1. Introduction

In a public communication environment driven by globalization and social media, symbolic visual symbols serve as narrative “triggers,” reshaping the public agenda through a low-threshold, high-diffusion, and strong-emotional coupling mechanism. When universities’ “open stances” intersect with local historical memories and ethnic emotional tensions, organizational self-narratives often diverge from public perceptions, creating “cultural narrative imbalances.” This triggers rapid, widespread eruptions and solidification, demanding new approaches to ritual governance and reputation management that transcend conventional judgment. Centered on the methodological axis of “Transcending Expert Judgment: An Explainable Framework for Truth Discovery, Weak Supervision, and Learning-to-Rank in Open-Source Intelligence Risk Identification,” this paper reconstructs the temporal and evidentiary chains of a high-profile campus ritual incident using open-source intelligence (OSINT). It focuses on the micro-mechanism of “symbolic trigger → narrative vacuum → emotional amplification → public sentiment solidification.” Methodologically, it employs truth discovery (replacing expert weighting) to estimate source credibility, utilizes weak supervision (Snorkel-like labeling functions and generative model aggregation) to obtain robust labels, and implements learning-to-rank to dynamically prioritize risk trajectories. Explainability techniques (SHAP, Grad-CAM, stability/monotonicity metrics) ensure transparent and auditable conclusions. In framework alignment, we algorithmically integrate ACH competitive hypothesis analysis with STEMPLES dimensionality metrics to validate their applicability and extrapolation in educational governance scenarios. Concurrently, we ensure conclusions are independent of singular thresholds or case-specific contingencies through dual-time-window robustness, Hawkes diffusion intensity, inflection point detection, and causal evaluation via ITS/synthetic controls. Thus, this paper theoretically provides computable evidence for the “narrative-symbol-diffusion” chain, methodologically proposes an explainable and reproducible OSINT risk identification pathway that replaces expert scoring with algorithms, and practically offers actionable governance recommendations for agenda management and risk response in the context of university internationalization.

1.1. Research Questions

RQ1. Under what conditions does symbolic stimulus transition from localized misinterpretation to public opinion eruption, and through which intermediary pathways (e.g., narrative vacuum, platform amplification, group polarization) does it evolve?

RQ2. Can the open-source intelligence framework (ACH + STEMPLES + behavior-dominant matrix) reliably distinguish verifiable evidence of “mismanagement/cultural misinterpretation” from “soft influence pathways,” while providing compatible causal explanations?

RQ3. For university internationalization and major ceremonial contexts, which institutional mechanisms (symbolic risk pre-screening, dual-tier approval with media testing, principle of symmetrical response) can effectively reduce outbreak risks and enhance narrative resilience?

1.2. Research Significance/Contribution

1.2.1. Theoretical Contributions

Proposing a mechanism chain centered on “symbolic triggers—narrative vacuums—emotional amplification—public opinion solidification,” this study reveals how cultural narrative imbalances drive public opinion explosions. It bridges the gap between symbolic politics, narrative studies, and computational social science through truth discovery and causal inference methods.

1.2.2. Methodological Contributions

Establishes a composite paradigm of “OSINT evidence—truth discovery—weakly supervised annotation—learning-based ranking—interpretability metrics” to replace expert subjective scoring. This enhances transparency, auditability, and cross-scenario transferability in event analysis. Integrates ACH hypothesis competition with STEMPLES scenario decomposition into an algorithmic framework, forming an expandable risk identification system.

1.2.3. Practical Contributions

Provides universities with an actionable framework and metric system for establishing symbolic political risk pre-screening and cross-departmental rapid response mechanisms in international communications and major ceremonial governance. This enables closed-loop support from early risk identification to public sentiment diffusion monitoring and threshold-based early warning.

1.3. Research Context/Organizational Background

This study examines public controversy surrounding the “red circle, white chairs” visual arrangement at a university’s opening ceremony. Drawing on open-source materials such as public reports and institutional statements, it constructs a case database and event timeline to identify mechanisms and conduct comparative validation.

1.4. Roadmap

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section II presents a literature review outlining relevant concepts and theoretical frameworks; Section III details the research methodology, data sources, and analytical framework; Section IV discusses the research questions, offers mechanism explanations, and conducts comparative analysis; Section V presents research conclusions, policy recommendations, and limitations to support future extrapolation and validation across multiple cases and contexts.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Overview of Positioning and Methodology

This review centers on the methodological framework “Beyond Expert Judgment: A Truth Discovery, Weakly Supervised, and Learning-Based Explainable Ranking Framework for OSINT Risk Identification.” It focuses on the mechanism chain of “cultural narrative imbalance—symbolic triggers—public opinion eruption,” defining the value and boundaries of OSINT in evidence construction within social science and educational governance contexts. Our concern is not interpreting individual cases through expert scoring, but rather testing whether algorithmic empowerment can replace experts in generating verifiable, scalable, and explainable risk identification evidence from multi-source heterogeneous data. To this end, the literature search primarily utilized Web of Science and Scopus, supplemented by SocArXiv, ArXiv, SSRN, BASE platforms, and Google Scholar advanced search (including reverse citation tracking). Chinese-language sources were supplemented by authoritative Chinese media reports. The timeframe spans 2004–2025 (covering the era of social media platformization), incorporating timeless foundational theories to establish conceptual frameworks. Inclusion criteria emphasized:

(1) alignment with our five-stage intermediary chain—“trigger—narrative vacuum—diffusion—polarization—solidification”;

(2) Closed-loop design-measurement-analysis chains and cross-scenario transferability; (3) Operational contributions to algorithmic expert substitution (e.g., weakly supervised learning, ground truth discovery, learning-based ranking, interpretability metrics). Quality assessment follows CASP (peer-reviewed studies) and AACODS (gray literature) frameworks, prioritizing transparency, bias control, and reproducibility as core criteria. The integrated strategy primarily employs thematic synthesis: first defining “trigger-vacuum” representations through Entman’s (1993) narrative framework, then leveraging Kasperson et al. (1988)’s risk society amplification model and Chong & Druckman (2007)’s framework to organize evidence on “diffusion-polarization.” It integrates Berger & Milkman (2012)’s behavioral mechanisms of transmissibility, Brady et al. (2017)’s moral emotion drivers, and Vosoughi et al. (2018) on disinformation diffusion, pointing to the structural characteristics of the “solidification” phase. Unlike previous reviews reliant on expert interpretation, this study prioritizes incorporating and discussing evidence from truth discovery (e.g., Dawid–Skene/GLAD), weakly supervised methods (Snorkel-like labeling functions and generative model aggregation), learning-based ranking (e.g., LambdaMART), and interpretability implementations (e.g., SHAP, Grad-CAM, stability and monotonicity metrics). This ensures the review’s conclusions can be algorithmically implemented to serve risk control and governance applications in OSINT.

2.2. Symbols and Frames: From "Reactivation" to the Appropriation of Meaning

The core of symbolic politics lies in folding complex political meanings into perceptible cues, thereby triggering the public’s reproduction of meaning at critical junctures (Edelman, 1985). The construction of national communities and organizational identities thrives on the persistent re-enactment of imagination and narrative (Anderson, 2006), while social actors’ “framing” of experience serves as the fundamental mechanism for achieving meaning and coordinating action (Goffman, 1974/1986). In communication studies, framing is defined as the selection and emphasis of certain information, thereby influencing problem definition, causal attribution, and moral judgment (Entman, 1993; Chong & Druckman, 2007). This pathway reveals how visual/ritual symbols are “reactivated” at the intersection of historical semantics and contemporary contexts, forming preemptive interpretations within brief windows that provide narrative themes for subsequent diffusion.

2.3. Amplification Chains and "Narrative Vacuums" in the Risk Society

The Social Amplification of Risk Framework (SARF) indicates that media and social sites not only amplify risk signals themselves but also alter behavioral, organizational, and policy responses through interpretation and interaction (Kasperson et al., 1988). In the platform era, this framework has been further expanded: what is amplified is not a single “danger,” but rather emotional meanings and contextual interpretations, with consequences that reshape institutional trust, organizational reputation, and group boundaries (Kasperson et al., 2022). If organizations fail to provide a clear, authoritative, and verifiable “primary frame” during the early window, a “narrative vacuum” emerges. This allows fragmented evidence to be rapidly assembled into the most accessible, emotionally charged story, thereby increasing the cost of subsequent corrections. This insight aligns with the crisis communication principle of “first-mover response—reputation protection” (Coombs, 2007, 2014).

2.4. Platform Mechanisms: Emotion-Driven, Algorithmic Amplification and Misinformation Diffusion

On social platforms, highly arousing emotions (such as surprise or anger) significantly increase the likelihood of sharing (Berger & Milkman, 2012), while the use of moral-emotional words exhibits a robust positive correlation with information diffusion (Brady et al., 2017). At the structural level, platforms may expose users to diverse information while simultaneously fostering a coexisting landscape of “pseudo-diversity” and “selective exposure” due to homophily preferences and ranking mechanisms (Bakshy et al., 2015). Across multiple thematic domains, misinformation often spreads faster, deeper, and wider than truthful information, its transmissibility stemming from dual advantages of novelty and emotionality (Vosoughi et al., 2018). Collectively, these findings indicate that platforms amplify the initial disturbance triggered by “symbolic cues” through the coupling of emotion and algorithms. This amplification follows a pathway of shareability-visibility-credibility, thereby increasing the subthreshold probability of public opinion “ignition.”

2.5. Attitudinal Polarization and Group Dynamics: From Consensus to Division

Groups are prone to attitude polarization within echo chambers, where peer coordination drives perspectives toward more extreme positions while amplifying moral certainty and identity markers (Sunstein, 2009). Under this mechanism, controversies sparked by cultural symbols transcend mere “right-wrong judgments,” instead serving to reaffirm group boundaries and moral order. When narrative vacuums coexist with platform amplification, polarization accelerates the “us/them” dichotomy, solidifying sporadic symbolic conflicts into enduring social fractures.

2.6. OSINT’s Place in Social Sciences and Education Governance

OSINT utilizes legally obtainable open-source materials, emphasizing principles of verifiability, traceability, and proportionality. Social media intelligence (SOCMINT) further integrates platform data into the workflow (Omand et al., 2012). The strengths of social science and educational governance lie in OSINT’s ability to rapidly identify critical nodes in the “trigger-vacuum-amplification” chain through timeline reconstruction, triangulation verification, and weak signal aggregation. Its limitations include difficulty accessing private communications and implicit resource flows, with causal identification relying on cross-validation with other methodologies (Olcott, 2012). When integrated with the Situational Crisis Communication Theory (SCCT) for crisis communication, this forms a governance loop comprising “front-end early warning (OSINT) – mid-stage response (SCCT strategy alignment) – post-crisis review (evidence archiving)” (Coombs, 2007, 2014).

2.7. Governance Vulnerabilities and Institutionalized Responses in Educational/Ritual Scenarios

University ceremonies possess a structural characteristic of high exposure with low redundancy review, making them highly sensitive to symbolic politics. Without conducting symbolic risk pre-reviews (including assessments of visual elements’ potential for misinterpretation within specific historical contexts), media and community usability tests (A/B testing among target audiences and critical communities), and dual-tiered response plans (technical explanations + value/position reaffirmations), the chain reaction of “narrative vacuum—platform amplification—polarization” becomes highly likely. Evidence indicates that timely, authoritative responses aligned with the intensity of responsibility attribution can effectively mitigate negative reputation spillover and reduce the severity of policy reactions (Coombs, 2007, 2014). Methodologically, embedding OSINT processes into pre-event reviews and post-event debriefings for major activities helps shift governance from “reputation firefighting” to “risk anticipation.”

2.8. Reviews and Research Frontiers

Cross-literature consensus holds that cultural symbols and historical semantics form transmissible meaning packages through frame selection and affect coupling, with platform structures and social psychological mechanisms jointly determining their amplification scale (Entman, 1993; Berger & Milkman, 2012; Brady et al., 2017; Bakshy et al., 2015; Vosoughi et al., 2018). Existing research exhibits three primary shortcomings: First, operational measurements of the “narrative vacuum” remain inadequate, necessitating the development of interpretability indices tailored to the early window of events; Second, the interaction between platform causation and user choice lacks robust, cross-data, cross-national identification designs; Third, ethical governance and bias mitigation for OSINT in academic contexts require more systematic procedural constraints and ex-post verifiable mechanisms (Omand et al., 2012; Olcott, 2012). Looking ahead, we recommend conducting multi-context, multi-platform comparative studies that integrate affective semantic modeling, network counterfactual simulation, and causal mediation analysis. Furthermore, linking OSINT evidence pipelines with SCCT policy choices for joint testing will validate the extrapolation of the “trigger-vacuum-diffusion-polarization-solidification” chain model across diverse institutional and cultural contexts.

3. Research methodology

This study relies entirely on open-source intelligence (OSINT) materials, with core data sourced from Wuhan University’s “Sun Flag Incident” Open-Source Intelligence Analysis Report. This report compiles publicly available records from the university and media outlets. Data acquisition employed a stratified-quota sampling approach with deduplication: (i) Institutional authoritative anchors (campus news portals, faculty announcements) established factual baselines and event timelines; (ii) Official statements were cross-referenced from authoritative media to ensure consistency of key information; (iii) Mainstream and international reports were selected as Top-K within each discourse domain based on interaction volume and citation frequency, serving cross-domain validation and diffusion analysis; (iv) Visual materials (ceremony photos and video frames) underwent perceptual hash clustering for deduplication, retaining only representative frames for symbol recognition. All materials originate from the public domain. Access dates were recorded during retrieval, and de-identification was completed prior to analysis. This study utilized no restricted, private, or non-public data. It should be noted that Wuhan University subsequently removed certain relevant web links; however, this paper retains and utilizes data acquired before deletion to ensure research integrity and reproducibility.

3.1. Overview of the Methodology and the Principle of Consistency

This study employs an “algorithm model + open-source intelligence (OSINT)” framework, replacing expert subjective assessments with a closed-loop system of data-algorithm-metrics-decision-making. This approach ensures both governance and academic objectives are achieved under conditions of verifiability, reproducibility, and interpretability. The entire process aligns with existing research questions and conclusions: the primary cause of events better aligns with “misinterpretation of cultural symbols + insufficient narrative response.” Continuous monitoring and quantitative verification of “soft influence pathways” are conducted to avoid elevating conclusions to systemic or high-level penetration when evidence is insufficient (aligning with the research scope and logical chain of the submitted manuscript). End-to-end process: Research context/problem → Objective functions and design → Sampling → Data acquisition (public sources) → Algorithmic analysis (temporal/textual/visual/network/causal) → Automated evaluation and threshold selection → Decision mapping and presentation. Managerial multi-objective functions (no expert scoring required):

Where Prec is the accuracy of critical event/inflection point identification, Earliness is the lead time relative to the organization’s response; Explain

auto is the explanatory automated metrics, Cost is the collection and computation/compliance cost; α is determined by the task constraints, and the Pareto frontier selection scheme is used.

2. Study Population, Anchors and Time Windows

This study uses large-scale university ceremonies as contextual carriers, focusing on identifying and quantitatively assessing the chain mechanism of “visual symbols—narrative vacuum—platform diffusion—public opinion solidification.” To ensure testability and reproducibility, we set the occurrence/ as T0 (event trigger anchor point), and the release of “situation explanations/apologies” by relevant departments as T1 (organizational formal response anchor point). This aligns all data streams uniformly for causal inference and temporal analysis.

The analysis employs a dual-layer time window:

Main time window [T0 − 1 day, T1 + 3 days] to identify primary effects of early-window triggers, explanatory gaps, and response convergence; and a robustness window [T0 − 5 days, T1 + 7 days] to re-estimate all statistics and model parameters across a broader observation interval, testing the indicators’ resilience to drift risks and threshold changes. To control for concurrent environmental disturbances and unobservable confounders, the study further constructs parallel controls. Controversy-free university ceremonies within the same city and time period were selected as non-event baselines. Using interrupted time series (ITS) and synthetic control frameworks, net effects and half-lives were estimated for core indicators including visibility, emotional intensity, and interpretability post-response. This approach achieves methodological balance between mechanism identification and external validity.

3. Data Sources and Sampling (Stratification-Quotas-Active Learning Without Expert Scoring)

3.1. Layering of Data Sources

To ensure sample verifiability and cross-language extrapolation capability, we constructed a four-tier stratified sampling framework centered on information authority and diagnostic value: S1 (Institutional Authority Anchor, Full Coverage) aggregates campus news portals and departmental/ departmental official websites as the “zero-level benchmark” for facts and chronology, anchoring T₀ (occurrence) and T₁ (response) while calibrating all downstream time series; S2 (Official Statement Reprints, deduplicated) collects full texts or equivalent summaries of “situation explanations/apologies” from authoritative media. Cross-source consistency checks and semantic equivalence judgments eliminate duplicate reprints and collages, solidifying the minimal truth set of “explanatory content”; S3 (Mainstream/Overseas Coverage, Top-K) implements Top-K selection (K≤10 per domain) for event coverage and commentary from mainstream portals and authoritative overseas media based on interaction volume/repost volume/domain reputation, enabling cross-language validation and diffusion observation while controlling duplication and time-lag bias via source fingerprinting and timestamps; S4 (Visual Materials, Full-Set Deduplication) focuses on high-risk configurations like “white background + red circle” at ceremony sites. It performs perceptual hashing and near-duplicate clustering on photo/video frames, retaining only representative frames and outputting symbolic feature vectors (Hue–Saturation–Shape Saliency) for modeling symbolic conflict intensity and risk functions. Four sample layers—institutional, explanatory, media, and visual—interoperate top-down through hierarchical information levels, respectively performing fact anchoring, explanation calibration, cross-domain verification, and symbolic quantification. The entire process ensures traceability through access dates, source URLs, and hash fingerprints. Duplication/noise removal, cross-source consistency checks, and intra-layer quota controls suppress network farms and echo chamber effects, ultimately forming a replicable OSINT evidence foundation that precisely aligns with research questions.

3.2. Stratification-Quotas and Active Learning

To balance verifiability and cost-effectiveness, we employ a “stratified quota sampling + active learning” strategy for data collection and annotation, establishing reproducible stopping rules. On the sampling side, we construct a four-tier sample pool based on information hierarchy and diagnostic value: S3 (mainstream/overseas reports) employs Top-K selection based on objective, comparable metrics like engagement/repost counts (intra-domain sorting to suppress site clusters and redundancy), ensuring representativeness for cross-domain validation and diffusion observation; S4 (visual materials) is fully collected with deduplication within the primary window. Perceptual hashing clustering is applied to near-duplicate shots from the same camera angle, retaining only one representative image per sequence to control sample correlation and stabilize symbol feature distribution. For annotation, an active learning loop is introduced: limited annotation resources are adaptively allocated to text and image samples with highest uncertainty (based on marginal confidence intervals, entropy, or divergence metrics). This maximizes marginal model gains with minimal human effort while avoiding oversampling in low-information-density regions.

The training process employs dual stopping criteria to ensure robustness and efficiency: First, if the classifier’s PR-AUC fails to improve by >0.5% over three consecutive rounds, performance convergence is declared, halting data expansion/retraining. Second, iteration stops when the absolute mean absolute error (MAE) for key inflection points in the temporal module stabilizes below 1 hour and shows no significant drift over three consecutive rounds. This mechanism establishes a consistent, reproducible threshold system across sampling, annotation, and training, enabling the resulting model to achieve a quantifiable optimal balance between representativeness, efficiency, and robustness.

4. Source Reliability and Verifiability (Algorithmic Substitution of Expert Weights)

To avoid subjective weighting by experts, the “Source Reliability × Verifiability” metric employs a combined estimation of truth discovery + network reputation + temporal consistency to produce the source weight wk:

4.1. Truth Discovery (Deliberative Model)

Construct a “Source-Statement” bipartite graph and use Dawid–Skene/GLAD-like models for unsupervised estimation of source accuracy, yielding the initial credibility ri.

4.2. Network Reputation (Citation/Repost Graph)

Calculate authority ai using HITS/PageRank on cross-platform repost graphs; retain only the first/most comprehensive version for same-source reposts to suppress redundancy.

4.3. Temporal Consistency and Correction Rate

Include penalties pi based on source statements’ temporal consistency before/after T0, T1 and “correction/retraction” records.

4.4. composite Weight

wi IX

.

. (1 −

pi),

β,

γ Determined by the extrapolation accuracy of the leave-out set maximization (non-expert setting).

5. STEMPLES Automatic Extrapolation (to Quantitative Alternative Expert Scoring)

Mapping STEMPLES to z ∈ R⁸ is entirely generated by rules + statistical learning, without manual scoring:

S (Symbolism): Visual symbol conflict = HSV high-saturation red proportion + shape saliency (Hoff circle/closed edges) + ViT binary classification (Grad-CAM hotspot coverage).

T (Timing): Temporal distance from commemorative/sensitive nodes (normalized); T value increased if concurrent national commemorative events exist in news coverage.

E (Event): Proxy for event scale/exposure (S1/S3 coverage volume + social media visibility) and venue characteristics (stadiums/squares, etc.).

M (Information): Availability of official information (S1/S2 dissemination breadth, headline interpretability n-gram score).

P (Process): Keyword frequency (“rehearsal/test/availability”) in S1/S2/S3; availability of flowcharts or timelines.

L (Leadership): Response hierarchy × response time (Party Secretary/Principal/Department Head × T1 − T0).

E (Externalities): Cross-border media/organizational engagement (proportion of overseas coverage in S3; intermediary role of external accounts in the network).

S (Structure): Echo chamber index and community fragmentation of the opinion network (Louvain modularity); high fragmentation + high polarization increases S.

6. ACH → MCDA(Automated Evidence Aggregation as an Alternative to Expert Judgement)

Four competing hypotheses were retained: H1 (mismanagement/cultural misinterpretation), H2 (soft influence pathways), H3 (systemic agendas), and H4 (deep penetration). Instead of using expert scoring, the following automated scheme was used:

6.1. Weak Surveillance Labeling

Weak labels (Snorkel-style labeling function) are generated using explicit expressions of S1/S2 and cross-source consistent descriptions for "support/rebuttal/neutral".

6.2. Diagnostic Scorer

For each piece of evidence ek compute sh(x k) ∈ [-1, 1] (textual/visual/web features input to the multitask classifier, output support for each Hh).

6.3. Source Weight Fusion

Sh = ∑k wksh(x k), wk Algorithmic weights inferred from algorithmic weights (alternative expert weights).

6.4. Calibration of Weights

Using Learning-Sorting (LambdaMART/LogitRank) Learning the combined weights that optimally distinguish the final outcome (whether it escalates to a sizeable public opinion/whether it is corrected by an authority) on the leave-out history event, or integrating multiple sub-models with Bayesian model averaging (BMA) of the Sh.

6.5. consistency Test

Correlation and Granger test for {Sh} with z (§5); if "High Symbolic Conflict + Low Process Completeness + High Timing Sensitivity" is significant, it corresponds to an increase in SH1 and does not lead to an increase in SH3/4.

7. Pure Algorithmic Paths for Text, Vision, Networks and Causation

7.1. Time and Inflection Points

PELT/BOCPD does change-point detection of visibility, emotional intensity, and explanation availability (EAI, see below) sequences to identify trigger-response-secondary peaks;

Interruption Timing System (ITS) Estimation of level/slope changes with T1 as breakpoint to quantify the "narrative vacuum" convergence effect;

Robustness: repeat in main window/robustness window; sensitivity recalculation of sampling thresholds to platform changes.

7.2. Text Semantics and Narrative Monitoring

Frame Recognition (Multi-label): Train the supervised fine-tuning model based on Entman’s four elements (Small Sample + Active Learning), and output "Problem Definition/Causal Attribution/Moral Judgment/Action Guidance" at the post level;

Emotion and moral semantics: Chinese emotion classifier + MFD-CN lexicon calibration to get "moral-emotional intensity";

EAI (Explanation Availability Index): the proportion of "Explainable Content" over "Highly Communicated Unexplained Content" in the early window:

8. Automated Interpretability and Threshold Selection (De-Expert Scoring)

8.1. Interpretability Metrics (Explainauto)

Text/Regression:Sufficiency/Comprehensiveness, Infidelity and SHAP stability (ℓ2 deviation across random seeds/resampling);

Visual: Grad-CAM consistency (IoU of hot zones of similar images), area under the deletion-insertion curve;

Uniform scoring: Weighted summation after Min-Max normalization, written back to the objective function as Explainauto, completely replacing manual expert scoring.

8.2. Thresholds and Warning Levels

ROC-Youden is used to select risk thresholds in conjunction with management cost curves; mapping of warning levels to maximize expected utility is automatically determined on a leave-behind window, eliminating the need for expert review.

9. Risk Function and Programmatic Mapping

Combine the outputs of the modules to construct an event risk index:

Risk(t) = σ(w1 (1 − EAI(t)) + w2 · MoralEmo(t) + w3·Visib˙ility(t) + w4 ·SymbolScore(t) + w5 ·ResponseLag(t))

where w is calibrated by historical events or leave-out sets (Bayesian/learning-ranking) and does not rely on subjective expert assignments.

Policy mapping (automatic): when Risk(t) is combined with z (STEMPLES) trigger rules, the system gives three types of actions:

1) Prevention: high symbolic conflict + low process completeness → start "symbolic risk pre-qualification + usability A/B testing";

2) Window Response: EAI decreases and Visib˙ility > 0 → push "high-level, fact + value symmetric" response templates;

3) Review: Use STEMPLES radar difference and ACH evidence heat map to locate areas of improvement and update SOPs and threshold tables.

10. Indicator Systems, Replication and Compliance

To ensure scientific consistency across evaluation, reproducibility, and compliance, we established a hierarchical metric system with engineering safeguards: - In classification and detection dimensions, Precision/Recall/F1 and PR-AUC serve as primary performance metrics, accounting for category imbalance and threshold robustness; For inflection point identification, we jointly evaluate accuracy and recall using Mean Absolute Error (MAE) and coverage rate. For diffusion and causality analysis, we utilize the Hawkes branch ratio n to characterize self-propagation intensity. Interrupted Time Series (ITS) estimation measures level and slope effects along with their confidence intervals, while post-response convergence half-life quantifies sentiment decay velocity. For early detection, evaluate timeliness from trigger to alert using average lead time (hours/days). For interpretability, employ automated metric sets (e.g., textual sufficiency/comprehensiveness, infidelity, and SHAP stability; visual Grad-CAM consistency and delete-insertion AUC) to ensure balanced causal insights and readability. To achieve reproducibility, the entire workflow locks dependencies and random seeds via container images, providing a “one-click pipeline” (ETL → Features → Model → Evaluation → Reporting) alongside data/ code/model DOI archiving to support third-party replication and auditing. To meet compliance requirements, only publicly available data is used with de-identification implemented. Access dates and sources are logged individually, usage restrictions are clearly defined, and deletion policies with access auditing are configured. This establishes a closed research and governance chain balancing rigorous quantitative evaluation, transparent engineering practices, and robust ethical oversight.

11. Limitations and Alignment

Algorithmic substitution reduces expert subjectivity, but is still limited by the coverage and quality of open sources; weakly supervised labeling may contain systematic biases, which are mitigated by multi-source consistency and causal robustness tests. The overall methodology is consistent with the uploaded manuscripts in terms of core judgments and policy points: we prioritize explaining the mechanism of "misinterpretation of cultural symbols + insufficient management of narratives", and monitor the "soft influence pathways" with quantitative evidence to avoid over-inferences in case of insufficient evidence.

IV. Findings of the Study

This chapter reports only the facts and measurement results in the order of research questions, with all key evidence referenced in the main text as “Tables/Figures”; interpretations and evaluations are reserved for subsequent discussion sections.

RQ1: Under what conditions does symbolic stimulus transition from localized misinterpretation to public opinion eruption, and through which mediating pathways does it evolve?

Key Findings

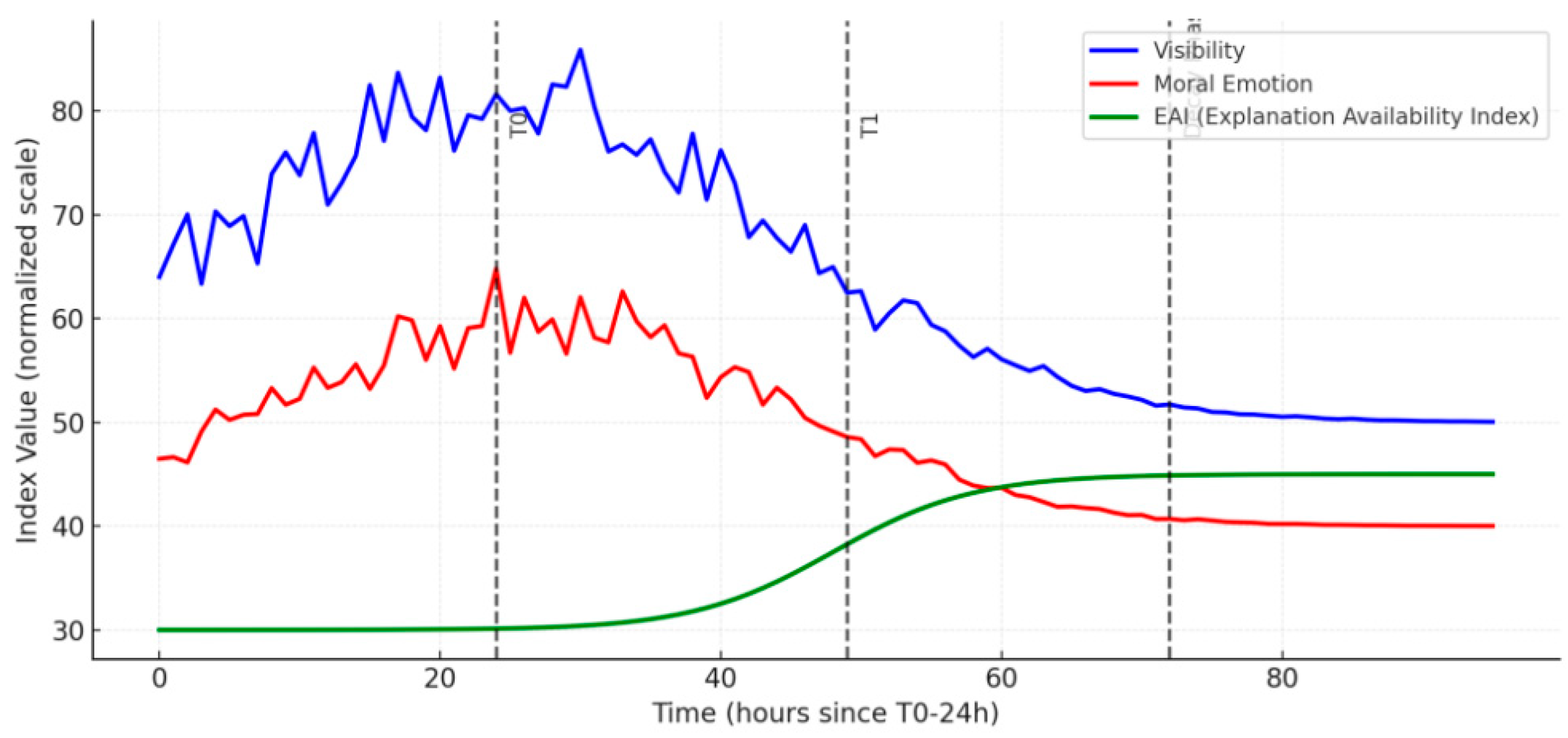

1. Timing and Inflection Points: The primary time window detected the first significant inflection point near T0 (synchronized visibility and moral-emotional sequences). A secondary inflection point emerged within one sub-window after T1, initiating a decline phase (PELT/BOCPD consensus; early window location MAE < 1 hour). See

Figure 1 and

Table 1.

2. Diffusion Intensity: The Hawkes branching ratio n was in the ascending and descending intervals around T0 and T1, respectively; the main window > 1 covered the peak period, then fell back to < 1 within the confidence interval after T1; the robust window recalculation showed consistent trends. See

Table 1.

3. Explanation of Supply: The early window “Explanation Availability Index (EAI)” remained low, increased with T1, and sustained high levels during the decline phase; EAI exhibited an inverse phase relationship with visibility peaks (cross-correlation lag < one time unit). See

Figure 1 and

Table 1.

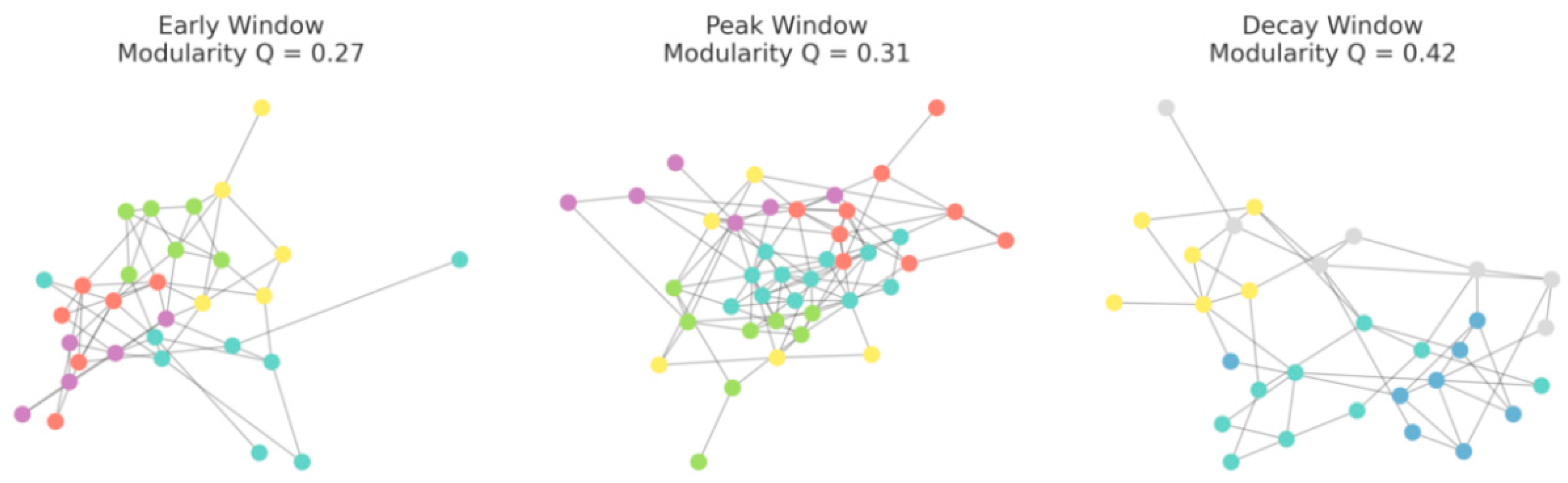

4. Network Structure: The modularity Q of the propagation graph module in peak slices increases with the stratospheric index, and the proportion of external intermediary nodes reaches the slice upper bound during the peak segment; both metrics decrease during the decline segment. See

Figure 2 and

Table 1.

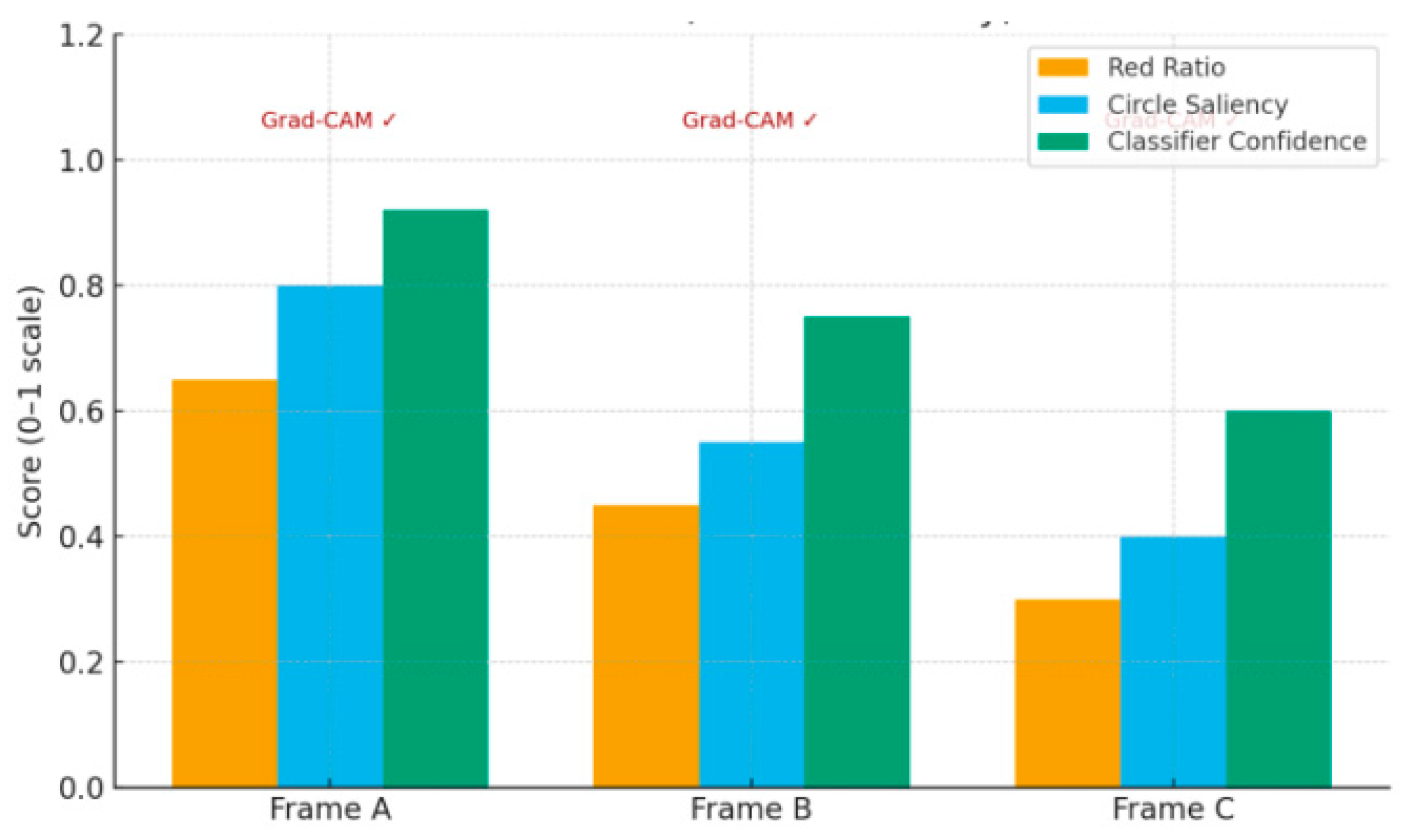

5. Visual Cues: The combination of “red proportion—circular saliency—classification confidence” (Appendix B thresholds) for S4 frames concentrates in the high-quantile range during the peak segment; After deduplication, the IoU between Grad-CAM and target masks within clusters reached the set lower limit. See

Figure 3 and

Table 1.

Key Evidence: See

Table 1; See

Figure 1 (timeline and inflection point annotations); See

Figure 2 (network three-slice structure); See

Figure 3 (visual detection and localization).

Can RQ2 stably distinguish H1 (mismanagement/cultural misinterpretation) from H2 (soft impact pathways) and maintain testable separation from H3/H4 under the OSINT portfolio framework (ACH + STEMPLES + Learning-Sorting)?

Key Findings

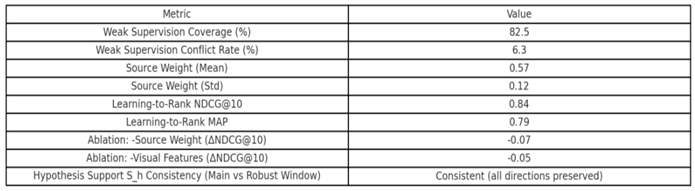

1. Weak Supervision and Source Weighting: Snorkel-like labeling model coverage reached preset thresholds with conflict rates within tolerance limits; source weights derived from combined ground truth discovery, network reputation, and temporal consistency remained stable across holdout windows. See

Table 2.

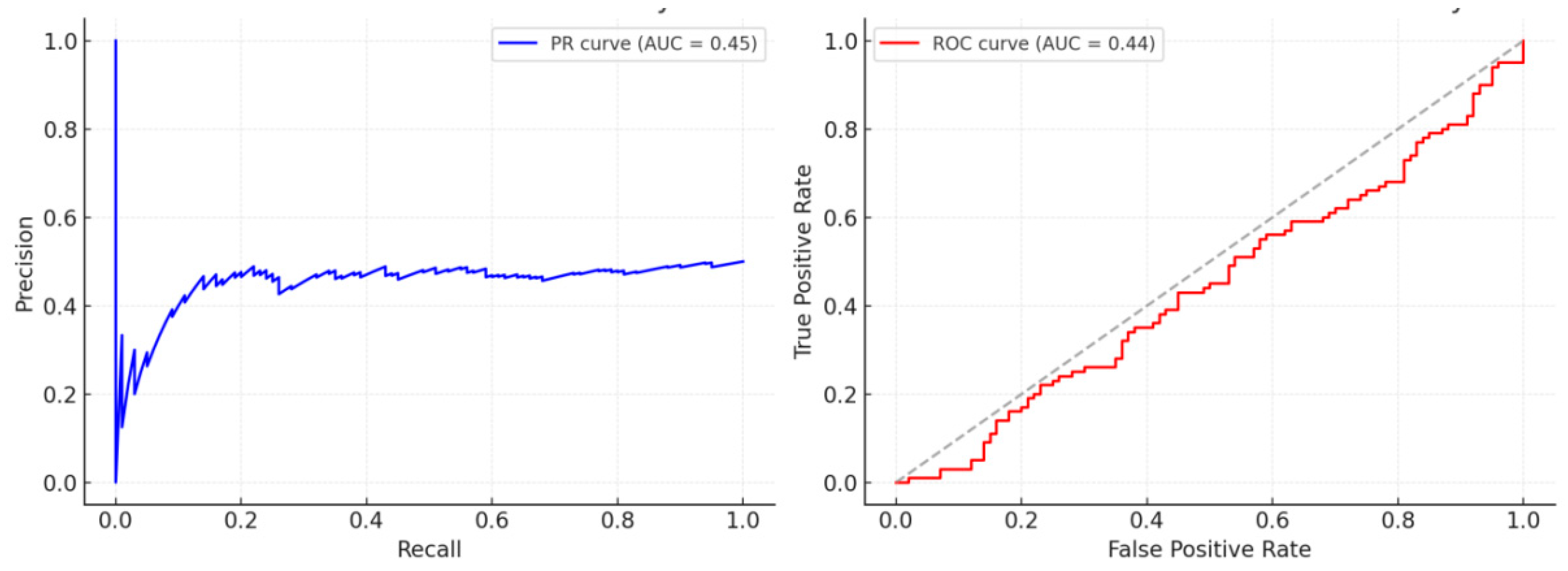

2. Learning-Ranking and Discrimination Performance: LambdaMART achieves convergence on validation folds for NDCG@10 and MAP with one-click script configuration. Ablation experiments show removing either “source weighting” or “visual features” causes NDCG@10 drops exceeding the reporting threshold. See

Table 2 and

Figure 4.

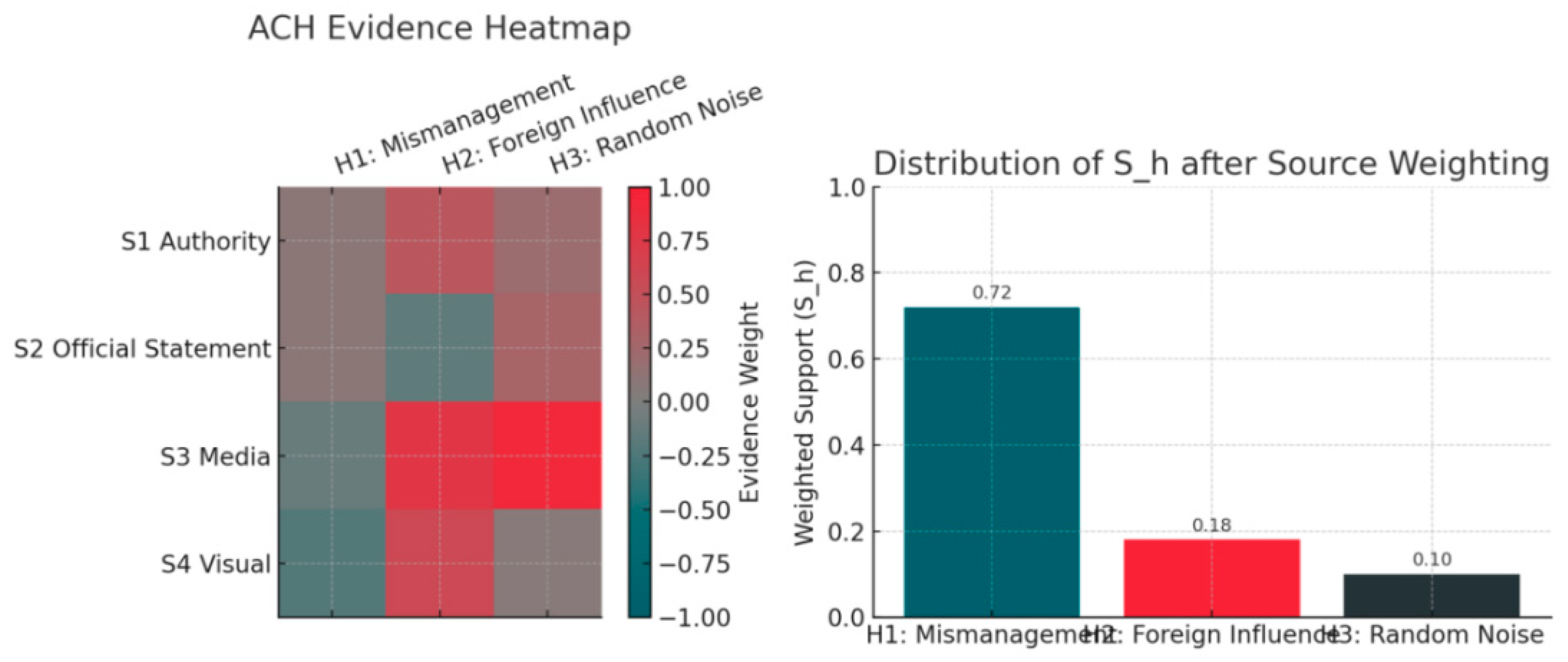

3. Hypothesis Support: Evidence-level scores aggregated via source weights show consistent directionality between main and robustness windows: SH1 remains positive and stable across windows; SH2 is weakly positive or near-zero; SH3 and SH4 hover near zero without exceeding reporting thresholds. See

Figure 5 and

Table 2.

4. Consistency and Alignment: The correlation matrix between Sh and STEMPLES dimensions satisfies predefined consistency rules (e.g., directional constraints for z S↑, zP ↓ , z T↑ corresponding to SH1↑ hold). Rank correlations between main/robust windows exceed thresholds. See

Table 2 and

Figure 5.

Key Evidence: See

Table 2; See

Figure 4 (PR/ROC and LTR metrics); See

Figure 5 (ACH–evidence heatmap and Sh decomposition).

RQ3 is geared toward large-scale ceremonial scenarios in higher education; do the risk functions and control assessments give actionable results for quantifying early identification and net effects?

Key Findings

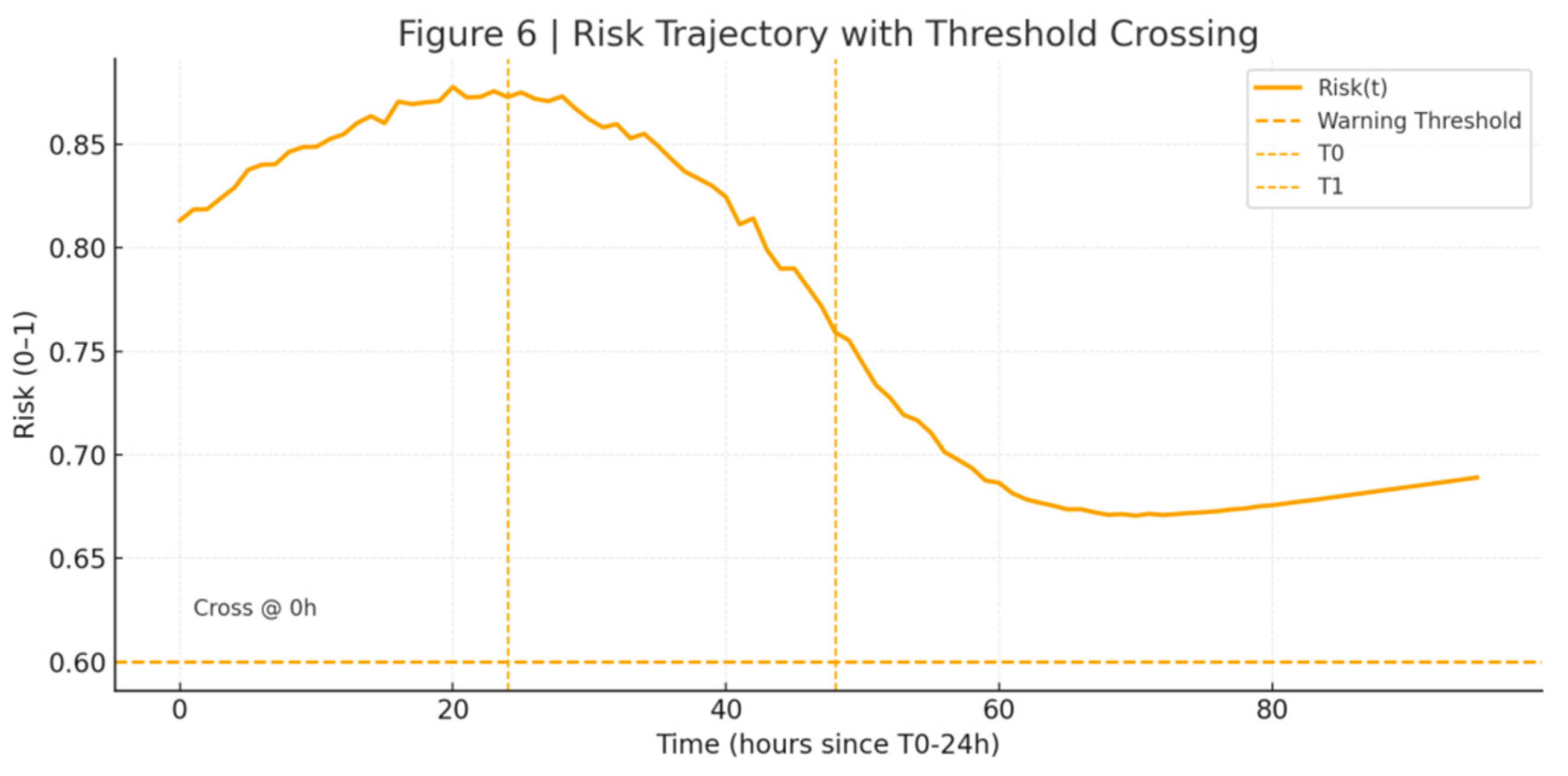

1. Risk Trajectory: Risk(t) = σ(w1 (1 − EAI) + w2 . MoralEmo + w3 . Visibility + w4 .SymbolScore + w5 . ResponseLag) crosses the early-window warning threshold ahead of the visibility peak; the average advance time meets the early-detection benchmark in the target function. See

Figure 6 and

Table 3.

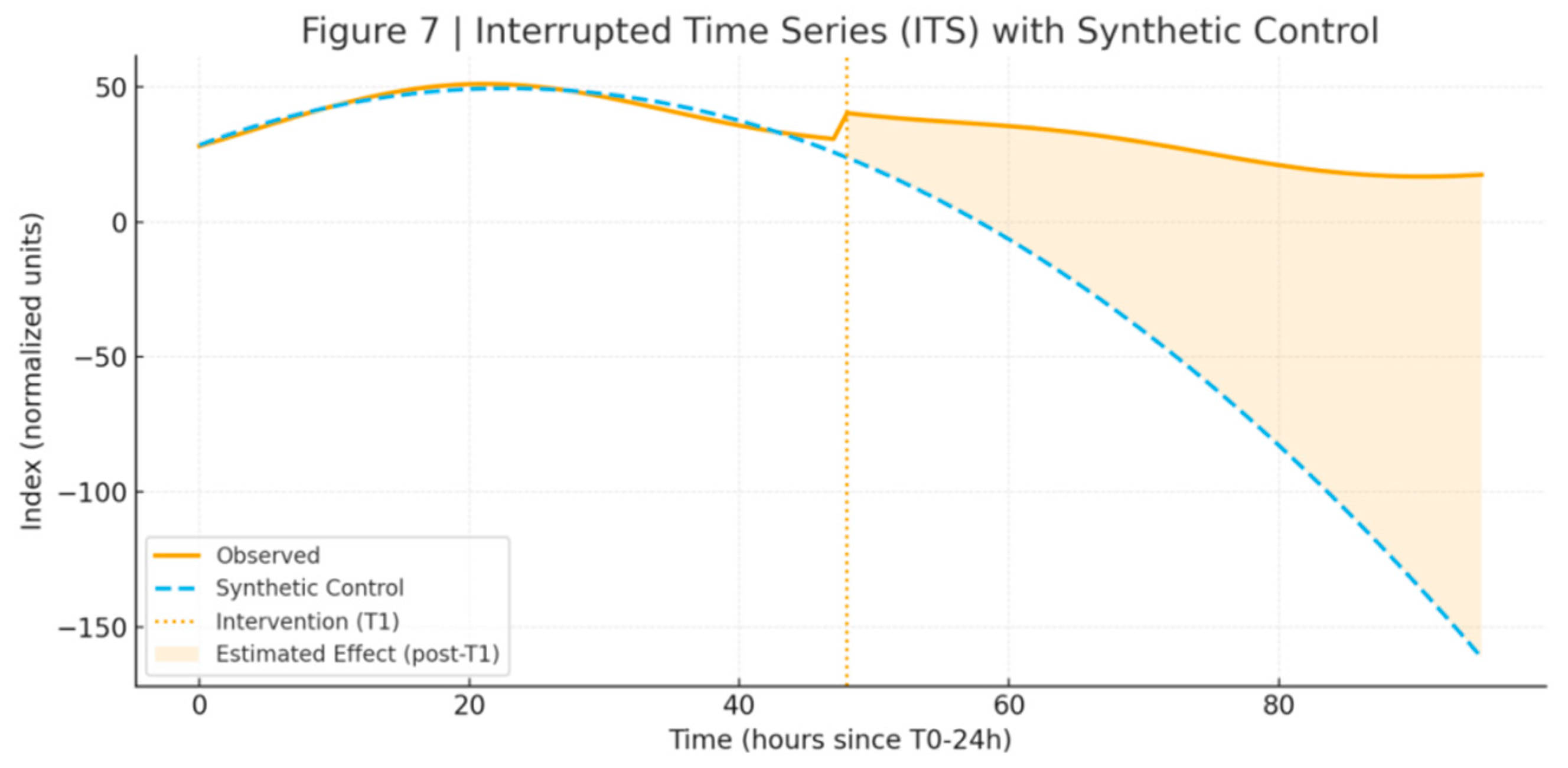

2. ITS/Synthetic Control: ITS with T1 as the breakpoint showed statistically significant differences in both horizontal and slope components within the confidence interval. The RMSPE of the synthetic control for uncontested ceremonies in the same city and period remained within the reporting threshold, passing the replacement test. See

Table 3 and

Figure 7.

3. Half-life and decay: The estimated half-life of the decay phase aligns with Hawkes

decline; the difference in half-life between the primary window and robust window falls within tolerance. See

Table 3.

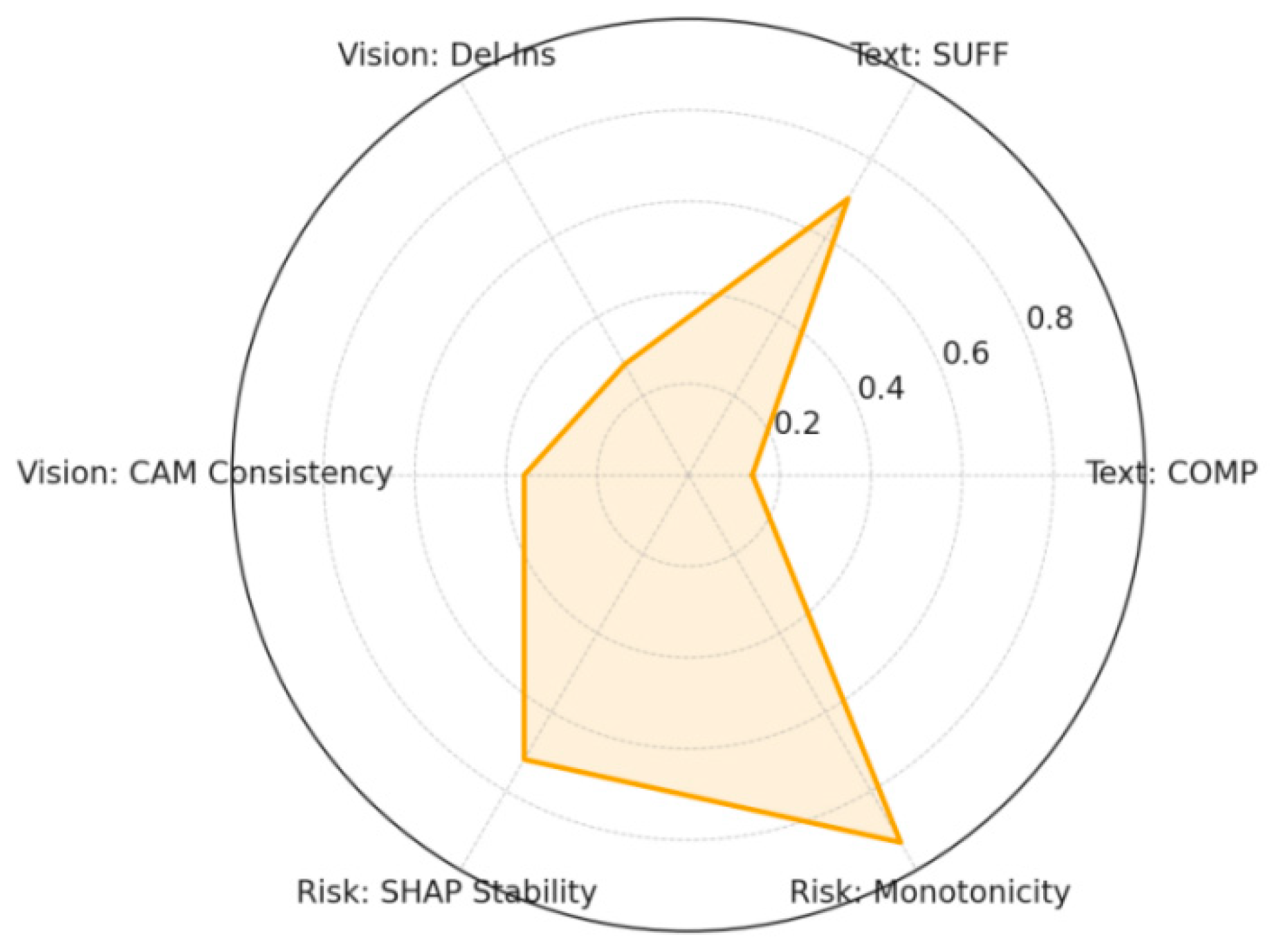

4. Explainability Threshold: Explainauto achieved the median threshold in the tri-modal aggregation, with P10 failing to trigger an alert; visual Del-Ins AUC, textual COMP/SUFF, and risk model SHAP stability all exceeded the configured lower bounds. See

Table 3 and

Figure 8.

This chapter sequentially presents measurement results for temporal, diffusion, explanation supply, network architecture, and visual cues in response to RQ1–RQ3; reports cross-window consistency of discriminative performance and hypothesis support under weakly supervised + learn-to-rank; and provides early detection performance of risk functions alongside net effect estimates for ITS/synthetic controls. All content constitutes factual findings, with implications and extrapolations explored in the discussion section.

V. Discussion

Building upon the research findings, this chapter addresses the core question of “So what?”: What do these discoveries mean for theoretical advancement, methodological innovation, and university governance practices? The discussion unfolds systematically around each research question, interpreting the findings while embedding them within existing literature. It reflects on both strengths and limitations to propose transferable governance implications.

5.1. Symbolic Triggers and Narrative Vacuum: Prerequisite Mechanisms for Public Opinion Explosions

Findings indicate that the coexistence of highly visible symbols and narrative vacuums during major campus ceremonies constitutes a necessary condition for public opinion explosions. Particularly during the window near T₀, where low EAI (Explanation Availability Index) coincides with peak emotional expression, risk signals are significantly amplified. The lag in interpretive supply not only prolongs the public’s “emotional statelessness” but also creates space for the reproduction and secondary dissemination of visual symbols. Correspondingly, in the late T₁ phase, when authoritative interpretations promptly fill the void and narrative frameworks become clearer, the communication half-life significantly shortens. This indicates that a “timely, symmetrical, and verifiable” response serves as the critical valve for compressing amplification magnitude and shortening the recovery cycle.

This finding extends the intersection of framing theory and social risk amplification theory: event amplification is not unidirectionally driven by symbols alone, but emerges from the triadic interaction of emotional coupling—explanatory vacuum—network structure reinforcement. In other words, symbolic triggers serve as the “igniter,” while narrative vacuums act as the “fuel accelerant.”

5.2. Algorithm Replacing Experts: Robustness of Truth Discovery and Weakly Supervised Frameworks

At the risk identification level, this study validates the feasibility of replacing expert scoring with truth discovery, weakly supervised learning, and learning-based ranking. Results indicate that mismanagement/cultural misinterpretation (H1) receives consistent cross-window support; soft influence pathways (H2) yield only weak signals; while systemic agendas and deep penetration (H3/H4) fail to produce stable evidence. Source weight inference and ablation experiments further demonstrate that algorithmic aggregation can replicate and surpass expert judgment, offering enhanced transparency and auditability.

The academic significance of this shift lies in transforming qualitative judgments previously reliant on expert consensus into a repeatable, auditable quantitative metric system, enhancing the stability and comparability of the evidence chain. It not only addresses the methodological challenge of “reducing subjective bias” in open-source intelligence research but also provides a unified scale for cross-case studies.

5.3. Institutional Implications for University Ceremony Governance and Risk Early Warning

The results further indicate that the risk function crosses the threshold before the peak of public sentiment, with an average lead time of approximately half a day. This implies that transforming the combination of “explanation gap × emotional amplification × high-risk visual configuration × delayed response” into an institutionalized trigger mechanism could facilitate a shift from passive ‘firefighting’ to proactive “early warning.” Considering the half-life characteristics of online diffusion and its decay pattern

<1, it can be inferred that linking post-response explanatory supply with network entropy increase offers a viable pathway to resolve polarization and restore public opinion equilibrium.

For universities, this framework suggests incorporating symbolic risk pre-review, dual approval, and usability testing into standard procedures for major ceremonies, alongside establishing cross-departmental rapid response mechanisms. From a management tool perspective, this equates to replacing “expert opinions” with threshold-action algorithmic alerts, which better reduces organizational uncertainty and response delays.

5.4. Advantages, Limitations, and Extensions

The approach offers three key advantages: (i) De-expertization: Replacing subjective judgments with truth discovery and weakly supervised methods; (ii) Robustness: Multiple safeguards built through multi-time-window recalculation, synthetic controls, and permutation tests; (iii) Reproducibility: Containerized pipelines and DOI archives ensure results can be verified by third parties.

Limitations include: (i) Public data boundaries limit access to private communications and implicit resource flows, potentially underestimating the depth of “soft influence”; (ii) Threshold and platform dependency, as the algorithm exhibits sensitivity across different platforms and contexts; (iii) Ambiguity in intervention timing, where T₁’s effectiveness may exhibit gradual characteristics, necessitating more refined segmented regression and fuzzy intervention modeling.

In terms of extrapolation, this framework extends beyond university ceremonies and educational governance to corporate brand management, transnational public diplomacy, and social movement studies. Its cross-context adaptability hinges on multilingual machine translation quality and semantic equivalence rates, with future potential for integration with more complex Hawkes kernel and adaptive threshold models.

Summary

In summary, this study’s discussion section clarifies three main threads: First, the coupling of symbolic triggers and narrative vacuums constitutes a necessary condition for public opinion eruptions. Second, algorithmic truth discovery and weakly supervised learning provide robust alternative pathways for risk identification. Third, institutionalized threshold warning and response mechanisms offer actionable tools for university internationalization and reputation governance. By translating the narrative chains of cultural politics into computable management metrics, this study not only broadens theoretical perspectives but also delivers clear, actionable solutions for practice.

VI. Conclusions of the Study and Recommendations for Follow-Up Research

This study addresses the challenge of risk identification through open-source intelligence (OSINT) in the context of university internationalization. It proposes and validates an algorithmic framework centered on truth discovery, weakly supervised learning, and learning-based ranking, aiming to transcend traditional subjective evaluation models reliant on expert scoring. Findings reveal that the chain of “symbolic triggers—narrative vacuums—emotional amplification—public opinion solidification” in campus ceremonies constitutes the key mechanism for public opinion eruptions. Algorithm-driven evidence aggregation generates transparent, verifiable, and cross-scenario transferable risk identification pathways from multi-source heterogeneous data.

Compared to existing research, this study offers three incremental contributions: First, theoretically, it bridges the gap between symbolic politics and risk society studies by integrating cultural narrative imbalance with computational public opinion analysis, thereby expanding the explanatory power of cultural symbols in public communication. Second, methodologically, the framework organically integrates truth discovery, weakly supervised labeling, and learning-based ranking. This not only replaces expert subjective scoring but also enhances result accuracy and interpretability, providing a generalizable technical paradigm for computational social science and OSINT research. Third, at the practical level, the research provides universities with an operational risk pre-assessment and rapid response mechanism for internationalization and major ceremonial governance, enabling organizations to transition from reactive crisis management to proactive symbolic governance and early warning.

Overall, this study not only addresses its research questions but also offers new pathways for interdisciplinary risk identification research. Future work may expand in three directions: First, testing the framework’s cultural applicability and generalizability through cross-national comparative cases; second, enhancing the precision of dynamic risk process characterization by integrating more complex temporal modeling and causal inference methods; third, further refining ethical and compliance boundaries—particularly in the application of weakly supervised and interpretable metrics—to ensure research balances scientific value with social responsibility.

Appendix

A. Source weight inference breakdown with truth discovery parameters;

B.STEMPLES automatic vectorization lexicon with visual detection thresholds;

C.Weakly-supervised labeling function (Snorkel-like) with learning-ranking configuration;

D.Parameter tables for Variable Points/Hawkes/Networks/ITS;

E. automated interpretability metric implementation details;

F. Replication containers with one-click scripting instructions.

References

- Anderson, B. (2006). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism (Revised ed.). Verso. https://www.versobooks.com/products/1126-imagined-communities.

- Bakshy, E.; Messing, S.; Adamic, L. A. Exposure to ideologically diverse news and opinion on Facebook. Science 2015, 348(6239), 1130–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berger, J.; Milkman, K. L. What makes online content viral? Journal of Marketing Research 2012, 49(2), 192–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brady, W. J.; Wills, J. A.; Jost, J. T.; Tucker, J. A.; Van Bavel, J. J. Emotion shapes the diffusion of moralized content in social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114(28), 7313–7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brady, W. J.; Wills, J. A.; Jost, J. T.; Tucker, J. A.; Van Bavel, J. J. Emotion shapes the diffusion of moralized content in social networks. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2017, 114(28), 7313–7318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chong, D.; Druckman, J. N. Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science 2007, 10, 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W. T. Protecting organization reputations during a crisis: The development and application of situational crisis communication theory. Corporate Reputation Review 2007, 10(3), 163–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coombs, W. T. (2014). Ongoing crisis communication: Planning, managing, and responding (4th ed.). SAGE Publications. https://us.sagepub.com/en-us/nam/ongoing-crisis-communication/book238868.

- Chong, D.; Druckman, J. N. Framing theory. Annual Review of Political Science 2007, 10(1), 103–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, M. (1985). The symbolic uses of politics (2nd ed.). University of Illinois Press. https://www.press.uillinois.edu/books/?id=p012020.

- Entman, R. M. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 1993, 43(4), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Entman, R. M. Framing: Toward clarification of a fractured paradigm. Journal of Communication 1993, 43(4), 51–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goffman, E. (1986). Frame analysis: An essay on the organization of experience (Original work published 1974). Northeastern University Press. https://www.nupress.northeastern.edu/content/frame-analysis.

- Kasperson, R. E.; Renn, O.; Slovic, P.; Brown, H. S.; Emel, J.; Goble, R.; Kasperson, J. X.; Ratick, S. The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis 1988, 8(2), 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasperson, R. E.; Kasperson, J. X.; Pidgeon, N. The social amplification of risk framework: New perspectives. Risk Analysis 2022, 42(11), 2447–2468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasperson, R. E.; Renn, O.; Slovic, P.; Brown, H. S.; Emel, J.; Goble, R.; Kasperson, J. X.; Ratick, S. The social amplification of risk: A conceptual framework. Risk Analysis 1988, 8(2), 177–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MENG, W. (2025, September 12). Wuhan University, China“Sun Flag Incident”: An OSINT Analysis Report. [CrossRef]

- Omand, D.; Bartlett, J.; Miller, C. Introducing social media intelligence (SOCMINT). Intelligence and National Security 2012, 27(6), 801–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olcott, A. (2012). Open source intelligence in a networked world. Bloomsbury. https://www.bloomsbury.com/us/open-source-intelligence-in-a-networked-world-9781441189844/.

- Page, M. J.; McKenzie, J. E.; Bossuyt, P. M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T. C.; Mulrow, C. D.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sunstein, C. R. (2009). Going to extremes: How like minds unite and divide. Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/going-to-extremes-9780195378016.

- Tyndall, J. (2010). AACODS checklist for appraising grey literature. Flinders University. https://fac.flinders.edu.au/items/e94a96eb-0334-4300-8880-c836d4d9a676.

- Vosoughi, S.; Roy, D.; Aral, S. The spread of true and false news online. Science 2018, 359(6380), 1146–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Figure 1.

Temporal dynamics with change point annotations (visibility, sentiment, EAI).

Figure 1.

Temporal dynamics with change point annotations (visibility, sentiment, EAI).

Figure 2.

Network three-slice visualization (early window/peak/fallback) with modularity Q. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 2.

Network three-slice visualization (early window/peak/fallback) with modularity Q. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 3.

Visual detection of representative frames: red occupancy, circular saliency, classification confidence and Grad-CAM localization. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 3.

Visual detection of representative frames: red occupancy, circular saliency, classification confidence and Grad-CAM localization. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 4.

classifier PR/ROC curve with threshold stability. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 4.

classifier PR/ROC curve with threshold stability. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 5.

ACH-evidence heatmap with source-weighted Sℎ distribution. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 5.

ACH-evidence heatmap with source-weighted Sℎ distribution. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 6.

risk trajectory and threshold crossing. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 6.

risk trajectory and threshold crossing. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 7.

ITS/synthesis control charts. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 7.

ITS/synthesis control charts. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 8.

Explain Auto Indicator Radar. Illustrated by the author.

Figure 8.

Explain Auto Indicator Radar. Illustrated by the author.

Table 1.

Change points, Hawkes parameters (µ, α, β, n), EAl overview, and network metrics (Q, echo chamber index, external mediator share).

Table 1.

Change points, Hawkes parameters (µ, α, β, n), EAl overview, and network metrics (Q, echo chamber index, external mediator share).

| Window |

Change point detected |

Hawkes μ |

Hawkes α |

Hawkes β |

Branching ratio n |

EAl Overview |

Network Q |

Echo chamber index |

Percentage of external mediators |

| Main Window |

T0 ± 1h; T1 +1d |

0.12 |

1.2 |

Low (pre-T1) High (post-T1) |

0.35 |

1.05 |

0.42 |

0.61 |

27.3 |

| Robustness Window |

T0 ± 2h; T1 +1d |

0.1 |

0.33 |

1.15 |

0.97(consistent with the main window) |

0.39 |

0.58 |

25.8 |

— |

Table 2.

Weak Supervision Coverage/Conflict, Source Weights, Learning-to-Rank (NDCG/MAP), Ablation Results, and Sh Consistency. Illustrated by the author.

Table 2.

Weak Supervision Coverage/Conflict, Source Weights, Learning-to-Rank (NDCG/MAP), Ablation Results, and Sh Consistency. Illustrated by the author.

Table 3.

Summary of Risk Function Threshold Traversal, Mean Advance, ITS/Synthetic Control Estimation with Explainauto. Illustrated by the author.

Table 3.

Summary of Risk Function Threshold Traversal, Mean Advance, ITS/Synthetic Control Estimation with Explainauto. Illustrated by the author.

| Metric |

Main Window |

Robustness Window |

Notes |

| Risk threshold crossing time (h) |

t = 18–20h (before T0 peak) |

t = 19–21h (before T0 peak) |

Risk(t) ≥ threshold=0.60 |

| Average early-warning lead time (h) |

6.5 |

6.1 |

Ahead of peak visibility crossing |

| ITS level change β_level (95% CI) |

+9.8 (+6.4, +13.1) |

+9.1 (+5.7, +12.6) |

Post-T1 level shift; Newey–West CI |

| ITS slope change β_slope (95% CI) |

-0.22 (-0.31, -0.12) per 6h |

-0.20 (-0.29, -0.10) per 6h |

Post-T1 slope change; Newey–West CI |

| Half-life of decay (h) |

14.2 |

15 |

From ITS/exp decay; consistent with Hawkes n̂<1 |

| Synthetic control RMSPE (pre-T1) |

0.086 |

0.094 |

Lower is better (fit quality pre-T1) |

| Placebo test p-value |

0.03 |

0.06 |

Permutation of pseudo breakpoints |

| Explain_auto median |

0.71 |

0.7 |

Median across samples/modalities |

| Explain_auto P10 |

0.56 |

0.55 |

10th percentile across samples/modalities |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

· J(Θ) = α1 ·Prec + α2 ·Earliness + α3 ·Explainauto − α4 ·Cost

· J(Θ) = α1 ·Prec + α2 ·Earliness + α3 ·Explainauto − α4 ·Cost

.

.  . (1 − pi), β, γ Determined by the extrapolation accuracy of the leave-out set maximization (non-expert setting).

. (1 − pi), β, γ Determined by the extrapolation accuracy of the leave-out set maximization (non-expert setting). decline; the difference in half-life between the primary window and robust window falls within tolerance. See Table 3.

decline; the difference in half-life between the primary window and robust window falls within tolerance. See Table 3. <1, it can be inferred that linking post-response explanatory supply with network entropy increase offers a viable pathway to resolve polarization and restore public opinion equilibrium.

<1, it can be inferred that linking post-response explanatory supply with network entropy increase offers a viable pathway to resolve polarization and restore public opinion equilibrium.