Introduction

Currently, higher education institutions face the challenge of training professionals capable of responding to complex and changing social contexts marked by multiple inequalities. In the field of Social Work, this challenge takes on a particular dimension, as it involves equipping students with methodological tools that enable them to intervene critically, ethically, and participatively. One such tool is Participatory Action Research (PAR), an approach that promotes the active involvement of individuals in their own transformation processes, fostering empowerment and grassroots social change. However, teaching PAR through traditional pedagogy is limited, as it risks reducing a transformative methodology to a set of abstract content devoid of lived experience.

In this context, gamification emerges as an innovative pedagogical proposal, capable of activating students’ intrinsic motivation, encouraging collaboration, and facilitating meaningful appropriation of complex knowledge. By incorporating game dynamics into non-game settings, gamification not only creates more engaging learning environments but also promotes situated and experiential learning, in alignment with the principles of PAR. Recent studies (Seaborn & Fels, 2020; Al-Azawi et al., 2016) show that gamified strategies contribute to the development of key competencies such as critical thinking, decision-making, interpersonal communication, and teamwork—all essential skills for professional practice in Social Work.

Thus, gamification presents itself as an emerging didactic strategy that incorporates game mechanics into non-ludic environments to enhance motivation, engagement, and meaningful learning. Various studies have demonstrated its effectiveness in university settings to improve participation, student autonomy, and the development of soft skills needed in social intervention (Deterding et al., 2011; Kapp, 2012).

Moreover, previous research in the field of social sciences and higher education highlights the need to diversify teaching methodologies to meet the new learning styles of university students, who are increasingly accustomed to interactive, digital, and collaborative environments (Paz González et al., 2023; Pérez Gallo et al., 2024; Jaramillo Mediavilla, 2022; Kivisto & Hamari, 2019). In this sense, applying gamification to the teaching of PAR makes it possible to connect theory and practice in an innovative way, bringing students closer to real processes of social intervention through a participatory logic.

The purpose of this study is to explore the effectiveness of gamification as a pedagogical strategy for training in PAR among undergraduate Social Work students at the University of Zaragoza. Through a pedagogical experiment conducted over one semester, the study analyzes how this methodology impacts the development of professional competencies linked to participatory work. The main objective is to provide evidence of the transformative potential of gamification in Social Work education, as well as to propose new methodological lines that strengthen training more committed to social reality. Its relevance lies in offering an innovative, replicable educational alternative aligned with the ethical-political principles of contemporary Social Work.

Materials and Methods

The experience was structured as an exploratory case study with a qualitative approach and quantitative support. A gamification strategy was implemented over a full semester (February–June 2024) in the course “Social Research Practicum”, part of the fourth year of the undergraduate Social Work program.

The participant group consisted of 20 students enrolled in the course, divided into four work teams. The intervention was based on a system of missions, levels, symbolic rewards, and collaborative narratives. Each team had to assume the role of a fictional citizen collective aiming to transform a specific social issue (e.g., evictions, at-risk youth, job search motivation among migrants, etc.), developing a simulated PAR process with all its components (diagnosis, action plan, evaluation).

The gamified dynamics included:

Experience points (XP) for completed tasks

Rewards for individual and group achievements

Weekly challenges such as “escape rooms” or “trivia” related to PAR theory

Cooperation and leadership rankings

Data collection involved:

Pre- and post-test questionnaires on perceived competencies (using a 1–5 Likert scale)

Classroom participation records

Formative assessment rubrics

A focus group held at the end of the experience

Quantitative data were analyzed using descriptive statistics (means and standard deviations) with SPSS v.27, while qualitative data were thematically coded following Braun and Clarke’s (2006) method.

The methodologies employed were inspired by previous experiences of gamification in higher education (Domínguez et al., 2013; Hamari et al., 2014) and by literature on teaching PAR in Social Work (Fals Borda, 1986; Llobet et al., 2004).

Furthermore, the methodological approach of this study draws on a growing body of research highlighting the value of gamification as an effective pedagogical strategy for competency development in higher education contexts. It has been shown that game mechanics not only enhance student motivation and engagement but also foster meaningful learning, the development of soft skills, and active participation in the classroom (Pérez Gallo, 2025; Pelizzari, 2023).

Recent studies emphasize that motivational information systems, such as those used in gamified environments, can create a favorable context for autonomous and collaborative learning—key elements in the training of Social Work professionals (Koivisto & Hamari, 2019). It has also been evidenced that games applied in university education should not be limited to superficial ludic elements, but must align with structured learning objectives, promoting the development of specific competencies such as leadership, planning, or problem-solving (Pérez Gallo & Carbonell Pupo, 2024; Dichev et al., 2017).

Other studies stress the importance of linking gamified experience design to curricular goals, promoting the use of digital tools as a means to contextualize learning in simulated situations—similar to the logic behind this PAR-focused intervention (Subhash & Cudney, 2018). Finally, Kocakoyun and Ozdamli (2018) highlight the need for a solid methodological foundation in gamified designs that allows not only for the evaluation of immediate results but also for assessing their potential to generate lasting transformations in teaching practices.

Results and Discussion

Quantitative Analysis Using SPSS

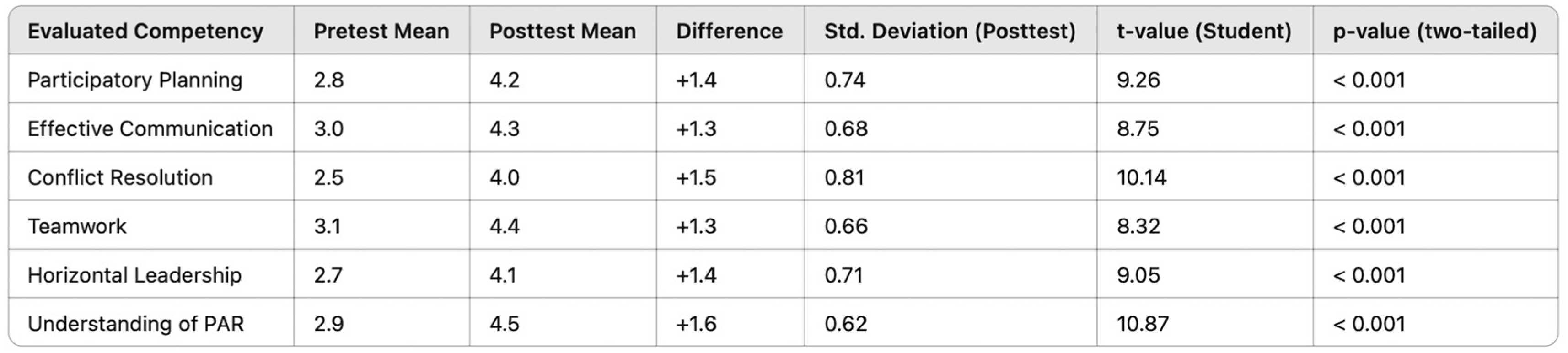

A paired-samples t-test was applied to compare the results of the competency questionnaire before and after the gamified intervention. All analyzed competencies showed statistically significant differences (p < 0.001), indicating that the observed improvements were not due to chance but rather to the impact of the gamified experience.

Furthermore, the post-test standard deviations were relatively low (< 0.81 in all cases), suggesting consistent improvement among students. The competency that showed the greatest increase was

understanding of PAR, with a difference of +1.6 points on the 1–5 Likert scale. The table below contrasts the competencies acquired by students before and after the intervention and shows a remarkable improvement across all areas, especially in “Understanding of PAR” and “Participatory Planning” (see

Table 1).

This analysis empirically supports the effectiveness of the pedagogical model and demonstrates that gamification not only motivates students but also transforms learning in a measurable way, facilitating deeper internalization of key Social Work competencies.

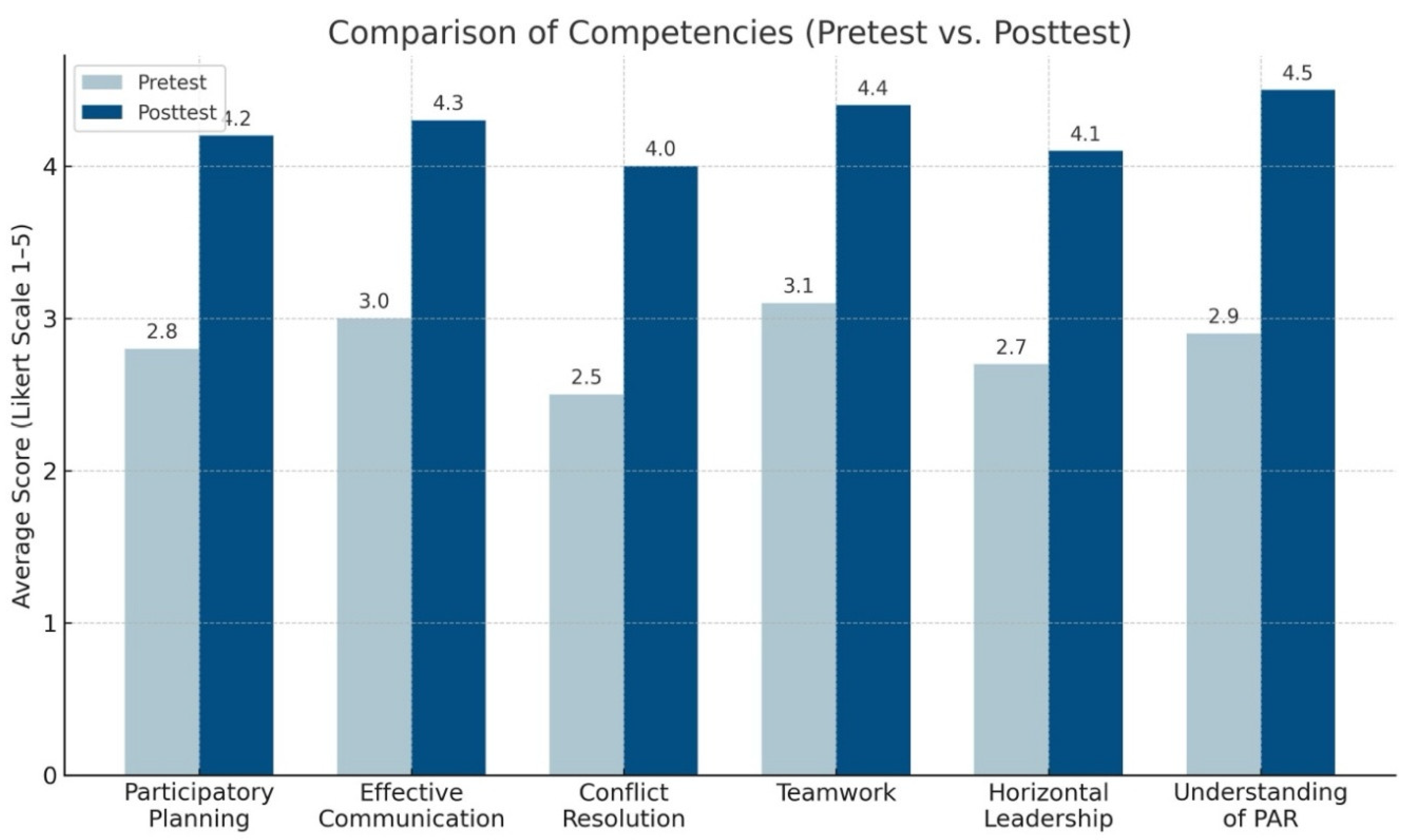

Additionally, the bar graph comparing competencies clearly and visually illustrates the impact of the gamified pedagogical strategy on the development of key skills for Participatory Action Research among Social Work students (see

Figure 1).

Each group in the graph represents a specific evaluated competency, and each bar corresponds to the average score obtained in the pretest and posttest (Likert scale: 1 to 5).

Evaluated Competencies:

Understanding of PAR

Effective Communication

Teamwork

Conflict Resolution

Participatory Planning

Analysis and Interpretation

Understanding of PAR: Increased from 2.6 to 4.4. This growth indicates that gamification enabled not only a theoretical understanding of PAR but also experiential engagement through challenges and simulations.

Effective Communication: Improved from 3.0 to 4.3. The ongoing need to coordinate with team members, defend proposals, and give presentations notably enhanced students’ communication abilities.

Teamwork: Increased from 3.1 to 4.5, one of the most strengthened competencies. The gamified structure naturally encouraged sustained collaboration and role management.

Conflict Resolution: Rose from 2.5 to 4.0. Shared missions required students to manage disagreements and seek consensus, reinforcing a competency that is often difficult to work on in lecture-based settings.

Participatory Planning: Increased from 2.8 to 4.2, showing that the gamified approach helped students understand the importance of collectively designing social actions, reinforcing both content and method.

Conclusion of the Analysis

The data show significant improvement in all key competencies, confirming that gamification not only increased student motivation and engagement but also had a profound pedagogical impact, facilitating active, situated, and transformative learning.

Self-assessments revealed notable gains in participatory planning (from 2.8 to 4.2), effective communication (from 3.0 to 4.3), and conflict resolution (from 2.5 to 4.0). Participation records indicated a 34% increase in voluntary student contributions during debates and presentations (see

Table 2).

Significant Improvements in the Teaching-Learning Process

1. Teamwork

Teamwork was one of the competencies that showed the most significant improvement. Through gamified dynamics such as role-playing community interventions or collaborative challenges inspired by real-world contexts, students not only learned to cooperate but also to recognize the value of professional interdependence in PAR settings. 95% reported clear improvement in this competency, with comments such as: “I never felt we worked so united as we do now.”

2. Communication and Leadership

Gamification enhanced both verbal and non-verbal communication skills in contexts of horizontal leadership. Especially in games requiring role alternation and joint decision-making, students practiced ways to facilitate participatory processes. 87% recognized progress in this area.

3. Understanding of the PAR Approach

A deeper understanding of the PAR paradigm was identified. Through gamified simulations placing them as change agents in fictional communities, students internalized the ethical, methodological, and political principles of the approach. Common expressions included: “Now I understand that researching also means accompanying.”

4. Group Facilitation Skills

Participants improved their ability to propose and facilitate participatory dynamics—one of the key areas of fieldwork in Social Work. The playful component supported the acquisition of practical tools in simulated intervention contexts.

5. Self-Efficacy and Motivation

Gamification proved highly effective in boosting intrinsic motivation, especially among students who felt disconnected from traditional methods. 80% reported feeling “more competent” to apply PAR after the experience. They also reported reduced anxiety and greater involvement.

6. Critical and Reflective Thinking

The gamified design included reflective spaces after each dynamic, promoting awareness of the professional’s role in complex social settings. This dimension was enhanced by working through simulated ethical dilemmas and community tensions.

Focus Group Results

The qualitative data supported these findings. The focus group expressed a high degree of satisfaction with the methodology used. Participants noted that the game dynamics allowed them to personally experience the participatory process, take on leadership roles, negotiate decisions, and empathize with diverse social realities.

One student remarked: “I understood PAR when I had to plan and defend it with my team. The game made me live it, not just study it.”

Literature agrees that game-based learning fosters emotional engagement, improves content retention, and supports situated learning (Gee, 2003; Kapp, 2012). In this sense, gamification did not merely motivate—it structured a transformative learning environment aligned with PAR principles.

However, some challenges were identified, such as the perceived workload by some students and the need for prior faculty training in gamified design. Further research is needed to assess the sustainability of such approaches and their impact in less controlled contexts.

Future Research Directions

These are derived from the study on the use of gamification to teach Participatory Action Research (PAR) to Social Work students:

Longitudinal studies that analyze the medium- and long-term impact of gamification on students’ professional development, evaluating whether the acquired competencies are sustained or effectively transferred to real-world work contexts.

Inter-university comparisons, applying similar methodologies in other universities or Social Work faculties, to assess the replicability of the model and identify relevant contextual variables.

Evaluation of the impact of gamification on learning equity, analyzing whether this methodology reduces or widens gaps in participation and performance among students with different levels of digital skills or educational backgrounds.

Analysis of the teaching role in gamified environments, exploring how pedagogical relationships, teaching styles, and perceptions of authority shift in these dynamics, as well as identifying the skills needed to successfully design and implement such experiences.

Comparative studies between active methodologies, assessing the relative impact of gamification versus other strategies such as problem-based learning (PBL), service-learning, or flipped classrooms, particularly in teaching participatory methodologies.

Integration of emerging technologies, such as augmented reality or artificial intelligence, in the design of gamified environments to explore new ways of simulating participatory processes and providing personalized feedback.

Conclusions

The conclusions of this study confirm that the implementation of gamification as a pedagogical strategy in university education—specifically in the training of competencies for the professional use of Participatory Action Research (PAR) in Social Work students—constitutes an innovative tool with positive effects on both student engagement and the development of key skills for their future professional practice.

The experience, carried out in a specific local context such as the University of Zaragoza, showed that active and participatory methodologies can transform students’ perception of learning by increasing motivation, involvement, and critical capacity.

Although limited to a specific course and a small group, the results offer transferable contributions to other educational settings aiming to strengthen practical training, teamwork, and problem-solving from a participatory perspective. The gamified design not only energized the classroom but also created simulation scenarios that brought students closer to real challenges of social intervention, thus supporting situated learning.

This research represents progress in the integration of emerging methodologies in higher education and proposes new lines of work related to teacher training in innovative pedagogical design, curricular integration of playful digital tools, and longitudinal evaluation of the impact of these strategies on students’ professional performance after graduation. Far from being a passing trend, gamification emerges as a solid path to reinforce student-centered training processes, grounded in their context and their active role as agents of change.

References

- Al-Azawi, R., Al-Faliti, F., & Al-Blushi, M. (2016). Educational gamification vs. game-based learning: A comparative study. International Journal of Innovation, Management and Technology, 7(4), 131–136. [CrossRef]

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101. [CrossRef]

- Deterding, S., Dixon, D., Khaled, R., & Nacke, L. (2011). From game design elements to gamefulness: Defining gamification. In Proceedings of the 15th International Academic MindTrek Conference: Envisioning Future Media Environments (pp. 9–15). [CrossRef]

- Dichev, C., & Dicheva, D. (2017). Gamifying education: What is known, what is believed and what remains uncertain—A critical review. International Journal of Educational Technology in Higher Education, 14, 9. [CrossRef]

- Domínguez, A., Saenz-de-Navarrete, J., de-Marcos, L., Fernández-Sanz, L., Pagés, C., & Martínez-Herráiz, J. J. (2013). Gamifying learning experiences: Practical implications and outcomes. Computers & Education, 63, 380–392. [CrossRef]

- Fals Borda, O. (1986). Conocimiento y poder popular. Bogotá: Siglo XXI.

- Gee, J. P. (2003). What video games have to teach us about learning and literacy. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hamari, J., Koivisto, J., & Sarsa, H. (2014). Does gamification work?—A literature review of empirical studies on gamification. In 2014 47th Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences (pp. 3025–3034). IEEE. [CrossRef]

- Jaramillo Mediavilla, L. (2022). La gamificación como metodología activa en el proceso de enseñanza-aprendizaje: Caso de estudio: estudiantes de la carrera de Pedagogía de las Artes. Revista Ecos De La Academia, 8(15), 21–33. [CrossRef]

- Kapp, K. M. (2012). The gamification of learning and instruction: Game-based methods and strategies for training and education. John Wiley & Sons.

- Kocakoyun, S., & Ozdamli, F. (2018). A review of research on gamification approach in education. In InTech. [CrossRef]

- Koivisto, J., & Hamari, J. (2019). The rise of motivational information systems: A review of gamification research. International Journal of Information Management, 45, 191–210. [CrossRef]

- Llobet, M., Cortés, F., & Alemany Monleón, R. M. (2004). Proyecto de investigación/acción en trabajo social comunitario: La construcción de prácticas participativas. Retrieved from https://rabida.uhu.es/dspace/handle/10272/228.

- Paz González, A., Lahera Martínez, F., & Pérez Gallo, V. H. (2023). Teoría sociocultural: potencialidades para motivar la clase de Historia de Cuba en las universidades. EduSol, 23(83), 14–27. http://scielo.sld.cu/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S1729-80912023000200014.

- Pelizzari, F. (2023). Gamification in higher education: A systematic literature review. Italian Journal of Educational Technology, 31(3), 21–43. [CrossRef]

- Pérez Gallo, V. H., Martínez Tena, A. de la C., & Expósito García, E. (2024). La sociología de la cultura: apuntes para su enseñanza. Interconectando Saberes, (17), 59–70. [CrossRef]

- Pérez Gallo, V. H., & Carbonell Pupo, A. (2024). Información y sociedad: el obligado enfoque holístico para los estudiantes de ciencias de la información. Revista de Innovación Social y Desarrollo, 9(2), 456–470. https://revista.ismm.edu.cu/index.php/indes/article/view/2677.

- Pérez Gallo, V. H. (2025). Active Teaching Methodologies in the Research “Practicum” for Social Work Students. Research Square. [CrossRef]

- Seaborn, K., & Fels, D. I. (2020). Gamification in theory and action: A survey. International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 132, 101–120. [CrossRef]

- Subhash, S., & Cudney, E. A. (2018). Gamified learning in higher education: A systematic review of the literature. Computers in Human Behavior, 87, 192–206. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).