1. Introduction

Cape gooseberry (

Physalis peruviana Linn.), a member of the Solanaceae family, has gained attention due to its agronomic versatility, nutritional profile, and potential for value-added processing [

1,

2,

3]. In Thailand, the Royal Project Foundation has integrated cape gooseberry into highland agriculture to support the sufficiency economy philosophy, emphasizing environmental stewardship, social inclusion, and economic resilience [

4,

5]. However, cape gooseberry production faces challenges, with up to 60% of fruits being downgraded due to cosmetic defects that do not compromise nutritional value but render them unsuitable for fresh markets. This issue is compounded by the reliance on expensive and complex imported food processing equipment, poorly suited to the needs of small-scale farmers [

6]. Osmotic dehydration (OD) has emerged as a practical strategy to reduce postharvest losses and add value to grade-out fruits. This non-thermal pretreatment allows partial water removal and solute infusion, stabilizing the fruit while preserving nutritional and sensory properties [

7]. The effectiveness of OD can be significantly enhanced by integrating mild hydrostatic pressure, improving mass transfer and offering microbiological benefits [

8].

Hot-air drying commonly follows OD to reach the desired final moisture content. Although traditional hot-air drying is cost-effective, it often results in uneven drying and nutrient degradation. Rotary tray dryers address these issues by ensuring controlled airflow and temperature consistency, helping preserve quality attributes [

9]. Adopting hydrostatic pressure-assisted OD combined with rotary tray drying represents a transformative solution that integrates food security, resource efficiency, postharvest innovation, and community development. However, research on this combination for underutilized, grade-out fruits in highland agricultural settings is lacking, with few studies providing comprehensive assessments [

7,

9].

This study aims to investigate the effect of hydrostatic pressure-assisted osmotic pretreatment on the drying behavior and quality of grade-out cape gooseberry from highland areas. Specifically, it evaluates the impact of pretreatment at 0.5 bar for 12 hours and subsequent hot-air drying at 50°C, 60°C, and 70°C on various parameters. A preliminary cost analysis is also conducted to assess the feasibility of adopting this value-adding technology for highland smallholder farmers.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

Fresh cape gooseberry fruits were purchased directly from highland farmers at the Mae Hae Royal Project Development Center in Chiang Mai, Thailand. The procurement standards required fully ripe fruits with a minimum diameter of 2.5 cm and husks free from fungal spots. Fruits meeting these criteria were purchased at 2.5 USD per kilogram, while undersized fruits (below 2.5 cm diameter) were categorized as substandard but still marketable and purchased at 0.5 USD per kilogram. Fruits displaying evident mold on the calyx or skin fissures were deemed unacceptable for fresh market consumption. These discarded fruits, termed grade-out cape gooseberry, are generally unsuitable for animal feed or organic fertilizer due to their capacity to modify soil acidity. Consequently, they were chosen as raw materials for this study to investigate value-added processing options.

Figure 1 shows representative examples of the grade-out cape gooseberry utilized in this experiment.

Prior to pretreatment, the grade-out cape gooseberry was washed, trimmed, rinsed with clean water, and immersed in a 1000 ppm potassium metabisulfite (KMS) solution for 10 minutes. KMS has been widely adopted in fruit processing to inhibit microbial growth and enzymatic browning by suppressing polyphenol oxidase activity and extending product shelf life [

10]. After soaking, the excess solution was drained off, and the fruits were air-dried in preparation for the hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment process.

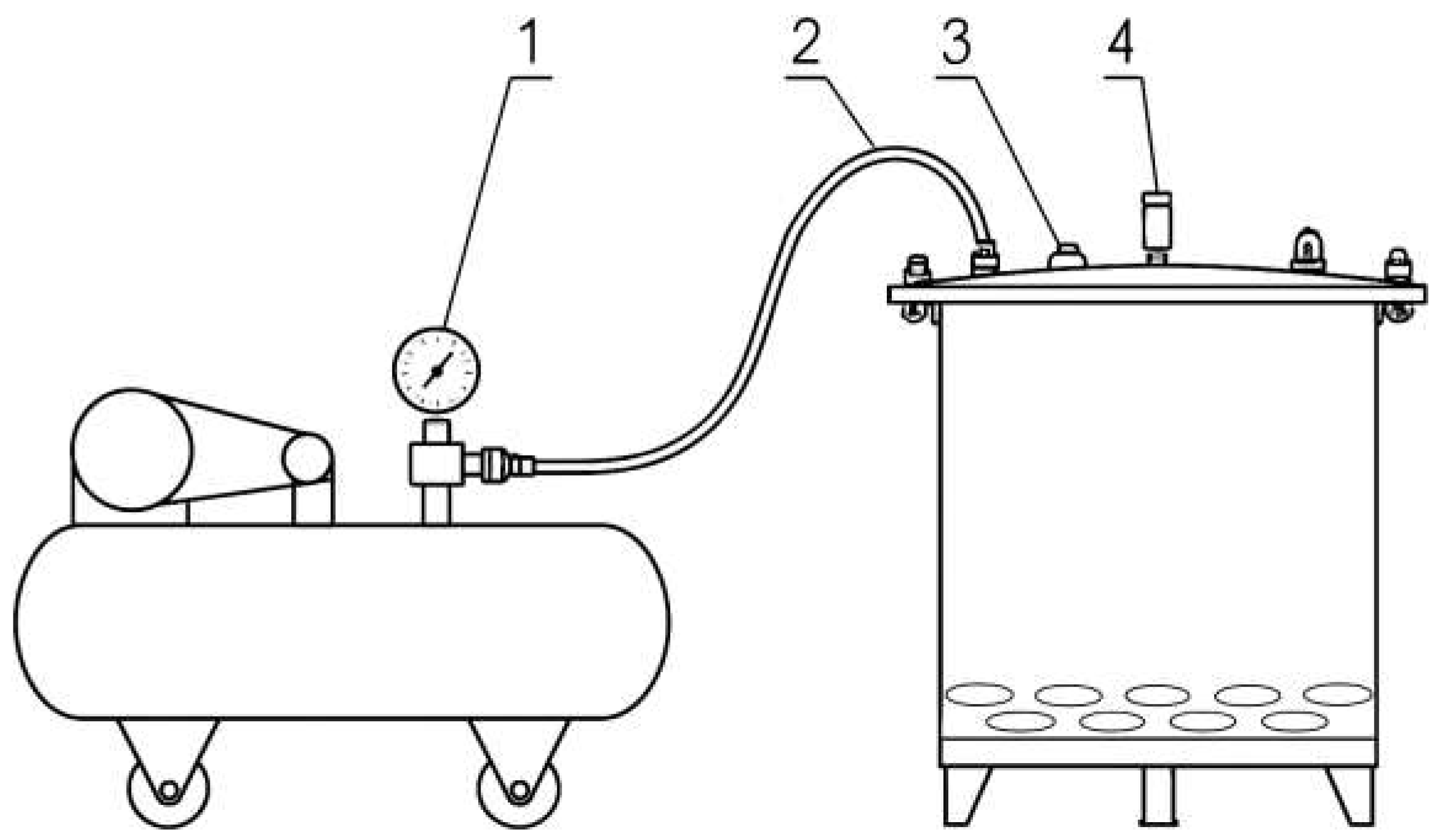

2.2. Hydrostatic Osmotic Pretreatment

The hydrostatic osmotic system (

Figure 2) consisted of a 50-liter autoclave chamber constructed from 0.6 mm thick SUS 304-grade stainless steel. The equipment was developed by the Smart Farm Engineering and Agricultural Innovation Program, School of Renewable Energy, Maejo University, Thailand. The cover of the pressure vessel was designed to work in conjunction with an air compression system, which included a pneumatic pump and a safety valve set at 0.5 bar to ensure stable internal pressure throughout the pretreatment process. We prepared an osmotic solution of 55°Brix by dissolving 11 kg of commercial sucrose in 9 liters of water and heating it to 95°C for 10 minutes. After cooling, 20 g of food-grade citric acid and 1,000 mL of glycerin were added and mixed thoroughly [

11]. Ascorbic acid helps prevent browning by stopping an enzyme called polyphenol oxidase, while glycerin keeps things moist and improves texture and color [

12]. For pretreatment, 40 kg of grade-out cape gooseberry were placed in the 50-liter pressure vessel, and the prepared solution (20 liters) was added. The cover was sealed, and air pressure was applied to maintain 0.5 bar. The fruits were held under mild hydrostatic pressure for 12 hours to facilitate solute uptake and controlled dehydration.

2.3. Development of Rotary Tray Dryer

The rotary tray dryer used in this study incorporates a rotating tray system designed to improve heat distribution efficiency and facilitate the transfer of appropriate technology to community-level applications. This dryer has been registered under Thailand's petty patent number 18896 and was developed in compliance with national industrial standards. The equipment is constructed with stainless steel components (SUS304 grade) to ensure durability and food-grade hygiene. Detailed specifications and operational descriptions of the system have been previously reported by Assawarachan [

6].

Figure 3 provides a schematic representation of the drying system.

2.3. Drying Parameter

2.3.1. Moisture Content

The moisture content of the samples was determined according to AOAC Official Method 920.151 [

13]. Approximately 5 g of each sample was weighed before and after drying at 70°C under vacuum conditions (pressure not exceeding 100 mmHg) until a constant weight was achieved. The moisture content was calculated both on a wet basis (%w.b.) and a dry basis (%d.b.) using the following equations

The drying characteristics of cape gooseberry samples were evaluated based on AOAC Official Method 920.151 [

13], measuring the drying rate and moisture content (g water/g dry matter, DM). Samples were collected at hourly intervals

.

2.3.2. Determination of Water Loss and Solid Gain

Water loss (WL) and solid gain (SG) were evaluated to assess mass transfer during osmotic dehydration. Fresh cape gooseberry were weighed (W₀), then immersed in a 55 °Brix sucrose solution under mild hydrostatic pressure (0.5 bar). After treatment, excess surface solution was blotted, and the samples were reweighed (W₁). Dry matter contents of both untreated and treated samples were determined by vacuum oven drying at 70°C under vacuum conditions to constant weight. The calculations for WL and SG were based on the mass balance approach, as described by Torreggiani and Bertolo [

14]:

where ww0 is the weight of water and ws0 is the weight of solids initially present in the fruit, since wt and wst are the weight of the fruit and the weight of the solids at the end of the treatment, respectively.

2.4. Optical Properties

The color of cape gooseberry samples was measured using a Chroma Meter (CR-400, Konica Minolta, Inc., Tokyo, Japan) in the CIE Lab color space, with calibration performed using a white standard (Y = 93.9, x = 0.3160, y = 0.3323). Measurements were taken under D65 illumination with an 8 mm aperture. The L*, a*, and b* values were recorded from three positions on each sample and averaged. L* indicates lightness, a* redness to greenness, and b* yellowness to blueness. Triplicate samples were analyzed. Color difference (ΔE) from the control was calculated as:

where L₀*, a₀*, and b₀* refer to the values of the control or untreated sample.

2.5. Determination of Vitamin C, Carotenoids, Total Phenolic Content, and Antioxidant Capacity

Vitamin C Determination: Ascorbic acid content was analyzed at each stage of hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment. Ten grams of sample were homogenized with 3% metaphosphoric acid (50 mL), filtered, and measured at 520 nm using the DCPIP titration method [

15]. Results were expressed as mg/100 g fresh weight.

Total Phenolic Content Determination: TPC was measured using the Folin Ciocalteu method [

16]. Extracts were mixed with Folin--Ciocalteu reagent, sodium carbonate, and incubated for 1 hour in the dark. Absorbance was read at 725 nm, and values were expressed as mg gallic acid equivalent per 100 g fresh weight.

Antioxidant Capacity (ABTS): Antioxidant activity was assessed using the ABTS radical cation assay [

16]. The ABTS⁺ solution was prepared in advance, diluted to 0.70 absorbance at 730 nm, and reacted with sample extract for 30 minutes at 30°C. Absorbance was measured at 730 nm, and results were expressed as µmol Trolox equivalent per gram.

Antioxidant Capacity (DPPH): The DPPH radical scavenging activity was measured following the method of Ignat et al. [

17]. A 0.2 mM DPPH solution was prepared in 95% ethanol. Ten microliters of sample extract were mixed with 200 µL of DPPH solution in a 96-well plate and incubated in the dark for 30 minutes at room temperature. Absorbance was measured at 514 nm, and antioxidant capacity was expressed as micromoles of Trolox equivalents per gram dry matter (µmol TE/g DM).

2.6. Economic

A production cost analysis was conducted based on actual expenses from pilot-scale processing of 1,500 kg of grade-out cape gooseberry at the Mae Hae Royal Project Development Center. Costs were categorized into five main components: raw materials, pretreatment, drying, labor, and packaging & storage. Calculations were based on direct operating costs, excluding depreciation. The unit cost per kilogram of dried product was determined by dividing the total cost by the net dried weight. This evaluation, based on methods from Santana et al. [

18] and Pise [

19], aimed to assess the economic feasibility of applying this value-added process in small-scale highland agricultural systems.

2.7. Statistical Analysis

A completely randomized design (CRD) with two factors—pretreatment (with or without mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment) and drying temperature (50, 60, and 70 °C)—was used, with three replications. Data were analyzed by two-way ANOVA, and differences among means were compared using Tukey’s HSD at p < 0.05. Analyses were conducted using Statistical analyses were performed using OriginPro 8.0 (OriginLab Corporation, Northampton, MA, USA) and SPSS Statistics 20.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA) under a licensed agreement with Maejo University. Results are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (SD).

3. Results

3.1. Efficacy of Hydrostatic Osmotic Pretreatment

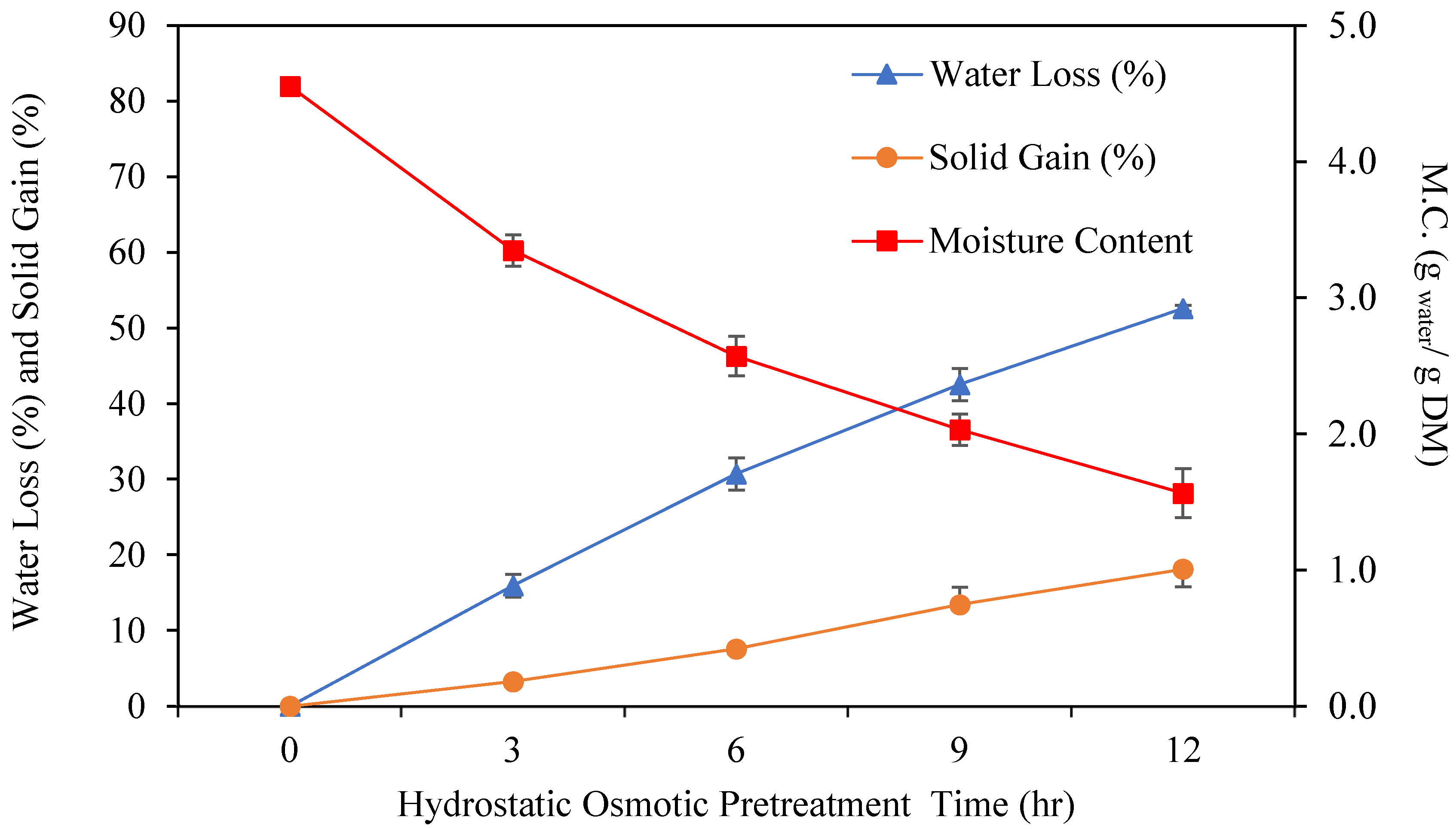

Experimental results presented in

Figure 4 indicate considerable changes in the parameters of Water Loss (WL), Solid Gain (SG), and Moisture Content (MC) in cape gooseberry samples undergoing osmotic pretreatment under mild hydrostatic pressure (0.5 bar). WL increased gradually from 0% to 52.61% during the period of 12 hours, whereas SG increased from 0% to 18.12%, and MC reduced from 4.56 g/g DM to 1.56 g/g DM. These are indicative of improved efficiency of mass transfer under the conditions of applied pressures. In the present work, the osmotic solution was initially at a concentration of 55 °Brix, in the constituencies of which predominance of sugar solids was present in the solution. Post the osmotic treatment under mild hydrostatic pressure, the osmotic solution concentration was found to decrease to 27 °Brix, which shows a high rate of water transfer from the fruit to the solution and accompanying migration of the solved solids to the interior of the tissues. Similar studies of osmotic treatment of fruit by using a concentrate solution have also reported the same results [

20]. One of the primary reasons of this phenomenon is increased mass transfer, wherein the external pressure facilitates the flow of water out and diffusion of the solute inwardly. Mild pressure lowers the boundary layer of the fruit surface toward the osmotic solution, hence diffusing at faster levels [

21]. Increased transfer is further supplemented by the rise in the chemical potential gradient in the direction of the tissue and the surrounding material [

22].

In addition, the phenomenon of tissue deformation is also significant. Plant tissues, being matrices of cellulose, pectin, and other polysaccharides, undergo transient deformation under applied pressure. Such deformation opens up the pore size and develops microchannels, thereby enhancing mass exchange. Elasticity and hydraulic permeability of plant material subjected to the same stress can play a crucial role in affecting water removal and the uptake of solution. Thermodynamically, the mass transfer happening, in this context, aligns with Le Chatelier’s Principle, whereby a system subjected to external perturbation will tend to react in a way that minimizes the disturbance occurring in it. In this context, the increase in external pressure causes the flow of water from the interior of the fruit towards the osmotic medium, thereby minimizing in-ternal hydrostatic pressure. Such a process also causes the increase in the density and firmness of the tissues, and this helps in the enhancement of structural stability during subsequent drying processes [

23]. Concomitant increases in WL and SG coupled with the decrease in solution concentration of 55 to 27 °Brix prove correlation of a robust bidirectional mass transfer. Such a correlation supports the reinforcement of the tissues, shrinking, and enhancing firmness, thereby enhancing the quality of the fruit upon drying. The study of mild osmotic pretreatment by the hydrostatic pressure illustrates noteworthy improvements in the nutritional and physico-chemical quality of dried fruit products prior to hot drying. This technique enhances the removal of water and nutrient retentivity, evidenced by the work of Yulni et al. [

24] and Nudar et al. [

25]. The interaction of osmotic drying and drying kinetics by the pretreatments can optimize the quality of the final product [

26]. Further, the analyses validate enhanced consistency and flavor profiles, corroborating the studies of the combined drying techniques [

27]. These developments place mild hydrostatic pressure at the center of maximizing the productivity of dried fruits [

28].

Figure 5.

Hydrostatic Pressure (P = 0.5 bar) Osmotic Pretreatment Procedure, (a) Photograph of Grade-Out cape gooseberry Fresh Fruit; (b) Photograph of cape gooseberry after a 12-hour hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment.

Figure 5.

Hydrostatic Pressure (P = 0.5 bar) Osmotic Pretreatment Procedure, (a) Photograph of Grade-Out cape gooseberry Fresh Fruit; (b) Photograph of cape gooseberry after a 12-hour hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment.

3.2. Characteristics of Drying Process

In this study, the drying characteristics of cape gooseberry subjected to mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment were compared with untreated fresh samples using a rotary tray dryer. The drying system operates by generating hot air through the combustion of liquefied petroleum gas (LPG) and circulating air within the drying chamber using electric power. The integration of these mechanisms results in low energy consumption and a simple operational design, making the rotary tray dryer an appropriate and farmer-friendly technology.

Assawarachan, R. Field Report on the Application of Rotary Tray Dryer Technology in Royal Project Postharvest Centers (2010–2023). Maejo University and Royal Project Foundation, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2024. This technology has gained widespread acceptance among Royal Project agricultural producers, with over 30 units installed and actively operating across various centers during the past 13 years [

6,

33].

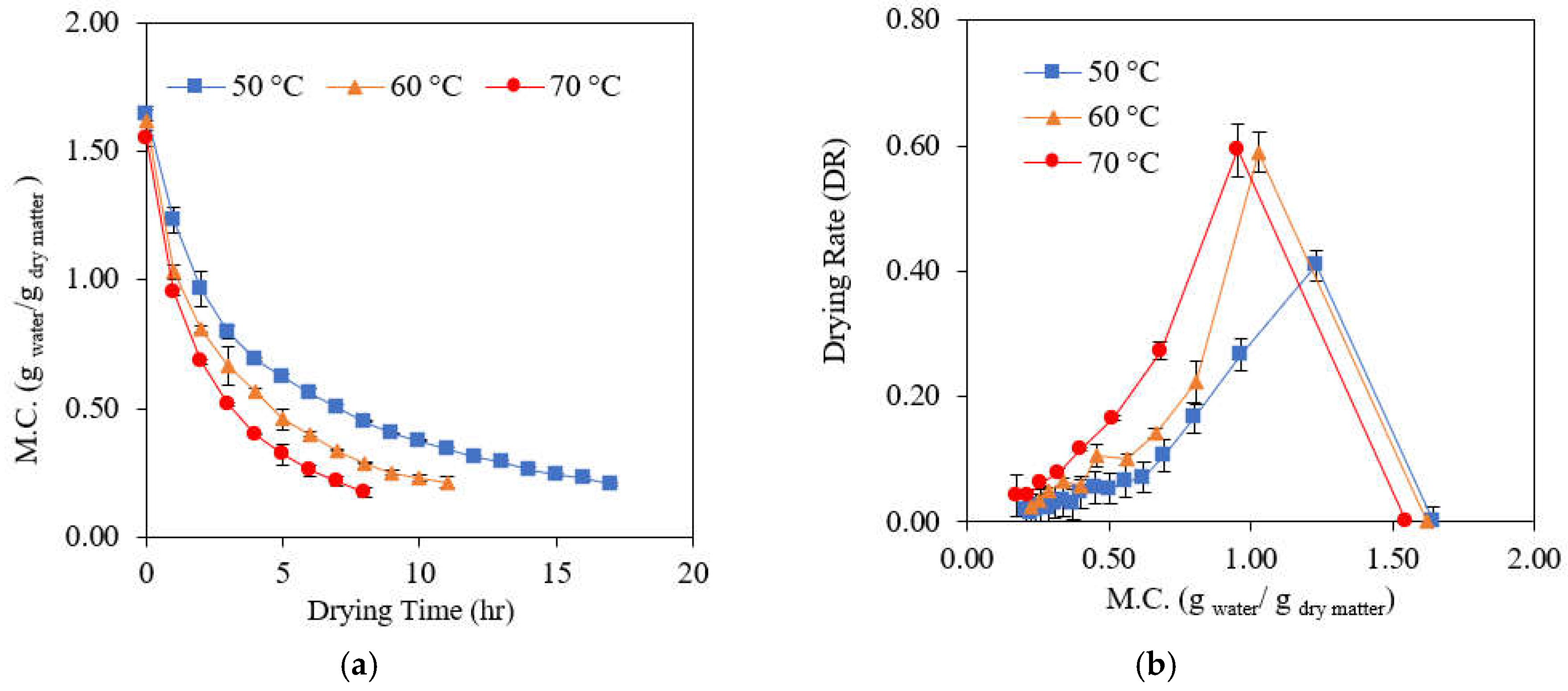

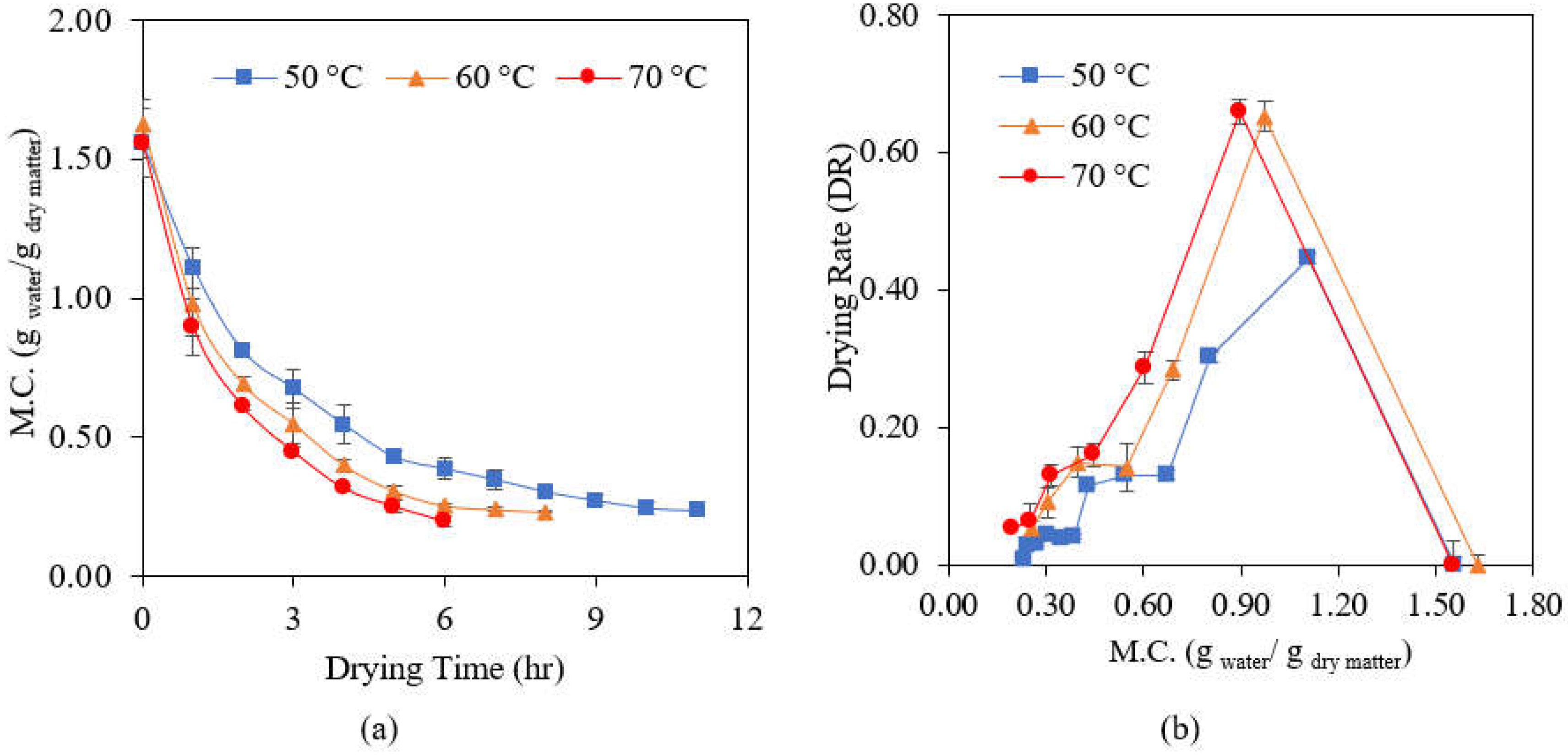

Cape gooseberry samples pretreated with mild hydrostatic osmotic dehydration at a pressure of 0.5 bar exhibited initial moisture contents ranging from 1.6287 ± 0.0883 to 1.5564 ± 0.1239 g water/g dry matter (DM). Subsequent hot-air drying at temperatures of 50, 60, and 70 °C effectively reduced the moisture content to between 0.2348 ± 0.0215 and 0.1962 ± 0.0189 g water/g DM, requiring 11, 8, and 6 hours, respectively. In contrast, untreated fresh samples dried at the same temperatures exhibited moisture contents ranging from 0.1757 ± 0.0188 to 0.2125 ± 0.0061 g water/g DM, with significantly longer drying times of 17, 11, and 8 hours, respectively. The comparative analysis (

Figure 6) clearly demonstrates that mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment significantly reduces the drying time by 35.29%, 27.27%, and 25.00% at 50, 60, and 70 °C, respectively.

The moisture content–drying rate relationship indicates a typical falling-rate period under all drying conditions, with no constant-rate period observed (

Figure 7). This finding confirms that moisture removal is predominantly governed by internal diffusion mechanisms rather than surface evaporation. The absence of a constant-rate period can be attributed to physicochemical changes in the tissue structure induced by osmotic pretreatment. During immersion in the concentrated sugar solution, intracellular water is withdrawn, while sucrose and glucose diffuse into the tissue matrix. These solutes contribute to the formation of a semi-permeable film on the fruit surface, primarily through hydrogen bonding with cell wall components such as pectin and cellulose. This surface layer functions as a diffusional barrier, limiting water vapor flux and increasing the viscosity of the boundary layer due to partial sugar crystallization [

27].

Although higher drying temperatures, particularly at 70 °C, facilitate faster initial moisture removal due to increased vapor pressure gradients, the drying process remains entirely within the falling-rate regime. These results support the conclusion that moisture migration is governed by internal mass transfer resistance, further influenced by partial cell collapse and the presence of a sugar-rich barrier layer, both of which significantly impede water evaporation [

28]. The drying kinetics lack a constant-rate period. This implies that internal concentration gradients influence drying more than external parameters like temperature or airflow [

29]. Moreover, the accumulation of sugars within the tissue matrix not only contributes to the organoleptic qualities of the final dried cape gooseberry such as improved texture and sweetness but also enhances structural integrity and moisture retention. A comprehensive understanding of these mechanisms is crucial for optimizing drying processes and improving both the quality and shelf life of dehydrated fruit products, underscoring the importance of continued research in this field.

3.3. Temperature Affects Changes in Optical Properties

The optical properties (L*, a*, b*, and ΔE) of grade-out cape gooseberry were significantly influenced by both hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment and drying temperature (p < 0.05), as shown in

Table 1. Fresh fruits exhibited high lightness (L* = 43.52 ± 2.71), redness (a* = 13.14 ± 1.55), and yellowness (b* = 34.43 ± 3.82), characteristic of fully matured fruits. Following a 12-hour hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment, a slight but noticeable reduction in L* and b* values was observed (L* = 39.59 ± 1.08), whereas a* values remained relatively stable, suggesting limited pigment leaching during solute infiltration. Drying temperature had a pronounced impact on color stability. Untreated samples dried at 70 °C exhibited severe color degradation, with L* decreasing to 9.65 ± 0.82 and ΔE increasing to 44.34 ± 1.46, likely due to pigment breakdown through Maillard reaction and caramelization [

30]. In contrast, pretreated samples demonstrated significantly better color retention across all drying temperatures, particularly at 60 °C, where ΔE was minimized to 13.54 ± 1.81.

Pigment degradation during drying is primarily driven by oxidative breakdown of carotenoids and anthocyanins, processes accelerated by elevated temperatures and oxygen exposure [

31]. Hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment mitigated these effects through multiple mechanisms: glycerin, functioning as a humectant, decreased water loss and oxygen permeability while forming a semi-permeable barrier on tissue surfaces [

33]; and ascorbic acid served as a powerful antioxidant, inhibiting the oxidative degradation of pigments and phenolic compounds [

34]. Furthermore, solute uptake during osmotic pretreatment formed a glassy matrix within the fruit structure, contributing to mechanical stabilization of cells and further limiting oxidative pigment degradation. Statistical analysis (ANOVA and Tukey’s HSD) confirmed that pretreated samples exhibited significantly lower ΔE and higher L* values than untreated ones (p < 0.05). These findings underscore the synergistic role of hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment in preserving optical properties during thermal drying.

3.4. Physicochemical Properties of Cape Gooseberry as Affected by Drying Temperature

3.4.1 Impact of Mild Hydrostatic Osmotic Pretreatment

The physicochemical properties of cape gooseberry were assessed before and after mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment. Parameters analyzed included vitamin C content, total phenolic content (TPC), and antioxidant activity, evaluated by ABTS and DPPH assays (

Table 2). The vitamin C content in fresh (untreated) and pretreated samples was 26.93 ± 3.41 and 34.92 ± 2.48 mg/100 g fresh weight (FW), respectively, as determined by the DCPIP titration method. These values are consistent with earlier reports by Valente et al. [

35] and Avendaño, et al. [

36], who found levels of 33.1 ± 0.4 and 29.49 ± 1.39 mg/100 g FW, respectively. The significant increase in the treated group suggests that the pretreatment protected or enhanced ascorbic acid. This effect may result from multiple mechanisms, including: (i) suppression of oxidative enzymes like ascorbate oxidase under reduced water activity; (ii) decreased oxygen permeability due to the infiltration of solutes such as sucrose, glycerin, and ascorbic acid; and (iii) formation of an osmotic barrier that limits oxidation and thermal degradation. Additionally, the mild hydrostatic conditions may induce cellular stress responses, promoting the biosynthesis or mobilization of endogenous antioxidants [

22,

23].

For total phenolic content (TPC), the fresh and treated fruits had similar values of 49.97±1.38 and 50.43±2.95 mg GAE/100 g FW, respectively. Although not statistically significant, this small increase suggests that phenolic compounds remained stable. The mild pretreatment may prevent degradation while improving extractability. Solute infiltration and slight structural loosening may enhance phenolic availability without triggering oxidation. Because many phenolics are bound within the cell wall, mild pressure may promote their release without damaging the cellular matrix.

Antioxidant capacity, based on ABTS and DPPH assays, slightly declined after pretreatment. ABTS activity decreased from 24.73 ± 2.11 to 22.21 ± 1.93 µmol TE/g FW. Similarly, DPPH activity dropped from 23.81 ± 1.35 to 21.27 ± 0.42 µmol TE/g FW. These reductions may reflect structural alterations in antioxidant compounds or dilution effects caused by solute movement. Despite the modest decline, antioxidant potential remained considerable in treated samples. Overall, mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment enhanced vitamin C retention and maintained phenolic stability in cape gooseberry. Although a slight reduction in antioxidant activity was observed, the results support the use of this technique as a pre-drying strategy to preserve nutritional quality in minimally processed fruit products.

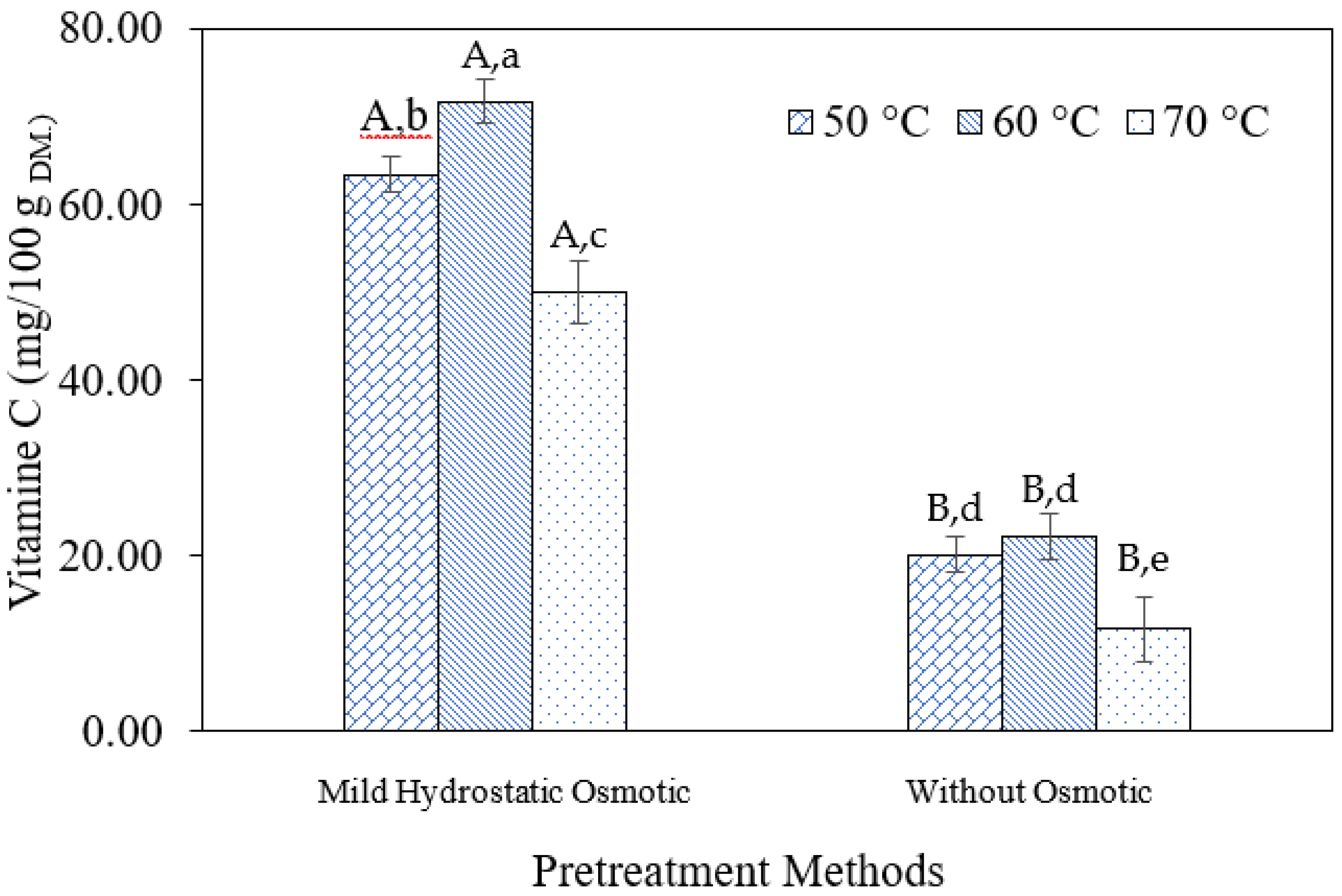

3.4.2. Impact of Drying Temperature

The effect of mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment was evaluated in comparison to untreated samples. Both groups were subjected to moisture reduction using a rotary tray dryer at 50, 60, and 70 °C. The final moisture content of the dried samples ranged from 0.2348 ± 0.0215 to 0.1962 ± 0.0189 g water/g dry matter (DM). Post-drying, physicochemical analyses were conducted to determine vitamin C content, total phenolic content (TPC), and antioxidant activity using ABTS and DPPH assays. Due to substantial differences in moisture content, direct comparison between fresh and dried samples was deemed inappropriate. Fresh cape gooseberry exhibited a moisture content of 1.5794 ± 0.8356 g water/g DM, whereas dried samples had significantly lower values. To enable accurate comparison, vitamin C values were recalculated on a dry matter basis under the assumption of no nutrient loss. Based on this calculation, pretreated samples retained 90.07 ± 0.0332 mg/100 g DM (equivalent to 34.92 ± 1.48 mg/100 g FW), while the untreated group retained 69.45 ± 0.1057 mg/100 g DM (26.93 ± 2.41 mg/100 g FW). Experimental results revealed that pretreated samples retained vitamin C concentrations of 63.41 ± 2.01, 71.77 ± 2.57, and 50.07 ± 3.60 mg/100 g DM after drying at 50, 60, and 70 °C, respectively. These values correspond to losses of 29.59%, 20.38%, and 44.42%. In contrast, untreated samples retained only 20.08 ± 1.17, 22.13 ± 1.56, and 11.63 ± 1.46 mg/100 g DM, representing losses of 71.08%, 68.13%, and 83.25%, respectively. These findings confirm that osmotic pretreatment significantly improves vitamin C retention, with optimal preservation observed at 60 °C. This outcome aligns with Yulni et al. [

24], who suggested that osmotic pretreatment enhances nutrient stability through structural cell modifications. Moreover, drying temperature is a critical factor influencing degradation kinetics. The inclusion of osmotic agents has been shown to stabilize bioactive compounds and improve storage longevity [

37]. This integrated strategy is supported by Nudar et al [

25], who emphasized the synergy between pretreatment and drying parameters.

The osmotic solution containing ascorbic acid, CaCl₂, and glycerol significantly improved vitamin C retention. Ascorbic acid acts as an antioxidant and enzyme inhibitor. Calcium ions stabilize membranes by cross-linking pectin. Glycerol helps form a semi-permeable matrix, reducing moisture and nutrient loss [

38]. Calcium ions contribute to membrane stabilization via pectin cross-linking, while glycerol supports the formation of a semi-permeable matrix, limiting moisture and nutrient loss. Thus, optimized osmotic dehydration is instrumental in preserving both nutritional and sensory quality in dried fruit products [

39].

Figure 8 illustrates the comparative vitamin C content of cape gooseberry treated with mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment versus untreated samples, across drying temperatures of 50, 60, and 70 °C. The results clearly demonstrate superior vitamin C retention in pretreated samples, particularly at 60 °C.

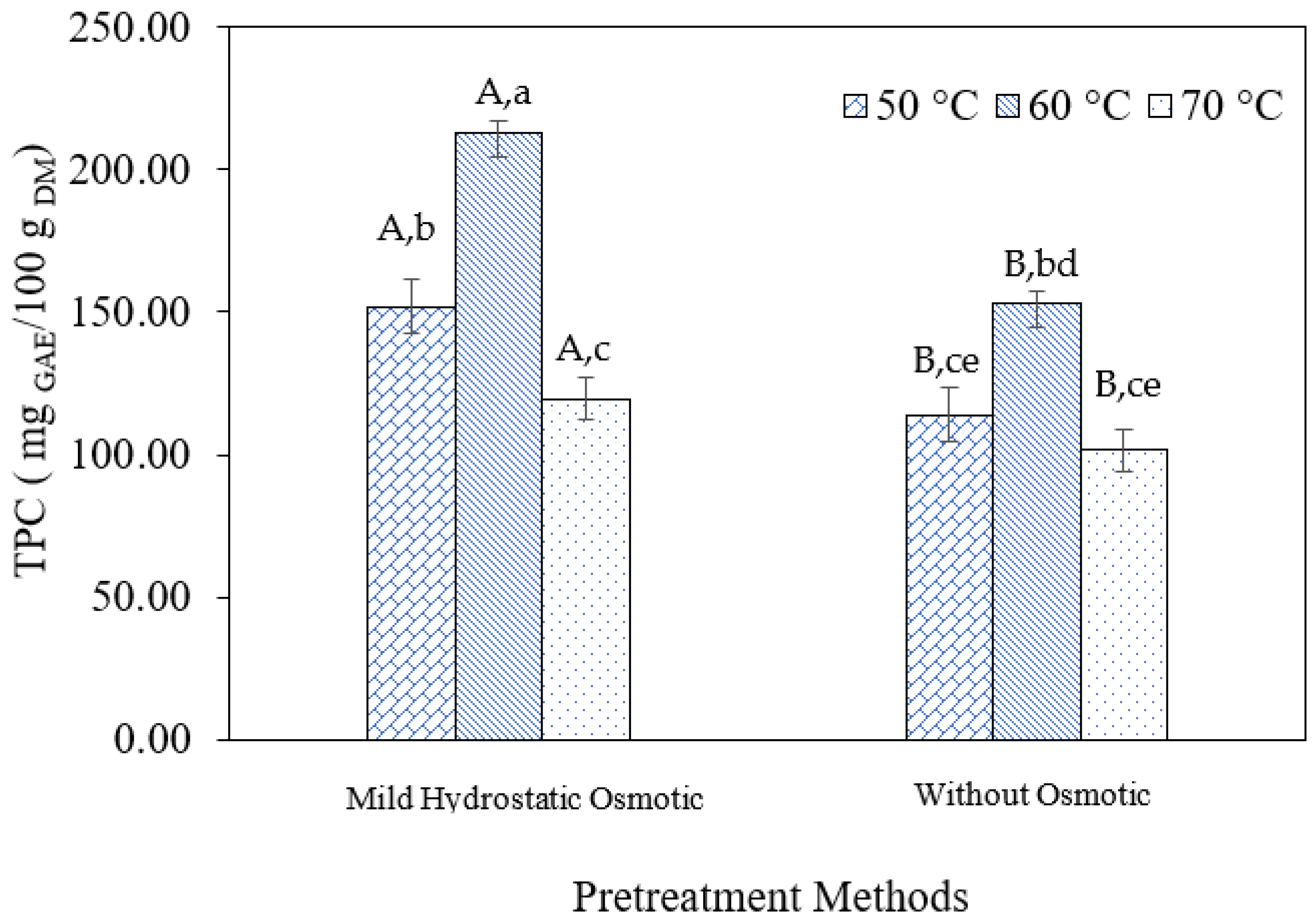

The total phenolic content (TPC) in fresh and pretreated samples ranged from 49.97 ± 1.38 to 50.43 ± 2.95 mg GAE/100 g FW, showing no significant difference. This consistency likely reflects the naturally high phenolic content in both the peel and pulp, including phenolic acids and flavonoids such as quercetin, myricetin, and kaempferol. These compounds possess potent antioxidant activity and exhibit greater thermal stability than ascorbic acid.

TPC values were calculated on a dry weight basis to facilitate accurate comparison under ideal conditions with no compound loss. Under these assumptions, TPC was estimated at 130.08 mg GAE/100 g DW. Pretreated samples showed significantly lower TPC losses 18.6 ± 1.2%, 20.1 ± 0.9%, and 21.4 ± 1.0% compared to 34.5 ± 1.7%, 36.0 ± 1.5%, and 37.2 ± 1.8% in untreated samples. One-way ANOVA confirmed the significant effect of pretreatment on TPC retention (p < 0.01), with Tukey’s HSD test revealing lower losses in all pretreated groups compared to the control (p < 0.05).

Pretreatment effectively enhanced TPC retention across drying temperatures. At 50°C, moderate losses were observed due to extended oxygen exposure. At 70°C, however, degradation increased sharply, likely due to multiple factors including the Maillard reaction, thermal degradation, enzymatic browning, and volatilization. These results align with findings by Li et al. [

40], who reported similar patterns of phenolic compound degradation in plant materials at elevated temperatures. Overall, pretreatment combined with drying at 60°C yielded the best outcome for phenolic preservation, as shown in

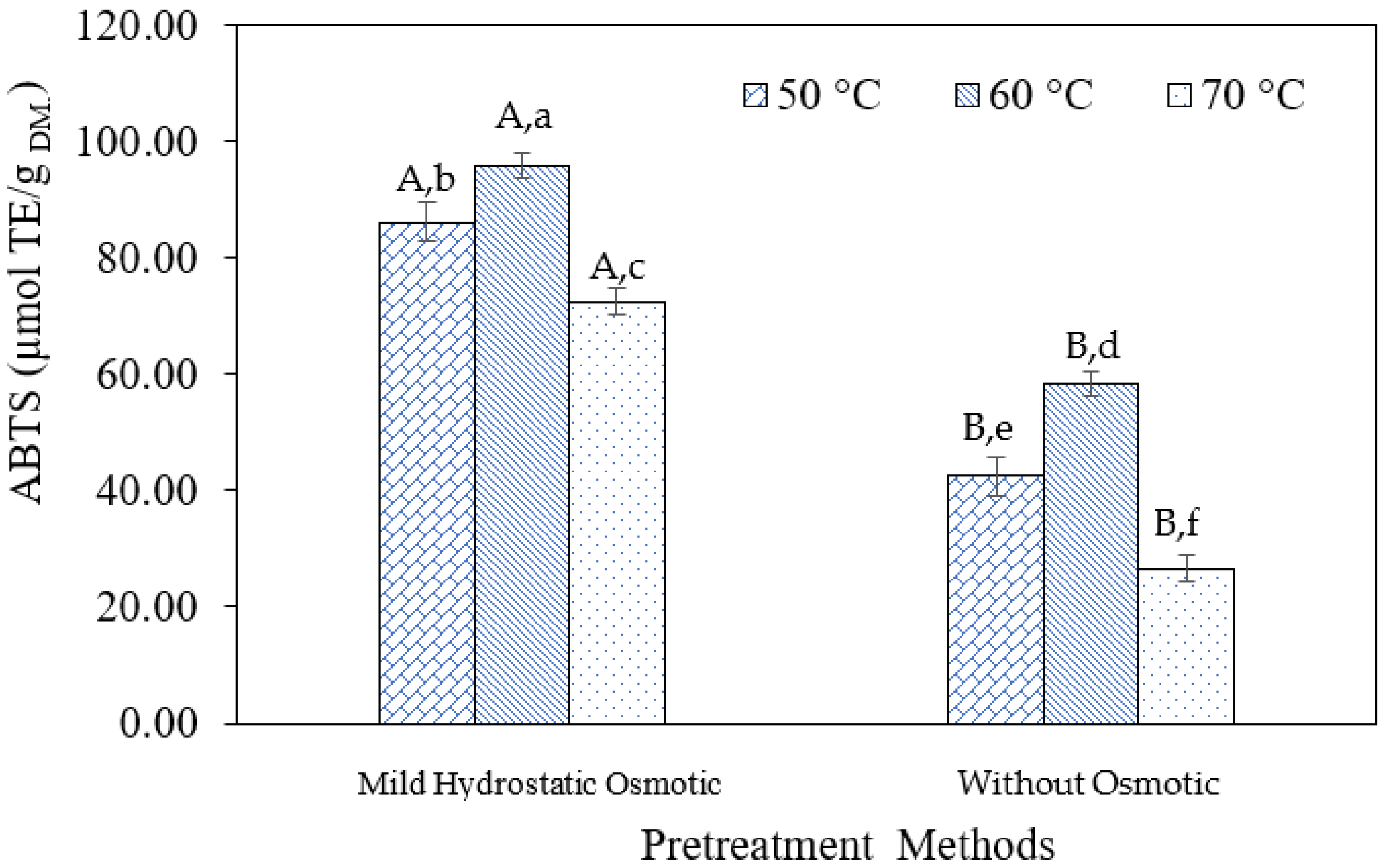

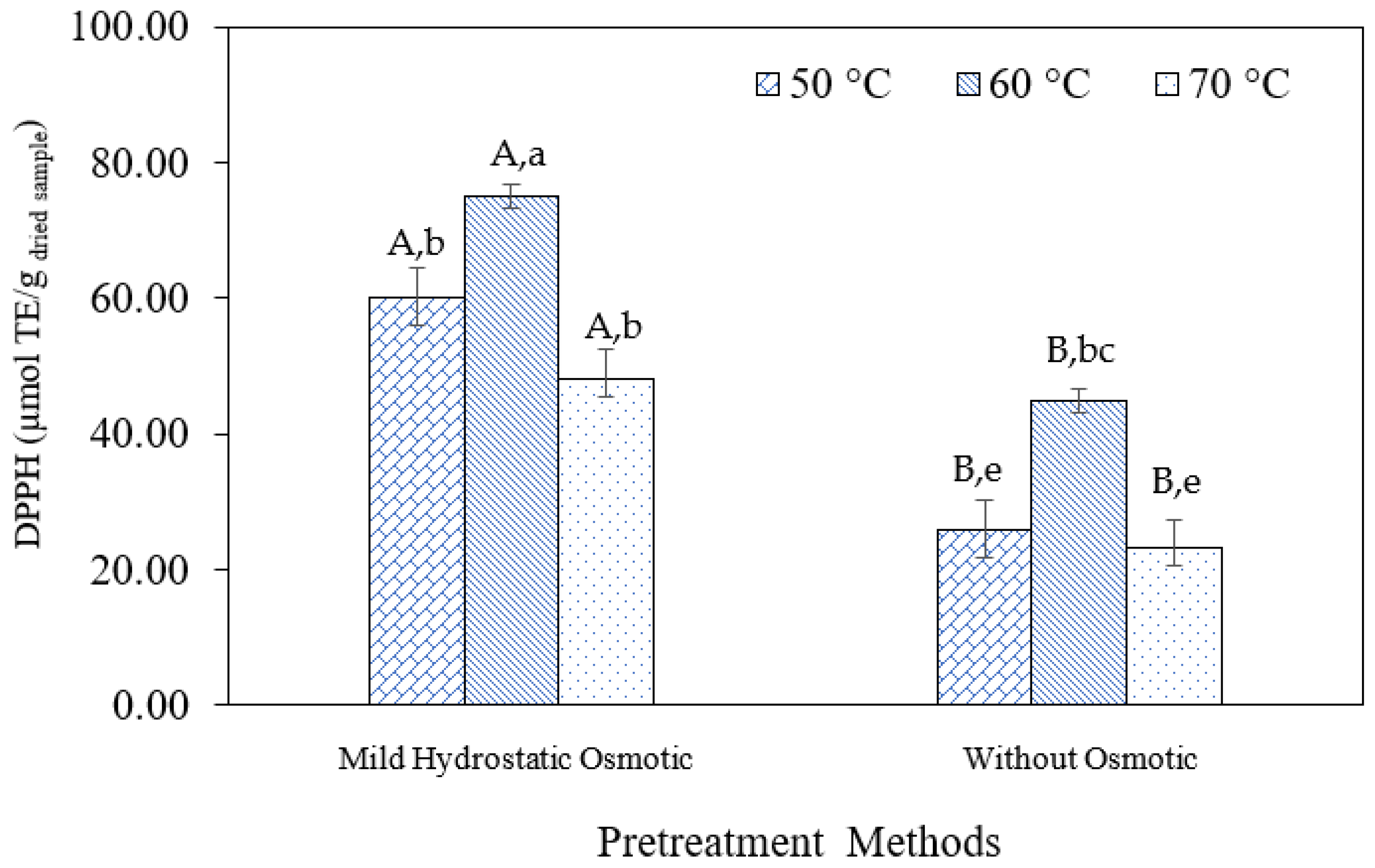

Figure 9. The influence of drying temperatures on antioxidant activity in the cape gooseberry has attracted attention, particularly through tests such as ABTS and DPPH. Variable temperatures can significantly affect the retention of bioactive compounds, which leads to changes in antioxidant properties [

41]. Optimal conditions can improve the stability of antioxidants, while excessive heat can degrade these compounds [

42]. Studies suggest that lyophilization can preserve more antioxidants compared to traditional drying methods [

43]. The role of temperature and storage in antioxidant activity remains critical to maximize health benefits.

Figure 9.

The comparative analysis of TPC content in cape gooseberry was affected by pre-treatment with mild osmotic hydrostatic methods, as well as drying temperatures of 50, 60, and 70 °C, respectively. Lowercase letters (a–d) show significant differences within pretreatment groups; uppercase letters (A–B) show differences between groups at each drying temperature (p < 0.05, Tukey's HSD).

Figure 9.

The comparative analysis of TPC content in cape gooseberry was affected by pre-treatment with mild osmotic hydrostatic methods, as well as drying temperatures of 50, 60, and 70 °C, respectively. Lowercase letters (a–d) show significant differences within pretreatment groups; uppercase letters (A–B) show differences between groups at each drying temperature (p < 0.05, Tukey's HSD).

Figure 10.

The comparative analysis of antioxidant capacity (ABTS) in cape gooseberry was affected by pre-treatment with mild osmotic hydrostatic methods, as well as drying temperatures of 50, 60, and 70 °C, respectively. Lowercase letters (a–d) show significant differences within pretreatment groups; uppercase letters (A–B) show differences between groups at each drying temperature (p < 0.05, Tukey's HSD).

Figure 10.

The comparative analysis of antioxidant capacity (ABTS) in cape gooseberry was affected by pre-treatment with mild osmotic hydrostatic methods, as well as drying temperatures of 50, 60, and 70 °C, respectively. Lowercase letters (a–d) show significant differences within pretreatment groups; uppercase letters (A–B) show differences between groups at each drying temperature (p < 0.05, Tukey's HSD).

Figure 11.

The comparative analysis of antioxidant capacity (DPPH) in cape gooseberry was affected by pre-treatment with mild osmotic hydrostatic methods, as well as drying temperatures of 50, 60, and 70 °C, respectively. Lowercase letters (a–d) show significant differences within pretreatment groups; uppercase letters (A–B) show differences between groups at each drying temperature (p < 0.05, Tukey's HSD).

Figure 11.

The comparative analysis of antioxidant capacity (DPPH) in cape gooseberry was affected by pre-treatment with mild osmotic hydrostatic methods, as well as drying temperatures of 50, 60, and 70 °C, respectively. Lowercase letters (a–d) show significant differences within pretreatment groups; uppercase letters (A–B) show differences between groups at each drying temperature (p < 0.05, Tukey's HSD).

3.5. Analysis of Drying Costs

The study demonstrated that the combination of mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment and rotary tray drying is technically feasible and economically viable for processing grade-out cape gooseberry (in highland agricultural settings. The experiment was conducted under real operating conditions at the Mae Hae Royal Project Development Center, Chiang Mai Province, Thailand, using 1,500 kg of grade-out fruit as input. After sorting and trimming, 1,260 kg of usable fruit remained, and a total of 220 kg of dried product with 0.1962 ± 0.0189 to 0.2348 ± 0.0215 and g water/g DM was obtained after 20 processing cycles. The application of mild hydrostatic pressure during osmotic dehydration enhanced mass transfer and contributed to shorter drying times, thereby improving overall energy efficiency. The rotary tray dryer, developed through local appropriate technology initiatives, proved suitable for decentralized operations due to its consistent heat distribution, low maintenance requirements, and ease of use. The process relied on five laborers per batch (two for pretreatment and three for drying and packaging), all compensated at USD 1.00 per hour.

The total processing cost was calculated at USD 1,510.50, or USD 6.93 per kilogram of final product. This included raw material, labor, electricity, fuel gas, equipment maintenance, and depreciation. The depreciation cost of the dryer was estimated at USD 148 for the trial, based on 0.1% per cycle. With an estimated wholesale price of USD 12 per kilogram, the gross margin was approximately USD 5.07 per kilogram, indicating strong potential for community-scale value addition. The system employed in this study offers a more affordable and accessible alternative, balancing cost-effectiveness with product quality and local adaptability.

Beyond technical and economic performance, the processing approach also contributes to sustainability goals. Utilizing grade-out fruit reduces postharvest losses and supports food waste valorization, aligning with Sustainable Development Goal 12: Responsible Consumption and Production. The increased energy efficiency from osmotic pretreatment also supports environmental resource conservation. Moreover, the adoption of locally developed drying technology empowers smallholder farmers by improving access to processing solutions, supporting local livelihoods, and fostering inclusive rural development [

44]. Despite its promising outcomes, this study does not include costs related to packaging, distribution, or product certification. These factors should be addressed in future research to provide a more comprehensive understanding of the economic feasibility. Long-term assessments of system scalability, durability, and supply chain integration are also recommended to strengthen the applicability of this model for broader implementation in highland agriculture.

Table 3.

Cost components of processing grade-out cape gooseberry with mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment using rotary tray dryer.

Table 3.

Cost components of processing grade-out cape gooseberry with mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment using rotary tray dryer.

| Cost Category |

Value |

Estimated Unit Cost (USD) |

| Raw Materials |

|

|

| Grade-out cape gooseberry (1,500 kg) |

0.33 USD/kg |

495 |

| Osmotic solution |

|

|

| Sucrose (150 kg) |

1 USD/kg |

150 |

| Citric Acid (0.5 kg) |

10 USD/kg |

5 |

| Glycerin (30 kg) |

2 USD/kg |

60 |

| CaCl2 (0.5 kg) |

10 USD/kg |

5 |

| Potassium Metabisulfite (0.5 kg) |

15 USD/kg |

5 |

| Soft Water (1200 L) |

0.05 USD/L |

60 |

| Pretreatment Process |

|

|

| Heat energy (LPG = 15 kg ) |

15 USD |

15 |

| Electricity for air compressor (80 kW-hr) |

0.25 USD/ kW-hr |

20 |

| Equipment depreciation |

|

|

| Drying Process |

|

|

Electricity for rotary tray dryer

(Total = 350 kW-hr) |

0.25 USD/ kW-hr |

87.5 |

| Heat energy (LPG = 96 kg) |

80 USD |

80 |

| Maintenance & Cleaning (20 time) |

3 USD/times |

60 |

| Equipment depreciation (0.1% per times) |

7.35 USD |

148 |

| Labor Costs |

|

|

Labor for pretreatment

(20 time x2 person x 2 hr) |

1 USD/hr |

80 |

Labor for drying & Packaging

(20 time x3 person x 4 hr) |

1 USD/hr |

240 |

| Total Cost Components of Processing |

|

1,510.5 |

4. Discussion

This study, conducted under real-world conditions at the Mae Hae Royal Project Development Center in Chiang Mai, Thailand, demonstrates the feasibility of using appropriate technologies to valorize food waste, particularly in the context of smallholder farming. Mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment at 0.5 bar for 12 hours significantly reduced drying time by promoting water loss and solid gain, lowering initial moisture content before hot-air drying. The osmotic solution of sucrose, citric acid, and glycerin diffused into the fruit, inducing osmotic pressure and micro-pore formation, enhancing mass transfer and moisture migration during drying.

Drying at 60°C using a rotary tray dryer maintained superior color (CIE Lab*), retained bioactive compounds (vitamin C, phenolics, antioxidants), and suppressed non-enzymatic browning. Citric acid and glycerin in the osmotic solution inhibited pigment degradation and enhanced nutritional quality. Cost analysis from a 1,500 kg production trial confirmed economic viability, with a total cost of USD 6.93/kg and projected retail price of USD 15/kg, indicating favorable profit margins for highland farming systems. This supports transforming food waste into high-value products, aligning with the Royal Project Foundation's sustainability goals. Further research is recommended on textural/sensory properties, microbial safety, shelf-life, and comprehensive cost-benefit analysis to refine the product for broader commercial adoption under nationally recognized brands. Nonetheless, this study validates the technical feasibility and economic potential of mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment with rotary tray drying for valorizing grade-out cape gooseberry in highland agriculture.

5. Conclusions

This research validated the technical and economic feasibility of mild hydrostatic osmotic pretreatment followed by rotary tray drying for upgrading grade-out cape gooseberry in highland agriculture. Pretreatment at 0.5 bar for 12 hours enhanced mass transfer, reduced drying time by 35%, and maintained color (L*= 36.29±4.87, a* = 13.37±0.59, b* = 24.18±4.29, ΔE = 13.54 ±1.81), vitamin C (71.76 ± 2.57 mg/100 g), phenolics (202.9 ± 10.91 mg GAE/100 g), and antioxidants (ABTS: 95.87 ± 3.41 µmol TE/g, DPPH: 89.97 ± 1.27 µmol TE/g). A 1,500 kg production trial at the Mae Hae Royal Project Development Center yielded 220 kg of premium dried cape gooseberry at USD 6.93/kg cost and USD 15/kg projected retail price. Local farmers successfully implemented the process, demonstrating its suitability for smallholders. The findings support subgrade fruit utilization, commercial applications, and sustainable highland development, aligning with SDG 12. Efficient adoption by farmers shows the model's potential to improve livelihoods within the Royal Project Foundation's sustainable agriculture initiatives.

6. Patents

The rotary tray dryer employed in this study is a patented invention (patent no. 18896) developed as part of the "Drying Process Development of Chamomile, Chrysanthemum, and Herb for the Sa-Ngo Royal Project Development Center Phase 2" project (CRP6205012320), which received funding from the Agricultural Research Development Agency (Public Organization).

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rittichai Assawarachan; methodology, Rittichai Assawarachan; software, Rittichai Assawarachan; validation, Rittichai Assawarachan; formal analysis, Rittichai Assawarachan; investigation, Rittichai Assawarachan; resources, Rittichai Assawarachan; data curation, Rittichai Assawarachan; writing—original draft preparation, Rittichai Assawarachan; writing—review and editing, Rittichai Assawarachan; visualization, Rittichai Assawarachan; supervision, Rittichai Assawarachan; project administration, Rittichai Assawarachan; funding acquisition, Rittichai Assawarachan. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The article processing charge (APC) was supported by the Agricultural Research Development Agency (Public Organization), Thailand.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted under the projects “Amplification of Rotation Dryer for Processing Agricultural Products: A Case Study of the Development Royal Project (PRP6607031340)” and “Amplification of Rotation Dryer to Increase the Value of Agricultural Products Using the Royal Project Model: Case Study of the Lertor Royal Project Development Center (PRP6707031510),” funded by the Agricultural Research Development Agency (Public Organization), Thailand. The authors gratefully acknowledge the Mae Hae Royal Project Development Center, Chiang Mai Province, and the Promotion and Development Division of the Royal Project Foundation, Thailand, for providing raw materials and experimental facilities.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Muñoz, P.; Parra, F.; Simirgiotis, M.J.; Sepúlveda Chavera, G.F.; Parra, C. Chemical Characterization, Nutritional and Bioactive Properties of Physalis peruviana Fruit from High Areas of the Atacama Desert. Foods 2021, 10, 2699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monroy-Velandia, D.; Coy-Barrera, E. Effect of Salt Stress on Growth and Metabolite Profiles of Cape Gooseberry (Physalis peruviana L.) along Three Growth Stages. Molecules 2021, 26, 2756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez Racines, L.; Buitrago Vera, J.M. Export of Organic Cape Gooseberry (Physalis peruviana) as an Alternative Illicit Crop Substitution: Survey of Consumers in Namur, Belgium. Sustainability 2023, 15, 16604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhaktikul, K.; Aroonsrimorakot, S.; Laiphrakpam, M. Sustainable Low-Carbon Community Development: A Study Based on a Royal Project for Highland Community Development in Thailand. J. Community Dev. Res. (Humanit. Soc. Sci.) 2021, 14, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nosten, M. Rotational Farming by the Karen People and Its Role in Livelihood Adaptive Capacity and Biocultural Conservation: A Case Study of Upland Community Forestry in Thailand. Ph.D. Thesis, University of British Columbia, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Assawarachan, R. Rotary Tray Hot-Air Dryer with Two-Stage Temperature Control System. Thai Petty Patent 18896, 2020.

- Ahmed, M.; Hasan, M.; Islam, M.N. Effect of osmotic dehydration pretreatment on drying kinetics and quality characteristics of fruits and vegetables: A review. Journal of Food Processing and Preservation 2021, 45, e15434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, S.; Kumar, S.; Bera, M.B. Effect of pretreatments and drying methods on quality attributes of osmo-dried papaya cubes. Journal of Food Science and Technology 2019, 56, 1520–1528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroehnke, J.; Szadzińska, J.; Radziejewska-Kubzdela, E.; Biegańska-Marecik, R.; Musielak, G.; Mierzwa, D. Osmotic Dehydration and Convective Drying of Kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa)—The Influence of Ultrasound on Process Kinetics and Product Quality. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2021, 71, 105377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahamad, S.; Sagar, V.R.; Asrey, R.; Islam, S.; Tomar, B.S.; Vinod, B.R.; Kumar, A. Nutritional Retention and Browning Minimisation in Dehydrated Onion Slices through Potassium Metabisulphite and Sodium Chloride Pre-Treatments. Int. J. Food Sci. Technol. 2024, 59, 5794–5805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luechai, N.; Khamsuk, T.; Aramkhiphai, S.; Keadsak, P.; Lungjitang, N. Effect of Temperature on Quality Change of Drying Cape Gooseberry (Physalis peruviana Linn.). Bachelor's Project, Smart Farm Engineering and Agricultural Innovation Program, College of Renewable Energy, Maejo University, Chiang Mai, Thailand, 2025; p. 66.

- Bhat, T.A.; Rather, A.H.; Hussain, S.Z.; Naseer, B.; Qadri, T.; Nazir, N. Efficacy of Ascorbic Acid, Citric Acid, Ethylenediaminetetraacetic Acid, and 4-Hexylresorcinol as Inhibitors of Enzymatic Browning in Osmo-Dehydrated Fresh Cut Kiwis. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 4354–4370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Method 920.151: Solids (Total) in Fruits and Fruit Products. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 21st ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Torreggiani, D.; Bertolo, G. Osmotic Pre-Treatments in Fruit Processing: Chemical, Physical and Structural Effects. J. Food Eng. 2001, 49, 247–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AOAC International. Official Method 967.21: Ascorbic Acid in Vitamin Preparations and Juices. In Official Methods of Analysis of AOAC International, 21st ed.; AOAC International: Gaithersburg, MD, USA, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Osorio-Arias, J.; Delgado-Arias, S.; Cano, L.; Zapata, S.; Quintero, M.; Nuñez, H.; Ramírez, C.; Simpson, R.; Vega-Castro, O. Sustainable Management and Valorization of Spent Coffee Grounds through the Optimization of Thin Layer Hot Air-Drying Process. Waste Biomass Valorization 2019, 11, 5015–5026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ignat, I.; Volf, I.; Popa, V.I. A Critical Review of Methods for Characterisation of Polyphenolic Compounds in Fruits and Vegetables. Food Chem. 2011, 126, 1821–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santana, P.A.; de Carvalho Lopes, D.; Neto, A.J.S. Economic Analysis of Low-Temperature Grain Drying. Emirates Journal of Food and Agriculture 2019, 31, 930–936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pise, V.H. (2024). Techno-Economic Evaluation for Cost-Effective Drying of Different Fruit Products. In Dried Fruit Products (pp. 206–233). CRC Press.

- Goula, A.M.; Adamopoulos, K.G.; Chatzitakis, P.C.; Nikas, V.A. Prediction of lycopene degradation during a drying process of tomato pulp. J. Food Eng. 2006, 74, 37–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Noguera, J.; Oliveira, F.I.P.; Gallão, M.I.; Weller, C.L.; Rodrigues, S.; Fernandes, F.A.N. Ultrasound-Assisted Osmotic Dehydration of Strawberries: Effect of Pretreatment Time and Ultrasonic Frequency. Dry. Technol. 2010, 28, 294–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, J.; Le Maguer, M. Osmotic Dehydration of Foods: Mass Transfer and Modeling Aspects. Food Rev. Int. 2002, 18, 305–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowacka, M.; Tylewicz, U.; Laghi, L.; Dalla Rosa, M.; Witrowa-Rajchert, D. Effect of Ultrasound Treatment on the Water State in Kiwifruit during Osmotic Dehydration. Food Chem. 2014, 144, 18–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yulni, T.; Agusta, W.; Jayanegara, A.; Alfa, M.N.; Hartono, L.K.; Mariastuty, T.E.P.; Lintang, M.M.J. Unveiling the Influence of Osmotic Pretreatment on Dried Fruit Characteristics: A Meta-Analysis Approach. Prev. Nutr. Food Sci. 2024, 29, 178–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nudar, J.; Roy, M.; Ahmed, S. Combined osmotic pretreatment and hot air drying: Evaluation of drying kinetics and quality parameters of adajamir (Citrus assamensis). Heliyon 2023, 9, e19545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boateng, I.D. Thermal and Nonthermal Assisted Drying of Fruits and Vegetables: Underlying Principles and Role in Physicochemical Properties and Product Quality. Food Eng. Rev. 2023, 15, 113–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, A.L.D.; Pena, R.D.S. Combined Pulsed Vacuum Osmotic Dehydration and Convective Air-Drying Process of Jambolan Fruits. Foods 2023, 12, 1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jin, W.; Zhang, M.; Sun, Q.; Mujumdar, A.S.; Yu, D. Effects of Ultrasonic-Assisted Osmotic Pretreatment on Convective Air-Drying Assisted Radio Frequency Drying of Apple Slices. Dry. Technol. 2025, 43, 467–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osae, R.; Adjonu, R.; Apaliya, M.T.; Engmann, F.N.; Owusu-Ansah, P.; Fauzia, A.S.; Alolga, R.N. Freeze-Thawing and Osmotic Dehydration Pretreatments on Physicochemical Properties and Quality of Orange-Fleshed Sweet Potato Slice during Hot Air Drying. Food Chem. Adv. 2024, 5, 100843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, J.A., Abdel-Kader, A.Y., & Karel, M. (2006). Osmotic dehydration of fruits: Mass transfer and quality. In Handbook of Food Preservation (2nd ed., pp. 447–469). CRC Press.

- Mayor, L.; Sereno, A.M. Modelling Shrinkage during Convective Drying of Food Materials: A Review. J. Food Eng. 2004, 61, 373–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Norouzi, S.; Orsat, V.; Yeasmen, N.; Dumont, M.J. Osmotic Dehydration of Waxy Skinned Berries—A Review. Drying Technology 2024, 42, 1270–1294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leelapattana, W.; Assawarachan, R. Enhancing technology transfer and innovation for processing of dried yellow chrysanthemum (Chrysanthemum indicum) flowers: A case study of the Mae Wang Lao Community Enterprise Group, Chiang Rai Province. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2025, 3541701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huerta-Vera, K.; Flores-Andrade, E.; Contreras-Oliva, A.; Villegas-Monter, Á.; Chavez-Franco, S.; Arévalo-Galarza, M. Incorporation of Bioactive Compounds in Fruit and Vegetable Products through Osmotic Dehydration: A Review. Rev. Mex. Cienc. Agríc. 2023, 14, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valente, A.; Albuquerque, T.G.; Sanches-Silva, A.; Costa, H.S. Ascorbic Acid Content in Exotic Fruits: A Contribution to Produce Quality Data for Food Composition Databases. Food Res. Int. 2011, 44, 2237–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avendaño, W.A.; Muñoz, H.F.; Leal, L.J.; Deaquiz, Y.A.; Castellanos, D.A. Physicochemical characterization of cape gooseberry (Physalis peruviana L.) fruits ecotype Colombia during preharvest development and growth. J. Food Sci. 2022, 87, 2583–2598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mousa, E.A.; Ali, M.I.K.; Hassan, N.A.; Elbassiony, K.R. Effect of Osmo-Dehydration and Gamma Irradiation on Nutritional Characteristics of Dried Fruit. Egypt. J. Food Sci. 2024, 52, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haneef, N.; Hanif, N.; Hanif, T.; Raghavan, V.; Garièpy, Y.; Wang, J. Food fortification potential of osmotic dehydration and the impact of osmo-combined techniques on bioactive component saturation in fruits and vegetables. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2024, 27, e2023028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladika, G.; Tsiaka, T.; Stavropoulou, N.A.; Strati, I.F.; Sinanoglou, V.J. Enhancing the Nutritional Value and Preservation Quality of Strawberries through an Optimized Osmotic Dehydration Process. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 9211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Shen, P.; Liu, W.; Liu, C.; Liang, R.; Yan, N.; Chen, J. Major Polyphenolics in Pineapple Peels and Their Antioxidant Interactions. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2018, 121, 238–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agudelo-Sánchez, S.; Mosquera-Palacios, Y.; David-Úsuga, D.; Cartagena-Montoya, S.; Duarte-Correa, Y. Effect of processing methods on the postharvest quality of cape gooseberry (Physalis peruviana L.). Horticulturae 2023, 9, 1158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gallon Bedoya, M.; Cortes Rodriguez, M.; Gil, J.H. Physicochemical stability of colloidal systems using the cape gooseberry, strawberry, and blackberry for spray drying. J. Food Process. Preserv. 2020, 44, e14705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinaldi, B.J.D.; Montanher, P.F.; Johann, G. Brewing of craft beer enriched with freeze-dried cape gooseberry: a promising source of antioxidants. Braz. J. Food Technol. 2022, 25, e2022019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pretty, J. Agricultural sustainability: Concepts, principles and evidence. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. B Biol. Sci. 2008, 363, 447–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).