Submitted:

22 April 2025

Posted:

06 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Materials and Methods

Cell Culture and Treatment

Clonogenic Assay

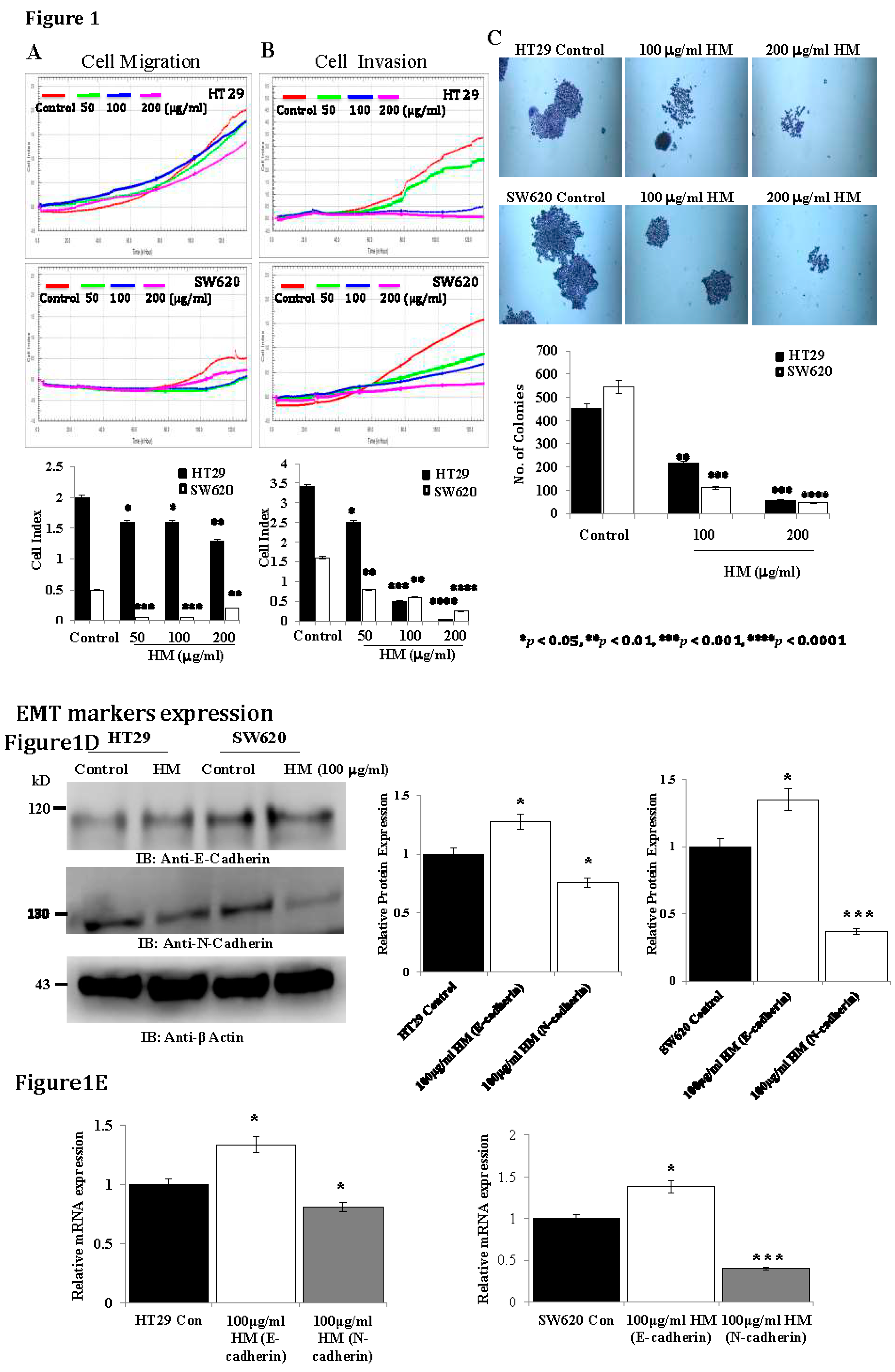

Cell Migration and Invasion Assays Using xCELLigence Real-Time Cell Analysis

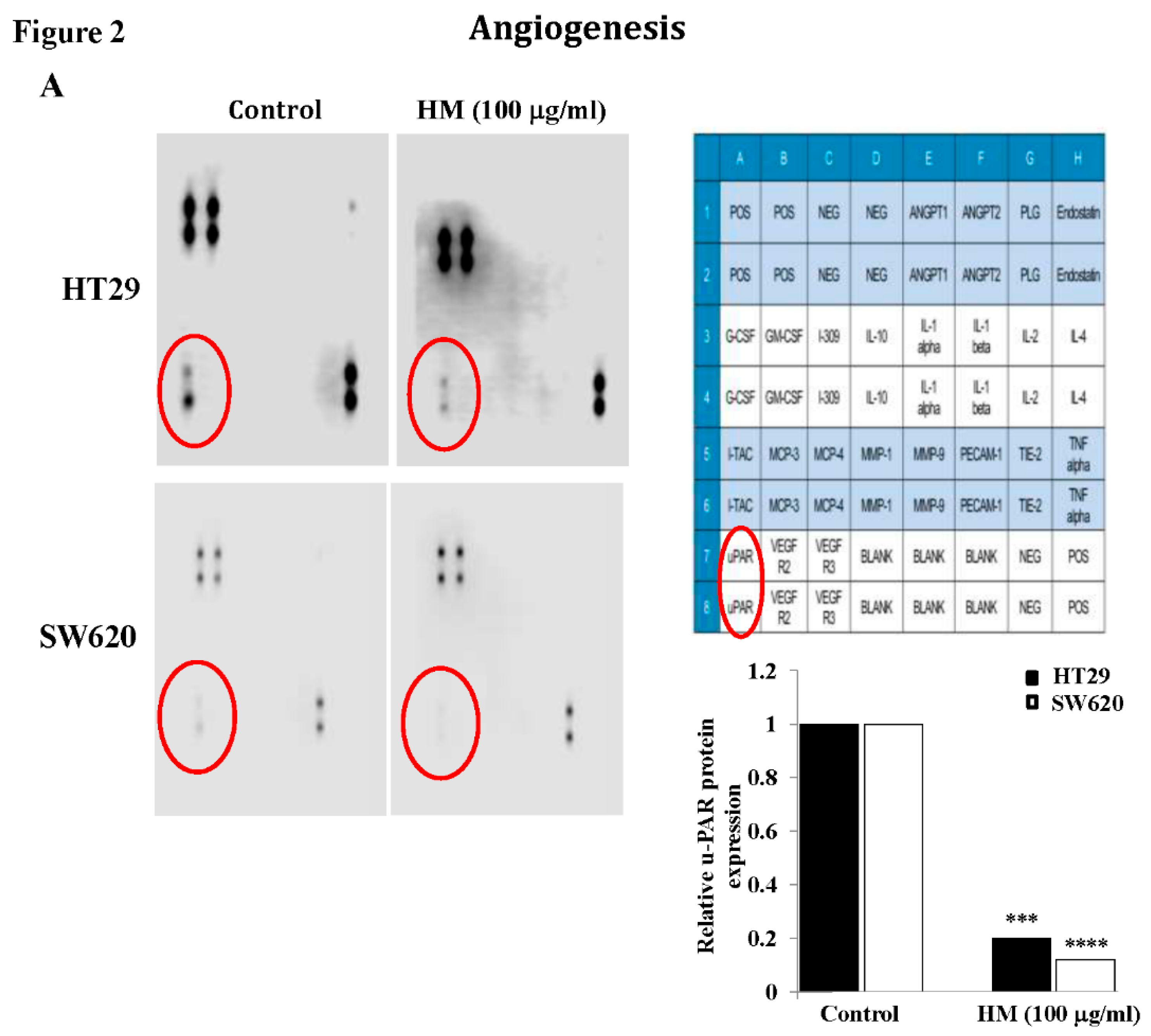

Angiogenesis-Related Protein Array

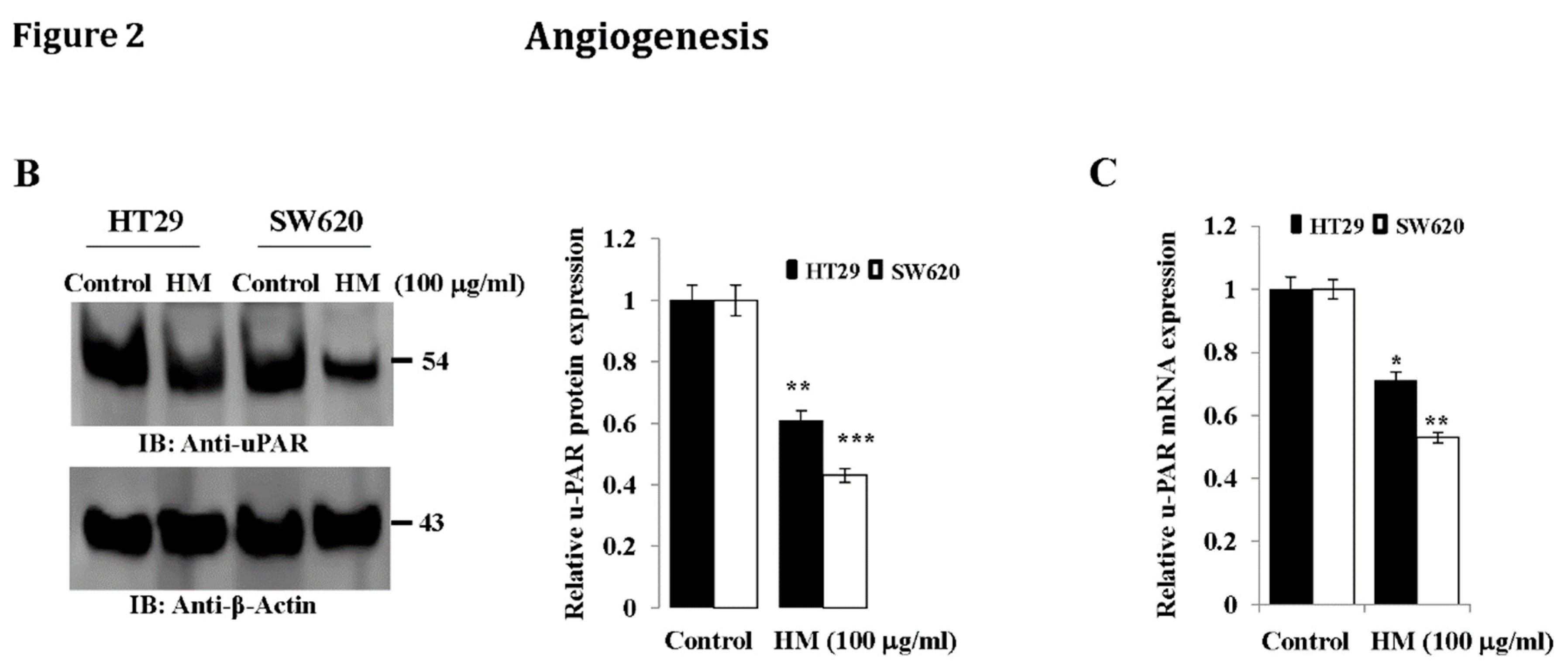

Whole Cell Lysates and Western Blotting

RNA Extraction and Reverse-Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction (RT-PCR)

Statistical Analysis

Results

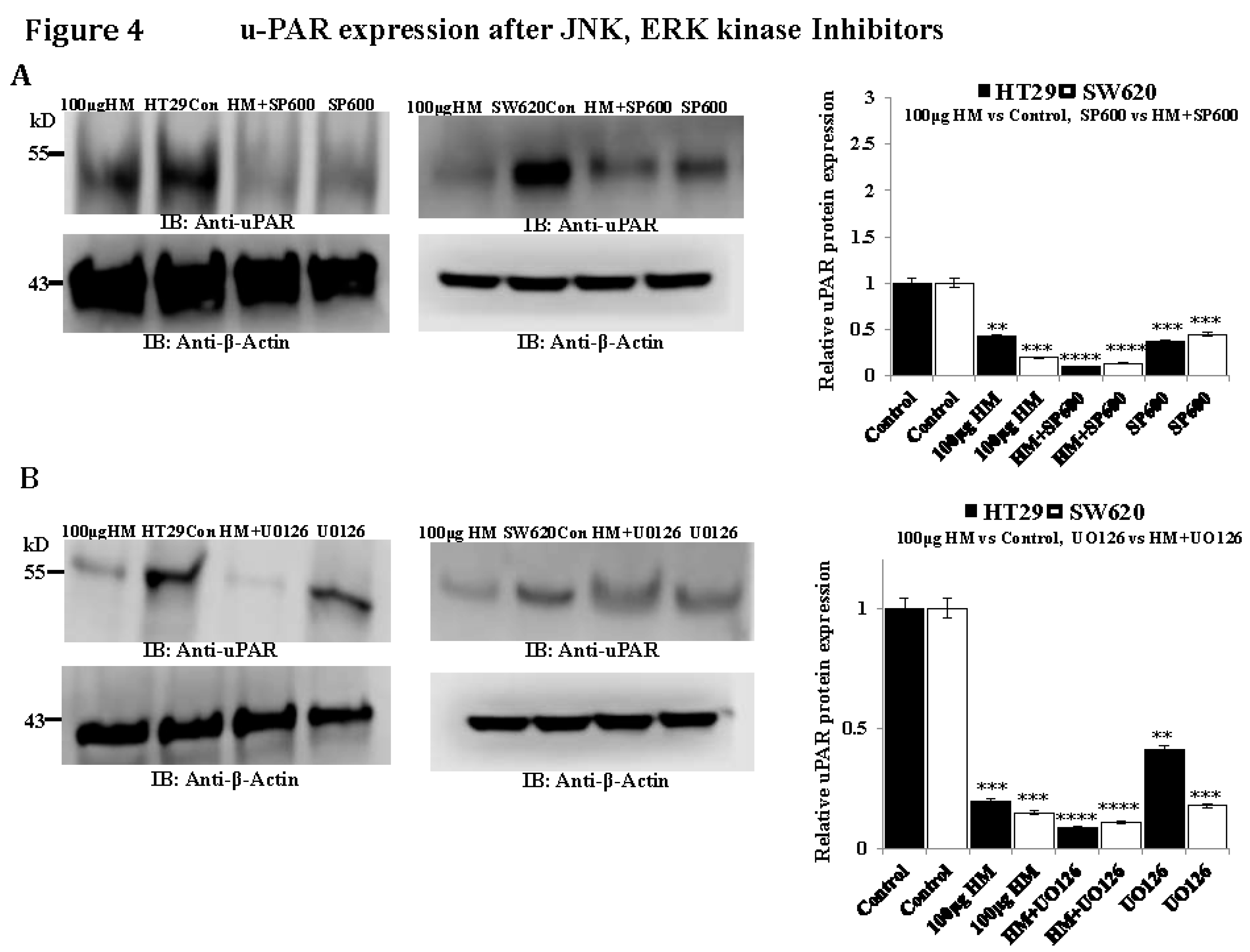

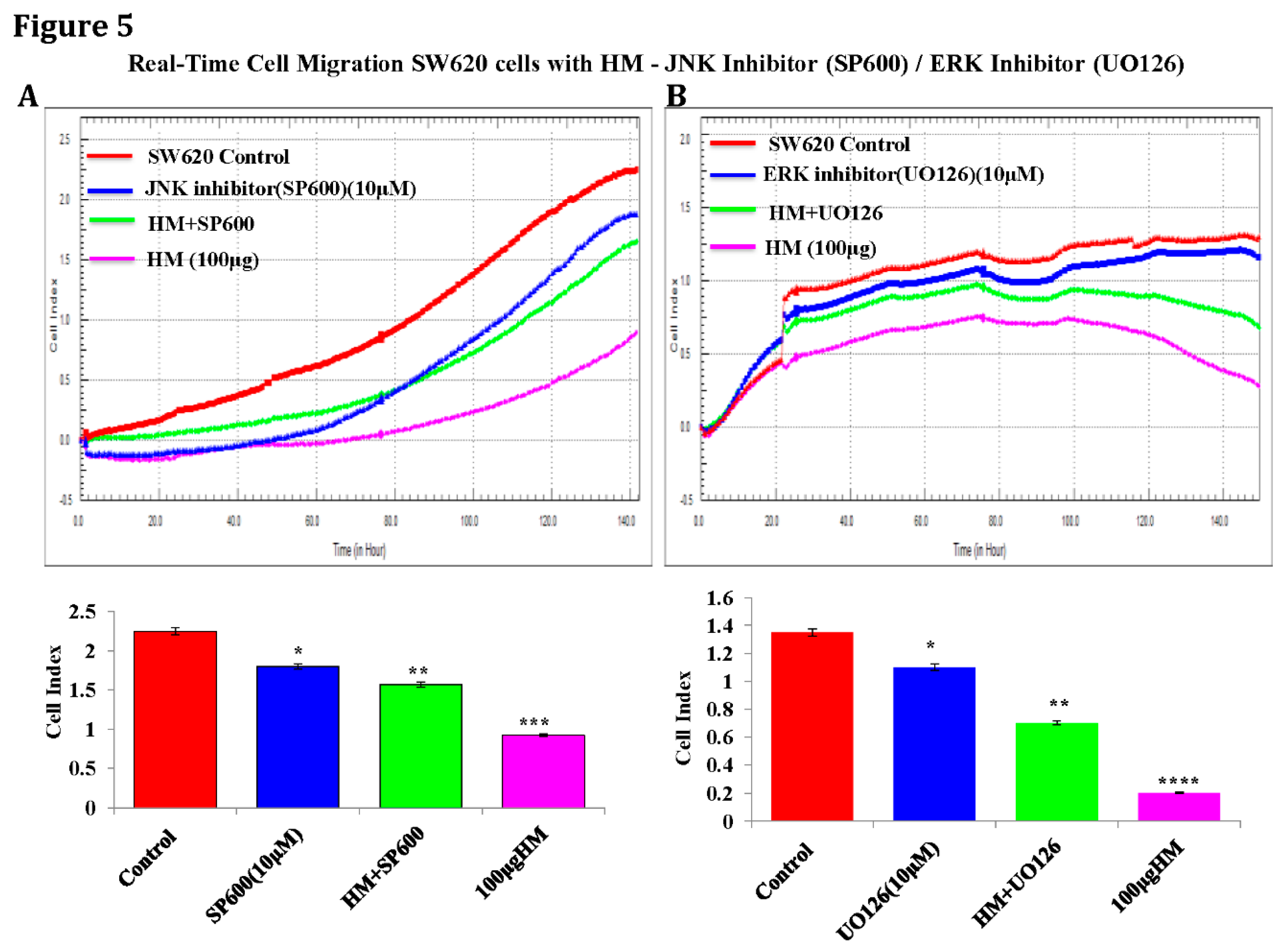

HM Downregulates uPAR Expression Level Through JNK and ERK Pathways

Discussion

Conclusion

Acknowledgments

Funding

Availability of Data and Materials

Author Contributions

Ethical Approval and Consent to Participate

Patient Consent for Publication

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, et al. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA Cancer J Clin 2021, 71:209-49. [CrossRef]

- Ferlay J, Colombet M, Soerjomataram I, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int J Cancer 2019, 144:1941-53. [CrossRef]

- Wang, N. Interpretation on the report of Global Cancer Statistics 2018. Journal of Multidisciplinary Cancer Management (Electronic Version) 2019, 5:87-98.

- Liu Z, Xu Y, Xu G, et al. Nomogram for predicting overall survival in colorectal cancer with distant metastasis. BMC Gastroenterol 2021, 21:103. [CrossRef]

- Guo K, Feng Y, Yuan L, et al. Risk factors and predictors of lymph nodes metastasis and distant metastasis in newly diagnosed T1 colorectal cancer. Cancer Med 2020, 9:5095-113. [CrossRef]

- Lv T, Wu X, Sun L, Hu Q, Wan Y, Wang L. et al. p53-R273H upregulates neuropilin-2 to promote cell mobility and tumor metastasis. Cell death & disease 2017, 8:e2995. [CrossRef]

- Hu L, Liang S, Chen H, Lv T, Wu J, Chen D. et al. DeltaNp63alpha is a common inhibitory target in oncogenic PI3K/Ras/Her2-induced cell motility and tumor metastasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114:E3964–e73. [CrossRef]

- Lv T, Lv H, Fei J, Xie Y, Lian D, Hu J. et al. p53-R273H promotes cancer cell migration via upregulation of neuraminidase-1. Journal of Cancer 2020, 11:6874–82. [CrossRef]

- Mohanam S, Sawaya RE, Yamamoto M, Bruner JM, Nicholson GL, Rao JS. Proteolysis and invasiveness of brain tumors: role of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor. J Neurooncol 1994, 22:153–60. [CrossRef]

- Yonemura Y, Nojima N, Kawamura T, Ajisaka H, Taniguchi K, Fujimura T. et al. Correlation between expression of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor and metastasis in gastric carcinoma. Oncol Rep 1997, 4:1229–34. [CrossRef]

- Park JS, Park JH, Khoi PN, Joo YE, Jung YD. MSP-induced RON activation upregulates uPAR expression and cell invasiveness via MAPK, AP-1 and NF-κB signals in gastric cancer cells. Carcinogenesis 2011, 32:175–81. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Cozzi PJ. Targeting uPA/uPAR in prostate cancer. Cancer Treat Rev 2007, 33:521–7.

- Ertongur S, Lang S, Mack B, Wosikowski K, Muehlenweg B, Gires O. Inhibition of the invasion capacity of carcinoma cells by WX-UK1, a novel synthetic inhibitor of the urokinase-type plasminogen activator system. Int J Cancer 2004 110:815–24.

- Hau AM, Leivo MZ, Gilder AS, Hu JJ, Gonias SL, Hansel DE. mTOR C2 activation is regulated by the urokinase receptor (uPAR) in bladder cancer. Cell Signal 2017, 29:96–106.

- Skovgaard D, Persson M, Brandt-Larsen M, Christensen C, Madsen J, Klausen TL. et al. Safety, Dosimetry, and Tumor Detection Ability of (68)Ga-NOTA-AE105: First-in-Human Study of a Novel Radioligand for uPAR PET Imaging. J Nucl Med 2017, 58:379–86.

- de Vries TJ, Quax PH, Denijn M, Verrijp KN, Verheijen JH, Verspaget HW. et al. Plasminogen activators, their inhibitors, and urokinase receptor emerge in late stages of melanocytic tumor progression. Am J Pathol 1994, 144:70–81.

- Del Vecchio S, Stoppelli MP, Carriero MV, Fonti R, Massa O, Li PY. et al. Human urokinase receptor concentration in malignant and benign breast tumors by in vitro quantitative autoradiography: comparison with urokinase levels. Cancer Res 1993, 53:3198–206.

- Huber MC, Mall R, Braselmann H, Feuchtinger A, Molatore S, Lindner K. et al. uPAR enhances malignant potential of triple-negative breast cancer by directly interacting with uPA and IGF1R. BMC Cancer 2016, 16:615. [CrossRef]

- Loosen SH, Tacke F, Püthe N, Binneboesel M, Wiltberger G, Alizai PH. et al. High baseline soluble urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (suPAR) serum levels indicate adverse outcome after resection of pancreatic adenocarcinoma. Carcinogenesis 2019 40:947–55. [CrossRef]

- Keer HN, Gaylis FD, Kozlowski JM, Kwaan HC, Bauer KD, Sinha AA. et al. Heterogeneity in plasminogen activator (PA) levels in human prostate cancer cell lines: increased PA activity correlates with biologically aggressive behavior. Prostate 1991, 18:201–14. [CrossRef]

- Tjwa M, Sidenius N, Moura R, Jansen S, Theunissen K, Andolfo A. et al. Membrane-anchored uPAR regulates the proliferation, marrow pool size, engraftment, and mobilization of mouse hematopoietic stem/progenitor cells. J Clin Invest 2009, 119:1008–18. [CrossRef]

- Laurenzana A, Chillà A, Luciani C, Peppicelli S, Biagioni A, Bianchini F. et al. uPA/uPAR system activation drives a glycolytic phenotype in melanoma cells. International journal of cancer 2017, 141:1190–200. [CrossRef]

- Laurenzana A, Fibbi G, Margheri F, Biagioni A, Luciani C, Del Rosso M. et al. Endothelial Progenitor Cells in Sprouting Angiogenesis: Proteases Pave the Way. Curr Mol Med 2015, 15:606–20. [CrossRef]

- Dass K, Ahmad A, Azmi AS, Sarkar SH, Sarkar FH. Evolving role of uPA/uPAR system in human cancers. Cancer Treat Rev 2008, 34:122–36. [CrossRef]

- Wang K, Xing ZH, Jiang QW, Yang Y, Huang JR, Yuan ML. et al. Targeting uPAR by CRISPR/Cas9 System Attenuates Cancer Malignancy and Multidrug Resistance. Frontiers in oncology 2019, 9:80. [CrossRef]

- Ahn SB, Mohamedali A, Pascovici D, Adhikari S, Sharma S, Nice EC. et al. Proteomics Reveals Cell-Surface Urokinase Plasminogen Activator Receptor Expression Impacts Most Hallmarks of Cancer. Proteomics 2019, 19:e1900026. [CrossRef]

- Maria Teresa Masucci, Michele Minopoli, Gioconda Di Carluccio et al. Therapeutic Strategies Targeting Urokinase and Its Receptor in Cancer. Cancers (Basel) 2022, Feb; 14(3): 498. [CrossRef]

- Xie S, Yang G, Wu J, Jiang L, Yuan C, Xu P, et al. In silico screening of natural products as uPAR inhibitors via multiple structure-based docking and molecular dynamic simulations. J Biomol Struct Dyn 2023, 18: 1-12. [CrossRef]

- El-Nagger NEA, Saber WIA. Natural melanin: Current trends, and future approaches, with especial reference to microbial source. Polymers 2022, 14(7): 1339.

- Alghamdi K, Alehaideb Z, Kumar A, Al-Eidi H, Alghamdi SS, Suliman R, et al. Stimulatory effects of Lycium shawii on human melanocyte proliferation, migration, and melanogenesis: In vitro and in silico studies. Front Pharmacol 2023, 14: 1169812. [CrossRef]

- ElObeid AS, Kama-Eldin A, Abdelhalim MAK, Haseeb AM. Pharmacological properties of melanin and its function in health. Basic Clin Pharmacol Toxicol 2017, 120(6): 515-522. [CrossRef]

- El-Obeid A, Alajmi H, Harbi M, Yahya WB, Al-Eidi H, Alaujan M, et al. Distinct anti-proliferative effects of herbal melanin on human acute monocytic leukemia THP-1 cells and embryonic kidney HEK293 cells. BMC Complement Med Ther 2020, 20(1): 154. [CrossRef]

- Omar Al-Obeed, Adila Salih El-Obeid, Sabine Matou-Nasri, Mansoor-Ali Vaali-Mohammed, et al. Herbal melanin inhibits colorectal cancer cell proliferation by altering redox balance, inducing apoptosis, and modulating MAPK signaling. Cancer Cell Int 2020, 20: 126. [CrossRef]

- Rajabathar JR, Al-Lohdan H, Arokiyaraj S, Mohammed F, Al-Dhayan DM, Faqihi NA, et al. Herbal melanin inhibits real-time cell proliferation, downregulates anti-apoptotic proteins and upregulates pro-apoptotic p53 expression in MDA-MB-231 and HCT-116 cancer cell lines. Medicina 2023, 59(12): 2061.

- El-Obeid A, Al-Harbi S, Al-Jomah N, Hassib A. Herbal melanin modulates tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-), interleukin 6 (IL-6) and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF) production. Phytomedicine 2006, 13(5): 324-333. [CrossRef]

- Sah DK, Khoi PN, Li S, Arjunan A, Jeong JU, Jung YD. Epigallocatechin-3-gallate prevents IL-1β-induced uPAR expression and invasiveness via the suppression of NF-B and AP-1 in human bladder cancer cells. Int J Mol Sci 2022, 23: 14008. [CrossRef]

- Ding Y, Niu W, Zheng X, Zhou C, Wang G, Fend Y, et al. Plasminogen activator, urokinase enhances the migration, invasion, and proliferation of colorectal cancer cells by activating the Src/ERK pathway. J Gastrointest Oncol 2022, 13(6): 3100-3111. [CrossRef]

- Huang XM, Yang ZJ, Xie Q, Zhang ZK, Zhang H, Ma JY. Natural product for treating colorectal cancer: A mechanistic review. Biomed Pharmacother 2019, 117: 109142. [CrossRef]

- Islam MR, Akash S, Rahman MM, Nowrin FT, Akter T, Shohag S, et al. Colon cancer and colorectal cancer: Prevention and treatment by potential natural products. Chem Biol Interact 2022, 368: 110170. [CrossRef]

- Honari M, Shafabakhsh R, Reiter RJ, Mirzaei H, Asemi Z. Resveratrol is a prominent agent for colorectal cancer prevention and treatment: focus on molecular mechanisms. Cancer Cell Int 2019, 19: 180. [CrossRef]

- Anwar MJ, Altaf A, Imran M, Amir M, Alsagaby SA, Al Abdulmonem W, et al. Anti-cancer perspectives of resveratrol: a comprehensive review. Food Agricultural Immunol 2023, 34: 1. [CrossRef]

- He J, Chen S, Yu T, Chen W, Huang J, Peng C, et al. Harmine suppresses breast cancer cell migration and invasion by regulating TAZ-mediated epithelial-mesenchymal transition. Am J Cancer Res 2022, 12(6): 2612-2626.

- Liang H, Chen Z, Yang R, Huang Q, Chen H, Chen W, et al. Methyl Gallate suppresses the migration, invasion, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition of hepatocellular carcinoma cells via the AMPK/NF/kB signaling pathway in vitro and in vivo. Front Pharmacol 2022, 13: 894285.

- Oberg F, Ahnfelt M, Ponten F, Westermark B, El-Obeid A. Herbal melanin activates TLR4/NF-kappaB signaling pathway. Phytomoedicine 2009, 16(5): 477-484. [CrossRef]

- El-Naggar NEA, Al-Ewasy SM. Bioproduction, characterization, anticancer and antioxidant activities of extracellular melanin pigment produced by newly isolated microbial cell factories Streptomyces glaucescens NEAE-H. Sci. Rep 2017, 7: 1-19.

- Ye Y, Wang C, Zhang X, Hu Q, Zhang Y, Liu Q, et al. A melanin-mediated cancer immunotherapy patch. Sci. Immunol 2017, 2: eaan5692. [CrossRef]

- Alamelu, G. Bharadwaj, Ryan W. Holloway, et al. Plasmin and Plasminogen System in the Tumor Microenvironment: Implications for Cancer Diagnosis, Prognosis, and Therapy. Cancers (Basel) 2021, Apr; 13(8): 1838. [CrossRef]

- Casalino L, Talotta F, Cimmino A, Verde P. The Fra-1/AP-1 oncoprotein: From the “undruggable” transcription factor to therapeutic targeting. Cancers (Basel) 2022, 14(6): 1480.

- Lian S, Li S, Sah DK, Kim NH, Lakshmanan VK, Jung YD. Suppression of urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor by docosahexaenoic acid mediated by heme oxygenase-1 in 12-O-Tetradecanoyphorbol-13-acetate-induced human endothelial cells. Front. Pharmacol 2020, 11: 577302. [CrossRef]

- Piet M, Paduch R. Ursolic and oleanolic acids in combination therapy inhibit migration of colon cancer cells through down-regulation of the uPA/uPAR dependent MMPs pathway. Chem Biol Interact 2022, 368: 110202. [CrossRef]

- Uzawa K, Amelio AL, Kasamatsu A, Saito T, Kita A, Fukamachi M, et al. Resveratrol targets urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor expression to overcome cetuximab-resistance in oral squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep 2019, 9: 12179. [CrossRef]

- Li D, Liu S, Shan H, Conti P, Li Z. Urokinase plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) targeted nuclear imaging and radionuclide therapy. Theranostics 2013, 3:507–15. [CrossRef]

- Iasmina Marcovici, Dorina Coricovac, et al. Melanin and Melanin-Functionalized Nanoparticles as Promising Tools in Cancer Research - A Review. Cancers (Basel) 2022, Apr; 14(7): 1838. [CrossRef]

| Target genes | Primer sequences |

| E-cadherin N-cadherin uPAR GAPDH |

F: 5′ -ACCAGAATAAAGACCAAGTGACCA-3′ R: 5′- AGCAAGAGCAGCAGAATCAGAAT -3′ F: 5′-ATTGGACCATCACTCGGCTTA-3′ R: 5′-CACACTGGCAAACCTTCACG-3′ F: 5′-TGCAATGCCGCTATCCTACA-3′ R: 5′-TGGGCATCCGGGAAGACT-3′ F: 5′-AAGGTCGG AGTCAACGGATTTGGT-3′ R: 5′-ATGGCATGGACTGTGGTCATAGT-3′ |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).