Submitted:

01 May 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

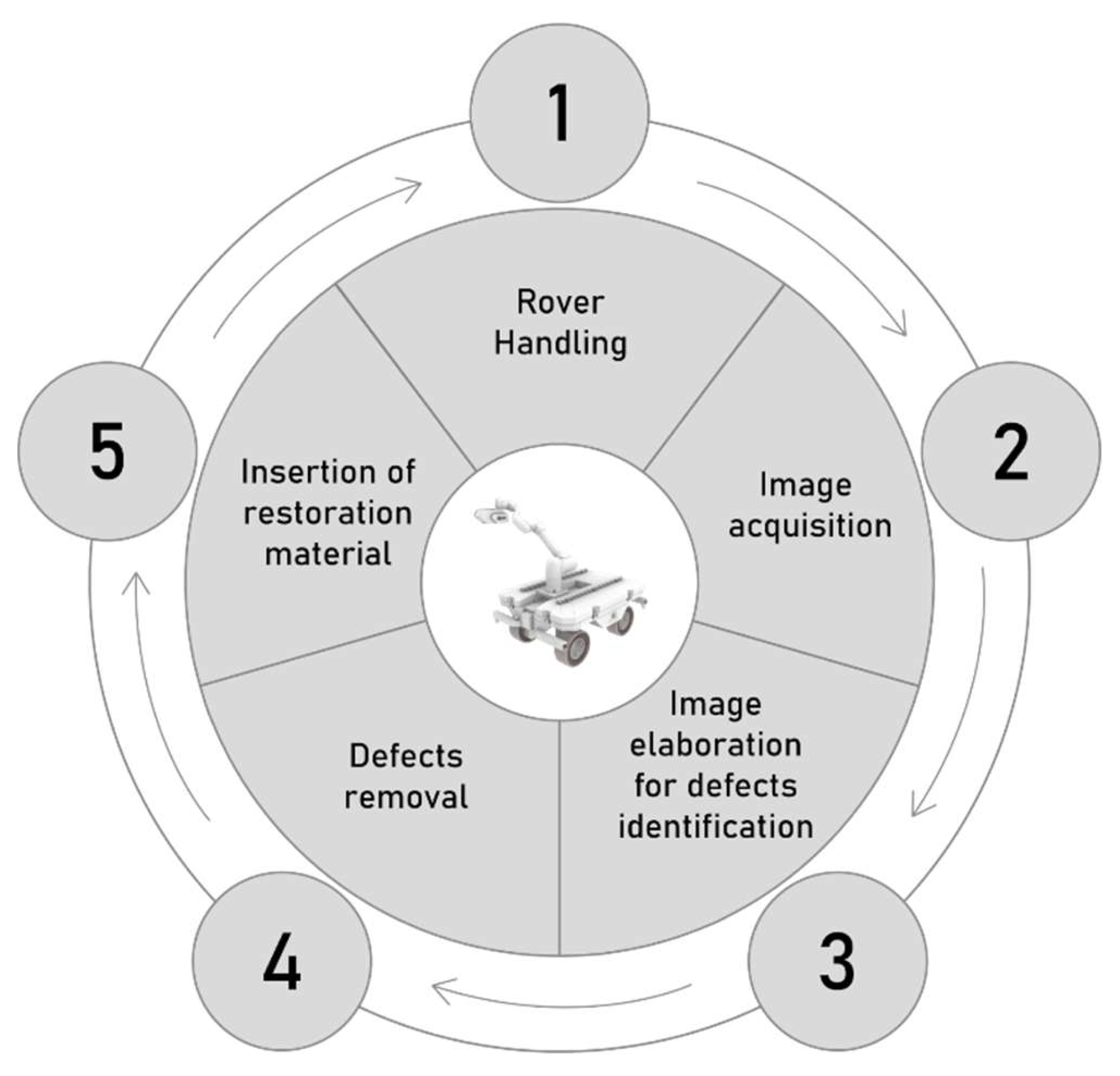

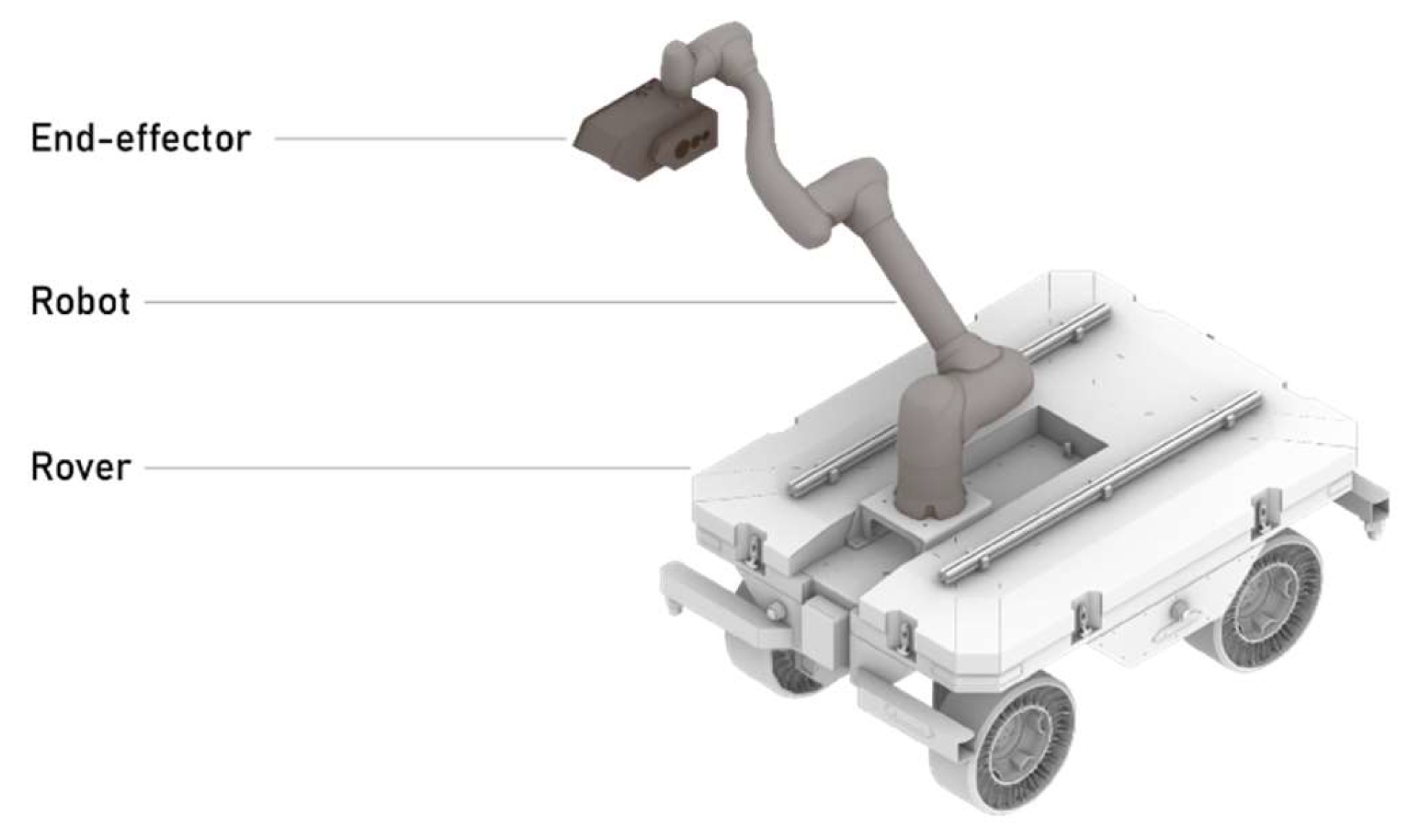

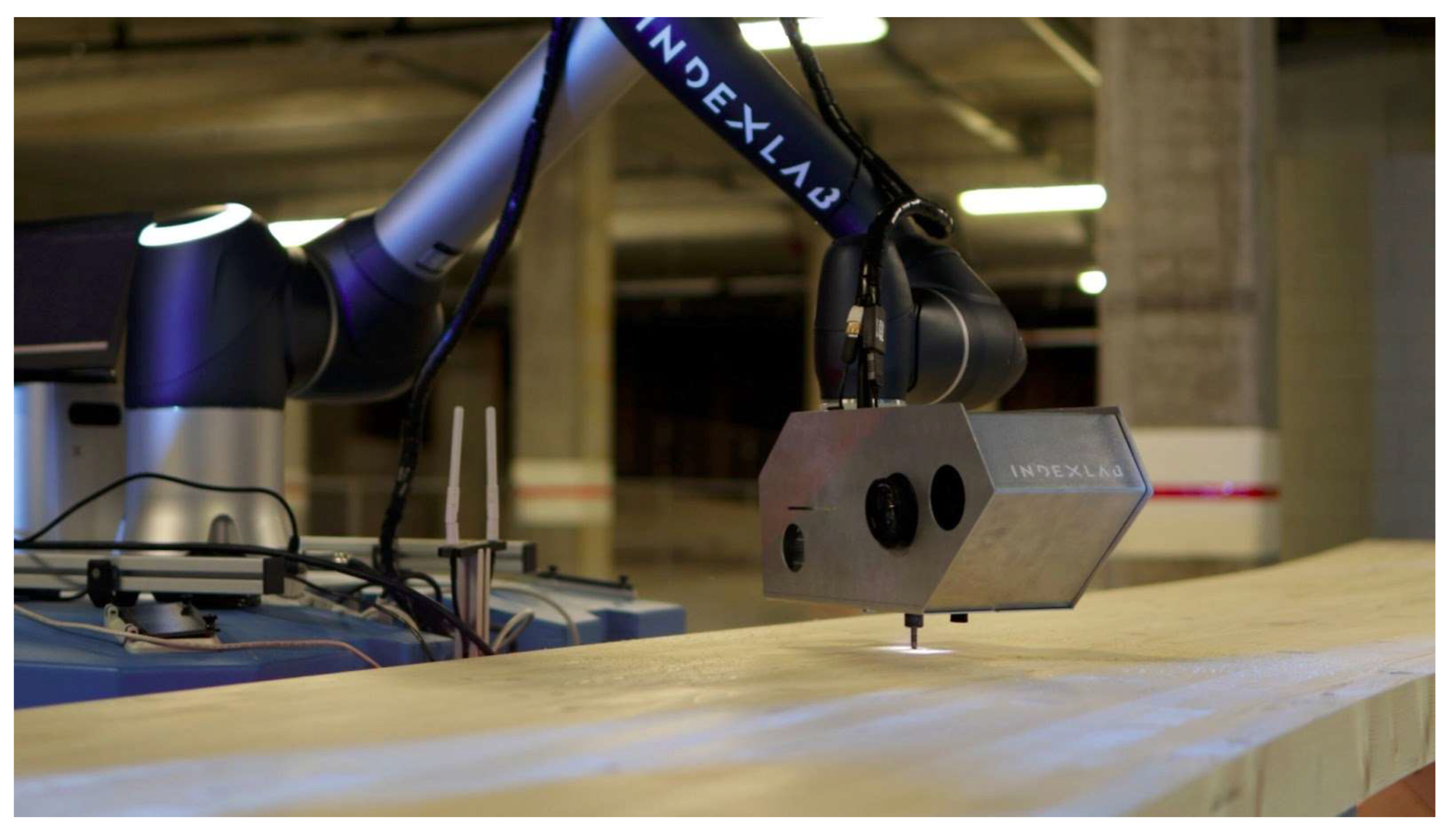

2.1. System Overview

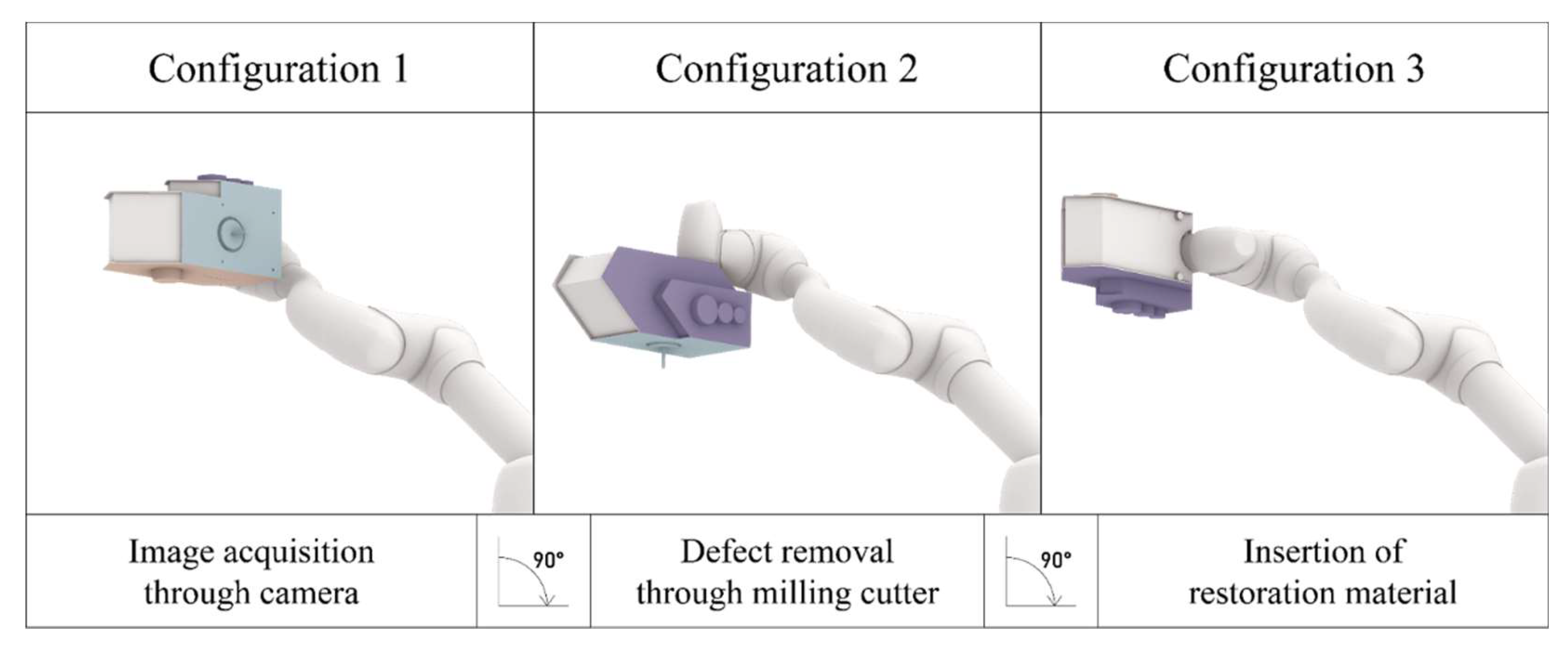

2.2. Hardware Infrastructure

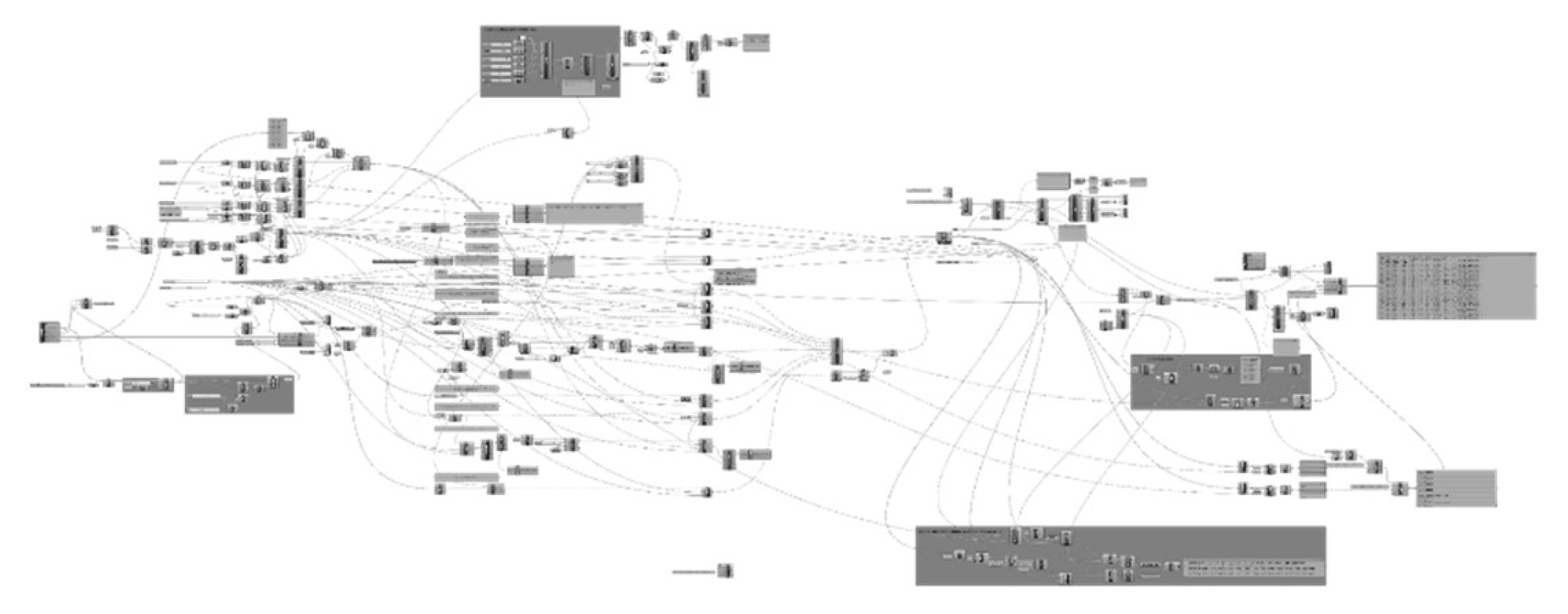

2.3. Software Infrastructure

3. Methods

3.1. Fine-Tuning a Segmentation Model to Perform Defect Recognition

3.1.1. Introduction SAM Fine-Tuning

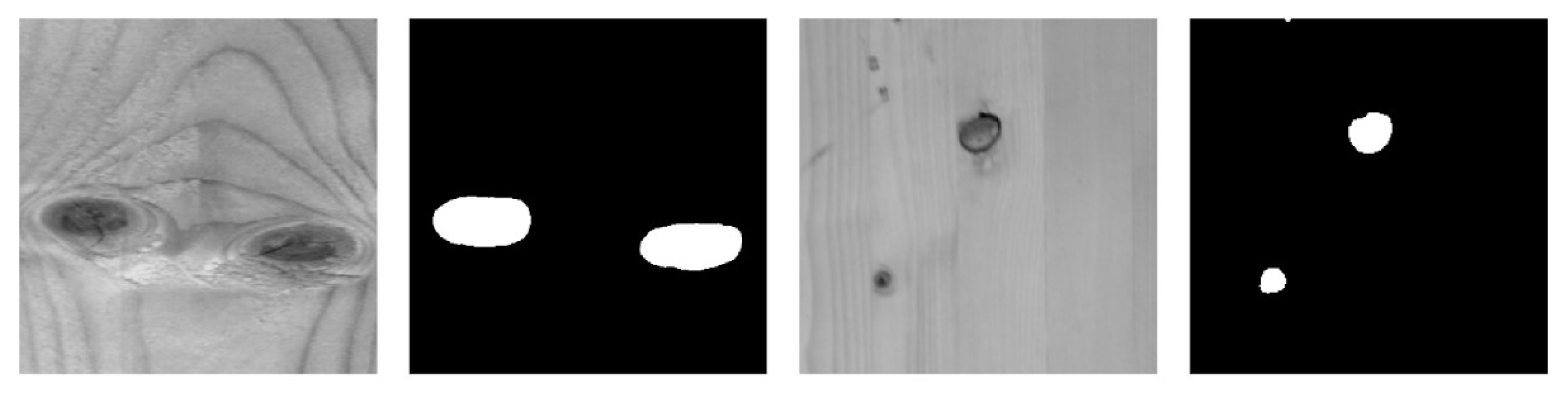

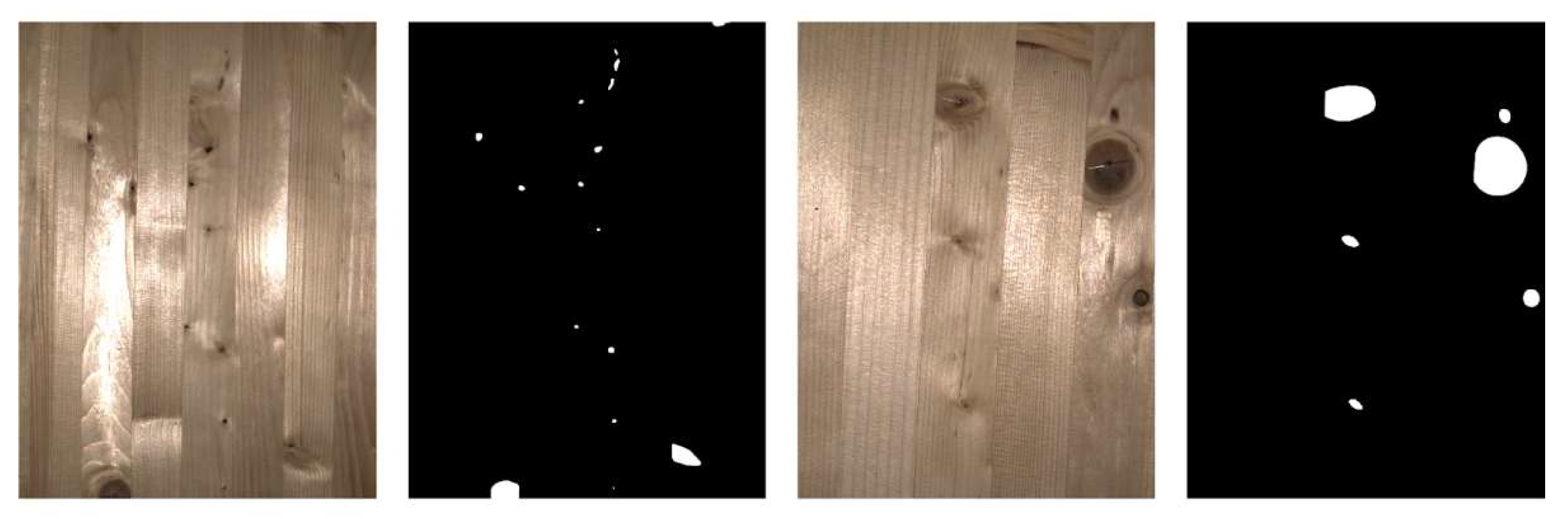

3.1.2. Dataset Preparation for Fine-Tuning

- Dataset 1: 6,760 patches (256×256 pixels)

- Dataset 2: 642 patches (256×256 pixels)

- Dataset 3: 53,117 patches (256×256 pixels) — augmentation of Dataset 1

- Dataset 4: 5,099 patches (256×256 pixels) — augmentation of Dataset 2

3.1.3. Fine-Tuning Process

3.1.4. Dataset Preparation for Inference

3.1.5. Inference Pipeline Configuration

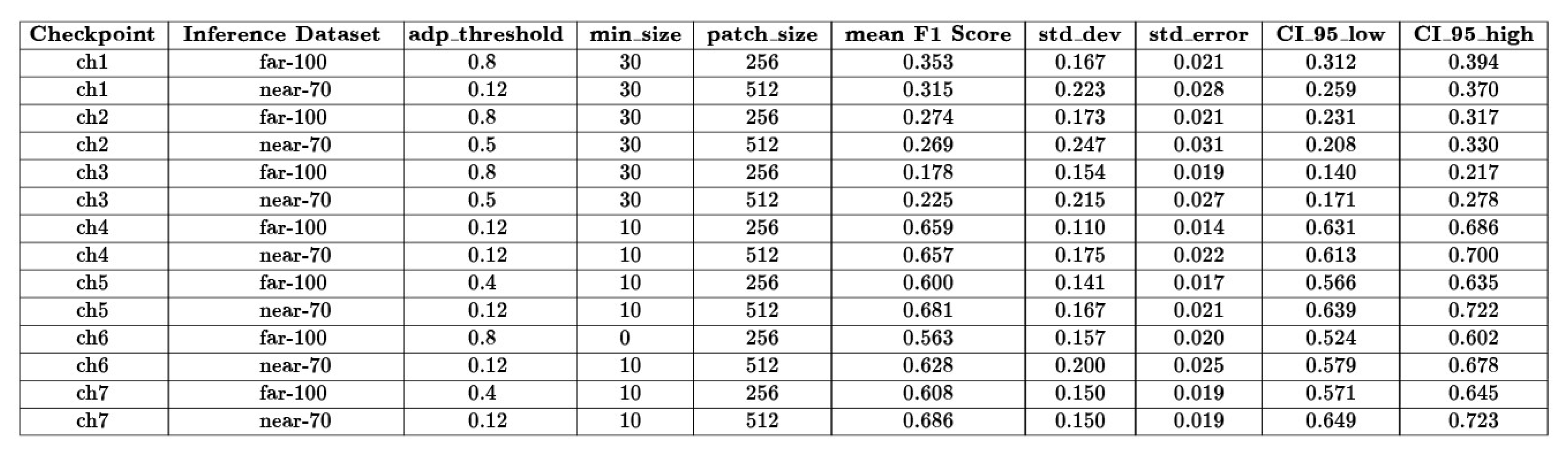

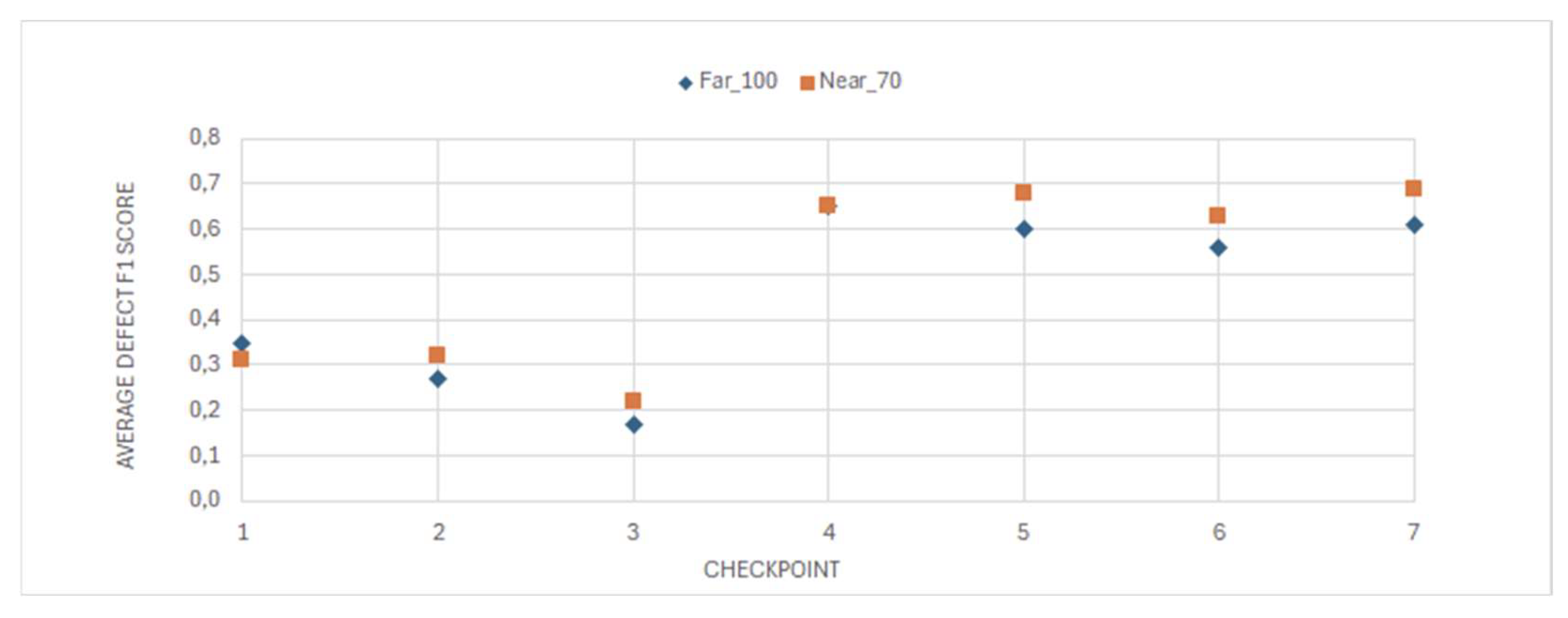

3.1.6. Selection of Optimal Checkpoint

3.2. The five Woodot Subsystems

3.2.1. Rover Handling

3.2.2. Image Acquisition

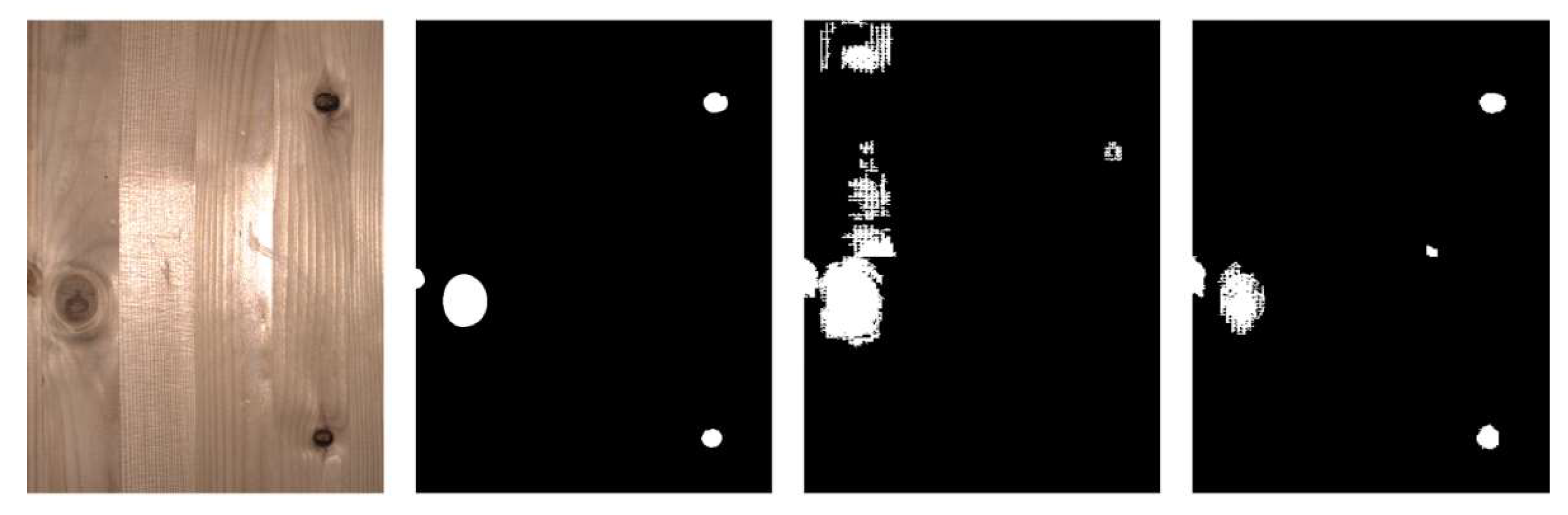

3.2.3. Image Elaboration for Defect Identification

3.2.4. Defect Removal

3.2.5. Insertion of Restoration Material

4. Results

4.1. Navigation and Positioning Performance

4.2. Defect Identification Accuracy

4.3. Restoration Workflow Effectiveness

4.4. Operational Cycle Time

5. Discussion

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Hashim, U.R.; Hashim, S.Z.M.; Muda, A. Automated vision inspection of timber surface defect: A review. Jurnal Teknologi 2015, 77, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biederman, M. Robotic Machining Fundamentals for Casting Defect Removal. M.S. Thesis, Oregon State University, OR, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Li, R.; Zhong, S.; Yang, X. Wood Panel Defect Detection Based on Improved YOLOv8n. BioResources 2025, 20, 2556–2573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, P. Automated Surface Inspection of Cross Laminated Timber. Master’s Thesis, University West, Sweden, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Nagata, F.; Kusumoto, Y.; Fujimoto, Y.; Watanabe, K. Robotic sanding system for new designed furniture with free-formed surface. Robotics Comput. Integr. Manuf. 2007, 23, 371–379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Timber Products Company. Robots Introduced to Grants Pass – Automated Panel Repair Line. Available online: https://timberproducts.com/robots-introduced-to-grants-pass/ (accessed on 19 April 2025).

- Toman, R.; Rogala, T.; Synaszko, P.; Katunin, A. Robotized Mobile Platform for Non-Destructive Inspection of Aircraft Structures. Applied Sciences 2024, 14, 10148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sigma Ingegneria. Il sistema Woodot per l’edilizia del futuro: un rover con braccio robotico per le travi lamellari. Blog Sigma – SAIE 2024 Preview, 26 Sept 2024.

- Ruttico, P.; Pacini, M.; Beltracchi, C. BRIX: An autonomous system for brick wall construction. Constr. Robot. 2024, 8, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil, S. , Vasu, V. & Srinadh, K.V.S. Advances and perspectives in collaborative robotics: a review of key technologies and emerging trends. Discov Mechanical Engineering 2, 13 (2023). [CrossRef]

- Faccio, M. , Granata, I., Menini, A. et al. Human factors in cobot era: a review of modern production systems features. J Intell Manuf 34, 85–106 (2023). [CrossRef]

- gphoto.org. gPhoto Website. Available online: http://gphoto.org/ (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Meta AI. Segment Anything GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/facebookresearch/segment-anything (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- visose. Robots GitHub Repository. Available online: https://github.com/visose/Robots (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Robert McNeel & Associates. Grasshopper3D. Available online: https://www.grasshopper3d.com/ (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Robert McNeel & Associates. Rhino3D Compute Developer Guide. Available online: https://developer.rhino3d.com/guides/compute/.

- Available online: https://www.dewalt.co.uk/product/d26200-gb/8mm-14-fixed-base-router (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- IndexLab. Available online: https://www.indexlab.it/woodot (accessed on 20 August 2024).

- Kirillov, E. Mintun, N. Ravi, H. Mao, C. Rolland, L. Gustafson, T. Xiao, S. Whitehead, A. C. Berg, W.-Y. Lo, P. Dollár and R. Girshick, “Segment Anything,” arXiv preprint arXiv:2304.02643, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Meta AI, “Introducing Segment Anything: Working toward the first foundation model for image segmentation”, Meta AI Blog, 2023. Available online: https://ai.meta.com/blog/segment-anything-foundation-model-image-segmentation/.

- Kodytek, P.; Bodzas, A.; Bilik, P. A large-scale image dataset of wood surface defects for automated vision-based quality control processes. F1000Research 2022, 10, 581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deval, M. , Bianchi, F., & Moroni, C. (2025). Wood knots defects dataset [Data set]. Zenodo. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).