1. Introduction

The possibility of actual or past life on Mars is an open subject due to the planet’s proximity and similarities to Earth. For this reason, Mars is the most visited planet to search for extraterrestrial life. Unfortunately, the landing on Mars’ surface is a very complicated and risky mission. For example, the last attempt of European Space Agency (ESA) to send the Schiaparelli lander on Mars’ surface was a complete failure because it crashed on the planet’s surface.

The National Institute for Aerospace Research (INCAS) “Elie Carafoli” has studied the reentry of capsules and meteors on Earth’s atmosphere in projects founded by ESA and Romanian Research Ministry using in-house codes and Ansys Fluent [

1,

2,

3].

There are some available papers, which deal with hypersonic aerodynamics of Mars entry vehicles but they have especially used in-house CFD codes [

4,

5,

6,

7], which are available to a small number of researchers. For this reason, the present paper focuses to find an affordable numerical approach using Ansys Fluent [

8], which is a very popular and appreciate CFD code by both academic and industrial communities.

2. Governing Equations

Because CO

2 is the dominant species of Martian atmosphere and its relaxation time is very short compared with the characteristic time of flow field, the level of thermal nonequilibrium in the flow field is minor [

7]. Therefore, in the current study, one temperature model is employed and the vibrational-electronic energy conservation is not presented [

7].

The classic governing equations for axisymmetric reacting laminar hypersonic gas dynamics in thermal equilibrium are [

2,

8]:

where

Y

i is the mass fraction of species

I,

where ω

I is the rate of formation/destruction of species I, N signifies the number of chemical species,

where W

i represents the molecular weight of species I,

In this paper, the authors have used the NASA-piecewise-polynomial to compute the specific heats of chemical species at constant pressure [

9]:

where the coefficients A

i are constant over a range of temperature.

In the hypersonic flows, there are huge variations of temperature. Unfortunately, there are very few available experimental data at very high temperatures for viscosity and thermal conductivity of gases. For this reason, one prefers the kinetic theory of gases to compute their viscosity and thermal conductivity at very high temperatures [

10,

11].

The flow is assumed laminar; therefore, the speed of chemical reactions is governed by the modified Arrhenius equation [

12]:

where j is the number of chemical reactions,

where Γ

j is the third body efficiency, X

i is the volume (molar) fraction of species I, W represents the molecular weight of gas mixture, k

fj signifies the rate of forward chemical reaction j and Ea

j is the activation energy of reaction j.

For entry velocities below 8 km/s, the level of ionization will be small [

6]. As the Martian atmosphere is a mixture of 95.7% CO

2, 2.7% N

2 by volume and some other gases [

5], it is possible to assume it contains only CO

2, in a first approximation. Therefore, the Mars 5-species McKenzie model [

13] described in

Table 1 is suitable for the purpose of this paper.

It Is worth to mention that In the hypersonic gas dynamics, one prefers to use the kinetic theory of gases as much as possible. For this reason, the rate exponents n’

ij are the stoichiometric coefficients of reactants ν’

ij (see

Table 1) while for the common applications (for example for the burning of hydrocarbons), the rate exponents are determined experimentally [

3].

3. Numerical Simulations

The Mars Pathfinder entry vehicle was launched in 1996 and entered the atmosphere of Mars in the following year [

14]. This vehicle whose geometry is given in [

14] is used as a test case in this paper. At altitude of 41.204 km, the maximum stagnation heat convective flux occurs. For this reason, the paper focuses to study the flow at this altitude.

The freestream conditions for the Pathfinder vehicle at this altitude are given in

Table 2.

The flow is supersonic; therefore, on inlet boundary, all conservative variables are imposed while on outlet boundary, these variables are extrapolated. On Pathfinder wall, one imposes isothermal surface of 1693 K, which is the temperature on Pathfinder surface at stagnation point [

12], the non-slip condition for velocity (V

w = 0), and zero wall normal gradients of pressure (∂p

w/∂n = 0) and species (∂Y

iw/∂n = 0, non-catalytic wall).

Three multiblock structured meshes clustered near Pathfinder’s wall were generated using the commercial meshing tool Beta CAE ANSA 25 [

15] to study the grid sensitivity as shown in

Table 3. The drag coefficient is the most important coefficient to study the entry of Mars vehicles. The

Table 3 clearly shows that the values of this parameter obtained with medium and fine grids are extremely close.

The convective flux (see Equation 3) was discretized by AUSM

+-p scheme [

16,

17,

18], which was developed continuously by Liou over a period of about 15 years and it is suitable for hypersonic regime [

3].

4. Numerical Results and Discussions

As it follows, the given numerical results are obtained with fine grid.

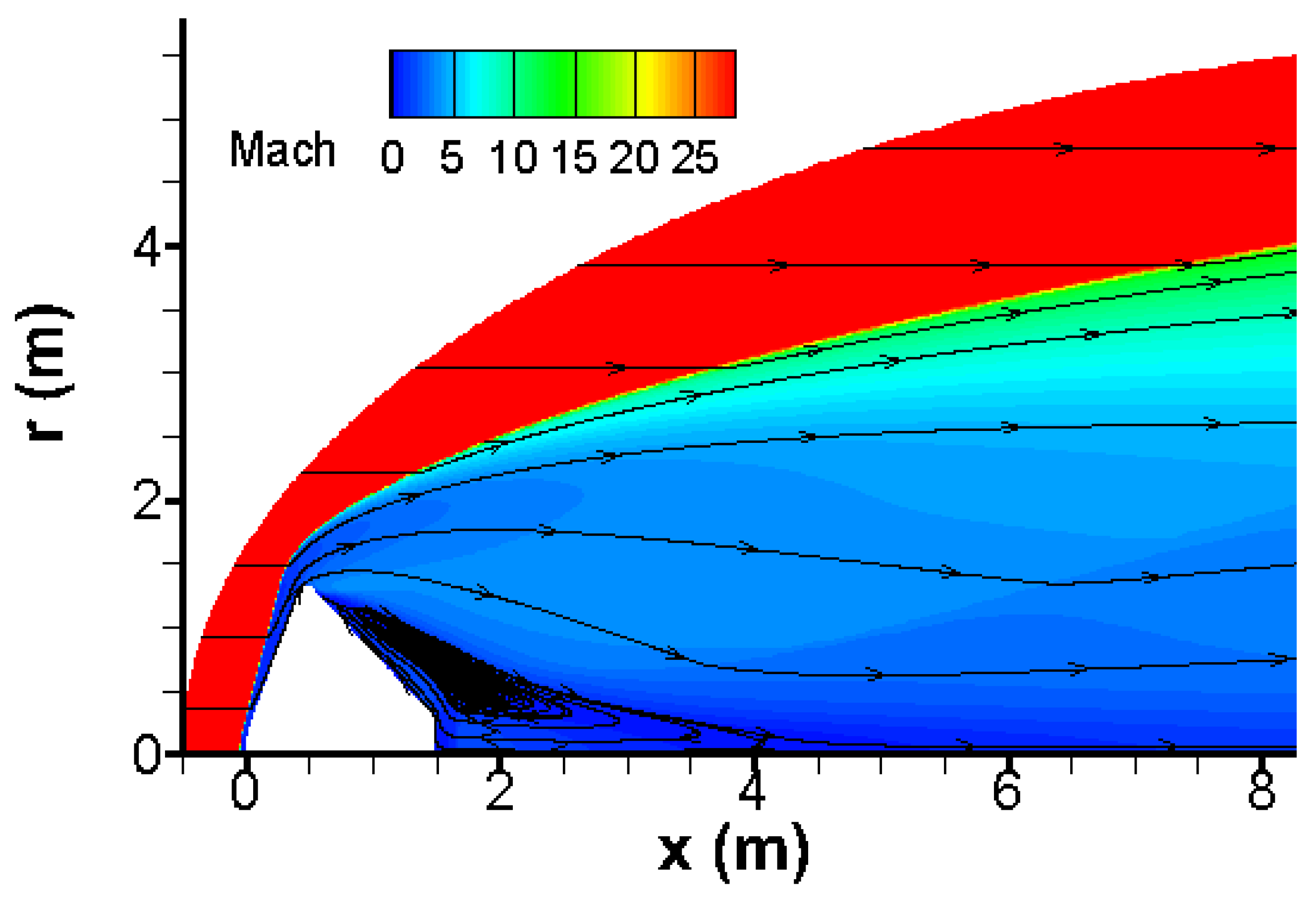

The velocity field over Pathfinder vehicle is shown in

Figure 1. One clearly observes the very strong bow shock in front of vehicle, the recirculation region and neck behind Pathfinder. Furthermore, this velocity distribution is very close to that given in [

14], which was obtained with a two-temperature model and an 8-species finite rate chemical reaction model proposed by Micheltree and Gnoffo [

19]. This model is reduced from the 18-species reaction model of Park et al. [

20], neglecting ionization reactions.

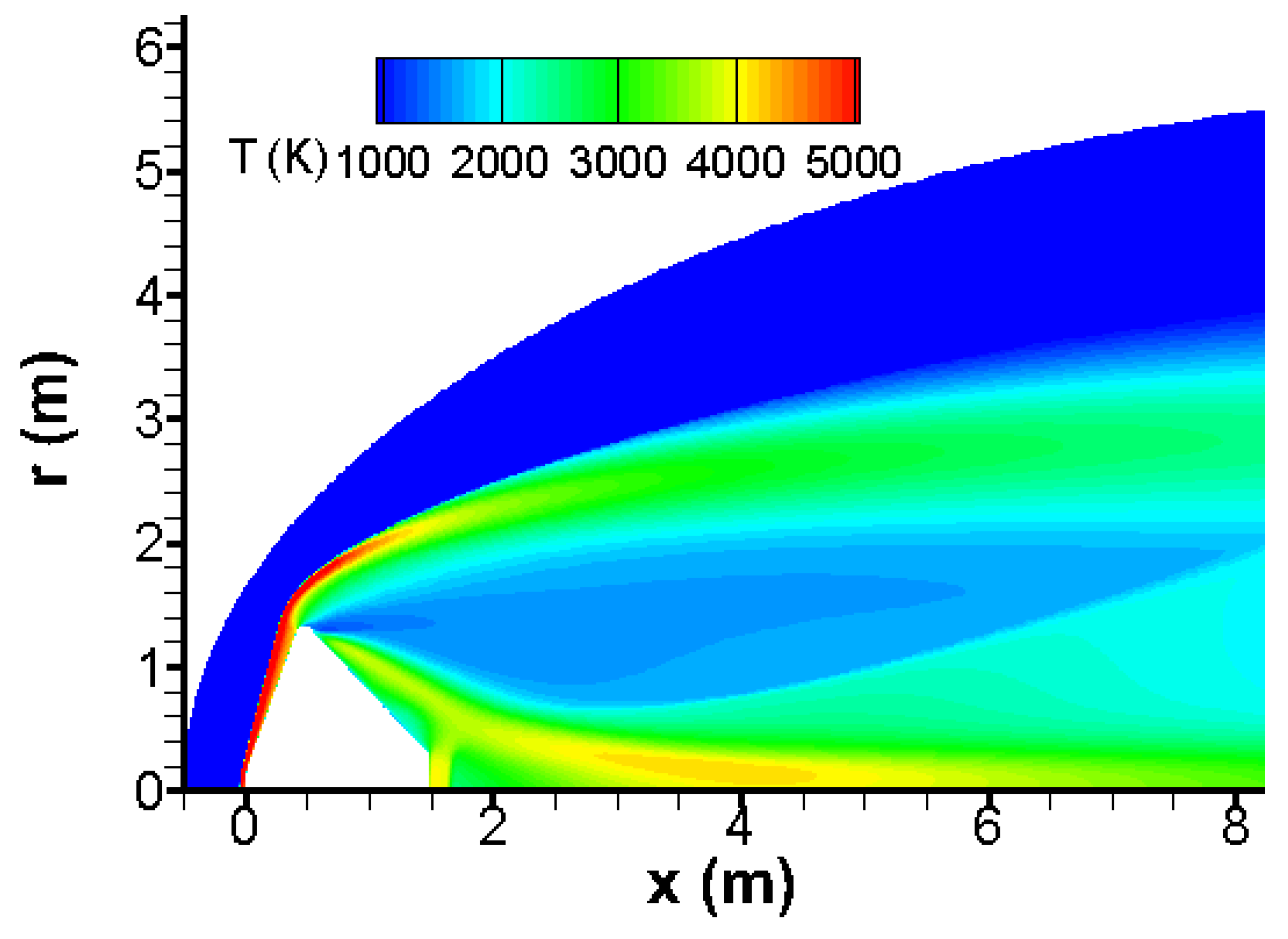

The temperature increases dramatically behind the bow wave and the conical shock waves as given in

Figure 2. Moreover, the temperature field shows rarefaction and shock waves behind the Pathfinder vehicle. Remarkably, the temperature distribution of

Figure 2 is in good agreement to that given in [

14].

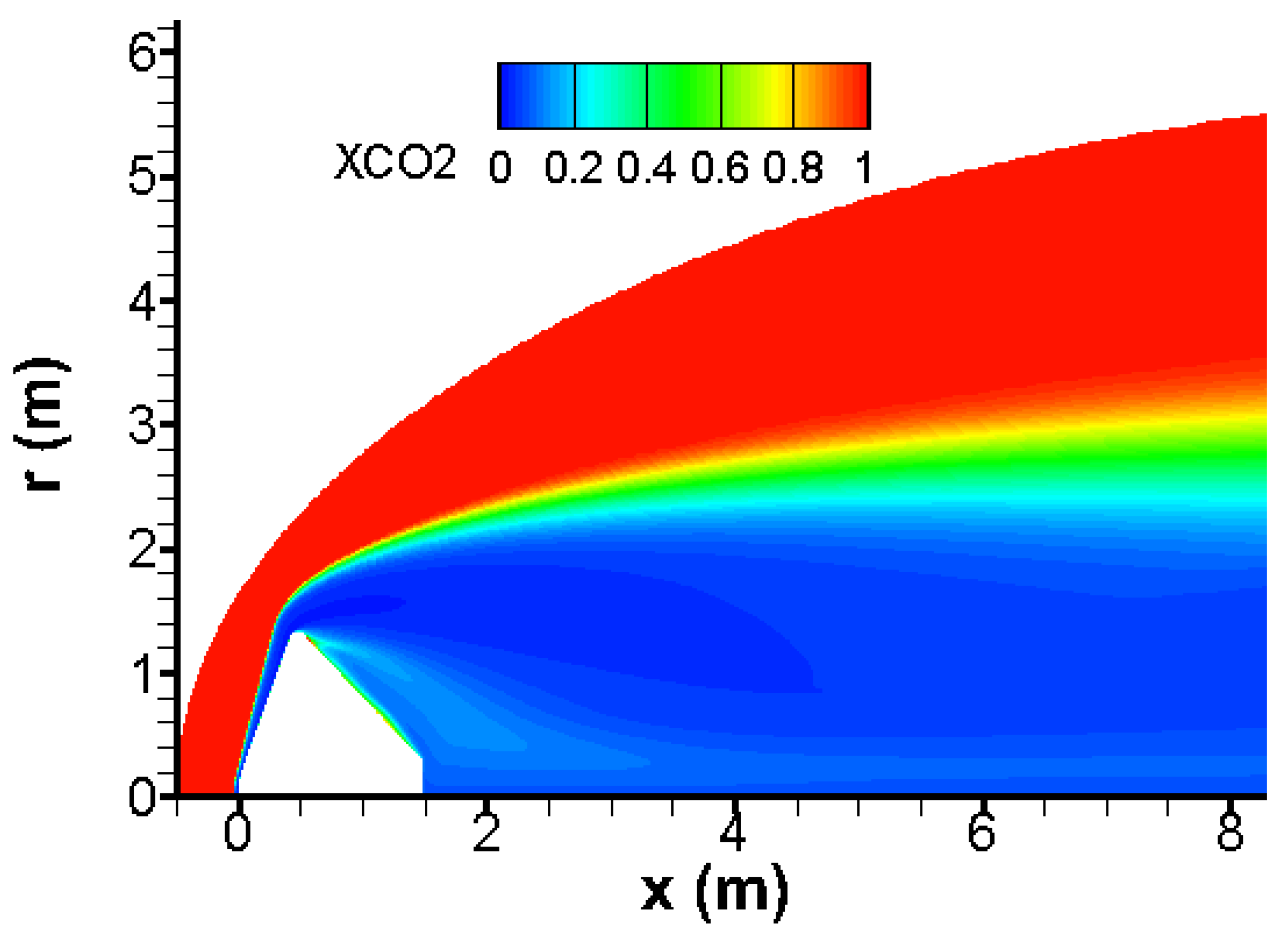

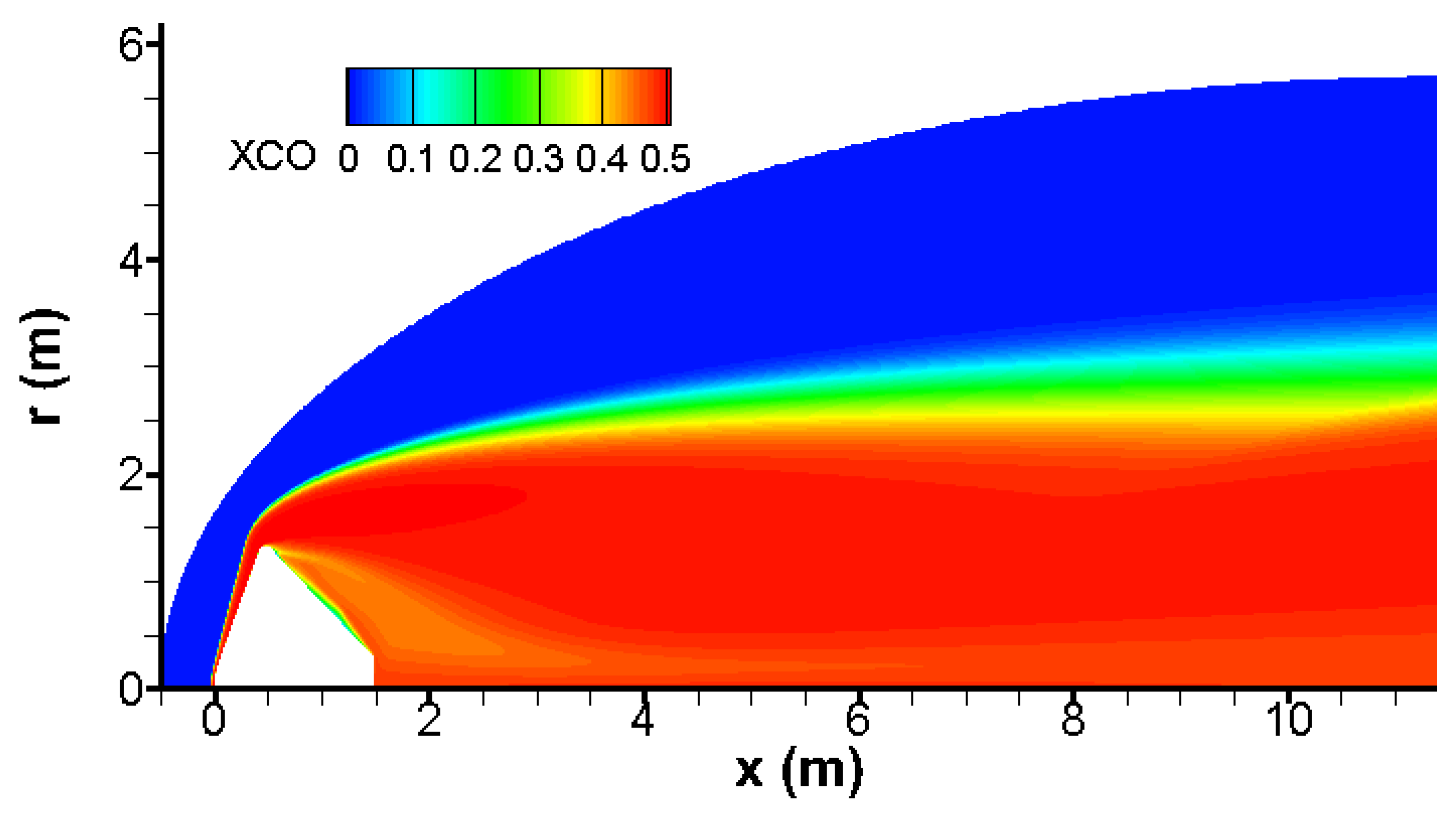

Almost all CO

2 is broken behind the bow wave as shown in

Figure 3. Again, there is a good agreement with results published in [

4,

21].

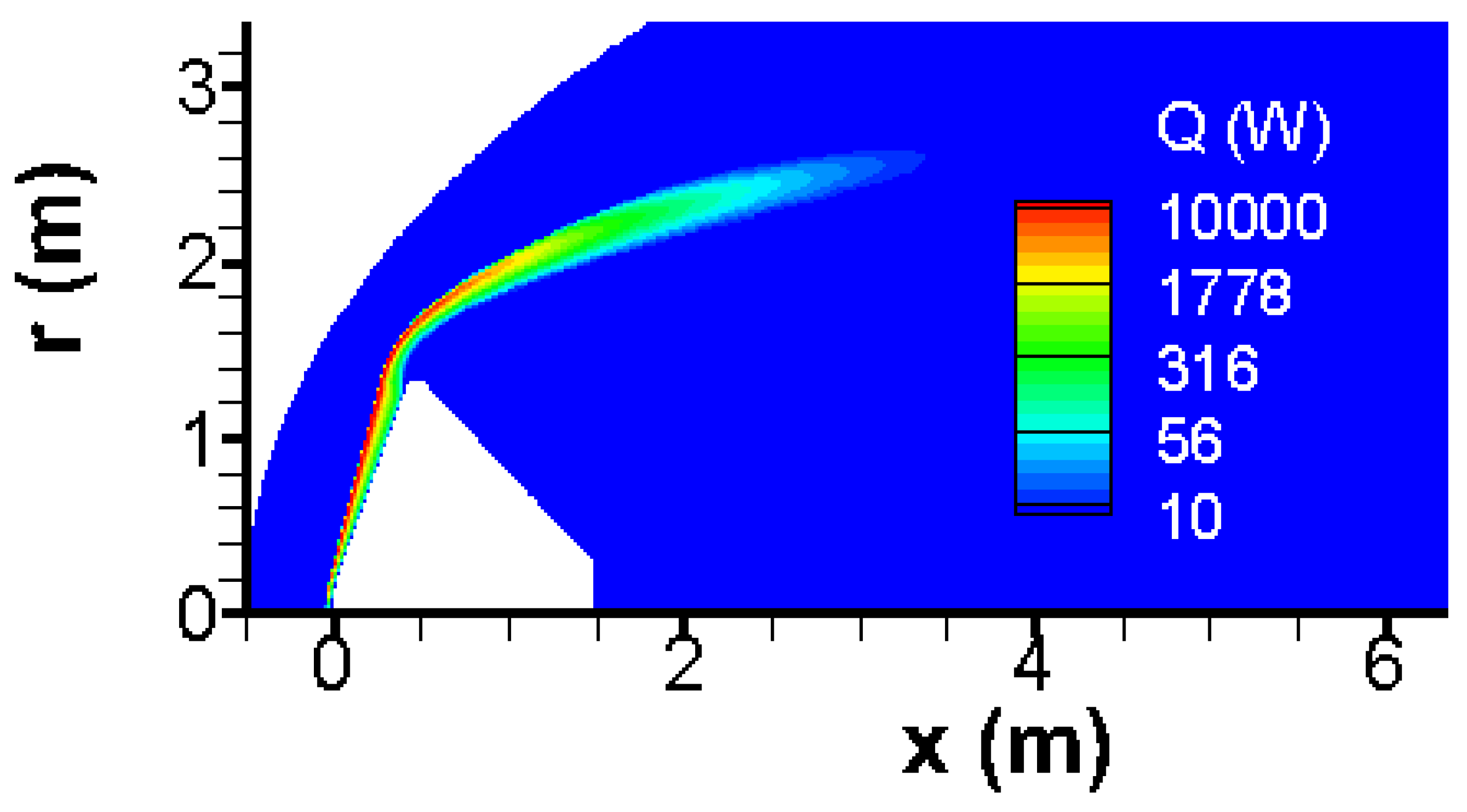

All chemical reactions of

Table 1 are endothermal as shown in

Figure 4; therefore, the task of thermal shield is alleviated impressively. One observes that the endothermal chemical reactions are concentrated in a narrow band behind the bow shock.

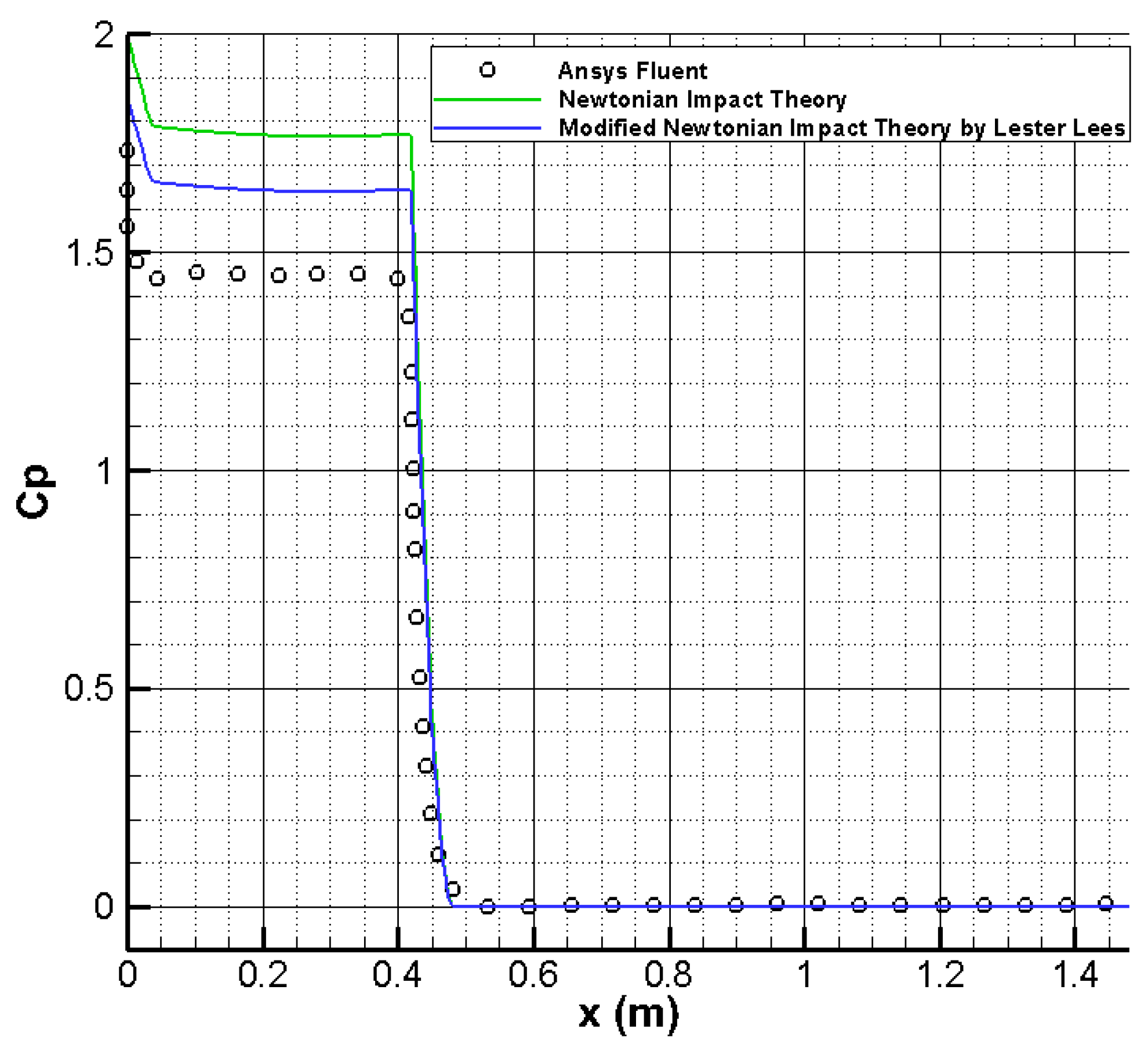

Pressure distribution on Pathfinder’s wall is given in

Figure 5. One observes a good concordance among the pressure distribution on Pathfinder’s wall computed with Ansys Fluent and those predicted by Newtonian impact theory and modified Newtonian impact theory by Lester Lees [

22,

23]:

where θ is the impact angle and

where γ is the specific heat ratio of gas mixture.

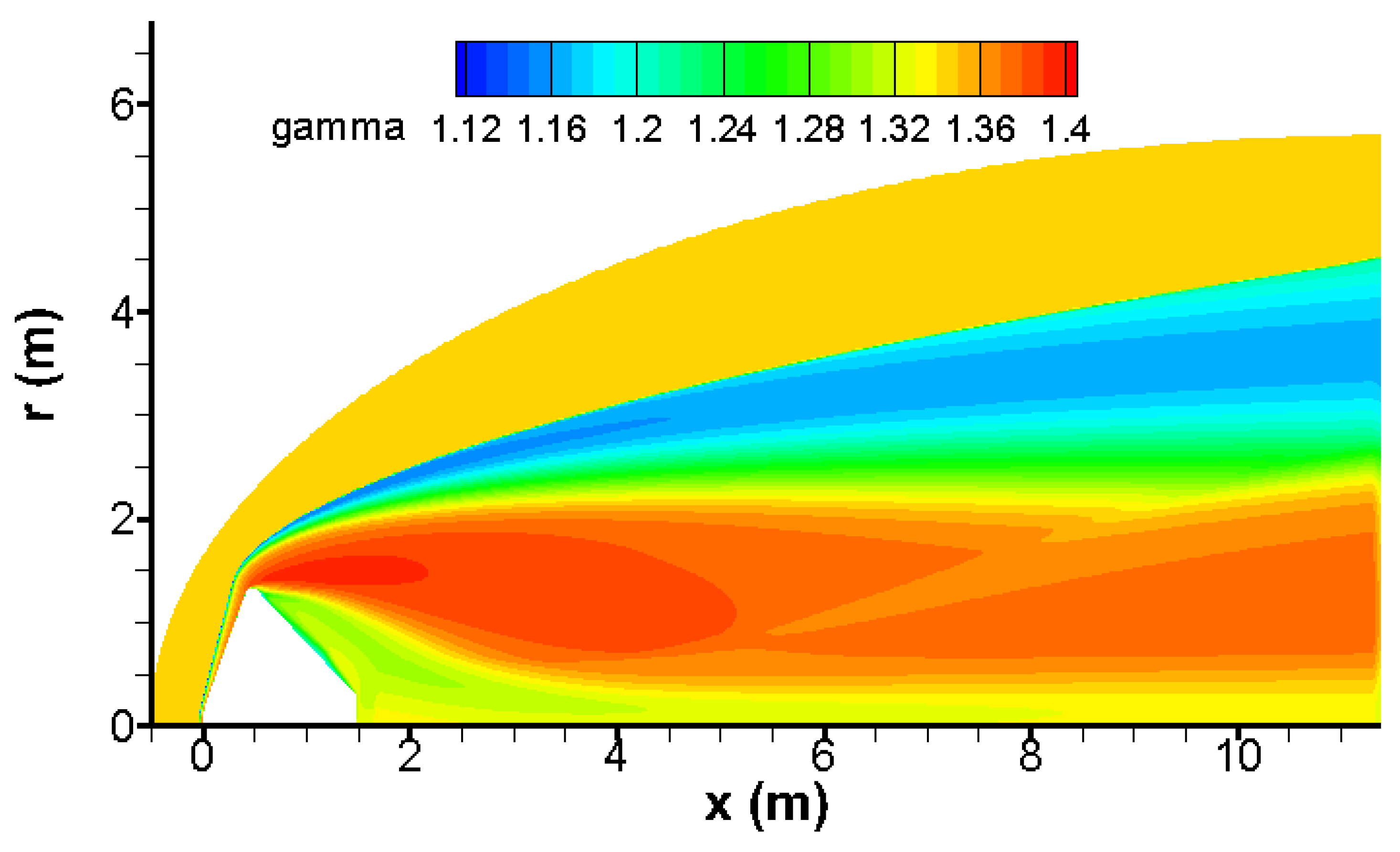

The contour of specific heat ratio of gas mixture γ is given in

Figure 6 and clearly shows that the variation of this parameter must be considered.

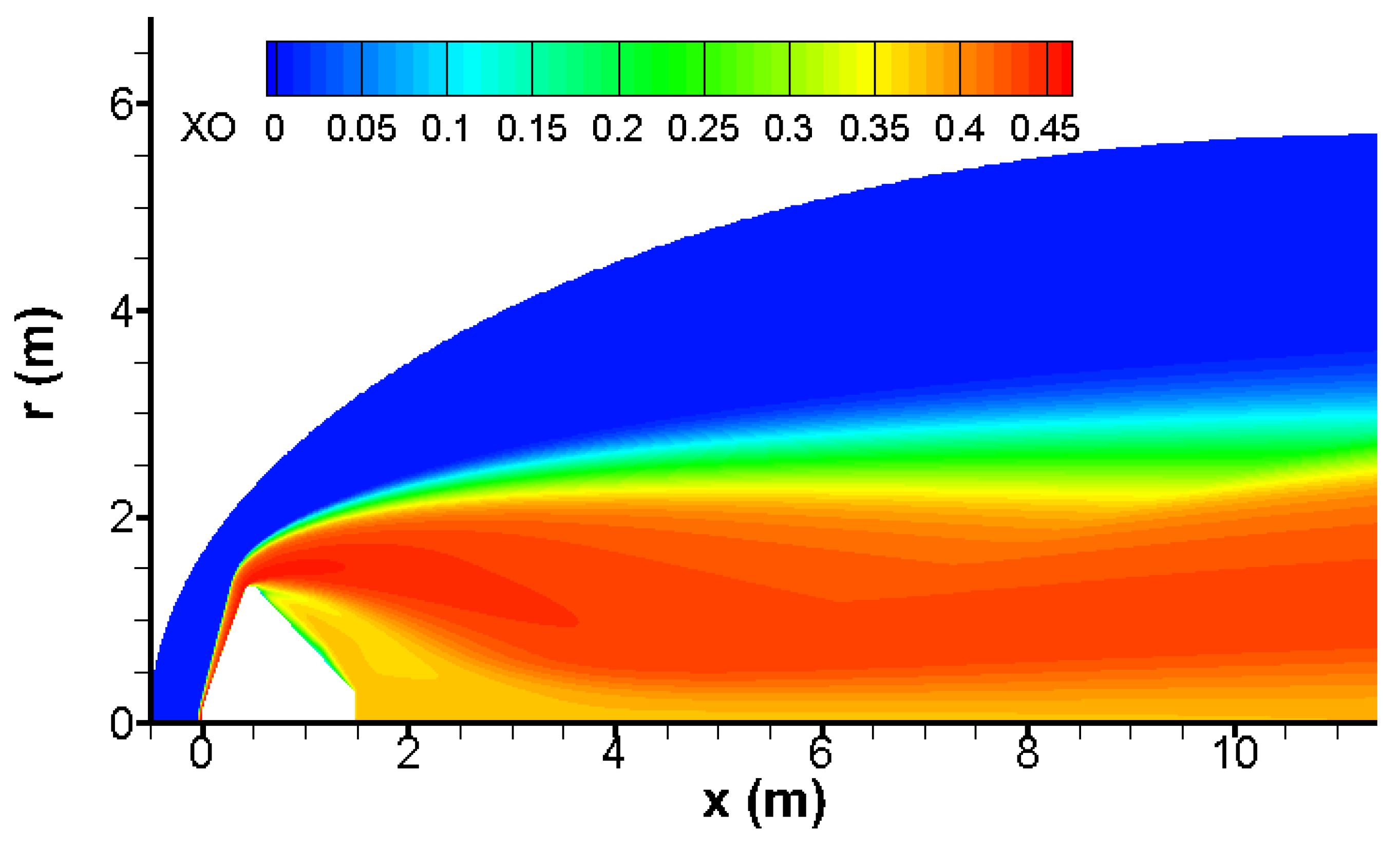

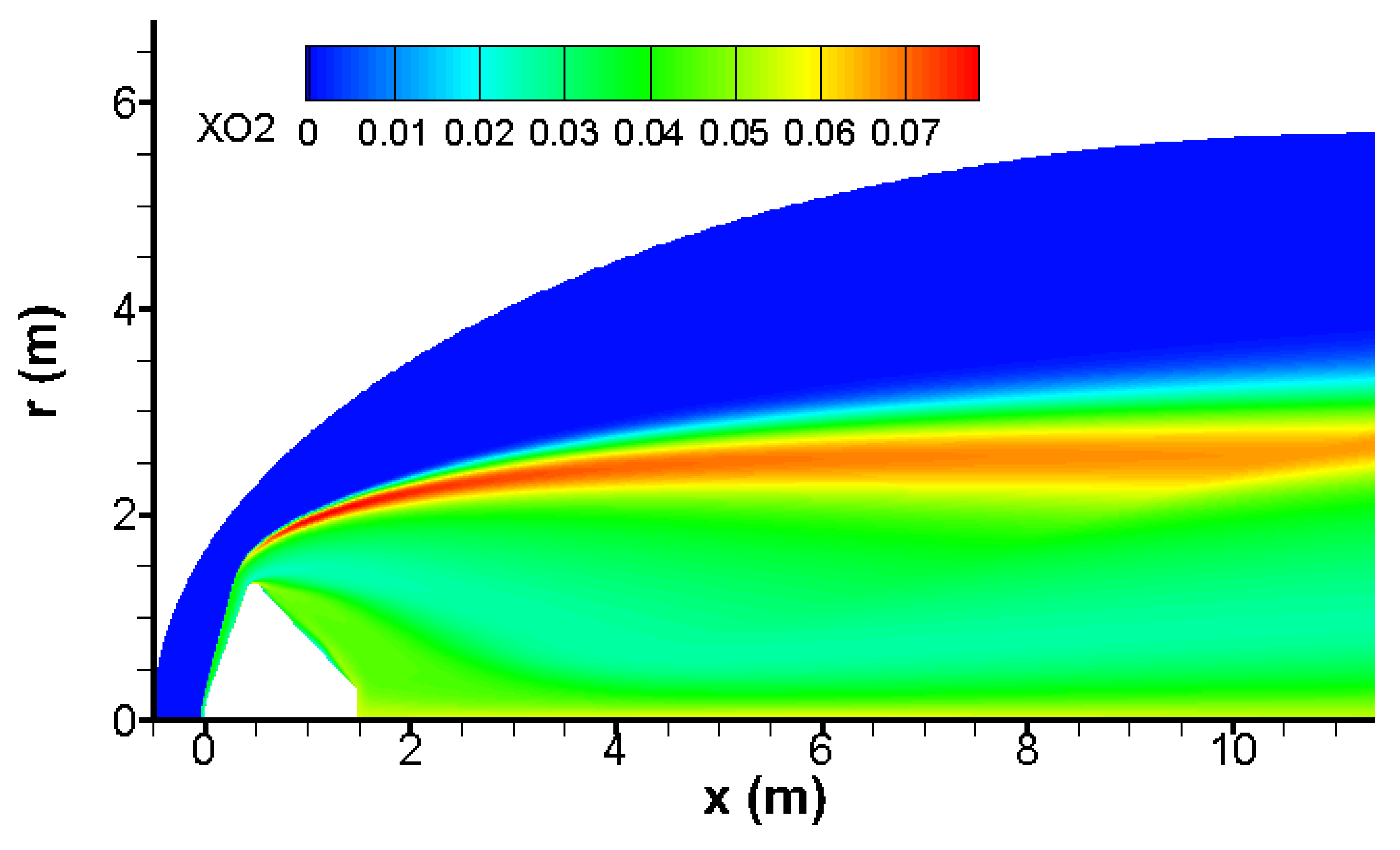

The bow wave induces an impressive temperature rise, which triggers strong endothermal chemical reactions given in

Table 1. The outcome of these chemical reactions is a dramatic temperature decrease and a massive production of atomic and molecular oxygen as shown in

Figure 7 and

Figure 8.

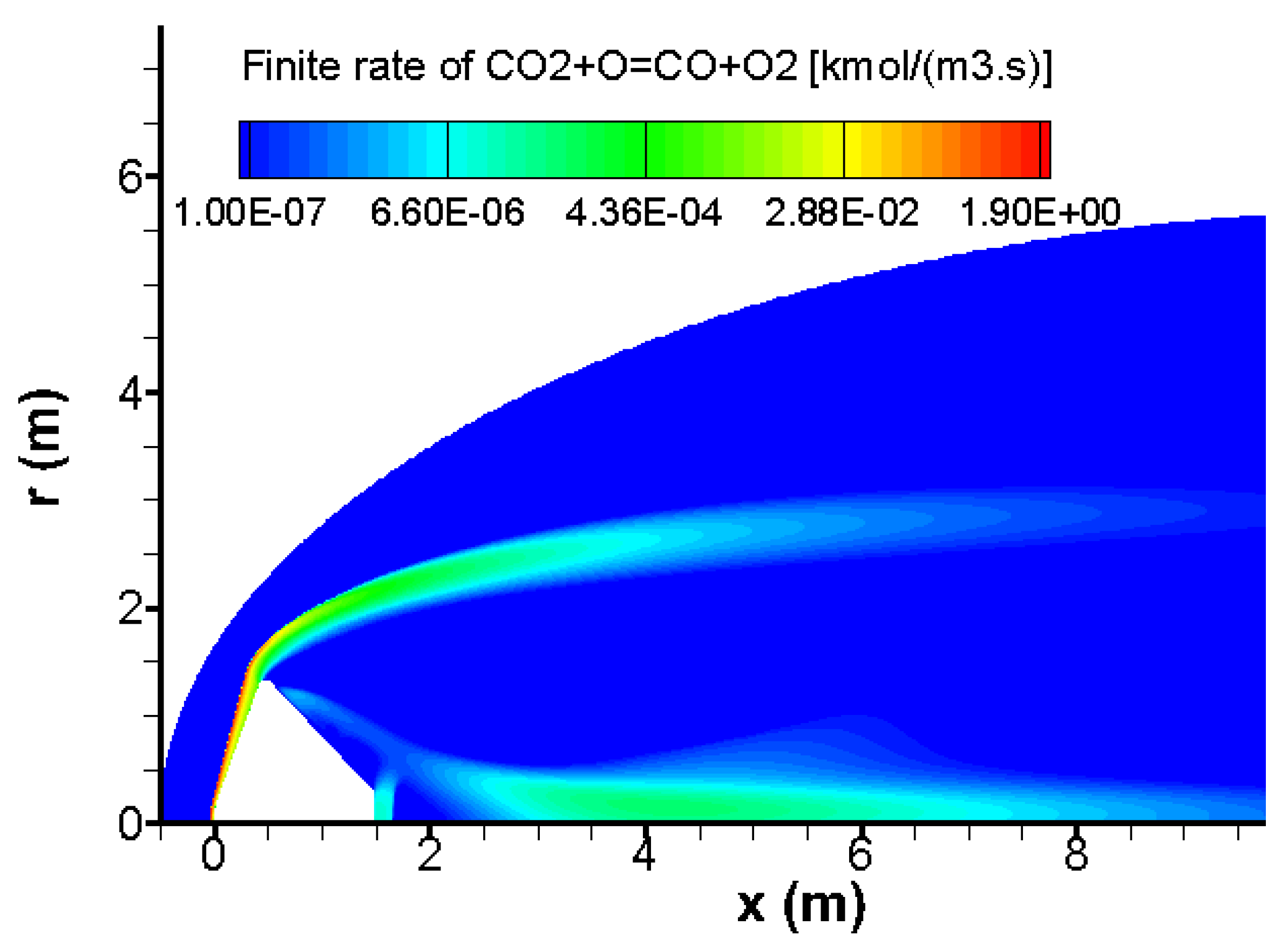

Behind the bow wave, almost half of carbon dioxide CO

2 is converted into carbon monoxide CO due to the chemical reactions CO

2 → CO + O and CO

2 + O → CO + O

2. This conversion and the kinetic rate of reaction CO

2 + O → CO + O

2 are given in

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 respectively. Practically, this reaction takes place in hot regions due to the bow wave and the conical shock waves.

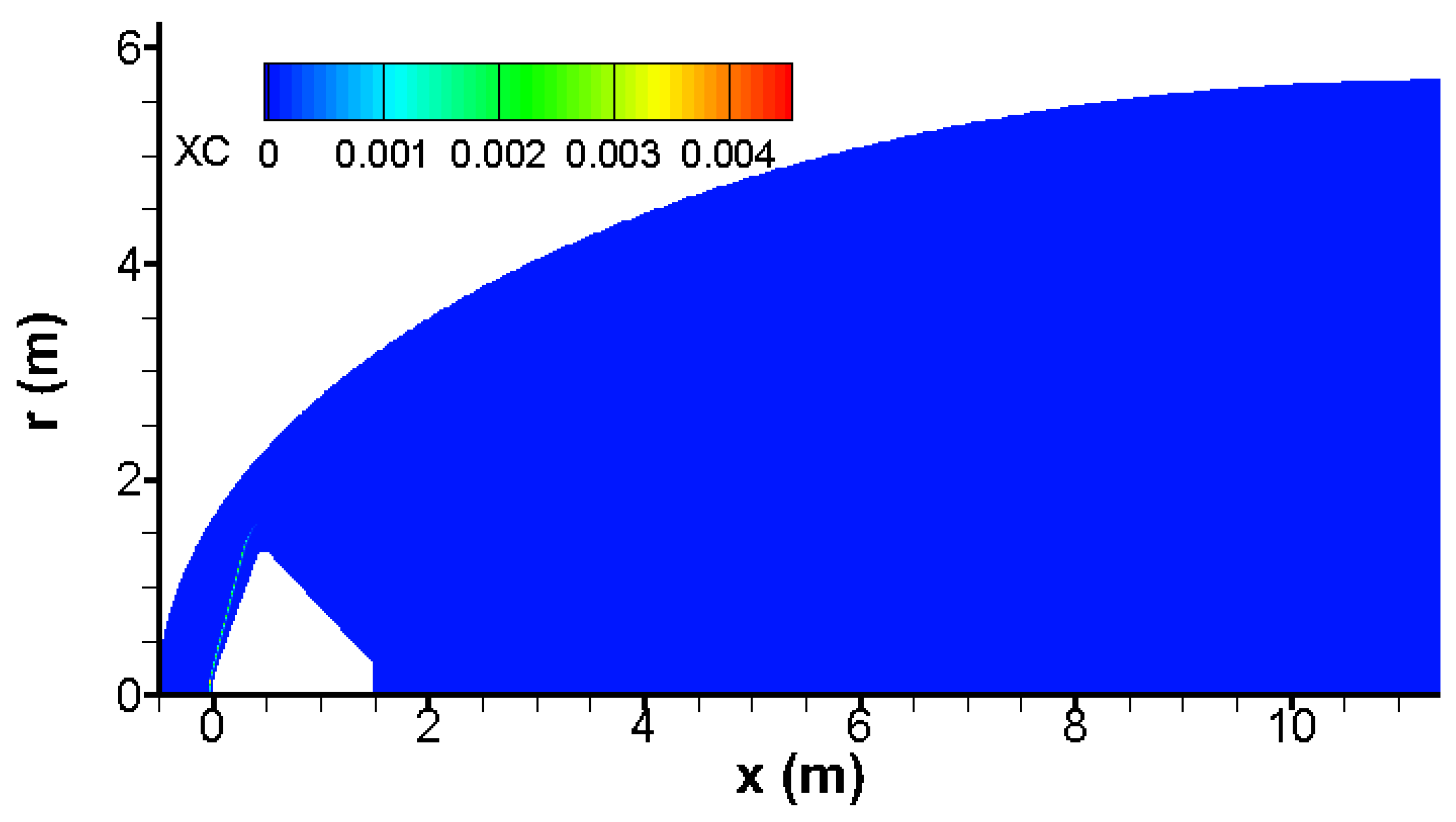

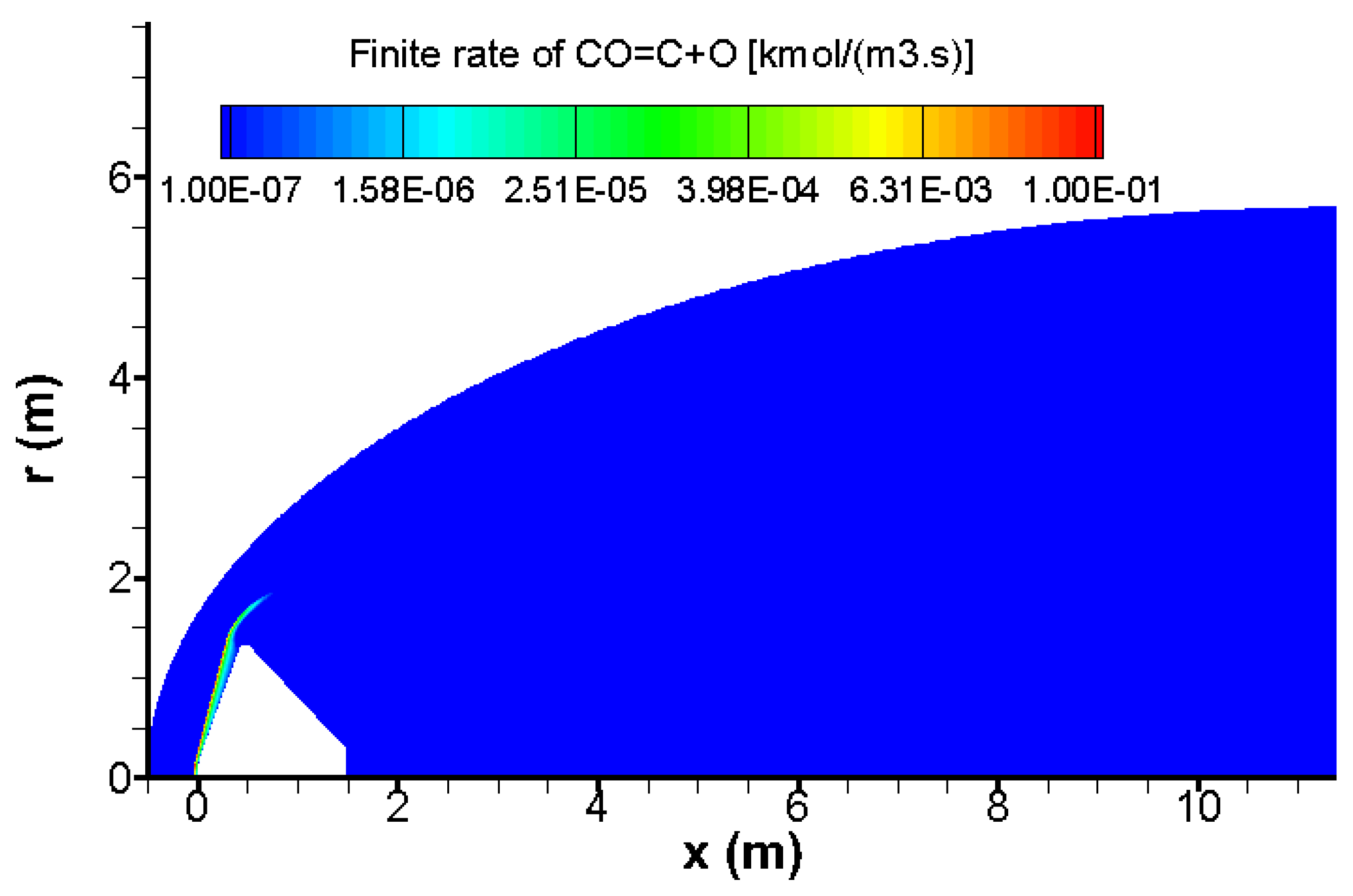

The quantity of carbon C generated by the chemical reactions CO → C + O, CO + O → C + O

2 and CO + CO → CO

2 + C is extremely small; its molar value does not exceed 0.0046 as shown in

Figure 11. This suggests that the kinetic rates of reactions that create carbon is very low. Indeed, the speeds of reactions CO

2 → CO + O, CO

2 + O → CO + O

2 and O2 → 2O are close and bigger with at least an order of magnitude than those of reactions that produce carbon C (CO → C + O, CO + O → C + O

2 and CO + CO → CO

2 + C) as shown in

Figure 10 and

Figure 12. For this reason, these three chemical reactions with low kinetic rates could be neglected in preliminary design of Mars entry vehicles.

5. Conclusions

This paper shows that the commercial CFD code Ansys Fluent with Mars 5-species McKenzie model [

13] is suitable to simulate Mars entry vehicles. Moreover, the modified Newtonian impact theory by Lester Lees provides very fast, useful information regarding the drag coefficient, which is the most important parameter to study the entry of Mars vehicles. Furthermore, the strong endothermal chemical reactions trigger by the bow wave and the conical shock waves, generate an impressive quantity of atomic and molecular oxygen.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Silber E.A., Hocking W.K., Niculescu M.L., Gritsevich M., Silber R.E. On shock waves and the role of hyperthermal chemistry in the early diffusion of overdense meteor trains. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2017, 469(2), 1869-1882. [CrossRef]

- Niculescu M.L., Silber E.A., Silber R.E. Production of nitric oxide by a fragmenting bolide: An exploratory numerical study. Mathematical Methods in the Applied Sciences 2020, 43(13), 7758-7773. [CrossRef]

- Niculescu M.L., Fadgyas M.C., Cojocaru M.G., Pricop M.V., Stoican M.G., Pepelea D. Computational hypersonic aerodynamics with emphasis on Earth reentry capsules. INCAS Bulletin 2016, 8(3), 55-64. [CrossRef]

- Mitcheltree R.A., Gnoffo P.A. Wake flow about the Mars Pathfinder entry vehicle. Journal of Spacecraft and Rockets 1995, 32(5), 771-776. [CrossRef]

- Yang X., Tang W., Gui Y., Du Y., Xiao G., Liu L. Hypersonic static aerodynamics for Mars science laboratory entry capsule. Acta Astronautica 2014, 103, 168-175. [CrossRef]

- Wang X., Yan C., Zheng W., Zhong K., Geng Y. Laminar and turbulent heating predictions for mars entry vehicles. Acta Astronautica 2016, 128, 217-228. [CrossRef]

- Wang X., Yan C., Ju S., Zheng Y., Yu J. Uncertainty analysis of laminar and turbulent aeroheating predictions for Mars entry. International Journal of Heat and Mass Transfer 2017, 112, 533-543. [CrossRef]

- Ansys Fluent, Theory Guide 2023, R1.

- McBride B.J., Zehe M.J., Gordon S. NASA Glenn coefficients for calculating thermodynamic properties of individual species. NASA TP-2002-211556 2002. https://ntrs.nasa.gov/citations/20020085330.

- Hirschfelder J.O., Curtiss C.F. Bird R.B. Molecular Theory of Gases and Liquids, John Wiley & Sons, New York, U.S.A., 1954.

- Bird G.A. The DSMC Method, Sydney, Australia, 2013. http://gab.com.au/.

- Chung T.J. Computational Fluid Dynamics, Cambridge University Press, United Kingdom, 2002; pp. 724-736. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/computational-fluid-dynamics/5C396317EE111C5ED1192FA7F8853944.

- McKenzie R.L., Arnold J.O. Experimental and theoretical investigations of the chemical kinetics and non-equilibrium CN radiation behind shock waves in CO2-N2 mixtures. AIAA 67-322 1967. [CrossRef]

- Hao J., Wang J., Gao Z., Jiang C., Lee C. Comparison of transport properties models for numerical simulations of Mars entry vehicles. Acta Astronautica 2017, 130, 24-33. [CrossRef]

- *** BETA CAE Systems S.A. ANSA User’s Guide, version 25.0.0, 2024.

- Liou M.S., Steffen C.J. A new flux splitting scheme. Journal of Computational Physics 1993, 107 (1), 23-39. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0021999183711228?via%3Dihub.

- Liou M.S. A sequel to AUSM: AUSM+. Journal of Computational Physics 1996, 129 (2), 364-382. https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/abs/pii/S0021999196902569.

- Liou M.S. A sequel to AUSM, Part II: AUSM+-up for all speeds. Journal of Computational Physics 2006, 214 (1), 137-170. [CrossRef]

- Mitcheltree R.A., Gnoffo P.A. Wake Flow about a MESUR Mars Entry Vehicle. 6th Joint Thermophysics and Heat Transfer Conference, Colorado Springs, (20-23 June 1994). [CrossRef]

- Park C., Howe J.T., Jaffe R.L., Candler G.V. Review of chemical-kinetic problems of future NASA missions, II: Mars entries. Journal of Thermophysics and Heat Transfer 1994, 8 (1), 9-23. [CrossRef]

- Pezzella G., Viviani A. Aerodynamic analysis of a Mars exploration manned capsule. Acta Astronautica 2011, 69, 975–986. [CrossRef]

- Viviani A., Pezzella G. Aerodynamic and Aerothermodynamic Analysis of Space Mission Vehicles, Springer Aerospace Technology, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 64–72.

- Anderson J.D. Hypersonic and High-Temperature Gas Dynamics, 3rd ed., AIAA Education Series, U.S.A., 2019; pp. 58-67. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).