Submitted:

04 May 2025

Posted:

05 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

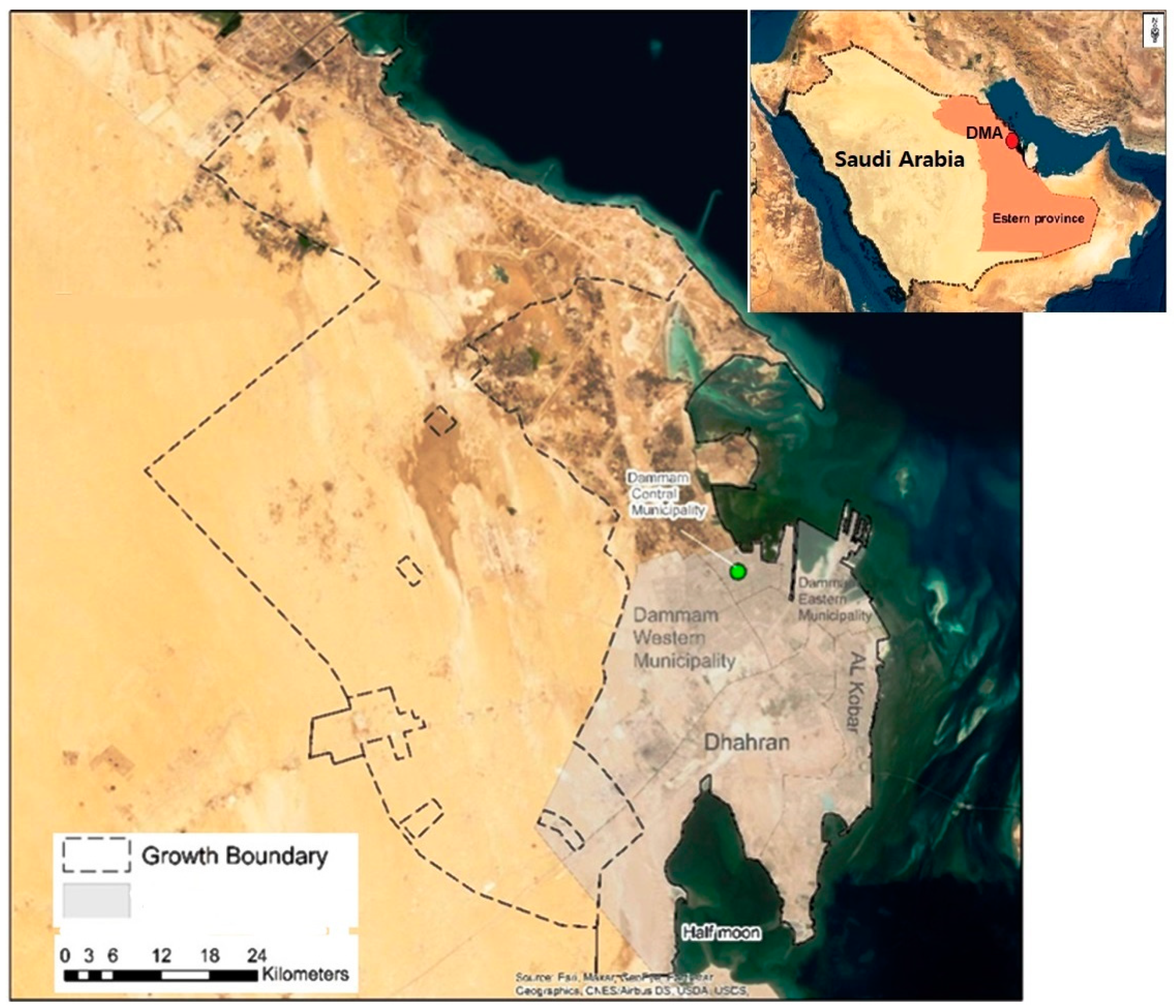

2.1. Study Setting

2.2. Data Collection and Analysis

- a)

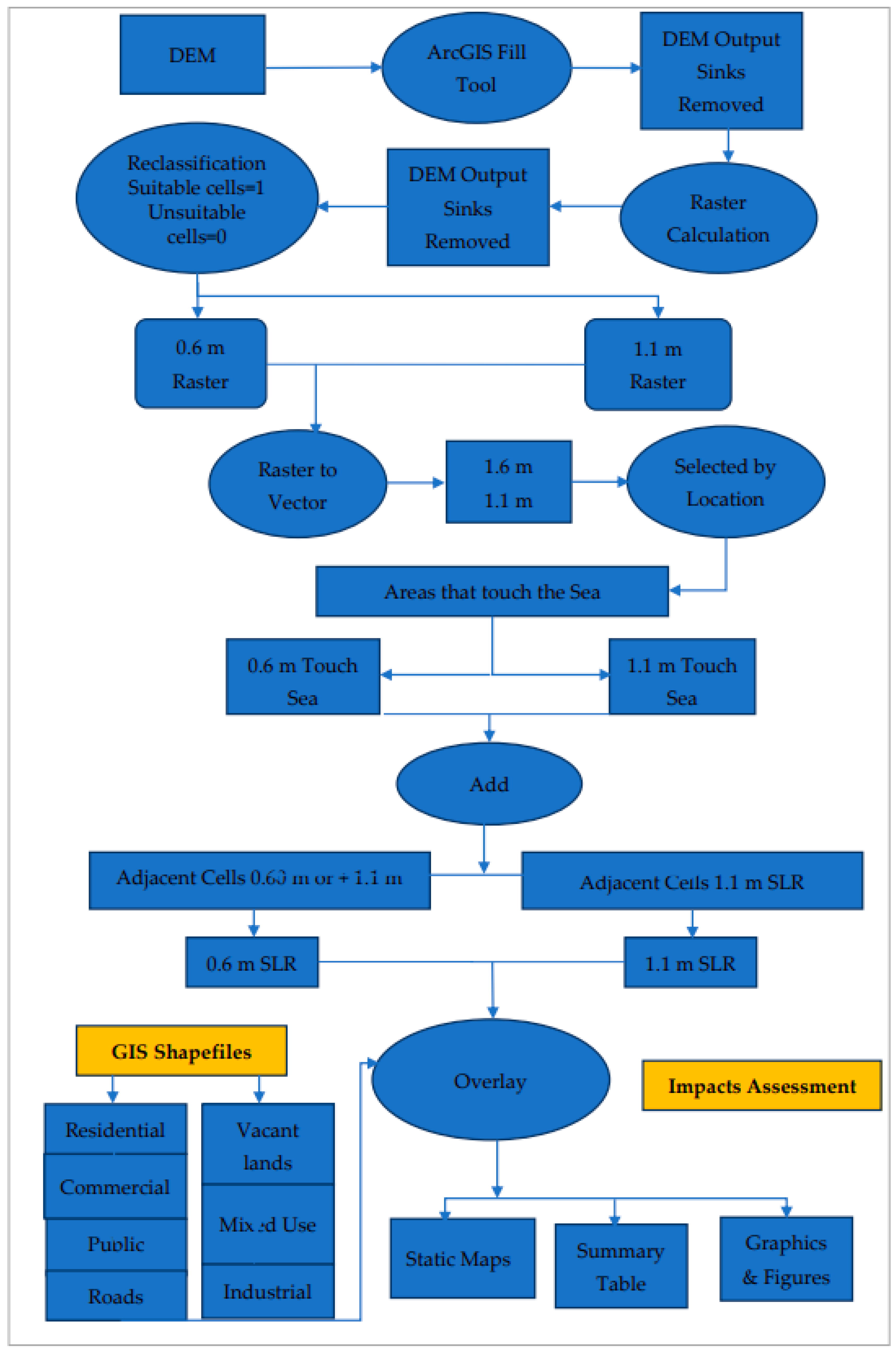

- Processing the DEM: The DEM generated had sinks with negative values. To ensure reliable results, the sinks were eliminated using the fill tool in ArcGIS, converting cells with negative values into meaningful altitudes.

- b)

- Raster calculation and reclassification: Map algebraic expressions were used to extract cells of interest using the raster calculator in ArcGIS. New rasters were produced based on elevations from 0.6 to 1.1 meters. These rasters were crucial for simulating the inundated susceptible zones. Reclassification was performed to categorize cells with 0 values as No-Data, while cells with 1 value were included in the simulation. This process was replicated for both rasters.

- c)

- Vectorization and SLR scenarios: The reclassified rasters were vectorized for easy manipulation and analysis. The newly created vectors were selected based on their location using the Select by Location function in ArcGIS, specifically zones touching the sea boundary. This process was repeated for vectors, assigning the 0.6-meter vector to the 0.6-meter SLR scenario and selecting the 1.1-meter zones touching the sea boundary plus the 0.6-meter SLR for the 1.1-meter SLR scenario.

- d)

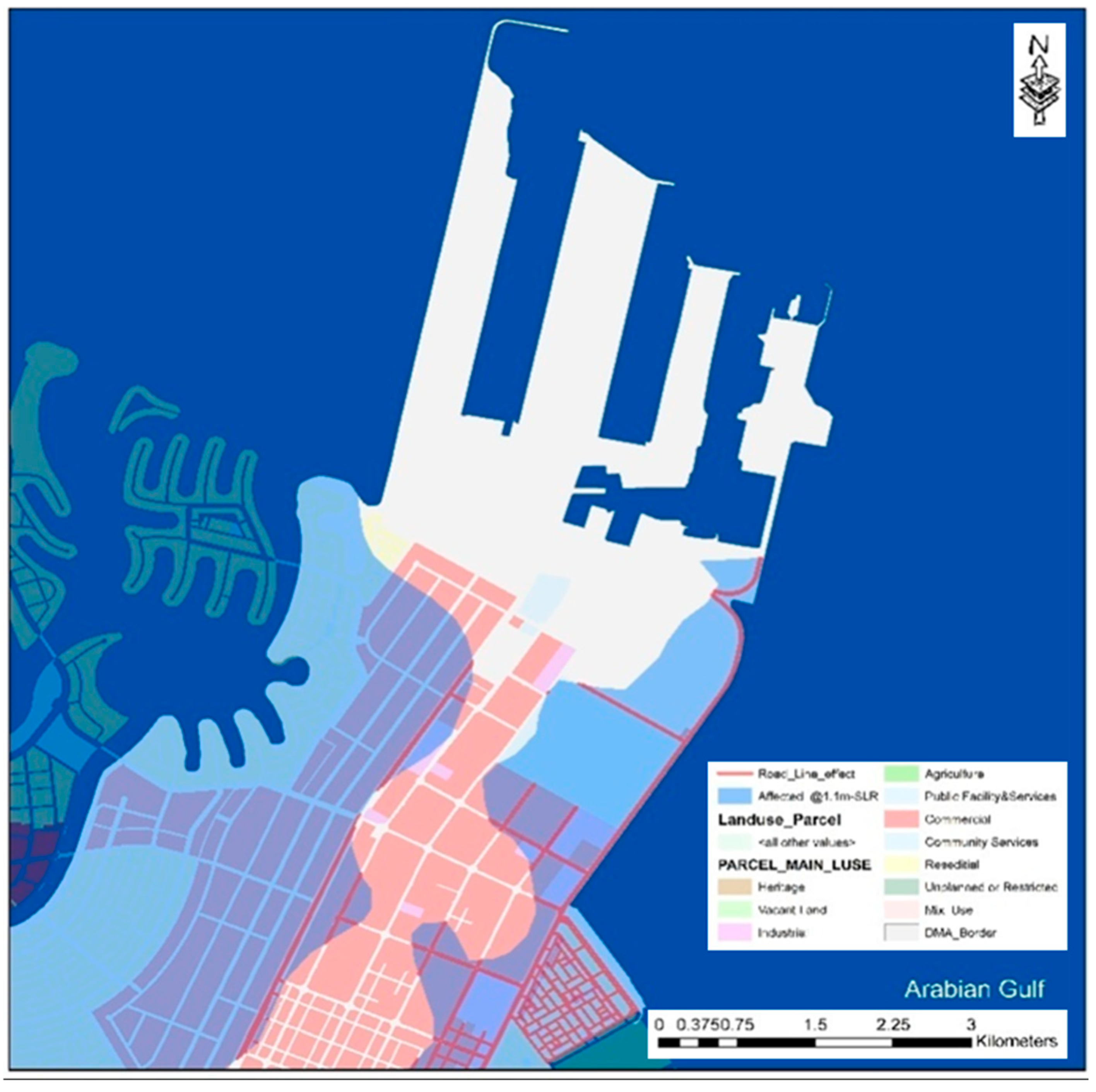

- Spatial analysis of susceptible zones: After delineating the inundated susceptible zones, the impact of the simulated SLR scenarios was assessed by overlaying the inundation layer on existing land uses. The assessment included residential and commercial land uses, road networks, public facilities, future development land uses, multiple usage land uses, and industrial land use, as shown in Figure 6. The affected zones were summarized using inferential and descriptive statistics and discussed.

3. Results and Discussion

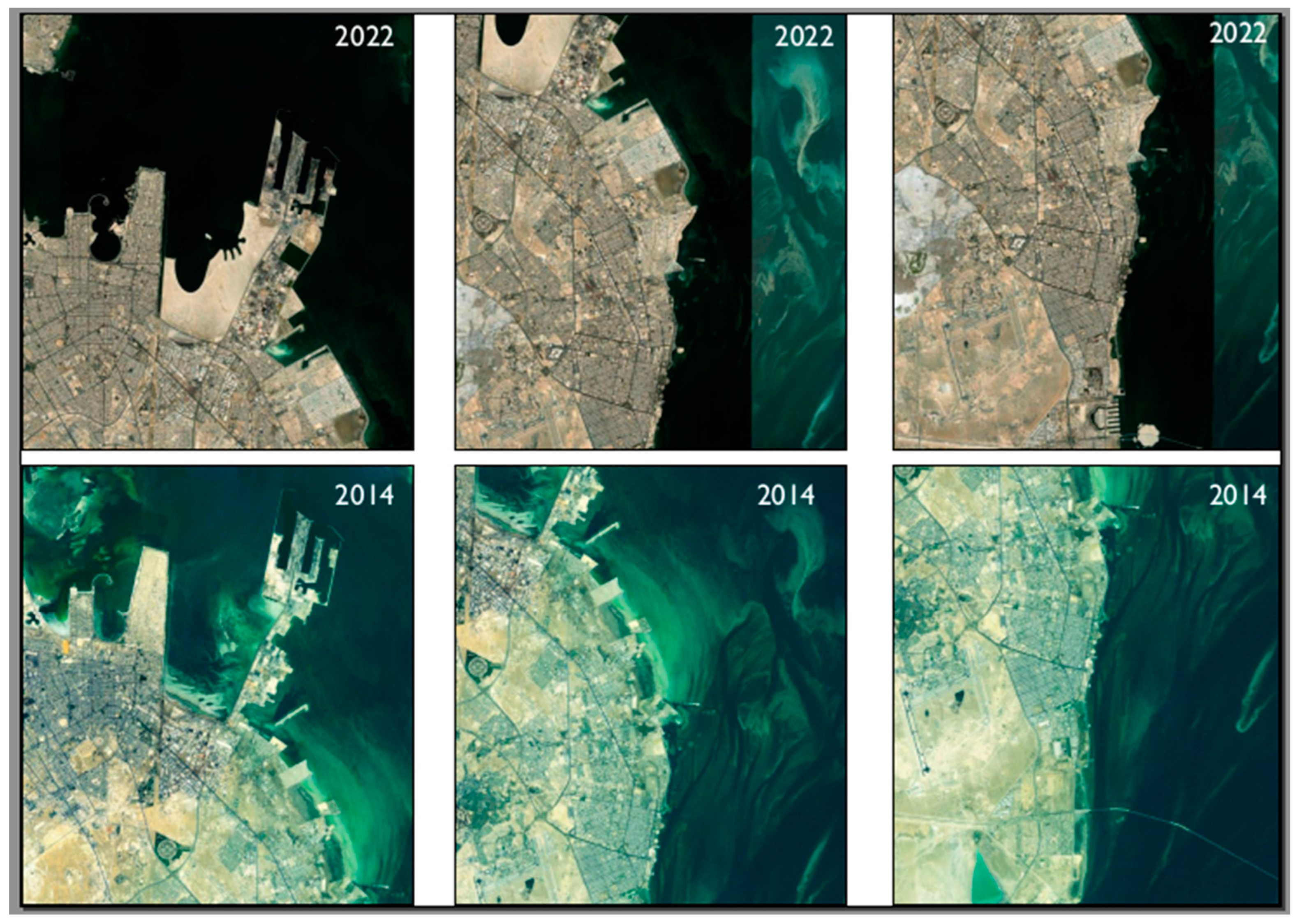

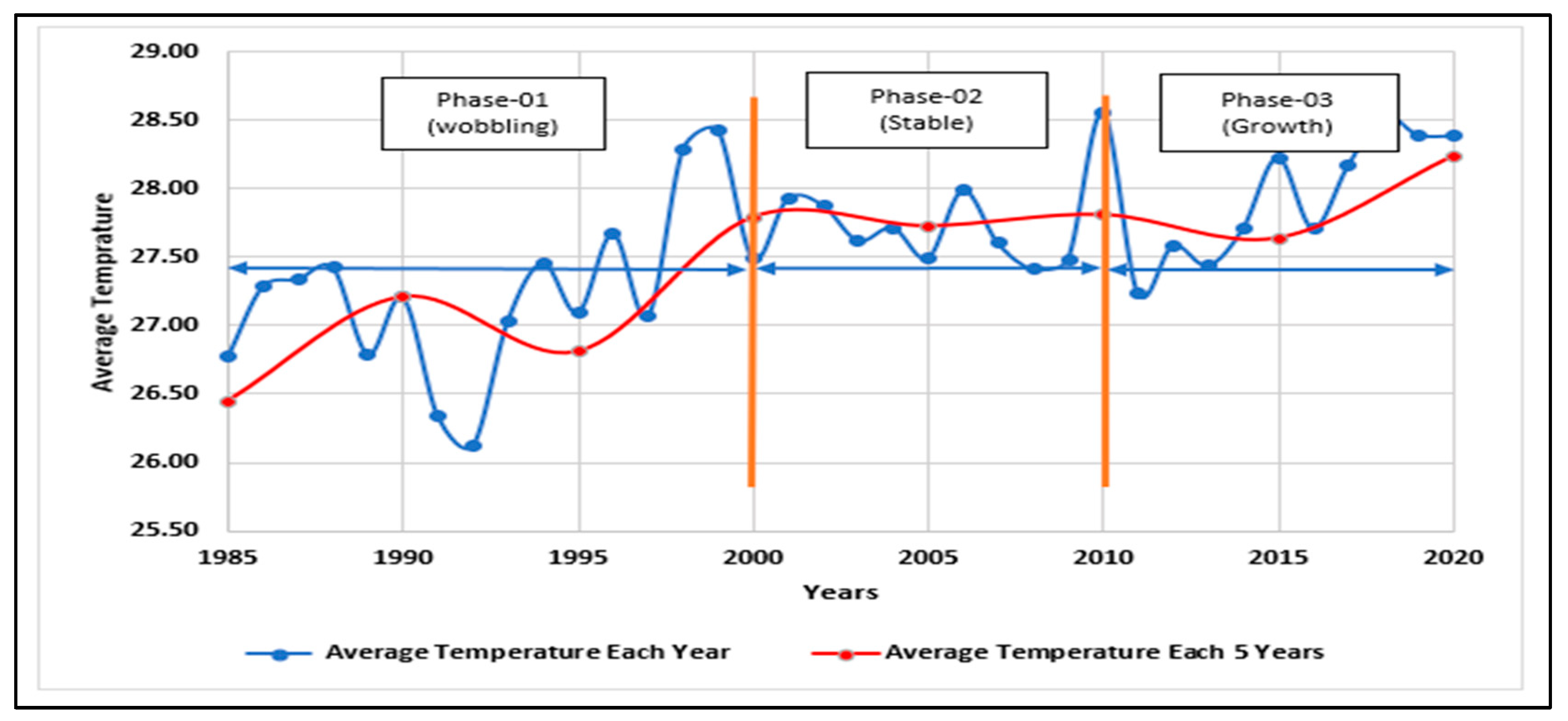

3.1. Effects of Land Reclamation in DMA

3.2. SLR Simulation

4. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Griggs, G.; Reguero, B.G. Coastal adaptation to climate change and sea-level rise. Water2021, 13(16), 2151.

- Nunez C. Sea level rise explained: Oceans are rising around the world, causing dangerous flooding. Why is this happening, and what can we do to stem the tide? National Geography.2019. Available online: https://www.nationalgeographic.com/environment/article/sea-level-rise-1 (access 17 August 2021).

- Nicholls, R.J.; Cazenave, A. Sea-level rise and its impact on coastal ones. Science2010, 328(5985), 1517-1520.

- Abubakar, I.R.; Dano, U.L. Sustainable urban planning strategies for mitigating climate change in Saudi Arabia. Envi., Dev. and Sust2020, 22, 5129–5152.

- Balogun, A.L.; Adebisi, N.; Abubakar, I.R.; Dano, U.L.; Tella, A. Digitalization for transformative urbanization, climate change adaptation, and sustainable farming in Africa: trend, opportunities, and challenges. J. of Integr.Envtal Sciences2022, 1-21. [CrossRef]

- Tella, A.; Balogun, A.L. Ensemble fuzzy MCDM for spatial assessment of flood susceptibility in Ibadan, Nigeria. Nat. Hazards2020, 104(3), 2277-2306.

- IPCC. Climate change 2014: synthesis report. Contribution of working groups I, II and III to the fifth assessment report of the intergovernmental panel on climate change.2014.

- De Almeida, B.A.; Mostafavi, A. Resilience of Infrastructure Systems to Sea-Level Rise in Coastal Areas: Impacts, Adaptation Measures, and Implementation Challenges. Sustainability2016, 8, 1115.

- Antonioli, F.; De Falco, G.; Lo Presti, V.; Moretti, L.; Scardino, G.; Anzidei, M.; Mastronuzzi, G. Relative sea-level rise and potential submersion risk for 2100 on 16 coastal plains of the Mediterranean Sea. Water2020, 12(8), 2173.

- Balogun, A.; Quan, S.; Pradhan, B.; Dano, U.; Yekeen, S. An improved flood susceptibility model for assessing the correlation of flood hazard and property prices using geospatial technology and fuzzy-ANP. J. of Envi. Informatics, 2020, . [CrossRef]

- Dano, U.L.; Balogun, A.L.; Matori, A.N.; Wan Yusouf, K.; Abubakar, I.R.; Mohamed, S.; et al. Flood susceptibility mapping using GIS-based analytic network process: A case study of Perlis, Malaysia. Water2019, 11(3), 615.

- Chitsaz, N.; Banihabib, M.E. Comparison of different multi criteria decision-making models in prioritizing flood management alternatives. Water Res. Mangt2015, 29(8), 2503-2525.

- Fernandez, D. S.; Lutz, M. A. Urban flood hazard zoning in Tucumán Province, Argentina, using GIS and multicriteria decision analysis. Engrg. Geology2010, 111(1-4), 90-98.

- Kjeldsen, T.R. Modelling the impact of urbanization on flood frequency relationships in the UK. Hydro. Research2010, 41(5), 391-405.

- Lawal, D.U.; Matori, A.N.; Yusof, K. W.; Hashim, A.M.; Aminu, M.; Sabri, S.; Mokhtar, M.R. M. Flood susceptibility modeling: A geo-spatial technology multi-criteria decision analysis approach. Res. J. of Appl. Sci., Energy and Tech.2014, 7(22), 4638–4644.

- Lawal, D.U.; Matori, A.N.; Yusuf, K.W.; Hashim, A.M.; Balogun, A.L. Analysis of the flood extent extraction model and the natural flood influencing factors: A GIS-based and remote sensing analysis. In IOP conference series: earth and environmental science, Kuching, Sarawak, Malaysia, (26-29 February 2014) (Vol. 18, No. 1, p. 012059). IOP Publishing.

- Lawal, D.U.; Matori, A.N.; Hashim, A.M.; Wan Yusof, K.; Chandio, I.A. Detecting flood susceptible areas using GIS-based analytic hierarchy process. In 2012 International Conference on Future Environment and Energy IPCBEE, Singapore, 2012 (Vol. 28, pp. 1–5) IACSIT Press.

- Matori, A. N.; Lawal, D. U. Flood disaster forecasting: A GIS-based group analytic hierarchy process approach. Applied Mechanics and Materials, 567, 717-723. 2014.

- Lawal, D.U.; Matori, A.N. Spatial analytic hierarchy process model for flood forecasting: An integrated approach. In IOP conference series: Earth and environmental science, 2014 (Vol. 20, no. 1, p. 012029). IOP Publishing.

- Wang, Y.; Li, Z.; Tang, Z.; Zeng, G. A GIS-based spatial multi-criteria approach for flood risk assessment in the Dongting Lake Region, Hunan, Central China. Water Res. Mangt2011, 25(13), 3465-3484.

- Dano, U.L. An AHP-based assessment of flood triggering factors to enhance resiliency in Dammam, Saudi Arabia. GeoJournal 2022, 87 (3), 1945–1960.

- Dawod, G.M.; Mirza, M.N.;Al-Ghamdi, K.A. GIS-based estimation of flood hazard impacts on road network in Makkah city, Saudi Arabia. Envi. Earth Sci2012, 67(8), 2205-2215.

- Dano, U.L. Flash flood impact assessment in Jeddah City: An analytic hierarchy process approach. Hydro 2020, 7(1), 10.

- Youssef, A.M.; Sefry, S.A.; Pradhan, B.; Alfadail, E.A. Analysis on causes of flash flood in Jeddah city (Kingdom of Saudi Arabia) of 2009 and 2011 using multi-sensor remote sensing data and GIS. Geom., Nat. Haz. and Risk2016, 7(3), 1018-1042.

- Ledraa, T.A.; Al-Ghamdi, A.M. Planning and Management Issues and Challenges of Flash Flooding Disasters in Saudi Arabia: The Case of Riyadh City. J. Archit. Plan 2020, 32, 155-171.

- Radwan, F.; Alazba, A.A.; Mossad, A. Flood risk assessment and mapping using AHP in arid and semiarid regions. Acta Geophy 2019, 67(1), 215-229.

- Martínez, M.L.; Intralawan, A.; Vázquez, G.; Pérez-Maqueo, O.; Sutton, P.; Landgrave, R. The coasts of our world: Ecological, economic and social importance. Ecol. Econ2007, 63, 254–272.

- Barbier, E.B.; Hacker, S.D.; Kennedy, C.; Koch, E.W.; Stier, A.C.; Silliman, B.R. The value of estuarine and coastal ecosystem services. Ecol. Monogr2011, 81, 169–193.

- Sasmito, S.D.; Murdiyarso, D.; Friess, D.A.; Kurnianto, S. Can mangroves keep pace with contemporary sea level rise? A global data review. Wetl. Ecol. Manag2015, 24, 263–278.

- Beck, M.W.; Losada, I.J.; Menéndez, P.; Reguero, B.G.; Díaz-Simal, P.; Fernández, F. The global flood protection savings provided by coral reefs. Nat. Commun2018, 9.

- Menéndez, P.; Losada, I.J.; Torres-Ortega, S.; Narayan, S.; Beck, M.W. The Global Flood Protection Benefits of Mangroves. Sci. Rep2020, 10, 4404.

- Zu Ermgassen, P.S.E.; Mukherjee, N.; Worthington, T.A.; Acosta, A.; Rocha Araujo, A.R.D.; Beitl, C.M.; Castellanos-Galindo, G.A.; Cunha-Lignon, M.; Dahdouh-Guebas, F.; Diele, K.; et al. Fishers who rely on mangroves: Modelling and mapping the global intensity of mangrove-associated fisheries. Estuar. Coast. Shelf Sci2020, 248, 107159.

- Duarte, C.M.; Agusti, S.; Barbier, E.; Britten, G.L.; Castilla, J.C.; Gattuso, J.-P.; Fulweiler, R.W.; Hughes, T.P.; Knowlton, N.; Lovelock, C.E.; et al. Rebuilding marine life. Nature2020, 580, 39–51.

- Reguero, B.G.; Storlazzi, C.D.; Gibbs, A.E.; Shope, J.B.; Cole, A.D.; Cumming, K.A.; Beck, M.W. The value of US coral reefs for flood risk reduction. Nat. Sustain2021, 1–11.

- Karbassi, A. R., Maghrebi, M., Lak, R., Noori, R., &Sadrinasab, M. Application of sediment cores in reconstruction of long-term temperature and metal contents at the northern region of the Persian Gulf. Desert 2019, 24(1), 109-118.

- Eckstein, V.;Kunzel, L.; Schafer. The Global Climate Risk Index 2018. 2018. Available online: htt ps://www.germanwatch.org/en/node/14987 (accessed 23 April 2020).

- Al-Maamary, H. M.; Kazem, H.A.; Chaichan, M.T. Climate change: the game changer in the Gulf Cooperation Council region. Renew. and Sust. Energy Rev 2017, 76, 555-576.

- Hereher, M. E. Assessment of climate change impacts on sea surface temperatures and sea level rise—The Arabian Gulf. Climate 2020, 8(4), 50.

- Abdrabo, M. A.; Hassaan, M. A. Assessment of Policy-Research Interaction on Climate Change Adaptation Action: Inundation by Sea Level Rise in the Nile Delta. J. of Geosci. and Envi. Protection2020, 8(10), 314.

- El-Nahry, A. H.;Doluschitz, R. Climate change and its impacts on the coastal zone of the Nile Delta, Egypt. Envtal Earth Sci2010, 59(7), 1497-1506.

- Natesan, U.; Parthasarathy, A. The potential impacts of sea level rise along the coastal zone of Kanyakumari District in Tamilnadu, India. J. of Coastal Conserv2010, 14(3), 207-214.

- Alhowaish, A. K. Eighty years of urban growth and socioeconomic trends in Dammam Metropolitan Area, Saudi Arabia. Habitat International2015, 50, 90-98.

- Abou-Korin, A. A.; Al-Shihri, F. S. (). Rapid urbanization and sustainability in Saudi Arabia: the case of Dammam metropolitan area. J. of Sustain. Devt2015, 8(9), 52.

- Local Weather. Dammam Climate History.n.d. Available online: http://www.myweather2.com/City-Town/Saudi-Arabia/Dammam/climate-profile.aspx (accessed 5 January 2020).

- Atif, R.M.; Almazroui, M.; Saeed, S.; Abid, M.A., Islam, M.N.; Ismail, M. Extreme precipitation events over Saudi Arabia during the wet season and their associated teleconnections. Atmosph. Research2020, 231, 104655.

- Maghrebi, M., Karbassi, A., Lak, R., Noori, R., &Sadrinasab, M. Temporal metal concentration in coastal sediment at the north region of Persian Gulf. Marine pollution bulletin2018, 135, 880-888.

- UN-Habitat.Dammam CPI Profile 2016.Saudi Future Cities Programme, 2016.Available online: htt ps://www.futuresaudicities.org/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Damman.pdf (accessed 16 August 2022).

- Yin, R.K. Qualitative Research From Start to Finish. Guilford Press, New York.2010.

- Google Map, 2022, https://www.google.com/maps/@26.3764116,50.1804495,30977m/data=!3m1!1e3 (accessed on October 26, 2022).

- Malik, A.; Abdalla, R. Geospatial modeling of the impact of sea level rise on coastal communities: application of Richmond, British Columbia, Canada. Modeling Earth Syst. and Envi2016, 2(3), 1-17.

- AlQahtany, A.M.; Dano, U.L.; Elhadi Abdalla, E.M.; Mohammed, W.E.; Abubakar, I.R.; Al-Gehlani, W.A.G.; Alshammari, M. S. Land Reclamation in a Coastal Metropolis of Saudi Arabia: Environmental Sustainability Implications. Water2022, 14(16), 2546.

- Chinowsky, P.S.; Price, J.C.; Neumann, J.E. Assessment of climate change adaptation costs for the US road network. Glob. Environ. Chang2013, 23, 764–773.

- Titus, J.G.; Anderson, K. E. Coastal sensitivity to sea-level rise: A focus on the Mid-Atlantic region (Vol. 4). Climate Change Science Program. 2009.

- Heberger, M. The Impacts of Sea Level Rise on the San Francisco Bay; California Energy Commission: Sacramento,CA, USA, 2012.

- Lee, Y. Coastal planning strategies for adaptation to sea level rise: A case study of Mokpo, Korea. J. of Building Constr. and Planning Res2014,1, 74-81.

- Azevedo de Almeida, B.;Mostafavi, A. Resilience of infrastructure systems to sea-level rise in coastal areas: Impacts, adaptation measures, and implementation challenges. Sustainability2016, 8(11), 1115.

- Byravan, S.; Rajan, S.C. Sea level rise and climate change exiles: A possible solution. Bull. At. Sci2015, 71, 21–28.

- Xu, L.; Ding, S.; Nitivattananon, V.;Tang, J. Long-Term Dynamic of Land Reclamation and Its Impact on Coastal Flooding: A Case Study in Xiamen, China. Land2021, 10(8), 866.

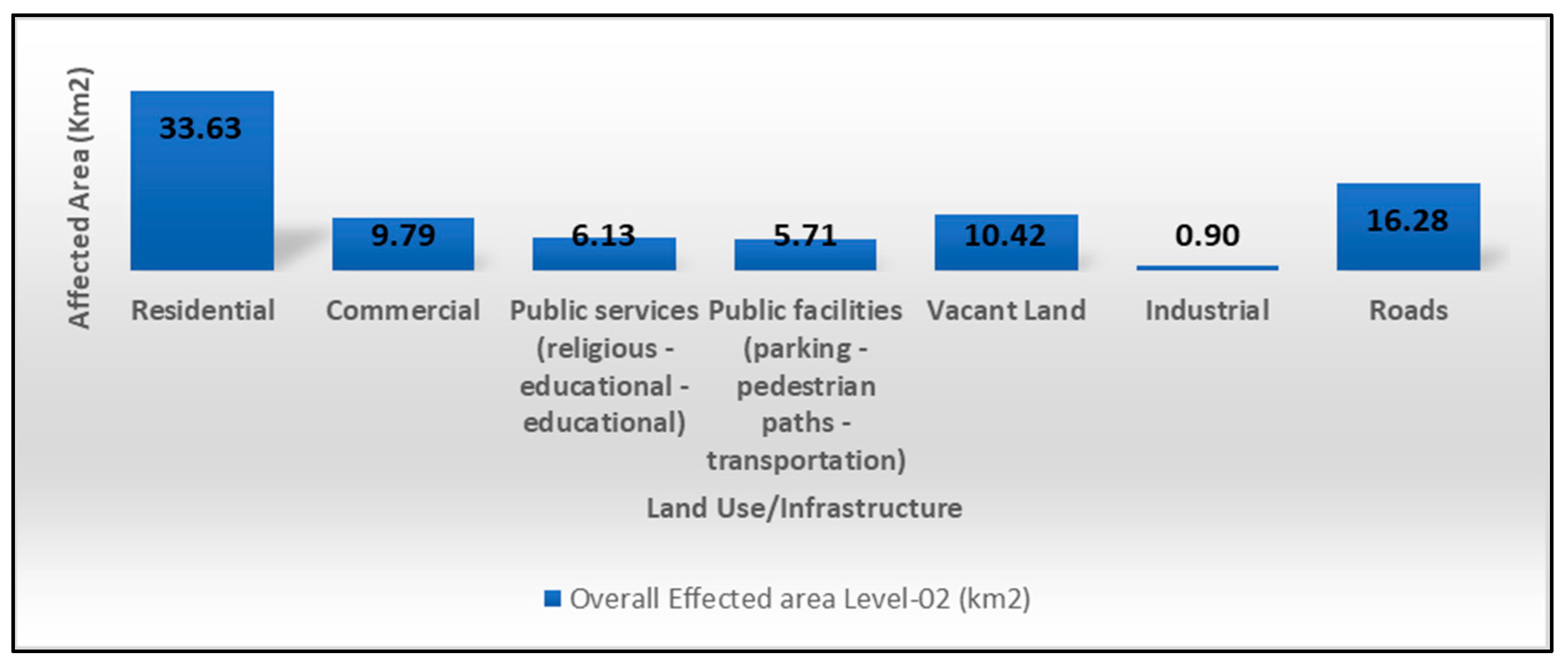

| Land Use/Infrastructure | Khobar | Dhahran | Dammam East | Dammam Central | ||||

| Total area | Affected area | Total area | Affected area | Total area | Affected area | Total area | Affected area | |

| Residential (km2) | 72.39 | 18.71 (25.85%) | 25.86 | 4.23 (16.35%) | 36.47 | 9.65 (26.47%) | 10.46 | 1.04 (9.91%) |

| Commercial (km2) | 17.45 | 1.63 (9.32%) | 8.59 | 0.13 (1.55%) | 22.86 | 7.67 (33.56%) | 6.53 | 0.36 (5.51%) |

| Public Facility and services: religious, educational, health, parking, ports (km2) | 23.42 | 6.23 (26.60%) | 10.72 | 0.74 (6.90%) | 23.80 | 4.18 (17.56%) | 5.87 | 0.69 (11.75%) |

| Vacant Land (km2) | 17.26 | 5.47 (31.72%) | 14.54 | 0.46 (3.14%) | 6.88 | 4.44 (64.58%) | 0.76 | 0.05 (6.04%) |

| Mied use: Residential and Commercial land (km2) | 1.48 | 0.00 (0.00%) | 9.42 | 0.00 (0.00%) | 0.00 | 0.00 (0.00%) | 0.00 | 0.00 (0.00%) |

| Industrial Area (km2) | 0.02 | 0.00 (0.00%) | 0.03 | 0.00 (0.00%) | 5.94 | 0.90 (0.00%) | 1.79 | 0.00 (0.00%) |

| Roads (km) | 49.20 | 10.20 (20.74%) | 21.31 | 1.78 (8.37%) | 25.84 | 3.39 (13.13%) | 11.62 | 0.90 (7.75%) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).