1. Introduction

Conservation medicine is a transdisciplinary approach to bridge animal, human and ecosystem health, in an ecological context (Tabor, 2002). It investigates the links between health, pathogens, species and ecosystems, including anthropogenic impacts, to identify strategies to better protect wildlife, ecosystem, and human health (Aguirre et al., 2012). Given the numerous environmental changes which have occurred in recent history, conservation strategies should encompass the ability of wildlife to overcome these health challenges (Stephen, 2014). Stephen (2014) describes how a modern definition of wildlife health should include determinants and characteristics of the animal, environment, and/or society, which may affect the ability of wildlife to cope with change, their vulnerability and resilience.

If conservation plans are to be successful in preventing local and global species declines and extinctions, it is important that threats are understood and analysed. Many threats to sea turtles are anthropogenic in origin, affecting individuals, populations, the environment, and ecosystems, therefore impacting their health directly and indirectly. Threats include, but are not limited to overexploitation (direct harvest of sea turtles and their eggs), climate change, habitat loss and degradation, pollution (chemical and marine debris), and interaction with fisheries (Abreu-Grobois and Plotkin, 2008). Life history traits make sea turtles particularly vulnerable to these threats, due to time to reach sexual maturity (20 to 30 years), long lifespan (exceeding 100 years), pelagic foraging, use of multiple habitats (open ocean, coastal regions and beaches), migratory behaviour, and low hatchling survival rate (NOAA, 2019; Stelfox et al., 2019; Godley, 2020). Sea turtles are highly charismatic and therefore may act as a flagship species for marine conservation issues, raising awareness and driving change (Godley, 2020). All seven sea turtle species are on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, listed as vulnerable (olive ridley) to critically endangered (hawksbill) (IUCN, 2020).

Five sea turtle species can be found in the Maldives: olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea), loggerhead (Caretta caretta), green (Chelonia mydas), hawksbill (Eretmochelys imbricata) and leatherback (Dermochelys coriacea) turtles. The Olive Ridley Project (ORP), a charity registered in the UK, Maldives and Kenya, aims to protect sea turtles and their ecosystems through scientific research, education, rescue and conservation medicine. In 2017, ORP established the Marine Turtle Rescue Centre with an on-site veterinary team, located at Coco Palm Dhuni Kolhu, Baa Atoll, Maldives. The most frequently rescued and treated sea turtle species in the Maldives is the olive ridley sea turtle (Lomas, 2019), the most abundant species in the Indian Ocean.

In the Maldives, olive ridley sea turtles are found offshore with few reported nesting sites, and it is likely these animals are migrating from nesting beaches in India or Sri Lanka. Their peak mating season occurs from February to March, with arribada nesting in Odisha, India. As this coincides with the commercial fishing season, interactions with fisheries can occur through bycatch, when non-target marine species are accidentally caught during active fishing (Duncan et al., 2017). Along the coast of Odisha thousands to tens of thousands of olive ridley sea turtles are found stranded dead, likely due to bycatch (Shanker et al., 2003). The Maldives mainly employs pole and line fishing, having developed species-specific methods to reduce their impact (Hudgins et al., 2017). During migration back to foraging grounds, there is an added risk of encountering marine debris in ocean currents (Hudgins et al., 2017).

Marine debris encompasses any solid anthropogenic material that has been discarded or transported into the marine environment, including plastic, wood, glass and metal. Sources can be land-based due to poor management of waste, or sea-based from fishing, shipping and tourism (Agamuthu et al., 2019). These items have been found in all of the world’s oceans and may persist in the environment for decades, with an estimated eight million tons of plastic entering the marine environment annually (Law, 2016; Nelms et al., 2018). Currents, tides, cyclones, winds, and rivers mean marine debris can accumulate in specific areas known as ocean convergence zones (Agamuthu et al., 2019).

Law (2016) describes three main categories of interaction marine species may have with marine debris:

- ♦

Ingestion – indirect, intentional or incidental.

- ♦

Entanglement – includes entrapment, ghost fishing, and constricting or encircling material around the affected animal. It occurs with a variety of marine debris, however, most commonly is associated with abandoned, lost, or otherwise discarded fishing gear (ALDFG), also known as ‘ghost gear’.

- ♦

Interactions – where neither of the above occur, for example: obstruction, collision, shelter, substrate for growth or transport, smothering benthic environments, and altering beach conditions for nesting.

A review of 747 studies identified 914 marine species that have been affected by marine debris, through ingestion in 701 species and entanglement in 354 species. This included all seven sea turtle species (Kühn and van Franeker, 2020).

Ingestion of marine debris may occur for a variety of reasons. Senko et al. (2020) evaluated 47 peer-reviewed studies and identified the following causes: visual resemblance to prey, attraction from biofouling, incidental due to non-selective feeding or fragmentation of plastics into microplastics, attachment to intended prey, and/or trophic transfer. Plastic ingestion can cause morbidity and mortality through false satiation, starvation, gastrointestinal-tract obstruction, ulceration, perforation, toxicity from chemical absorption, and secondary infections (Law, 2016; Nelms et al., 2018). Disruption to digestion may also cause gas to become trapped in the gastrointestinal tract which may lead to buoyancy syndrome (Nelms et al., 2016). In New Zealand, Godoy and Stockin (2018) carried out post-mortem examinations on 35 stranded juvenile or sub-adult green sea turtles and found 63% had ingested marine debris causing impaction of the intestinal tract. Debris consisted of soft, white, clear or translucent plastics, which may have been mistaken for natural prey, e.g., jellyfish (Godoy and Stockin, 2018). López-Martínez et al. (2020) analysed numerous studies and found olive ridley sea turtles had the highest levels of plastic ingestion of sea turtles, with white plastics ingested most frequently.

Entanglement is a major threat to many marine species. Modern fishing materials are often synthetic and resistant to degradation, allowing them to persist in the marine environment and to continue catching marine species after being lost or discarded; this is known as ghost fishing (Macfadyen et al., 2009). Interactions resulting in entanglement can affect growth, cause deep wounds or limb amputations, increase drag, which reduces foraging ability and/or ability to escape predators, and may cause foreign body airway obstruction. This can ultimately lead to starvation, dehydration, drowning, and death (Law, 2016; Nelms et al., 2016; Duncan et al., 2017).

Previous studies have highlighted areas for future research, including understanding the physical effects of entanglement, examining differences in entanglement rates between age groups (Duncan et al., 2017), quantitatively evaluating threats (Stelfox et al., 2020), and determining the health impacts of ALDFG (Richardson et al., 2019). The aim of this project is to use historical data obtained from the ORP Marine Turtle Rescue Centre to identify potential risk factors and health impacts associated with entanglements, investigate cases with buoyancy syndrome, and assess clinical outcomes.

2. Methods

All the data analysed were collected by the ORP Marine Turtle Rescue Centre at Coco Palm Dhuni Kolhu, Republic of Maldives. The records used in the analysis included sea turtles admitted to the centre from 28/12/2016 until 03/09/2021. As sea turtles often remain in care for some time after admission the final date included in the analysis was 30/04/2022 to ensure a standardised endpoint. Sea turtles which were either found and immediately released or found deceased and were not admitted to the rescue centre and were therefore excluded from the data analysed.

2.1. Ethical Procedures

All activities conducted by ORP staff and researchers were permitted by the Maldivian Environmental Protection Agency (Permit Numbers EPA/2019/PSR-T04, EPA/2020/PSR-T01, EPA/2021/PSR-T03, EPA/2021/PSR-T12).

A Veterinary Medical Ethical Review Committee (VERC) application was successfully submitted to the University of Edinburgh, UK, to ensure the use of data was appropriate and within ethical guidelines.

2.2. Data Tidying and Preparation for Statistical Analysis

Raw data were provided by the ORP within several Microsoft Excel spreadsheets organized by year. Data consisted of an inpatient intake sheet for all sea turtles admitted to the centre over the study period, totalling 157 patients. This sheet provided details on time and location the sea turtles were found, reason for admission, condition at admission, duration of clinical care, and outcome. Additional information with detailed clinical notes on injuries, illnesses, treatment during care, and diagnostic results, was included in 119 individual patient records.

The first step involved tidying the data within the Excel spreadsheets, ensuring consistency in formatting (including dates, weights and measurements) and correcting any errors. The intake sheet was then imported into R, and a new comma-separated value (CSV) file was created, with one row per turtle. Next, independent variables were identified, along with some new categories extracted from the individual patients’ detailed clinical notes. These variables were entered into the new CSV file using Microsoft Excel.

Table 1 describes the variables used in the analysis with references to which data sheet was used: the intake sheet (157 patients) or individual records (119 patients).

The ‘reason for admission’ groups, detailed in

Table 1, were determined from the intake admissions sheet, which recorded the primary reason for admission. Patients may have presented with multiple conditions, and therefore the reason for admission was considered to be the main cause, or other conditions were unknown at the time of admission. Entanglement was defined as entrapment, constricting, or encircling interaction with anthropogenic material (Law, 2016), and included patients where the recorded reason for admission was ‘ghost net’. Floating patients were buoyant when found and had no interaction with marine debris at the time of rescue. Debilitated turtles were either recorded as such or included those who were recorded as emaciated or weak upon clinical examination. Animal attack covered turtles subject to on-land or at-sea suspected attacks from predators, allowing these to be grouped rather than separated by the specific animal responsible. Boat strike turtles and those admitted due to wounds were specifically recorded as such in the intake form, and no further additions to these groups were made.

A sub-category was created in the Excel spreadsheets to identify all patients which had been entangled, as this allowed direct investigation of entanglement in relation to other variables. In addition, the variable ‘entanglement cause’ was added to allow investigation into the types of entangling material, and a variable specifically for the involvement of ghost nets at the time of rescue. Similarly, ‘buoyant at admit’ was created to include patients identified as floating at the time of rescue, as well as thosewho were assessed at the centre and found to be positively buoyant within two days of admission. The variable ‘total days in centre’ was recorded in the intake admissions sheet, and this was adjusted to include any time spent at other rehabilitation centres within the Maldives, until the patient’s final outcome or to 30/04/2022 for patients still in care.

All inpatient variables were created from the detailed clinical notes throughout the patients’ time in clinical care, using the individual patient records for 119 sea turtles. This allowed specific and common injuries, illnesses, treatments, and diagnostics to be included in the analysis. Flipper injuries and missing flippers at admission were recorded in the intake admissions sheet as part of the patients’ reason for admission, and in the inpatient records when assessed at the rescue centre. Amputation surgery was included in the ‘surgeries’ variable, acting as a count of the number of surgical procedures carried out. Buoyancy syndrome was separated to allow differentiation between all patients who exhibited ‘buoyancy syndrome’ (including at admission and/or during clinical care) and those who developed buoyancy whilst at the centre (i.e., ‘buoyancy syndrome not at admit’). Exploration of the clinical notes in the original dataset identified that osteomyelitis was mentioned in a number of cases, which led to the addition of this as a variable. Osteomyelitis is an infection of the bone diagnosed through radiographs and clinical examination. This condition was recorded in the clinical notes; if not mentioned, patients were considered not to have had this condition. A small subset of patients with individual records had clinical blood results recorded, varying between 16 and 45 patients for the different blood assessments. Finally, ‘change in weight’ was calculated within R using the last and first recorded weights for the individual patients.

Table 2 summarises the variables in the inpatient records dataset.

2.3. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analysis was conducted using the statistical software R, version 4.1.2 (R Core Team, 2021) within RStudio version 2021.09.01+372 "Ghost Orchid" for Windows (RStudio Team, 2021). The following R packages were installed to aid analysis and generation of plots:

tidyverse, readxl, here, janitor, fs, lubridate, knitr, skimr, gt, parameters, reporter, report, sf, sp, ggspatial, and

emmeans. Samples of specific R code used in analysis can be found in

Appendix A.

2.4. Data Exploration and Descriptive Analysis

As part of the initial data exploration process, the intake admissions sheet was analysed to investigate any potential associations between admission variables. Bar charts and histogram plots generated within R were used to investigate admission variables, identify trends and explore potential associations. For binary values of interest, 95% confidence intervals were calculated using the binomial exact method to allow comparison of the proportions, accounting for statistical uncertainty arising from group sizes. Decimal degrees for the location of sea turtle rescue were used to plot the distribution of sea turtles on a map using R. Additional variables were incorporated to assess any notable associations between location and other admission variables.

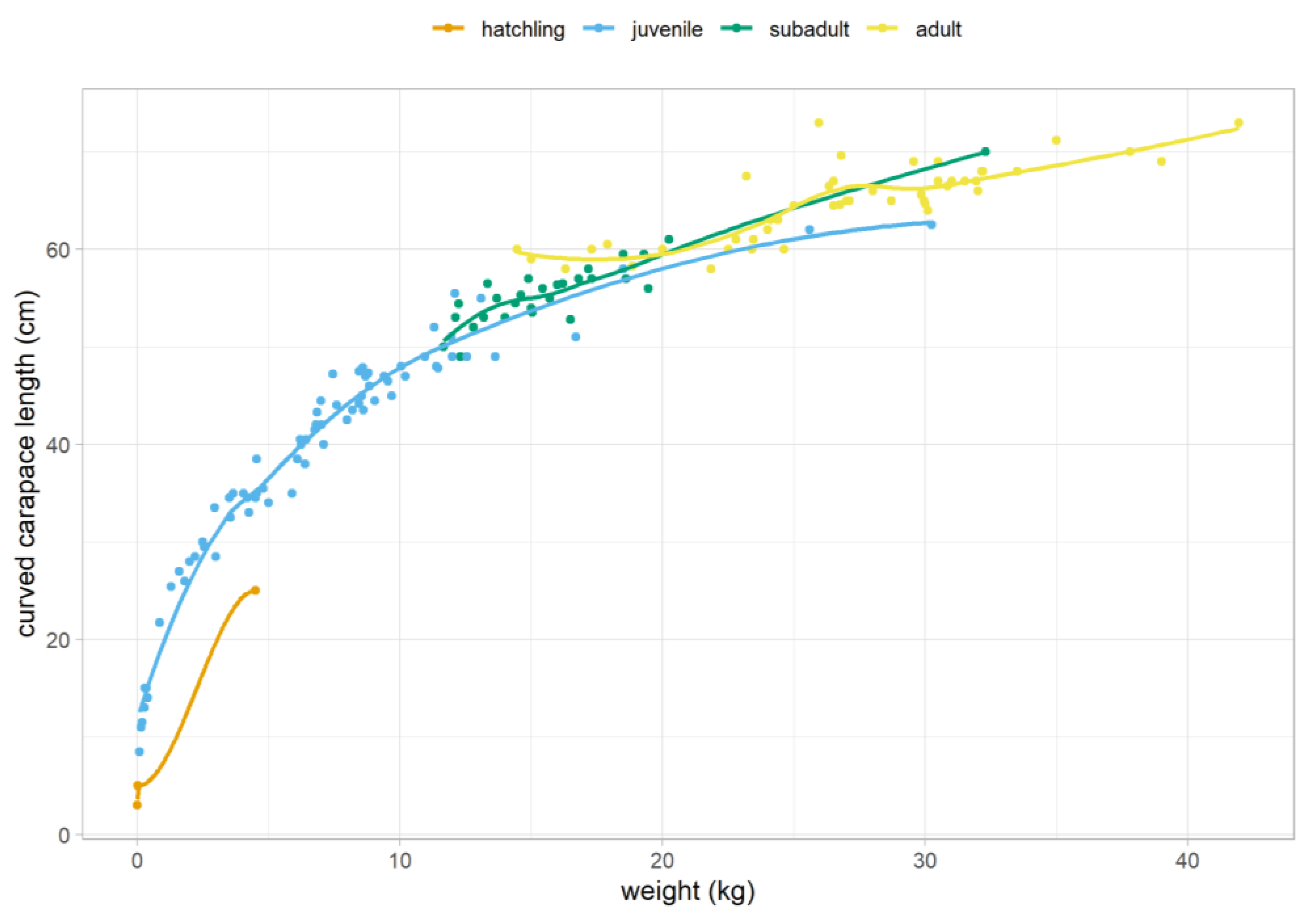

Descriptive statistics were generated for the body measurements, including weight and curved carapace length (CCL), using the median, mean, and standard deviation. The mean was often skewed by a few particularly small turtles, and the median was used as a more robust measure to avoid the influence of outliers. These descriptive statistics were then separated by species and life-stage due to known size differences between these categories. The life-stage categories used in the analysis were: CCL intervals for life stages: olive ridley: hatchling – 3.5-5 cm, juvenile – 5-30 cm, sub-adult – 50-60 cm, adult - 60 cm and greater; green: hatchling – 4-5 cm, juvenile – 5-65 cm, sub-adult – 65-85 cm, adult – 80 cm and greater; hawksbill: hatchling – 4.5-5 cm, juvenile – 4.5-55 cm, sub-adult – 55-75 cm, adult – 75 cm and greater; loggerhead: hatchling – 4.2-5 cm, juvenile – 5-70 cm, sub-adult – 70-85 cm, adult – 85 cm and greater. (Manire et al., (2017).

2.5. Clinical Outcomes

To investigate the overall outcome and duration of clinical care, the intake admissions sheet was used. Initially exploring for associations with admission variables was performed, followed by specific assessment of entanglement and buoyancy. The category of ‘current patient’ had only four sea turtles out of 157, and therefore was excluded from analysis when exploring associations between outcome and admission variables.

When considering buoyancy syndrome and buoyancy syndrome not at admission, the individual records were used. The median, mean and standard deviation were used for descriptive statistics of the total days in care. Data exploration using plots was followed by chi-squared tests, plots with 95% confidence intervals, and logistic regression.

The ‘current patient’ category was also removed when investigating associations between overall outcome and entanglement and buoyancy, to determine if this changed the significance of these variables. Clinical blood sample results were briefly investigated for possible associations with outcomes; however, this was a very small subset of patients, with a maximum of 45 included in analysis. A Kruskal-Wallis test was used to compare these numeric variables over time and to test for associations between change in blood values with outcome.

3. Results

3.1. Data Exploration with Descriptive Statistics

A total of 157 turtles were admitted to the ORP Marine Turtle Rescue Centre over the course of the study period. These patients had information on morphometric and life-stage characteristics, location and season of admission, reason for admission, duration in clinical care, and outcome.

3.2. Patient Characteristics

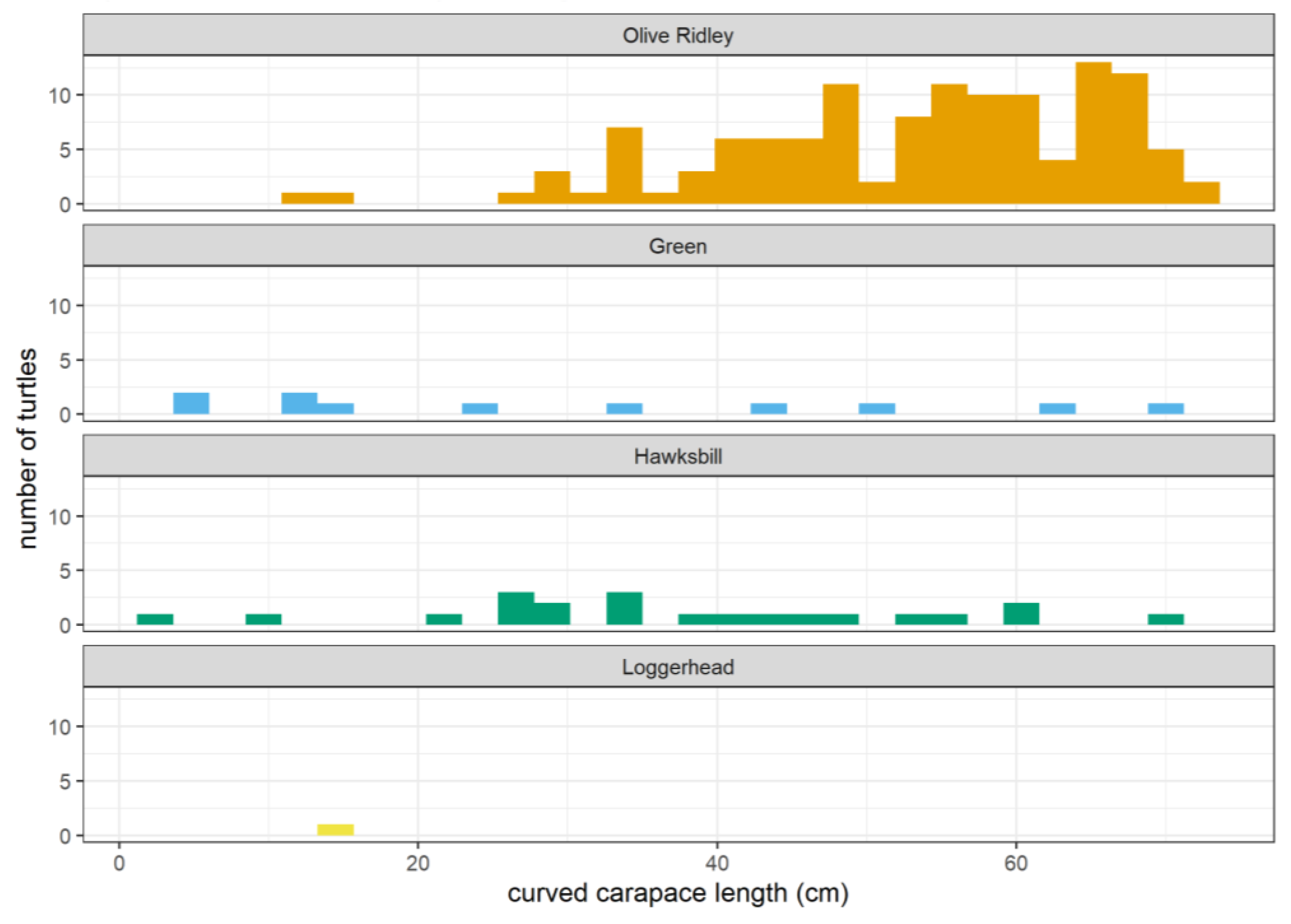

Table 3 summarises the characteristics of patients admitted to the ORP Marine Turtle Rescue Centre. Four of the seven sea turtle species were admitted over the study period, with olive ridley sea turtles making up the majority. Using the four life-stage categories outlined in the methods section, juveniles were most common, followed by adults. Many patients admitted were unable to be visually sexed; however, of those which were sexed, there were over four times as many females compared to males.

The difference in body measurements between species (

Figure 1) also reflects the patients’ life-stage (2) and body condition at admission and will therefore affect the descriptive statistics between species.

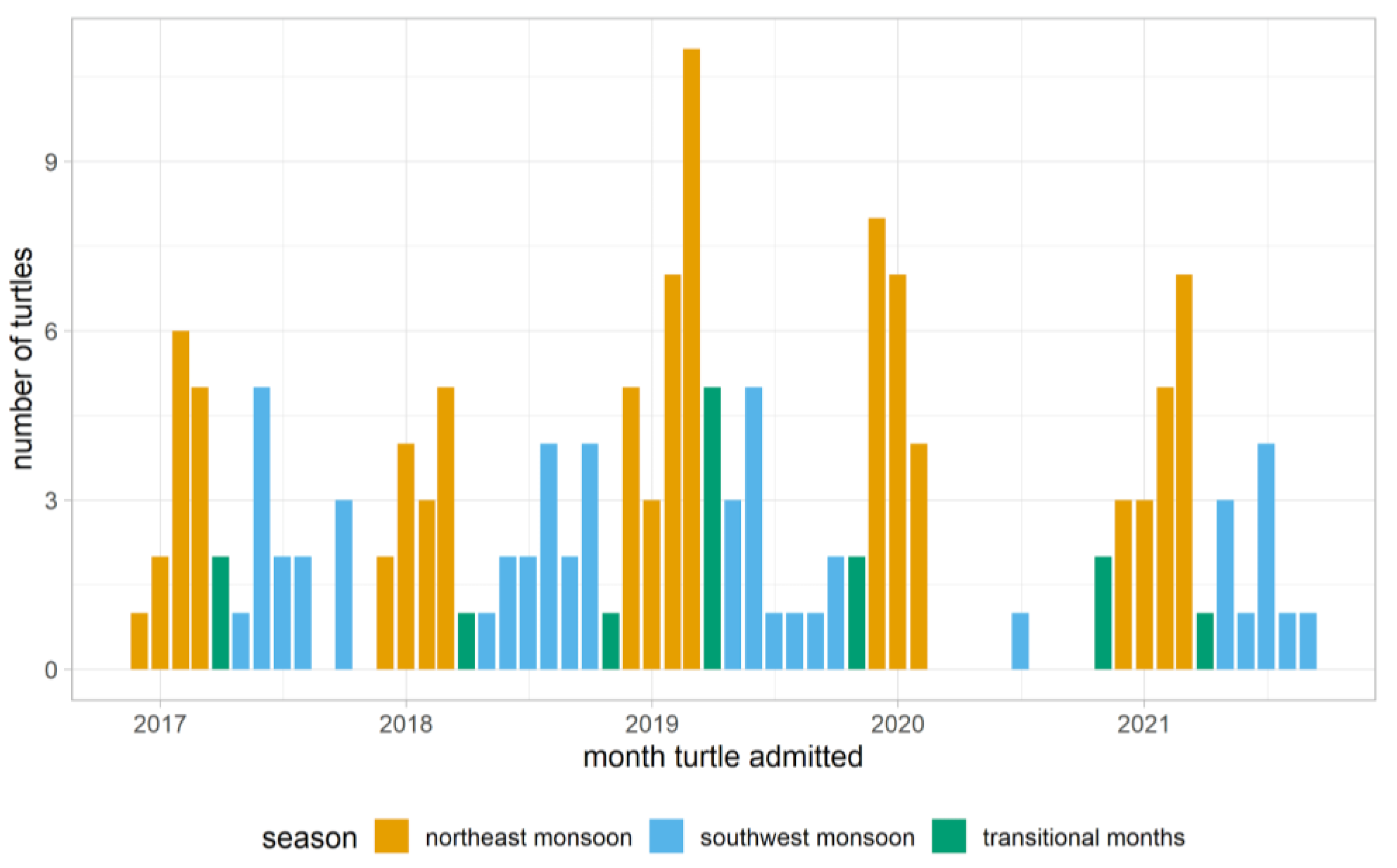

3.3. Season of Admission

There is a general pattern of increased patient admissions during the northeast monsoon season, compared to the southwest monsoon and transitional months (

Figure 3).

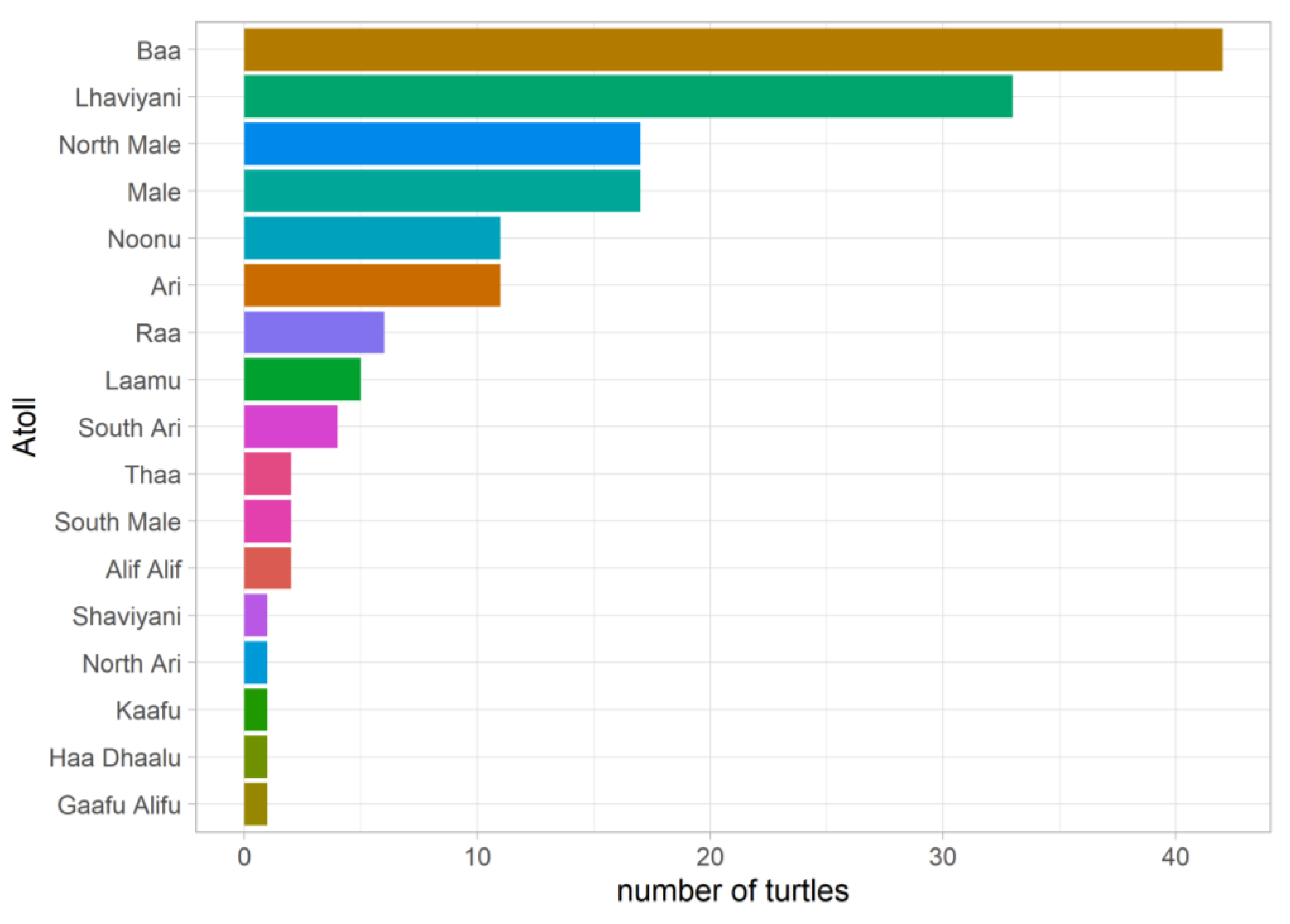

3.4. Location Found

Of the 22 geographical atolls in the Maldives, the majority of patients were found within Baa Atoll, the location of our facility (

Figure 4).

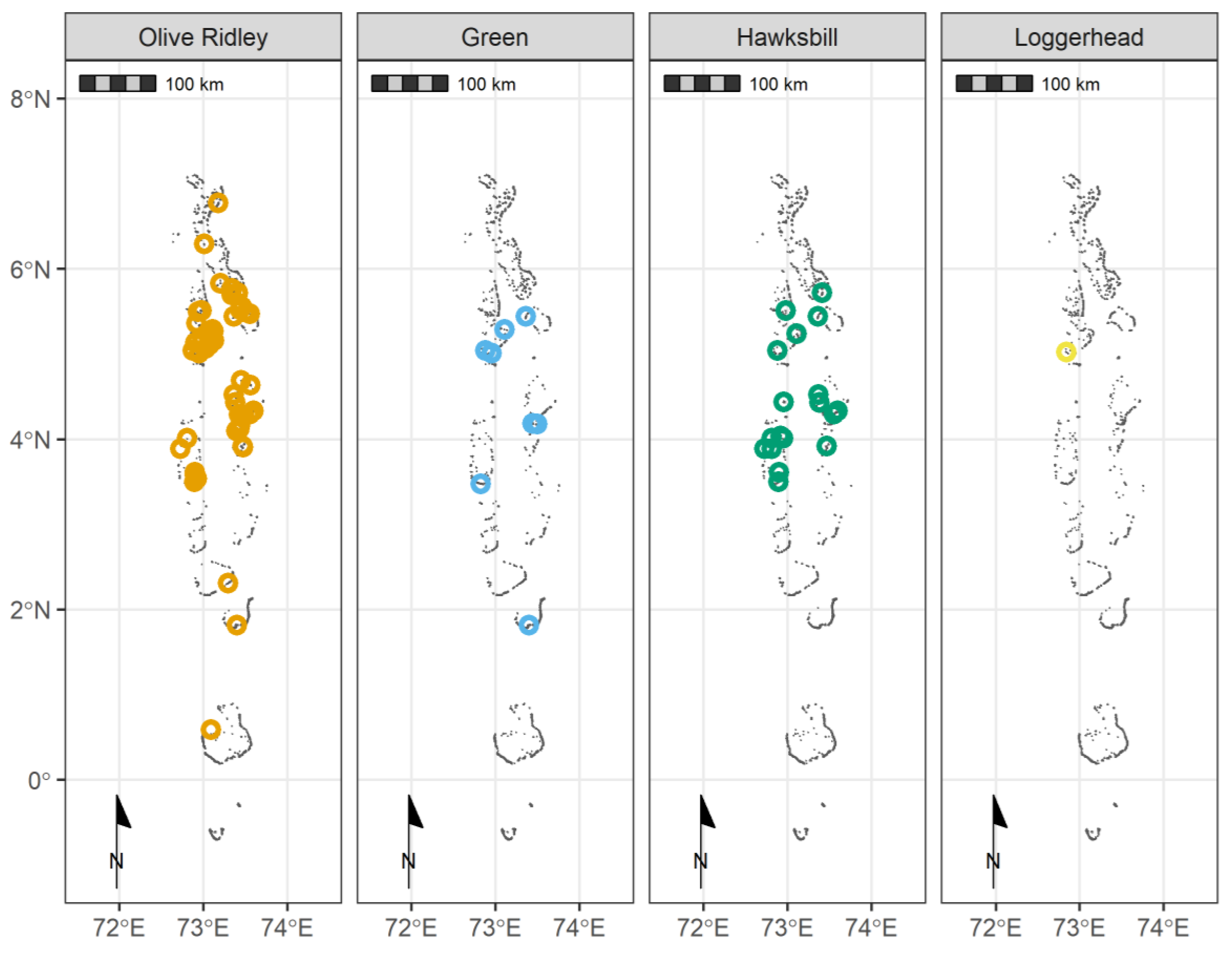

The distribution of rescued sea turtles is shown using decimal degree coordinates for the location the sea turtle was found in

Figure 5, grouped by species. Most sea turtles were rescued in atolls north of Malé (4.1748 latitude, 73.5088 longitude).

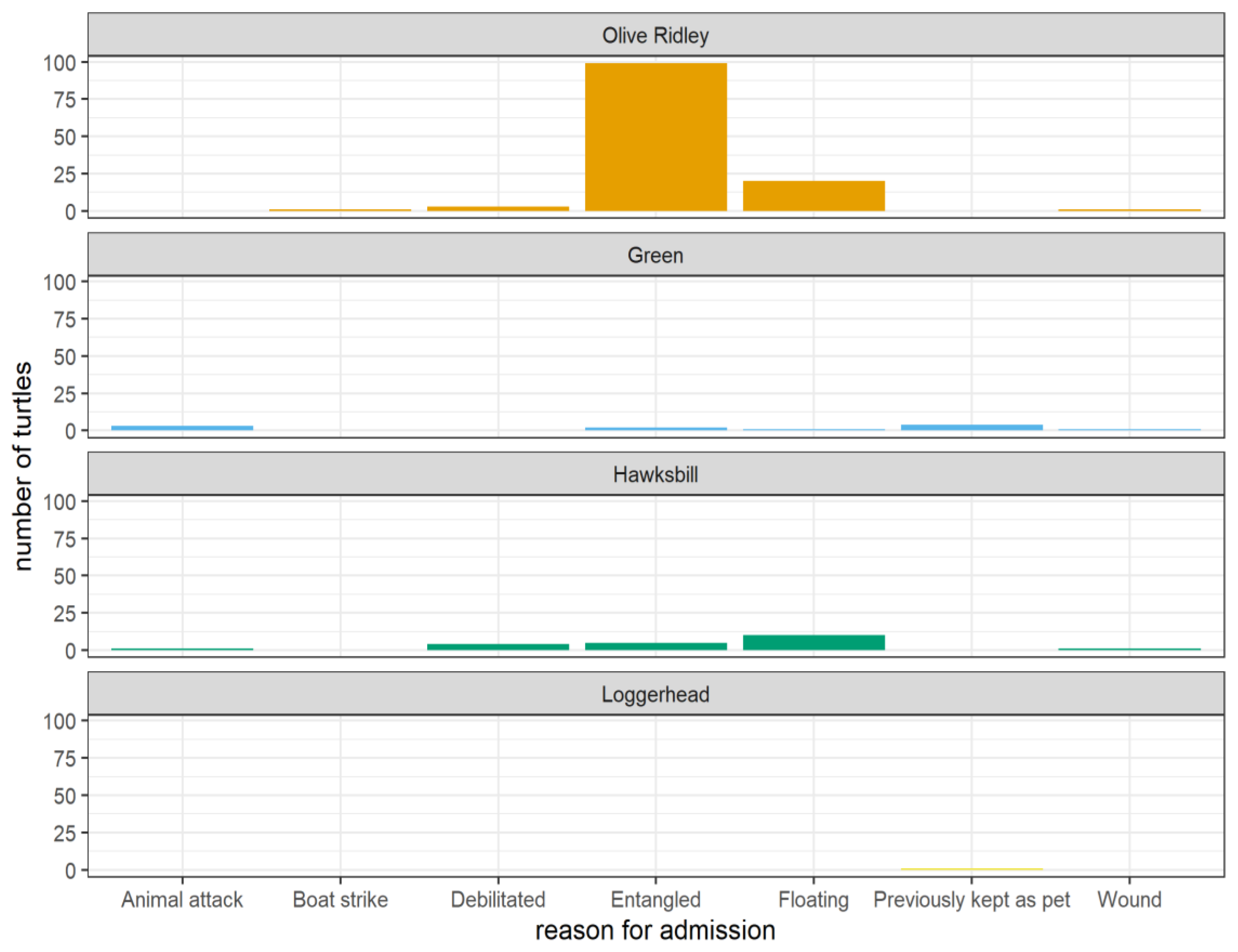

3.5. Reason for Admission

Entanglements represent the clear majority of cases seen by our facility, however when grouped by species it is apparent that this pattern really only applies to olive ridley sea turtles (

Figure 6).

Table 4 depicts the number of sea turtles in each admission category when grouped by species and the total number of sea turtles in each.

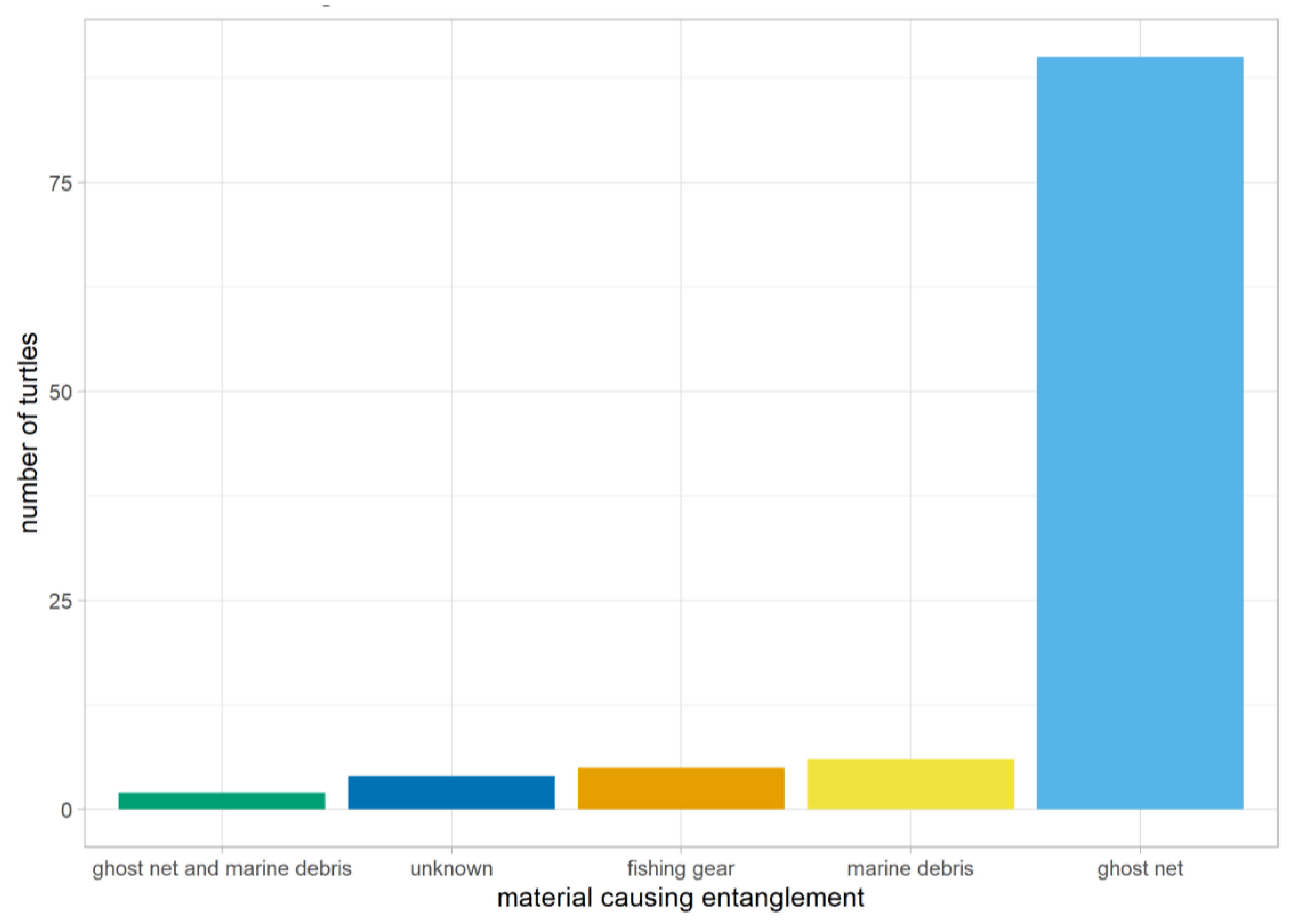

Ghost nets were attributed as the cause of entanglement in 84.1% of cases, with other fishing gear (e.g., hooks) accounting for 4.7% and marine debris 3.8% of (

Figure 7).

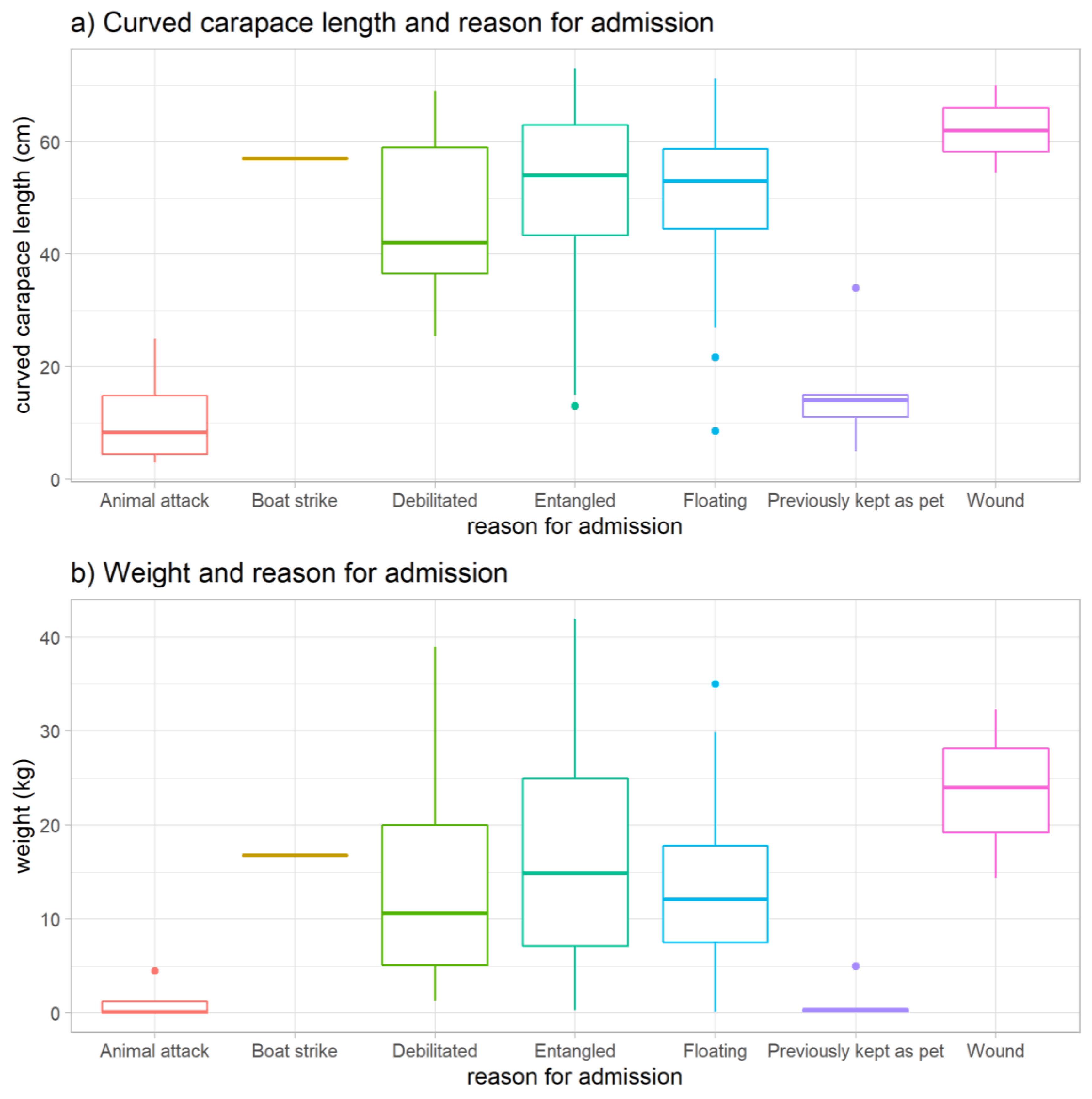

Body measurements varied depending on the reason for admission, with only small turtles being recorded as previously kept as pets or subjected to animal attacks (

Figure 8).

3.6. Overall Outcomes

Over half of the sea turtles admitted to our facility were released following clinical care (

Table 5). Current patients accounted for a minority using the standardised endpoint of 30/04/2022.

3.7. Overview of Data for Statistical Analysis

For analysis of entanglement and buoyancy syndrome cases, the admission variables described and explored above were used, along with the additional variables outlined in

Table 6.

3.8. Clinical Outcomes

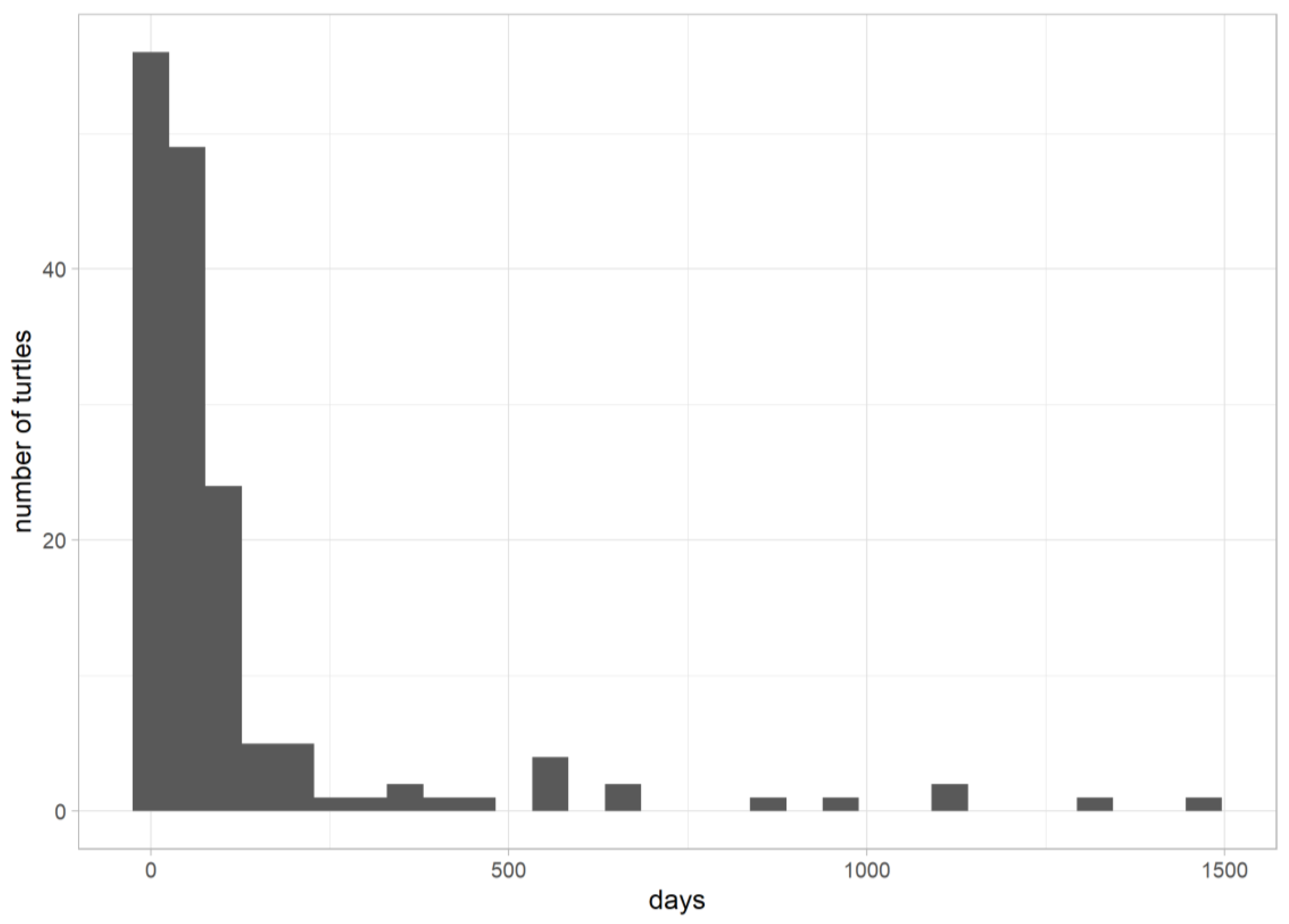

Descriptive statistics for the total days in clinical care generated a mean of 123 days and standard deviation of 245. However, the median was 36 days, reflecting a a large right-skew in the data (

Figure 9).

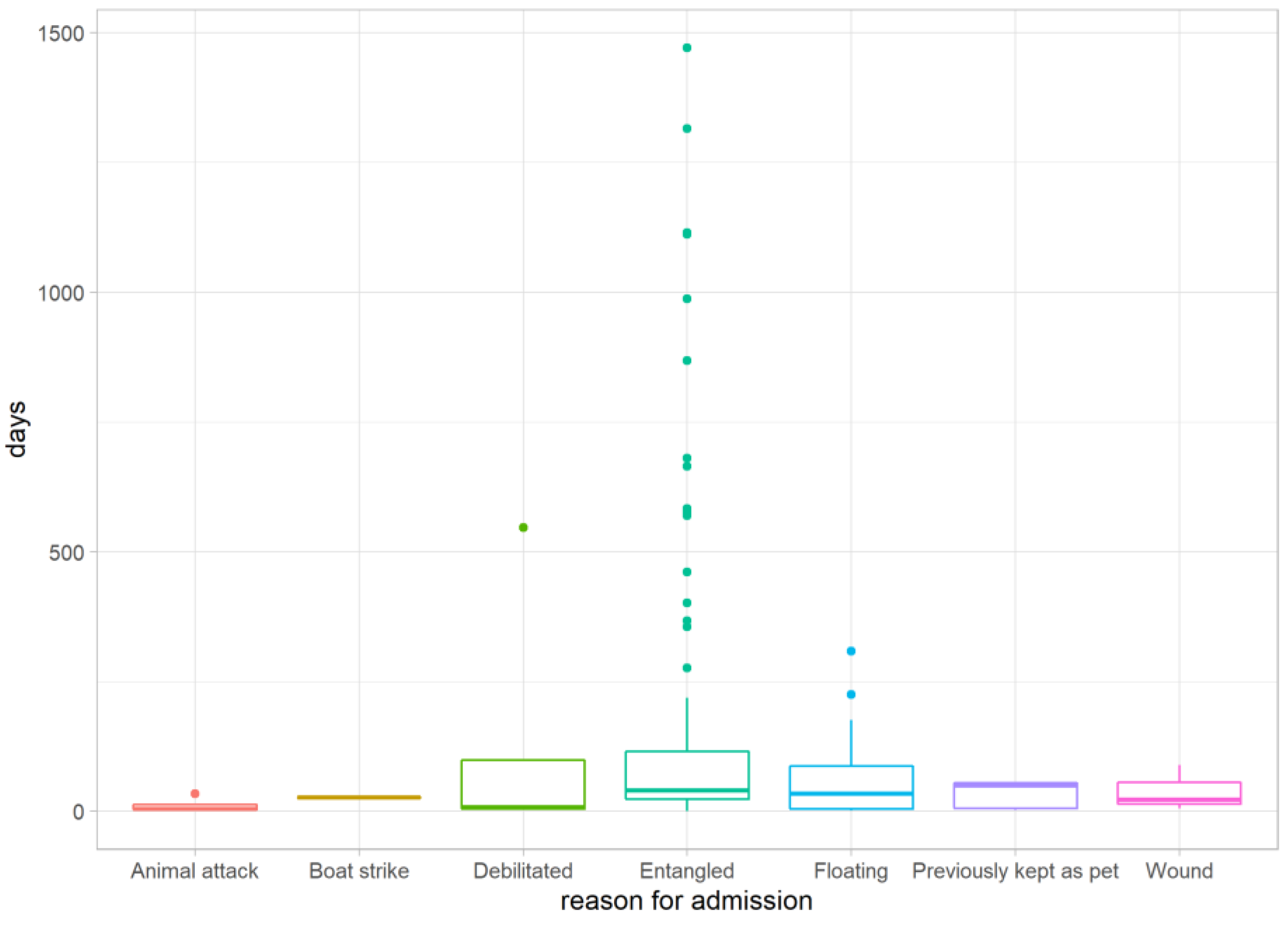

A longer time spent in clinical care was positively associated with entanglement as the reason for admission (

Figure 10).

3.9. Overall Clinical Outcomes

Initial exploration and analysis of overall outcome groups (released, deceased, and current patient) and admission variables found no significant associations. “Current patient” category was removed as it only contained four patients. The results remained non-significant for factors such as season of admission (χ

2 3.04, p = 0.218), sex (χ

2 5.38, p = 0.068), species (χ

2 3.18, p=0.356), or life-stage (χ

2 3.6, p=0.307). Although both body measurements had large effects on outcomes, they were non-significant - weight (χ

2 137.6, p=0.517) and CCL (χ

2 92.32, p=0.356). The reason for admission also had a large effect on outcomes and was further analysed using logistic regression to identify if a single category was significantly associated (

Table 7).

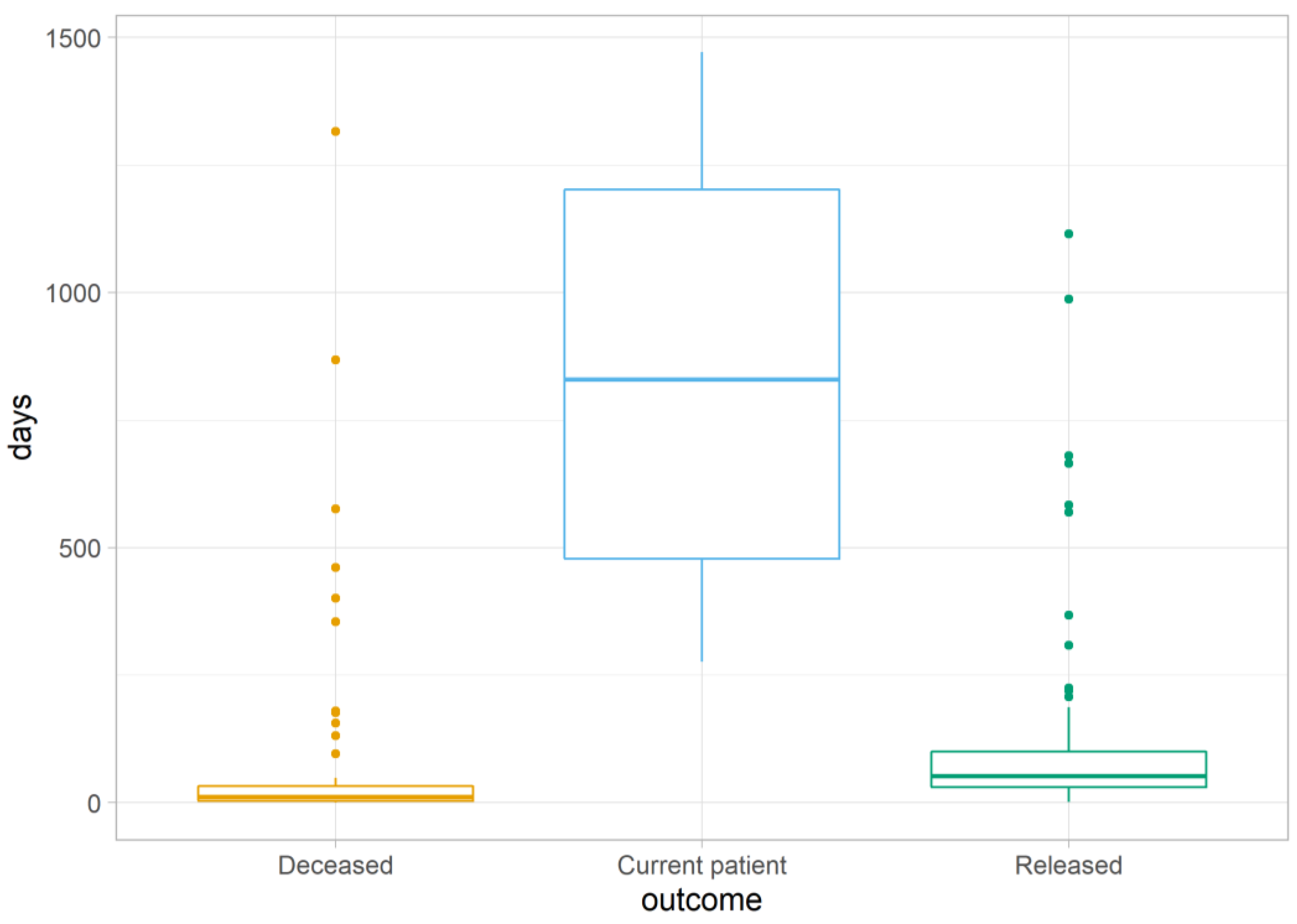

When current patients were included in initial exploration, the duration in clinical care had a large effect on overall outcome (χ

2 262.2, p < 0.001), with longer durations being positively associated with sea turtles being current patients (

Figure 11).

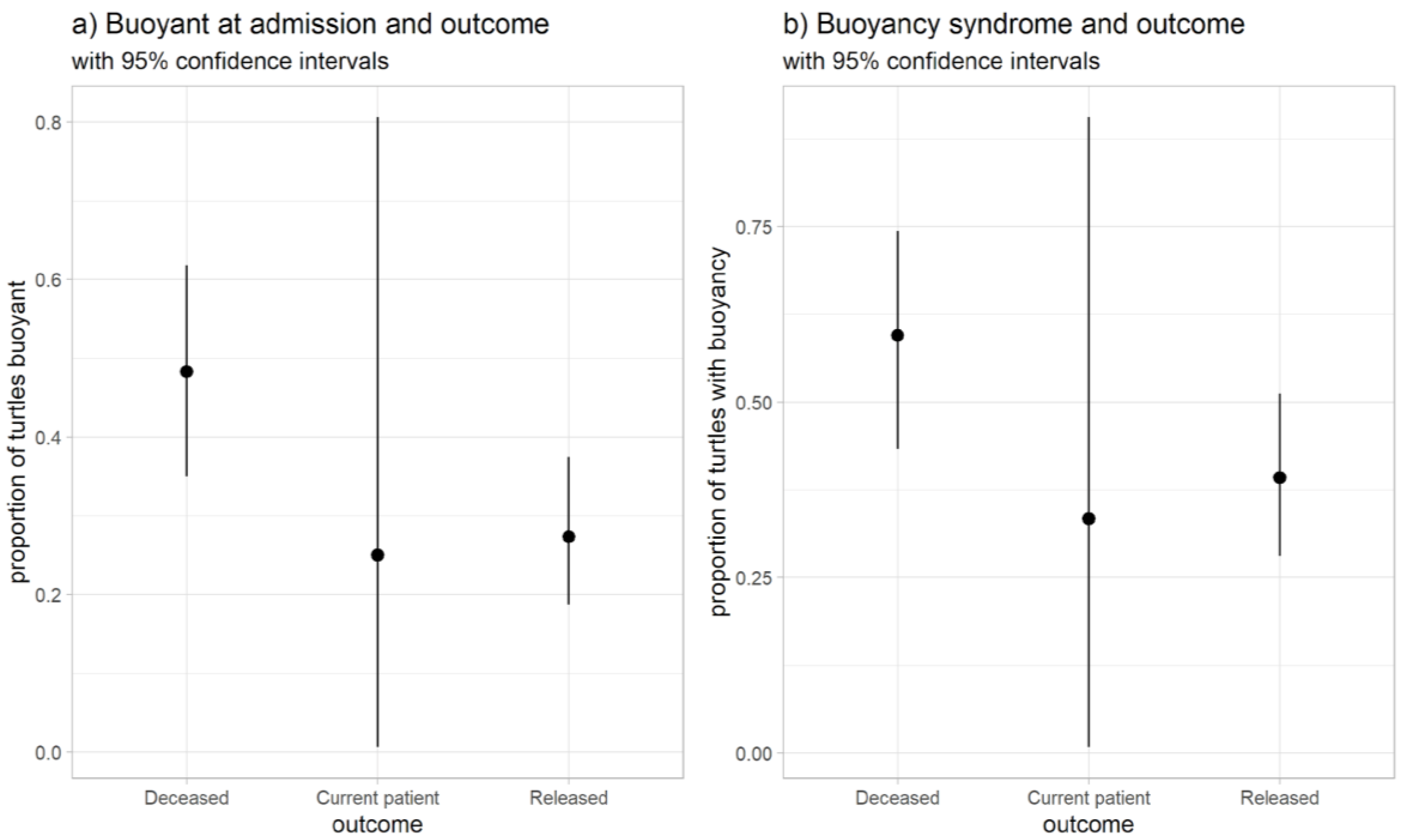

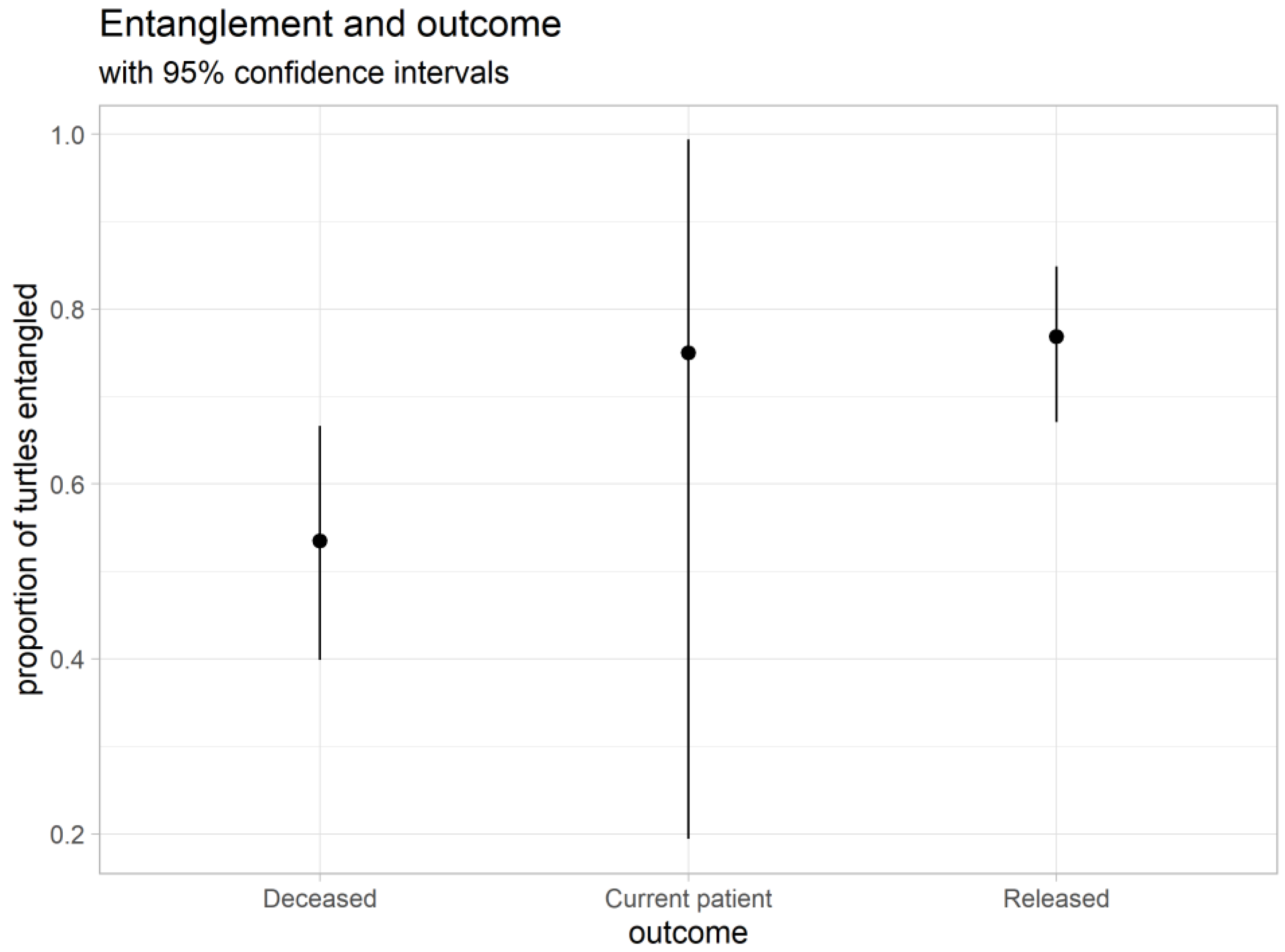

Investigating the effects of entanglement and buoyancy syndrome on overall outcomes found several significant associations. Sea turtles buoyant at admission and or diagnosed with buoyancy syndrome had a poorer overall outcome, with a higher likelihood of being deceased (

Figure 12).

Conversely, the effect of entanglement was positively associated with sea turtles being released as their overall outcome (

Figure 13).

These findings were further investigated with logistic regression (

Table 8). Patients that were buoyant at admission or had buoyancy syndrome not at admit had lower odds of being released (OR 0.40, p=0.009, and OR 0.44, p=0.036, respectively).Entangled patients, however, were positively associated with being released following clinical care (OR 2.89, p=0.003). The development of buoyancy syndrome during clinical care had no significant associations with overall outcome. When the category of ‘current patients’ was removed from the logistic regression model, there were no changes to these associations, or their significance.

A multivariable model (

Table 9) was performed to check for confounding variables between patients presenting entangled and those buoyant at admission. Patients not buoyant at admission had lower odds of being released (OR 0.43, p=0.034), confirming the finding above.

3.10. Clinical Blood Results

A small proportion of patients had clinical blood samples taken early in clinical care and then repeated either prior to release, or later in their clinical course. Descriptive statistics of these variables were generated (

Table 10).

These parameters were explored to assess any associations between the initial clinical blood test results and the overall outcome, and the findings are summarised in

Table 11.

For a smaller subset of patients, where a second clinical blood result was available, the change in these values were explored for any associations with overall outcome. No significant associations were found between the difference in first and last clinical blood test parameters, with overall outcome (

Table 12).

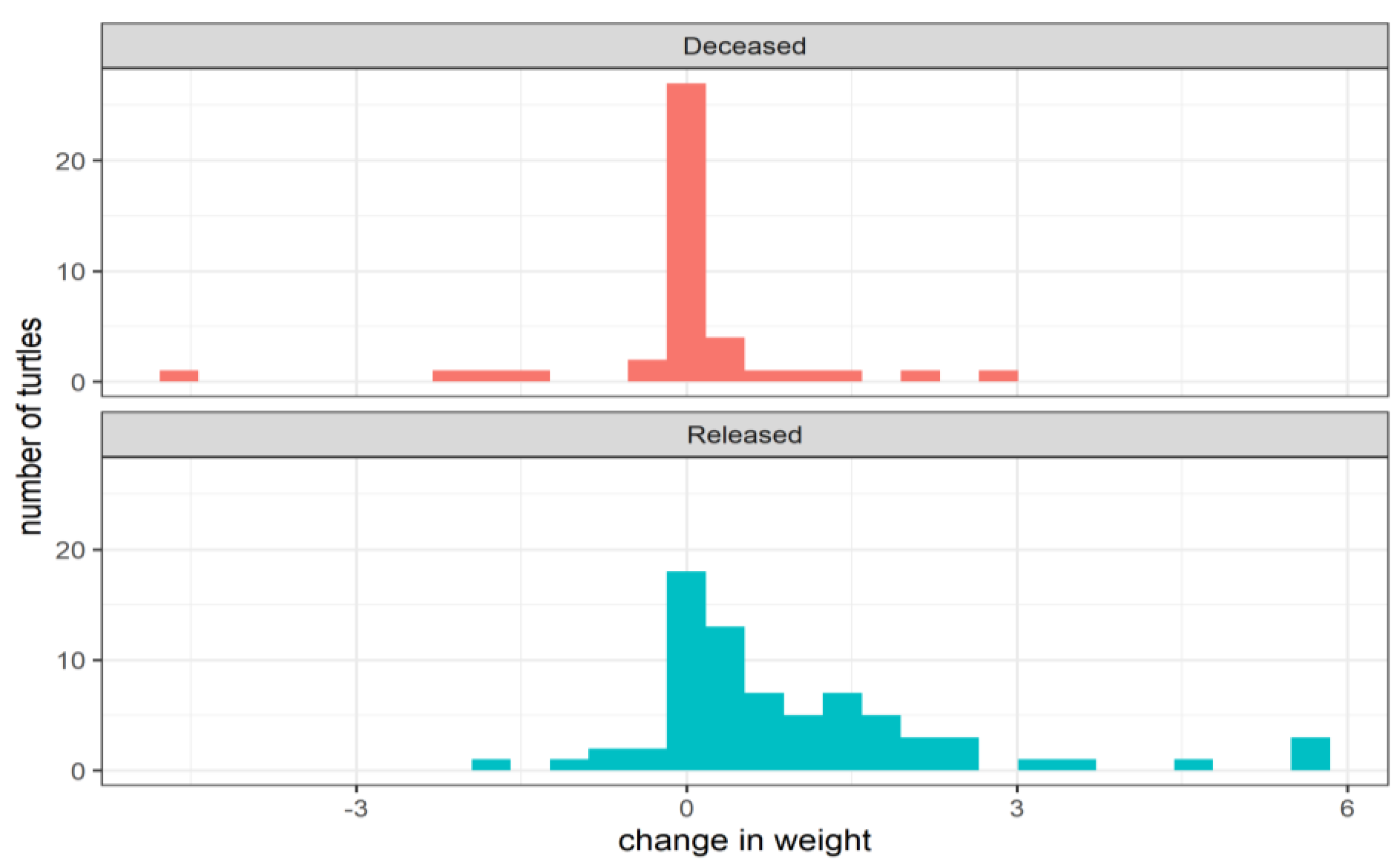

3.11. Change in Body Weight During Clinical Care

Using the individual records, it was possible to assess whether change in body weight over the course of clinical care had any association with overall outcome. Initial exploration with a plot indicated that released patients increased bodyweight (

Figure 13). Change in weight had a highly significant effect on overall outcome (Kruskal-Wallis χ

2 = 23.6, p<0.001).

Figure 13.

Change in body weight between first and last recorded weights during clinical care and overall outcome.

Figure 13.

Change in body weight between first and last recorded weights during clinical care and overall outcome.

4. Discussion

Characteristics of the rescued sea turtles were assessed by species, life-stage, morphometrics and sex. Olive ridley sea turtles represented the majority of species admitted to our facility over this study period at 79%, with just 13.4% hawksbill, 7% green, and one loggerhead sea turtle (<1%). This supports our previous findings which identified 87.7% of 651 injured sea turtles surveyed in the Maldives as olive ridley sea turtles (Lomas, 2019). Although there are very few nesting olive ridley sea turtle populations in the Maldives, it is likely the high proportion rescued reflects their migration pattern, entrapment in marine debris, and/or use of Maldivian foraging grounds. A genetic analysis of entangled olive ridley sea turtles in the Maldives (Stelfox et al. 2020a) suggest that the majority originate from Sri Lanka and eastern India, and whilst this likely has a minimal impact on the eastern Indian population (accounting for 0.48% of this study group) entangled sea turtles accounted for a much larger percentage (48%) of the Sri Lankan population. In Australia Flint et al. (2017) report the most commonly rescued species were green turtles (78.2%), attributed to the known breeding population in this region, whilst olive ridley sea turtles made up a very small proportion of rescued sea turtles there (0.5%).

Over the five years analysed in this study, juveniles were most commonly admitted (47.8%), followed by adults (31.2%) and sub-adults (18.5%), with only a few hatchlings (2.5%). This pattern is consistent with what is known about foraging juveniles, travelling far from their natal beach, drifting in currents to the open ocean (Areu-Grobois and Plotkin, 2008). It is possible that sub-adults and adults migrate from open waters and nesting beaches to use high-nutrient foraging areas within the Maldives. Flint et al. (2017) reported a more striking difference in life-stages seen as 71% of stranded turtles in northern Australia were immature, with 15% large immature, and 12% adults. The size of sea turtles varied with reason for admission, however, size is directly related to life-stage and therefore this variation is more likely a reflection of the life-stage at admission. Exploration into the sex of sea turtles was challenging due to the high proportion of unknown sex (52.2%). It was therefore not possible to establish any significant trends or associations. This is due to difficulties in visually sexing sea turtles until sub-adult or adult life-stages, as described by Hudgins et al.(2017).

When investigating the season of admission to our facility, a trend was seen with peaks of sea turtle admissions occurring during the northeast monsoon seasons over the five-year period (

Figure 3). This supports previous research which found 63% of 129 entangled olive ridley sea turtles between 1988 and 2014 were recorded during the northeast monsoon season in the Maldives (Stelfox et al., 2015). Ocean currents can carry vast quantities of ALDFG, with seasons known to alter its distribution (Stelfox et al., 2015). This could lead to higher levels of entanglement in areas of ALDFG convergence coinciding with foraging grounds. Flint

et al. (2017) found peak sea turtle strandings and rescues occurred towards the end of winter, with high numbers of buoyant sea turtles encountered during this period, while during the summer months, peak numbers of rescued animals were associated with watercraft injuries. In North America and South Africa, Gallini et al. (2021) and Mann-Lang et al. (2020) report the highest numbers of sea turtle rescues occurred during summer months, respectively.

The location of sea turtle rescues was recorded by atoll and written documentation, which was later corroborated with decimal coordinates. The majority of cases were found in the atolls north of Malé, with the majority rescued in or around Baa Atoll. However, Baa Atoll is the location of the ORP Marine Turtle Rescue Centre, and this may reflect increased stranding surveillance opportunities or awareness in this region. There are also two other sea turtle rehabilitation centres within the Maldives where rescued sea turtles may be admitted. These centres communicate frequently, as cases may be shared to provide the most appropriate care for an individual, but their data are not included in this review.

Exploring the reasons for admission to our facility, it should perhaps not come as a surprise that 67.5% (n=106) of sea turtles were admitted due to entanglement, given that approximately 2% of all fishing gear, comprising 2,963 km² of gillnets, 75,049 km² of purse seine nets, 218 km² of trawl nets, 739,583 km of longline mainlines, and more than 25 million pots and traps are lost to the ocean annually (Richardson et al., 2022). This high percentage of entanglement supports previous reports from ORP, with 86.8% of 651 injured turtles found in the Maldives being caused by entanglement (Lomas, 2019). Of the entanglement cases in this study, only 11.2% were entangled due to non-fishing related marine debris, such as plastic sheet or cement bags, 84.1% were caused by ghost nets and 4.7% by other types of fishing gear (line and hooks). Given that most types of net fishing is banned, and bait fisheries together with netting for personal consumption is heavily restricted in Maldives (Fisheries Act of the Maldives (No. 14/2019), this supports and highlights the global issue of ALDFG. Similarly, Gunn et al. (2010) found that 48% of ALDFG investigated in Australia came from other countries, drifting in ocean currents from countries including Thailand and Japan.

The second most common cause for admission was buoyancy syndrome, accounting for 19.8% of admissions over the study period. Compared to a previous study in the Maldives, this admissions feature represents a higher proportion of sea turtles found, as Stelfox et al. (2015) reported that 11.6% of 166 olive ridley sea turtles were found buoyant. However, it is difficult to interpret this increase due to potential differences in descriptions used or subjectivity in recorded reasons for admission. As suggested by Mann-Lang et al. (2020) when assessing sea turtle rescue in South Africa, patients admitted due to entanglement may later be assessed as buoyant when in the clinical centre but not have had this recorded at the time of admission. This would potentially skew the data by reducing the number of patients recorded as found buoyant if they were also entangled at the time of rescue.

The remaining causes for admission represented a minority of the sea turtles admitted to our facility. In contrast, previous research from rescue centres in Australia, South Africa, and America reported higher numbers of admission due to disease, watercraft injuries, predation and buoyancy, with few due to entanglement (Meager and Limpus, 2012; Flint et al., 2017; Mann-Lang et al., 2020). Despite other countries not reporting high numbers of sea turtle rescues due to entanglement, several had a high proportion of unknown reasons for rescue, for example 54% in Australia (Flint et al., 2017). It could be that entangled sea turtles, which had become debilitated through starvation, wounds and infection, may have lost their association with the entangling material by the time they strand or are rescued.

The data were explored to identify any factors associated with a successful outcome following rescue and clinical care, resulting in the release of sea turtles back into the wild. Initially, the time in clinical care until reaching the final outcome of release, or remaining a patient until the standardised endpoint of 30/04/2022, was explored. This gave the range of days in care from 1 to 1,471 days, a mean of 123 days, and median of 36 days. The patient in clinical care for 1,471 days was a patient at the date endpoint of this study and was rehomed to an aquarium for permanent captive care at a subsequent time. Very similar durations in clinical care were found by Mann-Lang et al. (2020) for 51 sea turtles admitted to a rescue centre in South Africa, with a range of 1 to 1,485 days, and a mean of 208 days. In the report by Flint et al. (2017) duration in clinical care was grouped into 1-7 days, 7-28 days, and >28 days, which accounted for 44%, 19.5%, and 36.5% of 2,494 sea turtles, respectively. The findings in this study and Mann-Lang et al. (2020) show a marked difference with those from Flint et al. (2017), and this could represent variations in the reasons for admission, severity of injury/illness, or the treatments required. For example, our study found entangled sea turtles generally had longer durations in clinical care compared to the other reasons for admission.

When looking at the overall outcome for the 157 patients analysed in this study, the results are quite positive, with 60.5% released following clinical care.

Table 13 (Results) shows the comparison of the results from this study with those found in the literature; in general, the findings are supportive of each other.

Initial analysis of outcome with admission variables found no significant associations. This was confirmed with logistic regression, even when the four current patients were removed from the model. When specifically looking at the outcome of entangled sea turtles, those had higher odds of being released compared to deceased. This is suggestive of a good prognosis for sea turtles which are rescued due to entanglement. In contrast, turtles which were buoyant at admission or had buoyancy syndrome had lower odds of being released. These findings were not repeatable for sea turtles which developed buoyancy during rehabilitation, however this could be due to the very low sample size of 11 patients. The association of buoyancy syndrome including patients buoyant at admit, with lower odds of being released is notable, as this condition was recorded in 35% of patients admitted to our facility over the study period. This could be due to secondary disease, which has not been explored within the remit of this study. Flint et al. (2017) reported buoyancy disorders in 14.4% of the 2,494 sea turtles included in their analysis, all of which were released. This could reflect differences in clinical assessments of affected animals but highlights that buoyancy syndrome is an important area for future research.

For a small subset of patients, initial clinical blood test results were explored with descriptive statistics. No significant associations were found between clinical blood results and the patients’ overall outcome, however, the number of sea turtles available to include in the analysis was very small. Clinical blood results do have the potential to provide detailed information on the physiological health of patients admitted and could further assess the health impacts of entanglement and buoyancy syndrome.

Change in weight over time was significantly associated with outcome, as patients gaining weight were more likely to be released. This finding is similar to Baker et al. (2015) who found sea turtles with a larger body size at admission had a greater chance of being released, although this could be associated with the life-stage. In South Africa Mann-Lang et al. (2020) identified that better body condition, not size, of the turtle on arrival was a predictor of clinical success, with more than half of sea turtles admitted in poor condition died while in care (Mann-Lang et al., 2020).

The presence of buoyancy syndrome and entanglement disorders, either at admission or developing during clinical care, highlight the need to continually improve therapies that help restore normal diving, surfacing and feeding behaviour in these species, as suggested by Lutz et al. (2003). Beginning in January 2023, as a result of the findings in this study, we have developed a comprehensive buoyancy syndrome and limb-salvaging program to better treat patients presenting with these conditions and have experienced considerable success with it. Although not the focus of the current study, this comprehensive clinical programme includes novel regenerative and molecular (activated platelet-rich plasma and stem cell therapies), integrative (Class IV laser and acupuncture), behavioural (targeted external weight therapy and kinetic buoy feeding), and surgical (blood pneumopleurodesis) modalities that have allowed our clinicians to successfully treat and release patients that would not have been treatable prior to these interventions. The patient cohort enrolled in this programme is still relatively small (21 animals), but the release rate has increased to nearly 80% from 60% prior to these interventions. These novel approaches may also benefit sea turtles affected by fishing by-catch interactions, where inconsistent or ill deployed mitigation strategies can contribute to sea turtle buoyancy syndrome and subsequent morbidity and mortality. Emerging evidence suggests that sea turtles recovered alive from by-catch entanglements on fishing vessels at sea and replaced back into the ocean by vessel crews may suffer downstream clinicopathological events that lead to subsequent buoyancy syndrome and mortality up to one week after the inciting episode (Parga et al., 2020). These entrapped populations are often sub-adult and adult sea turtles where rapid transfer to clinical facilities and appropriate medical intervention provide the best chance at survival. Although this is the first comprehensive study of its kind, it is not possible to directly attribute any population level impact buoyancy syndrome and entanglement disorders may have on sea turtles, but their widespread global prevalence suggests that these clinical conditions may contribute more to sea turtle morbidity and mortality than is previously thought.

Appendix A

Sample R code used in analysis

For descriptive statistics:

```{r}

intake %>%

summarise(median_length = median(ccl_cm, na.rm = TRUE),

mean_length = mean(ccl_cm, na.rm = TRUE),

variance_length = var(ccl_cm, na.rm = TRUE),

sd_length = sd(ccl_cm, na.rm = TRUE))

```

For chi-squared tests:

chisq.test(firstday$entangled, firstday$flipper_injury_at_admit)

For plots with 95% confidence intervals:

entangled_table <- firstday %>%

group_by(entangled) %>%

summarise(total = sum(!is.na(flipper_injury_at_admit)),

flipper_injury = sum(flipper_injury_at_admit == "y", na.rm = TRUE),

prop = flipper_injury/total,

lci = binom.test(flipper_injury, total)$conf.int(1),

uci = binom.test(flipper_injury, total)$conf.int(2)

gt(entangled_table) %>%

gt::fmt_number(where(is_bare_double), decimals = 2)

entangled_table %>%

mutate(entangled = fct_recode(entangled, "no" = "N", "yes" = "y")) %>%

mutate(entangled = fct_relevel(entangled, "yes")) %>%

ggplot() +

aes(x = entangled, y = prop, ymin = lci, ymax = uci) +

geom_pointrange() +

labs(title = "Entanglement and presence of flipper injuries at admission",

subtitle = "with 95% confidence intervals",

y = "proportion of turtles with fipper injuries") +

theme_light(base_size = 12)

For logistic regression:

mod_buoyo_out = glm(buoyancy_at_admit == "y" ~ outcome_group, family = binomial, data = intake)

parameters(mod_buoyo_out, exponentiate = TRUE)

References

- Abreu-Grobois. A. and Plotkin. P. (IUCN SSC Marine Turtle Specialist Group). (2008). Lepidochelys olivacea. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2008: e.T11534A3292503 [ONLINE]. Available at: [Accessed on 07/12/2021]. [CrossRef]

- Agamuthu, P.; Mehran, S.; Norkhairiyah, A. Marine debris: A review of impacts and global initiatives. Waste Manag. Res. J. a Sustain. Circ. Econ. 2019, 37, 987–1002. [CrossRef]

- Aguilera, M.; Medina-Suárez, M.; Pinós, J.; Liria-Loza, A.; Benejam, L. Marine debris as a barrier: Assessing the impacts on sea turtle hatchlings on their way to the ocean. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2018, 137, 481–487. [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A.A., Tabor, G.M. and Ostfeld, R.S. (2012). Conservation Medicine Ontogeny of an Emerging Discipline, in New Directions in Conservation Medicine: Applied Cases of Ecological Health. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Baker, L.; Edwards, W.; Pike, D.A. Sea turtle rehabilitation success increases with body size and differs among species. Endanger. Species Res. 2015, 29, 13–21. [CrossRef]

- Behera, S., Choudhury, B.C.,Tripathy, B., and Kuppusamy, S. Movements of olive ridley turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea) in the Bay of Bengal, India, determined via satellite telemetry. Chelonian Conservation and Biology, 17: 1. doi: 0.2744/CCB-1245.1.

- Ciccarelli, S.; Valastro, C.; Di Bello, A.; Paci, S.; Caprio, F.; Corrente, M.L.; Trotta, A.; Franchini, D. Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Disease in Sea Turtles (Caretta caretta). Animals 2020, 10, 1355. [CrossRef]

- Duncan, E.; Botterell, Z.; Broderick, A.; Galloway, T.; Lindeque, P.; Nuno, A.; Godley, B. A global review of marine turtle entanglement in anthropogenic debris: a baseline for further action. Endanger. Species Res. 2017, 34, 431–448. [CrossRef]

- Yan, H.-M.; Xia, M.-F.; Wang, Y.; Chang, X.-X.; Yao, X.-Z.; Rao, S.-X.; et al. Efficacy of Berberine in Patients with Non-Alcoholic Fatty Liver Disease. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0134172. [CrossRef]

- Fisheries Act of the Maldives (No. 14/2019): https://fisheries.gov.mv/publications/laws-regulations/7.

- Flint, J.; Flint, M.; Limpus, C.J.; Mills, P. Status of marine turtle rehabilitation in Queensland. PeerJ 2017, 5, e3132. [CrossRef]

- Franzen-Klein, D.; Burkhalter, B.; Sommer, R.; Weber, M.; Zirkelbach, B.; Norton, T. Diagnosis and Management of Marine Debris Ingestion and Entanglement by Using Advanced Imaging and Endoscopy in Sea Turtles. J. Herpetol. Med. Surg. 2020, 30, 74–87. [CrossRef]

- Gallini, S.H.; Di Girolamo, N.; Hann, E.; Paluch, H.; DiGeronimo, P.M. Outcomes of 4819 cases of marine animals presented to a wildlife rehabilitation center in New Jersey, USA (1976–2016). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 1–7. [CrossRef]

- Godley, B.J.; Broderick, A.C.; Colman, L.P.; Formia, A.; Godfrey, M.H.; Hamann, M.; Nuno, A.; Omeyer, L.C.M.; Patrício, A.R.; Phillott, A.D.; et al. Reflections on sea turtle conservation. Oryx 2020, 54, 287–289. [CrossRef]

- Godoy, D.; Stockin, K. Anthropogenic impacts on green turtles Chelonia mydas in New Zealand. Endanger. Species Res. 2018, 37, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- Gunn, R., Hardesty, B.D. and Butler, J. (2010). Tackling ‘ghost nets’: Local solutions to a global issue in northern Australia. Ecological Management and Restoration, 11(2): 88–98.

- Hochscheid, S.; Bentivegna, F.; Speakman, J.R. The dual function of the lung in chelonian sea turtles: buoyancy control and oxygen storage. J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2003, 297, 123–140. [CrossRef]

- Hudgins, J., Mancini, A. and Ali, K. (2017). Marine turtles of the Maldives – A Field Identification Guide. Gland, Switzerland: IUCN and Government of Maldives in collaboration with USAID. ISBN: 978-2-8317-1856-9.

- Hunt, K.E.; Innis, C.J.; Merigo, C.; Rolland, R.M. Endocrine responses to diverse stressors of capture, entanglement and stranding in leatherback turtles (Dermochelys coriacea). Conserv. Physiol. 2016, 4, cow022. [CrossRef]

- IOSEA (2009). Marine Turtle MOU Text including Conservation and Management Plan, Objective [ONLINE]. Available at: https://www.cms.int/iosea-turtles/en/page/mou-text-cmp [Accessed on: 02/05/2022].

- IUCN. The International Union for Conservation of Nature’s Red List of Threatened Species (IUCN) Red List of Threatened Species, version 2022. https://www.iucnredlist.org/. (accessed on 6 November 2022).

- Sul, J.A.I.D.; Santos, I.R.; Friedrich, A.C.; Matthiensen, A.; Fillmann, G. Plastic Pollution at a Sea Turtle Conservation Area in NE Brazil: Contrasting Developed and Undeveloped Beaches. Estuaries Coasts 2011, 34, 814–823. [CrossRef]

- Kühn, S. and van Franeker, J.A. (2020). Quantitative overview of marine debris ingested by marine megafauna. Marine Pollution Bulletin, 151: 110858 [ONLINE]. Available at: https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S0025326X19310148?via%3Dihub [Accessed on 30/04/2022].

- Law, K.L. (2016). Plastics in the Marine Environment. The Annual Review of Marine Science, 9: 205–229.

- Liguori, B.L.; Polyak, M.M.R.; Clark, S.A.; Sabater, A.N.; Clasen, T.B.; Manire, C.A. Transplastron Enterocentesis to Manage Buoyancy Disorder in an Adult Loggerhead Sea Turtle (Caretta caretta). J. Herpetol. Med. Surg. 2021, 31. [CrossRef]

- Lomas, C. (2019). Conservation and rehabilitation of sea turtles in the Maldives. Olive Ridley Project [ONLINE]. Available at: https://oliveridleyproject.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/conservation-rehabilitation-sea-turtles-maldives_lomas_testudo-vol9_no2_-bcg.pdf [Accessed on 27th May 2021].

- López-Martínez, S.; Morales-Caselles, C.; Kadar, J.; Rivas, M.L. Overview of global status of plastic presence in marine vertebrates. Glob. Chang. Biol. 2020, 27, 728–737. [CrossRef]

- Lutz, P., Musick, J. and Wyneken, J. (2003). The biology of sea turtles, volume II. Series: Marine Biology Series. Edited by: Lutz, P., Musick, J. and Wyneken, J. CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2003. ISBN 0-8493-1123-3.

- Macfadyen, G., Huntington, T. and Cappell, R. (2009). Abandoned, lost or otherwise discarded fishing gear. UNEP Regional Seas Reports and Studies, No. 185: FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper, No. 523. Rome, UNEP/FAO [ONLINE]. Available at: https://www.fao.org/3/i0620e/i0620e00.htm [Accessed 09/04/2022].

- Witherington, B.E. Sea Turtles in Context: Their Life History and Conservation. In Sea Turtle Health and Rehabilitation; Manire, C.A., Norton, T.M., Stacy, B.A., Innis, C.J., Harms, C.A., Eds.; J. Ross Publishing, Inc.: Plantation, FL, USA, 2017; pp 3–24, ISBN 978-160-427-099-0.

- Mann-Lang, J., Pather, M., Naidoo, T. and Ntombela, J. (2020). A review of stranded marine turtles treated by Ushaka sea world (Saambr) in Durban, South Africa. Indian Ocean Turtle Newsletter, 32: 17-24.

- Meager, J.J. and Limpus, C. (2012). Marine wildlife stranding and mortality database annual report 2011 lII. Marine Turtle. Conservation Technical and Data Report 2012 (3):1-46.

- Miguel, C.; Becker, J.H.; de Freitas, B.S.; Touguinha, L.B.A.; Salvador, M.; Oliveira, G.T. Physiological effects of incidental capture and seasonality on juvenile green sea turtles (Chelonia mydas). J. Exp. Mar. Biol. Ecol. 2020, 533. [CrossRef]

- Nelms, S.E.; Duncan, E.M.; Broderick, A.C.; Galloway, T.S.; Godfrey, M.H.; Hamann, M.; Lindeque, P.K.; Godley, B.J. Plastic and marine turtles: a review and call for research. ICES J. Mar. Sci. 2015, 73, 165–181. [CrossRef]

- Nelms, S., Fuentes, M. and Beckwith, V. (2018). Sea turtles and the perils of plastics. Current Conservation, 12(2): 6–10.

- NOAA (2019). Sea Turtles: What do you know about one of the world's most endangered species? National Ocean Service, News [ONLINE]. Available at: https://oceanservice.noaa.gov/news/june15/sea-turtles.html [Accessed on: 02/06/2021].

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) (2021). Species Directory: Olive Ridley Turtle [ONLINE]. Available at: https://www.fisheries.noaa.gov/species/olive-ridley-turtle#:~:text=The%20olive%20ridley%20is%20mainly%20a%20pelagic%20%28open,breeding%20and%20nesting%20grounds%2C%20back%20to%20pelagic%20foraging [Accessed on 08/12/2021].

- Norton, T.M. (2005). Chelonian Emergency and Critical Care. Seminars in Avian and Exotic Pet Medicine, 14(2): 106–130.

- Norton, T. and Mettee, N. (2020). Marine Turtle Trauma Response Procedures: A Veterinary Guide, Buoyancy Disorders [ONLINE]. Available at: http://www.seaturtleguardian.org/physical-exam/19- veterinary-guide/123-buoyancy-disorders [Accessed 30/04/2022].

- Olive Ridley Project (ORP) (2021). Olive Ridley Turtle. Olive Ridley Project, Sea turtles of the world [ONLINE]. Available at: https://oliveridleyproject.org/sea-turtles-of-the-world/olive-ridley-turtle [Accessed on 23/01/2022].

- Olive Ridley Project (ORP) (2022). About Us: The Olive Ridley Project Story [ONLINE]. Available at: https://oliveridleyproject.org/about-us [Accessed on 07/04/2022].

- Parga, M.L.; Crespo-Picazo, J.L.; Monteiro, D.; García-Párraga, D.; Hernandez, J.A.; Swimmer, Y.; Paz, S.; Stacy, N.I. On-board study of gas embolism in marine turtles caught in bottom trawl fisheries in the Atlantic Ocean. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 1–9. [CrossRef]

- s41598-020-62355-7.

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023. Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 11 December 2023).

- RStudio Team. RStudio: Integrated Development for R. RStudio, PBC; Boston, MA, USA, 2020. Available online: http://www.rstudio.com/ (accessed on).

- Ramakrishnan, A., Palanivelrajan, M., Thangapadiyan, M., Sumathi, D. and Senthilkumar, K. (2018). Haematology analysis of rescued olive Ridley Sea Turtles (Lepidochelys olivacea). Journal of Entomology and Zoology Studies, 6(3): 1128 – 1131.

- Reichart., H.A. (1993). Synopsis of biological data on the olive ridley sea turtle Leipidochelys oivacea (Eschscholtz, 1829) in the western Atlantic. NOAA Technical Memorandum, NMFS-SEFSC-336, 78pp [ONLINE]. Available at: https://repository.library.noaa.gov/view/noaa/6183 [Accessed on 23/01/2021].

- Richardson, K.; Asmutis-Silvia, R.; Drinkwin, J.; Gilardi, K.V.; Giskes, I.; Jones, G.; O'Brien, K.; Pragnell-Raasch, H.; Ludwig, L.; Antonelis, K.; et al. Building evidence around ghost gear: Global trends and analysis for sustainable solutions at scale. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2019, 138, 222–229. [CrossRef]

- Richardson, K.; Hardesty, B.D.; Vince, J.; Wilcox, C. Global estimates of fishing gear lost to the ocean each year. Sci. Adv. 2022, 8, eabq0135. [CrossRef]

- Savage, A.C.N.P. and Cazabon-Mannette, M. (2020). Sea Turtle Conservation: Tackling ‘Floating Syndrome’ A Caribbean Perspective. Living World, Journal of The Trinidad and Tobago Field Naturalists’ Club, 2020: 59–71.

- Schmitt, T.L.; Munns, S.; Adams, L.; Hicks, J.; Schmitt, D.T.L.; D.V.M.; Ph.D. THE USE OF SPIROMETRY TO EVALUATE PULMONARY FUNCTION IN OLIVE RIDLEY SEA TURTLES (LEPIDOCHELYS OLIVACEA) WITH POSITIVE BUOYANCY DISORDERS. J. Zoo Wildl. Med. 2013, 44, 645–653. [CrossRef]

- Senko, J.; Nelms, S.; Reavis, J.; Witherington, B.; Godley, B.; Wallace, B. Understanding individual and population-level effects of plastic pollution on marine megafauna. Endanger. Species Res. 2020, 43, 234–252. [CrossRef]

- Shanker, K.; Pandav, B.; Choudhury, B. An assessment of the olive ridley turtle (Lepidochelys olivacea) nesting population in Orissa, India. Biol. Conserv. 2003, 115, 149–160. [CrossRef]

- Shankar, D.; Vinayachandran, P.; Unnikrishnan, A. The monsoon currents in the north Indian Ocean. Prog. Oceanogr. 2002, 52, 63–120. [CrossRef]

- Stelfox, M. (2015). The impact of ghost nets on marine species in the Maldives. IUCN Maldives Marine Newsletter, 3: 13–14.

- Stelfox, M. (2018). Ghost gear, the silent killers in our oceans. Current Conservation, 12(2): 18–19.

- Stelfox, M.; Bulling, M.; Sweet, M. Untangling the origin of ghost gear within the Maldivian archipelago and its impact on olive ridley (Lepidochelys olivacea) populations. Endanger. Species Res. 2019, 40, 309–320. [CrossRef]

- Stelfox, M.; Burian, A.; Shanker, K.; Rees, A.F.; Jean, C.; Willson, M.S.; Manik, N.A.; Sweet, M. Tracing the origin of olive ridley turtles entangled in ghost nets in the Maldives: A phylogeographic assessment of populations at risk. Biol. Conserv. 2020, 245. [CrossRef]

- Stelfox, M.; Lett, C.; Reid, G.; Souch, G.; Sweet, M. Minimum drift times infer trajectories of ghost nets found in the Maldives. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2020, 154, 111037. [CrossRef]

- Stelfox, M.; Hudgins, J.; Sweet, M. A review of ghost gear entanglement amongst marine mammals, reptiles and elasmobranchs. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2016, 111, 6–17. [CrossRef]

- Stephen, C. TOWARD A MODERNIZED DEFINITION OF WILDLIFE HEALTH. J. Wildl. Dis. 2014, 50, 427–430. [CrossRef]

- Stranahan, L.; Alpi, K.M.; Passingham, R.K.; Kosmerick, T.J.; Lewbart, G.A.; Lauren Stranhana, Kristine M. Alpi, MLS, MPHb, Ronald K. Passinghamc, Todd J. Kosmerickd, and Gregory A. Lewbart, MS, VMD, Dipl. ACZMe,* aNorth Carolina State University bNorth Carolina State University cNorth Carolina State University dNorth Carolina Sta; Mls; Vmd, D.A. Descriptive Epidemiology for Turtles Admitted to the North Carolina State University College of Veterinary Medicine Turtle Rescue Team. J. Fish Wildl. Manag. 2016, 7, 520–525. [CrossRef]

- Tabor, G.M. (2002). Defining Conservation Medicine, in Conservation Medicine: Ecological Health in Practice. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Wilcox, C.; Hardesty, B.; Sharples, R.; Griffin, D.; Lawson, T.; Gunn, R. Ghostnet impacts on globally threatened turtles, a spatial risk analysis for northern Australia. Conserv. Lett. 2013, 6, 247–254. [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Curved carapace length of turtles at admission, grouped by species.

Figure 1.

Curved carapace length of turtles at admission, grouped by species.

Figure 2.

Curved carapace length and weight of sea turtles at admission grouped by life-stage.

Figure 2.

Curved carapace length and weight of sea turtles at admission grouped by life-stage.

Figure 3.

Month of sea turtle admission grouped by season.

Figure 3.

Month of sea turtle admission grouped by season.

Figure 4.

Atoll where the sea turtle was found.

Figure 4.

Atoll where the sea turtle was found.

Figure 5.

Location of sea turtle rescue using decimal degree coordinates.

Figure 5.

Location of sea turtle rescue using decimal degree coordinates.

Figure 6.

Reason for admission to ORP Marine Turtle Rescue Centre and sea turtle species.

Figure 6.

Reason for admission to ORP Marine Turtle Rescue Centre and sea turtle species.

Figure 7.

Cause of sea turtle entanglement when found.

Figure 7.

Cause of sea turtle entanglement when found.

Figure 8.

(a) Distribution of sea turtles’ curved carapace length by reason for admission. (b) Distribution of sea turtles’ bodyweight by reason for admission. The centre of each boxplot represents the median value with the box covering the interquartile range (from the lower to the upper quartile), and the line indicating the range.

Figure 8.

(a) Distribution of sea turtles’ curved carapace length by reason for admission. (b) Distribution of sea turtles’ bodyweight by reason for admission. The centre of each boxplot represents the median value with the box covering the interquartile range (from the lower to the upper quartile), and the line indicating the range.

Figure 9.

Total number of days in clinical care until final outcome.

Figure 9.

Total number of days in clinical care until final outcome.

Figure 10.

Total number of days in clinical care, grouped by reason for admission. The centre of each boxplot is the median value, with the box covering from the lower quartile to upper quartile, and the line showing the range of values.

Figure 10.

Total number of days in clinical care, grouped by reason for admission. The centre of each boxplot is the median value, with the box covering from the lower quartile to upper quartile, and the line showing the range of values.

Figure 11.

Total days in clinical care and overall outcome.

Figure 11.

Total days in clinical care and overall outcome.

Figure 12.

(a) Sea turtles buoyant at admission and overall outcome. (b) Sea turtles with buoyancy syndrome and overall outcome.

Figure 12.

(a) Sea turtles buoyant at admission and overall outcome. (b) Sea turtles with buoyancy syndrome and overall outcome.

Figure 13.

Overall outcome and entanglement.

Figure 13.

Overall outcome and entanglement.

Table 1.

Description of variables used in data analysis and data sheet used with count of sea.

Table 1.

Description of variables used in data analysis and data sheet used with count of sea.

| Variable |

Description |

Type |

Sheet |

| Reason for admission |

seven categories - "entangled", "floating", "debilitated", "previously kept as a pet", "animal attack", "wound", "boat strike" |

Categorical |

Intake sheet (157 patients) |

| Species |

four categories for species admitted to the rescue centre - "olive ridley", "hawksbill", "green", "loggerhead" |

Categorical |

| CCL |

curved carapace length measured in cm |

Continuous |

| Weight |

first recorded weight in kg |

Continuous |

| Life-stage |

four categories - "hatchling", "juvenile", "sub-adult", or "adult" based on CCL measurement |

Categorical |

| Sex |

three categories - "male", "female", or "unknown" |

Categorical |

| Season |

three categories based on description of the seasons in the literature - "northeast" monsoon (December to March), "southwest" monsoon (May to October), and "transitional months" (April and November) |

Categorical |

| Atoll found |

name of the Atoll (group of islands) where the turtle was found, of which there are 17 different Atoll's recorded |

Categorical |

| Location found |

GPS coordinates for where the sea turtle was found, using Google maps based on the written description of the location the sea turtle was found |

Continuous |

| Total days in centre |

total number of days in clinical care until outcome (including time spent at other centres) |

Continuous |

| Outcome |

three categories - "current patient", "released" and "deceased" |

Categorical |

| Entangled |

sea turtles entangled when found - yes "y", or no "n" |

Categorical |

| Entanglement cause |

five categories – “ghost nets”, “marine debris”, “ghost nets and marine debris”, “fishing gear” and “unknown” |

Categorical |

| Ghost net |

sea turtle where ghost nets were a feature when found - yes "y", or no "n" |

Categorical |

| Buoyant at admit |

sea turtles with positive buoyancy on admission, or described when first assessed at the rescue centre - yes "y", or no "n" |

Categorical |

Table 2.

Description of variables used in data analysis and data sheet used with count of patients.

Table 2.

Description of variables used in data analysis and data sheet used with count of patients.

| Variable |

Description |

Type |

Sheet |

| Flipper injury at admission |

patients with any recorded flipper injuries at admission (superficial or deep wounds, fractures, or partial amputations) - yes "y", or no "n" |

Categorical |

Individual records (119 patients) |

| Missing flipper at admission |

patients missing an entire flipper at admission - yes "y", or no "n" |

Categorical |

| Amputation surgery |

patients having surgical amputation of a flipper(s) - yes "y", or no "n" |

Categorical |

| Surgeries |

number of surgeries undertaken using either sedation and/or general anaesthesia - "0", "1", "2", "3", or "4" |

Discrete |

| Topical wound care |

use of topical medications to treat wounds - yes "y", or no "n" |

Categorical |

| Buoyancy syndrome |

patients with positive buoyancy during their time in clinical care - yes "y", or no "n" |

Categorical |

| Buoyancy syndrome not at admit |

patients which were not positively buoyant at admission, but developed buoyancy during clinical care - yes "y", or no "n" |

Categorical |

| Coelomocentesis |

use of needle and syringe to remove air trapped in coelomic cavity - yes "y", or no "n" |

Categorical |

| Osteomyelitis |

patients which had osteomyelitis (a bone infection) diagnosed during clinical care - yes "y", or no "n" |

Categorical |

| Initial packed cell volume (PCV) |

first recorded blood result for percentage of red blood cells (45 patients) |

Continuous |

| Last PCV |

last recorded blood result for percentage of red blood cells (20 patients) |

Continuous |

| Initial Total Protein (TP) |

first recorded blood result for total protein (41 patients) |

Continuous |

| Last TP |

last recorded blood result for total protein (18 patients) |

Continuous |

| Initial White Cell Count (WCC) |

first recorded blood result for number of white blood cells (16 patients) |

Continuous |

| Last WCC |

last recorded blood result for number of white blood cells (8 patients) |

Continuous |

| Change in weight |

last recorded weight minus the first recorded weight, measured in kg (118 patients) |

Continuous |

Table 3.

Summary of patient characteristics by species, descriptive statistics and total count.

Table 3.

Summary of patient characteristics by species, descriptive statistics and total count.

| |

Species |

Totals for all species |

| |

Olive ridley |

Hawksbill |

Green |

Loggerhead |

| Number of patients |

124 |

21 |

11 |

1 |

157 |

| |

|

| Life-stage (%) |

|

|

|

|

|

| Hatchling |

0.0 |

0.6 |

1..9 |

0.0 |

4 |

| Juvenile |

32.5 |

10.2 |

4.5 |

0.6 |

75 |

| Sub-adult |

16.6 |

1.3 |

0.6 |

0.0 |

29 |

| Adult |

29.9 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

0.0 |

49 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Sex (%) |

|

| Male |

5.7 |

1.3 |

1.9 |

0.0 |

14 |

| Female |

36.9 |

0.6 |

1.3 |

0.0 |

61 |

| Unknown |

36.3 |

11.5 |

3.8 |

0.6 |

82 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Weight (kg) |

|

| Mean |

16.8 |

7.38 |

8.54 |

0.4 |

14.9 |

| Median |

15.0 |

4.08 |

4.50 |

0.4 |

13.1 |

| Standard deviation |

10.0 |

7.44 |

11.4 |

N/A |

10.5 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| CCL (cm) |

|

| Mean |

53.2 |

37.6 |

30.4 |

14.0 |

49.2 |

| Median |

55.4 |

35.0 |

25.0 |

14.0 |

53.0 |

| Standard deviation |

12.4 |

16.7 |

23.4 |

N/A |

16.0 |

Table 4.

Reason for admission by species and total count.

Table 4.

Reason for admission by species and total count.

| Reason for admission |

Species |

Totals for all species |

Count (%) |

| Olive ridley |

Hawksbill |

Green |

Loggerhead |

| Entangled |

99 |

5 |

2 |

0 |

106 |

67.5 |

| Floating |

20 |

10 |

1 |

0 |

31 |

19.7 |

| Debilitated |

3 |

4 |

0 |

0 |

7 |

4.5 |

| Previously kept as pet |

0 |

0 |

4 |

1 |

5 |

3.2 |

| Animal attack |

0 |

1 |

3 |

0 |

4 |

2.6 |

| Wound |

1 |

1 |

1 |

0 |

3 |

1.9 |

| Boat strike |

1 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

0.6 |

| Totals |

124 |

21 |

11 |

1 |

157 |

100 |

Table 5.

Outcome for sea turtle patients admitted to the ORP Marine Turtle Rescue Centre after clinical care.

Table 5.

Outcome for sea turtle patients admitted to the ORP Marine Turtle Rescue Centre after clinical care.

| Outcome |

Number of turtles |

Count (%) |

| Released |

95 |

60.5 |

| Deceased |

58 |

36.9 |

| Current patient |

4 |

2.5 |

Table 6.

Overview of data used in statistical analysis for entanglement and buoyancy syndrome cases.

Table 6.

Overview of data used in statistical analysis for entanglement and buoyancy syndrome cases.

| Variable |

Number of patients |

% |

Data sheet |

| Entangled |

Yes |

107 |

68.2 |

Intake

(157) |

| |

No |

50 |

31.8 |

| Buoyant at admit |

Yes |

55 |

35.0 |

| |

No |

102 |

65.0 |

| Buoyancy syndrome |

Yes |

55 |

46.2 |

Individual

(119) |

| |

No |

64 |

53.8 |

| Buoyancy syndrome not at admit |

Yes |

11 |

9.2 |

| |

No |

108 |

90.8 |

| Flipper injury at admit |

Yes |

74 |

62.2 |

| |

No |

45 |

37.8 |

| Missing flipper at admit |

Yes |

14 |

11.8 |

| |

No |

105 |

88.2 |

| Osteomyelitis |

Yes |

14 |

11.8 |

| |

No |

105 |

88.2 |

| Surgeries |

0 |

33 |

28.4 |

| |

1 |

63 |

54.3 |

| |

2 |

14 |

12.1 |

| |

3 |

5 |

4.3 |

| |

4 |

1 |

0.9 |

| |

N/A |

3 |

N/A |

| Amputation surgery |

Yes |

48 |

40.0 |

| |

No |

71 |

60.0 |

| Topical wound care |

Yes |

59 |

49.6 |

| |

No |

60 |

50.4 |

| Coelomocentesis |

Yes |

15 |

12.6 |

| |

No |

104 |

87.4 |

Table 7.

Statistical analysis of admission variables following clinical care with the overall outcome as released.

Table 7.

Statistical analysis of admission variables following clinical care with the overall outcome as released.

| |

Logistic regression |

| Variable |

Odds ratio |

LCI |

UCI |

p-value |

Reason for admission

Animal attack as reference |

Boat strike |

1.42e-06 |

- |

9.94e+59 |

0.988 |

| Debilitated |

1.5 |

0.09 |

42.10 |

0.779 |

| Entangled |

5.13 |

0.63 |

105.76 |

0.163 |

| Floating |

2.17 |

0.25 |

46.58 |

0.523 |

| Previous pet |

4.5 |

0.30 |

137.89 |

0.308 |

| Wound |

1.5 |

0.04 |

57.09 |

0.810 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Species |

Green |

0.60 |

0.16 |

2.08 |

0.413 |

| Olive ridley as reference |

Hawksbill |

0.54 |

0.20 |

1.36 |

0.192 |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

| Life-stage |

Sub-adult |

1.31 |

0.55 |

3.25 |

0.546 |

| Juvenile as reference |

Adult |

1.01 |

0.48 |

2.13 |

0.975 |

Table 8.

Statistical analysis of associations with overall outcome following rehabilitation.

Table 8.

Statistical analysis of associations with overall outcome following rehabilitation.

| |

Logistic regression |

| Variable |

Odds ratio |

LCI |

UCI |

p-value |

| Entangled |

Current patient |

2.61 |

0.31 |

54.54 |

0.417 |

| Deceased outcome as reference |

Released |

2.89 |

1.44 |

5.89 |

0.003 |

| Buoyant at admit |

Current patient |

0.36 |

0.02 |

2.98 |

0.385 |

| Deceased outcome as reference |

Released |

0.40 |

0.20 |

0.80 |

0.009 |

| Buoyancy syndrome |

Current patient |

0.34 |

0.02 |

3.82 |

0.394 |

| Deceased outcome as reference |

Released |

0.44 |

0.20 |

0.94 |

0.036 |

| Buoyancy syndrome not at admit |

Current patient |

8.31-07 |

- |

- |

0.992 |

| Deceased outcome as reference |

Released |

1.58 |

0.43 |

7.51 |

0.520 |

Table 9.

Statistical analysis of associations between entanglement and buoyancy at admission with the overall outcome released.

Table 9.

Statistical analysis of associations between entanglement and buoyancy at admission with the overall outcome released.

| |

Logistic regression |

| Variable |

Odds ratio |

LCI |

UCI |

p-value |

Entangled

(not entangled as reference) |

1.62 |

0.73 |

3.59 |

0.232 |

Buoyant at admission

(not buoyant at admit as reference) |

0.43 |

0.20 |

0.94 |

0.034 |

Table 10.

Descriptive statistics for clinical blood results.

Table 10.

Descriptive statistics for clinical blood results.

| |

First blood draw |

Last blood draw |

| Blood parameter (unit) |

Mean |

Median |

Standard deviation |

Mean |

Median |

Standard deviation |

| PCV (%) |

21.0 |

21.0 |

8.17 |

21.1 |

20.0 |

6.40 |

| TP (g/dL) |

23.7 |

26.0 |

17.0 |

27.0 |

30.5 |

21.3 |

| WCC (103/ul) |

10.50 |

8.40 |

6.47 |

9.47 |

7.50 |

6.98 |

Table 11.

Summary descriptive statistics for initial blood test results by outcome group and association with overall outcome using a Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared test.

Table 11.

Summary descriptive statistics for initial blood test results by outcome group and association with overall outcome using a Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared test.

| Clinical blood parameter |

Outcome group |

Mean |

Standard deviation |

Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared |

| PCV (%) |

Released |

20.4 |

7.56 |

0.68

P=0.713 |

| Deceased |

22.1 |

9.3 |

| Current patient |

21 |

11.3 |

| Total protein (g/dL) |

Released |

22.5 |

6.5 |

2.99

p=0.225 |

| Deceased |

27.8 |

17.7 |

| Current patient |

2.4 |

N/A |

| WCC (103/ul) |

Released |

10.29 |

5.67 |

1.19

P=0.552 |

| Deceased |

12.03 |

8.60 |

| Current patient |

5.00 |

N/A |

Table 12.

Statistical analysis of associations between change in clinical blood parameters with overall outcome following clinical care.

Table 12.

Statistical analysis of associations between change in clinical blood parameters with overall outcome following clinical care.

| Blood parameter |

Kruskal-Wallis chi-squared |

p-value |

| PCV |

1.0957 |

0.578 |

| TP |

2.5352 |

0.282 |

| WCC |

1.7143 |

0.424 |

Table 13.

Comparison of data from this study and data from the literature on sea turtle rescue and clinical care outcomes.

Table 13.

Comparison of data from this study and data from the literature on sea turtle rescue and clinical care outcomes.

| Location |

Year(s) |

Number of turtles |

Outcome (%) |

Reference |

| ORP Marine Turtle Rescue Centre, Baa Atoll, Maldives |

2017 – 2022 |

157 |

60.5 released

36.9 deceased

2.6 current patients |

This study |

| Queensland, Australia |

2011 |

248 |

57.7 released |

Meager and Limpus (2012) |

| Florida, USA |

1986 – 2004 |

1,700 |

36.8 released

61.5 deceased

1.6 in captivity |

Baker et al. (2015) |

| Queensland, Australia |

1996 – 2013 |

2,970 |

39.0 released

61.0 deceased |

Flint et al. (2017) |

| Durban, South Africa |

2007 – 2019 |

51 |

51.0 released

35.3 deceased

13.7 in captivity |

Mann-Lang et al. (2020) |

| New Jersey, USA |

1976 – 2016 |

285 |

64.6 released |

Gallini et al. (2021) |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).