Submitted:

12 January 2025

Posted:

13 January 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Chemicals and Plant Material Collection

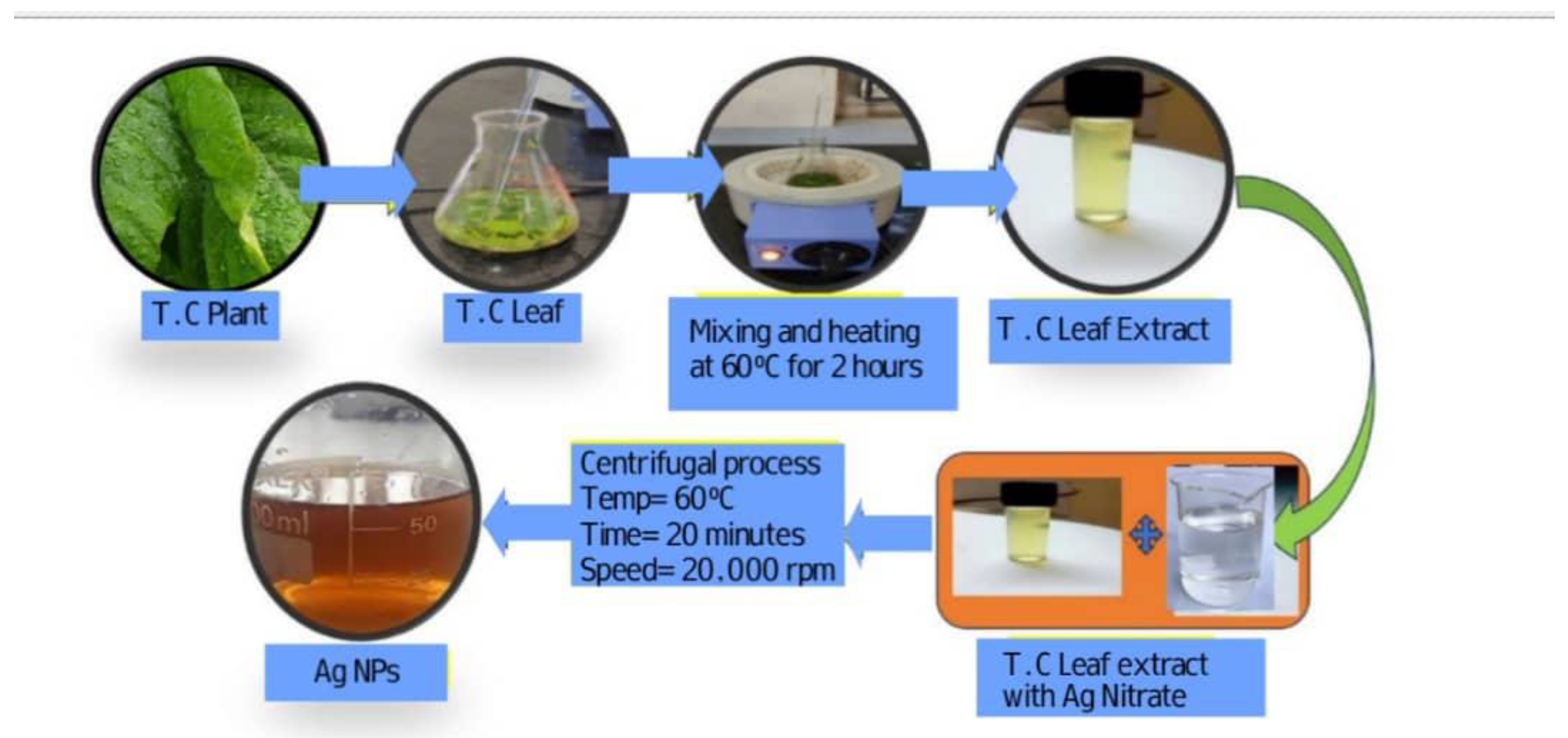

2.2. Biosynthesis of Ag NPs

2.3. Photocatalytic Experiments

2.4. Characterization of the Synthesized Ag NPs

3. Results and Discussion

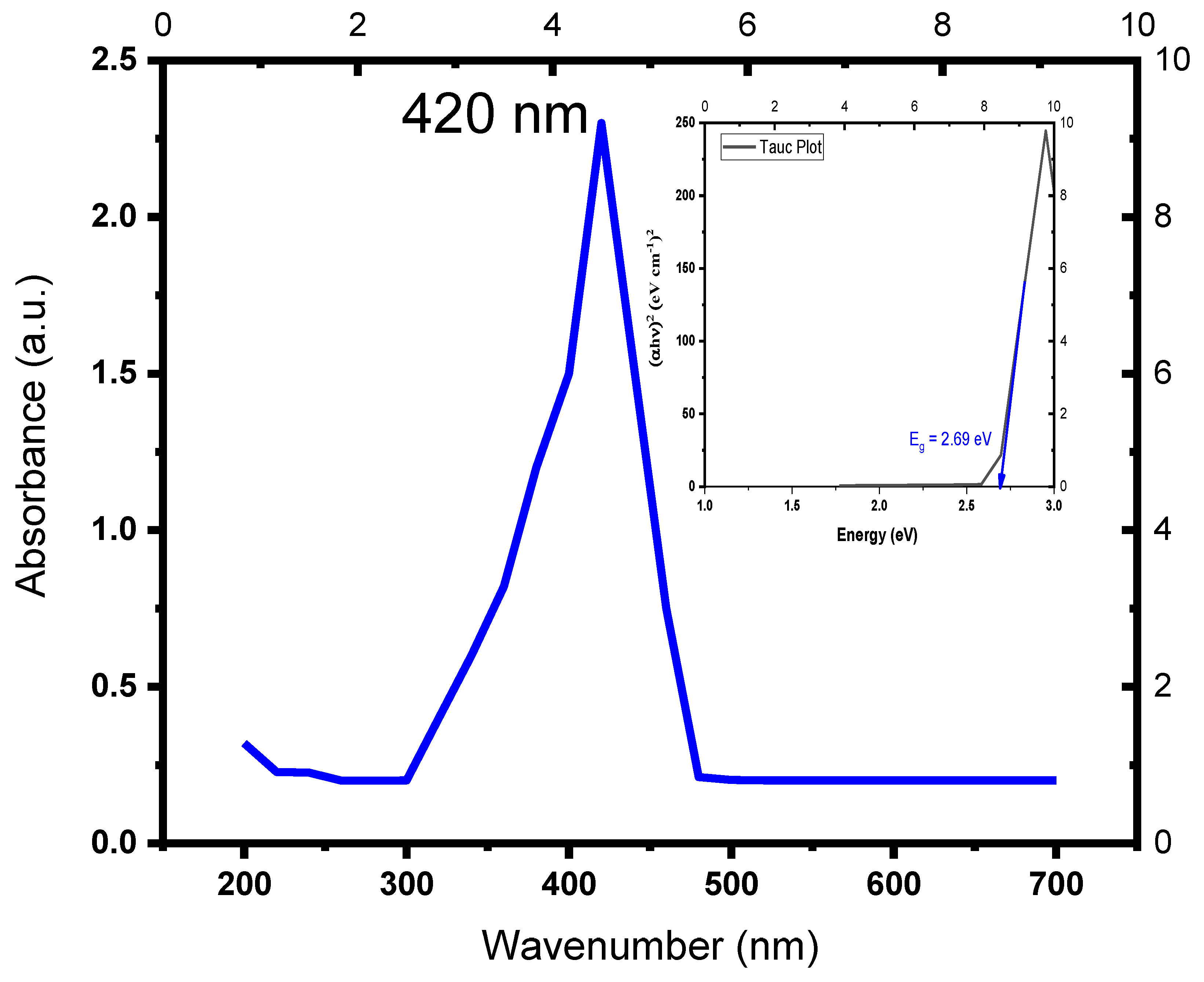

3.1. UV–Vis Absorption Spectroscopy Analysis

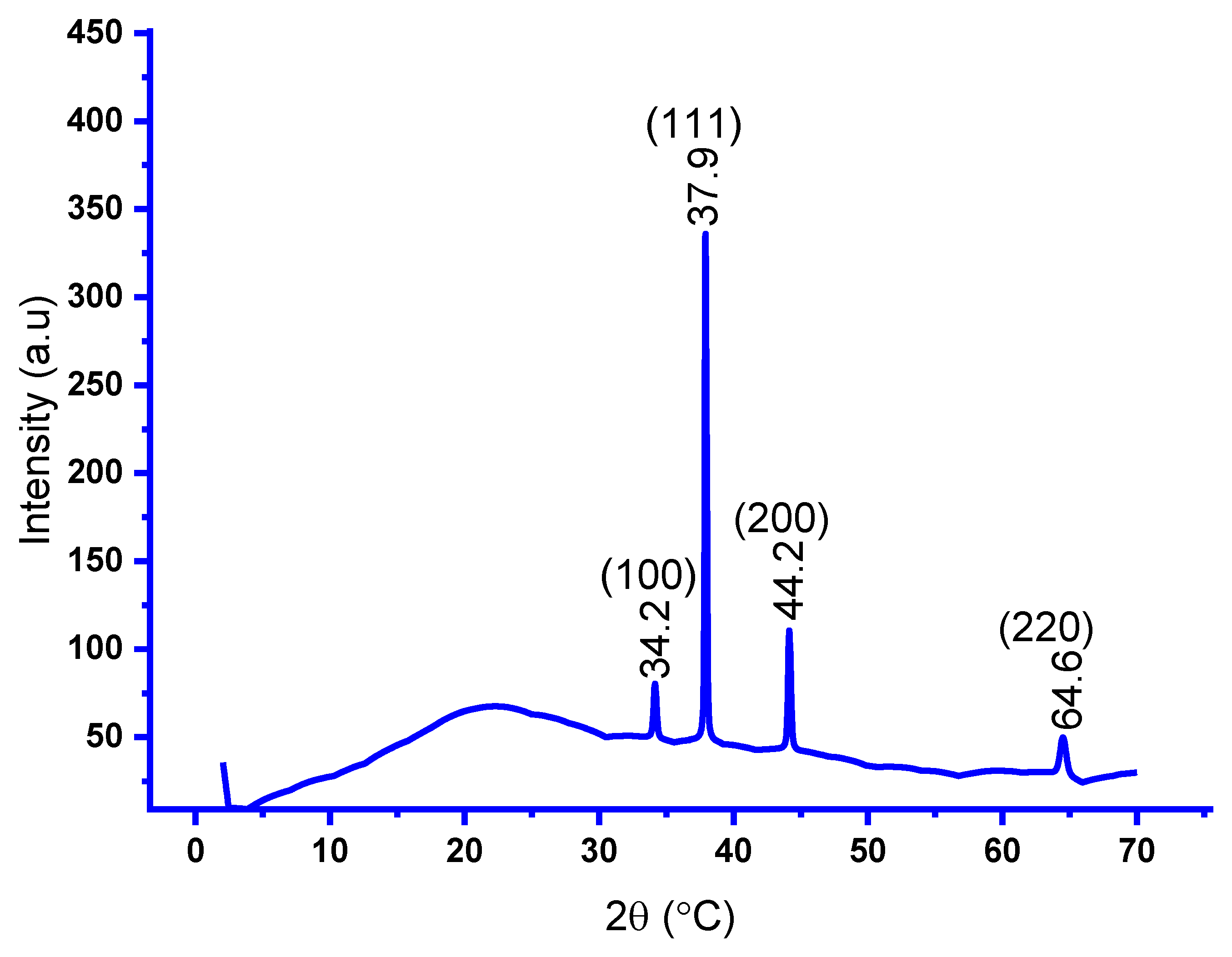

3.2. X-Ray Diffraction (XRD) Analysis

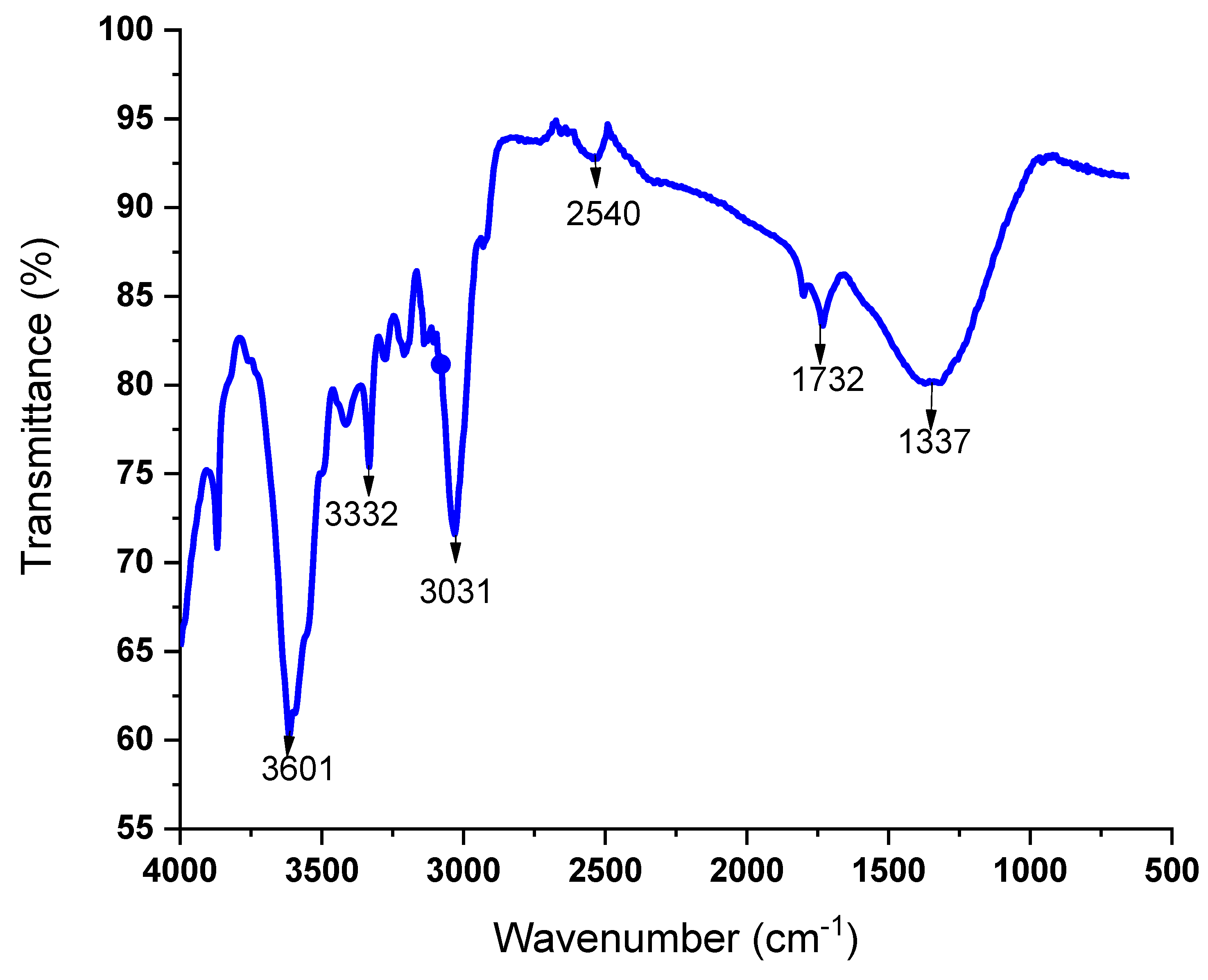

3.3. Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy (FT-IR) Analysis

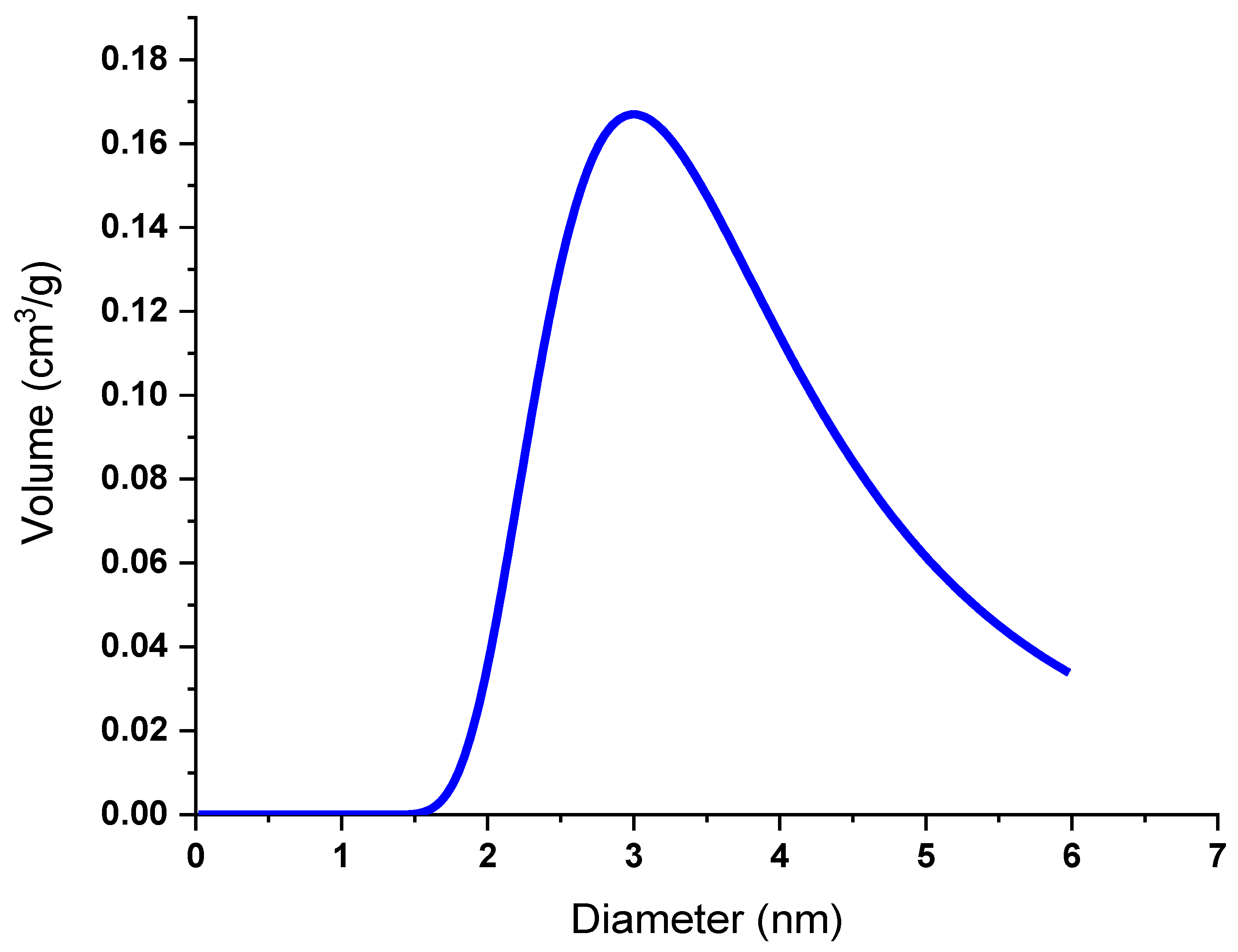

3.4. Brunauer-Emmett-Teller (BET) Analysis

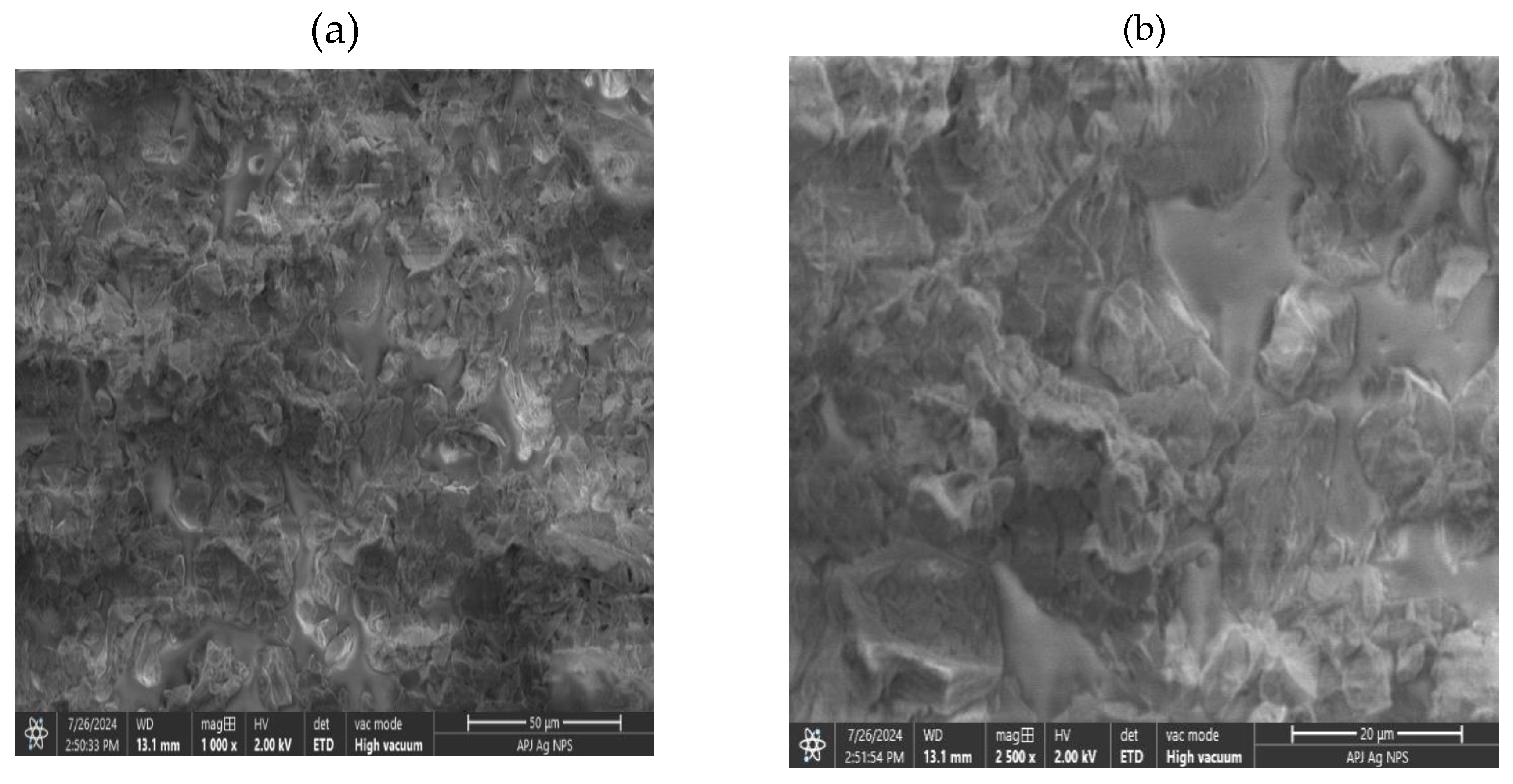

3.5. Scanning Electron Microscope (SEM) Analysis

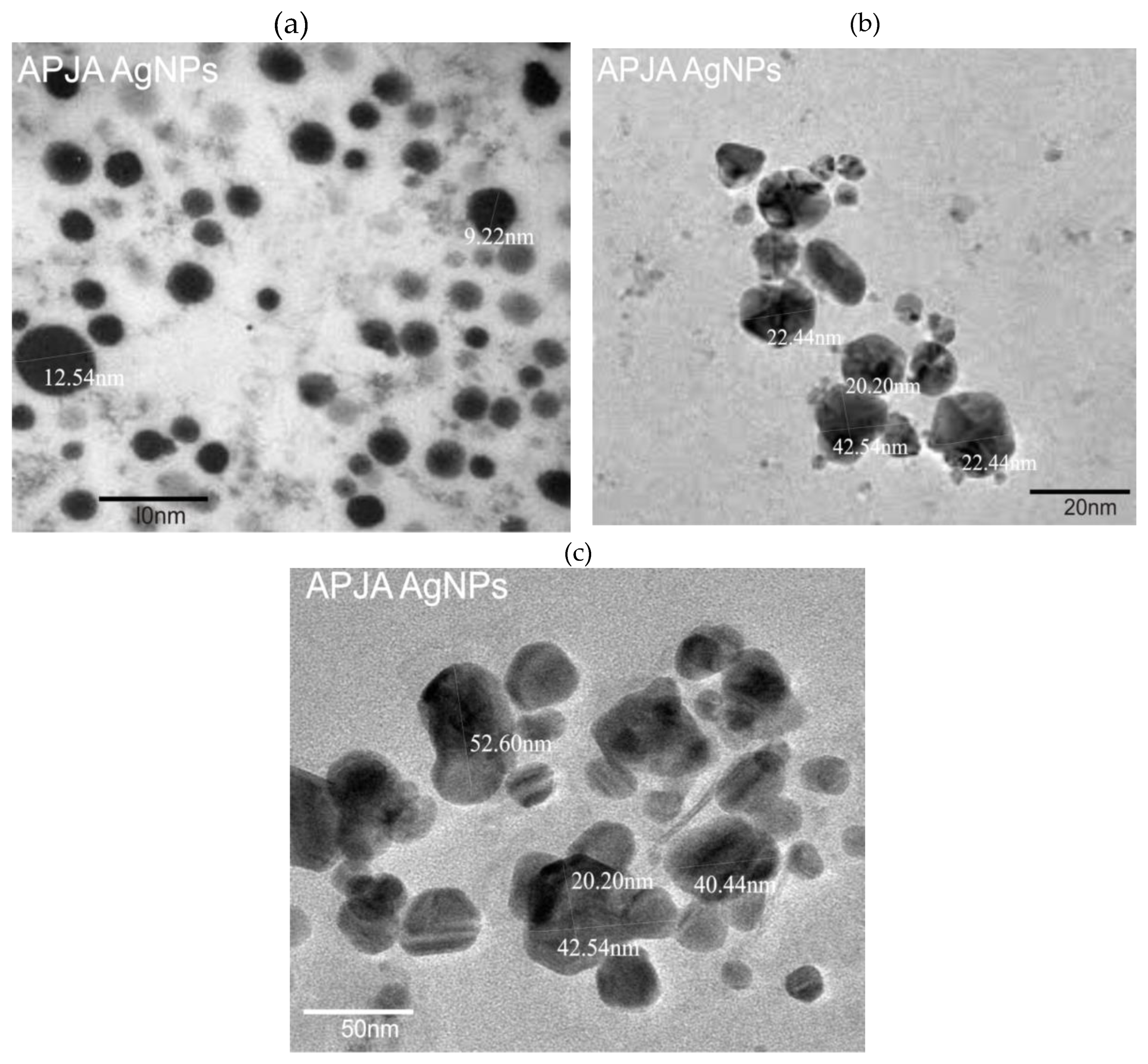

3.6. Transmission Electron Microscope (TEM) Analysis

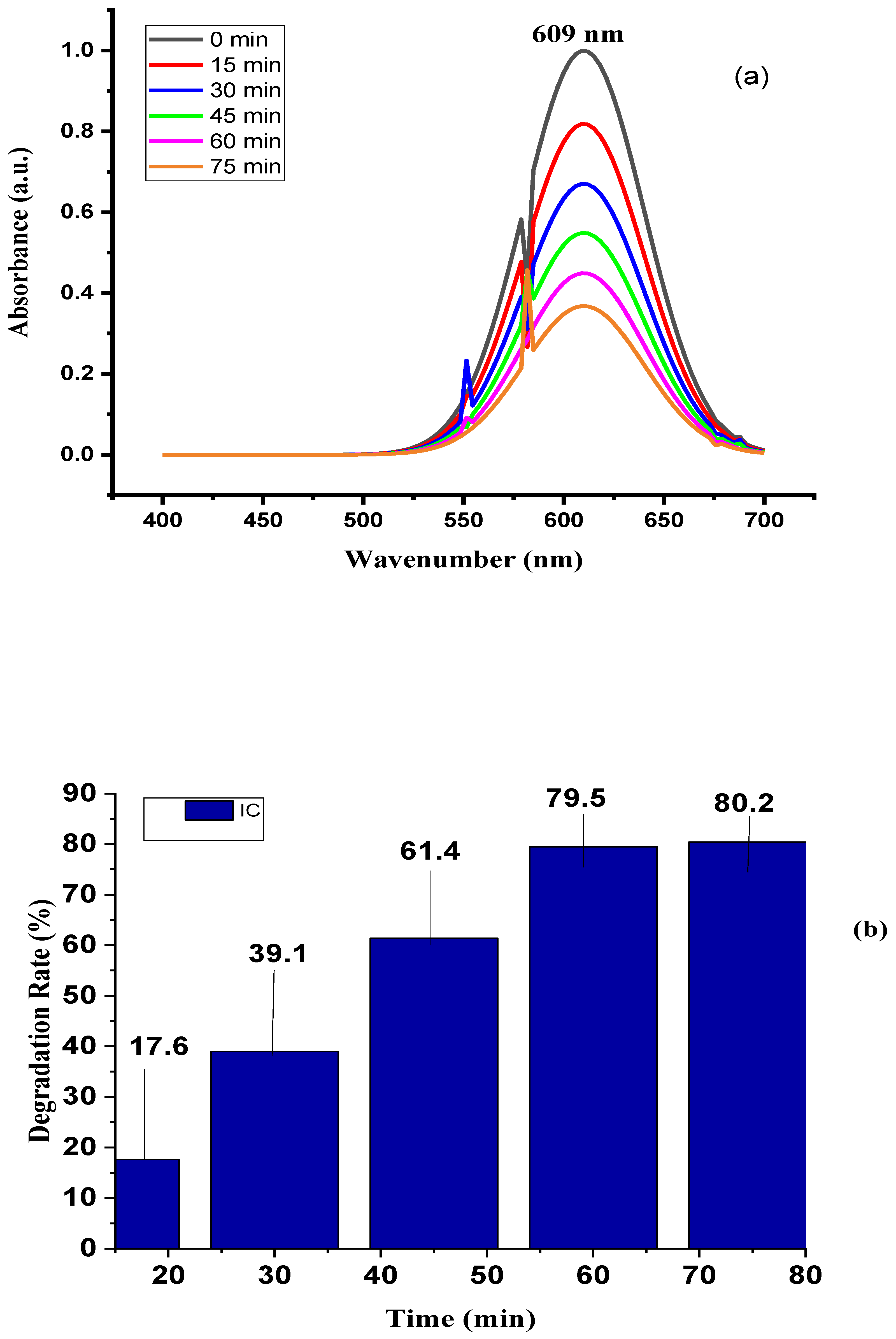

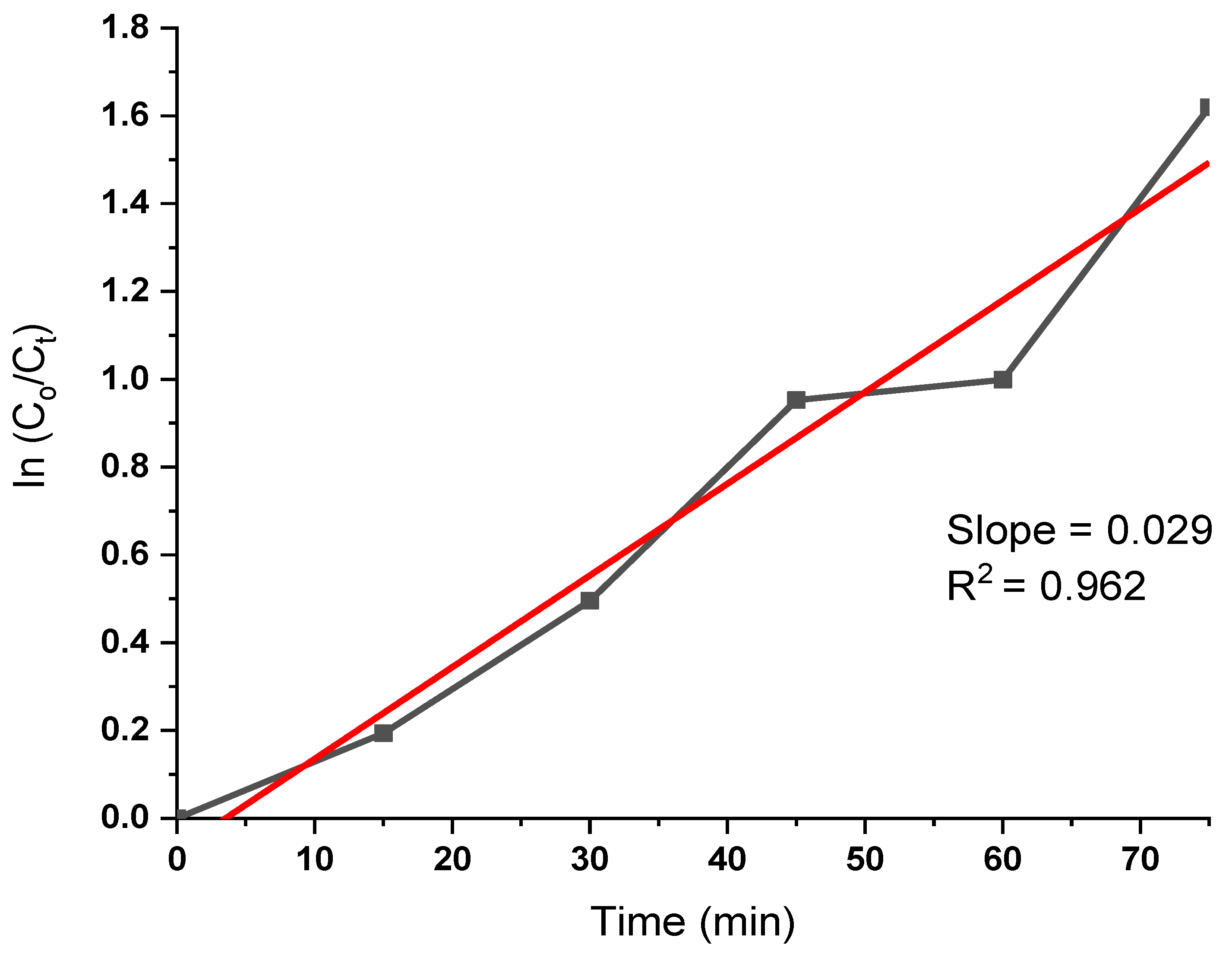

3.7. Analysis of Photocatalytic Activity

3.8. Conclusion

- According to FT-IR studies using an aqueous T. cacao leaf extract, the presence of plant-based nutrients such as proteins, flavonoids, alkaloid compounds, and phenolics, which act as surface-active substances, contributed to the stabilization of nanoparticles. These phytochemicals are associated with the outer layer of silver and play a role in stabilizing silver nanoparticles.

- XRD analysis revealed that the face-centered cubic plane of Ag NPs exhibited characteristic peak intensity patterns. TEM imaging of the Ag nanoparticles showed a size distribution ranging from 9.22 nm to 52.60 nm in diameter, with an average particle size of 28.52 nm determined through TEM analysis. The photocatalytic properties of the silver nanoparticles, specifically their ability to degrade harmful dyes in synthetic water, were evaluated through dye decomposition experiments. The findings indicate that the material achieved an 80.2% degradation efficiency at 75 minutes, with a half-life disintegration rate of 23.9 min-1. These results suggest that the biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles using T. cacao leaf extract is highly suitable for treating industrial effluents, particularly those containing pigments.

References

- El-Kammah, M., Elkhatib, E., Gouveia, S., Cameselle, C., Aboukil, E. (2022). Enhanced removal of Indigo Carmine dye from textile effluent using green cost-efficient nanomaterial: Adsorption, kinetics, thermodynamics and mechanisms. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 29: 100753. [CrossRef]

- Adel, M., Ahmed, M. A., Mohamed, A. A. (2021). Effective removal of indigo carmine dye from wastewaters by adsorption onto mesoporous magnesium ferrite nanoparticles. Environmental Nanotechnology, Monitoring & Management 16:100550. [CrossRef]

- Pereira, P. C. G., Reimão, R. V., Pavesi, T., Saggioro, E. M., Moreira, J. C., Correia, F. V. (2017). Lethal and sub-lethal evaluation of Indigo Carmine dye and byproducts after TiO2 photocatalysis in the immune system of Eisenia andrei earthworms. Ecotoxicology and Environmental Safety 143: 275–282. [CrossRef]

- Assemian, A. S., Kouassi, K. E., Drogui, P., Adouby, K., Boa, D. (2018). Removal of a Persistent Dye in Aqueous Solutions by Electrocoagulation Process: Modeling and Optimization Through. Water Air, and Soil Pollution 229: 184-197. [CrossRef]

- Odogu, A. N., Daouda, K., Keilah, L. P., Tabi, G. A., Rene, L. N., Nsami, N. J., Mbadcam, K. J (2020). Effect of doping activated carbon based Ricinodendron Heudelotti shells with AgNPs on the adsorption of indigo carmine and its antibacterial properties. Arabian Journal of Chemistry 13: 5241–5253. [CrossRef]

- Agnieszka, B, Monika, O-N & Monika, K. (2021). Methods of Dyes Removal from Aqueous Environment. Journal of Ecological Engineering 22(9), 111–118. [CrossRef]

- Devatha CP, Jagadeesh K, Patil M (2018) Effect of Green synthesized iron nanoparticles by Azardirachta Indica in different proportions on antibacterial activity. Environ Nanotechnol Monit Manag 9:85–94. [CrossRef]

- Raghavendra VB, Shankar S, Govindappa M, et al (2022) Green synthesis of zinc oxide nanoparticles (ZnO NPs) for effective degradation of dye, polyethylene and antibacterial performance in waste water treatment. J Inorg Organomet Polym Mater 1–17. [CrossRef]

- Abdelghaffar, F. (2021). Biosorption of anionic dye using nanocomposite derived from chitosan and silver Nanoparticles synthesized via cellulosic banana peel bio-waste. Environmental Technology & Innovation 24 (2021) 101852. [CrossRef]

- Ankita, M., Ashish, T., Srikanta, M., Subhendu, C., Susnata, S. M., Arijit, M., Suddhasattya, D., & Prakash, C. (2024). Silver nanoparticle for biomedical applications. A review Hybrid Advances, Volume 6. [CrossRef]

- Anita, D., Suresh, C., M., Sheetal, S., & Rohini, T.(2023). A review on biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their potential applications. Results in Chemistry, Volume 6. [CrossRef]

- Sapana, J., Rizwan, A., Nirmala, K. J., & Rajesh, K. M. (2021). Green synthesis of nanoparticles using plant extracts. Environmental Chemistry Letters 19(1), 355-374. [CrossRef]

- Anita, D., Suresh, C., M., Sheetal, S., & Rohini, T.(2023). A review on biological synthesis of silver nanoparticles and their potential applications. Results in Chemistry, Volume 6. [CrossRef]

- Ong, W. T. J., & Nyam, K. L. (2022). Evaluation of silver nanoparticles in cosmeceutical and potential biosafety complications. Saudi journal of biological sciences, 29(4), 2085–2094. [CrossRef]

- Kwon, Y. M., Cho, E. S., Kim, K. W., Chung, D., Bae, S. S., Yu, W. J., Kim, J. Y. H., & Choi, G. (2023). Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Aggregatimonas sangjinii F202Z8T and Their BiologicalCharacterization.Microorganisms,11(12),2975. [CrossRef]

- Leena, V. H., Sharanabasava, V. G., Veerabhadragouda, B. P., Sahana, N., & Aishwarya, H. Anticancer potential of biologically synthesized silver nanoparticles using Lantana camara leaf extract. Progress in Biomaterials 12 (2), 155-169. [CrossRef]

- S.S. Shankar, A. Rai, A. Ahmad, M.J. Sastry, Rapid synthesis of Au, Ag and bimetallic Au shell nanoparticles using Neem, J. Colloid Interface Sci. 275 (2004) 496–502. [CrossRef]

- H. Schneidewind, T. Schuler, K.K. Strelau, K. Weber, D. Cialla, M. Diegel, The mor- phology of silver nanoparticles prepared by enzyme-induced reduction, Beilstein J. Nanotechnol. 3 (2012) 404–414. [CrossRef]

- G.M. Sulaiman, W.H. Mohammed, T.R. Marzoog, A.A. Al-Amiery, A.A. Kadhum, A.B. Mohamad, G. Bagnati, Green synthesis, antimicrobial and cytotoxic effects of silver nanoparticles using Eucalyptus chapmaniana leaves extract, Asian Pac. J. Trop Biomed. 3 (2013) 58–63. [CrossRef]

- P. Kouvaris, A. Delimitis, V. Zaspalis, D. Papadopoulos, S.A. Tsipas, N. Michailidis, Green synthesis and characterization of silver nanoparticles produced using Arbutus unedo leaf extract, Mater. Lett. 76 (2012) 18–20. [CrossRef]

- Ashwani, K., Nirmal, P., Mukul, K., Anina, J., Vidisha,T., Emel, O., Charalampos, P., Maomao, Z., Tahra, E., Sneha, K., & Fatih, O. (2023). Major Phytochemicals: Recent Advances in Health Benefits and Extraction Method. [CrossRef]

- S. Patil, R. Sivaraj, P. Rajiv, R. Venckatesh, and R. Seenivasan, “Green synthesis of silver nanoparticle from leaf extract of Aegle marmelos and evaluation of its antibacterial activity,” International Journal of Pharmacy and Pharmaceutical Sciences, vol. 7, no. 6, pp. 169–173, 2015.

- Mahiuddin Md., Saha P and Ochiai B. 2020. “Green Synthesis and Catalytic Activity of Silver Nanoparticles Based on Piper chaba Stem Extracts.” Nanomaterials 10: 1777. [CrossRef]

- De Souza, D. C., Matos, V. A. F., Dos Santos, V. O. A., Medeiros, I. F., Marinho, C. S. R., Nascimento, P. R. P., Dorneles, G. P., Peres, A., Müller, C. H., Krause, M., Costa, E. C., & Fayh, A. P. T. (2018). Effects of high-intensity interval and moderate-intensity continuous exercise on inflammatory, leptin, IgA, and lipid peroxidation responses in obese males. Frontiers in Physiology, 9, 567. [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez-Félix, F., Graciano-Verdugo, A.Z., Moreno-Vásquez, M.J., Lagarda-Díaz, I., Barreras-Urbina, C.G., Armenta-Villegas, L., Olguín-Moreno, A., & Tapia-Hernández, J.A. (2022). Trends in Sustainable Green Synthesis of Silver Nanoparticles Using Agri-Food Waste Extracts and Their Applications in Health. Journal of Nanomaterials. [CrossRef]

- Abbas, R., Luo, J., Qi, X., Naz, A., Khan, I.A., Liu, H., Yu, S., & Wei, J. (2024). Silver Nanoparticles: Synthesis, Structure, Properties and Applications. Nanomaterials, 14. [CrossRef]

- Ghubish, Z., Kamal, R., Mahmoud, H.R., Saif, M., Hafez, H., & El-Kemary, M.A. (2022). Photocatalytic activation of Ag-doped SrSnO3 nanorods under visible light for reduction of p-nitrophenol and methylene blue mineralization. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 33, 24322 - 24339. [CrossRef]

- El-Desouky, N., Shoueir, K.R., El-Mehasseb, I.M., & El-Kemary, M.A. (2022). Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using bio valorization coffee waste extract: photocatalytic flow-rate performance, antibacterial activity, and electrochemical investigation. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 1 - 15. [CrossRef]

- El-Shabasy, R.M., Yosri, N., El-Seedi, H.R., Shoueir, K.R., & El-Kemary, M.A. (2019). A green synthetic approach using chili plant supported Ag/Ag O@P25 heterostructure with enhanced photocatalytic properties under solar irradiation. Optik. [CrossRef]

- Sengupta, A., & Sarkar, A. (2022). Synthesis and characterization of nanoparticles from neem leaves and banana peels: a green prospect for dye degradation in wastewater. Ecotoxicology, 31, 537 - 548. [CrossRef]

- Thatikayala, D., Jayarambabu, N., Banothu, V., Ballipalli, C.B., Park, J., & Rao, K.V. (2019). Biogenic synthesis of silver nanoparticles mediated by Theobroma cacao extract: enhanced antibacterial and photocatalytic activities. Journal of Materials Science: Materials in Electronics, 30, 17303 - 17313. [CrossRef]

- Miri, A., Shahraki Vahed, H.O., & Sarani, M. (2018). Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles and their role in photocatalytic degradation of methylene blue dye. Research on Chemical Intermediates, 44, 6907-6915. [CrossRef]

- Samuel MS, Jose S, Selvarajan E, Mathimani T, Pugazhendhi A (2020) Biosynthesized silver nanoparticles using Bacillus amyloliquefaciens; application for cytotoxicity effect on A549 cell line and photocatalytic degradation of p-nitrophenol. J Photochem Photobiol B: Biol 202 111642. [CrossRef]

- El-Shabasy R, Yosri N, El-Seedi H, Shoueir K, El-Kemary M (2019) A green synthetic approach using chili plant supported Ag/ Ag2O@ P25 heterostructure with enhanced photocatalytic proper- ties under solar irradiation. Optik 192 162943. [CrossRef]

- Singh J, Mehta A, Rawat M, Basu S (2018) Green synthesis of silver nanoparticles using sun dried tulsi leaves and its catalytic application for 4-nitrophenol reduction. J Environ Chem Eng 6(1):1468–1474. [CrossRef]

- El-Desouky, N., Shoueir, K.R., El-Mehasseb, I.M., & El-Kemary, M.A. (2022). Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using bio valorization coffee waste extract: photocatalytic flow-rate performance, antibacterial activity, and electrochemical investigation. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 1 - 15. [CrossRef]

- Veisi H, Azizi S, Mohammadi P (2018) Green synthesis of the silver nanoparticles mediated by Thymbra spicata extract and its application as a heterogeneous and recyclable nanocatalyst for catalytic reduction of a variety of dyes in water. J Clean Prod 170:1536–1543. [CrossRef]

- El-Desouky, N., Shoueir, K.R., El-Mehasseb, I.M., & El-Kemary, M.A. (2022). Synthesis of silver nanoparticles using bio valorization coffee waste extract: photocatalytic flow-rate performance, antibacterial activity, and electrochemical investigation. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery, 1 - 15. [CrossRef]

| Photocatalyst type | Pollutant type | Waste type | Time (min) | Efficiency (%) | References |

| Ag NPs | Bacillus amyloliquefaciens (MSR5) | 4- nitrophenol | 15 | 98 | [36] |

| Ag/Ag2O/P25 | Capsicum annuum L (chili) | 2-.4DNA | 60 | 100 | [37] |

| Ag NPs | tulsi leaves | 4- nitrophenol | 30 | 100 | [38] |

| Ag NPs | Coffee waste | Phenol | [39] | ||

| Ag NPs | Thymbra spicata/leaves | 4 nitrophenol | 1 | 96 | [40] |

| Ag NPs | Coffee waste | 2,4 DNA | 30 | 97.7 | [41] |

| Ag NPs | Theobroma cacao | Indigo carmine | 75 | 80.2 | Current work |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).