1. Introduction

Alpacas are domestic camelids that belong to the South American Camelid family. They are native to the Andean highlands (e.g., Chile and Bolivia), but mainly from the Altiplano region of Peru. [

1,

2]. According to [

3], there are two types of alpacas in Peru: Huacaya and Suri. Huacaya alpaca accounts for more than 90% of the total alpaca population. [

1]. Alpaca fiber is widely valued in the Peruvian textile industry, because of its unique properties (e.g., thermal qualities, mechanical resistance, and impermeability) which enhance its potential for innovative fashion [

4]. Chemically, Alpaca fiber is based on the same protein (e.g., keratin) as wool which gives it the same dyeing properties [

2]. However, Alpaca fiber dyeability uses different conditions that are adjusted to suit its various characteristics, such as medullation, larger diameter, among others.

Generally, the Alpaca fiber dyeing process uses synthetic dyes, such as acid dyes, reactive dyes, basic dyes, and VAT which enable consistent colors to achieve significant characteristics and results for high-quality products. However, these dyes have disadvantages related to their environmental impact and the associated toxicity of their complex molecular structures which cause several diseases in humans [

5]. According to [

6], the application of these dyes has deleterious effects on all living organisms. The detrimental nature of these substances has raised growing concerns among environmentalists, thereby stimulating efforts to identify and develop sustainable and environment-friendly alternatives.

Based on the aforementioned, dyes obtained from natural sources, such as plant extracts (e.g., leaves, flowers, roots, and others), animals (e.g., cochineal lac from

Dactylopius coccus and Tyrian purple from sea mollusk), minerals (e.g., malachite, ultramarine blue, azurite, charcoal black), and microbial sources (e.g., Prodigiosin from

Vibrio ssp., anthraquinones from

F. oxysporum, and others) [

7,

8] are chosen as the friendliest alternatives. However, there are some general limitations. Regarding their extraction, the labor-intensive isolation of the coloring compounds [

9] is complex; in this case, plant sources carry low amounts of dye or pigment as well as contain many compounds apart from the principal molecules, making the process time-consuming and difficult [

7]. Another limitation concerns the fade and instability where plants and microbial sources present potential challenges. According to [

10] many microbial pigments present have a limited life cycle under ambient conditions which becomes unusable, even the production could be affected by a contamination of raw materials. The challenges of dyeing procedures (e.g., difficulty in achieving precise control, low color yield, extended processing times, and other related issues) limit their feasibility for mass production. [

6,

11,

12].

As these challenges restrict the large-scale use of many dyes, certain artificial alternatives have shown potential [

6]. One dye that has found a place in the food and textile industry is Indigo Carmine (IC), also known as Indigotine, C.I. Natural Blue 2, indigo-5.5’-disulfonic acid disodium salt, among others [

13]. Despite being an artificial dye, IC could offer advantages that would make it attractive from both a technical and environmental perspective for dyeing protein fibers such as Alpaca fiber [

14]. As a dye approved by regulatory bodies such as the European Food Safety Authority (EFSA), its toxicity levels are lower than other synthetic dyes making it easier to handle [

15,

16]. Likewise, IC is characterized by its moderate heat stability and good resistance to reducing agents, although it has poor pH, light, and oxidation stability [

17,

18]. In addition, its solubility in aqueous media (10 g/L) and stability would allow a more efficient dyeing process [

16]. As discussed earlier, IC could be used for protein fiber dyeing such as Alpaca fibers.

The present study aims to determine the optimal dyeing conditions for Alpaca fiber with indigo carmine. For this purpose, Response Surface Methodology (RSM) has been employed in order to optimize the process, due to the freedom to evaluate the effect and interaction of multiple process factors simultaneously [

19]. Furthermore, the design experiments (DOE) were designed by the Central Composite Design (CCD), because of the construction of a design experiment that enables the establishment of a comprehensive correlation between the independent variables [

19,

20]. Experimental variables (mordant concentration, dyeing temperature, and exhaust time) were evaluated on the color strength value (K/S, dependent variable) which allows us to comprehensibly understand the relationships and effects among these variables. This approach will enable us to comprehend the dyeing process using indigo carmine on Alpaca fiber.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials and Reagents

For all dyeing experiments, Alpaca yarns were purchased from INCA TOPS S.A. (Arequipa, Peru), and their specifications are listed in

Table 1. Indigo carmine (C₁₆H₈N₂Na₂O₈S₂) was acquired from Aromas del Peru S.A. Tartaric acid (C

4H

6O

6) was purchased from Delta Quimica S. R. L. (Arequipa, Peru). Both tartaric acid and indigo carmine were food-grade quality. A non-ionic detergent (Hepalwed PDA), was kindly supplied by CITEtextil Camélidos Arequipa, which was used to wash and moisturize the fibers before dyeing.

2.2. Alpaca Fiber Sample Preparation

Before the dyeing process, Alpaca fibers were initially processed using an electronic wrap reel for yarns (161M_XYW, MESDAN, Peru) in order to produce skeins of uniform weight. This step ensured consistency in sample preparation which is essential for subsequent stages of the process. Then, Alpaca yarn samples were immersed in a non-ionic detergent solution (1 g detergent/L distilled water) as pre-treatment to moisturize their surface and remove the excess paraffin and fat [

21]. The solution was heated to 60 °C for 10 min, after which, the samples were rinsed with distilled water to remove superfluous detergent.

2.3. Alpaca Yarn Mordanting Process

The yarn samples were mordanted by a simultaneous mordanting method as shown in [

21]. In this context, the samples were immersed in the dyeing bath containing the dye liqueur and acidic-mordant diluted [

20]. For the point of sustainability, [

22] reported eco-friendly alternatives for conventional mordants. Herein, we used tartaric acid (

) as an acidic-mordant [

23,

24].

2.4. Dyeing Process with Indigo Carmine

The samples were dyed using an exhaustion method in a dyeing machine (AHIBA IR PRO, DATA COLOR, USA). The dyeing experiments were performed using a bath ratio of 1:30 (M: mL) in separate baths, with a dye concentration of 3% (o.w.f.). The dyeing temperature, exhaust time, and mordant concentration were determined according to the proposed experimental design outlined in

Table 2 [

25]. Upon completion, the dyed samples were rinsed thoroughly with distilled water and dried at room condition in shade [

20,

26].

2.5. Color Analysis and Color Strengh of the Alpaca Yarn Samples

The spectral reflectance of the dyed alpaca yarn samples was measured using a Datacolor® 550 series spectrophotometer in the visible region (400 – 700 nm). In order to evaluated the chromatic characteristics (

L*, a*, b*, and

C), measurements were taken under an illuminant D65 with a 10° observation angle. The color strength (

K/S) values were calculated based on the Kubelka-Munk equation (1) as follows:

where K is the absorption coefficient; S is the scattering coefficient, and R is the reflectance value of dyed samples at maximum absorption (λ

max) [

27].

2.6. Fastness Testing

The color fastness to washing was determined according to the ISO 105 – C06 (Reaffirmed 2022) Peruvian standard based on the ISO 105-C06:1989. Wet and dry rub fastness tests were performed according to the AATCC TM 8-2007. The change in the color of the specimens and staining of the adjacent fabric were evaluated using the grayscale.

3. Results and Discussions

3.1. Color Analysis of the Dyed Alpaca Yarns Using Indigo Carmine

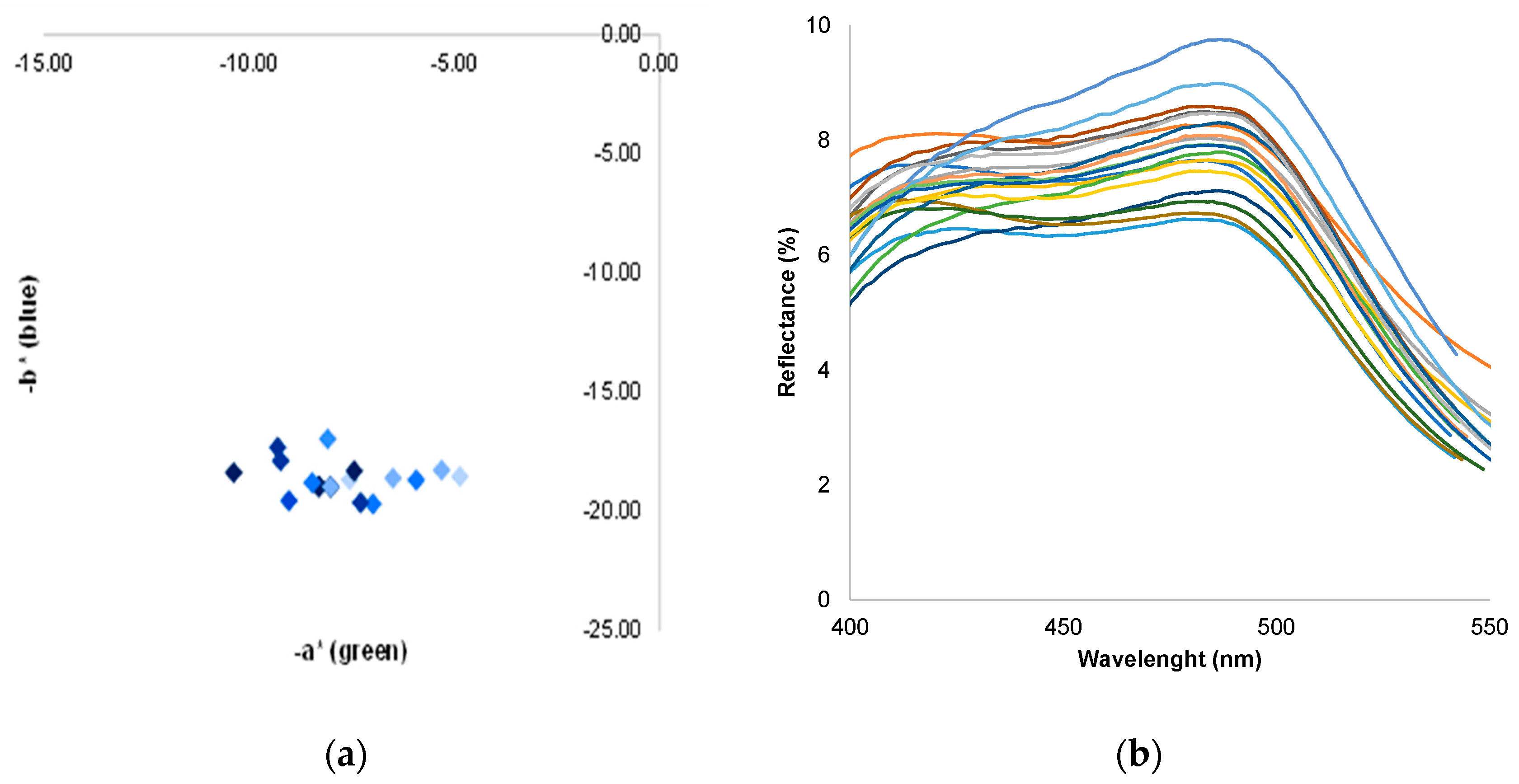

According to the experimental results, the a*- b* plot (

Figure 1a) clearly shows a predominantly hue in all dyed samples. The color coordinates were positioned in the third quadrant of the CIE L*a*b* color space diagram indicating that the Alpaca yarn samples dyed with indigo carmine caused a particular blue shade. This is consistent with the spectral reflectance of the dyed samples, as shown in

Figure 1b. In this context, the dyed samples have more reflectance in the wavelength associated with the violet (~380 – 435 nm), indigo/blue (~436 – 480 nm), and greenish-blue (~491 – 500 nm) range to begin to decrease noticeably in the green range (~500 – 560 nm). This suggests that the dyed samples absorbed green light and reflected blue light [

27].

3.2. Model Fitting and Regression Analysis

In order to determine the dyeing condition (mordant concentration, dyeing temperature, and exhaust time) effects on the color strength (K/S) of dyed Alpaca yarns, Central Composite Design tests were performed. Therefore, in order to verify the model’s adequacy, the experimental data were fitted to four potential models (Linear, 2Fl, Quadratic, and Cubic) which are presented in

Table 3.

According to the ANOVA fitting results analyzed using Design Expert® (v.13.0) software, the dyeing process of Alpaca yarns using indigo carmine was most suitable described by a quadratic model, as indicated by the sequential

p-value, the adjusted

, and the

p-value of lack of fit. In regression analysis, the appropriate selection of a model that describes the relationship between variables is essential [

28]. In this context, the quadratic model outperforms the two-factor interaction (2Fl) model based on statistical metrics. Firstly, the sequential

p-value for the quadratic model is 0.0050 which is much lower than 0.05, indicating that adding the quadratic terms improves the model, compared to the 2Fl model (<0.0001). The adjusted

and predicted

suggest that the quadratic model provides a better explanation of variability and has predictable capabilities [

28,

29]. Moreover, the probability of the lack-of-it test was also relatively high (>0.05). This non-significant value indicates that the quadratic model does not have significant unexplained variation [

30]. In contrast, the Lack of it

p-value for the 2Fl model is 0.1155, which is closer to the significance threshold, suggesting a less reliable fit.

To verify the adequacy of the model selected, the analysis of variance (ANOVA) was carried out as shown in

Table 4, where the F-value and the probability value (

p-value<0.05) were used as the hypothesis values which indicated whether the factors are statistically significant or non-significant to the regression model [

30,

31].

Therefore, in

Table 4, it can be observed that the mordant concentration (A), dyeing temperature (B), and exhaustion time (C) effects were statistically significant since the

p-values were less than 0.05. In the case of the two-factor interaction effects, AB and BC were significant model terms. In contrast, the AC value interaction was much higher than the probability value (

p-value<0.05). On the other hand, the quadratic term

reached the conventional level of statistical significance compared to

, and

[

30]. Likewise, the high F-values for the independent factors indicate that the predicted ones have a strong effect on the color strength (K/S) of dyed Alpaca yarns with indigo carmine.

In order to enhance the model’s predictive performance, a systematic model reduction approach was employed to eliminate non-significant terms [

20]. As a result, the final quadratic model is expressed in equation (2).

where

,

, and

represent the mordant concentration, dyeing temperature, and exhaust time respectively. Moreover, the positive and negative signs indicate the direction of the effects of each coefficient term on the response variable [

19]. The determination coefficient (

) reflects the model correlation degree where the larger the

, the better the correlation [

31]. In this context, the

of the model was 97.14%, which could explain the relationship among the color strength (K/S) and mordant concentration

, dyeing temperature

and exhaust time

. The adjusted determination coefficient (Adjusted

) was 95.82%, which indicates that nearby 96% of the variance in color strength (K/S) is explained by the model. This high value demonstrate that the model fits the observed data very well and could be used for prediction and interpretation. Finally, the lack of fit (F-value = 0.72) is not significant relative to the pure error. There is a 67.40% chance that a Lack of Fit F-value this large could occur due to noise.

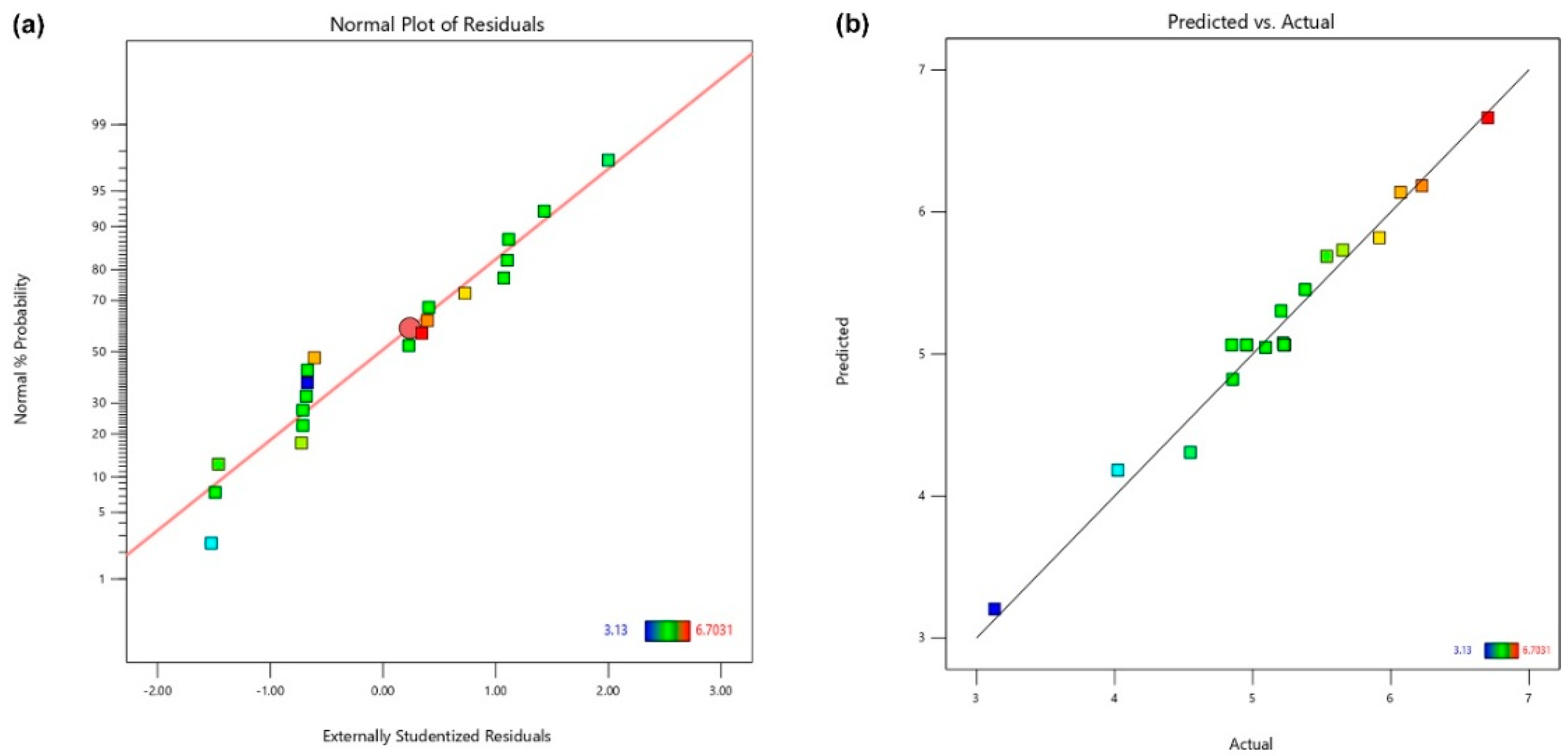

The normal probability distribution of the residual (errors between predicted and actual values) is plotted in

Figure 2a. In this context, the data points were aligned closely to the red line indicating that the quadratic model follows a normal distribution which explained the behavior between the predicted and actual values [

32]. The comparison of predicted and actual values is shown in

Figure 2b. In this case, most data points were close to the line which suggested that the model has good predictive accuracy, though some deviations (indicating slight errors) do not appear large enough to compromise the validity of the model.

3.3. Effect of Dyeing Conditions on Color Strength (K/S)

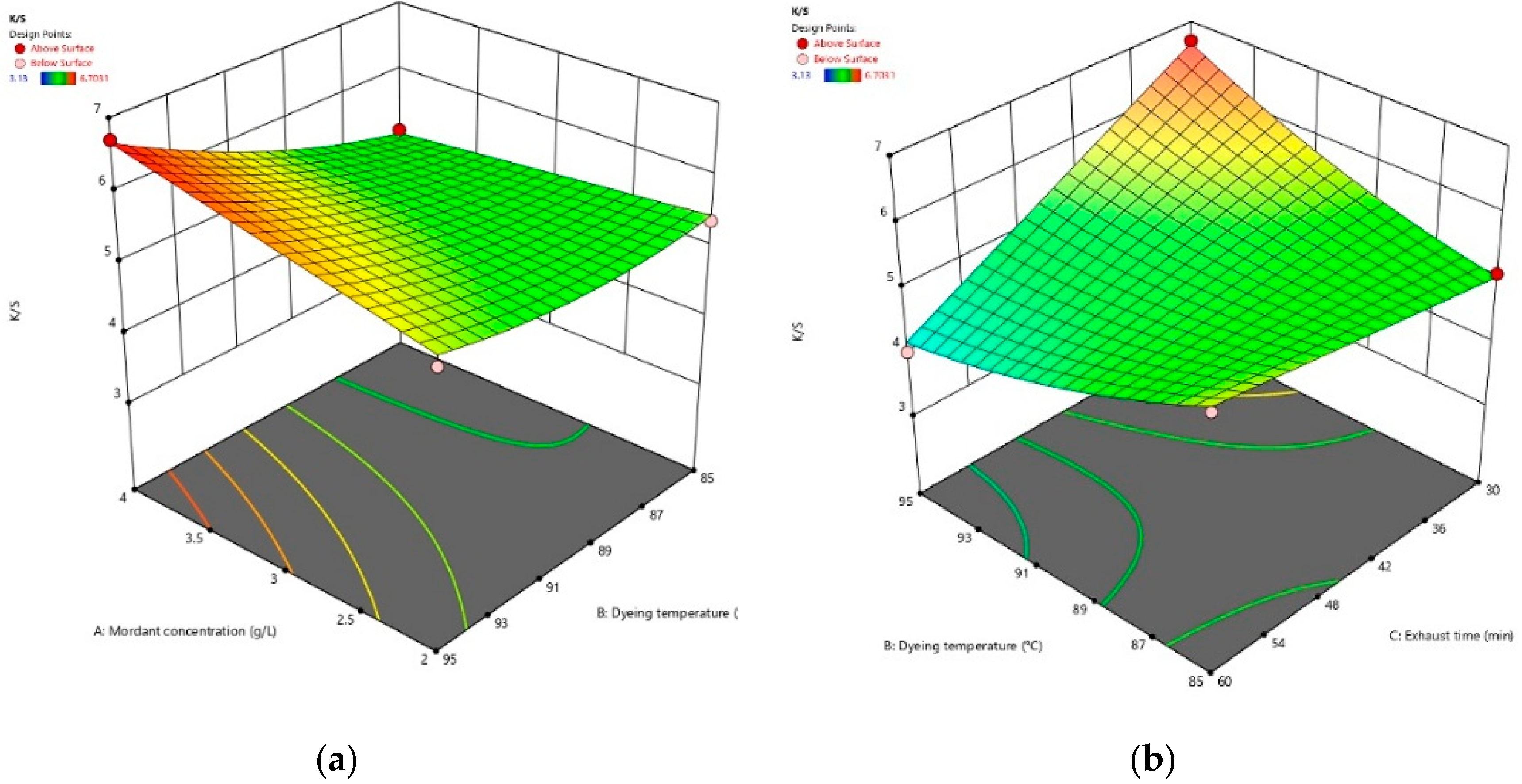

To assess the influence of dyeing conditions on color strength (K/S) of dyed Alpaca yarns using Indigo carmine, a Response Surface Methodology was employed in order to generate several diagnostic plots, where the green color represents lower K/S values and the red color represents a higher value [

28].

Figure 3a,b presents a three-dimensional surface plot.

Figure 3a shows the variation curves of the color strength (K/S) values with the mordant concentration and dyeing temperature when the exhaust time was set to 30 min. In this context, it is evident that the increment of both mordant concentration and dyeing temperature enhances K/S values, suggesting a synergistic effect of these parameters on dye uptake. The reasons for this might be twofold. Firstly, the uses of mordant enhances dye-fiber bonding by forming coordination complexes [

7,

22]. In this case, tartaric acid not only acts as an acidic-mordant [

22,

24], but also a pH modifier which could influence not only the interaction between the indigo carmine and Alpaca fiber, but also the dyeing potential and color strength [

33]. A higher concentration may enhance washing fastness properties, but there is a risk of excessive product accumulation on the surface when a high concentration is applied. This suggests that sufficient tartaric acid concentration ensures adequate protonation of biding sites on Alpaca fiber, thereby promoting dye-fiber interaction [

7]. Secondly, higher temperature exerts a more pronounced effect with a noticeable rise. This high temperature enhances dye diffusion and reaction kinetics [

34], yet overly elevated temperatures risk partial dye degradation or altered fiber properties.

Figure 3b shows the variation curves of the color strength (K/S) values with the dyeing temperature and exhaust time when the mordant concentration was set to 4 g/L. In this context, a progressive increase in K/S that can be achieved not only at prolonged exhaust time, but also at a shorter time if the temperature is sufficiently elevated is observed. According to the topmost region of the surface plot, higher temperature suggests that temperature exerts a strong influence on dye diffusion and fixation, reflecting the combined influence of thermal energy and duration on dye-fiber interactions. However, the pronounced peak at shorter times indicates that higher temperatures can accelerate dye uptake and promote the rapid formation of dye-fiber bonds [

34,

35].

3.4. Process Optimization Results and Analysis

To obtain a higher color strength (K/S), an optimization analysis was performed using Design Expert® (v.13.0) software to determine the best dyeing process of Alpaca fiber with indigo carmine. The process parameters were selected using the ‘The-large-the-better’ method [

36]. This approach was adopted because the K/S value is directly correlated with the dye molecule concentration and the dyed fiber’s scattering value. A higher K/S value indicates higher absorption, which in turn indicates greater surface uptake [

27]. Under this criterion, the software proposed the following optimum design point, which is shown in

Table 4. In this, it is observed that desirability has a value very close to 1, i.e., 0.995 which indicates how well the combination of parameters has for the response variable.

To validate the optimization dyeing process, the confirmatory experiments were runner 3 times to ensures the repeatability.

Table 5 shows a comparison between the predicted and experimental value for the response variable (color strength, K/S).

According to the table, a difference between the predicted mean and observed (data mean) value is observed. In this case is, the observed value was lower than the predicted one with a percentage difference of 0.3026%. This suggests a strong agreement between experimental data and the prediction.

3.5. Color Fastness Properties of Dyed Alpaca Yarn Using Indigo Carmine

Table 6 presented the color fastness to rubbing and washing of Alpaca yarn dyed using indigo carmine. The dyeing process was carried out according to the optimized recipe (

Table 4) in order to find out the color fastness properties.

The rubbing and washing fastness results were evaluated according to the gray scale. In this context, it is seen that wet and dry rubbing fastness achieved a 3 and 3/4 rating, respectively, denoting a tolerable color fastness. It can be inferred that the dyeing process using indigo carmine withstands rubbing conditions since it does not present significant color transfer on the cotton witness, indicating good fixation of the dye molecules on the fiber [

25]. For washing fastness results, it seen for cotton (CO) and polyacrylic (PAN), it achieved a 4/5 rating. In the case of the other adjacent fibers, their achieved a rating of 5. This suggests a favorable interaction between the dye molecules and the Alpaca fiber surface. In addition, these findings are relevant for selecting materials to produce blended yarn fibers [

25].

4. Conclusions

Indigo carmine is an outstanding dye for Alpaca fiber. Response Surface Methodology (RSM) was used to enhance the dyeing conditions on the color strength (K/S) of dyed Alpaca yarns. This value was raised by the mordant concentration, dyeing temperature, and exhaust time where higher color strength values are the results of higher mordant concentration and dyeing temperature with lower exhaust time. Fastness properties for both washing and rubbing tests were tolerable showing a good color permanence and textile quality. In summary, this approach not only enhances the efficiency of the dyeing process but also presents significant findings for industrial-scale application for potential resource savings in textile production.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.M.L.-J. and E.M.J.; methodology, J.C.B and C.M.L.-J.; software, C.M.L.-J.; validation, E.M.J., J.C.B. and C.M.L.-J.; formal analysis, C.M.L.-J. and E.M.J.; investigation, E.G.-H., C.M.L.-J., E.M.J. and J.C.B.; data curation, C.M.L.-J. and J.C.B..; writing—original draft preparation, C.M.L.-J. and E.M.J.; writing—review and editing, C.M.L.-J., E.M.J. and E.G.-H.; visualization, C.M.L.-J. and E.M.J.; supervision, E.G.-H. and C.M.L.-J.; project administration, C.M.L.-J. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported and financed by the program PROCIENCIA from Consejo Nacional de Ciencia, Tecnología e Innovación Tecnológica (CONCYTEC), through Contract no. PE501084571-2023-PROCIENCIA

Data Availability Statement

The data are available in this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the “Centro de Innovación Productiva y Transferencia Tecnológica Textil Camélidos Arequipa” for allowing to conduct the dyeing process of Alpaca fiber and providing technical support and specialized equipment. We also extend the acknowledge to the “Centro Tecnológico de Textiles y Confecciones (CTTC)” for conducting the colorimetric evaluations of the dyed samples and providing technical assistance.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors of this article declare that they have no conflict of interest that could inappropriately influence their work. All materials, supplies, and all sources of information are properly referenced. The authors have no financial, personal or contractual relationship with other individuals or organizations that may present a conflict of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript; or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Atav, R.; Türkmen, F. Investigation of the Dyeing Characteristics of Alpaca Fibers (Huacaya and Suri) in Comparison with Wool. Textile Research Journal 2015, 85, 1331–1339. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, L. Mohair, Cashmere and Other Animal Hair Fibres. In Handbook of Natural Fibres: Second Edition; Elsevier Inc., 2020; Vol. 1, pp. 279–383 ISBN 9780128206669.

- Instituto Nacional de Calidad (INACAL) NTP 231.301: CLASSIFIED ALPACA FIBRE. Definitions, Classifications by Quality Requirements and Labelling Groups. INACAL 2022.

- Jara-Morante, E.; Luízar Obregón, C.; Bueno Lazo, A.; Castillo-Quispehuanca, Á. Alpaca Fiber Impregnated with Alizarine and Indigo Dyes in a Process Using Supercritical Carbon Dioxide. Journal of Supercritical Fluids 2023, 200. [CrossRef]

- Fobiri, G.K. Synthetic Dye Application in Textiles: A Review on the Efficacies and Toxicities Involved. Textile & Leather Review 2022, 5, 180–198. [CrossRef]

- Khodary, M. The Printability of Wool Fabric with Synthetic Food Dyes. International Design Journal 2024, 14, 241–247. [CrossRef]

- Rather, L.J.; Shabbir, M.; Ganie, S.A.; Zhou, Q.; Singh, K.P.; Li, Q. Natural Dyes: Green and Sustainable Alternative for Textile Colouration. In Sustainable Textile Chemical Processing; CRC Press: London, 2023; pp. 41–69.

- Yadav, S.; Tiwari, K.S.; Gupta, C.; Tiwari, M.K.; Khan, A.; Sonkar, S.P. A Brief Review on Natural Dyes, Pigments: Recent Advances and Future Perspectives. Results Chem 2023, 5.

- Siva, R. Status of Natural Dyes and Dye-Yielding Plants in India. Curr Sci 2007, 92.

- Rather, L.J.; Mir, S.S.; Ganie, S.A.; Shahid-ul-Islam; Li, Q. Research Progress, Challenges, and Perspectives in Microbial Pigment Production for Industrial Applications - A Review. Dyes and Pigments 2023, 210.

- Zahra, N.; Fatima, Z.; Kalim, I.; Saeed, K. Identification of Synthetic Food Dyes in Beverages by Thin Layer Chromatography. Pakistan Journal of Food Sciences 2015, 25, 178–181.

- Danila, A.; Muresan, E.I.; Chirila, L.; Coroblea, M. Natural Dyes Used in Textiles: A Review. In International Symposium “Technical Textiles - Present and Future”; Sciendo, 2022; pp. 52–59.

- Komboonchoo, S.; Bechtold, T. Natural Dyeing of Wool and Hair with Indigo Carmine (C.I. Natural Blue 2), a Renewable Resource Based Blue Dye. J Clean Prod 2009, 17, 1487–1493. [CrossRef]

- De Keijzer, M.; Van Bommel, M.R.; Hofmann-De Keijzer, R.; Knaller, R.; Oberhumer, E. Indigo Carmine: Understanding a Problematic Blue Dye. In Proceedings of the Studies in Conservation; 2012; Vol. 57.

- Ristea, M.E.; Zarnescu, O. Indigo Carmine: Between Necessity and Concern. J Xenobiot 2023, 13, 509–528. [CrossRef]

- Genázio Pereira, P.C.; Reimão, R.V.; Pavesi, T.; Saggioro, E.M.; Moreira, J.C.; Veríssimo Correia, F. Lethal and Sub-Lethal Evaluation of Indigo Carmine Dye and Byproducts after TiO2 Photocatalysis in the Immune System of Eisenia Andrei Earthworms. Ecotoxicol Environ Saf 2017, 143, 275–282. [CrossRef]

- Olas, B.; Białecki, J.; Urbańska, K.; Bryś, M. The Effects of Natural and Synthetic Blue Dyes on Human Health: A Review of Current Knowledge and Therapeutic Perspectives. Advances in Nutrition 2021, 12, 2301–2311. [CrossRef]

- Caprarescu, S.; Miron, A.R.; Purcar, V.; Radu, A.L.; Sarbu, A.; Ion-Ebrasu, D.; Atanase, L.I.; Ghiurea, M. Efficient Removal of Indigo Carmine Dye by a Separation Process. Water Science and Technology 2016, 74, 2462–2473. [CrossRef]

- Saleemi, S.; Mannan, H.A.; Riaz, T.; Hai, A.M.; Zeb, H.; Khan, A.K. Optimizing Synergistic Silica–Zinc Oxide Coating for Enhanced Flammability Resistance in Cotton Protective Clothing. Fibers 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

- Barani, H.; Rezaee, K. Optimization of Dyeing Process Using Achillea Pachycephala as a Natural Dye for Wool Fibers. Chiang Mai J. Sci 2017, 44, 1548–1561.

- Moiz, A.; Aleem Ahmed, M.; Kausar, N.; Ahmed, K.; Sohail, M. Study the Effect of Metal Ion on Wool Fabric Dyeing with Tea as Natural Dye. Journal of Saudi Chemical Society 2010, 14, 69–76. [CrossRef]

- İşmal, Ö.E.; Yildirim, L. Metal Mordants and Biomordants. In The Impact and Prospects of Green Chemistry for Textile Technology; Elsevier, 2018; pp. 57–82 ISBN 9780081024911.

- Deo, H.T.; Paul, R. Dyeing of Ecru Denim with Onion Extract. Using Natural Mordant Combinations. Indian J Fibre Text Res 2000, 25, 152–157.

- Deo ’, H.T.; Paul, R. Dyeing of Ecru Denim with Onion Extract as a Natural Dye Using Potassium Alum in Combination with Harda and Tartaric Acid; 2000; Vol. 25;

- Quispe-Quispe, A.; Lozano, F.; Pinche-Gonzales, L.M.; Vilcanqui-Perez, F. Evaluation of Alpaca Yarns Dyed with Buddleja Coriaceous Dye and Metallic Mordants. Fibers 2025, 13. [CrossRef]

- Carrasco Bocangel, J.; Sucasaca, A.; Sanchez-Gonzales, G.; Morán Flores, G.; Barriga-Sánchez, M. Estudio Preliminar de Teñido de Fibra de Alpaca Utilizando Extracto Acuoso de Molle (Schinus Molle) Como Pigmento Natural. Revista de Innovación y Transferencia Productiva 2022, 2, e003. [CrossRef]

- Samanta, P. Basic Principles of Colour Measurement and Colour Matching of Textiles and Apparels. In Colorimetry; IntechOpen, 2022.

- Montgomery, D.C. Design and Analysis of Experiments; 9th ed.; Wiley: New York, 2020; ISBN 978-1-119-63842-1.

- Steinberg, D.M.; Bursztyn, D. Dispersion Effects in Robust-Design Experiments with Noise Factors. Journal of Quality Technology 1994, 26, 12–20. [CrossRef]

- Becze, A.; Babalau-Fuss, V.L.; Varaticeanu, C.; Roman, C. Optimization of High-Pressure Extraction Process of Antioxidant Compounds from Feteasca Regala Leaves Using Response Surface Methodology. Molecules 2020, 25. [CrossRef]

- Liu, B.; Wu, Y.; Xing, Z.; Zhang, J.; Xue, Y. Optimization of Magnetic Biochar Preparation Process, Based on Methylene Blue Adsorption. Molecules 2024, 29. [CrossRef]

- Straume, M.; Johnson, M.L. [5] Analysis of Residuals: Criteria for Determining Goodness-of-Fit. In; 1992; pp. 87–105.

- Mamani, E. Efecto Del Teñido Natural Con Cúrcuma (Cúrcuma Longa) En La Solidez Del Color Del Hilado de Alpaca Para La Artesanía Textil, Puno 2020. Bachelor’s Thesis, Universidad Nacional de Juliaca, 2021.

- Ferus-Comelo, M. Thermodynamics and Kinetics of Dyeing and Dyebath Monitoring Systems. Handbook of Textile and Industrial Dyeing 2011, 1, 184–206.

- Clark, M. Fundamental Principles of Dyeing. In Handbook of Textile and Industrial Dyeing: Principles, Processes and Types of Dyes; Elsevier Inc., 2011; Vol. 1, pp. 3–27 ISBN 9780857093974.

- Saleemi, S.; Mannan, H.A.; Riaz, T.; Hai, A.M.; Zeb, H.; Khan, A.K. Optimizing Synergistic Silica–Zinc Oxide Coating for Enhanced Flammability Resistance in Cotton Protective Clothing. Fibers 2024, 12. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).