1. Introduction

The pervasive use of petrochemical-based plastics has resulted in significant environmental challenges, primarily due to their non-biodegradable nature and substantial carbon dioxide emissions throughout their lifecycle. While these synthetic polymers are cost-effective and widely utilized, their environmental impact, including pollution and harm to wildlife, is profound. The rising costs of petroleum and the associated environmental consequences underscore the urgent need for innovative research focused on developing biodegradable polymers that can effectively replace traditional plastics [

1,

2]. Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) emerges as a promising alternative, being a naturally occurring microbial polyester synthesized by various bacteria and archaea using sustainable resources. PHB is fully biodegradable, breaking down into carbon dioxide, water, and inorganic compounds, which makes it an environmentally friendly option with properties comparable to conventional plastics. Its versatility allows it to be used as a direct substitute for traditional plastics or blended with other polymers to create eco-friendly materials.[

3]. However, the high production costs associated with PHB, especially when compared to petrochemical-based plastics, have been a major barrier to its widespread adoption. A key factor in these costs is the choice of carbon substrate, which plays a crucial role in the efficiency of microbial proliferation and PHB synthesis. Selecting a renewable, economically viable, and readily available carbon source is essential for reducing production costs and enhancing the economic feasibility of PHB [

4,

5]. This study focuses on optimizing PHB production by identifying and evaluating bacterial strains capable of efficient synthesis using agricultural residues as a cost-effective carbon source. By exploring the use of these residues, the research aims to improve the economic sustainability of bioplastic production, while also assessing the environmental benefits of PHB as a sustainable alternative to traditional plastics. The outcomes of this study are expected to contribute to the advancement of biopolymer production, supporting the development of sustainable materials and reducing the environmental impact of petrochemical plastics.

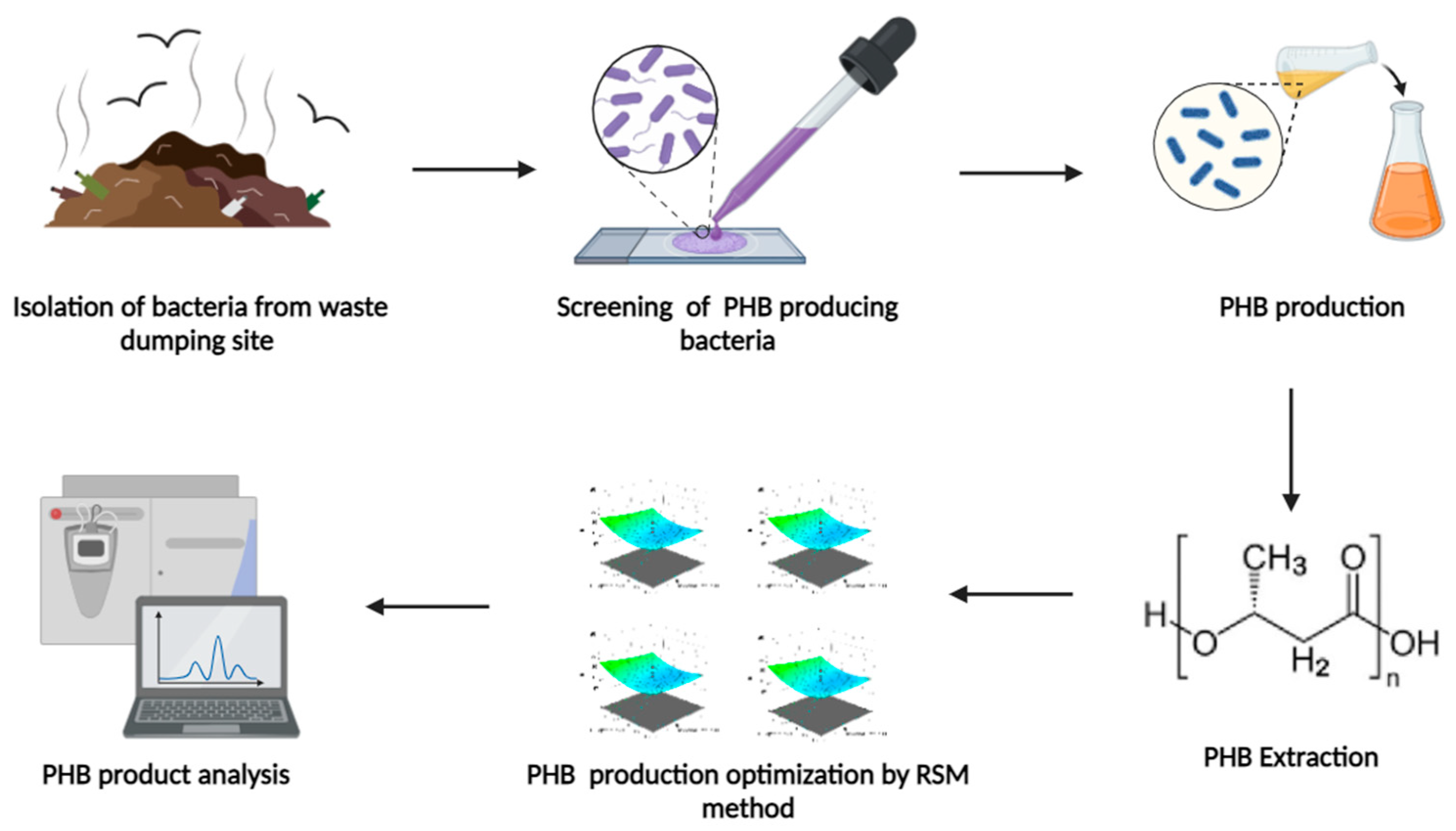

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the work.

Figure 1.

Graphical representation of the work.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Sample Collection and Isolation of Bacteria

A total of 15 soil samples were randomly collected from municipal solid waste Landfill site (latitude 22.980784, longitude 72.566046), Pirana, Ahmedabad, Gujarat, India. The samples were processed aseptically to the laboratory to isolate PHB producing bacteria. The soil samples were air dried for 1-2 days at room temperature. The dried soil samples were crushed and mixed thoroughly to make fine powder. Serial dilution was performed, and the isolation of bacterial isolates was carried out on Nutrient agar. The bacterial isolates were preserved in slants at 4°C till further characterization. [

6]

2.2. Screening of PHB-Producing Bacterial Strain

The Sudan Black-B staining method was used to screen the bacterial isolates[

7]. The detection of PHB-producing bacteria was accomplished by the colony staining method, which was then examined under a microscope. Only eleven of the thirty-five bacterial isolates were able to accumulate PHB granules. Following the secondary screening results, further investigations were conducted through tertiary screenings utilizing culture smeared slides stained with Sudan Black B. Slide observations were conducted using a basic ocular microscope following the methodology described by [

8].

2.3. Molecular Identification of PHB Producing Bacteria by 16S rRNA Gene Analysis

A series of morphological, physiological, and biochemical assays were performed on the PHB-producing bacterial isolates, and their identification was carried out to the genus level following the criteria outlined in Bergey’s Manual of Determinative Bacteriology[

9]. Molecular identification of PHB producing isolates was carried out by 16SrDNA analysis. For 16SrDNA analysis, the genomic DNA of the bacterial isolate was extracted using a bacterial genomic DNA isolation kit (HipurA Bacterial genomic DNA Purification kit Himedia). The DNA samples were electrophoresed on a 0.8% agarose gel, and their quantity and quality were assessed using a UV-1800 Shimadzu Spectrophotometer (Kyoto, Japan) at wavelengths of 260 nm and 280 nm. The 16SrDNA was amplified using universal primers 16s Forward (5′GGATGAGCCCGCGGCCTA3′) and 16s Reverse (5′CGGTGTGTACAAGGCCCGG3′) in the final volume of 50 μL, containing, 10 μL 10X Taq DNA polymerase Assay Buffer, 1 μL Taq DNA Polymerase Enzyme (3U/ ml), 4 μL dNTPs (2.5mM each), 2 μL of each primer, 1 μL of genomic DNA template, and nuclease-free water to make up the volume10. The conditions for PCR amplification were as follows: 940C 3min, 30 cycles of 940C for 1 min, 500C for 1 min and 720C for 2 min, and final extension at 720C for 7 min. The PCR amplified product was detected on agarose gel (1%) and finally imaged by gel documentation system from Bio-Rad® (Hercules, CA, USA). The analysis of the sequence was performed with the help of BDTv3-KB-Denovo_v 5.2 [

10]. The sequence similarity analysis was performed with the help BLAST sequence analysis tool available at the NCBI (National Centre for Biotechnology Information,

www.ncbi.nml.nih.gov). The sequence was finally analysed by Seq Scape_ v 5.2 [

11], . A comparison of partial 16S rDNA sequences was performed against the National Centre for Biotechnology Information's (NCBI) collection of 16S rDNA sequences in public databases.

2.4. Production of PHB

PHB production by the selected isolates was carried out using Mineral Salts Medium (MSM) consisting of Urea (1.0 g/L), Yeast extract (0.16 g/L), KH2PO4 (1.52 g/L), Na2HPO4 (4.0 g/L), MgSO4∙7H2O (0.52 g/L), CaCl2 (0.02 g/L), Glucose (40 g/L), and a trace element solution (0.1 mL). The trace element solution contained ZnSO2∙7H2O (0.13 g/L), FeSO4∙7H2O (0.02 g/L) and H3BO3 (0.06 g/L). Glucose and the trace element solution were autoclaved separately and then mixed before inoculation. The bacterial culture was prepared by subculturing the isolates in nutrient broth. Subsequently, 1 mL of a 24-hour-old culture was transferred into 100 mL of the production medium, followed by incubation at 37°C with agitation at 150 rpm for 48 hours. [

1].

2.5. Extraction and Purification of PHB

The culture broth was centrifuged at 5000 × g for 15 minutes to separate the supernatant from the pellets. The supernatant was removed, leaving behind the pellets, which were subsequently dried. To initiate cell lysis, the dried pellets were treated with 10 mL of sodium hypochlorite solution and incubated at 50 ℃ for 2 hours. Subsequently, the mixture underwent another round of centrifugation at 5000 × g for 15 minutes. After centrifugation, the supernatant was discarded, and the pellets were washed successively with distilled water, acetone, and methanol. Finally, the pellets were dissolved in 5 mL of boiling chloroform. Non-PHB cell matter was separated from the samples using Whatman No. 1 filter paper through filtration. Upon chloroform evaporation, the resulting PHB was preserved for further analysis.[

12]

2.6. Dry Cell Weight (DCW) Analysis

The bacterial dry cell biomass was obtained through the centrifugation of a 10ml culture sample. This centrifugation process was carried out at 8000rpm for 10 minutes. After centrifugation, the pellet of cells was washed twice with distilled water and subsequently dried in a hot air oven at 70°C until it reached a consistent weight. [

13]

2.7. Quantitative Analysis of PHB:

The above mentioned methods were used to grow the culture and calculate the dry weight of cells in g/ l and extraction of intracellular PHB produced by the isolates. To estimate the PHB, the percentage composition of PHB in dry cells was taken into account [

14]. The PHB accumulation (%) was calculated using the formula:

2.8. Characterization of PHB

Multiple techniques, such as Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy, proton nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy (

1H NMR), and ultraviolet-visible (UV-Vis) spectroscopy, were applied to characterize the extracted PHB. The extracted PHB was dissolved in chloroform and determined with a UV-Vis Spectrophotometer between 200 and 320 nm. The IRSpirit SHIMADZU IR was used to record the FTIR spectra in the 400–4000 cm–1 wave range. A concentration of 25 mg/mL was obtained by dissolving 3 mg of retrieved PHB in 1 mL of deuterated chloroform (CCl3) for use in Proton Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (NMReady 100/ nanalysis-oc30) [

15]. At a temperature of 30 °C, the

1H-NMR spectra were acquired at 500 MHz on a Bruker AVANCE 500 Spectrometer. [

16]

2.9. Effect of Culture Conditions on Cell Growth

Single-factor tests were conducted to evaluate the effects of various parameters on PHB accumulation (%) and dry cell weight production. The parameters tested included inoculum age, inoculum size, incubation time, agitation rate, incubation temperature, pH of the medium, as well as different carbon and nitrogen sources. Particularly, the carbon sources employed were lactose, maltose, mannitol, sucrose, fructose, and glucose. Peptone, beef extract, yeast extract, casein hydrolysate, urea, and Tryptone were among the sources of nitrogen [

17].

2.10. Optimization of PHB Production by Response Surface Methodology

In pursuit of enhancing polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) production, the identification of key variables was pivotal. The rationale for employing response surface methodology (RSM) lies in its effectiveness in optimizing complex processes where multiple variables interact. RSM is particularly suitable for this study due to its ability to provide a comprehensive understanding of the interactions between variables and to determine optimal conditions for maximum PHB production.

Subsequently, a response surface central composite design was employed to elucidate the interplay among these variables and to optimize PHB production [

18]. Given the logistical constraints of RSM with a large sample size, investigations were restricted to three variables. Specifically, the influence of wheat bran, corn flour, and peptone was scrutinized across varying concentrations while holding all other parameters constant.

According to the design framework, the total number of treatment combinations is determined by the formula 2ᵏ + 2k + n₀, where 'k' denotes the number of independent variables and 'n₀' signifies the repetition of experiments at the central point. Each variable was explored at five distinct levels (-α, -1, 0, +1, +α), as delineated in

Table 1.

This experimental design employs a two-level fractional factorial approach, including points at -1 and +1, a central point at 0, and axial or star points denoted as -α and +α. All variables were standardized to a central coded value of zero. The range of each variable was determined based on insights gleaned from our previous experimental endeavors. The comprehensive experimental plan, detailing the values both in their actual and coded forms, is cataloged in

Table 2.

Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) production was meticulously assessed in triplicate across 20 distinct experimental iterations. Subsequently, the PHB production data were subjected to analysis employing a second-order polynomial equation, with model fitting facilitated through a multiple regression procedure. The model equation, elucidating the factors influencing PHB production, is delineated as follows:

Here, βo, βi, βii and βij represent the constant, linear, quadratic effects of Xi, and the interaction effect between Xi and Xj respectively, in relation to PHB production.

Following model formulation, a validation experiment was conducted wherein the optimal values for variables predicted by response optimization were applied to ascertain the maximum production of PHB. For software and data analysis, both the Plackett-Burman experimental design and the central composite design were executed utilizing the statistical software Design-Expert 12.0 (Stat-Ease Inc., USA). The influence of individual variables on PHB production was discerned through meticulous analysis of the results within the same software environment [

19]. The selection of RSM was driven by its robustness in modeling and analyzing the influence of multiple variables on PHB production, facilitating a detailed understanding of variable interactions and identification of optimal conditions, thereby maximizing information gained while minimizing the number of experiments.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Isolation and Screening of PHB-Producing Bacteria:

The study led to the discovery of 35 unique bacterial isolates in the soil samples. These isolates underwent an initial screening using the Sudan black B strain to detect PHB presence [

20], and it was found that 11 isolates were capable of storing PHB granules. Among these, GS1 isolate demonstrated notably high PHB production, leading to its selection for further thorough analysis and assessment.

3.2. Identification of High-PHB-Producing Bacterial Isolate:

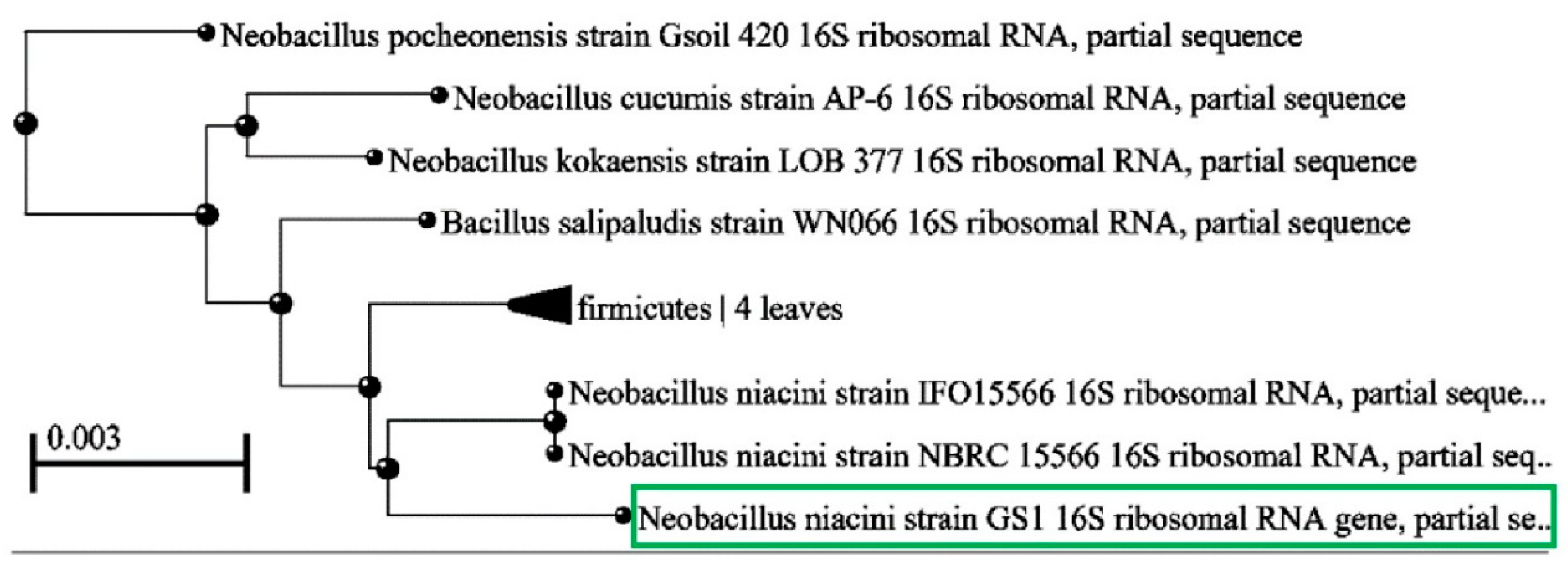

To identify isolate GS1, its genomic DNA was extracted and utilized for PCR amplification of the 16S rRNA gene. [

21]. The subsequent sequencing revealed a close match

with Neobacillus niacinii. The gene sequence obtained from isolate GS1 was submitted to GenBank and assigned the accession number OK668152. Phylogenetic trees were constructed for the GS1 isolate and other

Bacillus species using the neighbor-joining method with MEGA software. The phylogenetic study indicated that isolate GS1 grouped with other

Neobacillus species, verifying its classification as

Neobacillus niacinii GS1.

Figure 2.

Neighbor-joining tree, based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, showing the position of GS-1 and closely related species of Neobacillus.

Figure 2.

Neighbor-joining tree, based on 16S rRNA gene sequences, showing the position of GS-1 and closely related species of Neobacillus.

3.3. Characterization of PHB

The polymer extracted from the

Neobacillus niacinii GS1 strain underwent thorough analysis utilizing UV–Vis spectrophotometry and FTIR spectroscopy. UV–Vis spectroscopy is widely employed for the detection of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) in environmental samples. The examination of the isolated PHB through UV–Vis spectroscopy revealed a symmetrical absorption spectrum, facilitating the identification of distinct functional groups inherent to PHB. This unequivocally confirmed the presence of PHB within the extracted polymer, as evidenced by UV–Vis spectroscopy. [

15]

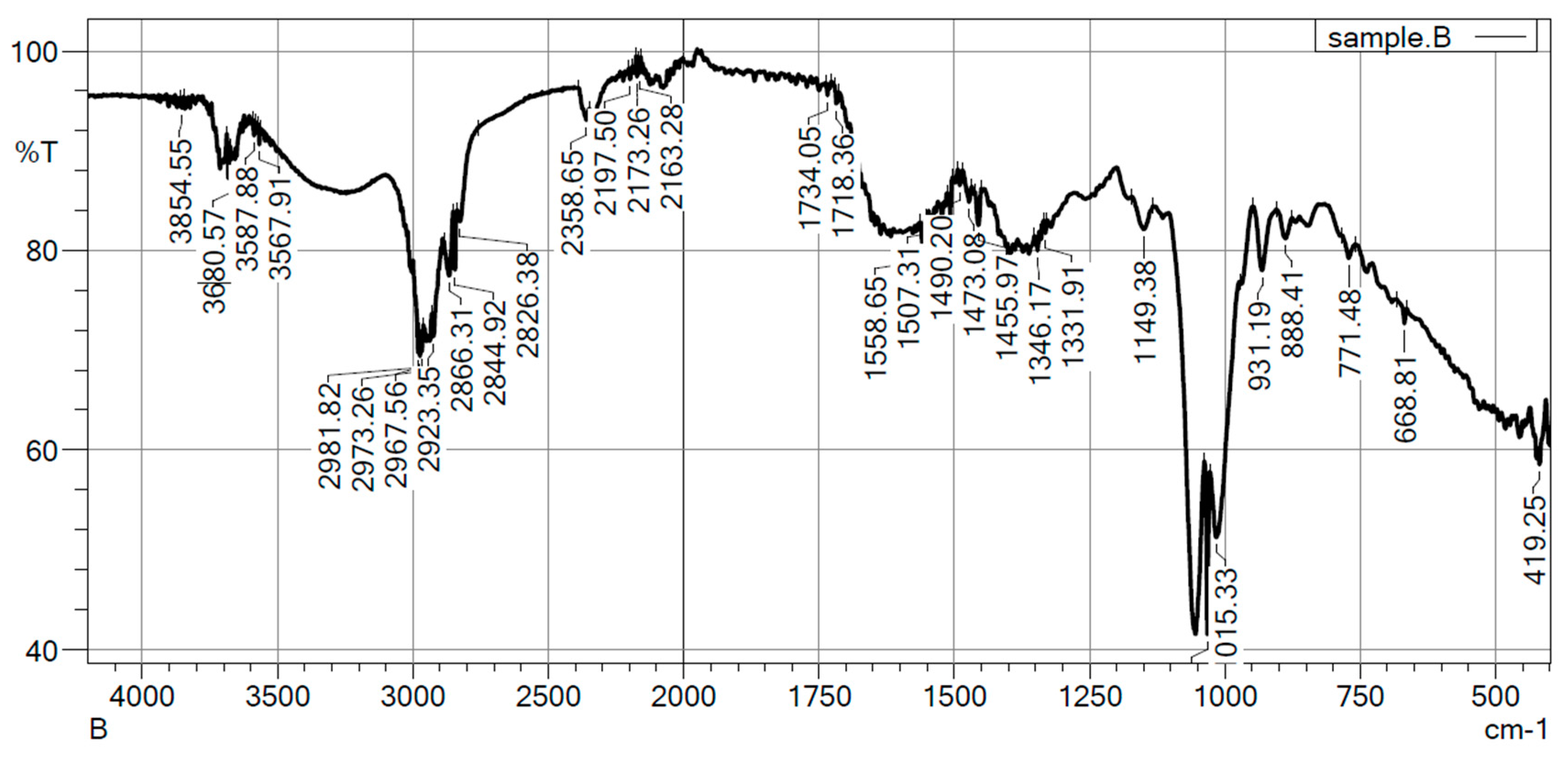

3.3.1. Spectrophotometric and FTIR Analysis

The FTIR spectrum of polymer extracted from the

Neobacillus niacinii GS1 reveals characteristic peaks corresponding to functional groups expected in PHB, including carbonyl (C=O) stretching vibrations at 1718.36 cm⁻¹ and 1734.05 cm⁻¹, indicating the presence of ester groups in the polymer backbone [

20]. Peaks at 2826.38 cm⁻¹ and in the range of 2844.92 cm⁻¹ to 2973.26 cm⁻¹ are associated with the stretching vibrations of methyl (CH₃) and methylene (CH₂) groups, consistent with the PHB structure. The presence of peaks at 3567.91 cm⁻¹ suggests terminal hydroxyl (OH) groups in the PHB chains. Overall, these results confirm the presence of characteristic functional groups in PHB, validating its identity and structural composition.

Figure 3.

FTIR analysis of the extracted PHB from Neobacillus niacinii GS1.

Figure 3.

FTIR analysis of the extracted PHB from Neobacillus niacinii GS1.

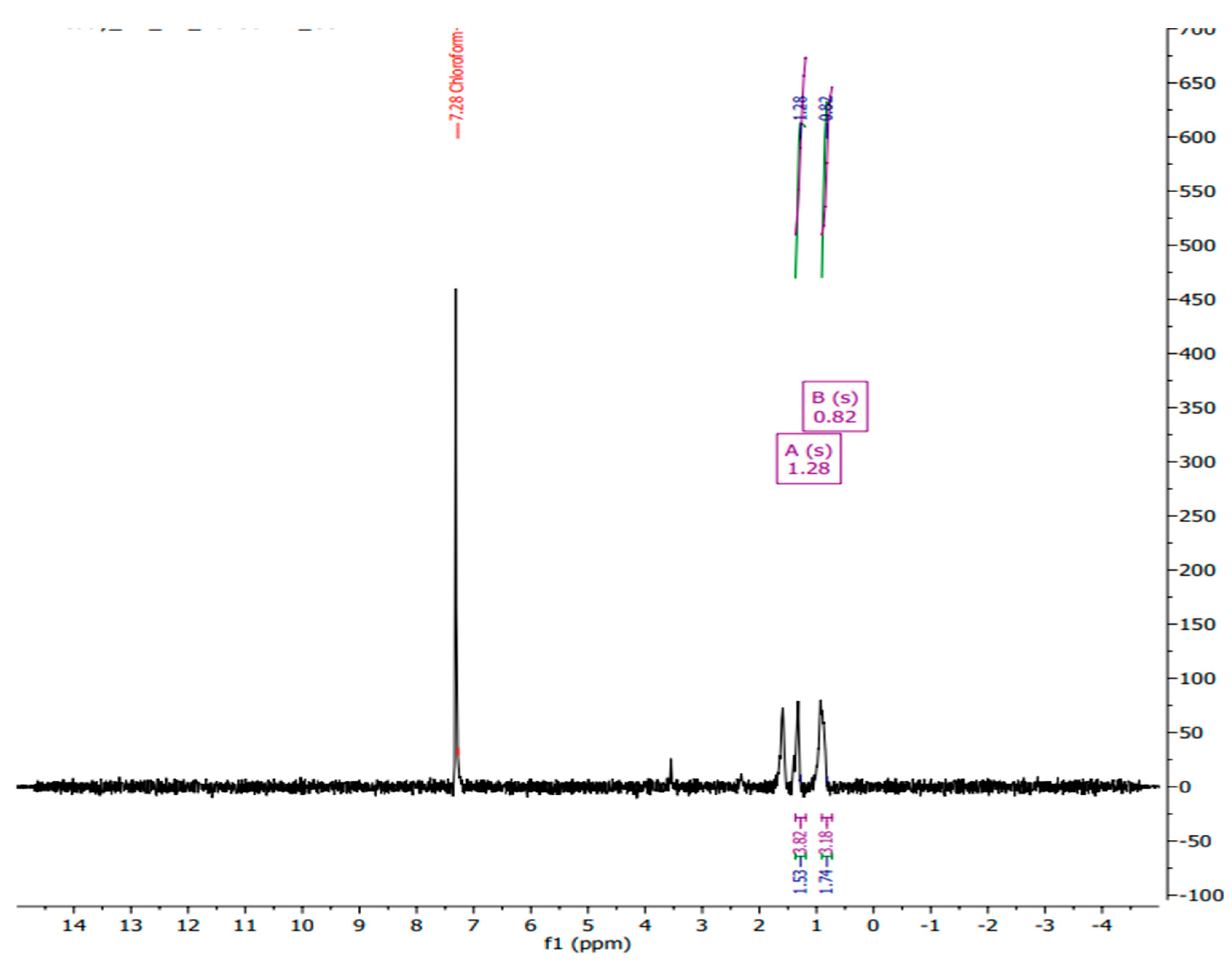

The

1H NMR spectrum of polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) in chloroform-d exhibits key peaks at δ 0.82 ppm, δ 1.28 ppm, and δ 7.28 ppm, the latter corresponding to the residual solvent peak of chloroform-d. The singlet at δ 0.82 ppm is attributed to the methyl group (–CH₃) at the terminal end of the polymer chain, indicative of the protons in an aliphatic chain's terminal methyl group. The singlet at δ 1.28 ppm corresponds to the methylene protons (–CH₂–) adjacent to the ester linkage in the PHB backbone [

22]. This chemical shift results from the deshielding effect of the nearby electronegative oxygen atom in the ester group. The peak at δ 7.28 ppm, representing the residual chloroform-d solvent, serves as an internal standard for chemical shift calibration, although it does not provide structural information about PHB. These chemical shifts are consistent with literature values for PHB, where the methyl protons typically appear around δ 0.8-1.0 ppm and the methylene protons near δ 1.2-1.3 ppm.

3.3.2. NMR Analysis

The presence of these characteristic peaks confirms the identity and purity of the PHB sample. The 1H NMR spectrum aligns with the expected structure of polyhydroxybutyrate, with the observed chemical shifts for the methyl and methylene groups supporting the successful characterization of PHB. Additionally, the clear and distinct peaks indicate the absence of significant impurities. This analysis provides essential information for the structural validation and purity assessment of PHB, which is crucial for its application in various biomedical and biodegradable materials.

Figure 4.

NMR analysis of the extracted PHB from Neobacillus niacinii GS1.

Figure 4.

NMR analysis of the extracted PHB from Neobacillus niacinii GS1.

3.4. Optimization of PHB Production

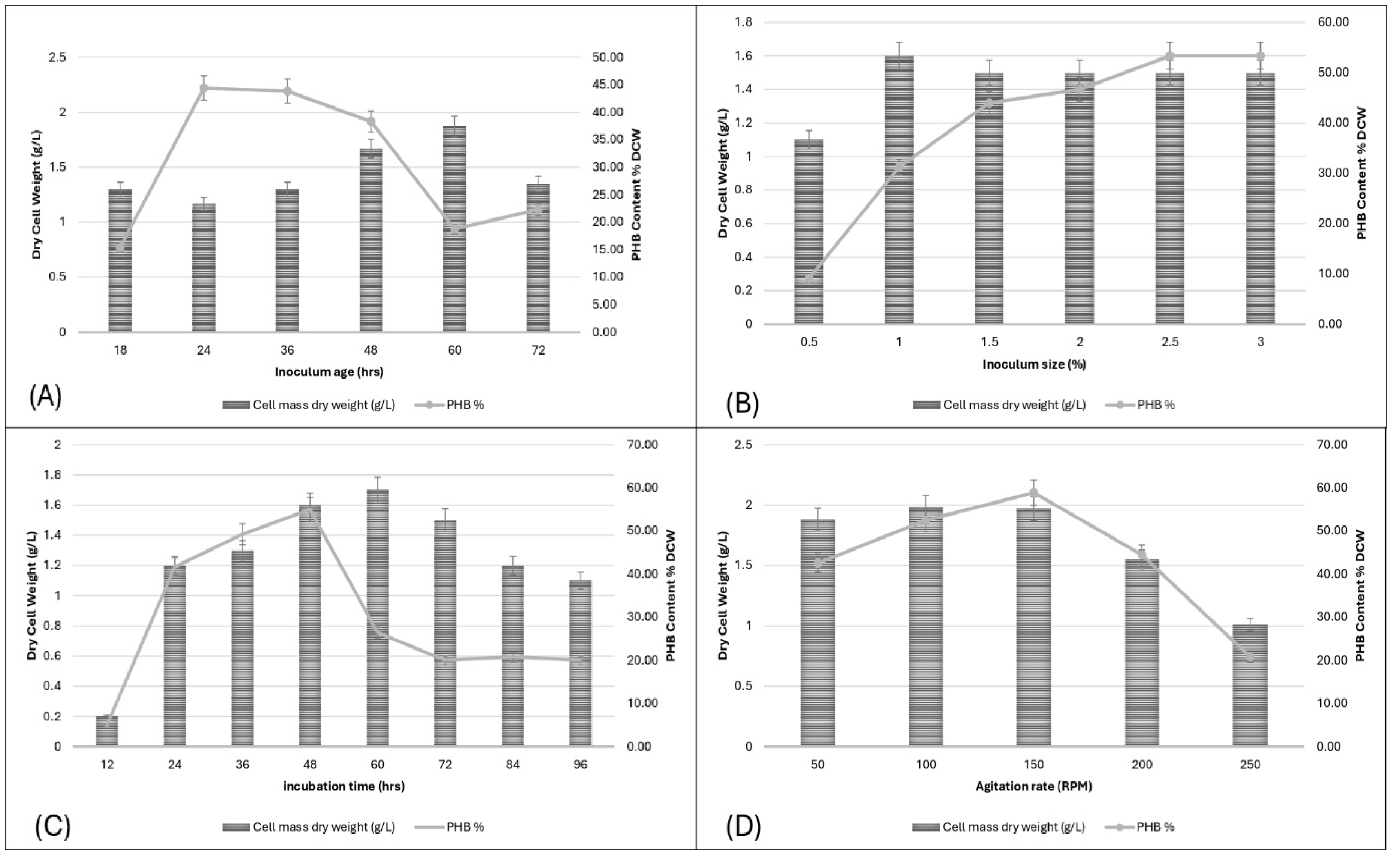

3.4.1. Effect of Inoculum Age on PHB Production

The effect of inoculum age on PHB production and dry cell weight (DCW) was investigated at 18, 24, 36, 48, 60, and 72 hours. The highest DCW, approximately 2.2 g/L, and maximum PHB content, about 45% of DCW, were observed at 48 hours. This suggests that an inoculum age of 48 hours is optimal for both cell mass and PHB accumulation. After 48 hours, both DCW and PHB content declined, indicating the importance of optimizing inoculum age for efficient PHB production. These findings align with [

23] ,who reported that inoculum concentration significantly affects PHB production, achieving up to 8.31 g/L of PHB per liter of inoculum under optimized conditions.

3.4.2. Effect of Inoculum Size on PHB Production

Inoculum sizes of 0.5%, 1%, 1.5%, 2%, 2.5%, and 3% were tested for their effect on PHB production. The maximum DCW was approximately 1.6 g/L at 1.5% inoculum size, while the highest PHB content, around 55% of DCW, was observed at 3%. These results indicate that larger inoculum sizes enhance PHB production, with optimal results at higher inoculum sizes. Studies have shown that an optimal inoculum size is critical for maximizing PHB production. For instance,

Bacillus safensis produced the highest PHB content with an inoculum size of 10 ml/100 ml of fermentation medium [

24]. Similarly,

Lysinibacillus sp. achieved maximum PHB accumulation with an inoculum concentration of 2.5% v/v[

25].

3.4.3. Effect of Incubation Time on PHB Production

The influence of incubation time on PHB production was studied at intervals of 12, 24, 36, 48, 60, 72, 84, and 96 hours. The DCW peaked at approximately 1.7 g/L at 48 hours, with the highest PHB content of about 60%. Beyond 48 hours, both parameters declined, highlighting that 48 hours is optimal for PHB production. Shorter incubation periods, like 48 to 72 hours, can lead to significant PHB production, as seen in other studies. For instance,

Bacillus cereus produced about 50% PHB per dry weight after 48 hours [

26] . Similarly,

Alcaligenes faecalis showed maximum PHB accumulation after 72 hours. [

27].

3.4.4. Effect of Agitation Rate on PHB Production

Agitation rates of 50, 100, 150, 200, and 250 rpm were evaluated. The optimal rate was 150 rpm, yielding a DCW of 1.97 g/L and the highest PHB content of 58.88%. Lower or higher agitation rates reduced both cell mass and PHB content, indicating that moderate agitation rates (100-150 rpm) are favorable for both cell growth and PHB production. Specific agitation speeds are optimal for maximizing PHB production. For example, Bacillus flexus Azu-A2 produced the highest PHB yield at an agitation rate of 100 rpm [

28].

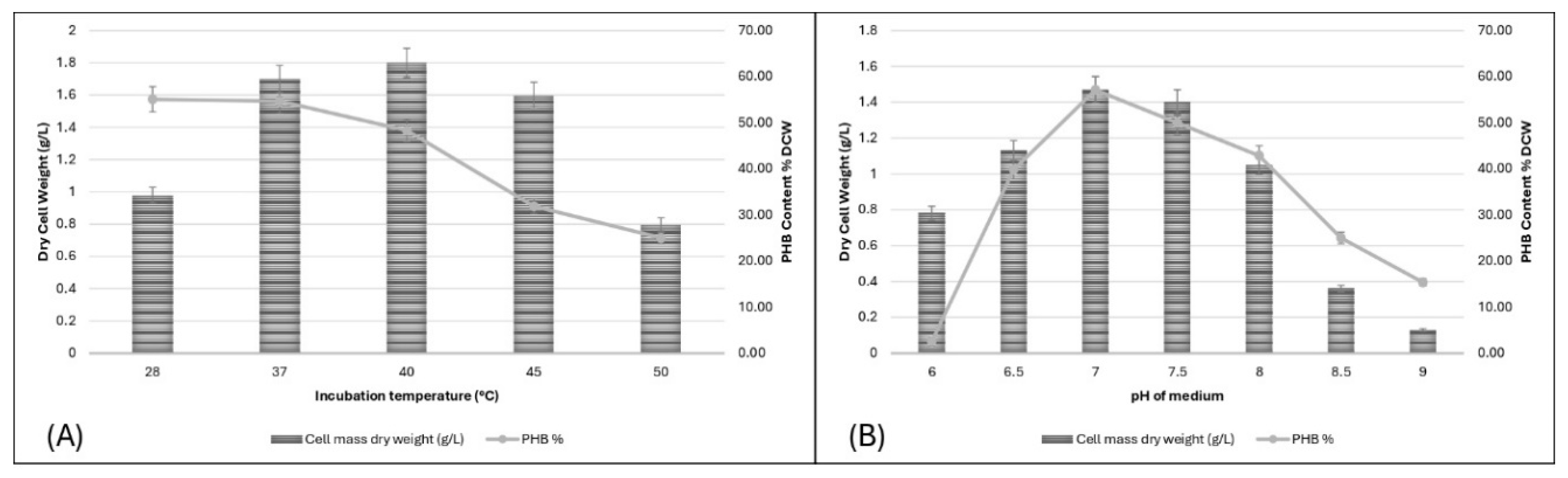

3.4.5. Effect of Incubation Temperature on PHB Production

Temperatures of 28°C, 37°C, 40°C, 45°C, and 50°C were tested. Optimal growth and PHB production were observed at 37°C, with a DCW of 1.7 g/L and PHB content of 54.71%. Temperatures above 40°C significantly reduced both parameters, indicating that lower temperatures are preferable for PHB production. Research indicates that PHB production can occur over a range of temperatures, but the yield significantly drops outside the optimal range. For instance,

Halolamina species produced the highest PHB yield at 37°C[

29].

3.4.6. Effect of pH of Media on PHB Production

The effect of medium pH on PHB production was studied at pH levels of 6, 6.5, 7, 7.5, 8, 8.5, and 9. The highest DCW (1.47 g/L) and PHB content (57.14%) were observed at pH 7. Both parameters declined at higher and lower pH levels, indicating that pH 7 is optimal for PHB production. These findings are consistent with [

6], who reported similar results with

Bacillus flexus achieving peak PHB production at pH 7.0.

Figure 5.

(A) Effect of inoculum age on PHB production, (B) Effect of inoculum size on PHB production, (C) Effect of incubation time on PHB production, (D) Effect of agitation rate on PHB production.

Figure 5.

(A) Effect of inoculum age on PHB production, (B) Effect of inoculum size on PHB production, (C) Effect of incubation time on PHB production, (D) Effect of agitation rate on PHB production.

Figure 6.

(A) Effect of incubation temperature on PHB production, (B) Effect of pH on PHB production.

Figure 6.

(A) Effect of incubation temperature on PHB production, (B) Effect of pH on PHB production.

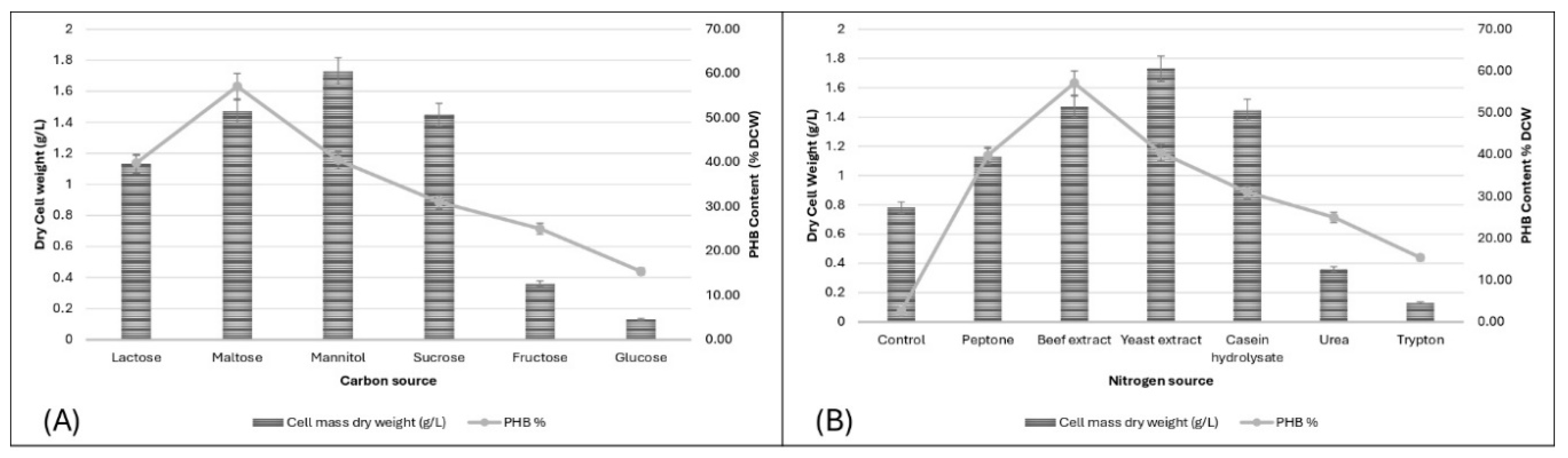

3.4.7. Effect of Different Carbon Source on PHB Production

Different carbon sources (lactose, maltose, mannitol, sucrose, fructose, and glucose) were tested. Maltose supported the highest DCW (1.47 g/L) and PHB content (57.14%). Mannitol also showed high cell growth (1.73 g/L) and PHB content (40.46%). Fructose and glucose were less effective, highlighting maltose and mannitol as the most suitable carbon sources. Similar observations have been noted in other bacterial strains such as

Cupriavidus necator and

Halolamina spp., which demonstrate robust PHB production capabilities when cultivated on sugars like glucose and fructose [

29] Understanding the differential utilization of carbon sources is crucial for optimizing PHB production strategies, particularly in industrial applications aiming to enhance biopolymer synthesis efficiency and yield.

3.4.8. Effect of Different Nitrogen Source on PHB Production

Various nitrogen sources (control, peptone, beef extract, yeast extract, casein hydrolysate, urea, and tryptone) were evaluated. Beef extract supported the highest DCW (1.47 g/L) and PHB content (57.14%). Yeast extract also showed significant support with a DCW of 1.73 g/L and PHB content of 40.46%. Other nitrogen sources varied in effectiveness, with beef extract and yeast extract being the most optimal. Similar trends have been observed in

Bacillus sp., where yeast extract enhances PHB synthesis significantly.[

30].

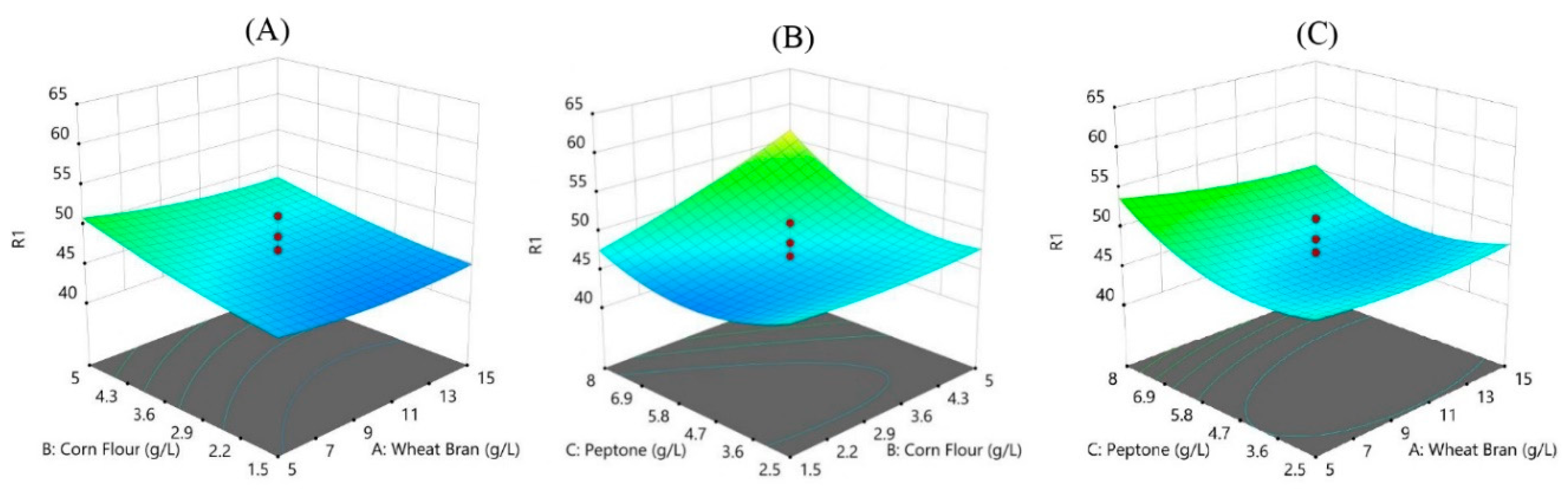

3.4.9. PHB Production Optimization by RSM

The results indicate significant variation in PHB production based on different combinations of the three variables. The highest PHB production observed was 61.1% in Run 14, with the variable levels set at 10% wheat bran, 3.25% corn flour, and 9.87% peptone. The central composite design and response surface methodology effectively optimized PHB production, revealing significant interactions between the variables. The validation experiment confirmed the model's accuracy, with the optimal conditions achieving high PHB yields. Wheat bran's role as a carbon source significantly influenced PHB production. Previous studies have indicated the effectiveness of lignocellulosic biomass in enhancing PHB yield due to its high carbohydrate content[

31]. Corn flour, another carbohydrate-rich substrate, also demonstrated a positive effect on PHB production. The interplay between corn flour and wheat bran was crucial for optimizing the nutrient balance required for bacterial growth and PHB biosynthesis [

32]. Peptone, a source of nitrogen, was essential for microbial metabolism and PHB production. Its optimal concentration ensured sufficient protein synthesis and enzyme activity, which are critical for PHB biosynthesis [

33]. The interaction effects between wheat bran, corn flour, and peptone were evident from the experimental results. The highest PHB yield was achieved when all three components were optimized simultaneously, highlighting the importance of a balanced nutrient environment for maximizing PHB production.

Figure 7.

(A) Effect of different carbon sources on PHB production, (B) Effect of different nitrogen sources on PHB production.

Figure 7.

(A) Effect of different carbon sources on PHB production, (B) Effect of different nitrogen sources on PHB production.

Figure 8.

Combine effect of low cost agriculture waste (A) corn flour +wheat bran (B) peptone +wheat bran (C) peptone + corn flour on PHB production by Neobacillus niacinii GS1.

Figure 8.

Combine effect of low cost agriculture waste (A) corn flour +wheat bran (B) peptone +wheat bran (C) peptone + corn flour on PHB production by Neobacillus niacinii GS1.

This study, while comprehensive, has several limitations. The focus on only three substrates—wheat bran, corn flour, and peptone—may overlook other potential factors that could influence PHB production. Additionally, the use of response surface methodology (RSM) with a restricted sample size might limit the generalizability of the findings to larger-scale production scenarios. The experimental conditions were controlled, which might not fully replicate real-world industrial environments. Future research should explore a broader range of variables, including other carbon and nitrogen sources, and environmental factors such as aeration and moisture levels. Investigating the scalability of the optimized conditions in a pilot or industrial-scale setup would also be valuable. Furthermore, integrating genomic and proteomic analyses could provide deeper insights into the metabolic pathways involved in PHB production, potentially leading to further optimization and enhancement of bacterial strains.

5. Conclusions

This study successfully optimized polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) production using Neobacillus niacinii GS1, focusing on three key variables: wheat bran, corn flour, and peptone. The use of response surface methodology (RSM) facilitated the identification of optimal conditions, resulting in a significant enhancement of PHB yield. The highest PHB production was achieved under conditions of 10% wheat bran, 3.25% corn flour, and 9.87% peptone, demonstrating the feasibility of utilizing agricultural residues as cost-effective substrates. The implications of these findings are substantial for the field of sustainable bioplastic production. By efficiently converting agro-industrial residual into valuable biopolymers, this study underscores the potential of Neobacillus niacinii GS1 in industrial applications, offering a viable alternative to traditional petrochemical plastics. This not only addresses environmental concerns associated with plastic pollution but also provides a sustainable approach to waste valorization. For future research, it is recommended to explore a wider array of variables, including additional carbon and nitrogen sources, and environmental factors such as aeration and moisture levels. Investigating the scalability of the optimized conditions in pilot or industrial-scale setups would further validate the practical applicability of the findings. Additionally, integrating genomic and proteomic analyses could yield deeper insights into the metabolic pathways involved in PHB production, potentially leading to further optimization and enhancement of bacterial strains.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Shrimali Gaurav, Gangawane Ajit; methodology, Shrimali Gaurav; software, Shah Hardik; validation, Gangawane Ajit, Jens Ejbye Schmidt; formal analysis, Shah Hardik; investigation, Shrimali Gaurav, Thumar Kashyap; resources, Gangawane Ajit; data curation, Shrimali Gaurav; writing—original draft preparation, Shrimali Gaurav; writing—review and editing, Rami Esha, Deepak Sahoo, Ashish Patel, Jens Ejbye Schmidt; visualization, Shrimali Gaurav; supervision, Gangawane Ajit; project administration, Shrimali Gaurav, Jens Ejbye Schmidt; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this article will be made available by the authors on request.

Acknowledgments

This study was conducted at Parul Institute of Applied Science and Research, Parul University and School of Applied Sciences and Technology, Gujarat Technological University. We gratefully acknowledge both Universities for their generous support and provision of essential resources that enabled the successful completion of this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Getachew, A.; Woldesenbet, F. Production of Biodegradable Plastic by Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) Accumulating Bacteria Using Low Cost Agricultural Waste Material. BMC Res Notes 2016, 9, 509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumari, D.; Jaipuriar, D.S.; Kanchana, P.; Varma, S.M.; Gurja, S. BIODEGRADABLE PLASTIC (PHB) FROM BACTERIA COLLECTED FROM GOPALPUR BEACH, BHUBANESWAR. Int J Curr Pharm Sci 2020, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acharjee, S.A.; Bharali, P.; Gogoi, B.; Sorhie, V.; Walling, B. ; Alemtoshi PHA-Based Bioplastic: A Potential Alternative to Address Microplastic Pollution. Water Air Soil Pollut 2023, 234, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, M.A.M.; Serafim, L.S.; Lemos, P.C.; Ramos, A.M.; Aguiar, F.R.; Van Loosdrecht, M.C.M. Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoates by Mixed Microbial Cultures. Bioprocess Biosyst Eng 2003, 25, 377–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurieff, N.; Lant, P. Comparative Life Cycle Assessment and Financial Analysis of Mixed Culture Polyhydroxyalkanoate Production. Bioresource Technology 2007, 98, 3393–3403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Ashraf, S.A.; Snoussi, M.; Badraoui, R.; Ibrahim, A.M.M.; Alreshidi, M.; Sachidanandan, M.; Patel, M. Characterization and Process Optimization for Enhanced Production of Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB)-Based Biodegradable Polymer from Bacillus Flexus Isolated from Municipal Solid Waste Landfill Site. Polymers 2023, 15, 1407. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, Y.S.; Alrumman, S.A.; Otaif, K.A.; Alamri, S.A.; Mostafa, M.S.; Sahlabji, T. Production and Characterization of Bioplastic by Polyhydroxybutyrate Accumulating Erythrobacter Aquimaris Isolated from Mangrove Rhizosphere. Molecules 2020, 25, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alarfaj, A.A.; Arshad, M.; Sholkamy, E.N.; Munusamy, M.A. Extraction and Characterization of Polyhydroxybutyrates (PHB) from Bacillus thuringiensisKSADL127 Isolated from Mangrove Environments of Saudi Arabia. Braz. arch. biol. technol. 2015, 58, 781–788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brenner, D.J.; Krieg, N.R.; Staley, J.T. Bergey’s Manual of Systematic Bacteriology: The Alpha-, Beta-, Delta-, and Epsilonproteobacteria; Springer, 2005; ISBN 0-387-24145-0.

- Bruno, W.J.; Socci, N.D.; Halpern, A.L. Weighted Neighbor Joining: A Likelihood-Based Approach to Distance-Based Phylogeny Reconstruction. Molecular biology and evolution 2000, 17, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, W.J.; Socci, N.D.; Halpern, A.L. Weighted Neighbor Joining: A Likelihood-Based Approach to Distance-Based Phylogeny Reconstruction. Molecular Biology and Evolution 2000, 17, 189–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López-Abelairas, M.; García-Torreiro, M.; Lú-Chau, T.; Lema, J.M.; Steinbüchel, A. Comparison of Several Methods for the Separation of Poly(3-Hydroxybutyrate) from Cupriavidus Necator H16 Cultures. Biochemical Engineering Journal 2015, 93, 250–259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, Mohd. ; Kumar, S.; Kumar, S.; Dhiman, A.K. Optimization of Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) Production by Azohydromonas Lata MTCC 2311 by Using Genetic Algorithm Based on Artificial Neural Network and Response Surface Methodology. Biocatalysis and Agricultural Biotechnology 2012, 1, 70–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhuwal, A.K.; Singh, G.; Aggarwal, N.K.; Goyal, V.; Yadav, A. Isolation and Screening of Polyhydroxyalkanoates Producing Bacteria from Pulp, Paper, and Cardboard Industry Wastes. International Journal of Biomaterials 2013, 2013, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adnan, M.; Siddiqui, A.J.; Ashraf, S.A.; Snoussi, M.; Badraoui, R.; Alreshidi, M.; Elasbali, A.M.; Al-Soud, W.A.; Alharethi, S.H.; Sachidanandan, M.; et al. Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB)-Based Biodegradable Polymer from Agromyces Indicus: Enhanced Production, Characterization, and Optimization. Polymers 2022, 14, 3982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, R.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, X.; Yang, J.; Gao, Y.; Zi, X.; Zhang, X.; Gao, H.; Hu, N. Psychrotrophic Pseudomonas Mandelii CBS-1 Produces High Levels of Poly-β-Hydroxybutyrate. SpringerPlus 2013, 2, 335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.J. Study on Nitrogen Removal Characteristics of an Aerobic Denitrifying Bacterium Rhodococcus Strain T7. Environ. Ecol. Three Gorges 2008, 1, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Papaneophytou, C.P.; Kyriakidis, D.A. Optimization of Polyhydroxyalkanoates Production from Thermus Thermophilus HB8 Using Response Surface Methodology. J Polym Environ 2012, 20, 760–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdy, S.M.; Danial, A.W.; Gad El-Rab, S.M.F.; Shoreit, A.A.M.; Hesham, A.E.-L. Production and Optimization of Bioplastic (Polyhydroxybutyrate) from Bacillus Cereus Strain SH-02 Using Response Surface Methodology. BMC Microbiol 2022, 22, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D, A.; V S, P. Extraction and Characterization of Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) From Bacillus Flexus MHO57386.1 Isolated From Marine Sponge Oceanopia Arenosa (Rao, 1941). Marine Science and Technology Bulletin 2021, 10, 170–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petti, C.A.; Polage, C.R.; Schreckenberger, P. The Role of 16S rRNA Gene Sequencing in Identification of Microorganisms Misidentified by Conventional Methods. J Clin Microbiol 2005, 43, 6123–6125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonthrone, K.M.; Clauss, J.; Horowitz, D.M.; Hunter, B.K.; Sanders, J.K.M. The Biological and Physical Chemistry of Polyhydroxyalkanoates as Seen by NMR Spectroscopy. FEMS Microbiology Letters 1992, 103, 269–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silambarasan, S.; Logeswari, P.; Sivaramakrishnan, R.; Pugazhendhi, A.; Kamaraj, B.; Ruiz, A.; Ramadoss, G.; Cornejo, P. Polyhydroxybutyrate Production from Ultrasound-Aided Alkaline Pretreated Finger Millet Straw Using Bacillus Megaterium Strain CAM12. Bioresource Technology 2021, 325, 124632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gomaa, S.; El-Refai, H.; Allam, R.; Shafei, M.; Ahmed, H.; Zaki, R. Statistical Optimization for Polyhydroxybutyrate Production by Locally Isolated Bacillus Safensis Using Sugarcane Molasses under Nutritional Stressed Conditions. Egypt Pharmaceut J 2023, 22, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saratale, R.G.; Cho, S.K.; Saratale, G.D.; Ghodake, G.S.; Bharagava, R.N.; Kim, D.S.; Nair, S.; Shin, H.S. Efficient Bioconversion of Sugarcane Bagasse into Polyhydroxybutyrate (PHB) by Lysinibacillus Sp. and Its Characterization. Bioresource Technology 2021, 324, 124673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elgendy, N.; Aboshanab, K.; Yassien, M.; Aboulwafa, M.; Hassouna, N. Scaling up, Kinetic Modeling, and Economic Analysis of Poly (3-Hydroxybutyrate) Production by Bacillus Cereus Isolate CCASU-P83. Archives of Pharmaceutical Sciences Ain Shams University 2021, 5, 158–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naman Jain; Lily Priyadarshini; Kritika Sharma; Iyappan S; Jaganathan M K; Jai Ganesh R Enhancement of Polymeric Poly-(β)-Hydroxy Butyrate (PHB) Production from Alcaligenes Faecalis through the Optimisation Process. ijrps 2020, 11, 7436–7441. [CrossRef]

- Khattab, A.M.; Esmael, M.E.; Farrag, A.A.; Ibrahim, M.I.A. Structural Assessment of the Bioplastic (Poly-3-Hydroxybutyrate) Produced by Bacillus Flexus Azu-A2 through Cheese Whey Valorization. International Journal of Biological Macromolecules 2021, 190, 319–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagagy, N.; Saddiq, A.A.; Tag, H.M.; Selim, S.; AbdElgawad, H.; Martínez-Espinosa, R.M. Characterization of Polyhydroxybutyrate, PHB, Synthesized by Newly Isolated Haloarchaea Halolamina Spp. Molecules 2022, 27, 7366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Kumar Sharma, M.; Kumar Sharma, M.; Kumar, G. Isolation of Local Strain of Bacillus Sp. SM-11, Producing PHB Using Different Waste Raw as Substrate. RJPT, 2058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cesário, M.T.; Raposo, R.S.; De Almeida, M.C.M.D.; Van Keulen, F.; Ferreira, B.S.; Da Fonseca, M.M.R. Enhanced Bioproduction of Poly-3-Hydroxybutyrate from Wheat Straw Lignocellulosic Hydrolysates. New Biotechnology 2014, 31, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramadas, N.V.; Singh, S.K.; Soccol, C.R.; Pandey, A. Polyhydroxybutyrate Production Using Agro-Industrial Residue as Substrate by Bacillus Sphaericus NCIM 5149. Braz. arch. biol. technol. 2009, 52, 17–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khamplod, T.; Wongsirichot, P.; Winterburn, J. Production of Polyhydroxyalkanoates from Hydrolysed Rapeseed Meal by Haloferax Mediterranei. Bioresource Technology 2023, 386, 129541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoshimura, F.; Suzuki, T. Calcium-Stimulated Adenosine Triphosphatase in the Microsomal Fraction of Tooth Germ from Porcine Fetus. Biochim Biophys Acta 1975, 410, 167–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schlegel, H.G.; Lafferty, R.; Krauss, I. The Isolation of Mutants Not Accumulating Poly-?-Hydroxybutyric Acid. Archiv. Mikrobiol. 1970, 71, 283–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumari, D.; Jaipuriar, D.S.; Kanchana, P.; Varma, S.M.; Gurja, S. BIODEGRADABLE PLASTIC (PHB) FROM BACTERIA COLLECTED FROM GOPALPUR BEACH, BHUBANESWAR. Int J Curr Pharm Sci 2020, 41–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Peterson, D.; Peterson, N.; Stecher, G.; Nei, M.; Kumar, S. MEGA5: Molecular Evolutionary Genetics Analysis Using Maximum Likelihood, Evolutionary Distance, and Maximum Parsimony Methods. Molecular biology and evolution 2011, 28, 2731–2739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiley, E.O.; Brooks, D.R.; Seigel-Causey, D.; Funk, V.A. The Compleat Cladist: A Primer of Phylogenetic Procedures; Natural History Museum, University of Kansas, 1991; ISBN 0-89338-035-0.

- Chern, C.J.; Beutler, E. Biochemical and Electrophoretic Studies of Erythrocyte Pyridoxine Kinase in White and Black Americans. Am J Hum Genet 1976, 28, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, K.S.; Sarma, R.H. Delineation of the Intimate Details of the Backbone Conformation of Pyridine Nucleotide Coenzymes in Aqueous Solution. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1975, 66, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chern, C.J.; Beutler, E. Biochemical and Electrophoretic Studies of Erythrocyte Pyridoxine Kinase in White and Black Americans. Am J Hum Genet 1976, 28, 9–17. [Google Scholar]

- Bose, K.S.; Sarma, R.H. Delineation of the Intimate Details of the Backbone Conformation of Pyridine Nucleotide Coenzymes in Aqueous Solution. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 1975, 66, 1173–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mostafa, Y.S.; Alrumman, S.A.; Alamri, S.A.; Otaif, K.A.; Mostafa, M.S.; Alfaify, A.M. Bioplastic (Poly-3-Hydroxybutyrate) Production by the Marine Bacterium Pseudodonghicola Xiamenensis through Date Syrup Valorization and Structural Assessment of the Biopolymer. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 8815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).