1. Introduction

U.S. President Trump said at an October 2024 event

“It’s my favorite word”…“It needs a public relations firm to help it, but to me

it’s the most beautiful word in the dictionary.” He was talking about the word

‘tariffs’. Mainstream economists have long criticized tariffs as a barrier to

free trade that disproportionately burdens low-income U.S. consumers. But Trump

maintains that tariffs are key to protecting American jobs and products. He

claims that those will raise government revenues, rebalance the global trading

system and be a lever to extract concessions from other countries. The new

administration has also ordered a wipeout of any reference to climate change

across the board. All content related to the climate crisis has been clinically

removed from the White House’s and other agencies’ websites. Grants supporting

climate and environmental justice, clean energy and transportation have been

scrapped as part of a radical ‘money-saving effort’ led by tech billionaire

Elon Musk. Some grantees have hit back, arguing that the cuts are based on

“inaccurate and politicized” claims. Considering the high impact that all these

sided claims have on current economic conditions around the world, as well as

on the future of the planet’s environment, it more than ever seems urgent to

identify and adopt techniques that will help assessing how ‘factual’ claims can

withstand ideological distortion.

The principle that a claim’s validity should be

evaluated independently of its speaker remains a foundation of analytic

philosophy, most prominently articulated in Tarski’s (1944) semantic theory of

truth.(A claim being validated means it has been

supported by evidence or accepted through some epistemic process (e.g., peer

review, empirical testing, or consensus), but this does not guarantee its

truth. Validation reflects current justification, not necessarily objective

reality. By contrast, a claim being true means that it matches facts or reality

independent of validation. Truth is a metaphysical condition. Validation is an

epistemic achievement. A validated claim may later prove false (e.g., Newtonian

physics), while an unvalidated claim could be true (e.g., an unproven

conjecture). Validation is socially constructed; truth is not) Yet,

modern sociopolitical discourse presents a striking paradox: while logic

demands speaker-neutral evaluation, empirical research has demonstrated how

source credibility and ideological alignment routinely override objective

evidence (Mitchell et al., 2019; McDonald, 2021). This speaker-dependence

manifests through what Fricker (2007) terms testimonial injustice—where claims

are systematically discounted based on their source rather than

content—creating epistemic instability across domains from climate science

(Cook et al., 2016) to economic policy. The consequences are profound:

affective polarization (Iyengar et al., 2019) distorts factual interpretation,

the confirmation bias leads people to share ideologically aligned news with

little verification (Nickerson, 1998), and social media algorithms amplify

unreliable content (Goldstein, 2021). Consider how the statement “tax cuts

stimulate growth” is likely to meets broad acceptance when spoken by

conservative economists in front of a conservative audience but may face

rejection from the same audience if it were voiced by liberal commentators.

This article introduces the Adversarial Claim

Robustness Diagnostics (ACRD) framework, which is designed to systematically

measure the resilience of a claim’s validity against such ideological

distortion. Where traditional fact-checking fails against partisan reasoning

(Nyhan & Reifler, 2010), ACRD innovates through a three-phase methodology

grounded in cognitive science and game theory. First, we isolate biases estimated

in the claim’s content due speaker effects using game theory and the principle

of Bayesian Nash equilibrium. Second, strategic adversarial reframing—such as

presenting climate change evidence as originating from fossil fuel

executives—tests boundary conditions of persuasive validity (Druckman, 2001).

The ACRD protocol integrates adversarial collaboration (Ceci et al., 2024) and

Vrij et al.’s (2023) Devil’s Advocate approaches, to reframe claims by

simulating oppositional perspectives. Third, we introduce the Claim Robustness

Index (CRI) that quantifies intersubjective agreement while at the same time

embedding expert consensus (Qu et al., 2025). Finally, the resilience of the

claim is asserted using the CRI, which takes into account temporal reactance and

fatigue. This approach essentially bridges Tarski’s (1944) truth conditions

with Grice’s (1975) implicatures, treating adversarial perspectives as

epistemic stress tests within a non-cooperative game framework (Nash, 1950;

Myerson, 1981) where ideological groups behave like strategic actors.

Operationally, ACRD leverages AI-based

computational techniques. Large language models (LLMs) (Argyle et al., 2023)

can be used to generate counterfactual speaker attributions. BERT-based

analysis (Jia et al., 2019) detects semantic shifts indicative of affective

tagging (Lodge & Taber, 2013). Dynamic mechanisms monitor response

latencies, in which, for instance, rejections under 500ms signal knee-jerk

ideological dismissal rather than considered evaluation. Neural noise injection

serves to debias processing through subtle phrasing variations (Storek et al.,

2023), and longitudinal tracking accounts for reactance effects (De Martino et

al., 2006; Gier et al., 2023). The result is neither a truth arbiter nor ideal

speech (Habermas, 1984), but a diagnostic tool that identifies which claims can

penetrate ideological filters. For instance, (Lutzke et al., 2019) control for

education level and domain-specific knowledge about climate change and find

that respondents exposed to a scientific guidelines treatment were less likely

to endorse and share fake news about climate change.

ACRD applies to the media and policy landscapes. In

an era of tribal epistemology, ACRD offers an evidence-based framework to: (1)

give higher credence to claims benefiting from cross-ideological traction, (2)

identify semantic formulations that bypass identity-protective cognition

(Kahan, 2017), and (3) calibrate fact-checking interventions to avoid backfire

effects (Nyhan & Reifler, 2010; Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2019).

Whereas fact-checkers generally declare binary truth values, ACRD quantifies

how claims remain resilient under ideological stress, offering a dynamic

measure of epistemic robustness.

The focus of this article is on developing a purely

conceptual framework, which will be experimented upon in a future research

stage. We begin in

Section 2 with

identifying the speaker-dependence problem, its theoretical roots in formal

semantics and discussing the current polarization issues in our modern

information age. In

Section 3, we

introduce and develop the ACRD framework. There, we construct our Claim

Robustness Index and discuss its efficacy.

Section 4 introduces the strategic game that leads to analyzing claims validity

assessments as the outcome of a Bayesian Nash equilibrium.

Section 5 compares ACRM with other approaches.

Section 6 discusses the AI architecture that

will support ACRD.

Section 7 details

potential multiple applications of ACRD, its limitations and future extensions.

Our concluding comments appear in the last section.

2. The Difficulty of Speaker-Independent Claim Validity Assessments

2.1. Source Credibility and Speaker-Dependent Epistemology

While Tarski’s (1944) truth-conditional semantics

insists on speaker-neutral propositional evaluation (“Snow is white” is true if

and only if snow is white), Grice’s (1975) conversational “implicature” and

Austin’s (1962) speech-act theory demonstrate how the meanings attached to

utterances inevitably incorporate speaker context. Grice (1975) argues that the

meaning of statements extends beyond literal content to include what he calls

implicatures, i.e., inferences drawn from the speaker’s adherence to a

conversational norm. Austin’s (1962) framework shows that meaning is tied to

institutional contexts and speaker intent. On the other hand, Tarski’s (1944)

truth conditions ignore these potential deflections. Hence, these conflicting

epistemic views become rather consequential when examining political claims

like “Tax cuts stimulate growth,” whose persuasive power fluctuates

dramatically based on speaker identity and ideological affiliation.

The chasm between the logical ideal of a

speaker-neutral ‘truth’ evaluation and the psychological realities of human

cognition creates fundamental problems that undermine rational discourse. Human

cognition has in part evolved to prioritize source credibility over content

analysis—a heuristic that may have served ancestral communities well but fails

catastrophically in modern information ecosystems (Mercier & Sperber,

2017). Hovland and Weiss’s (1951) credibility effects nowadays interact with

social media algorithms to create so-called ‘epistemic bubbles’ (Nguyen, 2020).

These bubbles create huge partisan divides — For instance, in the US, 70% of

Democrats say they have a fair amount of trust in the media, while only 14% of

Republicans and 27% of independents say they do (Brenan, 2022). False claims

spread six time faster than ‘truths’ when shared by in-group members (Vosoughi

et al., 2018).

Nguyen (2020 argues that whereas mere exposure to

evidence can shatter an epistemic bubble, it may instead reinforce an

echo chamber. Echo chambers are much harder to escape. Once in their grip, an

individual may act with epistemic virtue, but the social pressure and context will

tend to pervert those actions. Escaping from an echo chamber may require a

radical rebooting of one’s belief system. Calvillo et al. (2020) study the

relationship between political ideology and threat perceptions as influenced by

issue framing from political leadership and the media. They find that during

the COVID-19 crisis, a conservative frame was associated with people perceiving

less personal vulnerability to the virus; that the virus’s severity was lower

and strongly endorsed the belief that the media had exaggerated its impact and

that the spread of the virus was a conspiracy.

This crisis of source credibility also manifests in

the form of testimonial injustice (Fricker, 2007), where women and minority

experts face systematic credibility deficits. Climate scientists often

perceived as liberal receive less trust from conservatives regardless of

evidence quality (Altenmüller et al., 2024). For Kahan et al. (2012), public

divisions over climate change do not originate from the public’s incomprehension

of science but rather from a conflict between the personal interest of forming

beliefs aligned with one’s own tribal group versus the collective interest

served by making use of the best available science to induce common welfare.

What cognitive factors drive believing versus

rejecting fake news? One of the most broadly accepted assertion is that “belief

in political fake news” is driven primarily by partisanship (Kahan, 2017;

Waldrop, 2017). This assertion is supported by the effects of motivated reasoning

on various forms of judgment (Kahan, 2013; Mercier & Sperber, 2011).

Individuals tend to forcefully debate assertions they identify as violating

their political ideology. On the other hand, they passively and uncritically

accept arguments that sustain their political ideology (Lodge & Taber,

2013). Moreover, there is evidence that political misconceptions are resistant

to explicit corrections (Nyhan & Reifler, 2010; Lewandowsky et al., 2013a).

Given the political nature of fake news, similar motivated reasoning

effects may explain why entirely fabricated claims receive so much attention on

social media. That is, individuals may be susceptible to fake news stories that

align with their political ideology. On the other hand, Pennycook et al. (2019)

document that susceptibility to fake news is driven more by lazy thinking than

by partisan bias per se.

2.2. Speaker-Independence and Cultural Cognition

Tarski’s (1944) truth conditions demand

speaker-neutral evaluation, yet Kahan’s (2017) identity-protective cognition

shows that group allegiance often overrides facts. The human brain relies on

three problematic heuristics when evaluating claims:

1. The Confirmation Bias and Tribal Credentialing

Nickerson (1998) documents the ubiquity of the confirmation bias in human cognition. When individuals selectively interpret evidence to reinforce prior beliefs, this phenomenon is exacerbated by who the speaker of that evidence is and his/her group identity. Often, claims are evaluated through group identity-consistent lenses. Attitudes toward a social policy depend almost exclusively upon the stated position of one’s political party and the party leader. This effect overwhelms the impact of both the policy’s objective content and participants’ ideological beliefs (Cohen, 2003).

Many articles discuss how political biases influence the rejection of facts. An interesting application is in the context of energy policy and renewable energy acceptance. Clarke et al. (2015) find that political ideology strongly shapes public opinion on energy development, with conservatives more likely to oppose renewable energy projects when framed in terms of climate change mitigation, whereas liberals were more supportive. Similarly, Hazboun et al. (2020) examine conservative partisanship in Utah and find that political identity often overrides scientific consensus, with

Republicans expressing greater skepticism toward climate science and renewable

energy compared to Democrats. Mayer (2019) highlights how partisan cues shape local

attitudes and shows that communities with strong Republican leadership are more

resistant to clean energy transitions, regardless of factual evidence about

benefits. Additionally, Bugden et al. (2017) explore how political framing in

the fracking debate leads to polarized perceptions, where pre-existing

ideological beliefs influence interpretations of scientific data. Together,

these studies demonstrate that political biases play a significant role in

shaping fact rejection, particularly when energy policies become entangled with

partisan identity.

More examples: self-identified U.S. Republicans

report significantly higher rates of agreement with climate change science when

the policy solution is free-market friendly (55%) than when the advocated policy

is governmental regulation (22%). On the other hand, self-identified Democrats’

rates of agreement are indifferent to whether the policy solution is

free-market friendly (68%) or governmental regulation (68%) (Campbell &

Kay, 2014). Individuals who self-identify as political conservatives and

endorse free-market capitalism are less likely to believe in climate change and

express concern about its impacts (Feygina et al. 2010; Bohr, 2014; and

McCright et al. 2016). Along the same lines, Kahan (2017) discusses identity

protection, in the sense that individuals are more likely to accept

misinformation and resist the correction of it when that misinformation is

identity-affirming rather than identity-threatening. Thus, when new evidence is

introduced, it actually strengthens prior beliefs when identity-threatening.

These phenomena create what Sunstein (2017) terms

an “epistemic capitulation”— the abandonment of shared truth standards in favor

of tribal epistemology. The consequences include policy paralysis on issues

that can be at the scale of existential threats and/or the erosion of

democratic accountability mechanisms.

2. Affective Polarization

Druckman & Lupia (2016) find that when

individuals’ partisan identities are activated (via a stimulus that accentuates

in-group partisan homogeneity and out-group difference), which triggers

polarization, partisans are more likely to follow partisan endorsements and

ignore more detailed information that they might otherwise find persuasive.

Neural imaging shows partisan statements that appear threatening to one’s own

candidate’s position trigger amygdala responses akin to physical threats

(Westen et al., 2006). Again, affective polarization leads to “belief

perseverance” where people cling to false claims even after correction

(Lewandowsky et al., 2012).

3. Motivated Numeracy

Motivated numeracy refers to the idea that people

with high reasoning abilities will use these abilities selectively to process

information in a manner that protects their own valued beliefs. Research shows

that higher scientific comprehension exacerbates bias on politicized topics

(Kahan, 2017). For instance, Drummond & Fischhoff (2017) show that

conservatives with science training are more likely to reject climate consensus

than liberals. The claim that more education means more cognitive complexity,

and in turn leads to a reduced proclivity among individuals to believe in

conspiracy theories, is overly simplistic. Indeed, van Prooijen (2017)

acknowledges that the relationship between conspiracy belief and education is

more complex than initially thought at first glance. He shows that the main

effect of education on reducing conspiracy belief is no longer significant in

the presence of mediating factors such as subjective social class, feelings of powerlessness,

and a tendency to believe in simple solutions to complex problems (van

Prooijen, 2017).

Digital platforms institutionalize and reinforce

these heuristic biases through:

Algorithmic tribalism: Recommender systems

increase partisan content exposure. In agreement with this, Huszár et al.

(2022) find that content from US media outlets with a strong right-leaning bias

are amplified more than content from left-leaning sources.

Affective feedback loops: The MAD model of

Brady et al. (2021) proposes that people are motivated to share moral-emotional

content based on their group identity, that such content is likely to capture

attention, and that social-media platforms are designed to elicit these

psychological tendencies and further facilitate its spread.

Epistemic learned helplessness: 50% of

Americans feel most national news organizations intend to mislead, misinform or

persuade the public (Knight Foundation, 2023).

2.3. Existing Models for Debiasing and Assess Claim Validity

Nudging (Sunstein, 2014) is a method used for

debiasing. Sunstein’s nudging framework aims at debiasing beliefs and behaviors

by redesigning environments to counteract cognitive limitations. While nudging

may indirectly improve decision quality by making accurate information more

salient (e.g., via defaults or framing), its core purpose is not to

assess claims’ validity but to guide individuals toward choices aligned with

their long-term interests. However, it can acquire an epistemic dimension when

it aims to change one’s epistemic behavior, such as changing one’s mental

attitudes, beliefs, or judgements (Adams and Niker, 2021; Grundmann, 2021;

Miyazono, 2023). For example, a nudge can make people believe certain

statements by rendering those particularly salient or framing them in

especially persuasive ways. Common types of epistemic nudging can include

recalibrating social norms, reminders, warnings, and informing people of the

nature and consequences of past choices.

The Gateway Belief Model (GBM) (van der Linden et

al., 2021) proposes that the perception of scientific consensus acts as a

“gateway” to shaping individual beliefs, attitudes, and support for policies on

contested scientific issues, particularly climate change. The model suggests

that when people are informed about the high level of agreement among

scientists (e.g., the 97% consensus on human-caused climate change), they are

more likely to: 1) update their own beliefs about the reality and urgency of

the issue; 2) increase their personal concern about the problem and 3) become

more supportive of policy actions addressing the issue.

Van der Linden et al.’s (2021) GMB contributes to a

growing literature which shows that people use consensus cues as

heuristics to help them form judgments about whether or not the position

advocated in a message is valid (Cialdini et al., 1991; Darke et al.,

1998; Lewandowsky et al., 2013b; Mutz, 1998; Panagopoulos & Harrison,

2016). The GBM works empirically and demonstrates that correcting

misperceptions of scientific disagreement can reduce ideological polarization

and increase acceptance of evidence-based policies. The effect has been

demonstrated not only for climate change but also for other politicized topics

like vaccines, GMOs, and nuclear power.

Prelec’s (2004) Bayesian Truth Serum (BTS) offers a

mechanism to incentivize truthful reporting by rewarding individuals whose

answers are surprisingly common given their peers’ responses. It is a mechanism

for eliciting honest responses in situations where objective truth is unknown

or unverifiable. Recognizing that individuals may face incentives to misreport,

BTS asks participants for their own answer and also for a prediction about how

others will respond. The method exploits a key psychological insight: respondents

who hold beliefs they consider true will tend to underestimate the

proportion of others that agree with that belief. When the others’ answers turn

out to be statistically more common than they have predicted, this signals

honesty and convergence towards truth. Each participant’s BTS scoring system

encourages this type of behavior and makes honest reporting a Bayesian Nash

equilibrium, even without external verification. BTS is especially valuable in

contexts like opinion polling, forecasting, and preference elicitation. In

those cases, it provides a systematic way to detect and reward truthful

information purely from patterns within the participants’ collective answers.

3. The Adversarial Claim Resilience Diagnostics (ACRD) Framework

The Adversarial Claim Robustness Diagnostics (ACRD)

framework goes beyond conventional fact-checking methodologies by evaluating

how claims withstand adversarial scrutiny. Rather than merely assessing binary

truth values, ACRD quantifies claim resilience — the degree to which a proposition

retains credibility and validity under ideological stress tests. This section

elaborates on the theoretical and operational foundations of ACRD, integrating

key insights from prior sections.

Adversarial collaboration (AC) (Mellers et al.,

2001; Ceci et al., 2024) refers to team science in which members are chosen to

represent diverse (and even contradictory) perspectives and hypotheses, with or

without a neutral team member to referee disputes. Here, we argue that this

method is effective, essential, and often underutilized in claims assessments

and in venues such as fact-checking and the wisdom of crowds. Peters et al.

(2025) argue that adversarial collaborations offer a promising alternative to

accelerate scientific progress: a way to bring together researchers from

different camps to rigorously compare and test their competing views (see also

Meller et al. (2001). The evidence generated by adversarial experiments should

be evaluated with respect to prior knowledge using Bayesian updating. (Corcoran

et al., 2023).

3.1. A Three-Phase Diagnostic Tool: mixing Game Theory and AI

ACRD posits that truth claims exist on a spectrum

of epistemic robustness, which is determined by the ability to maintain

or even increase signal coherence when subjected to adversarial framing. Our

approach draws on:

Bayesian belief updating (Corcoran et al., 2023); where adversarial challenges function as likelihood/posterior probability adjustments.

Popperian falsification (Popper, 1963); that treats survival under counterfactual attribution as resilience and thus robustness.

Game-theoretic equilibrium (Nash, 1950; Myerson, 1981); where validation (with the possibility of achieving truth-convergence) emerges as the stable point between opposing evaluators.

The ACRD framework is uniquely intended to analyze

the following core scenario centered around the process of evaluating the

validity of a statement when two camps have strong opposed views in the matter.

To simplify, we will analyze the situation when two evaluators from two

ideologically opposed groups 1 and 2 must evaluate a claim P, which has been

spoken by a person who embodies the ideological values of group 1.(The fact that we select this scenario does not diminish

the potential generalization of our approach to many groups.) ACRD is

thus a diagnostic process that is operationalized in three phases:

Baseline phase –A statement P is spoken by a non-neutral speaker (here associated with group 1). Each group receives information regarding a scientific/expert consensus (made as ‘objective’ as possible), to which they each assign a level of trust(Of course this expert baseline neutrality can be challenged, and this will be reflected in the trust levels. To approximate neutrality, Cook et al. (2016) define domain experts as scientists who have published peer-reviewed research in that domain. Qu et al. (2025) propose a robust model for achieving maximum expert consensus in group decision-making (GDM) under uncertainty, integrating a dynamic feedback mechanism to improve reliability and adaptability.). Each group’s prior validity assessment of P takes into account the degree of tie they have with their respective ideologies, their trust level of the expert’s assessment, and the expert’s validity score itself. They come up with their own evaluation as a result of a strategic game exhibiting a Nash equilibrium.

Reframing phase – Each group is presented with counterfactuals. Claim P is either framed as originating from an adversarial source or the reverse proposition ~P is assumed spoken by the original source in a “what if” thought-experiment (in that case, it is important to decide at the outset if the protocol is based on a test of P or ~P based on best experimental design considerations), or by using the Devil’s Advocate Approach (Vrij et al., 2023). Claims are adjusted via adversarial collaboration (Ceci et al., 2024).(There is also the possibility that ideological camps jointly formulate statements to minimize inherent framing biases. This process can follow Schulz-Hardt et al. (2006)’s model of structured dissent, requiring consensus on claim wording before testing.) New evaluations are then proposed under the new updated beliefs. These again are solutions to the same strategic game, under new (posterior) beliefs. Actual field studies can operationalize this phase with dynamic calibration to adjust for adversarial intensity based for instance on response latency (<500ms indicates affective rejection; Lodge & Taber, 2013). Semantic similarity scores (detecting recognition of in-group rhetoric) can also be deployed there.

3. AI and Dynamic Calibration Phase– When deployed in field studies, AI-driven adjustments (e.g., GPT-4 generated counterfactuals; BERT-based semantic perturbations) will test boundary conditions where claims fracture using the index developed below. These AI aids can implement neural noise injections (e.g., minor phrasing variations) to disrupt affective tagging. They can also integrate intersubjective agreement gradients and longitudinal stability checks correcting for both temporary reactance and consistency across repeated exposures.

3.2. The Claim Robustness Index

We develop the Claim Robustness Index (CRI) as a novel diagnostic measurement instrument to quantify the findings

following the implementation of the ACRD approach. Let us introduce the

definitions regarding the components of claim evaluations needed to construct

the CRI formula:

Initial judgments by each player: for i =1,2. Baseline partisan bias is the outcome of optimized strategic behavior. A value of 1 means that statement P is accepted as 100% valid.

Post-judgment after reframing: for i =1,2. Stress-tested beliefs et re-evaluations of these beliefs as the outcome of strategic behavior identified in the Nash equilibrium.

Expert signal: D . Grounding claim validity.

The CRI formula is:

CRI = Min (Agreement Level x Expert Alignment x Updating Process x Temporal Stability, 1)

Where:

Agreement Level: . Rewards post-reframing consensus building.

Expert Alignment: . Rewards final proximity towards expert consensus.

Updating Process: This rewards movement of revised evaluations due to adversarial collaboration.

Where:

d* = |J₁* - J₂*|: Initial disagreement.

ΔJᵢ = |Jᵢ** - Jᵢ*|: Belief update for Player i.

d** = |J₁** - J₂**|: Post-collaboration disagreement.

, ∈ [0, 1]: Weight assigned to Player 1 (due to latency of the original speaker tied to Player 1, i.e., , and the relative distance from expert consensus proxying for initial bias).

The value of UP ∈ [1, 1.4] and thus allows for a positive overcorrection in the instance of a major shift in updated beliefs.(The values of 0.4 and 1.4 in the UP formula are for illustrative purpose. These values can be changed and generalized.)

Temporal Stability: Measures stability across trials. For instance, using intraclass correlation (Shrout & Fleiss, 1979).

The CRI value range is the interval [0,1]. A higher value of the CRI index is interpreted in our framework as giving more validity credence to the claim. A high CRI value reflects several factors: 1) convergence to an agreement regarding the validity of P and/or 2) more acceptance of the expert’s consensus and/or 3) the ability and/or willingness of players to change their mind about their prior validity assessment when faced with the adversarial collaboration stage.

A Numerical Example:(In

Appendix A, we analyze a series of key numerical scenarios. )

Parameters

| Variable |

Value |

Description |

| J₁* |

0.6 |

Initial judgment of Player 1 |

| J₂* |

0.4 |

Initial judgment of Player 2 |

| J₁** |

0.64 |

Post-reframing judgment of Player 1 |

| J₂** |

0.44 |

Post-reframing judgment of Player 2 |

| D |

0.8 |

Expert signal |

|

0.5 |

Bias adjustment parameter |

1. Compute disagreements & updates

Initial disagreement: d* = |0.6 - 0.4| = 0.2

Post reframing disagreement: d** = |0.64 - 0.44| = 0.2

Belief updates:

∆J₁ = |0.64 - 0.6| = 0.04

∆J₂ = |0.44 - 0.4| = 0.04

2. Compute the weight α

α = (|0.6 - 0.8| + 0.5)/(|0.6 - 0.8| + |0.4 - 0.8| + 1)

= (0.2 + 0.5)/(0.2 + 0.4 + 1) = 0.7/1.6 = 0.4375

3. Compute UP (unbounded intermediate value)

UP unbounded = (1/0.4375) × (0.4375×0.04/0.2 + 0.5625×0.04/0.2 + 0.4) × (1 - 0.2/1.2)

= 2.2857 × (0.0875 + 0.1125 + 0.4) × 0.8333

= 2.2857 × 0.6 × 0.8333 ≈ 1.142

4. Apply Min/Max clamping to UP

Since 1 < 1.142 < 1.4, UP remains at 1.142 (no clamping needed)

5. Compute the CRI

CRI = Min (Agreement × Expert Alignment × UP × Temporal Stability, 1)

Agreement Level = 1 - |0.64 - 0.44|/2 = 0.9

Expert Alignment = 1 - (|0.64 - 0.8| + |0.44 - 0.8|)/2 = 0.74

Temporal Stability = 1

CRI = 0.9 × 0.74 × 1.142 × 1 ≈ 0.76 < 1

Summary

| Metric |

Value |

Interpretation |

| UP |

1.142 |

Moderate belief updating (rewarded but not extreme) |

| CRI |

0.76 |

Suboptimal robustness (remaining disagreement and imperfect expert alignment) |

Analysis

1. UP = 1.142 (Between 1 and 1.4)

- The players updated their beliefs slightly (∆J₁ = ∆J₂ = 0.04), but not enough to trigger clamping.

- The disagreement remained unchanged (d* = d** = 0.2), limiting the UP boost.

2. CRI = 0.76 (< 1)

- Low Expert Alignment (0.74): Both players remained far from the expert signal (D = 0.8).

- Moderate Agreement (0.9): Some consensus improvement, but not full alignment.

- UP (1.142) helped but was not enough to push CRI to 1.

Conclusion: This case demonstrates the trade-off between updating effort and final claim robustness.

4. Modeling Strategic Interactions: ACRD as a Claim Validation Game

In this section, we are setting up a simple normal form game that will analyze the choice of strategic evaluations of claim P by two players in the Baseline and Reframing phases of the ACRD protocol. We formalize the strategic choices of each player, as this allows us to infer certain behavioral properties in the response choices of evaluators we can expect to see rising to the surface in actual field experiments. Here is the proposed framework(We are well aware that the specific modeling assumptions made here may limit the generalization of these conclusions to concrete field applications.):

4.1. The Game Setup

A Statement P is uttered by Speaker 1 and needs evaluating by two players.

Players: Two players, i = 1, 2

Strategy Space: Ji ∈ [0,1] (judgment of P’s validity)

Expert Signal: D ∈ [0,1] (scientific consensus estimate of truth value ∈ [0,1] that is unobserved)

Trust in Expert by Player i: TRUSTi ∈ [0,1]

Prior Beliefs: TIEi ∈ [0,1]

We assume that the initial evaluation for Player i is measured by the strength of the tie or ideological affiliation of Player i with Speaker i: (higher value means stronger tie of Player i with Speaker i). This evaluation could be based on group consensus with or without scientific evidence.

Posterior Beliefs:

Player 1: X₁ = (1-TRUST₁)×TIE₁ + TRUST₁×D

Player 2: X₂ = (1-TRUST₂)×(1-TIE₂) + TRUST₂×D

These are evaluation updates of validity judgments based on having gone through the adversarial collaboration stage and learned about the expert’s signal before that. Players now imagine that instead of Speaker 1, it is Speaker 2 that spoke P, or that Speaker 2 takes the ~P or contrary position.(If it is the ~P proposition that is assessed the game would be redefined using that proposition as the unit of analysis for the adversarial reframing.) They realize some level of speaker neutrality (as P is viewed as truly emanating for Speaker 1, but there is room for Speaker 2 to have said it). Each Player i would a priori evaluate the claim based on his/her ideological ties with Speaker i and also account for the information received about the expert’s signal. Given that statement P is uttered by Speaker 1, this creates an asymmetry in the updated evaluations. Player 1 will focus on his/her ties with the speaker, and Player 2 will focus on the fact that the statement is NOT tied to Speaker 2 a priori. As a result of adversarial collaboration, Player 2 will still update his/her beliefs towards the scientific consensus though as seen in the formulation of posterior beliefs.

The final evaluation is Ji, which is the result of a strategic decision by Player i, who maximizes his/her payoff. The adversarial collaboration process will influence the choice of Ji and attenuate the effects of the perceived partisanship by the other.

Total Payoffs: Payoff i = COLLABi + TIEi - DISSENTi

Payoff Components:

Collaboration: COLLABi = 1-a×TIEj×(1-TIEj)×(Ji-Jj)² with a ∈ [0,1]

Cost of Dissenting: DISSENTi = Fi×TIEi, where Fi = b×(Ji-Xi)² with b ∈ [0,1]

The payoff depends on these three components. The first component comes from collaboration. Players gain from collaborating, that is, having their evaluation converge towards an agreement. In the COLLAB function, they give more weight to the other player’s tie (to their ideological speaker) at low levels and discount these ties at high levels. This modeling assumption characterizes a feature of adversarial collaboration process that there can be sympathy for the other side’s point of view only when ideological ties are not too extreme. The second component TIE represents the utility derived from association with group identity. The third component DISSENT is a cost that is subtracted from the utility of belonging to one’s ideological group and which is related to a change of opinion away from the posterior belief. This represents the cost of dissenting from what the ideological group would consider a fair evaluation.

Interpretation of Payoff Dynamics.

| Scenarios |

Expected effects on Ji |

Proximity to Expert (D) |

| High TRUSTi, Low TIEi |

Ji ≈ D |

Strong |

| Low TRUSTi, High TIEi |

Ji ≈ TIEi |

Weak |

| Moderate TIEj |

Convergence to consensus |

Moderate |

| High b (Dissent Cost) |

Ji ≈ Xi |

Depends on TRUSTi |

Key Takeaways: Truth-seeking dominates when TRUSTi is high and TIEi is low accompanied with significant dissent cost (b). Ideological rigidity dominates when TIEi is high and TRUSTi is low and collaboration incentives are weak (extreme TIEj and low parameter a).

4.2. The Bayesian-Nash Equilibrium Solution

The game introduced above has a single pure-strategy Bayesian-Nash Equilibrium (see proof in

Appendix B). The equilibrium is a pair of evaluations (J₁*, J₂*) that satisfy the usual Nash conditions: J₁* is the best response of Player 1 given J₂* played by Player 2, and vice-versa. The game satisfies a Bayesian updating (although a very simplistic one here) since the learning update necessitates a recalibration of the beliefs inputs Xi in the optimal strategies.

The equilibrium solution is:

| J₁* = [aTIE₂²(1-TIE₂)X₂ + bTIE₁(aTIE₁(1-TIE₁) + bTIE₂)X₁] / [aTIE₂²(1-TIE₂) + aTIE₁²(1-TIE₁) + bTIE₁TIE₂] |

| J₂* = [aTIE₁²(1-TIE₁)X₁ + bTIE₂(aTIE₂(1-TIE₂) + bTIE₁)X₂] / [aTIE₁²(1-TIE₁) + aTIE₂²(1-TIE₂) + bTIE₁TIE₂] |

Key Properties: The two optimal strategies (J₁*, J₂*) are weighted average of expert consensus and ideological loyalty. Collaboration pressure (a) vs truth-seeking (b) tradeoff. High TIEi values increase resistance to opinion change. Some special boundary cases:

| Case |

Condition |

Equilibrium |

| No Collaboration |

a = 0 |

Ji* = Xi |

| No Dissent Cost |

b = 0 |

Ji* = Weighted average of Xj |

Example of a Symmetric Equilibrium: J₁**= J₂**

Parameters

| Parameter |

Description |

Value |

| a |

Collaboration weight |

0.8 |

| b |

Dissent cost weight |

0.2 |

| TIE₁ |

Player 1’s ideological tie |

0.6 |

| TIE₂ |

Player 2’s ideological tie |

0.4 |

| TRUST1= TRUST₂ |

Trust in experts |

0.5 |

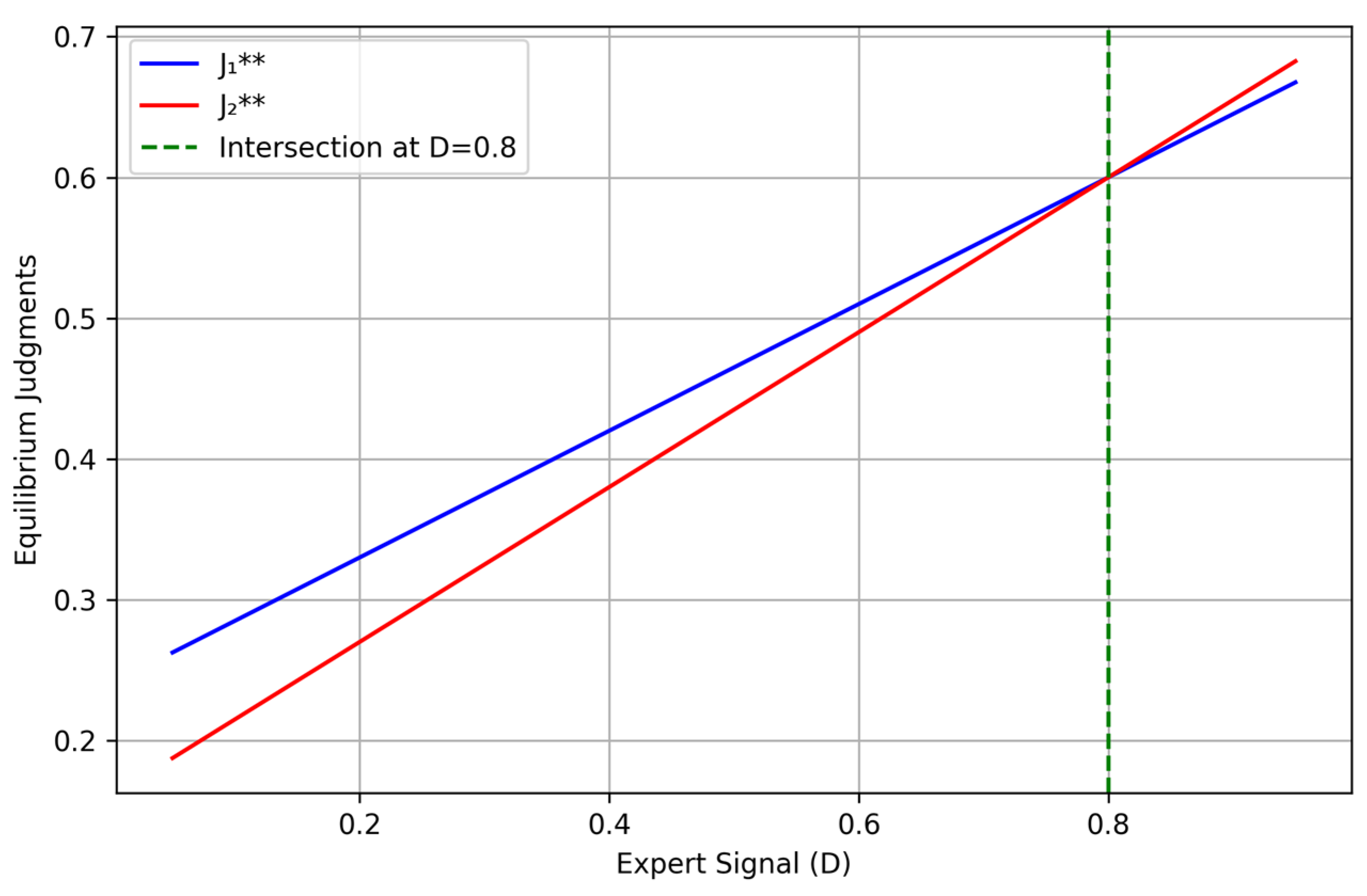

Equilibrium Judgments

| Judgment |

Equation |

| J₁** |

0.24 + 0.45D |

| J₂** |

0.16 + 0.55D |

Here, the symmetric equilibrium is achieved for a specific value of D:

Set J₁**= J₂**:

0.24 + 0.45D = 0.16 + 0.55D

Solve for D:

0.1D = 0.08 ⇒ D = 0.8

Key Insights: Here, collaboration is highly valued (a = 0.8) and thus it incentivizes consensus. Reduced dissent cost (b = 0.2) allows flexibility in belief updates. Asymmetric ideological ties (TIE1 = 0.6 and TIE2 = 0.4) impact differentiated responsiveness.

Strategic Impact: Player 2 (weaker ideology) responds more strongly to D, while Player 1 maintains moderate alignment. Consensus occurs at D*=0.8 demonstrating effective adversarial collaboration. This configuration showcases a strong scientific consensus and lower evaluations that respect ideological constraints.

Figure 1.

Equilibrium judgments as functions of expert signal D.

Figure 1.

Equilibrium judgments as functions of expert signal D.

4.3. Application of the CRI Index.

Let us now compute the CRI index based on the solutions to the strategic game, so that we can integrate these two layers of analysis. Here is another example of computed solutions:

| J₁* (TIE1) |

0.8 |

| J₂* (TIE2) |

0.2 |

| J₁** |

0.62 |

| J₂** |

0.38 |

| D |

0.5 |

| β |

0.6 |

Calculation Steps:

Agreement Level: 1 - |0.62-0.38|/2 = 0.88

- i.

Expert Alignment: 1 - (|0.62-0.5|+|0.38-0.5|)/2 = 0.88

- ii.

Updating Process:

d* = 0.6, ΔJ₁=0.18, ΔJ₂=0.18, d**=0.24

α = (0.3+0.6)/(0.3+0.3+1) = 0.5625

UP = Min (Max (1.777× [0.168+0.131+0.4] ×0.85,1),1.4) = 1.0

- iii.

Temporal Stability: Assumed ICC = 0.9

Final CRI= Min (0.88×0.88×1.0×0.9,1) = 0.7

In this example, we obtain a moderate validity score (CRI=0.7) because players only achieve a partial consensus. There is limited belief updating despite the presence of adversarial collaboration. Here, we have assumed stable evaluations across trials over time.

5. Comparative Analysis: ACRD vs. GBM and BTS Frameworks

The Adversarial Claim Resilience Diagnostics (ACRD), Gateway Belief Model (GBM) (van der Linden et al., 2021, and Bayesian Truth Serum (BTS) (Prelec, 2004) are alternative frameworks that offer distinct yet complementary approaches to evaluating claims in polarized contexts. ACRD focuses on stress-testing claims through adversarial reframing and AI-driven perturbations. It measures resilience via the Claim Robustness Index (CRI) based on expert alignment, belief updating with post-reframing consensus, and temporal stability. ARCD employs a three-phase process: a baseline assessment, ideological counterfactuals, and dynamic AI calibration-to quantify how claims withstand ideological opposition, using a game-theoretic model to infer how collaboration incentives and dissent costs balance out in equilibrium.

On the other hand, GBM leverages perceived scientific consensus as a heuristic for belief updating, experimentally demonstrating that exposure to expert agreement increases personal concern and policy support, although this outcome varies with trust in experts. By contrast, BTS incentivizes truthful reporting through dual-response surveys where participants earn rewards based on how their answers compare to peer predictions, creating a Bayesian Nash equilibrium that brings honest beliefs to the surface even without objective verification.

Beaver & Stanley (2021) argue that even the concept of claim “neutrality” is ideologically contestable. ACRD bypasses this by replacing neutrality with adversarial convergence: claim validation is a Nash equilibrium where each group benefits from reexamining a claim under counterfactual attribution. A claim like “Tax cuts increase deficits” may achieve resilience (high CRI score) only when both progressives and conservatives agree in spite of and thanks to the adversarial framing that encourages claim resilience.

While all three frameworks incorporate game theory and quantitative metrics, they diverge in their core mechanisms. ACRD intends to actively disrupt affective biases through neural noise injections and semantic perturbations, making it suited for high stakes debates like climate denial. GBM applies better in the context of broad public communication strategies and to correct misperceptions in low-trust environments across various issues (climate, vaccines, GMOs, nuclear power). It finds its sweet spot in direct applications to science communication campaigns that emphasize scientific consensus as an entry point for possible belief updating. On the other hand, BTS principles excel in information markets, preference elicitation, and prediction aggregation, offering value in contexts where objective truth is unknown or unverifiable.

These three frameworks’ mathematical models reveal fundamental tradeoffs- ACRD’s equilibrium judgments weigh expert consensus against ideological loyalty; GBM assumes consensus cues bypass systematic processing and BTS mathematically rewards honest-telling as a dominant strategy. Together, they provide multi-layered tools for combatting misinformation, with ACRD diagnosing claim fragility, GBM shifting public perceptions through consensus, and BTS extracting truthful signals from biased respondents under some specific behavioral assumptions.

6. AI-Augmented Adversarial Testing: Computational Implementation of ACRD

The Adversarial Claim Robustness Diagnostics (ACRD) framework utilizes artificial intelligence (AI) to automate and scale adversarial stress-testing of claims. It is undeniable that AI already has and will continue to play a greater role in our modern life (Srđević, 2025). This section outlines a proposed AI architecture of ACRD, highlighting its potential applications.

6.1. Large Language Models (LLMs) as Adversarial Simulators

Modern LLMs (e.g., GPT-4, Claude 3) can enable high-performance simulations of ACRD’s counterfactual attribution phase by:

1. Automated Speaker Swapping

Generates adversarial framings to for example test how would acceptance change if [claim] were attributed to [opposing ideologue] ?.

Uses prompt engineering to maximize ideological tension (e.g., attributing climate claims to oil lobbyists vs. environmentalists, and vice versa).

2. Semantic Shift Detection

Quantifies framing effects via:

Embedding similarity (e.g cosine distance in BERT/RoBERTa spaces) to detect rhetorical recognition. For instance, (cosine distance > 0.85 triggers CRI adjustment).

Sentiment polarity shifts (e.g., VADER or LIWC lexicons) to measure affective bias. For instance, polarity shifts >1.5 SD indicate affective bias.

Neural noise injection (Storek et al., 2023) to disrupt patterned responses and test claim stability under minor phrases perturbations such as “usually increases” vs. “always increases”.

3. Resilience Profiling

Flags high-CRI claims (hypothetical example: “Vaccines reduce mortality” maintains CRI > 0.9 across attributions).

Identifies fragile claims (hypothetical example: “Tax cuts raise revenues” shows CRI < 0.5 under progressive attribution).

The approach faces some limitations: LLM-generated attributions may inherit cultural biases (Mergen et al., 2021), which necessitate:

Demographic calibration. For example, Levay et al. (2016) control for skew in simulated responses. As Callegaro et al. (2014) explain, those who use non-probability samples (e.g., opt-in samples) “argue that the bias in samples . . . can be reduced through the use of auxiliary variables that make the results representative. These adjustments can be made with . . . [w]eight adjustments [using] a set of variables that have been measured in the survey.” (Levay et al., 2016: 13).

Human-in-the-loop validation for politically sensitive claims.

6.2. Mitigating Epistemic Risks in AI-Assisted ACRD

While AI enhances applicability and scalability, it introduces new challenges. The Adversarial Claim Robustness Diagnostics (ACRD) framework incorporates several key methodological approaches that serve distinct but complementary roles in ensuring both the reliability of its AI components and the validity of its adversarial collaboration assessments. The techniques from Goodfellow et al. (2014) regarding generative adversarial networks (GANs) and related adversarial debiasing methods primarily function as safeguards - they create self-correcting AI systems where generators and discriminators work in competition to identify and eliminate synthetic biases in the training data. Adversarial debiasing (Zhang et al., 2018; González-Sendino et al., 2024) can provide a crucial methodological foundation for reducing algorithmic bias in AI-assisted ACRD implementations. In ACRD applications, this debiasing process will occur during the initial framing generation phase, where it will scrub ideological artifacts from training data before claims enter adversarial testing. González-Sendino et al.’s (2024) extension of Zhang’s framework incorporates demographic calibration through propensity score matching, addressing sampling biases noted in survey research (Callegaro et al., 2014). This addresses fundamental input-side risks by preventing LLMs from developing or amplifying existing biases that could distort claim evaluations. Similarly, Kahneman et al.’s (2021) observations about expert overconfidence will inform the implementation of continuous feedback loops that keep the AI components from becoming stagnant or developing unbalanced perspectives.

These risk mitigation approaches work in tandem with - but are conceptually separate from - the framework’s core adversarial collaboration assessment functions derived from Mellers et al. (2001), Ceci et al. (2024), and Corcoran et al. (2023). Where the GAN and debiasing methods ensure clean inputs, the adversarial collaboration research provides the actual theoretical foundation and measurement protocols for evaluating claim robustness. Corcoran et al.’s (2023) Bayesian belief updating framework, for instance, can directly inform how the Claim Robustness Index (CRI) quantifies belief convergence, while Mellers et al.’s (2001) and Ceci et al.’s (2024) work on adversarial collaborations establishes the standards for what constitutes meaningful versus entrenched disagreement. Peters et al.’s (2025) research then bridges these two aspects by showing how such carefully constructed adversarial assessments can be deployed in real-world settings.

| Risk |

ACRD Safeguard |

Technical Implementation |

| Training data bias |

Adversarial debiasing (Zhang et al., 2018; González-Sendino et al., 2024) |

Fine-tuning on counterfactual Q&A datasets |

| Oversimplified ideological models |

Adversarial nets (Goodfellow et al., 2014) |

Multi-LLM consensus (GPT-4 + Claude + Mistral) |

| Semantic fragility |

Neural noise injection (Storek et al., 2023) |

Paraphrase generation via T5/DALL-E |

In practical implementation, this creates an integrated and layered architecture. The first layer applies techniques like GAN purification and adversarial debiasing to generate balanced, bias-controlled counterfactual framings of claims. These cleaned outputs then are fed into the second layer where they undergo rigorous adversarial testing according to established collaboration protocols, with the resulting interactions analyzed through Bayesian updating models and quantified via the CRI metric. The system essentially asks two sequential questions: first, “Is our testing apparatus free from distorting biases?” (addressed by the epistemic risk mitigation techniques), and only then “How does this claim fare under proper adversarial scrutiny?” (answered through the adversarial collaboration assessment methods).

This distinction is crucial because it separates the framework’s methodological hygiene factors from its core research functions. The GANs and debiasing processes ensure that the AI components don’t introduce new distortions or replicate existing human biases. The adversarial collaboration research then provides the actual analytical framework for stress-testing claims and measuring their resilience. Both aspects are necessary: the risk mitigation makes the assessments valid, while the collaboration protocols make them meaningful. Together, they will allow ACRD to provide both technically sound and epistemologically rigorous evaluations of claim robustness in polarized information environments.

6.3. Future Directions: Toward a Human-AI ACRD Partnership

In this section we examine a few projected trends that can be implemented after the initial testing of ARCD.

1. Dynamic Adversarial Calibration

Real-time adjustment of speaker attribution intensity based on respondent latency. in which, for instance, rejections under 500ms do signal knee-jerk ideological dismissal rather than considered evaluation. (Lodge & Taber, 2013).

3. Deliberative Democracy Integration

AI transforms ACRD from a theoretical protocol into a deployable tool for combatting misinformation. In that context, it seems desirable to impose some basic oversight constraints as there could be differences in AI and human prioritization (Srđević, 2025). Hence, we must avoid a situation where LLMs would function completely outside of the purview of human judgment and ethics.(The Ouroboros Model (Thomsen, 2022) is a biologically inspired cognitive architecture designed to explain general intelligence and consciousness through iterative, self-referential processes. By grounding cognition in iterative, self-correcting loops and structured memory, it addresses challenges like transparency and bias. It emphasizes plurality, the all-importance of context, and striving for consistency. Thomsen argues that in the model, except within the most strictly defined contexts, there however is no guaranteed truth, no “absolutely right answer”, and no unambiguous “opposite”.) By automating adversarial stress tests while preserving human oversight, ACRD maps out a path for identifying epistemic resilience in polarized discourse.

7. Empirical Validation and Discourse Epistemology: Testing ACRD in Real-World Discourse

The Adversarial Claim Robustness Diagnostics (ACRD) framework is designed for rigorous empirical application. ACRD can provide added value as a diagnostic tool in political communication, in traditional fact-checking, and in addressing the current challenges in public discourse epistemology.

7.1. ACRD vs. Traditional Fact-Checking: A Comparative Analysis

The Adversarial Claim Robustness Diagnostics (ACRD) framework operationalizes a systematic, empirically-grounded approach to evaluating claim resilience in polarized information environments. Unlike traditional fact-checking paradigms that suffer from well-documented weaknesses including the source credibility bias (Liu et al., 2023) -- where corrections from ideologically opposed outlets are often rejected-- and the backfire effect (Nyhan & Reifler, 2010). ACRD is designed to implement a multi-layered validation protocol combining game-theoretic modeling with AI-enhanced adversarial testing.(There are other approaches for trying to mitigate these effects. The Devil’s Advocate Approach (Vrij et al., 2023) that we use here, the Cognitive Credibility Assessment (Vrij, Fisher, & Blank, 2017; Vrij, Mann et al., 2021), the Reality Interviewing approach (Bogaard et al., 2019), the Strategic Use of Evidence (Granhag & Harwig, 2015; Hartwig et al., 2014) and the Verifiability Approach (Nahari, 2019; Palena et al., 2021) are some examples of key strategies developed in the literature.) The framework tackles fundamental challenges in public discourse through several solution mechanisms:

| Failure Mode |

Fact-Checking Approach |

ACRD Solution |

| Backfire effects (Nyhan & Reifler, 2010) |

Direct correction |

Adversarial reframing (e.g., presenting a climate claim as if coming from an oil lobbyist) |

| False consensus (Kahan et al., 2012) |

Assumes neutral arbiters exist |

Measures divergence under adversarial attribution |

| Confirmation bias (Nickerson, 1998) |

Relies on authority cues |

Strips speaker identity, forcing content-based evaluation |

At its core, ACRD circumvents the false consensus effect (Kahan et al., 2012) by incorporating expert-weighted credibility assessments into its Claim Robustness Index (CRI), while neural noise injection techniques (Storek et. al, 2023) mitigate speaker salience overhang. The system’s ability to preserve nuanced evaluation is achieved through Likert-scale rationales (Sieck & Yates, 1997), and adversarial fatigue is minimized via real-time calibration of attribution intensity based on cognitive load indicators. These technical solutions collectively address the critical failure modes of conventional verification approaches.

Consider the case of climate policy evaluation. A traditional fact-check might directly challenge the statement “Renewable energy mandates increase electricity costs” with counterevidence, often triggering ideological reactance. ACRD would instead subject this claim to rigorous stress-testing through AI-generated counterfactual framings - first presenting it as originating from an environmental NGO to conservative evaluators, then possibly presenting it as originating from a fossil fuel industry position to progressive audiences, or presenting the same audiences with the negative proposition as if spoken by the same fossil fuel top exec. The GPT-4 powered analysis would track semantic stability through BERT embeddings while monitoring sentiment shifts using VADER lexicons. The resulting CRI score would reflect the claim’s epistemic resilience across these adversarial conditions, with high scores indicating robustness independent of source attribution.

Similarly, for trade policy assertions like “Tariffs protect domestic manufacturing jobs,” ACRD’s Bayesian-Nash equilibrium modeling would simulate how different ideological groups (e.g., protectionists vs. free trade advocates) update their validity assessments when the statement is artificially attributed to opposing camps. The Claude 3 component would generate ideologically opposed reformulations while maintaining semantic equivalence, allowing measurement of pure framing effects.

This approach operationalizes Habermasian ideal speech conditions (Habermas, 1984) by forcing evaluators to engage with claim substance rather than source characteristics. Habermas’s (1984) communicative rationality assumes discourse is free of power imbalances—a condition rarely met in reality. Habermas’s communicative rationality emphasizes the equal importance of the three validity dimensions, which means it sees the potential for a) rationality in normative rightness, b) theoretical truth and c) expressive or subjective truthfulness. ACRD offers a method tending toward this ideal by:

Forcing adversarial engagement: By attributing claims to maximally oppositional sources, ACRD mimics the “veil of ignorance” (Rawls, 1971), as much as possible disrupting tribal cognition.

Dynamic calibration: Real-time adjustment of speaker intensity (e.g., downgrading adversarial framing if response latency suggests reactance).

The ACRD framework incorporates robust psychological safeguards against misinformation. Drawing from inoculation theory (Roozenbeek & van der Linden, 2019), ACRD can expose participants to graded adversarial challenges, functioning as a cognitive vaccine against ideological distortion. For cognitively complex claims like “Carbon pricing reduces emissions without harming economic growth,” the system can dynamically adjust testing parameters based for instance on the evaluator’s measured Cognitive Reflection Test (CRT) performance. ACRD can then present simplified choices to low-CRT individuals while maintaining nuanced scales for more reflective participants.

ACRD’s game-theoretic foundation addresses the “neutral arbiter” fallacy (Beaver & Stanley, 2021) by reconceptualizing validity assessment as a Nash equilibrium outcome. In this model, a claim achieves epistemic validity when it maintains high CRI scores across multiple adversarial framings, indicating that neither ideological group gains strategic advantage from rejecting it. For instance, the statement “Vaccine mandates would reduce seasonal flu mortality in nursing homes” might achieve equilibrium (CRI > 0.8) when both public health advocates and libertarian skeptics converge on its validity despite hostile source attributions.

The system’s AI components play several critical roles. During the initial phase, GPT-4 generates counterfactual framings while adversarial debiasing techniques (Zhang et al., 2018; González-Sendino et al., 2024) scrub the outputs of algorithmic bias. The dynamic calibration module then adjusts testing intensity based on real-time indicators including response latency and semantic similarity scores. Finally, the Bayesian belief updating system (Corcoran et al., 2023) aggregates results into comprehensive resilience profiles.

ACRD mitigates pitfalls of traditional adversarial testing through these embedded safeguards:

| Challenge |

ACRD Solution |

Theoretical Basis |

| False consensus |

Expert-weighted CRI |

Kahan et al. (2012) |

| Speaker salience overhang |

Neural noise injection |

Storek et al. (2023) |

| Nuance collapse |

Likert-scale writing rationale |

Sieck & Yates (1997) |

| Adversarial fatigue |

Real-time calibration of attribution intensity |

Nyhan & Reifler (2010) |

7.2. Limitations and Future Directions

The ACRD framework faces some limitations. The first limitation is the use of potential cultural boundary conditions. Here, we assume a baseline shared epistemology that may fail in hyper-polarized contexts (e.g., flat-earth communities). The second limitation is computational intensity and access to AI resources to conduct real-time adversarial calibration, which require AI infrastructure and power (e.g., GPT-4 for counterfactual generation). The third is about longitudinal effects: Does adversarial testing induce fatigue over time? Pilot studies often experience decay effects necessitating spaced testing protocols.

Another key challenge is related to the efficacy of the adversarial framing phase— particularly when testing claim robustness through counterfactual attribution— is that the believability of a claim may be distorted by priors regarding who the attributed speaker is. For instance, an environmental claim attributed to an oil executive may trigger reflexive skepticism due to perceived bias, while the same claim from a neutral scientist might appear more credible, regardless of the claim’s proper empirical merit. This introduces noise in the ACRD’s resilience metrics, as ideological priors (Lodge & Taber, 2013) and affective reactions (Westen et al., 2006) can overshadow rational updating. In that respect, dynamic calibration such as downgrading adversarial framing if response latency suggests reactance is already embedded in the AI process and provides a partial although incomplete solution. The ACRD’s game-theoretic and AI-driven phases offer a pathway, though experimental validation is needed to ensure that ideological reframing elicits epistemic refinement, not just partisan backlash.

Lastly, the main limitation, which in this case, constitutes a future opportunity, is that this article only lays out a conceptual framework without any actual on-the-ground test or experimentation. The next natural step is to conduct pilot testing with media partners (e.g., embedding CRI scores in fact-checks) and proceed to do algorithmic refinements to reduce potential bugs and biases. Typically in the pilot testing process we would have three phases:

Phase 1: Lab experiments comparing ACRD vs. fact-checking for climate/economic claims.

Phase 2: Field deployment in social media moderation (e.g., tagging posts with CRI scores).

Phase 3: Integration with deliberative democracy platforms (e.g., citizens’ assemblies).

Future validation efforts will focus on three key domains: climate science assertions, economic policy claims, and public health information. ACRD is expected to outperform traditional fact-checking methods particularly for claims where source credibility dominates content evaluation. Future research directions include these longitudinal studies of adversarial testing effects and integration with deliberative democracy and other social media platforms.

ACRD’s overarching role is to diagnose resilience, not arbitrate truth. ACRD does not pretend to be engaged in a truth-seeking quest, even though it may lead us to it under some conditions yet-to-be-defined, and which are beyond the scope of the article. By stress-testing claims against ideological friction, it offers a scalable alternative to the performance of current fact-checking solutions—one that is grounded in adversarial epistemology rather than the pursuit of an ‘illusory’ neutrality.

Conclusions

“There must in the theory be a phrase that relates the truth conditions of sentences in which the expression occurs to changing times and speakers.” (Davidson, 1967: 319). Finding a speaker-independent truth assessment mechanism has been akin to searching for the Holy Grail, over the past seven decades.

The Adversarial Claim Robustness Diagnostics (ACRD) protocol introduces an innovative approach to assess claim validity in polarized societies, shifting focus from absolute truth assessment to dynamic claim robustness. ACRD innovates through a three-phases methodology grounded in cognitive science and game theory. By stress-testing propositions under counterfactual ideological conditions —through adversarial reframing (Vrij et al. 2023), and AI-powered semantic analysis—ACRD can reveal which claims maintain persuasive validity across tribal divides. The framework’s key innovation, the Claim Robustness Index (CRI), synthesizes intersubjective agreement, expert consensus, and temporal stability into a quantifiable resilience metric that can outperform traditional fact-checking in contexts where source credibility biases dominate (Nyhan & Reifler, 2010; Kahan, 2017). Analyzing claim evaluation as a game where evaluators act strategically allows us to infer certain behaviors that arise as Bayesian Nash equilibria and thus provide a normative framework to calibrate AI powered solutions in the adversarial challenge phase.

It is important to underline that ACRD’s claim resilience may lead to truth-assessment, but that finding the propitious conditions such as the ones invoked in a verification game (Hintikka, 1962), is beyond the scope of this article. While promising, ACRD confronts a few challenges: its effectiveness assumes minimal shared epistemic foundations, potentially faltering in hyper-polarized environments; without careful debiasing, LLM-based implementations risk amplifying training data biases (Mergen et al., 2021); and real-world deployment requires balancing computational scalability with human oversight. Yet, there is an enormous field of potential applications. ARCD can tackle very current and hot societal debates ranging from climate science and policy communication to election integrity claims. We argue here that the ACRD tool has a unique capacity to identify claims capable of penetrating ideological filters. What emerges is not a solution to polarization, but a rigorous method for mapping the contested epistemic terrain. ACRD is a contribution in the direction toward rebuilding shared factual foundations in too-often fractured societies.

Looking ahead, ACRD’s true value may lie in operationalizing validity-seeking as a continuous adversarial process rather than a declarative ‘truth’ endpoint. As both AI systems and human cognition evolve in our information ecosystem, the framework’s iterative, game-theoretic approach offers a flexible toolkit for navigating post-truth challenges. Future implementations could range from browser plugins flagging resilient claims on social media to deliberative democracy tools pre-testing policy proposals—not to eliminate disagreement, but to distinguish durable facts from pure tribal posturing. In an age where epistemic collapse threatens democratic institutions, ACRD provides not a solution, but a sophisticated diagnostic to help rebuild a shared-consensus reality.

Appendix A

CRI Intermediate Scenarios Analysis

| Scenario |

Agrmt |

Expert Aligmnt |

UP Range |

CRI Range |

Behavior |

| Polarized Stubbornness |

0.4–0.5 |

0.3–0.4 |

1.0–1.1 |

0.12–0.20 |

Players maintain entrenched positions despite expert evidence (e.g., J₁**=0.1, J₂**=0.9, D=0.5). High initial disagreement (d*=0.8) persists (d**≈0.7), with minimal updates (ΔJᵢ<0.1). |

| Partial Expert Misalignment |

0.7–0.8 |

0.5–0.6 |

1.1–1.2 |

0.35–0.50 |

Moderate consensus (J₁**=0.6, J₂**=0.7) but systematic deviation from expert signal (D=0.5). Updates (ΔJᵢ≈0.2) show partial responsiveness to evidence. |

| Temporary Alignment |

0.8–0.9 |

0.6–0.7 |

1.0–1.1 |

0.45–0.60 |

Surface-level agreement (J₁**=J₂**=0.7) with expert misalignment (D=0.5). High agreement masks instability (TStability=0.7) from non-evidence-driven updates. |

| Overcorrection Without Consensus |

0.5–0.6 |

0.4–0.5 |

1.3–1.4 |

0.25–0.35 |

Aggressive updates (ΔJ₁=0.4, ΔJ₂=0.3) push players past expert consensus (J₁**=0.7, J₂**=0.3, D=0.5). High UP reflects reactive adjustments. |

| Expert-Driven but Divided |

0.3–0.4 |

0.7–0.8 |

1.2–1.3 |

0.25–0.35 |

Strong individual alignment (J₁**=0.6, J₂**=0.4, D=0.5) but persistent disagreement (d**=0.2). Updates (ΔJᵢ≈0.3) reflect evidence adoption without reconciliation. |

| Biased Collaboration |

0.6–0.7 |

0.4–0.5 |

1.1–1.2 |

0.25–0.40 |

Consensus forms around one player’s biased view (J₁**=0.6, J₂**=0.55, D=0.5) due to asymmetric α weighting (α≈0.8). Imbalanced influence in updates (ΔJ₁≈0.1, ΔJ₂≈0.3). |

| Fragile Consensus |

0.7–0.8 |

0.5–0.6 |

1.0–1.1 |

0.35–0.50 |

Nominal consensus (J₁**=0.65, J₂**=0.7, D=0.5) with weak expert alignment. Low stability (TStability =0.6) makes outcomes vulnerable to minor changes. |

Critical Observations

• UP values below 1.2 indicate limited belief revision, while UP >1.3 indicate a strong correction

• Expert alignment below 0.5 creates CRI ceilings regardless of agreement levels

• Temporal stability (not shown here) acts as a multiplier on final CRI scores

Appendix B

Proof: Characterization and Uniqueness of the Bayesian-Nash Equilibrium

1. Payoff Function Specification

Player 1 Payoff: π₁ = [1 - a×TIE₂(1-TIE₂)(J₁-J₂)²] + TIE₁ - [b×TIE₁(J₁-X₁)²]

where X₁ = (1-TRUST₁)TIE₁ + TRUST₁D

Player 2 Payoff: π₂ = [1 - a×TIE₁(1-TIE₁)(J₂-J₁)²] + TIE₂ - [b×TIE₂(J₂-X₂)²]

where X₂ = (1-TRUST₂)(1-TIE₂) + TRUST₂D

2. Monotonicity and Concavity of Payoff

∂π₁/∂J₁ = -2a×TIE₂(1-TIE₂)(J₁-J₂) - 2b×TIE₁(J₁-X₁) > 0 0 for low values of J₁.

∂π₂/∂J₂ = -2a×TIE₁(1-TIE₁)(J₂-J₁) - 2b×TIE₂(J₂-X₂) > 0 for low values of J₂.

∂²π₁/∂J₁² = -2a×TIE₂×(1-TIE₂) - 2b×TIE₁ < 0 always

∂²π₂/∂J₂² = -2a×TIE₁×(1-TIE₁) - 2b×TIE₂ < 0 always

3. First Order Conditions

For Player 1: ∂π₁/∂J₁ = -2a×TIE₂(1-TIE₂)(J₁-J₂) - 2b×TIE₁(J₁-X₁) = 0

For Player 2: ∂π₂/∂J₂ = -2a×TIE₁(1-TIE₁)(J₂-J₁) - 2b×TIE₂(J₂-X₂) = 0

4. Best Response Functions

Player 1 Best Response: J₁ = [a×TIE₂(1-TIE₂)J₂ + b×TIE₁X₁]/[a×TIE₂(1-TIE₂) + b×TIE₁]

Player 2 Best Response: J₂ = [a×TIE₁(1-TIE₁)J₁ + b×TIE₂X₂]/[a×TIE₁(1-TIE₁) + b×TIE₂]

5. Nash Equilibrium via Cramer’s Rule

System in Matrix Form:

[a×TIE₂(1-TIE₂)+b×TIE₁ -a×TIE₂(1-TIE₂)] [J₁] = [b×TIE₁X₁]

[ -a×TIE₁(1-TIE₁) a×TIE₁(1-TIE₁)+b×TIE₂] [J₂] = [b×TIE₂X₂]

Let:

k₁ = a×TIE₂(1-TIE₂), d₁ = b×TIE₁

k₂ = a×TIE₁(1-TIE₁), d₂ = b×TIE₂

Matrix Determinant: det(A) = (k₁+d₁)(k₂+d₂) - k₁k₂ = d₁k₂ + d₂k₁ + d₁d₂

Equilibrium Solution for J₁: J₁* = [d₁X₁(k₂+d₂) + k₁d₂X₂]/det(A)

Equilibrium Solution for J₂: J₂* = [k₂d₁X₁ + d₂X₂(k₁+d₁)]/det(A)

6. Uniqueness of Equilibrium: Hessian Analysis

Second Derivatives:

∂²π₁/∂J₁² = -2k₁ - 2d₁ < 0; ∂²π₂/∂J₂² = -2k₂ - 2d₂ < 0

Cross-Partial Derivatives:

∂²π₁/∂J₁∂J₂ = 2k₁; ∂²π₂/∂J₂∂J₁ = 2k₂

Negative Definiteness Conditions:

1. -2k₁-2d₁ < 0 (always true)

2. det(H) = 4(k₁+d₁)(k₂+d₂) - 4k₁k₂ > 0 (always true)

References

- Adams, M.; Niker, F. Niker, F., Bhattacharya, A., Eds.; Harnessing the epistemic value of crises for just ends. In Political philosophy in a pandemic: Routes to a more just future; Bloomsbury Academic, 2021; pp. 219–232. [Google Scholar]

- Altenmüller, M. S.; Wingen, T.; Schulte, A. Explaining polarized trust in scientists: A political stereotype-approach. Science Communication 2024, 46(1), 92–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Argyle, L. P.; Busby, E. C.; Fulda, N.; Gubler, J. R.; Rytting, C.; Wingate, D. Out of one, many: Using language models to simulate human samples. Political Analysis 2023, 31(3), 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Austin, J. L. How to do things with words; Oxford University Press, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Beaver, D.; Stanley, J. Neutrality. Philosophical Topics 2021, 49(1), 165–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berger, P. L.; Luckmann, T. The social construction of reality: A treatise in the sociology of knowledge; Anchor Books, 1966. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaard, G.; Colwell, K.; Crans, S. Using the Reality Interview improves the accuracy of the Criteria-Based Content Analysis and Reality Monitoring. Applied Cognitive Psychology 2019, 33(6), 1018–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohr, J. Public views on the dangers and importance of climate change: Predicting climate change beliefs in the United States through income moderated by party identification. Climatic Change 2014, 126(1-2), 217–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, W. J.; Crockett, M. J.; Van Bavel, J. J. The MAD model of moral contagion: The role of motivation, attention, and design in the spread of moralized content online. Perspectives on Psychological Science 2021, 16(4), 978–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenan, M. Americans’ trust in media remains near record low. Gallup. 18 October 2022. Available online: https://news.gallup.com/poll/403166/americans-trust-media-remains-near-record-low.aspx.

- Bugden, D.; Evensen, D.; Stedman, R. A drill by any other name: Social representations, framing, and legacies of natural resource extraction in the fracking industry. Energy Research & Social Science 2017, 29, 62–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Callegaro, M.; Baker, R.; Bethlehem, J.; Göritz, A. S.; Krosnick, J. A.; Lavrakas, P. J. Callegaro, M., Baker, R., Bethlehem, J., Göritz, A. S., Krosnick, J. A., Lavrakas, P. J., Eds.; Online panel research: History, concepts, applications, and a look at the future. In Online panel research: A data quality perspective; Wiley, 2014; pp. 1–22. [Google Scholar]

- Calvillo, D. P.; Ross, B. J.; Garcia, R. J. B.; Smelter, T. J.; Rutchick, A. M. Political ideology predicts perceptions of the threat of COVID-19. Social Psychological and Personality Science 2020, 11(8), 1119–1128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, T. H.; Kay, A. C. Solution aversion: On the relation between ideology and motivated disbelief. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2014, 107(5), 809–824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ceci, S. J.; Clark, C. J.; Jussim, L.; Williams, W. M. Adversarial collaboration: An undervalued approach in behavioral science. In American Psychologist; Advance online publication, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaiken, S.; Trope, Y. (Eds.) Dual-process theories in social psychology; Guilford Press, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Cialdini, R. B.; Kallgren, C. A.; Reno, R. R. A focus theory of normative conduct: A theoretical refinement and reevaluation of the role of norms in human behavior. Advances in Experimental Social Psychology 1991, 24, 201–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, A. Whatever next? Predictive brains, situated agents, and the future of cognitive science. Behavioral and Brain Sciences 2013, 36(3), 181–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clarke, C. E.; Hart, P. S.; Schuldt, J. P.; Evensen, D. T. N.; Boudet, H. S.; Jacquet, J. B.; Stedman, R. C. Public opinion on energy development: The interplay of issue framing, top-of-mind associations, and political ideology. Energy Policy 2015, 81, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, G. L. Party over policy: The dominating impact of group influence on political beliefs. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 2003, 85(5), 808–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, J.; Oreskes, N.; Doran, P. T.; Anderegg, W. R.; Verheggen, B.; Maibach, E. W.; Carlton, J. S.; Lewandowsky, S.; Skuce, A. G.; Green, S. A.; Nuccitelli, D.; Jacobs, P.; Richardson, M.; Winkler, B.; Painting, R.; Rice, K. Consensus on consensus: A synthesis of consensus estimates on human-caused global warming. Environmental Research Letters 2016, 11(4), 048002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corcoran, A. W.; Hohwy, J.; Friston, K. J. Accelerating scientific progress through Bayesian adversarial collaboration. Neuron 2023, 111(22), 3505–3516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darke, P. R.; Chaiken, S.; Bohner, G.; Einwiller, S.; Erb, H. P.; Hazlewood, J. D. Accuracy motivation, consensus information, and the law of large numbers: Effects on attitude judgment in the absence of argumentation. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin 1998, 24(11), 1205–1215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davidson, D. Truth and meaning. Synthese 1967, 17(3), 304–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Martino, B.; Kumaran, D.; Seymour, B.; Dolan, R. J. Frames, biases, and rational decision-making in the human brain. Science 2006, 313(5787), 684–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drummond, C.; Fischhoff, B. Individuals with greater science literacy and education have more polarized beliefs on controversial science topics. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114(36), 9587–9592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Druckman, J. N. The implications of framing effects for citizen competence. Political Behavior 2001, 23(3), 225–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]