Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Background on Industry 4.0 Tools Applied to Maintenance

- -

- In the mid-1700s, the steam engine enabled the implementation of new systems capable of improving and mechanizing the productivity of conventional processes. This marked the first industrial revolution.

- -

- Around 1870, with the widespread use of electricity, the concept of mass production emerged. At the same time, the combustion engine began to be used.

- -

- Around the 1970s, the digital era began. Its objective was to increase automation by leveraging information technology.

- -

- The fourth and most recent industrial revolution is based on currently available technologies; it does not have a precise official start date, as its development is still ongoing.

1.1. The Metaverse as an Expansion of Industry 4.0 in Maintenance

- -

- Interaction with digital twins: The integration of IoT sensors and big data analytics platforms enables the construction of virtual models that accurately reflect the operational behavior of assets. This facilitates early fault detection and data-driven decision-making [15].

- -

- Scenario simulation and technical training: Through immersive environments, operators can rehearse maintenance procedures under safe conditions, reducing human error, shortening training times, and improving operational understanding of systems [16].

- -

- Remote collaboration and field assistance: Augmented reality interfaces enable experts to remotely guide the execution of critical tasks, improving intervention accuracy and reducing asset downtime [15].

- -

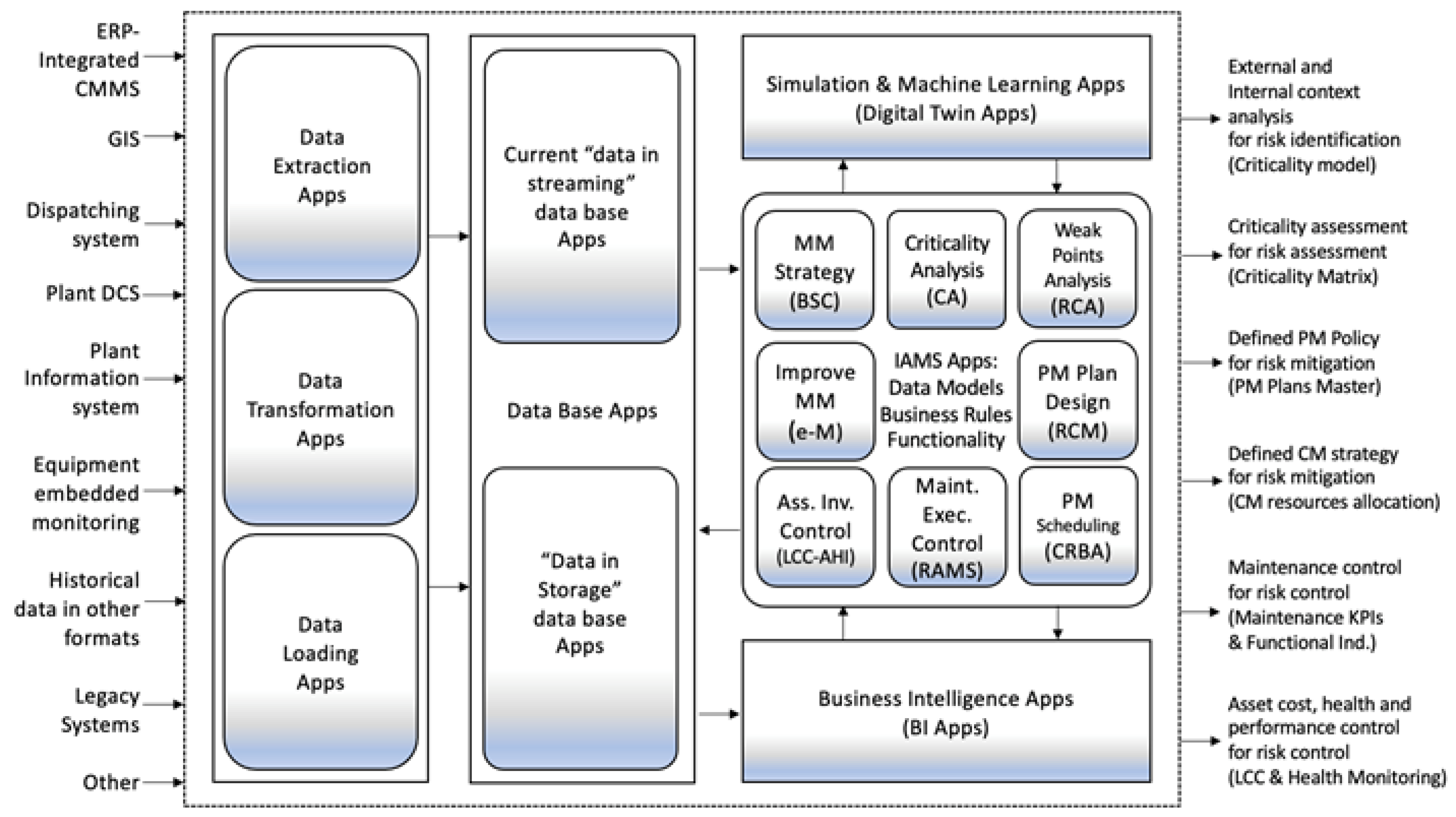

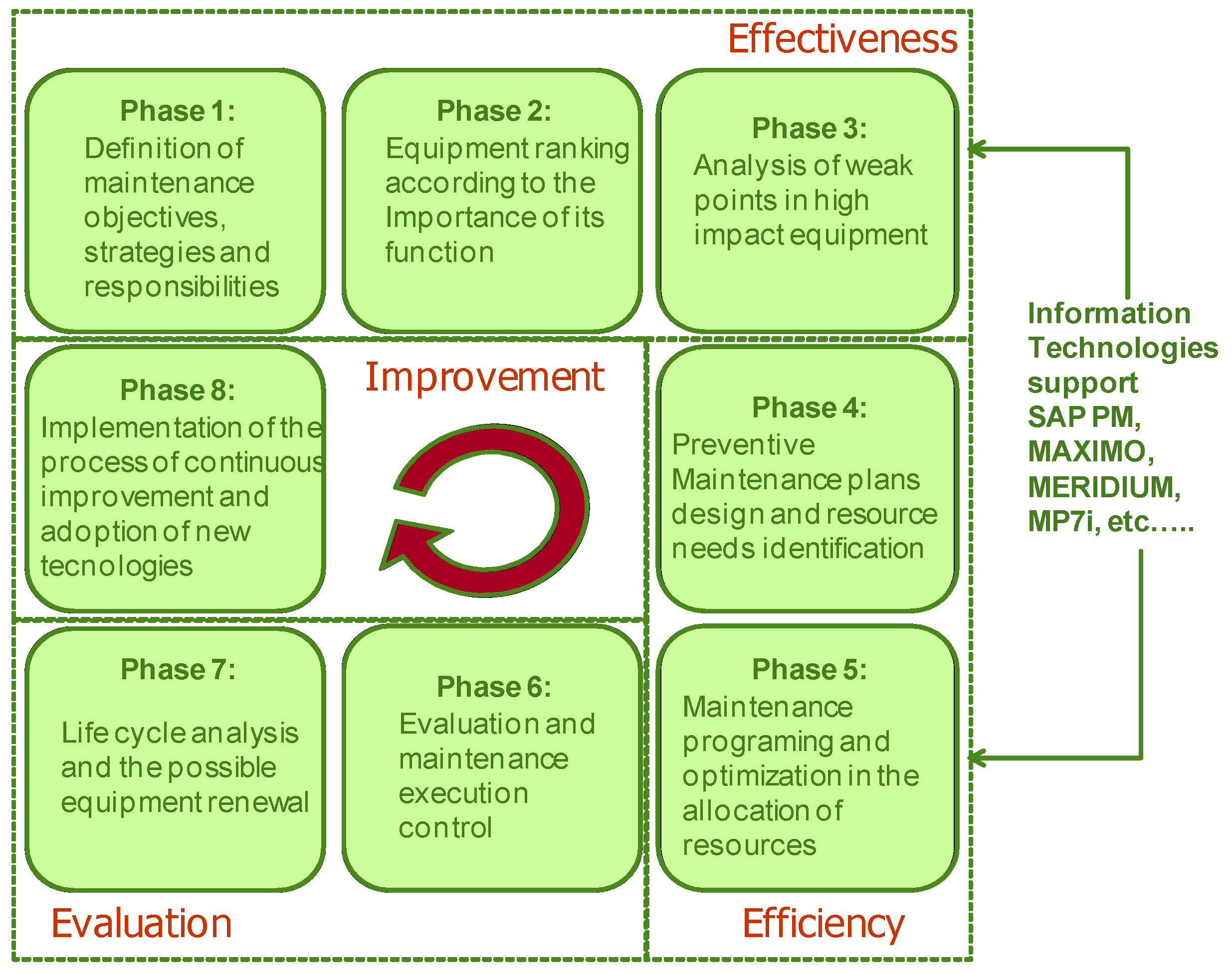

2. Comprehensive Application of the Maintenance Management Model (MMM)

- -

- Phase 1. Techniques for defining a maintenance management strategy. To ensure that maintenance operational objectives and strategies are not misaligned with overall business goals [19], techniques such as the Balanced Scorecard (BSC) can be introduced and implemented in the maintenance area [18]. The BSC is customized for each organization and enables the creation of key performance indicators (KPIs) to measure maintenance performance, aligned with strategic objectives [19]. Unlike conventional control-oriented measures, the BSC centers its analysis on corporate strategy and vision, emphasizing the achievement of performance goals. These goals are established through a participative process involving internal and external stakeholders in the maintenance organization, company leadership, key operational personnel, and end users. As a result, maintenance performance measures are directly linked to the overall success of the organization.

- -

- Phase 2. Techniques for ranking production assets. Once maintenance objectives and strategies are defined, various qualitative and quantitative techniques are available to systematically classify assets based on their criticality for achieving business objectives. Many quantitative approaches employ variations of probabilistic risk assessment (PRA) or generate probabilistic risk indices (PRI) for each asset [17]. Assets with higher indices are prioritized. In cases where historical data is unavailable, qualitative techniques may be applied to ensure effective initial decision-making. After asset prioritization, a clear maintenance strategy must be defined for each category, to be refined over time.

- -

- Phase 3. Tools for eliminating weak points in high-impact equipment or systems. In critical assets, it is advisable to identify and eliminate chronic, recurring failures before developing maintenance plans. Doing so can yield an early return on investment. One of the most widely used techniques for this purpose is Root Cause Analysis (RCA) [17], which identifies the physical, human, and latent causes of failures. Physical causes refer to the technical explanation for the failure, human causes involve errors or omissions that lead to failure, and latent causes relate to organizational or management deficiencies that enable those errors to persist. Addressing latent causes is typically the main focus of this phase.

- -

- Phase 4. Support for defining an effective preventive maintenance plan. Designing a preventive maintenance plan for a system requires identifying its functions and potential failure modes, and establishing tasks that ensure safety and cost-effectiveness. A structured methodology such as Reliability Centered Maintenance (RCM) [17] is commonly used to achieve this objective.

- -

- Phase 5. Optimization techniques for improving maintenance programs. Maintenance plans and programs can be optimized to improve the effectiveness and efficiency of the initial design. Optimization models vary depending on the analysis time horizon. Long-term models address maintenance capacity, spare parts inventory, and task intervals. Medium-term models focus on optimizing scheduled shutdowns, while short-term models improve resource allocation and control. Both analytical and empirical approaches are employed, often requiring simplifications to manage complexity [17,18].

- -

- Phase 6. Monitoring and control of maintenance operations. Once maintenance activities are designed, planned, and scheduled, their execution must be monitored, and deviations controlled to meet business objectives and KPI targets. Many high-level KPIs are built from technical and economic sub-indicators, making it essential to capture accurate and aggregated maintenance data.

- -

-

Phase 7. Lifecycle cost analysis and control. This phase evaluates the total cost of an asset throughout its lifecycle, including planning, R&D, production, operation, maintenance, and disposal. Lifecycle cost analysis depends heavily on reliability data such as failure rates, repair times, and spare part costs. It supports decisions about new equipment acquisition or replacement and offers three major benefits [20]:

- ○

- All costs associated with an asset become visible.

- ○

- It enables cross-functional analysis, e.g., how low R&D investment may increase future maintenance costs.

- ○

- It allows management to make accurate forecasts.

- -

- Phase 8. Techniques for continuous improvement in maintenance. Continuous improvement (CI) in maintenance is possible through emerging technologies in high-impact areas identified in earlier phases. Concepts such as Maintenance 4.0, e-maintenance, and e-manufacturing are key elements of Industry 4.0, which leverages ICT to create collaborative, multi-user corporate environments [4,20]. Maintenance 4.0 refers to a maintenance support system that integrates the resources, services, and management needed to enable proactive, data-driven decision-making. This support includes ICT, web-based, wireless, infotronic technologies, and “e-maintenance” functions such as e-monitoring, e-diagnosis, and e-prognosis. Additionally, the active participation of maintenance personnel is critical to success. While high levels of knowledge, training, and expertise are required, the inclusion of simple, operator-driven tasks is essential to achieving high-quality maintenance and overall equipment effectiveness.

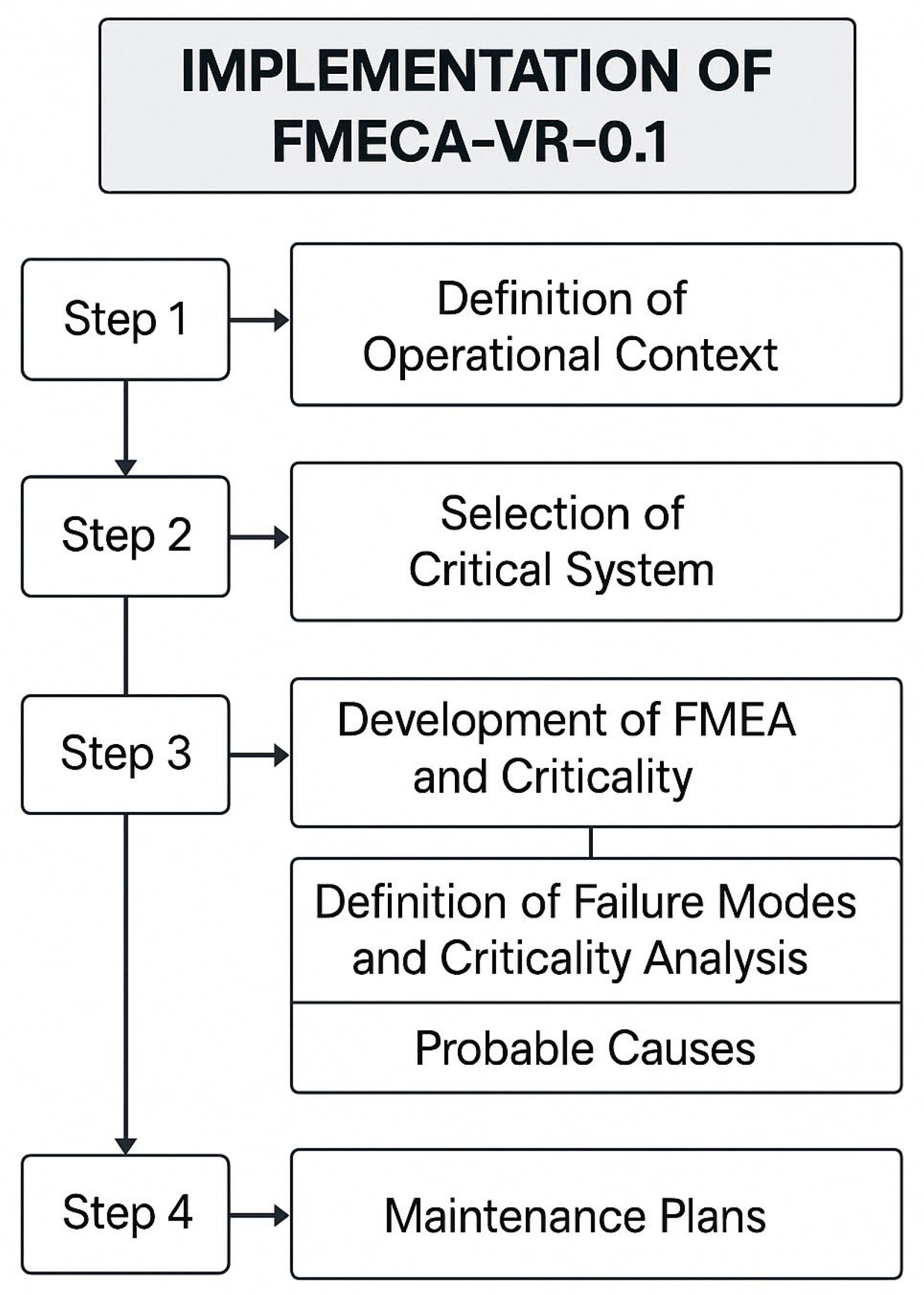

3. Methodological Framework of the FMECA-VR-0.1 Tool

- -

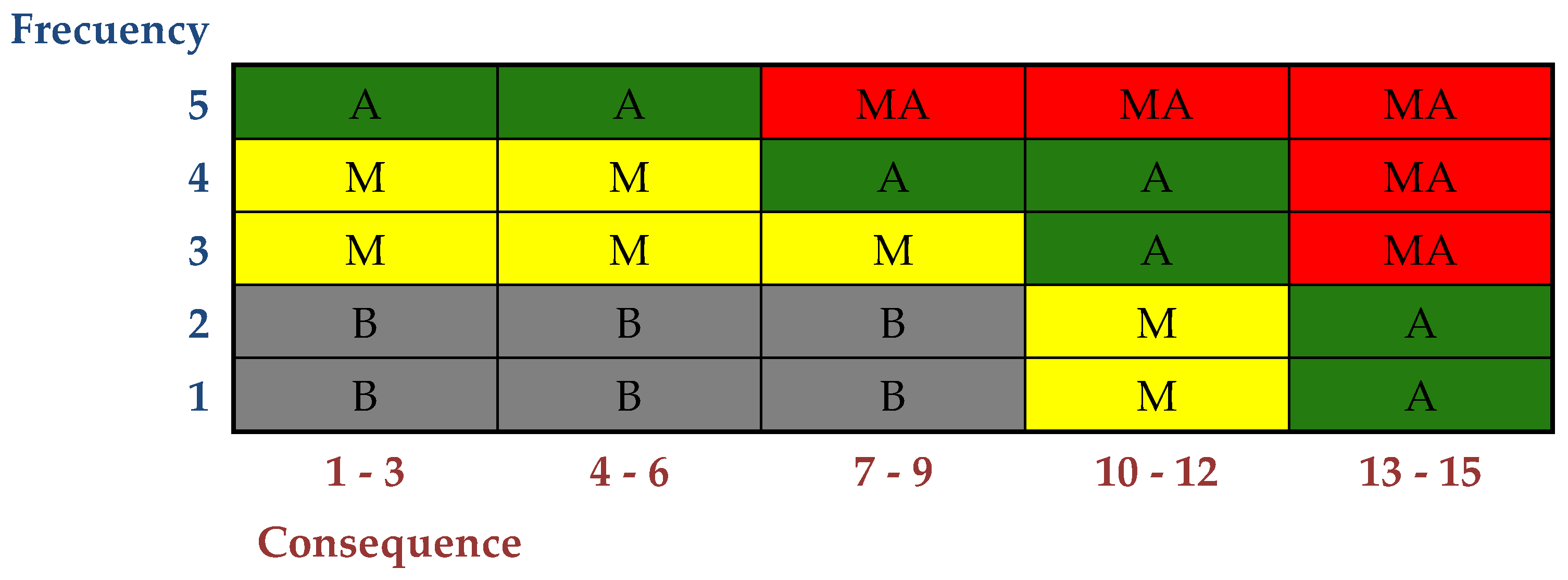

- Stages 1 and 2 correspond to the development of the operational context and the criticality matrix (linked to Phase 2 of the MMM).

- -

- Stages 3 and 4 correspond to the definition of failure modes, effects, and criticality (linked to Phase 4 of the MMM).

- -

- Stage 5 corresponds to the development of maintenance strategies (linked to Phases 4 and 5 of the MMM).

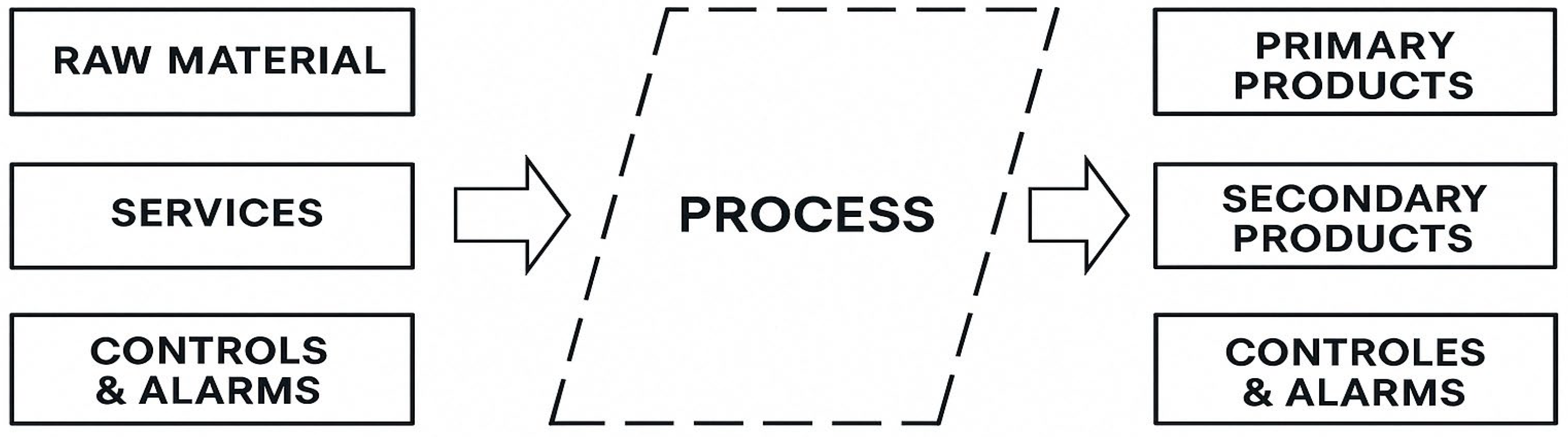

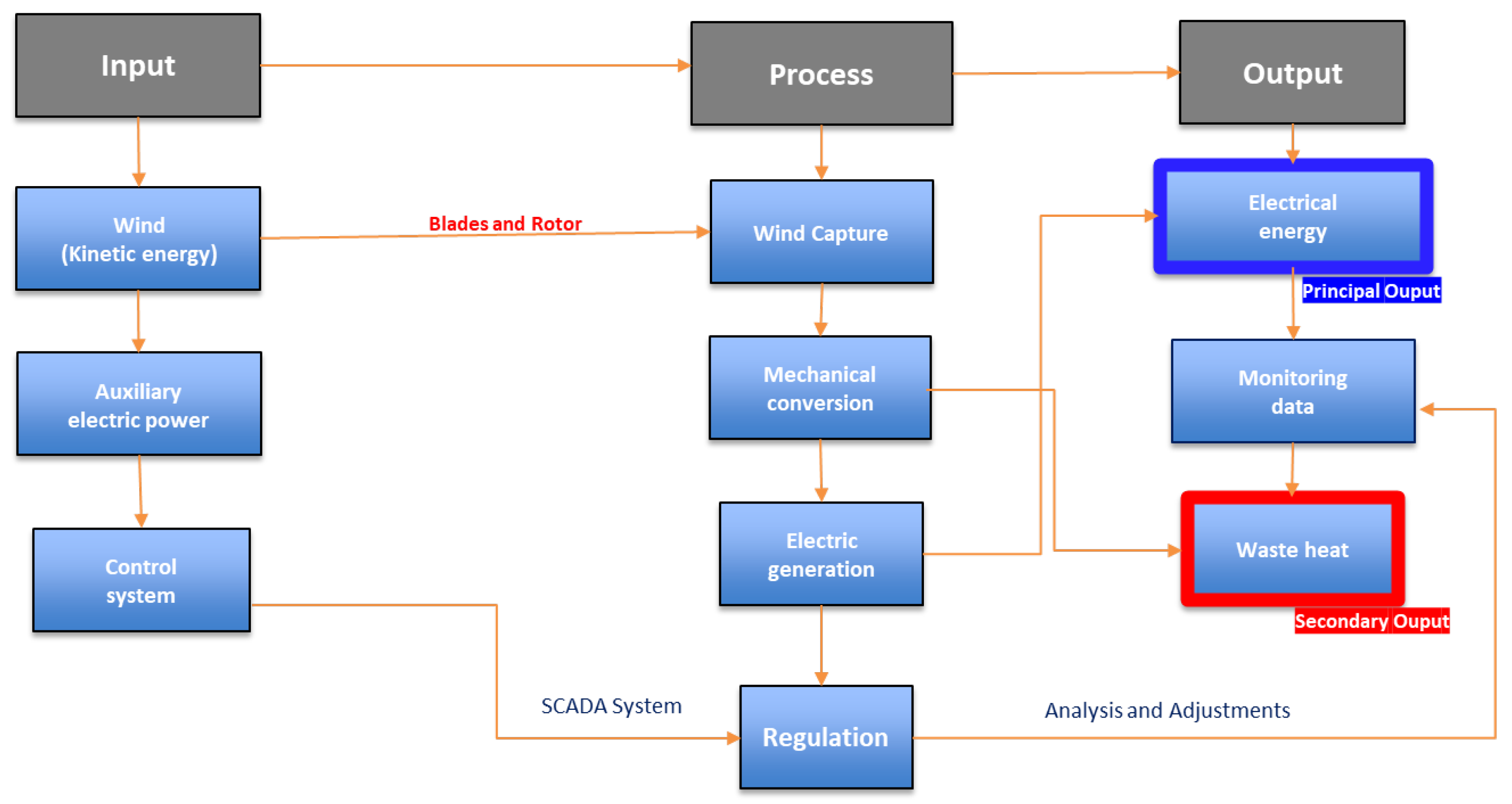

3.1. Stage 1. Operational Context

- -

- Operational Summary: Purpose of the system, equipment involved, processes, safety devices, and environmental objectives.

- -

- Personnel: Definition of shifts, operations, and quality parameters.

- -

- Process Breakdown: Structuring of the process into systems, definition of boundaries, and listing of components.

- -

- Operational profile.

- -

- Operating environment.

- -

- Quality/availability of required inputs (fuel, air, etc.).

- -

- Alarms and monitoring.

- -

- Spare parts policies, resources, and logistics.

- -

- P&IDs (Piping and Instrumentation Diagrams) of the system.}

- -

- System schematics and/or block diagrams, typically developed from the P&IDs.

- -

- Raw materials: Resources directly processed or transformed by the system or equipment (e.g., gas, crude oil, wood).

- -

- Services: Resources used by the process to transform raw materials (e.g., electricity, water, steam).

- -

- Controls: Inputs related to control systems and their effects on the equipment or processes. These are usually not recorded as separate functions, as their failure is generally associated with a loss of output signal at some point in the process.

- -

- Primary products: Represent the main purpose of the system, generally defined by production rate and quality standards.

- -

- Secondary products: Derived from primary functions performed by the system. Loss of secondary products can often lead to the failure of primary functions and may have catastrophic consequences.

- -

- Controls and alarms: Related to the system’s protection and control functions.

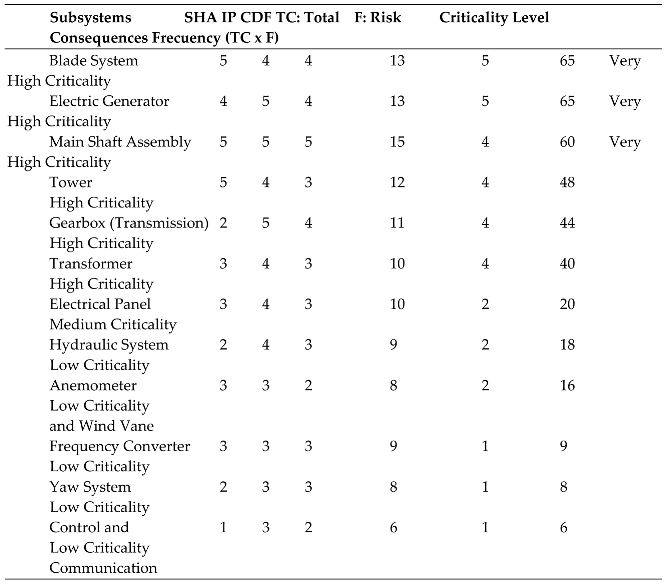

3.2. Stage 2. Equipment-Level Criticality Analysis

- -

- Define the scope and purpose of the analysis.

- -

- Establish importance criteria, such as safety, environment, production, cost, failure frequency, and repair time.

- -

- Select or develop a method to rank systems/equipment.

- -

- FF = Failure frequency per equipment (number of failures in a given time period)

- -

- C = Consequences of failures related to safety, environment, quality, production, etc.

- -

- SHE = Safety, Health and Environmental Impact

- -

- IP = Impact of Production

- -

- CDF = Costs Direct of Failure

- -

- Failure Frequency (FF)

- -

- Failure Consequences (C)

- -

- Criticality Levels by Equipment (Based on QRCM – Figure 5):

3.3. Stage 3. Failure Modes, Effects, and Criticality Analysis (FMECA)

3.3.1. Stage 3.1. Failure Modes

- -

- Generic lists of failure modes.

- -

- Operations and/or maintenance personnel with extensive experience with the asset.

- -

- Existing technical records and maintenance histories.

- -

- Asset manufacturers and suppliers.

- -

- Other users operating the same type of asset.

- -

- Burned-out electric motor (detail level: equipment)

- -

- Fractured impeller shaft (detail level: component)

- -

- Impeller jammed due to foreign object (detail level: component)

- -

- Completely blocked suction line (detail level: component)

- -

- Worn mechanical seal (detail level: component)

- -

- Damaged piston ring in hydraulic cylinder (detail level: component)

3.3.2. Stage 3.2. Effects and Criticality of Failure Modes

- -

- What evidence confirms that the failure has occurred?

- -

- How does it affect safety and the environment?

- -

- How does it impact production or operations?

- -

- What are the operational consequences?

- -

- Is it necessary to shut down the process?

- -

- Is there an impact on quality? If so, how much?

- -

- Is there an impact on customer service?

- -

- Does it cause damage to other systems?

- -

- How much time is required to repair the failure (corrective actions)?

- -

- What is the economic loss caused by the failure (direct costs, production impact, environmental and safety costs, etc.)?

- -

-

Failure Mode:Damaged piston rings in hydraulic cylinder

- -

-

Effects of Failure Mode:

- ○

- Visible/Not visible: Yes. No impact on safety or environment.

- ○

- Operational effects: The engine crankcase depressurizes, cylinder compression drops, oil wets the spark plug, smoke is observed in the exhaust, compression capacity is lost, and engine RPMs decrease.

- ○

- Corrective actions: Shut down the engine, depressurize the system, rotate the engine, position the connecting rods, secure the flywheel, loosen connecting rod bolts, remove the piston, inspect the rings, and replace them if necessary. Required personnel: 4 mechanics. Repair time: 16 hours/failure.

- ○

- Production impact: USD 120,000/hour. Total impact per failure: USD 1,920,000.

- -

- FF = Frequency of the failure mode (number of failures in a given time period)

- -

- C = Consequences of the failure mode in terms of safety, environment, quality, production, etc.

- -

- SHE = Impact on Safety and the Environment

- -

- IP = Impact on Production

- -

- CDF = Direct Failure Costs

- -

- Criticality Levels by Failure Mode (based on QRCM – Figure 5):

3.3.3. Stage 3.3. Probable Causes

- -

- Failure Mode: Damaged piston rings in hydraulic cylinder

- -

- Probable Cause: Accelerated wear due to increased temperature

3.4. Stage 4. Maintenance Plans

- -

- Preventive (proactive) maintenance

- -

- Corrective (reactive) maintenance, applied only when no effective preventive alternative exists.

3.4.1. Preventive (Proactive) Maintenance Activities

- -

- Condition-Based Maintenance (CBM)

- -

- Overhaul (Reconditioning)

- -

- Scheduled Replacement

- -

- Hidden Failure Detection

3.4.2. Corrective (Reactive) Maintenance Activities

- -

- Redesign

- -

- Run-to-Failure (Unscheduled Maintenance)

4. Practical Application of the FMECA–VR 0.1 Tool in the Renewable Energy Sector

4.1. Stage 1: Definition of the Operational Context

- -

- Reference Data:

- -

- Controllers and Alarms:

- -

- Blades: Capture the wind’s kinetic energy and convert it into mechanical rotational energy.

- -

- Main Shaft Assembly: Transmits the rotational mechanical energy from the blades to the generator.

- -

- Gearbox (Multiplier): Increases the rotational speed of the main shaft.

- -

- Doubly-Fed Induction Generator (DFIG): Converts the rotational mechanical energy—transmitted through the shaft system—into electrical energy.

- -

- Frequency Converter: Manages and adapts the electrical energy generated by the DFIG to match grid standards in frequency and voltage.

- -

- Transformer: Adjusts or steps up the voltage of the generated electricity for safe and efficient transmission to the grid.

- -

- Electrical Panel: Also known as the electrical control cabinet, it manages, distributes, and protects the turbine’s electrical systems.

- -

- Yaw System: Orients the nacelle and blades toward the wind direction.

- -

- Minimum Operating Wind Speed:

- -

- Power Growth:

- -

- Operational Stability:

- -

- Safety Shutdown:

- -

- INPUT: The necessary resources for wind turbine operation include:

- -

- PROCESS: The wind turbine converts kinetic wind energy into electrical energy through the following steps:

- -

- OUTPUT: Products and by-products generated by the wind turbine include:

4.2. Stage 2: Selection of the Critical System

- -

- Subsystems with Very High Criticality: 25% of total

- -

- Subsystems with High Criticality: 25% of total

- -

- Subsystems with Medium Criticality: 42% of total

- -

- Subsystems with Low Criticality: 8% of total

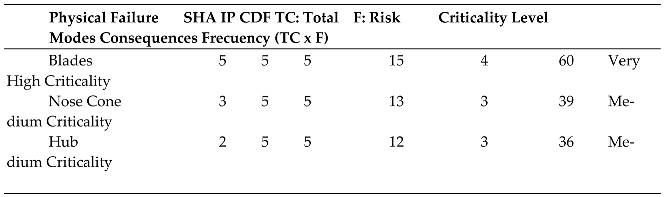

4.3. Stage 3: Development of FMECA and Criticality Analysis

4.3.1. Definition of Failure Modes and Criticality Analysis

- -

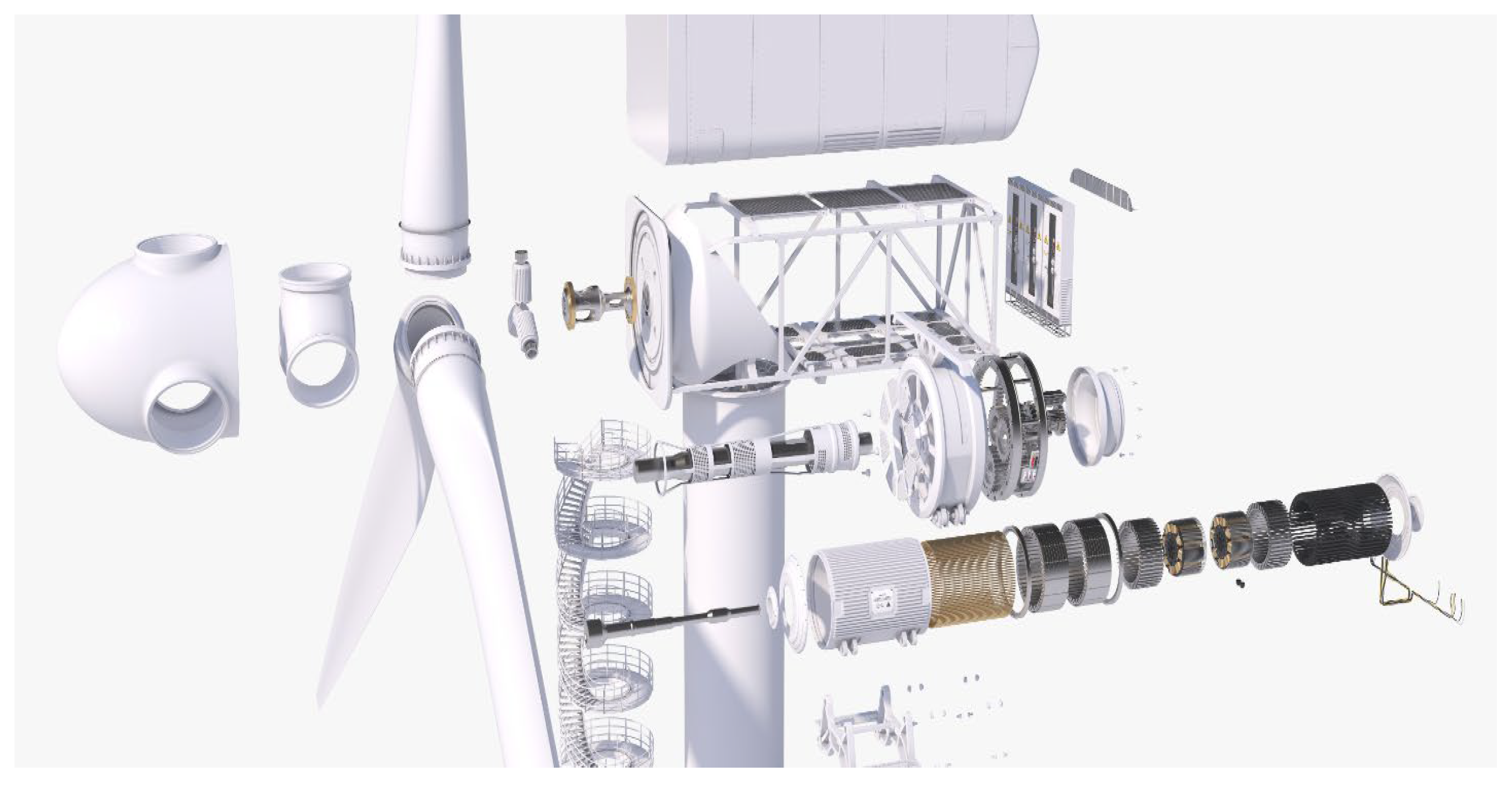

- Blade Damage: Modern wind turbines typically use three blades to ensure lower oscillations and better balance of gyroscopic forces. These blades are mainly made of lightweight and highly durable materials such as carbon fiber and fiberglass combined with epoxy resin. They can reach lengths of up to 50 meters and rotate at speeds ranging from 10 to 60 RPM. For large-scale turbines, the most common operating speeds are between 10 and 20 RPM. The blades are mounted on the turbine hub [24].

- -

- Hub Damage: The hub connects the blades and transmits the captured wind energy from the rotor to the gearbox. It is generally a hollow metal structure that acts as a rigid central piece [24].

- -

- Nose Cone Issues: The nose cone is a conical structure that faces the wind and directs it toward the drivetrain. Its aerodynamic shape helps prevent turbulence and protects the wind turbine from potential damage [24].

4.3.2. Definition of Probable Causes

4.4. Stage 4: Maintenance Plans

- -

- Select the blade subsystem for the development of action plans related to its physical failure modes.

- -

- Identify the three physical failure modes and their previously assigned criticality levels.

- -

- Define the probable causes for each failure mode.

- -

- Specify the maintenance tasks associated with each failure mode.

- -

- Estimate the execution frequency for each task.

- -

- Assign a responsible specialist for each task.

- -

- Estimate the annual cost of each maintenance plan.

- -

- Estimate the annual maintenance hours for each task.

5. Development of the Metaverse-Based Platform Prototype: FMECA-VR-0.1

5.1. Functional Requirements

- -

- The system will allow users to visualize the Valle de los Vientos Wind Farm, located in the Calama region.

- -

- The system will support manipulation and visualization of a 3D model of the VESTAS V100–2.0 MW wind turbine.

- -

- The system will provide access to documents related to the FMEA table and criticality assessment for the blade subsystem.

- -

- The system will provide access to documents related to the action plan for physical failure modes of the turbine blades.

- -

- The system will enable visualization of elements related to the wind turbine’s subsystems.

5.2. Technical Requirements

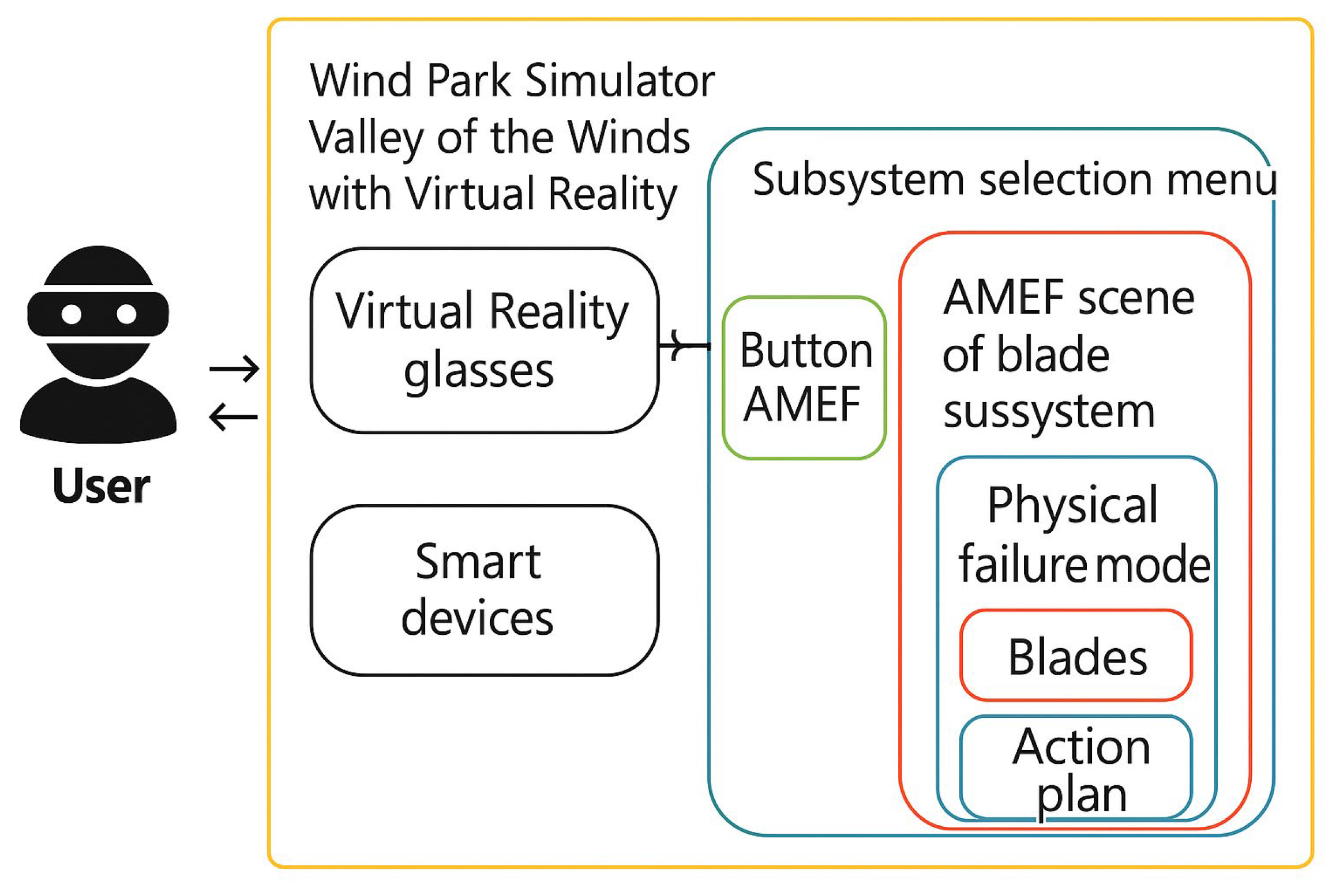

5.3. System Architecture

- -

-

Inputs: The Oculus Quest 2 system provides the following inputs to the immersive application:

- ▪

- VIRTUAL REALITY Headset: Allows the user to visualize virtual reality environments, which is fundamental to achieving an immersive experience.

- ▪

- Joysticks: Composed of two handheld controllers (one in each hand), these allow the user to interact with objects and elements in the virtual environment. These controls provide an intuitive way to manipulate and navigate the platform.

- -

-

Outputs: The system outputs correspond to the visual elements generated and displayed through the VIRTUAL REALITY headset. During the immersive session, the user will be able to view components, diagrams, and relevant information panels within the virtual space.

- ▪

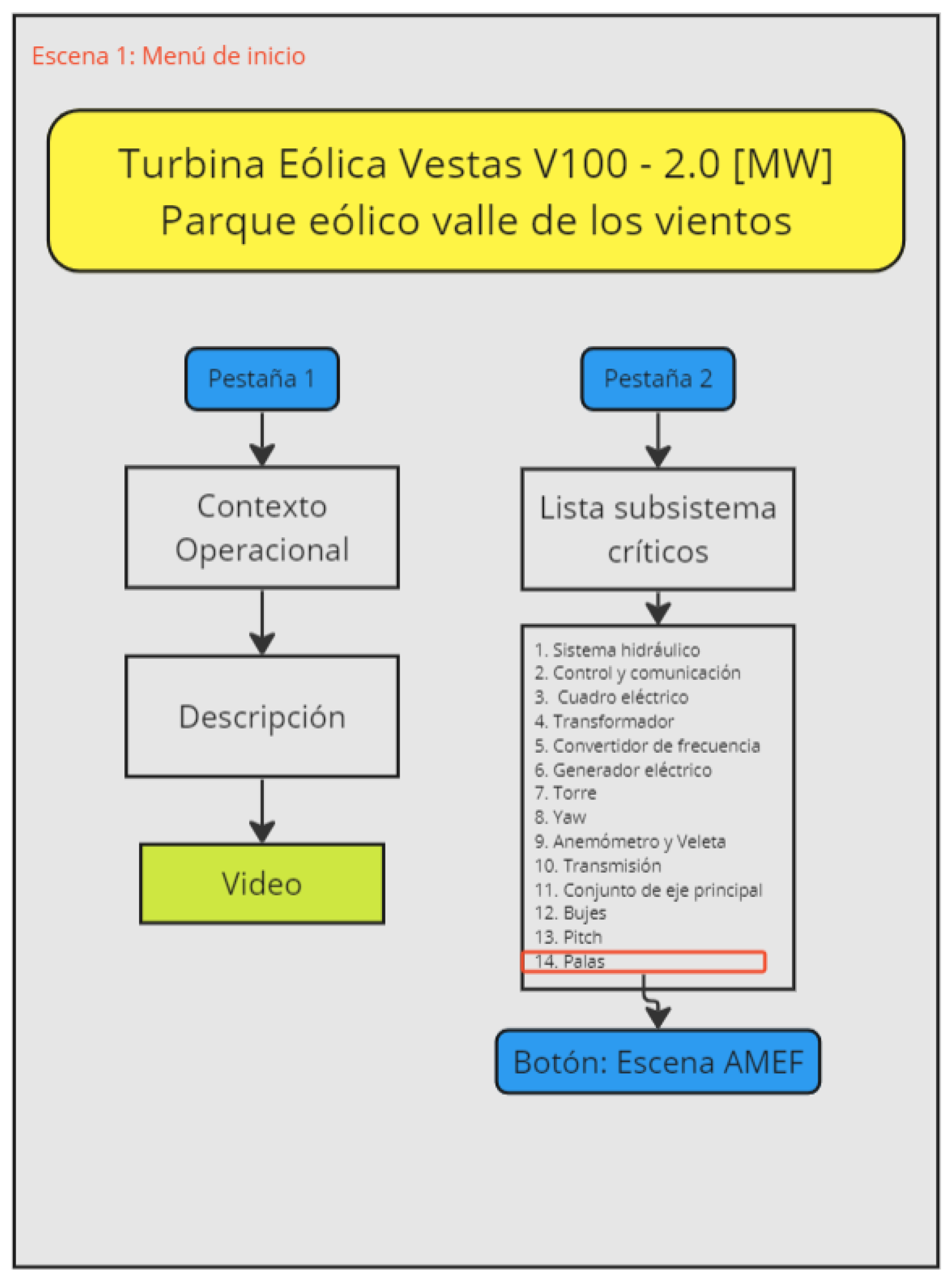

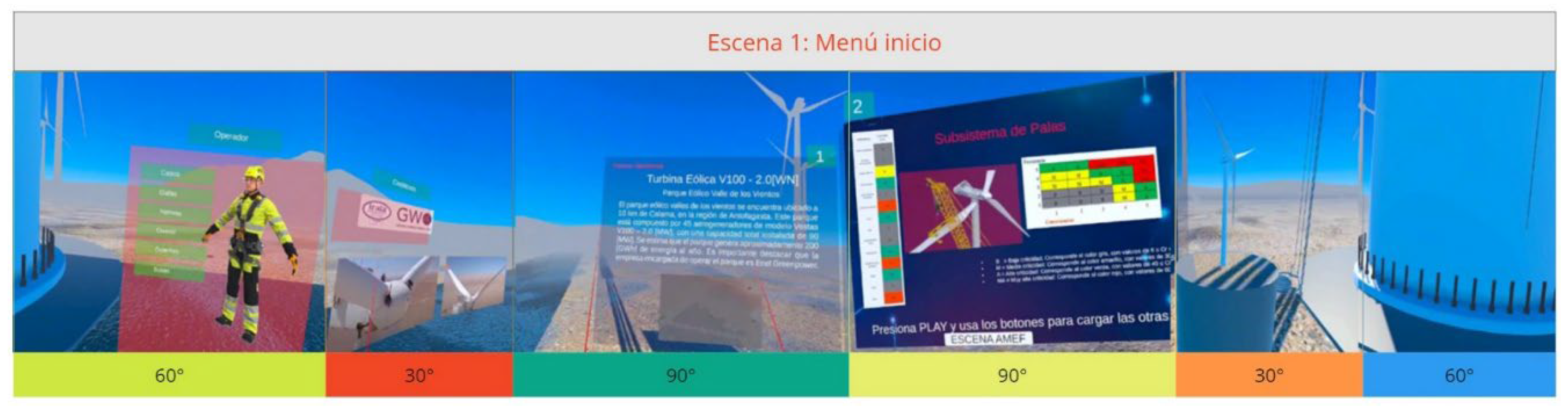

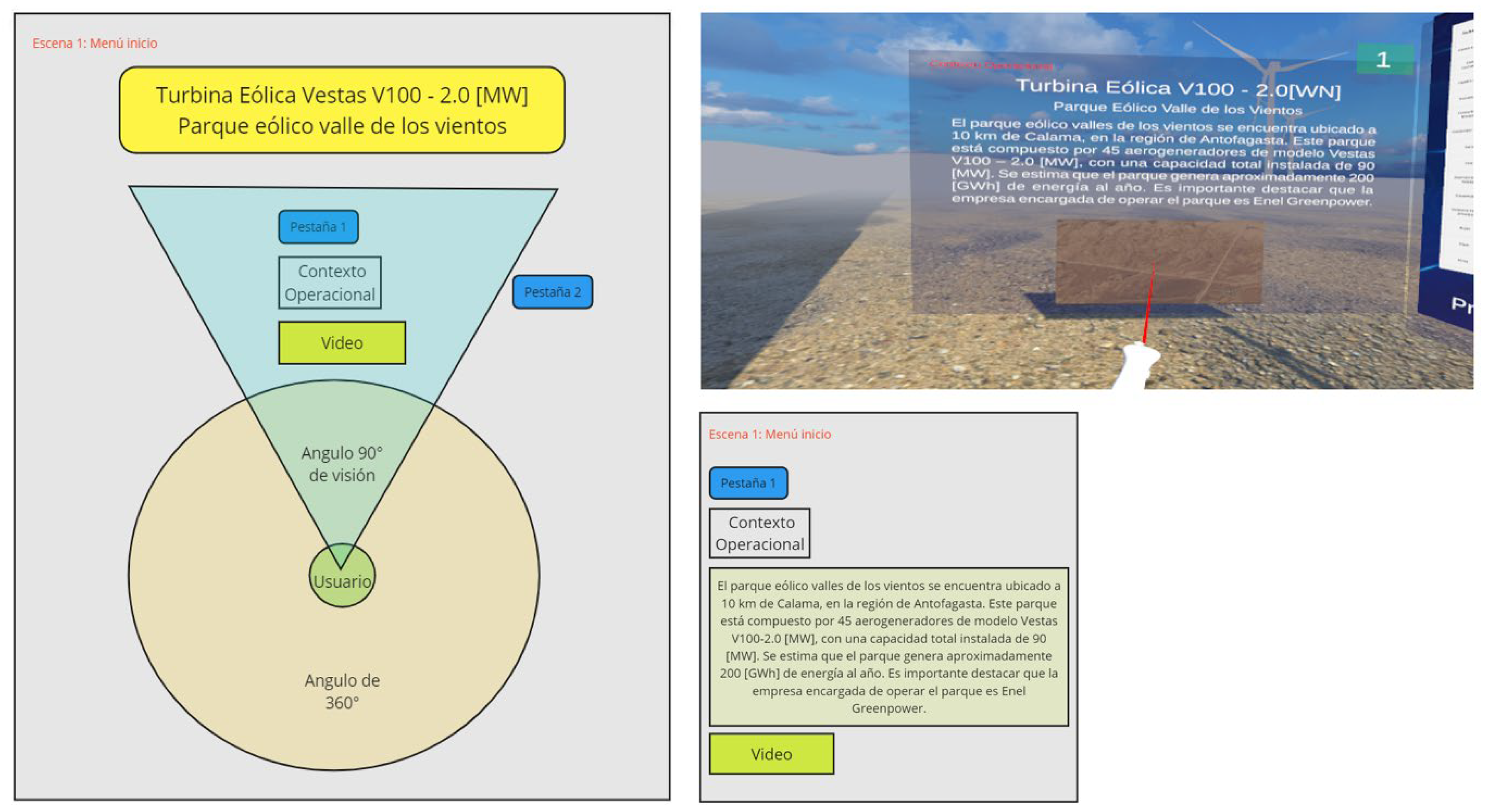

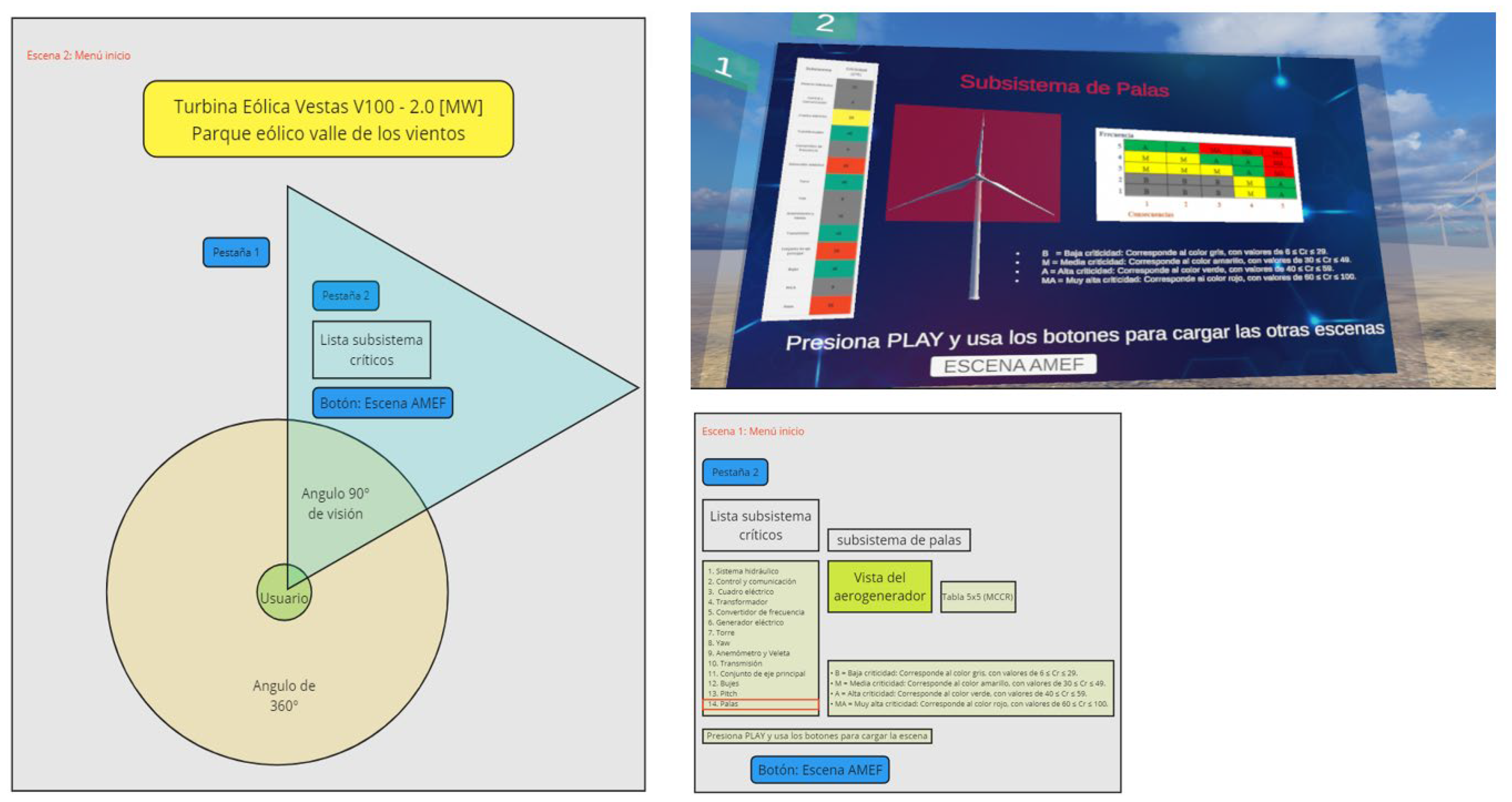

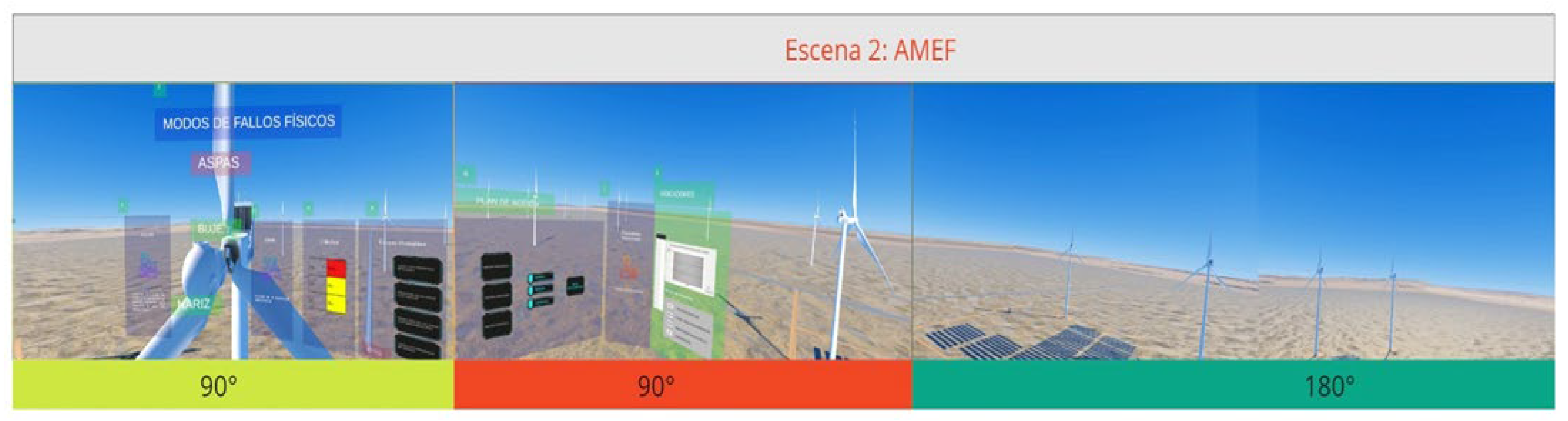

- Start Menu Scene: The simulator includes a start menu screen, which displays the operational context of the V100–2.0 MW wind turbine. It also features a screen showing the most critical subsystems, where the blade subsystem is identified as the most critical. Additionally, a button is provided to access the FMECA scene of the wind turbine (Figure 10).

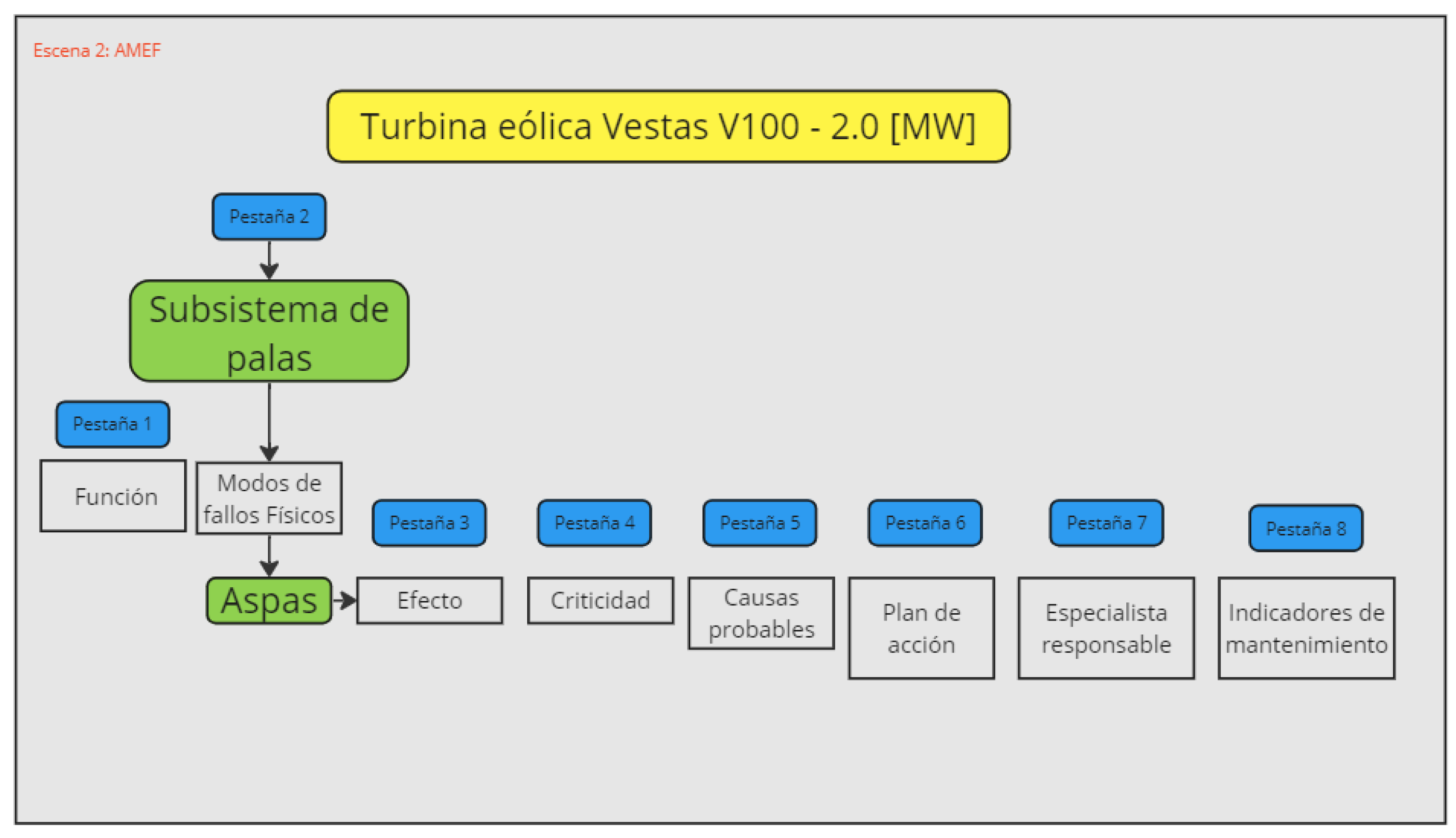

- ▪

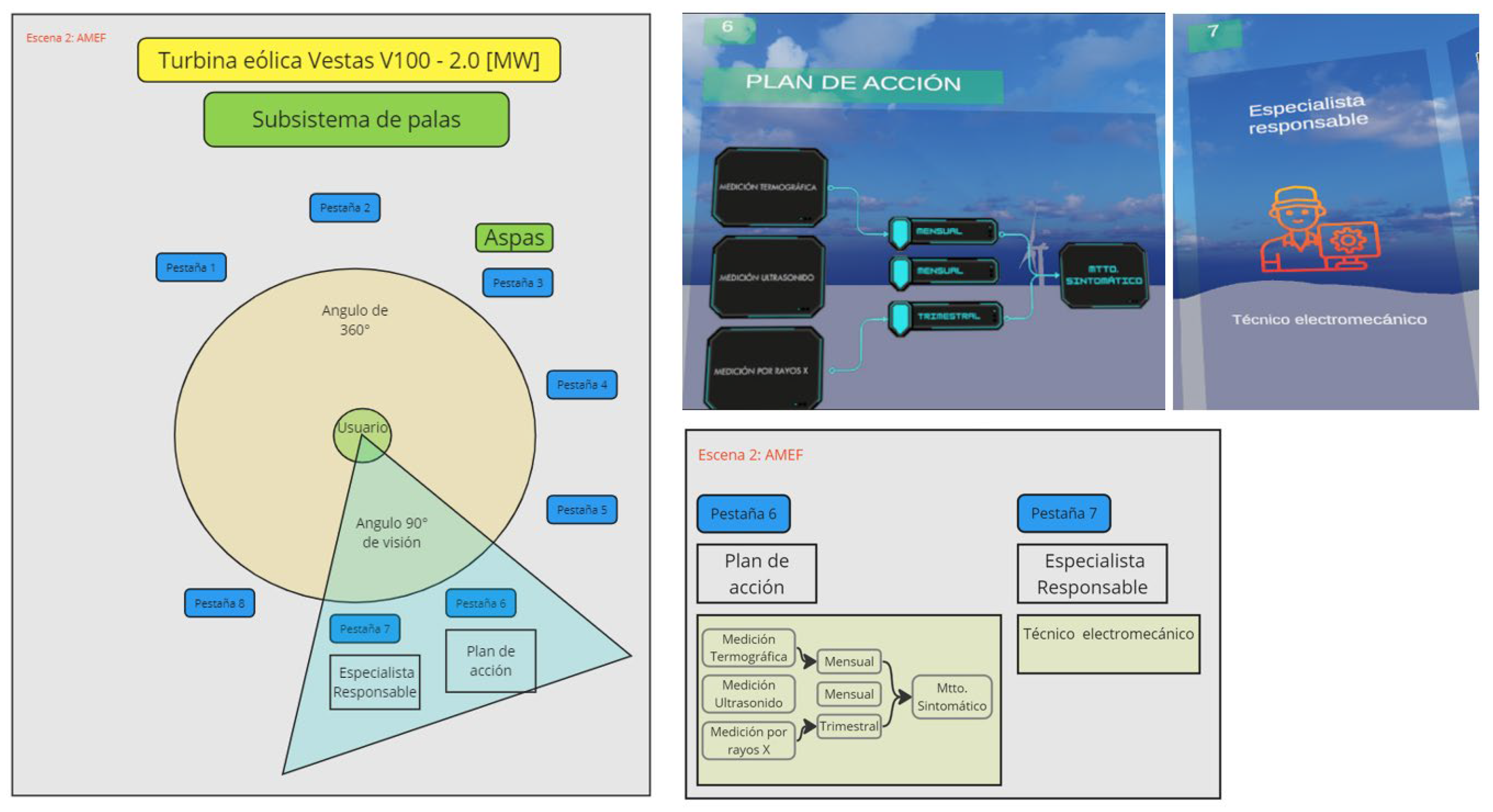

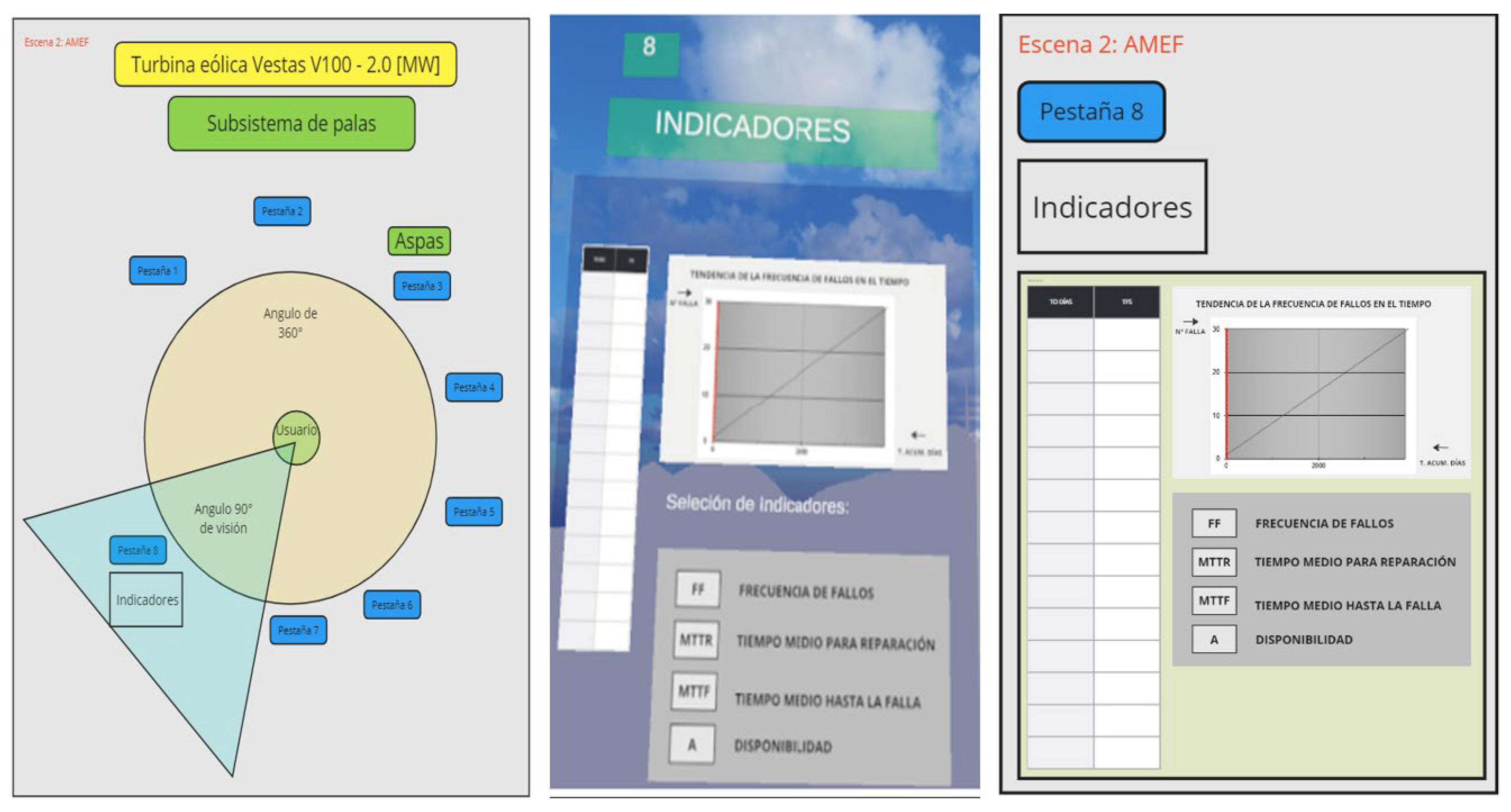

- FMECA Scene: In this section, users can visualize the FMECA tool applied to the blade subsystem, where the criticality levels, probable causes, and corrective action plans are presented in an interactive and educational format, overlaid on the 3D model of the blades (Figure 11).

6. Practical Implementation of the Digital Tool: FMECA–VR 0.1

6.1. Start Menu Scene

- -

- Panoramic view of the wind farm, where turbines in operation and their spatial layout within the environment can be observed.

- -

- Technical information about the VESTAS V100–2.0 MW wind turbine, including its operational context, main components, operator safety elements, and certifications.

- -

- Access to fault analysis modules, where critical subsystems such as the blades are presented, along with a link to the FMECA scene.

6.2. Description of the Main Tabs

- -

- Operational Context: The image shows the visual representation of the Operational Context within the FMECA–VR 0.1 platform, used for maintenance training of wind turbines in a virtual environment (Figure 13).

- -

- Criticality System: The image displays the subsystem criticality analysis structure within the FMECA–VR 0.1 tool. Through the virtual reality platform, users can identify and rank key wind turbine components, focusing on those with the greatest impact on system reliability and maintainability (Figure 14).

6.3. FMECA Scene (Failure Modes, Effects, and Criticality Analysis)

6.3.1. Description of the Main Tabs

- -

-

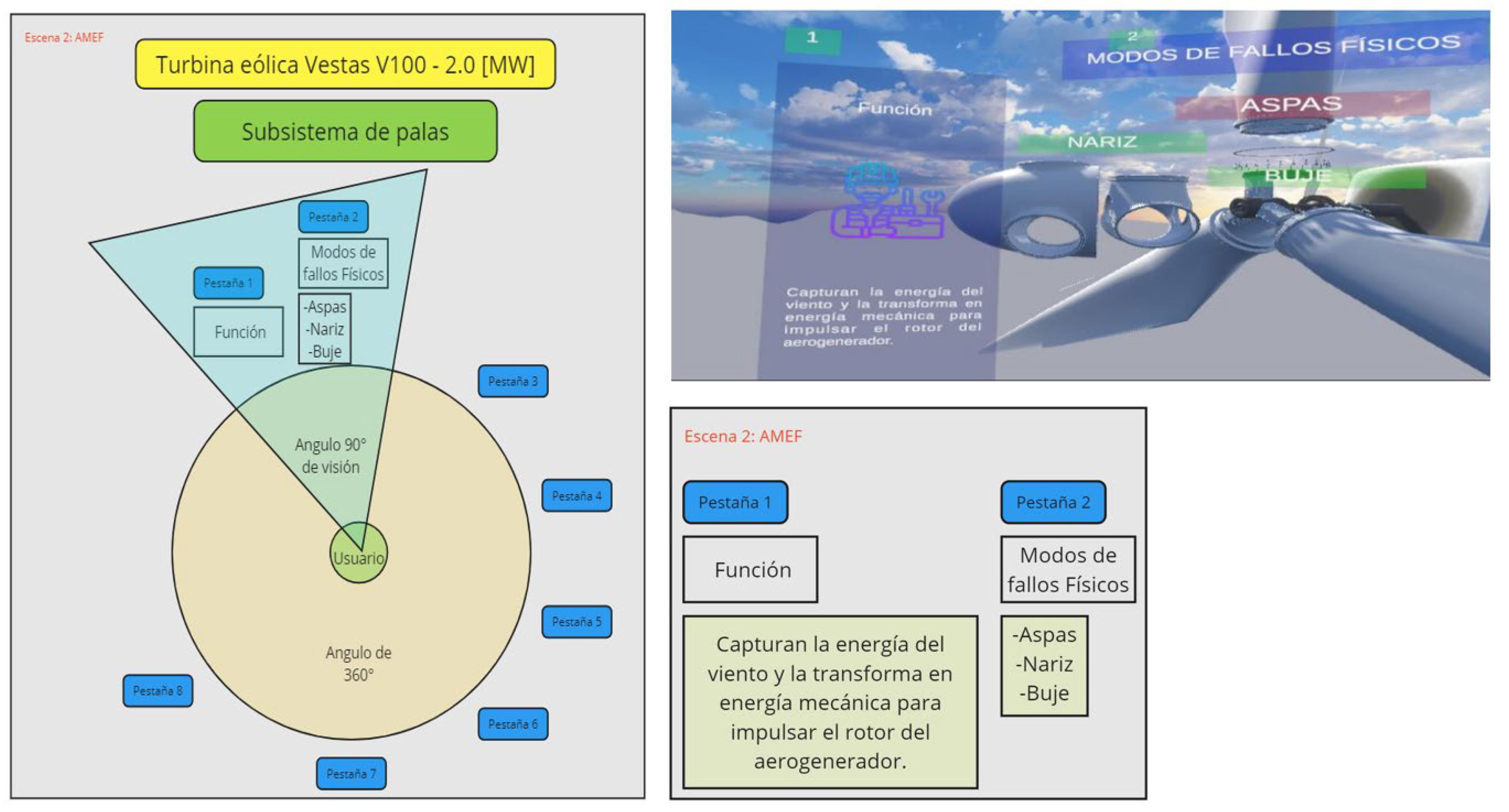

Function and Physical Failure Modes (Figure 16):

- ○

- Circular diagram offering a 90° field of view for the user within a 360° VIRTUAL REALITY environment, with numbered tabs marking various sections of information.

- ○

-

Analysis categories include:

- ▪

- Function (e.g., capturing and converting wind energy)

- ▪

- Physical failure modes (blades, nose cone, and hub).

- ○

- 3D visualization of a wind turbine in the VIRTUAL REALITY space with floating labels identifying components and related failures.

- -

-

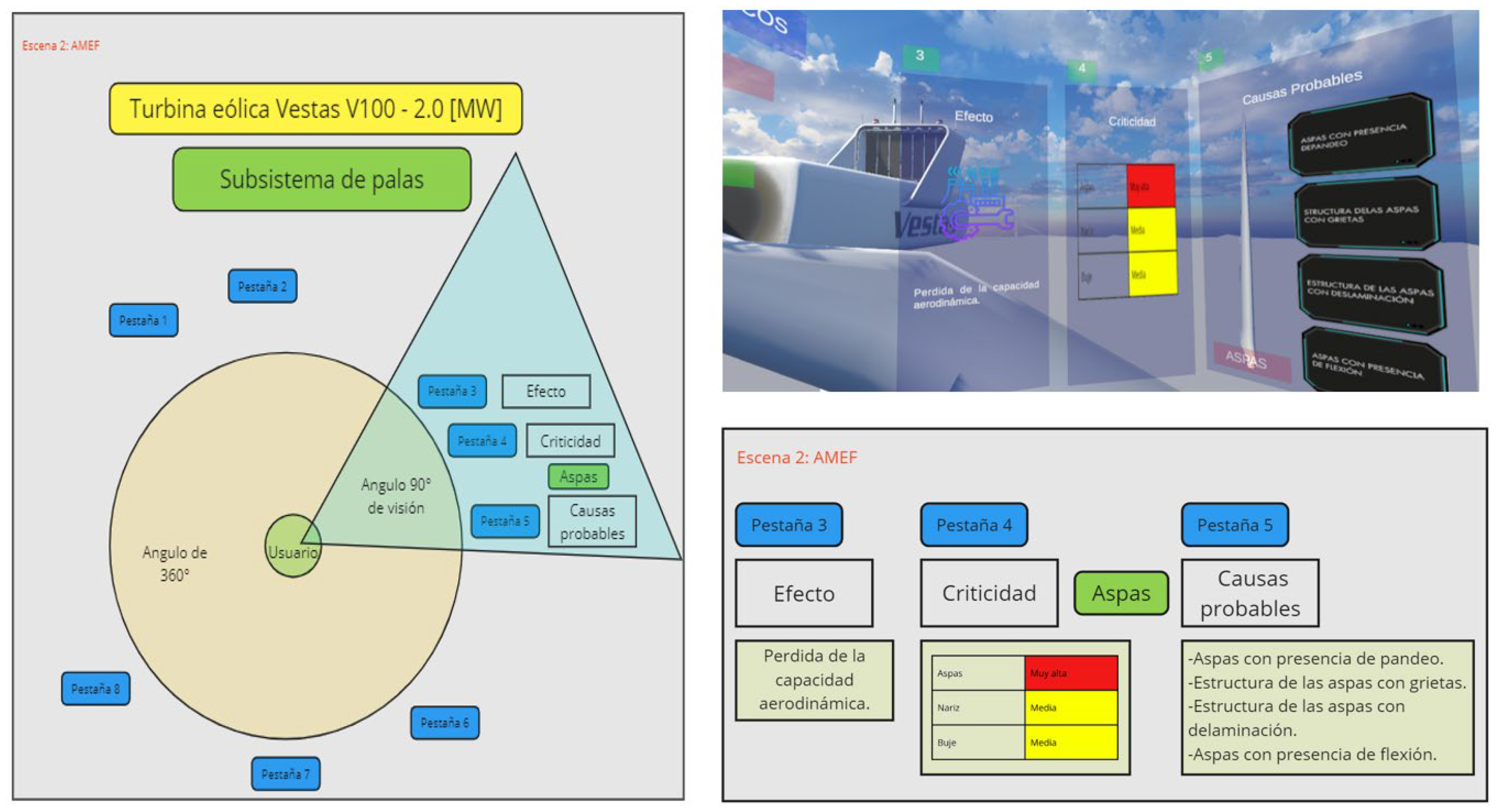

Effects, Failure Criticality, and Probable Causes (Figure 17): The user maintains a 90° view field in a 360° immersive environment, navigating through tabs 1 to 8.

- ○

-

Active tabs:

- ▪

- Tab 3 – Effect: Loss of aerodynamic performance

- ▪

- Tab 4 – Criticality: Indicates criticality levels (Very High for blades, Medium for nose and hub)

- ▪

- Tab 5 – Probable Causes: Includes faults such as cracks, delamination, and bending in the blades

- -

-

Action Plan and Assigned Specialist (Figure 18):

- ○

-

Active tabs:

- ▪

- Tab 6 – Action Plan: Outlines maintenance actions including thermographic and ultrasound inspections (monthly), X-ray inspections (quarterly), and symptomatic maintenance

- ▪

- Tab 7 – Responsible Specialist: Assigns maintenance responsibility to the electromechanical technician

- -

- Demonstration Video: A visual demonstration of the tool in use is presented in the following video (duration: 3 minutes), available on the LinkedIn platform [31]:

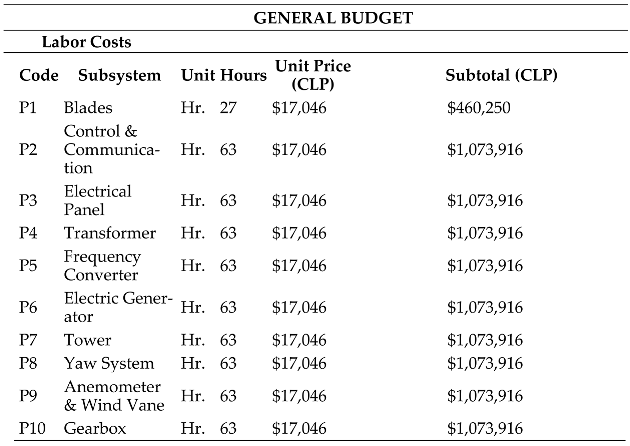

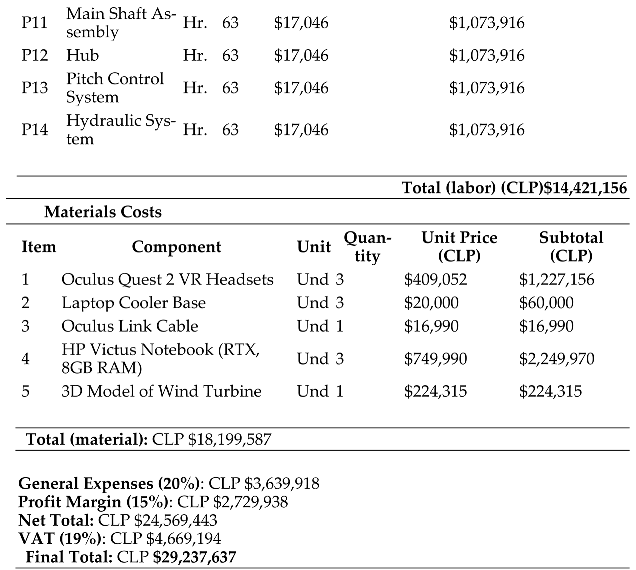

6.4. Economic Analysis of the Metaverse Development: FMECA-VR-0.1 Prototype

7. Key Considerations

7.1. Future Improvements to be included in the FMECA-VR-0.1 Tool

- -

-

First Stage: Definition of Basic Technical Maintenance Indicators (See Figure 19):

- ▪

- Failure Frequency, FF (Reliability)

- ▪

- Mean Time to Repair, MTTR (Maintainability)

- ▪

- Mean Time to Failure, MTTF (Reliability)

- ▪

- Availability (A)

- -

-

Second Stage – Development of Probabilistic and Cost-Based Indicators:

- ▪

- Reliability (Rt): Probability of failure, probability of no failure, time to failure, and failure frequency.

- ▪

- Maintainability (Mt): Probability of successful repair.

- ▪

- Failure Downtime Cost (FDC): Estimated cost due to system unavailability caused by failures.

- -

- Expansion of Functional Scope: Extend the analysis to additional wind turbine subsystems and other critical industrial assets to broaden the technical coverage of the platform and validate its cross-sector applicability [34].

- -

- -

- -

- -

- Validation in Real Industrial environments: Conduct pilot tests in collaboration with energy and industrial companies to gather practical feedback that supports further refinement and alignment of the tool with the needs of the productive sector [38].

8. Conclusions and Recommendations

- -

- The development of the FMECA–VR 0.1 tool represents a significant step forward in the digitalization of technical training in maintenance, integrating concepts from Industry 4.0 and the Maintenance Management Model (MMM) within an immersive and interactive environment.

- -

- The practical application to the Valle de los Vientos Wind Farm case study demonstrated the feasibility of applying criticality analysis and failure mode methodologies in virtual environments, facilitating the prioritization of critical assets and the definition of reliability- and maintainability-oriented maintenance plans.

- -

- The FMECA-VR-0.1 tool allows users to simulate failure and maintenance scenarios in safe conditions, accelerating learning processes, reducing human errors, and improving technical performance indicators.

- -

- The incorporation of the blade subsystem as a pilot study confirmed that the use of systematic methodologies (QRCM and FMECA), integrated into virtual reality simulators, enhances maintenance decision-making and strengthens human resource knowledge regarding critical system components.

- -

- FMECA-VR-0.1 is adaptable to various industrial sectors, consolidating its potential as a cross-cutting technical training platform based on operational criticality, data-driven analysis, and immersive technologies.

- -

- General Recommendations to Consolidate the Development of FMECA-VR-0.1:

- -

- Broaden practical validation by including additional subsystems and multiple failure scenarios, allowing the evaluation of the tool’s scalability and effectiveness across various operational contexts.

- -

- Incorporate real-time feedback functionalities within the VR environment, enabling a personalized training experience based on user profiles and reinforcing self-directed learning.

- -

- Develop performance assessment metrics for users within the immersive environment, focused on reaction times, diagnostic accuracy, and maintenance strategy selection.

- -

- Explore integration with digital twins and SCADA systems, which would strengthen synchronization between real system data and its virtual replica, enabling more robust predictive functionalities.

- -

- Establish collaborations with academic institutions and industrial companies to implement technical training pilots using FMECA-VR-0.1 and gather feedback from both academic and production environments.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Nomenclature

References

- Frank, A. G., Dalenogare, L. S., & Ayala, N. F. (2019). Industry 4.0 technologies: Implementation patterns in manufacturing companies. International Journal of Production Economics, 210, 15–26.

- Rußmann, M., Lorenz, M., Gerbert, P., Waldner, M., Justus, J., Engel, P., & Harnisch, M. (2015). Industry 4.0: The future of productivity and growth in manufacturing industries. Boston Consulting Group, 9(1), 54–89.

- De Carolis, A., Macchi, M., Negri, E., & Terzi, S. (2017). A maturity model for assessing the digital readiness of manufacturing companies. IFIP international conference on advances in production management systems (pp. 13–20). Springer.

- Crespo Márquez, A. (2022). Asset Health Indexing and Life Cycle Costing. In: Digital Maintenance Management. Springer Series in Reliability Engineering. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Gaspar, J. L. (2021). El fin de la INERCIA: de la revolución a la protopía digital: Origen, evolución e impacto del nuevo paradigma tecnológico, social y empresarial. Retrieved from https://www.elfindelainercia.com/.

- Tao, F., Zhang, H., Liu, A., & Nee, A. Y. (2019). Digital twin in industry: State-of-the-art. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics, 15(4), 2405-2415.

- BMW Group. (2021, August 5). Predictive maintenance: When a machine knows in advance that repairs are needed. Retrieved from Press Club Global Article.: https://www.press.bmwgroup.com/global/article/detail/T0338859EN/predictive-maintenance:-when-a-machine-knows-in-advance-that-repairs-are-needed?language=en.

- Crespo Márquez, A. (2022). Driving the introduction of digital technologies to enhance the maintenance management process and framework. In Digital maintenance management: Guiding digital transformation in maintenance (Springer Series in Reliability Engineering) (pp. 25–30). Springer International Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Kawano, J. (2024, October 30). Condition-Based Vs Reliability-Centered Maintenance. Retrieved from VIDYATEC: https://vidyatec.com/blog/condition-based-vs-reliability-centered-maintenance/.

- Wielemaker, P. (2023). ISO 55000 and the Industrial World of Today: Leveraging Digital Twin and Predictive Maintenance for Optimal Asset Management. GE Digital. Retrieved from https://www.ge.com/digital/blog/iso-55000-and-industrial-world-today.

- Capgemini. (2022). Gemelos digitales: la inteligencia artificial adaptada al mundo real. Capgemini. Retrieved from https://www.capgemini.com/es-es/investigacion/biblioteca-de-investigacion/gemelos-digitales/.

- European Commission. (2021). Industry 5.0: Towards a sustainable, human-centric and resilient European industry. (KI-BD-20-021-EN-N). Directorate-General for Research and Innovation. [CrossRef]

- Bertet, N. (2024). Convergencia IT-OT-IIoT en la Intelligent Industry. Una revolución tecnológica impulsada por IoT, Cloud y AI. Retrieved from Capgemini: https://www.capgemini.com/es-es/investigacion/biblioteca-de-investigacion/convergencia-it-ot-iiot-en-la-intelligent-industry/.

- Galar, D., Kumar, U. (2024). Digital Twins: Definition, Implementation and Applications. In: Varde, P.V., Kumar, M., Agarwal, M. (eds) Advances in Risk-Informed Technologies. Risk, Reliability and Safety Engineering. Springer, Singapore. [CrossRef]

- Jones, D., Snider, C., & Nassehi, A. (2020). Characterising the digital twin: A systematic literature review. CIRP Journal of Manufacturing Science and Technology, 29, 36-52.

- Guiffo Kaigom, E. (2024). Potentials of the Metaverse for Robotized Applications in Industry. Procedia Computer Science, Volume 232,1829-1838.

- Parra, C., y Crespo, A. “Ingeniería de Mantenimiento y Fiabilidad Aplicada en la Gestión de Activos. Desarrollo y aplicación práctica de un Modelo de Gestión del Mantenimiento (MGM)”. Segunda Edición. Editado por INGEMAN, Escuela Superior de Ingenieros Industriales, Sevilla, España.

- Crespo Márquez, A., Moreu de León, P., Gómez Fernández, J.F., Parra Márquez, C. and López Campos, M. (2009). The maintenance management framework: A practical view to maintenance management. Journal of Quality in Maintenance Engineering, Vol. 15 No. 2, pp. 167-178. [CrossRef]

- Parra, C., Morán, C., Pizarro, F., Duque, P., Aránguiz, A., González-Prida, V., & Parra, J. (2024). Implementation of the Asset Management, Operational Reliability and Maintenance Survey in Recycled Beverage Container Manufacturing Lines. Information, 15(12), 784. [CrossRef]

- Parra C., González-Prida V., Candón E., De la Fuente A., Martínez-Galán P., Crespo A. (2020). Integration of Asset Management Standard ISO55000 with a Maintenance Management Model. In: Crespo Márquez A., Komljenovic D., Amadi-Echendu J. (eds) 14th WCEAM Proceedings. WCEAM 2019. Lecture Notes in Mechanical Engineering. Springer, Cham. [CrossRef]

- Parra, C., Crespo, A. Parra, J., Kristjanpoller, F., Tino, G., Viveros, P., y González-Prida, V. (2021). Metodología básica de Análisis de Riesgo para evaluar la Criticidad de Activos Industriales. Caso de estudio: Línea de manufactura de envases biodegradables. [CrossRef]

- ISO 55000:2014. Asset management — Overview, principles and terminology. International Organization for Standardization. https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:55000:ed-1:v2:en.

- Comisión Nacional de Energía de Chile (2022). Informe anual de generación renovable en Chile. https://www.cne.cl.

- Vestas (2021). V100-2.0 MW Technical Specification Sheet. https://www.vestas.com.

- Siemens Mobility. (2024). Digital transformation for sustainable mobility – with Railigent X. Retrieved from https://www.mobility.siemens.com/global/en/portfolio/digital-solutions-software/digital-services/railigent-x.html.

- GE Digital. (2022). Webinar Session 3: Renewables. Retrieved from ge.com/digital: https://www.ge.com/digital/sites/default/files/download_assets/digital-solutions-for-renewables-whitepaper.pdf.

- Ukoba, K., Olatunji, K. O., Adeoye, E., Jen, T.-C., & Madyira, D. M. (2024). Optimizing renewable energy systems through artificial intelligence: Review and future prospects. Energy & Environment, 35(7). [CrossRef]

- Caterpillar. (2023). Enhancing Quality and Post-Sales Reliability with Real-Time Monitoring and ISO 9001 Standards. Retrieved from Cat® Connect Secured Remote Asset Monitoring: https://www.cat.com/en_US/by-industry/electric-power/product-support/cat-connect.html.

- Generador de turbina de viento modelo 3d. https://www.turbosquid.com/es/3d-models/wind-turbine-3d-model-1241219.

- Oculus (2023). Oculus Quest 2 Specifications. https://www.meta.com/quest/products/quest-2/.

- LinkedIn (2024). Video de demostración de la herramienta FMECA – VR 0.1. Plataforma LinkedIn. https://www.linkedin.com/feed/update/urn:li:activity:7200352283866349568/.

- Galar, D., Kumar, U., & Lee, J. (2012). E-maintenance. Springer Series in Reliability Engineering.

- Jardine, A. K. S., Lin, D., & Banjevic, D. (2006). A review on machinery diagnostics and prognostics implementing condition-based maintenance. Mechanical Systems and Signal Processing, 20(7), 1483–1510.

- García-Peñalvo, F. J., & Conde, M. Á. (2014). The impact of a virtual learning environment on the learning process and student outcomes. Computers in Human Behavior, 31, 494–504.

- Wang, P., Wu, P., Wang, J., Chi, H. L., & Wang, X. (2018). A critical review of the use of virtual reality in construction engineering education and training. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15(6), 1204.

- Uhlemann, T. H. J., Lehmann, C., & Steinhilper, R. (2017). The digital twin: Realizing the cyber-physical production system for Industry 4.0. Procedia CIRP, 61, 335–340.

- González-Prida, V., Parra Márquez, C., Viveros Gunckel, P., Rodríguez, F. K., & Crespo Márquez, A. (2025). Digital Transformation in Aftersales and Warranty Management: A Review of Advanced Technologies in I4.0. Algorithms, 18(4), 231. [CrossRef]

- IEEE Standards Association. (2021). IEEE Standard for Augmented Reality Learning Experience Models (ARLEM).

|

|

| Subsystem | Function | Physical Failure Modes (Components) | Failure Effect | Criticality Level | Value | Probable Causes |

| Blades | Capture wind energy and convert it into mechanical energy to drive the wind turbine rotor. | Blade | Loss of aerodynamic capability. | Very High Criticality | 60 | Blades showing buckling |

| Blade structure with cracks | ||||||

| Blade structure with delamination | ||||||

| Blades showing bending | ||||||

| Nose | Loss of aerodynamic capability. | Medium Criticality | 39 | Nose structure with cracks | ||

| Impact damage from foreign objects on nose | ||||||

| Nose looseness due to poor installation | ||||||

| Presence of corrosion on nose | ||||||

| Hub | Loss of aerodynamic capability. | Medium Criticality | 36 | Hub structure with cracks | ||

| Hub with misalignment | ||||||

| Malfunction in hub orientation mechanism | ||||||

| Presence of corrosion on hub |

| Subsystem | Physical Failure Mode (Components)/Ranking | Probable Causes | Type of Maintenance | Maintenance Task | Application Frequency | Responsible Specialist | Maintenance Plan Costs (USD/year) | Annual Maintenance Hours |

| Blades | Blades/Very High Criticality | Blades showing buckling | Condition-Based Maintenance | Thermographic winding inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | $5,000 | 12 |

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Ultrasound Inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | 12 | ||||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | X-ray Inspection | Quarterly | Electromechanical Technician | 6 | ||||

| Blade structure with cracks | Condition-Based Maintenance | Thermographic winding inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | $5,000 | 12 | ||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Ultrasound Inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | 12 | ||||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | X-ray Inspection | Quarterly | Electromechanical Technician | 6 | ||||

| Blade structure with delamination | Condition-Based Maintenance | Thermographic winding inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | $5,000 | 12 | ||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Ultrasound Inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | 12 | ||||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | X-ray Inspection | Quarterly | Electromechanical Technician | 6 | ||||

| Blades showing bending | Condition-Based Maintenance | Thermographic winding inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | $5,000 | 12 | ||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Ultrasound Inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | 12 | ||||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | X-ray Inspection | Quarterly | Electromechanical Technician | 6 | ||||

| Nose | Nose/Medium Criticality | Nose structure with cracks | Condition-Based Maintenance | Thermographic winding inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | $5,000 | 12 |

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Ultrasound Inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | 12 | ||||

| Impact damage from foreign objects on nose | Condition-Based Maintenance | X-ray Inspection | Quarterly | Electromechanical Technician | 6 | |||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Thermographic winding inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | $5,000 | 12 | |||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Ultrasound Inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | 12 | ||||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | X-ray Inspection | Quarterly | Electromechanical Technician | 6 | ||||

| Nose looseness due to poor installation | Condition-Based Maintenance | Thermographic winding inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | $5,000 | 12 | ||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Ultrasound Inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | 12 | ||||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | X-ray Inspection | Quarterly | Electromechanical Technician | 6 | ||||

| Presence of corrosion on the nose | Condition-Based Maintenance | Thermographic winding inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | $5,000 | 12 | ||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Ultrasound Inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | 12 | ||||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | X-ray Inspection | Quarterly | Electromechanical Technician | 6 | ||||

| Hub | Hub/Medium Criticality | Hub structure with cracks | Condition-Based Maintenance | Thermographic winding inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | $5,000 | 12 |

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Ultrasound Inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | 12 | ||||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | X-ray Inspection | Quarterly | Electromechanical Technician | 6 | ||||

| Hub with misalignment | Condition-Based Maintenance | Thermographic winding inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | $5,000 | 12 | ||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Ultrasound Inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | 12 | ||||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | X-ray Inspection | Quarterly | Electromechanical Technician | 6 | ||||

| Malfunction in hub orientation mechanism | Condition-Based Maintenance | Thermographic winding inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | $5,000 | 12 | ||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Ultrasound Inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | 12 | ||||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | X-ray Inspection | Quarterly | Electromechanical Technician | 6 | ||||

| Presence of corrosion on the hub | Condition-Based Maintenance | Thermographic winding inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | $5,000 | 12 | ||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | Ultrasound Inspection | Monthly | Electromechanical Technician | 12 | ||||

| Condition-Based Maintenance | X-ray Inspection | Quarterly | Electromechanical Technician | 6 |

|

|

|

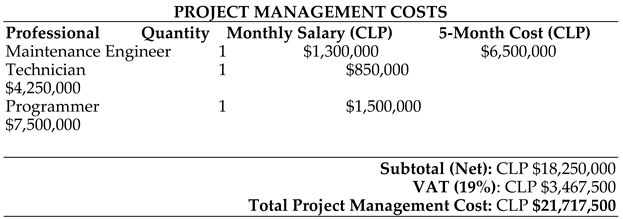

| Strengths | Threats |

| More efficient training processes | Limited realism in simulation |

| Acquisition of parameters through data-driven simulations | Technological dependency |

| Ability to compare scenarios to better understand asset behavior, such as: | Low data reliability for: |

| – Diagnosing and predicting failures | – Maintenance software |

| – Estimating the useful life of physical assets | – Maintenance planning processes |

| – Redesigning assets or control systems to adapt to operating conditions | – Work order management |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).