SUMMARY

In children developing B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL), an immune evasion event takes place where otherwise “silent” preleukemic cells undergo a malignant transformation while escaping immune control, often by unknown mechanisms. Here, we identify the upregulation of PD-1 expression in preleukemic cells, triggered by Pax5 inactivation in mice and correlating with the time of conversion to leukemia, as a novel marker that favors leukemia evasion. This increase in PD-1 expression is apparent across diverse molecular B-ALL subtypes, both in mice and humans. PD-1 is not required for B-cell leukemogenesis but in the absence of PD-1, tumor cells express NK cell inhibitory receptors highlighting the necessity for leukemic cells to evade the host's NK immune response in order to exit the bone marrow. PD-1 expression reduces natural anti-tumor immune responses, but it sensitizes leukemic cells to immune checkpoint blockade strategies in mice and humans. PD-1 targeting confers clinical benefit by restoring NK-mediated tumor cell killing in vitro and eliminating tumor cells in vivo in mice engrafted with B-ALL. These results identify PD-1 as a new therapeutic target against leukemic progression, providing new opportunities for the treatment and possibly also the prevention of childhood B-ALL

INTRODUCTION

In recent years, childhood B-lineage acute lymphoblastic leukemias (B-ALLs) have been extensively characterized at the genomic level.1-5 Today, the vast majority of B-ALL cases can be categorized into distinct genetic subgroups, each associated with specific prognostic features and treatment responses.6-21 In general, B-ALL is characterized by a very low mutational burden.4,5 Further, in 35–50% of all B-ALL cases, de novo genetic alterations involving genes encoding B-cell transcription factors serve as the primary oncogenic event, determining the disease's biological and clinical attributes.22 Similarly, pathogenic germline variants in genes encoding these same transcription factors, such as PAX5, predispose to B-ALL development.16,23,24 However, these germline mutations, whether de novo or inherited, are not sufficient to trigger malignant transformation and require additional oncogenic secondary lesions to induce leukemia formation.16-18,22,25-27 Notably, these secondary genetic events frequently also involve B-cell transcription factors and exhibit a remarkable specificity and recurrence pattern relative to the primary lesions.

Notably, alterations in PAX5, the gene encoding an essential protein required for B cell development, are the most common central event in the process of B-cell leukemogenesis in children.1,16-18,22,28 These PAX5 alterations, including focal deletions, single nucleotide variants and intragenic amplification, have been postulated to arrest lymphoid maturation, a feature characteristic of this disease. Nevertheless, their precise role in B-ALL development is not fully understood.

In this regard, it is well known that a decreased dosage of Pax5 activity significantly accelerates the development of precursor B-ALL in mice carrying additional fusion genes such as BCR::ABLp190 and ETV6::RUNX1.29,30 These findings suggest that the secondary PAX5 genetic alterations that accumulate during the process of malignant transformation might favor escape from immune surveillance as B-ALL develops. Therefore, reinstating PAX5 function could potentially serve as a therapeutic approach to halt disease progression and even eliminate leukemic cells. Indeed, experimental evidence has corroborated this hypothesis, demonstrating that reintroducing endogenous Pax5 expression in Pax5-deficient leukemic B cells induces disease remission in murine models.31 The initiation of Pax5 expression mediates B-cell commitment during normal hematopoietic differentiation32 and its removal appears required to promote B-ALL development.33 Although these results suggest that PAX5 downregulation plays a role in facilitating B-leukemogenesis, such an activity has yet to be directly demonstrated. Determining the mechanisms underlying leukemia formation is essential to improve B-ALL therapy and guide approaches towards prevention.34,35

The earliest stages of B-ALL development in children typically go undetected,34 making it nearly impossible to study the initial phases of leukemic transformation in humans. Thus, we have utilized the Pax5+/- leukemia-prone model to investigate the mechanisms underlying immune evasion during progression to B-ALL. Mice heterozygous for Pax5, when exposed to infections, recapitulate the preleukemia-to-leukemia progression found in humans harboring the heterozygous germline PAX5 c.547G>A pathogenic variant.23,36-39 This pre-leukemia is defined as an at-risk population of normal-appearing cells from which B-ALL develops. These cells have the capacity to undergo malignant transformation; however, leukemia only appears in a small fraction of predisposed carriers when they are exposed to certain environmental factors.34,40

A substantial body of evidence underscores the significance of inhibitory receptors, commonly referred to as "immune checkpoints," in tumor-mediated immune suppression. Among immune checkpoint proteins, Programmed Cell Death 1 (PD-1) is mainly expressed on activated T cells and macrophages and, upon interaction with its ligand PD-L1 (Programmed Cell Death Ligand 1), expressed on tumor cells, PD-1 attenuates antitumor immune responses.41-44 In this study, we show that B-ALL progression is associated with upregulation of PD-1 on pre-leukemic cells and correlate with the time to malignant transformation in mice. This increase in PD-1 expression is apparent across diverse molecular B-ALL subtypes in mice and humans. Notably, targeting this B-ALL-associated PD-1 expression conferred clinical benefit by restoring NK-mediated tumor cell killing45 in vitro and eliminating tumor cells in vivo in mice engrafted with B-ALL. These results identify PD-1 as a new therapeutic target in leukemic progression, and provide new opportunities for the treatment or even prevention of childhood B-ALL.

RESULTS

B-ALL development screens in genetically predisposed mice identify cancer cell-autonomous upregulation of the inhibitory molecule PD-1.

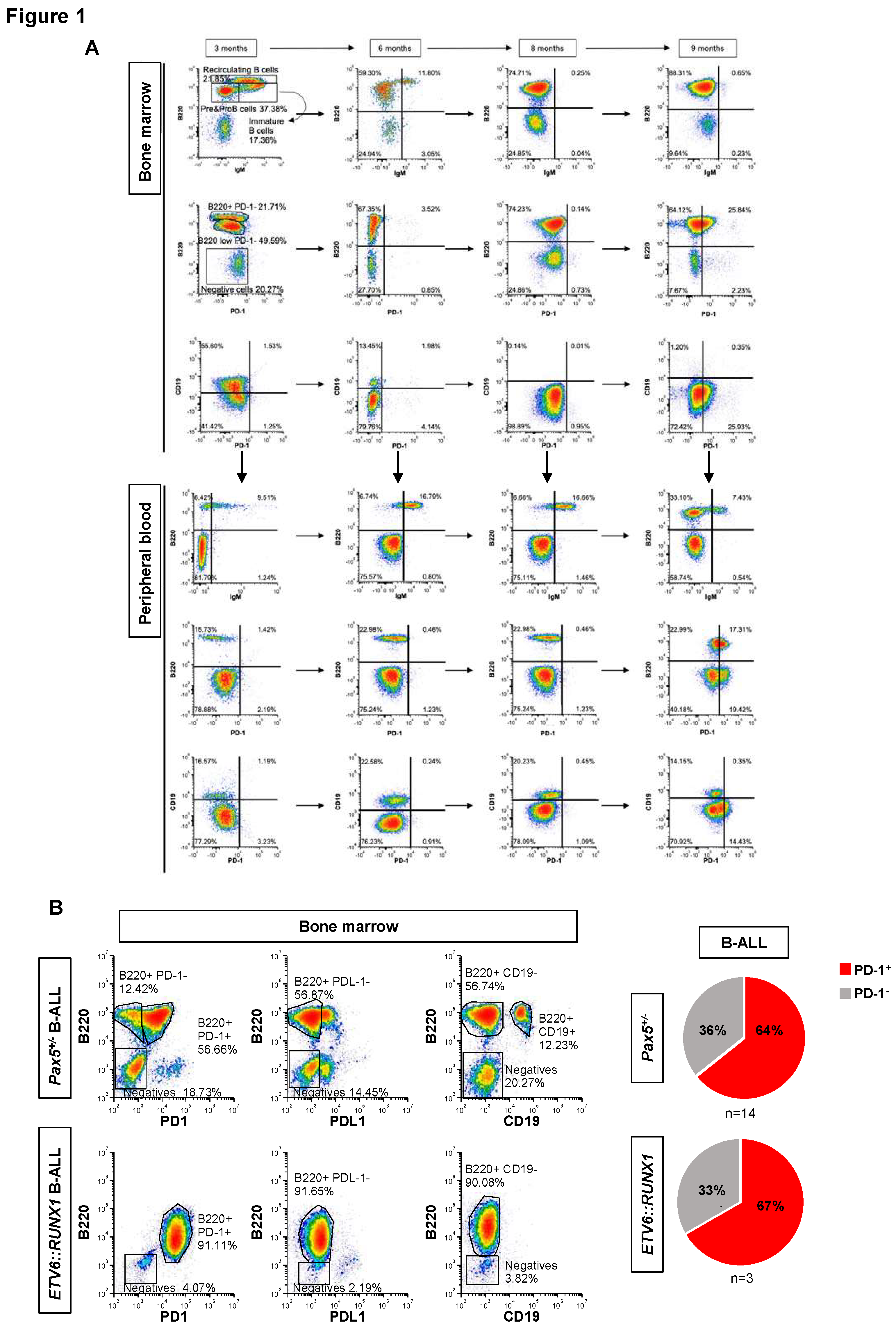

In order to understand the sequential events leading to immune escape during B-ALL development, we used serial bone marrow aspirates, coupled with sample analysis by spectral flow cytometry, in

Pax5+/- mice to characterize the immuno-regulatory events underlying the preleukemia-to-leukemia conversion (

Figure 1). In human patients carrying inherited mutations of

PAX5, preleukemic cells progress to B-ALL by losing the wild-type

PAX5 allele due to a secondary structural aberration of chromosome 9p.

23 This is phenocopied in the B-ALLs developing in the

Pax5+/- mouse model,

36-39,46 thus demonstrating the importance of biallelic alterations of

PAX5 for leukemia progression in this B-ALL subgroup. In these mice, upon loss or marked reduction of

Pax5 activity, the majority of B-ALLs lose

CD19 expression, similar to what is observed in human PAX5-associated predisposition to childhood B-ALL.

23 Thus, surface CD19 expression is a very useful surrogate marker of

Pax5 genetic status in mice and allows for identification of potential immuno-regulatory factors that might correlate with leukemic conversion.

Using the aforementioned approaches, we first analyzed the expression of PD-1 (CD279) and PD-L1 (CD274) on

Pax5+/- preleukemic cells as they switched to a leukemic state following an immune stress in the

Pax5+/- model.

36-39,46 Pax5+/- preleukemic cells (B220

+ IgM

-) did not express PD-1 or PD-L1, and, in spite of their accumulation over time, they were retained in the bone marrow (BM) (

Figure 1A and

Figures S1 and S2). In contrast, PD-1 was upregulated upon the conversion to leukemic B cells in the BM, defined by the lack of CD19 expression in parallel with their emergence in peripheral blood (PB) (

Figure 1A and

Figure S3A), indicating loss or marked reduction of

Pax5 activity similar to what is found in human leukemia.

23,36-39,46 To examine whether a similar increase in PD-1 expression with leukemia evolution is observed in other mouse leukemia models, we evaluated, together with B-ALLs appearing in

Pax5+/- (n= 14) animals, those that originated in transgenic

Sca1-ETV6-RUNX1 (n= 3) mice.

36,47 We found detectable PD-1 expression in leukemic cells in 9 of 14 (64%)

Pax5+/- B-ALL samples, and also in 2 of 3 (67%)

Sca1-ETV6-RUNX1+ B-ALL samples (

Figure 1B and

Table S1). All these mouse B-ALLs lacked surface CD19 expression, in agreement with the loss, or marked reduction, of

Pax5 activity, similar to what is found in human leukemia.

23,36-39,46 Thus, we next performed whole exome sequencing (WES) of paired tumor and germline samples from

Pax5+/− tumors to study the status of the wild-type

Pax5 allele within PD-1+ leukemic cells (

Figure S3B). WES identified four mutations at

Pax5 locus as well as other leukemia hotspot mutations such as

Nras:p.Q61H and

Jak3:p.R653H. Of note, we could not assess copy number or structural alterations via WES. Recurrent genetic alterations affecting the wild-type

Pax5 allele were detected within PD-1+ leukemic cells in some cases (

Figure S3B). Importantly, no PD-1 expression was detected in normal precursor B cells or in CD19-expressing B-ALLs in either mouse model (

Figure 1A-B), consistent with genetic evidence showing that PD-1 expression is below detection in the presence of Pax5,

48 and that expression of PD-1 is consistently up-regulated in Pax5-deficient precursor B cells.

48 Taken together, these data illustrate that the genetic alterations affecting

Pax5 that accumulate during the process of malignant transformation are associated with PD-1 upregulation upon leukemic conversion in genetically predisposed mice with acquired or germline alterations predisposing to B-ALL.

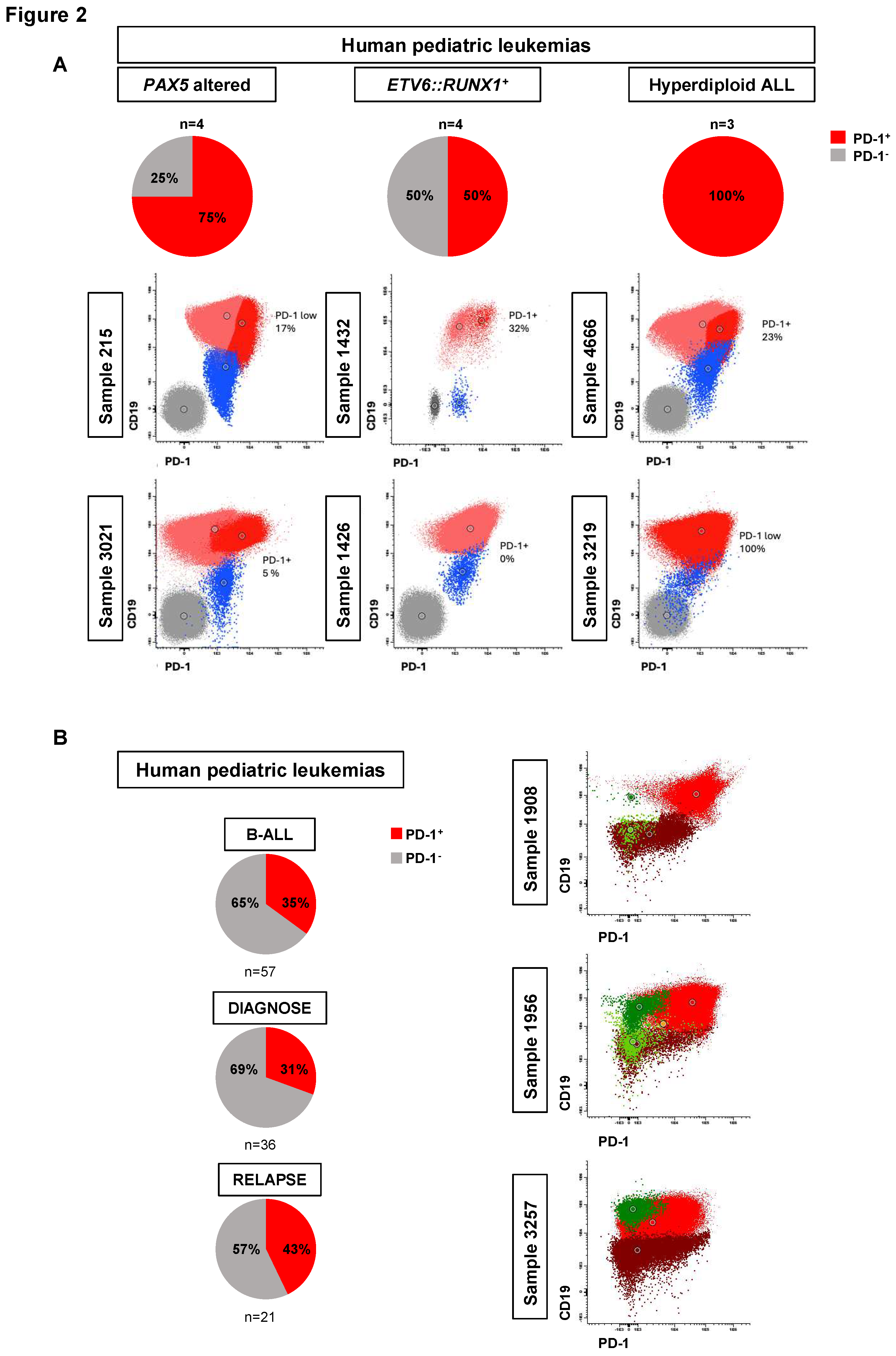

PD-1 expression in human B-ALL

To explore the clinical relevance of these results in humans, we subsequently investigated the expression of PD-1 in primary and xenografted human B-ALL samples, including those of the

PAX5-alt subtype (where CD19 expression is maintained because activation of the

CD19 promoter in human B-ALL cells is not solely dependent on PAX5 activity

49), and

ETV6::RUNX1+ and hyperdiploid subtypes. PD-1 expression was present in 50%-100% of these childhood B-ALL xenografts (n=11) (75% in

PAX5-alt B-ALLs, 50% in

ETV6::RUNX1+ B-ALLs and 100% in hyperdiploid B-ALLs) (

Figure 2A, Figure S4 and S5 and Table S2) and approximately in 31% of diagnostic (11 of 36) and in 43% of relapsed (9 of 21) childhood B-ALL primary samples (

Figure 2B, Figure S6 and Table S3). However, it is important to note that, in human leukemias like in mice, PD-1 expression is not solely dependent on PAX5 activity (

Table S2). In summary, PD-1 upregulation occurs in all molecular B-ALL subgroups tested, although the percentage of PD-1

+ leukemic cells varied from 2-100% per sample. Since, until now, PD-1 antibodies are not usually included in most B-ALL marker and diagnostic panels, further prospective studies in a larger dataset of B-ALL cases are needed to confirm the findings linking leukemia cell genomics and PD-1 expression. Still, our observations are consistent with an “immunoediting” process, whereby intratumoral heterogeneity results in the selection of leukemic clones that can avoid elimination by the immune system and thus leave the bone marrow. These findings suggest that there may be a suppression of immune surveillance across human B-ALL subtypes.

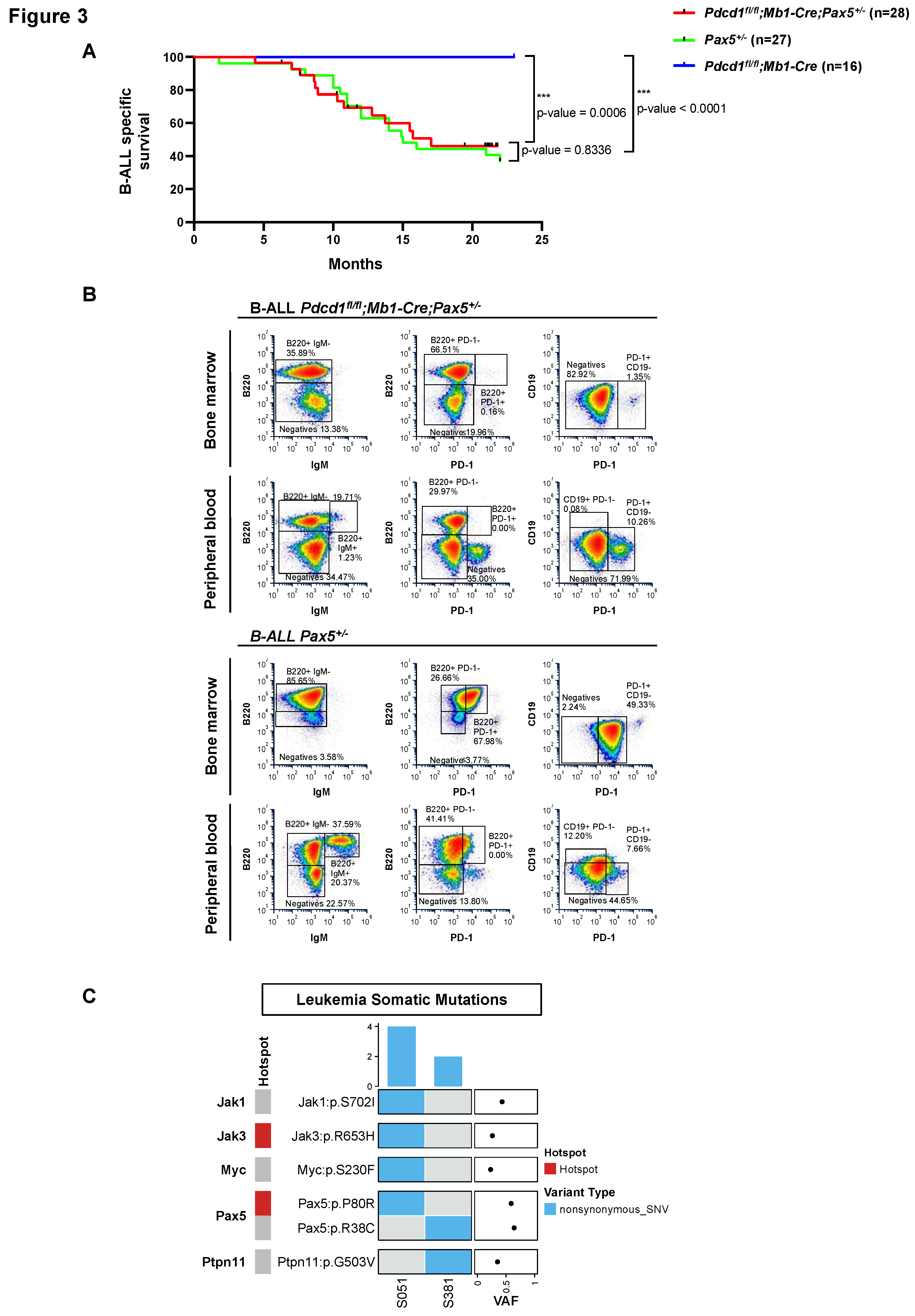

PD-1 is not required for Pax5-dependent B-cell leukemogenesis

PD-1 expression has been recently reported as a marker of leukemic stem cells (LSCs) in T-ALL, and anti-PD1 treatment eliminates such LSCs in a cell-autonomous manner.

50 To investigate the role of PD-1 signaling in Pax5-dependent B-ALL, and to ascertain if, also in human B-ALLs, PD-1

+ cells are functionally required for B-leukemogenesis, we used the PD-1 conditional knockout (

Pdcd1fl/fl) mouse (

Figure 3). Conditional

Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− mice were generated, where

Pdcd1 is deleted upon B-lineage commitment at the pro-B-cell stage, and we examined whether

Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− animals were prone to infection-induced B-ALL.

Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− mice were exposed to natural infections, and B-ALL development was monitored. We observed that B-ALL appeared in

Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− mice, where 46% (13 out of 28) developed the disease, closely resembling the incidence, latency and overall survival of

Pax5+/− animals (ns, p-value=0.8336) (

Figure 3A). This observation supports the notion that PD-1 is not required for B-leukemogenesis. Characterization of

Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− B-ALLs showed that they are histologically and phenotypically similar to those appearing in

Pax5+/- mice (

Figure 3B and Figure S7A-C).

To identify somatically acquired second hits leading to B-ALL development in Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− mice, we performed whole-genome sequencing of paired tumor and germline samples from two Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− tumors. We identified several somatically acquired recurrent mutations and copy-number variations involving B cell transcription factors in diseased Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− mice (Figure S7D). To compensate for their inability to upregulate PD-1, the B-ALLs emerging in PD-1-deficient mice express the NK cell inhibitory receptor CD161, something that has never been previously reported in PD-1+ B-ALLs (Figure S7E-F). Overall, the same genes appear mutated in Pax5+/− murine leukemias36-39,46 as in human B-ALL samples.4,5,16,51 Thus, the drivers of B-ALL appear similar in Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− and Pax5+/− mouse leukemic cells as well as human B-ALL blasts. However, in the absence of PD-1, tumor cells express the NK cell inhibitory receptor CD161, highlighting the importance of NK-mediated immune surveillance and necessity for leukemic cells to evade the host's NK immune response in order to exit the bone marrow.

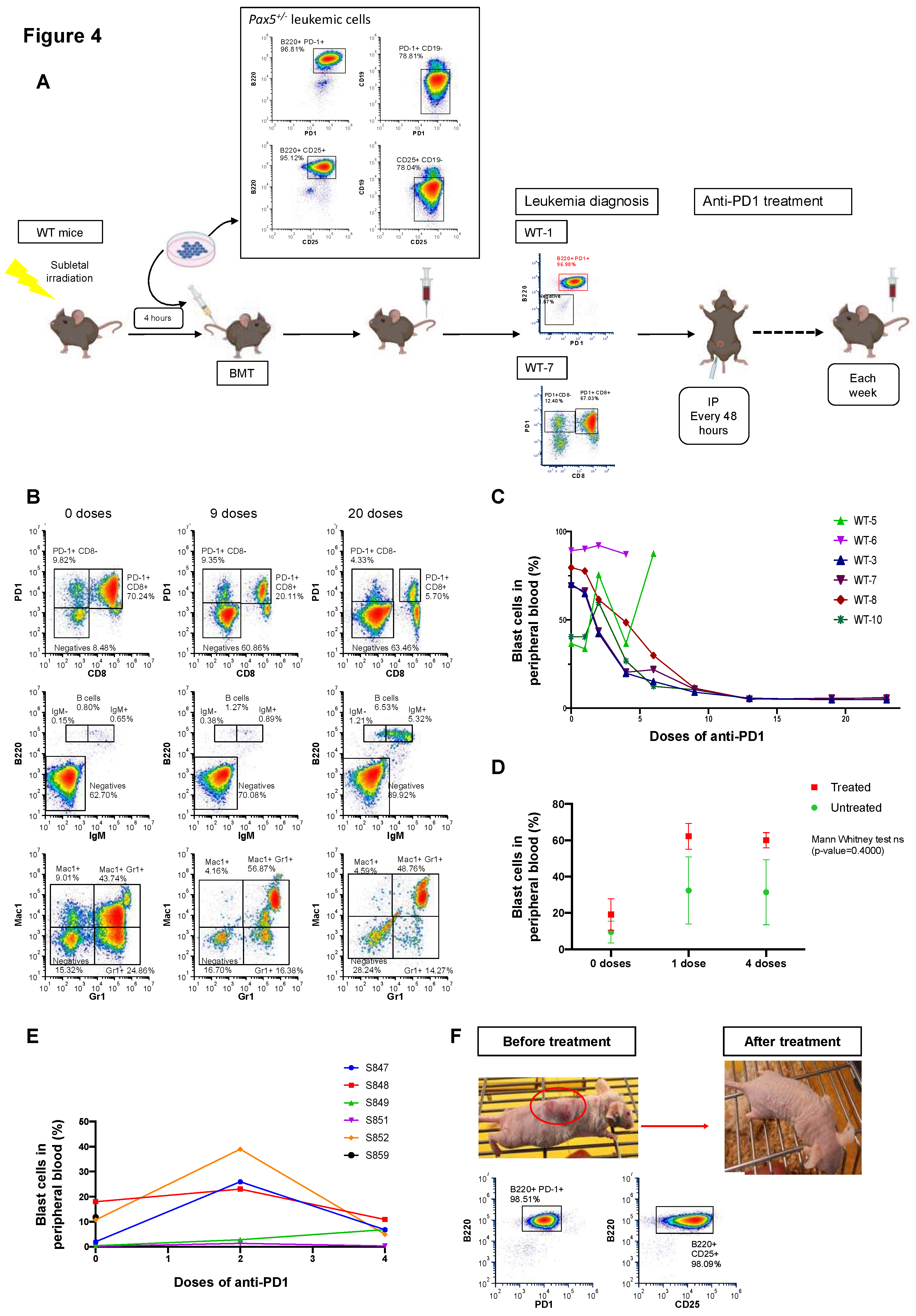

Anti-PD1 treatment restores the immune capacity to eliminate PD-1-positive tumor cells in mice engrafted with B-ALL

Building on our findings, we next determined the biological consequences of PD-1 upregulation on anti-tumor immune response. Thus, we examined the potential of targeting PD-1 for B-ALL treatment (Figure 4). Here, in order to better understand the results from spectral cytometry, it is important to mention that, since one of the main functions of Pax5 is maintaining non-B-cell genes repressed during B cell differentiation, B-ALL tumors arising in Pax5+/- mice may mimic a Pax5-/- phenotype and express promiscuous surface lineage markers such as CD8, Mac1, or Gr1 (Figure 4B). In contrast to what has been reported for T-ALL PD-1+ leukemia stem cells,50 in vitro PD-1 targeting did not induce apoptosis of PD-1+ B-ALL cells (neither of human or mouse origin) (Figure S8A-B). However, in vivo PD-1 targeting in B-ALL mice efficiently reduced disease burden and extended overall survival versus placebo-treated mice (p=0.0177; Figure 4A-C and Figure S9). These findings suggest that PD-1 targeting released the immune-suppressive regulation and restored tumor-specific cytotoxicity of either cytotoxic T lymphocytes or NK cells, which are the cellular components mediating the effects of PD-1 blockade.52,53

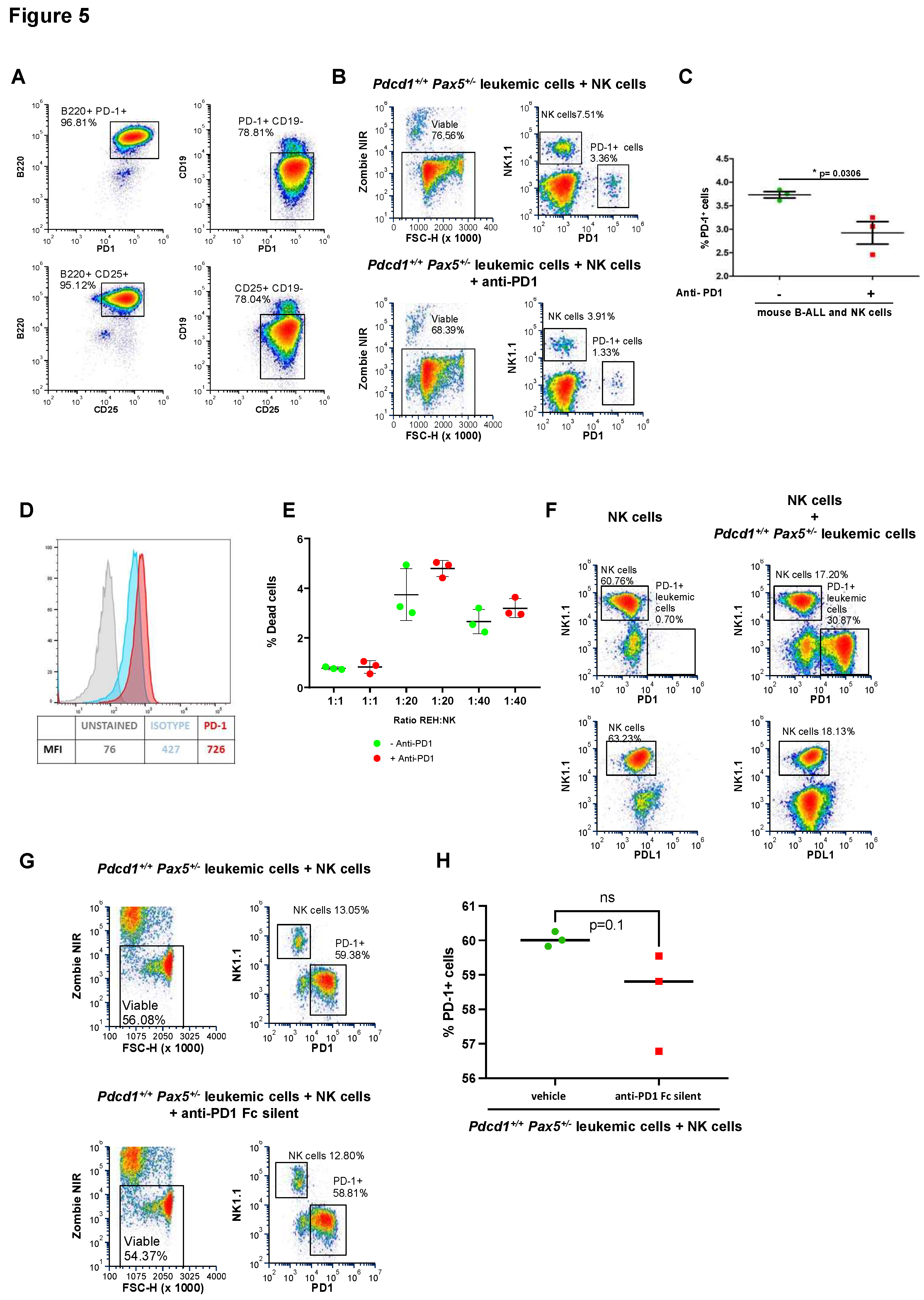

PD-1 targeting sensitizes PD-1-positive B-ALLs to NK cell-mediated killing.

To determine whether the therapeutic effect of PD-1 targeting in B-ALL mice is dependent on T or NK cells, we repeated the checkpoint targeting strategy (

Figure 4) in NOD/SCID mice, which lack both T and NK cells. We recapitulated B-ALL disease in NOD/SCID mice by tail-vein injecting the PD-1

+ leukemic B cells. To dissect the impact of PD-1 targeting in leukemic NOD/SCID mice, we initiated the treatment once blast cells were detected in PB. Unlike in immunocompetent animals, PD-1 targeting in PD-1

+ B-ALL NOD/SCID mice did not reduce disease burden (

Figure 4D). This similar

in vivo growth of tumor cells in NOD/SCID mice excluded a tumor cell–intrinsic effect of PD-1-targeting antibodies. However, when we similarly recapitulated PD-1

+ B-ALL disease in nu/nu mice, which lack T cells but possess NK cells, PD-1 targeting efficiently reduced disease burden (

Figure 4E-F). These findings are consistent with previous observations suggesting a T-cell independent immunosurveillance mechanism in the conversion of the preleukemic clone into a full-blown B-ALL.

34,37,54 To better understand how B-ALLs can escape NK cell surveillance through the PD-1 checkpoint, we performed

ex vivo NK cytotoxicity assays using both mouse (S748 cells) and human B-ALL (REH cells). NK cytotoxicity assays showed that targeting of PD-1 using the specific anti-PD1 antibody sensitizes both mouse and human B-ALLs to NK cell-mediated killing (

Figure 5A-E). Taken together, our results indicate that PD-1 is central to mediating the

in vivo escape of B-ALL cells from surveillance by NK cells and that PD-1 targeting conferred clinical benefit by restoring NK-mediated tumor cell killing

in vitro and eliminating tumor cells

in vivo in mice engrafted with B-ALL.

PD-1 directly inhibits the antitumor activity of NK cells on B-ALL

It has been proposed that the acquisition of PD-1 in the membrane via trogocytosis can inhibit NK cell response against tumor cells expressing PD-1.55 To test this hypothesis, we initially used PD-1+ S748 cells, which derive from the transformation of murine Pax5+/- B cells under immune stress;36 these S748 cells express high levels of PD-1 (Figure 5A), and we have used them extensively in previous studies.36 We now co-cultured PD-1+ S748 leukemic cells together with NK cells. In the absence of tumor cells, NK cells did not stain for PD-1 (Figure 5F). Similarly, NK cells did not stain positively for PD-1 when incubated with PD-1+ S748 leukemic cells (Figure 5F), indicating that PD-1 was not endogenously expressed by NK cells and was not acquired from leukemic cells in these settings. Likewise, co-culturing preleukemic (i.e., PD-1-negative) Pax5+/- cells with NK cells leads to cytotoxicity that is not affected by treatment with anti-PD-1 antibodies (Supplemental S10). Finally, to examine whether the therapeutic effect of PD-1 antibodies was due to antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) likely mediated by NK cells against PD-1+ leukemic cells coated with anti-PD1 antibodies, we used an engineered version of anti-PD-1 that lacks the ability to bind to Fc receptors (Fc-silent RMP1-14).56 Treatment with Fc-silent anti-PD1 antibodies did not affect the growth of PD-1+ S748 leukemic cells (Figure 5G-H), indicating that the therapeutic effect of anti-PD-1 antibodies was due to ADCC. Together, these results indicate that the expression of PD-1 by leukemic cells inhibits the antitumor activity of NK cells, allowing them to exit the BM and spread, and that this can be prevented by the treatment with PD-1-targeting antibodies.

DISCUSSION

If childhood B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia (B-ALL) happens only in genetically predisposed individuals, and is triggered by immune stress, then it is very likely a preventable disease. Therefore, it becomes imperative to delineate the processes implicated in leukemic progression, as these processes may provide windows of opportunity to intervene by stopping B-ALL in its tracks.

Here, our studies have uncovered a previously unknown molecular process that takes place during the initial stages of childhood B-cell leukemogenesis allowing us to discover a readout of PAX5 inactivation, the most frequently altered transcription factor in B-ALL.1,16-18,22,28 We demonstrate that the Pax5 genetic alterations that accumulate during the process of malignant transformation are associated with PD-1 upregulation upon the time of conversion to B-ALL in mice. This increase in PD-1 expression is also apparent across diverse molecular B-ALL subtypes in human B-ALL samples, although in mouse and human leukemias PD-1 expression is not solely dependent on PAX5 activity. In addition, PD-1 upregulation protects B-ALL blasts from NK-mediated immune surveillance. The key importance of protecting B-ALL blasts from NK-mediated immune surveillance is further supported by the upregulation of alternative NK cell inhibitory molecules in the B-ALLs that emerge in PD1-deficient mice. Finally, our findings reveal that PD-1 targeting can serve as a therapeutic strategy to promote NK cell-mediated killing of leukemia cells, providing new opportunities for the treatment or prevention of childhood B-ALL. Our findings could also justify the use of small molecular PD-1 inhibitors for oral administration in B-ALL patients, currently in development for some solid tumors.57 It is important to underscore that, the identification of a biomarker correlating with environmental exposures along the trajectory of leukemic transformation, has been achieved using predisposed mouse models where the B-ALL disease emerges naturally. This is relevant because many of the observations obtained previously using these mouse models have later been mirrored in pediatric B-ALL patients, as illustrated by the case where the B-cell alterations found in preleukemic Pax5+/- mice36 were later confirmed in children carrying PAX5 germline variants,58 or by the discovery that B-ALL driver genes are not targeted by AID in mice, subsequently validated in human ALL blasts,46 or by the identification of gut microbiome immaturity in B-ALL-predisposed mice,37 which was also later corroborated in children with B-ALL 59. Hence, these preclinical mouse models, where B-ALL occurs naturally are indispensable for elucidating the early phases of B-ALL development, which are typically unnoticed in children,34 making it nearly impossible to study the initial phases of leukemic transformation in humans. Likewise, recently it has been shown that NK cell–mediated cytotoxicity shapes the clonal evolution of human B-cell leukemia.60

Overall, our study demonstrates that certain cases of human B-ALL express PD-1, and that targeting this pathway with checkpoint inhibitors can activate NK cell activity, thereby presenting a potential therapeutic opportunity. In fact, our data show that sustained leukemia suppression can be achieved with anti-PD1 single-agent treatment in the presence of a functional NK compartment. Accordingly, these findings form the foundation for a potential new approach to treat B-ALL, the commonest form of pediatric cancer and the leading cause of cancer-related death in children. These results are also of immediate diagnostic importance, because they suggest that most PD-1 positive B-ALL cases may be rapidly detected by flow cytometry immunophenotyping to further guide classification and tailored therapy. Future studies exploring larger cohorts of patients are warranted to better establish how PD-1 upregulation may be used to direct daily clinical care of children with B-ALL.

Materials availability

This study did not generate new unique reagents.

Data and code availability

Authors confirm that all relevant data are included in the paper and/or its supplemental information files. All data reported in this article are deposited to NCBI’s Sequence Read Archive (SRA) under the BioProject accession number PRJNA1084753.

This paper does not report original code.

METHODS DETAILS

Mouse model for natural immune stress-driven leukemia

Pax5+/-, Sca1-ETV6-RUNX1, Mb1-Cre and Pdcd1fl/fl (C57BL/6-Pdcd1tm1.1Mrl; Taconic Model #13976) mice are as previously described.47,61 Pax5+/- mice were crossed with Pdcd1fl/fl mice and Mb1-Cre animals to generate mice of Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− genotype. Mice were bred and maintained under specific pathogen free (SPF) conditions until exposed to conventional pathogens present in non-SPF animal facilities, as previously described.36-39,46,47 Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− mice were treated with a cocktail of antibiotics (ampicillin, 1 g/L, Ratiopharm; vancomycin, 500 mg/L, Cell Pharm; ciprofloxacin, 200 mg/L, Bayer Vital; imipenem, 250 mg/L, MSD; metronidazole, 1 g/L, Fresenius) added to their drinking water ad libitum for a period of eight weeks with the aim to facilitate leukemia development as previously described.37

All mouse experiments were performed in accordance with the applicable Spanish and European legal regulations, and had been previously authorized by the pertinent institutional committees of both University of Salamanca and Spanish Research Council (CSIC). Both male and female mice were used in all the studies. Housing environmental conditions included a temperature of 21°C ±2°, humidity of 55% ±10%, and a 12 hour:12 hour light:dark cycle. Mice had access to food and water ad libitum. During housing, animals were monitored daily for health status. No data were excluded from the analyses. The inclusion criteria was based on the genotype of the mouse: transgenic versus control littermate. The investigator was not blinded to the group allocation.

Pax5+/-, Sca1-ETV6-RUNX1, and Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− mice of a mixed C57BL/6×CBA background were used in this study. For the relevant experiments, Pax5+/-, Sca1-ETV6-RUNX1, and Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/− littermates were used. When animals showed signs of distress, they were humanely euthanized and organs harvested. All organs were macroscopically inspected under the stereomicroscope and representative tissue samples were cut and immediately fixed and stained for subsequent histological analysis. Differences in Kaplan-Meier survival plots of transgenic and WT mice were analyzed using the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. Statistical analyses were performed by using GraphPad Prism v8.2.1 (GraphPad Software).

B-ALL-specific survival curve of

Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre;Pax5+/- mice (n=28),

Pax5+/- mice (n=27) and

Pdcd1fl/fl;Mb1-Cre mice (n=16) following exposure to common mouse pathogens was defined by the Log-rank (Mantel-Cox). p-values are shown in

Figure 3A.

B-ALL patient-derived xenograft (PDX) models

Leukemic patient-derived xenografts (PDX) were obtained from the St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital Public Resource of Patient-derived and Expanded Leukemias (PROPEL) (include

https://propel.stjude.cloud). Briefly, PDX were established by tail vein injection of primary human leukemia cells into 8-12-week-old sub-lethally irradiated (250 Rad) NOD.Cg-Prkdc

scid IL2rg

tm1Wjl /SzJ (NSG) mice (The Jackson Laboratory).

62 Spleen cells harvested from engrafted mice were used for expansion in subsequent passages. The level of engraftment was monitored by monthly saphenous vein bleeds and flow cytometric analysis for human CD45

+ and CD19

+ cells.

Leukemic Pax5 +/− pro-B cell culture

Iscove's Modified Dulbecco's Medium (IMDM) supplemented with 50 μmol/L β-mercaptoethanol, 1 mmol/L l-glutamine, 2% heat-inactivated FCS, 1 mmol/L penicillin–streptomycin (BioWhittaker), and 0.03% (w/v) primatone RL (Sigma) was used for pro–B-cell culture experiments. Leukemic cells isolated by magnetic-activated cell sorting for B220+ (Milteny Biotec) from BM were cultured on Mitomycin C–treated ST2 cells in IMDM medium without IL-7 (R&D Systems).

Anti-PD1 inhibitor in vitro experiments

Leukemic Pax5+/− pro-B cells expressing PD-1 were seeded at 106/3mL/well in 6-well plates and treated with or without (vehicle) anti-PD1 monoclonal antibody (BioXCell; BE0146; 7.36 μg/mL) for 4, 8 or 24 hours before being subjected to a cell viability assay, as described below. Leukemic Pax5+/− pro-B cells expressing PD-1 were also treated with or without (vehicle) anti-PD1 that lacks the ability to bind to Fc receptors (Fc-silent RMP1-14) for 8 hours before being subjected to a cell viability assay.

Viability Assays

Cells from anti-PD1 inhibitor cultures were washed twice with PBS (5’, 1000 rpm 4ºC). Then, samples were stained with the fixable Zombie NIR viability dye kit (BioLegend; 423105) following the manufacturer's instructions. Subsequently, cells were washed with PBS supplemented with 1% FCS to eliminate the excess of the viability marker (5’, 1400 rpm, RT). Samples were acquired in a Cytek Northern Light 2000 spectral cytometer (two lasers, red and blue) and analyzed with FCS Express software. Specific fluorescence of the fluorophores as well as known forward and orthogonal light scattering properties of mouse cells were used to establish gates. A total of 100,000 cells per sample were assessed. The difference between experimental variables was determined using the Mann Whitney U test.

BM Transplantation Experiments

Leukemic Pax5+/− pro-B cells expressing PD-1 were injected intravenously into sub-lethally irradiated (4 Gy) secondary recipient 8-week-old male syngeneic mice (C57BL/6 × CBA), NOD/SCID or nu/nu mice, respectively. Disease development in the recipient mice was monitored by periodic peripheral blood (PB) analysis until blast cells were detected. Then, mice were treated with anti-PD1 or placebo and assessed for B-ALL progression as indicated below. The study of PD-1 targeting as a potential therapeutic approach for childhood B-ALL was done by using mouse PD-1+ leukemic proB cells injected through the tail vein of sub lethally irradiated (4Gy) wild-type (n=6) mice (C57BL/6 × CBA), NOD/SCID mice (n=8) or nu/nu (n=6) mice, respectively. No significant differences were observed in the decrease in the percentage of malignant cells between treated and untreated mice (Mann Whitney test ns; p=0.4000), showing the inefficacy of the anti-PD1 treatment in the absence of T and NK cells.

Preclinical Therapeutics

Anti-PD1 monoclonal antibody (BioXCell; BE0146) prepared in PBS was administered at 5μg per mouse, intraperitoneally every 48 hours, after animals had developed a detectable leukemic burden (percentage of blasts superior to 15% in PB) as documented by FACS analysis of PB. Disease progression in recipient mice was monitored by periodic PB analysis.

For a detailed description of methods, see the Supplemental Information

Acknowledgments

The authors thank all the members of their laboratories for discussion. We also thank the Public Resource of Patient-derived and Expanded Leukemias (PROPEL),

https://propel.stjude.cloud, as provider of leukemia xenografts used in this study and the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities of St. Jude Children’s Research Hospital. Research at C. Cobaleda's laboratory was partially supported by Grant PID2021-122787OB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and by “ERDF/EU”, and a Research Contract with the “Fundación Síndrome de Wolf-Hirschhorn o 4p-”. Institutional grants from the “Fundación Ramón Areces” and “Banco de Santander” to the CBMSO are also acknowledged. Research in C. Vicente-Dueñas group has been funded by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) through the project PI22/00379 and co-funded by the European Union (European Regional Development Fund (ERDF)/European Social Fund (ESF)). K. E. Nichols receives funding from the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities (ALSAC); R01CA241452 from the National Cancer Institute; R21AI113490 from the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases; Histiocytosis Association; and Cures within Reach. MR research is partially supported by Asociación Pablo Ugarte. Research in ISG group is partially supported by Grant PID2021-122185OB-I00 funded by MICIU/AEI/ 10.13039/501100011033 and PID2024-155590OB-I00 and by “ERDF/EU”, by Junta de Castilla y León (UIC-017, CSI144P20, and CSI016P23), by the Fundación Científica de la Asociación Española contra el Cáncer (TRNSC247893SÁNC), and by Instituto de Salud Carlos III (ISCIII) (AC24/00021). C. Cobaleda, M. Ramírez, and I. Sánchez-García have been supported by the Fundación Científica de la Asociación Española contra el Cáncer (PRYCO211305SANC), and by the Fundacion Unoentrecienmil (CUNINA project). M. Ramírez, and I. Sánchez-García have been supported by the TRANSCAN2023-1858-066 – REACTION Project. A. Casado-García was supported by a FSE-Conserjería de Educación de la Junta de Castilla y León 2019 (ESF, European Social Fund) fellowship (CSI067-18) and by Juan de la Cierva 2022 (JDC2022-049078-I). B. Ruiz-Corzo is supported by a FSE-Conserjería de Educación de la Junta de Castilla y León 2022 (ESF, European Social Fund) fellowship (CSI002-22). S. Alemán-Arteaga and A. Lopez-Alvarez de Neyra are supported by an

Ayuda para Contratos predoctorales para la formación de doctores (PRE2019-088887) and (PRE2022-103628), respectively. J. Martínez-Cano was supported by a predoctoral fellowship FPI-UAM 2019. We also thank the Hartwell Center and Dr. Ti-Cheng Chang from the Center for Bioinformatics at SJCRH for their support to the whole genome sequencing and bioinformatic pipelines

Supplementary Material

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Initial conception of the project was designed by K.E.N., A.O., M.R-O., and I.S.-G. Development of methodology was performed by A.C-G., G.G.-A., J.P., S.B., N.O., B.R-C., J.I., A.C.-V., A.C.-R., B.S., S.A-A., E.G.S., J.M-C., A.L-A., P.S-C., O.B., S.R., P.P-M., F.J.G.C., M.B.G.C., C.V-D., C.C., K.E.N., A.O., M.R-O., and I.S.-G. O.B., M.B.G.C., F.J.G.C., and C.V.-D. performed pathology review. Management of patient information was performed by K.E.N., M.R-O., and I.S.-G. A.C-G., G.G.-A., J.P., S.B., N.O., B.R-C., J.I., A.C.-V., A.C.-R., B.S., S.A-A., E.G.S., J.M-C., A.L-A., P.S-C., O.B., S.R., P.P-M., F.J.G.C., M.B.G.C., C.V-D., C.C., K.E.N., A.O., M.R-O., and I.S.-G were responsible for analysis and interpretation of the data (e.g., statistical analysis, biostatistics, computational analysis). Paper preparation was performed by A.C-G., G.G.-A., J.P., S.B., N.O., B.R-C., J.I., A.C.-V., A.C.-R., B.S., S.A-A., E.G.S., J.M-C., A.L-A., P.S-C., O.B., S.R., P.P-M., F.J.G.C., M.B.G.C., C.V-D., C.C., K.E.N., A.O., M.R-O., and I.S.-G Administrative, technical, or material support (i.e., reporting or organizing the data, constructing databases) was compiled by A.C-G., G.G.-A., J.P., S.B., N.O., K.E.N., A.O., M.R-O., and I.S.-G. The study was supervised by K.E.N., A.O., M.R-O., and I.S.-G.

Declaration of Interests

O. Blanco reports personal fees from Takeda and Clinigen outside the submitted work. A. Orfao reports participation in educational activities by AMGEN, outside this work. No disclosures were reported by the other authors.

References

- Mullighan, C.G., Goorha, S., Radtke, I., Miller, C.B., Coustan-Smith, E., Dalton, J.D., Girtman, K., Mathew, S., Ma, J., Pounds, S.B., et al. (2007). Genome-wide analysis of genetic alterations in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nature 446, 758-764. [CrossRef]

- Iacobucci, I., and Mullighan, C.G. (2017). Genetic Basis of Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. J Clin Oncol 35, 975-983. [CrossRef]

- Holmfeldt, L., Wei, L., Diaz-Flores, E., Walsh, M., Zhang, J., Ding, L., Payne-Turner, D., Churchman, M., Andersson, A., Chen, S.C., et al. (2013). The genomic landscape of hypodiploid acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 45, 242-252. [CrossRef]

- Ma, X., Liu, Y., Alexandrov, L.B., Edmonson, M.N., Gawad, C., Zhou, X., Li, Y., Rusch, M.C., Easton, J., Huether, R., et al. (2018). Pan-cancer genome and transcriptome analyses of 1,699 paediatric leukaemias and solid tumours. Nature 555, 371-376. [CrossRef]

- Grobner, S.N., Worst, B.C., Weischenfeldt, J., Buchhalter, I., Kleinheinz, K., Rudneva, V.A., Johann, P.D., Balasubramanian, G.P., Segura-Wang, M., Brabetz, S., et al. (2018). The landscape of genomic alterations across childhood cancers. Nature 555, 321-327.

- Roberts, K.G., Morin, R.D., Zhang, J., Hirst, M., Zhao, Y., Su, X., Chen, S.C., Payne-Turner, D., Churchman, M.L., Harvey, R.C., et al. (2012). Genetic alterations activating kinase and cytokine receptor signaling in high-risk acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Cell 22, 153-166.

- Iacobucci, I., Li, Y., Roberts, K.G., Dobson, S.M., Kim, J.C., Payne-Turner, D., Harvey, R.C., Valentine, M., McCastlain, K., Easton, J., et al. (2016). Truncating Erythropoietin Receptor Rearrangements in Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia. Cancer Cell 29, 186-200.

- Roberts, K.G., Li, Y., Payne-Turner, D., Harvey, R.C., Yang, Y.L., Pei, D., McCastlain, K., Ding, L., Lu, C., Song, G., et al. (2014). Targetable kinase-activating lesions in Ph-like acute lymphoblastic leukemia. N Engl J Med 371, 1005-1015. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J., McCastlain, K., Yoshihara, H., Xu, B., Chang, Y., Churchman, M.L., Wu, G., Li, Y., Wei, L., Iacobucci, I., et al. (2016). Deregulation of DUX4 and ERG in acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 48, 1481-1489.

- Gu, Z., Churchman, M., Roberts, K., Li, Y., Liu, Y., Harvey, R.C., McCastlain, K., Reshmi, S.C., Payne-Turner, D., Iacobucci, I., et al. (2016). Genomic analyses identify recurrent MEF2D fusions in acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Commun 7, 13331. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, K., Okuno, Y., Kawashima, N., Muramatsu, H., Okuno, T., Wang, X., Kataoka, S., Sekiya, Y., Hamada, M., Murakami, N., et al. (2016). MEF2D-BCL9 Fusion Gene Is Associated With High-Risk Acute B-Cell Precursor Lymphoblastic Leukemia in Adolescents. J Clin Oncol 34, 3451-3459.

- Gocho, Y., Kiyokawa, N., Ichikawa, H., Nakabayashi, K., Osumi, T., Ishibashi, T., Ueno, H., Terada, K., Oboki, K., Sakamoto, H., et al. (2015). A novel recurrent EP300-ZNF384 gene fusion in B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 29, 2445-2448.

- Yasuda, T., Tsuzuki, S., Kawazu, M., Hayakawa, F., Kojima, S., Ueno, T., Imoto, N., Kohsaka, S., Kunita, A., Doi, K., et al. (2016). Recurrent DUX4 fusions in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia of adolescents and young adults. Nat Genet 48, 569-574.

- Lilljebjorn, H., Henningsson, R., Hyrenius-Wittsten, A., Olsson, L., Orsmark-Pietras, C., von Palffy, S., Askmyr, M., Rissler, M., Schrappe, M., Cario, G., et al. (2016). Identification of ETV6-RUNX1-like and DUX4-rearranged subtypes in paediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Commun 7, 11790.].

- Lilljebjorn, H., and Fioretos, T. (2017). New oncogenic subtypes in pediatric B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 130, 1395-1401. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z., Churchman, M.L., Roberts, K.G., Moore, I., Zhou, X., Nakitandwe, J., Hagiwara, K., Pelletier, S., Gingras, S., Berns, H., et al. (2019). PAX5-driven subtypes of B-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 51, 296-307. [CrossRef]

- Bastian, L., Schroeder, M.P., Eckert, C., Schlee, C., Tanchez, J.O., Kampf, S., Wagner, D.L., Schulze, V., Isaakidis, K., Lazaro-Navarro, J., et al. (2019). PAX5 biallelic genomic alterations define a novel subgroup of B-cell precursor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Leukemia 33, 1895-1909.

- van Engelen, N., Roest, M., van Dijk, F., Sonneveld, E., Bladergroen, R., van Reijmersdal, S.V., van der Velden, V.H.J., Hoogeveen, P.G., Kors, W.A., Waanders, E., et al. (2023). A novel germline PAX5 single exon deletion in a pediatric patient with precursor B-cell leukemia. Leukemia 37, 1908-1911.

- Cree, I.A. (2022). The WHO Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours. Leukemia 36, 1701-1702.

- Alaggio, R., Amador, C., Anagnostopoulos, I., Attygalle, A.D., Araujo, I.B.O., Berti, E., Bhagat, G., Borges, A.M., Boyer, D., Calaminici, M., et al. (2022). The 5th edition of the World Health Organization Classification of Haematolymphoid Tumours: Lymphoid Neoplasms. Leukemia 36, 1720-1748.

- Arber, D.A., Orazi, A., Hasserjian, R.P., Borowitz, M.J., Calvo, K.R., Kvasnicka, H.M., Wang, S.A., Bagg, A., Barbui, T., Branford, S., et al. (2022). International Consensus Classification of Myeloid Neoplasms and Acute Leukemias: integrating morphologic, clinical, and genomic data. Blood 140, 1200-1228.

- Fischer, U., Yang, J.J., Ikawa, T., Hein, D., Vicente-Duenas, C., Borkhardt, A., and Sanchez-Garcia, I. (2020). Cell Fate Decisions: The Role of Transcription Factors in Early B-cell Development and Leukemia. Blood Cancer Discov 1, 224-233. [CrossRef]

- Shah, S., Schrader, K.A., Waanders, E., Timms, A.E., Vijai, J., Miething, C., Wechsler, J., Yang, J., Hayes, J., Klein, R.J., et al. (2013). A recurrent germline PAX5 mutation confers susceptibility to pre-B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Genet 45, 1226-1231. [CrossRef]

- Duployez, N., Jamrog, L.A., Fregona, V., Hamelle, C., Fenwarth, L., Lejeune, S., Helevaut, N., Geffroy, S., Caillault Venet, A., Marceau-Renaut, A., et al. (2020). Germline PAX5 mutation predisposes to familial B acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood. 10.1182/blood.2020005756.

- Fregona, V., Bayet, M., Bouttier, M., Largeaud, L., Hamelle, C., Jamrog, L.A., Prade, N., Lagarde, S., Hebrard, S., Luquet, I., et al. (2024). Stem cell-like reprogramming is required for leukemia-initiating activity in B-ALL. J Exp Med 221. [CrossRef]

- Zhu, X., He, F., Zeng, H., Ling, S., Chen, A., Wang, Y., Yan, X., Wei, W., Pang, Y., Cheng, H., et al. (2014). Identification of functional cooperative mutations of SETD2 in human acute leukemia. Nat Genet 46, 287-293. [CrossRef]

- Mar, B.G., Bullinger, L.B., McLean, K.M., Grauman, P.V., Harris, M.H., Stevenson, K., Neuberg, D.S., Sinha, A.U., Sallan, S.E., Silverman, L.B., et al. (2014). Mutations in epigenetic regulators including SETD2 are gained during relapse in paediatric acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Commun 5, 3469.

- Kuiper, R.P., Schoenmakers, E.F., van Reijmersdal, S.V., Hehir-Kwa, J.Y., van Kessel, A.G., van Leeuwen, F.N., and Hoogerbrugge, P.M. (2007). High-resolution genomic profiling of childhood ALL reveals novel recurrent genetic lesions affecting pathways involved in lymphocyte differentiation and cell cycle progression. Leukemia 21, 1258-1266. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Lorenzo, A., Auer, F., Chan, L.N., Garcia-Ramirez, I., Gonzalez-Herrero, I., Rodriguez-Hernandez, G., Bartenhagen, C., Dugas, M., Gombert, M., Ginzel, S., et al. (2018). Loss of Pax5 Exploits Sca1-BCR-ABL(p190) Susceptibility to Confer the Metabolic Shift Essential for pB-ALL. Cancer Res 78, 2669-2679.

- Rodriguez-Hernandez, G., Casado-Garcia, A., Isidro-Hernandez, M., Picard, D., Raboso-Gallego, J., Aleman-Arteaga, S., Orfao, A., Blanco, O., Riesco, S., Prieto-Matos, P., et al. (2021). The Second Oncogenic Hit Determines the Cell Fate of ETV6-RUNX1 Positive Leukemia. Front Cell Dev Biol 9, 704591. [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.J., Cimmino, L., Jude, J.G., Hu, Y., Witkowski, M.T., McKenzie, M.D., Kartal-Kaess, M., Best, S.A., Tuohey, L., Liao, Y., et al. (2014). Pax5 loss imposes a reversible differentiation block in B-progenitor acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Genes Dev 28, 1337-1350.

- Cobaleda, C., Schebesta, A., Delogu, A., and Busslinger, M. (2007). Pax5: the guardian of B cell identity and function. Nat Immunol 8, 463-470. [CrossRef]

- Cobaleda, C., Jochum, W., and Busslinger, M. (2007). Conversion of mature B cells into T cells by dedifferentiation to uncommitted progenitors. Nature 449, 473-477.

- Cobaleda, C., Vicente-Duenas, C., and Sanchez-Garcia, I. (2021). Infectious triggers and novel therapeutic opportunities in childhood B cell leukaemia. Nat Rev Immunol 21, 570-581. [CrossRef]

- Cobaleda, C., Vicente-Duenas, C., and Sanchez-Garcia, I. (2021). An immune window of opportunity to prevent childhood B cell leukemia. Trends Immunol 42, 371-374. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Lorenzo, A., Hauer, J., Vicente-Duenas, C., Auer, F., Gonzalez-Herrero, I., Garcia-Ramirez, I., Ginzel, S., Thiele, R., Constantinescu, S.N., Bartenhagen, C., et al. (2015). Infection Exposure is a Causal Factor in B-cell Precursor Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia as a Result of Pax5-Inherited Susceptibility. Cancer Discov 5, 1328-1343. [CrossRef]

- Vicente-Duenas, C., Janssen, S., Oldenburg, M., Auer, F., Gonzalez-Herrero, I., Casado-Garcia, A., Isidro-Hernandez, M., Raboso-Gallego, J., Westhoff, P., Pandyra, A.A., et al. (2020). An intact gut microbiome protects genetically predisposed mice against leukemia. Blood 136, 2003-2017. [CrossRef]

- Casado-Garcia, A., Isidro-Hernandez, M., Oak, N., Mayado, A., Mann-Ran, C., Raboso-Gallego, J., Aleman-Arteaga, S., Buhles, A., Sterker, D., Sanchez, E.G., et al. (2022). Transient Inhibition of the JAK/STAT Pathway Prevents B-ALL Development in Genetically Predisposed Mice. Cancer Res 82, 1098-1109. [CrossRef]

- Isidro-Hernandez, M., Casado-Garcia, A., Oak, N., Aleman-Arteaga, S., Ruiz-Corzo, B., Martinez-Cano, J., Mayado, A., Sanchez, E.G., Blanco, O., Gaspar, M.L., et al. (2023). Immune stress suppresses innate immune signaling in preleukemic precursor B-cells to provoke leukemia in predisposed mice. Nat Commun 14, 5159. [CrossRef]

- Cobaleda, C., Vicente-Duenas, C., Ramirez-Orellana, M., and Sanchez-Garcia, I. (2022). Revisiting the concept of childhood preleukemia. Trends Cancer 8, 887-889.

- Sharma, P., and Allison, J.P. (2015). The future of immune checkpoint therapy. Science 348, 56-61.

- Quatrini, L., Mariotti, F.R., Munari, E., Tumino, N., Vacca, P., and Moretta, L. (2020). The Immune Checkpoint PD-1 in Natural Killer Cells: Expression, Function and Targeting in Tumour Immunotherapy. Cancers (Basel) 12. [CrossRef]

- Sierra, J.M., Secchiari, F., Nunez, S.Y., Iraolagoitia, X.L.R., Ziblat, A., Friedrich, A.D., Regge, M.V., Santilli, M.C., Torres, N.I., Gantov, M., et al. (2021). Tumor-Experienced Human NK Cells Express High Levels of PD-L1 and Inhibit CD8(+) T Cell Proliferation. Front Immunol 12, 745939.

- Iraolagoitia, X.L., Spallanzani, R.G., Torres, N.I., Araya, R.E., Ziblat, A., Domaica, C.I., Sierra, J.M., Nunez, S.Y., Secchiari, F., Gajewski, T.F., et al. (2016). NK Cells Restrain Spontaneous Antitumor CD8+ T Cell Priming through PD-1/PD-L1 Interactions with Dendritic Cells. J Immunol 197, 953-961.

- Laskowski, T.J., Biederstadt, A., and Rezvani, K. (2022). Natural killer cells in antitumour adoptive cell immunotherapy. Nat Rev Cancer 22, 557-575.

- Rodriguez-Hernandez, G., Opitz, F.V., Delgado, P., Walter, C., Alvarez-Prado, A.F., Gonzalez-Herrero, I., Auer, F., Fischer, U., Janssen, S., Bartenhagen, C., et al. (2019). Infectious stimuli promote malignant B-cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia in the absence of AID. Nat Commun 10, 5563. [CrossRef]

- Rodriguez-Hernandez, G., Hauer, J., Martin-Lorenzo, A., Schafer, D., Bartenhagen, C., Garcia-Ramirez, I., Auer, F., Gonzalez-Herrero, I., Ruiz-Roca, L., Gombert, M., et al. (2017). Infection Exposure Promotes ETV6-RUNX1 Precursor B-cell Leukemia via Impaired H3K4 Demethylases. Cancer Res 77, 4365-4377. [CrossRef]

- Nutt, S.L., Morrison, A.M., Dorfler, P., Rolink, A., and Busslinger, M. (1998). Identification of BSAP (Pax-5) target genes in early B-cell development by loss- and gain-of-function experiments. EMBO J 17, 2319-2333. [CrossRef]

- Witkowski, M.T., Lee, S., Wang, E., Lee, A.K., Talbot, A., Ma, C., Tsopoulidis, N., Brumbaugh, J., Zhao, Y., Roberts, K.G., et al. (2022). NUDT21 limits CD19 levels through alternative mRNA polyadenylation in B cell acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Nat Immunol 23, 1424-1432.

- Xu, X., Zhang, W., Xuan, L., Yu, Y., Zheng, W., Tao, F., Nemechek, J., He, C., Ma, W., Han, X., et al. (2023). PD-1 signalling defines and protects leukaemic stem cells from T cell receptor-induced cell death in T cell acute lymphoblastic leukaemia. Nat Cell Biol 25, 170-182. [CrossRef]

- Case, M., Matheson, E., Minto, L., Hassan, R., Harrison, C.J., Bown, N., Bailey, S., Vormoor, J., Hall, A.G., and Irving, J.A. (2008). Mutation of genes affecting the RAS pathway is common in childhood acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Cancer Res 68, 6803-6809. [CrossRef]

- Benson, D.M., Jr., Bakan, C.E., Mishra, A., Hofmeister, C.C., Efebera, Y., Becknell, B., Baiocchi, R.A., Zhang, J., Yu, J., Smith, M.K., et al. (2010). The PD-1/PD-L1 axis modulates the natural killer cell versus multiple myeloma effect: a therapeutic target for CT-011, a novel monoclonal anti-PD-1 antibody. Blood 116, 2286-2294.

- Hsu, J., Hodgins, J.J., Marathe, M., Nicolai, C.J., Bourgeois-Daigneault, M.C., Trevino, T.N., Azimi, C.S., Scheer, A.K., Randolph, H.E., Thompson, T.W., et al. (2018). Contribution of NK cells to immunotherapy mediated by PD-1/PD-L1 blockade. J Clin Invest 128, 4654-4668.

- Dang, J., Wei, L., de Ridder, J., Su, X., Rust, A.G., Roberts, K.G., Payne-Turner, D., Cheng, J., Ma, J., Qu, C., et al. (2015). PAX5 is a tumor suppressor in mouse mutagenesis models of acute lymphoblastic leukemia. Blood 125, 3609-3617. [CrossRef]

- Hasim, M.S., Marotel, M., Hodgins, J.J., Vulpis, E., Makinson, O.J., Asif, S., Shih, H.Y., Scheer, A.K., MacMillan, O., Alonso, F.G., et al. (2022). When killers become thieves: Trogocytosed PD-1 inhibits NK cells in cancer. Sci Adv 8, eabj3286.

- Dahan, R., Sega, E., Engelhardt, J., Selby, M., Korman, A.J., and Ravetch, J.V. (2015). FcgammaRs Modulate the Anti-tumor Activity of Antibodies Targeting the PD-1/PD-L1 Axis. Cancer Cell 28, 285-295.

- Awadasseid, A., Zhou, Y., Zhang, K., Tian, K., Wu, Y., and Zhang, W. (2023). Current studies and future promises of PD-1 signal inhibitors in cervical cancer therapy. Biomed Pharmacother 157, 114057. [CrossRef]

- Escudero, A., Takagi, M., Auer, F., Friedrich, U.A., Miyamoto, S., Ogawa, A., Imai, K., Pascual, B., Vela, M., Stepensky, P., et al. (2022). Clinical and immunophenotypic characteristics of familial leukemia predisposition caused by PAX5 germline variants. Leukemia 36, 2338-2342.

- Liu, X., Zou, Y., Ruan, M., Chang, L., Chen, X., Wang, S., Yang, W., Zhang, L., Guo, Y., Chen, Y., et al. (2020). Pediatric Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia Patients Exhibit Distinctive Alterations in the Gut Microbiota. Front Cell Infect Microbiol 10, 558799. [CrossRef]

- Buri MC, Shoeb MR, Bykov A, Repiscak P, Baik H, Dupanovic A, David FO, Kovacic B, Hall-Glenn F, Dopa S, Urbanus J, Sippl L, Stofner S, Emminger D, Cosgrove J, Schinnerl D, Poetsch AR, Lehner M, Koenig X, Perié L, Schumacher TN, Gotthardt D, Halbritter F, Putz EM. (2025) Natural Killer Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity Shapes the Clonal Evolution of B-cell Leukemia. Cancer Immunol Res. 13(3):430-446.

- Hobeika, E., Thiemann, S., Storch, B., Jumaa, H., Nielsen, P.J., Pelanda, R., and Reth, M. (2006). Testing gene function early in the B cell lineage in mb1-cre mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 103, 13789-13794.

- Holmfeldt, L., and Mullighan, C.G. (2015). Generation of human acute lymphoblastic leukemia xenografts for use in oncology drug discovery. Curr Protoc Pharmacol 68, 14 32 11-14 32 19. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).