1. Introduction

Despite the impressive successes of modern medicine, measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) have not lost their relevance and still pose a serious public health problem. Insofar as targeted therapies for MMR viral illnesses have not yet been developed, vaccines remain the only possible means of prevention. Separate monovalent vaccines against each virus, and preparations containing two or three attenuated MMR viruses in various combinations, have been created and are used in medical practice. Only one such combination vaccine, the trivalent design, elicits immunity to all MMR viruses occurs at once. Three-component vaccines have received the widest distribution globally. They contain various MMR strains and are marketed under different brand names: Priorix, M-M-R II, Vactrivir, Trimovax, etc. [1-8].

The widespread use of highly effective MMR vaccines served as a prerequisite for the WHO to set a goal of completely eliminating MMR in most countries [

9]. However, despite some successes, the desired progress in solving this problem has not yet been achieved, as outbreaks of MMR infections are observed annually in both developing and industrialized countries [10-13]. Since 2018, serious measles outbreaks have been reported in Europe, including: Poland [

14], Iceland [

15], Bosnia and Herzegovina [

16] and several other European countries [17-20].

According to the UN, for the period from January to December 2023, forty member states reported 30,000 cases of measles, which is 30 times higher than for all of 2022 [

20]. According to an analysis by the WHO and the United Nations Children's Fund (UNICEF), 127,350 measles cases were reported in the European Region for 2024 [

21]. This is double the number of cases reported for 2023 and the highest number since 1997. These data are alarming regarding the emerging epidemiological situation, especially in light of the risk for potential complications (acute and chronic) that measles infection bears.

Vulnerability to measles and mumps is often due to negative socioeconomic factors, such as poverty, overcrowding, insufficient access to healthcare, etc. [22-24]. In addition, increased susceptibility to MMR infections may be due to environmental and biological causes, including unfavorable climatic factors, other viral infections (such as HIV or COVID), intoxications, tissue and organ transplants, neoplastic diseases, etc. [25-31]. In the European continent, a key cause of the measles outbreak is low vaccination

compliance in the young. The is confirmed by information from the European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control that eight out of ten people diagnosed with measles in the EU/EEA in the last year were unvaccinated [

32].

In the Republic of Serbia, the national vaccination schedule indicates: the first dose of MMR vaccine to be administrated when the child turns 12 months of age (second year); and the second dose should be administrated before the first grade (no later than 7 full years of age). Obligatory MMR immunization of children became a part of the national immunization program in 1993, and the MMR vaccine has been given in two doses since 1996 [

33]. Earlier (before 1993), monovalent mumps and measles vaccines were administrated.

The situation with mumps and rubella in Europe has been less concerning in previous years. However, individual cases were registered until recently, with mumps being the most frequently registered [

34]. In Serbia, the epidemiological situation for the period from 2021 to 2023 was quite favorable [

35]. In 2021, 1 case of measles and 4 cases of mumps were registered. In 2022, no patients with measles were identified, and mumps was diagnosed in 11 people. In 2023, the number of patients with measles was 50 (0.74 per 100K pop.), and there were 6 mumps cases. No cases of rubella were registered during this period.

It can be assumed that one of the prerequisites for such relative wellbeing is likely the active use of MMR vaccines. Since 1992, the Dutch MMR vaccine ‘M-M-RVaxPro® (Merck Sharp & Dohme B.V., J07BD52) has been used in Serbia. It is a live, attenuated design. According to available data, vaccination coverage has been 84.1-91% in recent years (

Table 1) [

35].

The data in

Table 1 shows the achievement of the required vaccination coverage in the Serbian population in 2023. Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain similar data regarding 2023 for the Belgradian population. However, available results for 2022, indicating the achievement of 83% coverage by planned vaccination, may indicate a high, although not absolute, level of protection of the capital's population against measles and rubella.

A more accurate judgment regarding MMR seropositivity levels can be made based on herd immunity survey results. The levels of measles and rubella seropositivity in the Serbian population were 76.2% (95% CI: 73.4-78.8) and 86.1% (95% CI: 83.8-88.2) in 2018, respectively [

13]. Similar data regarding mumps herd immunity in the Serbian population could not be found. Likewise, no information was found on herd immunity in the Belgradian population. Studies about MMR seroprevalence are limited, and the few that are published in peer-reviewed journals reflect the epidemiological situation in the northern Serbian province.

In a study on Vojvodina Province (Serbia) published in 2019, it was reported that 86.9% of serum samples were seropositive for measles (median age was 20 years) [

36]. The highest share of measles seronegativity was observed in children aged 12–23 months and in adults aged 20–39 years (56.1% and 18.5%, respectively). A different study examined the percentage of participants seropositive for anti-rubella antibodies, which was 92.9% in the entire sample (Vojvodina region only) [

37]. The highest seronegativity was in the youngest (1 year) age group (44.7%), followed by the groups aged 24–49 (6.4%) and 2–11 years (6.2%).

To our knowledge, there are no published studies on MMR seroprevalence in the Belgrade region. This situation prompted the planning and execution of the current study. The seropositivity levels for MMR viral pathogens were assessed, as well as vaccination coverage among the population of Belgrade.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Description of the Volunteer Cohort

A cross-sectional randomized study, "Herd immunity to vaccine-preventable and other relevant infections in the Belgradian population", was conducted in May, 2024 under a joint program between Rospotrebnadzor (Russia) and the Serbian Ministry of Health. It was approved by the relevant local ethics committees at: the Saint Petersburg Pasteur Institute (Russia); and the Institute of Virology, Vaccines, and Sera “Torlak” (Serbia). Before the study, all participants, or their legal representatives, were familiarized with the purpose and methodology of the study and signed a statement of informed consent. The selection of volunteers was carried out using a web application. The size of a representative sample was calculated using the previously described method [

38,

39]. The total number of volunteers examined in the cohort was 2,533. The cohort was stratified by age and gender as shown in

Table 2.

As follows from the data, the cohort was dominated by middle-aged volunteers in the range from 30 to 59 years old, whose total share was 65.4% (95% CI: 63.5-67.2). In terms of gender, the cohort included 67.7% females and 32.3% males, the number of females in the cohort was 2-fold higher than males (

Table 2). The largest percentages of women were noted in the age groups 18-29 and 40-49 years (75.5% and 70.9%, respectively). The distribution of volunteers by activity is presented in

Table 3.

The most active participants in the research were healthcare workers (21.4%) and pensioners (14.3%) (

Table 3). The least number were military personnel and schoolchildren. To increase representativeness during data analysis, military personnel were combined with civil servants, and schoolchildren were combined with preschoolers. The predominance of pensioners and health workers in the cohort may be due to the higher social activity, and more responsible attitude towards their health, of volunteers in these two categories.

2.2. Research Methods

2.2.1. Volunteer Inclusion Criteria

During a broad information campaign, individuals filled out an online questionnaire via a web application including personal data: full name, gender, age, area of residence, field of activity, chronic disease status, and contact information. Individuals who met the inclusion criteria (no acute illnesses at the time of the study, not on immunosuppressive therapies) were invited to have their blood drawn and undergo subsequent laboratory testing. The methodology for organizing and conducting the study has been described in detail earlier [

39]. At the blood collection office, the registrar, together with the volunteer, filled out an extended questionnaire. This included questions about past MMR illness and other vaccine-preventable infections. Information on immunization (vaccination, revaccination) against the listed infections was also collected, including vaccine names and dates of usage. Information about previous MMR illness history was obtained from the volunteer verbally. Information about vaccination was obtained from certificates provided by the volunteer (if available) and clarified from other medical records. In the absence of such records, verbal statements from volunteers were used. The collection of anamnestic data and blood samples lasted for two full weeks in May, 2024.

2.2.2. Sample Collection and Testing

For subsequent laboratory detection of specific IgG antibodies, blood samples were taken from the cubital vein of each volunteer into vacutainers with a solution of ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid (K3EDTA). After centrifugation, blood plasma was separated from cellular elements, transferred to microtubes, and stored at 4°C until testing. ELISA analyses were performed using commercial reagent kits (Vector-Best JSC, Russia) according to manufacturer instructions: "VectoMeasles-IgG" for the presence and level (IU/ml) of anti-measles IgG; "VectoRubella-IgG" for the presence and level (IU/ml) of anti-rubella IgG; and "VectoParotit-IgG" for the presence of anti-mumps IgG.

For anti-measles IgG, results were interpreted as follows: positive (≥ 0.18 IU/ml); negative (< 0.12 IU/ml); or inconclusive (0.12-0.17 IU/ml). For anti-rubella IgG, results were interpreted as follows: positive (≥ 10 IU/ml) or negative (< 10 IU/ml).

For anti-mumps IgG, a cut-off optical density (ODcrit. = ODmedia for K- + 0.3) and a positivity coefficient (PC = ODsample / ODcrit.) were calculated. The results were interpreted as follows: positive (PC > 1); negative (PC < 0.8); or inconclusive (0.8 ≤ PC ≤1).

2.3. Statistical Processing

Statistical processing was performed by methods of variation statistics using Excel 2011. Statistical processing of proportions was performed using the method of A. Wald and J. Wolfowitz [

40], as modified by A. Agresti and B.A. Coull [

41]. The significance of differences in proportions was calculated using the z test [

42]. Differences were considered significant at p ≤ 0.05, unless otherwise stated.

3. Results

3.1. Measles

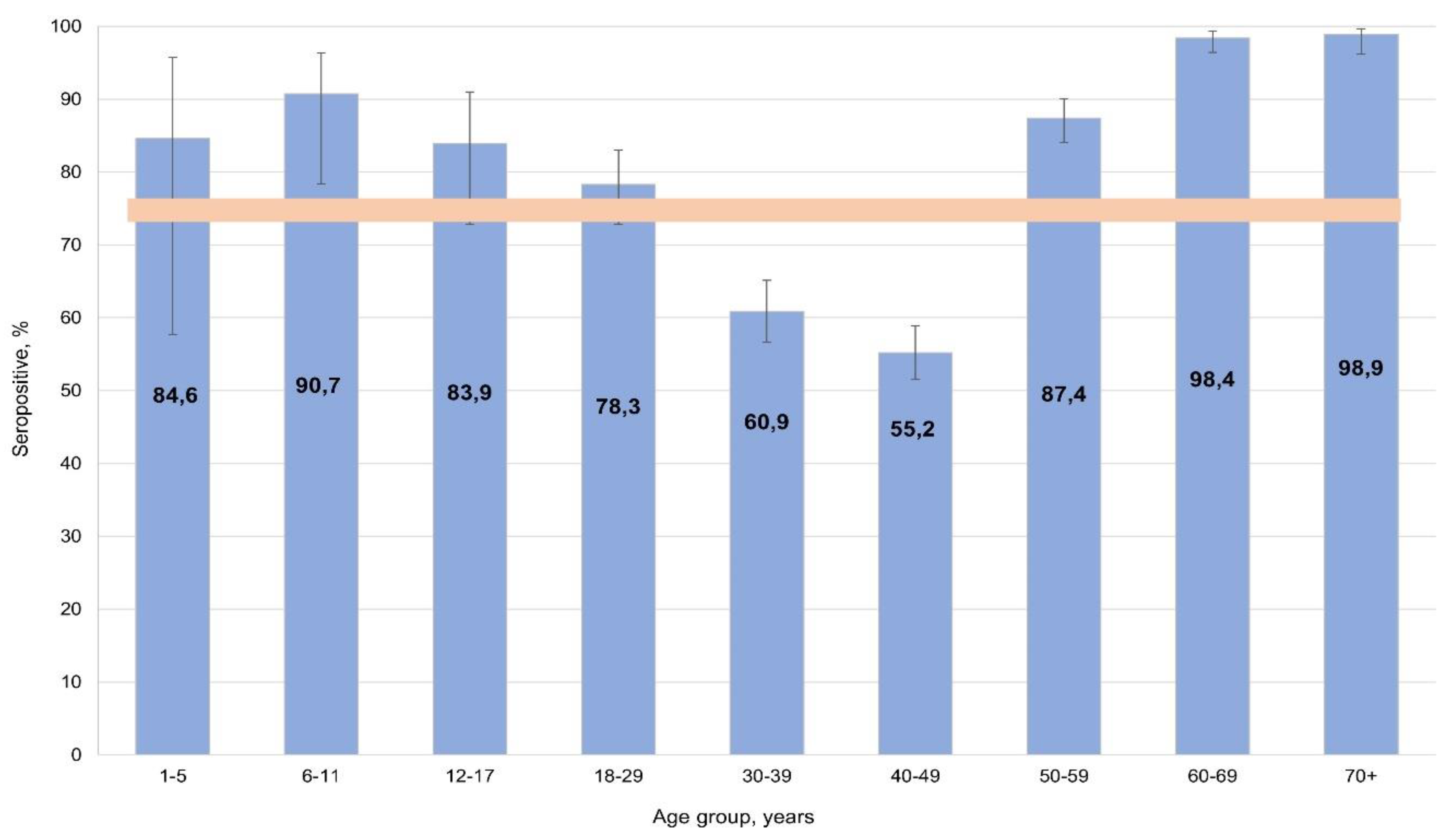

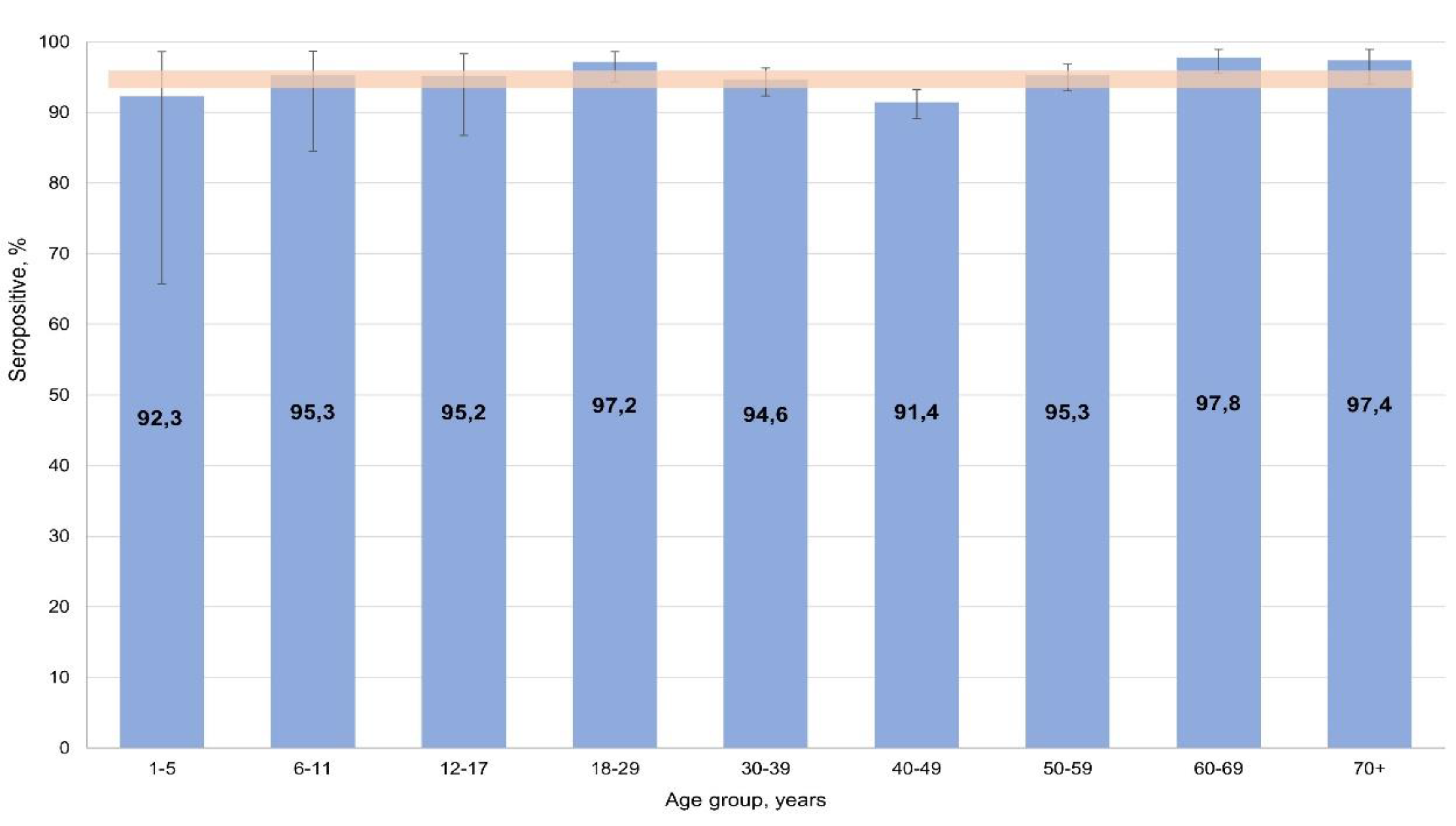

During serological testing, the percentage of individuals with anti-measles IgG was 74.7% (95% CI: 73.0-76.4), with uneven distributed across the cohort (

Figure 1).

The highest seropositivity values were found in: children aged 6-11 years (90.7%; 95% CI: 77.8-96.9); adults aged 60-69 years (98.4%; 95% CI: 96.3-99.4); and those aged 70+ years (98.9%; 95% CI: 96.0-100). Significantly lower measles seropositivity was noted among middle-aged volunteers (30-49 years): 57.2% (95% CI: 54.4-60.0). All differences were significant relative to the overall cohort average.

According to the literature, 95% is the protective level [

43]. Therefore, seroprevalence reached the protective threshold in older age groups. In children 1 to 17 years old, seroprevalence almost reached the protective value. As such, only among middle-aged individuals (30-49 years) would a measles catch-up vaccination potentially be required. In light of the noted age group differences, seroprevalence depending on activity was also analyzed for potential differences and their significance.

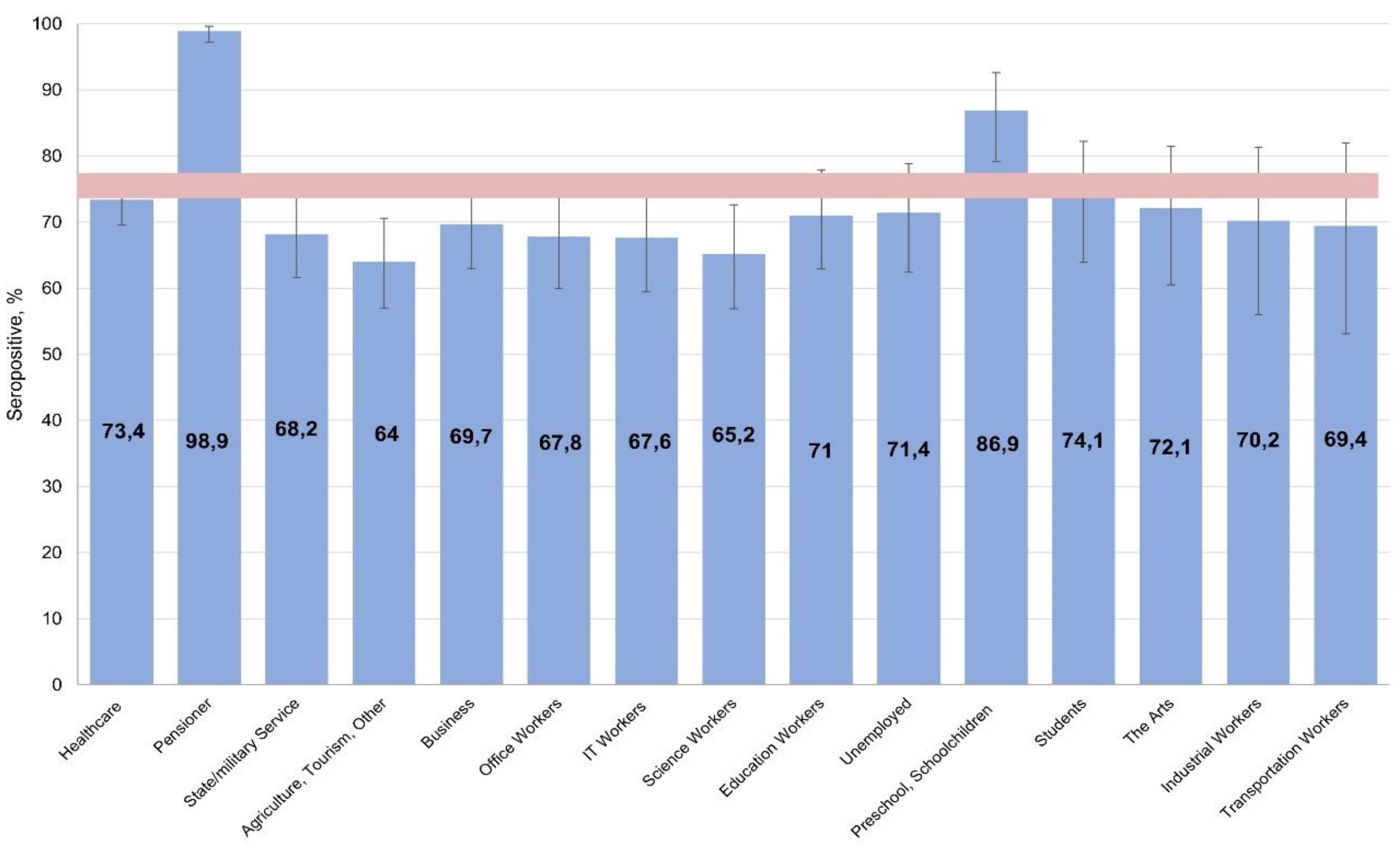

When assessing seroprevalence by activity, protective levels were found among children (preschoolers, schoolchildren) and pensioners, alongside lower levels in the 'scientist' and 'other' groups (

Figure 2).

Considering that most people in these categories had clearly reached middle age at the time of the survey, it can be assumed that the identified seroprevalence dependencies in different activity groups are in satisfactory agreement with the seroprevalence distribution by age.

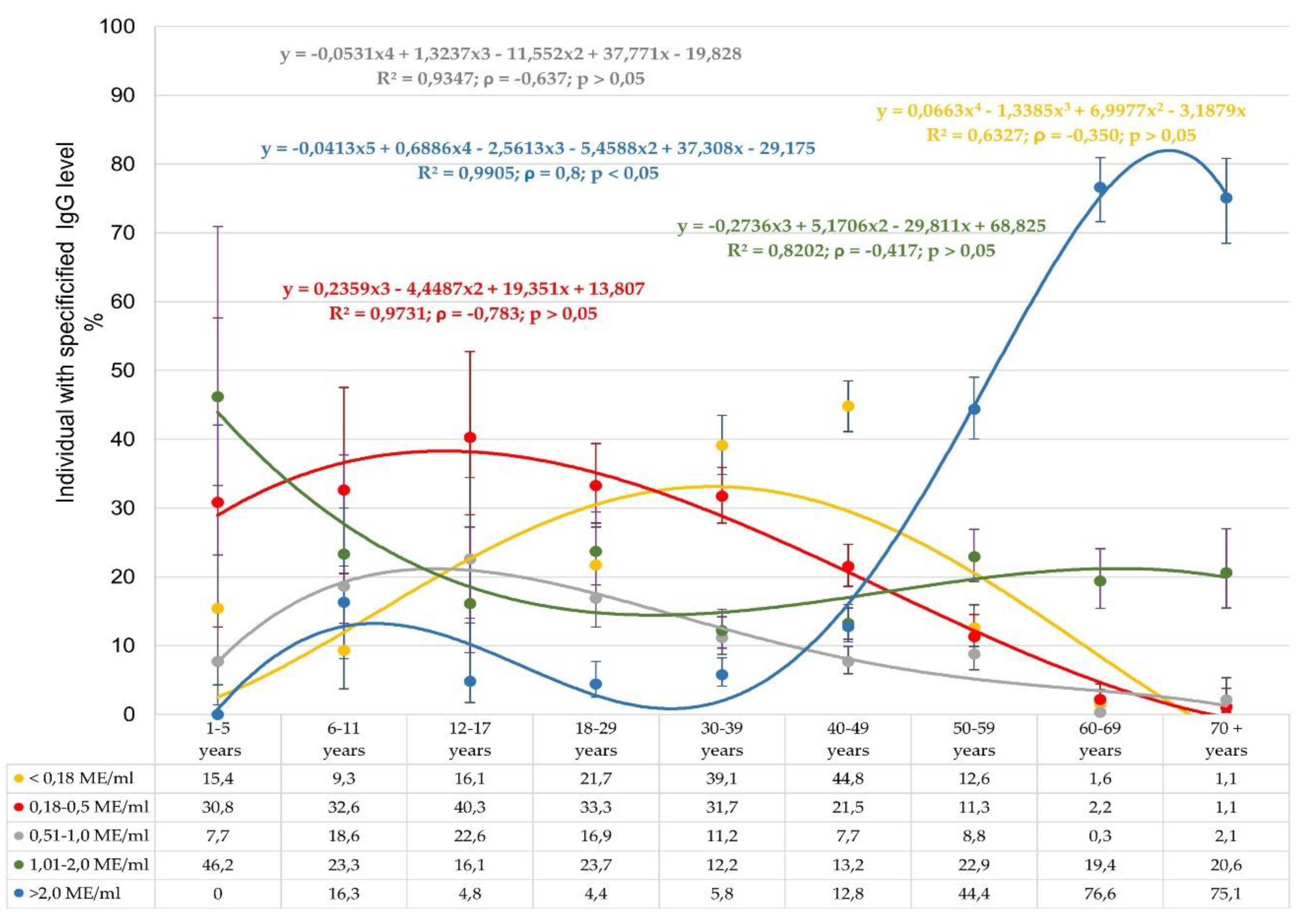

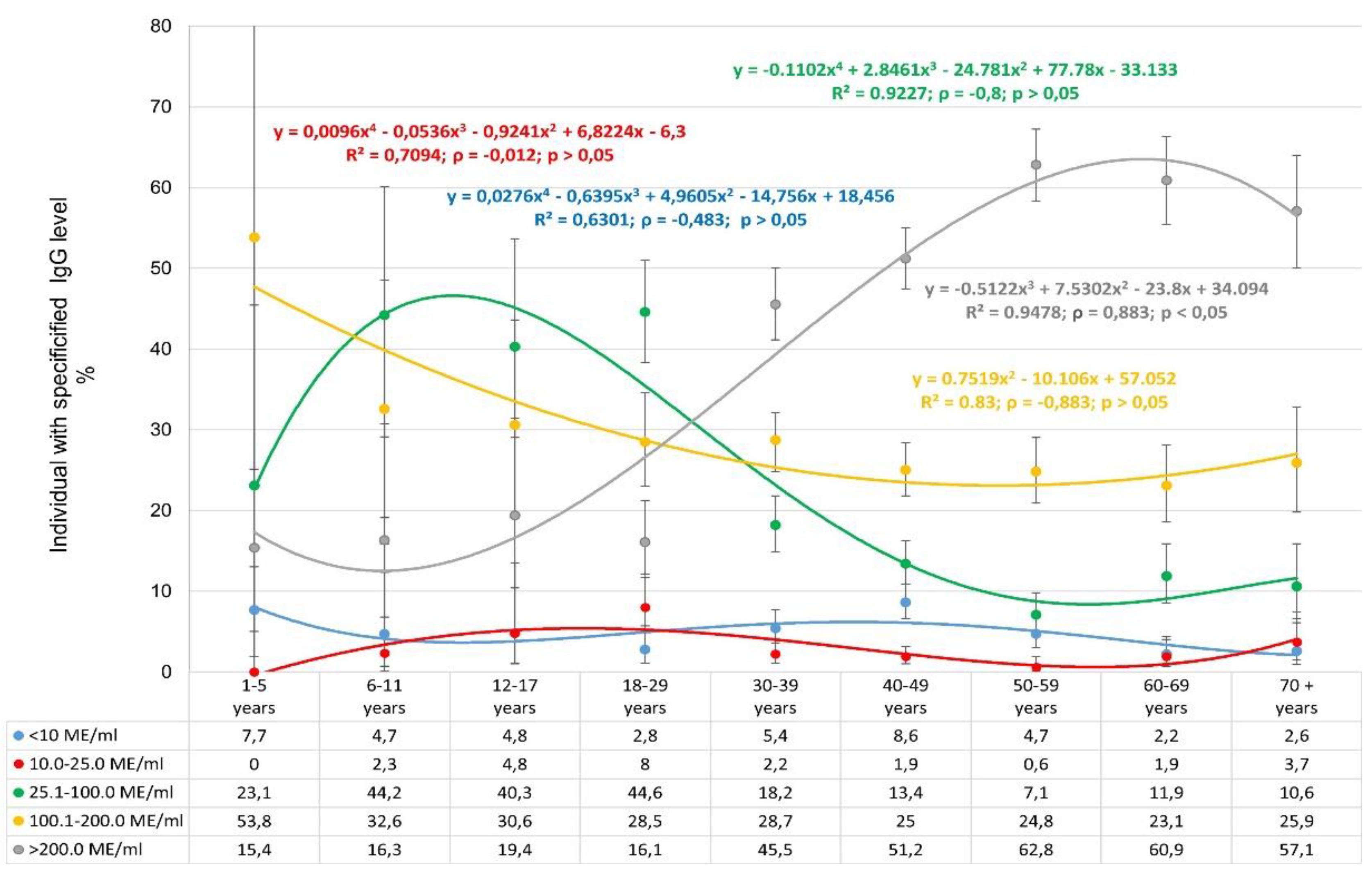

In addition to calculating seroprevalence, the study also quantitatively assessed anti-measles IgG levels in volunteers of different ages (

Figure 3).

These data indicate a pronounced heterogeneity in anti-measles IgG seroprevalence. The distribution of seronegative volunteers (< 0.18 IU/ml) indicates a low percentage of such individuals aged 1 to 29 years. The largest number was noted in the group aged 30-49 years, which is consistent with the age-related seroprevalence. As volunteer age increased, the share seronegative progressively decreased to almost zero. Regarding the distribution of weakly or moderately seropositive subjects (0.18-0.5, 0.51-1.0 IU/ml), most were detected among children (1-11 years old). A gradual decrease in the representation of such volunteers to 1.1% by the age of 70+ years was noted.

The greatest differences in

Figure 3 were noted across age groups in the form of the trend line for volunteers with maximum IgG levels (> 2 IU/ml). The group 'children aged 1-5 years' did not have any such individuals. In those aged 6-11 years, the share with such IgG levels increased to 16.3%, in the context of 90.7% seroprevalence (Figure 1) for the age group. In age groups spanning 12-39 years, a gradual decrease to 4.4% was seen. Subsequent growth to 12.8% (40-49 years) was noted, followed by an almost exponential growth to the maximum level of 75.1-76.6%. Such growth was accompanied by an increase in seroprevalence to 98.4-98.9% among individuals aged 60-70

+ years (

Figure 1).

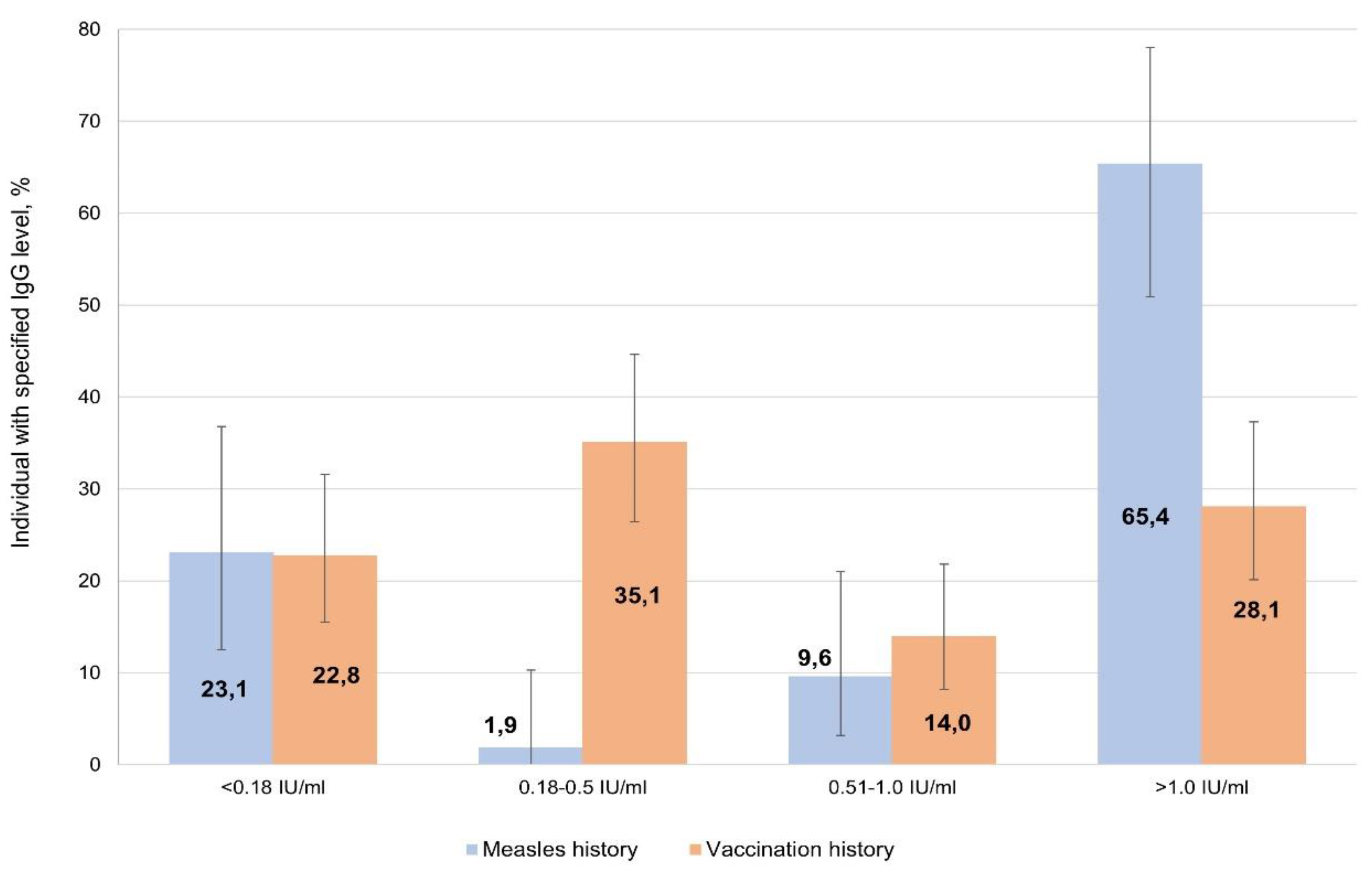

To compare the intensity of post-infectious and post-vaccination immunity, two groups of volunteers were selected: those who had recovered; and those who had been vaccinated. The former group were 52 people who confidently indicated a measles history in the past (1950-2021). The latter group, 'vaccinated', were 112 people able to confirm actual vaccination (1976-2024) with medical documentation; they also denied any history of illness in their anamnesis. Their serological findings are shown in

Figure 4.

Despite the insufficient reliability of the information that volunteers could provide about history (illness, vaccination), statistically significant differences were found between these two groups. The percentages of seronegative were comparable among those who had recovered (23.1%; 95% CI: 12.5-36.8) and those vaccinated (22.8%; 95% CI: 15.5-31.6). Among those recovered, the share of individuals with high IgG levels (> 1.0 IU/ml) was significantly higher at 65.4% (95% CI: 50.9-78.0). Among those vaccinated, such persons did not exceed 30% (28.1%; 95% CI: 20.1-37.3), and about a third of individuals (35.1%; 95% CI: 26.4-44.6) had low IgG levels (0.18 to 0.5 IU/ml).

It is interesting to note that among volunteers who confidently denied any history of illness or vaccination in their anamnesis (237 persons >30 years old), seroprevalence (70.3%; 95% CI: 67.2-73.2) did not differ from the cohort average. In half of such persons, IgG levels exceeded 1 IU/ml.

3.2. Rubella

The epidemiological situation regarding rubella in Serbia remains favorable overall. According to the official data of the Institute of Virology, Vaccines and Sera “Torlak”, no cases of rubella were detected in Serbia in the period from 2021 to 2023. This may indicate a high level of the herd immunity. Based on this assumption, we did not expect significant differences in seroprevalence in the Belgradian population (

Figure 5).

Stratification by age and activity did not reveal any significant differences between volunteers. Seropositivity was 94.7% (95% CI: 93.8-95.6) on average, with all age and professional groups of respondents falling within its confidence interval.

The distribution of IgG levels by age showed a number of specific features (

Figure 6).

First of all, the low share of seronegative individuals in all age categories is noteworthy. The shares of individuals with low IgG levels (10.1-25.0 IU/ml) are distributed similarly. In this context, the distribution of very high IgG level deserves special attention. In children aged 1-17 years, the share of individuals with such level varied from 15.4-19.4%. However, starting with volunteers aged 18-29 years and older, a sharp increase in the share of seropositive individuals with very high IgG level is observed. The maximum occurred in volunteers aged 60-69 years, amounting to 60.9% (95% CI: 55.5-66.1). It is interesting to note that the opposite trend was observed for volunteers with IgG levels in the range 25.1-100.0 IU/ml.

Anti-rubella IgG levels were compared in volunteers who had experienced rubella and those who had been vaccinated, as follows. The former subset (n=43) confidently indicated past illness (1965-1997). The latter subset (n=85) confirmed actual vaccination (1977-2024) with medical documentation and denied any history of illness in the anamnesis. No reliable differences were noted in the levels of post-infectious and post-vaccination rubella immunity. Most volunteers were in the high IgG level category (>100 IU/ml): 90.7% (95% CI: 77.9-97.4) among those who 'had experienced illness'; and 68.3% (95% CI: 57.1-78.1) among those who 'had been vaccinated'. Seronegative status did not exceed 2.5% in either group. Interestingly, among volunteers who confidently denied any history of illness or vaccination (386 people >30 years old), seroprevalence (92.7%; 95% CI: 89.7-94.9) was consistent with the cohort, with more than 70% having high IgG levels >100 IU/ml.

Thus, the obtained data indicate the protective seroprevalence level among the Belgradian population. This, together with data for Serbia overall, indicates the absence of epidemiological prerequisites for the spread of rubella in the Republic, including its capital, Belgrade.

3.3. Mumps

In the 2021-2023 period, the epidemiological situation regarding mumps in Serbia was characterized by sporadic cases (

Table 4). In this context, a similar situation would be expected in the Republic's largest city, Belgrade.

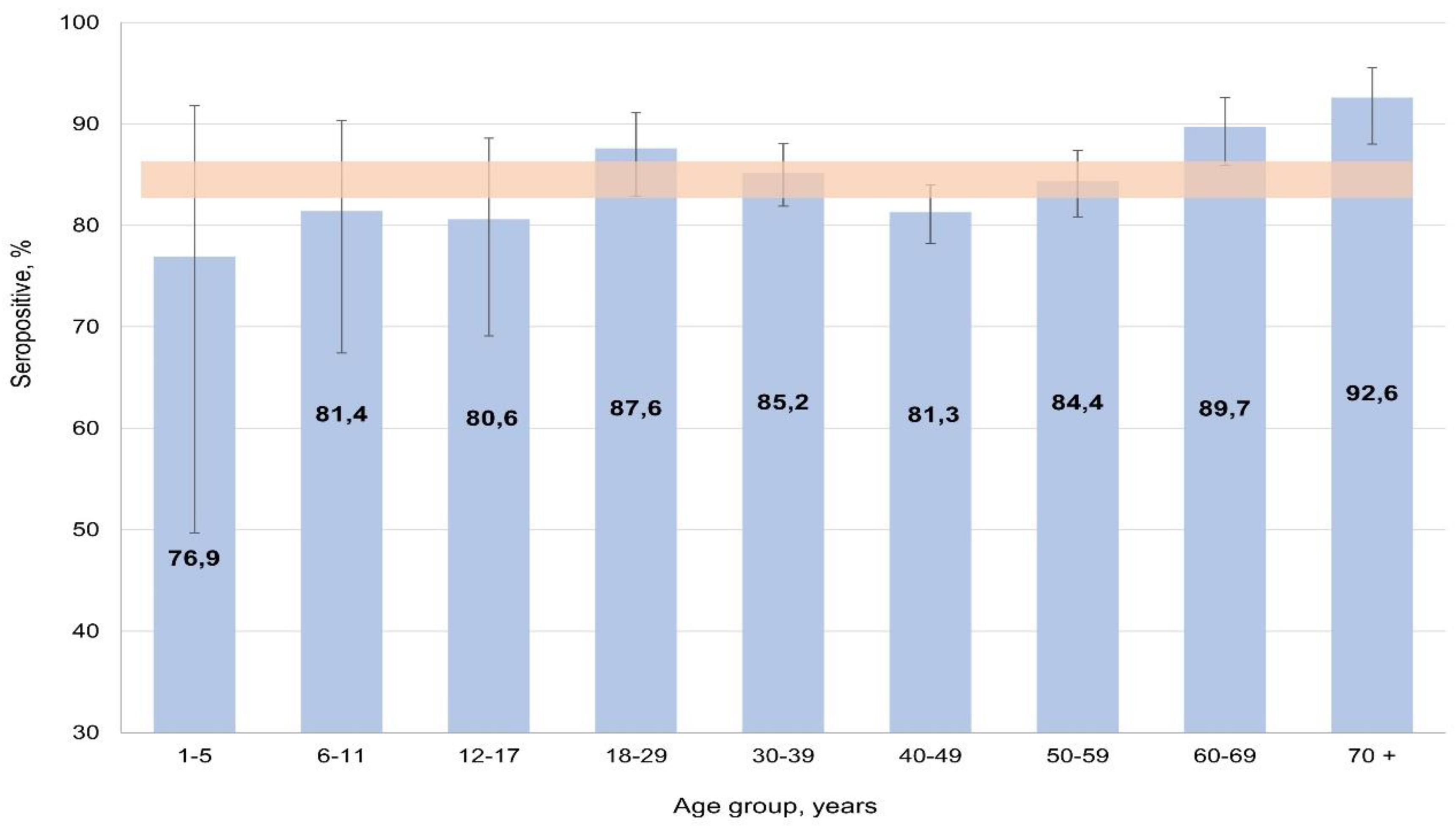

The most likely reason for this situation may be a high level of mumps herd immunity. According to the results, seropositivity in the cohort averaged 85.1% (95% CI: 83.7-86.4). Analysis of the age distribution of seropositivity showed that in the cohort it varied from 76.9% (95% CI: 49.7-91.8) in children aged 1-5 years to 92.6% (95% CI: 88.0-95.5) in those aged 70

+ persons. In almost all groups, differences were insignificant, only reaching significance with the 70

+ group (p < 0.05) (

Figure 7).

The distribution of seropositivity in relation to volunteer activity was in good agreement with the distribution by age. Significant difference was found only in the “pensioner” group (91.7%; 95% CI: 88.4-94.1) which, obviously, includes mostly elderly individuals. In all other groups, differences were insignificant.

Mumps seroprevalence was compared in volunteers who had experienced illness and those who had been vaccinated, as follows. The former subset (n=64) confidently indicated past illness (1953-2015). The latter subset (n=91) confirmed actual vaccination (1983-2024) with medical documentation and denied any history of illness in the anamnesis. No reliable differences were noted between post-infectious and post-vaccination immunity levels. In volunteers with a history of illness, 92.2% (95% CI: 82.7-97.4) were seropositive. In those with a history of vaccination, 85.9% (95% CI: 77.1-92.3) were seropositive.

It is interesting to note that among volunteers who confidently denied previous illness or vaccination (399 people >30 years old), seroprevalence (82.2%; 95% CI: 78.2-85.6) did not differ from the cohort average.

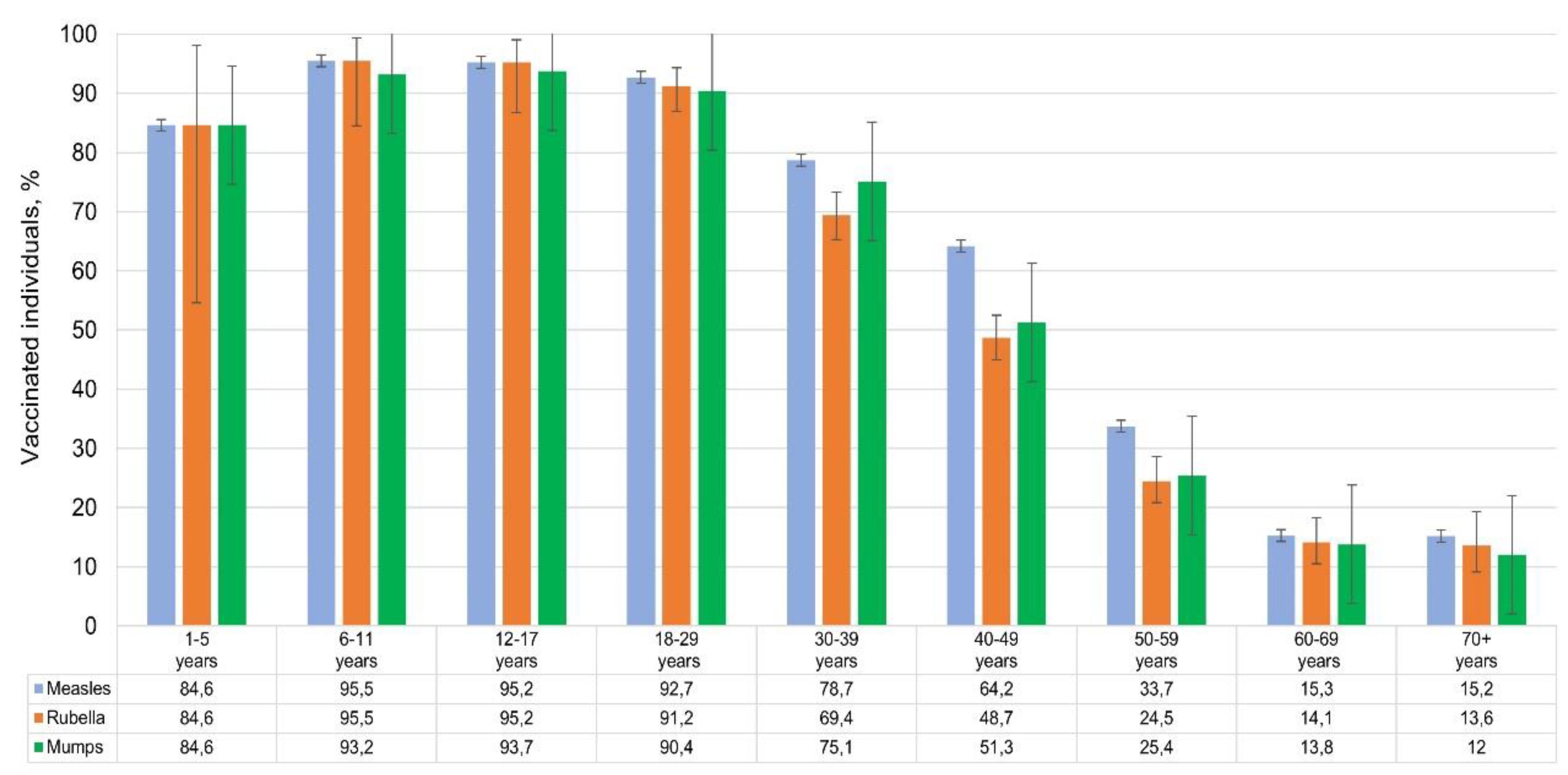

3.4. Vaccination Status

Unfortunately, we were unable to obtain complete and reliable information on the types of vaccines used. Of the volunteers included in the study (N = 2,533), the following reported vaccination: against measles – 1,473 people (56.1%; 95% CI: 54.2-58.0); against rubella – 1,258 people (47.9%; 95% CI: 46.0-49.8) and against mumps – 1,302 people (49.6%; 95% CI: 47.7-51.5). As expected, vaccination coverage for the three infections was roughly the same. It decreased with age from 95% in children's groups to 12-15% among volunteers over 60 years old (

Figure 8).

In over 70% of cases, volunteers did not provide vaccination data. Vaccination information confirmed by medical documentation (

Table 5) was provided for measles (112 individuals), for rubella (85 individuals), and for mumps (91 individuals). According to the National Drug Registry (NRL 2024,

https://registar.alims.gov.rs/), the main vaccine used in Serbia was a three-component (MMR) live vaccine (various manufacturers).

4. Discussion

We aimed here to provide, to our knowledge, the first of its kind: a comprehensive, cross-sectional evaluation (May 2024) of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) seroprevalence among the Belgradian population. As such, it offers insight into both immunity levels and potential areas of concern.

4.1. Measles Immunity: Potential Need for Catch-Up Vaccination

The measles virus is extremely contagious, and a very high level of herd immunity is required for successful public health control [

44]. Overall measles seroprevalence in Belgrade was found to be 74.7%, which is below the widely accepted protective threshold of 95% necessary for herd immunity. High seropositivity levels were observed among children aged 6-11 years (90.7%) and older adults (98.4%). Middle-aged adults (30-49 years) had significantly lower immunity (57.2%). This age group likely featured individuals who either missed vaccination, did not receive booster doses, or experienced waning immunity over time. Similar trends have been reported in European countries, where gaps in measles immunity among adults have been linked to insufficient past measures [

32,

45].

The high share of seropositive volunteers with high IgG level among preschool children is most likely due to recent revaccination of children in this age group. As for elderly and older individuals, high IgG level in the absence of vaccination indicate the presence of an anamnestic response to childhood illness. Analysis of IgG levels among people who have experienced illness versus those vaccinated confirms the duration and intensity of post-infectious measles immunity compared to the post-vaccination response.

The study data on measles herd immunity in Belgradian residents show a high level of seroprevalence, especially among preschool children, the elderly, and older volunteers. Caution is needed when interpreting the findings in the preschool group as its sample size was rather small. Some concern is caused by seroprevalence levels in the most active middle-aged population categories. A significant share of them had not reached the protective threshold. This may be due to deviations from the methodology of measles preventive immunization.

These findings suggest the need for targeted catch-up vaccination programs for middle-aged adults. Given that measles outbreaks have been increasingly reported across Europe, especially in unvaccinated individuals, ensuring adequate immunity in this age group is essential to prevent transmission and potential outbreaks in Belgrade.

4.2. Rubella: Sustained Immunity and Low Outbreak Risk

The study confirmed a high level of rubella seropositivity (94.8%) across all age groups. This is consistent with the absence of rubella cases in Serbia between 2021 and 2023 [

35], which is obviously due to successful achievement of herd immunity. These results suggest that the current immunization strategy has been effective in preventing rubella transmission, which supports the country’s efforts toward rubella elimination according to WHO Immunization Agenda 2030 [

46].

Notably, the highest IgG levels were observed in older individuals (60-69 years), likely reflecting past exposure to the virus before widespread vaccination was implemented. In contrast, younger individuals, particularly those in the '1-17 year' age group, exhibited lower (but still sufficient) IgG levels. This reinforces the role of routine childhood vaccination in maintaining high collective immunity. The gradual decline in vaccinated individuals across advancing age groups is expected keeping in mind the initiation of full MMR vaccination in the former Yugoslavia (1993).

An analysis conducted on a small sample of volunteers showed that immunity arising in response to vaccination is comparable to post-infectious immunity: most volunteers had high IgG level. Thus, the obtained data reflect seroprevalence values almost reaching the protective level in the Belgradian population. This, together with the data for Serbia as a whole, indicates the absence of epidemiological prerequisites for the spread of rubella in the Republic, including its capital, Belgrade.

4.3. Mumps Immunity: Areas for Improvement

Mumps seroprevalence was found to be 85.1%. The lowest was observed in children aged 1-5 years (76.1%), and the highest was seen in older adults (92.6%). This is below the accepted 95% protective threshold [

47,

48]. However, judging by official data [

35], it is sufficient to prevent the widespread spread of mumps in the Republic, although isolated cases are still possible. Given that mumps outbreaks have occurred in vaccinated populations due to waning immunity [

49], continued surveillance is necessary.

In this study, mumps serological status was assessed qualitatively, which does not allow comparison of IgG levels produced in response to infection and vaccination. The shares of seropositive individuals among those who had recovered, and among those who were vaccinated, were generally comparable.

4.4. Conclusions Common to the Three Infections

It is noteworthy that seroprevalence among middle-aged and older individuals who confidently denied any history of illness or vaccination (i.e., presumably had no contact with the viral pathogen) was high. Such a “discrepancy” is present for all infectious agents in this study. This may be due to the fact that elderly individuals frequently do not remember being sick in early childhood, or in some rare cases, they may have experienced asymptomatic infection [

50]. This assumption is supported by high IgG levels in most of these volunteers.

The overall findings emphasize the critical role of maintaining high vaccination coverage to prevent outbreaks of vaccine-preventable diseases. In the Republic of Serbia, anti-measles vaccination was first introduced in 1971. Combined vaccination (MMR) was made mandatory in 1996 as part of national vaccination program. In this context, the vaccination coverage of Belgradian residents who took part in the study was similar for the three infections and, as expected, decreased with age from 95% in children's groups to 12-15% among volunteers over 60 years of age.

While rubella immunity appears sufficient,

measles and mumps require additional efforts to close immunity gaps, particularly among middle-aged adults and young children.

We have identified this situation not only in Serbia, but also in other regions where similar studies were conducted in 2023: in St. Petersburg and the Leningrad Region in the Russian Federation [

51]

; as well as in the Kyrgyz Republic [

52]

. Many middle-aged adults are unaware of their immunization status and to address these issues, the following public health measures should be considered: i)

catch-up vaccination campaigns targeting adults with low measles immunity; and ii)

increased surveillance and monitoring of mumps immunity trends, particularly in children and middle-aged individuals.

This study provides valuable epidemiological data for guiding immunization policies. While Belgrade's population exhibits strong overall immunity to MMR, targeted interventions are required to address specific gaps in measles and mumps immunity. Maintaining high vaccination coverage, and considering booster doses for vulnerable age groups, will be crucial in achieving sustained protection against these diseases.

5. Limitations of the study

The authors would like to note several factors that might affect sample representativeness or conclusions reached through data analysis. Residents who are more involved with their health, and that of their loved ones (primarily women and healthcare workers), are more likely to take part in studies of this kind.

Caution is needed when interpreting the findings in the children groups (especially, preschool) as its sample size was rather small.

Initially, information about history (illness, vaccination) was taken from volunteer oral statements and from vaccination certificates they provided. The authors understand that for adult participants, there is a high probability that the volunteer may not remember prior illness or vaccination. In most cases, this data could not be verified using medical records.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.Y.P and A.A.T.; Data curation, S.A.E. and E.P.; Formal analysis, V.S.S. and V.A.I..; Funding acquisition, A.Y.P and V.Y.S.; Investigation − sample collecting, A.M.M., E.M.D., M.P.; Investigation − laboratory testing, I.V.D., E.P., O.B.Z., E.S.G.; Methodology, A.A.T; Project administration, S.A.E. and L.D.; Resources, L.D. and A.A.T.; Software, N.G.V., A.I. and O.V.C.; Supervision, A.Y.P and V.Y.S.; Validation, I.V.D. and A.A.T.; Visualization, E.P. and A.A.T.; Writing − original draft, V.S.S., S.A.E., L.D., M.P., E.S.R. and; Writing − review and editing, A.A.T.;.

Funding

This research was funded by Russian government (Russian government decree dated 18.04.2023, No. 972-р).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted according to the guidelines of the Declaration of Helsinki. It was approved by the Ethics Committees of the Saint Petersburg Pasteur Institute (protocol code 86, date of approval 17/08/2023) and the Institute of Virology, Vaccines and Sera “Torlak” (protocol code 467/2, date of approval 8/03/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interests.

References

- Naim, H.Y. Measles virus. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2015, 11, 21–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, S.B.; Chang, H.-L.; Chen, K.-T. Current Status of Mumps Virus Infection: Epidemiology, Pathogenesis, and Vaccine. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 1686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafayi, A.; Mohammadi, A. A Review on Rubella Vaccine: Iran (1975-2010). Arch Razi Inst. 2021, 76, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zverev, V.V.; Iuminova, N.V. Issues related to rubella, measles and epidemic parotiditis in the Russian Federation. Vopr Virusol. 2004, 49, 8–11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Samoilovich, E.O.; Kapustik, L.A.; Feldman, E.V.; Yermolovich, M.A.; Svirchevskaya, A.J.; Zakharenko, D.F.; Fletcher, M.A.; Titov, L.P. The immunogenicity and reactogenicity of the trivalent vaccine, Trimovax, indicated for prevention of measles, mumps, and rubella, in 12-month-old children in Belarus. Cent Eur J Public Health 2000, 8, 160–3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vittrup, D.M.; Laursen, A.C.L.; Malon, M.; Soerensen, J.K.; Hjort, J.; Buus, S.; Svensson, J.; Stensballe, L.G. Measles-mumps-rubella vaccine at 6 months of age, immunology, and childhood morbidity in a high-income setting: study protocol for a randomized controlled trial. Trials 2020, 21, 1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Pietrantonj, C.; Rivetti, A.; Marchione, P.; Debalini, M.G.; Demicheli, V. Vaccines for measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella in children. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021, 11, CD004407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semerikov, V.V.; Postanogova, N.O.; Sofronova, L.V.; Zubova, E.S.; Musikhina AYu Perminova, O.A.; Permiakova, M.A. Practical aspects of epidemiology and vaccine prevention domestic tetravaccine (measles-rubella-mumps) - immunization of premature babies. Epidemiology and Vaccinal Prevention 2022, 21, 95–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, P.; Jankovic, D.; Muscat, M.; Ben-Mamou, M.; Reef, S.; Papania, M.; Singh, S.; Kaloumenos, T.; Butler, R.; Datta, S. Measles and rubella elimination in the WHO Region for Europe: progress and challenges. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2017, 23, 504–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dotevall, L. The return of measles to Europe highlights the need to regain confidence in immunization. Acta Paediatrica 2019, 108, 1–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Perea, N. Measles again? Med Clin (Barc). 2024, 163, 344–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bichurina, M. , Timofeeva, Е., Zheleznova, N., Ignatyeva, N., Shulga, R., Lyalina, L., Degtyarev, О. Measles outbreak in a children’s hospital in Saint Petersburg in 2012. Zhurnal infektologii = Journal of Infectology 2013, 5, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bichurina, M.A.; Filipović-Vignjević, S.; Antipova, A.Y.; Bančević, M.; Lavrentieva, I.N. A herd immunity to measles and rubella viruses in the population of the Republic of Serbia. Russian Journal of Infection and Immunity = Infektsiya i immunitet 2021, 11, 171–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogusz, J.; Augustynowicz, E.; Wnukowska, N.; Paradowska-Stankiewicz, I. Measles in Poland in 2019. Przegl. Epidemiol. 2021, 75, 597–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnúsdóttir, S.D. Mislingar á Íslandi 2019. Læknafélag Reykjavikur 2019; 105, 161. [CrossRef]

- Arapović, J.; Sulaver, Ž.; Rajič, B.; Pilav, A. The 2019 measles epidemic in Bosnia and Herzegovina: What is wrong with the mandatory vaccination program? Bosn J Basic Med Sci. 2019, 19, 210–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keske, Ş.; Özsürekci, Y. ; Ergönül Ö An Alarming Emergence of Measles in Europe: Gaps Future Directions Balkan Med, J. 2024, 41, 321–323. [CrossRef]

- Al-Tawfiq, J.A.; Jain, N.; Tanasov, A.; Schlagenhauf, P. Measles matter: Recent outbreaks highlight the need for catch-up vaccination in Europe and around the globe. New Microbes New Infect. 2024, 58, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Thornton, J. Measles cases in Europe tripled from 2017 to 2018. BMJ 2019, 364, l634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Measles outbreak in the WHO European Region. Available online: https://news.un.org/ru/story/2024/02/1449742 (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- European Region reports highest number of measles cases in more than 25 years. Available online: https://www.who.int/europe/news/item/13-03-2025-european-region-reports-highest-number-of-measles-cases-in-more-than-25-years---unicef--who-europe (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Lanke, R.; Chimurkar, V. Measles Outbreak in Socioeconomically Diverse Sections: A Review. Cureus 2024, 16, e62879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Graf, W.; Bertram, F.; Dost, K.; Brennecke, A.; Kowalski, V.; van Rüth, V.; Nörz, D.S.; Wulff, B. Ondruschka, B., Püschel K., Pfefferle, S., Lütgehetmann, M., Heinrich, F. Immunity against measles, mumps, rubella, and varicella among homeless individuals in Germany − A nationwide multi-center cross-sectional study. Front Public Health 2024, 12, 1375151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Zarif, T.; Kassir, M.F.; Bizri, N.; Kassir, G.; Musharrafieh, U.; Bizri, A.R. Measles and mumps outbreaks in Lebanon: trends and links. BMC Infect Dis. 2020, 20, 244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gadroen, K.; Dodd, C.N.; Muscle, G.M.C.; de Ridder, M.A.J.; Weibel, D. , Mina, M.J., Grenfell, B.T., Sturkenboom, M.C.J. M., van de Vijver, D.A.M. C., de Swart, R.L. Impact and longevity of measles-associated immune suppression: a matched cohort study using data from the THIN general practice database in the UK. BMJ Open. 2018, 8, e021465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, K.; Govindaraj, G. Infections in Inborn Errors of Immunity with Combined Immune Deficiency: A Review. Pathogens 2023, 12, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, L.; Tan, C.; Wu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Ding, J.; Li, Y. The impact of temperature, humidity and closing school on the mumps epidemic: a case study in the mainland of China. BMC Public Health 2024, 24, 1632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siberry, G.K.; Patel, K.; Bellini, W.J.; Karalius, B.; Purswani, M.U.; Burchett, S.K.; Meyer, W.A., III.; Sowers, S.B.; Ellis, A.; Van Dyke, R.B. Immunity to Measles, Mumps, and Rubella in US Children With Perinatal HIV Infection or Perinatal HIV Exposure Without Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2015, 61, 988–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laue, T.; Junge, N.; Leiskau, C.; Mutschler, M.; Ohlendorf, J.; Baumann, U. Diminished measles immunity after paediatric liver transplantation − A retrospective, single-centre, cross-sectional analysis. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0296653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnce TGürocak, Ö.T.; Totur, G.; Yılmaz, Ş.; Ören, H.; Aydın, A. Waning of Humoral Immunity to Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in Children Treated for Acute Lymphoblastic Leukemia: A Single-Center Retrospective Cross-Sectional Analysis. Turk J Haematol. 2024, 41, 160–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schweitzer, L.; Miko, B.A.; Marcus RPereira, M.B. Infectious Disease Prophylaxis During and After Immunosuppressive Therapy. Kidney Int Rep. 2024, 9, 2337–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Measles on the rise again in Europe: time to check your vaccination status. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/measles-rise-again-europe-time-check-your-vaccination-status (accessed on 21 April 2025).

- Petrović, V., Šeguljev, Z., Radovanović, Z. Imunizacija protiv zaraznih bolesti; Novi Sad (Medicinski fakultet), Serbia, 2015; p. 168.

- Prévot-Monsacré, P.; Hamaide-Defrocourt, F.; Guyonvarch, O.; Masse, S.; Souty, C.; Mamou, T.; Hamel, J.; Anton, D.; Mathieu, P.; Vasseur, P.; Lévy-Bruhl, D.; Baroux, N.; Rossignol, L.; Vaillant, L.; Guerrisi, C.; Hanslik, T.; Dina, J.; Blanchon, T. What is the relevancy of a surveillance of mumps without a systematic laboratory confirmation in highly immunized populations? Epidemiology of suspected and biologically confirmed mumps cases seen in general practice in France between 2014 and 2020. Vaccine 2024, 42, 1065–1070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Public Health of Serbia "Dr Milan Jovanović Batut". Personal communication.

- Ristić, M., Milošević, V., Medić, S., Malbaša J.D., Rajčević, S., Boban, J., Petrović, V. Sero-epidemiological study in prediction of the risk groups for measles outbreaks in Vojvodina, Serbia. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0216219. [CrossRef]

- Patić, A., Štrbac, M., Petrović, V., Milošević, V., Ristić, M., Hrnjaković Cvjetković, I, Medić S. Seroepidemiological study of rubella in Vojvodina, Serbia: 24 years after the introduction of the MMR vaccine in the national immunization programme. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0227413. [CrossRef]

- Rodriges Del Águila, M.; González-Ramírez, A. Sample size calculation. Allergol Immunopathol (Madr) 2014, 42, 485–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Popova AYu Totolian, A.A. Methodology for assessing population immunity to the SARS-CoV-2 virus in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. Russian Journal of Infection and Immunity = Infektsiya i immunitet 2021, 11, 609–616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wald, A.; Wolfowitz, J. Confidence limits for continuous distribution functions. Ann. Math. Statist. 1939, 10, pp. 105–118. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2235689 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Agresti, A.; Coull, B.A. Approximate is better than “exact” for interval estimation of binomial proportions. Am Stat. 1998, 52, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radar calculators. Available online: https://radar-research.ru/instruments/calculators. (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Neugebauer, M.; Ebert, M.; Vogelmann, R. Beurteilung des neuen Masernschutzgesetzes in Deutschland: Ergebnisse einer deutschlandweiten Befragung. Z. Evid. Fortbild. Qual. Gesundhwes. 2020, 158, 74–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Black, F.L. The role of herd immunity in control of measles. Yale J Biol Med. 1982, 55(3-4), 351–360. [PubMed]

- Friedrich, N.; Poethko-Müller, C.; Kuhnert, R.; Matysiak-Klose, D.; Koch, J.; Wichmann, O.; Santibanez, S.; Mankertz, M. Seroprevalence of Measles-, Mumps-, and Rubella-specific antibodies in the German adult population – cross-sectional analysis of the German Health Interview and Examination Survey for Adults (DEGS1). Lancet Reg Health Eur. 2021, 7, 100128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WHO Immunization Agenda 2030: A Glibal Strategy to Leave No One Behind. Available online: https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/strategies/ia2030 (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- 47 Lewnard, J.A.; GradY. H. Vaccine waning and mumps re-emergence in the United States. Sci. Transl. Med. 2018, 10, eaao5945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, C.; Somma, G.; Treglia, M.; Pallocci, M.; Passalacqua, P.; Di Giampaolo, L.; Coppeta, L. Questionable Immunity to Mumps among Healthcare Workers in Italy-A Cross-Sectional Serological Study. Vaccines (Basel) 2024, 12, 522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, L.; Grenfell, B.T.; Mina, M.J. Waning immunity and re-emergence of measles and mumps in the vaccine era. Curr Opin Virol. 2020, 40, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henle, G.; Henle, W.; Wendell, K.K.; Rosenberg, P. Isolation of mumps virus from human beings with induced apparent or inapparent infections. J Exp Med. 1948, 88, 223–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, A.Y.; Egorova, S.A.; Smirnov, V.S.; Ezhlova, E.B.; Milichkina, A.M.; Melnikova, A.A.; Bashketova, N.S.; Istorik, O.A.; Buts, L.V.; Ramsay, E.S.; Drozd, I.V.; Zhimbaeva, O.B.; Drobyshevskaya, V.G.; Danilova, E.M.; Ivanov, V.A.; Totolian, A.A. Herd immunity to vaccine preventable infections in Saint Petersburg and the Leningrad region: serological status of measles, mumps, and rubella. Russian Journal of Infection and Immunity = Infektsiya i immunitet 2024, 14, 1187–1208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popova, A.Y.; Smirnov, V.S.; Egorova, S.A.; Nurmatov, Z.S.; Milichkina, A.M.; Drozd, I.V.; Dadanova, G.S.; Zhumagulova, G.D.; Danilova, E.M.; Kasymbekov, Z.O.; Drobyshevskaya, V.G.; Sattarova, G.Z.; Zhimbaeva, O.B.; Ramsay, E.S.; Nuridinova, Z.N.; Ivanov, V.A.; Urmanbetova, A.K.; Totolian, A.A. Collective Immunity to the Measles, Mumps, and Rubella Viruses in the Kyrgyz Population. Vaccines 2025, 13, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).