Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

02 May 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

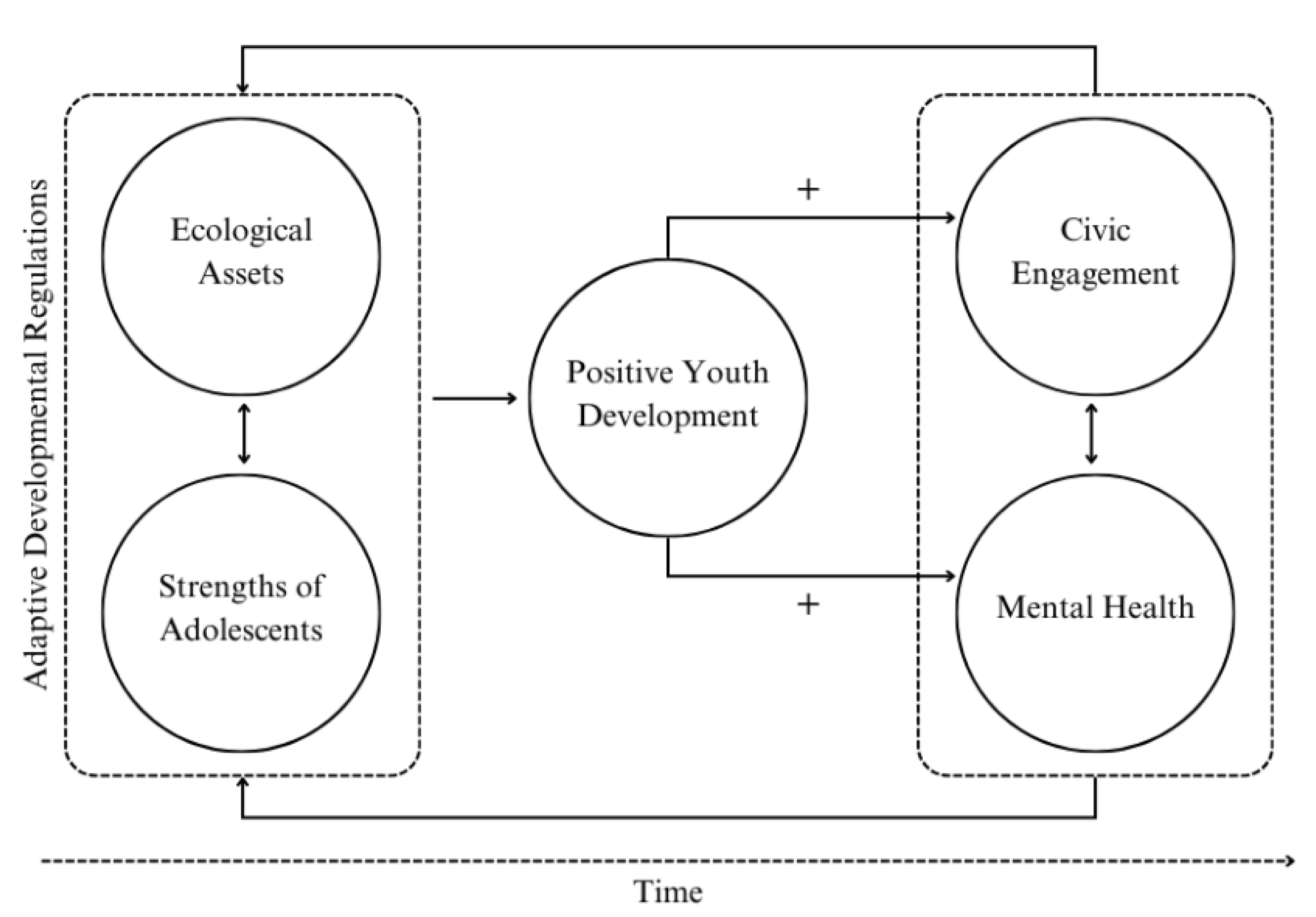

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Description of Articles

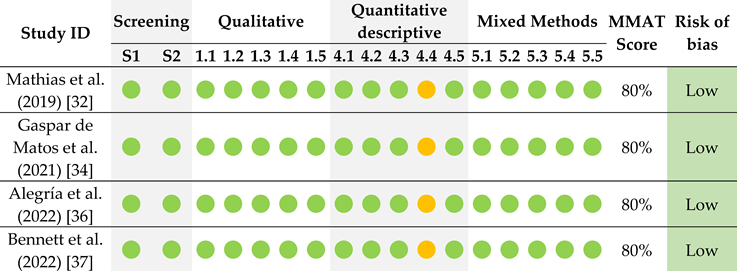

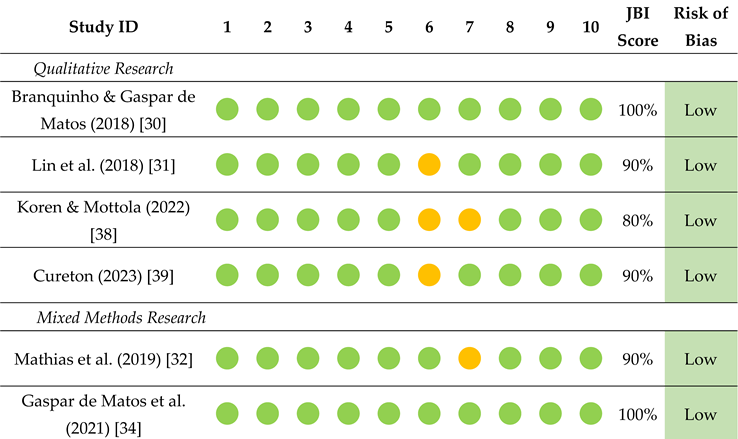

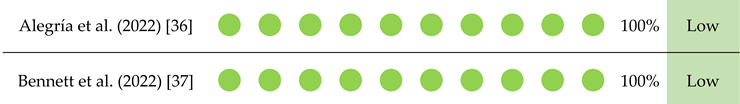

3.2. Critical Appraisal and Risk of Bias

3.3. Academic Relevance

3.4. Description of results

4. Discussion

4.1. General Interpretation of Results

4.2. Contributions and Practical Implications of the Research

4.3. Limitations of the Studies Included in the Review

4.4. Limitations of the Scoping Review and Future Research

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UN | United Nations |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| APA | American Psychological Association |

| PYD | Positive Youth Development |

| RDS | Relational Developmental Systems Theory |

| DST | Developmental Systems Theory |

| JBI | Joanna Briggs Institute |

| MMAT | Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool |

| MINORS | Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies |

| RCT | Randomized Controlled Trials |

| JIF | Journal Impact Factor |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

| SECTION | ITEM | PRISMA-ScR CHECKLIST ITEM | REPORTED ON PAGE # |

|---|---|---|---|

| TITLE | |||

| Title | 1 | Identify the report as a scoping review. | 1 |

| ABSTRACT | |||

| Structured summary | 2 | Provide a structured summary that includes (as applicable): background, objectives, eligibility criteria, sources of evidence, charting methods, results, and conclusions that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 1 |

| INTRODUCTION | |||

| Rationale | 3 | Describe the rationale for the review in the context of what is already known. Explain why the review questions/objectives lend themselves to a scoping review approach. | 1 |

| Objectives | 4 | Provide an explicit statement of the questions and objectives being addressed with reference to their key elements (e.g., population or participants, concepts, and context) or other relevant key elements used to conceptualize the review questions and/or objectives. | 4 |

| METHODS | |||

| Protocol and registration | 5 | Indicate whether a review protocol exists; state if and where it can be accessed (e.g., a Web address); and if available, provide registration information, including the registration number. | 4 |

| Eligibility criteria | 6 | Specify characteristics of the sources of evidence used as eligibility criteria (e.g., years considered, language, and publication status), and provide a rationale. | 4 |

| Information sources* | 7 | Describe all information sources in the search (e.g., databases with dates of coverage and contact with authors to identify additional sources), as well as the date the most recent search was executed. | 4 |

| Search | 8 | Present the full electronic search strategy for at least 1 database, including any limits used, such that it could be repeated. | 4 |

| Selection of sources of evidence† | 9 | State the process for selecting sources of evidence (i.e., screening and eligibility) included in the scoping review. | 5 |

| Data charting process‡ | 10 | Describe the methods of charting data from the included sources of evidence (e.g., calibrated forms or forms that have been tested by the team before their use, and whether data charting was done independently or in duplicate) and any processes for obtaining and confirming data from investigators. | NA |

| Data items | 11 | List and define all variables for which data were sought and any assumptions and simplifications made. | NA |

| Critical appraisal of individual sources of evidence§ | 12 | If done, provide a rationale for conducting a critical appraisal of included sources of evidence; describe the methods used and how this information was used in any data synthesis (if appropriate). | 5 |

| Synthesis of results | 13 | Describe the methods of handling and summarizing the data that were charted. | 5 |

| RESULTS | |||

| Selection of sources of evidence | 14 | Give numbers of sources of evidence screened, assessed for eligibility, and included in the review, with reasons for exclusions at each stage, ideally using a flow diagram. | 5 |

| Characteristics of sources of evidence | 15 | For each source of evidence, present characteristics for which data were charted and provide the citations. | 7 |

| Critical appraisal within sources of evidence | 16 | If done, present data on critical appraisal of included sources of evidence (see item 12). | 9 |

| Results of individual sources of evidence | 17 | For each included source of evidence, present the relevant data that were charted that relate to the review questions and objectives. | 7 |

| Synthesis of results | 18 | Summarize and/or present the charting results as they relate to the review questions and objectives. | 12 |

| DISCUSSION | |||

| Summary of evidence | 19 | Summarize the main results (including an overview of concepts, themes, and types of evidence available), link to the review questions and objectives, and consider the relevance to key groups. | 14 |

| Limitations | 20 | Discuss the limitations of the scoping review process. | 17 |

| Conclusions | 21 | Provide a general interpretation of the results with respect to the review questions and objectives, as well as potential implications and/or next steps. | 18 |

| FUNDING | |||

| Funding | 22 | Describe sources of funding for the included sources of evidence, as well as sources of funding for the scoping review. Describe the role of the funders of the scoping review. | 18 |

References

- Best, O.; Ban, S. Adolescence: Physical changes and neurological development. Br. J. Nurs. 2021, 30(5), 272–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawyer, S. M.; Azzopardi, P. S.; Wickremarathne, D.; Patton, G. C. The age of adolescence. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2018, 2(3), 223–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arnett, J. J. Emerging adulthood(s): The cultural psychology of a new life stage. In Bridging Cultural and Developmental Approaches to Psychology: New Syntheses in Theory, Research, and Policy; Jensen, L. A., Ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, 2011; pp. 255–275. [Google Scholar]

- Orben, A.; Tomova, L.; Blakemore, S.-J. The effects of social deprivation on adolescent development and mental health. Lancet Child Adolesc. Health 2020, 4(8), 634–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blakemore, S.-J. Adolescence and mental health. Lancet 2019, 393(10185), 2030–2031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Solmi, M.; Radua, J.; Olivola, M.; Croce, E.; Soardo, L.; Salazar de Pablo, G.; Il Shin, J.; Kirkbride, J. B.; Jones, P.; Kim, J. H.; Kim, J. Y.; Carvalho, A. F.; Seeman, M. V.; Correll, C. U.; Fusar-Poli, P. Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: Large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies. Mol. Psychiatry 2022, 27(1), 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray-Lake, L.; Abrams, L. S. Pathways to civic engagement among urban youth of color. Monogr. Soc. Res. Child Dev. 2020, 85(2), 7–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, R.; Goggin, J. What do we mean by “civic engagement”? J. Transform. Educ. 2005, 3, 236–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- American Psychological Association (APA). Civic Engagement. https://www.apa.org/education-career/undergrad/civic-engagement (accessed on 12 Dec 2024).

- Sharaf Eldin, N.; Ibrahim, N. F.; Farrag, N. S.; Elsheikh, E. The effect of civic engagement on mental health and behaviors among adolescents. Med. Updates 2025, 21(6), 76–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mužík, M.; Šerek, J.; Juhová, D. S. The effect of civic engagement on different dimensions of well-being in youth: A scoping review. Adolesc. Res. Rev. [CrossRef]

- Wiium, N.; Kristensen, S. M.; Årdal, E.; Bøe, T.; Gaspar de Matos, M.; Karhina, K.; Larsen, T. M. B.; Urke, H. B.; Wold, B. Civic engagement and mental health trajectories in Norwegian youth. Front. Public Health 2023, 11, 1214141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wray-Lake, L.; Shubert, J.; Lin, L.; Starr, L. R. Examining associations between civic engagement and depressive symptoms from adolescence to young adulthood in a national U.S. sample. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2017, 23(2), 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fong, C.-P.; To, S.-M. Civic engagement, social support, and sense of meaningfulness in life of adolescents living in Hong Kong: Implications for social work practice. Child Adolesc. Soc. Work J. 2022, 41, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspar de Matos, M.; Simões, C. From positive youth development to youth’s engagement: The Dream Teens. Int. J. Emot. Educ. 2016, 8(11), 4–18. [Google Scholar]

- Shek, D. T.; Sun, R. C.; Merrick, J. Positive youth development constructs: Conceptual review and application. Sci. World J. 2012, 2012, 152923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snyder, F. J.; Flay, B. R. Positive youth development. In Handbook of Prosocial Education; Brown, P. M., Corrigan, M. W., Higgins-D’Alessandro, A., Eds.; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, 2012; Volume 2, pp. 415–443. [Google Scholar]

- Damon, W. What is positive youth development? Ann. Am. Acad. Polit. Soc. Sci. 2004, 591(1), 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolan, P.; Ross, K.; Arkin, N.; Godine, N.; Clark, E. Toward an integrated approach to positive development. Appl. Dev. Sci. 2016, 20, 214–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R. M. Liberty: Thriving and Civic Engagement Among America’s Youth; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettekal, A. V.; Burkhard, B.; Fremont, E.; Su, S.; Stacey, D. C. Relational developmental systems metatheory. In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Out-of-School Learning; SAGE Publications, Inc.: Thousand Oaks, CA, 2017; Volume 2, pp. 650–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, R. M.; Wang, J.; Champine, R.; Warren, D.; Erickson, K. Development of civic engagement: Theoretical and methodological issues. Int. J. Dev. Sci. 2014, 8, 69–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cahill, S. M.; Egan, B. E.; Seber, J. Activity- and occupation-based interventions to support mental health, positive behavior, and social participation for children and youth: A systematic review. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 2020, 74(2), 1–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urrútia, G.; Bonfill, X. Declaración PRISMA: Una propuesta para mejorar la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas y metaanálisis. Med. Clínica 2010, 135 (11), 507–511. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K. K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; Hempel, S.; Akl, E. A.; Chang, C.; McGowan, J.; Stewart, L.; Hartling, L.; Aldcroft, A.; Wilson, M. G.; Garritty, C.; Lewin, S.; Straus, S. E. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169(7), 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lockwood, C.; Munn, Z.; Porritt, K. Qualitative research synthesis: Methodological guidance for systematic reviewers utilizing meta-aggregation. Int. J. Evid.-Based Healthc. 2015, 13 (3), 179–187. [CrossRef]

- Hong, Q. N.; Fàbregues, S.; Bartlett, G.; Boardman, F.; Cargo, M.; Dagenais, P.; Gagnon, M. P.; Griffiths, F.; Nicolau, B.; O’Cathain, A.; Rousseau, M. C.; Vedel, I.; Pluye, P. The Mixed Methods Appraisal Tool (MMAT) version 2018 for information professionals and researchers. Educ. Inf. 2018, 34(4), 285–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Slim, K.; Nini, E.; Forestier, D.; Kwiatkowski, F.; Panis, Y.; Chipponi, J. Methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J. Surg. 2003, 73(9), 712–716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, J. P. T.; Altman, D. G.; Sterne, J. A. C. Chapter 8: Assessing risk of bias in included studies. In Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; Higgins, J. P. T.; Churchill, R.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M. S., Eds.; Cochrane: 2017. Available online: https://www.training.cochrane.org/handbook.

- Branquinho, C.; Gaspar de Matos, M. G. The “Dream Teens” project: After a two-year participatory action-research program. Child Indic. Res. 2018, 12, 1243–1257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, J. L. L.; Chan, M.; Kwong, K.; Au, L. Promoting positive youth development for Asian American youth in a Teen Resource Center: Key components, outcomes, and lessons learned. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2018, 91, 413–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathias, K.; Singh, P.; Butcher, N.; Grills, N.; Srinivasan, V.; Kermode, M. Promoting social inclusion for young people affected by psycho-social disability in India—a realist evaluation of a pilot intervention. Glob. Public Health 2019, 14(12), 1718–1732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaspar de Matos, M.; Kleszczewska, D.; Gaspar, T.; Dzielska, A.; Branquinho, C.; Michalska, A.; Mazur, J. Making the best out of youth—the Improve the Youth project. J. Community Psychol. 2021, 49(6), 2071–2085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Prati, G.; Mazzoni, D.; Guarino, A.; Albanesi, C.; Cicognani, E. Evaluation of an active citizenship intervention based on youth-led participatory action research. Health Educ. Behav. 2020, 47(6), 894–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gehue, L. J.; Crouse, J. J.; Battisti, R. A.; Yim, M.; Carpenter, J. S.; Scott, E. M.; Hickie, I. B. Piloting the ‘Youth Early-intervention Study’ (‘YES’): Preliminary functional outcomes of a randomized controlled trial targeting social participation and physical well-being in young people with emerging mental disorders. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 280 (Part A), 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegría, M.; Alvarez, K.; NeMoyer, A.; Zhen, D. J.; Marsico, C.; O’Malley, I. S.; Mukthineni, R.; Porteny, T.; Herrera, C.; Najarro Cermeño, J.; Kingston, K.; Sisay, E.; Trickett, E. Development of a youth civic engagement program: Process and pilot testing with a youth-partnered research team. Am. J. Community Psychol. 2022, 69 (1–2), 86–99. [CrossRef]

- Bennett, K. M.; Campbell, J. M.; Hays, S. P. Engaging youth for positive change: A mixed methods evaluation of site level program implementation & outcomes. Child Youth Serv. Rev. 2022, 141, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koren, A.; Mottola, E. Marginalized youth participation in a civic engagement and leadership program: Photovoice and focus group empowerment activity. J. Community Psychol. 2022. [CrossRef]

- Cureton, A. Making a change! Exploring refugee youth’s civic engagement in out-of-school programs to cultivate critical consciousness. Children Schools 2023, 46(1), 27–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pimsen, A.; Kao, C.-Y.; Hsu, S.-T.; Shu, B.-C. The effect of advance care planning intervention on hospitalization among nursing home residents: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc. 2022, 23(9), 1448–1460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos-Sousa, H.; Amorim-Cruz, F.; Nogueiro, J.; Silva, A.; Amorim-Cruz, I.; Ferreira-Santos, R.; Bouça-Machado, R.; Pereira, A.; Resende, F.; Costa-Pinho, A.; Preto, J.; Lima-da-Costa, E.; Barbosa, E.; Carneiro, S.; Sousa-Pinto, B. Preoperative risk factors for early postoperative bleeding after Roux-en-Y gastric bypass surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Langenbecks Arch. Surg. 2024, 409(1), 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Inclusion criteria | Exclusion criteria | |

|---|---|---|

| Population | Adolescents and Young Adults (age 10 to 25). | Minors younger than 10 and adults older than 25. |

| Type of publication | Original articles involved in a peer-review process. Available and/or open-access articles. Use of an intervention. |

Others such as: Editorials or expert opinions. Systematic or narrative reviews. Dissertation, theses, presentations and conference proceedings. Non–peer reviewed publications. Unavailable or paid articles. |

| Study’s design | Quantitative, qualitative or mixed. | Others such as: case’s studies. |

| Language | English. | Other. |

| Publication date | 2018 to 2023. | Earlier than 2018. Later than 2024. |

| Results | Relationship between the programs carried out to promote civic engagement and its outcomes on the participants’ mental health. | Other. |

| Study ID | Sample | Method | Main Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| Branquinho & Gaspar de Matos (2018) [30] |

N = 46. Youth participants aged 11 to 18 (M = 16.13; SD = 1.89). Portugal. |

Longitudinal qualitative research. | (1) Five dimensions were obtained: Feelings and competencies for action, Interpersonal skills, Competencies for problem resolution, Humanitarianism, and Feelings towards life. (2) Teens considered that their participation was a valuable significant asset. (3) Pre-post data evaluation showed no significant differences across the five dimensions from year 1 to year 2. (4) Most participants engaged in different community leadership activities and volunteering. (5) Future plans: the majority intended to continue education beyond high school, with an increased interest in jobs in year 2. |

| Lin et al. (2018) [31] |

N = 18. Asian American participants aged 18 to 33 at the time of interview but aged 13 to 24 (M = 16) at initial involvement. United States. |

Qualitative research analyzing in-depth interviews. | Key Components of Positive Youth Development Programs: (1) Opportunities for Skill Building and Participation. (2) Positive Social Norms: healthy behaviors. (3) Safe Space: for self-expression and identity-exploration. (4) Sense of Belonging. (5) Supportive Organizational Culture and Staff. Influence on Youth Development: (1) Identity Development. (2) Healthy Life Choices. (3) Improved Relationships. (4) Competence and Self-Efficacy. (5) Career Choice. (6) Community Involvement and Volunteerism. |

| Mathias et al. (2019) [32] |

N = 142. Youth under 25 years old (M = 18.9) affected by psycho-social disability. India. |

Longitudinal mixed-method research. | (1) Formation of new friendship networks. (2) Increased self-efficacy and confidence. (3) Improved mental health: reduced anxiety, sadness, and frustration. (4) Increased community participation. (5) Women increased freedom of movement and confidence in communication. (6) Men improved community perceptions. (7) Contextual and intervention factors influencing outcomes: Parental support, peer facilitator skills, limited freedom for young women, and socio-economic factors. |

| Prati et al. (2020) [33] |

N = 69. Italian high school students 15 to 17 years old (M = 15.74; SD = 0.50) at pretest. Italy. |

Longitudinal quantitative research. | (1) No significant differences between the control and intervention groups in social well-being (p > .05), European identification (p > .05), attitudes toward the EU (p > .05), political alienation (p > .05), institutional trust (p > .05), and EU-level participation (p > .05). (2) Significant Group × Time interactions were observed for political alienation, institutional trust, EU-level participation, and social well-being. These effects had medium to large effect sizes. (3) A median split based on European identification showed no significant differences in posttest measures of the same outcomes between those with higher or lower identification as European. |

| Gaspar de Matos et al. (2021) [34] | Quantitative Study: N = 10571. Adolescents aged 11 to 15. Qualitative Study: N = 72. Adolescents aged 14 to 16 from Portugal and Poland. |

Longitudinal mixed-method research. | (1) Health-related issues increase with age and are more prevalent among boys. (2) Life satisfaction scores were similar, but distribution varied. Family economic status significantly influenced life satisfaction. (3) Polish adolescents reported more psychosomatic complaints than Portuguese. Qualitative results on the view of mental health: (1) Positive feedback about the clarity of the questions. (2) Linked mental health to both positive and negative feelings. (3) Identification of factors for maintaining mental health. (4) Identification of threats. (5) Desire for more attention to specific mental health issues in research and educational programs. |

| Gehue et al. (2021) [35] |

N = 133. Youth aged 14 to 25 with emerging mental health disorders. Australia. |

Longitudinal quantitative research. | (1) SOFAS (Social and Occupational Functioning scale): Scores improved (B = 4.96, p < 0.0001), but there were no significant differences by randomization group or diagnosis. (2) FAST (Functional Assessment Short Test): A decrease in scores indicated improved functioning (B = -3.44, p = 0.0001), but no significant associations with randomization group or sessions attended were found. (3) BDQ-7 ("Days unable"): Scores decreased over time (B = -2.01, p < 0.0001), but no significant associations were found. (4) BDQ-8 ("Days in bed"): Scores also decreased (B = -1.06, p = 0.023), but there were no significant associations with attendance, randomization group, or diagnosis. (5) Educational engagement improved significantly by the trial’s end. However, no significant differences were found in vocational outcomes between the trial’s end and follow-up. |

| Alegría et al. (2022) [36] |

N = 19. Youth participants aged 14 to 19 years (M = 16.11; SD = 1.10). United States. |

Longitudinal mixed method research. | (1) Desire for Change. (2) Sense of Pride. (3) Power and Responsibility to Enact Community Changes. Regarding the survey, two outcomes had a significant increase from baseline to wrap-up. These two are civic participation (p = .033) and leadership competence (p = .021). However, the effects were not sustained at follow-up. There was also a marginal increase in Belief in Self at wrap-up (p = .081), however it was not statistically significant. |

| Bennett et al. (2022) [37] |

N = 455. Youth participants, middle and high school students (M = 16.01; SD = 1.43). Illinois, United States. |

Longitudinal mixed method research. | Quantitatively, there was an overall program success, with an overall attrition rate of approximately 20%. Significant differences were noted in outcomes based on activity levels. Significant correlations were found between outcome scores and the number of activities (r = -0.54, p <.01) and implementation indices (r = -0.47, p <.01). The number of activities implemented was a significant predictor, explaining 31% of the variation. Facilitators reported on successes and challenges in five areas: (1) Most Effective Aspects: Discussions on local policies and data collection. (2) Least Effective: Concerns about meeting times and attendance. (3) Participants’ Likes: Policy discussions and community engagement. (4) Participants’ Dislikes: No major dislikes were reported. (5) Suggestions for Improvement: Longer meeting times and more flexible scheduling. |

| Koren & Mottola (2022) [38] |

N = 11. High school marginalized teens from grade 10 to 12. Massachusetts, United States. |

Qualitative research using focus group photograph and narrative analysis. | (1) Teens gained empowerment and a deeper connection to their community. (2) They explored and reflected on their identities. (3) The diverse group discussions broadened participants’ perspectives. (4) The photovoice activity empowered teens. (5) Teens shared challenges like discrimination, immigrant struggles, and socioeconomic barriers. (6) Participants expressed a desire to drive change in their communities. (7) Teens shared aspirations for academic and career success. |

| Cureton (2023) [39] |

N = 15. Refugee students in U.S. high schools aged 14 to 17. Chicago, United States. |

Qualitative research. | (1) Motivations for Civic Engagement: Sense of duty to learn about and advocate for their rights, driven by a desire to combat xenophobia and stereotypes. (2) Sense of Duty. (3) Community Connection. (4) Civic Training Programs. (5) Personal Empowerment: Civic involvement as a coping mechanism in response to anxiety. (6) Building a Supportive Community. |

|

= Yes

= Yes = Unclear

= Unclear  = No NA = Not Applicable.

= No NA = Not Applicable.| Study ID | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 | 11 | 12 | Quality Score | Risk of Bias |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Prati et al. (2020) [33] | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 21/24 | Moderate |

| Study ID | Sequence generation (Selection bias) | Allocation concealment (Selection bias) | Blinding of participants & personnel (Performance bias) |

Blinding of outcome assessment (Detection bias) | Incomplete outcome data (Attrition bias) | Selective outcome reporting (Reporting bias) |

Other potential threats to Validity (Other bias) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Gehue et al. (2021) [35] |  |

|

|

|

|

|

|

||

= High Risk.

= High Risk.  = Uncertain Risk.

= Uncertain Risk.  = Low risk.

= Low risk.| Study ID | Journal | Category | Journal Impact Factor (JIF) | Quartile (JIF) | Percentile (JIF) | Citations Received (article) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Branquinho & Gaspar de Matos (2018) [30] | Child Indicators Research | Social Sciences, Interdisciplinary | 1.656 | Q2 | 62.98 | 26 |

| Lin et al. (2018) [31] | Children and Youth Services Review | Social Work | 1.684 | Q1 |

84.88 | 12 |

| Mathias et al. (2019) [32] | Global Public Health | Public, Environmental & Occupational Health | 1.791 | Q2 | 55.85 | 22 |

| Prati et al. (2020) [33] | Health Education & Behavior | Public, Environmental & Occupational Health | 2.623 | Q2 | 56.53 | 37 |

| Gaspar de Matos et al. (2021) [34] | Journal of Community Psychology | Psychology, Multidisciplinary | 2.297 | Q3 | 46.28 | 4 |

| Gehue et al. (2021) [35] | Journal of Affective Disorders | Psychiatry | 6.533 | Q1 | 80.07 | 4 |

| Alegría et al. (2022) [36] | American Journal of Community Psychology | Psychology, Multidisciplinary | 3.1 | Q2 | 66.3 | 7 |

| Bennett et al. (2022) [37] | Children and Youth Services Review | Social Work | 3.3 | Q1 | 92.9 | 1 |

| Koren & Mottola (2022) [38] | Journal of Community Psychology | Psychology, Multidisciplinary | 2.3 | Q3 | 49.3 | 4 |

| Cureton (2023) [39] | Children & Schools | Social Work | 1.2 | Q3 | 46.2 | 2 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).