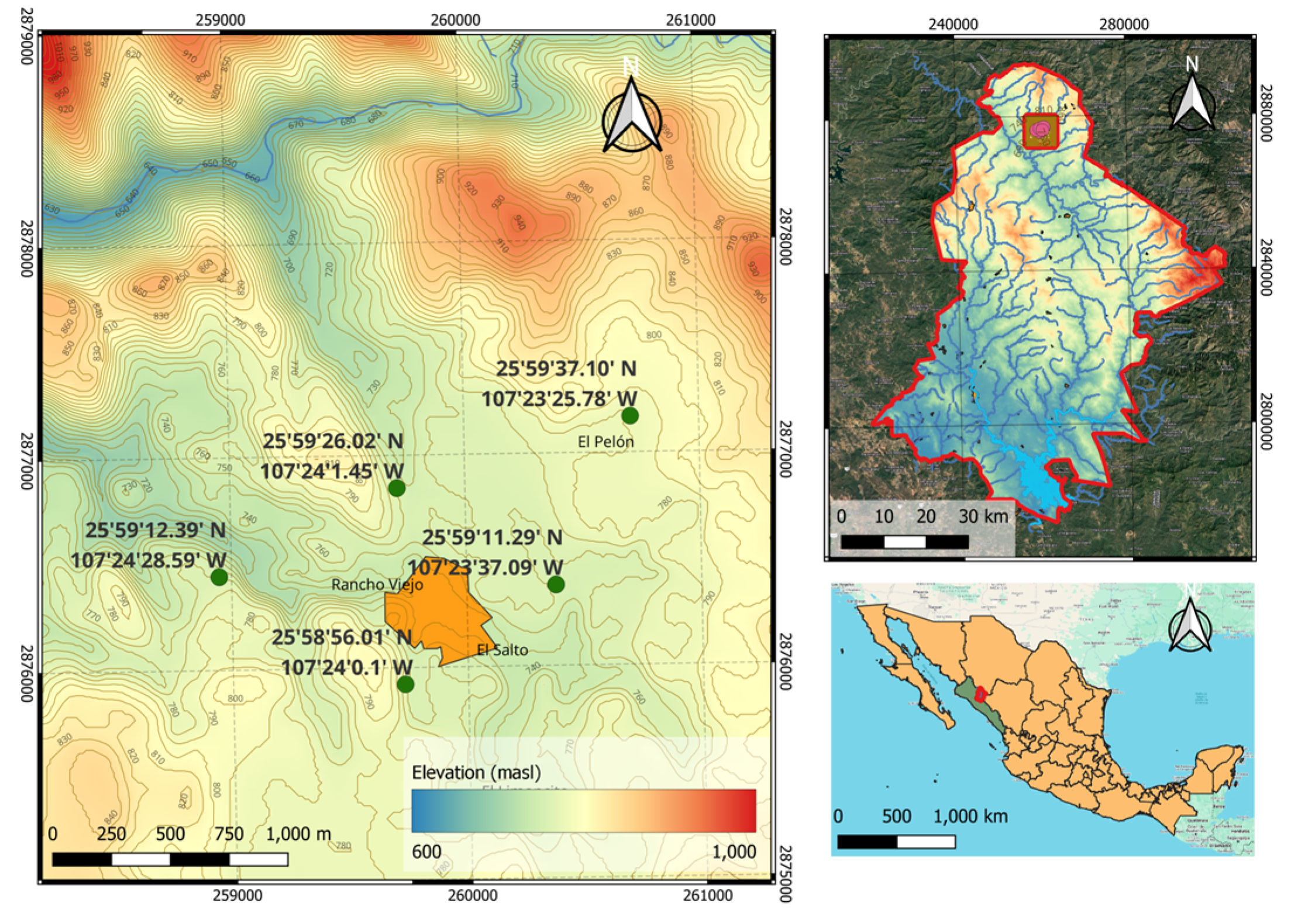

4.1. Sample Collection

Four samplings were conducted over an annual cycle to collect samples of bark, leaves, and pulp from the

Randia echinocarpa plant during 2023. These were collected from five areas (

Figure 2) surrounding the Rancho Viejo community in the municipality of Badiraguato, Sinaloa, Mexico (located: 25°59’14” N, 107°24’04” W at 743 meters above sea level). Healthy tissue from 10 plants was selected, stems with abundant leaves were collected, obtaining an approximate weight of 250 g, which were stored in 50 x 20 cm paper bags. Additionally, 20 mature fruits with an approximate weight of 2.5 kg were collected and stored in 50 x 100 cm black bags.

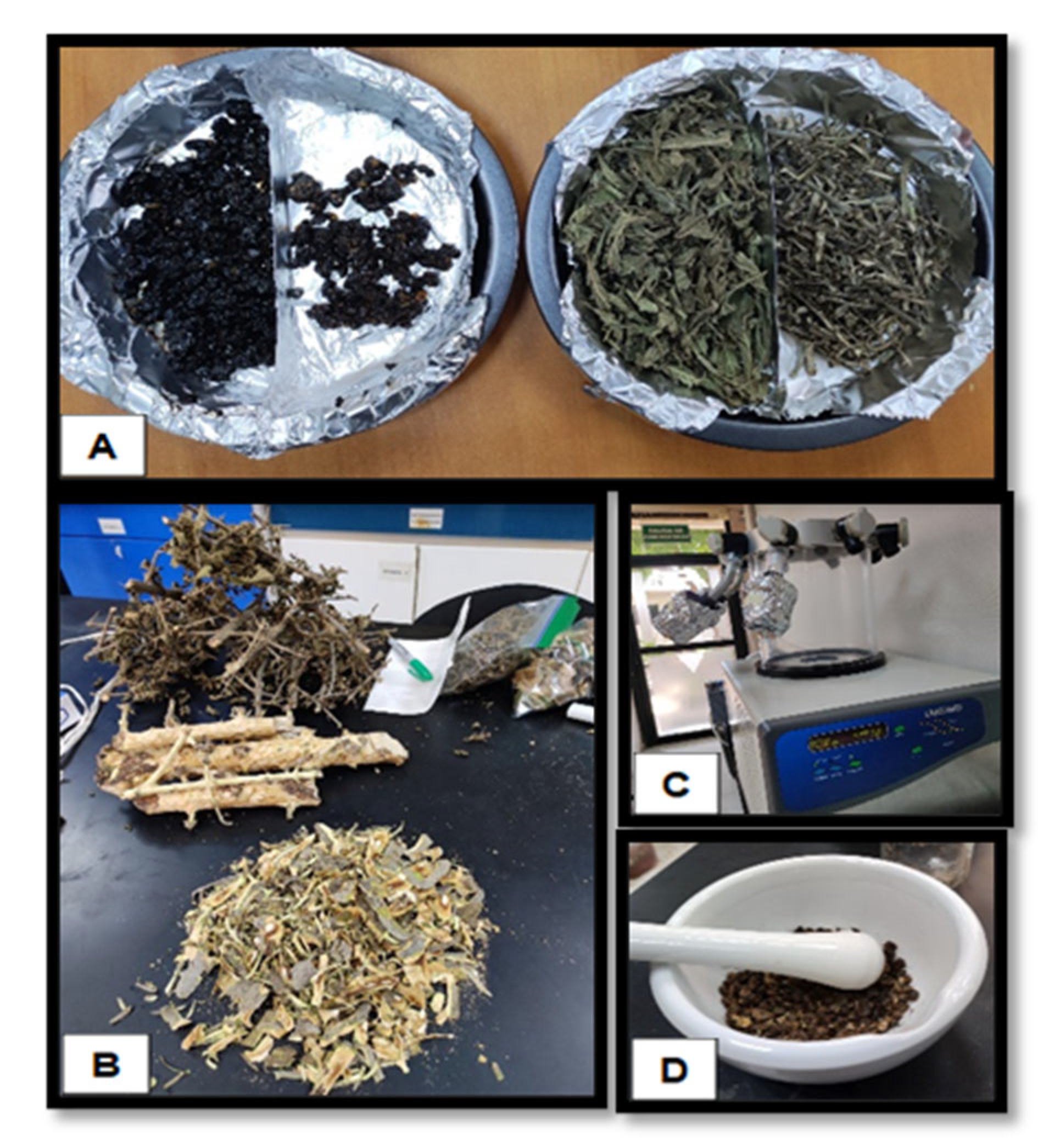

4.2. Sample Processing

The leaves, bark, and pulp were dried using lyophilization (working conditions: 0.045-0.090 mbar and

-85°C) and oven at 45°C and 75°C (from 1 day to 1 week depending on the dried plant tissue) (

Figure 3), taking care to avoid exposure to light to prevent oxidation. Subsequently, they were pulverized using a household blender (Toastmaster). The pulverized samples were reduced to a particle size of less than 1 mm using a hammer mill. The samples were then stored in aluminum-covered jars and kept at ultra-low temperatures at

-80°C until use.

4.3. Extraction of Phenolic Compounds by Ethanol Extraction

One gram of each sample was taken and macerated in 10 mL of 50% ethanol (v/v) (Baker®) for 24 hours at room temperature, in darkness. The resulting extracts were centrifuged at 4,000 x

g for 15 minutes (Eppendorf Centrifuge 5804) and the supernatants were recovered in capped tubes protected from light with aluminum foil [

30].

4.4. Determination of Phenolic Profile and Antioxidant Capacity

4.4.1. HPLC/DAD Analysis

The phenolic profile was determined by direct comparison using high-performance liquid chromatography/diode array detector (HPLC/DAD). One gram of dried tissue was macerated in 10 mL of ethanol-water (50% v/v). The HPLC profile of phenolics in the methanolic crude extract was established with a Dionex UltiMate 3000 liquid chromatograph, equipped with a titanium quaternary pump (LPG-3400 AB), an autosampler (WPS-3000 TBPL), column oven and a photodiode array detector DAD-3000 (RS) (scan range 190–800 nm and scan speed 2 nm s

-1) from Thermo Scientific (Thermo Fisher Scientific, New York, NY, USA). Separation was carried out using an analytical column Acclaim® 120 A (C18, 5 µm, 120 Å, 4.6 X 250 mm), from Dionex (Thermo Fisher Scientific, New York, NY, USA), at ambient temperature. Elution was done with a gradient of two solvents: water acidified with acetic acid (pH 2.8) (A) and acetonitrile (B). The gradient for phenolic acids was 100% phase A, 6% phase B from 0-8 min, 6% to 12% B from 8-14 min, 12% to 20% B from 14-18 min: 20% to 35% B from 18-24 min, 35% to 95% B from 24-27 min, 95% to 100% B from 27-30 min, and 100% B to 100% A in 10 min. The fixed wavelengths were 260, 270, 275, 280, 285, 290, 295 and 300 nm. Gradient for the elution of flavonoids was 100% A, 10% B from 0- 190 2.5 min, 10% to 12% B from 2.5-6 min, 12% to 23% B from 6-18 min, 23% to 35% B from 18-24 min, 35% to 95% B from 24-27 min, 95% to 100% B from 27-30 min, and 100% B to 100% A in 10 min: 260 and 342 nm. The flow rate was 0.5 mL/min. The injection volume was 10 µL. Chromatographic peaks were identified by comparing the retention times and UV Visible absorption of pure standards. Each sample was injected three times. The data were processed using Chromeleon 7.0 200 software (Dionex, Thermo Fisher Scientific, New York, NY, USA) [

30,

31].

4.4.2. Total Phenolic Content (TPC)

The total phenolic content was determined using the Folin-Ciocalteu method adapted for microplate assays. In a microplate, 140 μL of distilled water, 10 μL of the sample or standard, and 10 μL of Folin's reagent were mixed, and allowed to stand for 6 minutes in darkness. Then, 40 μL of 7.5% (w/v) sodium carbonate solution was added, the reaction mixture was mixed and incubated at 45°C for 15 minutes in darkness. The absorbance was read at 760 nm using a Thermo Scientific Multiskan GO spectrophotometer. Gallic acid was used as the standard at different concentrations, and the results are expressed as milligrams of gallic acid equivalents per gram of dry tissue (mg GAE g

-1) [

32].

4.4.3. Total Flavonoid Content (TFC)

The determination of total flavonoid content required mixing 100 μL of the ethanolic extract with 130 μL of distilled water and 20 μL of a 1% (w/v) solution of 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate in a 96-well microplate. The absorbance of the solution was immediately read at 404 nm using a spectrophotometer (Thermo Scientific Multiskan GO). Rutin at different concentrations was used as the standard; in this case, 50 μL of rutin was mixed with 180 μL of distilled water and 20 μL of 2-aminoethyl diphenylborinate. The flavonoid content is expressed as milligrams of rutin equivalents per gram of dry tissue (mg RE g

-1) [

33].

4.4.4. Condensed Tannin Content (CTC)

The determination of condensed tannins was performed by preparing a 1% (w/v) vanillin solution in 100% methanol on the day of analysis and mixing it with an 8% (v/v) HCl solution (prepared in 100% methanol) in a 1:1 ratio to obtain a 0.5% (w/v) vanillin reagent solution. Epicatechin at different concentrations was used as the standard. Then, 40 μL of extract or standard was mixed with 200 μL of 0.5% (w/v) vanillin reagent solution. The reaction mixture was incubated at 30°C for 20 minutes and the absorbance was read at 500 nm using a Thermo Scientific Multiskan GO spectrophotometer. The condensed tannin content is expressed as milligrams of epicatechin equivalents per gram of dry tissue (mg EE g

−1) [

34].

4.4.5. DPPH Assay

The DPPH assay was adapted for microplate use. The 2,2-diphenyl-1-picrylhydrazyl (DPPH) radical was prepared at 150 µM in 80% (v/v) methanol by weighing 1.5 mg of DPPH and adding 20 mL of 80% methanol; subsequently, it was made up to a volume of 25 mL. The solution was sonicated for 15 minutes. The plate was prepared with 20 µL of the sample, in their respective independent wells and 200 µL of DPPH (150 µM) were added, recording the absorbance at 515 nm (Thermo Scientific Multiskan GO®). The results were reported as the median effective concentration (EC

50) required to scavenge DPPH* radicals, starting from the initial absorbance of DPPH at 515 nm. [

35].

4.5. Statistical Analysis

All experiments were performed at least in triplicate. The results are presented asmean values ± standard error (Mean ± SE). The normality of the data is determined using a Kolmogorov-Smirnov test. Data were analyzed using one-way ANOVA (P≤0.05), and to determine significant differences between tissues, seasons of collection, and types of drying, Tukey´s test was employed. Different letters denote significant variations (P≤0.05). Statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 10 software (StatSoft, Inc., 1984-2011).

5. Conclusions

The HPLC-DAD analysis revealed five phenolic compounds in the leaves and three in the fruit pulp of Randia echinocarpa, with chlorogenic acid exhibiting the highest concentration, followed by acids ferulic, rutin, caffeic, and catechin. This suggests that the leaves and fruit pulp of R. echinocarpa are a rich source of phenolic compounds, especially during the autumn season, and under different drying methods (especially with drying at 45°C, because better concentrations of compounds were obtained). Total phenolic concentration varied significantly depending on the tissue (pulp fruit, leaf, and bark) and season. The pulp fruit showed the highest phenolic concentration in winter, while bark had the lowest concentrations in winter, regardless of drying method. These variations can be attributed to seasonal factors (temperature, precipitation, UV radiation, soil nutrient variation, and predators) and the type of tissue analyzed.

This study is the first in reporting flavonoids concentrations in R. echinocarpa. Two flavonoid compounds (rutin and catechin) were identified, with higher concentrations in leaves during autumn, particularly over drying at 45°C. Flavonoid concentrations also varied between seasons, influenced by stress factors such as temperature, water scarcity, and solar radiation. Additionally, condensed tannin analysis showed higher concentrations in leaves, and this study is the first in reporting tannin concentrations in R. echinocarpa. While tannins can have antinutritional effects, the concentrations found established no significant risk for human or animal health at consumption. The concentrations of phenolic compounds found in this study differ from those reported in previous research, which vary depending on extraction methodology and cultivation or harvesting conditions. This difference highlights the importance of environmental factors present at the collection sites and the processing of plant tissues in the diversity of bioactive compounds in plants. The analyzed tissues could potentially be used to extract antioxidant compounds, due to the high antioxidant capacity found against DPPH*.

Furthermore, it would be important to determine the phenolic profile of other plant tissues in papache, across different seasons to understand the variability in profile composition. Additionally, conducting further studies on this plant used in traditional medicine is crucial to validate its use and describe the compounds responsible for its medicinal effects, especially in populations that are distant from medical services, such as rural and low-income areas.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at:

www.mdpi.com/xxx/s1, Figure S1: title; Table S1: title; Video S1: title.

Refugio Riquelmer Lugo-Gamboa

1, Norma Patricia Muñoz-Sevilla, Juan Pablo Apún-Molina

1, Jesús Arturo Fierro-Coronado

1, Abraham Cruz-Mendívil

1, Mauro Espinoza-Ortíz

1, Apolinar Santamaria-Miranda

1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.S.M., and N.P.M.S.; methodology, R.R.L.G., A.C.M., M.V.M. and J.A.F.C.; software, M.E.O.; validation, A.S.M., and J.P.A.M.; formal analysis, A.S.M. and N.P.M.S.; investigation, R.R.L.G., and A.S.M.; resources, A.S.M. and J.P.A.M.; data curation, A.S.M.; writing—original draft preparation, R.R.L.G.; writing—review and editing, A.S.M., and A.C.M.; visualization, M.E.O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was financially supported with grants from the National Polytechnic Institute (Project: SIP 20231812: Effect of the addition of carotenoids extracted from shrimp head by-product to increase pigmentation and gene expression in the skin of the fish Lutjanus guttatus).

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the staff and students of CIIDIR-Sinaloa for providing the facilities to support this research. We thank SECIHTY for the PhD fellowship (grant number 4005797) received by the student Refugio Riquelmer Lugo Gamboa.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- nabio. La diversidad biológica de México: Estudio de País 1998; Comisión Nacional para el Conocimiento y Uso de la Biodiversidad, México: 1998; Volume 1, pp. 61-103.

- Escamilla, P.; Casasola, M. Plantas medicinales de La Matamba y El Piñonal, municipio de Jamapa, Xalapa, Veracruz; 2015; pp. 51-69.

- Ávila-Uribe, M.M.; García-Zárate, S.N.; Sepúlveda-Barrera, A.S.; Godínez-Rodríguez, M.A. Plantas medicinales en dos poblados del municipio de San Martín de las Pirámides, Estado de México. Polibotánica 2016, 215-245.

- Bye, R.; Linares, E.; Mata, R.; Albor, C.; Castañeda, P.C.; Delgado, G. Ethnobotanical and phytochernical investigation of Randia echínocarpa (Rubiaceae). Anales del Instituto de Biología. Serie Botanica 1991, 62, 87–106. [Google Scholar]

- Maldonado-Almanza, B.J.; Alemán-Octaviano, A.M.; Gadea-Noguerón, R.; Rangel-Altamirano, M.G. Plantas útiles de la Mixteca Baja poblana; Universidad Autónoma del Estado de Morelos, 2017; pp. 26.

- Santos-Cervantes, M.E.; Ibarra-Zazueta, M.E.; Loarca-Piña, G.; Paredes-López, O.; Delgado-Vargas, F. Antioxidant and antimutagenic activities of Randia echinocarpa fruit. Plant Foods for Human Nutrition 2007, 62, 71–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuevas-Juárez, E.; Yuriar-Arredondo, K.Y.; Pío-León, J.F.; Montes-Avila, J.; López-Angulo, G.; Páz Díaz-Camacho, S.; Delgado-Vargas, F. Antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory properties of soluble melanins from the fruits of Vitex mollis Kunth, Randia echinocarpa Sessé et Mociño and Crescentia alata Kunth. Journal of Functional Foods 2014, 9, 78–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil-Avilés, M.d.R. Actividad inmunomoduladora y antioxidante in vivo de las melaninas solubles del fruto de Randia echinocarpa (papache). Doctorado, Universidad Autónoma de Sinaloa, 2020.

- Valenzuela-Atondo, D.A.; Delgado-Vargas, F.; López-Angulo, G.; Calderón-Vázquez, C.L.; Orozco-Cárdenas, M.L.; Cruz-Mendívil, A. Antioxidant activity of in vitro plantlets and callus cultures of Randia echinocarpa, a medicinal plant from northwestern Mexico. In Vitro Cellular & Developmental Biology - Plant 2020, 56, 440–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Camacho, M.; Gómez-Sánchez, C.E.; Cruz-Mendivil, A.; Guerrero-Analco, J.A.; Monribot-Villanueva, J.L.; Gutiérrez-Uribe, J. Modeling the growth kinetics of cell suspensions of Randia echinocarpa and characterization of their bioactive phenolic compounds. 2023, Research square. [CrossRef]

- Martínez-Flórez, S.; González-Gallego, J.; Culebras, J.M.; Tuñón, M.J. Los flavonoides: propiedades y acciones antioxidantes. Nutrición hospitalaria 2002, 17, 271–278. [Google Scholar]

- Asevedo, E.A.; Ramos Santiago, L.; Kim, H.J.; Syahputra, R.A.; Park, M.N.; Ribeiro, R.I.M.A.; Kim, B. Unlocking the therapeutic mechanism of Caesalpinia sappan: a comprehensive review of its antioxidant and anti-cancer properties, ethnopharmacology, and phytochemistry. Frontiers in Pharmacology 2025, 15, 1514573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velásquez, P.; Muñoz–Carvajal, E.; Luengo, M.; Bustos, D.; Galdames, F.; Gómez, M.; Montenegro, G.; Giordano, A. Phytochemical screening and biological properties of Quintral flower polyphenolic fractions. Natural Product Research 2024, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, K.; Esther Joice, P. Alternatives (Aegle marmelos and Spinacia oleracea) to antibiotics in fish forming environments. International Journal of Medicinal Plants. Photon 2018, 112, 856–864. [Google Scholar]

- Ordoñez, J.A.G.; Calderón, C.E.S.; Morán, J.; Caceres, J.V.A. Actividad antimicrobiana del extracto metanolico de los tallos de Verbena Litoralis. Revista Vive 2025, 8, 50–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano-Campos, M.C.; Díaz-Camacho, S.P.; Uribe-Beltrán, M.J.; López-Angulo, G.; Montes-Avila, J.; Paredes-López, O.; Delgado-Vargas, F. Bio-guided fractionation of the antimutagenic activity of methanolic extract from the fruit of Randia echinocarpa (Sessé et Mociño) against 1-nitropyrene. Food Research International 2011, 44, 3087–3093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kiri, A.S.; Tersur, K.J.; Jelani, F.B.; Ishaku, G.A. Antioxidants from Callus Technology. Journal of Applied Life Sciences International 2021, 24, 24–43. [Google Scholar]

- Ojeda-Ayala, M.; Gaxiola-Camacho, S.M.; Delgado-Vargas, F. Phytochemical composition and biological activities of the plants of the genus Randia. Botanical Sciences 2022, 100, 779–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isaza, J.H.; Veloza, L.A.; Ramirez, L.S.; Guevara, C.A. Estimación espectrofotométrica de taninos hidrolizables y condensados en plantas melastomatáceas. Scientia et technica 2007, 13, 261–266. [Google Scholar]

- Bernal-Peralta, A.d.S.; Camargo-Silva, Á.L. Efecto in vitro de los taninos condensados de las plantas Leucaena leucocephala, Calliandra calothyrsus y Flemingia macrophylla sobre huevos y larvas l3 de nematodos gastrointestinales de ovinos. Universidad de la Salle, 2016.

- Juárez-Trujillo, N.; Monribot-Villanueva, J.L.; Alvarado-Olivarez, M.; Luna-Solano, G.; Guerrero-Analco, J.A.; Jiménez-Fernández, M. Phenolic profile and antioxidative properties of pulp and seeds of Randia monantha Benth. Industrial Crops and Products 2018, 124, 53–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diaz, J.S.; Flores-Miranda, M.C.; Almaraz-Abarca, N.; Fierro-Coronado, A.; Luna-González, A.; García-Ulloa, M.; González-Ocampo, H.A. Effect of microencapsulated phenolic compound extracts of Maclura tinctoria (L.) Steud on growth performance and humoral immunity markers of white leg shrimp (Litopenaeus vannamei, Boone, 1931) juveniles. Spanish journal of agricultural research 2021, 19, 604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monreal-Garcia, H. Variabilidad genética y fenólica de Fouquieria splendens Engelm. (Fouquieriaceae). Doctorado, Instituto Politécnico Nacional, 2018.

- Arrellano-Lino, K.M.; Herrera-Rodriguez, J.L. Evaluación de los compuestos fenólicos y capacidad antioxidante del extracto de tres variedades de flor de mastuerzo (Tropaeolum majus) Licenciatura, Universidad nacional del centro del Perú, 2015.

- Nuñez, W.; Quispe, R.; Ramos, N.; Castro, A.; Gordillo, G. Actividad antioxidante y antienzimática in vitro y antinflamatoria in vivo del extracto hidroalcohólico de Caesalpinia spinosa “tara”. Ciencia e Investigación 2016, 19, 35–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güemes-Vera, N.; Dimas-López, D.; Piloni-Martini, J.; Soto-Simental, S.; Bernardino-Nicanor, A.; González-Cruz, L.; Quintero-Lir, A. Antioxidant Activity of Oxalis tuberosa peel extracts. Boletín de Ciencias Agropecuarias del ICAP 2019, 5, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razak, R.A.; Shariff, M.; Yusoff, F.M.; Ismail, I.S. Bactericidal efficacy of selected medicinal plant crude extracts and their fractions against common fish pathogens. Sains Malays 2019, 48, 1601–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Pérez, J.R.; Marroquín-Mora, D.C.; Pérez-González, M.I. Inclusión de extracto de Lippia graveolens (Kunth) en la alimentación de Oreochromis niloticus (Linnaeus, 1758) para la prevención de estreptococosis por Streptococcus agalactiae (Lehmann y Neumann, 1896). AquaTIC 2019, 15–24. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Mundo, J. Estudio químico y actividad biológica de Randia aculeata L. Maestría, Universidad Veracruzana, 2020.

- Almaraz-Abarca, N.; da Graça Campos, M.; Avila-Reyes, J.A.; Naranjo-Jimenez, N.; Corral, J.H.; Gonzalez-Valdez, L.S. Antioxidant activity of polyphenolic extract of monofloral honeybee-collected pollen from mesquite (Prosopis juliflora, Leguminosae). Journal of Food Composition and Analysis 2007, 20, 119–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valdez-Morales, M.; Espinosa-Alonso, L.G.; Espinoza-Torres, L.C.; Delgado-Vargas, F.; Medina-Godoy, S. Phenolic content and antioxidant and antimutagenic activities in tomato peel, seeds, and byproducts. Journal of agricultural and food chemistry 2014, 62, 5281–5289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kupina, S.; Fields, C.; Roman, M.C.; Brunelle, S.L. Determination of total phenolic content using the Folin-C assay: Single-laboratory validation, first action 2017.13. Journal of AOAC International 2019, 102, 320–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oomah, B.D.; Cardador-Martínez, A.; Loarca-Piña, G. Phenolics and antioxidative activities in common beans (Phaseolus vulgaris L). Journal of the Science of Food and Agriculture 2005, 85, 935–942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deshpande, S.S.; Cheryan, M. Evaluation of Vanillin Assay for Tannin Analysis of Dry Beans. Journal of Food Science 1985, 50, 905–910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brand-Williams, W.; Cuvelier, M.-E.; Berset, C. Use of a free radical method to evaluate antioxidant activity. LWT-Food science and Technology 1995, 28, 25–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).