Submitted:

02 May 2025

Posted:

07 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Distant TeV Blazars: 1ES 0414+009 and 1ES 1959+650

2.1. 1ES 0414+009

2.2. 1ES 1959+650

3. Multiwavelength SED Fitting of Jetted AGNs

3.1. SED Leptonic Modelling

3.2. SED Lepto-Hadronic Modelling

4. Results and Discussions

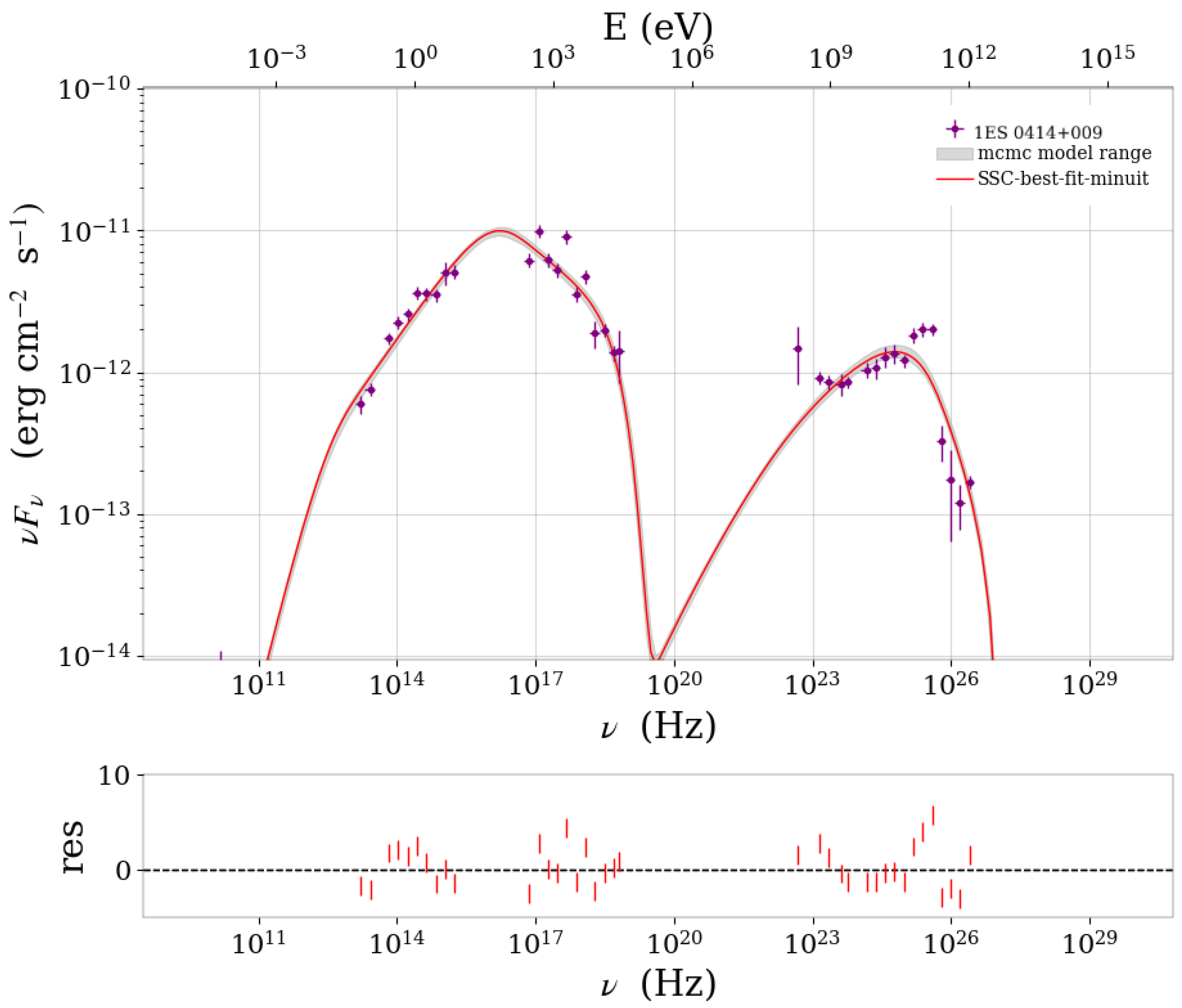

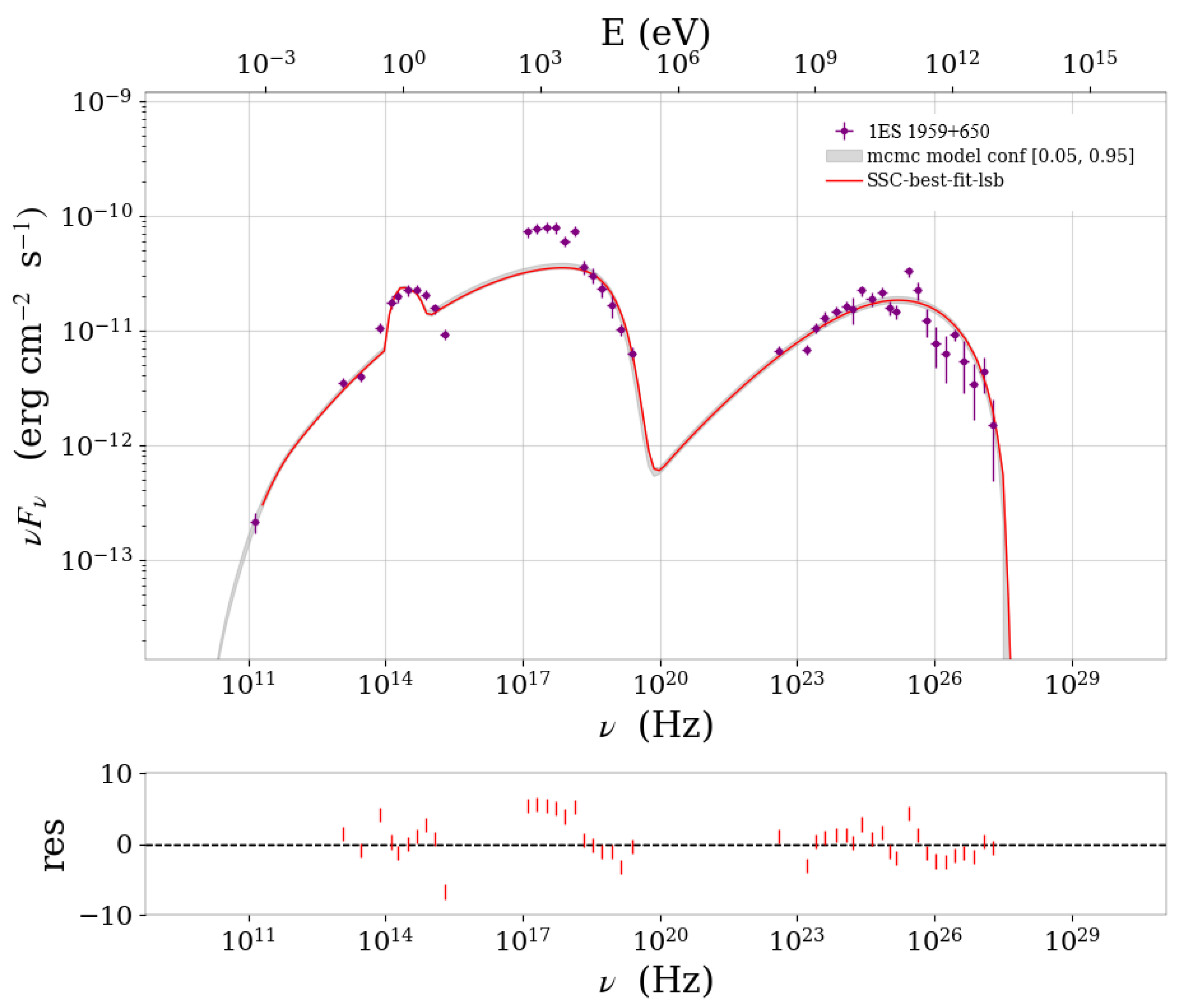

4.1. SSC SED Fitting

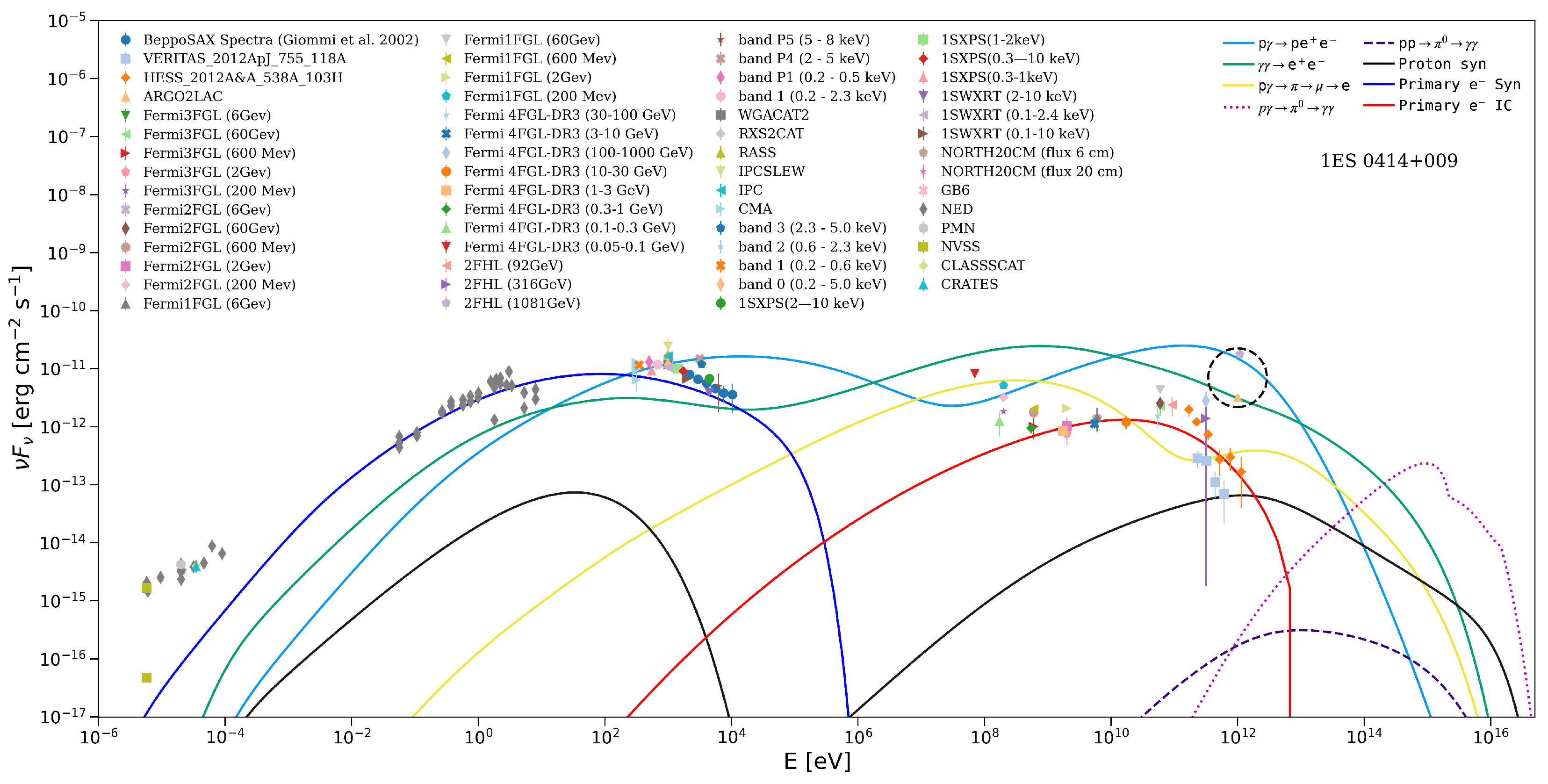

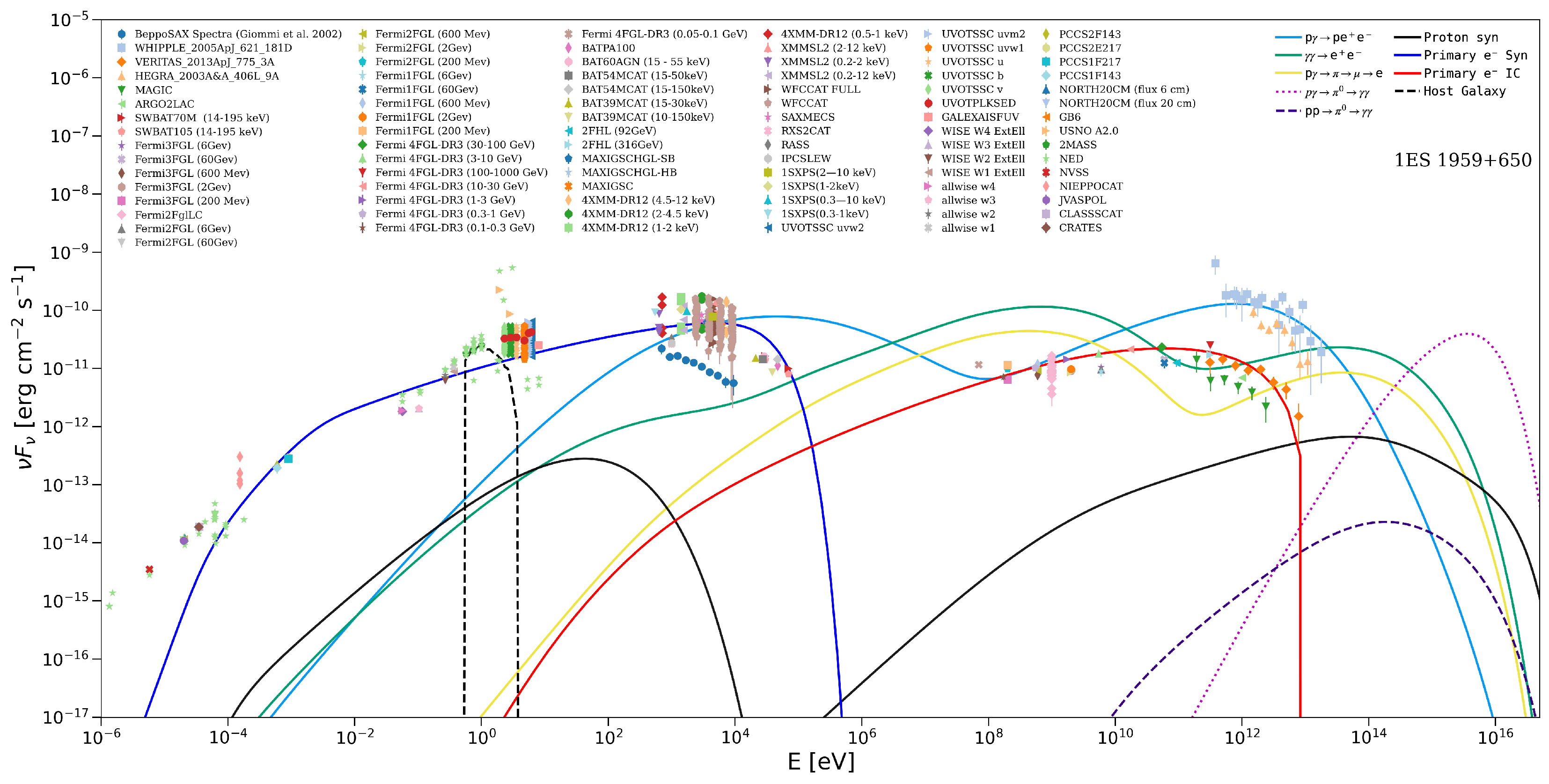

4.2. Lepto-Hadronic SED Modelling

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Urry, C.M.; Padovani, P. Unified Schemes for Radio-Loud Active Galactic Nuclei. 1995, 107, 803, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/9506063]. [CrossRef]

- Wills, B.J.; Wills, D.; Breger, M.; Antonucci, R.R.J.; Barvainis, R. A Survey for High Optical Polarization in Quasars with Core-dominant Radio Structure: Is There a Beamed Optical Continuum? 1992, 398, 454. [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, G.; Tavecchio, F.; Foschini, L.; Ghirlanda, G.; Maraschi, L.; Celotti, A. General physical properties of bright Fermi blazars. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2010, 402, 497–518, [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-pdf/402/1/497/18583477/mnras0402-0497.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, S.J.; Chen, L.; Wu, Q. CONSTRAINTS ON THE MINIMUM ELECTRON LORENTZ FACTOR AND MATTER CONTENT OF JETS FOR A SAMPLE OF BRIGHT FERMI BLAZARS. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2014, 215, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.H.; Yang, J.H.; Liu, Y.; Luo, G.Y.; Lin, C.; Yuan, Y.H.; Xiao, H.B.; Zhou, A.Y.; Hua, T.X.; Pei, Z.Y. THE SPECTRAL ENERGY DISTRIBUTIONS OF FERMI BLAZARS. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2016, 226, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Fan, J.H.; Liu, Y.; Tuo, M.X.; Pei, Z.Y.; Yang, W.X.; Yuan, Y.H.; He, S.L.; Wang, S.H.; Wang, X.C.; et al. The Spectral Energy Distributions for 4FGL Blazars. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2022, 262, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, G.; Wang, J. The Hadronic Origin of the Hard Gamma-Ray Spectrum from Blazar 1ES 1101-232. 2014, 783, 108, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1401.3970]. [CrossRef]

- Abdo, A.A.; Ackermann, M.; Agudo, I.; Ajello, M.; Aller, H.D.; Aller, M.F.; Angelakis, E.; Arkharov, A.A.; Axelsson, M.; Bach, U.; et al. THE SPECTRAL ENERGY DISTRIBUTION OF FERMI BRIGHT BLAZARS. The Astrophysical Journal 2010, 716, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.X.; Zheng, Y.G.; Zhu, K.R.; Kang, S.J. The Intrinsic Properties of Multiwavelength Energy Spectra for Fermi Teraelectronvolt Blazars. The Astrophysical Journal 2021, 915, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, R.X.; Zheng, Y.G.; Zhu, K.R.; Kang, S.J.; Li, X.P. Modeling the Multiwavelength Spectral Energy Distributions of the Fermi-4LAC Bright Flat-spectrum Radio Quasars. The Astrophysical Journal 2024, 962, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, H.B.; Wang, H.Q.; Xue, R.; Peng, F.K.; Wang, Z.R. The physical properties of Fermi-4LAC low-synchrotron-peaked BL Lac objects. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2024, 528, 7587–7599, [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-pdf/528/4/7587/58385529/stae522.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavecchio, F.; Ghisellini, G.; Ghirlanda, G.; Foschini, L.; Maraschi, L. TeV BL Lac objects at the dawn of the Fermi era. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2010, 401, 1570–1586, [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-pdf/401/3/1570/3811367/mnras0401-1570.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Y.G.; Long, G.B.; Yang, C.Y.; Bai, J.M. Verification of the diffusive shock acceleration in Mrk 501. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2018, 478, 3855–3861, [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-pdf/478/3/3855/25077266/sty1323.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dermer, C.D.; Schlickeiser, R. Model for the High-Energy Emission from Blazars. 1993, 416, 458. [CrossRef]

- Sikora, M.; Begelman, M.C.; Rees, M.J. Comptonization of Diffuse Ambient Radiation by a Relativistic Jet: The Source of Gamma Rays from Blazars? 1994, 421, 153. [CrossRef]

- Aharonian, F.A. TeV gamma rays from BL Lac objects due to synchrotron radiation of extremely high energy protons. 2000, 5, 377–395, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/0003159]. [CrossRef]

- Mücke, A.; Protheroe, R.J.; Engel, R.; Rachen, J.P.; Stanev, T. BL Lac objects in the synchrotron proton blazar model. Astroparticle Physics 2003, 18, 593–613, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/0206164]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petropoulou, M. The role of hadronic cascades in GRB models of efficient neutrino production. 2014, 442, 3026–3036, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1405.7669]. [CrossRef]

- Mannheim, K.; Biermann, P.L. Gamma-ray flaring of 3C 279 : a proton-initiated cascade in the jet ? 1992, 253, L21–L24.

- Mannheim, K. The proton blazar. 1993, 269, 67–76, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/9302006]. [CrossRef]

- Pohl, M.; Schlickeiser, R. On the conversion of blast wave energy into radiation in active galactic nuclei and gamma-ray bursts. 2000, 354, 395–410, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/9911452]. [CrossRef]

- Atoyan, A.; Dermer, C.D. High-Energy Neutrinos from Photomeson Processes in Blazars. 2001, 87, 221102, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/0108053]. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Liang, E.W.; Zhang, S.N.; Bai, J.M. RADIATION MECHANISMS AND PHYSICAL PROPERTIES OF GeV–TeV BL Lac OBJECTS. The Astrophysical Journal 2012, 752, 157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, J.; Xiao, H.; Yang, W.; Zhang, L.; Strigachev, A.A.; Bachev, R.S.; Yang, J. Characterizing the Emission Region Properties of Blazars. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2023, 268, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.D.; Znajek, R.L. Electromagnetic extraction of energy from Kerr black holes. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 1977, 179, 433–456, [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/articlepdf/179/3/433/9333653/mnras179-0433.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blandford, R.D.; Payne, D.G. Hydromagnetic flows from accretion discs and the production of radio jets. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 1982, 199, 883–903, [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-pdf/199/4/883/2880142/mnras199-0883.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maraschi, L.; Tavecchio, F. The Jet-Disk Connection and Blazar Unification. The Astrophysical Journal 2003, 593, 667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, X.Z.; Yang, H.Y.; Zheng, Y.G.; Kang, S.J. The Energy Budget in the Jet of High-frequency Peaked BL Lacertae Objects 2024. [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2406.01046]. [CrossRef]

- Sironi, L.; Petropoulou, M.; Giannios, D. Relativistic jets shine through shocks or magnetic reconnection? Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2015, 450, 183–191, [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-pdf/450/1/183/18504917/stv641.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lobanov, A.P. Ultracompact jets in AGN. Astron. Astrophys. 1998, 330, 79, [astro-ph/9712132]. [Google Scholar]

- Zamaninasab, M.; Clausen-Brown, E.; Savolainen, T.; Tchekhovskoy, A. Dynamically important magnetic fields near accreting supermassive black holes. t 2014, 510, 126–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, G.; Celotti, A.; Fossati, G.; Maraschi, L.; Comastri, A. A theoretical unifying scheme for gamma-ray bright blazars. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 1998, 301, 451–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavecchio, F.; Maraschi, L.; Ghisellini, G. Constraints on the Physical Parameters of TeV Blazars. The Astrophysical Journal 1998, 509, 608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tavecchio, F.; Ghisellini, G.; Bonnoli, G.; Ghirlanda, G. Constraining the location of the emitting region in Fermi blazars through rapid γ-ray variability. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters 2010, 405, L94–L98, [https://academic.oup.com/mnrasl/articlepdf/405/1/L94/54673273/mnrasl_405_1_l94.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sol, H.; Zech, A. Blazars at Very High Energies: Emission Modelling. Galaxies 2022, 10, 105, [arXiv:astroph.HE/2211.03580]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelner, S.R.; Aharonian, F.A. Energy spectra of gamma rays, electrons, and neutrinos produced at interactions of relativistic protons with low energy radiation. 2008, 78, 034013, [arXiv:astro-ph/0803.0688]. [CrossRef]

- Karavola, D.; Petropoulou, M. A closer look at the electromagnetic signatures of Bethe-Heitler pair production process in blazars. 2024, 2024, 006, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2401.05534]. [CrossRef]

- Gursky, H.; Bradt, H.; Doxsey, R.; Schwartz, D.; Schwarz, J.; Dower, R.; Fabbiano, G.; Griffiths, R.E.; Johnston, M.; Leach, R.; et al. Measurements of X-ray source positions by the scanning modulation collimator on HEAO 1. 1978, 223, 973–978. [CrossRef]

- Giacconi, R.; Branduardi, G.; Briel, U.; Epstein, A.; Fabricant, D.; Feigelson, E.; Forman, W.; Gorenstein, P.; Grindlay, J.; Gursky, H.; et al. The Einstein (HEAO 2) X-ray Observatory. 1979, 230, 540–550. [CrossRef]

- Halpern, J.P.; Chen, V.S.; Madejski, G.M.; Chanan, G.A. The Redshift of the X-ray Selected BL Lacertae Object H0414+009. 1991, 101, 818. [CrossRef]

- Falomo, R.; Carangelo, N.; Treves, A. Host galaxies and black hole masses of low- and high-luminosity radio-loud active nuclei. 2003, 343, 505–511, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/0304190]. [CrossRef]

- Padovani, P.; Giommi, P. A sample-oriented catalogue of BL Lacertae objects. 1995, 277, 1477–1490, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/9511065]. [CrossRef]

- Aharonian, F.A.; Akhperjanian, A.G.; Barrio, J.A.; Bernlöhr, K.; Bojahr, H.; Calle, I.; Contreras, J.L.; Cortina, J.; Daum, A.; Deckers, T.; et al. HEGRA search for TeV emission from BL Lacertae objects. 2000, 353, 847–852, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/9903455]. [CrossRef]

- Costamante, L.; Ghisellini, G. TeV candidate BL Lac objects. 2002, 384, 56–71, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/0112201]. [CrossRef]

- Aharonian, F.; Akhperjanian, A.G.; Bazer-Bachi, A.R.; Beilicke, M.; Benbow, W.; Berge, D.; Bernlöhr, K.; Boisson, C.; Bolz, O.; Borrel, V.; et al. A low level of extragalactic background light as revealed by γ-rays from blazars. t 2006, 440, 1018–1021, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/0508073]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volpe, F.; Ohm, S.; Hauser, M.; Kaufmann, S.; Gérard, L.; Costamante, L.; Fegan, S.; Ajello, M. Discovery of VHE and HE emission from the blazar 1ES 0414+009 with H.E.S.S and Fermi-LAT. arXiv e-prints 2011, p. arXiv:1105.5114, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1105.5114]. [CrossRef]

- H. E. S. S. Collaboration.; Abramowski, A.; Acero, F.; Aharonian, F.; Akhperjanian, A.G.; Anton, G.; Balzer, A.; Barnacka, A.; Barres de Almeida, U.; Becherini, Y.; et al. Discovery of hard-spectrum γ-ray emission from the BL Lacertae object 1ES 0414+009. 2012, 538, A103, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1201.2044]. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Zhao, X.; Cao, Z. TeV Blazars as the Sources of Ultra High Energy Cosmic Rays. International Journal of Astronomy and Astrophysics 2014, 4, 499–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acciari, V.A.; Ansoldi, S.; Antonelli, L.A.; Engels, A.A.; Asano, K.; Baack, D.; Babić, A.; Banerjee, B.; Barres de Almeida, U.; Barrio, J.A.; et al. New Hard-TeV Extreme Blazars Detected with the MAGIC Telescopes. s 2020, 247, 16, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1911.06680]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piner, B.G.; Edwards, P.G. First-Epoch VLBA Imaging of 20 New TeV Blazars. Astrophys. J. 2014, 797, 25, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1410.0730]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pueschel, E. The Extragalactic Background Light: Constraints from TeV Blazar Observations. PoS 2017, ICRC2017, 1107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elvis, M.; Plummer, D.; Schachter, J.; Fabbiano, G. The Einstein Slew Survey. s 1992, 80, 257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schachter, J.F.; Stocke, J.T.; Perlman, E.; Elvis, M.; Remillard, R.; Granados, A.; Luu, J.; Huchra, J.P.; Humphreys, R.; Urry, C.M.; et al. Ten New BL Lacertae Objects Discovered by an Efficient X-Ray/Radio/Optical Technique. 1993, 412, 541. [CrossRef]

- Nishiyama, T.; Chamoto, N.; Chikawa, M. in Proc. of the 26th ICRC. Salt Lake City 1999, 3, 370.

- Holder, J.; Bond, I.H.; Boyle, P.J.; Bradbury, S.M.; Buckley, J.H.; Carter-Lewis, D.A.; Cui, W.; Dowdall, C.; Duke, C.; de la Calle Perez, I.; et al. Detection of TeV Gamma Rays from the BL Lacertae Object 1ES 1959+650 with the Whipple 10 Meter Telescope. The Astrophysical Journal 2002, 583, L9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horns, D. Multi-wavelength Observations of the TeV Blazars Mkn 421, 1ES1959+650, and H1426+428 with the HEGRA Cherenkov Telescopes and the RXTE X-ray Satellite. In Proceedings of the High Energy Blazar Astronomy; Takalo, L.O.; Valtaoja, E., Eds., 2003, Vol. 299, Astronomical Society of the Pacific Conference Series, p. 13, [arXiv:astro-ph/astro-ph/0209454]. [CrossRef]

- Aharonian, F.; Akhperjanian, A.; Beilicke, M.; Bernlöhr, K.; Börst, H.G.; Bojahr, H.; Bolz, O.; Coarasa, T.; Contreras, J.L.; Cortina, J.; et al. Detection of TeV gamma-rays from the BL Lac 1ES 1959+650 in its low states and during a major outburst in 2002. 2003, 406, L9–L13. [CrossRef]

- Kapanadze, B.; Dorner, D.; Romano, P.; Vercellone, S.; Tabagari, L. The TeV blazar 1ES 1959+650 - a short review. 04 2018, p. 033. [CrossRef]

- Aliu, E.; Archambault, S.; Arlen, T.; Aune, T.; Beilicke, M.; Benbow, W.; Bird, R.; Böttcher, M.; Bouvier, A.; Bugaev, V.; et al. Multiwavelength Observations and Modeling of 1ES 1959+650 in a Low Flux State. 2013, 775, 3, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1307.6772]. [CrossRef]

- Aliu, E.; Archambault, S.; Arlen, T.; Aune, T.; Barnacka, A.; Beilicke, M.; Benbow, W.; Berger, K.; Bird, R.; Bouvier, A.; et al. Investigating Broadband Variability of the TeV Blazar 1ES 1959+650. 2014, 797, 89, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1412.1031]. [CrossRef]

- Kapanadze, B.; Romano, P.; Vercellone, S.; Kapanadze, S.; Mdzinarishvili, T.; Kharshiladze, G. The long-term Swift observations of the high-energy peaked BL Lacertae source 1ES 1959+650. 2016, 457, 704–722. [CrossRef]

- Kapanadze, B.; Dorner, D.; Vercellone, S.; Romano, P.; Kapanadze, S.; Mdzinarishvili, T. A recent strong X-ray flaring activity of 1ES 1959+650 with possibly less efficient stochastic acceleration. 2016, 461, L26–L31. [CrossRef]

- Kapanadze, B.; Dorner, D.; Vercellone, S.; Romano, P.; Hughes, P.; Aller, M.; Aller, H.; Reynolds, M.; Kapanadze, S.; Tabagari, L. The second strong X-ray flare and multifrequency variability of 1ES 1959+650 in 2016 January-August. 2018, 473, 2542–2564. [CrossRef]

- Shukla, A.; Chitnis, V.R.; Singh, B.B.; Acharya, B.S.; Anupama, G.C.; Bhattacharjee, P.; Britto, R.J.; Mannheim, K.; Prabhu, T.P.; Saha, L.; et al. MULTI-FREQUENCY, MULTI-EPOCH STUDY OF Mrk 501: HINTS FOR A TWO-COMPONENT NATURE OF THE EMISSION. The Astrophysical Journal 2014, 798, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tramacere, A.; Giommi, P.; Perri, M.; Verrecchia, F.; Tosti, G. Swift observations of the very intense flaring activity of Mrk 421 during 2006. I. Phenomenological picture of electron acceleration and predictions for MeV/GeV emission. 2009, 501, 879–898, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/0901.4124]. [CrossRef]

- Tramacere, A.; Massaro, E.; Taylor, A.M. Stochastic Acceleration and the Evolution of Spectral Distributions in Synchro-Self-Compton Sources: A Self-consistent Modeling of Blazars’ Flares. 2011, 739, 66, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1107.1879]. [CrossRef]

- Tramacere, A. JetSeT: Numerical modeling and SED fitting tool for relativistic jets. Astrophysics Source Code Library, record ascl:2009.001, 2020.

- Dominguez, A.; et al. Extragalactic Background Light Inferred from AEGIS Galaxy SED-type Fractions. Mon. Not. Roy. Astron. Soc. 2011, 410, 2556, [arXiv:astro-ph.CO/1007.1459]. [CrossRef]

- Franceschini, A.; Rodighiero, G.; Vaccari, M. The extragalactic optical-infrared background radiations, their time evolution and the cosmic photon-photon opacity. Astron. Astrophys. 2008, 487, 837, [arXiv:astro-ph/0805.1841]. [CrossRef]

- Finke, J.D.; Razzaque, S.; Dermer, C.D. Modeling the Extragalactic Background Light from Stars and Dust. Astrophys. J. 2010, 712, 238–249, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/0905.1115]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, G.; Tavecchio, F.; Maraschi, L.; Celotti, A.; Sbarrato, T. The power of relativistic jets is larger than the luminosity of their accretion disks. Nature 2014, 515, 376, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1411.5368]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- and.; and. The gamma-ray Doppler factor determinations for a Fermi blazar sample. Research in Astronomy and Astrophysics 2013, 13, 259. [CrossRef]

- Nalewajko, K. The brightest gamma-ray flares of blazars. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2013, 430, 1324–1333, [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-pdf/430/2/1324/9383405/sts711.pdf]]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dembinski, H.; Ongmongkolkul, P.; Deil, C.; Schreiner, H.; Feickert, M.; Burr, C.; Watson, J.; Rost, F.; Pearce, A.; Geiger, L.; et al. scikit-hep/iminuit, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Virtanen, P.; Gommers, R.; Oliphant, T.E.; Haberland, M.; Reddy, T.; Cournapeau, D.; Burovski, E.; Peterson, P.; Weckesser, W.; Bright, J.; et al. SciPy 1.0: Fundamental Algorithms for Scientific Computing in Python. Nature Methods 2020, 17, 261–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foreman-Mackey, D.; Hogg, D.W.; Lang, D.; Goodman, J. emcee: The MCMC Hammer. 2013, 125, 306, [arXiv:astro-ph.IM/1202.3665]. [CrossRef]

- Ghisellini, G. Electron—positron pairs in blazar jets and γ-ray loud radio galaxies. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society: Letters 2012, 424, L26–L30, [https://academic.oup.com/mnrasl/articlepdf/424/1/L26/54665037/mnrasl_424_1_l26.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klinger, M.; Rudolph, A.; Rodrigues, X.; Yuan, C.; de Clairfontaine, G.F.; Fedynitch, A.; Winter, W.; Pohl, M.; Gao, S. AM3: An Open-source Tool for Time-dependent Lepto-hadronic Modeling of Astrophysical Sources. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 2024, 275, 4, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2312.13371]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hümmer, S.; Rüger, M.; Spanier, F.; Winter, W. SIMPLIFIED MODELS FOR PHOTOHADRONIC INTERACTIONS IN COSMIC ACCELERATORS. The Astrophysical Journal 2010, 721, 630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giommi, P.; Capalbi, M.; Fiocchi, M.; Memola, E.; Perri, M.; Piranomonte, S.; Rebecchi, S.; Massaro, E. A catalog of 157 X-ray spectra and 84 spectral energy distributions of blazars observed with BeppoSAX. arXiv preprint astro-ph/0209596 2002.

- Aliu, E.; Archambault, S.; Arlen, T.; Aune, T.; Beilicke, M.; Benbow, W.; Boettcher, M.; Bouvier, A.; Bugaev, V.; Cannon, A.; et al. Multiwavelength observations of the AGN 1ES 0414+ 009 with VERITAS, Fermi-LAT, Swift-XRT, and MDM. The Astrophysical Journal 2012, 755, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramowski, A.; Acero, F.; Aharonian, F.; Akhperjanian, A.; Anton, G.; Balzer, A.; Barnacka, A.; De Almeida, U.B.; Becherini, Y.; Becker, J.; et al. Discovery of hard-spectrum γ-ray emission from the BL Lacertae object 1ES 0414+ 009. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2012, 538, A103. [Google Scholar]

- Bartoli, B.; Bernardini, P.; Bi, X.J.; Bolognino, I.; Branchini, P.; Budano, A.; Calabrese Melcarne, A.K.; Camarri, P.; Cao, Z.; Cardarelli, R.; et al. TeV GAMMA-RAY SURVEY OF THE NORTHERN SKY USING THE ARGO-YBJ DETECTOR. The Astrophysical Journal 2013, 779, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdo, A.A.; Ackermann, M.; Ajello, M.; Allafort, A.; Antolini, E.; Atwood, W.; Axelsson, M.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; Barbiellini, G.; et al. Fermi large area telescope first source catalog. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2010, 188, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nolan, P.L.; Abdo, A.; Ackermann, M.; Ajello, M.; Allafort, A.; Antolini, E.; Atwood, W.; Axelsson, M.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; et al. Fermi large area telescope second source catalog. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2012, 199, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acero, F.; Ackermann, M.; Ajello, M.; Albert, A.; Atwood, W.; Axelsson, M.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; Barbiellini, G.; Bastieri, D.; et al. Fermi large area telescope third source catalog. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2015, 218, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdollahi, S.; Acero, F.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; Bastieri, D.; Bellazzini, R.; Berenji, B.; Berretta, A.; Bissaldi, E.; Blandford, R.D.; et al. Incremental fermi large area telescope fourth source catalog. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2022, 260, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ackermann, M.; Ajello, M.; Atwood, W.B.; Baldini, L.; Ballet, J.; Barbiellini, G.; Bastieri, D.; Gonzalez, J.B.; Bellazzini, R.; Bissaldi, E.; et al. 2FHL: the second catalog of hard Fermi-LAT sources. The Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series 2016, 222, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusumano, G.; La Parola, V.; Segreto, A.; Ferrigno, C.; Maselli, A.; Sbarufatti, B.; Romano, P.e.; Chincarini, G.; Giommi, P.; Masetti, N.; et al. The Palermo Swift-BAT hard X-ray catalogue-III. Results after 54 months of sky survey. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2010, 524, A64. [Google Scholar]

- Wright, A.E.; Griffith, M.R.; Troup, E.; Hunt, A.J.; Burke, B. The Parkes-MIT-NRAO (PMN) Surveys. VIII: Source Catalog for the Zenith Survey (–37.0< d<–29.0).

- Boller, T.; Freyberg, M.; Trümper, J.; Haberl, F.; Voges, W.; Nandra, K. Second ROSAT all-sky survey (2RXS) source catalogue. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2016, 588, A103. [Google Scholar]

- Voges, W.; Aschenbach, B.; Boller, T.; Braeuninger, H.; Briel, U.; Burkert, W.; Dennerl, K.; Englhauser, J.; Gruber, R.; Haberl, F.; et al. The ROSAT all-sky survey bright source catalogue. arXiv preprint astro-ph/9909315 1999.

- Levine, A.; Lang, F.; Lewin, W.; Primini, F.; Dobson, C.; Doty, J.; Hoffman, J.; Howe, S.; Scheepmaker, A.; Wheaton, W.; et al. The HEAO 1 A-4 catalog of high-energy X-ray sources. Astrophysical Journal Supplement Series (ISSN 0067-0049), vol. 54, April 1984, p. 581-617. 1984, 54, 581–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, P.A.; et al. . 1SXPS: A Swift XRT Point Source Catalog. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 2014, 210, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cusumano, G.; et al. The Palermo Swift-BAT hard X-ray catalogue. Astron. Astrophys. 2010, 524, A64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daniel, M.; Badran, H.; Bond, I.; Boyle, P.; Bradbury, S.; Buckley, J.; Carter-Lewis, D.; Catanese, M.; Celik, O.; Cogan, P.; et al. Spectrum of very high energy gamma-rays from the blazar 1ES 1959+ 650 during flaring activity in 2002. The Astrophysical Journal 2005, 621, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aleksić, J.; Ansoldi, S.; Antonelli, L.A.; et al. The major upgrade of the MAGIC telescopes, Part I: The hardware improvements and the commissioning of the system. Astroparticle Physics 2016, 72, 61–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, B.; Bernardini, P.; Bi, X.J.; et al. ARGO-YBJ Observation of the Blazar Markarian 421 during the 2008 July Flaring Episode. The Astrophysical Journal 2015, 798, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, W.H.; Tueller, J.; Markwardt, C.B.; et al. The 70 Month Swift-BAT All-sky Hard X-Ray Survey. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 2013, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oh, K.; Koss, M.; Markwardt, C.B.; et al. The 105-Month Swift-BAT All-sky Hard X-Ray Survey. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 2018, 235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segreto, A.; Cusumano, G. The Fourth Palermo Swift-BAT Hard X-Ray Catalogue: 100 months of survey. Astrophys. J. Suppl. 2013, 207. [Google Scholar]

- Cusumano, G.; La Parola, V.; Segreto, A.; et al. The Palermo Swift-BAT Hard X-Ray Catalogue. II. Results after 39 months of survey. Astron. Astrophys. 2010, 511. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuoka, M.; Kawasaki, K.; Ueno, S.; et al. The MAXI Mission on the ISS: Science and Instruments for Monitoring All-Sky X-Ray Images. Publ. Astron. Soc. Jpn. 2009, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webb, N.A.; Coriat, M.; Traulsen, I.; et al. 4XMM-DR9: The latest XMM-Newton serendipitous source catalogue. Astron. Nachr. 2020, 341. [Google Scholar]

- Saxton, R.D.; Read, A.M.; Esquej, P.; et al. The XMM-Newton Slew Survey: XMMSL1. Astron. Astrophys. 2008, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boella, G.; Butler, R.; Perola, G.C.; et al. BeppoSAX: The Wide Field Cameras. Astron. Astrophys. Suppl. 1997, 122. [Google Scholar]

- Acciari, M.C.V.; Ansoldi, S.; Antonelli, L.; Arbet Engels, A.; Babić, A.; Banerjee, B.; Barres de Almeida, U.; Barrio, J.; Becerra González, J.; Bednarek, W.; et al. An intermittent extreme BL Lac: MWL study of 1ES 2344+ 514 in an enhanced state. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2020, 496, 3912–3928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.K.; Bisschoff, B.; van Soelen, B.; Tolamatti, A.; Marais, J.P.; Meintjes, P.J. Long-term multiwavelength view of the blazar 1ES 1218+304. Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society 2019, 489, 5076–5086, [https://academic.oup.com/mnras/article-pdf/489/4/5076/30047576/stz2521.pdf]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aliu, E.; Archambault, S.; Arlen, T.; Aune, T.; Beilicke, M.; Benbow, W.; Böttcher, M.; Bouvier, A.; Bugaev, V.; Cannon, A.; et al. Multiwavelength Observations of the AGN 1ES 0414+009 with VERITAS, Fermi-LAT, Swift-XRT, and MDM. 2012, 755, 118, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/1206.4080]. [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, X.; Paliya, V.S.; Garrappa, S.; Omeliukh, A.; Franckowiak, A.; Winter, W. Leptohadronic multi-messenger modeling of 324 gamma-ray blazars. Astronomy & Astrophysics 2024, 681, A119. [Google Scholar]

- Wani, K.; Gaur, H.; Patil, M. X-Ray Studies of Blazar 1ES 1959+ 650 Using Swift and XMM-Newton Satellite. The Astrophysical Journal 2023, 951, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartoli, B.; Bernardini, P.; Bi, X.; Bolognino, I.; Branchini, P.; Budano, A.; Melcarne, A.C.; Camarri, P.; Cao, Z.; Cardarelli, R.; et al. TeV gamma-ray survey of the northern sky using the ARGO-YBJ detector. The Astrophysical Journal 2013, 779, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahakyan, N. Lepto-hadronic γ-Ray and Neutrino Emission from the Jet of TXS 0506+056. The Astrophysical Journal 2018, 866, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Ruiz, E.; Galván-Gámez, A.; Fraija, N. Testing a Lepto-Hadronic Two-Zone Model with Extreme High-Synchrotron Peaked BL Lacs and Track-like High-Energy Neutrinos. Galaxies 2023, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguilar-Ruiz, E.; Fraija, N.; Galván-Gámez, A. High-energy neutrino fluxes from hard-TeV BL Lacs. Journal of High Energy Astrophysics 2023, 38, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sasse, R.; Costa, Jr., R.; Pereira, L.A.S.; dos Anjos, R.C. Blazars Jets and Prospects for TeV-PeV Neutrinos and Gamma Rays Through Cosmic-Ray Interactions. Braz. J. Phys. 2025, 55, 60, [arXiv:astro-ph.HE/2501.09108]. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | |

| 2 |

| Observatory | Energy range (eV) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| BeppoSAX | - | [80] |

| VERITAS | - | [81] |

| H.E.S.S. | – | [82] |

| ARGO | – | [83] |

| Fermi | – | [84,85,86,87,88] |

| Burst Alert Telescope (BAT) | - | [89] |

| Röntgensatellit (ROSAT) | – | [90,91,92] |

| Einstein (HEAO-2) | – | [39,52,93] |

| XRT (Swift) | - | [94,95] |

| Observatory | Energy range (eV) | Reference |

|---|---|---|

| BeppoSAX | - | [80] |

| WHIPPLE | [96] | |

| VERITAS | [59] | |

| HEGRA | [57] | |

| MAGIC | - | [97] |

| ARGO | – | [98] |

| Fermi | - | [84,85,86,87,88] |

| Burst Alert Telescope (BAT) | - | [89,99,100,101,102] |

| Monitor of All-sky X-ray Image | - | [103] |

| XMM-Newton (ESA) | - | [104,105] |

| SAX-MECS | - | [106] |

| Symbol | Description | 1ES 0414+009 | 1ES 1959+650 |

|---|---|---|---|

| Minimum electron Lorentz factor | |||

| Break electron Lorentz factor | |||

| Maximum electron Lorentz factor | |||

| B [G] | Magnetic field strength | ||

| R [cm] | Radius of emitting region (blob) | ||

| [deg] | Viewing angle | ||

| N [] | Particle number density | ||

| p | Spectral index below | ||

| Spectral index above | |||

| Bulk Lorentz factor |

| Symbol | Description | 1ES 0414+009 | 1ES 1959+650 |

|---|---|---|---|

| [erg ] | Electron energy density | ||

| [erg ] | Magnetic energy density | ||

| [erg ] | Synchrotron photon energy density | ||

| [erg ] | Synchrotron radiative power | ||

| [erg ] | SSC radiative power | ||

| [erg ] | Total radiated power | ||

| [erg ] | Jet kinetic power |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).