1. Introduction

Carbon dots (CDs), a class of carbon-based nanomaterials, exhibit unique advantages such as biocompatibility [

1], cost-effectiveness [

2], tunable surface chemistry [

3], enabling applications in bioimaging [

4], photodynamic therapy [

5], and catalysis [

6]. Despite these merits, their broader implementation in sensing technologies is constrained by moderate quantum yields and processing limitations [

7,

8]. The abundant hydroxyl/carboxyl surface groups on CDs facilitate functionalization strategies [

9,

10,

11,

12]. Through reversible addition-fragmentation chain transfer (RAFT) polymerization, we previously demonstrated the grafting of homopolymers/copolymers onto CDs to enhance processability and expand functionality [

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18]. The discovery of aggregation-induced emission (AIE) by Tang et al. (2001) revolutionized luminescent material design [

19]. Tetraphenylethylene (TPE) derivatives have since emerged as superior AIE fluorophores due to their synthetic accessibility and photophysical properties [

20,

21,

22,

23,

24]. Unlike conventional fluorophores prone to aggregation-caused quenching, TPE derivatives exhibit suppressed emission in solution but intense luminescence upon aggregation, attributed to restricted intramolecular rotation that minimizes non-radiative decay [

19]. Despite these advantages, TPE’s hydrophobicity limits its aqueous applications. Strategic integration with water-soluble polymers or small molecules-particularly through amino-functionalization (–NH

2) enables pH-responsive fluorescence behavior for sensing applications [

25]. Concurrently, poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM), a thermoresponsive polymer with a lower critical solution temperature (LCST) of 30–34 °C [

26], undergoes reversible hydrophilic-to-hydrophobic transitions, making it ideal for stimuli-responsive systems [

27,

28].

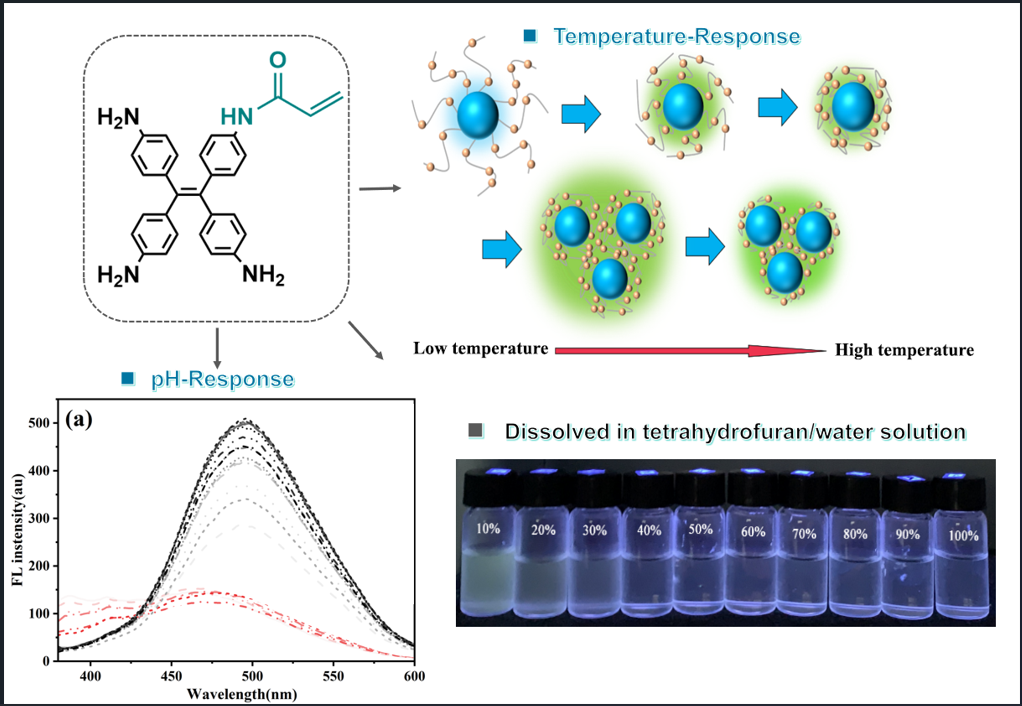

Building upon these foundational developments, we engineered a stimuli-responsive hybrid material through controlled copolymerization of Triaminotetrastyrene (ATPE) and N-isopropylacrylamide (NIPAM) at optimized molar ratios, followed by covalent grafting onto CDs surfaces. The resulting composite demonstrates pH-responsive aqueous dispersibility and thermoresponsive fluorescence switching. Under acidic conditions (pH < pKa), protonation of ATPE stabilizes materials dispersion through electrostatic repulsion, effectively suppressing the AIE effect. Conversely, at elevated pH (pH > pKa), deprotonation induces ATPE aggregation via hydrophobic interactions, leading to progressively enhanced AIE-driven fluorescence at 500 nm.

Concurrently, the hybrid material exhibits temperature-dependent behavior governed by the LCST transition of PNIPAM (32 °C). Above the LCST, PNIPAM chains undergo a hydrophilic-to-hydrophobic transition, promoting intermolecular association of ATPE units and activating AIE fluorescence. Below the LCST, polymer chain rehydration disassembles the aggregates, quenching the AIE effect. Remarkably, both pH- and temperature-triggered transitions demonstrate full reversibility over multiple cycles, as evidenced by dynamic light scattering (DLS) and fluorescence spectroscopy. This dual-stimuli responsiveness-combining pH-modulated dispersibility and temperature-controlled AIE activation-establishes the hybrid material as a promising candidate for sensing applications requiring environmental adaptability and signal reversibility.

2. Experimental

2.1. Materials

Sodium ethylenediaminetetraacetate dihydrate (EDTA), S-1-dodecyl-S’-(α,α’-dimethyl-α’’-acetic acid) trithiocarbonate (DATC), 4-dimethylaminopyridine (DMAP), azobisisobutyronitrile (AIBN) and N,N’-dicyclohexylcarbodiimide (DCC) were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (Shanghai) Trading Co.Ltd and used as received. ATPE and NIPAM were obtained from Hunan Weijia New Materials Co., Ltd. Dichloromethane (CH2Cl2), acryloyl chloride, triethylamine and tetrahydrofuran (THF) were provided by Aladdin Reagent (Shanghai) Co., Ltd. Distilled water was used in the experiment. All reagents and solvents were purchased as reagent grade and purified or dried by standard methods before use.

2.2. Preparation of the Hybrid Materials

2.2.1. Synthesis of CDs

CDs were synthesized via a bottom-up hydrothermal method following a previously reported procedure [

15,

16,

17]. Briefly, 5.0 g of EDTA and 30 mL of deionized water were placed in a high-pressure reactor, which was then sealed and heated in an oven at 220 °C for 48 h. After cooling to room temperature, the reaction mixture was filtered, and the filtrate was concentrated by rotary evaporation to yield a yellow gel-like product. The product was dissolved in anhydrous ethanol, stirred, and filtered to remove insoluble residues. This dissolution-filtration-evaporation cycle was repeated three times to obtain pure yellow CDs powder for further use.

2.2.2. Grafting of Chain Transfer Agents (CDs-DATC)

The grafting protocol was implemented as previously described [

15,

16,

17]. In a centrifuge tube, 1 g of CDs, 400 mg of DCC, 200 mg of DMAP, and 100 mg of DATC were vacuum-dried at 60 °C for 24 h to remove moisture. The mixture was then dissolved in CH

2Cl

2 and stirred for 7 days at room temperature under light-shielding conditions (DCC as a dehydrating agent and DMAP as a catalyst). After removing CH

2Cl

2 by rotary evaporation at 60 °C, the product was dissolved in ethanol, filtered to remove impurities, and concentrated again. The crude product was further purified by dialysis (MWCO: 500 Da) in absolute ethanol for 3 days (with solvent replacement every 8 h). Finally, the yellow CDs-DATC solution was rotary-evaporated to dryness, weighed, and stored for subsequent use.

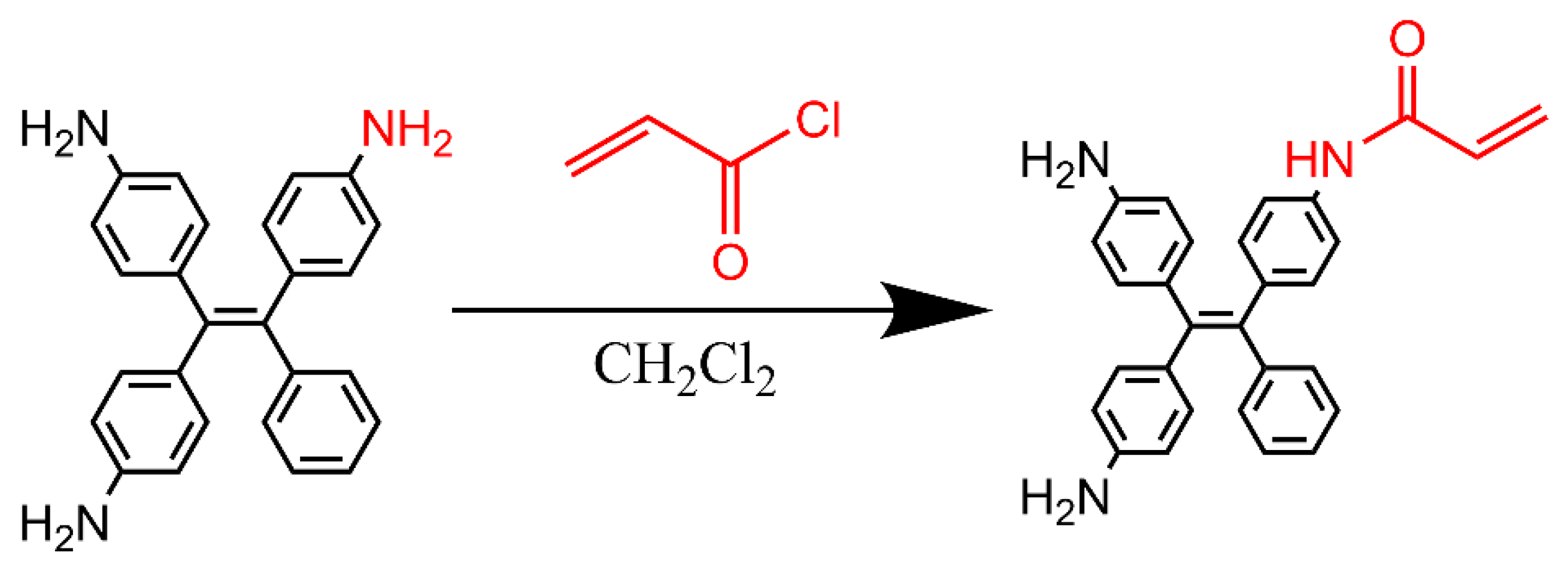

2.2.3. Synthesis of Acrylamido ATPE (Acr-ATPE)

The synthesis route is shown in

Scheme 1. In a 250 mL round-bottom flask, 100 mg of ATPE was dissolved in CH

2Cl

2 and stirred in an ice bath for 10 min. Then, 7.1 μL of acryloyl chloride and 12.2 μL of triethylamine were added dropwise via syringe, and the reaction was stirred at room temperature under light-shielding conditions for 4 h. After filtration and solvent removal by rotary evaporation, the product was washed three times with deionized water and vacuum-dried at 60 °C to yield a dark green solid (Acr-ATPE).

2.2.4. Preparation of CDs Grafted with Triaminotetraphenylethylene/N-isopropylacrylamide Copolymers (CDs-PNAT)

Briefly, 10 mg of CDs-DATC, 0.1 mg of AIBN, 50 mg of NIPAM, and varying weight ratios of Acr-ATPE were dispersed in THF in a single-necked flask. The mixture was transferred to a custom ampoule, degassed via freeze-pump-thaw cycles (6 × under nitrogen), and flame-sealed under vacuum. Polymerization was carried out at 70 °C for 24 h. The resulting product was precipitated in petroleum ether, refrigerated, and centrifuged. The collected solid was redissolved in THF and reprecipitated three times, then vacuum-dried to obtain CDs-PNAT1-4 (denoting different Acr-ATPE ratios, see

Table S1).

2.3. Characterizations

1H NMR spectra were recorded on a Bruker AM-400S spectrometer (400 MHz). Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectra were acquired using a Bruker Tensor 27 spectrophotometer (KBr pellet method). Fluorescence spectra were measured on a Hitachi F-4500 spectrometer (10 mm quartz cuvette, 90 ° detection geometry). TEM imaging was performed on a JEOL JEM-2010 microscope. Dynamic light scattering (DLS) was conducted on a Malvern Zetasizer Nano ZS90.

3. Results and discussion

3.1. Structure Characterizations of the Hybrid Materials

3.1.1. FTIR spectroscopy and 1H NMR spectrum

The chemical structural evolution of hybrid materials was systematically characterized using FTIR spectroscopy. As illustrated in

Figure S1, CDs exhibited a broad absorption band at 3500–3250 cm

–1, characteristic of O–H stretching vibrations. In contrast, CDs-DATC displayed distinct absorption features in the 2960–2850 cm

–1 region, corresponding to aliphatic C–H stretching vibrations of saturated hydrocarbons. The emergence of a diagnostic band at 1053 cm

–1, attributable to C=S bond stretching, confirmed successful covalent grafting of DATC moieties onto the CDs surface.

For CDs-PNAT hybrid materials, two prominent absorption bands were observed in the N–H stretching region (at 3350–3200 cm–1), consistent with primary amine functionalities. A well-defined peak at 3066 cm–1 arose from aromatic C–H stretching vibrations, while the absorption at 1462 cm–1 corresponded to benzene ring skeletal vibrations. Notably, a strong absorption band at 1654 cm–1 was assigned to amide carbonyl (C=O) stretching in the –CONH– linkage. Furthermore, the presence of isopropyl groups was evidenced by two symmetric absorption bands at 1350 cm–1, arising from C–H bending vibrations.

Complementary

1H NMR analysis (

Figure S2) of CDs-PNAT in deuterated chloroform (CDCl

3) provided additional structural validation. Resonances below

δ = 2 ppm were assigned to aliphatic protons (–CH

3, –CH

2–, and –CH–) within the N-isopropylacrylamide segments. The amide protons (–CONH–) manifested as a multiplet spanning

δ = 4.08–4.17 ppm. Diagnostic aromatic proton resonances for benzoxazine-bound ArH appeared as three distinct peaks at

δ = 5.91, 5.98, and 6.21 ppm, while the primary amine (–NH

2) resonance emerged at

δ = 5.34 ppm. Collectively, these spectral features confirm the successful covalent conjugation of ATPE/NIPAM copolymers onto the CDs surfaces through well-defined chemical linkages.

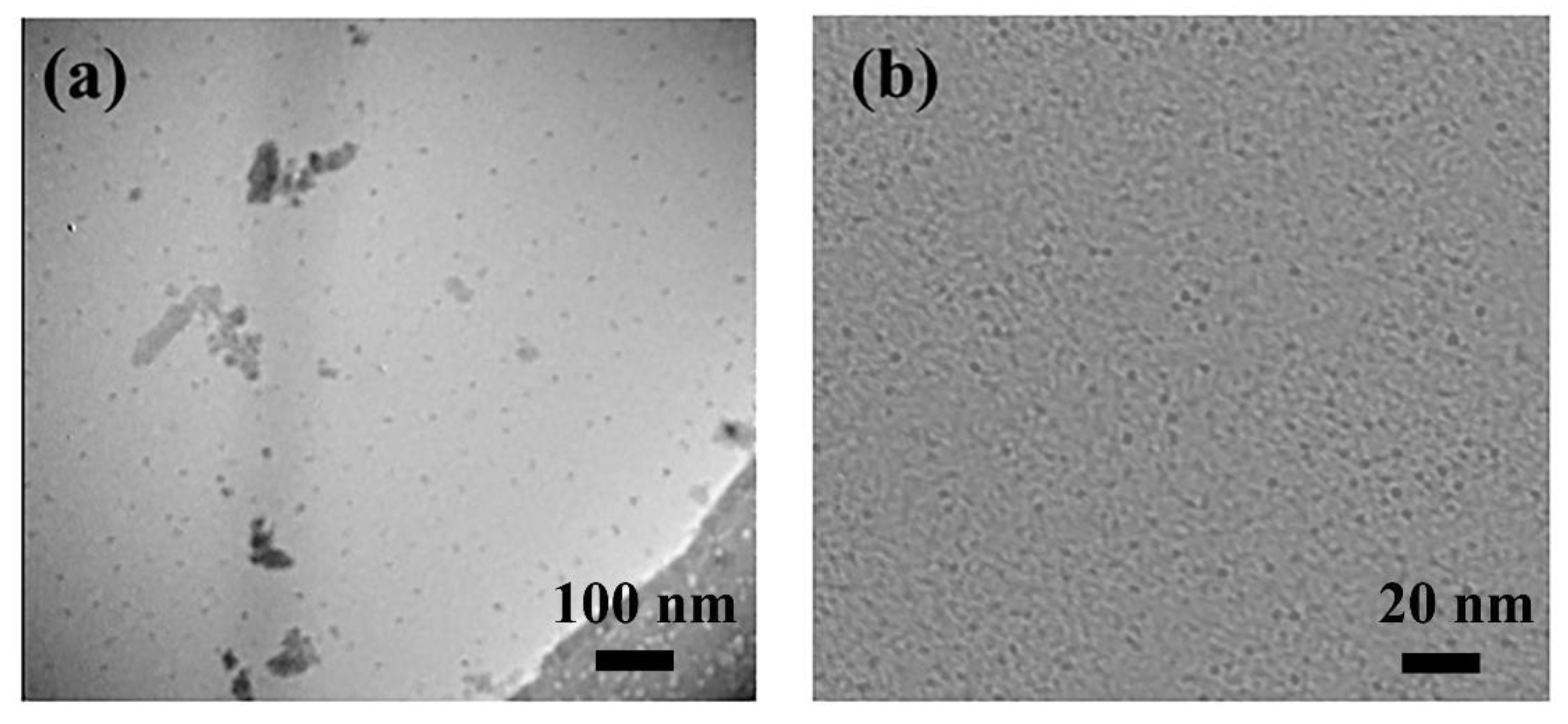

3.1.2. Morphologies of CDs-PNAT

By observing the characteristic micro-morphology and combining the results of FTIR and 1H NMR spectroscopy, we could further verify whether the copolymers of ATPE and NIPAM were successfully incorporated into the chemical structure of the CDs surfaces. As a key method for investigating morphological transitions in materials, TEM provided detailed imaging of their structural features.

Figure 1 illustrates the morphological differences between CDs and CDs-PNATs. The CDs exhibited a uniform size distribution, averaging around 2 nm. In contrast, CDs-PNATs showed a size range of approximately 20–30 nm, with relatively homogeneous dispersion and no significant agglomeration. The notable increase in particle size compared to bare CDs suggests that copolymers grafting led to an expansion of the CDs’ surface. These findings further confirm the successful grafting of copolymer chains onto the CDs’ surface.

3.2. Fluorescence Performances

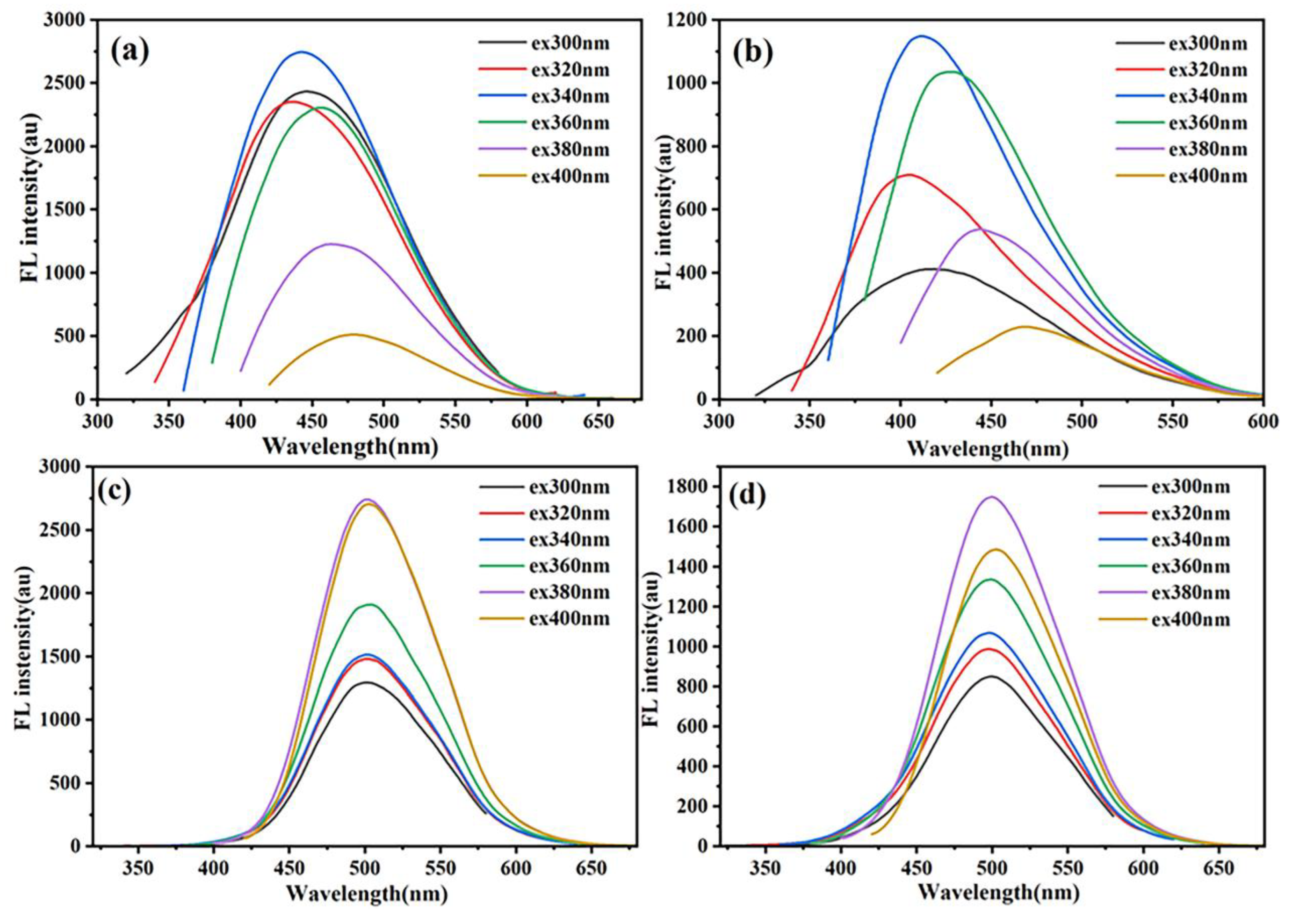

3.2.1. Characterization of Fluorescence Performances

As evidenced by the fluorescence spectra in

Figure 2, CDs-PNAT1 and CDs-PNAT2 dispersed in aqueous solution (pH = 4.8) exhibited excitation-dependent bathochromic shifts in their emission maxima, whereas CDs-PNAT3 and CDs-PNAT4 maintained stable emission profiles centered at 500 nm across varying excitation wavelengths. This divergence correlates with the structural characteristics of the hybrids: the ATPE moieties within CDs-PNATs undergo AIE under acidic conditions [

29,

30]. As shown in

Figure S3, the complementary data indicate that the pristine CDs exhibit characteristic excitation-wavelength-dependent red shifts, with a maximum emission at 450 nm under 360 nm excitation, which is consistent with the conventional fluorescence behavior of carbon dots.

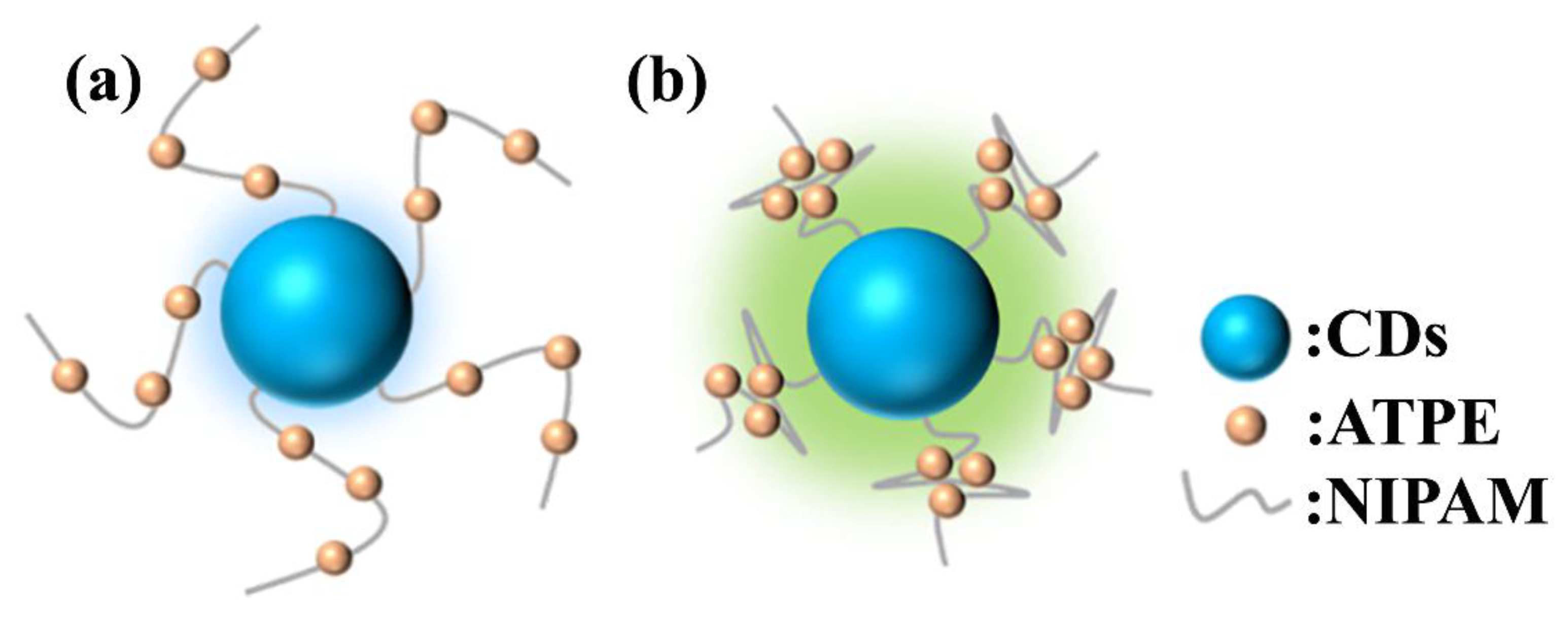

The distinct photophysical responses stem from structural variations in surface-grafted polymers. As illustrated in

Figure 3, CDs-PNAT1 and CDs-PNAT2, bearing lower phenylamino group densities, adopt extended polymer chain conformations in acidic media (

Figure 3a). This extended state facilitates near-complete protonation of phenylamino residues, suppressing ATPE aggregation and thereby minimizing AIE contributions. Consequently, their emission profiles predominantly reflect intrinsic CD fluorescence. In contrast, CDs-PNAT3 and CDs-PNAT4 with higher phenylamino densities exhibit restricted chain extension due to steric and electrostatic repulsions, leading to partial protonation and subsequent ATPE aggregation (see

Figure 3b). This structural reorganization triggers pronounced AIE effects, dominating the emission spectra and obscuring the underlying CDs fluorescence through intensity amplification.

To decouple AIE contributions from intrinsic CDs emission, comparative studies were conducted in THF, a solvent inhibiting ATPE aggregation.

Figure S4 reveals that all CDs-PNAT hybrid materials in THF exhibit excitation-dependent emission shifts analogous to pristine CDs, with no AIE-related stabilization at 500 nm. This solvent-dependent contrast conclusively attributes the 500 nm emission band observed in acidic aqueous media to AIE-active ATPE aggregates rather than CD-based fluorescence.

3.2.2. pH-Responsive Fluorescence Behavior

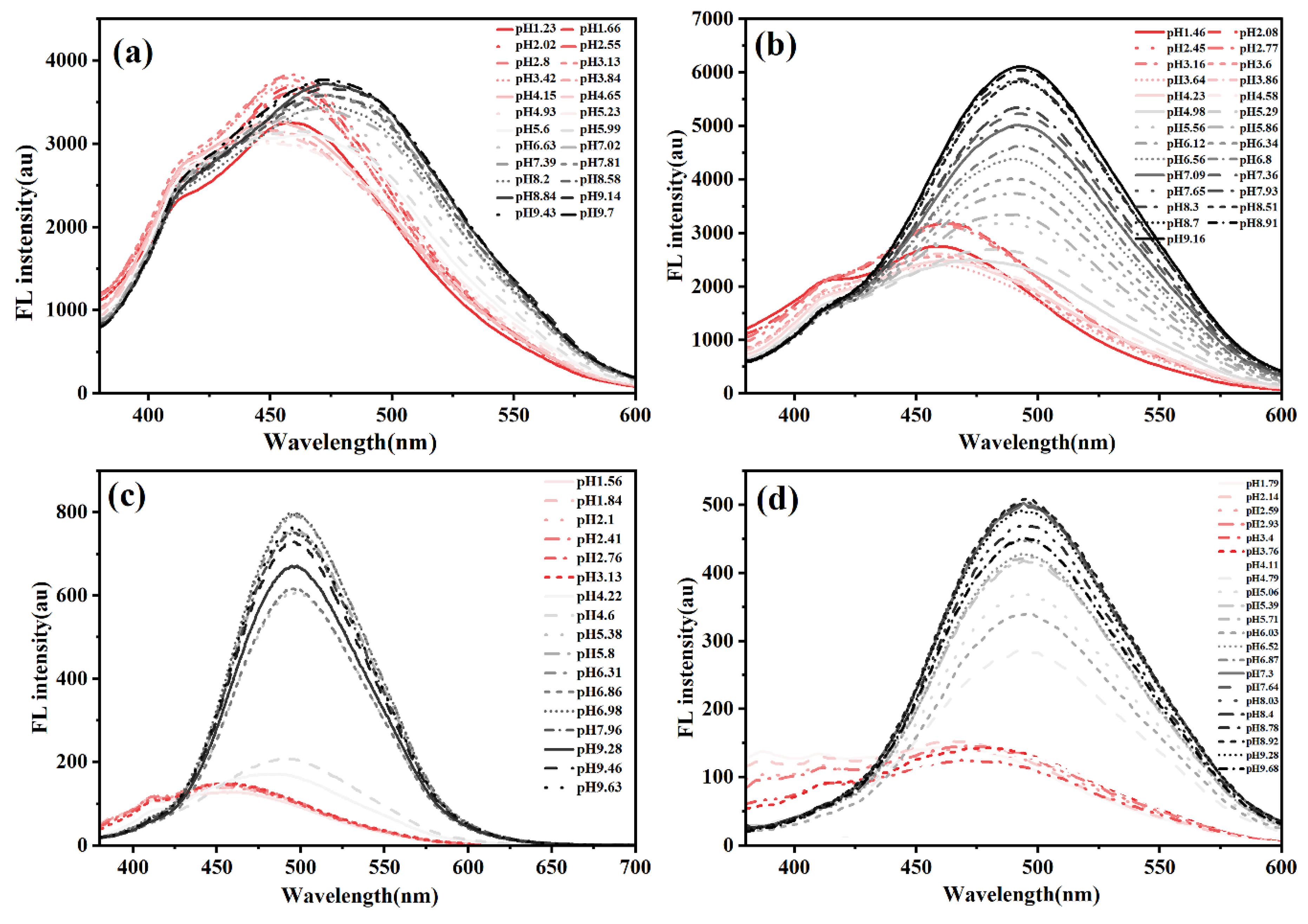

The protonation of exposed phenylamino moieties on ATPE groups within CDs-PNATs significantly modulates their hydrophilicity, as evidenced by pH-dependent fluorescence spectral shifts.

Figure 4 demonstrates the evolution of fluorescence profiles across varying pH conditions. For CDs-PNAT1 (see

Figure 4a), emission maxima remained stable at 450 nm below pH = 5.23, with minimal intensity fluctuations (< 10% RSD), indicative of unperturbed CD-dominated fluorescence. This observation aligns with the extended polymer chain conformations under acidic conditions that suppress the AIE effect of ATPE .

Above the critical pH threshold (pH > 5.23), a bathochromic shift to 500 nm occurred, accompanied by 3.2-fold intensity enhancement, confirming AIE dominance. CDs-PNAT2 exhibited analogous behavior (see

Figure 4b) with a lower transition pH (at 4.98), attributable to reduced phenylamino density enabling earlier deprotonation-induced aggregation. In contrast, CDs-PNAT3 and CDs-PNAT4 (see

Figure 4c-d) displayed higher transition pH values (at 4.22 and 4.11 respectively), consistent with their elevated phenylamino content requiring stronger acidity for complete protonation.

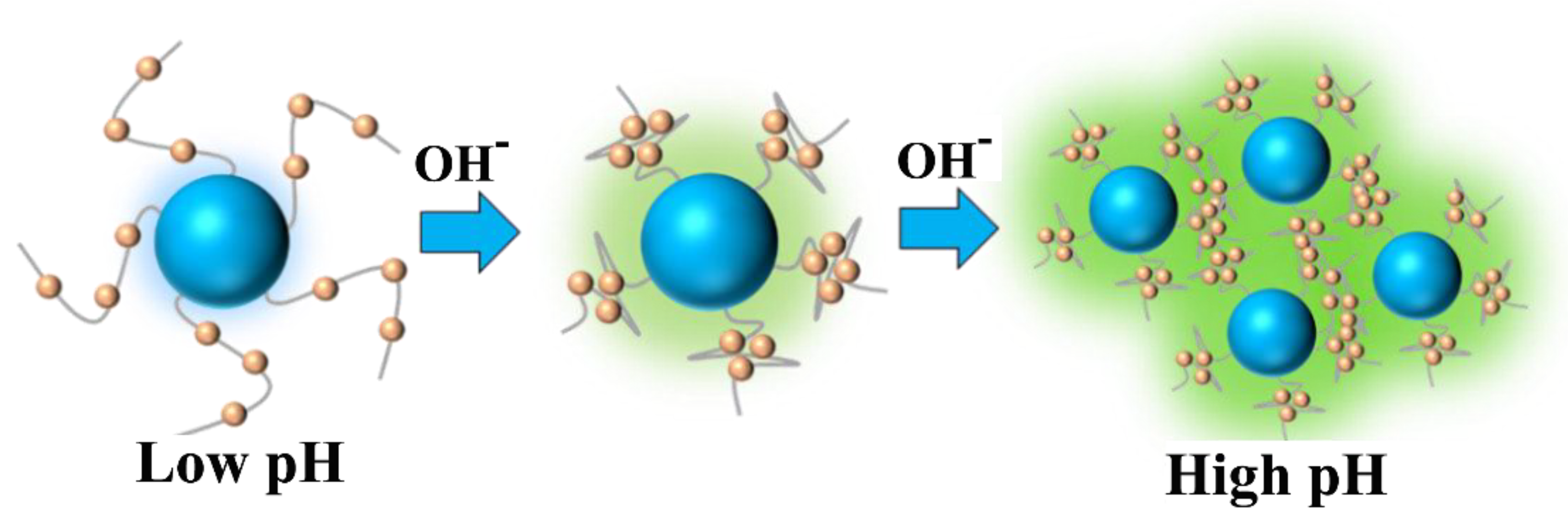

Figure 5 schematically illustrates the pH-dependent aggregation mechanism. Below critical pH thresholds, full protonation of phenylamino groups generates electrostatic repulsion forces, maintaining ATPE moieties in disaggregated states. Under these conditions, fluorescence originates solely from discrete CDs (λ

em = 450 nm). Exceeding the threshold pH initiates progressive deprotonation, reducing surface charge and enabling ATPE aggregation through hydrophobic interactions, thereby activating AIE (λ

em = 500 nm).

Notably, CDs-PNAT2 exhibited linear fluorescence quenching (R

2 = 0.994) within pH = 4.7–7.3 (see

Figure 6a), described by:

where

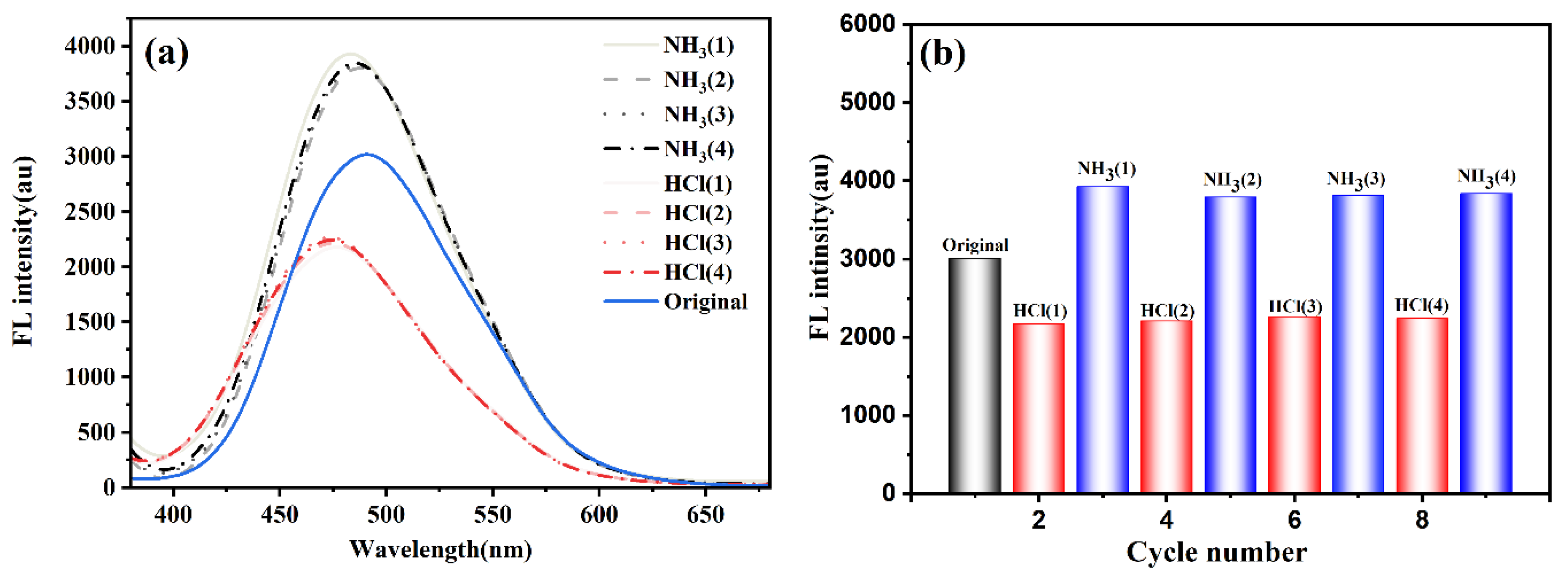

I represents fluorescence intensity at 500 nm. Cyclic tests (see

Figure 6b) revealed > 95% signal recovery over 4 cycles, demonstrating exceptional reversibility for reusable pH sensing applications.

Solid films exhibited stimuli-responsive behavior upon HCl/NH

3 vapor exposure (see

Figure S5). CDs-PNAT1/2 films showed dual emission at 475 nm (CDs) and 500 nm (weak AIE), with intensity modulation ratios of about 2 upon acid/base cycling. The attenuated AIE contribution correlates with low ATPE content. Conversely, CDs-PNAT3/4 films displayed pure AIE emission at 500 nm, achieving enhanced intensity upon NH

3 exposure due to deprotonation-induced aggregation. CDs-PNAT3 films demonstrated optimal responsiveness sustaining 95% initial intensity after 4 fumigation cycles (see

Figure 7), suggesting that the CDs-PNAT3 solid film exhibited a distinct response to the pH vapor. Hence, we contend that the CDs-PNAT3 solid film could function as a rather sensitive and recyclable pH vapor sensor.

3.2.3. Fluorescence Responsiveness to Temperatures

The copolymer-grafted CDs incorporate both pH-responsive ATPE units and thermosensitive poly(NIPAM) segments. This dual-functional design enables the CDs-PNATs hybrid materials to exhibit fluorescence responsiveness to both pH and temperature variations.

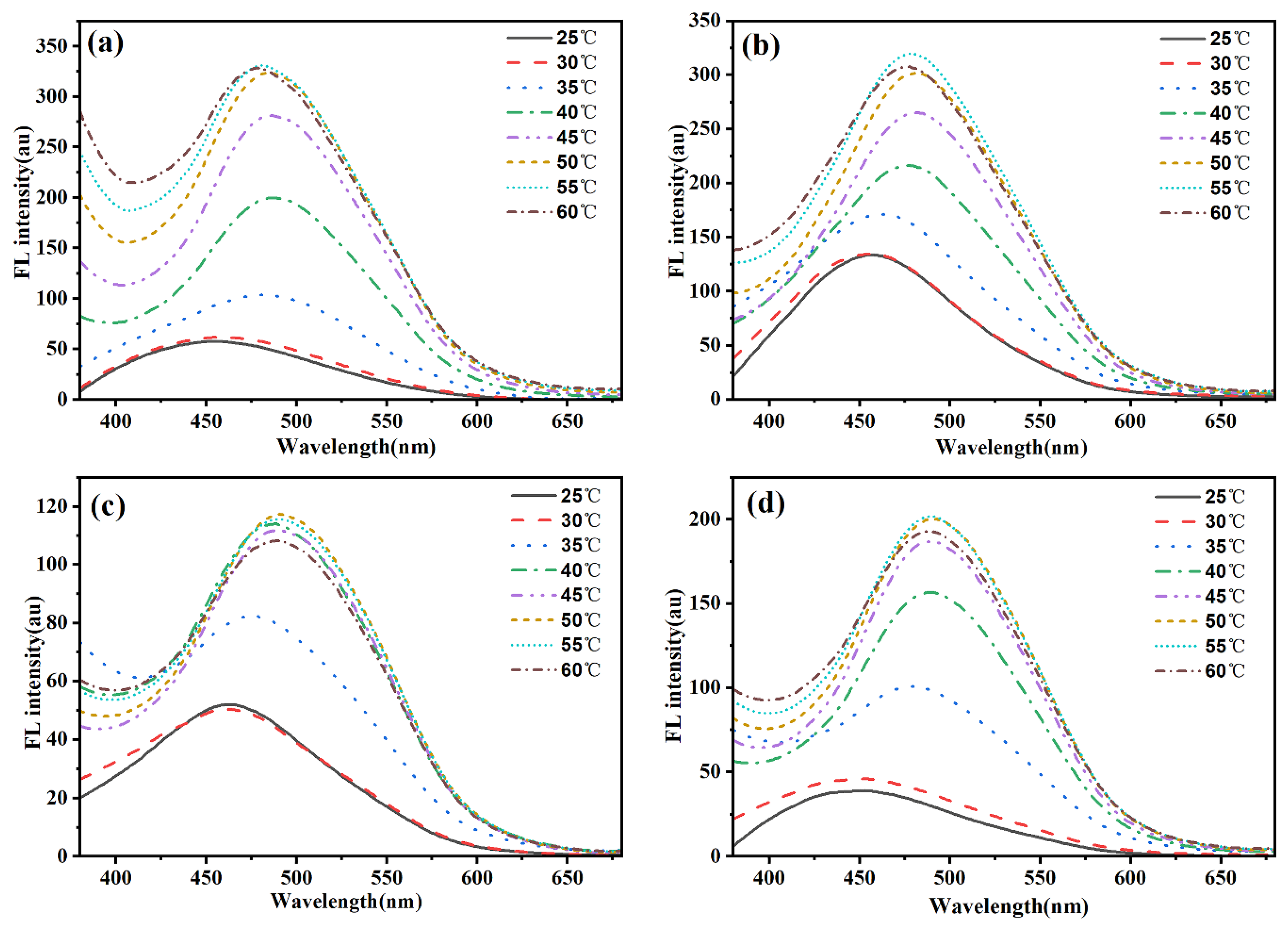

We systematically investigated the temperature-dependent fluorescence behavior of CDs-PNATs in acidic aqueous solutions (pH = 4.11) through programmed heating/cooling cycles (25–60 °C). As shown in

Figure 8, CDs-PNAT1 and CDs-PNAT2 exhibited emission peaks at 450 nm within 25–35 °C during heating. A distinct bathochromic shift to 500 nm occurred upon exceeding 40 °C, with complete reversibility (450 nm recovery) upon cooling to 25 °C (see

Figure S6). Similarly, CDs-PNAT3 and CDs-PNAT4 displayed analogous spectral shifts but with lower transition thresholds (at 30 °C during heating), confirming universal temperature responsiveness across all CDs-PNATs. These observations demonstrate that ATPE units exhibit AIE when temperatures surpass the LCST, regardless of heating/cooling direction.

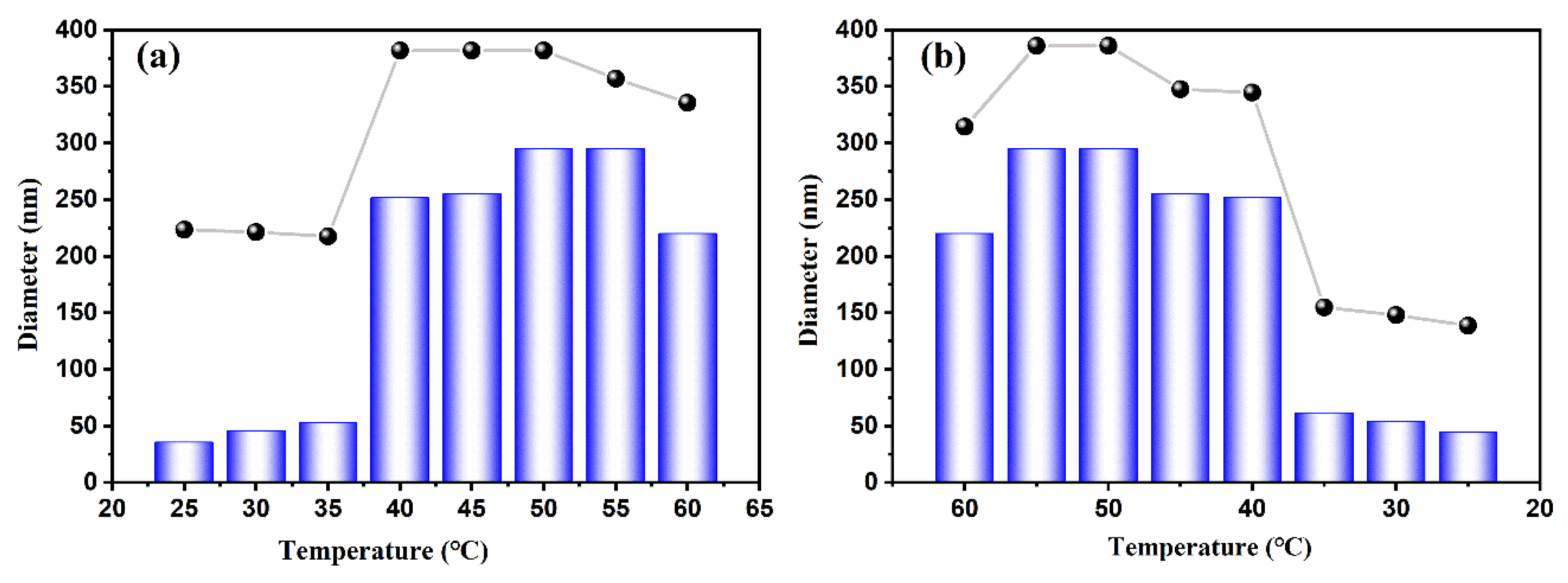

The AIE mechanism was further elucidated by monitoring hydrodynamic diameter variations (see

Figure 9). CDs-PNAT4 maintained stable nanoparticles (about 30 nm) during initial heating (25–35 °C), as shown in

Figure 9a, upon reaching the LCST (32 °C), the diameter abruptly decreased to 15 nm at 35 °C due to PNIPAM chain collapse, followed by a dramatic increase to 300 nm at 40 °C through hydrophobic-driven supramolecular assembly. Remarkably, the original particle size (30 nm) was fully restored upon cooling to 25 °C, demonstrating exceptional reversibility (see

Figure 9b).

This thermoresponsive behavior originates from PNIPAM’s conformational transitions. When the temperature is below the LCST, the hydrated polymer chains maintain extended conformations that effectively suppress ATPE aggregation through steric stabilization [

31,

32]. As the temperature rises above the LCST, the hydrophobic chain collapse exposes ATPE moieties, triggering the formation of AIE-active aggregates characterized by strong emission at 500 nm. At elevated temperatures exceeding 40 °C, enhanced interparticle interactions promote the formation of large-scale aggregates while simultaneously intensifying the AIE effects through strengthened molecular packing and restricted intramolecular motions [

33,

34,

35]

. During cooling, hydrophilic chain rehydration dissociates ATPE aggregates, restoring the initial 450 nm emission. DLS-confirmed size recovery validates the system’s thermodynamic reversibility, with complete fluorescence and structural reset achieved within each thermal cycle.

4. Conclusions

The copolymers of ATPE and NIPAM were successfully grafted onto the surface of CDs, resulting in the formation of hybrid CDs-PNATs materials. These CDs-PNATs demonstrated dual fluorescence responsiveness to pH and temperature variations. Notably, a distinct pH threshold governed their fluorescence behavior: when the pH was below this threshold, the fluorescence emission peak at 450 nm originated from the CDs, whereas above the threshold, a redshifted emission peak at 500 nm emerged due to the AIE effect of ATPE. The threshold pH value decreased with increasing ATPE content, which correlated directly with the elevated number of phenylamino groups on ATPE. Cyclic fumigation tests with pH/NH3 vapor revealed that the CDs-PNAT3 solid film exhibited high sensitivity and recyclability as a dual-mode sensor. Furthermore, the fluorescence emission peaks of CDs-PNATs shifted reversibly from 450 to 500 nm upon heating from 25 to 50 °C, and recovered to the original wavelength upon cooling back to 25 °C, demonstrating excellent thermal cycling stability. These findings highlight the potential of CDs-PNATs as promising candidates for temperature and pH sensing applications. There are still some areas in the current work that needs improvement and further research. It is necessary to explore how to achieve the controllable structural formation of the hybrid material in the solutions for their fluorescence responsiveness. Furthermore, the application of the hybrid material as a sensor deserves further investigation to fully explore its potential.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org, Figure S1: The changes in the chemical structures of FTIR spectrum for CDs, CDs-DATC and CDs-PNAT; Figure S2: 1H NMR spectrum of CDs-PNAT; Figure S3: The fluorescence emission spectra of CDs aqueous solution at different excitation wavelengths; Figure S4: The fluorescence emission spectrum of the materials dissolved in THF at different excitation wavelengths (a): CDs-PNAT1; (b): CDs-PNAT2; (c): CDs-PNAT3; (d): CDs-PNAT4; Figure S5: The fluorescence emission spectra of the solid films fumigated with HCl and NH3 (a): CDs-PNAT1; (b): CDs-PNAT2; (c): CDs-PNAT3; (d): CDs-PNAT4; Figure S6: The fluorescence emission spectrum of CDs-PNATs in the acidic aqueous solutions at the different temperatures during cooling (a): CDs-PNAT1; (b): CDs-PNAT2; (c): CDs-PNAT3; (d): CDs-PNAT4; Table S1: Weight ratios of the precursors for the samples: CDs-PNAT1, CDs-PNAT2, CDs-PNAT3 and CDs-PNAT4.

Author Contributions

H.L.: writing–review & editing, resources, funding acquisition; Y.X.D.: writing–review & editing, writing–original draft, software, data curation; L.P.Z.: writing–original draft, visualization; S.R.X.: data curation, supervision; B.L.: writing–review & editing, project administration, funding acquisition.

Funding

This work gratefully acknowledge the financial support of the Key Research and Development Project of Hunan Province in China (Grant No. 2023GK2028), Major Basic Research Projects in Hunan Province (Grant No. 2024JC0005), National Natural Science Foundation of China Regional Joint Fund Key Program (Grant No. U24A20302) and Natural Science Foundation of Hunan Province (Grant No. 2025JJ50070),

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Madhusudhan, A.; Suhagia, T.A.; Sharma, C.; Jaganathan, S.K.; Purohit, S.D. Carbon Based Polymeric Nanocomposite Hydrogel Bioink: A Review. Polymers 2024, 16, 3318. [CrossRef]

- Ren, J.; Malfatti, L.; Innocenzi, P. Citric Acid Derived Carbon Dots, the Challenge of Understanding the Synthesis-Structure Relationship. C 2020, 7, 2. [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Pieber, B.; Delbianco, M. Modulating the Surface and Photophysical Properties of Carbon Dots to Access Colloidal Photocatalysts for Cross-Couplings. ACS Catal. 2022, 12, 13831–13837. [CrossRef]

- Araújo, C.; Rodrigues, R.O.; Bañobre-López, M.; Silva, A.M.T.; Ribeiro, R.S. Carbon Dots as a Fluorescent Nanosystem for Crossing the Blood–Brain Barrier with Plausible Application in Neurological Diseases. Pharmaceutics 2025, 17, 477. [CrossRef]

- Suner, S.S.; Bhethanabotla, V.R.; Ayyala, R.S.; Sahiner, N. Rapid Pathogen Purge by Photosensitive Arginine–Riboflavin Carbon Dots without Toxicity. Materials 2023, 16, 6512. [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Ding, Z.; Li, Y.; Xi, F.; Liu, J. Magnetic Nanozyme Based on Loading Nitrogen-Doped Carbon Dots on Mesoporous Fe3O4 Nanoparticles for the Colorimetric Detection of Glucose. Molecules 2023, 28, 4573. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhao, Z.; Ma, T.; Bai, J. Aptamer Paper-Based Fluorescent Sensor for Determination of SARS-CoV-2 Spike Protein. Sensors 2025, 25, 1637. [CrossRef]

- Kandasamy, G. Recent Advancements in Doped/Co-Doped Carbon Quantum Dots for Multi-Potential Applications. C 2019, 5, 24. [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Long, P.; He, B.Q. Reverible fluorescence modulation of spiropyran-functionalized carbon nanparticles. J. Mater. Chem. C 2013, 1, 3716.

- Zheng, X.; Zhang, H.; Jiang, H.; Sun, L.; Sun, Y.; Liu, Q.; Ren, S.; Zhuang, Y.; Gong, X. Controllable Functionalization of Carbon Dots as Selective and Sensitive Fluorescent Probes for Sensing Cu(II) Ions. Crystals 2025, 15, 205. [CrossRef]

- Egorova, M.; Tomskaya, A.; Smagulova, S.A. Optical Properties of Carbon Dots Synthesized by the Hydrothermal Method. Materials 2023, 16, 4018. [CrossRef]

- Hu, S.; Tian, R.; Dong, Y.; Yang, J.; Liu, J.; Chang, Q. Modulation and effects of surface groups on photoluminescence and photocatalytic activity of carbon dots. Nanoscale 2013, 5, 11665–11671. [CrossRef]

- Cui, F.; Sun, J.; Ji, J.; Yang, X.; Wei, K.; Xu, H.; Gu, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Sun, X. Carbon dots-releasing hydrogels with antibacterial activity, high biocompatibility, and fluorescence performance as candidate materials for wound healing. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 406, 124330. [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Wang, W.; Long, P.; Deng, X.; He, B.; Liu, Q.; Yi, S. The carbon nanoparticles grafted with copolymers of styrene and spiropyran with reversibly photoswitchable fluorescence. Carbon 2015, 91, 30–37. [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Wang, W.; Long, P.; He, B.; Li, F.; Liu, Q. Synthesis of fluorescent carbon nanoparticles grafted with polystyrene and their fluorescent fibers processed by electrospinning. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 57683–57690. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liao, B.; Yi, S.; Liang, E.; He, B. Tetraphenylethylene and N-isopropylacrylamide block polymer-grafted carbon dots with their application in cellular imaging. Mater. Today Chem. 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Liao, B.; Liang, E.; Yi, S.; Liao, Q. Reversible light-controlled fluorescence switch of block polymer-grafted carbon dots and cellular imaging. Soft Matter 2022, 18, 8017–8023. [CrossRef]

- Liao, B.; Liu, X.; Liao, S.; Liu, W.; Yi, S.; Liu, Q.; He, B. N-isopropylacrylamide and spiropyran copolymer-grafted fluorescent carbon nanoparticles with dual responses to light and temperature stimuli. Polym. J. 2020, 52, 1289–1298. [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.D.; Xie, Z.L.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Cheng, L.; Chen, H.Y.; Qiu, C.F.; Kwok, H.S.; Zhan, X.W.; Liu, Y.Q.; Zhu, D.B.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-induced emission of 1-methyl-1,2,3,4,5-pentaphenylsilole. Chem. Commun. 2001, 18, 1740.

- Ji, Y.M.; Hou, M.; Zhou, W.; Ning, Z.W.; Zhang, Y.; Xing, G.W. An AIE-active nir fluorescent probe with good water solubility for the detection of Aβ1–42 aggregates in Alzheimer’s disease. Molecules 2023, 28, 5110. [CrossRef]

- Picchi, A.; Wang, Q.; Ventura, F.; Micheletti, C.; Heijkoop, J.; Picchioni, F.; Ciofini, I.; Adamo, C.; Pucci, A. Effect of Polymer Composition on the Optical Properties of a New Aggregation-Induced Emission Fluorophore: A Combined Experimental and Computational Approach. Polymers 2023, 15, 3530. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Y.; Lam, J.W.; Tang, B.Z. Aggregation-induced emission: phenomenon, mechanism and applications. Chem. Commun. 2009, 29, 4332.

- Chai, C.; Zhou, T.; Zhu, J.; Tang, Y.; Xiong, J.; Min, X.; Qin, Q.; Li, M.; Zhao, N.; Wan, C. Multiple Light-Activated Photodynamic Therapy of Tetraphenylethylene Derivative with AIE Characteristics for Hepatocellular Carcinoma via Dual-Organelles Targeting. Pharmaceutics 2022, 14, 459. [CrossRef]

- Ye, X.; Wang, H.; Yu, L.; Zhou, J. Aggregation-Induced Emission (AIE)-Labeled Cellulose Nanocrystals for the Detection of Nitrophenolic Explosives in Aqueous Solutions. Nanomaterials 2019, 9, 707. [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Bender. M.; Seehafer, K.; Wacker, I.; Schröder, R.R.; Bunz, U.H.F. Novel functional TPE polymers: aggregation-induced emission, pH response, and solvatochromic behavior. Macrom. Rapid Comm. 2019, 40, 1800774. [CrossRef]

- Halperin, A.; Kröger, M.; Winnik, F.M. Poly (N-isopropylacrylamide) phase diagrams: fifty years of research. Angew. Chem. Int. Edit. 2015, 54, 15342.

- Zhou, L.; Liao, B.; Yang, S.; Yi, S. Carbon dots and gold nanocluster–based hybrid microgels and their application in cells imaging. J. Nanoparticle Res. 2022, 24, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Colaco, R.; Appiah, C.; Staubitz, A. Controlling the LCST-Phase Transition in Azobenzene-Functionalized Poly (N-Isopropylacrlyamide) Hydrogels by Light. Gels 2023, 9, 75. [CrossRef]

- Su, G.; Li, Z.; Dai, R. Recent Advances in Applied Fluorescent Polymeric Gels. ACS Appl. Polym. Mater. 2022, 4, 3131–3152. [CrossRef]

- Su, H.; Deng, Z.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhao, Z.; Tang, B.Z. A brightly red emissive AIEgen and its antibody conjugated nanoparticles for cancer cell targeting imaging. Mater. Chem. Front. 2022, 6, 1317–1323. [CrossRef]

- Kostyurina, E.; De Mel, J.U.; Vasilyeva, A.; Kruteva, M.; Frielinghaus, H.; Dulle, M.; Barnsley, L.; Förster, S.; Schneider, G.J.; Biehl, R.; et al. Controlled LCST Behavior and Structure Formation of Alternating Amphiphilic Copolymers in Water. Macromolecules 2022, 55, 1552–1565. [CrossRef]

- Manfredini, N.; Gardoni, G.; Sponchioni, M.; Moscatelli, D. Thermo-responsive polymers as surface active compounds: A review. Eur. Polym. J. 2023, 198. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Zhang, H.; Lam, J.W.Y.; Tang, B.Z. Restriction of Intramolecular Motion(RIM): Investigating AIE Mechanism from Experimental and Theoretical Studies. Chem. Res. Chin. Univ. 2021, 37, 1–15. [CrossRef]

- Liao, Q.; Li, Q.; Li, Z. The Key Role of Molecular Packing in Luminescence Property: From Adjacent Molecules to Molecular Aggregates. Adv. Mater. 2023, e2306617. [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Shan, G.; Qin, C.; Liu, S. Polymerization-Enhanced Photophysical Performances of AIEgens for Chemo/Bio-Sensing and Therapy. Molecules 2022, 28, 78. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).