Virtually all terrestrial plant species possess epidermal outgrowths that resemble hair-like projections. These structures, generally referred to as trichomes when located on aerial parts, are multifunctional adaptations that play significant roles in plant survival [

1]. When similar outgrowths occur on roots, they are typically called root hairs, emphasizing their distinct physiological context. Etymologically, the term “trichomes” is derived from the Greek word “

trichos,” meaning hair, highlighting their morphological resemblance. Despite their superficial resemblance to vascular or ground tissues, trichomes are in fact specialized epidermal extensions rather than integral components of the plant’s internal vascular system [

1].

1.1. Diversity and Functional Roles of Trichomes

Trichomes exhibit considerable diversity in both form and function. They may be non-glandular (often acting as simple hairs) or glandular, wherein specialized secretory cells produce and store bioactive compounds [

2]. Non-glandular trichomes can deter herbivores by creating physical barriers or by reducing palatability, while also regulating leaf temperature and water loss through light reflection—an adaptation particularly important in arid environments [

3,

4]. Meanwhile, glandular trichomes can synthesize an array of secondary metabolites, including essential oils, alkaloids, and terpenes, which serve defensive, allelopathic, or communicative functions [

3]. Consequently, trichomes act as a protective barrier against biotic threats (herbivores, pests, and pathogens, e.g.) and abiotic stressors, such as UV radiation and excessive transpiration. Interestingly, in certain species, they also facilitate seed dispersal or seed protection [

4,

5].

Structurally, trichomes are typically classified according to their cellularity (single-celled vs. multicellular), branching pattern (branched vs. unbranched), and secretory activity (glandular vs. non-glandular) [

2]. They also take on diverse shapes such as star-like (stellate), hooked, peltate (scale-like), or capitate (headed). Larger, more conspicuous trichomes are often found on leaf undersides (abaxial surfaces) or along leaf edges, while smaller trichomes can appear in stomatal regions or in association with vascular bundles [

6]. Notably, the presence of dense trichomes in some species increases epidermal thickness and may enhance the production of long-chain fatty acids, thus reducing water loss and stabilizing leaf temperature [

7]. Recent transcriptomic studies suggest that the formation and specialization of trichomes are controlled by intricate genetic networks—highlighting a balance between the plant’s developmental signaling and environmental cues [

8,

5].

1.2. Trichomes in Cannabis sativa L

Among the myriad plant species exhibiting trichomes,

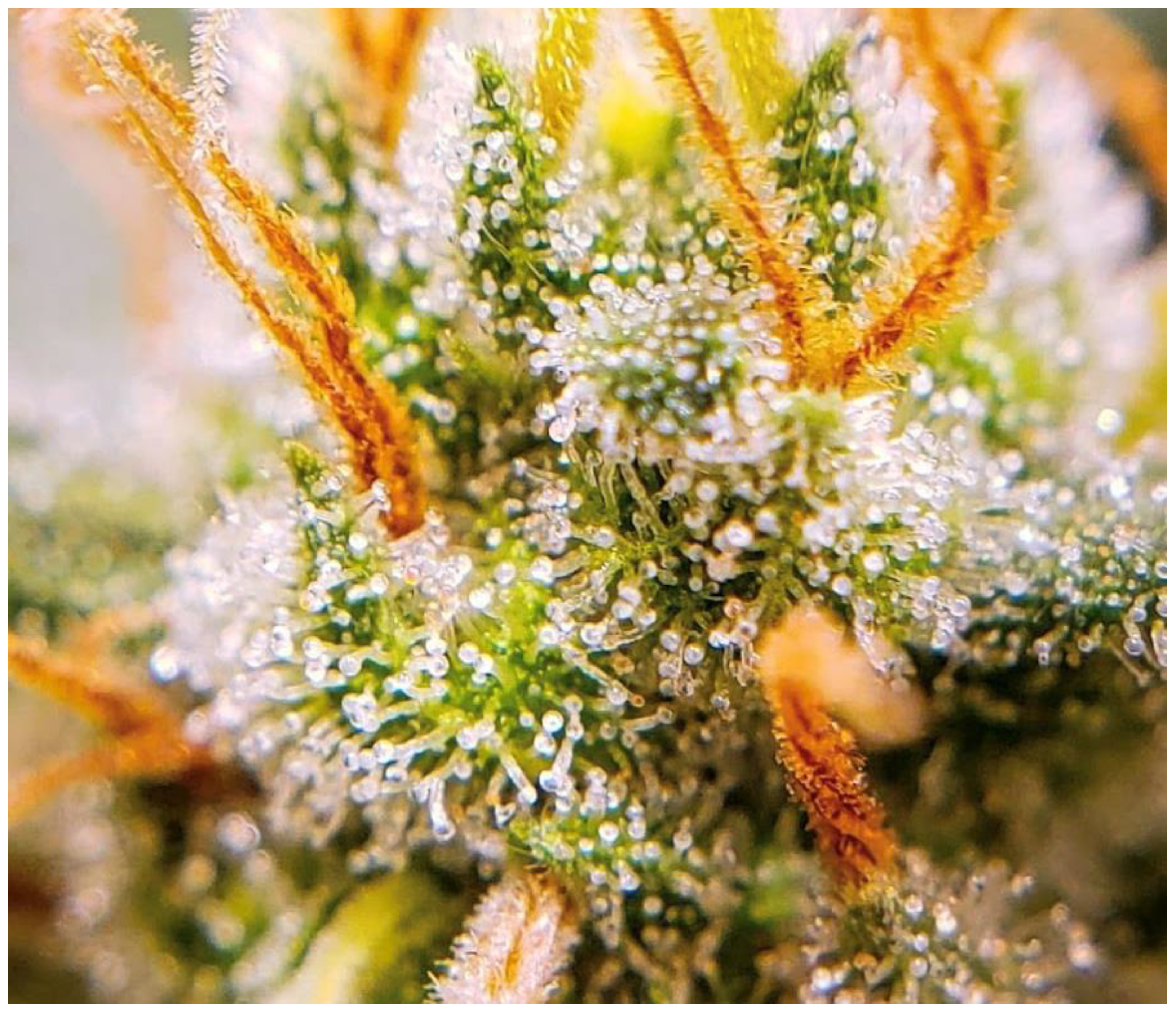

Cannabis sativa L. stands out for the medicinal and commercial significance of the metabolites produced in its glandular trichomes (

Figure 1). Cannabis flowers, particularly those of female plants, have garnered attention due to their production of cannabinoids (e.g., Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol [THC], cannabidiol [CBD]) and terpenes, compounds highly valued in both therapeutic and recreational contexts. Trichome biosynthesis of these specialized metabolites is influenced by the interplay of genetic factors, developmental stage, and environmental conditions, including light spectrum and intensity, temperature, and physical stress [

9,

10].

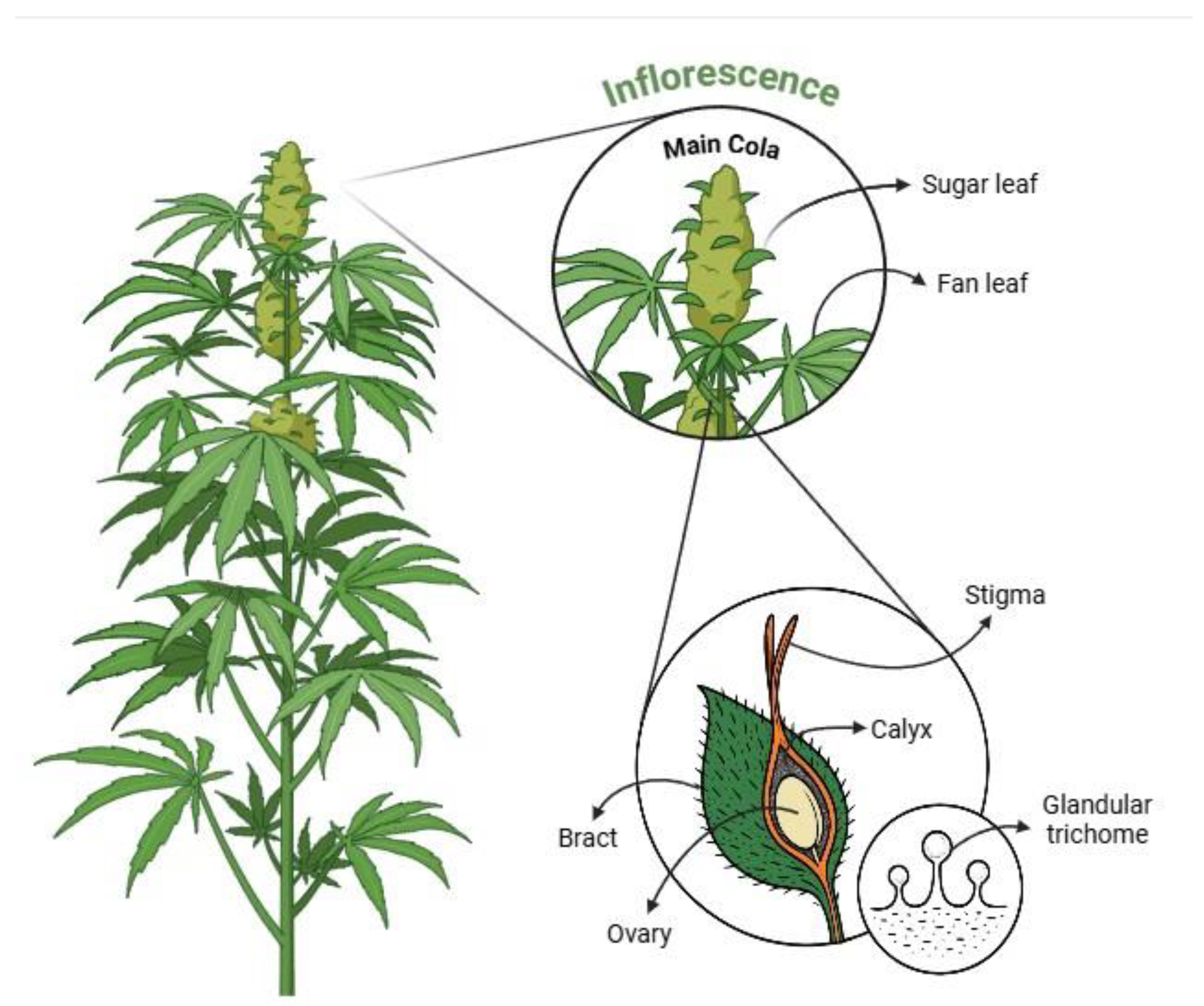

On a morphological level, female Cannabis flowers possess at least three distinct glandular trichome types based on their surface features and stalk length: bulbous, sessile capitate, and stalked (pedicellate) capitate [

11].

Bulbous trichomes are the smallest and are dispersed across various aerial surfaces of the plant. Despite their ubiquity, they remain the least characterized, partly due to their diminutive size.

Sessile capitate trichomes have a more prominent glandular head and are typically abundant on sugar leaves and bracts.

Stalked (pedicellate) capitate trichomes are generally larger and often regarded as the principal source of cannabinoids and terpenes within female inflorescences. These structures are most visible to the naked eye during the later flowering stages, creating the characteristic “frosty” appearance on colas and sugar leaves [

10].

Notably, bracts in female Cannabis flowers frequently harbor higher densities of these glandular trichomes and thus represent crucial sites for cannabinoid and terpene biosynthesis [

10,

12]. As a result, the distribution, density, and maturity of trichomes in specific floral regions—ranging from bracts and calyxes to sugar leaves—have become a focal point of breeding and cultivation strategies aimed at optimizing resin yield and the biochemical composition in terms of the bioactive compounds of interest. Importantly, beyond their biochemical significance, these trichomes also offer protective functions, forming a defensive barrier against pests and environmental stresses during critical reproductive phases. Furthermore, higher trichome density creates a desirable aesthetic attribute for consumers.

Considering this dual role—both functional defense and bioactive compound biosynthesis and storage—trichomes in C. sativa L. are of paramount interest to researchers and cultivators. Understanding the morphological, genetic, biochemical, and environmental factors that govern trichome development and metabolism enables more precise cultivation practices and efficient breeding programs, ultimately influencing the quality and consistency of Cannabis-derived products. The following sections delve deeper into the methods for assessing trichome density in various Cannabis structures, with the aim of establishing reproducible and standardized approaches in both research and industrial applications.

C. sativa L. flowers are consumed for their specific medicinal and recreational purposes according to the properties of their specialized metabolites (i.e., cannabinoids and terpenes). Based on their surface morphology, three different forms of glandular trichomes have been identified in female Cannabis flowers: bulbous, sessile, and stalked [

11]. The bulbous trichomes are the smallest and least studied, distributed across the surface of the plant. The sessile capitate trichomes have a larger glandular head and are commonly found on sugar leaves and bracts. In their turn, pedicellate capitate trichomes, more abundant in tissues rich in cannabinoids, are typically found on the bracts of female flowers and are the primary sites of cannabinoid and terpene biosynthesis. These trichomes are visible to the naked eye and are most abundant during the flowering phase, covering the colas and sugar leaves [

10].

The glandular trichomes of C. sativa play a central role in the biosynthesis and storage of cannabinoids and terpenes, compounds with recognized therapeutic, psychoactive, and commercial relevance. Trichome density is often considered an indicator of flower quality, particularly in relation to resin production and extraction yield. However, the lack of standardized protocols for measuring trichome density hinders comparison across studies and limits its reliability as a quality criterion in breeding and industry practices. Additionally, trichome distribution and morphology vary among floral structures—such as bracts, sugar leaves, calyces, and the main cola—raising the question of which plant region best represents overall trichome density in analytical assessments.

The density and morphology of glandular trichomes vary markedly among different floral structures of

C. sativa, including bracts, sugar leaves, calyxes, and the main cola. At the anatomical level, glandular trichomes house specialized secretory cells in their head region, which synthesize and store secondary metabolites such as cannabinoids and terpenes within a subcuticular cavity [

5,

11]. The accumulation of these metabolites is a dynamic process influenced by a confluence of factors—environmental conditions, developmental stage, and genetic background.

Recent genotype × environment (G×E) studies have shown that variations in light spectrum, temperature, humidity, and even UV-B light exposure can significantly modulate trichome density and secondary metabolite profiles [

8,

9]. Meanwhile, the age of the plant and the onset of the flowering stage can shift the trichome’s developmental trajectory, impacting both the density and chemical composition over time [

10]. For instance, Punja et al. (2023) [

10] noted that the number of capitate trichomes and pedicel length differed significantly across genotypes and between the upper and lower surfaces of bracts, underscoring the intricate interplay between genetics and plant morphology. These findings illustrate how structural variations in trichomes can affect the quality and consistency of the final product by influencing the content of cannabinoids and terpenes.

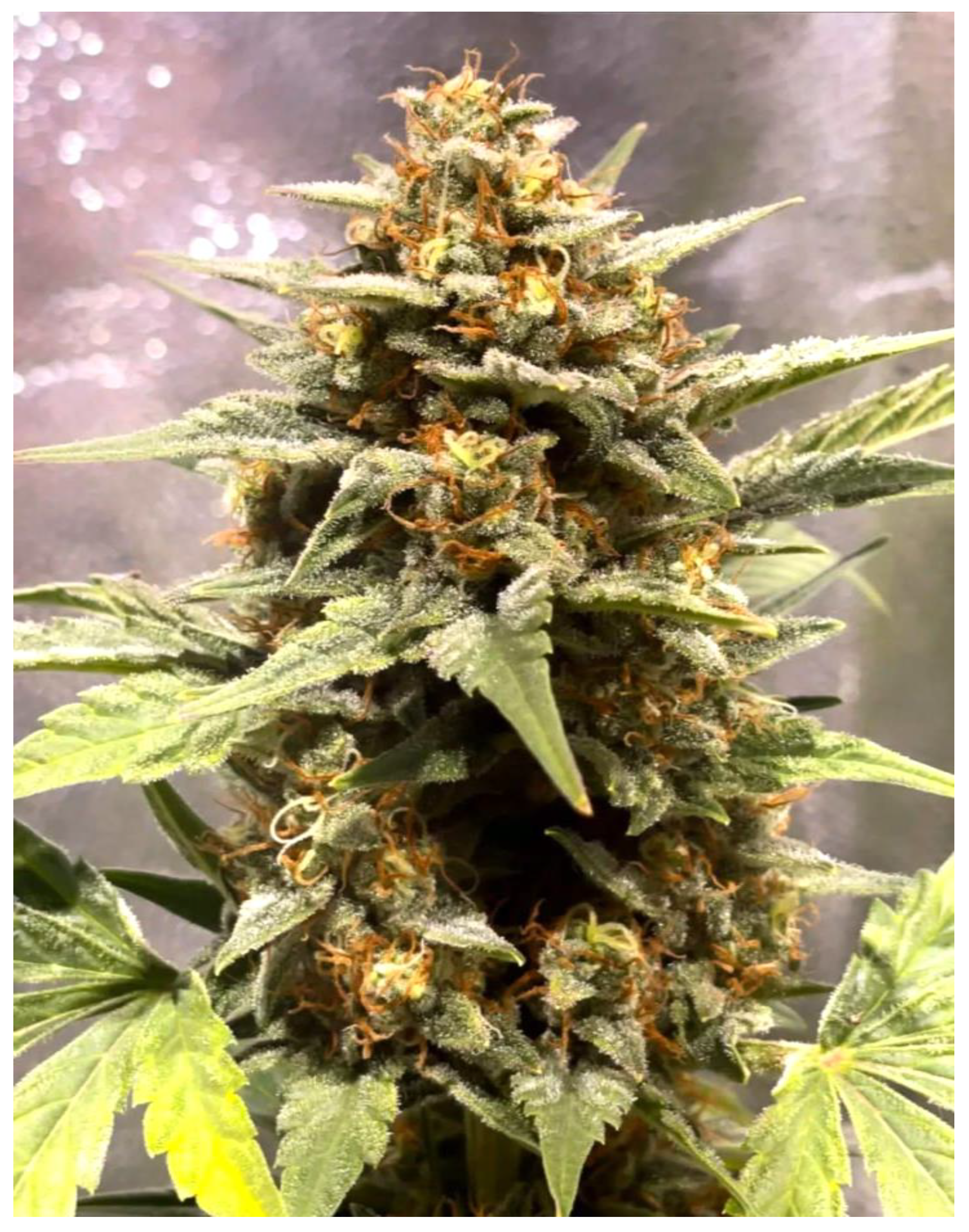

Beyond their biochemical relevance, trichomes also play a pivotal role in the visual and commercial appeal of

C. sativa flowers, particularly in the recreational market. A dense covering of glandular trichomes imparts a characteristic “frosty” appearance to flowers, as shown in

Figure 2, which is often perceived by consumers as an indicator of higher potency and quality. Consequently, breeders and cultivators target enhanced trichome coverage through selective breeding, aiming to maximize both resin yield and market value [

11]. For medicinal applications, consistent trichome density across harvests helps ensure reproducible therapeutic efficacy, while for recreational consumers, the visual allure can significantly influence purchasing decisions.

Despite its critical importance, accurately assessing trichome density remains challenging. Variability across plant structures—bracts, sugar leaves, calyxes, and main cola tissues—can be substantial, and lack of standardized protocols further complicates reliable comparisons across different studies and commercial operations [

5]. Moreover, trichome shape and size must be taken into consideration when correlating trichome density with secondary metabolite levels. A robust, reproducible methodology for trichome counting would therefore be of immense value, facilitating consistent cannabinoid yield assessments and quality control in both research and industry contexts. Recent efforts have begun to explore more refined imaging techniques and computational tools for trichome quantification, but these methods require broader validation and consensus [

8].

This review explores the methods used to count trichomes on different Cannabis structures, examines structural variation in trichome density, assesses available quantification techniques, and proposes future directions for standardization in both research and industrial applications.