Submitted:

26 August 2025

Posted:

27 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

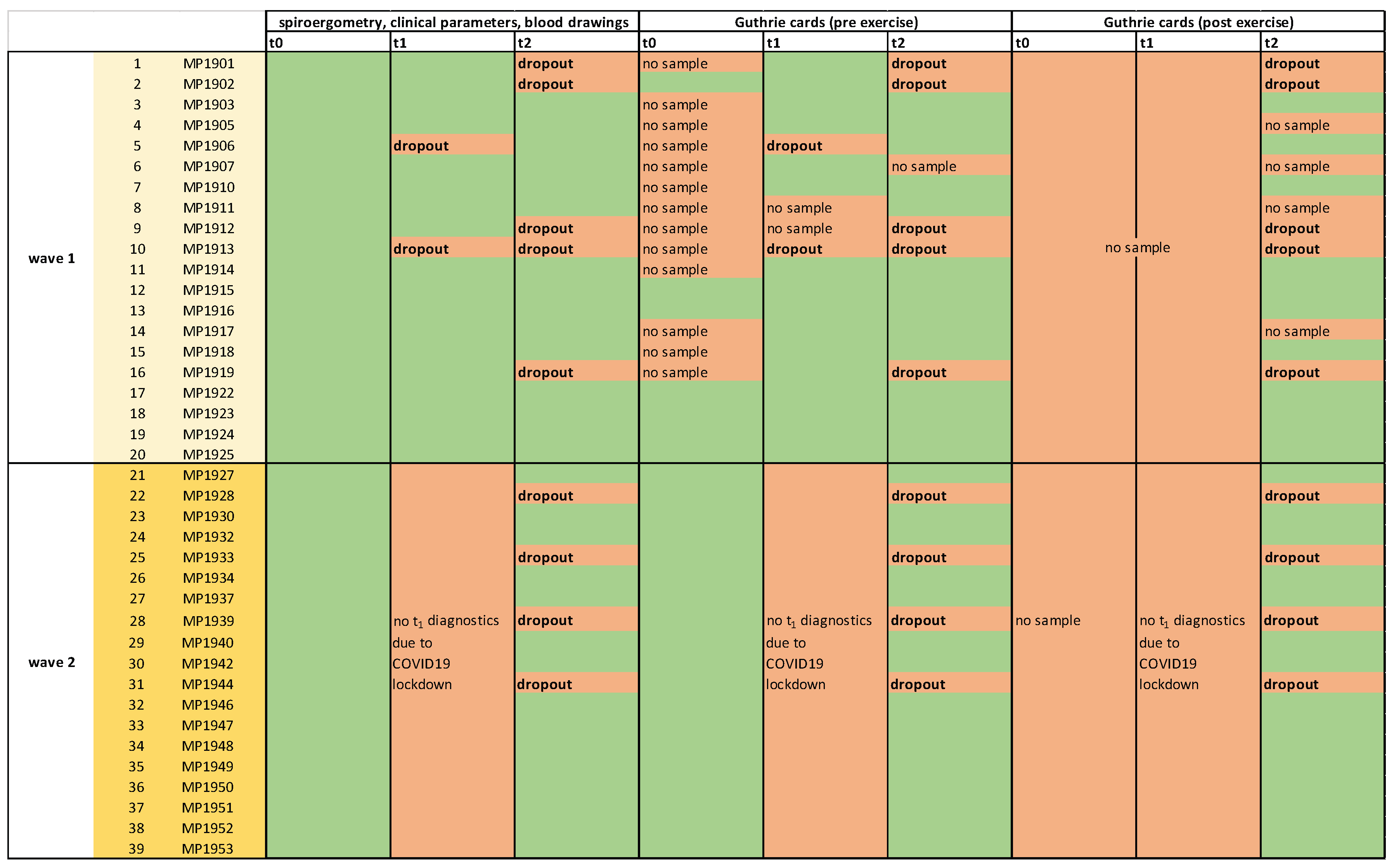

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. MultiPill-Exercise Pilot Study

2.2.“. Mini Metabolomics”: Metabolomics Analysis from Dried Blood Spots

2.3. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

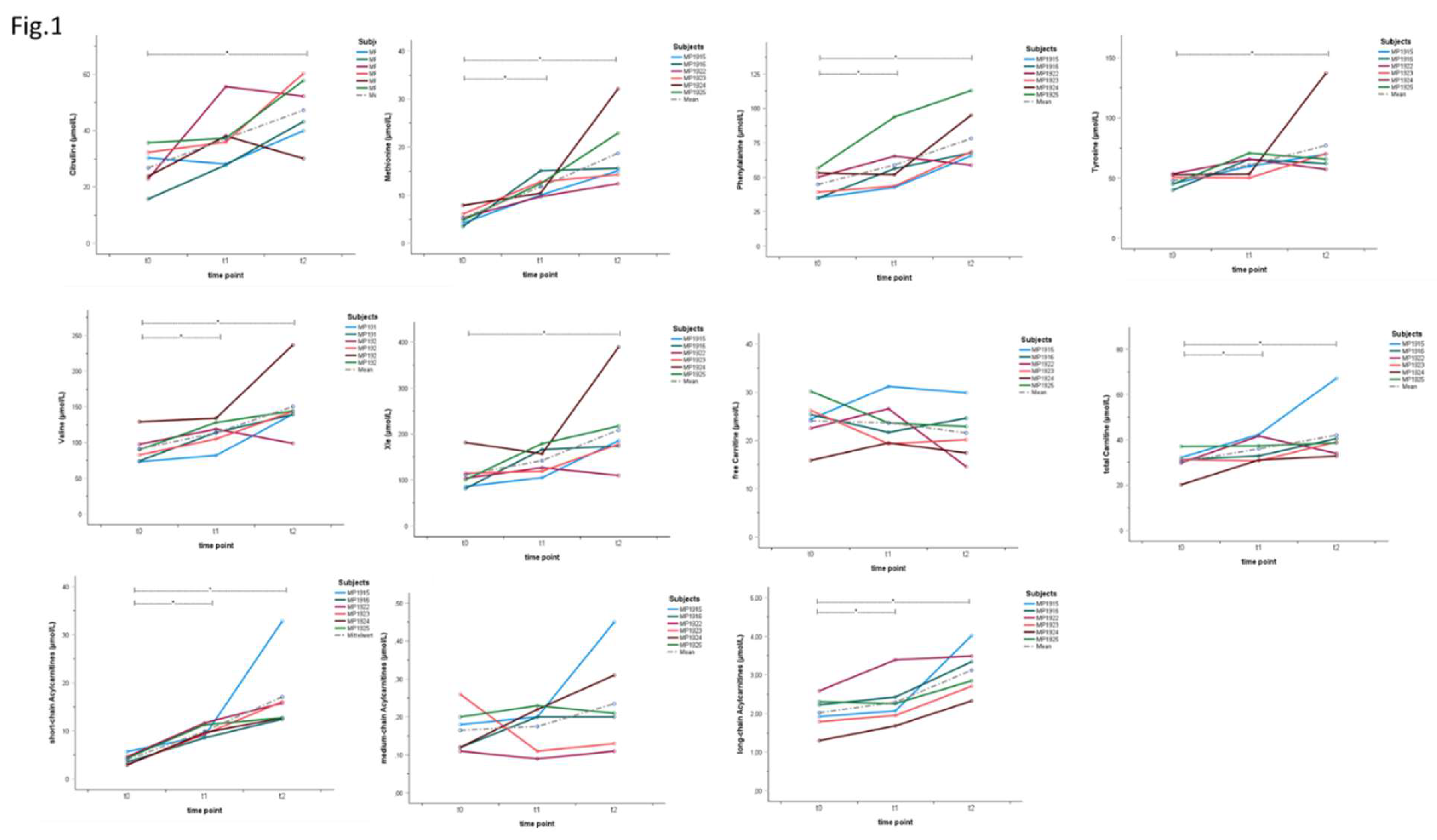

3.1. Individual Metabolite Kinetics Throughout the Intervention

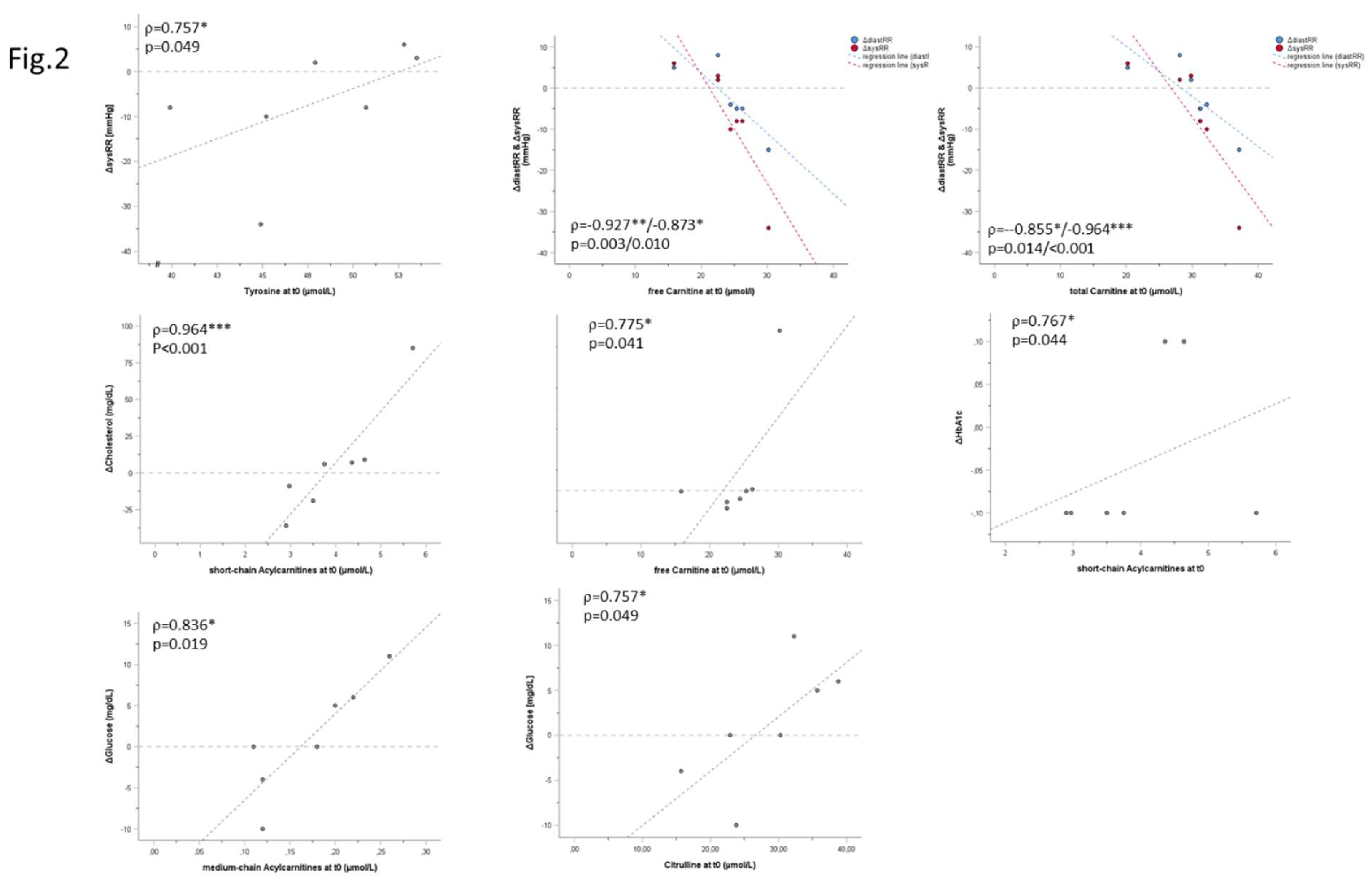

3.2. Correlation Analysis

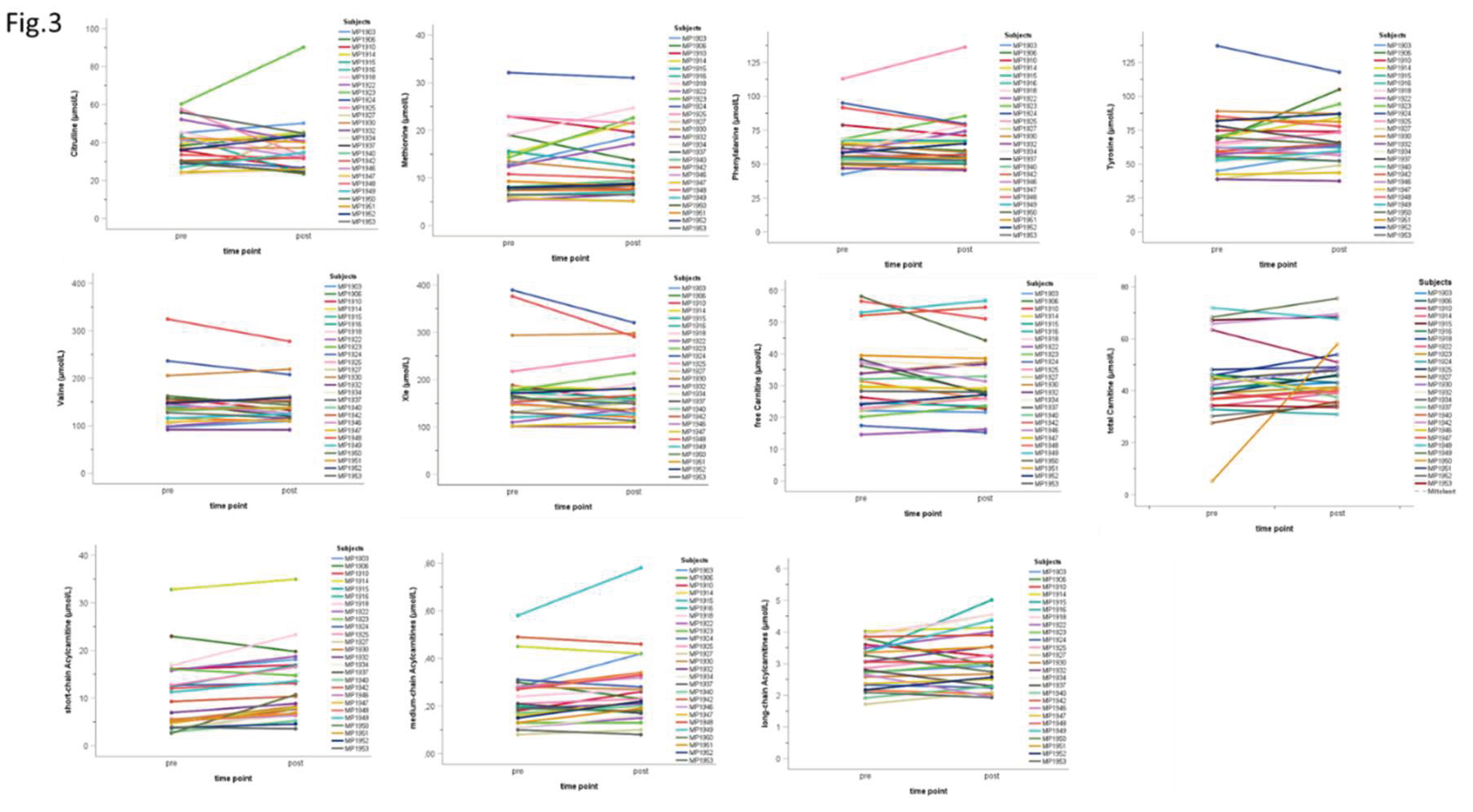

3.3. Individual Acute Response at t2

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

6. Study Limitations

Conflicts of Interest statement

Author Contributions statement

Acknowledgments

References

- Adeva-Andany MM, Calvo-Castro I, Fernández-Fernández C, Donapetry-García C, Pedre-Piñeiro AM. Significance of l-carnitine for human health. IUBMB Life. 2017 Aug;69(8):578-594. Epub 2017 Jun 26. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carrard J, Guerini C, Appenzeller-Herzog C, Infanger D, Königstein K, Streese L, Hinrichs T, Hanssen H, Gallart-Ayala H, Ivanisevic J, Schmidt-Trucksäss A. The Metabolic Signature of Cardiorespiratory Fitness: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2022 Mar;52(3):527-546. Epub 2021 Nov 10. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Flynn NE, Shaw MH, Becker JT. Amino Acids in Health and Endocrine Function. Adv Exp Med Biol. 2020;1265:97-109. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hansen JS, Zhao X, Irmler M, Liu X, Hoene M, Scheler M, Li Y, Beckers J, Hrabĕ de Angelis M, Häring HU, Pedersen BK, Lehmann R, Xu G, Plomgaard P, Weigert C. Type 2 diabetes alters metabolic and transcriptional signatures of glucose and amino acid metabolism during exercise and recovery. Diabetologia. 2015 Aug;58(8):1845-54. Epub 2015 Jun 12. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huffman KM, Slentz CA, Bateman LA, Thompson D, Muehlbauer MJ, Bain JR, Stevens RD, Wenner BR, Kraus VB, Newgard CB, Kraus WE. Exercise-induced changes in metabolic intermediates, hormones, and inflammatory markers associated with improvements in insulin sensitivity. Diabetes Care. 2011 Jan;34(1):174-6. Epub 2010 Oct 4. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Huffman KM, Koves TR, Hubal MJ, Abouassi H, Beri N, Bateman LA, Stevens RD, Ilkayeva OR, Hoffman EP, Muoio DM, Kraus WE. Metabolite signatures of exercise training in human skeletal muscle relate to mitochondrial remodelling and cardiometabolic fitness. Diabetologia. 2014 Nov;57(11):2282-95. Epub 2014 Aug 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Kamaura M, Nishijima K, Takahashi M, Ando T, Mizushima S, Tochikubo O. Lifestyle modification in metabolic syndrome and associated changes in plasma amino acid profiles. Circ J. 2010 Nov;74(11):2434-40. Epub 2010 Sep 8. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kelly RS, Kelly MP, Kelly P. Metabolomics, physical activity, exercise and health: A review of the current evidence. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020 Dec 1;1866(12):165936. Epub 2020 Aug 19. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Khoramipour K, Sandbakk Ø, Keshteli AH, Gaeini AA, Wishart DS, Chamari K. Metabolomics in Exercise and Sports: A Systematic Review. Sports Med. 2022 Mar;52(3):547-583. Epub 2021 Oct 30. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lehmann R, Zhao X, Weigert C, Simon P, Fehrenbach E, Fritsche J, Machann J, Schick F, Wang J, Hoene M, Schleicher ED, Häring HU, Xu G, Niess AM. Medium chain acylcarnitines dominate the metabolite pattern in humans under moderate intensity exercise and support lipid oxidation. PLoS One. 2010 Jul 12;5(7):e11519. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lundsgaard AM, Fritzen AM, Kiens B. Molecular Regulation of Fatty Acid Oxidation in Skeletal Muscle during Aerobic Exercise. Trends Endocrinol Metab. 2018 Jan;29(1):18-30. Epub 2017 Dec 5. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCoin CS, Knotts TA, Adams SH. Acylcarnitines--old actors auditioning for new roles in metabolic physiology. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2015 Oct;11(10):617-25. Epub 2015 Aug 25. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mihalik SJ, Goodpaster BH, Kelley DE, Chace DH, Vockley J, Toledo FG, DeLany JP. Increased levels of plasma acylcarnitines in obesity and type 2 diabetes and identification of a marker of glucolipotoxicity. Obesity (Silver Spring). 2010 Sep;18(9):1695-700. Epub 2010 Jan 28. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Naja K, Hedaya L, Elashi AA, Rizzo M, Elrayess MA. N-Lactoyl Amino Acids: Emerging Biomarkers in Metabolism and Disease. Diabetes Metab Res Rev. 2025 Jul;41(5):e70060. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Nicholson K, Makovski TT, Nagyova I, van den Akker M, Stranges S. Strategies to improve health status among adults with multimorbidity: A scoping review. Maturitas. 2023 Jan;167:24-31. Epub 2022 Sep 14. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purdom T, Kravitz L, Dokladny K, Mermier C. Understanding the factors that effect maximal fat oxidation. J Int Soc Sports Nutr. 2018 Jan 12;15:3. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Rinaldo P, Cowan TM, Matern D. Acylcarnitine profile analysis. Genet Med. 2008 Feb;10(2):151-6. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rutkowsky JM, Knotts TA, Ono-Moore KD, McCoin CS, Huang S, Schneider D, Singh S, Adams SH, Hwang DH. Acylcarnitines activate proinflammatory signaling pathways. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2014 Jun 15;306(12):E1378-87. Epub 2014 Apr 22. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Sakaguchi CA, Nieman DC, Signini EF, Abreu RM, Catai AM. Metabolomics-Based Studies Assessing Exercise-Induced Alterations of the Human Metabolome: A Systematic Review. Metabolites. 2019 Aug 9;9(8):164. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schranner D, Kastenmüller G, Schönfelder M, Römisch-Margl W, Wackerhage H. Metabolite Concentration Changes in Humans After a Bout of Exercise: a Systematic Review of Exercise Metabolomics Studies. Sports Med Open. 2020 Feb 10;6(1):11. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schweda S, Munz B, Burgstahler C, Niess AM, Roesel I, Sudeck G, Krauss I. Proof of Concept of a 6-Month Person-Oriented Exercise Intervention ‘MultiPill-Exercise’ among Patients at Risk of or with Multiple Chronic Diseases: Results of a One-Group Pilot Trial. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2022 Aug 2;19(15):9469. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Skogvold HB, Rootwelt H, Reubsaet L, Elgstøen KBP, Wilson SR. Dried blood spot analysis with liquid chromatography and mass spectrometry: Trends in clinical chemistry. J Sep Sci. 2023 Aug;46(15):e2300210. Epub 2023 Jun 3. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian Q, Corkum AE, Moaddel R, Ferrucci L. Metabolomic profiles of being physically active and less sedentary: a critical review. Metabolomics. 2021 Jul 10;17(7):68. [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wolfe RR, Miller SL. Amino acid availability controls muscle protein metabolism. Diabetes Nutr Metab. 1999 Oct;12(5):322-8. [PubMed]

- Zeljkovic A, Mihajlovic M, Vujcic S, Guzonjic A, Munjas J, Stefanovic A, Kotur-Stevuljevic J, Rizzo M, Bogavac-Stanojevic N, Gagic J, Kostadinovic J, Vekic J. The Prospect of Genomic, Transcriptomic, Epigenetic and Metabolomic Biomarkers for The Personalized Prevention of Type 2 Diabetes and Cardiovascular Diseases. Curr Vasc Pharmacol. 2023;21(3):185-196. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

| Abbreviations | Metabolites |

| Carnitine-u, C0 | free / unconjugated carnitine |

| Cx | total carnitine |

| C2-u | acetylcarnitine |

| C3-DC+C4-OH-u | malonylcarnitine (C3-DC) + 3-hydroxybutyrylcarnitine (C4-OH) |

| C3-u | propionylcarnitine (C3) |

| C4-u | butyrylcarnitine + isobutyrylcarnitine (C4) |

| C4-DC+C5-OH-u | methylmalonylcarnitine (C4-DC) + 3-hydroxyisovalerylcarnitine (C5-OH) |

| C5-u | isovalerylcarnitine + methylbutyrylcarnitine (C5) |

| C5-DC+C6-OH-u | glutarylcarnitine (C5-DC) + 3-hydroxyhexanoylcarnitine (C6-OH) |

| C6-u | hexanoylcarnitine (C6) |

| C6-DC-u | methylglutarylcarnitine (C6-DC) |

| C8 | octanoylcarnitine (C8) |

| C10-u | decanoylcarnitine (C10) |

| C10:1-u | decenoylcarnitine (C10:1) |

| C12-u | dodecanoylcarnitine (C12) |

| C12:1-u | dodecenoylcarnitine (C12:1) |

| C14-u | tetradecanoylcarnitine (C14) |

| C14-OH-u | 3-hydroxytetradecanoylcarnitine (C14-OH) |

| C14:1-OH-u | 3-hydroxytetradecenoylcarnitine (C14:1-OH) |

| C14:1-u | tetradecenoylcarnitine (C14:1) |

| C14:2-u | tetradecadienoylcarnitine (C14:2) |

| C16-u | palmitoylcarnitine (C16) |

| C18-u | stearoylcarnitine (C18) |

| C18:1-u | oleoylcarnitine (C18:1) |

| C18:2-u | linoleoylcarnitine (C18:2) |

| C16-OH-u | 3-hydroxypalmitoylcarnitine (C16-OH) |

| C18:1-OH-u | 3-hydroxyoleoylcarnitine (C18:1-OH) |

| C18:2-OH-u | 3-hydroxylinoleoylcarnitine (C18:2-OH) |

| SC-ACs | short-chain acylcarnitines |

| MC-ACs | medium-chain acylcarnitines |

| LC-ACs | long-chain acylcarnitines |

| Cit | citrulline |

| Met | methionine |

| Phe | phenylalanine |

| Tyr | tyrosine |

| Val | valine |

| Xle | leucine + isoleucine |

| t | n | min | max | MD | ME | SD |

Δ (t0-t1) p |

Δ (t0-t2) p |

||

| amino acids | Cit (µmol/L) |

t0 | 6 | 15.7 | 35.7 | 27.05 | 26.78 | 7.34 | 10.37 .156 |

20.45 .031* |

| t1 | 6 | 27.8 | 55.6 | 36.60 | 37.15 | 10.10 | ||||

| t2 | 6 | 30.1 | 60.3 | 47.70 | 47.23 | 11.56 | ||||

| Met (µmol/L) |

t0 | 6 | 3.5 | 7.9 | 5.05 | 5.30 | 1.56 | 6.43 .016* |

13.43 .031* |

|

| t1 | 6 | 9.7 | 15.1 | 11.40 | 11.73 | 2.09 | ||||

| t2 | 6 | 12.4 | 32.1 | 15.35 | 18.73 | 7.47 | ||||

| Phe (µmol/L) |

t0 | 6 | 34.8 | 56.6 | 44.65 | 44.83 | 9.63 | 14.10 .031* |

33.27 .013* |

|

| t1 | 6 | 42.6 | 93.8 | 54.15 | 58.93 | 19.04 | ||||

| t2 | 6 | 58.8 | 112.9 | 68.10 | 78.10 | 21.11 | ||||

| Tyr (µmol/L) |

t0 | 6 | 39.9 | 53.5 | 47.95 | 47.83 | 5.36 | 13.07 .109 |

29.20 .031* |

|

| t1 | 6 | 50.2 | 70.7 | 62.70 | 60.90 | 7.91 | ||||

| t2 | 6 | 57.2 | 137.2 | 67.75 | 77.03 | 29.88 | ||||

| Val (µmol/L) |

t0 | 6 | 73.1 | 129.2 | 86.25 | 91.12 | 20.87 | 22.60 .016* |

59.17 .031* |

|

| t1 | 6 | 82.0 | 134.0 | 116.55 | 113.72 | 18.58 | ||||

| t2 | 6 | 99.0 | 236.4 | 141.55 | 150.28 | 45.54 | ||||

| Xle (µmol/L) |

t0 | 6 | 81.4 | 181.6 | 102.15 | 111.32 | 36.50 | 30.75 .109 |

97.63 .031* |

|

| t1 | 6 | 104.9 | 179.1 | 141.75 | 142.07 | 29.43 | ||||

| t2 | 6 | 109.9 | 389.1 | 181.80 | 208.95 | 94.96 | ||||

| (acyl)carnitines | Carnitine-u (µmol/L) |

t0 | 6 | 15.9 | 30.2 | 24.88 | 24.09 | 4.76 | -0.43 .844 |

-2.50 .313 |

| t1 | 6 | 19.3 | 31.2 | 22.68 | 23.66 | 4.59 | ||||

| t2 | 6 | 14.6 | 29.9 | 21.53 | 21.59 | 5.44 | ||||

| Cx (µmol/L) |

t0 | 6 | 20.2 | 37.1 | 31.20 | 30.28 | 5.54 | 5.75 .047* |

11.78 .031* |

|

| t1 | 6 | 30.7 | 42.4 | 35.15 | 36.03 | 5.24 | ||||

| t2 | 6 | 32.8 | 67.2 | 38.90 | 42.07 | 12.69 | ||||

| SC-ACs (µmol/L) |

t0 | 6 | 2.9 | 5.7 | 3.93 | 4.01 | 1.09 | 5.88 .016* |

13.07 .031* |

|

| t1 | 6 | 8.6 | 11.7 | 9.47 | 9.89 | 1.27 | ||||

| t2 | 6 | 12.4 | 32.8 | 14.26 | 17.08 | 7.87 | ||||

| MC-ACs (µmol/L) |

t0 | 6 | 0.1 | 0.3 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.06 | 0.01 .484 |

0.07 .313 |

|

| t1 | 6 | 0.1 | 0.2 | 0.20 | 0.18 | 0.06 | ||||

| t2 | 6 | 0.1 | 0.5 | 0.21 | 0.24 | 0.13 | ||||

| LC-ACs (µmol/L) |

t0 | 6 | 1.3 | 2.6 | 2.08 | 2.02 | 0.45 | 0.27 .031* |

1.10 .031* |

|

| t1 | 6 | 1.7 | 3.4 | 2.17 | 2.30 | 0.59 | ||||

| t2 | 6 | 2.3 | 4.0 | 3.10 | 3.12 | 0.61 |

| Δphysiological / clinical parameters (t0-t1) | statistics | AA concentration (t0) | AC concentration (t0) | ||||||||||

| Cit | Met | Phe | Tyr | Val | Xle | C0 | Cx | SC-ACs | MC-ACs | LC-ACs | |||

| sports | ΔrelVO2max [mL/kgxmin] | correlation [ρ] | -0.624 | -0.459 | -0.532 | -0.184 | -0.716 | -0.514 | 0.019 | 0.167 | 0.239 | -0.278 | 0.184 |

| p (2-sided) | 0.134 | 0.300 | 0.219 | 0.694 | 0.070 | 0.238 | 0.969 | 0.721 | 0.606 | 0.546 | 0.694 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| ΔPPO [W/kg] | correlation [ρ] |

-0.144 | 0.180 | -0.487 | 0.487 | -0.054 | 0.018 | -0.245 | -0.373 | 0.108 | -0.055 | 0.162 | |

| p (2-sided) | 0.758 | 0.699 | 0.268 | 0.268 | 0.908 | 0.969 | 0.596 | 0.41 | 0.818 | 0.908 | 0.728 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| body weight | ΔBMI [kg/m2] | correlation [ρ] |

-0.679 | 0.107 | -0.036 | 0.214 | -0.036 | 0.071 | -0.577 | -0.360 | -0.179 | -0.577 | -0.321 |

| p (2-sided) | 0.094 | 0.819 | 0.939 | 0.645 | 0.939 | 0.879 | 0.175 | 0.427 | 0.702 | 0.175 | 0.482 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| inflammation | ΔIL6 [ng/L] | correlation[ρ] | 0.643 | -0.250 | 0.071 | -0.143 | 0.036 | -0.214 | 0.342 | 0.414 | 0.643 | 0.306 | 0.464 |

| p (2-sided) | 0.119 | 0.589 | 0.879 | 0.760 | 0.939 | 0.645 | 0.452 | 0.355 | 0.119 | 0.504 | 0.294 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| ΔCRP [mg/dL] | correlation[ρ] | 0.000 | -0.071 | 0.536 | -0.429 | -0.071 | 0.143 | .775* | 0.595 | -0.321 | 0.270 | 0.179 | |

| p (2-sided) | 1.000 | 0.879 | 0.215 | 0.337 | 0.879 | 0.76 | 0.041 | 0.159 | 0.482 | 0.558 | 0.702 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Δfibrinogen [mg/dL] | correlation[ρ] | 0.257 | 0.086 | -0.029 | 0.429 | 0.029 | 0.086 | 0.261 | 0.174 | 0.429 | 0.116 | 0.486 | |

| p (2-sided) | 0.623 | 0.872 | 0.957 | 0.397 | 0.957 | 0.872 | 0.618 | 0.742 | 0.397 | 0.827 | 0.329 | ||

| n | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | ||

| diabetes | Δinsulin [pmol/L] | correlation[ρ] | 0.000 | 0.107 | -0.250 | 0.321 | 0.000 | 0.036 | 0.144 | -0.072 | 0.143 | 0.090 | 0.429 |

| p (2-sided) | 1.000 | 0.819 | 0.589 | 0.482 | 1.000 | 0.939 | 0.758 | 0.878 | 0.76 | 0.848 | 0.337 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| ΔHbA1c [%] | correlation[ρ] | 0.356 | -0.225 | 0.337 | -0.019 | 0.206 | -0.131 | 0.198 | 0.415 | 0.767* | -0.076 | 0.636 | |

| p (2-sided) | 0.434 | 0.628 | 0.460 | 0.968 | 0.658 | 0.78 | 0.67 | 0.354 | 0.044 | 0.872 | 0.125 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Δglucose [mg/dL] | correlation[ρ] | 0.757* | 0.090 | -0.180 | 0.000 | -0.234 | 0.054 | 0.500 | 0.291 | 0.126 | 0.836* | 0.018 | |

| p (2-sided) | 0.049 | 0.848 | 0.699 | 1.000 | 0.613 | 0.908 | 0.253 | 0.527 | 0.788 | 0.019 | 0.969 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| lipoprotein and fatty acid metabolism | Δcholesterol [mg/dL] | correlation[ρ] | 0.214 | -0.357 | 0.000 | 0.000 | -0.286 | -0.321 | 0.180 | 0.523 | 0.964*** | -0.018 | 0.571 |

| p (2-sided) | 0.645 | 0.432 | 1.000 | 1.000 | 0.535 | 0.482 | 0.699 | 0.229 | <.001 | 0.969 | 0.18 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Δtriglycerides [mg/dL] | correlation[ρ] | -0.018 | 0.270 | -0.450 | 0.468 | -0.198 | 0.126 | -0.073 | -0.245 | 0.000 | 0.209 | 0.018 | |

| p (2-sided) | 0.969 | 0.558 | 0.31 | 0.289 | 0.67 | 0.788 | 0.877 | 0.596 | 1 | 0.653 | 0.969 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| ΔLDL [mg/dL] | correlation[ρ] | 0.679 | -0.214 | -0.143 | -0.071 | 0.000 | -0.250 | 0.180 | 0.234 | 0.607 | 0.342 | 0.321 | |

| p (2-sided) | 0.094 | 0.645 | 0.76 | 0.879 | 1 | 0.589 | 0.699 | 0.613 | 0.148 | 0.452 | 0.482 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| ΔHDL [mg/dL] | correlation[ρ] | 0.144 | -0.108 | 0.360 | -0.018 | 0.559 | -0.036 | -0.018 | 0.027 | 0.324 | -0.309 | 0.505 | |

| p (2-sided) | 0.758 | 0.818 | 0.427 | 0.969 | 0.192 | 0.939 | 0.969 | 0.954 | 0.478 | 0.5 | 0.248 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| cardiovascular parameters | ΔdiastRR [mmHg] | correlation[ρ] | 0.072 | 0.414 | -0.360 | 0.577 | 0.342 | 0.198 | -0.927** | -0.855* | -0.090 | -0.191 | -0.541 |

| p (2-sided) | 0.878 | 0.355 | 0.427 | 0.175 | 0.452 | 0.67 | 0.003 | 0.014 | 0.848 | 0.682 | 0.21 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| ΔsysRR [mmHg] | correlation[ρ] | -0.324 | 0.667 | -0.036 | 0.757* | 0.631 | 0.523 | -0.873* | -0.964*** | -0.450 | -0.445 | -0.396 | |

| p (2-sided) | 0.478 | 0.102 | 0.939 | 0.049 | 0.129 | 0.229 | 0.01 | <.001 | 0.31 | 0.317 | 0.379 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| Δresting HR [bpm] | correlation[ρ] | -0.074 | -0.296 | -0.111 | -0.037 | 0.111 | -0.296 | 0.187 | 0.112 | 0.408 | -0.224 | 0.741 | |

| p (2-sided) | 0.875 | 0.518 | 0.812 | 0.937 | 0.812 | 0.518 | 0.688 | 0.811 | 0.364 | 0.629 | 0.057 | ||

| n | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 7 | ||

| t2 | n | min | max | MD | ME | SD | p | ||

| amino acids | Cit (µmol/L) | pre | 26 | 23.3 | 60.3 | 36.00 | 37.20 | 10.76 | |

| post | 26 | 23.5 | 90.2 | 32.60 | 36.03 | 13.70 | |||

| Δ | 26 | -24.6 | 29.9 | -0.85 | -1.17 | 11.40 | .464 | ||

| Met (µmol/L) | pre | 26 | 5.3 | 32.1 | 8.70 | 11.89 | 6.73 | ||

| post | 26 | 5.1 | 31.0 | 9.20 | 12.57 | 7.13 | |||

| Δ | 26 | -5.3 | 8.3 | 0.00 | 0.67 | 3.20 | .579 | ||

| Phe (µmol/L) | pre | 26 | 42.6 | 112.9 | 59.30 | 63.22 | 15.97 | ||

| post | 26 | 45.5 | 136.3 | 58.45 | 64.23 | 18.47 | |||

| Δ | 26 | -15.4 | 23.4 | -0.30 | 1.00 | 9.67 | .886 | ||

| Tyr (µmol/L) | pre | 26 | 38.9 | 137.2 | 62.90 | 65.99 | 20.07 | ||

| post | 26 | 37.6 | 117.8 | 64.85 | 69.34 | 18.76 | |||

| Δ | 26 | -19.4 | 37.5 | 0.75 | 3.35 | 11.32 | .210 | ||

| Val (µmol/L) | pre | 26 | 91.7 | 324.5 | 139.35 | 145.65 | 48.15 | ||

| post | 26 | 91.4 | 277.7 | 137.15 | 144.50 | 39.17 | |||

| Δ | 26 | -46.8 | 32.7 | 0.45 | -1.14 | 18.37 | .920 | ||

| Xle (µmol/L) | pre | 26 | 101.8 | 389.1 | 161.00 | 175.87 | 72.28 | ||

| post | 26 | 100.0 | 320.3 | 155.85 | 171.62 | 58.62 | |||

| Δ | 26 | -84.8 | 37.5 | -2.80 | -4.26 | 29.30 | .745 | ||

| (acyl-)carnitines | C0 (µmol/L) | pre | 26 | 14.6 | 58.1 | 30.64 | 32.57 | 11.77 | |

| post | 26 | 15.3 | 56.7 | 27.98 | 31.35 | 10.67 | |||

| Δ | 26 | -13.8 | 4.9 | -0.40 | -1.22 | 4.76 | .437 | ||

| Cx (µmol/L) | pre | 26 | 5.1 | 71.9 | 41.55 | 43.66 | 14.52 | ||

| post | 26 | 30.9 | 75.5 | 44.35 | 47.12 | 12.03 | |||

| Δ | 26 | -12.4 | 52.8 | 3.20 | 3.46 | 11.35 | .070 | ||

| SC-ACs (µmol/L) | pre | 26 | 2.6 | 32.8 | 8.12 | 10.16 | 7.29 | ||

| post | 26 | 3.6 | 35.0 | 10.55 | 12.36 | 7.06 | |||

| Δ | 26 | -3.2 | 8.1 | 2.19 | 2.20 | 2.27 | <.001** | ||

| MC-ACs (µmol/L) | pre | 26 | 0.1 | 0.6 | 0.21 | 0.23 | 0.12 | ||

| post | 26 | 0.1 | 0.8 | 0.23 | 0.26 | 0.14 | |||

| Δ | 26 | -0.1 | 0.2 | 0.03 | 0.03 | 0.06 | .027* | ||

| LC-ACs (µmol/L) | pre | 26 | 1.7 | 4.0 | 2.95 | 2.96 | 0.67 | ||

| post | 26 | 1.9 | 5.0 | 2.98 | 3.13 | 0.90 | |||

| Δ | 26 | -0.9 | 1.7 | 0.15 | 0.17 | 0.54 | .147 |

| Δphysiological / clinical parameters (t0-t2) | statistics | amino acid mobilization during acute bout of exercise at t2 | (acyl-)carnitine mobilization during acute bout of exercise at t2 | ||||||||||

| Cit | Met | Phe | Tyr | Val | Xle | C0 | Cx |

SC- ACs |

MC-ACs |

LC- ACs |

|||

| sports | ΔrelVO2max [mL/kgxmin] | correlation [ρ] | -0.047 | 0.012 | -0.002 | -0.034 | 0.014 | -0.087 | -0.079 | -0.040 | 0.230 | -0.170 | 0.124 |

| p (2-sided) | 0.819 | 0.955 | 0.993 | 0.867 | 0.945 | 0.672 | 0.703 | 0.846 | 0.258 | 0.407 | 0.547 | ||

| n | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | ||

| ΔPPO [W/kg] | correlation [ρ] | 0.024 | -0.073 | -0.170 | -0.077 | -0.121 | -0.158 | -0.001 | -0.011 | 0.044 | -0.480* | 0.113 | |

| p (2-sided) | 0.910 | 0.735 | 0.427 | 0.719 | 0.573 | 0.460 | 0.997 | 0.960 | 0.838 | 0.018 | 0.599 | ||

| n | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | 24 | ||

| body weight | ΔBMI [kg/m2] | correlation [ρ] | -0.090 | -0.324 | -0.080 | 0.015 | -0.169 | -0.032 | 0.017 | -0.028 | -0.266 | -0.124 | -0.240 |

| p (2-sided) | 0.663 | 0.107 | 0.699 | 0.941 | 0.409 | 0.875 | 0.935 | 0.893 | 0.188 | 0.545 | 0.238 | ||

| n | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | 26 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).