Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

02 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Guerra FM, Bolotin S, Lim G, Heffernan J, Deeks SL, Li Y, Crowcroft NS. The basic reproduction number (R0) of measles: a systematic review. Lancet Infect Dis. 2017 Dec;17(12):e420-e428. Epub 2017 Jul 27. PMID: 28757186. [CrossRef]

- Plans-Rubió, P. Are the Objectives Proposed by the WHO for Routine Measles Vaccination Coverage and Population Measles Immunity Sufficient to Achieve Measles Elimination from Europe? Vaccines 2020, 8, 218. [CrossRef]

- Immunization Agenda 2030: A Global Strategy to Leave No One Behind https://www.who.int/teams/immunization-vaccines-and-biologicals/strategies/ia2030, accessed July 5, 2024.

- European Immunization Agenda 2030. Copenhagen:WHO Regional Office for Europe; 2021. Licence: CC BY-NC-SA 3.0 IGO. ISBN: 978-92-890-5605-2.

- Calderón et al., The Influence of Antivaccination Movements on the Re-emergence of Measles, J Pure Appl Microbiol, 2019, 13(1), 127-132, 5302. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Diseases Control, Measles on the rise in the EU/EEA: considerations for public health response, 16 February 2024 https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/measles-eu-threat-assessment-brief-february-2024.pdf, accessed June 27, 2024.

- Muscat M, Ben Mamou M, Reynen-de Kat C, Jankovic D, Hagan J, Singh S, Datta SS. Progress and Challenges in Measles and Rubella Elimination in the WHO European Region. Vaccines (Basel). 2024 Jun 20;12(6):696. PMID: 38932424; PMCID: PMC11209032. [CrossRef]

- European Centre for Diseases Control, Weekly Communicable Disease Threats Report, Week 41, 5 - 11 October 2024 https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/sites/default/files/documents/communicable-disease-threats-report-week-41-2024.pdf accessed October 15, 2024.

- Hayman DTS. Measles vaccination in an increasingly immunized and developed world. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2019;15(1):28-33. Epub 2018 Sep 19. PMID: 30156949; PMCID: PMC6363159. [CrossRef]

- Manual for the Laboratory-based Surveillance of Measles, Rubella, and Congenital Rubella Syndrome. Laboratory testing for determination of population immune status https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/chapter-9-manual-for-the-laboratory-based-surveillance-of-measles-rubella-and-congenital-rubella-syndrome, accessed December 20, 2024.

- Kafatos G, Andrews N, McConway KJ, Anastassopoulou C, Barbara C, De Ory F, Johansen K, Mossong J, Prosenc K, Vranckx R, Nardone A, Pebody R, Farrington P. Estimating seroprevalence of vaccine-preventable infections: is it worth standardizing the serological outcomes to adjust for different assays and laboratories? Epidemiol Infect. 2015 Aug;143(11):2269-78. Epub 2014 Nov 25. PMID: 25420586; PMCID: PMC9151055. [CrossRef]

- Andrews N, Tischer A, Siedler A, Pebody RG, Barbara C, Cotter S, Duks A, Gacheva N, Bohumir K, Johansen K, Mossong J, Ory Fd, Prosenc K, Sláciková M, Theeten H, Zarvou M, Pistol A, Bartha K, Cohen D, Backhouse J, Griskevicius A. Towards elimination: measles susceptibility in Australia and 17 European countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008 Mar;86(3):197-204. PMID: 18368206; PMCID: PMC2647410. [CrossRef]

- National Center for Disease Control. Evolution analysis of communicable diseases under surveillance, Annual reports: https://insp.gov.ro/centrul-national-de-supraveghere-si-control-al-bolilor-transmisibile-cnscbt/rapoarte-anuale/ Romanian, accessed November 12, 2024.

- Donadel M, Stanescu A, Pistol A, Stewart B, Butu C, Jankovic D, Paunescu B, Zimmerman L. Risk factors for measles deaths among children during a Nationwide measles outbreak - Romania, 2016-2018. BMC Infect Dis. 2021 Mar 19;21(1):279. PMID: 33740895; PMCID: PMC7976682. [CrossRef]

- National Institute of Public Health. National Centre for Communicable Diseases Surveillance and Control, Monthly reports. Romanian. Available from: https://insp.gov.ro/informari-lunare/, accessed November 12, 2024.

- Stanescu A, Ruta SM, Cernescu C, Pistol A. Suboptimal MMR Vaccination Coverages-A Constant Challenge for Measles Elimination in Romania. Vaccines (Basel). 2024 Jan 22;12(1):107. PMID: 38276679; PMCID: PMC10819452. [CrossRef]

- Eurostat, the statistical office of the European Union, reference metadata, Fertility. https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/cache/metadata/en/demo_fer_esms.htm, accessed June 10, 2024.

- Steven K. Thompson, Sampling. Third Edition, 2012. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics ISBN: 978-0-470-40231-3).

- National Institute of Statistics. Romanian. http://statistici.insse.ro:8077/tempo-online/#/pages/tables/insse-table, accessed June 10, 2024.

- Wiedermann, U., Garner-Spitzer, E. & Wagner, A. Primary vaccine failure to routine vaccines: why and what to do? Hum. Vaccin. Immunother. 12, 239–243 (2016). [CrossRef]

- Pambudi N.A., Sarifudin A., Gandidi I.M., Romadhon R. Vaccine cold chain management and cold storage technology to address the challenges of vaccination programs Energy Rep., 8 (2022), pp. 955-972. [CrossRef]

- Griffin DE, The Immune Response in Measles: Virus Control, Clearance and Protective Immunity, Viruses 2016, 8(10), 282. [CrossRef]

- Nic Lochlainn LM, de Gier B, van der Maas N, Strebel PM, Goodman T, van Binnendijk RS, de Melker HE, Hahné SJM. Immunogenicity, effectiveness, and safety of measles vaccination in infants younger than 9 months: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019 Nov;19(11):1235-1245. Epub 2019 Sep 20. PMID: 31548079; PMCID: PMC6838664. [CrossRef]

- Gonçalves G, Frade J, Nunes C, Mesquita JR, Nascimento MS. Persistence of measles antibodies, following changes in the recommended age for the second dose of MMR-vaccine in Portugal. Vaccine. 2015 Sep 22;33(39):5057-63. [CrossRef]

- Kang HJ, Han YW, Kim SJ, Kim YJ, Kim AR, Kim JA, Jung HD, Eom HE, Park O, Kim SS. An increasing, potentially measles-susceptible population over time after vaccination in Korea. Vaccine. 2017 Jul 24;35(33):4126-4132. Epub 2017 Jun 29. PMID: 28669617. [CrossRef]

- Ghafoori F, Mokhtari-Azad T, Foroushani AR, Farahmand M, Shadab A, Salimi V. Assessing seropositivity of MMR antibodies in individuals aged 2-22: evaluating routine vaccination effectiveness after the 2003 mass campaign-a study from Iran’s National Measles Laboratory. BMC Infect Dis. 2024 Jul 12;24(1):696. PMID: 38997625; PMCID: PMC11245767. [CrossRef]

- Williamson KM, Faddy H, Nicholson S, Stambos V, Hoad V, Butler M, Housen T, Merritt T, Durrheim DN. A Cross-Sectional Study of Measles-Specific Antibody Levels in Australian Blood Donors-Implications for Measles Post-Elimination Countries. Vaccines (Basel). 2024 Jul 22;12(7):818. PMID: 39066455; PMCID: PMC11281562. [CrossRef]

- Franconeri L, Antona D, Cauchemez S, Lévy-Bruhl D, Paireau J. Two-dose measles vaccine effectiveness remains high over time: A French observational study, 2017-2019. Vaccine. 2023 Sep 7;41(39):5797-5804. Epub 2023 Aug 14. PMID: 37586955. [CrossRef]

- Plotkin S. A. et. al., Plotkin’s vaccines, 7th Edition, Elsevier, 2018.

- Robert A, Suffel AM, Kucharski AJ. Long-term waning of vaccine-induced immunity to measles in England: a mathematical modelling study. Lancet Public Health. 2024 Oct;9(10):e766-e775. Epub 2024 Sep 26. PMID: 39342948. [CrossRef]

- Bitzegeio J, Majowicz S, Matysiak-Klose D, Sagebiel D, Werber D. Estimating age-specific vaccine effectiveness using data from a large measles outbreak in Berlin, Germany, 2014/15: evidence for waning immunity. Euro Surveill. 2019 Apr;24(17):1800529. PMID: 31039834; PMCID: PMC6628761. [CrossRef]

- Klein, S.L.; Flanagan, K.L. Sex differences in immune responses. Nat. Rev. Immunol. 2016, 16. [CrossRef]

- Nasika A, Bogogiannidou Z, Mouchtouri VA, Dadouli K, Kyritsi MA, Vontas A, Voulgaridi I, Tsinaris Z, Kola K, Matziri A, Lianos AG, Kalala F, Petinaki E, Speletas M, Hadjichristodoulou C. Measles Immunity Status of Greek Population after the Outbreak in 2017-2018: Results from a Seroprevalence National Survey. Vaccines (Basel). 2023;11(7):1220. [CrossRef]

- Marchi S, Remarque EJ, Viviani S, Rizzo C, Monteverde Spencer GT, Coluccio R, Montomoli E, Trombetta CM. Measles immunity over two decades in two large Italian Regions: How far is the elimination goal? Vaccine. 2021 Sep 24;39(40):5928-5933. Epub 2021 Aug 26. PMID: 34456073. [CrossRef]

- Grassi T, Bagordo F, Rota MC, Dettori M, Baldovin T, Napolitano F, Panico A, Massaro E, Marchi S, Furfaro G, Immordino P, Savio M, Gabutti G; Sero-epidemiological Study Group. Seroprevalence of measles antibodies in the Italian general population in 2019-2020. Vaccine. 2024 Sep 17;42(22):126012. [CrossRef]

- Bugdaycı Yalcın BN, Sasmaz CT. Measles Seroprevalence and Related Factors in Women Aged 15-49 Years Old, in Mersin, Turkey. Iran J Public Health. 2023 Mar;52(3):593-602. PMID: 37124900; PMCID: PMC10135515. [CrossRef]

- Gieles NC, Mutsaerts EAML, Kwatra G, Bont L, Cutland CL, Jones S, Moultrie A, Madhi SA, Nunes MC. Measles seroprevalence in pregnant women in Soweto, South Africa: a nested cohort study. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 Apr;26(4):515.e1-515.e4. Epub 2019 Nov 13. PMID: 31730905. [CrossRef]

- Janaszek,W.;Slusarczyk, J. Immunity against measles in populations of women and infants in Poland. [CrossRef]

- Ben-Chetrit E, Oster Y, Jarjou’i A, Megged O, Lachish T, Cohen MJ, Stein-Zamir C, Ivgi H, Rivkin M, Milgrom Y, Averbuch D, Korem M, Wolf DG, Wiener-Well Y. Measles-related hospitalizations and associated complications in Jerusalem, 2018-2019. Clin Microbiol Infect. 2020 May;26(5):637-642. [CrossRef]

- Principi N, Esposito S. Early vaccination: a provisional measure to prevent measles in infants. Lancet Infect Dis. 2019;19(11):1157-1158. [CrossRef]

- Mathew JL, Wagner AL, Ratho RK, Patel PN, Suri V, Bharti B, Carlson BF, Dutta S, Singh MP, Boulton ML. Maternally transmitted anti-measles antibodies, and susceptibility to disease among infants in Chandigarh, India: A prospective birth cohort study. PLoS One. 2023 Oct 3;18(10):0287110. [CrossRef]

- Moghadas, S. M.; Alexander, M. E.; Sahai, B.M. Waning herd immunity: A challenge for eradication of measles, Journal of Mathematics, Vol.38, Nr. 5, 2008.

| Age group | Females N=446 |

Males N=513 |

Total number N=959 |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25-29 years | 90 | 103 | 193 |

| 30-34 years | 112 | 129 | 241 |

| 35-40 years | 112 | 131 | 243 |

| 40-44 years | 132 | 150 | 282 |

| Seroprevalence of IgG anti measles antibodies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total N=959 |

Females N=446 |

Males N=513 |

||

| Age group | N(%) of positives |

N(%) of positives |

N(%) of positives |

p |

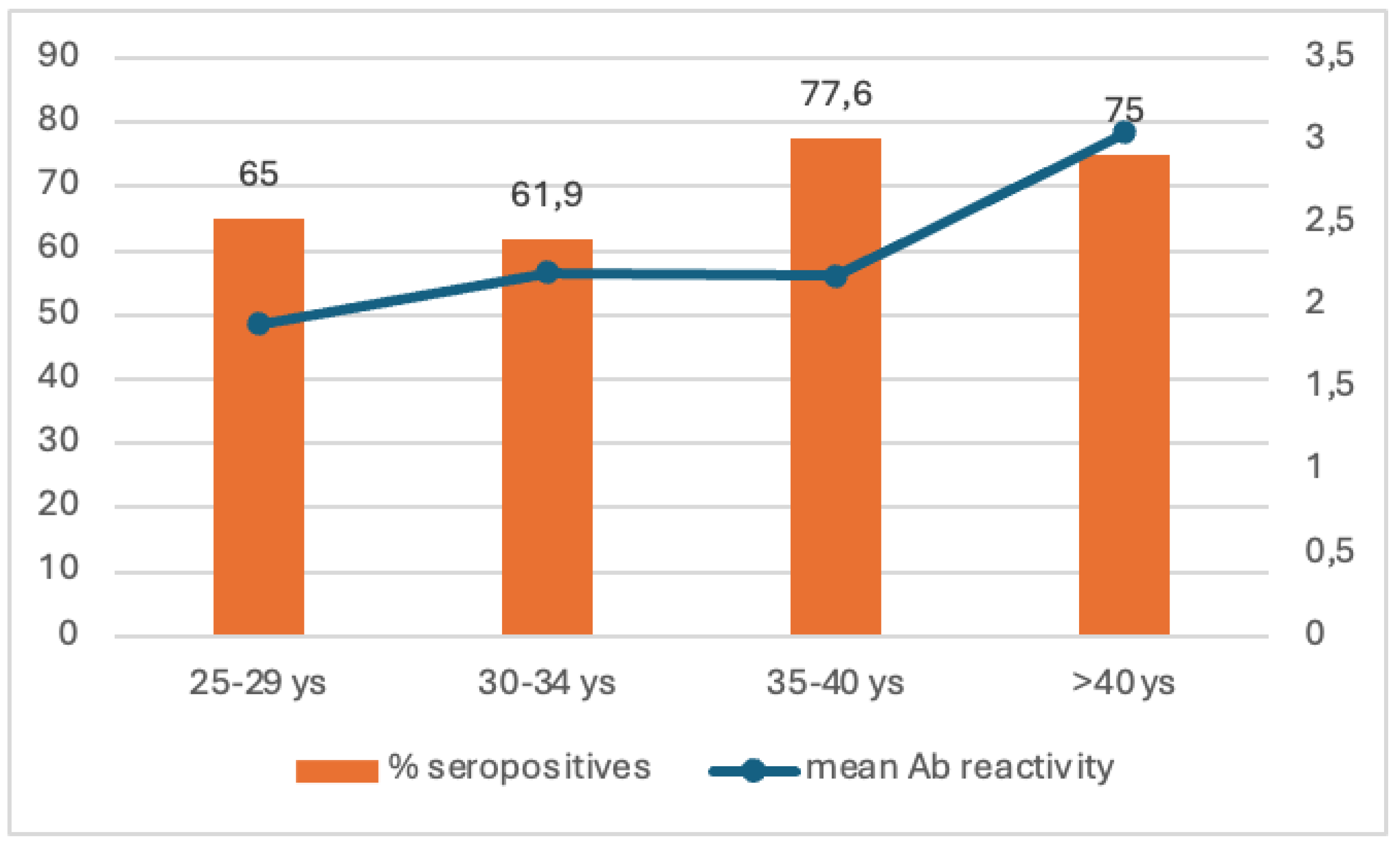

| 25-29 y | 128 (66.3%) | 55 (61.1%) | 73 (70.9%) | 0.153 |

| 30-34 y | 176 (73%) | 88 (78.6%) | 88 (68.2%) | 0.708 |

| 35-39 y | 199 (81,9%) | 90 (80.4%) | 109 (83.2%) | 0.565 |

| 40-44 y | 235 (83.3%) | 112 (84.8%) | 123 (82%) | 0.521 |

|

Total positives |

738 (77%) |

345 (77.4%) | 393 (76.6%) | 0.796 |

| Region | Age group | |||||||

| 25-29 y | 30-34 y | 35-39 y | 40-44 y | |||||

| National | 66.3% | p | 73.0% | p | 81.9% | p | 83.3% | p |

| North West vs | 51.5% | 0.101 | 64.3% | 0.331 | 78.9% | 0.657 | 94.6% | 0.073 |

| Center vs | 76.9% | 0.413 | 84.2% | 0.285 | 85.7% | 0.718 | 80.0% | 0.703 |

| South vs | 66.7% | 0.967 | 84.8% | 0.09 | 81.0% | 0.889 | 82.4% | 0.874 |

| South East vs | 56.5% | 0.35 | 61.3% | 0.173 | 75.0% | 0.376 | 81.1% | 0.737 |

| South West vs | 69.0% | 0.773 | 63.0% | 0.169 | 79.6% | 0.705 | 87.5% | 0.433 |

| West vs | 84.6% | 0.05 | 82.8% | 0.255 | 84.8% | 0.682 | 75.0% | 0.242 |

| Bucharest-Ilfov vs | 73.3% | 0.579 | 71.4% | 0.75 | 95.5% | 0.958 | 83.3% | 0.355 |

| North East vs | 63.0% | 0.734 | 76.2% | 0.874 | 82.4% | 0.103 | 76.0% | 1 |

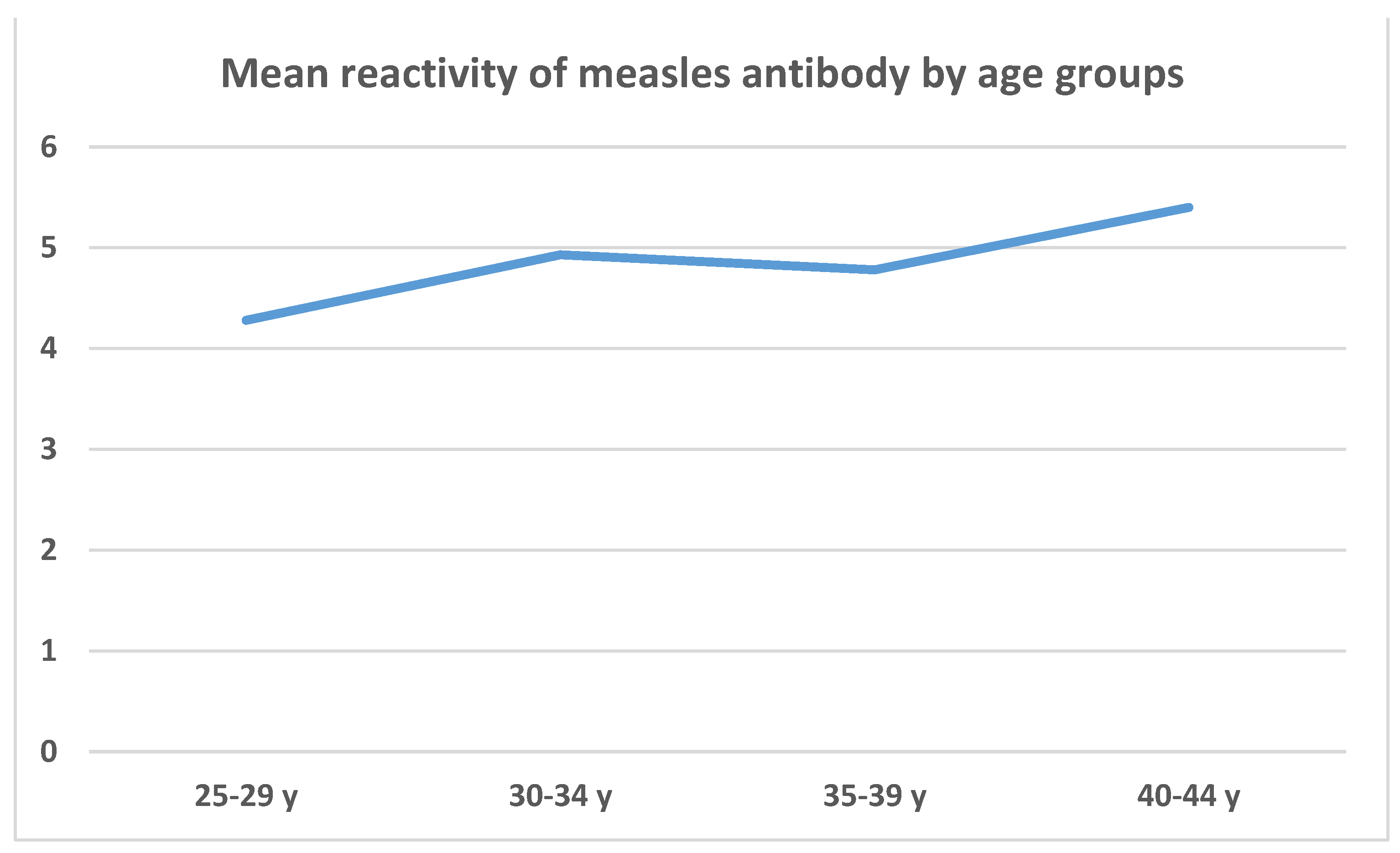

| Age group compared | Age group to be compared with | Mean measles reactivity differences between age groups | p |

|---|---|---|---|

| 25-29 y | 30-34 y | -0.656 | 0.870 (-2.293; 0.979) |

| 35-39 y | -0.505 | 0.772 (-1.591; 0.580) | |

| 40-44 y | -1.127 | 0.057 (-2.275; 0.020) | |

| 30-34 y | 35-39 y | 0.151 | 1.000 (-1.386; 1.689) |

| 40-44 y | -0.470 | 0.966 (-2.052; 1.112) | |

| 35-39 y | 40-44 y | -0.621 | 0.471 (-1.621; 0.377) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).