Submitted:

15 October 2025

Posted:

16 October 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

Research Objective

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. Protocol and Registration

2.3. Eligibility Criteria

- Population: The review will include studies focusing on youth aged 14 to 35 living in rural areas of South Africa. This age range aligns with national definitions of youth and reflects the transitional life stage during which mental health vulnerabilities commonly emerge.

- Concept: Eligible studies must involve physical activity or exercise-based interventions designed to improve mental health. These may include structured or unstructured forms of physical activity such as aerobic exercise, sports, recreational play, dance, or community movement programs.

- Context: The review will focus on mental health promotion, prevention, or treatment interventions in South Africa.

| Criteria | Inclusion | Exclusion |

|---|---|---|

| Timeframe | Studies published between 2014 and 2025 | Studies published before 2014 |

| Study Design | All empirical study designs: quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods | Editorials, commentaries, and non-peer-reviewed literature |

| Population | Youth (14–35 years) in South Africa | Studies focused only on older people/children’s |

| Intervention | Any physical activity or exercise intervention | Interventions focused only on elite or professional athletes |

| Outcomes | Studies that report on mental health outcomes. | Studies that do not assess mental health outcomes |

| Language | Articles published in English | Articles published in other languages without an English translation |

2.4. Search Strategy

2.5. Study Selection

2.6. Data Extraction

- Author(s) and year of publication: To track publication trends and contextualise findings.

- Study design and methodology: To understand the research approaches and quality.

- Sample characteristics, including age, gender distribution, and geographical location, are used to describe the population.

- Setting: Details of where the intervention occurred, such as schools, community centres, or clinics.

- Type and description of physical activity intervention: Including intervention format, duration, frequency, and delivery method.

- Mental health outcomes assessed, such as depression, anxiety, stress, or other psychological well-being measures.

- Main findings and conclusions: To summarise intervention effectiveness and key insights.

3. Results

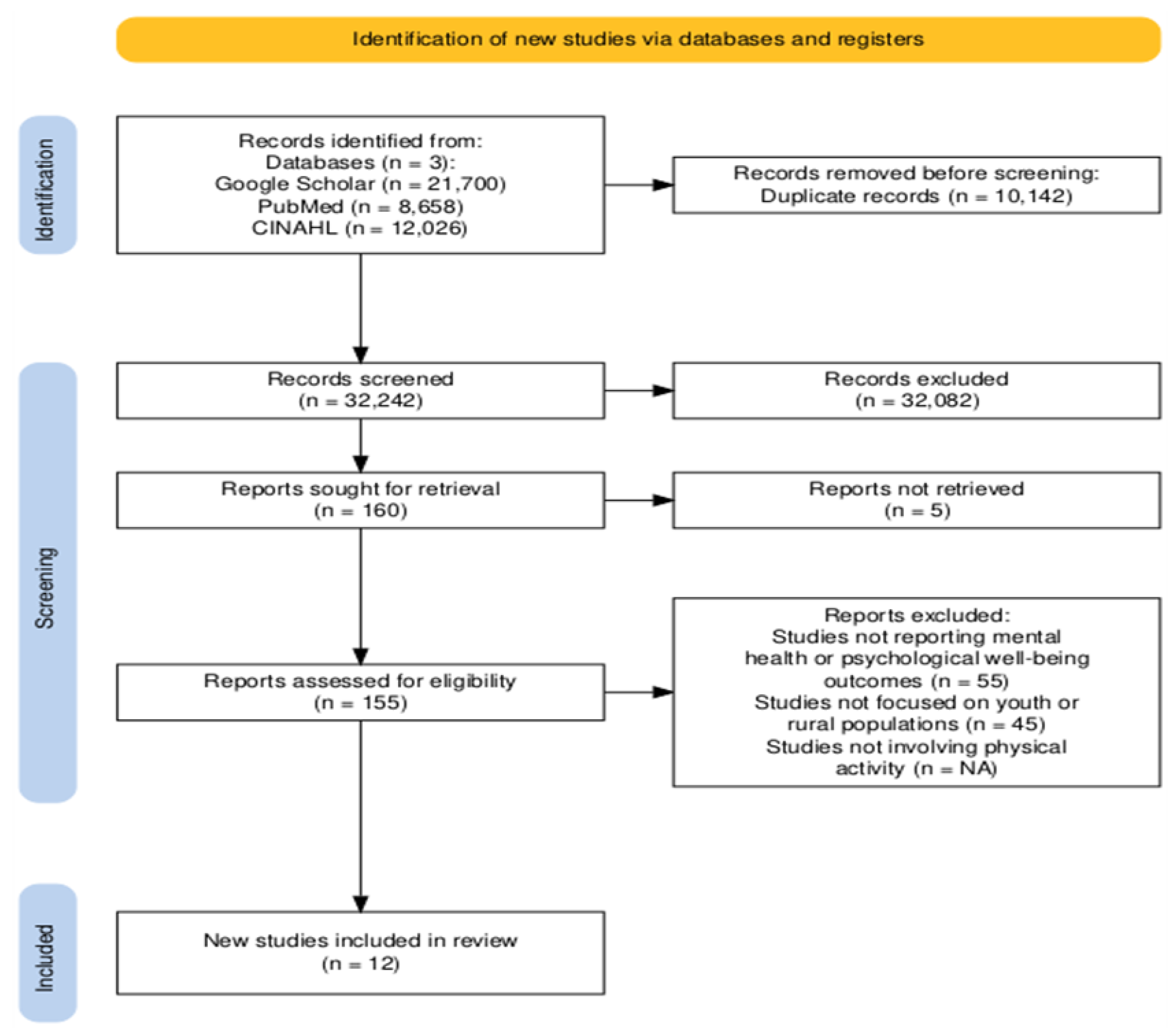

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of Included Studies

Narrative Summary of Individual Studies

- Asare [16] conducted a cross-sectional study among adolescents in KwaZulu-Natal, finding that higher physical activity levels were significantly associated with fewer behavioural problems and enhanced prosocial behaviour, underscoring PA’s role in resilience-building.

- Kinsman [24] used qualitative interviews and focus groups with rural adolescent girls in Mpumalanga. They highlighted barriers such as body image concerns, identity issues, and safety concerns, and proposed a model for increasing participation among girls.

- Micklesfield [14] examined 381 adolescents in a rural surveillance site in Mpumalanga. The study showed low levels of moderate-to-vigorous physical activity (MVPA), particularly among girls, and identified socioeconomic factors shaping PA and sedentary behaviour.

- Vancampfort [25] reviewed studies from Sub-Saharan Africa. They found policy- and community-level interventions were limited but essential for addressing the mental health needs of people with psychiatric conditions, indirectly reinforcing the importance of context-driven PA programs.

- Marais [26] interviewed South African mental health professionals and found positive attitudes toward PA as an adjunctive therapy, though most reported insufficient training and institutional support to integrate exercise into care.

- Burger [27] presented a conceptual model advocating for the integration of sport and exercise psychiatry into South Africa’s mental health systems, highlighting feasibility but calling for professional capacity-building.

- Zimu [28] developed the Nyakaza–Move-for-Health program in KwaZulu-Natal, a culturally tailored school- and community-based PA intervention. The program successfully improved adolescent engagement and demonstrated the importance of cultural adaptation.

- Siduli [29] conducted a cross-sectional survey of adolescents in the Eastern Cape. They reported positive associations between PA participation, body composition, and mental well-being, further emphasising PA’s dual health benefits.

- Draper [30] studied young women in urban Soweto and found that high sedentary behaviour correlated with poorer mental health outcomes. Although urban, the findings offer insight into likely patterns in rural youth with even fewer opportunities for PA.

- Bermejo-Cantarero [31] carried out a systematic review and meta-analysis of global RCTs in adolescents, confirming that structured PA interventions significantly improved health-related quality of life and emotional well-being.

- Kunene & Taukobong [32] examined PA levels among healthcare professionals in rural KwaZulu-Natal and found very low engagement, raising concerns about their role as promoters of active lifestyles.

- Mumbauer [33] conducted a scoping review of youth-focused interventions in South Africa and recommended culturally relevant, school-based approaches to integrate PA into broader mental health promotion strategies.

3.3. Overall Synthesis

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Key Findings

4.2. Interventions and Context-Specific Models

4.3. Health Systems and Professional Perspectives

4.4. Global Comparisons and Broader Insights

4.5. Gaps in the Literature

4.6. Implications for Research, Policy, and Practice

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| PTSD | Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder |

| PA | Physical Activity |

| RISMA-ScR | Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping Reviews |

| OSF | Open Science Framework |

References

- Burns, J.K. The mental health gap in South Africa, a human rights issue. Equal Rights Review 2011, 6, 99–113. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Mental health of adolescents. Fact sheet. Retrieved from https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/adolescent-mental-health.

- Herman, A.A.; Stein, D.J.; Seedat, S.; Heeringa, S.G.; Moomal, H.; Williams, D.R. The South African Stress and Health (SASH) study: 12-month and lifetime prevalence of common mental disorders. South African Medical Journal 2009, 99, 339–344. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kilian, S.; Burns, J.K.; Seedat, S.; Ramlall, S. Factors associated with depression and anxiety symptoms in South African adolescents living in low-resource communities. South African Journal of Psychiatry 2019, 25, a1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lund, C.; Breen, A.; Flisher, A.J.; Kakuma, R.; Corrigall, J.; Joska, J.A.; Patel, V. Poverty and common mental disorders in low- and middle-income countries: A systematic review. Social Science & Medicine 2010, 71, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, A.P.; Hetrick, S.E.; Rosenbaum, S.; Purcell, R.; Parker, A.G. Treating depression with physical activity in adolescents and young adults: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomised controlled trials. Psychological Medicine 2018, 48, 1068–1083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rebar, A.L.; Stanton, R.; Geard, D.; Short, C.; Duncan, M.J.; VanderLannotte, C. A meta-meta-analysis of the effect of physical activity on depression and anxiety in non-clinical adult populations. Health Psychology Review 2015, 9, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddle, S.J.H.; Asare, M. Physical activity and mental health in children and adolescents: A review of reviews. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2011, 45, 886–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pascoe, M.C.; Bailey, A.P.; Craike, M.; Carter, T.; Patten, R.; Stepto, N.K.; Parker, A.G. Poor reporting of physical activity and exercise interventions in youth mental health trials: A brief report. Early Intervention in Psychiatry 2021, 15, 1414–1422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennehy, J.; Cameron, M.; Phillips, T.; Kolbe-Alexander, T. Physical activity interventions among youth living in rural and remote areas: A systematic review. Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health 2024, 48, 100137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, C.E.; Cook, C.J.; Redinger, S.; Rochat, T.; Prioreschi, A.; Rae, D.E.; Ware, L.J.; Lye, S.J.; Norris, S.A. Cross-sectional associations between mental health indicators and social vulnerability, with physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep in urban African young women. International Journal of Behavioural Nutrition and Physical Activity 2022, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Zyl, S.; Van der Merwe, M.; Smith, M. Youth mental health and access to services in rural areas of South Africa. South African Journal of Psychology 2021, 51, 519–530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mendenhall, E.; De Silva, M.J.; Hanlon, C.; Petersen, I.; Shidhaye, R.; Jordans, M.; Tomlinson, M. Acceptability and feasibility of using non-specialist health workers to deliver mental health care: Stakeholder perceptions from the PRIME district sites in Ethiopia, India, Nepal, South Africa, and Uganda. Social Science & Medicine 2014, 118, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Micklesfield, L.K.; Pedro, T.M.; Kahn, K.; Kinsman, J.; Pettifor, J.M.; Tollman, S.; Norris, S.A. Physical Activity and Sedentary Behaviour Among Adolescents in Rural South Africa: Levels, Patterns, and Correlates. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorsdhal, K.; Flisher, A.J.; Wilson, Z.; Stein, D.J. Explanatory models of mental disorders and treatment practices among traditional healers in Mpumalanga, South Africa. African Journal of Psychiatry 2010, 13, 284–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asare, K.; Ntlantsana, V.; Ranjit, K.; Tomita, A. Relationship between physical activity and behaviour challenges of adolescents in South Africa. South African Journal of Psychiatry 2023, 29, 2124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tomlinson, M.; Swartz, L.; Kruger, L.M.; Gureje, O. Manifestations of mental disorders in sub-Saharan Africa: An overview. African Journal of Psychiatry 2009, 12, 104–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arksey, H.; O’Malley, L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology 2005, 8, 19–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levac, D.; Colquhoun, H.; O’Brien, K.K. Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science 2010, 5, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munyangane, O.L.; Thaga, L.F.; Vele, R. Exercise as therapy: A scoping review of physical activity interventions for mental health among rural youth in South Africa [Protocol]. Open Science Framework, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Bramer, W.M.; Giustini, D.; de Jonge, G.B.; Holland, L.; Bekhuis, T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in EndNote. Journal of the Medical Library Association 2017, 105, 84–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A., Eds. Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions (Version 6.4); Cochrane, 2022.

- Kinsman, J.; Norris, S.A.; Kahn, K.; Twine, R.; Riggle, K.; Goudge, J. A model for promoting physical activity among rural South African youth: A qualitative case study of the Agincourt health and socio-demographic surveillance site. BMC Public Health 2015, 15, 318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vancampfort, D.; Stubbs, B.; De Hert, M.; Du Plessis, C.; Gbiri, C.A.O.; Kibet, J.; Mugisha, J. A systematic review of physical activity policy recommendations and interventions for people with mental health problems in Sub-Saharan African countries. Pan African Medical Journal 2017, 26, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marais, B.S. South African mental healthcare providers’ views about exercise for people with mental illness. South African Journal of Psychiatry 2024, 30, 2227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Burger, J.W.; Mafuze, B.; Brooker, J.; Patricios, J.S. Championing mental health: sport and exercise psychiatry for low- and middle-income countries using a model from South Africa. British Journal of Sports Medicine 2024, 58, 519–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zimu, P.M.; van Heerden, H.J.; Grace, J.M. Nyakaza-Move-for-Health: A culturally tailored physical activity intervention for adolescents in South Africa using the intervention mapping protocol. Journal of Primary Care & Community Health 2024, 15, Article–21501319241278849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siduli, Z.; van Gent, M.M.; Van Niekerk, R.L. Relationship between body composition, physical activity, and mental well-being in Eastern Cape adolescents, South Africa. African Journal for Physical Activity and Health Sciences 2025, 31, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Draper, C.E.; Cook, C.J.; Redinger, S.; Rochat, T.; Prioreschi, A.; Rae, D.E.; Ware, L.J.; Lye, S.J.; Norris, S.A. Cross-sectional associations between mental health indicators and social vulnerability, with physical activity, sedentary behaviour and sleep in urban African young women. International Journal of Behavioral Nutrition and Physical Activity 2022, 19, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bermejo-Cantarero, A.; Sánchez-López, M.; García-González, J. Are physical activity interventions effective in improving health-related quality of life and emotional well-being in adolescents? Sports Health 2024, 16, 246–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kunene, S.H.; Taukobong, N.P. Level of physical activity of health professionals in a district hospital in KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. South African Journal of Physiotherapy 2015, 71, 234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumbauer, A.E.; D’Sa, M.; Patel, V. Targeting youth mental health in a demographically young country: A scoping review focused on South Africa. Journal of Child and Adolescent Mental Health 2024, 36, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tweed, L.M.; Rogers, E.N.; Kinnafick, F.E. Literature on peer-based community physical activity programmes for mental health service users: A scoping review. Health Psychology Review 2021, 15, 287–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Author (Year) | Design | Location | Sample and Sampling Technique | Instrument | Outcomes | Intervention |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Asare et al. (2023) | Cross-sectional | South Africa – KwaZulu-Natal | 187 adolescents; convenience sample | Strengths & Difficulties Questionnaire, PA recall | Behavioural challenges, prosocial behaviour | None (PA levels and mental health correlation) |

| Kinsman et al. (2015) | Qualitative (model development) | South Africa – rural Mpumalanga | Adolescent girls; purposive sampling | Interviews, FGDs | Barriers to activity, identity, and body image | Model for promoting PA among rural girls |

| Micklesfield et al. (2014) | Cross-sectional | South Africa – Agincourt HDSS, Mpumalanga | 381 adolescents; random cluster sampling | Self-reported PA, SES, and BMI | MVPA, sedentary behaviour | None (baseline behaviour analysis) |

| Vancampfort et al. (2017) | Systematic review | Sub-Saharan Africa | Studies across SSA countries | Not specified | Mental health outcomes in people with MH problems | Policy-level and community interventions |

| Marais (2024) | Qualitative (interviews) | South Africa – National | Mental healthcare providers: purposive sampling | Semi-structured interviews | Attitudes toward exercise for mental illness | Advocacy for integrating PA into mental healthcare |

| Burger et al. (2024) | Commentary/Model proposal | South Africa | N/A – conceptual paper | Not applicable | Advocacy and implementation feasibility | Proposes an SA-based sport and exercise psychiatry model for LMICs |

| Zimu et al. (2024) | Intervention development study | South Africa – KwaZulu-Natal | Adolescents, community and school sampling | Intervention Mapping Protocol | Physical activity engagement, cultural appropriateness | “Nyakaza-Move-for-Health” – culturally tailored adolescent PA programme |

| Siduli et al. (2025) | Cross-sectional | South Africa – Eastern Cape | Adolescents (n ≈ 300); stratified sampling | Body composition measures, PA recall, mental well-being questionnaire | Mental well-being, PA levels, and BMI | Observational – no direct intervention |

| Draper et al. (2022) | Cross-sectional | South Africa – Soweto (urban) | Young women (18–25 years); cohort-based sampling | GHQ-28, accelerometers, sleep logs | Mental health indicators, PA/sedentary behaviour | Observational: highlights associations |

| Bermejo-Cantarero et al. (2024) | Systematic review & meta-analysis | Global | RCTs in children and adolescents | HRQoL scales (PedsQL, SF-36, etc.) | Health-related quality of life (HRQoL) | Evaluated the impact of PA interventions on HRQoL |

| Kunene & Taukobong (2015) | Cross-sectional | South Africa – KwaZulu-Natal | Health professionals in rural district hospital (n=63); convenience sampling | IPAQ – short form | Physical activity levels among health workers | Observational – no intervention |

| Mumbauer et al. (2024) | Scoping review | South Africa | Youth-focused studies (15–24 years) | Review of national data & literature | Youth mental health trends, interventions | Recommends integrated, culturally relevant mental health/PA models |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).