1. Introduction

This paper explores the challenges of kinematic synthesis for four-link initial kinematic chains, which are fundamental in the design of planar (flat) lever mechanisms. Such synthesis is especially important in developing high-class mechanisms [

1,

2,

3], where specific motion laws are imposed on both input and output links [

4]. The core of the synthesis problem lies in defining a plane-parallel motion of two rigid bodies (or their planar cross-sections) with respect to a third, fixed body [

5,

6]. The approach is grounded in the theory of approximate kinematic geometry, which allows for practical realization of mechanisms based on discrete positional data. The synthesis of four-link initial kinematic chains with rotational pairs is a fundamental problem in the design of planar lever mechanisms, especially high-class mechanisms with prescribed laws of motion for input and output links. This problem arises frequently in the design of machinery where precise coordination of moving components is required, such as robotic manipulators, mechanical linkages [

7,

8], and automated systems. The challenge lies in finding appropriate geometric configurations that satisfy desired motion criteria while ensuring kinematic compatibility and smooth operation [

9,

10]. Traditional methods for mechanism synthesis often rely on graphical or analytical approaches, which can be cumbersome and limited in their application. As mechanisms become more complex, particularly those involving rotational and translational pairs [

11], the design process requires more robust mathematical tools. Recent advancements in computational techniques have enabled the development of more efficient and accurate methods for solving synthesis problems [

12,

13,

14], particularly when formulating them as optimization problems. In this work, we focus on the synthesis of four-link initial kinematic chains formed by connecting three moving planes:

(fixed plane),

(rotating plane), and

(plane-parallel moving plane). The objective is to determine the optimal positions of points

,

, and

such that the distance between

B and

C remains approximately constant across various configurations. This problem formulation is particularly important when designing open kinematic chains of the form

ABCD with three degrees of freedom, which serve as the foundation for more complex mechanisms [

1]. The design and synthesis of planar mechanisms with specified motion characteristics is a fundamental problem in mechanical engineering and robotics. In particular, the synthesis of four-link kinematic chains plays a crucial role in developing precise and efficient linkage systems used in a wide range of industrial and technological applications, such as manipulators, tracing devices, and automation equipment. One of the central tasks in kinematic synthesis is to determine the optimal geometric configuration of links and joints that can reproduce a prescribed set of positions and orientations of moving bodies. This paper focuses on the synthesis of initial four-link kinematic chains with rotational pairs [

15,

16,

17], which are formed by connecting two moving planes through hinges to a fixed base, creating an open-loop mechanism with three degrees of freedom [

18]. Traditional methods of mechanism synthesis often involve solving highly nonlinear systems of algebraic equations derived from loop-closure conditions or geometric constraints. These methods, while exact in theory, become computationally intensive and unwieldy when applied to systems with multiple positional constraints. Moreover, the multiplicity of solutions (including local maxima, saddle points, and non-physical configurations) requires careful selection and verification of valid designs. To address these challenges, we propose an efficient and theoretically grounded approach based on approximate kinematic geometry [

1,

20]. The method relies on minimizing a weighted sum-of-squares error function that quantifies the deviation of the actual mechanism from the desired motion behavior. By expressing the geometric relationships in matrix form and breaking down the full system into a sequence of simpler linear subsystems, the synthesis problem becomes tractable and can be solved iteratively. A key result of this work is a theorem that guarantees the monotonic decrease of the objective function across successive iterations, ensuring convergence to a local minimum. This allows for practical implementation of the algorithm without resorting to the full solution of high-degree polynomial systems [

21]. Furthermore, the algorithm’s flexibility permits it to be applied to a broad class of mechanisms, as long as no strict parameter constraints are imposed. The remainder of the paper details the mathematical formulation of the problem, derivation of the objective function, linearization strategy, the minimization theorem, and the iterative synthesis algorithm. Visualization of the iterative process is also presented to demonstrate convergence behavior and support practical implementation. The problems of mechanism synthesis have mainly developed in two directions: algebraic methods of approximation synthesis of lever mechanisms and methods of synthesis of lever mechanisms based on approximation kinematic geometry [

22,

23]. The development of these two directions of mechanism synthesis has had a decisive influence on the formation of methods of approximation synthesis of lever mechanisms [

24]. Kinematic synthesis is one of the most important stages in the process of designing a mechanism, since it is at this stage that the basic kinematic properties necessary for the mechanism to perform its assigned functions are formed. The advantages of optimization methods for mechanism synthesis are especially evident in cases where "classical" methods of kinematic synthesis based on kinematic geometry or various approximation methods are inapplicable or ineffective. The success of searching for an optimal mechanism largely depends on the choice of the initial approximation determined by classical methods [

11], while a mechanism designed by classical methods often requires optimization taking into account additional synthesis conditions. Based on the above, it can be concluded that the development of methods for synthesizing flat lever mechanisms was aimed at creating a theory of synthesis that would make it possible to synthesize any mechanism schemes based on a single principle. In particular, many studies at the heart of solving problems of structural and kinematic synthesis of mechanisms are essentially the idea of forming a mechanism from certain initial kinematic chains, as from component parts. The purpose of this work is to develop a unified set of numerical and analytical methods for the structural and kinematic synthesis of planar lever mechanisms, based on the prescribed laws of motion of the input and output links. The methods are designed to be applicable across all stages of the synthesis process and are grounded in the systematic use of initial kinematic chains (IKC) and their structural modifications [

25]. This approach enables the automated generation of mechanism topologies and dimensional parameters that satisfy both geometric and functional motion constraints, thereby facilitating the efficient and accurate design of high-class planar mechanisms through a computationally supported framework. Reliability of theoretical results is ensured by correct use of theoretical provisions and methods of theoretical and applied mechanics and applied mathematics. The efficiency of the method and algorithms is confirmed by the results of numerical modeling on a computer. Numerical results of the synthesis of specific mechanisms confirm the operability and efficiency of the developed method of structural and kinematic synthesis of flat lever mechanisms according to the specified laws of motion of the input and output links of the mechanism.

2. Materials and Methods

Let there be given

N discrete positions of two planes, denoted as

Q1 and

Q2, which represent sections of two rigid bodies. Their positions relative to a fixed reference plane

Q are specified as follows: plane

Q1 is defined by coordinates (

XA, YA) and a rotation angle

about point

A, where

; plane

Q2 is defined by coordinates (

) and a rotation angle

about point

D, for the same

:

To formalized the motions: A rectangular coordinate system OXY is rigidly attached to the fixed plane

Q. The moving planes

Q1 and

Q2 each carry their own coordinate systems:

, fixed in

Q1;

, fixed in

Q2 for each position

. In this setup: plane

Q1 undergoes pure rotational motion about the fixed-point

A; plane

Q2 executes a general plane-parallel motion [

1], governed by the trajectory of point

D and rotation

. The aim is to synthesize a kinematic chain-typically a four-bar linkage-capable of guiding these two bodies through the given set of positions with high precision, ideally minimizing deviations using methods of approximate synthesis. Where

XA, YA - is the fixed-point

A on the base plane

Q;

- is the coordinates of hinge

B on

Q1;

- is the coordinates of hinge

C on

Q2;

- is the path (trajectory) of point

D on

Q2;

- is the rotation angle of

Q1 in position

;

- is the rotation angle of

Q2 in position

;

a,

c - is the coefficients of straight line equation (e.g. for translational guidance);

R - length of connecting link. Research manuscripts reporting large datasets that are deposited in a publicly available database should specify where the data have been deposited and provide the relevant accession numbers. If the accession numbers have not yet been obtained at the time of submission, please state that they will be provided during review. They must be provided prior to publication. To achieve coordinated motion of the two moving planes

Q1 and

Q2, geometric connections must be established between them. These connections can be implemented in two principal ways, leading to different types of four-link kinematic chains: 1. Kinematic chain with a two-hinged link. In this case, a rigid link with rotational (revolute) pairs is used to directly connect the two moving planes: The resulting mechanism is a closed four-link kinematic chain

ABCD, consisting entirely of rotational joints and having three degrees of freedom [

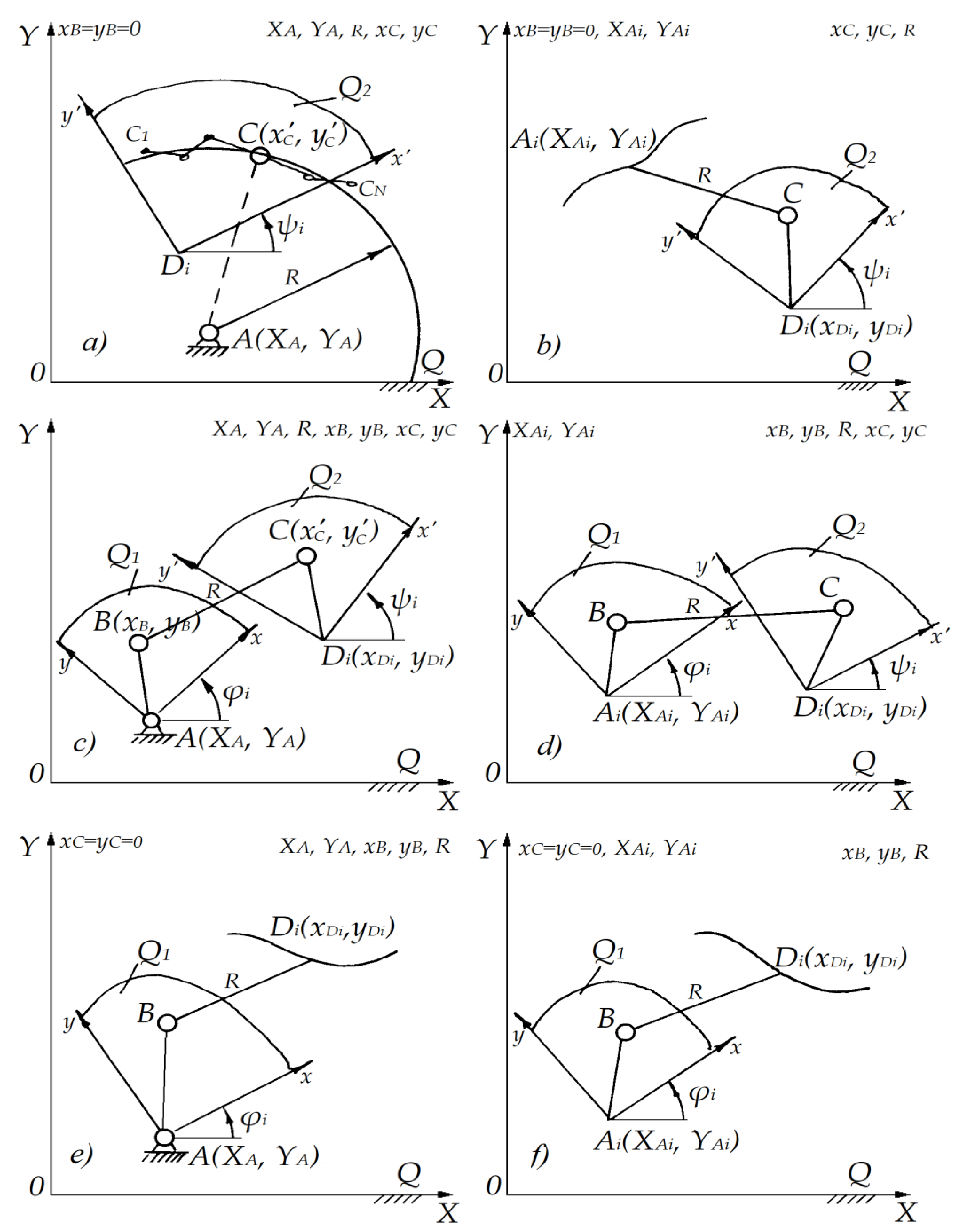

11]; The configuration is illustrated schematically in

Figure 1c; The task is to determine the positions of three key points:

- a fixed hinge on the stationary plane;

- a hinge point on the first moving plane;

a hinge point on the second moving plane. These points must be chosen such that the mechanism ensures the specified laws of motion (i.e., prescribed positions and orientations of

Q1 and

Q2) across all

N configurations. 2. Kinematic chains with a link group (open chains). Alternatively, coordination can be achieved using a link group that combines rotational and translational pairs: The guide link is attached to one of the moving planes, and the stone link (slider or connecting link) is pivotally attached to the other. This configuration yields two open variants of the four-link chain: Variant

ACD: rotational pair at

A, translational pair along line

CD; Variant

ABD: rotational pair at

A, translational pair along line

BD. Both variants retain three degrees of freedom [

2], but they differ in how motion is transferred between

Q1 and

Q2. In this approach, synthesis requires: Determining the coefficients (slope and intercept) of the guiding line equation, along which translational motion occurs. Specifying the position of the hinge:

in the

ABD configuration;

in the

ACD configuration. Identifying the fixed hinge point

on the stationary plane. This

Figure 2 presents the geometric configurations of initial four-link kinematic chains with rotational pairs formed by connecting two moving planes

Q1 and

Q2 through a fixed base plane

. The subfigures illustrate the different problem formulations and corresponding parameter groupings used in the synthesis algorithm: Full configuration of the four-bar chain ABCD, showing the fixed base point

, and moving points

,

, and the constant inter-hinge distance

R. Intermediate configurations for each minimization step: Solving for

A while

B and

C are fixed; Solving for

B while

A and

C are fixed; Solving for

C while

A and

B are fixed. Reduced configurations corresponding to boundary cases (e.g., fixing one point or setting coordinates to zero) for simplifying the linear systems [

3,

4]. Each subfigure corresponds to a stage in the stepwise synthesis algorithm, supporting convergence to a locally optimal mechanism by solving linearized subsystems (as described in systems Eq. (17), Eq. (21), and Eq. (24)).

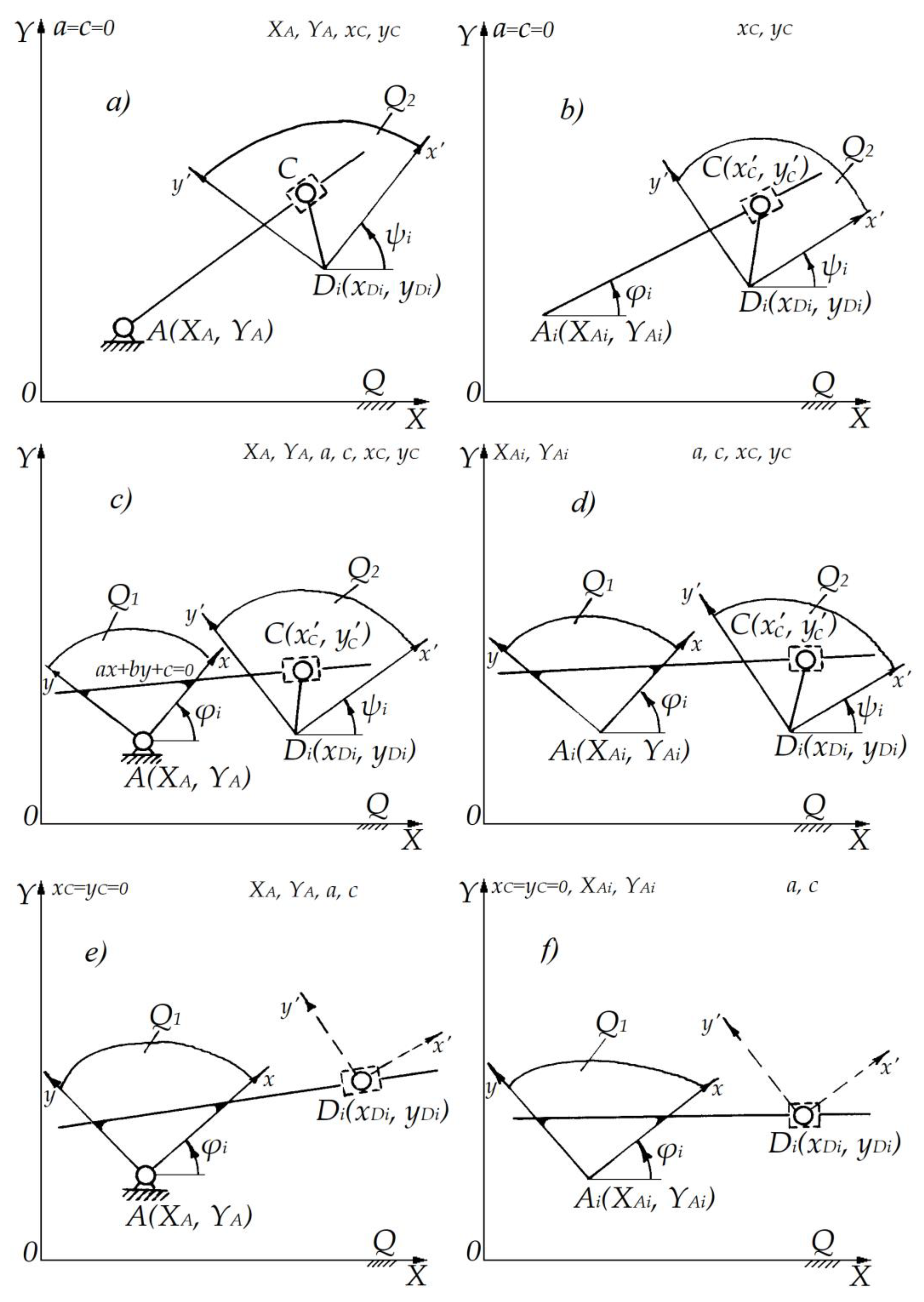

This

Figure 2 presents geometric configurations for synthesizing kinematic chains of type

ACD and

AD, where the connection between the moving planes

Q1 and

Q2 is implemented using one rotational and one translational pair. The aim is to constrain the motion of one point (typically on

) to follow an approximately linear path relative to another plane. Initial configurations with known base point

and a point

moving along a path defined implicitly by the guiding line. Simplified geometric construction of the motion constraint imposed on point

. Line equation

is imposed on point

trajectory relative to plane

Q1. Plane-parallel motion and angular orientation of plane

shown relative to base

.

Reduced cases where specific coordinates are zeroed

for simplification in solving the associated linear systems. These configurations correspond to problem formulations using expressions for

, and systems Eq. (24) and Eq. (23), leading to identification of optimal line parameters

a,

c, and base point coordinates. This

Figure 2 supports the second synthesis problem discussed in the paper, where the objective is to determine optimal hinge placement and line constraints to guide motion coordination through translational pair synthesis.

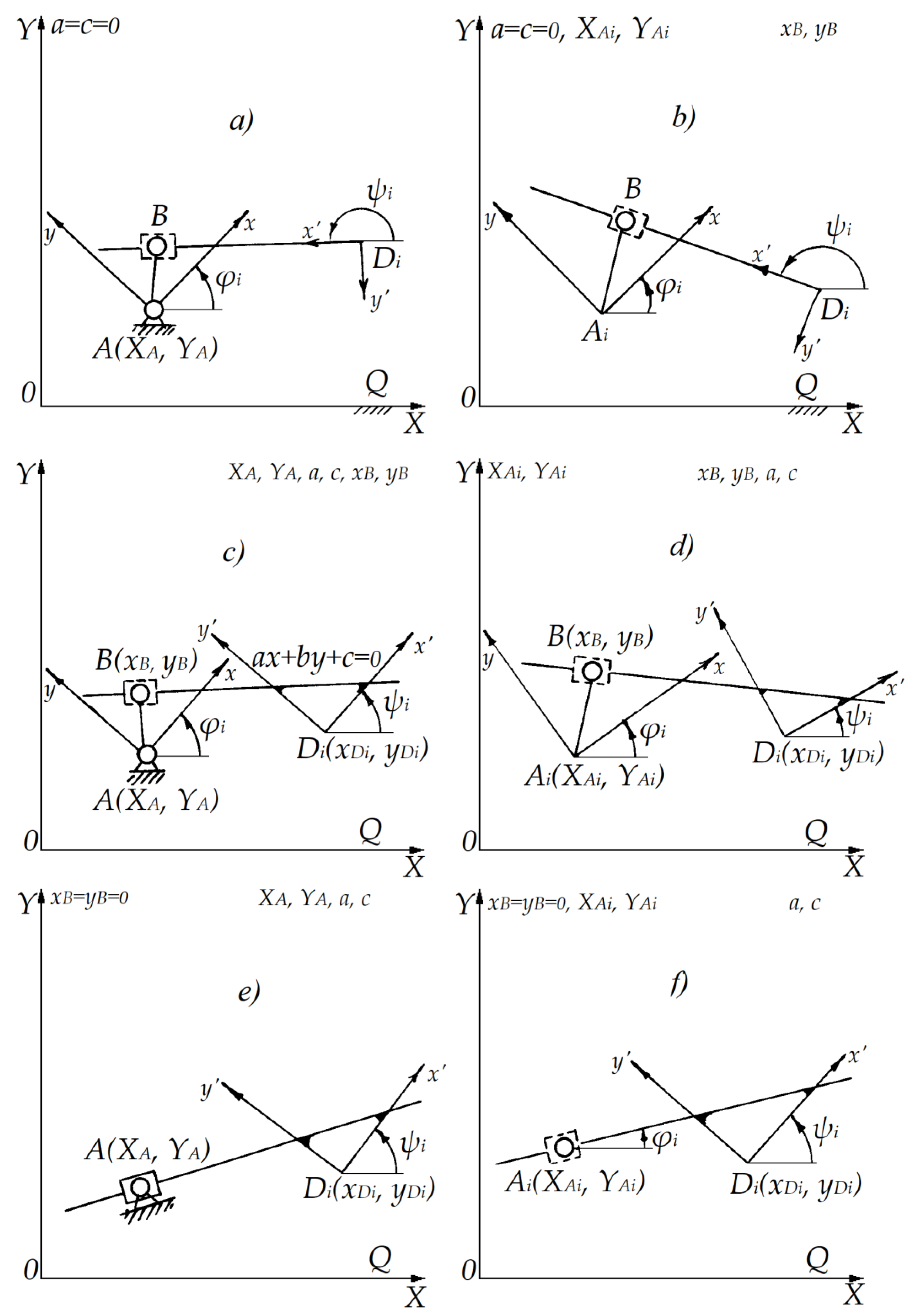

This

Figure 3 depicts the geometric arrangements for the synthesis of

ABD and

AD kinematic chains, where the moving planes

Q1 and

Q2 are connected through one fixed base plane

using a combination of rotational and translational pairs. In this formulation, the trajectory of point

is constrained relative to plane

Q2 via an approximate straight-line path [

5,

6,

7,

8], while point

serves as the rotation base. Initial geometric setup where the straight-line guiding point

is implicitly defined through transformations relative to

Q2. Local coordinate system and motion vector orientation of point

.

Explicit formulation of the constraint line

, through which point

trajectory is minimized. Graphical construction of synthesis problem to determine the optimal hinge coordinates and line parameters on

Q1 and

Q2. Reduced boundary cases for solving simplified systems by setting

, enabling direct solution of line parameters

a,

c for motion planning in the translational domain. These configurations support the third synthesis problem of the study [

9,

10,

11], where the objective is to determine optimal placement of the base point

, line coefficients

a,

c, and hinge location

such that the movement is constrained according to translational behavior. The

Figure 3c corresponds to solving systems such as Eq. (24) and Eq. (23) with appropriate linearization.

3. Synthesis of Initial Kinematic Chain with Rotation Pairs (ABCD Chain)

To determine the linear dimensions of the closed four-link initial kinematic chain

ABCD is shown in

Figure 1c, we formulate the synthesis task as a geometric optimization problem. The aim is to ensure that the distance between two moving points - one on each of the mobile planes

and

- remains approximately constant across multiple specified positions [

5,

12].

Problem 1. Synthesis of ABCD initial kinematic chain with rotation pairs.

– on the stationary base plane;

- fixed in the local coordinate system of the first moving plane;

- fixed in the local coordinate system of the second moving plane.

Such that the distance between and remains close to a constant for all given finite relative positions of the planes and .

For each position , we are given:

plane : defined by rotation angle around point ;

plane : defined by rotation angle and displacement , of point .

The coordinates of points and at each position , relative to the global system , are obtained using homogeneous transformation matrices.

Point

in

(rotation about

):

Point

in

(undergoing planar motion):

For each position

, the constraint is:

The deviation from this constraint across all

positions is minimized using an objective function, typically the sum of squared deviations:

Unknown parameters to determine (7 total):

– are the coordinates of the base point ;

– are the coordinates of the hinge point in its local frame;

– are the coordinates of the hinge point in its local frame;

– is the approximate link length between points and ;

Problem 2. Synthesis of ACD initial kinematic chain with rotational and translational pairs.

This problem concerns the synthesis of an open initial kinematic chain [

13,

14] of the form

ACD is shown in

Figure 2c, in which one link endpoint is constrained to move along a straight line (a prismatic pair), and the other endpoint is pivotally connected to the second moving body.

A base hinge point ;

A straight line - fixed in the coordinate system of plane ;

A point – defined in the local frame of .

Such that the trajectory of point (from plane ) approaches the desired straight line (defined in ) as closely as possible across N given motion positions.

This task defines the synthesis of an open initial kinematic chain ACD with mixed kinematic pairs:

A is a rotational pair between the fixed base and plane ;

is a point constrained to slide along a line (i.e., a prismatic pair) defined in the frame of .

This is appropriate for mechanisms such as guide-link couplers or line-follower linkages, where one endpoint traces a line and the opposite pivot is free to rotate.

For each position

, point

(in its local coordinates

,

) is transformed into the global frame using a homogeneous transformation:

We define the desired guide line on plane

in its local coordinates by

. To express this line in the global frame

, we apply the inverse transformation of plane

motion for each position

. The condition that transformed point

lies approximately on the transformed line yields:

This expression represents the signed distance from point

to the moving guide line (transformed to the global system), and we seek to minimize the sum of squared deviations from this line across all positions:

Unknown parameters (7 total):

– is the position of hinge on base plane ;

– are the coefficients of the line equation (defined in frame);

– are the local coordinates of point on plane .

Problem 3. Synthesis of ABD initial kinematic chain with translational pairs.

This problem addresses the design of an open initial kinematic chain

ABD is shown in

Figure 3c, in which the motion of a point

is constrained to approximate a straight-line trajectory defined in the local coordinate system of the second moving plane

.

A fixed hinge point ;

A moving point - defined in the local coordinate frame of ;

A line

defined in the coordinates system of plane

.

Such that the trajectory of point , when transformed through motion relative to the global base and observed from , remains as close as possible to this specified straight line during the entire motion cycle.

This is the synthesis of an ABD-type open initial kinematic chain with mixed kinematic pairs:

The point acts as a revolute joint to the input plane ;

The point is constrained to follow a line on plane , corresponding to a prismatic pair.

Such configurations are frequently found in planar guiding mechanisms [

15], single-stroke cams, and reciprocating systems where a point from the input side slides along a path defined by the output body.

The position of point

, given in local coordinates

,

, transforms to the global

frame as:

The straight line in

, defined by

in local coordinates, transforms into the global frame for each position

of

, using:

This expression computes the signed distance from point global position to the line defined on at position .

To ensure closeness of point

to the desired trajectory across all

N positions, we minimize the squared sum of line deviations:

Unknowns (7 total):

– are the location of the fixed base pivot ;

– are the position of the moving point ;

– are the coefficients defining the straight-line constraint in .

This synthesis problem ensures that the motion of a point

, when projected onto plane

, approximates a known line [

6,

16]. Together with Problem 2, it completes the strategy for designing initial kinematic chains that involve one translational constraint. Both Problem 2 (ACD) and Problem 3 (ABD) fall under the broader class of synthesis problems with translational pairs, where the guiding geometry is defined in a moving frame and the mechanism must conform to hybrid (rotational and prismatic) link constraints.

4. Weighted Difference for Synthesis with Rotational Pairs

4.1. First Form of the Weighted Difference (Optimizing over )

We want the length between the moving points

and

to be approximately constant:

This expression is a function of the seven unknown parameters: , , , . To calculate , we first need to compute and the positions of points and in the global coordinate system.

We define:

where

,

is the composite transformed difference vector from

to

, expressed as:

This gives the relative vector - mapped into global coordinates, allowing you to separate the search for optimal while treating the rest as known or intermediate.

We breaking the total error into different function forms (likely for simplification in optimization):

Form 1:

Form 2:

Form 3:

Each form treats a different group of parameters as variables while holding the rest fixed or transformed into intermediate quantities. This can help in iterative numerical solutions, where we minimize over subsets of parameters alternately.

You define the sum of squared weighted deviations for

given positions:

where

,

are functions of known data and the transformation matrices;

,

,

are unknowns to be found.

To minimize

, take partial derivatives with respect to each unknown and set them to zero:

From your derivation, using the chain rule and applying the structure of

, we arrive at:

To avoid the meaningless solution

, assume

. Then:

This simplifies the previous system. Substituting this result back in, the system becomes:

These are your final minimization conditions.

Step-by-step substitution from Eq. (9) into system Eq. (15):

We perform a powerful transformation that simplifies the nonlinear system into a linear system of equations by introducing a new variable:

This substitution transforms the previously nonlinear problem into a linear least-squares formulation, enabling direct matrix solution [

17]. Let’s now clearly walk through we transformation and express everything in compact, structured matrix form.

Let’s write the system you obtained in matrix form:

where

This system is linear and can be solved using any standard method (Gaussian elimination, LU decomposition, or matrix inversion), provided

, which guarantees that the Jacobian of the transformation is non-zero:

As we stated for the first form:

This remains valid and analytically elegant, assuming non-degeneracy of the determinant.

4.2. Second Form of the Weighted Difference (Optimizing over )

In this second formulation, the goal is to express the squared deviation

in terms of: unknowns

; given or pre-specified

,

,

:

where

,

are known and computed as in your previous transformation.

This form interprets the deviation of the trajectory of

from a constant-radius circle centered at

, while

is obtained from the known transformation of points

and the offset between moving frames [

18].

Transformation of coordinates:

In the current second form, the goal is to minimize the sum:

Then, the necessary conditions:

lead to the linear system:

where

.

4.3. Third Form of the Weighted Difference (Optimizing over )

In this third formulation, the goal is to express the squared deviation

in terms of: unknowns

; given or pre-specified

,

,

:

where

,

are known now derived from transformation involving

.

Transformation for

,

:

This equation computes the position of point in the global coordinate system using relative motion from point of view.

In the current second form, the goal is to minimize the sum:

Then the minimization conditions:

lead to the linear system:

where

.

Each system is linear and solvable using matrix methods or Cramer’s rule (as we noted, if determinant ).

4.4. Reduction of Full 7 Variable System to 4 Variables

Earlier, you broke this down into:

First form expressed via ;

Second form via ;

Third form via .

We now derive the necessary conditions for minimum with respect to:

Using Cramer’s rule:

we substitute into the four equations and obtain:

This is the final reduced system in four unknowns: , , where , , , , , , are known, and , , are determinantal expressions from system Eq. (17).

We correctly analyzed the structure of system Eq. (28), derived from the necessary conditions:

This results in a system of four nonlinear algebraic equations of degree 9 in the unknowns: , .

Thus, the total number of complex roots is: . And the maximum number of real roots is approximately: .

Each of these 625 real roots corresponds to: A local minimum, maximum, saddle, or ridge point of the surface:

. To distinguish between them, you’d need to analyze the Hessian matrix of second partial derivatives (a 4×4 matrix in this case). The direct algebraic approach to solving this nonlinear system is computationally intractable and inefficient for practical synthesis [

19], despite being mathematically rigorous.

A numerical algorithm for minimizing the function

, using the fact that it’s a smooth, differentiable function of four variables. Thus, while system Eq. (28) provides an exact algebraic framework, solving it directly leads to a system of four ninth-degree algebraic equations with up to 6561 theoretical solutions, among which only a subset represents valid physical configurations [

20]. Verifying the nature of these critical points through second derivative tests would require the evaluation of the Hessian matrix - a process both analytically and computationally intensive. For this reason, the direct algebraic method is impractical. Instead, a more efficient and robust approach involves minimizing the function

numerically, using iterative optimization techniques, which will be presented below based on the following theorem.

Theorem 1. Let the minimal values of the sum of squared differences

for

given positions be defined as follows:

Let:

and be the initial guesses, be the solution minimizing over (from system Eq. (17)) for fixed , ;

be the solution minimizing over (from system Eq. (21)) for fixed , ;

be the solution minimizing over (from system Eq. (24)) for fixed , .

Then the following inequality holds:

Proof of Theorem 1. Stage 1: For fixed initial values

,

, system (17) has a unique solution

minimizing

over

. Hence:

Stage 2: Fixing

and

, system Eq. (21) gives a unique solution

minimizing

over

:

Since this is a minimization over a larger space than in

(i.e., more variables allowed to vary), it follows that:

Stage 3: Fixing

and

, system Eq. (24) provides a unique solution

minimizing

over

:

Again, since the minimization is over more variables than in , we have: . Hence, chaining both inequalities yields the final result: .

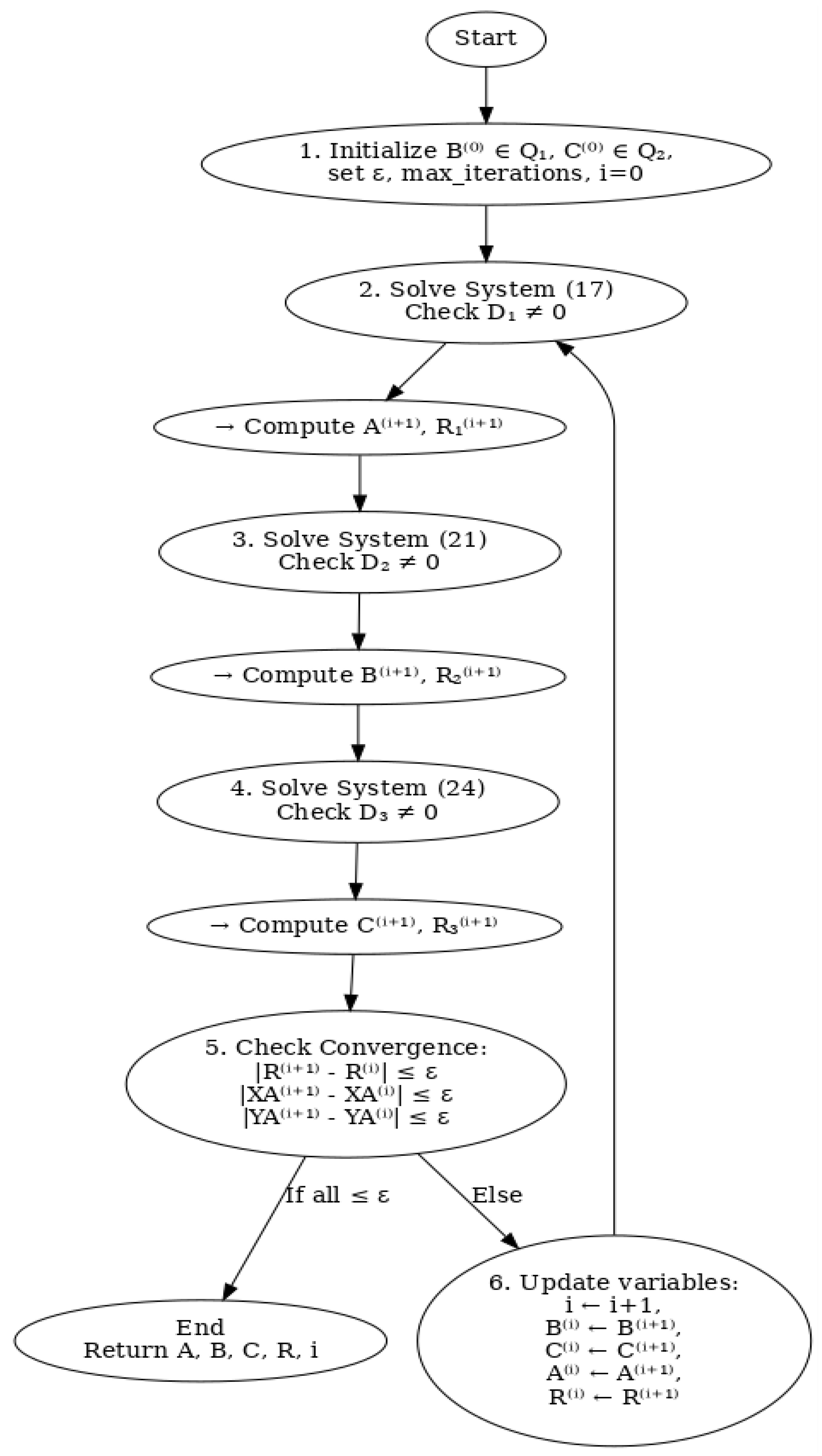

This theorem provides the theoretical foundation for a stepwise iterative minimization algorithm:

Start with initial guesses , ;

Solve system Eq. (17) → get , ;

Solve system Eq. (21) → get , ;

Solve system Eq. (24) → get , ;

Repeat if desired for refinement.

This avoids solving the full 7-variable nonlinear system at once and guarantees non-increasing sequence of errors: .

8. Conclusions

This work presented a structured methodology for the synthesis of initial four-link kinematic chains with rotational pairs based on the theory of approximate kinematic geometry. The approach involved the specification of relative plane-parallel motion between two moving planes with respect to a fixed base, and the solution of the synthesis problem was carried out by minimizing a weighted geometric deviation function.

Key conclusions from this study are as follows:

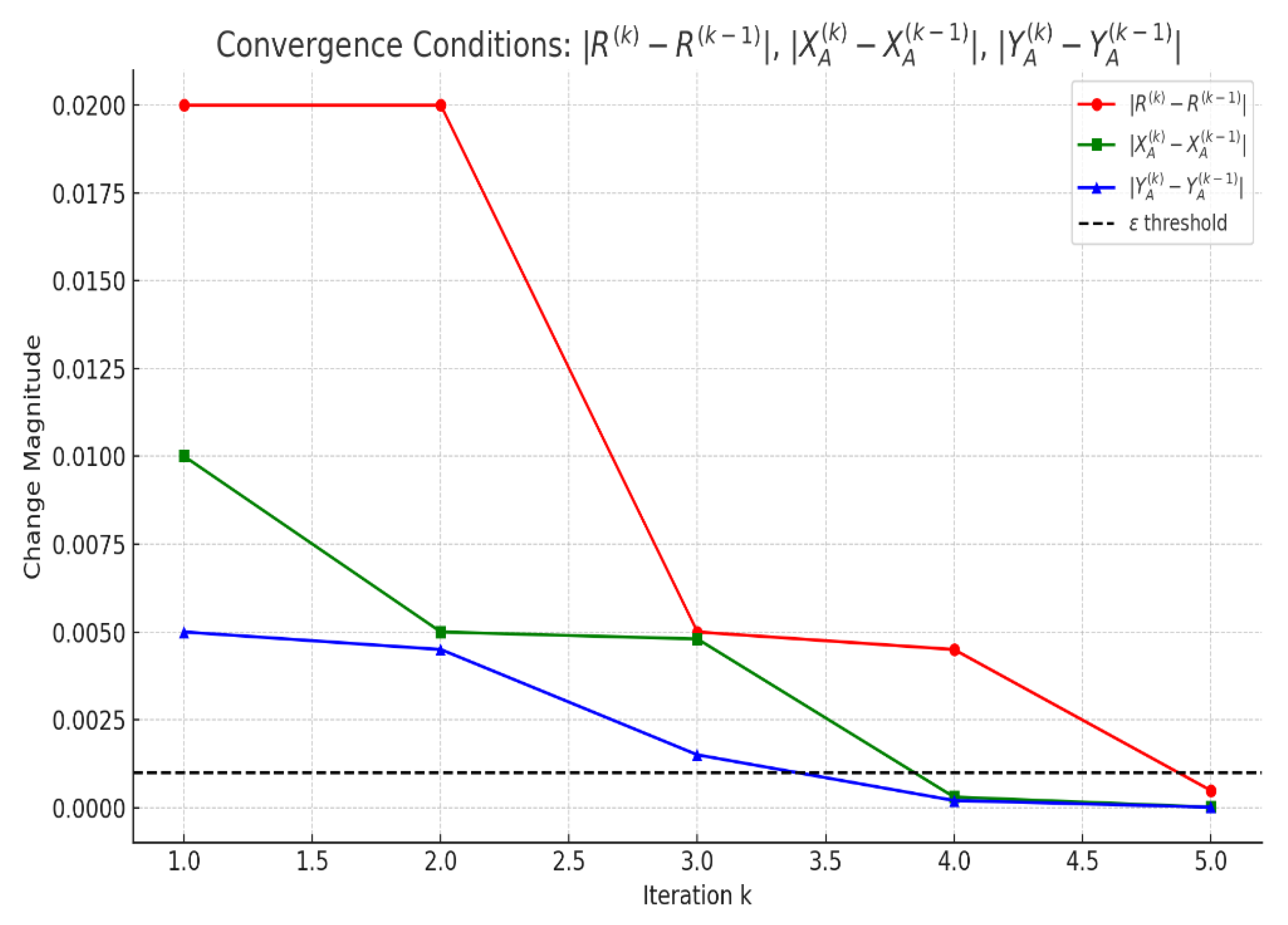

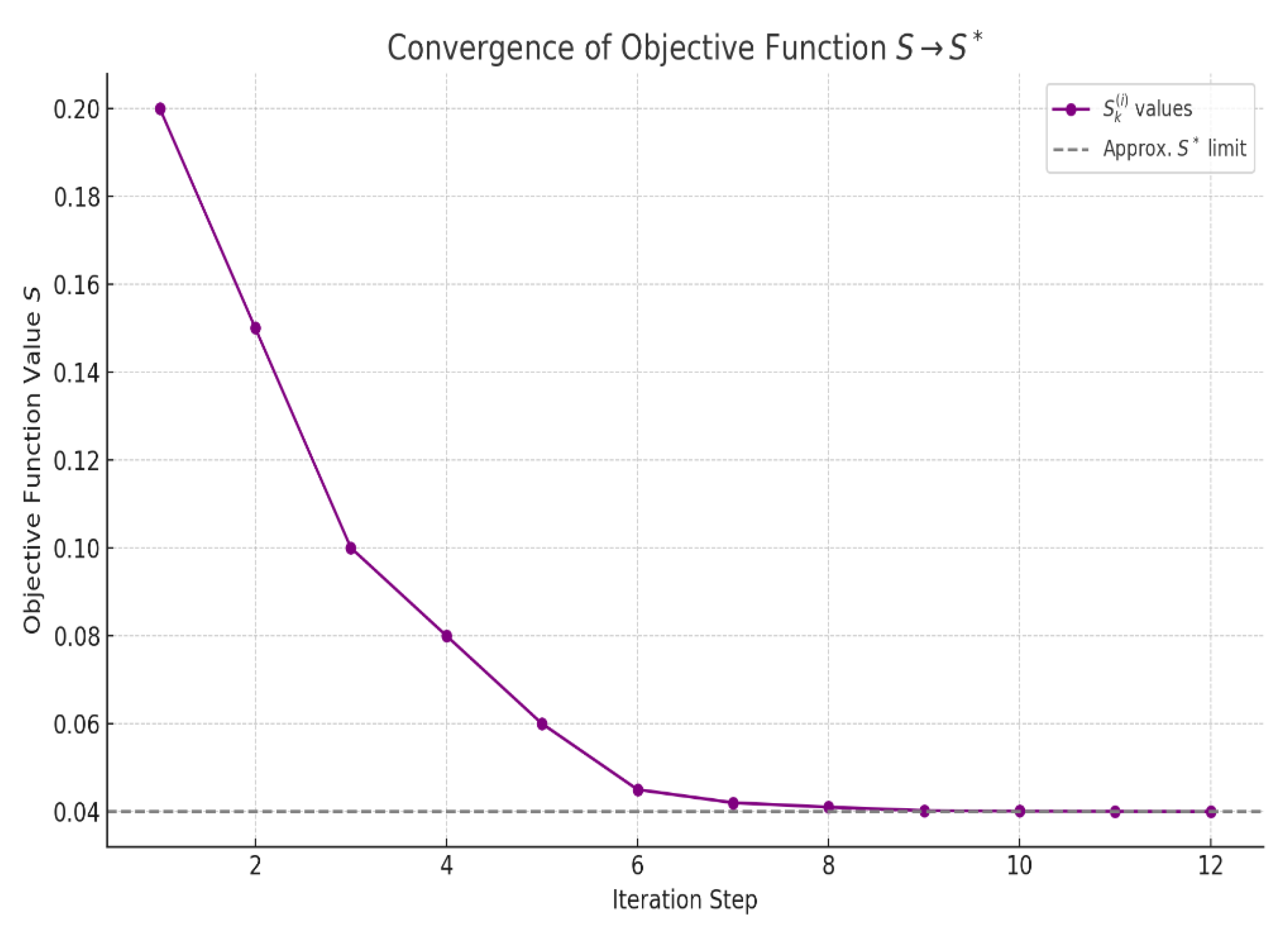

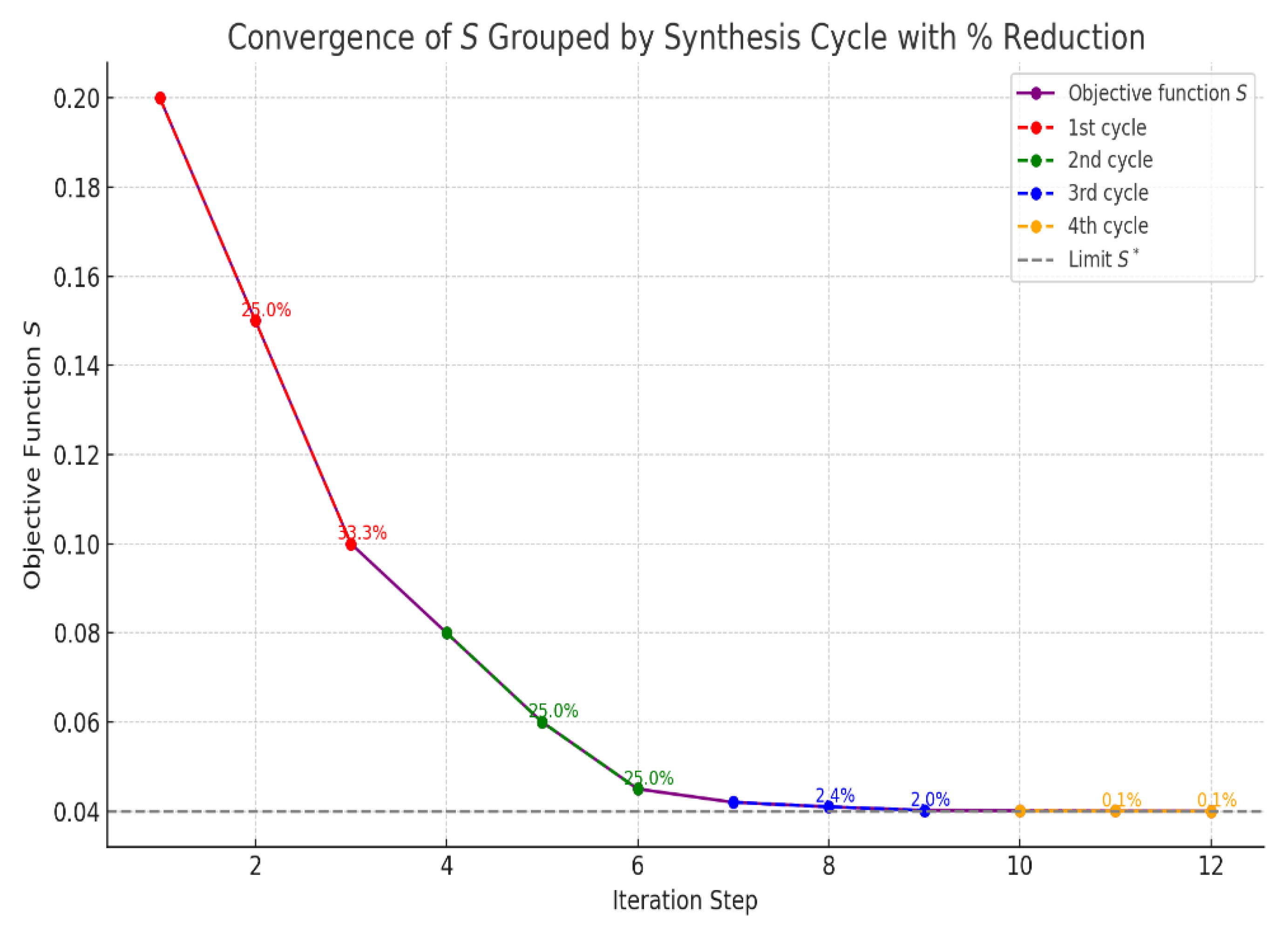

The proposed iterative algorithm, which minimizes the objective function in three stages (for points , , and ), converges reliably to a local minimum. The observed convergence behavior is smooth, with successive values of decreasing monotonically, and convergence criteria based on the changes in , , and are satisfied within a few iterations.

- 2.

Well-conditioned linear systems:

The synthesis process is supported by solving three linear systems (corresponding to systems Eq. (17), Eq. (21), and Eq. (24)), and determinant testing confirmed that the systems are non-singular , , for the provided input configurations. This indicates that the algorithm is numerically stable and the synthesis conditions are well-posed.

- 3.

Geometrical accuracy of link placement:

The positions of the synthesized points and relative to the base lie on circles of radius , verifying the geometrical correctness of the linkage design. The visualizations show that the synthesized four-link mechanism satisfies the constraints of consistent angular displacements and relative orientations.

- 4.

Modular and extendable framework:

The methodology allows for modular implementation, with each synthesis step being independently solvable and verifiable. This makes it especially suitable for computer-aided mechanism design applications and opens up possibilities for extension to mechanisms with translational joints or higher degrees of freedom.

- 5.

Effective error minimization strategy:

The use of staged error minimization - optimizing each subset of variables sequentially - reduces computational complexity while maintaining synthesis accuracy. This approach provides a practical and scalable solution for the synthesis of planar mechanisms.

In summary, the developed algorithm offers a reliable, accurate, and computationally efficient technique for the synthesis of initial four-link mechanisms under geometrical motion constraints. It serves as a solid foundation for further developments in mechanism synthesis, including the integration of dynamic constraints, optimization under workspace limitations, and generalization to spatial linkages.

Figure 1.

Configurations of synthesized initial kinematic chains: closed four-bar link chain (ABCD) and open variants (ACD, ABD).

Figure 1.

Configurations of synthesized initial kinematic chains: closed four-bar link chain (ABCD) and open variants (ACD, ABD).

Figure 2.

Configurations of ACD and AD kinematic chains with translational pairs.

Figure 2.

Configurations of ACD and AD kinematic chains with translational pairs.

Figure 3.

Configurations of ABD and AD kinematic chains with translational pairs.

Figure 3.

Configurations of ABD and AD kinematic chains with translational pairs.

Figure 4.

The algorithm visualizes the entire iterative synthesis algorithm for four-link kinematic chains with rotational pairs, showing each computational step and convergence condition clearly.

Figure 4.

The algorithm visualizes the entire iterative synthesis algorithm for four-link kinematic chains with rotational pairs, showing each computational step and convergence condition clearly.

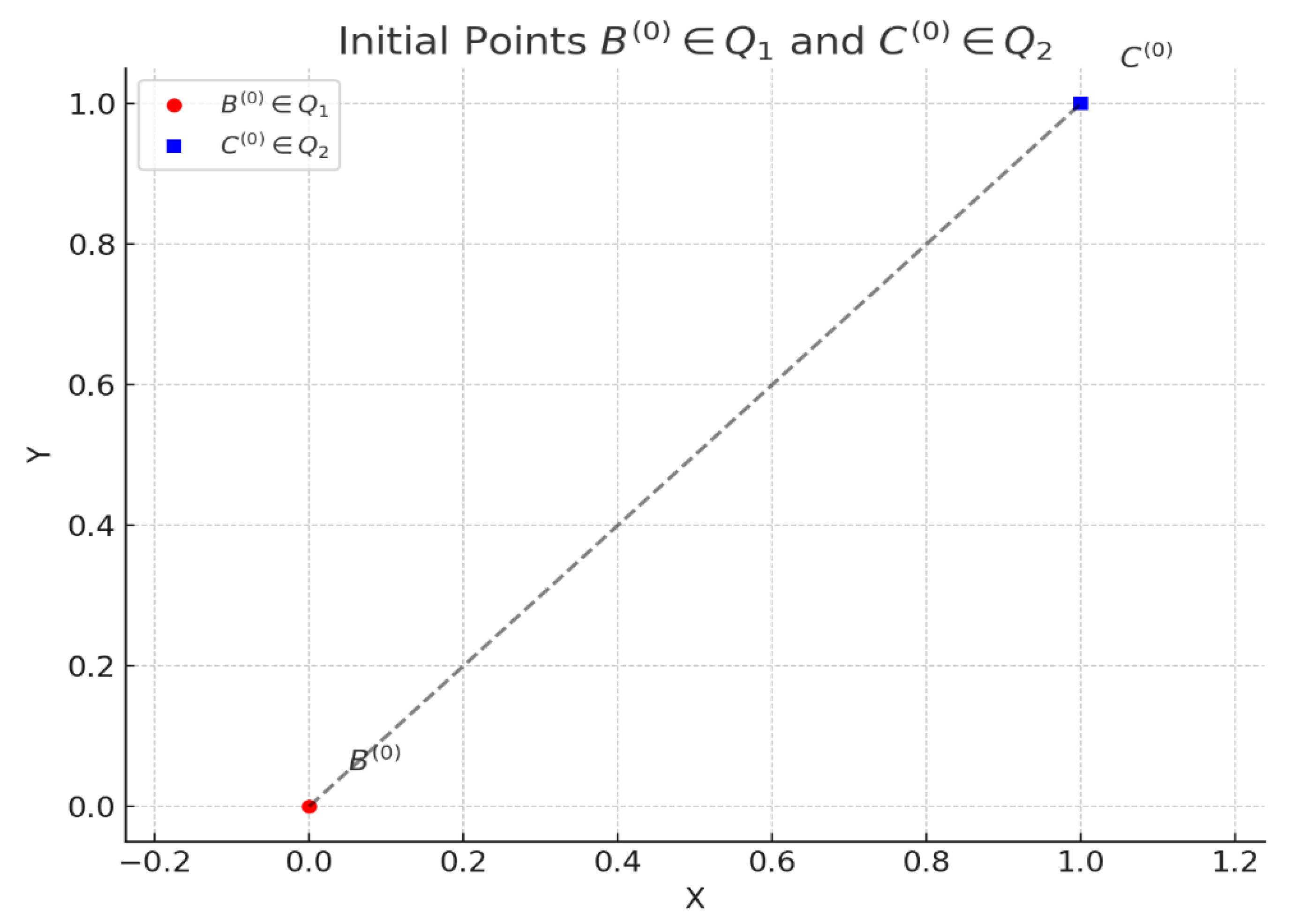

Figure 5.

The 2D plot showing the initial positions of the points: shown as a red circle, and shown as a blue square, a dashed line connects them to indicate their initial relative position.

Figure 5.

The 2D plot showing the initial positions of the points: shown as a red circle, and shown as a blue square, a dashed line connects them to indicate their initial relative position.

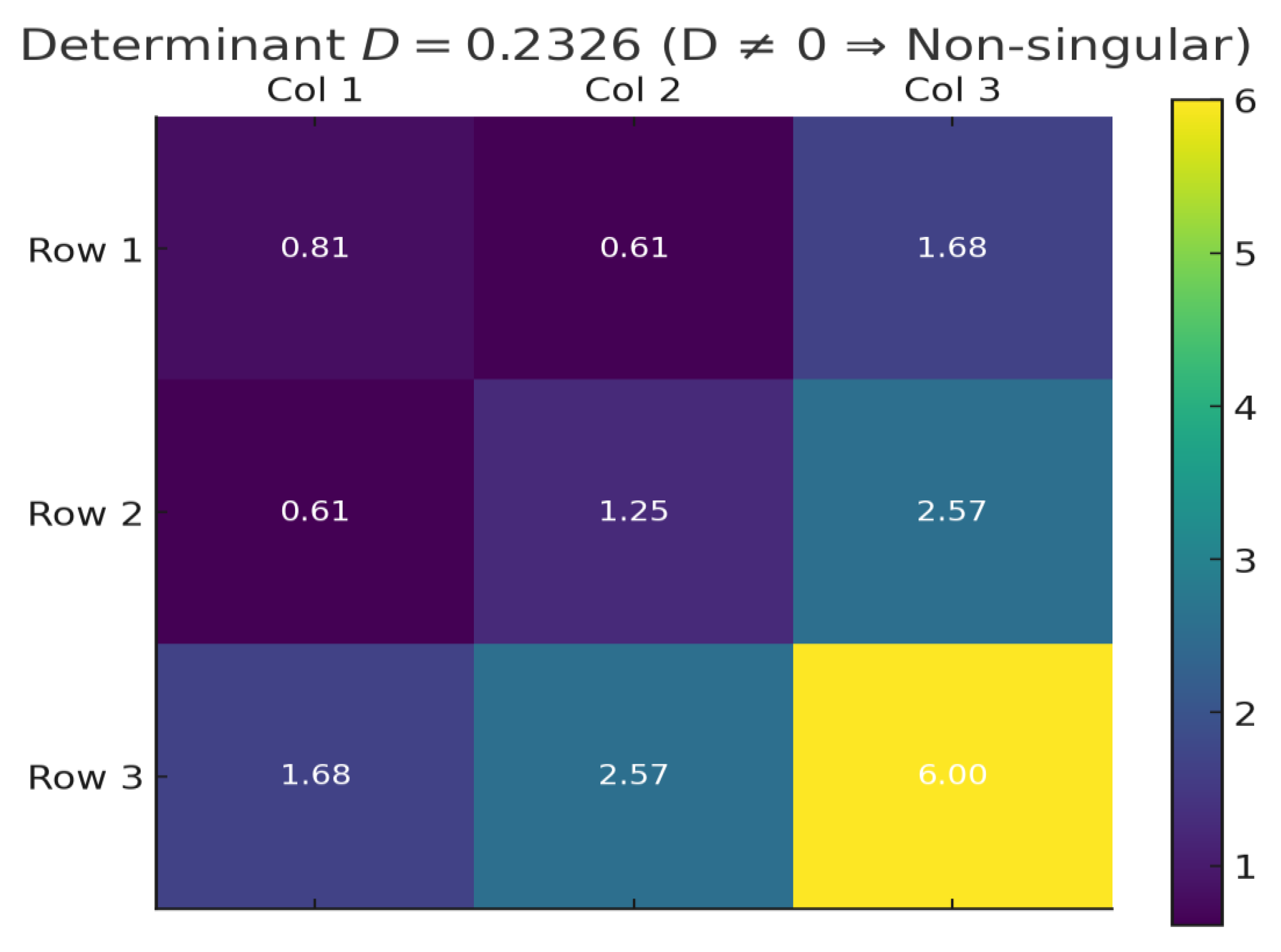

Figure 6.

This confirms the system is non-singular and suitable for performing the basic iterative synthesis step. The matrix for system Eq. (17) has a non-zero determinant: .

Figure 6.

This confirms the system is non-singular and suitable for performing the basic iterative synthesis step. The matrix for system Eq. (17) has a non-zero determinant: .

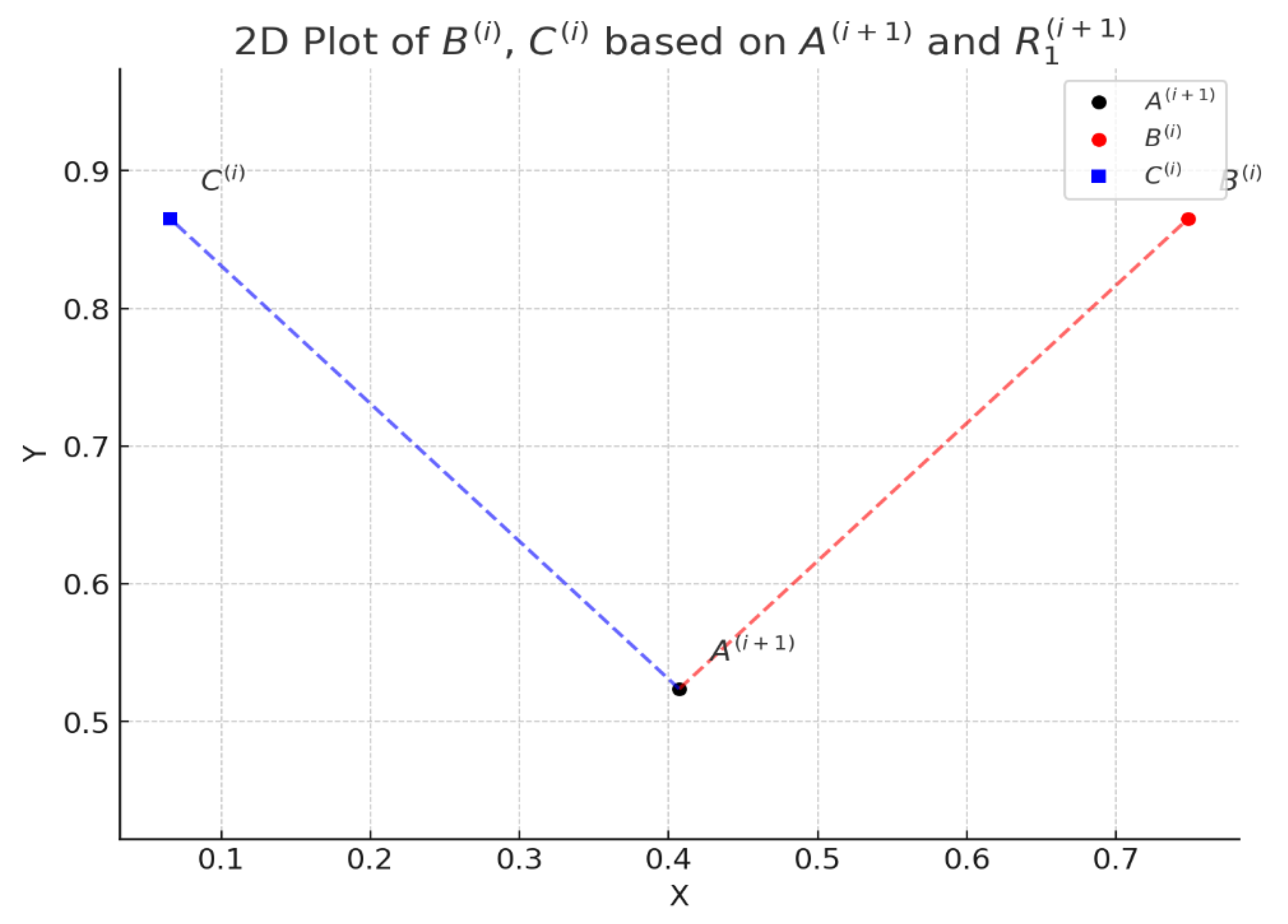

Figure 7.

This 2D plot shows: the computed base point from the synthesis step; and two points lying on a circle of radius around ; Dashed lines represent the virtual links connecting to both and .

Figure 7.

This 2D plot shows: the computed base point from the synthesis step; and two points lying on a circle of radius around ; Dashed lines represent the virtual links connecting to both and .

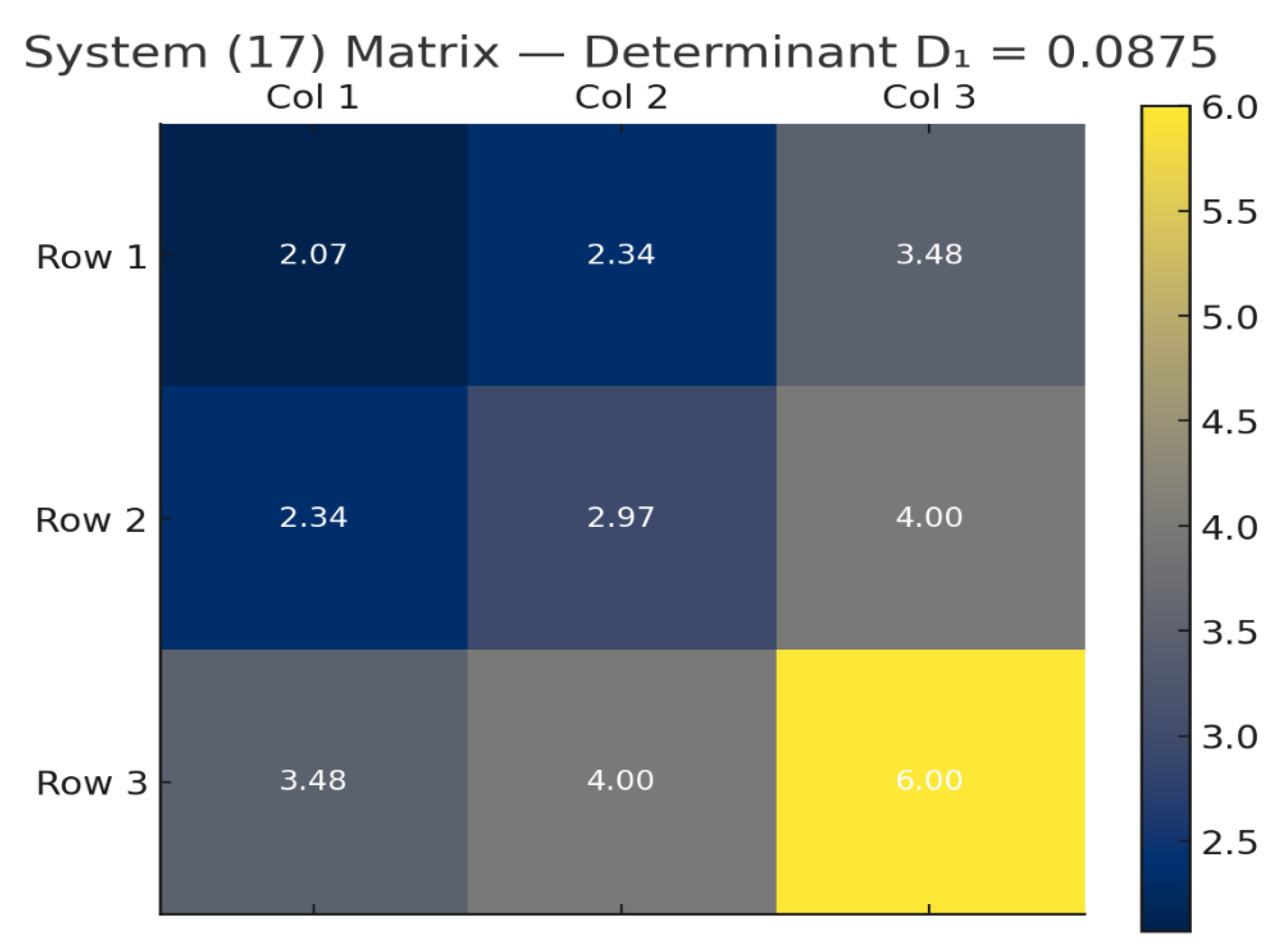

Figure 8.

This confirms the system is non-singular and solvable, and the computed values are valid for continuing the synthesis process. Results of the basic iterative synthesis step: , , . Determinant .

Figure 8.

This confirms the system is non-singular and solvable, and the computed values are valid for continuing the synthesis process. Results of the basic iterative synthesis step: , , . Determinant .

Figure 9.

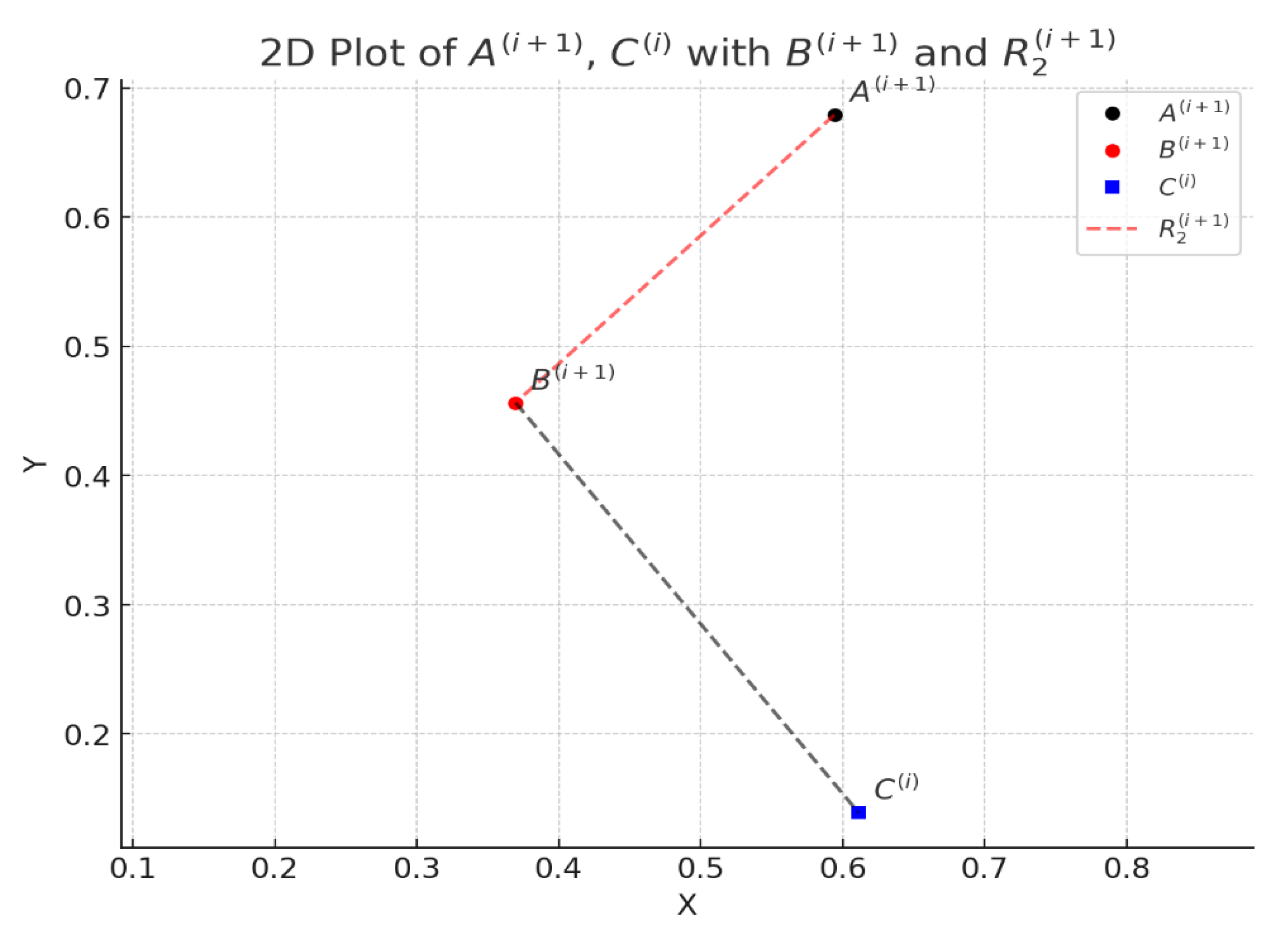

This 2D plot visualizes the synthesis step using: the updated base point; the new hinge point derived from system Eq. (21); the previous point on the second moving plane; Dashed line: shows the synthesized link between and ; Black dashed line: represents the connection to the known point .

Figure 9.

This 2D plot visualizes the synthesis step using: the updated base point; the new hinge point derived from system Eq. (21); the previous point on the second moving plane; Dashed line: shows the synthesized link between and ; Black dashed line: represents the connection to the known point .

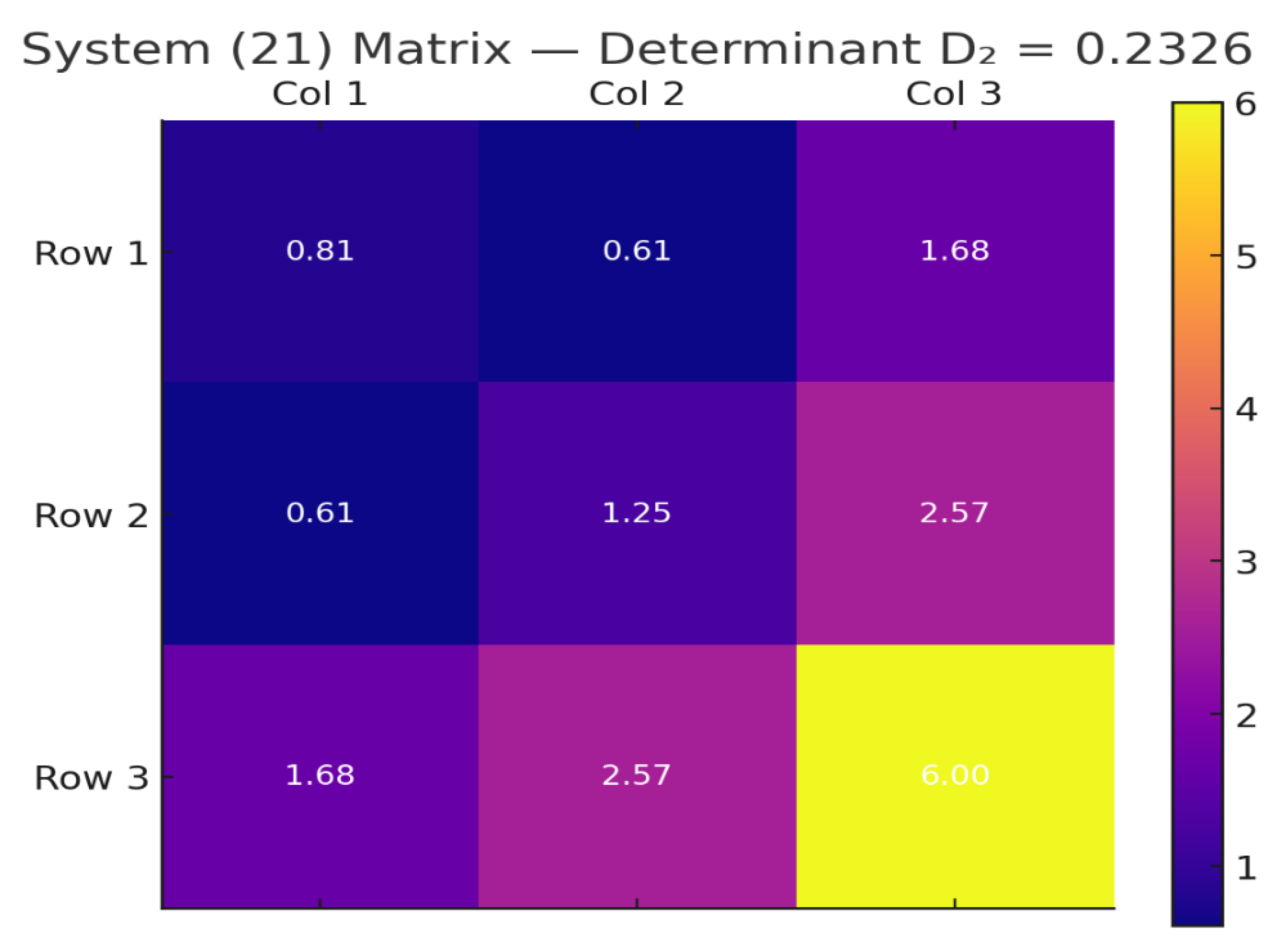

Figure 10.

The 2D heatmap shows the coefficient matrix used in system Eq. (21) for the second synthesis step. Results of the basic iterative synthesis step: , , . Determinant .

Figure 10.

The 2D heatmap shows the coefficient matrix used in system Eq. (21) for the second synthesis step. Results of the basic iterative synthesis step: , , . Determinant .

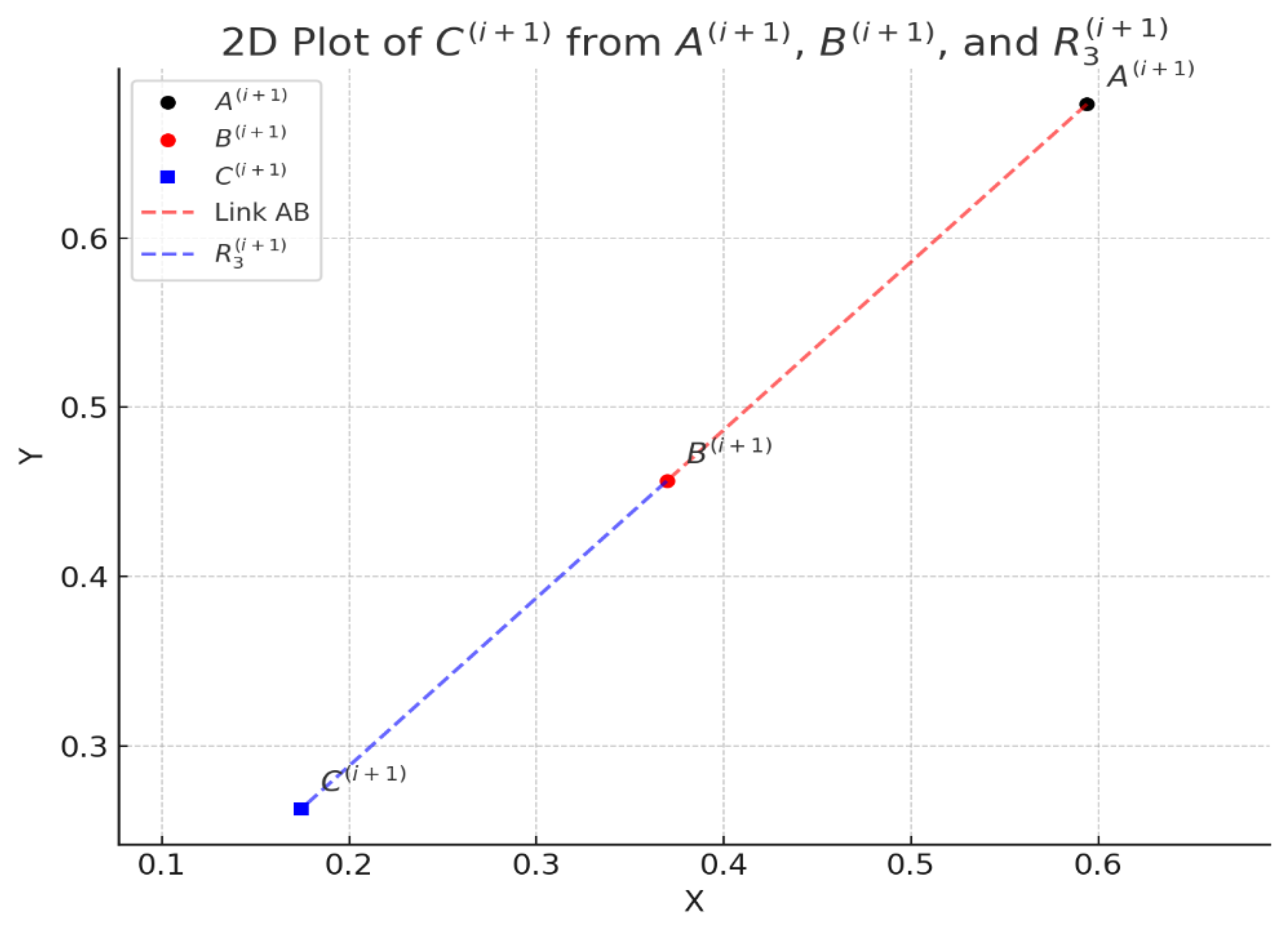

Figure 11.

This 2D plot completes the synthesis step by showing: the fixed base point; the intermediate hinge point; computed along the extended direction from through , at distance ; Dashed lines indicate the link segments: red for , blue for .

Figure 11.

This 2D plot completes the synthesis step by showing: the fixed base point; the intermediate hinge point; computed along the extended direction from through , at distance ; Dashed lines indicate the link segments: red for , blue for .

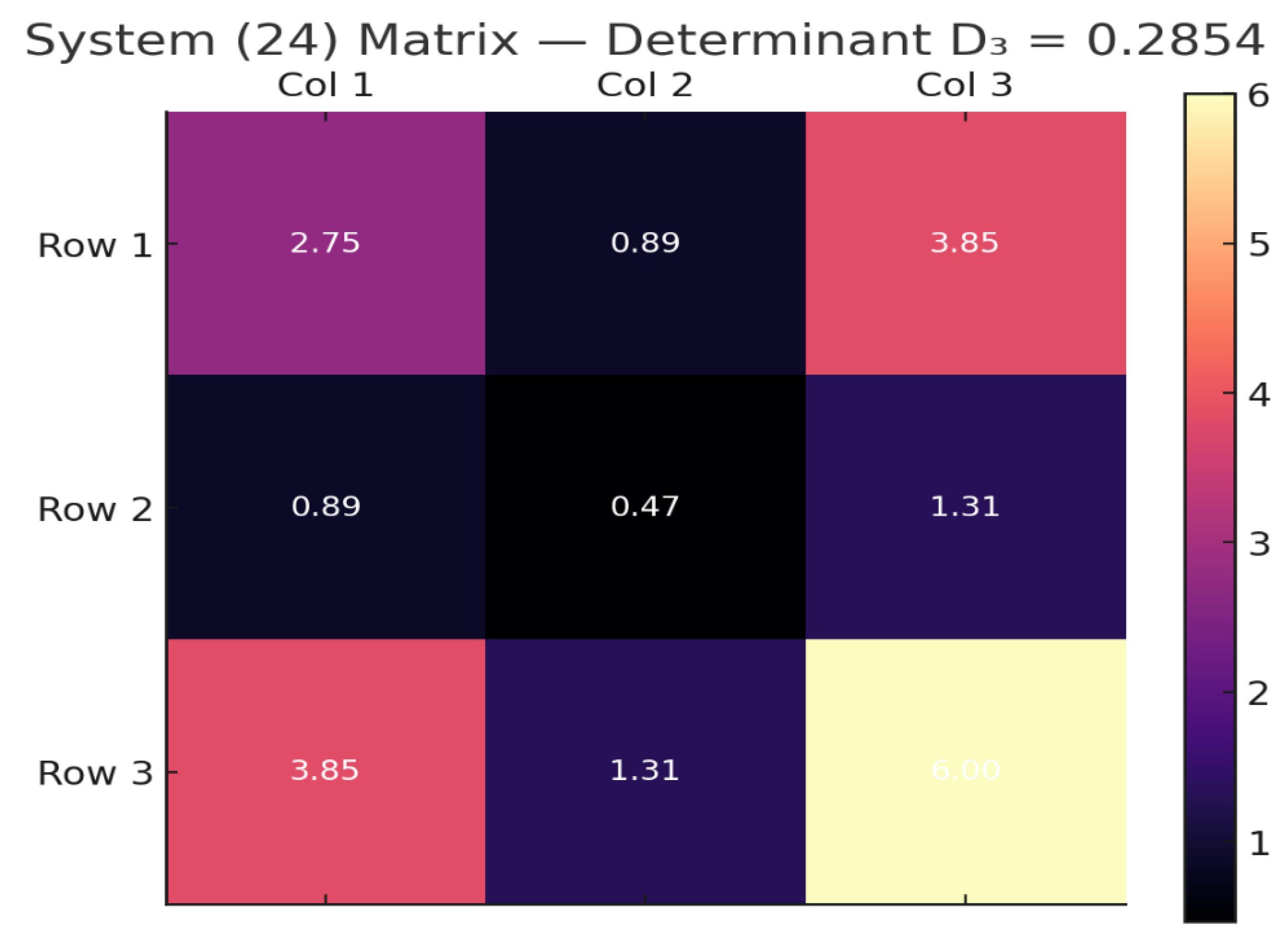

Figure 12.

The 2D heatmap above visualizes the coefficient matrix used in system Eq. (24) for the final step of your synthesis loop. Results of the final iterative step: , , . Determinant .

Figure 12.

The 2D heatmap above visualizes the coefficient matrix used in system Eq. (24) for the final step of your synthesis loop. Results of the final iterative step: , , . Determinant .

Figure 13.

This 2D plot visualizes the convergence behavior of the iterative synthesis process: Red line change in link length ; Green line: change in base point x-coordinate ; Blue line: change in base point y-coordinate ; The black dashed line shows the threshold . As the iterations progress, all three quantities approach or drop below the threshold — confirming convergence.

Figure 13.

This 2D plot visualizes the convergence behavior of the iterative synthesis process: Red line change in link length ; Green line: change in base point x-coordinate ; Blue line: change in base point y-coordinate ; The black dashed line shows the threshold . As the iterations progress, all three quantities approach or drop below the threshold — confirming convergence.

Figure 14.

This 2D plot shows the convergence of the objective function over successive synthesis stages: Each point represents a step in the optimization (e.g., solving for , then , then ); The gray dashed line shows the limit , the locally minimized value of the function.

Figure 14.

This 2D plot shows the convergence of the objective function over successive synthesis stages: Each point represents a step in the optimization (e.g., solving for , then , then ); The gray dashed line shows the limit , the locally minimized value of the function.

Figure 15.

This graph illustrates the convergence of the objective function across four synthesis cycles, with each cycle consisting of three steps: solving for , , and . Each color-coded segment represents one synthesis cycle: Red 1st cycle ; Green 2nd cycle ; Blue 3rd cycle ; Orange 4th cycle . Percentage reductions between each stage are annotated beside the markers, showing effective drop in error per synthesis step. The dashed horizontal line represents the asymptotic limit , confirming convergence of the objective function.

Figure 15.

This graph illustrates the convergence of the objective function across four synthesis cycles, with each cycle consisting of three steps: solving for , , and . Each color-coded segment represents one synthesis cycle: Red 1st cycle ; Green 2nd cycle ; Blue 3rd cycle ; Orange 4th cycle . Percentage reductions between each stage are annotated beside the markers, showing effective drop in error per synthesis step. The dashed horizontal line represents the asymptotic limit , confirming convergence of the objective function.