Submitted:

15 June 2023

Posted:

15 June 2023

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Participants

2.2. Laboratory Analysis

2.3. Statistical Analysis

2.4. Ethical Statement

3. Results

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- van Panhuis, W.G.; Grefenstette, J.; Jung, S.Y.; Chok, N.S.; Cross, A.; Eng, H.; Lee, B.Y.; Zadorozhny, V.; Brown, S.; Cummings, D.; et al. Contagious Diseases in the United States from 1888 to the Present. New England Journal of Medicine 2013, 369, 2152–2158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, F.; Shefer, A.; Wenger, J.; Messonnier, M.; Wang, L.Y.; Lopez, A.; Moore, M.; Murphy, T. V.; Cortese, M.; Rodewald, L. Economic Evaluation of the Routine Childhood Immunization Program in the United States, 2009. Pediatrics 2014, 133, 577–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Benefits from Immunization During the Vaccines for Children Program Era — United States, 1994–2013. Available online: https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/preview/mmwrhtml/mm6316a4.htm (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Measles. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/measles?gclid=CjwKCAiA9NGfBhBvEiwAq5vSy0LoZb6eUZCrIeVfmg9FcNW4VdNHQ59bwBZj0A0edN3FVE1Nbgfu4xoCFIUQAvD_BwE (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- History of Measles Vaccination. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/spotlight/history-of-vaccination/history-of-measles-vaccination?topicsurvey=ht7j2q)&gclid=Cj0KCQiAutyfBhCMARIsAMgcRJRuqLNP-QtuKj1VVPoeHCzxgEtm-NsexSb7H-bJSaOWKg9qUQV3EDUaAnF3EALw_wcB (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Moss, W.J.; Shendale, S.; Lindstrand, A.; O’Brien, K.L.; Turner, N.; Goodman, T.; Kretsinger, K. Feasibility Assessment of Measles and Rubella Eradication. Vaccine 2021, 39, 3544–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilder-Smith, A.B.; Qureshi, K. Resurgence of Measles in Europe: A Systematic Review on Parental Attitudes and Beliefs of Measles Vaccine. J Epidemiol Glob Health 2020, 10, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Panagiotopoulos, T.; Antoniadou, I.; Valassi-Adam, E.; Berger, A. Increase in Congenital Rubella Occurrence after Immunisation in Greece: Retrospective Survey and Systematic Review. BMJ : British Medical Journal 1999, 319, 1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Σημεία, Σ. Τμήμα Επιδημιολογικής Επιτήρησης Και Παρέμβασης ΕΠΙΔHΜΙOΛOΓΙΚA ΔΕΔOΜΕΝA ΓΙA ΤHΝ ΙΛAΡA ΣΤHΝ ΕΛΛAΔA 2018 (ΣΥΣΤHΜA ΥΠOΧΡΕΩΤΙΚHΣ ΔHΛΩΣHΣ ΝOΣHΜAΤΩΝ).

- Ιλαρά - Εθνικός Oργανισμός Δημόσιας Υγείας. Available online: https://eody.gov.gr/disease/ilara/ (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Gianniki, M.; Siahanidou, T.; Botsa, E.; Michos, A. Measles Epidemic in Pediatric Population in Greece during 2017–2018: Epidemiological, Clinical Characteristics and Outcomes. PLoS One 2021, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Measles Reported Cases and Incidence. Available online: https://immunizationdata.who.int/pages/incidence/measles.html?CODE=GRC&YEAR= (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Σμιμα Επιδθμιολογικισ Επιτιρθςθσ Και Παρζμβαςθσ ΕΠΙΔHΜΙOΛOΓΙΚA ΔΕΔOΜΕΝA ΓΙA ΣHΝ ΙΛAΡA ΣHΝ ΕΛΛAΔA.

- Τμήμα Επιδημιολογικής Επιτήρησης Και Παρέμβασης ΕΠΙΔHΜΙOΛOΓΙΚA ΔΕΔOΜΕΝA ΓΙA ΤHΝ ΙΛAΡA ΣΤHΝ ΕΛΛAΔA.

- Vaccination Coverage for Second Dose of a Measles-Containing Vaccine, EU/EEA, 2018. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/vaccination-coverage-second-dose-measles-containing-vaccine-eueea-2018 (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Vaccination Coverage for the First Doses of Measles and Rubella Containing Vaccine by Country, EU/EEA, 2018. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/vaccination-coverage-first-doses-measles-and-rubella-containing-vaccine-country-0 (accessed on 12 April 2023).

- Georgakopoulou, T.; Menegas, D.; Katsioulis, A.; Theodoridou, M.; Kremastinou, J.; Hadjichristodoulou, C. A Cross-Sectional Vaccination Coverage Study in Preschool Children Attending Nurseries-Kindergartens: Implications on Economic Crisis Effect. Hum Vaccin Immunother 2017, 13, 190–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Andrie, E.K.; Sakellari, E.; Barbouni, A.; Tsitsika, A.K.; Lagiou, A. Vaccination Coverage during Childhood and Adolescence among Undergraduate Health Science Students in Greece. Children 2022, Vol. 9, Page 1553 2022, 9, 1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Papamichail, D.; Petraki, I.; Arkoudis, C.; Terzidis, A.; Smyrnakis, E.; Benos, A.; Panagiotopoulos, T. Low Vaccination Coverage of Greek Roma Children amid Economic Crisis: National Survey Using Stratified Cluster Sampling. The European Journal of Public Health 2017, 27, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maltezou, H.C.; Karantoni, H.; Petrikkos, P.; Georgota, P.; Katerelos, P.; Liona, A.; Tsagarakis, S.; Theodoridou, M.; Hatzigeorgiou, D. Vaccination Coverage and Immunity Levels against Vaccine-Preventable Diseases in Male Air Force Recruits in Greece. Vaccine 2020, 38, 1181–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gioula, G.; Exindari, M.; Melidou, A.; Minti, F.; Sidiropoulou, E.; Dionisopoulou, S.; Kiriazi, M.; Tsintarakis, E.; Malisiovas, N. Seroprevalence of measles in Northern Greece Acta Microbiologica Hellenica 2017 62(3):145-150. 1.

- Manganas, C.; Sophia, K.; Myria, D.; Aikaterini, P.; Maria, X. Journal of Prevention and Infection Control Seroprevalence for Measles Antibodies among Multi-Transfused Patients with Hemoglobinopathies: The Experience of a Thalassemia and Sickle Cell Department in Seroprevalence for Measles Antibodies among Multi-Transfused Pa-Tients with Hemoglobinopathies: The Experience of a Thalassemia and Sickle Cell Department in Greece. 2022,. [CrossRef]

- Nardone, A.; Miller, E. Serological Surveillance of Rubella in Europe: European Sero-Epidemiology Network (ESEN2). Euro Surveill 2004, 9, 5–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Statistics - ELSTAT. Available online: https://www.statistics.gr/en/statistics/-/publication/SPO18/- (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Copenhagen The Expanded Programme on Immunization in the European Region of WHO Measles A Strategic Framework for the Elimination of Measles in the European Region.

- Ask the Experts: Measles, Mumps, and Rubella (MMR) Vaccines. Available online: https://www.immunize.org/askexperts/experts_mmr.asp (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Measles in the EU/EEA: Current Outbreaks, Latest Data and Trends – January 2018. Available online: https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/news-events/measles-eueea-current-outbreaks-latest-data-and-trends-january-2018 (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Georgakopoulou, T.; Horefti, E.; Vernardaki, A.; Pogka, V.; Gkolfinopoulou, K.; Triantafyllou, E.; Tsiodras, S.; Theodoridou, M.; Mentis, A.; Panagiotopoulos, T. Ongoing Measles Outbreak in Greece Related to the Recent European-Wide Epidemic. Epidemiol Infect 2018, 146, 1692–1698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nearly 40 Million Children Are Dangerously Susceptible to Growing Measles Threat. Available online: https://www.who.int/news/item/23-11-2022-nearly-40-million-children-are-dangerously-susceptible-to-growing-measles-threat (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- MMR Vaccines and Autism. Available online: https://www.who.int/groups/global-advisory-committee-on-vaccine-safety/topics/mmr-vaccines-and-autism (accessed on 13 April 2023).

- Tafuri, S.; Bianchi, F.P.; Stefanizzi, P.; De Nitto, S.; Maria, A.; Larocca, V.; Germinario, C.; Tafuri, S. The Journal of Infectious Diseases Long-Term Immunogenicity of Measles Vaccine: An Italian Retrospective Cohort Study. The Journal of Infectious Diseases ® 2020, 221, 721–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poethko-Müller, C.; Mankertz, A. Sero-Epidemiology of Measles-Specific IgG Antibodies and Predictive Factors for Low or Missing Titres in a German Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study in Children and Adolescents (KiGGS). Vaccine 2011, 29, 7949–7959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tasika, E.; Farmaki, E.; Roilides, E.; Antachopoulos, C. Implementation of the Greek National Immunization Program among Nursery Attendees in the Urban Area of Thessaloniki. Hippokratia 2019, 23, 147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Anichini, G.; Gandolfo, C.; Fabrizi, S.; Miceli, G.B.; Terrosi, C.; Savellini, G.G.; Prathyumnan, S.; Orsi, D.; Battista, G.; Cusi, M.G. Seroprevalence to Measles Virus after Vaccination or Natural Infection in an Adult Population, in Italy. Vaccines 2020, Vol. 8, Page 66 2020, 8, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bianchi, F.P.; Mascipinto, S.; Stefanizzi, P.; De Nitto, S.; Germinario, C.; Tafuri, S. Long-Term Immunogenicity after Measles Vaccine vs. Wild Infection: An Italian Retrospective Cohort Study. https://doi.org/10.1080/21645515.2020.1871296 2021, 17, 2078–2084. [CrossRef]

- Ristić, M.; Milošević, V.; Medić, S.; Malbaša, J.D.; Rajčević, S.; Boban, J.; Petrović, V. Sero-Epidemiological Study in Prediction of the Risk Groups for Measles Outbreaks in Vojvodina, Serbia. PLoS One 2019, 14, e0216219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smetana, J.; Chlibek, R.; Hanovcova, I.; Sosovickova, R.; Smetanova, L.; Gal, P.; Dite, P. Decreasing Seroprevalence of Measles Antibodies after Vaccination – Possible Gap in Measles Protection in Adults in the Czech Republic. PLoS One 2017, 12, 170257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ruggieri, A.; Anticoli, S.; D’ambrosio, A.; Giordani, L.; Viora, M. Monographic Section The Influence of Sex and Gender on Immunity, Infection and Vaccination. Ann Ist Super Sanità 2016, 52, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mikhail Kostinov, P.; Pavel Zhuravlev, I.; Nikolay Filatov, N.; Aristitsa Kostinova, M.; Valentina Polishchuk, B.; Anna Shmitko, D.; Cyrill Mashilov, V.; Anna Vlasenko, E.; Alexey Ryzhov, A.; Anton Kostinov, M. Gender Differences in the Level of Antibodies to Measles Virus in Adults. Vaccines (Basel) 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenth Meeting of the European Regional Verification Commission for Measles and Rubella Elimination; 2022.

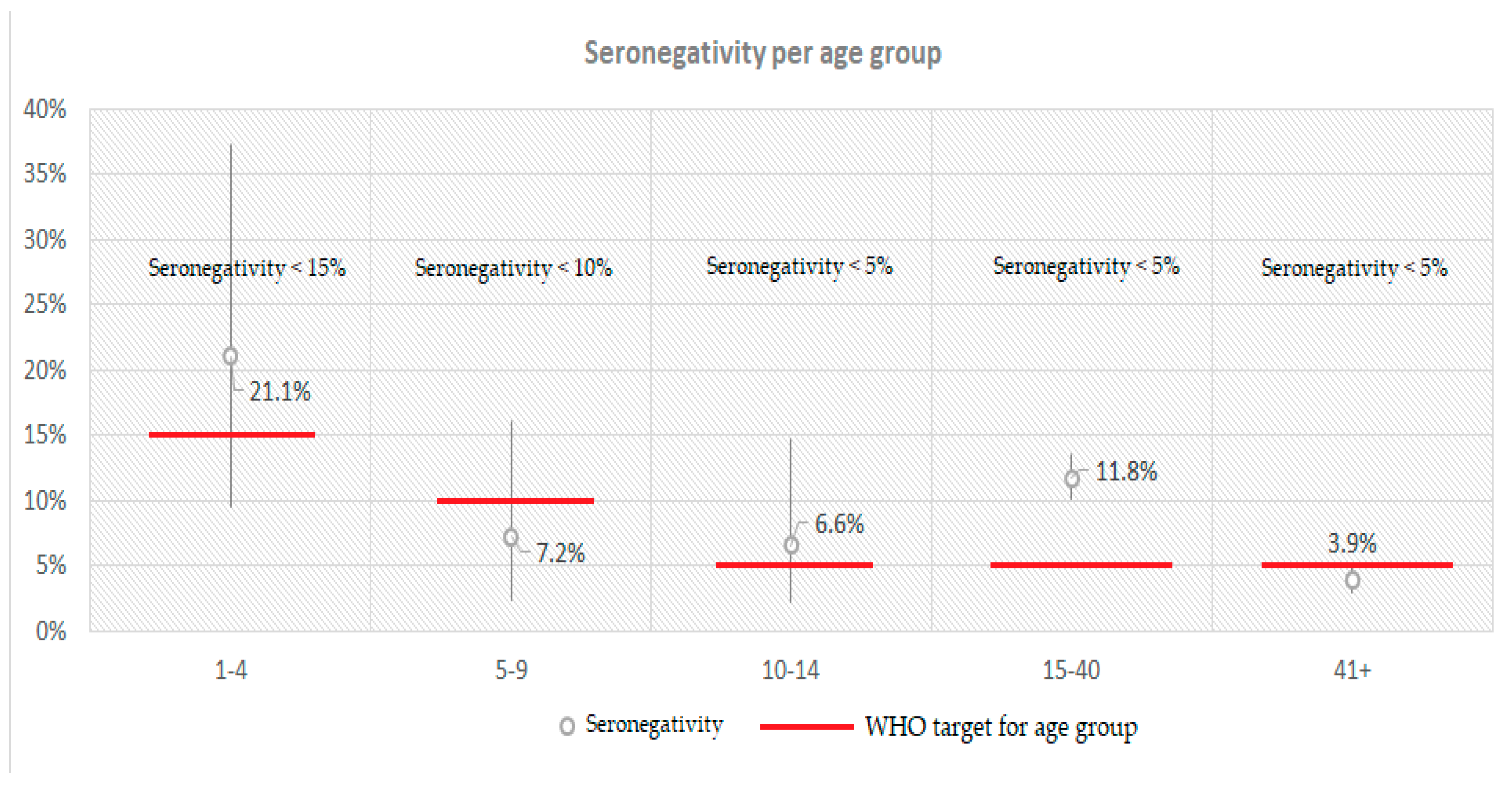

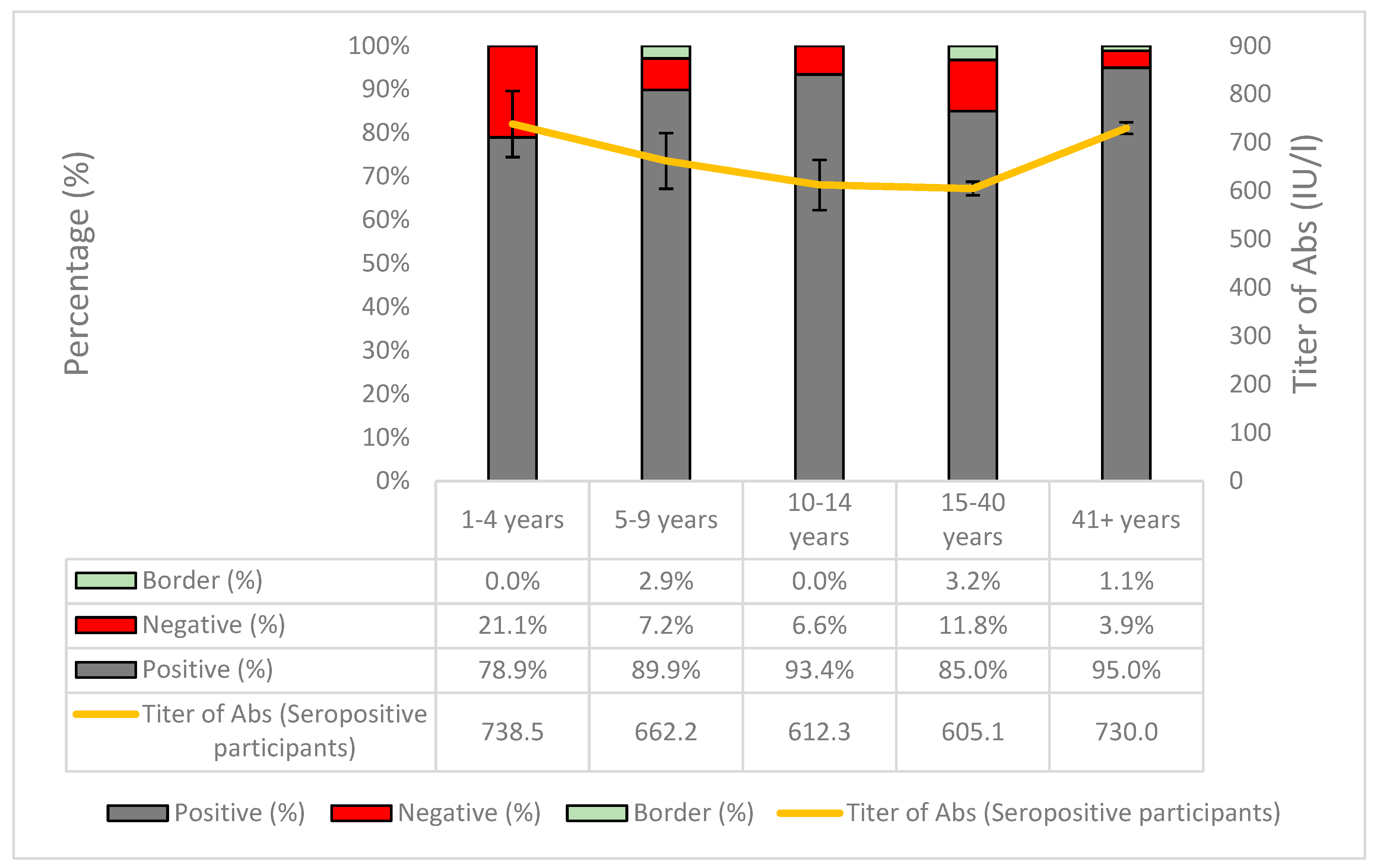

| Positive (N) | Negative (N) | Boarder (N) | Total | Crude Seroprevalence | Adjusted Seroprevalence* | 95% CI | Sig.** | Antibody Titer of Seropositive Participants | 95% CI | Sig. | ||||

| Overall | 3558 | 327 | 87 | 3972 | 89.6% | 89.8% | 88.8% | 90.8% | - | 672.9 | 662.7 | 683.1 | - | |

| Sex | Male | 1382 | 132 | 27 | 1541 | 89.7% | 89.2% | 87.6% | 90.8% | 0.783C | 692.9 | 674.0 | 711.8 | 0.003M-W |

| Female | 1974 | 180 | 54 | 2208 | 89.4% | 89.8% | 88.5% | 91.1% | 656.9 | 645.9 | 667.9 | |||

| Age groups | 1-24 | 810 | 110 | 35 | 955 | 84.8% | 84.4% | 81.9% | 86.8% | <0.001C | 640.5 | 609.4 | 671.6 | <0.001K-W |

| 25-54 | 1420 | 160 | 39 | 1619 | 87.7% | 87.6% | 85.9% | 89.3% | 632.1 | 619.0 | 645.3 | |||

| 55-64 | 555 | 25 | 4 | 584 | 95.0% | 95.6% | 93.7% | 97.4% | 744.2 | 723.7 | 764.6 | |||

| 65-79 | 486 | 17 | 6 | 509 | 95.5% | 94.9% | 93.0% | 96.7% | 749.6 | 730.2 | 769.0 | |||

| 80+ | 168 | 6 | 2 | 176 | 95.5% | 95.4% | 92.3% | 98.6% | 722.4 | 687.3 | 757.4 | |||

| Age groups | 1-40 | 1149 | 165 | 54 | 1368 | 84.0% | 83.4% | 81.6% | 85.7% | <0.001C | 616.5 | 593.4 | 639.6 | <0.001M-W |

| ≥41 | 1513 | 62 | 18 | 1593 | 95.0% | 94.9% | 93.7% | 95.9% | 730.0 | 718.0 | 742.1 | |||

| Large urban areas (>500,000) | 1532 | 152 | 27 | 1711 | 89.5% | 90.3% | 84.4% | 94.1% | 0.991C | 681.3 | 663.7 | 698.8 | 0.163-W | |

| Rest of country | 1949 | 170 | 58 | 2177 | 89.5% | 89.0% | 84.4% | 92.1% | 665.6 | 653.4 | 677.8 | |||

| Islands | 487 | 39 | 11 | 537 | 90.7% | 90.7% | 80.5% | 95.4% | 0.523C | 665.2 | 642.7 | 687.7 | 0.899-W | |

| Mainland | 2994 | 283 | 74 | 3351 | 89.3% | 89.2% | 85.3% | 92.4% | 673.7 | 662.2 | 685.2 | |||

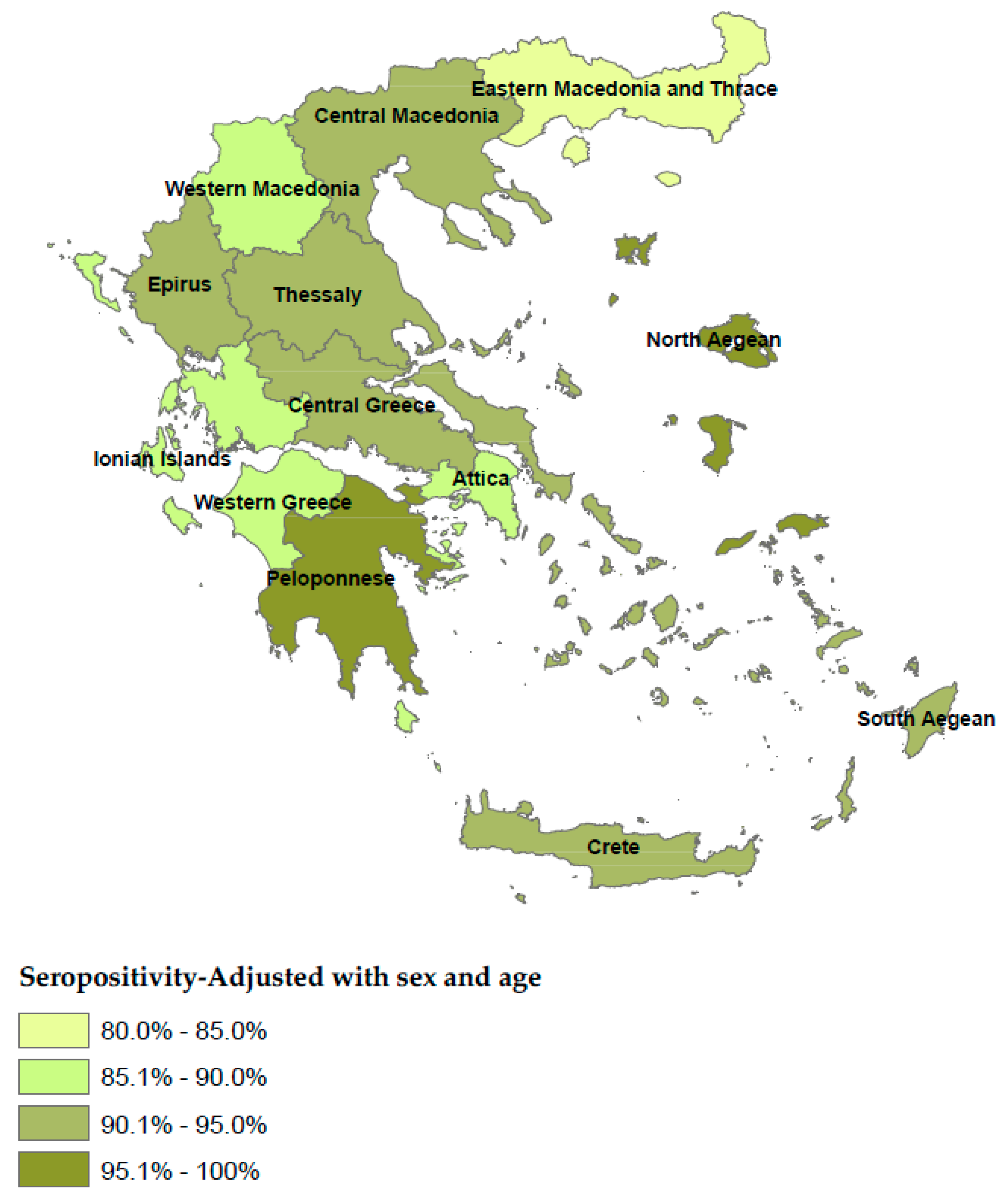

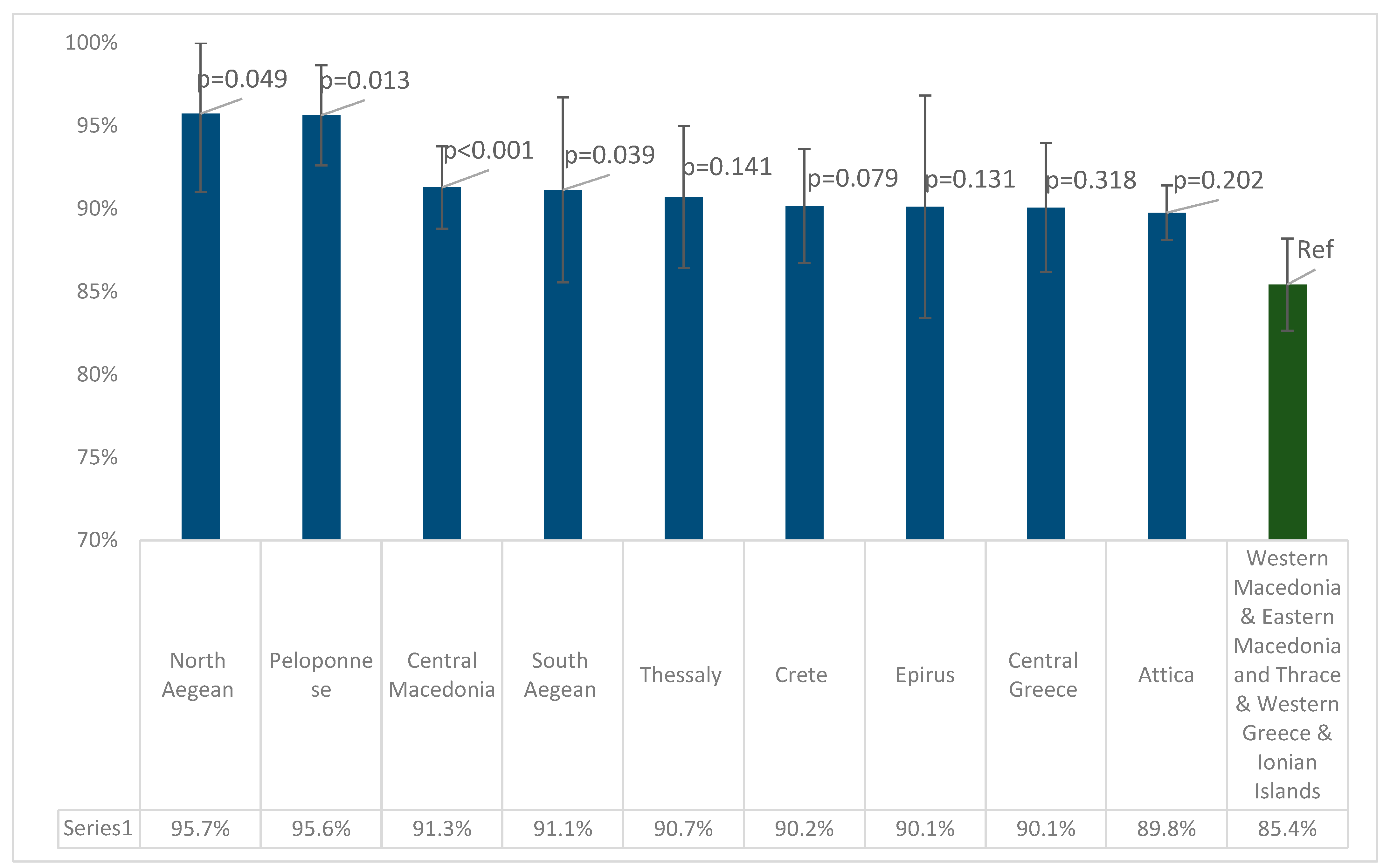

| Region (NUTS Level 2) | Positive (N) | Negative (N) | Boarder (N) | Total | Crude Seroprevalence | Adjusted Seroprevalence | 95% CI | Sig.** | Antibody Titer of Seropositive Participants | 95% CI | Sig. | ||

| Attica | 1188 | 132 | 10 | 1330 | 89.3% | 89.8%* | 88.1% | 91.4% | <0.001C | 672.8 | 651.5 | 694.0 | <0.001K-W |

| Central Greece | 204 | 19 | 4 | 227 | 89.9% | 90.1% | 86.2% | 93.6% | 693.1 | 658.5 | 727.7 | ||

| Thessaly | 231 | 19 | 6 | 256 | 90.2% | 90.7%* | 86.4% | 95.0% | 642.9 | 608.4 | 677.4 | ||

| Western Greece | 200 | 22 | 12 | 234 | 85.5% | 85.9%* | 81.4% | 90.4% | 636.9 | 605.3 | 668.5 | ||

| Epirus | 97 | 4 | 5 | 106 | 91.5% | 90.5%* | 83.9% | 97.0% | 692.5 | 570.0 | 814.9 | ||

| Crete | 261 | 23 | 5 | 289 | 90.3% | 90.2% | 86.7% | 93.6% | 641.5 | 611.4 | 671.6 | ||

| Central Macedonia | 586 | 38 | 24 | 648 | 90.4% | 91.3%* | 88.8% | 93.8% | 705.1 | 685.2 | 725.1 | ||

| Ionian Islands | 64 | 10 | 2 | 76 | 84.2% | 85.8% | 78.0% | 93.6% | 686.1 | 627.3 | 745.0 | ||

| North Aegean | 68 | 3 | 1 | 72 | 94.4% | 95.7%* | 91.0% | 100% | 645.7 | 584.9 | 706.5 | ||

| South Aegean | 94 | 3 | 3 | 100 | 94.0% | 91.1% | 85.6% | 96.7% | 730.9 | 676.9 | 784.8 | ||

| Peloponnese | 220 | 9 | 0 | 229 | 96.1% | 95.6%* | 92.6% | 98.7% | 695.3 | 661.2 | 729.4 | ||

| Western Macedonia | 80 | 14 | 3 | 97 | 82.5% | 85.2% | 78.1% | 92.3% | 652.5 | 602.8 | 702.2 | ||

| Eastern Macedonia and Thrace | 189 | 27 | 10 | 226 | 83.6% | 84.6%* | 79.9% | 89.4% | 610.7 | 576.1 | 645.3 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).