Submitted:

29 April 2025

Posted:

30 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

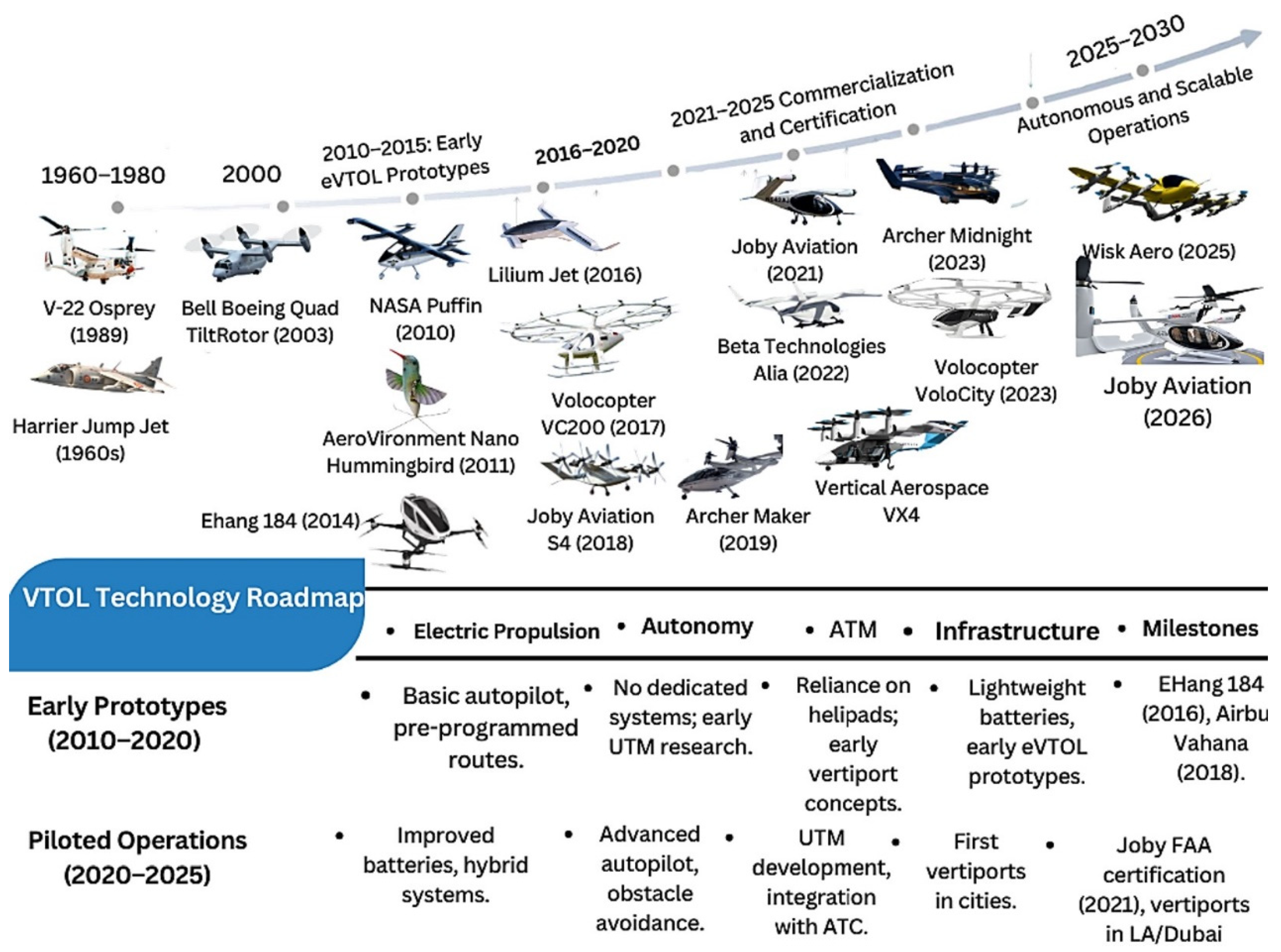

1. Introduction

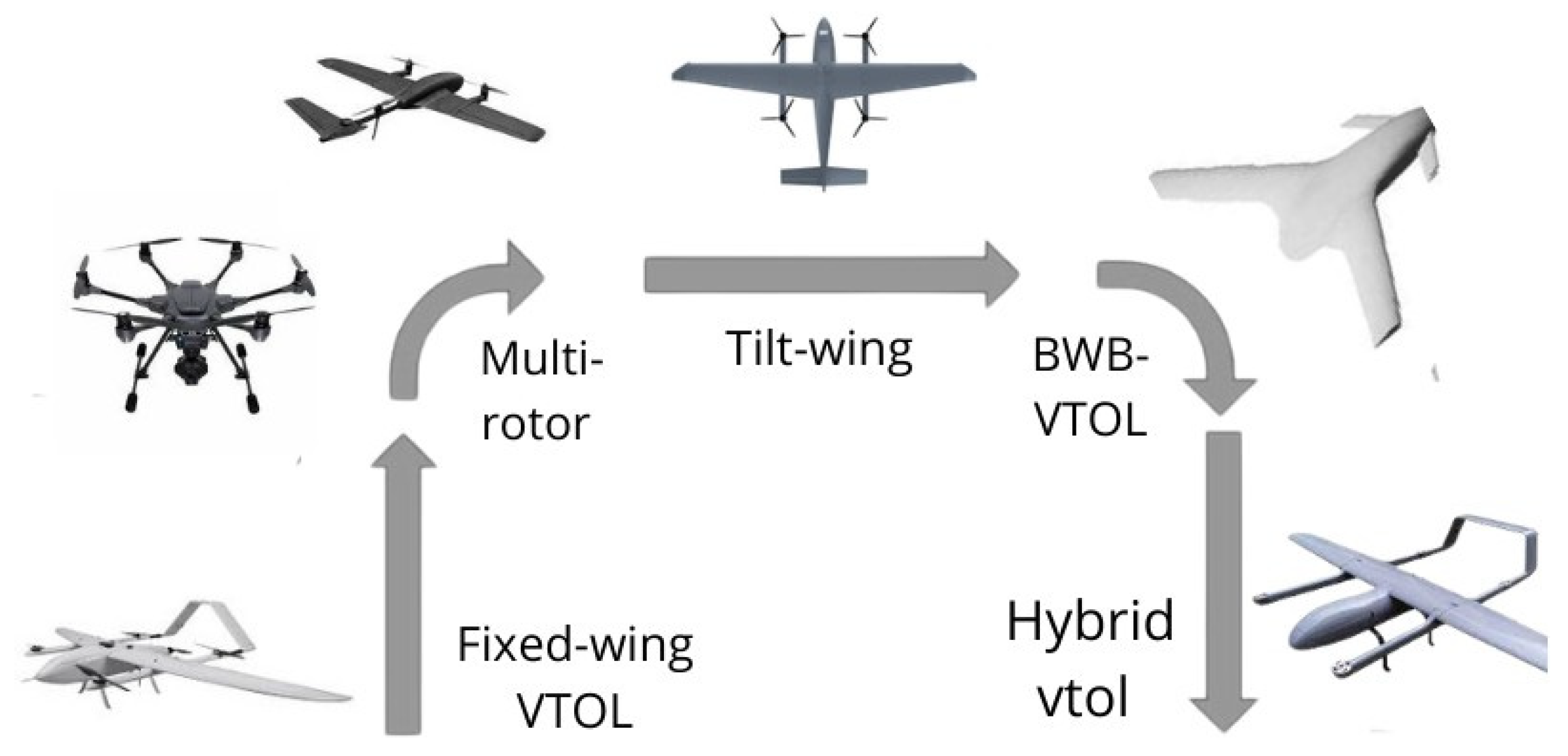

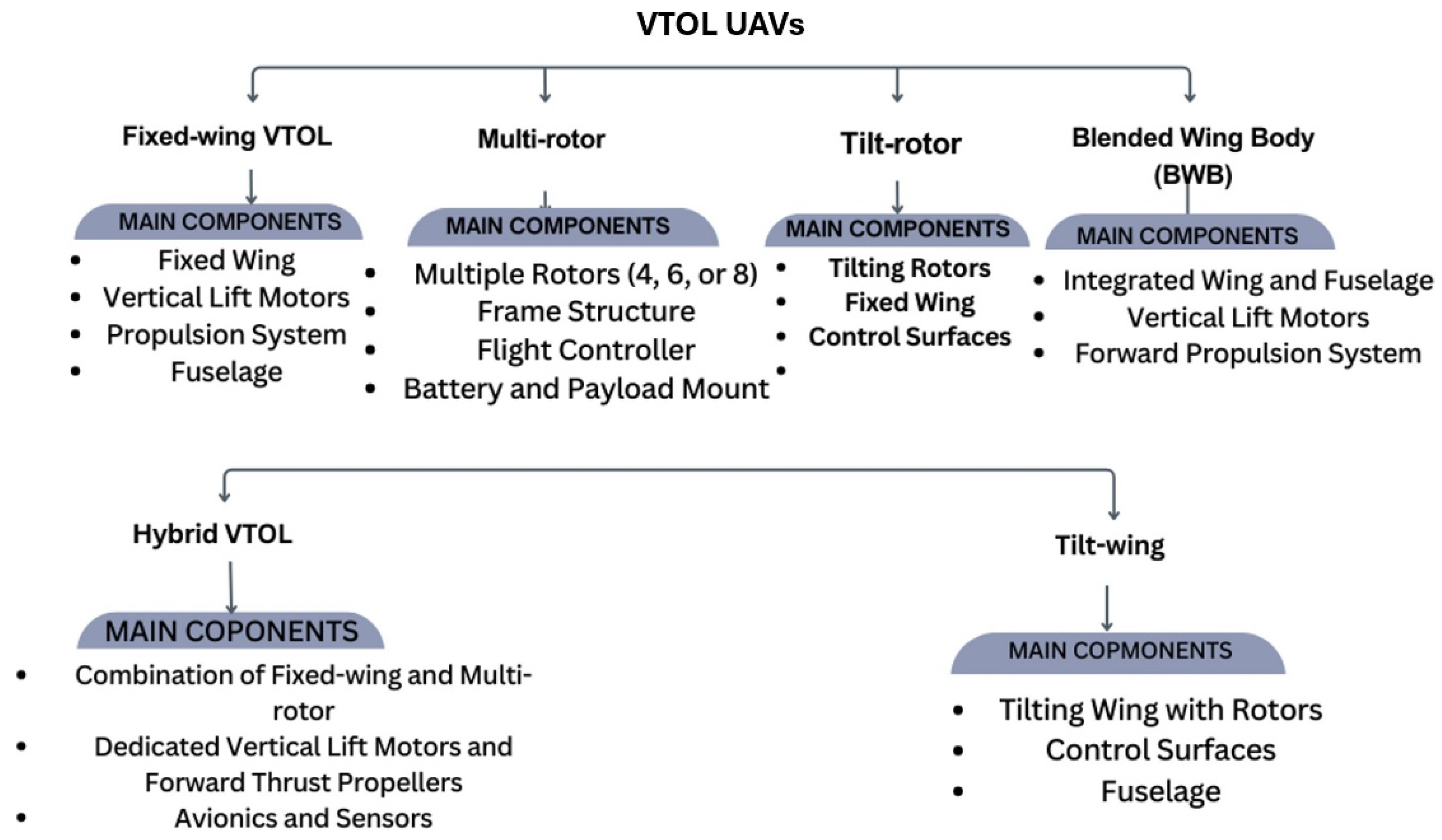

2. Classification and Configurations of VTOL UAVs

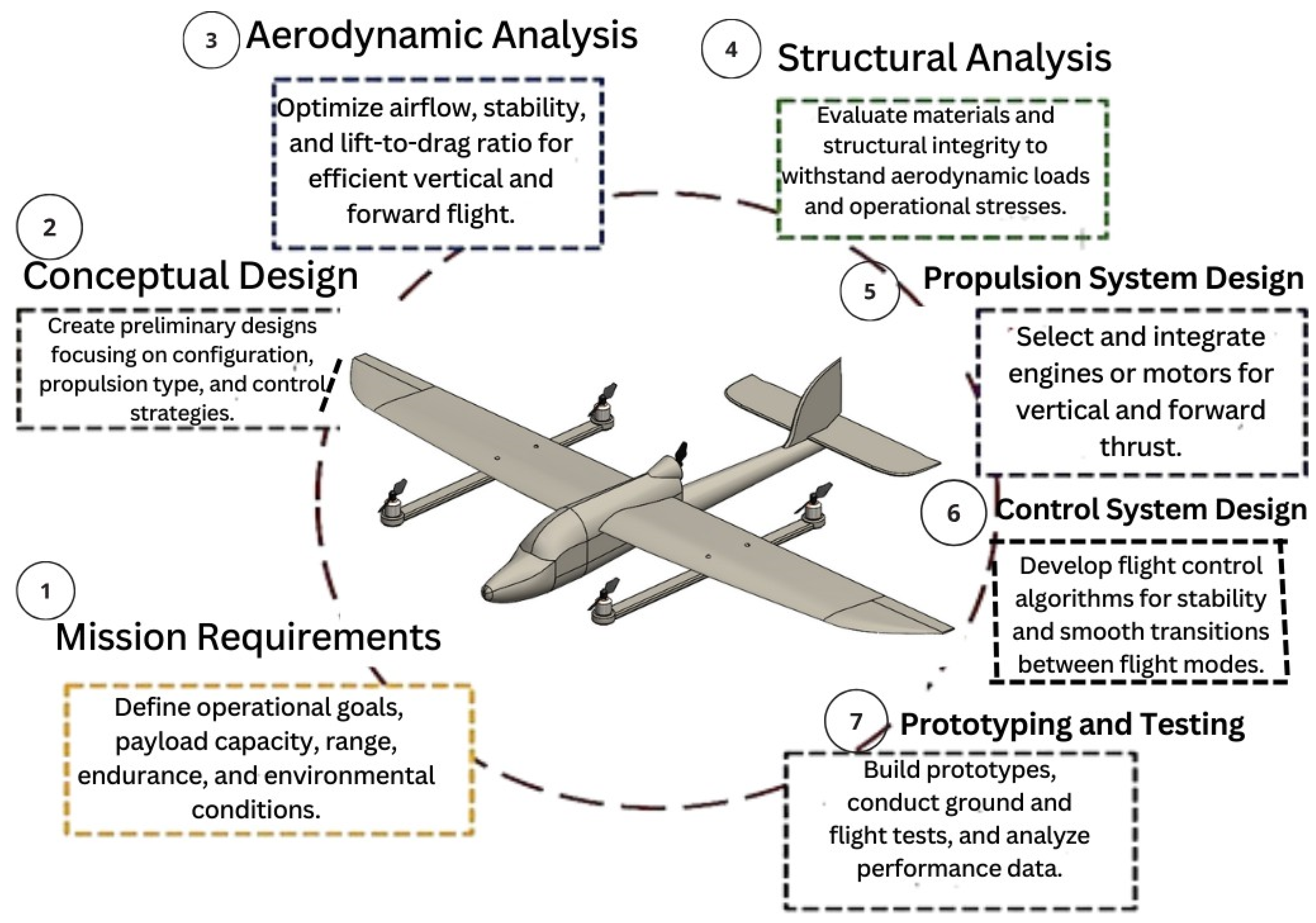

3. Design Methodologies and Aerodynamic Considerations

4. Propulsion Systems and Energy Management

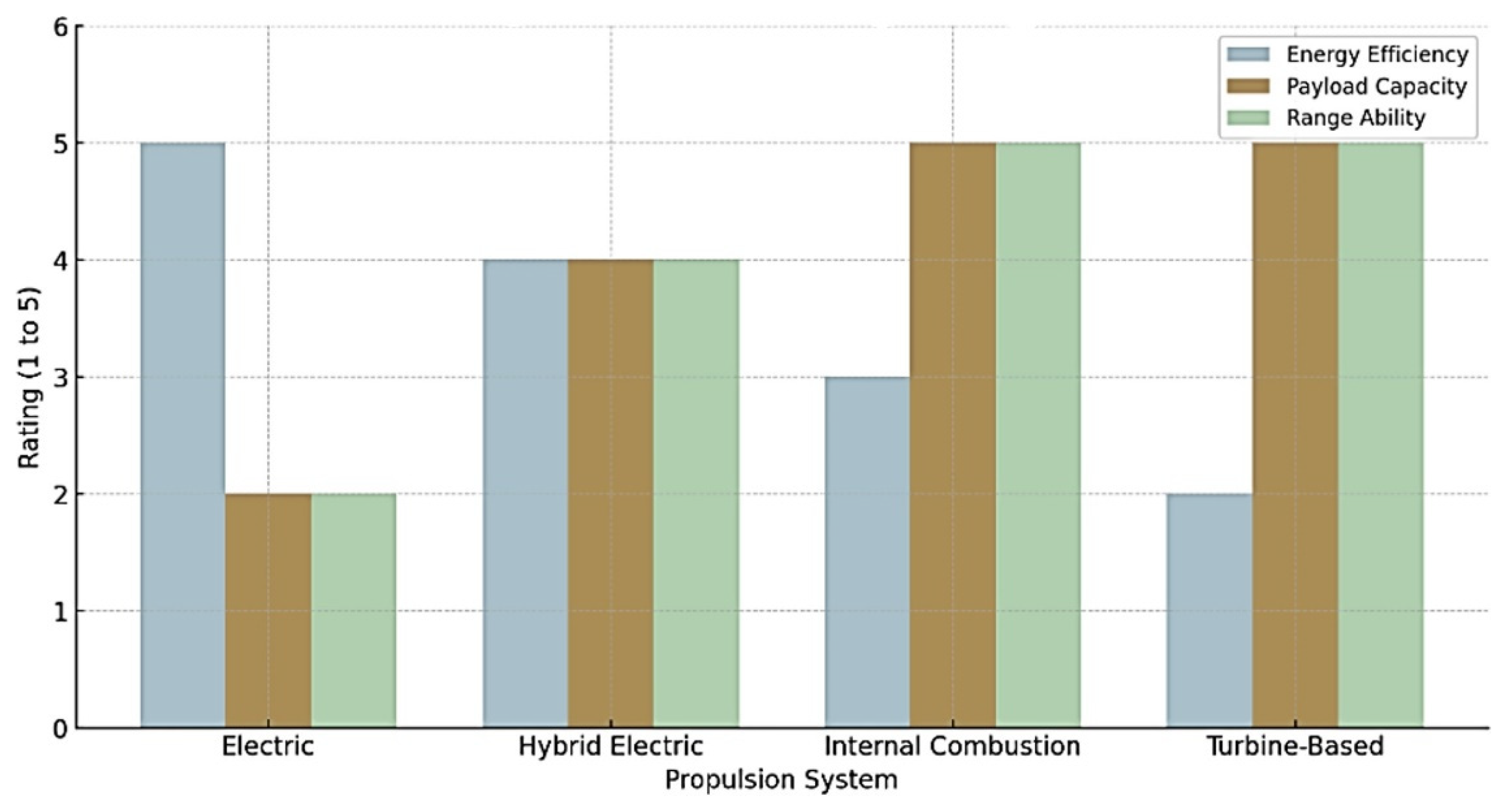

- Multi-rotor systems, where multiple rotors provide vertical lift and control.

- Lift + Cruise configurations, which use separate motors for vertical lift and forward cruise.

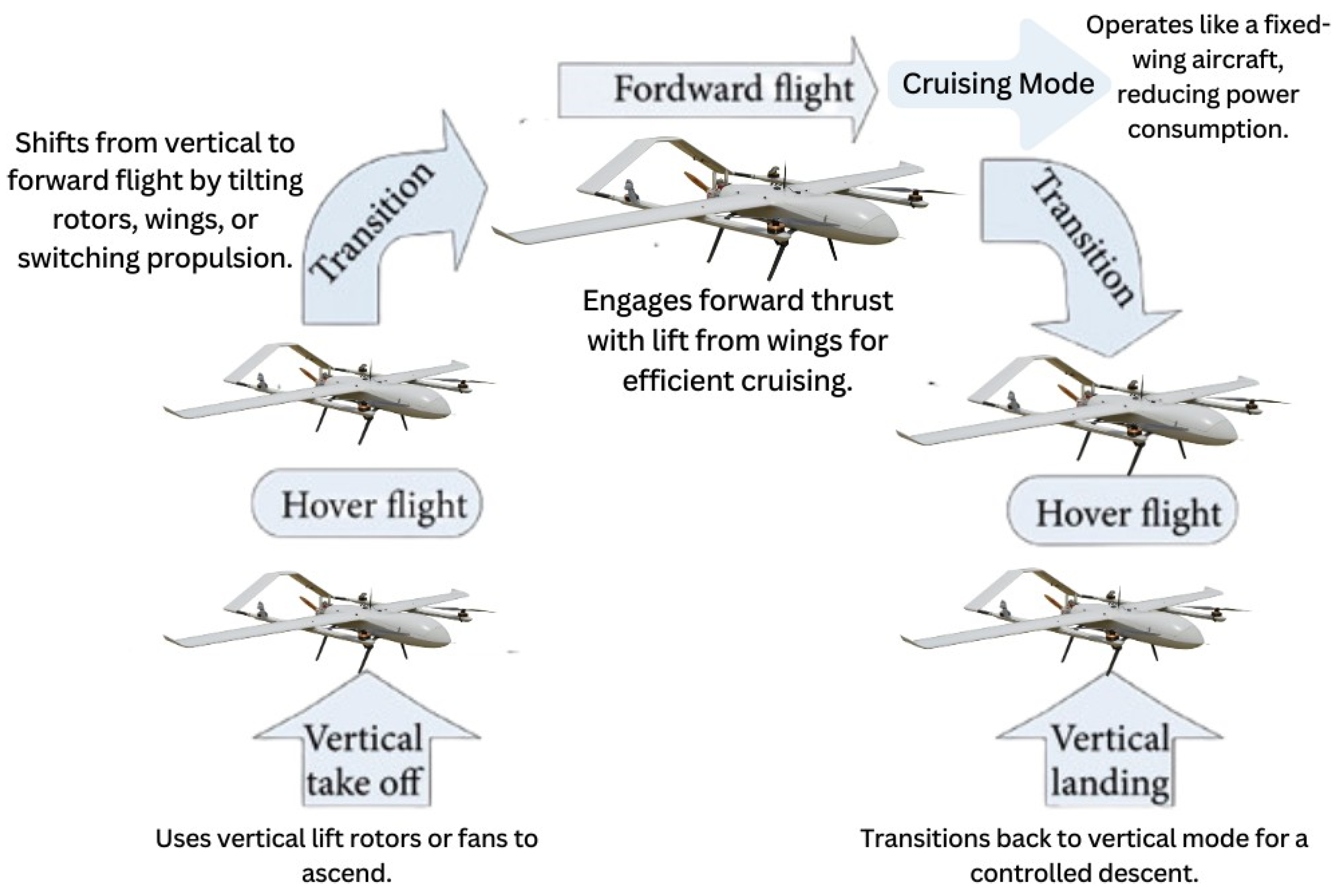

- Tilt-rotor and tilt-wing designs, where rotors or wings tilt to transition between vertical and horizontal flight.

- Improving battery materials and structures.

- Integrating batteries with the airframe to increase energy density.

- Designing sophisticated Battery Management Systems (BMS) to maintain stable operation.

- Developing advanced thermal management systems to ensure batteries operate within an ideal temperature range.[44]

- Exploring alternative technologies such as hydrogen fuel cells.

5. Flight Control Systems and Avionics

6. Applications of VTOL UAVs

7. Regulatory, Technological, and Societal Challenges in VTOL UAV Integration

8. Future Trends and Research Directions

9. Conclusion

Declaration of competing interest

Compliance with Ethics Requirements

References

- Valavanis, K.P.; Vachtsevanos, G.J. , Handbook of unmanned aerial vehicles, Springer Publishing Company, Incorporated, 2014.

- Misra, A.; Jayachandran, S.; Kenche, S.; Katoch, A.; Suresh, A.; Gundabattini, E.; Selvaraj, S.K.; Legesse, A.A. A Review on Vertical Take-Off and Landing (VTOL) Tilt-Rotor and Tilt Wing Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs). J. Eng. 2022, 2022, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudsi, Y.; Makaraci, M.; Kassem, A.; El-Bayoumi, G. A numerically-stable trajectory generation and optimization algorithm for autonomous quadrotor UAVs. Robot. Auton. Syst. 2023, 170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, Y.; Zhao, H.; Liu, Y. An evaluative review of the VTOL technologies for unmanned and manned aerial vehicles. Comput. Commun. 2020, 149, 356–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudsi, Y. , Synchronous task allocation and trajectory optimization for autonomous drone swarm, in: 2024 1st International Conference on Emerging Technologies for Dependable Internet of Things (ICETI), IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–8.

- Alqudsi, Y.; Makaraci, M. Exploring advancements and emerging trends in robotic swarm coordination and control of swarm flying robots: A review. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part C: J. Mech. Eng. Sci. 2024, 239, 180–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandivadekar, D.; Minisci, E. Modelling and Simulation of Transpiration Cooling Systems for Atmospheric Re-Entry. Aerospace 2020, 7, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Zhou, Z.; Liu, L.; Huang, J.; Lv, Z. Review of vertical take-off and landing fixed-wing UAV and its application prospect in precision agriculture. Int. J. Precis. Agric. Aviat. 2018, 1, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moradi, N.; Wang, C.; Mafakheri, F. Urban Air Mobility for Last-Mile Transportation: A Review. Vehicles 2024, 6, 1383–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ducard, G.J.; Allenspach, M. , Review of designs and flight control techniques of hybrid and convertible vtol uavs, Aerospace Science and Technology 2021, 118, 107035.

- Alqudsi, Y.; Makaraci, M. UAV swarms: research, challenges, and future directions. J. Eng. Appl. Sci. 2025, 72, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EASA, N. , Study on the societal acceptance of urban air mobility in europe, 2021.

- Alqudsi, Y.S.; Kassem, A.H.; El-Bayoumi, G.M. , Trajectory generation and optimization algorithm for autonomous aerial robots, in: 2021 1st International Conference on Emerging Smart Technologies and Applications (eSmarTA), IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–8.

- Shakhatreh, H.; Sawalmeh, A.H.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Dou, Z.; Almaita, E.; Khalil, I.; Othman, N.S.; Khreishah, A.; Guizani, M. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Survey on Civil Applications and Key Research Challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 48572–48634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aboelezz, A.; Elqudsi, Y.; Hassanalian, M.; Desoki, A. Wind tunnel calibration, corrections and experimental validation for fixed-wing micro air vehicles measurements. Aviation 2019, 23, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, S.; Zhou, P.; Duan, D.; Tang, J. Formation control of a second-order UAVs system under switching topology with obstacle/collision avoidance. Aerosp. Syst. 2020, 3, 219–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonami, K.; Kendoul, F.; Suzuki, S.; Wang, W.; Nakazawa, D. , Autonomous flying robots: unmanned aerial vehicles and micro aerial vehicles, Springer Science & Business Media, 2010.

- Floreano, D.; Wood, R.J. Science, technology and the future of small autonomous drones. Nature 2015, 521, 460–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendoul, F. Survey of advances in guidance, navigation, and control of unmanned rotorcraft systems. J. Field Robot. 2012, 29, 315–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebeck, R.H. Design of the Blended Wing Body Subsonic Transport. J. Aircr. 2004, 41, 10–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, A.S.; Younes, A.B.; Islam, S.; Dias, J.; Seneviratne, L.; Cai, G. , A review on the platform design, dynamic modeling and control of hybrid uavs, in: 2015 International Conference on Unmanned Aircraft Systems (ICUAS), IEEE, 2015, pp. 806–815.

- Pollet, F.; Delbecq, S.; Budinger, M.; Moschetta, J.-M.; Liscouët, J. , A common framework for the design optimization of fixed-wing, multicopter and vtol uav configurations, in: 33rd Congress of the International Council of the Aeronautical Sciences, 2022.

- Leishman, G.J. , Principles of helicopter aerodynamics with CD extra, Cambridge university press, 2006.

- Takahashi, T.; Fukudome, K.; Mamori, H.; Fukushima, N.; Yamamoto, M. Effect of Characteristic Phenomena and Temperature on Super-Cooled Large Droplet Icing on NACA0012 Airfoil and Axial Fan Blade. Aerospace 2020, 7, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cakir, H.; Kurtuluş, D.F. , Design and aerodynamic analysis of a vtol tilt-wing uav, Turkish Journal of Electrical Engineering and Computer Sciences 2022, 30, 767–784.

- Abdelrahman, A.M.K.M. , Conceptual design framework for transitional vtol aircraft with application to highly-maneuverable uavs (2019).

- Nakka, S.K.S.; Alexander-Ramos, M.J. Simultaneous Combined Optimal Design and Control Formulation for Aircraft Hybrid-Electric Propulsion Systems. J. Aircr. 2021, 58, 53–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- P. Ventura Diaz, S. Yoon, High-fidelity computational aerodynamics of multi-rotor unmanned aerial vehicles, in: 2018 AIAA Aerospace Sciences Meeting, 2018, p. 1266.

- Hua, M.-D.; Hamel, T.; Morin, P.; Samson, C. A Control Approach for Thrust-Propelled Underactuated Vehicles and its Application to VTOL Drones. IEEE Trans. Autom. Control. 2009, 54, 1837–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghamari, M.; Rangel, P.; Mehrubeoglu, M.; Tewolde, G.S.; Sherratt, R.S. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle Communications for Civil Applications: A Review. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 102492–102531. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bappy, A.; Asfak-Ur-Rafi, M.; Islam, M.S.; Sajjad, A.; Imran, K.N. , Design and development of unmanned aerial vehicle (Drone) for civil applications, Ph.D. thesis, BRAC University, 2015.

- Kenway, G.K.; Mader, C.A.; He, P.; Martins, J.R. Effective adjoint approaches for computational fluid dynamics. Prog. Aerosp. Sci. 2019, 110, 100542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palaia, G.; Vittorio, C.; Vincenzo, B.; Emanuele, R. , Preliminary design and testing of a vtol light uav based on a box-wing configuration, Aircraft Eng. Aerospace Tech 2019, 92, 737–742. [Google Scholar]

- Alqudsi, Y.S.; Kassem, A.H.; El-Bayoumi, G. A general real-time optimization framework for polynomial-based trajectory planning of autonomous flying robots. Proc. Inst. Mech. Eng. Part G: J. Aerosp. Eng. 2023, 237, 29–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viviani, A.; Iuspa, L.; Aprovitola, A. An optimization-based procedure for self-generation of Re-entry Vehicles shape. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2017, 68, 123–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tahir, N.M.; Alhaji, A.U.; Abdullahi, I.; Tahşr, N.; Alhaji, A.; Abdullahi, I. Performance evaluation of unmanned aerial vehicle wing made from sterculiasetigeradelile fiber and pterocarpuserinaceus wood dust epoxy composite using finite element method abaqus and structural testing. Res. Eng. Struct. Mater. 2022, 8, 675–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, J.; Zhu, B.; Hou, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhai, J. Evaluation and Comparison of Hybrid Wing VTOL UAV with Four Different Electric Propulsion Systems. Aerospace 2021, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finger, D.; Braun, C.; Bil, C. , The impact of electric propulsion on the performance of vtol uavs, 66. Deutscher Luft-Und Raumfahrtkongress DLRK 2017, 2017.

- An, B.; Sun, M.; Wang, Z.; Chen, J. Flame stabilization enhancement in a strut-based supersonic combustor by shock wave generators. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zong, J.; Zhu, B.; Hou, Z.; Yang, X.; Zhai, J. Evaluation and Comparison of Hybrid Wing VTOL UAV with Four Different Electric Propulsion Systems. Aerospace 2021, 8, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Z.; Wu, Z.; Xiong, J. Localized temperature rise as a novel indication in damage and failure behavior of biaxial non-crimp fabric reinforced polymer composite subjected to impulsive compression. Aerosp. Sci. Technol. 2020, 103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- T. VanderMey, J. VanderMey, Vertical take-off and landing (vtol) aircraft with distributed thrust and control, 2007. US Patent 7,159,817.

- Coutinho, M.; Bento, D.; Souza, A.; Cruz, R.; Afonso, F.; Lau, F.; Suleman, A.; Barbosa, F.R.; Gandolfi, R.; Junior, W.A. , et al. A review on the recent developments in thermal management systems for hybrid-electric aircraft. Appl. Therm. Eng. [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Ebinuma, T.; Nakasuka, S. ; Correction: Tanaka, et al. dual-satellite lunar global navigation system using multi-epoch double- differenced pseudorange observations. aerospace 2020, 7, 122, Aerospace 2020, 8, 8. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, S.; Zhang, G.; Zhou, M.; Li, G. A Comprehensive Review of Research Hotspots on Battery Management Systems for UAVs. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 84636–84650. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Liu, M. Path Planning of Electric VTOL UAV Considering Minimum Energy Consumption in Urban Areas. Sustainability 2022, 14, 13421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, L.; Huangfu, Y.; Ma, R.; Xie, R.; Song, Z.; Zhao, D.; Yang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Xu, L. A Comprehensive Review on Fuel Cell UAV Key Technologies: Propulsion System, Management Strategy, and Design Procedure. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrification 2022, 8, 4118–4139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudsi, Y.; Makaraci, M. , Swarm robotics for autonomous aerial robots: Features, algorithms, control techniques, and challenges, in: 2024 4th International Conference on Emerging Smart Technologies and Applications (eSmarTA), IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–9.

- Su, S.; Yu, P.; Wang, H.; Shan, X. Design and Optimization of a Piecewise Flight Controller for VTOL UAVs. J. Aircr. 2024, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crespo, L.; Matsutani, M.; Annaswamy, A. , Verification and tuning of an adaptive controller for an unmanned air vehicle, in: AIAA Guidance, Navigation, and Control Conference, 2010, p. 8403.

- Alqudsi, Y.S.; Saleh, R.A.A.; Makaraci, M.; Ertunç, H.M. Enhancing aerial robots performance through robust hybrid control and metaheuristic optimization of controller parameters. Neural Comput. Appl. 2024, 36, 413–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vachtsevanos, G.; Tang, L.; Drozeski, G.; Gutierrez, L. From mission planning to flight control of unmanned aerial vehicles: Strategies and implementation tools. Annu. Rev. Control. 2005, 29, 101–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, O.; Kazim, M.; Iqbal, J. Robust Position Control of VTOL UAVs Using a Linear Quadratic Rate-Varying Integral Tracker: Design and Validation. Drones 2025, 9, 73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudsi, Y. , Analysis and implementation of motion planning algorithms for real-time navigation of aerial robots in dynamic environments, in: 2024 4th International Conference on Emerging Smart Technologies and Applications (eSmarTA), IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–10.

- Zhou, Q.; Tan, F. Avionics of Electric Vertical Take-off and Landing in the Urban Air Mobility: A Review. IEEE Aerosp. Electron. Syst. Mag. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Alqudsi, Y. , Coordinated formation control for swarm flying robots, in: 2024 1st International Conference on Emerging Technologies for Dependable Internet of Things (ICETI), IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–8.

- Ramasamy, S.; Sabatini, R. ; Communication, navigation and surveillance performance criteria for safety-critical avionic systems, Technical Report, SAE Technical Paper, 2015.

- Chakraborty, I.; Comer, A.M.; Bhandari, R.; Mishra, A.A.; Schaller, R.; Sizoo, D.; McGuire, R. , Flight simulation based assessment of simplified vehicle operations for urban air mobility, in: AIAA SCITECH 2023 Forum, 2023, p. 0400.

- Chakraborty, I.; Comer, A.; Bhandari, R.; Putra, S.H.; Mishra, A.A.; Schaller, R.; Sizoo, D.; McGuire, R. Piloted Simulation-Based Assessment of Simplified Vehicle Operations for Urban Air Mobility. J. Aerosp. Inf. Syst. 2024, 21, 392–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudsi, Y. , Advanced control techniques for high maneuverability trajectory tracking in autonomous aerial robots, in: 2024 1st International Conference on Emerging Technologies for Dependable Internet of Things (ICETI), IEEE, 2024, pp. 1–8.

- Alqudsi, Y.; Bolat, F.C.; Makaraci, M. Optimal and robust control methodologies for 4DOF active suspension systems: A comparative study with uncertainty considerations. Optim. Control. Appl. Methods 2024, 46, 3–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaludin, Z.; Gires, E. , Automatic flight control requirements for transition flight phases when converting long endurance fixed wing uav to vtol aircraft, in: 2019 IEEE international conference on automatic control and intelligent Systems (I2CACIS), IEEE, 2019, pp. 273–278.

- Shakhatreh, H.; Sawalmeh, A.H.; Al-Fuqaha, A.; Dou, Z.; Almaita, E.; Khalil, I.; Othman, N.S.; Khreishah, A.; Guizani, M. Unmanned Aerial Vehicles (UAVs): A Survey on Civil Applications and Key Research Challenges. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 48572–48634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sonkar, S.; Kumar, P.; Philip, D.; Ghosh, A. , Low-cost smart surveillance and reconnaissance using vtol fixed wing uav, in: 2020 IEEE Aerospace conference, IEEE, 2020, pp. 1–7.

- Alqudsi, Y.S.; Alsharafi, A.S.; Mohamed, A. , A review of airborne landmine detection technologies: Unmanned aerial vehicle-based approach, in: 2021 International congress of advanced technology and engineering (ICOTEN), IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–5.

- Woodbridge, E.; Connor, D.T.; Verbelen, Y.; Hine, D.; Richardson, T.; Scott, T.B. Airborne gamma-ray mapping using fixed-wing vertical take-off and landing (VTOL) uncrewed aerial vehicles. Front. Robot. AI 2023, 10, 1137763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Watts, A.C.; Ambrosia, V.G.; Hinkley, E.A. Unmanned Aircraft Systems in Remote Sensing and Scientific Research: Classification and Considerations of Use. Remote Sens. 2012, 4, 1671–1692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aggarwal, S.; Nigam, K.; Singh, V.; Mishra, T.; Pandey, A.K.; Kant, R.; Murhekar, M. Drone-based medical delivery in the extreme conditions of Himalayan region: a feasibility study. BMJ Public Heal. 2024, 2, e000894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puri, A.; Valavanis, K.; Kontitsis, M. , Statistical profile generation for traffic monitoring using real-time uav based video data, in: 2007 Mediterranean Conference on Control & Automation, IEEE, 2007, pp. 1–6.

- Ahmed, S.S.; Fountas, G.; Lurkin, V.; Anastasopoulos, P.C.; Zhang, Y.; Bierlaire, M.; Mannering, F. The State of Urban Air Mobility Research: An Assessment of Challenges and Opportunities. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 26, 1375–1394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finn, R.L.; Wright, D. ; Unmanned aircraft systems: Surveillance, ethics and privacy in civil applications, Computer Law & Security Review 2012, 28, 184–194.

- Hatfield, M.; Cahill, C.; Webley, P.; Garron, J.; Beltran, R. Integration of Unmanned Aircraft Systems into the National Airspace System-Efforts by the University of Alaska to Support the FAA/NASA UAS Traffic Management Program. Remote. Sens. 2020, 12, 3112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, A.P.; Shaheen, S.A.; Farrar, E.M. Urban Air Mobility: History, Ecosystem, Market Potential, and Challenges. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 6074–6087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Straubinger, A.; Rothfeld, R.; Shamiyeh, M.; Büchter, K.-D.; Kaiser, J.; Plötner, K.O. An overview of current research and developments in urban air mobility – Setting the scene for UAM introduction. J. Air Transp. Manag. 2020, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takacs, A.; Haidegger, T. Infrastructural Requirements and Regulatory Challenges of a Sustainable Urban Air Mobility Ecosystem. Buildings 2022, 12, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cummings, M.L.; Bruni, S. ; Collaborative human–automation decision making, Springer handbook of automation (2009) 437–447.

- Yedavalli, P.; Mooberry, J. , An assessment of public perception of urban air mobility (uam), Airbus UTM: Defining Future Skies (2019) 2046738072–1580045281.

- Park, G.; Park, H.; Park, H.; Chun, N.; Kim, S.-H.; Lee, K. , Public perception of uam: Are we ready for the new mobility that we have dreamed of?, in: Proceedings of the Human Factors and Ergonomics Society Annual Meeting, volume 66, SAGE Publications Sage CA: Los Angeles, CA, 2022, pp. 40–44.

- Bridgelall, R. Aircraft Innovation Trends Enabling Advanced Air Mobility. Inventions 2024, 9, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rothfeld, R.; Balac, M.; Ploetner, K.O.; Antoniou, C. , Initial analysis of urban air mobility’s transport performance in sioux falls, in: 2018 Aviation Technology, Integration, and Operations Conference, 2018, p. 2886.

- Abdelmaksoud, S.I.; Mailah, M.; Abdallah, A.M. Control Strategies and Novel Techniques for Autonomous Rotorcraft Unmanned Aerial Vehicles: A Review. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 195142–195169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiang, S.; Xie, A.; Ye, M.; Yan, X.; Han, X.; Niu, H.; Li, Q.; Huang, H. Autonomous eVTOL: A summary of researches and challenges. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2023, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuchardt, B.I.; Geister, D.; Lüken, T.; Knabe, F.; Metz, I.C.; Peinecke, N.; Schweiger, K. Air Traffic Management as a Vital Part of Urban Air Mobility—A Review of DLR’s Research Work from 1995 to 2022. Aerospace 2023, 10, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pak, H.; Asmer, L.; Kokus, P.; Schuchardt, B.I.; End, A.; Meller, F.; Schweiger, K.; Torens, C.; Barzantny, C.; Becker, D.; et al. Can Urban Air Mobility become reality? Opportunities and challenges of UAM as innovative mode of transport and DLR contribution to ongoing research. CEAS Aeronaut. J. 2024, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudsi, Y. Integrated Optimization of Simultaneous Target Assignment and Path Planning for Aerial Robot Swarm. J. Supercomput. 2024, 81, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vascik, P.D.; Hansman, R.J. , Scaling constraints for urban air mobility operations: Air traffic control, ground infrastructure, and noise, in: 2018 aviation technology, integration, and operations conference, 2018, p. 3849.

- Jenab, K.; Moslehpour, S.; Khoury, S.; Virtual maintenance; reality; systems: A review, International Journal of Electrical and Computer Engineering 2016, 6, 2698.

- Johnson, W.; Silva, C.; Solis, E. , Concept vehicles for vtol air taxi operations, in: AHS Specialists”Conference on Aeromechanics Design for Transformative Vertical Flight, ARC-E-DAA-TN50731, 2018.

| Configuration Type |

Description | Advantages | Disadvantages | Typical Applications |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Fixed-Wing VTOL |

Fixed wing with addi- tional VTOL mecha- nism |

Combines long range, speed of fixed wing withVTOL |

Increased design complex- ity, additional weight |

Long-range surveillance, mapping, and delivery |

| Multi-rotor VTOL |

Multiple rotors for ver- tical lift |

Excellent maneu- verability, hovering capability, simpledesign |

Limited speed, range, and endurance. Higher energy consumption |

Aerial photography, inspection, short- range surveillance |

| Tilt- rotor/Tilt- wing VTOL |

Rotors or wings that can tilt between verti- cal and horizontal po- sitions for VTOL and forward flight respec-tively |

Combines VTOL and efficient for- ward flight |

Increased mechanical complexity, more complex control systems |

Medium to long-range missions, urban air mobility |

| Blended Wing Body VTOL |

Integrated wing and fuselage with VTOL capability |

Enhanced aerodynamics, reduced drag, larger internal volume |

More complex design and analysis, especially con- cerning the integration of the VTOL mechanism |

Surveillance, high- payload transport |

| Hybrid VTOL | Combination of dif- ferent configurations, e.g., fixed wing with vertical rotors |

Combines advan- tages of different configurations |

Increased complexity, weight, and cost |

Versatile applications, such as surveillance, and remote area oper- ations |

| Design Aspect | Key Considerations | Methods and Tools |

|---|---|---|

| Mission Requirements | Range, payload, endurance, opera- tional environment. |

Mission planning, parameter specifi- cation [34] |

| Thrust Performance | Thrust for take-off, hover, cruise. Mo- tor and propeller selection, and thrust calculations in different modes. |

Thrust tests, motor data sheets, aero- dynamic equations |

| Stability | Center of gravity, symmetrical place- ment of components, moment analy- sis. |

Careful component placement |

| Aerodynamics | Lift, drag, stability. Wing design (as- pect ratio, sweep, taper), aerofoil se- lection, drag calculations |

Computational Fluid Dynamics (CFD), wind tunnel testing |

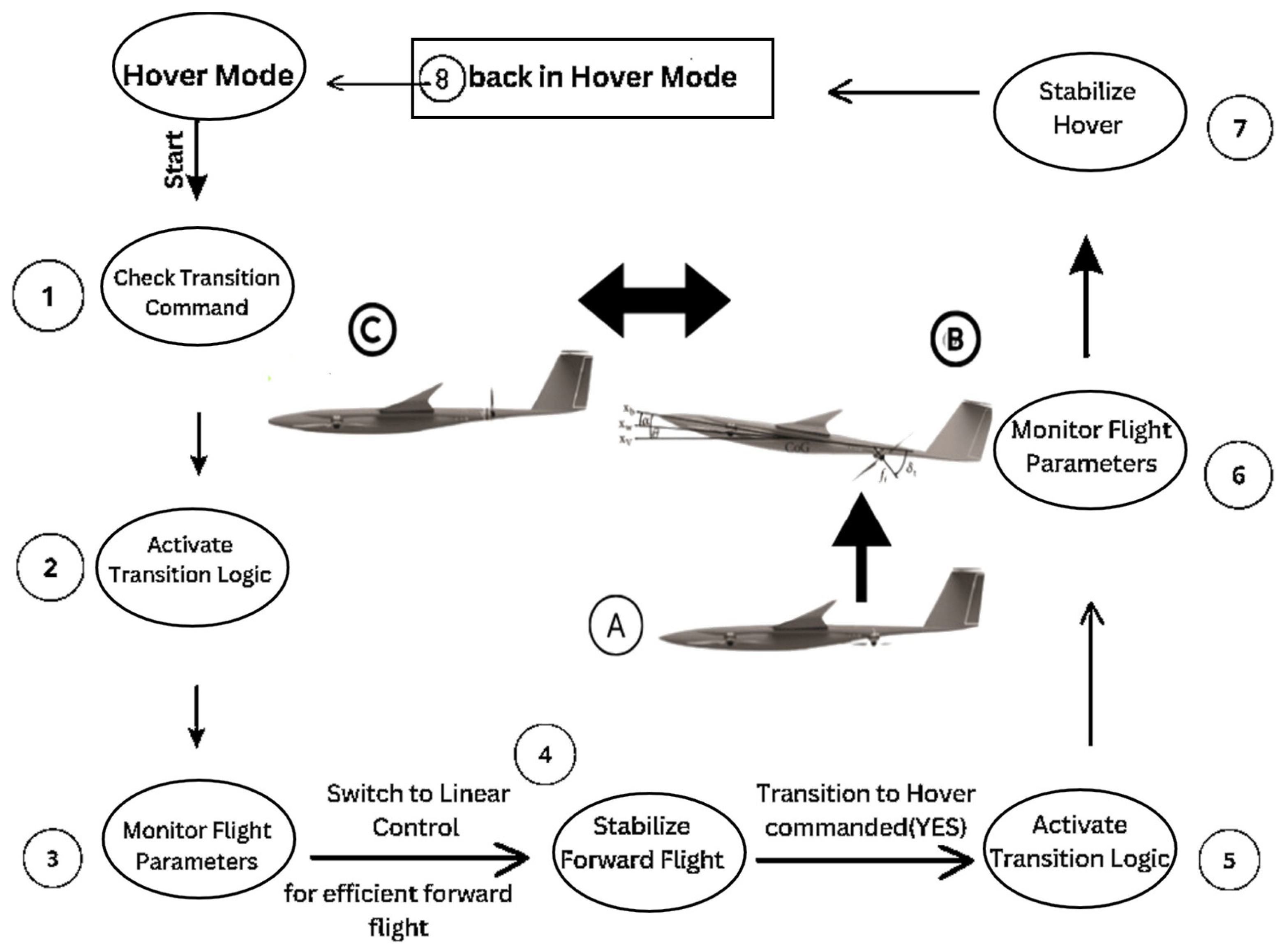

| Transition | Control strategies for smooth tran- sition between VTOL and forward flight modes. |

PID control, neural network-based nonlinear PID control, sensor fusion and control algorithms |

| Structural Analysis | Material selection for lightweight and strength, component sizing, and placement. |

Finite element analysis (FEA), 3D modeling software (e.g., SolidWorks, CATIA) |

| Wing Loading | Impact of weight on thrust perfor- mance. |

Performance analysis using simula- tion software |

| Aspect | Key Technologies and Considerations |

|---|---|

| Propulsion Systems | Electric motors (brushless DC), gas-driven fans, hybrid systems, various configurations (multi-rotor, lift + cruise, tilt-rotor, tilt-wing, DEP). |

| Motor Selection | RPM vs supply voltage, durability, thermal management, weight. |

| Battery Technology | Lithium-ion and Li-Polymer, energy density, power density, safety, battery management systems (BMS), thermal management, alternative technolo- gies (hydrogen fuel cells). |

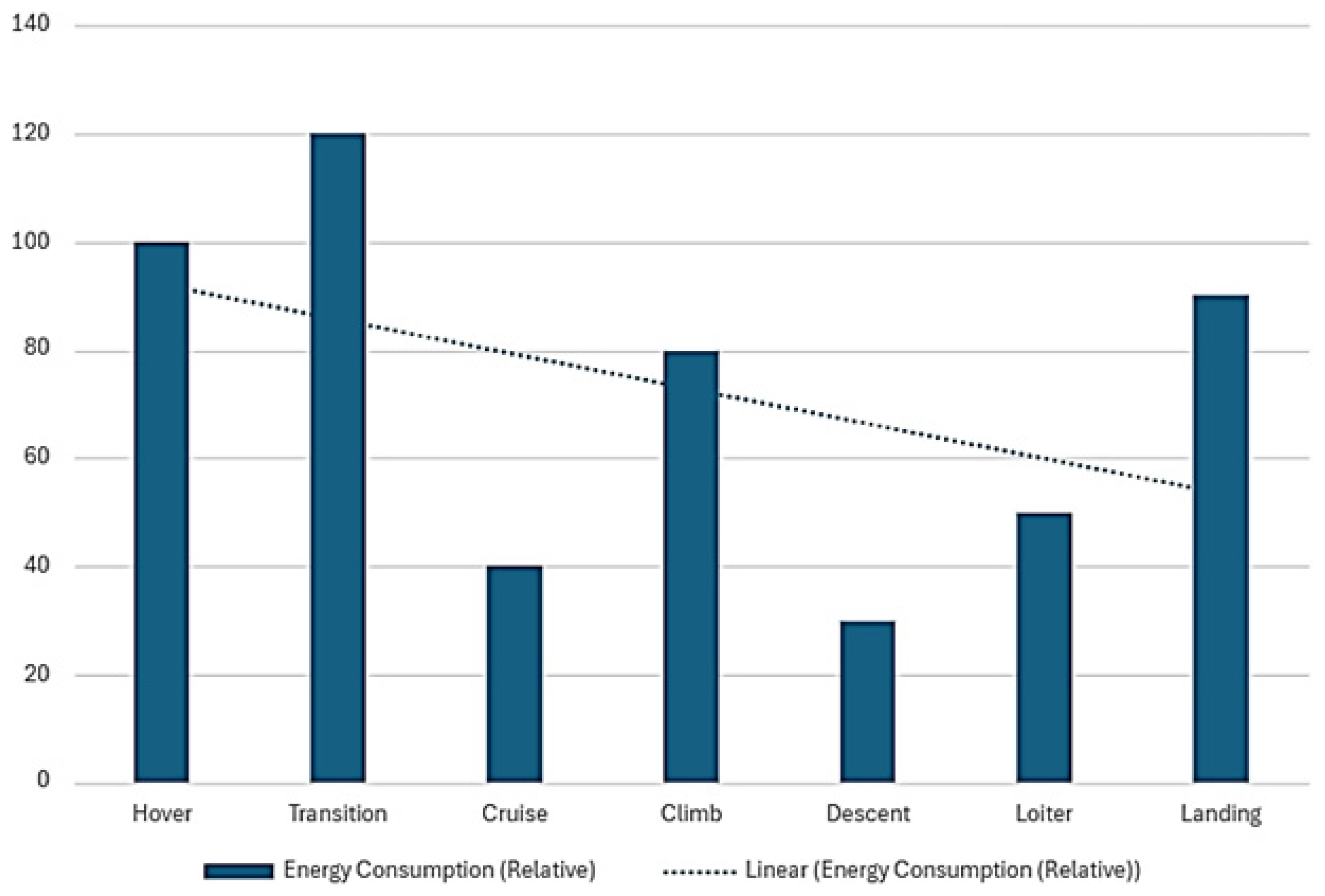

| Energy Consumption | Higher during vertical take-off and hover, efficient management for transition, optimization of propulsion system for minimal losses. |

| Component Efficiency | ESCs, motors, propellers. |

| Aspect | Key Technologies and Considerations |

|---|---|

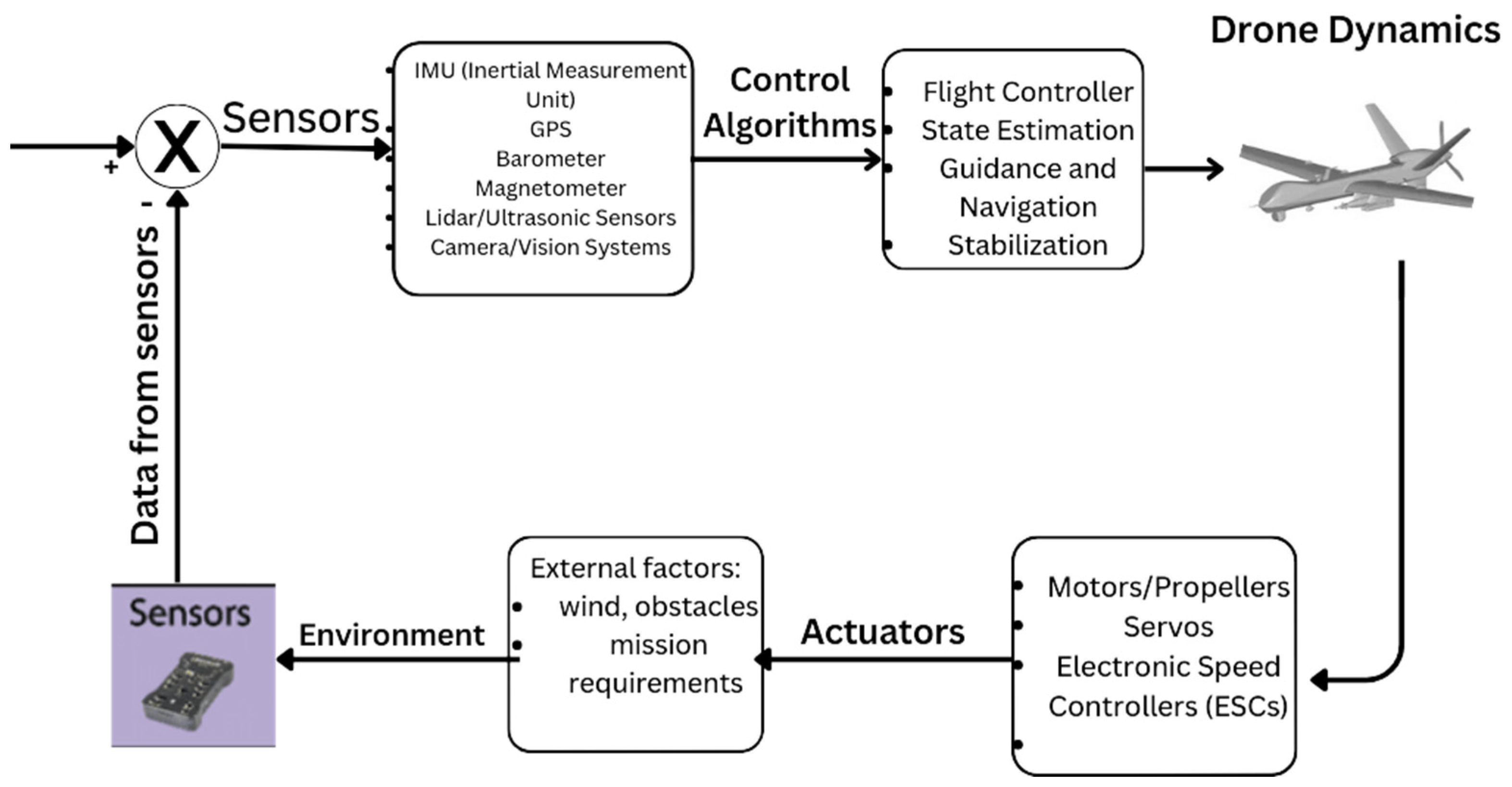

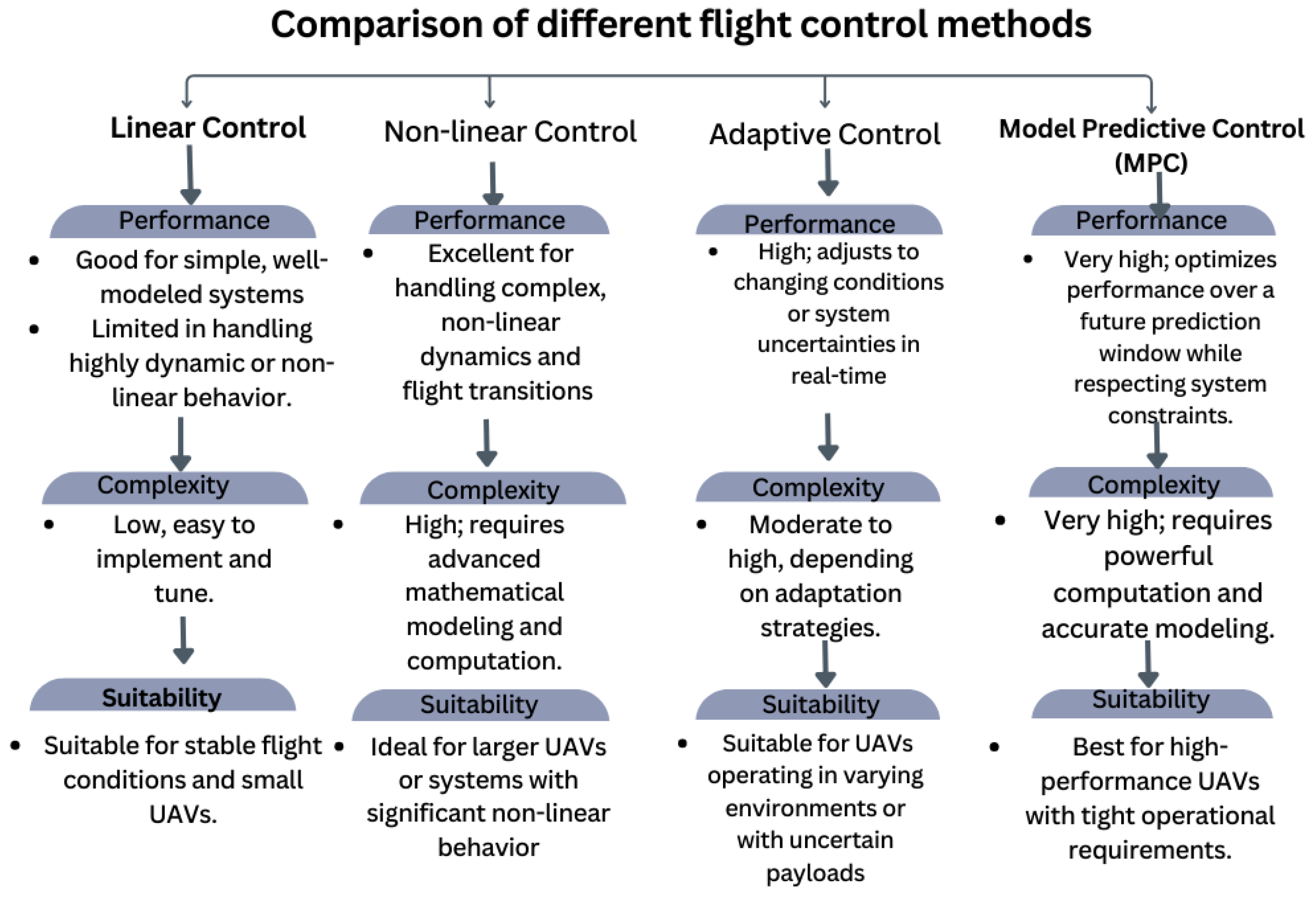

| Flight Control Models | Linear and non-linear models, PID control, LQR controllers, robust control methods [60,61]. |

| Control Laws | Algorithms based on hybrid UAV dynamics, real-time adjustments of control gains, control allocation. |

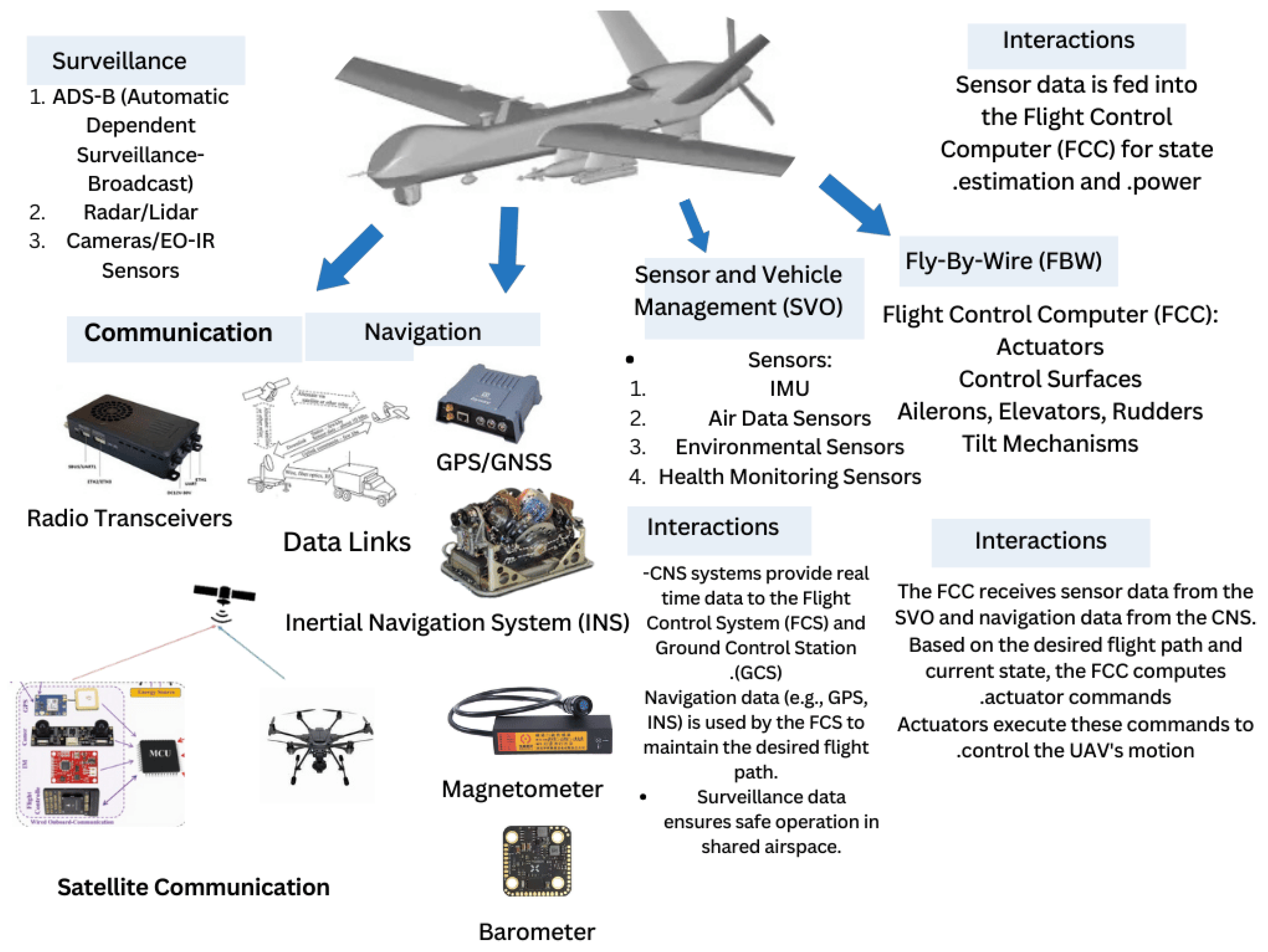

| Avionics | CNS (Communication, Navigation, Surveillance), SVO, FBW, FCC, IMU, Radar Altimeters, V2V, V2G communications. |

| CNS Systems | Air traffic control communication, navigation systems (GNSS, INS, ADS), collision avoidance. |

| SVO & FBW | Automated flight systems, user-friendly interfaces, electronic control of flight surfaces, reduced pilot workload, enhanced control precision, inte- gration with digital systems. |

| Transition Management | Automatic flight control during transition phases, regulation of rotor speeds and engine throttle, altitude and airspeed sensors. |

| Sector | Applications |

|---|---|

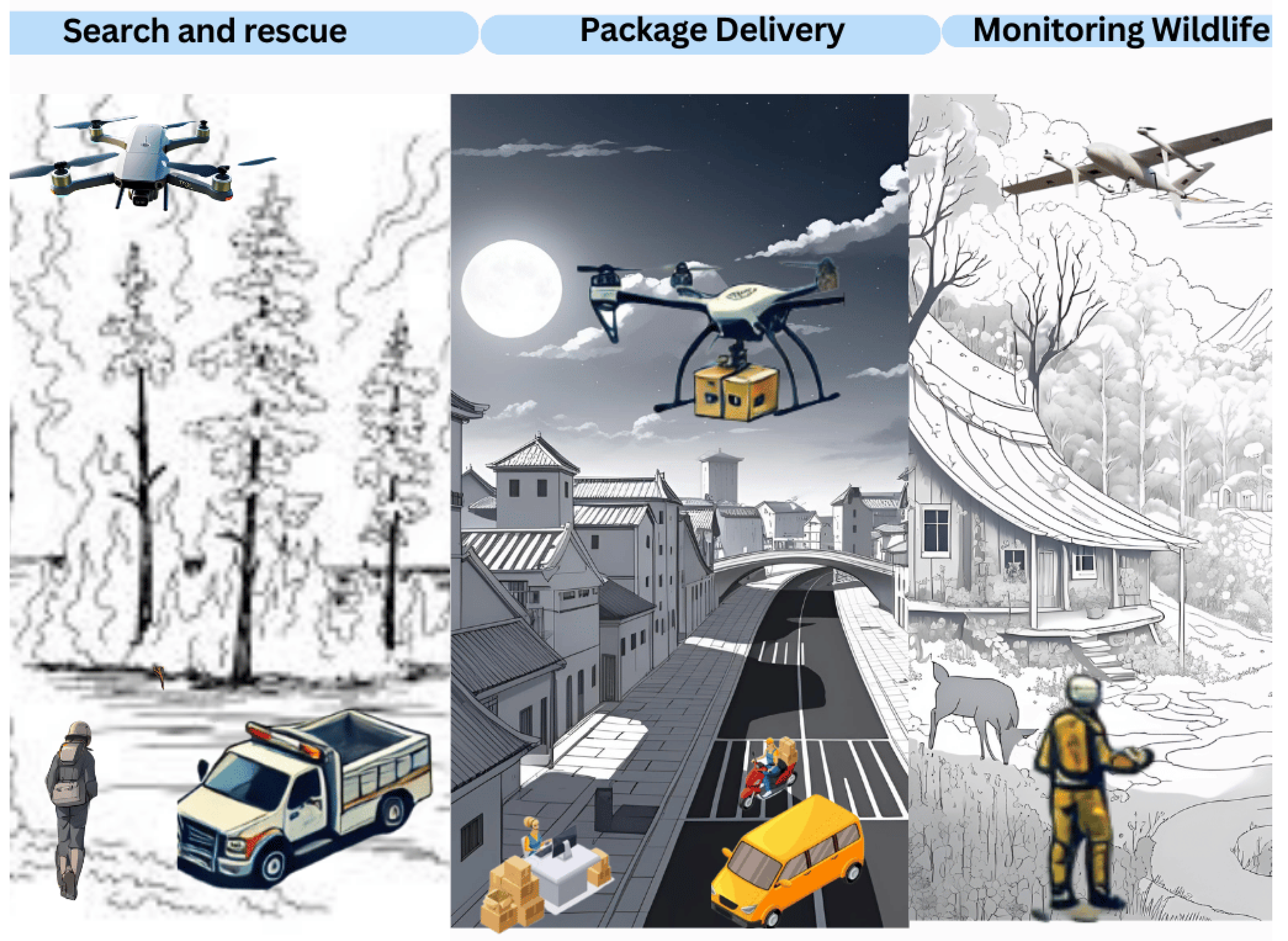

| Surveillance | Wildlife monitoring, oil pipeline monitoring, infrastructure inspection, traffic monitoring, intruder detection. |

| Military | Intelligence, surveillance, and reconnaissance (ISR), search and rescue operations, operations in difficult terrains. |

| Agriculture | Crop monitoring and analysis, precision agriculture. |

| Logistics & Delivery | Transportation of goods, medical supplies, package delivery in urban and remote areas. |

| Construction | Mapping and monitoring construction sites. |

| Emergency Response | Disaster relief, damage assessment, delivery of aid and supplies. |

| Urban Air Mobility | Air taxis, urban commuting, point-to-point transportation in cities. |

| Media & Entertainment | Aerial photography and videography, filmmaking. |

| Challenge | Description |

|---|---|

| Lack of Comprehensive Regulations | Absence of clear guidelines for VTOL aircraft certification, operations, airspace management, and infrastructure requirements. |

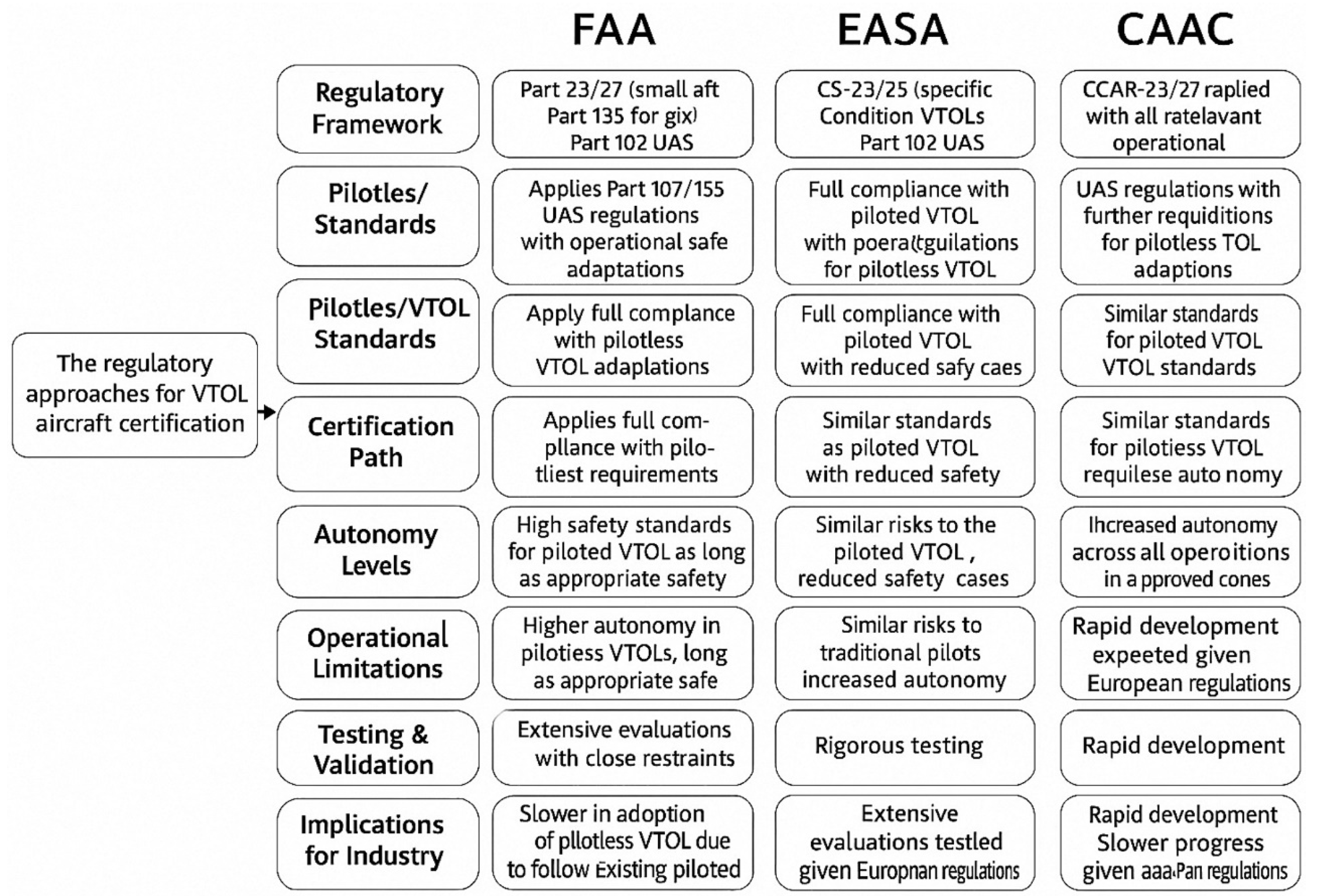

| Evolving Certification Standards | Need for new airworthiness regulations for eVTOL aircraft, with the FAA and EASA developing specific standards. |

| Integration of Autonomous Technol- ogy |

Regulatory caution regarding fully autonomous operations and concerns about trustworthiness, certification complexity, interpretability limitations, and algorithm constraints. |

| Societal Acceptance | Public concerns about safety, noise, and privacy, and the need to address these issues to gain public trust. |

| Urban Integration | Challenges of integrating VTOL aircraft into existing transportation sys- tems and urban infrastructure while mitigating environmental disruptions and ensuring passenger comfort. |

| Trend/Direction | Description |

|---|---|

| Autonomous Operation | Development of sophisticated flight control systems, advanced sensors, and AI-driven decision-making to enable fully autonomous flight. |

| Air Traffic Management Integration | Development of automated routing and communication systems to inte- grate VTOLs into existing airspace, including UTM for real-time tracking and surveillance. |

| Urban Infrastructure Development | Creation of designated vertiports in urban areas, integration with public transportation networks, and development of specialised air traffic control systems. |

| Advanced HMI | Integration of voice and gesture recognition, AR/VR interfaces, and other user-friendly technologies to enhance the pilot and passenger experience. |

| Technical Improvements | Advancements in electric propulsion systems, battery technology, lightweight materials, and aerodynamic designs to improve energy effi- ciency, stability, and overall performance of VTOL aircraft. |

| Safety and Reliability | Focus on the development of high-reliability components and robust fault-tolerant control systems with advanced diagnostic and monitoring capabilities. |

| Regulatory Framework | Work towards a comprehensive set of guidelines that address vehicle certi- fication, operational procedures, safety standards, and security protocols. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).