Submitted:

30 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

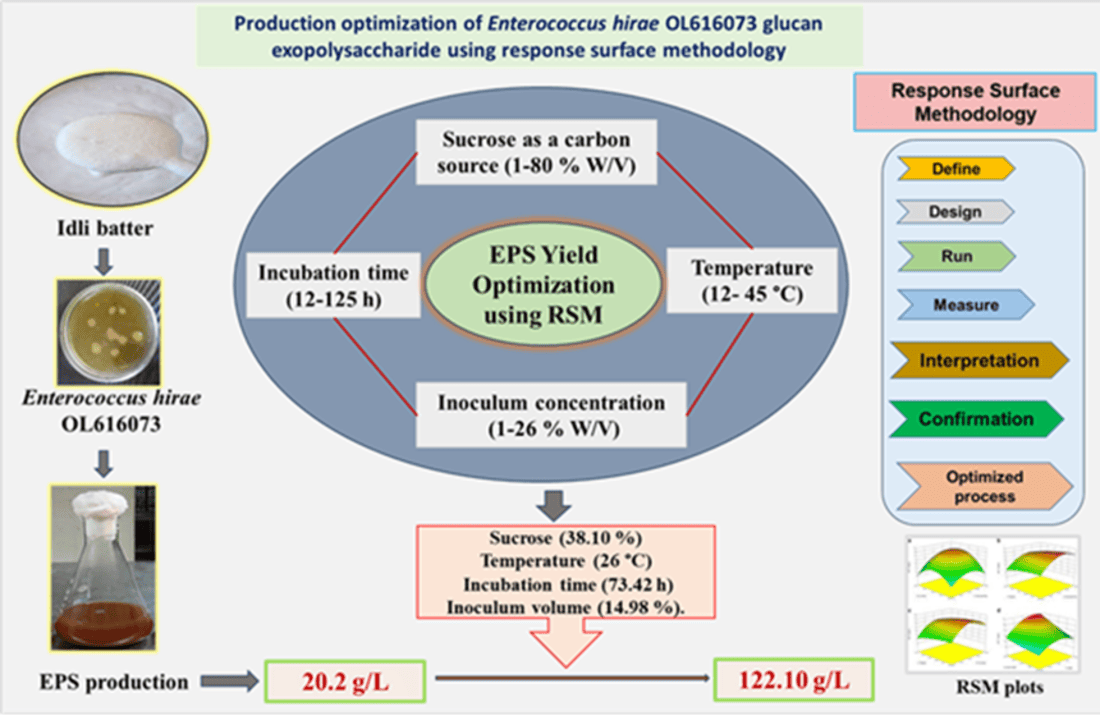

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Microorganism and Culture Maintenance

2.2. Growth Profile and Glucan Synthesis

2.3. Inoculum Preparation

2.4. Preliminary Screening of Parameters Using One-Factor-at-a-Time (OFAT) Method

2.5. Extraction, Purification and Quantification of Glucan

2.6. Estimation of Biomass (Cell Dry Weight)

2.7. Optimization of Glucan Production and Cell Biomass Using RSM

2.8. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

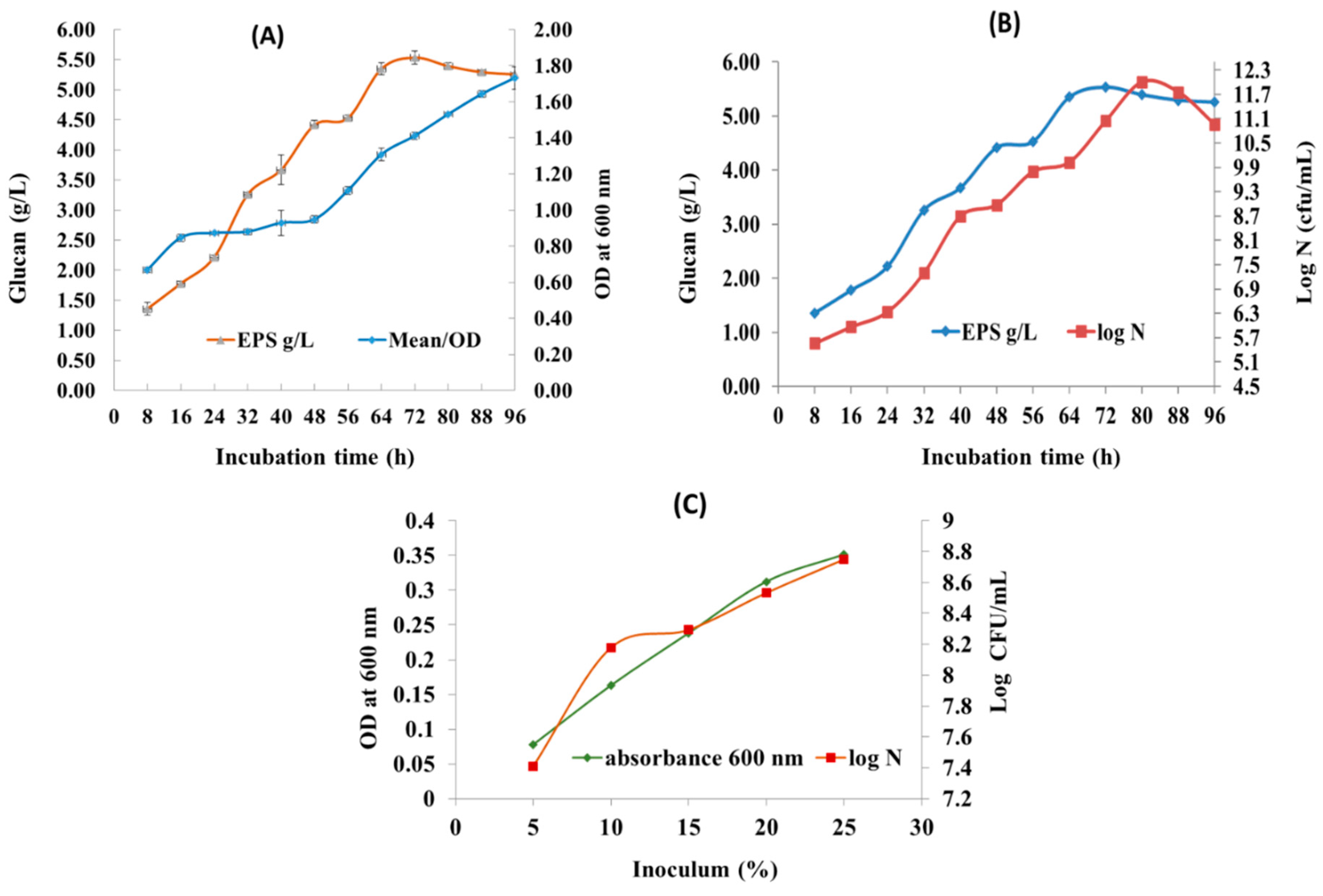

3.1. Growth Profile and Glucan Production

3.2. Variables Affecting Glucan Produced by Enterococcus hirae OL616073

3.2.1. One Factor at a Time (OFAT) Optimization

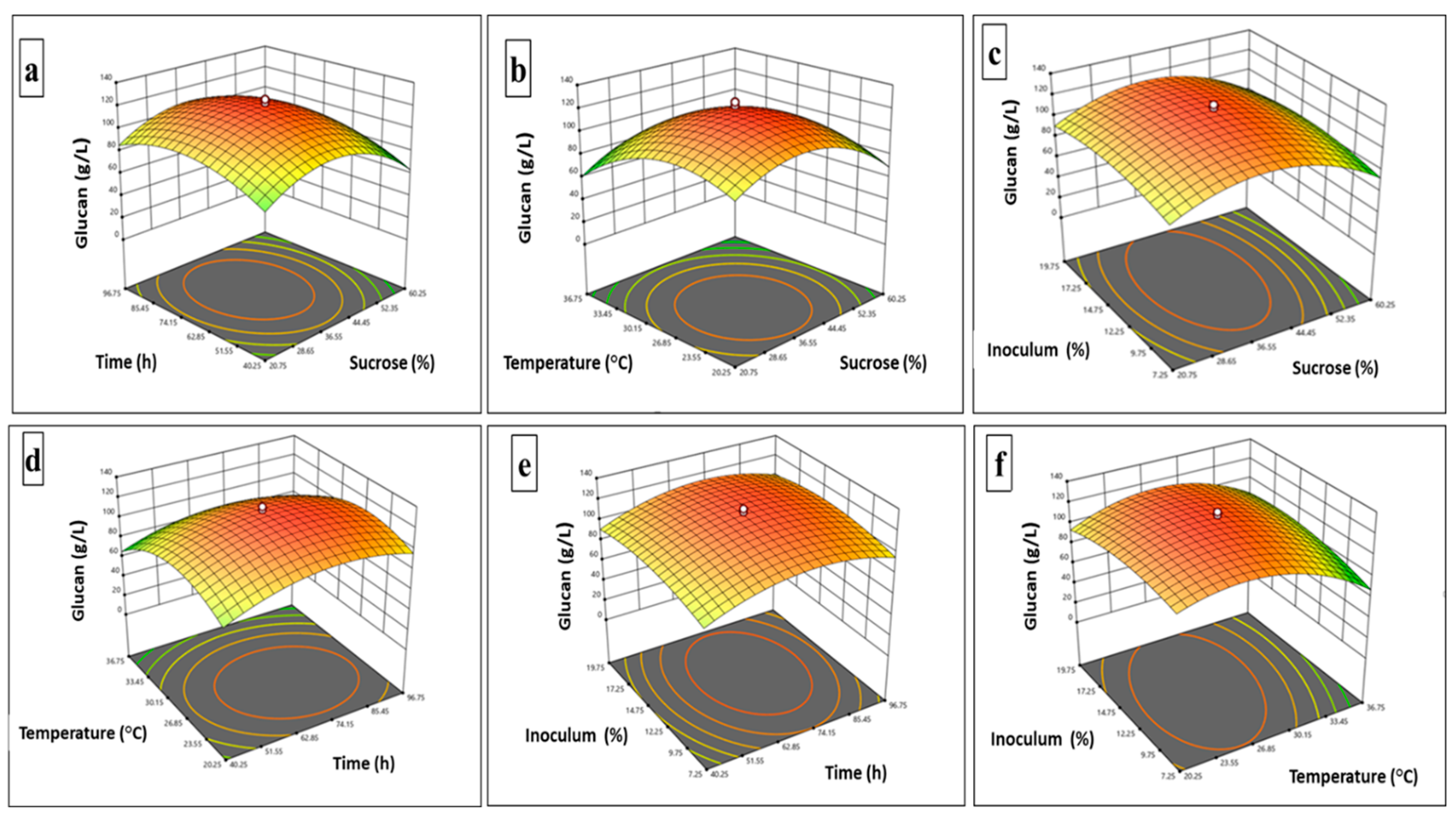

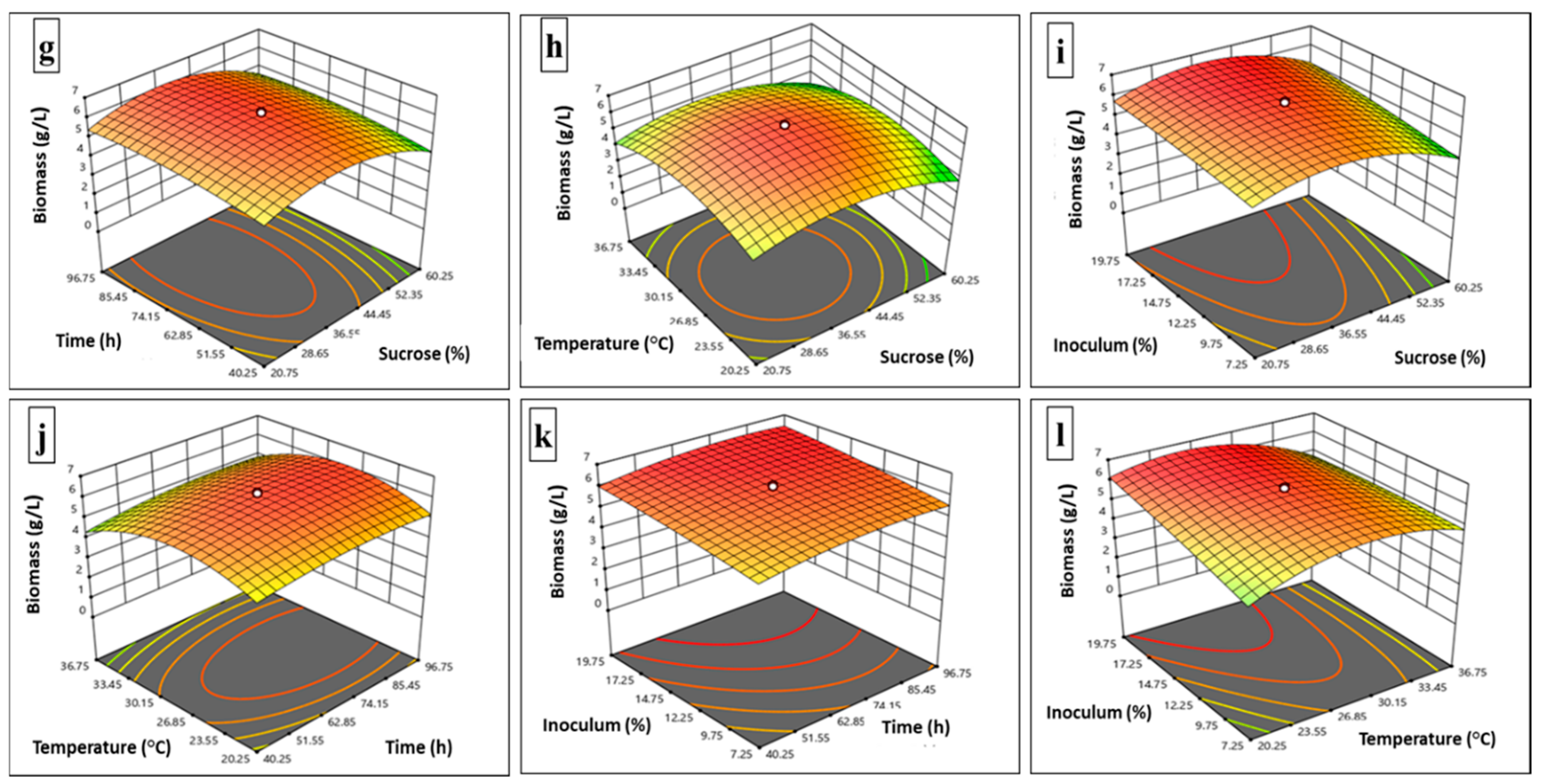

3.3. RSM (Central Composite Design) for Glucan and Biomass Production

4. Economical Significance of Glucan EPS Optimization

5. Conclusion

Authors contribution

Declaration of competing interest

Acknowledgement

References

- Vinothini, G.; Latha, S.; Arulmozhi, M.; Dhanasekaran, D. Statistical Optimization, Physio-Chemical and Bio-Functional Attributes of a Novel Exopolysaccharide from Probiotic Streptomyces Griseorubens GD5. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 134, 575–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Korcz, E.; Varga, L. Exopolysaccharides from Lactic Acid Bacteria: Techno-Functional Application in the Food Industry. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2021, 110, 375–384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ale, E.C.; Irazoqui, J.M.; Ale, A.; Peralta, G.H.; Puntillo, M.; Burns, P.; Correa Olivar, G.; Cazenave, J.; Bergamini, C. V; Amadio, A.F. Protective Role of Limosilactobacillus Fermentum Lf2 and Its Exopolysaccharides (EPS) in a TNBS-Induced Chronic Colitis Mouse Model. Fermentation 2024, 10, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Asgher, M.; Qamar, S.A.; Iqbal, H.M.N. Microbial Exopolysaccharide-Based Nano-Carriers with Unique Multi-Functionalities for Biomedical Sectors. Biologia (Bratisl). 2021, 76, 673–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitake, D.; Tiwari, S.; Shah, I.A.; Devi, P.B.; Delattre, C.; Reddy, G.B.; Shetty, P.H. Antipathogenic Potentials of Exopolysaccharides Produced by Lactic Acid Bacteria and Their Food and Health Applications. Food Control 2023, 109850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamidi, M.; Mirzaei, R.; Delattre, C.; Khanaki, K.; Pierre, G.; Gardarin, C.; Petit, E.; Karimitabar, F.; Faezi, S. Characterization of a New Exopolysaccharide Produced by Halorubrum Sp. TBZ112 and Evaluation of Its Anti-Proliferative Effect on Gastric Cancer Cells. 3 Biotech 2019, 9, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dilna, S.V.; Surya, H.; Aswathy, R.G.; Varsha, K.K.; Sakthikumar, D.N.; Pandey, A.; Nampoothiri, K.M. Characterization of an Exopolysaccharide with Potential Health-Benefit Properties from a Probiotic Lactobacillus Plantarum RJF4. LWT - Food Sci. Technol. 2015, 64, 1179–1186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, A.; Yang, Z. Characterization and Bioactivities of an Exopolysaccharide Produced by Lactobacillus Plantarum YW32. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2015, 74, 119–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, K.; Li, W.; Rui, X.; Chen, X.; Jiang, M.; Dong, M. Characterization of a Novel Exopolysaccharide with Antitumor Activity from Lactobacillus Plantarum 70810. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2014, 63, 133–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, F.; Torres, C.A. V; Reis, M.A.M. Engineering Aspects of Microbial Exopolysaccharide Production. Bioresour. Technol. 2017, 245, 1674–1683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gan, L.; Huang, X.; He, Z.; He, T. Exopolysaccharide Production by Salt-Tolerant Bacteria: Recent Advances, Current Challenges, and Future Prospects. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 130731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elmansy, E.A.; Elkady, E.M.; Asker, M.S.; Abdallah, N.A.; Khalil, B.E.; Amer, S. k Improved Production of Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum RO30 Exopolysaccharide (REPS) by Optimization of Process Parameters through Statistical Experimental Designs. BMC Microbiol. 2023, 23, 361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kavitake, D.; Tiwari, S.; Devi, P.B.; Shah, I.A.; Reddy, G.B.; Shetty, P.H. Production, Purification, and Functional Characterization of Glucan Exopolysaccharide Produced by Enterococcus Hirae Strain OL616073 of Fermented Food Origin. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 129105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koko, M.Y.F.; Hassanin, H.A.M.; Qi, B.; Han, L.; Lu, K.; Rokayya, S.; Harimana, Y.; Zhang, S.; Li, Y. Hydrocolloids as Promising Additives for Food Formulation Consolidation: A Short Review. Food Rev. Int. 2023, 39, 1433–1439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Garcinuño, Á.; Tabernero, A.; Sánchez-Álvarez, J.M.; Galán, M.A.; Martin Del Valle, E.M. Effect of Bacteria Type and Sucrose Concentration on Levan Yield and Its Molecular Weight. Microb. Cell Fact. 2017, 16, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rabha, B.; Nadra, R.-S.; Ahmed, B. Effect of Some Fermentation Substrates and Growth Temperature on Exopolysaccharide Production by Streptococcus Thermophilus BN1. Int. J. Biosci. Biochem. Bioinforma. 2012, 2, 44–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Mokarram, R.R.; Khiabani, M.S.; Bari, M.R.; Khaledabad, M.A. Exopolysaccharides Production by Lactobacillus Acidophilus LA5 and Bifidobacterium Animalis Subsp. Lactis BB12: Optimization of Fermentation Variables and Characterization of Structure and Bioactivities. Int. J. Biol. Macromol.

- Oleksy-Sobczak, M.; Klewicka, E.; Piekarska-Radzik, L. Exopolysaccharides Production by Lactobacillus Rhamnosus Strains – Optimization of Synthesis and Extraction Conditions. LWT 2020, 122, 109055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badel, S.; Bernardi, T.; Michaud, P. New Perspectives for Lactobacilli Exopolysaccharides. Biotechnol. Adv. 2011, 29, 54–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madhuri, K. V; Prabhakar, K.V. Microbial Exopolysaccharides: Biosynthesis and Potential Applications. Orient. J. Chem. 2014, 30, 1401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kavitake, D.; Devi, P.B.; Singh, S.P.; Shetty, P.H. Characterization of a Novel Galactan Produced by Weissella Confusa KR780676 from an Acidic Fermented Food. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 86, 681–689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dubois, M.; Gilles, K.A.; Hamilton, J.K.; Rebers, P.A.; Smith, F. Colorimetric Method for Determination of Sugars and Related Substances. Anal. Chem. 1956, 28, 350–356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezhil, I.; Belur, P.D.; Saidutta, M.B. Production Optimization of a New Exopolysaccharide from Bacillus Methylotrophicus and Its Characterization. Int. J. Biotechnol. Biochem. 2015, 11, 21–39. [Google Scholar]

- Raza, W.; Makeen, K.; Wang, Y.; Xu, Y.; Qirong, S. Optimization, Purification, Characterization and Antioxidant Activity of an Extracellular Polysaccharide Produced by Paenibacillus Polymyxa SQR-21. Bioresour. Technol. 2011, 102, 6095–6103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pham, P.L.; Dupont, I.; Roy, D.; Lapointe, G.; Cerning, J. Production of Exopolysaccharide by Lactobacillus Rhamnosus R and Analysis of Its Enzymatic Degradation during Prolonged Fermentation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2000, 66, 2302–2310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baruah, R.; Maina, N.H.; Katina, K.; Juvonen, R.; Goyal, A. International Journal of Food Microbiology Functional Food Applications of Dextran from Weissella Cibaria RBA12 from Pummelo ( Citrus Maxima ). Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2017, 242, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco, S.; Årsköld, E.; Paese, M.; Grage, H.; Irastorza, A.; Rådström, P.; Van Niel, E.W.J. Environmental Factors Influencing Growth of and Exopolysaccharide Formation by Pediococcus Parvulus 2.6. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2006, 111, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gamar, L.; Blondeau, K.; Simonet, J. Physiological Approach to Extracellular Polysaccharide Production by Lactobacillus Rhamnosus Strain C83. J. Appl. Microbiol. 1997, 83, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Castellane, T.C.L.; Campanharo, J.C.; Colnago, L.A.; Coutinho, I.D.; Lopes, É.M.; Lemos, M.V.F.; de Macedo Lemos, E.G. Characterization of New Exopolysaccharide Production by Rhizobium Tropici during Growth on Hydrocarbon Substrate. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 96, 361–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welman, A.D.; Maddox, I.S. Exopolysaccharides from Lactic Acid Bacteria: Perspectives and Challenges. Trends Biotechnol. 2003, 21, 269–274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jenny Angel, S.; Vidyadharani, G.; Santhosh, S.; Dhandapani, R. Optimization and Characterisation of Thermo Stable Exopolysaccharide Produced from Bacillus Licheniformis WSF-1 Strain. J. Polym. Environ. 2018, 26, 3824–3833. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, C.; Ma, S.; Chang, F.; Xue, W. Efficient Production of Pullulan by Aureobasidium Pullulans Grown on Mixtures of Potato Starch Hydrolysate and Sucrose. Brazilian J. Microbiol. 2017, 48, 180–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sawale, S.D.; Lele, S.S. Statistical Optimization of Media for Dextran Production by Leuconostoc Sp., Isolated from Fermented Idli Batter. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2010, 19, 471–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rogalski, E.; Ehrmann, M.A.; Vogel, R.F. Intraspecies Diversity and Genome-Phenotype-Associations in Fructilactobacillus Sanfranciscensis. Microbiol. Res. 2021, 243, 126625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Dai, X.; Jin, H.; Man, C.; Jiang, Y. The Effect of Optimized Carbon Source on the Synthesis and Composition of Exopolysaccharides Produced by Lactobacillus Paracasei. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 4023–4032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, P.-T.; Nguyen, T.-T.; Bui, D.-C.; Hong, P.-T.; Hoang, Q.-K.; Nguyen, H.-T. Exopolysaccharide Production by Lactic Acid Bacteria: The Manipulation of Environmental Stresses for Industrial Applications. AIMS Microbiol. 2020, 6, 451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, M.R.; da Silva, R.S.S.F.; Buzato, J.B.; Celligoi, M.A.P.C. Study of Levan Production by Zymomonas Mobilis Using Regional Low-Cost Carbohydrate Sources. Biochem. Eng. J. 2007, 37, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doelle, H.W.; Greenfield, P.F. Fermentation Pattern of Zymomonas Mobilis at High Sucrose Concentrations. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 1985, 22, 411–415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, A.; Kanwar, S.S. Optimization of Exopolysaccharide Production by Response Surface Methodology from Enterococcus Faecium Isolated from the Fermented Foods of Western Himalaya. Int. J. Sci. Res. Biol. Sci. 2019, 6, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zanzan, M.; Ezzaky, Y.; Achemchem, F.; Elmoslih, A.; Hamadi, F.; Hasnaoui, A.; Ali, M.A. Optimisation of Thermostable Exopolysaccharide Production from Enterococcus Mundtii A2 Isolated from Camel Milk and Its Structural Characterisation. Int. Dairy J. 2023, 147, 105718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razack, S.A.; Velayutham, V.; Thangavelu, V. Influence of Various Parameters on Exopolysaccharide Production from Bacillus Subtilis. Int. J. ChemTech Res. 2013, 5, 2221–2228. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Wang, X.; Pu, H.; Liu, S.; Kan, J.; Jin, C. Recent Advances in Endophytic Exopolysaccharides: Production, Structural Characterization, Physiological Role and Biological Activity. Carbohydr. Polym. 2017, 157, 1113–1124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Borah, D.; Nainamalai, S.; Gopalakrishnan, S.; Rout, J.; Alharbi, N.S.; Alharbi, S.A.; Nooruddin, T. Biolubricant Potential of Exopolysaccharides from the Cyanobacterium Cyanothece Epiphytica. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2018, 102, 3635–3647. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengoa, A.A.; Llamas, M.G.; Iraporda, C.; Dueñas, M.T.; Abraham, A.G.; Garrote, G.L. Impact of Growth Temperature on Exopolysaccharide Production and Probiotic Properties of Lactobacillus Paracasei Strains Isolated from Kefir Grains. Food Microbiol. 2018, 69, 212–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wongsuphachat, W.; Maneerat, S. Optimization of Exopolysaccharides Production by Weissella Confusa NH 02 Isolated from Thai Fermented Sausages. Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol. 2010, 32. [Google Scholar]

- Polak-Berecka, M.; Waśko, A.; Kubik-Komar, A. Optimization of Culture Conditions for Exopolysaccharide Production by a Probiotic Strain of Lactobacillus Rhamnosus E/N. Polish J. Microbiol. 2014, 63, 253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslim, B.; Yüksekdag˘, Z.N.; Beyatli, Y.; Mercan, N. Exopolysaccharide Production by Lactobacillus Delbruckii Subsp. Bulgaricus and Streptococcus Thermophilus Strains under Different Growth Conditions. World J. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 21, 673–677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arous, F.; Azabou, S.; Jaouani, A.; Zouari-Mechichi, H.; Nasri, M.; Mechichi, T. Biosynthesis of Single-Cell Biomass from Olive Mill Wastewater by Newly Isolated Yeasts. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2016, 23, 6783–6792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Zhao, Z.; Chen, S.-F.; Li, Y.-Q. Optimization for the Production of Exopolysaccharide from Fomes Fomentarius in Submerged Culture and Its Antitumor Effect in Vitro. Bioresour. Technol. 2008, 99, 3187–3194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, R.; Zhou, Z.; Ma, Y.; Du, K.; Sun, M.; Zhang, H.; Tu, H.; Jiang, X.; Lu, J.; Tu, L. Production of the Exopolysaccharide from Lactiplantibacillus Plantarum YT013 under Different Growth Conditions: Optimum Parameters and Mathematical Analysis. Int. J. Food Prop. 2023, 26, 1941–1952. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, B.; Song, Q.; Zhao, F.; Han, Y.; Zhou, Z. Production Optimization, Partial Characterization and Properties of an Exopolysaccharide from Lactobacillus Sakei L3. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2019, 141, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnama Vosough, P.; Habibi Najafi, M.B.; Edalatian Dovom, M.R.; Javadmanesh, A.; Mayo, B. Evaluation of Antioxidant, Antibacterial and Cytotoxicity Activities of Exopolysaccharide from Enterococcus Strains Isolated from Traditional Iranian Kishk. J. Food Meas. Charact. 2021, 15, 5221–5230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farinazzo, F.S.; Fernandes, M.T.C.; Mauro, C.S.I.; Garcia, S. Statistical Optimization of Exopolysaccharide Production by Leuconostoc Pseudomesenteroides JF17 from Native Atlantic Forest Juçara Fruit. Prep. Biochem. Biotechnol. 2022, 52, 245–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Derdak, R.; Sakoui, S.; Pop, O.L.; Vodnar, D.C.; Addoum, B.; Teleky, B.-E.; Elemer, S.; Elmakssoudi, A.; Suharoschi, R.; Soukri, A. Optimisation and Characterization of α-D-Glucan Produced by Bacillus Velezensis RSDM1 and Evaluation of Its Protective Effect on Oxidative Stress in Tetrahymena Thermophila Induced by H2O2. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 222, 3229–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rao, B.P.; Sudharsan, K.; Sekaran, R.; Mandal, A.B. Characterization of Exopolysaccharide from Bacillus Amyloliquefaciens BPRGS for Its Bioflocculant Activity. Int. J. Sci. Eng. Res 2013, 4, 1696–1704. [Google Scholar]

- Niknezhad, S.V.; Morowvat, M.H.; Najafpour Darzi, G.; Iraji, A.; Ghasemi, Y. Exopolysaccharide from Pantoea Sp. BCCS 001 GH Isolated from Nectarine Fruit: Production in Submerged Culture and Preliminary Physicochemical Characterizations. Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2018, 27, 1735–1746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laspidou, C.S.; Rittmann, B.E. A Unified Theory for Extracellular Polymeric Substances, Soluble Microbial Products, and Active and Inert Biomass. Water Res. 2002, 36, 2711–2720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, D.; Jiao, Y.; Wu, J.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Q. Optimization of EPS Production and Characterization by a Halophilic Bacterium, Kocuria Rosea ZJUQH from Chaka Salt Lake with Response Surface Methodology. Molecules 2017, 22, 814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Independent variables | Coded levels of independent variables | ||||

| −2 | −1 | 0 | +1 | +2 | |

| Sucrose (%) | 1 | 20.75 | 40.5 | 60.25 | 80 |

| Time (h) | 12 | 40.25 | 68.5 | 96.75 | 125 |

| Temperature(°C) | 12 | 20.25 | 28.5 | 36.77 | 45 |

| Inoculum (%) | 1 | 7.25 | 13.5 | 19.75 | 26 |

| Independent variables | Dependent variables | ||||||

| Std | Run | Sucrose (%) | Time (h) | Temperature (°C) |

Inoculum (%) | EPS (g/L) | Biomass (g/L) |

| 16 | 1 | 60.25 | 96.75 | 36.75 | 19.75 | 39.23 | 3.32 |

| 3 | 2 | 20.75 | 96.75 | 20.25 | 7.25 | 76.5 | 3.25 |

| 5 | 3 | 20.75 | 40.25 | 36.75 | 7.25 | 27.25 | 3.61 |

| 4 | 4 | 60.25 | 96.75 | 20.25 | 7.25 | 51.67 | 2.5 |

| 26 | 5 | 40.5 | 68.5 | 28.5 | 13.5 | 117.2 | 6.27 |

| 7 | 6 | 20.75 | 96.75 | 36.75 | 7.25 | 31.6 | 4.2 |

| 29 | 7 | 40.5 | 68.5 | 28.5 | 13.5 | 122.6 | 6.18 |

| 6 | 8 | 60.25 | 40.25 | 36.75 | 7.25 | 18.65 | 2.8 |

| 12 | 9 | 60.25 | 96.75 | 20.25 | 19.75 | 45.67 | 4.77 |

| 17 | 10 | 1 | 68.5 | 28.5 | 13.5 | 13.78 | 2.6 |

| 20 | 11 | 40.5 | 125 | 28.5 | 13.5 | 61.34 | 5.8 |

| 21 | 12 | 40.5 | 68.5 | 12 | 13.5 | 45.25 | 2.48 |

| 27 | 13 | 40.5 | 68.5 | 28.5 | 13.5 | 118.3 | 5.98 |

| 28 | 14 | 40.5 | 68.5 | 28.5 | 13.5 | 119.21 | 6.26 |

| 23 | 15 | 40.5 | 68.5 | 28.5 | 1 | 77.12 | 5.12 |

| 2 | 16 | 60.25 | 40.25 | 20.25 | 7.25 | 39.24 | 2.3 |

| 18 | 17 | 80 | 68.5 | 28.5 | 13.5 | 2.2 | 0.98 |

| 19 | 18 | 40.5 | 12 | 28.5 | 13.5 | 37.25 | 4.2 |

| 8 | 19 | 60.25 | 96.75 | 36.75 | 7.25 | 18.12 | 3.27 |

| 10 | 20 | 60.25 | 40.25 | 20.25 | 19.75 | 31.25 | 4.53 |

| 24 | 21 | 40.5 | 68.5 | 28.5 | 26 | 89.27 | 6.3 |

| 11 | 22 | 20.75 | 96.75 | 20.25 | 19.75 | 63.24 | 5.32 |

| 25 | 23 | 40.5 | 68.5 | 28.5 | 13.5 | 116.3 | 5.8 |

| 15 | 24 | 20.75 | 96.75 | 36.75 | 19.75 | 45.23 | 4.06 |

| 30 | 25 | 40.5 | 68.5 | 28.5 | 13.5 | 125.56 | 6.2 |

| 22 | 26 | 40.5 | 68.5 | 45 | 13.5 | 2.23 | 1.34 |

| 9 | 27 | 20.75 | 40.25 | 20.25 | 19.75 | 54.19 | 4.9 |

| 13 | 28 | 20.75 | 40.25 | 36.75 | 19.75 | 43.27 | 3.8 |

| 1 | 29 | 20.75 | 40.25 | 20.25 | 7.25 | 62.22 | 3.4 |

| 14 | 30 | 60.25 | 40.25 | 36.75 | 19.75 | 34.28 | 3.1 |

| Source | Sum of squares | df | Mean Square | F-Value | P-Value | |

| Model | 40627.49 | 14 | 2901.96 | 169.09 | < 0.0001 | significant |

| A-Sucrose | 919.46 | 1 | 919.46 | 53.58 | < 0.0001 | |

| B-Time | 495.86 | 1 | 495.86 | 28.89 | < 0.0001 | |

| C-Temperature | 2654.20 | 1 | 2654.20 | 154.66 | < 0.0001 | |

| D-Inoculum | 127.93 | 1 | 127.93 | 7.45 | 0.0155 | |

| AB | 0.1661 | 1 | 0.1661 | 0.0097 | 0.9229 | |

| AC | 164.16 | 1 | 164.16 | 9.57 | 0.0074 | |

| AD | 12.94 | 1 | 12.94 | 0.7541 | 0.3989 | |

| BC | 97.27 | 1 | 97.27 | 5.67 | 0.0310 | |

| BD | 0.0014 | 1 | 0.0014 | 0.0001 | 0.9929 | |

| CD | 646.05 | 1 | 646.05 | 37.64 | < 0.0001 | |

| A² | 21061.34 | 1 | 21061.34 | 1227.22 | < 0.0001 | |

| B² | 8289.07 | 1 | 8289.07 | 482.99 | < 0.0001 | |

| C² | 15501.16 | 1 | 15501.16 | 903.23 | < 0.0001 | |

| D² | 2177.04 | 1 | 2177.04 | 126.85 | < 0.0001 | |

| Residual | 257.43 | 15 | 17.16 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 194.83 | 10 | 19.48 | 1.56 | 0.3267 | not significant |

| Pure Error | 62.60 | 5 | 12.52 | |||

| Cor Total | 40884.92 | 29 |

| Std. Dev. | 4.14 | R² | 0.9937 |

| Mean | 57.64 | Adjusted R² | 0.9878 |

| C.V. % | 7.19 | Predicted R² | 0.9703 |

| Adeq Precision | 42.0645 |

| Source | Sum of squares | df | Mean Square | F-Value | P-Value | |

| Model | 68.46 | 14 | 4.89 | 66.82 | < 0.0001 | significant |

| A-Sucrose | 3.52 | 1 | 3.52 | 48.09 | < 0.0001 | |

| B-Time | 1.24 | 1 | 1.24 | 16.91 | 0.0009 | |

| C-Temperature | 1.08 | 1 | 1.08 | 14.75 | 0.0016 | |

| D-Inoculum | 4.89 | 1 | 4.89 | 66.78 | < 0.0001 | |

| AB | 6.250E-06 | 1 | 6.250E-06 | 0.0001 | 0.9927 | |

| AC | 0.0105 | 1 | 0.0105 | 0.1436 | 0.7101 | |

| AD | 0.0946 | 1 | 0.0946 | 1.29 | 0.2735 | |

| BC | 0.0431 | 1 | 0.0431 | 0.5884 | 0.4549 | |

| BD | 0.0001 | 1 | 0.0001 | 0.0008 | 0.9782 | |

| CD | 3.68 | 1 | 3.68 | 50.25 | < 0.0001 | |

| A² | 31.15 | 1 | 31.15 | 425.72 | < 0.0001 | |

| B² | 1.90 | 1 | 1.90 | 25.97 | 0.0001 | |

| C² | 29.42 | 1 | 29.42 | 402.09 | < 0.0001 | |

| D² | 0.2016 | 1 | 0.2016 | 2.75 | 0.1177 | |

| Residual | 1.10 | 15 | 0.0732 | |||

| Lack of Fit | 0.9237 | 10 | 0.0924 | 2.66 | 0.1463 | not significant |

| Pure Error | 0.1739 | 5 | 0.0348 | |||

| Cor Total | 69.56 | 29 |

| Std. Dev. | 0.2705 | R² | 0.9842 |

| Mean | 4.15 | Adjusted R² | 0.9695 |

| C.V. % | 6.51 | Predicted R² | 0.9199 |

| Adeq Precision | 29.2152 |

| Run | Variables | Responses | ||||

| Sucrose (%) | Time (h) | Temperature (°C) |

Inoculum (%) | EPS (g/L) | Biomass (g/L) | |

| EPS | 38.105 | 73.426 | 26.944 | 14.986 | 124.01 | - |

| Biomass | 37.910 | 73.223 | 26.839 | 15.001 | - | 6.33 |

| EPS+Biomass | 38.016 | 72.996 | 26.870 | 15.015 | 122.10 | 6.27 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).