1. Introduction

Frequency photoacoustics (PA) of semiconductors and semiconductor devices has been developing for over four decades, with the goal of enabling non-destructive characterization of optical, thermal, elastic, and electronic properties essential for the design of various microelectronic, photonic, sensor, and biosensor devices, as well as solar cells and thermal management of VLSI circuits [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

6,

7,

8,

9,

10,

11]. Previous studies have demonstrated that frequency-domain PA spectroscopy [

12] can be used to measure various physical properties of semiconductors. However, these methods are not suitable for real-time measurements, which are crucial for many industrial and biomedical applications [

13]. On the other hand, the development of time-domain PA methods [

14,

15,

16,

17] provides this capability but requires advancements in time-resolved models and signal processing techniques based on them [

16]. In this paper, we focus on developing a model of the PA signal for time-domain photoacoustics of semiconductors, utilizing insights gained from the development of frequency-domain photoacoustics.

There are three different approaches to modeling the photothermal and photoacoustic effects in semiconductors. The first approach is based on the assumption that photogenerated carriers influence the thermal conductivity, diffusivity and/or thermal relaxation time of a semiconductor sample exposed to electromagnetic radiation [

18,

19,

20,

21], and through these properties, they affect the temperature distribution within the sample, consequently impacting the thermoelastic bending of the sample and pressure fluctuations in the surrounding gaseous medium. The second approach relies on the two-temperature model of the interaction between the excitation optical beam and the semiconductor sample [

22,

23,

24,

25] and can be particularly suitable for highly doped, degenerate semiconductor samples. The third approach, which will be used in this study, assumes that two types of heat sources emerge within a semiconductor upon illumination [

12,

26,

27,

28]. The first type is characteristic of all solid-state materials and can be referred to as fast heat sources. These sources arise due to the interaction of the excitation electromagnetic radiation with lattice vibrations and non-radiative de-excitation relaxation processes, which convert the absorbed electromagnetic energy into heat. Since non-radiative de-excitation relaxation processes occur over extremely short timescales—much shorter than those relevant for observing photothermal effects—the time dependence of these heat sources can be considered to follow the time dependence of the excitation optical irradiance. However, due to the band structure of semiconductors, which includes a partially filled valence band, a partially empty conduction band, and a bandgap in between, the interaction of excitation photons with charge carriers leads to the photogeneration of quasi-free charge carriers if the photon energy exceeds the semiconductor’s bandgap width [

29]. When an electron is excited from the valence band, it leaves behind a positively charged vacancy, known as a hole. Electron-hole pairs, bound by Coulomb interaction, diffuse through the semiconductor due to the established concentration gradient and recombine after a characteristic period known as the carrier lifetime. During recombination, they transfer their kinetic energy to the crystal lattice, forming so-called slow heat sources at the recombination sites within the semiconductor [

12]. The resulting temperature distribution in the illuminated semiconductor can be described as a superposition of temperature variations originating from both slow and fast heat sources. From a physical perspective, this approach is particularly suitable for narrow-bandgap semiconductors that are moderately doped, ensuring that the Fermi level remains within the bandgap. From the perspective of photoacoustic research and its applications in semiconductor and semiconductor device characterization, this approach is the most appropriate because it describes the relationship between photogenerated plasma, the electronic properties of semiconductors, optical heating of the sample, and the measurable photoacoustic signal [

12,

26,

27,

28].

In this study, we investigate how photo-induced quasi-free carriers affect surface temperature variations in a thin, moderately doped semiconductor sample when illuminated by square optical pulses. To analyze these effects, we use some of the parameters introduced in our previous papers [

16,

30] on time-resolved PA signals: rise time, fall time, settling time, and the stationary value of the signal. These parameters, commonly used in system dynamics, automatic control, and signal transmission and processing (telecommunications), help establish a connection between the time-dependent signal and the parameters of the system through which the signal propagates.

The structure of the paper is as follows. After this introduction,

Section 2 derives a model of photothermally induced temperature changes at the non-illuminated surface of a thin semiconductor sample, generated by fast and slow thermal sources, using the Laplace transform method and electro-thermal analogy. In

Section 3, we analyze the influence of sample thickness, surface recombination velocities and electronic properties on the time-domain PA response for a thermally thin semiconductor sample. Finally, the key conclusions are summarized in

Section 4.

2. Photoinduced heat transfer across thin semiconductor: Theoretical model

The model of photoinduced heat propagation is derived under the following assumptions:

The sample is excited by an optical pulse of irradiance I(t) [W/m

2], where f(t) describes the time dependence of the incident irradiance:

With h(t) is denoted the Heaviside step function and with T [s] the pulse duration

Before the excitation of optical radiation, the whole structure and its environment were at the same temperature – Тamb [K].

The deexcitation-relaxation processes due to photon-phonon interactions are assumed to be much faster than the rate of change of the rising edge of the optical pulse. Thus, the heat sources formed by these processes follow the temporal shape of the optical pulse [

31].

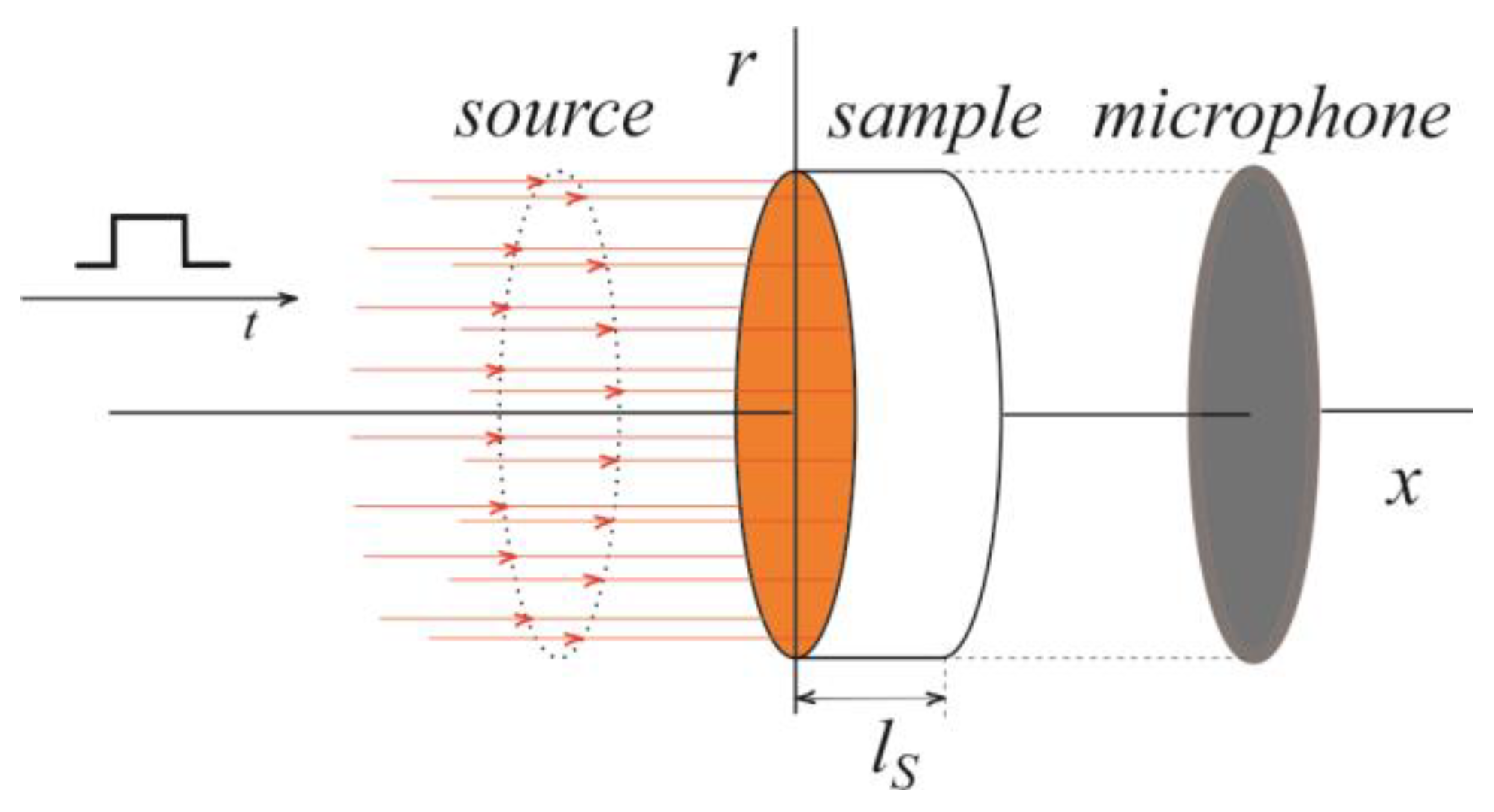

We consider a semiconductor disk uniformly illuminated across its cross-sectional surface normal to the direction of light propagation (

Figure 1), allowing the entire problem of optically generated heat propagation to be analyzed using a one-dimensional approximation [

32].

It is assumed that the surrounding gas does not absorb the incident radiation. Heat sources are generated solely within the sample; however, the resulting thermal disturbance affects the surrounding area.

The sample is considered optically opaque, i.e.

where

is the optical absorption coefficient [1/m] and

ls [m] is the sample thickness. Thus, the excitation optical beam penetrates only a thin layer of the semiconductor near its illuminated surface. The optically generated heat due to photon-phonon interactions can be described as a surface heat source [

32,

33]:

where R is the sample’s reflectance and δ is the Dirac delta function.

The contribution of volume recombinations of semiconducting sample is neglected, and heat sources caused by surface recombination can be described by [

12,

26,

27,

28]:

where

,

,

,

, and

are parameters describing the surface recombination velocity at the illuminated (

g) and non-illuminated (

b) surfaces of the semiconductor sample, the concentration of photoinduced minority carriers at the sample surfaces, and the energy gap of the semiconductor, respectively.

The semiconductor sample is surrounded by air, which is a much poorer thermal conductor than the semiconductor itself. Therefore, adiabatic boundary conditions for the heat flux are assumed [

35].

Nonlinear effects in heat conduction and the transport of photogenerated charge carriers through the semiconductor, as well as thermal relaxation effects, are neglected because these effects are not expected to be significant in photoacoustic experiments.

Under these assumptions, the conduction of photogenerated heat through the semiconductor sample can be described by the one-dimensional classical Fourier’s theory of heat conduction [

36], leading to the following system of linear partial differential equations:

with inhomogeneous boundary conditions [

12]:

and zero initials conditions.

In above equations (Eqs 5-8) with is denoted the temperature variations in relation to ambient (initial) temperature, .

Since the problem is linear, the temperature distribution in the illuminated semiconductor sample can be obtained by applying the Laplace transform to Eqs. (5)–(8). In this case, the system of equations (5)–(8) reduces to a system of ordinary differential equations in the complex domain:

with following boundary conditions:

In Eqs. (9)–(12), the variables with an overline denote the Laplace transforms of the temperature, heat flux, the time function describing the modulation of the excitation beam’s amplitude, and the recombination heat sources on the illuminated and non-illuminated surfaces. With is denoted complex frequency.

Symbols

represent the complex coefficient of heat propagation and thermal impedance, respectively, defined as follows:

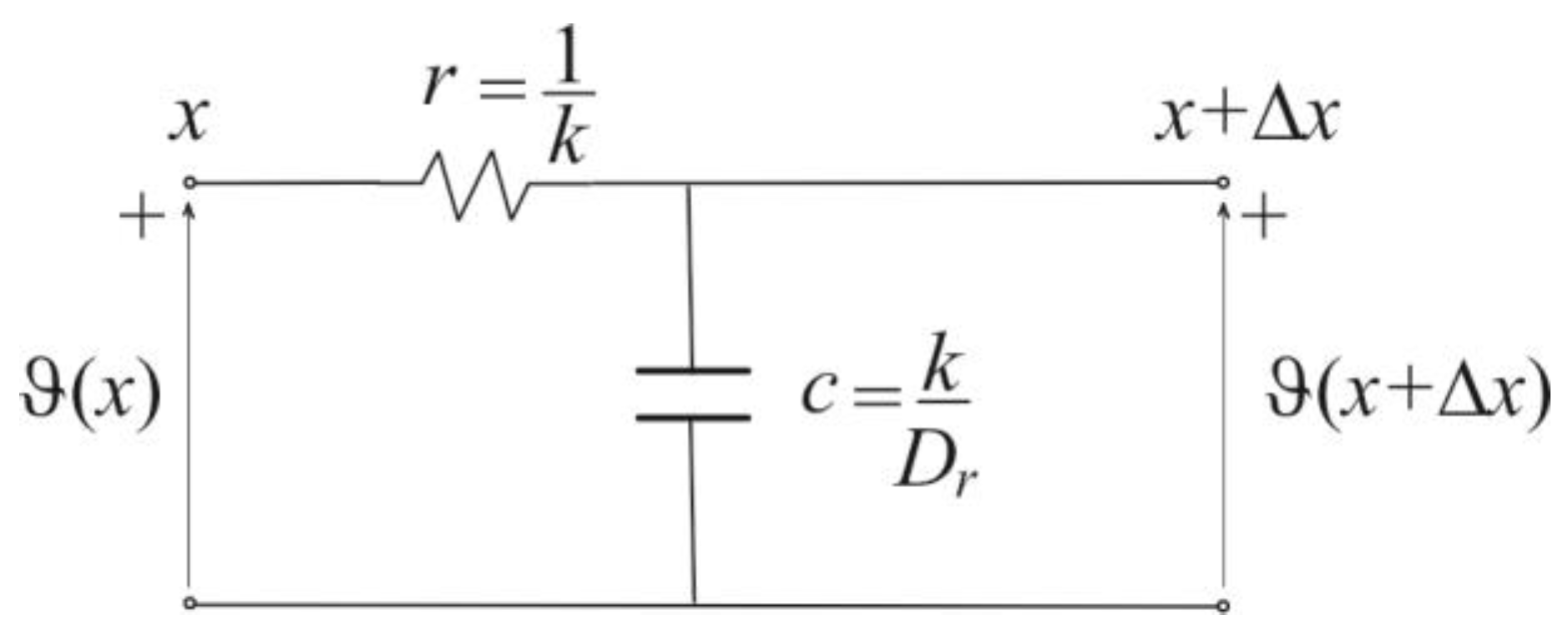

As can be seen from Eqs. (9)–(10), heat propagation through the semiconductor sample is described by equations analogous to those governing the propagation of current and voltage through an electrical transmission line [

37,

38], (see

Figure 2) with the propagation coefficient

and characteristic impedance

that can be defined as

With symbols

and

are denoted complex series impedance and complex parallel admittance of transmission line segment (Fig2)

As can be seen from the boundary conditions (11)–(12), heat propagation is driven by surface heat fluxes, which is analogous to the excitation of an electrical transmission line by current sources (boundary conditions (11)–(12):

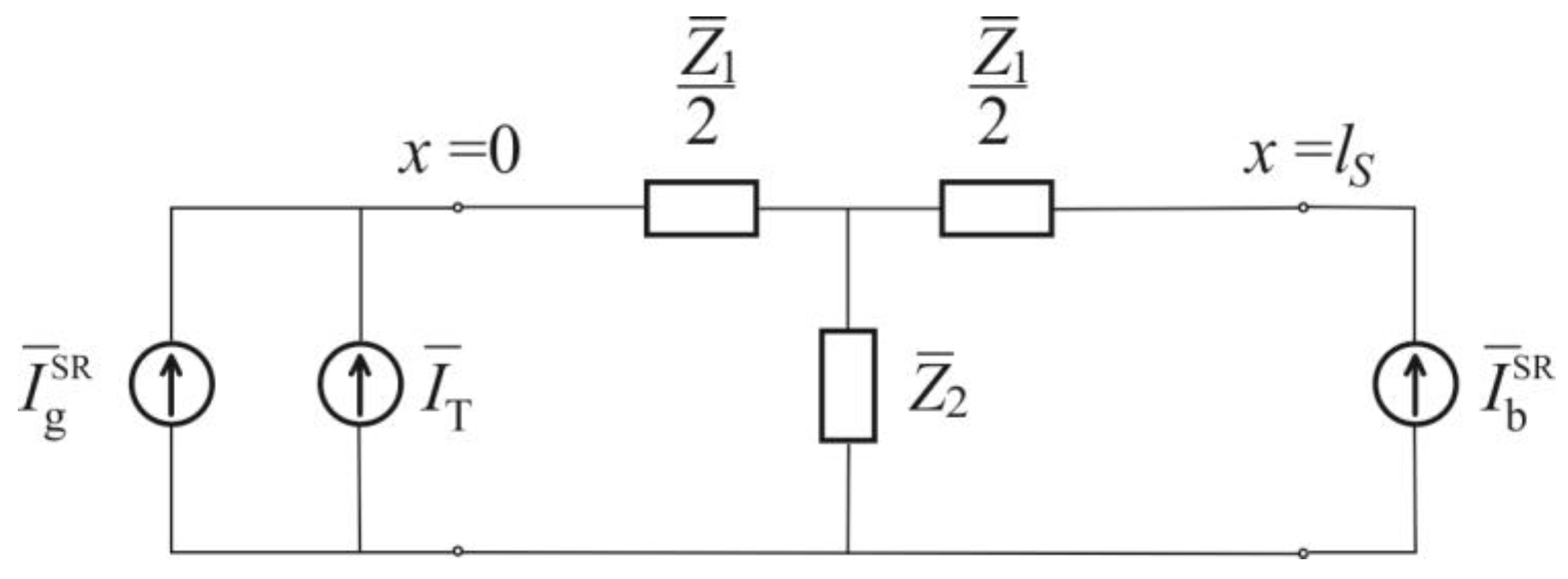

To calculate surface temperature variations on the unilluminated side, it is convenient to use the representation of an electrical transmission line via a symmetrical electrical T-network with two ports (quadripole) [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42,

43]. The analogous electrical circuit for calculating surface temperature variations on the unilluminated surface is shown in

Figure 3.

The impedances of the equivalent electrical circuit shown in

Figure 3 are given by the expressions [

37,

39]:

where

and

denote the equivalent longitudinal impedance and the equivalent longitudinal admittance, respectively:

while the equivalent current sources are given by the following expression:

Symbols , and signify the spectral function of concentrations of minority charge carriers at illuminated and non-illuminated surfaces, respectively while with si i=g,b are denoted the surface recombination velocity at corresponding surface i: g-illuminated and b non-illuminated.

Spectral functions of charge carrier concentrations are obtained by solving diffusion equation for minority charge carriers [

12,

28] (see

Appendix A):

In the above equations,

E denotes the energy of the exciting photons, which depends on the wavelength of the optical excitation, while

and

(see Appendix 1) represent complex functions that depend on the electronic properties of minority carriers (diffusion coefficient and lifetime), surface recombination velocities

sg and

sb, and the ratio of the sample thickness

ls to the maximum diffusion length of minority carriers

μmax (see

Appendix A)[

28].

By substituting Eqs 28 and 29 into Eqs. 26 and 27, a mathematical description of the spectral functions of recombination heat sources in the illuminated semiconductor is obtained:

As can be seen from Eqs 30 and 31, the recombination sources can be described as a convolution of the function that represents the thermalization source and the functions Gg(t) or Gb(t), which depend on the diffusion of minority carriers in the semiconductor.

By applying the superposition principle in solving the circuit shown in

Figure 3, we obtain the spectral functions of the total temperature variations on the unilluminated surface as a sum of temperature variations generated by each of the sources described in equations (25), (30), and (31):

It is important to note that there are two limiting cases considering frequency of excitation harmonic: the thermally thin sample () and the thermally thick sample ().

Considering definition of

(Eq. 13) the following relation is obtained:

From the above equation (Eq. 33), it can be easily concluded that for low frequencies, below a certain cutoff frequency f

c (which depends on l

s and D

T), every sample is thermally thin. Conversely, for high frequencies, above the cutoff frequency f

c, every sample is thermally thick, where f

c is given by:

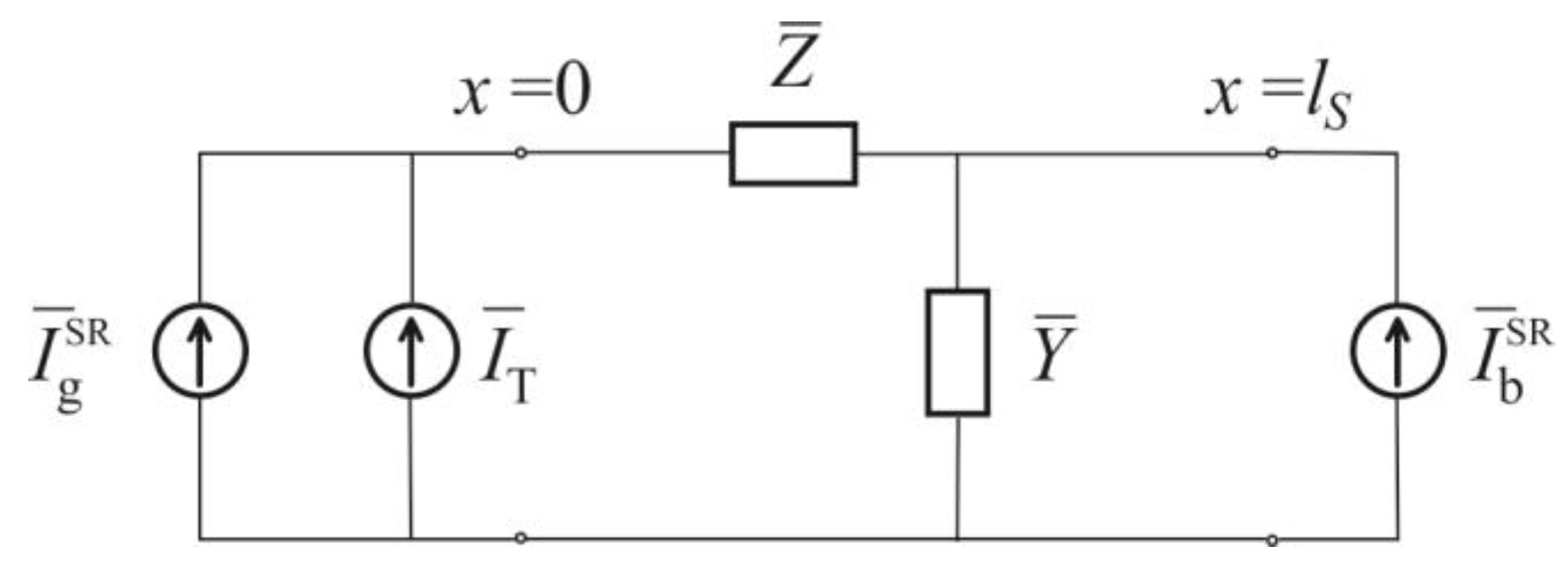

In further considerations, we will assume that the sample is geometrically thin, so that the excitation harmonics span a wide frequency range and the sample is thermally thin. In this case, the equivalent circuit from

Figure 3 is reduced to the equivalent circuit shown in

Figure 4 [

37].

By solving the circuit shown in

Figure 4, we obtain the spectral functions of surface temperature variations caused by photon-lattice interactions, as well as the spectral functions of temperature variations resulting from surface recombination of photogenerated excess charge carriers (Eqs. 35-37):

By substituting Eqs 24 and 25 into Eq 35, the spectral function of surface temperature variations caused by lattice thermalization at the non-illuminated side of the semiconductor sample exposed to the action of a square optical pulse of duration T is obtained:

By substituting Eqs 24, 30, and 31 into Eqs 36, 37, the spectral function of surface temperature variations due to recombination sources at the surface of the semiconductor, is obtained:

By finding the inverse Laplace transform Eq 38 we obtain [

44,

46]:

Considering heat sources generated by recombinations of minority carriers at sample surfaces depend on ratio of the sample thickness and diffusion length of minority carries i.e. plasma transparence [

28], we further observe two limiting cases : the case thermally thin and plasma opaque and the case of thermally thin and plasma transparent sample.

2.1. Surface Temperature Variations in Thermally Thin and Plasma Opaque Semiconductor Sample

The spectral functions of recombination heat sources in plasma opaque samples are given by [

28]:

where

Symbols and signify the diffusivity of minority charge carriers and their lifetime, respectively (see Appendix1).

In that case, the temperature variations generated by surface recombination become:

By finding inverse Laplace transform of Eq 44, we obtain (see Appendix 2)

where function g

1 is defined by:

and

2.2. Surface Temperature Variations in Thermally Thin and Plasma Transparent Semiconductor Sample

The spectral functions of recombination heat sources in plasma transparent samples are given by [

28]

Parameters

r1, r2, p, and

q are defined by the following expressions:

By substituting expressions (50) and (51) into equation (39), we obtain the spectral function of temperature variations in a thermally thin and plasma-transparent semiconductor sample, caused by surface recombination heat sources:

with parameter

r3 defined by

By finding inverse Laplace transform of Eq 56, (see Appendix2) we obtain:

with function g

2(t) defined by

3. Analyzes and Discussion

The PA measurements with a minimal volume cell record pressure fluctuations in the gas column located on the non-illuminated side of the sample. The measurement configuration is transmission-based, as the source and detector are on opposite sides of the sample being examined [

47]. Literature indicates that in this type of measurement configuration, the spectral function of resulting pressure fluctuations in the closed cell can be described by a composite piston model [

48]. Specifically, these pressure fluctuations are a consequence of the thermal piston effect, which involves the expansion and contraction of the thin layer of air adjacent to the illuminated surface of the sample [

49,

50]. Additionally, the bending of the sample surface due to the generation of a thermal moment within the sample [

48] acts as a mechanical piston, producing the thermoelastic (TE) component of the PA response.

In semiconductors, due to the photogeneration of charge carriers, there exists a plasma-elastic component resulting from the bending of the sample surface caused by the concentration gradient of excess charge carriers in illuminated semiconductor samples [

12,

51]. If the sample is thin, both the TE and plasma-elastic components can be neglected [

16,

52]. In that case, it can be assumed that the pressure fluctuations are caused solely by the thermal piston effect and are consequently proportional to the surface temperature variations [

52,

53,

54,

55].

However, the thermal piston model is not suitable for time-domain photoacoustics [

16,

30,

56,

57,

58]. In this case, it is more appropriate to use models derived in [

16,

30,

56,

57,

58], which also indicate that temperature changes at the non-illuminated surface generate pressure variations in a closed PA cell. However, the thermal thickness of the gas column in the closed PA cell [

30] and the transfer characteristics of the microphone [

16,

30] can alter the time profile of the recorded time-resolved electrical signal.

In this study, we analyze the evolution of temperature changes at the non-illuminated surface and the influence of photogenerated charge carriers on the magnitude and slope of these changes based on the derived model (hereafter referred to as the time-domain temperature signal). However, modeling the transfer function of the gas column (

) and the microphone (

), which is essential for a complete understanding and accurate processing of the recorded time-resolved PA signal in semiconductors [

17], remains the focus of our future research.

In the calculations, it was assumed that the excitation occurs in the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum meaning

E/EG for narrow gap semiconductors such as Si is equal to unity [

12]. The normalized components were considered relative to the constant

.

The parameters of the silicon sample used in the calculations are provided in

Table 1.

In the analysis, it was also assumed that the pulse duration is 50 ms, as impulses of this duration are used in real time-domain PA experiments [

16,

17].

Let us consider the thicknesses of the Si sample for which the assumptions of the derived model are satisfied.

The optical absorption coefficient of silicon is 10

5 m

−1 for light from the visible part of the electromagnetic spectrum [

34]. Consequently, the approximation of optically opaque sample is reasonable for silicon samples thicker than

.

Since the thermal diffusivity of silicon is 9·10

-5 m

2s

−1 [

12], the cutoff frequency between thermally thin and thermally thick regimes for a sample with a thickness larger than 10 μm can be calculated from Eq. (34). It ranges from approximately 5 kHz for a 90 µm thick sample to 300 kHz for a 10 µm thick sample. For samples which thickness is about 100 µm, the cutoff frequency varies from 50 Hz for a 900 µm thick sample to 3000 Hz for a 100 µm thick sample. This implies that in the PA measurement range (from 50 Hz to a few kHz), silicon samples with a thickness of 10-150 µm can be considered as thermally thin.

Finally, in our model, we considered two cases related to the ratio of the maximum diffusion length of minority carriers to the geometric thickness of the sample. These are the case of a plasma-opaque sample, when this ratio is less than one, and the case of a plasma-transparent sample, when this ratio is greater than one.

Since the maximum diffusion length of minority carriers is given by the square root of the product of their diffusion coefficient and lifetime (see Appendix 2), it can be estimated based on the parameters given in

Table 1 that a p-doped silicon sample with a thickness greater than 135

is plasma-opaque, while an n-doped silicon sample is plasma-opaque if it is thicker than 75

. This means that Si samples, whether p- or n-doped, with a thickness below 75

are plasma-transparent, whereas samples thicker than 135

are plasma-opaque.

In the further analysis, we considered silicon samples with a thickness of 20 as representatives of plasma-transparent, thermally thin, and optically opaque semiconductor samples, and samples with a thickness of 140 as representatives of plasma-opaque, thermally thin, and optically opaque semiconductor samples.

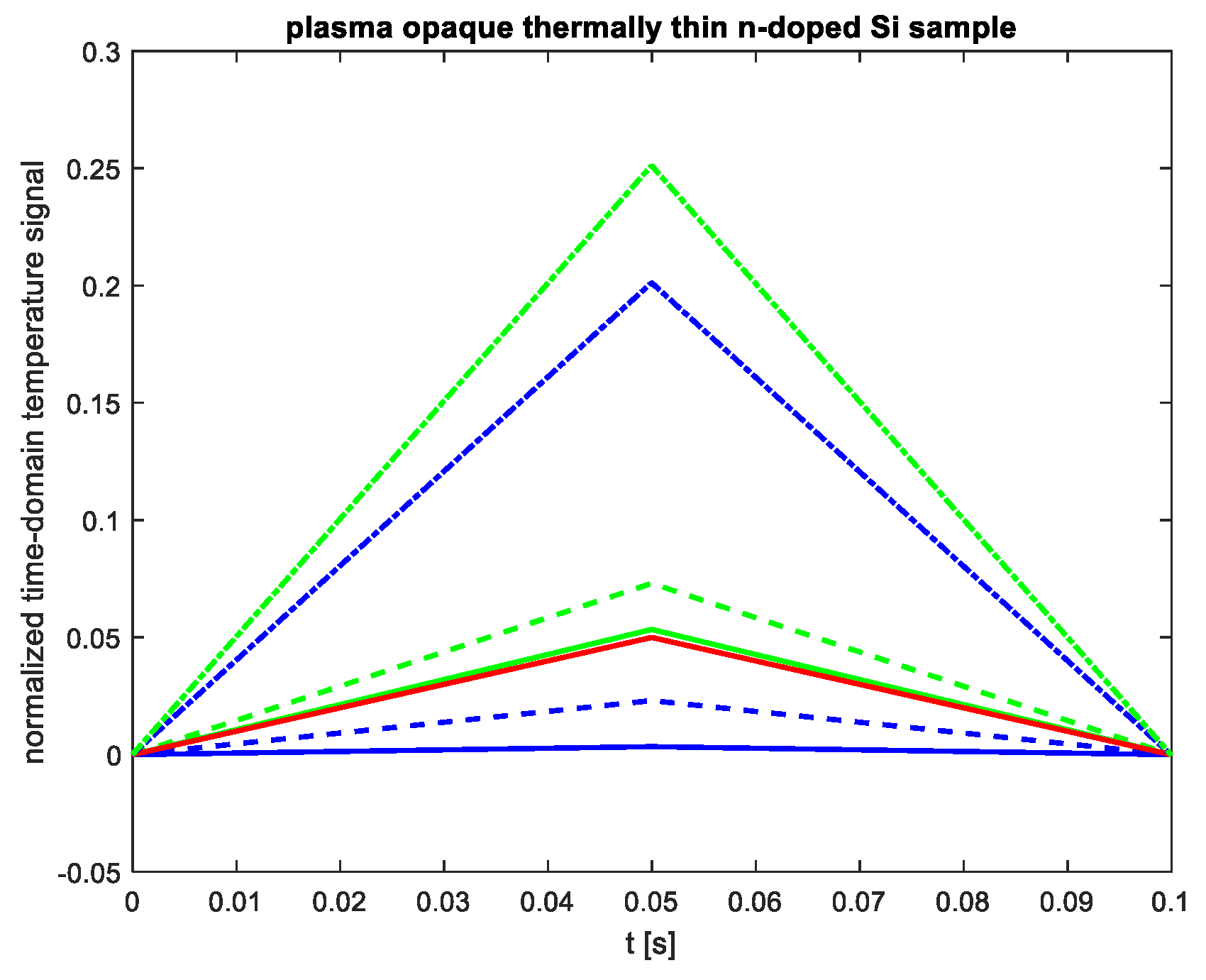

Figure 5 shows the normalized time domain temperature signal (evolution of temperature change on the non-illuminated side) for a thermally thin, plasma-opaque n-doped silicon sample (

ls = 140 µm,

Dp = 1.2 × 10⁻³ m²/s). The red line represents the signal originating from lattice thermalization (fast thermal source), while the blue lines correspond to signals influenced by surface recombination for different values of

sg. The green lines depict the total signal resulting from both sources. (Legend:

sg = 6 m/s (solid line),

sg = 10 m/s (dashed line),

sg = 14 m/s (dash-dot line)).

As shown in

Figure 5, in plasma-opaque and thermally thin samples, carrier recombination does not alter the shape of the signal but does affect its maximum value (blue and green lines). When paremeter

sg is low (below 6 m/s) the contribution of recombination sources is negligible and the signal is primarily determined by lattice thermalization (solid red and green lines). However, as

sg increases, recombination effects become more significant. For

sg = 14 m/s, recombination sources play a dominant role in temperature change (dash-dot green and blue lines in

Figure 5).

From

Figure 5, it can also be observed that the time domain temperature signal for a thermally thin semiconductor sample reaches a steady value of zero after a time equal to 2

T. This indicates that the settling time is equal to twice the duration of the optical pulse.

In cases where the signal does not reach a peak during the pulse duration, it is not appropriate to work with parameters such as rising time or falling time; instead, it is much more suitable to consider the slope of the rising or falling curve.

Figure 5 shows that the slopes of the rise after the leading edge of the excitation and the slope of the fall after the trailing edge of the pulse are equal and depend on the surface recombination velocities.

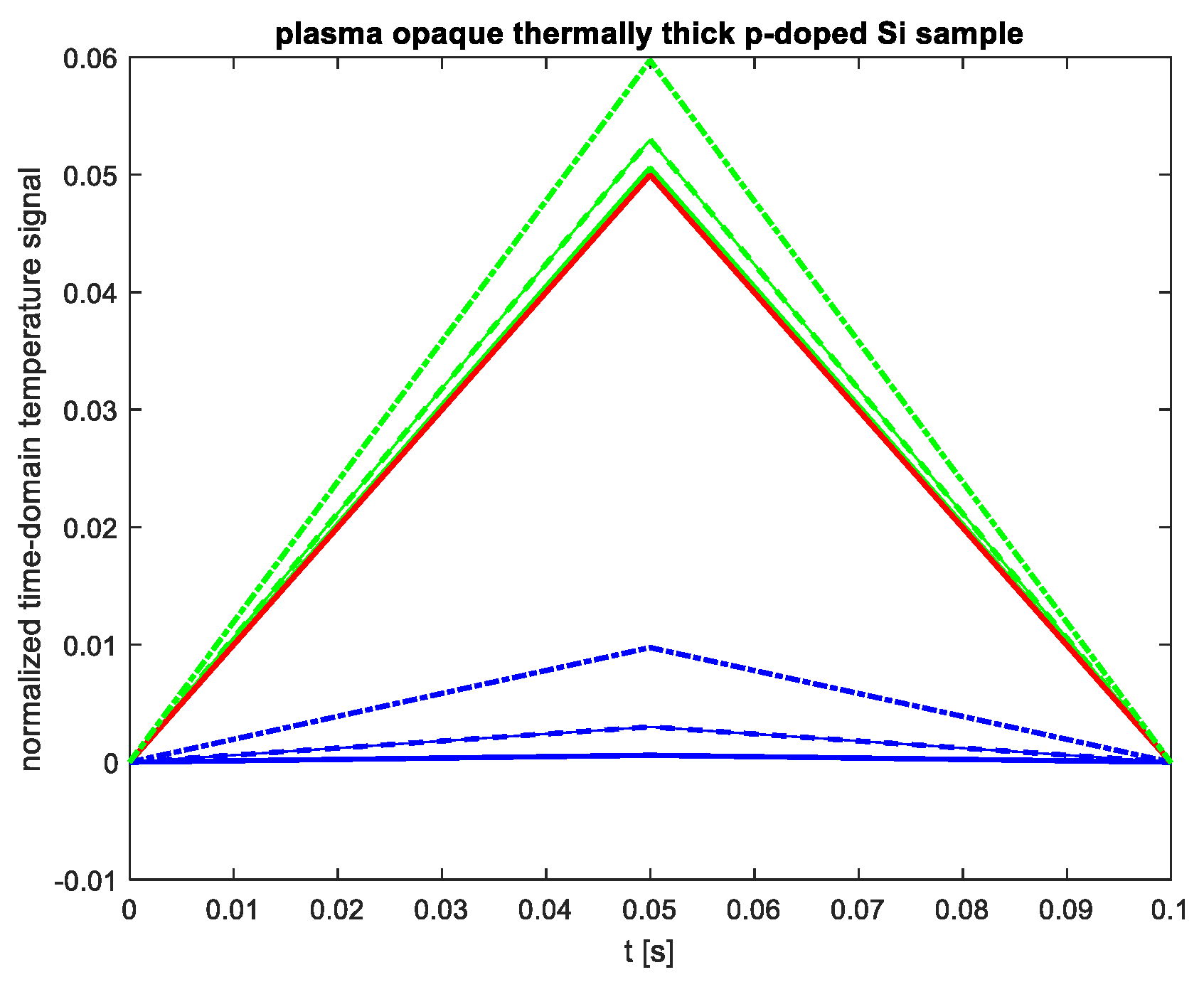

To investigate the impact of the charge carrier diffusivity (the semiconductor electronic property) on the shape of the time-domain temperature signal,

Figure 6 presents the signal for a thermally thin and plasma-opaque p-doped Si sample (

ls=140 µm,

De=3.6×10

−3 m

2/s,). The red line represents the signal resulting from lattice thermalization (fast heat source), while the blue lines indicate the signal from surface recombinations at different

sg values. The green lines show the total signal caused by both sources:

sg=6m/s (solid lines),

sg=10m/s (dashed lines), and

sg=14m/s (dash-dotted lines).

As seen in

Figure 6, for the plasma-opaque and thermally thin p-doped sample, the recombination of charge carriers similarly affects the time domain temperature signal as in the n-doped sample (

Figure 5). Specifically, it does not influence the shape or settling time, but it does impact the maximum value of the signal in the time domain (indicated by the blue and green lines in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6) and the slopes of both the rising and falling curves.

However, in the case of the p-doped sample, minority carriers are electrons, which have a diffusion coefficient three times larger (as shown in

Table 1). Therefore, at the same surface recombination velocities, the dominance of recombination sources does not occur for the

sg>10 m/s (

Figure 6).

Based on this observation, it can be concluded that the slopes of the time-domain temperature signal—both the rising slope following the leading edge of the optical pulse and the falling slope following the trailing edge—are influenced by the electronic properties of the semiconductor, particularly the diffusion coefficient of the minority carriers. The increase in diffusion coefficient affect slower rising and falling of the signal and consequently smaller maximal value of the signal for the same surface recombination velocities.

It is interesting to note that the results presented in

Figure 5 and

Figure 6 indicate that the complex function describing the time-domain temperature signal in thermally thin and plasma-opaque samples (Eq 47) can, in fact, be approximated by a linear function. The electronic parameters of silicon (such as the minority carrier lifetime and their diffusion coefficient) primarily influence the slope of the linear function.

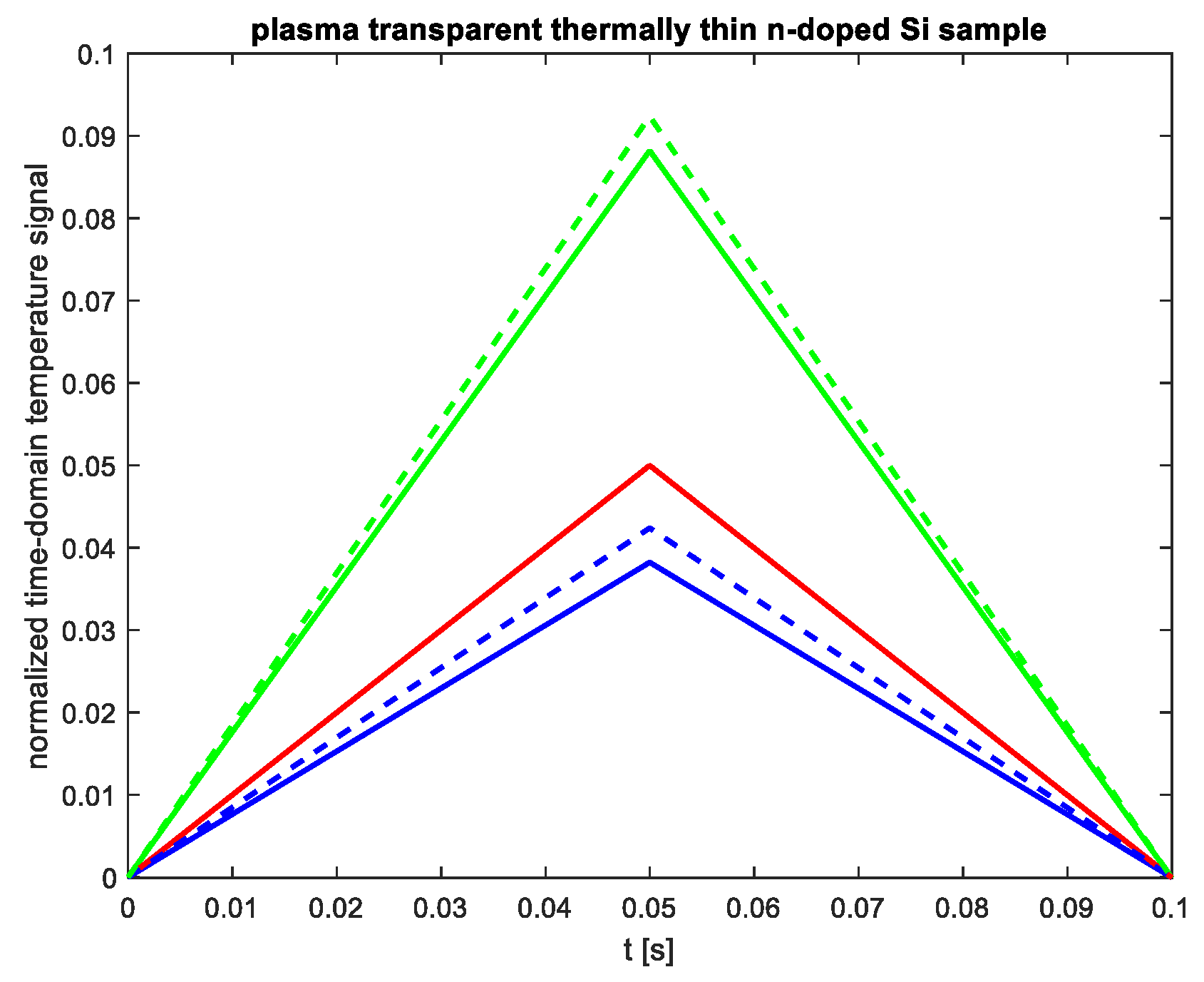

Figure 7 illustrates the normalized time-domain temperature signal for a thermally thin and plasma-transparent n-doped silicon sample (with

ls=20µm and

Dp=1.2×10

−3 m

2/s). The red line represents the signal originating from thermalization of the lattice (a fast heat source), while the blue lines show the signal resulting from surface recombinations for

sb=6m/s and various

sg values. The green lines depict the total signal generated by both sources (

sg=6 m/s a solid line and

sg=14 m/s as a dashed line)

As seen in

Figure 7, the time-domain temperature signal from the plasma-transparent sample behaves similarly to that of the plasma-opaque sample in terms of shape, settling time, and dependence on

sg. However, for the plasma-transparent sample, the rise and fall slopes are also influenced by the surface recombination velocity

sb. This results in a slower rise of the signal, leading to significantly lower maximum signal values when all other electronic and thermal parameters remain constant if the sample is plasma transparent.

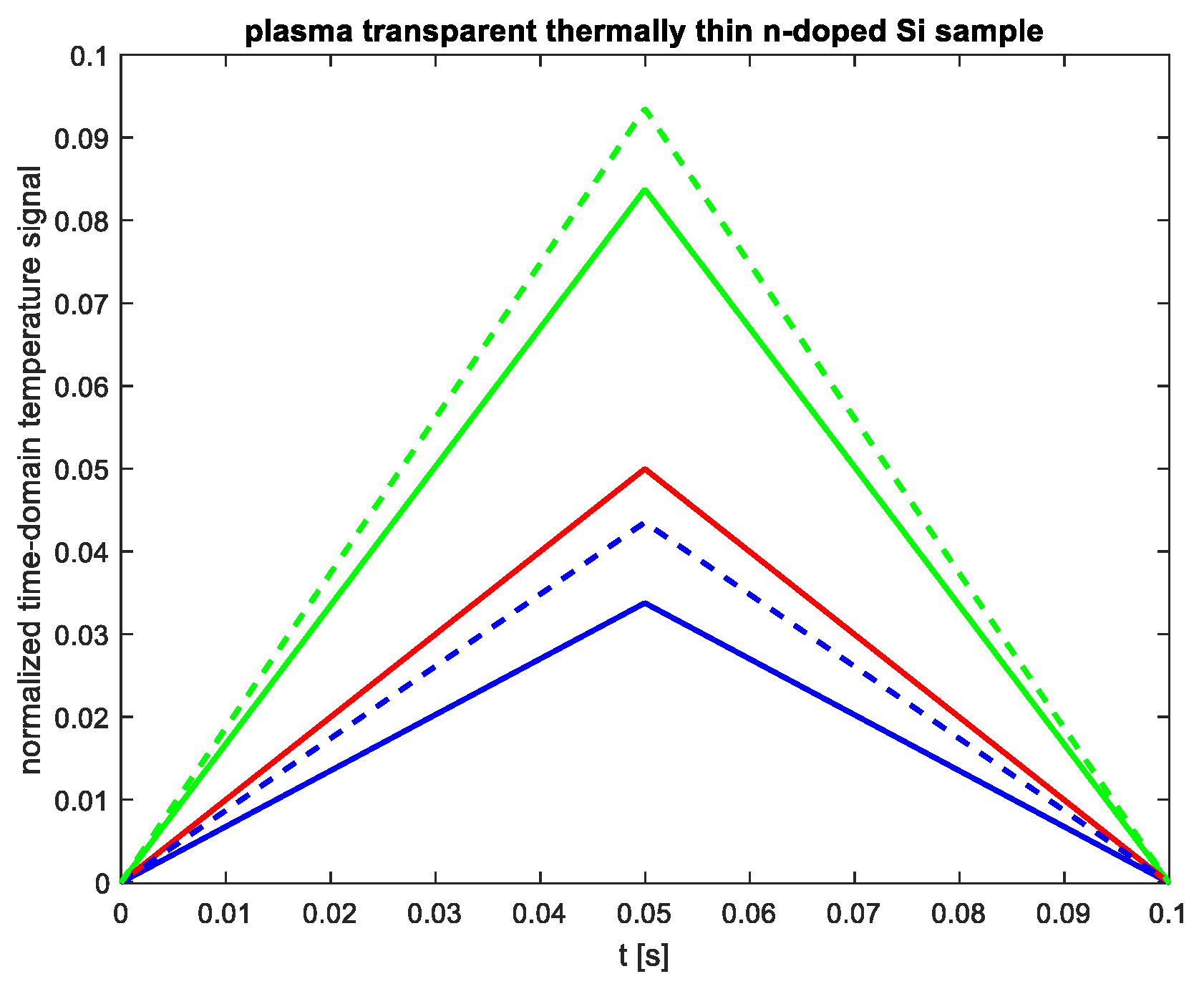

To further investigate the impact of

sb,

Figure 8 presents the time-domain temperature signal for a thermally thin and plasma-transparent n-doped silicon sample (

ls=20µm,

Dp=1.2×10

−3 m

2/s) with a fixed

sg=2 m/s. The value of the surface recombination velocity on the unilluminated side,

sb, was varied. The red line indicates the signal resulting from thermalization of the lattice (a fast heat source), while the blue lines show the signal from surface recombinations for

sg=2 m/s at different

sb values. The green lines represent the total signal caused by both sources, with

sb=6 m/s indicated by a solid line and

sb=24 m/s by a dashed line.

As seen in

Figure 8, the increase in

sb influences both the slope of the time-domain temperature signal and the maximum value the signal reaches just before the falling edge of the optical pulse, similar to the effect observed with an increase in

sg.

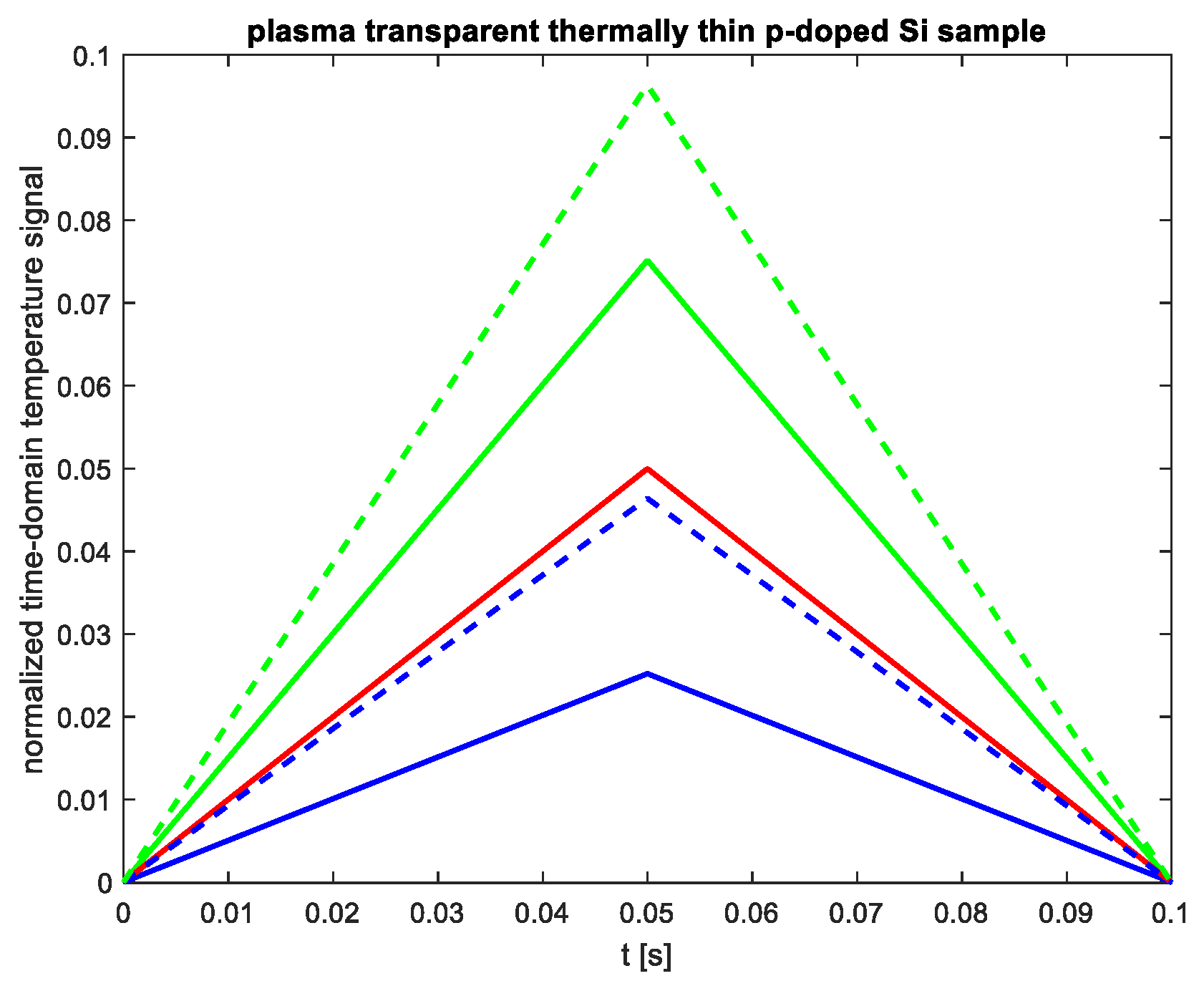

Finally,

Figure 9 presents the normalized time-domain temperature signal for a thermally thin and plasma-transparent p-doped Si sample (with

ls=20 μm and

Dp=3.6×10

−3 m

2/s) at

sg=2m/s,

sb=2m/s and

sg=24m/,

sb=24m/s. This analysis aims to investigate the influence of the electronic properties on time domain temperature signal of the thermally thin and plasma transparent semiconductor sample.

By comparing the results shown in

Figure 8 and

Figure 6, it is evident that an increase in the diffusion coefficient of minority carriers, similar to the case of plasma-opaque samples, influences both the maximum value that the time-domain temperature signal can achieve during the pulse duration and the steepness of the nearly linear rising and falling curves. However, this increase does not affect the settling time.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, a model for temperature change on the non-illuminated side of thermally thin semiconductors exposed to a rectangular optical pulse has been developed. This model incorporates the impact of surface recombination of photo-generated charge carriers at the semiconductor surfaces.

Based on the derived model, the influence of recombination sources and the electronic properties of semiconductors on surface temperature evolution have been analyzed using moderately n- and p-doped silicon samples as examples.

It has been demonstrated that, depending on the surface recombination velocity (which is influenced by the surface processing methods of the samples), recombination sources can significantly affect the magnitude of the surface temperature change and the slopes of its rise and decay, compared to the effect of lattice thermalization. The dominant influence of recombination sources is observed in plasma-opaque samples with high surface recombination velocity at the illuminated surface.

At low surface recombination velocities, lattice thermalization is the dominant mechanism of sample heating and influence of recombination sources can be neglected in plasma-opaque and thermally thin samples. In plasma-transparent samples, although recombination does not dominate over lattice thermalization, it remains significant at both low and high surface recombination velocities.

Furthermore, the electronic properties of the semiconductor affect the slope of the rising and falling temperature signal and its maximum value but do not influence the overall shape of the signal or the settling time.

Our results show that charge carrier recombination can have a significant impact on the temperature change at the non-illuminated side of a semiconductor sample and, consequently, on the time-domain PA signal. The observed dependence of time-domain temperature signal on the sample thickness, surface processing, and diffusion coefficient of minority charge carriers suggests that this technique could be used to determine the electronic properties of semiconductors.

For a complete understanding and accurate processing of experimentally recorded time-resolved PA signals in thin semiconductor membranes [

17], further investigation are required to understand the transformation of non-periodic temperature changes at the sample surface into pressure fluctuations and the subsequent conversion of these fluctuations into an electrical signal. This remains the subject of our ongoing research.