This section presents the results of the social life cycle inventory (S-LCI) and social life cycle im-pact assessment (S-LCIA) phases to describe the magnitude and significance of the environmental impacts of the F-CUBED Production System applied to the target biogenic residue streams, i.e., pulp and paper bio-sludge (PPB), virgin olive pomace (OP), and fruit and vegetable residue stream—orange peel (ORP). Positive indications show a stress on the environment, whilst negative indicators show positive impacts.

3.1. Social Life Cycle Inventory (S-LCI) Results

In the present section, the social life cycle inventory phase (S-LCI) for the F-CUBED Production System is described for the target biogenic residue streams. The LCI refers to the SHDB model that was developed based on the existing environmental LCA [

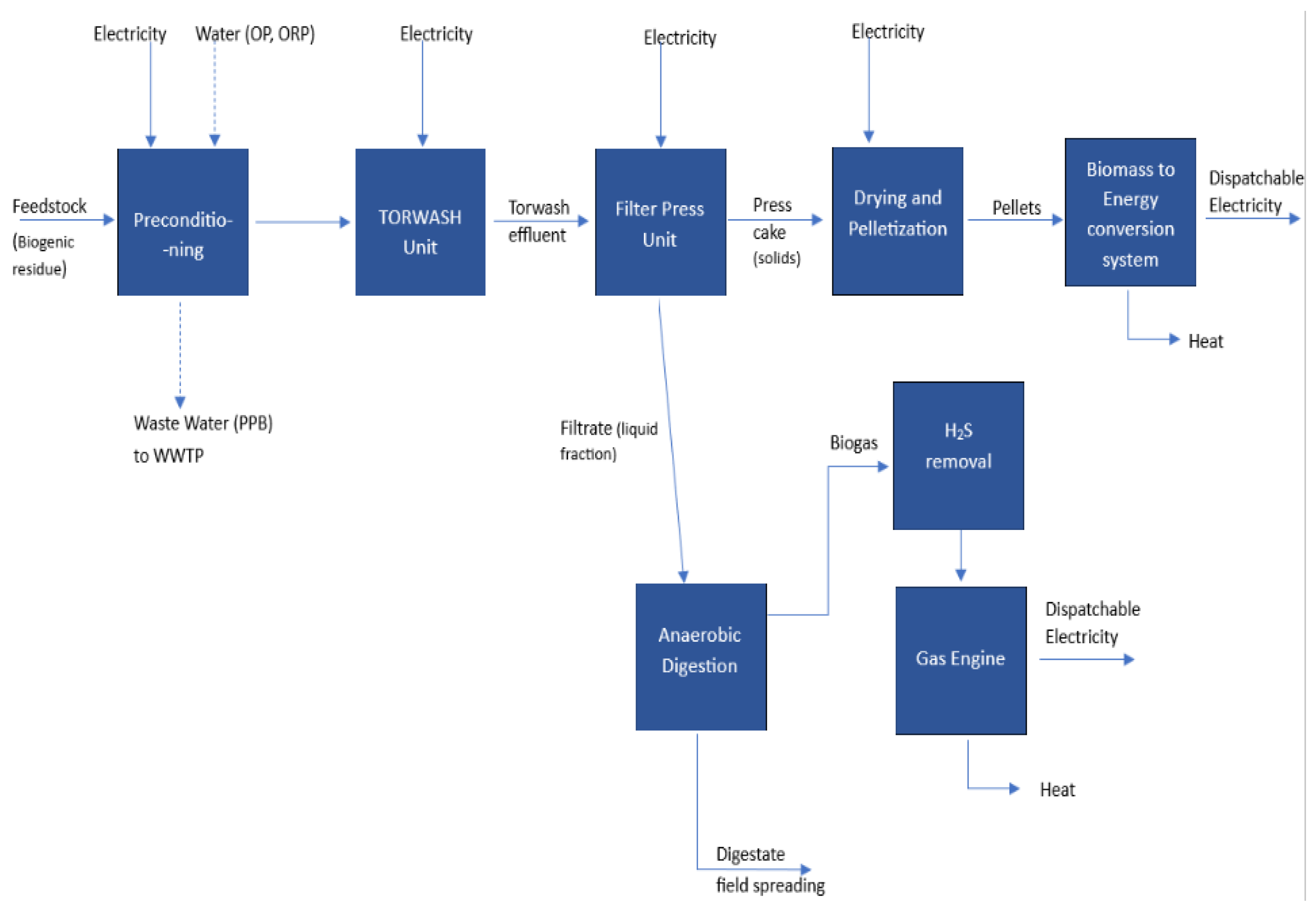

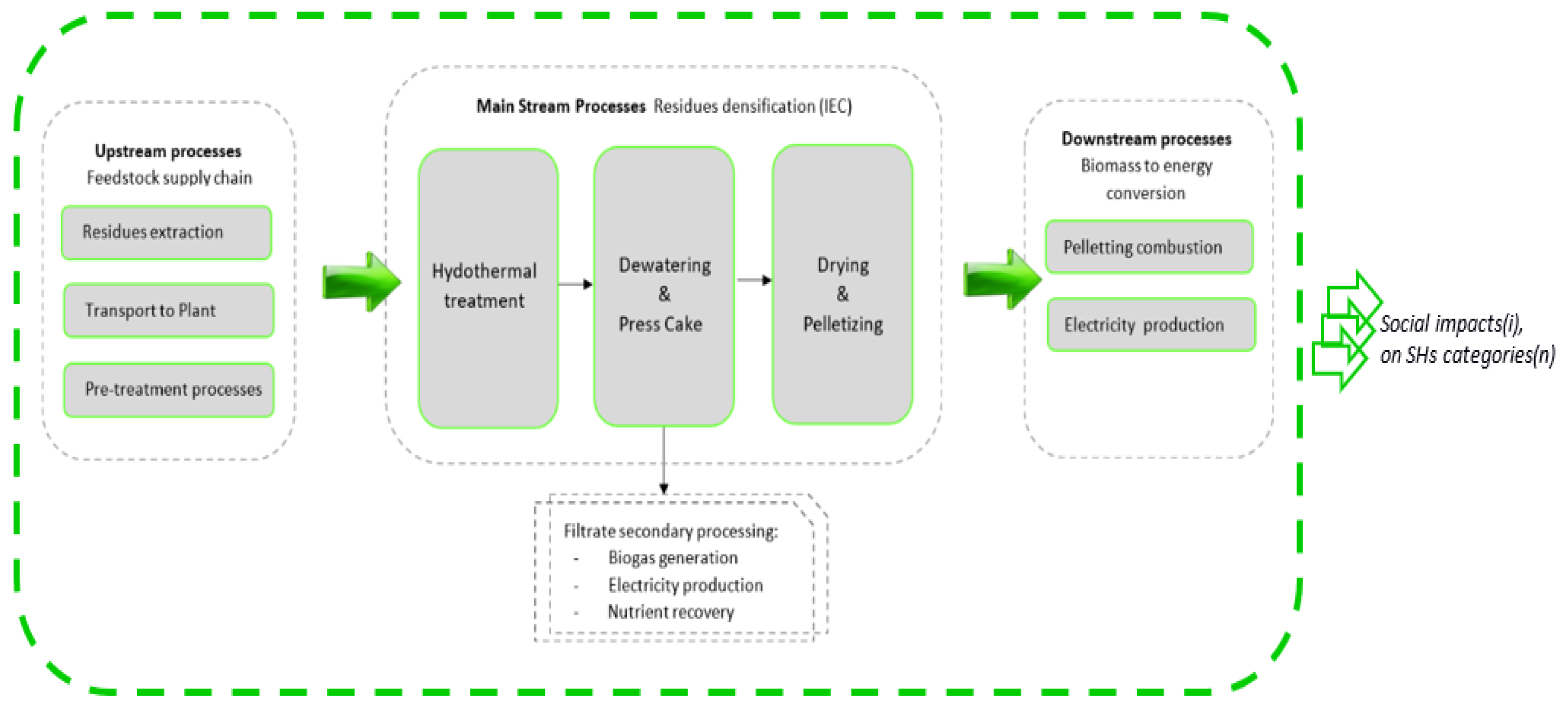

22] by identifying the unit processes representative of the F-CUBED Production System, using the most relevant country-specific sectors (CSS) available in SHDB. The F-CUBED Production System is designed to exclude upstream stages such as the biomass field production and the associated logistics of transporting biomass to industrial facilities where residues are generated. Instead, the system boundary commences at the point of residue extraction and comprises: (i) residue pre-treatment; (ii) hydrothermal treatment and mechanical dewatering via the TORWASH® process; (iii) solid fraction conditioning and palletisation; and (iv) generation of dispatchable end-products—namely Biopellets, thermal energy, and/or electricity—delivered to final users.

The Social Life Cycle Inventory (S-LCI) phase for the above-mentioned processes within the F-CUBED Production System is delineated in

Table 3. The objective of the S-LCI exercise is to quantify, for each of the three case studies under investigation, the economic value (in constant 2011 USD) of inputs sourced from relevant Country-Specific Sectors (CSS) within SHDB that are required to produce the F-CUBED outputs.

Several unit processes included in the Social Life Cycle Inventory (S-LCI) phase were modelled using Social Hotspot (SH) processes derived from the Social Hotspots Database (SHDB). These SH processes were selected based on the country-specific context (i.e., Sweden, Italy, or Spain) and the type of biogenic residue stream involved—namely pulp and paper bio-sludge, olive pomace, or orange peels.

In line with the Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products and Organizations, an SH process is defined as a unit process or life cycle stage characterized by a high potential for social or environmental impact, significantly contributing to one or more impact subcategories.

The inclusion of SH processes serves to strengthen the inventory phase by addressing data gaps, such as the unavailability of specific indicators or their respective weightings, and by improving the completeness and representativeness of the social life cycle dataset. This approach ensures alignment with data quality requirements related to coverage, consistency, and transparency, which are critical for comparative or consequential S-LCA applications.

The corresponding social LCI datasets applied in the three case studies are detailed in

Table 4. For every case study, the assessment builds upon primary data sourced from the Environmental Life Cycle Assessment (E-LCA), which served as the foundation for developing the S-LCA model. Specifically, the E-LCA provided detailed information on the composition of the supply chain, enabling the identification of all relevant stages of the F-CUBED Production System required to generate electricity from the wet biogenic residue stream of pulp and paper bio-sludge, olive pomace residues and orange residues. The pulp and paper biosludge case study is geographically contextualized in Sweden, reflecting the location of the industrial partner participating in the Torwash pilot testing—specifically, Smurfit Kappa. The economic sectors selected for this assessment correspond to key activities in the system, including paper manufacturing, machinery and equipment, wood pellet production, and electricity generation. The case study of olive pomace is geographically situated in Italy, at the Frantoio Oleario Chimienti, a facility affiliated with the APPO farmers’ association, located in Bari, in the Apulia Region. The economic sectors refer to the specific industrial sector of the vegetable oil production in Italy, machinery and equipment, wood pellets and electricity generation. Finally, the case study of orange peels is geographically situated in Spain, in the Delafruit facility, located in La Selva del Camp, Tarragona. The economic sectors refer to the specific industrial sector of the industrial sector of the vegetables, fruits, nuts growing in Spain, machinery and equipment, wood pellets and electricity generation.

The complete data collection for the S-LCI phase of each case study is presented in

Table 5, along with a detailed description of the underlying assumptions. These elements collectively provide a comprehensive overview of the inventory modeling approach applied to this case study.

The unit processes defined as outputs of the production system were derived from the Life Cycle Inventory (LCI) of the Environmental Life Cycle Assessment (E-LCA), as previously described. Conversely, the input unit processes required for modeling the upstream supply chain were identified from secondary data sources, as detailed in

Table 6. All economic values used in the S-LCI are expressed in constant 2011 U.S. dollars (USD 2011). For currency conversion, an exchange rate of 1.33 EUR/USD—corresponding to the rate in January 2011—was applied.

In the case of pulp and paper bio-sludge, conventional disposal via landfilling—within defined environmental safety parameters—has been considered the baseline reference scenario. Accordingly, an avoided cost was introduced to reflect the economic benefit associated with diverting the residue from landfill. In the Olive Pomace case study, the economic value attributed to the residue generated by the two-phase olive oil extraction process—which produces wet pomace—was based on the authors’ expertise and reflects typical market values observed in Italy. The economic value assigned to the residue generated from orange processing—specifically during orange juice production—was based on the market value of orange peels used as feed in Ecuador. Nevertheless, it is important to note that the reference supply chain for residue extraction is situated nationally, with operations occurring in Spain.

The economic value attributed to the solid fraction produced through the TORWASH® hydrothermal treatment and subsequent dewatering was based on the market value of wood chips, selected as a substitutable good due to its functional equivalence in energy applications. Similarly, the economic value of Biopellets, manufactured from the F-CUBED solid fraction, was estimated using the market price of wood pellets as the surrogate reference.

For the sake of clarity and transparency,

Table 6 presents an overview of the production and unit processes included in the assessment, along with their corresponding economic sectors and data sources used to obtain prices or surrogate values. Where primary data were not available, surrogate values were employed to estimate input costs. The surrogate value represents the monetary value of a substitute good or service that delivers a comparable level of utility to the end-user or performs an equivalent function within the production system. This methodological approach follows the definition proposed by [

31], ensuring consistency in the representation of economic flows across the social inventory.

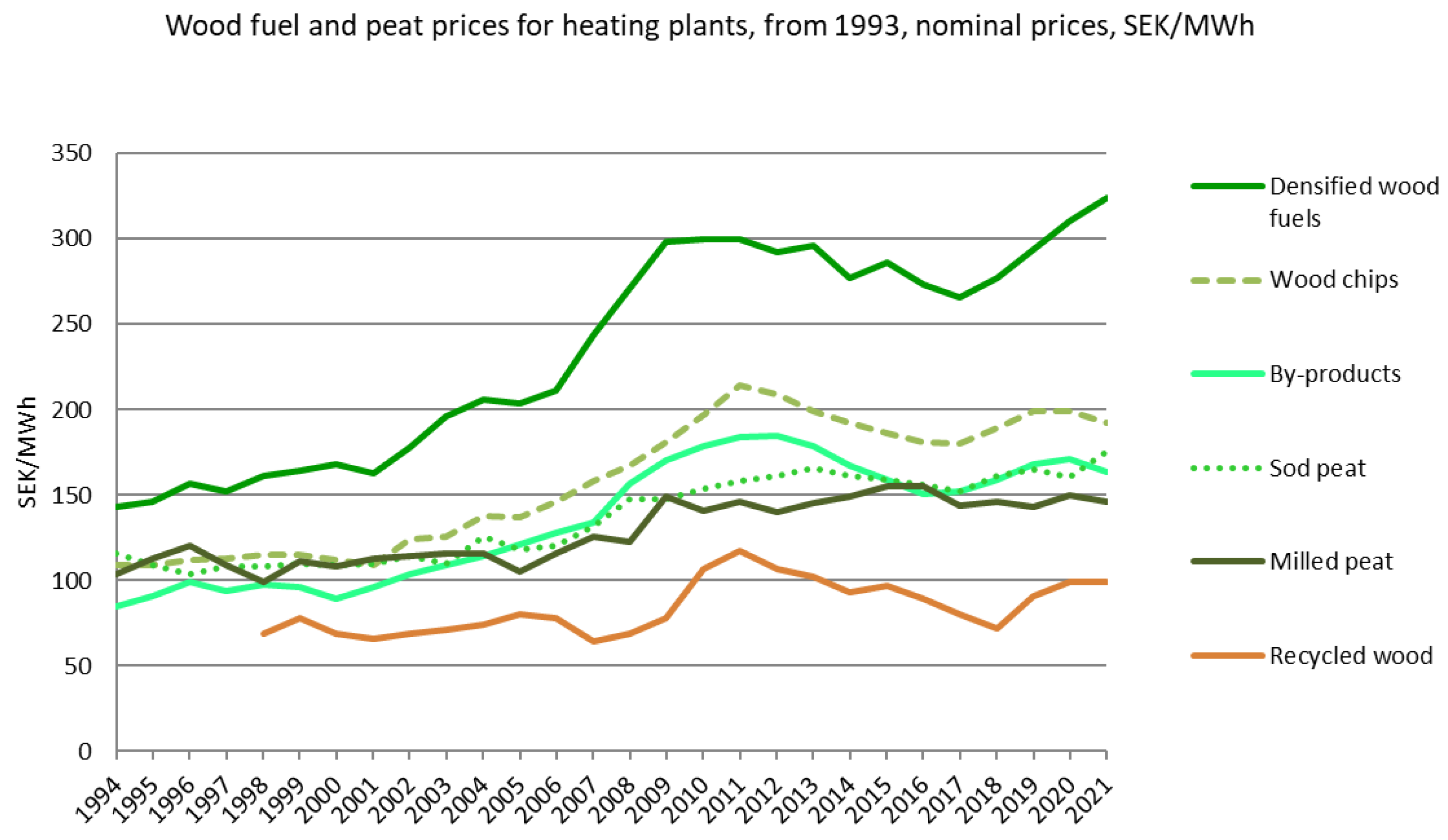

The prices of wood chips and densified wood fuels were sourced from official energy statistics published by the Swedish Energy Agency, based on national energy balances presented in Sweden Facts and

Figures 2022 [

33]. The reported prices for 2021 are 192 SEK/MWhₜₕ for wood chips and 324 SEK/MWhₜₕ for wood pellets, as also illustrated in

Figure 3.

To convert these values into euros per ton (€/t), the following lower heating values (LHVs) were applied: 2.91 MWh/t for wood chips and 5.12 MWh/t for wood pellets. An exchange rate of 0.084 €/SEK was used to complete the conversion.

3.2. Results of the Survey on Socio-Economic Aspects

To assess the potential social impacts of the F-CUBED Production System at the local level, a targeted stakeholder survey was designed and implemented as part of the Life Cycle Inventory. This activity aimed to explore how the introduction of the novel production system might influence key dimensions such as quality of life, working conditions, and broader socio-economic well-being across different stakeholder groups. Drawing from established research in socio-economics and survey methodology [

28,

39,

40], the approach was grounded in best practices to mitigate informational bias and ensure robust, comparable data. In line with the UNEP Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment [

13], the survey focused on a defined set of social performance indicators, known as impact subcategories, enabling benchmarking against other biomass conversion technologies. The method of engagement was adapted to meet the varying needs and expectations of stakeholders, using a combination of tools—including online questionnaires, phone interviews, and video calls—applied flexibly and iteratively throughout the data collection process. The socio-economic assessment survey aimed to explore stakeholder perspectives on the potential social impacts of implementing the F-CUBED Production System across the three case studies’ countries: Italy, Spain, and Sweden. The survey targeted 44 stakeholders, selected for their relevance to the project and geographical diversity, and was administered between June and early August 2023, with multiple follow-up waves to encourage participation. In the end, 19 responses were collected, corresponding to a 43% response rate. This figure was considered statistically acceptable given the specificity and complexity of the subject matter. Stakeholder representation was spread across several European countries, with a majority from Italy, followed by respondents from the Netherlands, Ireland, Spain, Germany, and Sweden.

The survey results show a generally positive reception toward the F-CUBED Production System, especially concerning economic development, employment opportunities, and sustainability alignment. However, less attention was given to ethical and deep social dimensions, highlighting a possible area for future communication and stakeholder engagement. The survey aimed to determine which categories of stakeholders might be most affected by the new production system. According to the UNEP 2020 Guidelines [

13], six stakeholder groups were considered: Value Chain Actors, Local Community, Workers, Society, Consumers, and Children. The survey results revealed that the Value Chain Actors were perceived as the most significantly impacted, followed closely by the Local Community and Workers. Children, on the other hand, were ranked much lower, largely due to the limited direct relevance of the F-CUBED system to this group. Some respondents even noted concerns over potential health risks in this category, highlighting a future area that might warrant closer investigation. When examining the Value Chain Actors category, the focus was largely on economic implications. Survey participants emphasized the importance of technological advancement, new market opportunities, and the economic viability of the technology. Employment perspectives were also considered relevant. However, ethical and social concerns such as fair competition and broader social responsibility were given less importance, suggesting a predominant focus on practical economic outcomes.

In contrast, the Local Community category received a more balanced evaluation, with both economic and social dimensions considered important. Economic opportunity and the availability of local resources were ranked highly, alongside environmental factors such as air and water quality, and the potential for local job creation. Notably, even respondents from environmental NGOs reported no significant concerns regarding environmental impacts, which suggests a broadly favourable perception of the system’s integration into local settings.

The Workers category, although ranked third overall, attracted considerable attention due to the direct impacts anticipated on work conditions, career prospects, and job satisfaction. Training needs were also acknowledged. Yet, aspects such as equal opportunity and long-term job stability were not highlighted as major concerns. This result may suggest a generally favourable expectation of the new system’s integration into existing employment structures, or a lack of perceived risk among workers.

The Society category revealed an optimistic view of the system’s contribution to broader sustainability goals. Many participants recognized the F-CUBED system as aligned with policy and societal interests, and potentially valuable in addressing future social challenges. Despite this, explicitly ethical concerns such as societal values were less frequently cited, indicating a possible gap between technological promise and its perceived ability to influence ethical behaviour or broader cultural shifts.

Although the Consumers category was not highly ranked, yet the responses pointed to high expectations in terms of service quality. Reliability of bioenergy products and the affordability of energy emerged as important concerns, along with accessibility and perceived benefits of the new technology. This suggests that, although consumers may not be the primary focus of the system’s implementation, their expectations remain critical to its perceived success.

3.3. Social Life Cycle Impact Assessment (S-LCIA) Results

This section illustrates the results provided by the S-LCIA based on two main methodological adjustments: 1) harmonization between the impact categories of SHDB database and UNEP 2020 Guidelines; 2) selection of the Social Hotspots Database (SHDB) subcategories that are most representative and relevant for the F-CUBED Production System.

The Social Hotspots Database (SHDB) impact assessment methodology organizes social performance indicators into five principal impact categories: Labor Rights and Decent Work, Health and Safety, Human Rights, Local Community, and Governance. This categorization is broadly consistent with the updated 2020 UNEP Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products and Organizations [

13]. However, it is important to acknowledge key discrepancies due to the Social Hotspots Database's (SHDB) partial alignment with the subcategories recommended in the Guidelines. As a result, harmonization efforts are necessary to ensure a comprehensive and coherent application across assessments [

23].

In the SHDB framework, these five impact categories are derived through the aggregation of 30 distinct subcategories, forming the core of the S-LCIA phase. In contrast, the 2020 UNEP Guidelines propose a broader structure comprising six stakeholder-related impact categories: Human Rights, Working Conditions, Health and Safety, Cultural Heritage, Governance, and Socio-economic Repercussions, subdivided into a total of 40 subcategories.

This structural divergence implies that while SHDB offers a practical and operational framework for early-stage or large-scale social risk screening, it may require supplementary subcategory-level analysis and mapping to fully conform with the UNEP Guidelines in more comprehensive S-LCA studies. Therefore, careful methodological alignment and correspondence mapping are essential when applying SHDB within studies adhering to UNEP’s normative framework.

Table 7 presents the Social Impact Categories assessed during the Social Life Cycle Impact Assessment (S-LCIA) of the F-CUBED Production System, alongside the selected subcategories derived from stakeholder survey outcomes, as detailed in

Section 3.2.

The table also includes a preliminary harmonization map between the subcategories adopted by the Social Hotspots Database (SHDB) and those recommended in the UNEP Guidelines for Social Life Cycle Assessment of Products and Organizations and Methodological Sheets for Subcategories in S-LCA [

13,

41].

To ensure a more comprehensive and context-relevant analysis, two additional subcategories have been incorporated into the original list of the SHDB:

Injuries & Fatalities (2B): this subcategory is critical for assessing occupational health and safety, particularly in relation to labour intensity and exposure to risk factors throughout the value chain. Its inclusion strengthens the representativeness of the Working Conditions impact category;

Democracy & Freedom of Speech (4C): in the current geopolitical context, where energy system resilience is increasingly influenced by global supply dependencies, this subcategory becomes especially relevant. It allows for the assessment of systemic risks associated with countries where severe restrictions on civil liberties, such as freedom of expression and peaceful assembly, may signal broader governance and human rights concerns.

The extended set of subcategories enables a more holistic assessment of social risk and opportunity, aligned with both SHDB's operational structure and UNEP's normative S-LCA framework.

Building upon these methodological foundations, a comprehensive and multi-dimensional data visualization strategy was implemented to effectively communicate the S-LCIA findings. Four key types of visualization were developed: 1) Aggregate Social Impact by Category. This table provides a synthesized overview of the social risks or benefits associated with each harmonized impact category. It integrates risk characterization results across economic sectors and life cycle stages, allowing for high-level comparisons across case studies and facilitating initial prioritization of areas of concern; 2) Disaggregated Impact by Economic Sector. Sector-specific contributions to overall social impact were presented both numerically and through bar charts, detailing the relative weight of each economic activity (e.g., TORWASH® treatment, palletisation, biogas generation) within the supply chain. This visualization is critical for identifying sectoral hotspots and informs targeted intervention strategies; 3) Subcategory Level Analysis. The selected subcategories —mapped from SHDB to the UNEP typology—were examined to understand their distribution across economic sectors. A combined table and figure presentation illustrates both the absolute and relative contributions to social risk, enabling a granular analysis of how specific themes such as “Labor Rights,” “Smallholders vs. Commercial Farms,” or “Access to Material Resources” are influenced by each phase of the production process; 4) Risk Characterization. This table translates numeric impact scores into qualitative performance levels (low, medium, high, very high risk) using SHDB’s ordinal Performance Reference Point (PRP) system. The mapping consolidates category and subcategory level assessments across geographic contexts, supporting the prioritization of social risk mitigation and stakeholder engagement actions.

3.3.1. Aggregate Social Impact by Category

This visualization provides a synthesized overview of the social risks or benefits associated with each harmonized impact category. It integrates risk characterization results across economic sectors and life cycle stages, allowing for high-level comparisons across case studies and facilitating initial prioritization of areas of concern. As detailed in

Table 8, the social footprint of the F-CUBED Production System was assessed by aggregat-ing the social impacts associated with each country-specific sector (CSS), into a consolidated score for each damage category.

In this context, a damage category refers to an "area of protection"—a conceptual construct that represents domains considered to hold intrinsic or societal value (e.g., human well-being, community cohesion, institutional stability) and which are intended to be preserved or enhanced through sustainability-oriented interventions. These categories serve as the final aggregation level in the impact assessment, capturing the potential long-term consequences of social risks across the product system's life cycle.

The scores are expressed in medium risk hours equivalent (mrheq), providing complementary metric to quantify social performance within the S-LCIA framework. The aggregated social impact results for each case study represent the cumulative risk contributions of each economic sector across all life cycle stages of the F-CUBED system. These results offer a high-level synthesis of the social risk landscape, supporting comparative assessments and guiding stakeholder-specific mitigation strategies.

The results from the Social Life Cycle Impact Assessment (S-LCIA) of the F-CUBED Production System applied to three biogenic residue streams—pulp & paper biosludge, olive pomace, and orange peels—reveal a nuanced picture of how social impacts unfold across different European industrial contexts.

The social performance of the F-CUBED system varies widely depending on the socio-economic and institutional context of its implementation. The Swedish case demonstrates stability and modest gains in an already favourable environment; the Italian case reveals considerable potential but is hindered by systemic social risks that require active mitigation; and the Spanish case stands out as a highly successful integration of technology and social sustainability.

In the case of pulp & paper biosludge, treated within the Swedish industrial setting, the F-CUBED Production System demonstrates an overall beneficial social footprint. All five categories register slightly negative mrheq values, meaning the implementation of the technology contributes to a net reduction in social risks. The most significant improvements are observed in the areas of Health and safety and Governance. These results are in line with Sweden’s generally strong institutional frameworks and well-enforced labour standards. The production stages that influence these outcomes the most are the electricity generation phases—both from pellets and biogas—where robust occupational health and safety standards and good labor practices significantly mitigate risks. Furthermore, the Governance category benefits from the high regulatory compliance and low corruption indices characteristic of the Swedish industrial and energy sectors. While the absolute impact values are modest, the consistency of the beneficial signals across all categories affirms the social viability of the F-CUBED system in this context, albeit with a relatively limited scale of benefit due to the already high base-line of social performance in Sweden.

A starkly different situation emerges with olive pomace in the Italian context. Here, the F-CUBED system generates the highest social impact values—positive in sign, and thus indicative of risk—among the three case studies. The most critical areas are Health and safety and Labor rights with Health and safety presenting the most concerning figure. This can be attributed to the relatively higher exposure to occupational hazards in the energy generation phases, as well as the labor-intensive nature of pellet production in small and medium-sized enterprises in southern Italy. The sector’s reliance on seasonal or informal labor, together with disparities in enforcement of workplace safety regulations, contributes to these results. In terms of Governance, the risk reflects persistent concerns over regulatory efficacy, bureaucratic inefficiencies, and localized issues of transparency and accountability. The community category also reveals areas of vulnerability, particularly in relation to access to infrastructure and utilities, although some mitigating effects are observed due to the involvement of smallholders and the promotion of local employment. Overall, the Italian case study portrays a complex scenario where economic opportunities generated by the F-CUBED system—especially in terms of job creation and valorisation of agricultural by-products—coexist with persistent structural challenges that elevate social risk.

In contrast, the Orange Peels case study, centred in Spain, presents an exceptionally positive social profile. All five impact categories display strongly negative mrheq values, signifying substantial social benefits. The standout performance lies in the categories of Health and safety and Labor rights where the introduction of the F-CUBED system appears to markedly reduce social risks. These findings suggest that the Spanish agri-food and renewable energy sectors involved in this case are well-regulated and characterized by relatively safe and stable employment conditions. The positive outcomes also reflect the effective integration of the F-CUBED production chain into the existing industrial ecosystem, which benefits from high levels of automation and technological maturity. Governance is another area where the Spanish case study performs exceptionally well, with strong institutions and adherence to EU labor and environmental norms reinforcing the social sustainability of the system. Community-level benefits are also evident, driven by improved access to services, employment, and a cleaner environmental footprint. The scale of these benefits suggests that the F-CUBED system not only fits seamlessly within the Spanish socio-economic framework but actively enhances it, making this case a model of socially sustainable bioenergy valorisation.

These outcomes reflect effective corporate policies, responsible value chain management, and alignment with international social standards. Particularly Health & Safety impact category presents the most favourable condition, strong performance in ensuring workplace safety, likely with good prevention measures and low accident rates. Governance score also indicates effective governance practices, such as transparency, anti-corruption, and regulatory compliance.

3.3.2. Disaggregated Impact by Economic Sector

This section presents sector-specific contributions to overall social impact. The detailed breakdown of the Social Life Cycle Impacts for each F-CUBED case study—Pulp & Paper biosludge, Olive Pomace, and Orange Peels—across various production phases and impact categories, offers a nuanced picture of how these systems interact with the socio-economic contexts in which they are deployed. These figures, expressed in medium risk hour equivalents (mrheq), capture both risks and benefits, with negative values reflecting social benefits and positive values indicating social risks.

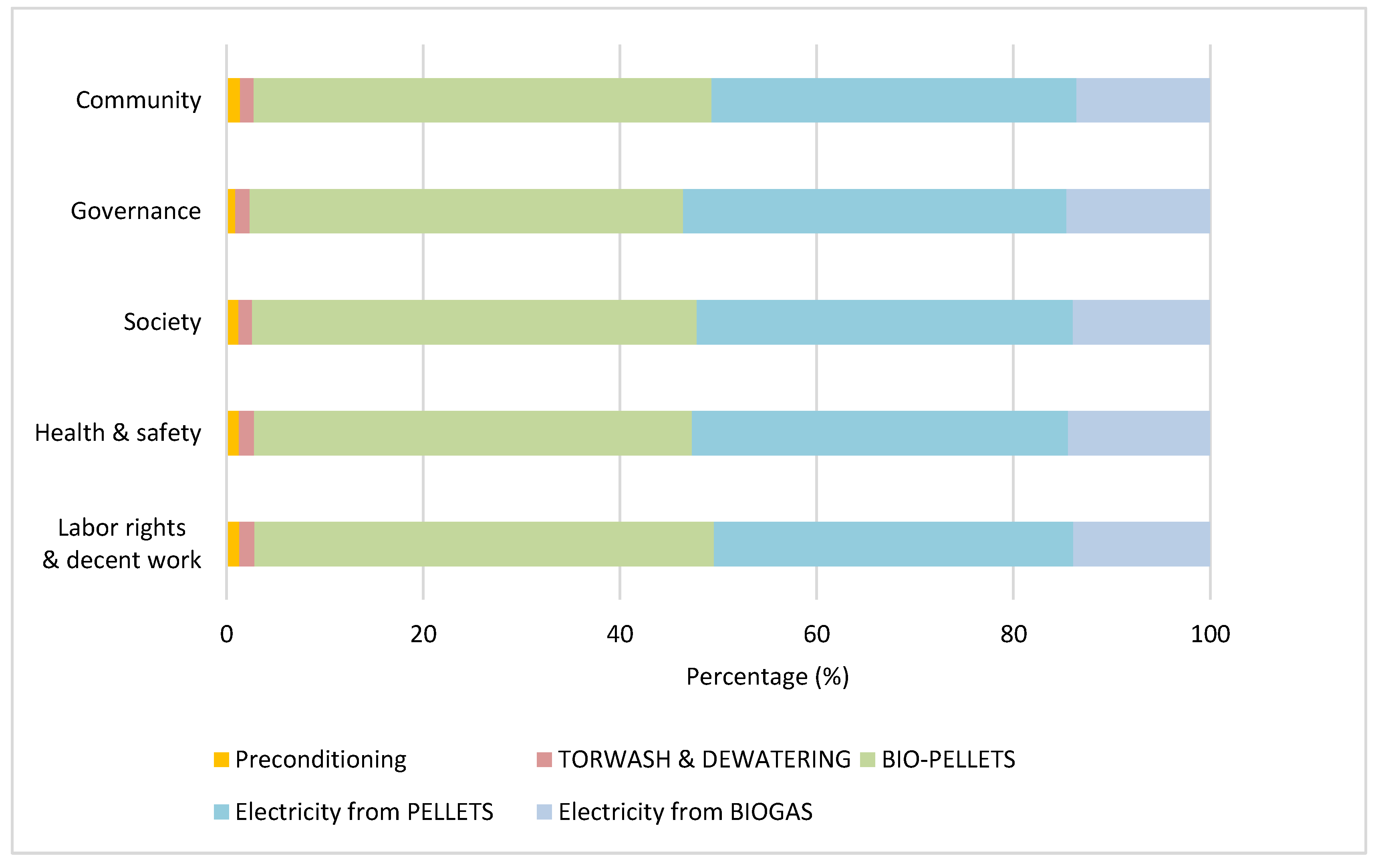

The visualization of social impacts disaggregated by economic sector, as displayed in

Table 9, is critical for identifying sectoral hotspots, enabling the identification of process-specific contributions to overall social risk, and enhancing the interpretive resolution of the assessment and supporting targeted risk mitigation strategies.

Table 9 presents the sector-wise distribution of social impacts for the Pulp & Paper Biosludge, Olive Pomace and Orange Peels case studies. The impacts are reported across five social impact categories —Labor Rights & Decent Work, Health & Safety, Society, Governance, and Community—and are expressed in medium risk hours equivalents (mrheq). Each production phase of the F-CUBED system is linked to its corresponding economic sector, including preconditioning, TORWASH® hydrothermal treatment coupled with dewatering, Biopellets production, and electricity generation from both pellets and biogas.

For the Pulp & Paper Biosludge case study in Sweden, the overall picture is one of modest but consistent social benefit. The most substantial positive contributions stem from the electricity generation phases—particularly electricity from pellets and biogas—which produce significantly negative scores across all five im-pact categories. This suggests that these steps contribute to reducing social risks, likely due to Sweden’s ad-vanced energy infrastructure, strong enforcement of labor and safety standards, and relatively low social tensions around energy production. For instance, the electricity from pellets phase alone exhibits notably beneficial values in Labor rights and Governance, indicating not only job quality and safety but also institutional robustness. The upstream steps, including enhanced biosludge treatment and the Torwash and dewatering phases, show slight positive scores, suggesting minimal risks introduced by these technologies. However, their impact is largely offset by the stronger benefits downstream. The pellet production step introduces minor social risks across the board, possibly reflecting labor intensity or supply chain dependencies that are less socially optimized. Nevertheless, the total aggregated results confirm that the F-CUBED system applied to pulp and paper biosludge offers a socially beneficial pathway, albeit with modest absolute impacts due to the already favourable Swedish context. These results are likely attributable to the strong regulatory framework and high social performance of the electricity generation sector in Sweden.

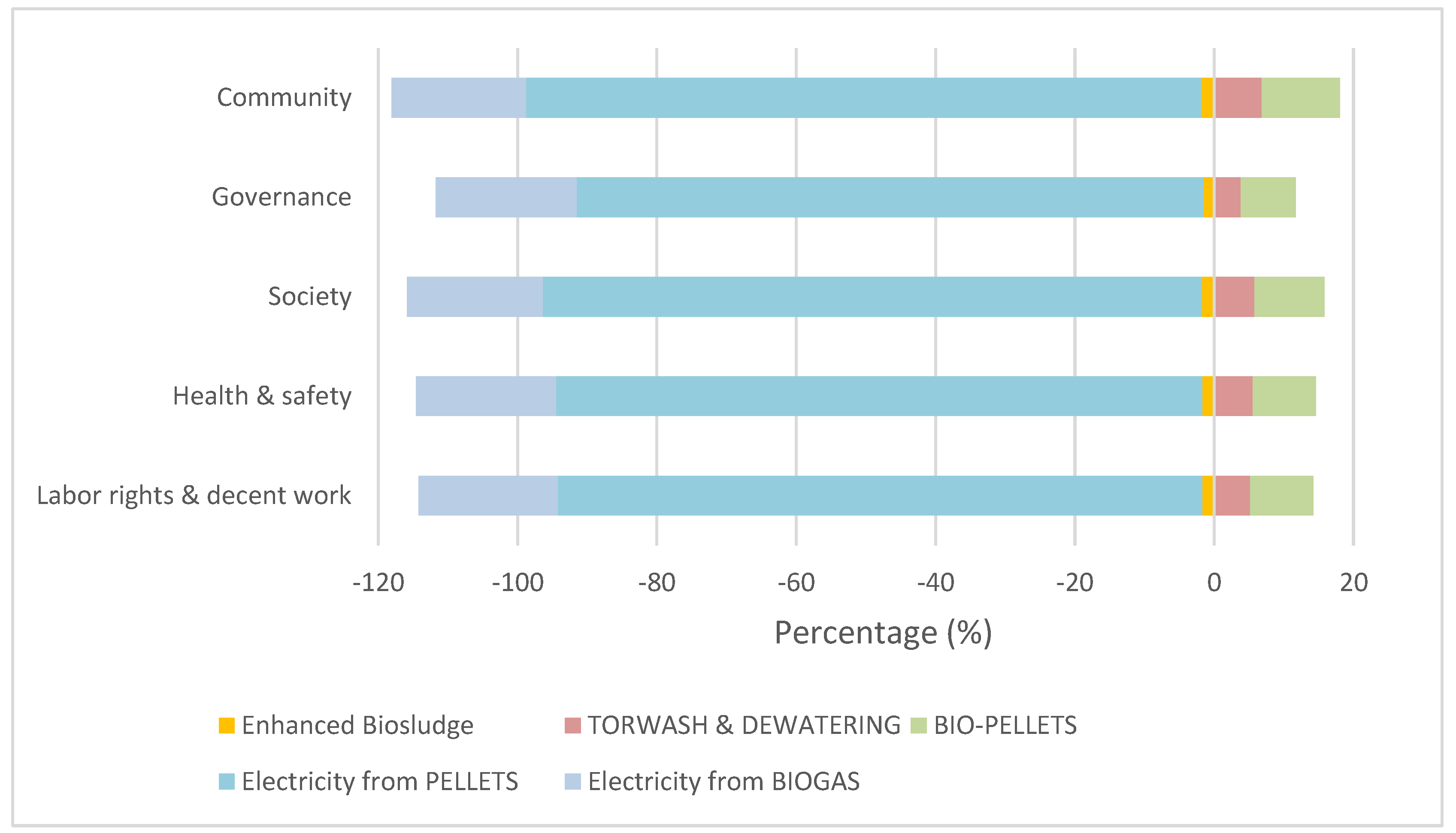

The graphical depiction in

Figure 4 confirms this, emphasizing that electricity production from Biopellets alone accounts for a dominant share of the total benefit, ranging from –90% to –97% depending on the impact category. This is a strong indication that the Swedish energy sector—characterized by high regulatory standards, strong worker protections, and integrated energy efficiency strategies like heat recovery—transforms what might otherwise be neutral processes into socially advantageous operations.

Conversely, the histograms chart highlights that Biopellets production and the Torwash and dewatering steps are the primary contributors to the remaining social risks. These account respectively for 8–11% and 4–7% of the total impact. Although these figures are modest in absolute terms, their consistent presence across categories points to localized, sector-specific risks, possibly related to labor intensity or technical labor demands in machinery operation. The minimal contributions from the enhanced biosludge treatment process further support the conclusion that upstream operations in Sweden present limited social risk, in line with the country’s overall strong socio-economic baseline.

In contrast, the Olive Pomace case study, centred in the Italian region of Apulia, reveals a markedly different social profile. Every phase of the production chain—from preconditioning to final energy conversion—contributes positively to the overall social risk profile, culminating in substantial total impacts across all categories. The most striking findings relate to the bio-pellet production and electricity generation steps, which con-tribute disproportionately to the total social risks. These stages alone are responsible for large increases in social impact values, particularly in Labor rights and Health and safety. This is indicative of structural vulnerabilities within the local production environment, which may include precarious employment arrangements, variable en-forcement of occupational safety regulations, and limitations in governance mechanisms. The high scores in the Governance and community categories suggest challenges not only in transparency and institutional trust, but also in ensuring equitable access to resources and public infrastructure. Preconditioning and TORWASH processes also register moderate positive scores, signalling that even the upstream stages are embedded in eco-nomic sectors with medium to high social risks. This pattern paints a picture of a technologically promising system being deployed in a socio-economic environment that lacks the resilience or safeguards to fully capitalize on its benefits without introducing significant social burdens. While the economic opportunities associated with the F-CUBED system may be present, the current deployment context in southern Italy appears to exacerbate existing vulnerabilities rather than alleviate them.

The combination of tabular data and graphical representation, in

Figure 5 reveals a more risk-intensive profile, dominated by two critical production phases: Biopellets production and electricity generation from pellets, which together contribute between 80% and 86% of the total social impact across all categories.

Specifically, Biopellets production accounts for 44–47%, while electricity generation contributes 36–39%. This clear concentration of social risks underscores the vulnerabilities present in the relevant Italian industrial sec-tors, including exposure to variable labor conditions, limited automation, and moderate regulatory compliance in workplace safety and environmental governance. These vulnerabilities may reflect broader regional disparities in socio-economic infrastructure, particularly in Southern Italy, where the case study is situated.

Meanwhile, upstream phases like preconditioning and Torwash & dewatering have minimal social impact, each contributing only around 1–1.5% of the total in most categories. Their limited contribution aligns with low-er labor intensity and mechanization during these earlier stages. However, the fact that even these steps are not entirely impact-neutral reinforces the systemic nature of the social risks embedded in this value chain. This holistic view signals the need for targeted social safeguards and potentially a revision of workforce management practices, particularly in downstream energy operations and pellet manufacturing.

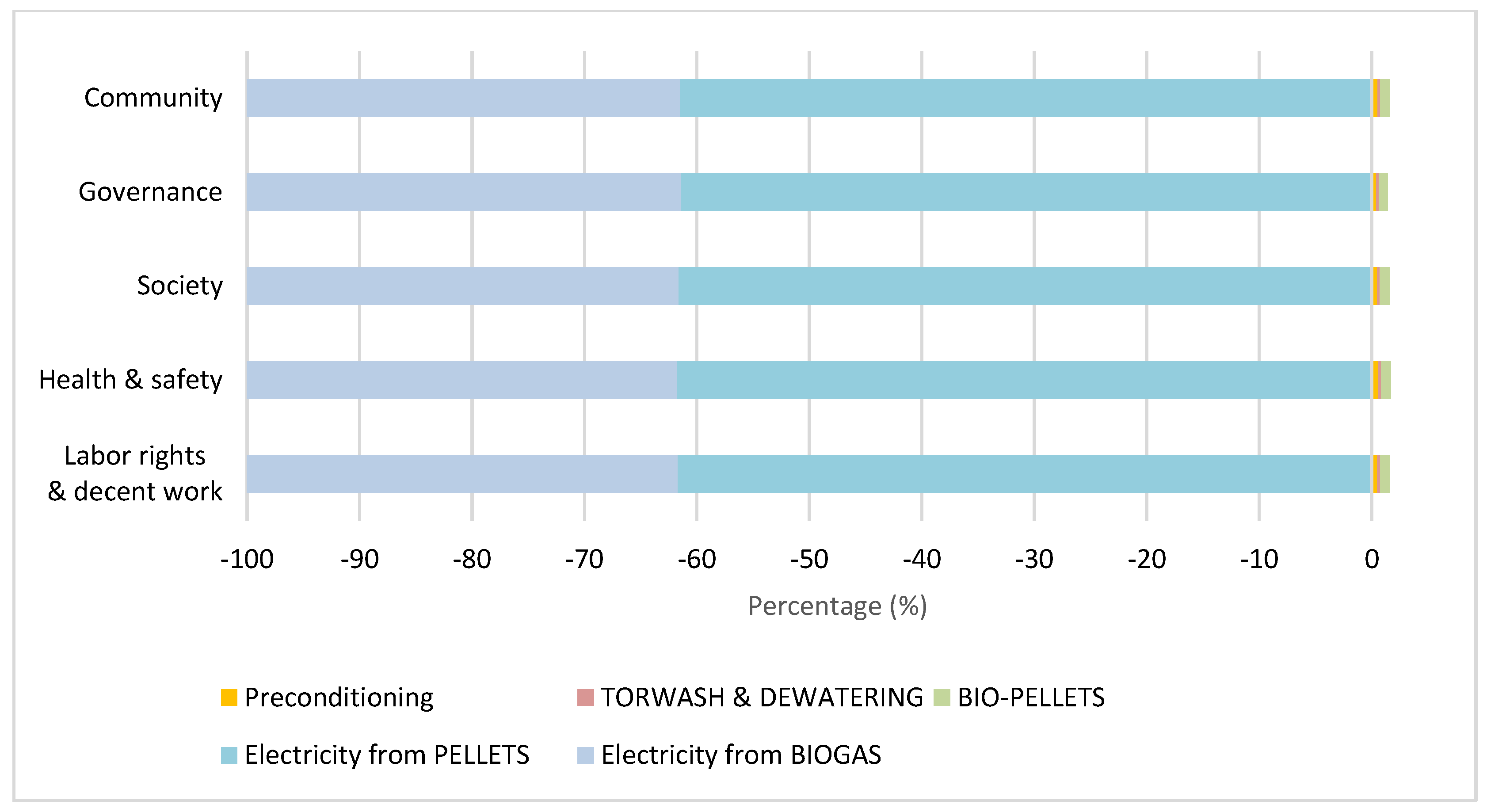

The Orange Peels case study, implemented in Spain, offers a compelling contrast, standing out as a clear example of how favourable socio-economic conditions can transform the same technology into a socially beneficial intervention. The initial stages of preconditioning and TORWASH® treatment introduce moderate social risks, particularly in Labor rights Health and safety, and Governance. These results are likely influenced by the agricultural and food processing sectors’ typical labor patterns, which may involve seasonal or low-paid work. However, once the system moves into the bio-pellet and energy generation phases, the impact profile shifts dramatically. The electricity generation phases—both from pellets and from biogas—exhibit extremely negative mrheq values across all categories, indicating large social benefits. These values suggest not only the displacement of higher-risk energy production methods but also the presence of mature regulatory environments, decent labor conditions, and robust local infrastructure. The enormous negative scores, particularly in Labor rights and Governance, reflect the ability of the Spanish system to convert industrial bioenergy production into a source of social value—improving working conditions, enhancing transparency, and providing community-level benefits. Un-like in the Italian case, where the system appears to amplify risks, the Spanish case demonstrates the potential for F-CUBED to deliver wide-reaching social co-benefits when embedded in a supportive context. The numerical data is echoed powerfully in the chart in

Figure 6, where electricity production from Biopellets emerges as the most socially beneficial phase, contributing between −62% and −40% to the total social risk reduction in several categories. This substantial benefit reflects the efficiency, maturity, and social responsibility embedded in Spain’s renewable energy infrastructure.

The Biopellets production and preconditioning phases, by contrast, contribute only marginally to the overall im-pact—0.8% and 0.5%, respectively— rendering them virtually negligible in the system’s social risk profile. These low-risk values suggest effective risk management and limited worker exposure in these phases. The Torwash & dewatering steps follow a similar pattern, contributing minimally to social risks, indicating that Spain's machinery and equipment sector operates within acceptable risk thresholds for Labor Rights and Safety.

Perhaps most interestingly, the graphical insights emphasize the specific categories that reap the most benefit in this case—namely Health & Safety and Governance. These gains go beyond process efficiency and touch on broader structural benefits: for example, domestic renewable electricity production contributes to energy sovereignty, reduces reliance on potentially unstable or undemocratic energy-exporting regions, and thus strengthens national governance frameworks. This creates a virtuous cycle where energy policy, labor standards, and community stability align to generate robust social co-benefits.

Taken together, the integrated analysis of table data and chart visualizations makes it evident that the F-CUBED Production System performs very differently depending on the economic sectoral composition and geographic deployment. In Sweden, the social benefits are driven by a highly optimized energy sector. In Italy, systemic labor and governance challenges translate into substantial social risks, particularly in the labor-intensive, energy-producing segments of the value chain. In Spain, the system functions as a net contributor to social welfare, thanks to its robust institutional and infrastructural conditions.

This cross-case comparison underscores the importance of context-aware deployment strategies. While the technology behind F-CUBED is constant, the social outcomes are not. The combination of numerical data and relative impact visualization not only reveals hidden hotspots within each sector but also points toward the strategic leverage points for mitigating social risk and enhancing benefit: targeted improvements in labor conditions in Italy, continued optimization of machinery operation in Sweden, and maintaining policy alignment in Spain. Ultimately, the integrated interpretation affirms that social sustainability in bioenergy systems must be locally tailored, even when the technological core remains the same.

3.3.3. Subcategory Level Analysis

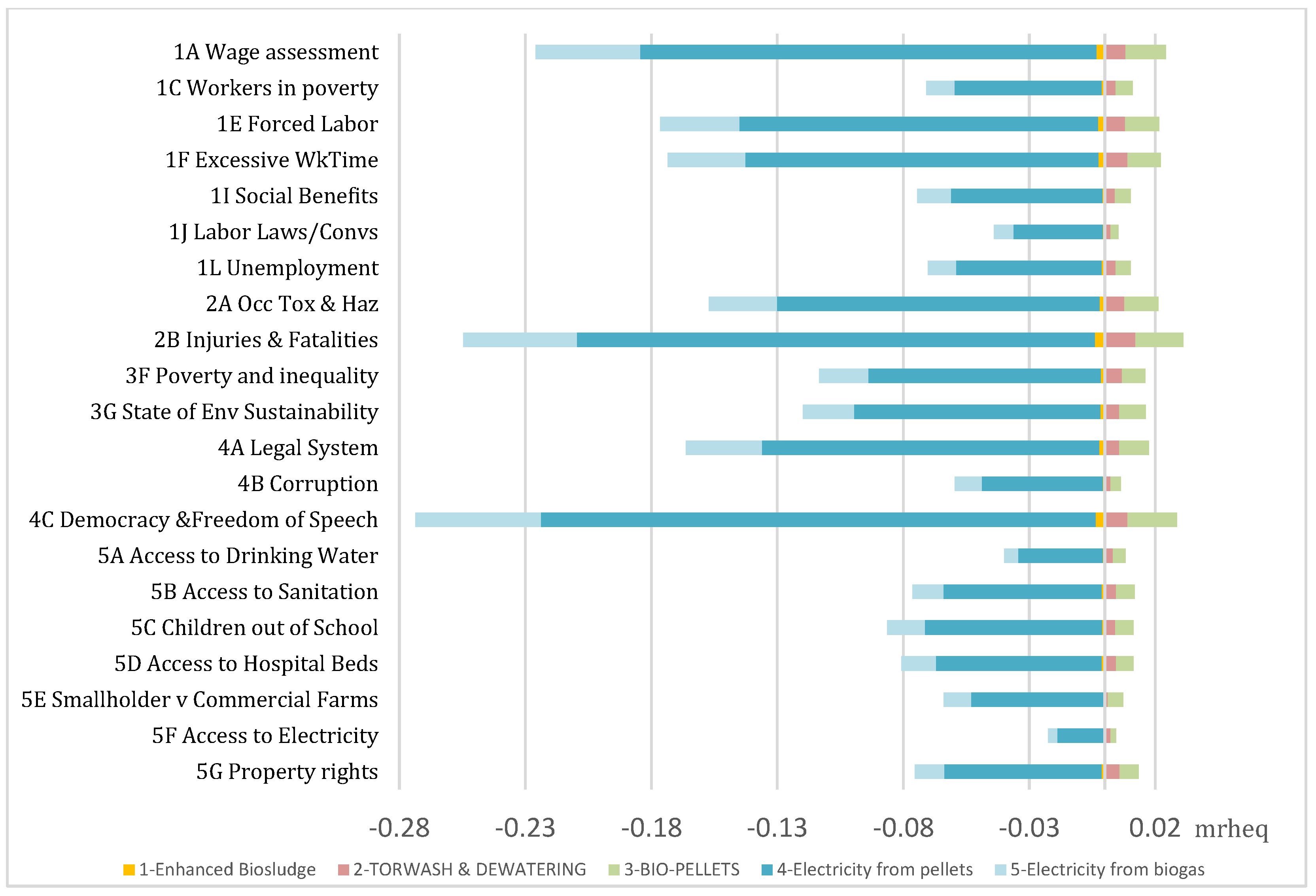

The disaggregated results of the Social Life Cycle Impact Assessment (S-LCIA) by subcategory provide an even more detailed picture of the social sustainability performance of the F-CUBED Production System across the three case studies—Pulp & Paper Biosludge in Sweden, Olive Pomace in Italy, and Orange Peels in Spain. Subcategories —mapped from SHDB to the UNEP typology—were examined to understand their distribution across economic sectors.

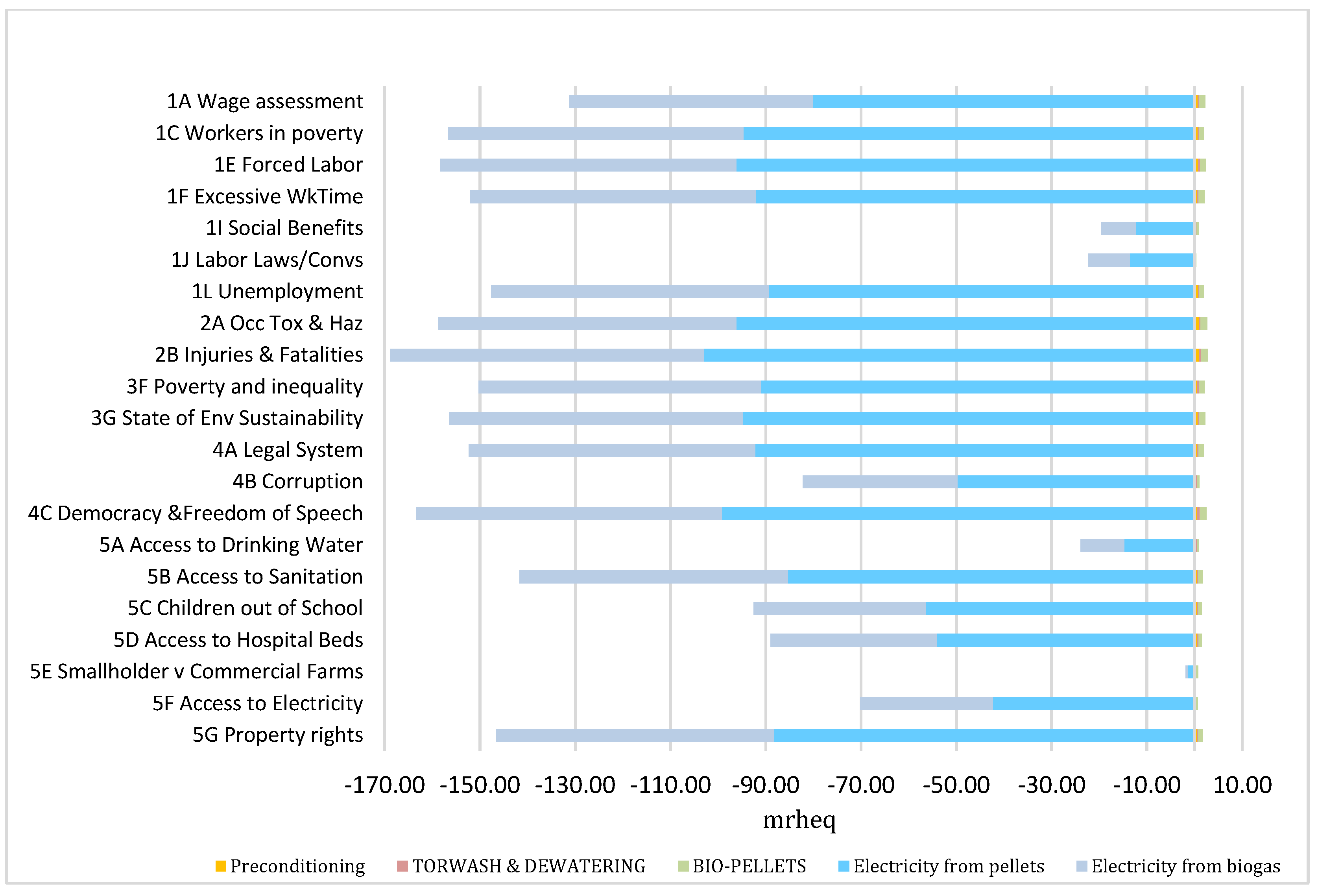

Table 10 combined with

Figure 7,

Figure 8 and

Figure 9 presentation illustrates both the absolute and relative contributions to social risk, enabling a detailed analysis of specific social dimensions, such as wage levels (1A), labor laws (1J), occupational health & safety (2A, 2B), society environmental justice (3F, 3G), governance (4A, 4B), and community-level indicators (5A–5G), expressed in medium risk hour equivalents (mrheq). This disaggregated approach facilitates the identification of sector-specific social risks and co-benefits, enabling stakeholders to more precisely target interventions aimed at improving social sustainability. It also strengthens the interpretive depth of the S-LCIA by linking aggregated results to underlying social dynamics, such as the enforcement of Labor rights or the inclusiveness of value chains. . These results underscore stark contrasts between contexts, highlighting how deeply the local socio-economic and institutional landscape shapes the social consequences of technological deployment.

For the Pulp & Paper Biosludge case study, the data show a consistent pattern of low to moderate social benefits across almost all subcategories. Negative mrheq values throughout the board signal a reduction in social risks. In the Labor rights category, subcategories like Wage assessment (1A), Workers in poverty (1C), Forced Labor (1E), and Excessive Working Time (1F) all display slight to moderate negative values, confirming the overall strength of the Swedish labor system. These conditions reflect a labor market characterized by fair wages, strong union presence, and adherence to international labor standards. Occupational safety indicators (2A, 2B) reinforce this perspective: both exposure to toxic substances (2A) and risk of injuries and fatalities (2B) are associated with small but tangible benefits, reflecting Sweden’s rigorous health and safety regulations, especially in energy and industrial sectors. On the community level, additional benefits are observed in access to services like sanitation (5B), healthcare (5D), and water (5A)—factors which, although marginal in their relative scores, indicate the presence of strong social infrastructure. The scores for Governance, particularly regarding legal systems (4A) and democracy (4C), are also negative, suggesting that the implementation of F-CUBED in this region does not encounter the systemic fragilities seen elsewhere. Overall, while the absolute values may be limited, they accumulate into a coherent picture of a socially stable and beneficial deployment context with minimal risk amplification across any social dimension.

Among the assessed subcategories , the greatest net social benefits are observed for Democracy & Freedom of Speech (4C), Injuries & Fatalities (2B), and Wage assessment (1A). This scenario is supported by

Figure 7, that depicts the disaggregated impacts across individual subcategories, and provides a clearer visualization of how the specific social themes of the subcategories are influenced by each production phase.

These benefits are predominantly associated with the electricity production phases, particularly from Biopellets, which are linked to the highly regulated and socially robust Swedish electricity sector. Conversely, the Biopellets production and Torwash with dewatering phases exhibit the highest positive contributions to social risk within the same subcategories (1A, 2B, and 4C). These phases are related to more labor- and process-intensive operations, and to economic sectors with relatively lower social performance indicators when compared to energy generation.

In sharp contrast, the Olive Pomace case study in Italy reveals substantial social risks across almost every subcategory as reported in

Table 10 and depicted in

Figure 8. The data show high positive mrheq values, indicating elevated risk levels particularly in the Labor rights health, Governance, and Community categories.

The labor-related subcategories—such as Wage assessment (1A), Worker poverty (1C), Forced Labor (1E), and Excessive Working Time (1F)—stand out significantly, with values ranging from approximately 4 to over 5 mrheq. These results suggest precarious employment conditions, likely exacerbated by informal or seasonal labor patterns in the agricultural and pellet production sectors of Southern Italy. The scores on Social Benefits (1I) and Unemployment (1L) similarly point toward systemic weaknesses in the social safety net, contributing to a context of economic vulnerability and limited career stability.

The health and safety subcategories (2A, 2B) also reveal severe risks. Both Occupational Toxics and Hazards (2A) and the incidence of workplace Injuries & Fatalities (2B) present the highest values within their category, indicating that workers in the olive pomace value chain face significant exposure to hazardous conditions, insufficient protective measures, and possible shortcomings in enforcement. This paints a concerning picture of operational safety in both processing and energy production phases.

According to European statistics on accidents at work (ESAW) administrative data collection exercise [

42], Italy shows, as fatal accidents at work in 2019, an incidence rate (per 100,000 persons employed) of 2.1 against the average of 1.7 in EU. Moreover, at national level, the National Institute for Occupational Accident Insurance (INAIL ) reports that as of 2022 December 31st, the number of accidents occurred in 2022 was 697,773, an increase of 25.7% compared to 2021, and of 25.9% compared to 2020. At the national level, the data show, in particular, an increase compared to 2021 both of the cases occurred at work (+28.0%) and those in transit, that is, occurred on the return journey between home and work (+11.9%) [

43].

From a societal standpoint, Poverty and Inequality (3F) emerge as acute problems, reinforcing the socio-economic fragility in the region. Meanwhile, Environmental Sustainability scores (3G) suggest challenges in aligning industrial innovation with broader ecological goals and assess the potential environmental risks related to supply chains. This subcategory relates to the Environmental Performance Index (EPI) indicator [

30] used to rank 180 countries on environmental health and ecosystem vitality and provide a gauge at a national scale of how close countries are to established environmental policy targets.

In terms of Governance, both the effectiveness of the legal system (4A) and corruption risks (4B) are high-lighted as major concerns, pointing to the limited institutional capacity to ensure fair and transparent implementation of new technologies.

At the Community level, the Democracy &Freedom of Speech (4C) registers the highest score in this category, underscoring latent socio-political tensions, , while essential services such as sanitation (5B), healthcare (5D), education (5C), and electricity (5F) all reflect medium to high social risks. Access to land and property rights (5G) is also a concern, likely reflecting land tenure issues or unbalanced development dynamics between smallholders and larger commercial operators (5E).

Particularly the subcategory 4C (Democracy &Freedom of Speech) relates to freedom of expression which is a fundamental Human Right, as stated in Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. The risks related to this subcategory is determined through the application of three indices: Economist Intelligence Unit's Democracy Index, and the indices produced by The Freedom House and by the IDEA. They evaluate the state of democracy worldwide on the basis of criteria such as electoral process and pluralism, the functioning of government, political participation, political culture and civil liberties [

30]. Five attributes of democracy are investigated: Representative Government, Fundamental Rights, Checks on Government, Impartial Administration, Participatory Engagement. Three groups of countries are accordingly distinguished: Free, Partly Free, and Not Free. Italy undoubtedly belongs to the first group.

A likely explanation in this view is the European experience of local communities and energy cooperatives, which demonstrate that energy democracy is the route to resolving a number of socio-economic concerns and addressing climate change [

38]. Cities and local communities around the globe have been reclaiming public services or redesigning them to meet people's needs, realize their rights, and jointly address social and environmental concerns [

45]. In Italy, although the introduction of the free market in the energy sector, ENEL is still the main producer of electricity detaching a share of 33.8% and ENI is the main producer of natural gas with a share of 62.6%, based on data provided by ARERA [

46,

47].

The electricity generation stages from pellets and biogas represent the most significant contributors, typically comprising 65%–85% of total risk across most subcategories. Biopellets production often adds 20%–30%, while upstream steps (Preconditioning and TORWASH®) usually contribute less than 10%, rarely exceeding that threshold. This breakdown confirms that downstream interventions are essential to improve the social performance of the F-CUBED system in the Olive Pomace pathway. These include targeted strategies in energy-related supply chains, improved labor practices, and attention to local community infrastructure and legal protections.

In summary, the cumulative interpretation is that the F-CUBED system, while promising technologically, is deeply embedded in a context of socio-economic fragility in the Italian case study, and without careful mitigation, it risks reinforcing or even exacerbating existing social inequalities.

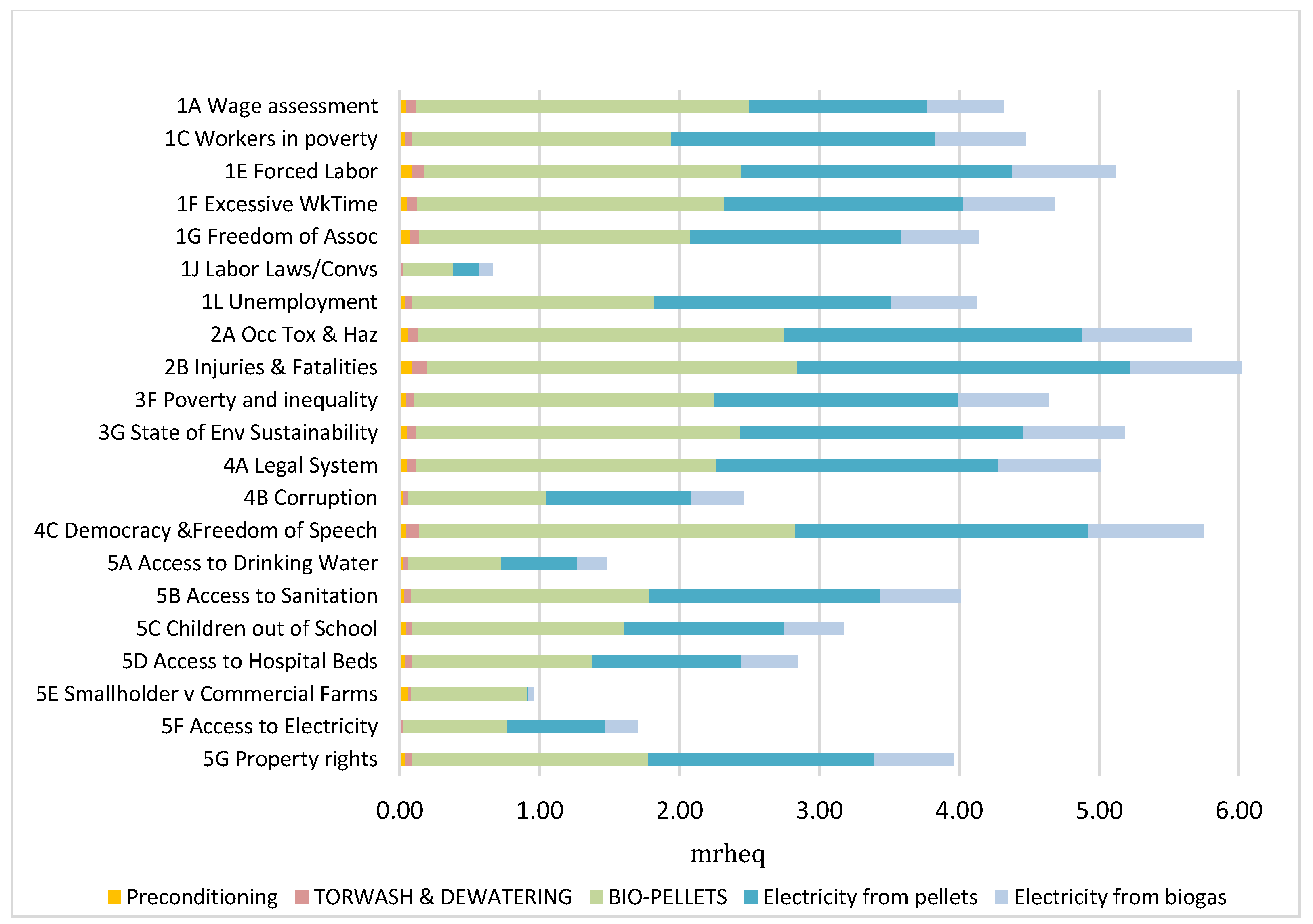

The situation in the Orange Peels case study, implemented in Spain, is markedly different and positive in social terms. Here, the impact scores across all subcategories are substantially negative—often strikingly so—signifying robust social benefits. In the Labor Rights category, every subcategory from Wages (1A) to Labor Law compliance (1J) to Unemployment (1L) reflects significant risk reduction. Forced Labor (1E) and Excessive Working Time (1F), two critical global labor concerns, show particularly large negative values, suggesting that Spain’s institutional environment for labor governance is not only functional but able to turn potentially vulnerable labor-intensive sectors into socially secure and compliant workplaces. Health and safety indicators (2A, 2B) follow the same trend. The subcategories assessing Occupational Toxics and Hazards (2A) and Injuries & Fatalities (2B) both show extremely negative values, highlighting high occupational safety performance, particularly in the energy generation and biomass handling processes.

Societal indicators (3F, 3G) echo this pattern, with Poverty and Inequality (3F) registering considerable improvements, likely reflecting the integration of marginalized residues (such as orange peels) into a productive and economically beneficial value chain. The category State of Environmental Sustainability (3G) also shows strong performance, underscoring how the valorisation of agri-food residues can contribute to broader sus-tainable development goals in practice, rather than theory.

Governance-related scores (4A, 4B) are also impressively positive. The Legal System (4A) subcategory and the indicator for Corruption (4B) both show strong risk reductions, affirming institutional reliability and transparency. These institutional strengths are further complemented by dramatic positive values in Community-related subcategories (4C, 5A–5G), especially in Democracy and Freedom of Speech (4C). These results are highly relevant in today’s geopolitical context, where domestic renewable energy production can be a lever to promote not only environmental resilience but also democratic integrity. Improved access to basic services, such as electricity (5F), water (5A), and healthcare (5D), further reinforces the positive narrative. The benefit extends even to more context-specific indicators like Property Rights (5G) and the balance between small-holder and commercial agriculture actors (5E), suggesting that this specific bioenergy pathway does not marginalize smaller producers or generate land-use conflict. Instead, it appears to operate in a socially integrative and structurally sound manner.

The visual format of the data in the

Figure 9 highlights at a glance the areas of strongest performance and those where potential improvements may be targeted. The most favourable social performance is observed in the Electricity generation stages (from both pellets and biogas), particularly in the areas of Occupational Health and Safety and Fair Salary. These stages benefit from low-risk profiles typically associated with regu-lated energy sectors in Spain.

In contrast, higher social risks—though still within favourable ranges given the negative scoring system—are associated with the Preconditioning and Torwash & Dewatering stages. This can be attributed to the relatively higher labor intensity and upstream supply chain dependencies of these processes, which may involve material or labor inputs from higher-risk sectors.

In the Biopellets production phase, a moderate performance is recorded, with notable positive contributions in the subcategories of Community Engagement and Value Creation. This suggests a potential for localized economic development and social inclusion, aligning with circular economy principles.

In conclusion, the comparative analysis of the subcategory-level results illustrates how the same technological system—F-CUBED—can produce profoundly different social outcomes depending on the deployment con-text. In Sweden, the system adds marginal but steady value in a setting that is already socially secure. In Italy, it exposes and potentially deepens systemic vulnerabilities in Labor Rights, Public Health, Governance, and Community access to basic services. In Spain, however, it emerges as a strong enabler of social progress, delivering tangible and wide-ranging benefits across all assessed dimensions. These findings reinforce the essential role of social context in life cycle assessment and underline the need for tailored implementation strategies that go beyond technological efficiency to ensure inclusive, equitable, and socially sustainable innova-tion.

3.3.4. Risk Characterization

This section describes the risk characterization of the numeric impact scores into performance levels (low, medium, high, very high risk) using SHDB’s ordinal Performance Reference Point (PRP) system. These models apply performance reference points and severity-based weighting factors to translate raw impact values into qualitative risk levels. It represents an fundamental step to consolidate category and subcategory level assessments across geographic contexts, supporting the prioritization of social risk mitigation and stakeholder engagement actions. The characterization thresholds and algorithms used in this analysis are transparently documented in the SHDB framework and have been detailed in the

Section 2.2.5.

For the Pulp & Paper Biosludge case study in Sweden, based on the Social Life Cycle Impact Assessment (S-LCIA), all subcategories —even those with the highest absolute impacts—are classified as “Low Risk”, indicating that the observed social issues fall within an acceptable range from a sustainability perspective.

These results demonstrate a generally low-risk social profile across all evaluated subcategories and align with Sweden’s robust social protection frameworks, high labor standards, and democratic institutions.

The Electricity from pellets phase consistently shows the strongest social benefits, and supports the earlier finding that in Sweden, bioenergy valorisation contributes positively not only to environmental goals but also to social sustainability, particularly when embedded in a well-regulated energy economy.

The upstream processes (Preconditioning/Enhanced Biosludge) and Torwash show almost neutral or marginally positive values—expected given their limited exposure to systemic labor or governance risks. The Biopellets phase, while showing some low positive values, still falls within safe limits and does not indicate any critical hotspot. These characterization results confirm that the implementation of the F-CUBED Production System in the Swedish pulp and paper sector is socially low-risk and institutionally aligned. Social impacts are well managed across all process steps, and the most mature downstream sectors, particularly Electricity generation, contribute to risk reduction. This makes the Sweden-based biosludge case study a benchmark for best-practice social integration in circular bioenergy systems.

For the Olive Pomace case study in Italy, despite all processes being situated within the same national context, the social risk levels vary significantly depending on the production phase, with downstream activities—especially Biopellets and Electricity generation from pellets—emerging as the most socially vulnerable. The most critical social risks are concentrated in the Biopellets and Electricity from pellets phases, which consistently reach Medium Risk levels across the key subcategories: Forced Labor (1E), Occupational Toxics and Hazards (2A), Injuries & Fatalities (2B), Environmental Sustainability (3G), and Democracy &Freedom of Speech (4C).

Preconditioning, TORWASH & Dewatering, and Electricity from biogas remain generally low in risk, showing that upstream and more mechanized or closed-loop phases pose minimal social concern. The medium risks are not extreme, but their repetition across categories and concentration in specific phases suggest clear hotspots for social performance improvement, especially: worker safety and protective measures, formalization and transparency in labor contracts, stakeholder engagement in local environmental and governance issues. In addition to the social risks identified in the subcategories already discussed (i.e. 2A, 2B and 4C) for the Italian case study, some comments have to be added for the Forced Labor (1E) and Occupational Toxics and Hazards (2A). The subcategory Forced Labor (1E), according to [

30] constitutes a violation of fundamental human rights. It deprives societies of developing skills and human resources and educating children for the future labour market. The ILO Conventions also provides that forced labour shall be punishable as a penal offense [

30]. Here the occurrence of a medium risk level in the economic sectors of the Biopellets production and electricity sector, respectively, requires further investigations and accuracy in monitoring these production steps of the F-CUBED supply chain in Italy. The existence and effective application of a comprehensive anti-trafficking law and criminal accountability are essential elements that have to be looked upon.

The medium risk level in the subcategory 2A is also a relevant issue. The subcategory of Occupational Toxics and Hazards deals with the exposure of humans to various risks, such as hazardous noise levels, carcinogenic substances, and airborne particles that may cause respiratory or other health diseases. Therefore it means that these economic sectors of the F-CUBED supply chain in Italy doesn’t comply the average level of risk of Europe.

Nevertheless, in the whole picture of the Olive Pomace Case Study, the two subcategories Smallholder vs Commercial Farms (5E) and Labor Laws (1J) showing low risk in all the involved economic sectors can be read as opportunities. Particularly the Smallholder vs Commercial Farms impact subcategory is noteworthy. Smallholder farms should be considered a unit within the local economy, community, and agricultural environment, contributing significantly to economic growth, poverty reduction, and the local population's food security when supported with initiative from their local governments and communities. This translates to the potential of the F-CUBED Production System to represent a theoretical alternative technical solution deployable at mill level (or associates mills) differently from the conventional olive pomace exploitation involving a third party industrial entity, such as olive pomace mills. Therefore the Low Risk level reflects likelihood of the existence and prosperity of smallholders.

This characterization reinforces the need for context-aware, phase-specific social risk mitigation strategies, particularly in regions where economic precarity overlaps with industrial innovation. Addressing these risks early will strengthen both the social license to operate and the broader sustainability credentials of the F-CUBED technology in Italy. Mitigation strategies tailored to the olive pomace context are recommended, such as emphasizing the enhancement of supply chain transparency through blockchain traceability, which could reduce corruption risks by 30–40% [

48]. Additionally, strengthening labor rights enforcement and promoting stakeholder engagement are proposed as key measures to address the identified social risks. These strategies align with the broader goal of improving social sustainability within the F-CUBED Production System while maintaining compliance with relevant international standards.

The characterization results for the Orange Peels case study in Spain, evaluated through the Social Hotspot 2022 Category Method, provide valuable insight into which production phases of the F-CUBED system are responsible for social risks across specific subcategories. Although the overall system demonstrates a strong social sustainability profile—highlighted by significant negative values (i.e., social benefits) in the Electricity generation phases—the Biopellets production phase consistently emerges as the main source of social risk across nearly all categories.

Indeed all the social impact subcategories are affected, although with varying magnitude, by favourable influence on the overall social risks from the development of the F-CUBED Production System in the Orange Peels case study in Spain and the values range from -1.1 to -166.0 mrheq for all the subcategories.

Nevertheless the economic sector of Lumber and Wood Products Production which include and represent the production phase of Biopellets production phase in Spain is the primary economic sector responsible for concentrated social risks It is the only phase classified as Medium Risk across all evaluated subcategories—ranging from Labor Rights and Occupational Safety to Environmental and Governance dimensions. This indicates a need for: improved labor protections, including monitoring of working hours, contract fairness, and workplace safety measures; greater transparency and social responsibility in the pellet supply chain; integration of sustainability standards, especially regarding environmental stewardship and fair benefit distribution to local communities.

Meanwhile, the Electricity generation phases—both from pellets and biogas—consistently demonstrate negative impact scores, suggesting they are strong enablers of social benefit and constitute a model of good social practice within the F-CUBED system. These benefits are likely due to the high regulatory standards and modernization of Spain's energy infrastructure.

The risk landscape of the Orange Peels pathway confirms that social risks are highly phase-dependent, and in this case, are isolated primarily to the Biopellets production sector. Addressing these risks through policy, monitoring, and stakeholder engagement would further strengthen the social sustainability of the F-CUBED system in Spain, turning an already high-performing value chain into a best-practice benchmark for bio-based innovation in the EU.