Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

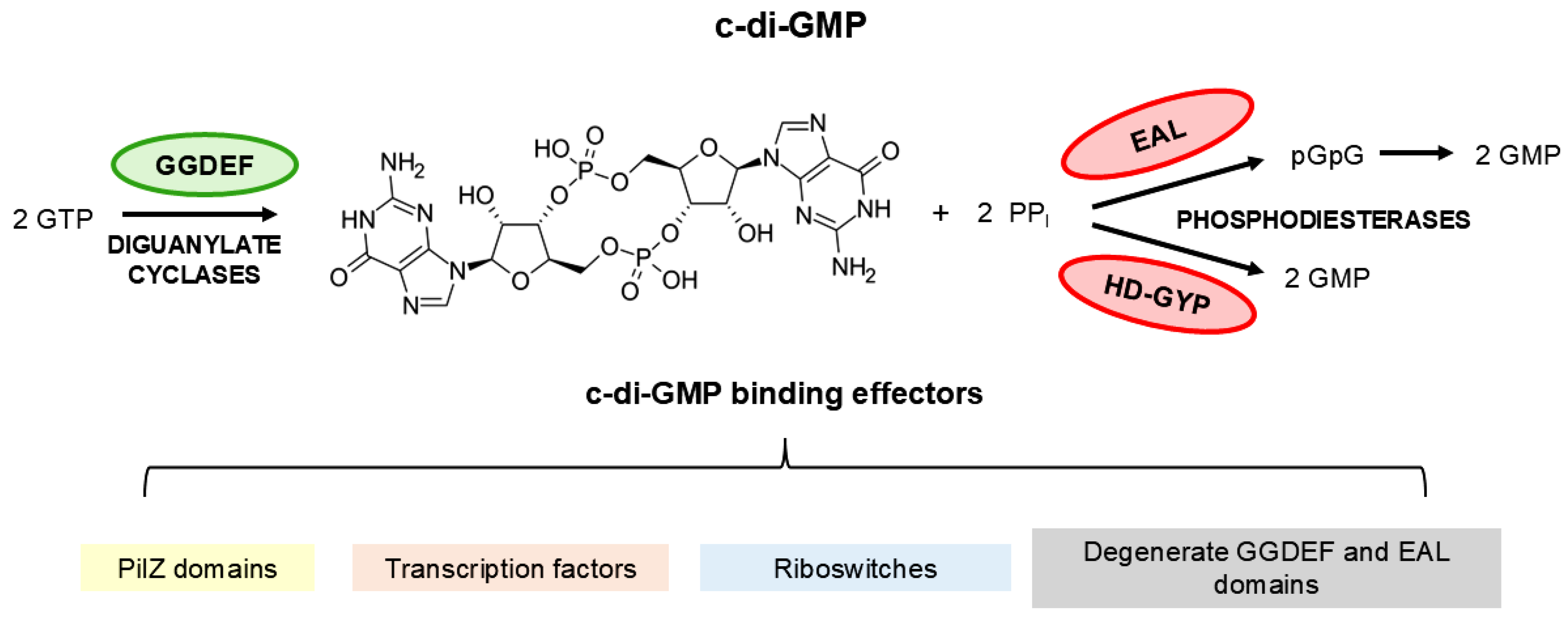

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

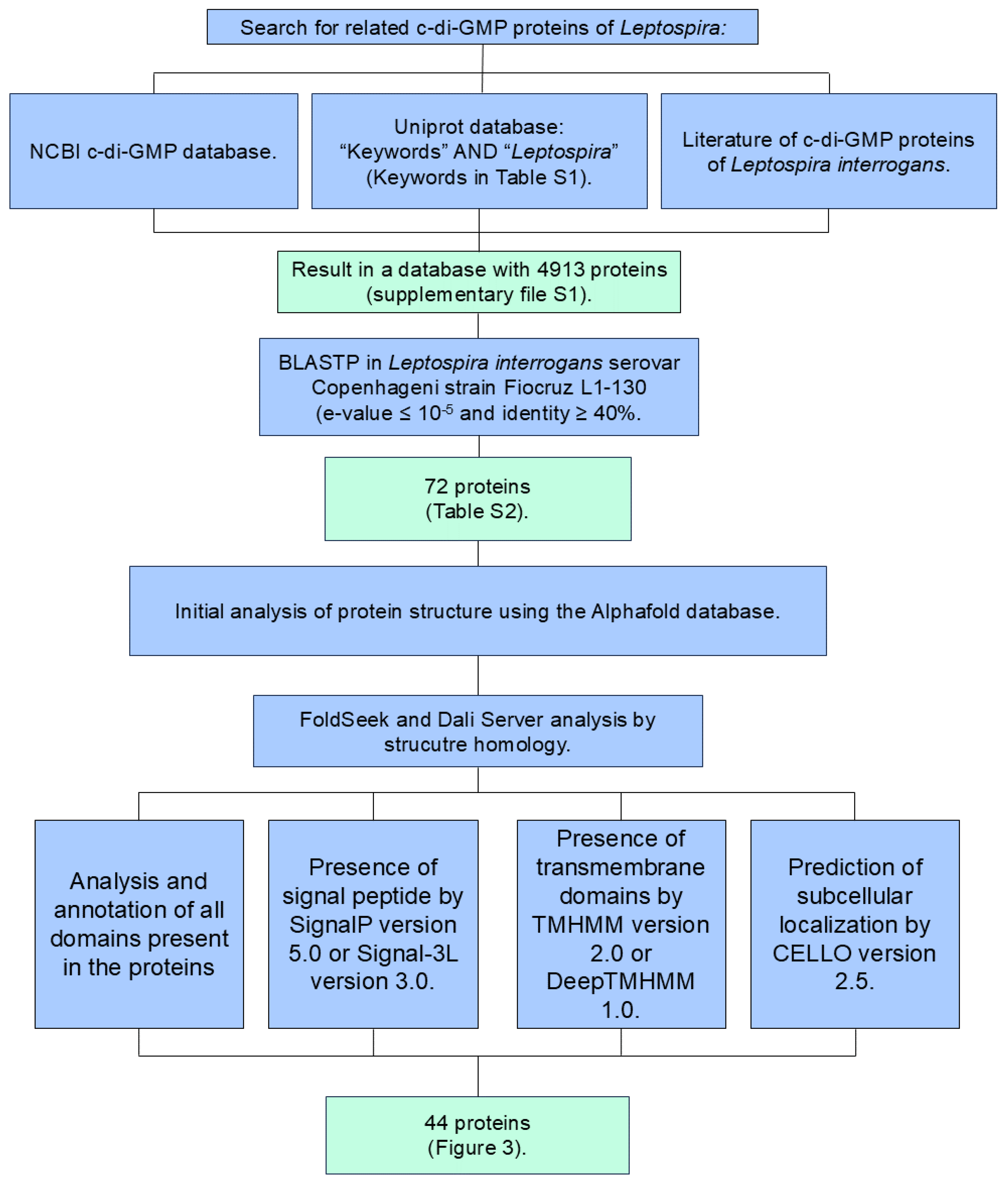

2.1. Potential Proteins Involved in c-di-GMP Signaling in L. interrogans: Bioinformatic Analysis and Structural Prediction Models

2.2. Functional and Structural Characterization of Identified Proteins: An Analytical Approach

2.3. Multiple Amino acid Sequence Alignment using Three-dimensional Structure Predictions

2.4. Graphical, Structural, and Imaging Software tools

3. Results

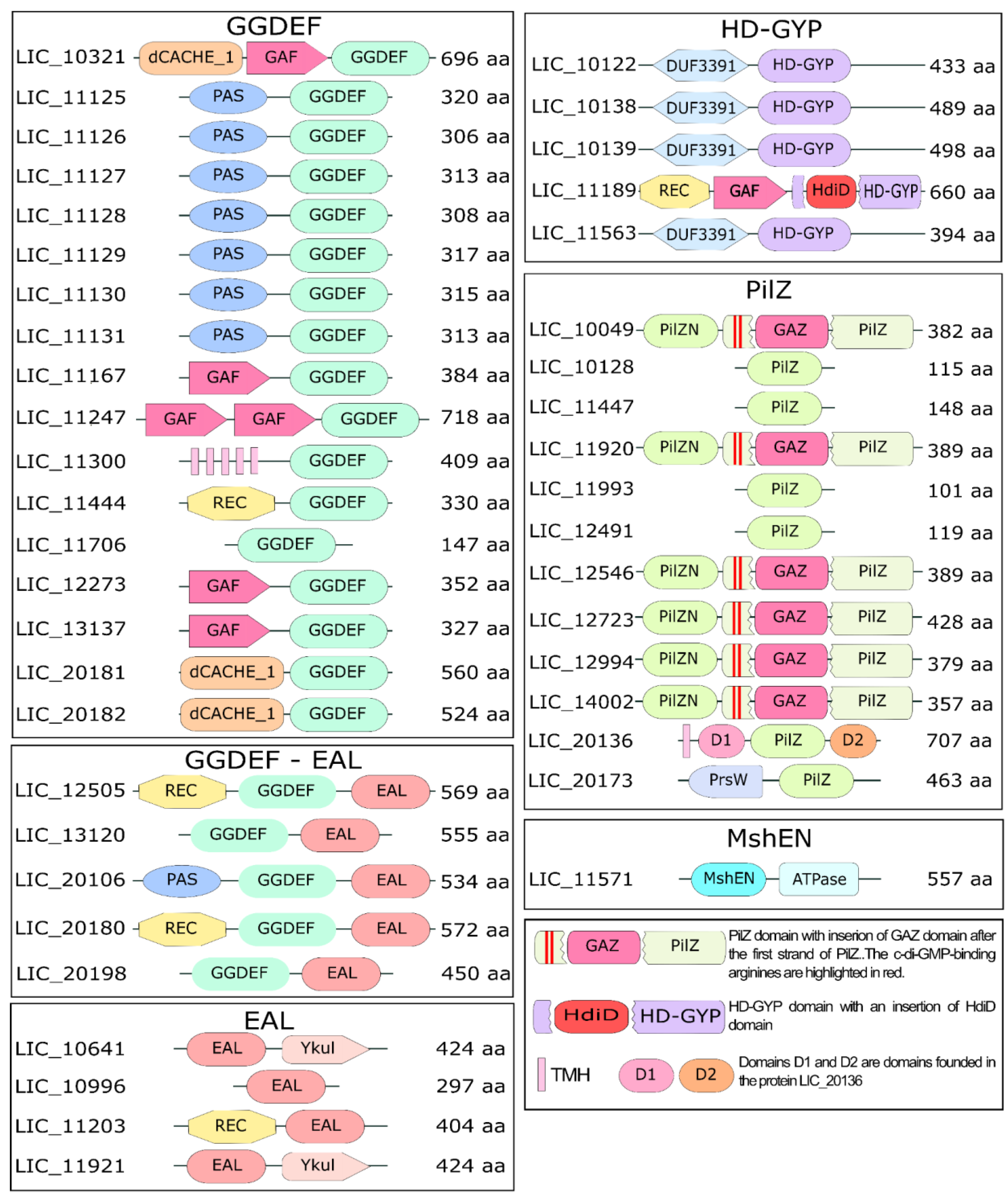

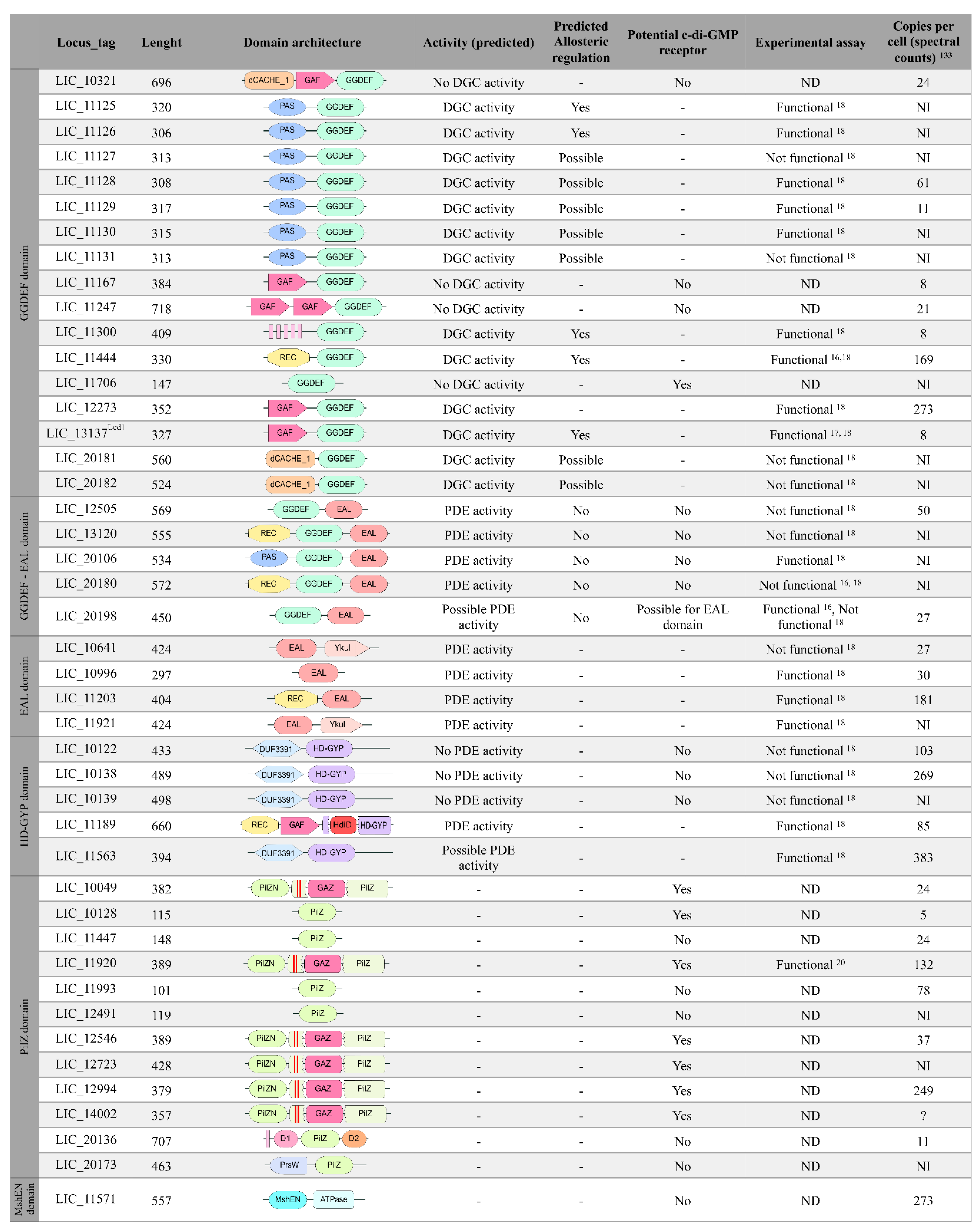

3.1. Identification of c-di-GMP-Related Genes in L. interrogans

3.3. Diversity of Sensor Domains Present in c-di-GMP-Related Proteins

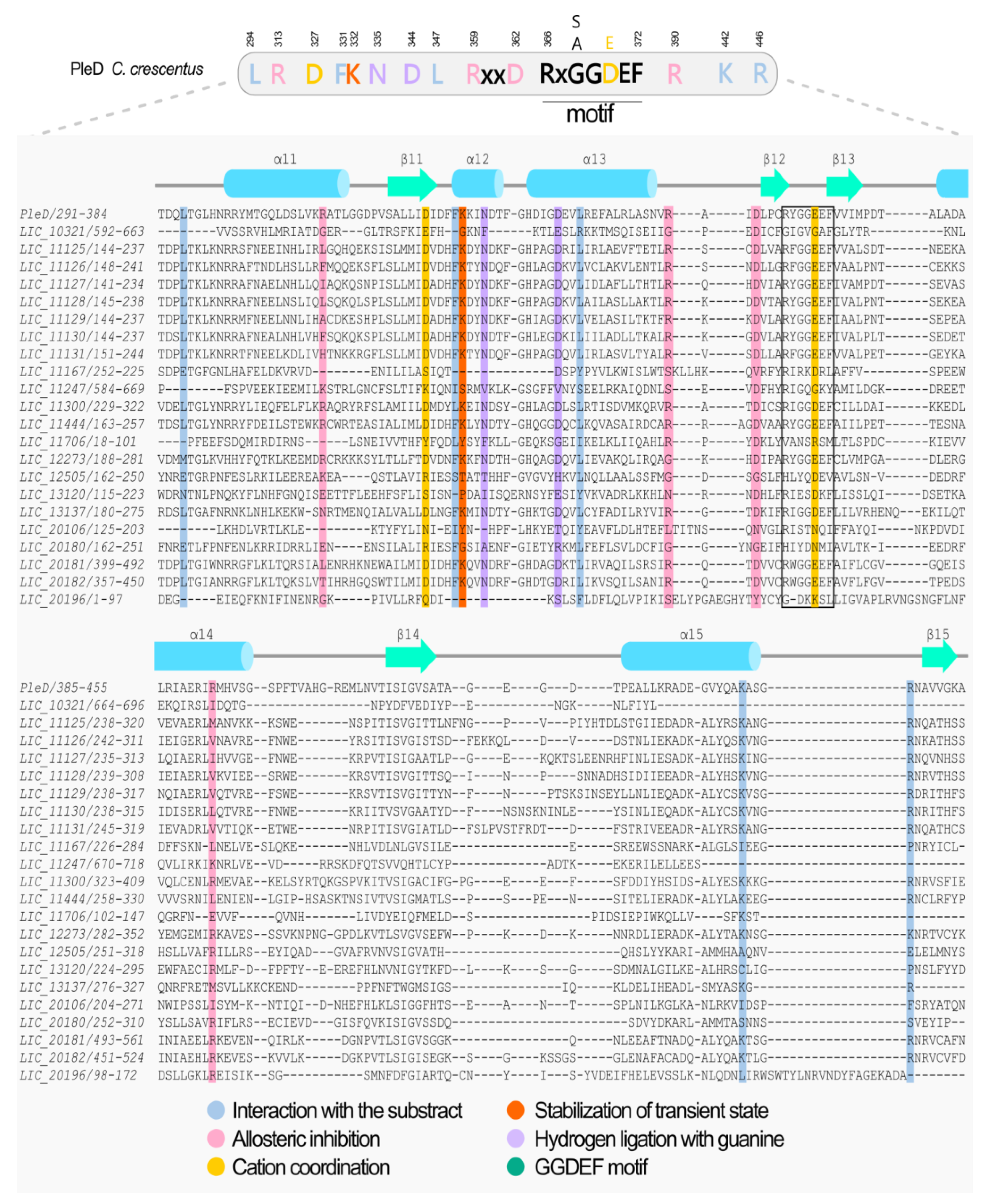

3.4. Diguanylate Cyclases

3.5. Proteins Containing EAL Domains

3.6. The Proteins Containing HD-GYP Domain Characterization

3.7. The Insertion in the HD-GYP of LIC_11189 Is Widely Distributed in Response-Regulator HD-GYP Proteins

3.8. Potential Distant Members of DUF3391 Family

3.9. A novel C-Terminal Domain in HD-GYP-Containing Proteins

3.10. Proteins Containing PilZ Domain

3.11. The LIC_20136 and LIC_20173 Represent Novel PilZ-like Families with Unique Domains Architecture

3.12. Proteins Containing the MshEN Domain in L. interrogans Serovar Copenhageni Strain Fiocruz L1-130

4. Discussion

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Davignon, G.; et al. Leptospira interrogans biofilm transcriptome highlights adaption to starvation and general stress while maintaining virulence. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bonhomme, D.; Werts, C. Host and Species-Specificities of Pattern Recognition Receptors Upon Infection With Leptospira interrogans. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2022, 12, 932137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philip, N.; et al. Leptospira interrogans and Leptospira kirschneri are the dominant Leptospira species causing human leptospirosis in Central Malaysia. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2020, 14, e0008197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pětrošová, H.; et al. Lipid A structural diversity among members of the genus Leptospira. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1181034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vincent, A.T.; et al. Revisiting the taxonomy and evolution of pathogenicity of the genus Leptospira through the prism of genomics. PLoS Negl. Trop. Dis. 2019, 13, e0007270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brazil. Ministry of Health. Leptospirosis. Available online: https://www.gov.br/saude/pt-br/assuntos/saude-de-a-a-z/l/leptospirose#:~:text=A%20leptospirose%20%C3%A9%20uma%20doen%C3%A7a,contaminada%20ou%20por%20meio%20de (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Rajapakse, S. Leptospirosis: Clinical aspects. Clin. Med. 2022, 22, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bharti, A.R.; et al. Leptospirosis: A zoonotic disease of global importance. Lancet Infect. Dis. 2003, 3, 757–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupouey, J.; et al. Human leptospirosis: An emerging risk in Europe? Comp. Immunol. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2014, 37, 77–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, A.M.; Stull, J.W.; Moore, G.E. Potential Drivers for the Re-Emergence of Canine Leptospirosis in the United States and Canada. Trop. Med. Infect. Dis. 2022, 7, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OCHA; United Nations. Brazil: Floods in Rio Grande do Sul - United Nations Situation Report, as of 20 September 2024. Available online: https://www.unocha.org/publications/report/brazil/brazil-floods-rio-grande-do-sul-united-nations-situation-report-20-september-2024 (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- PAHO, World Health Organization (WHO); United Nations. PAHO supports emergency response following flooding in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil. Available online: https://www.paho.org/en/news/3-7-2024-paho-supports-emergency-response-following-flooding-rio-grande-do-sul-brazil (accessed on 28 April 2025).

- Martins-Filho, P.R.; Croda, J.; Araújo, A.A.D.S.; Correia, D.; Quintans-Júnior, L.J. Catastrophic Floods in Rio Grande do Sul, Brazil: The Need for Public Health Responses to Potential Infectious Disease Outbreaks. Rev. Soc. Bras. Med. Trop. 2024, 57, e00603-2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ziliotto, M.; Chies, J.A.B.; Ellwanger, J.H. Extreme Weather Events and Pathogen Pollution Fuel Infectious Diseases: The 2024 Flood-Related Leptospirosis Outbreak in Southern Brazil and Other Red Lights. Pollutants 2024, 4, 424–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davignon, G.; et al. Leptospira interrogans biofilm transcriptome highlights adaption to starvation and general stress while maintaining virulence. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2024, 10, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thibeaux, R.; et al. The zoonotic pathogen Leptospira interrogans mitigates environmental stress through cyclic-di-GMP-controlled biofilm production. Npj Biofilms Microbiomes 2020, 6, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Costa Vasconcelos, F.N.; et al. Structural and Enzymatic Characterization of a cAMP-Dependent Diguanylate Cyclase from Pathogenic Leptospira Species. J. Mol. Biol. 2017, 429, 2337–2352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, G.; et al. Identification and Characterization of c-di-GMP Metabolic Enzymes of Leptospira interrogans and c-di-GMP Fluctuations After Thermal Shift and Infection. Front. Microbiol. 2018, 9, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vasconcelos, L.; et al. Genomic insights into the c-di-GMP signaling and biofilm development in the saprophytic spirochete Leptospira biflexa. Arch. Microbiol. 2023, 205, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visnardi, A.B.; et al. Insertion of a Divergent GAF-like Domain Defines a Novel Family of YcgR Homologues That Bind c-di-GMP in Leptospirales. ACS Omega 2025, 10, 3988–4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheang, Q.W.; Xin, L.; Chea, R.Y.F.; Liang, Z.-X. Emerging paradigms for PilZ domain-mediated C-di-GMP signaling. Biochem. Soc. Trans. 2019, 47, 381–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Römling, U.; Galperin, M.Y.; Gomelsky, M. Cyclic di-GMP: The First 25 Years of a Universal Bacterial Second Messenger. Microbiol. Mol. Biol. Rev. 2013, 77, 1–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, S.; Sauer, K. Controlling Biofilm Development Through Cyclic di-GMP Signaling. In Pseudomonas aeruginosa; Filloux, A., Ramos, J.-L., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; Volume 1386; pp. 69–94. [Google Scholar]

- Blanco-Romero, E.; et al. Role of extracellular matrix components in biofilm formation and adaptation of Pseudomonas ogarae F113 to the rhizosphere environment. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15, 1341728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schirmer, T.; Jenal, U. Structural and mechanistic determinants of c-di-GMP signalling. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2009, 7, 724–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purificação, A.D.D.; Azevedo, N.M.D.; Araujo, G.G.D.; Souza, R.F.D.; Guzzo, C.R. The World of Cyclic Dinucleotides in Bacterial Behavior. Molecules 2020, 25, 2462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fu, Y.; et al. The Multiple Regulatory Relationship Between RNA-Chaperone Hfq and the Second Messenger c-di-GMP. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 689619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valentini, M.; Filloux, A. Biofilms and Cyclic di-GMP (c-di-GMP) Signaling: Lessons from Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Other Bacteria. J. Biol. Chem. 2016, 291, 12547–12555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The UniProt, Consortium; et al. UniProt: The Universal Protein Knowledgebase in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D523–D531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, S.-H.; Galperin, M.Y. Diversity of Cyclic Di-GMP-Binding Proteins and Mechanisms. J. Bacteriol. 2016, 198, 32–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roelofs, K.G.; et al. Systematic Identification of Cyclic-di-GMP Binding Proteins in Vibrio cholerae Reveals a Novel Class of Cyclic-di-GMP-Binding ATPases Associated with Type II Secretion Systems. PLOS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.-C.; et al. Nucleotide binding by the widespread high-affinity cyclic di-GMP receptor MshEN domain. Nat. Commun. 2016, 7, 12481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic local alignment search tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, A.L.T.O.; et al. Genome features of Leptospira interrogans serovar Copenhageni. Braz. J. Med. Biol. Res. 2004, 37, 459–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abramson, J.; et al. Accurate structure prediction of biomolecular interactions with AlphaFold 3. Nature 2024, 630, 493–500. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Kempen, M.; et al. Fast and accurate protein structure search with Foldseek. Nat. Biotechnol. 2024, 42, 243–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holm, L. Dali server: Structural unification of protein families. Nucleic Acids Res. 2022, 50, W210–W215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hildebrand, A.; Remmert, M.; Biegert, A.; Söding, J. Fast and accurate automatic structure prediction with HHpred. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2009, 77, 128–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; et al. The conserved domain database in 2023. Nucleic Acids Res. 2023, 51, D384–D388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Chen, Y.; Lu, C.; Hwang, J. Prediction of protein subcellular localization. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2006, 64, 643–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almagro Armenteros, J.J.; et al. SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat. Biotechnol. 2019, 37, 420–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, W.-X.; Pan, X.; Shen, H.-B. Signal-3L 3.0: Improving Signal Peptide Prediction through Combining Attention Deep Learning with Window-Based Scoring. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2020, 60, 3679–3686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; Von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden markov model: Application to complete genomes11Edited by F. Cohen. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hallgren, J.; et al. DeepTMHMM predicts alpha and beta transmembrane proteins using deep neural networks. bioRxiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.A.; Clamp, M.; Barton, G.J. Jalview Version 2—A multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chan, C.; et al. Structural basis of activity and allosteric control of diguanylate cyclase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2004, 101, 17084–17089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.W.; et al. Structural Insights into the Regulatory Mechanism of the Response Regulator RocR from Pseudomonas aeruginosa in Cyclic Di-GMP Signaling. J. Bacteriol. 2012, 194, 4837–4846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellini, D.; et al. Crystal structure of an HD-GYP domain cyclic-di- GMP phosphodiesterase reveals an enzyme with a novel trinuclear catalytic iron centre. Mol. Microbiol. 2014, 91, 26–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; Yuan, Z.; Gu, L. Structural basis for the regulation of chemotaxis by MapZ in the presence of c-di-GMP. Acta Crystallogr. Sect. Struct. Biol. 2017, 73, 683–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sheng, S.; et al. The MapZ-Mediated Methylation of Chemoreceptors Contributes to Pathogenicity of Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Front. Microbiol. 2019, 10, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shim, S.R.; Kim, S.-J.; Lee, J.; Rücker, G. Network meta-analysis: Application and practice using R software. Epidemiol. Health 2019, 41, e2019013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, M.; Ramos, M. BiocManager: Access the Bioconductor Project Package Repository. 1.30.25. 2018. [CrossRef]

- Gu, Z.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paradis, E.; Schliep, K. ape 5.0: An environment for modern phylogenetics and evolutionary analyses in R. Bioinformatics 2019, 35, 526–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inkscape Project. Inkscape. 2020. Available online: https://inkscape.org.

- Schrödinger, L.; DeLano, W. PyMOL. 2020. Available online: http://www.pymol.org/pymol.

- Meng, E.C.; et al. UCSF ChimeraX: Tools for structure building and analysis. Protein Sci. 2023, 32, e4792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasteva, P.V.; Giglio, K.M.; Sondermann, H. Sensing the messenger: The diverse ways that bacteria signal through c-di-GMP. Protein Sci. 2012, 21, 929–948. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nie, H.; et al. Phenotypic–genotypic analysis of GGDEF/EAL/HD-GYP domain-encoding genes in Pseudomonas putida. Environ. Microbiol. Rep. 2020, 12, 38–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, C.-Y.; et al. The structure and inhibition of a GGDEF diguanylate cyclase complexed with (c-di-GMP)2 at the active site. Acta Crystallogr. D Biol. Crystallogr. 2011, 67, 997–1008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Römling, U.; Liang, Z.-X.; Dow, J.M. Progress in Understanding the Molecular Basis Underlying Functional Diversification of Cyclic Dinucleotide Turnover Proteins. J. Bacteriol. 2017, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, F.; et al. YybT Is a Signaling Protein That Contains a Cyclic Dinucleotide Phosphodiesterase Domain and a GGDEF Domain with ATPase Activity. J. Biol. Chem. 2010, 285, 473–482. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, M.Y.; Chou, S.-H. Sequence Conservation, Domain Architectures, and Phylogenetic Distribution of the HD-GYP Type c-di-GMP Phosphodiesterases. J. Bacteriol. 2022, 204, e00561-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, A.J.; Ryjenkov, D.A.; Gomelsky, M. The Ubiquitous Protein Domain EAL Is a Cyclic Diguanylate-Specific Phosphodiesterase: Enzymatically Active and Inactive EAL Domains. J. Bacteriol. 2005, 187, 4774–4781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tischler, A.D.; Camilli, A. Cyclic diguanylate (c-di-GMP) regulates Vibrio cholerae biofilm formation. Mol. Microbiol. 2004, 53, 857–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römling, U.; Gomelsky, M.; Galperin, M.Y. C-di-GMP: The dawning of a novel bacterial signalling system. Mol. Microbiol. 2005, 57, 629–639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamayo, R.; Tischler, A.D.; Camilli, A. The EAL Domain Protein VieA Is a Cyclic Diguanylate Phosphodiesterase. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 33324–33330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heo, K.; et al. A pGpG-specific phosphodiesterase regulates cyclic di-GMP signaling in Vibrio cholerae. J. Biol. Chem. 2022, 298, 101626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rao, F.; et al. The Functional Role of a Conserved Loop in EAL Domain-Based Cyclic di-GMP-Specific Phosphodiesterase. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 4722–4731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Römling, U. Rationalizing the Evolution of EAL Domain-Based Cyclic di-GMP-Specific Phosphodiesterases. J. Bacteriol. 2009, 191, 4697–4700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchigvintsev, A.; et al. Structural Insight into the Mechanism of c-di-GMP Hydrolysis by EAL Domain Phosphodiesterases. J. Mol. Biol. 2010, 402, 524–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barends, T.R.M.; et al. Structure and mechanism of a bacterial light-regulated cyclic nucleotide phosphodiesterase. Nature 2009, 459, 1015–1018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarutina, M.; Ryjenkov, D.A.; Gomelsky, M. An Unorthodox Bacteriophytochrome from Rhodobacter sphaeroides Involved in Turnover of the Second Messenger c-di-GMP. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 34751–34758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, J.G.; Murphy, C.N.; Sippy, J.; Johnson, T.J.; Clegg, S. Type 3 Fimbriae and Biofilm Formation Are Regulated by the Transcriptional Regulators MrkHI in Klebsiella pneumoniae. J. Bacteriol. 2011, 193, 3453–3460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, S.; Pandelia, M.-E. HD-[HD-GYP] Phosphodiesterases: Activities and Evolutionary Diversification within the HD-GYP Family. Biochemistry 2020, 59, 2340–2350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; et al. Cryo-EM structure of trimeric Mycobacterium smegmatis succinate dehydrogenase with a membrane-anchor SdhF. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 4245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, D.; et al. Pseudomonas aeruginosa SutA wedges RNAP lobe domain open to facilitate promoter DNA unwinding. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 4204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, Z.; Gao, H.; Bai, X.; Yu, H. Cryo-EM structure of the human cohesin-NIPBL-DNA complex. Science 2020, 368, 1454–1459. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tian, T.; et al. Structural insights into human CCAN complex assembled onto DNA. Cell Discov. 2022, 8, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klein, B.J.; et al. RNA polymerase and transcription elongation factor Spt4/5 complex structure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2011, 108, 546–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keidel, A.; et al. Concerted structural rearrangements enable RNA channeling into the cytoplasmic Ski238-Ski7-exosome assembly. Mol. Cell 2023, 83, 4093–4105.e7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vanden Broeck, A.; Klinge, S. Principles of human pre-60 S biogenesis. Science 2023, 381, eadh3892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohanty, S.; et al. Structural Basis for a Unique ATP Synthase Core Complex from Nanoarcheaum equitans. J. Biol. Chem. 2015, 290, 27280–27296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bian, C.; et al. Sgf29 binds histone H3K4me2/3 and is required for SAGA complex recruitment and histone H3 acetylation: Sgf29 functions as an H3K4me2/3 binder in SAGA. EMBO J. 2011, 30, 2829–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, D.; et al. Crystal structure of a novel Sm-like protein of putative cyanophage origin at 2.60 Å resolution. Proteins Struct. Funct. Bioinforma. 2009, 75, 296–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tobiasson, V.; Berzina, I.; Amunts, A. Structure of a mitochondrial ribosome with fragmented rRNA in complex with membrane-targeting elements. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 6132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, M.Y.; Chou, S.-H. Structural Conservation and Diversity of PilZ-Related Domains. J. Bacteriol. 2020, 202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amikam, D.; Galperin, M.Y. PilZ domain is part of the bacterial c-di-GMP binding protein. Bioinformatics 2006, 22, 3–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Tsai, B.; Li, N.; Gao, N. Structural remodeling of ribosome associated Hsp40-Hsp70 chaperones during co-translational folding. Nat. Commun. 2022, 13, 3410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koplin, A.; et al. A dual function for chaperones SSB–RAC and the NAC nascent polypeptide–associated complex on ribosomes. J. Cell Biol. 2010, 189, 57–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peisker, K.; et al. Ribosome-associated Complex Binds to Ribosomes in Close Proximity of Rpl31 at the Exit of the Polypeptide Tunnel in Yeast. Mol. Biol. Cell 2008, 19, 5279–5288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pichlo, C.; et al. Molecular determinants of the mechanism and substrate specificity of Clostridium difficile proline-proline endopeptidase-1. J. Biol. Chem. 2019, 294, 11525–11535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pannifer, A.D.; et al. Crystal structure of the anthrax lethal factor. Nature 2001, 414, 229–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Visschedyk, D.; et al. Certhrax Toxin, an Anthrax-related ADP-ribosyltransferase from Bacillus cereus. J. Biol. Chem. 2012, 287, 41089–41102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scheithauer, L.; et al. Zinc metalloprotease ProA of Legionella pneumophila increases alveolar septal thickness in human lung tissue explants by collagen IV degradation. Cell. Microbiol. 2021, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, Y.; Zhukovskaya, N.L.; Guo, Q.; Florián, J.; Tang, W.-J. Calcium-independent calmodulin binding and two-metal–ion catalytic mechanism of anthrax edema factor. EMBO J. 2005, 24, 929–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pei, J.; Mitchell, D.A.; Dixon, J.E.; Grishin, N.V. Expansion of Type II CAAX Proteases Reveals Evolutionary Origin of γ-Secretase Subunit APH-1. J. Mol. Biol. 2011, 410, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jones, C.J.; et al. C-di-GMP Regulates Motile to Sessile Transition by Modulating MshA Pili Biogenesis and Near-Surface Motility Behavior in Vibrio cholerae. PLOS Pathog. 2015, 11, e1005068. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Structure and Function of the XpsE N-Terminal Domain, an Essential Component of the Xanthomonas campestris Type II Secretion System. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 42356–42363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christen, M.; Christen, B.; Folcher, M.; Schauerte, A.; Jenal, U. Identification and Characterization of a Cyclic di-GMP-specific Phosphodiesterase and Its Allosteric Control by GTP. J. Biol. Chem. 2005, 280, 30829–30837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenal, U.; Reinders, A.; Lori, C. Cyclic di-GMP: Second messenger extraordinaire. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2017, 15, 271–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martín-Rodríguez, A.J.; et al. Comparative Genomics of Cyclic di-GMP Metabolism and Chemosensory Pathways in Shewanella algae Strains: Novel Bacterial Sensory Domains and Functional Insights into Lifestyle Regulation. mSystems 2022, 7, e01518-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, M.Y. A census of membrane-bound and intracellular signal transduction proteins in bacteria: Bacterial IQ, extroverts and introverts. BMC Microbiol. 2005, 5, 35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galperin, M.Y.; Higdon, R.; Kolker, E. Interplay of heritage and habitat in the distribution of bacterial signal transduction systems. Mol. Biosyst. 2010, 6, 721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Römling, U.; Cao, L.-Y.; Bai, F.-W. Evolution of cyclic di-GMP signalling on a short and long term time scale. Microbiology 2023, 169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, F.; Jeong, G.-J.; Tabassum, N.; Kim, Y.-M. Functional diversity of c-di-GMP receptors in prokaryotic and eukaryotic systems. Cell Commun. Signal. 2023, 21, 259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holland, L.M.; et al. A Staphylococcal GGDEF Domain Protein Regulates Biofilm Formation Independently of Cyclic Dimeric GMP. J. Bacteriol. 2008, 190, 5178–5189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, M.-L.; et al. Global Transcriptional Repression of Diguanylate Cyclases by MucR1 Is Essential for Sinorhizobium -Soybean Symbiosis. mBio 2021, 12, e01192-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bobrov, A.G.; et al. Systematic analysis of cyclic di-GMP signalling enzymes and their role in biofilm formation and virulence in Yersinia pestis. Mol. Microbiol. 2011, 79, 533–551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guzzo, C.R.; Salinas, R.K.; Andrade, M.O.; Farah, C.S. PILZ Protein Structure and Interactions with PILB and the FIMX EAL Domain: Implications for Control of Type IV Pilus Biogenesis. J. Mol. Biol. 2009, 393, 848–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bordeleau, E.; Fortier, L.-C.; Malouin, F.; Burrus, V. c-di-GMP Turn-Over in Clostridium difficile Is Controlled by a Plethora of Diguanylate Cyclases and Phosphodiesterases. PLoS Genet. 2011, 7, e1002039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aravind, L.; Koonin, E.V. The HD domain defines a new superfamily of metal-dependent phosphohydrolases. Trends Biochem. Sci. 1998, 23, 469–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lovering, A.L.; Capeness, M.J.; Lambert, C.; Hobley, L.; Sockett, R.E. The Structure of an Unconventional HD-GYP Protein from Bdellovibrio Reveals the Roles of Conserved Residues in this Class of Cyclic-di-GMP Phosphodiesterases. mBio 2011, 2, e00163-11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McKee, R.W.; Kariisa, A.; Mudrak, B.; Whitaker, C.; Tamayo, R. A systematic analysis of the in vitro and in vivo functions of the HD-GYP domain proteins of Vibrio cholerae. BMC Microbiol. 2014, 14, 272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stelitano, V.; et al. C-di-GMP Hydrolysis by Pseudomonas aeruginosa HD-GYP Phosphodiesterases: Analysis of the Reaction Mechanism and Novel Roles for pGpG. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e74920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Remminghorst, U.; Rehm, B.H.A. Alg44, a unique protein required for alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. FEBS Lett. 2006, 580, 3883–3888. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradali, M.F.; Donati, I.; Sims, I.M.; Ghods, S.; Rehm, B.H.A. Alginate Polymerization and Modification Are Linked in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. mBio 2015, 6, e00453-15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Christen, M.; et al. DgrA is a member of a new family of cyclic diguanosine monophosphate receptors and controls flagellar motor function in Caulobacter crescentus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2007, 104, 4112–4117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.-J.; et al. Structural insights into the mechanism of c-di-GMP–bound YcgR regulating flagellar motility in Escherichia coli. J. Biol. Chem. 2020, 295, 808–821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; et al. Flagellar brake protein YcgR interacts with motor proteins MotA and FliG to regulate the flagellar rotation speed and direction. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1159974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randall, T.E.; et al. Sensory Perception in Bacterial Cyclic Diguanylate Signal Transduction. J. Bacteriol. 2022, 204, e00433-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; et al. Tetrameric PilZ protein stabilizes stator ring in complex flagellar motor and is required for motility in Campylobacter jejuni. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2025, 122, e2412594121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilksch, J.J.; et al. MrkH, a Novel c-di-GMP-Dependent Transcriptional Activator, Controls Klebsiella pneumoniae Biofilm Formation by Regulating Type 3 Fimbriae Expression. PLoS Pathog. 2011, 7, e1002204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schumacher, M.A.; Zeng, W. Structures of the activator of K. pneumonia biofilm formation, MrkH, indicates PilZ domains involved in c-di-GMP and DNA binding. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2016, 113, 10067–10072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devkota, S.R.; Kwon, E.; Ha, S.C.; Chang, H.W.; Kim, D.Y. Structural insights into the regulation of Bacillus subtilis SigW activity by anti-sigma RsiW. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0174284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellermeier, C.D.; Losick, R. Evidence for a novel protease governing regulated intramembrane proteolysis and resistance to antimicrobial peptides in Bacillus subtilis. Genes Dev. 2006, 20, 1911–1922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heinrich, J.; Hein, K.; Wiegert, T. Two proteolytic modules are involved in regulated intramembrane proteolysis of Bacillus subtilis RsiW. Mol. Microbiol. 2009, 74, 1412–1426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pannullo, A.G.; Ellermeier, C.D. Activation of the Extracytoplasmic Function σ Factor σV in Clostridioides difficile Requires Regulated Intramembrane Proteolysis of the Anti-σ Factor RsiV. mSphere 2022, 7, e00092–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Helmann, J.D. Bacillus subtilis extracytoplasmic function (ECF) sigma factors and defense of the cell envelope. Curr. Opin. Microbiol. 2016, 30, 122–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- De Bruijn, F.J. Stress and Environmental Regulation of Gene Expression and Adaptation in Bacteria; John Wiley & Sons, Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Ho, T.D.; Ellermeier, C.D. PrsW Is Required for Colonization, Resistance to Antimicrobial Peptides, and Expression of Extracytoplasmic Function σ Factors in Clostridium difficile. Infect. Immun. 2011, 79, 3229–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merighi, M.; Lee, V.T.; Hyodo, M.; Hayakawa, Y.; Lory, S. The second messenger bis-(3′-5′)-cyclic-GMP and its PilZ domain-containing receptor Alg44 are required for alginate biosynthesis in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol. Microbiol. 2007, 65, 876–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malmström, J.; et al. Proteome-wide cellular protein concentrations of the human pathogen Leptospira interrogans. Nature 2009, 460, 762–765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).