1. Introduction

Hexanoic acid (also known as caproic acid) is a saturated carboxylic acid with a six-carbon chain and the chemical formula C₆H₁₂O₂. In the context of human physiology, hexanoic acid belongs to the class of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), which are generated through the fermentation of dietary fiber by the gut microbiota. SCFAs, including acetate, propionate, and butyrate, are well-known for their beneficial effects on host health, such as modulation of inflammatory responses, maintenance of intestinal barrier integrity, and involvement in energy metabolism. However, the role of hexanoic acid in these physiological processes remains poorly understood.

Evidence suggests that elevated levels of certain SCFAs in plasma may be associated with unfavorable metabolic conditions. For instance, in the study by M. Thing et al. [

1], patients with metabolic-associated steatotic liver disease (MASLD) exhibited increased plasma concentrations of propionate, butyrate, and valerate, which may indicate their potential involvement in the onset or progression of the disease.

In the context of chronic heart failure (CHF) and sarcopenia, data regarding the effects of hexanoic acid are scarce. Nonetheless, it is well established that dysregulation of SCFA profiles can influence inflammatory signaling and muscle metabolism, which is of particular relevance for patients with CHF and sarcopenia. Elevated levels of specific SCFAs may promote systemic inflammation, disrupt energy homeostasis, and accelerate skeletal muscle degradation, all of which contribute to poor clinical outcomes in individuals with CHF.

Therefore, evaluating plasma levels of hexanoic acid in patients with CHF and sarcopenia is of scientific interest to better understand its potential role in cardiovascular complications and muscle dysfunction. Further research is warranted to elucidate the clinical significance of hexanoic acid as a biomarker and its potential as a therapeutic target in this patient population.

2. Results

A total of 636 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of chronic heart failure (CHF) were screened. In 63 patients, assessment of body composition using bioelectrical impedance analysis was not feasible due to the presence of implanted electronic devices (e.g., pacemakers). Sarcopenia was identified in 114 patients; however, only 74 of them met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (

Table 1) and were included in the final analysis.

The follow-up period was 1.5 years, during which plasma levels of various short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), including hexanoic acid, were analyzed in relation to adverse cardiovascular events and all-cause mortality.

The mean age of participants was 68.3 ± 5.7 years, with 58% being male. A high prevalence of comorbid conditions commonly observed in CHF and sarcopenia patients was documented:

• Arterial hypertension – 81%

• Type 2 diabetes mellitus – 36%

• Chronic kidney disease – 42%

• Coronary artery disease – 67%

• Atrial fibrillation – 28%

• Post-infarction cardiosclerosis – 32%

Cardiological examination revealed a mean left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) of 41.2 ± 7.5%, indicating predominantly heart failure with mildly reduced or preserved systolic function.

Sarcopenia was diagnosed in accordance with EWGSOP2 criteria, including assessment of muscle strength, muscle mass, and physical performance.

The mean handgrip strength was 18.5 ± 3.8 kg in men and 14.2 ± 2.9 kg in women, which was significantly below the reference values.

Total skeletal muscle mass, as measured by bioelectrical impedance analysis, averaged 27.8 ± 3.9 kg, indicating marked muscle loss.

Assessment using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB) yielded a mean score of 6.1 ± 1.8 points, reflecting substantial impairment in physical function and a high risk of falls.

One of the key objectives of the study was to evaluate plasma concentrations of SCFAs. Measured analytes included acetic acid, propanoic acid, butanoic acid, isobutyric acid, pentanoic acid, 3-methylbutanoic acid, 2-methylbutanoic acid, 4-methylpentanoic acid, and hexanoic acid.

All patients included in the final analysis exhibited elevated plasma SCFA concentrations exceeding reference values (

Table 2). The most pronounced increase was observed in butanoic acid, with a 32.8-fold elevation above the reference range. Propanoic acid levels exceeded normal values by a factor of 10.9.

Elevations were also noted for other SCFAs: isobutyric acid (2.82-fold), 2-methylbutanoic acid (1.11-fold), 3-methylbutanoic acid (1.12-fold), hexanoic acid (1.09-fold), 4-methylpentanoic acid (1.20-fold), and pentanoic acid (1.33-fold).

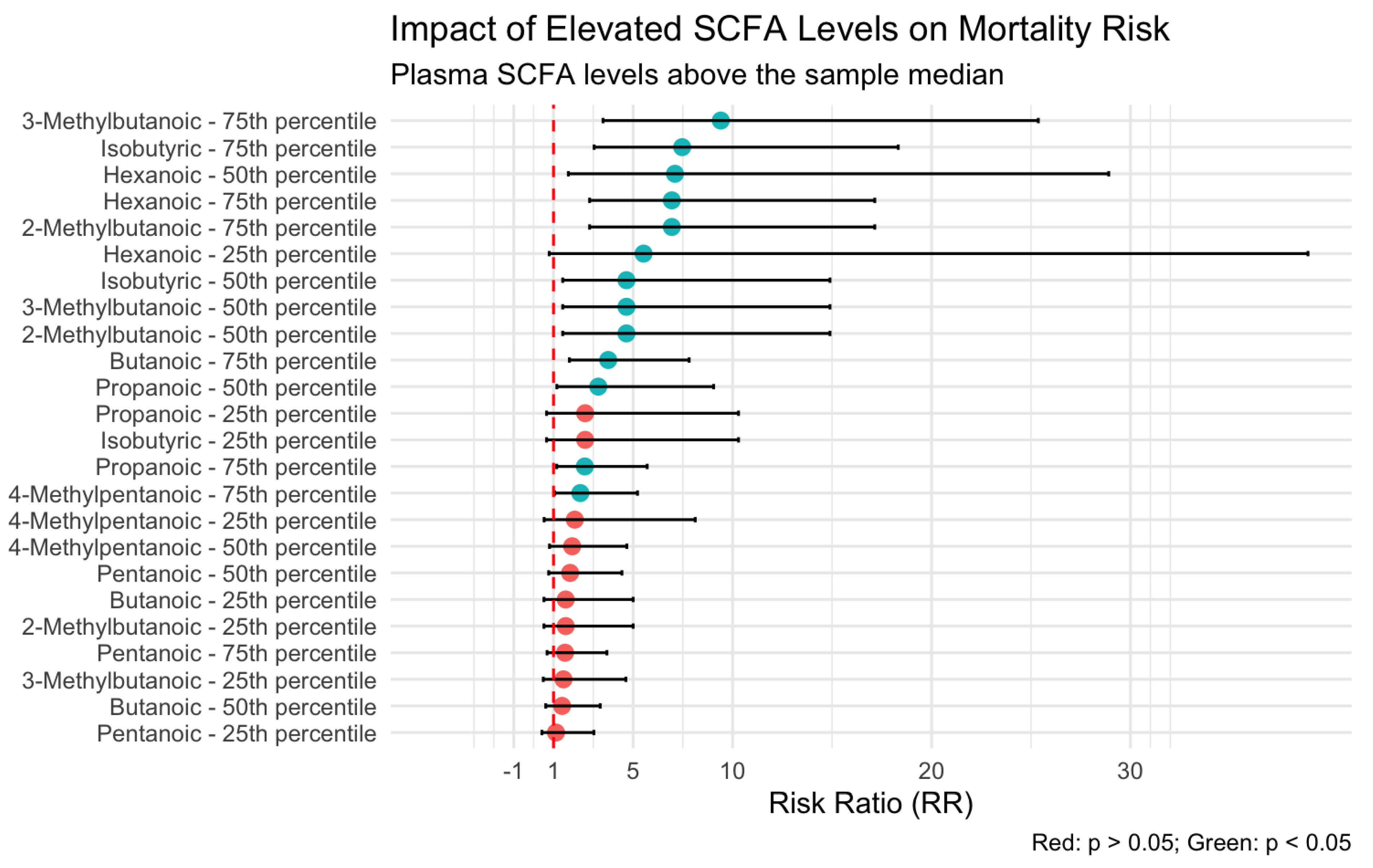

Analysis of the association between plasma SCFA levels and patient outcomes revealed that hexanoic acid exerted the most pronounced influence on mortality risk. As illustrated in

Figure 1, plasma concentrations of hexanoic acid above the 50th percentile were associated with a seven-fold increase in the risk of death (odds ratio [OR] = 7.10; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.74–28.9).

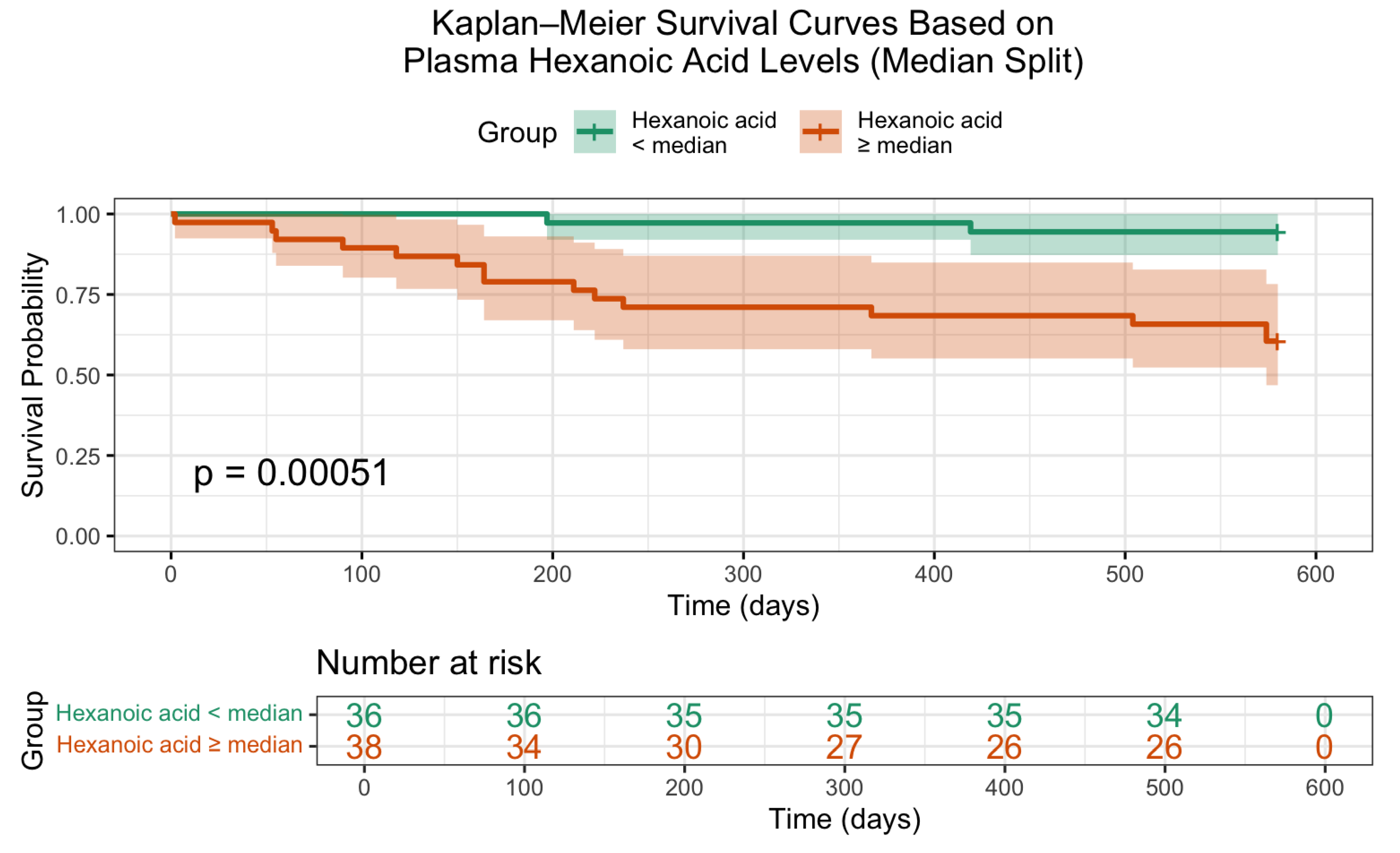

Additionally, Kaplan–Meier survival analysis (

Figure 3) confirmed a statistically significant difference in overall survival based on hexanoic acid levels. Patients with lower concentrations of this metabolite exhibited markedly improved survival probabilities (log-rank p = 0.00051), underscoring its potential prognostic value.

3. Discussion

Hexanoic acid (C6) is primarily derived from dietary sources rather than being produced by gut microbiota. It is present in triacylglycerol form in coconut and palm oils and is metabolized in the human body as an energy substrate [

2,

3]. Unlike acetate to valerate (C2–C5), hexanoic acid is generated through β-oxidation of long-chain fatty acids in the liver [

4,

5]. Structurally, C2–C5 and C6 differ by only a few carbon atoms, yet studies have demonstrated considerable differences in their immunological properties.

It is well established that C2–C5 exhibit anti-inflammatory properties [

6], particularly through maintenance of intestinal epithelial integrity by mitigating the inflammatory microenvironment at the mucosal interface [

4]. This effect is associated with decreased activity of nuclear factor κB (NF-κB) and increased release of prostaglandin E2 [

7,

8,

9]. Literature reports that C2–C5 reduce the production of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin-1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNF-α) [

10]. These effects are best characterized for butyric acid (C4), particularly in the presence of lipopolysaccharides acting via toll-like receptor 4 (TLR4). One hypothesis posits that TLR4, a homodimer signaling through adaptor proteins MyD88/MAL and TRIF/TRAM, is evolutionarily conserved and plays a sentinel role in the regulation of core physiological responses [

11]. The microbiota-derived production of C2–C5, with their pleiotropic functions in epithelial maintenance and regulation of cellular proliferation, aligns with the evolutionarily conserved pattern of TLR4 signaling. Specifically, C4-induced anti-inflammatory effects have been shown to act through TLR4-mediated pathways, suppressing the expression of the adaptor protein TRAF6 [

12,

13].

Conversely, hexanoic acid (C6) has been associated with pro-inflammatory effects, not only through increased production of pro-inflammatory cytokines but also via suppression of IL-10 production through the TLR2 signaling pathway [

10]. TLR2 typically functions as a heterodimer. Evolutionarily, TLR2 is believed to demonstrate plasticity in its ability to respond to diverse and dynamic environmental ligands and pathogens, including pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), microbial-associated molecular patterns (MAMPs), and damage-associated molecular patterns (DAMPs) [

14].

In our study, elevated plasma levels of hexanoic acid above the 50th percentile were associated with a seven-fold increase in mortality risk. C6 stimulation has been linked to increased transcription of GPR84 and PPARγ, two receptors thought to mediate C6’s pro-inflammatory actions and further promote IL-6 and IL-1β expression [

15]. PPARγ is known to play a role in insulin sensitivity and adipogenesis.

Another immunoregulatory consequence of C6 exposure is the altered ratio of HIF-1α to HIF-2α. These HIF-α subunits are transcription factors that regulate cellular metabolism and angiogenesis in response to hypoxic and inflammatory stress. HIF-1α is predominantly involved in the regulation of genes associated with glycolysis and NADPH regeneration under hypoxia [

16]. Studies have shown that inflammation triggered by C6 leads to suppression of HIF-1α transcription and preferential induction of HIF-2α. In contrast, exposure to C4 does not significantly affect HIF-1α expression, though other data suggest that C4 may stabilize HIF-1α under hypoxic conditions, for example, in the intestinal epithelium [

11]. HIF-2α is believed to regulate a broader spectrum of target genes, including those involved in inflammatory responses and lipid metabolism. These findings indicate that the altered HIF-1α/HIF-2α activation may represent a compensatory response to enhanced inflammation induced by hexanoic acid [

10,

14,

16].

4. Materials and Methods

The study was conducted at City Clinical Hospital No. 4, Moscow Healthcare Department (GKB No. 4 DZM), between September 2019 and December 2021. A total of 636 patients with a confirmed diagnosis of chronic heart failure (CHF) were screened. In 63 patients, body composition analysis via bioelectrical impedance was not feasible due to the presence of implanted cardiac pacemakers. Sarcopenia was identified in 114 patients; however, only 74 met the inclusion and exclusion criteria (

Table 1) and were included in the final analysis.

Sarcopenia was diagnosed in accordance with the recommendations of the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2) [

18]. Skeletal muscle mass was assessed using a bioelectrical impedance analyzer (ABC-02, MEDASS, Russia). Handgrip strength was measured using a manual dynamometer (DK-25). Physical performance was evaluated using the Short Physical Performance Battery (SPPB).

All patients underwent comprehensive clinical assessment, including blood sampling to determine plasma levels of short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs), specifically: butanoic acid, propanoic acid, isobutyric acid, 2-methylbutanoic acid, 3-methylbutanoic acid, hexanoic acid, pentanoic acid, and 4-methylpentanoic acid. Quantification of SCFAs was performed using high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with mass spectrometry (HPLC-MS/MS).

Reference values for SCFAs were established based on the monitored MRM transitions of their derivatized forms:

– Propanoic acid (C3): 180.05 → 91.05 ng/mL

– Butanoic acid (C4) and isobutyric acid (iC4): 194.10 → 91.05 ng/mL

– Pentanoic acid (C5), 2-methylbutanoic acid (αC5), and 3-methylbutanoic acid (βC5): 208.15 → 91.05 ng/mL

– 4-Methylpentanoic acid (iC6) and hexanoic acid (C6): 222.10 → 91.05 ng/mL

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using R language (version 4.3.1) and RStudio software (Posit, Boston, MA, USA). Data distribution was assessed using the Shapiro–Wilk test. Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD) for normally distributed data or as median and interquartile range (IQR) for non-normally distributed variables. Categorical variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages.

Group comparisons were conducted using the Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U test for continuous variables, and the chi-squared test or Fisher’s exact test for categorical variables, as appropriate. Paired data before and after intervention were analyzed using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test or paired t-test, depending on normality.

The association between plasma SCFA concentrations and mortality risk was evaluated using logistic regression analysis. Odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) were calculated. Survival analysis was performed using Kaplan–Meier curves, and differences between groups were assessed with the log-rank test.

A two-tailed p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

High plasma SCFA levels, such as propanoic, butanoic, isobutanoic, pentanoic, 2-methylbutanoic, 3-methylbutanoic, and hexanoic acids, may indicate impaired intestinal barrier integrity in CHF patients. Metformin treatment significantly reduced plasma SCFA levels, possibly due to improved intestinal barrier function and reduced inflammation. Metformin also demonstrated positive effects on physical performance and muscle strength, although significant muscle mass increase was not observed. These results highlight the potential of extended-release metformin in managing glycemia in prediabetes patients and improving metabolic profiles and reducing inflammation-related processes associated with CHF and sarcopenia.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.O.D. and A.V.S.; methodology, D.O.D.; software, Y.V.G.; validation, A.V.S., D.O.D. and A.V.K.; formal analysis, A.V.K.; investigation, A.V.S.; resources, G.P.A.; data curation, A.V.K.; writing—original draft preparation, D.O.D.; writing—review and editing, A.V.S.; visualization, Y.V.G.; supervision, G.P.A.; project administration, D.O.D. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Pirogov Russian National Research Medical University (Protocol № 137/19 from 2 September 2019).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study. Written Informed Consent for Publication Written informed consent has been obtained from the patient(s) to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

The data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request. Data are not publicly available due to privacy and ethical restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the administrative and technical support provided by the staff of GKB No. 4 DZM and NIIOZMM. During the preparation of this manuscript, the authors used ChatGPT-4 (OpenAI, 2024) to support drafting, revision, and translation of scientific text. The authors have reviewed and edited the output and take full responsibility for the content of this publication.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Thing M, Werge MP, Kimer N, Hetland LE, Rashu EB, Nabilou P, Junker AE, Galsgaard ED, Bendtsen F, Laupsa-Borge J, McCann A, Gluud LL. Targeted metabolomics reveals plasma short-chain fatty acids are associated with metabolic dysfunction-associated steatotic liver disease. BMC Gastroenterol. 2024 Jan 23;24(1):43. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Andoh A, Takaya H, Araki Y, Tsujikawa T, Fujiyama Y, Bamba T. Medium- and long-chain fatty acids differentially modulate interleukin-8 secretion in human fetal intestinal epithelial cells. J Nutr. 2000 Nov;130(11):2636-40. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Takeuchi H, Sekine S, Kojima K, Aoyama T. The application of medium-chain fatty acids: edible oil with a suppressing effect on body fat accumulation. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2008;17 Suppl 1:320-3. [PubMed]

- Haghikia A, Jörg S, Duscha A, Berg J, Manzel A, Waschbisch A, Hammer A, Lee DH, May C, Wilck N, Balogh A, Ostermann AI, Schebb NH, Akkad DA, Grohme DA, Kleinewietfeld M, Kempa S, Thöne J, Demir S, Müller DN, Gold R, Linker RA. Dietary Fatty Acids Directly Impact Central Nervous System Autoimmunity via the Small Intestine. Immunity. 2015 Oct 20;43(4):817-29. Erratum in: Immunity. 2016 Apr 19;44(4):951-3. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2016.04.006. PMID: 26488817. [CrossRef]

- Ohira H, Tsutsui W, Fujioka Y. Are Short Chain Fatty Acids in Gut Microbiota Defensive Players for Inflammation and Atherosclerosis? J Atheroscler Thromb. 2017 Jul 1;24(7):660-672. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Tan J, McKenzie C, Potamitis M, Thorburn AN, Mackay CR, Macia L. The role of short-chain fatty acids in health and disease. Adv Immunol. 2014;121:91-119. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cox MA, Jackson J, Stanton M, Rojas-Triana A, Bober L, Laverty M, Yang X, Zhu F, Liu J, Wang S, Monsma F, Vassileva G, Maguire M, Gustafson E, Bayne M, Chou CC, Lundell D, Jenh CH. Short-chain fatty acids act as antiinflammatory mediators by regulating prostaglandin E(2) and cytokines. World J Gastroenterol. 2009 Nov 28;15(44):5549-57. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Segain JP, Raingeard de la Blétière D, Bourreille A, Leray V, Gervois N, Rosales C, Ferrier L, Bonnet C, Blottière HM, Galmiche JP. Butyrate inhibits inflammatory responses through NFkappaB inhibition: implications for Crohn's disease. Gut. 2000 Sep;47(3):397-403. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Thangaraju M, Cresci GA, Liu K, Ananth S, Gnanaprakasam JP, Browning DD, Mellinger JD, Smith SB, Digby GJ, Lambert NA, Prasad PD, Ganapathy V. GPR109A is a G-protein-coupled receptor for the bacterial fermentation product butyrate and functions as a tumor suppressor in colon. Cancer Res. 2009 Apr 1;69(7):2826-32. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sam QH, Ling H, Yew WS, Tan Z, Ravikumar S, Chang MW, Chai LYA. The Divergent Immunomodulatory Effects of Short Chain Fatty Acids and Medium Chain Fatty Acids. Int J Mol Sci. 2021 Jun 16;22(12):6453. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Ferwerda B, McCall MB, Alonso S, Giamarellos-Bourboulis EJ, Mouktaroudi M, Izagirre N, Syafruddin D, Kibiki G, Cristea T, Hijmans A, Hamann L, Israel S, ElGhazali G, Troye-Blomberg M, Kumpf O, Maiga B, Dolo A, Doumbo O, Hermsen CC, Stalenhoef AF, van Crevel R, Brunner HG, Oh DY, Schumann RR, de la Rúa C, Sauerwein R, Kullberg BJ, van der Ven AJ, van der Meer JW, Netea MG. TLR4 polymorphisms, infectious diseases, and evolutionary pressure during migration of modern humans. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2007 Oct 16;104(42):16645-50. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Jakus PB, Kalman N, Antus C, Radnai B, Tucsek Z, Gallyas F Jr, Sumegi B, Veres B. TRAF6 is functional in inhibition of TLR4-mediated NF-κB activation by resveratrol. J Nutr Biochem. 2013 May;24(5):819-23. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto M, Sato S, Hemmi H, Hoshino K, Kaisho T, Sanjo H, Takeuchi O, Sugiyama M, Okabe M, Takeda K, Akira S. Role of adaptor TRIF in the MyD88-independent toll-like receptor signaling pathway. Science. 2003 Aug 1;301(5633):640-3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li J, Lee DS, Madrenas J. Evolving Bacterial Envelopes and Plasticity of TLR2-Dependent Responses: Basic Research and Translational Opportunities. Front Immunol. 2013 Oct 28;4:347. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Suzuki M, Takaishi S, Nagasaki M, Onozawa Y, Iino I, Maeda H, Komai T, Oda T. Medium-chain fatty acid-sensing receptor, GPR84, is a proinflammatory receptor. J Biol Chem. 2013 Apr 12;288(15):10684-91. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Downes NL, Laham-Karam N, Kaikkonen MU, Ylä-Herttuala S. Differential but Complementary HIF1α and HIF2α Transcriptional Regulation. Mol Ther. 2018 Jul 5;26(7):1735-1745. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rankin EB, Rha J, Selak MA, Unger TL, Keith B, Liu Q, Haase VH. Hypoxia-inducible factor 2 regulates hepatic lipid metabolism. Mol Cell Biol. 2009 Aug;29(16):4527-38. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Cruz-Jentoft AJ, Bahat G, Bauer J, Boirie Y, Bruyère O, Cederholm T, Cooper C, Landi F, Rolland Y, Sayer AA, Schneider SM, Sieber CC, Topinkova E, Vandewoude M, Visser M, Zamboni M; Writing Group for the European Working Group on Sarcopenia in Older People 2 (EWGSOP2), and the Extended Group for EWGSOP2. Sarcopenia: revised European consensus on definition and diagnosis. Age Ageing. 2019 Jan 1;48(1):16-31. Erratum in: Age Ageing. 2019 Jul 1;48(4):601. doi: 10.1093/ageing/afz046. PMID: 30312372; PMCID: PMC6322506. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).