Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

- -

- Minimizing resource consumption through efficiency and conservation.

- -

- Enhancing the circularity of resource use and creating sustainable value chains.

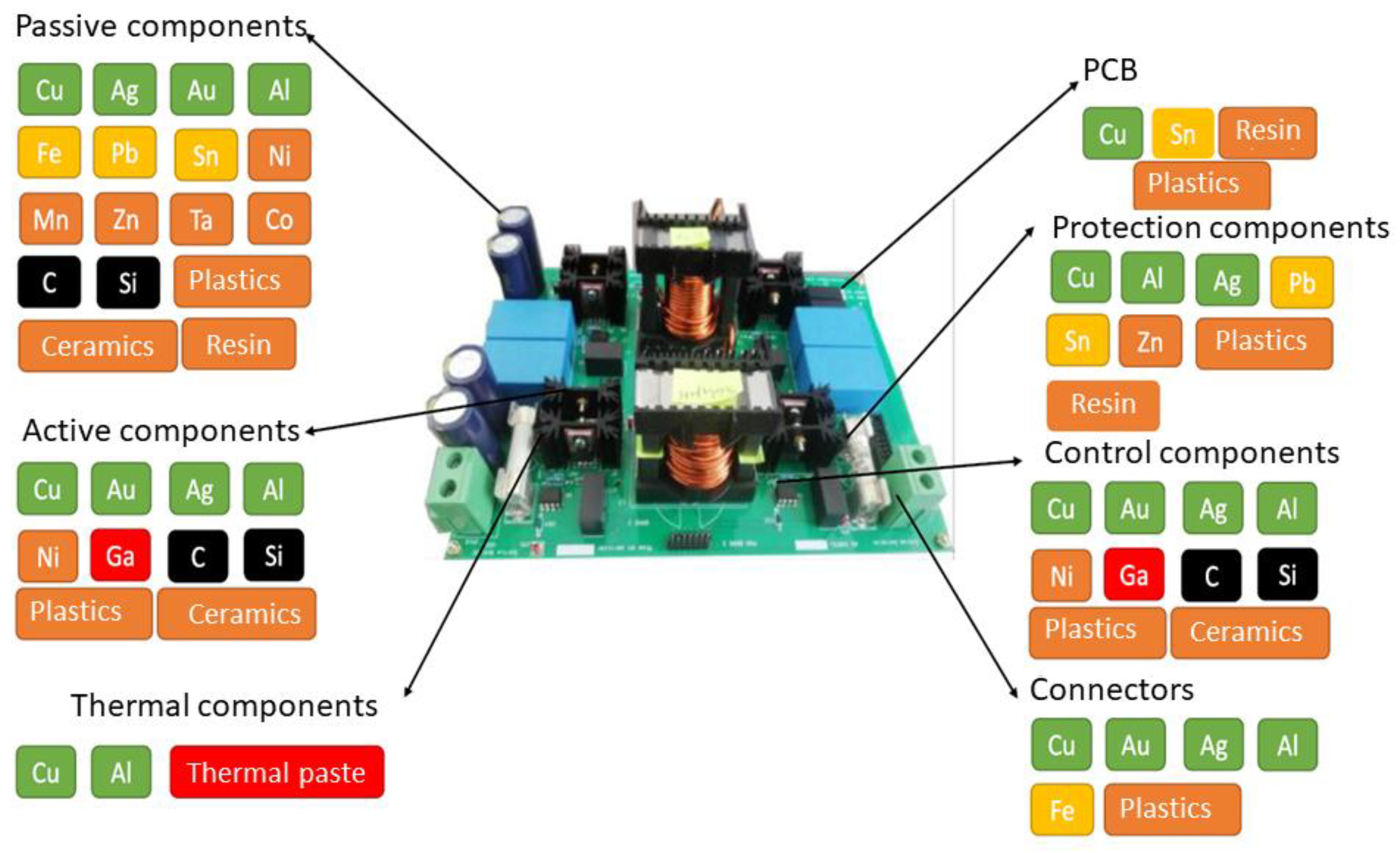

- The first part presents context, analyzes residual value calculations in other electrical engineering fields related to power electronics, and proposes a residual value formula for electronic components or power converter sub-systems. The parameters needed to calculate the residual value will be detailed in the next two parts with a specific focus on two crucial parameters.

- The second part deals with the residual value parameter of remaining useful life. It proposes a method to monitor online the remaining life of components to inform the residual value formula and make end-of-life decisions.

- The third part deals with the residual value parameter of reusability rate of a component in an electronic set. This part proposes experimental protocols to measure reusability rates through aging evaluations of the extraction process.

2. Definition of the Residual Value in Power Electronics

2.1. Residual Value in the Automotive Sector

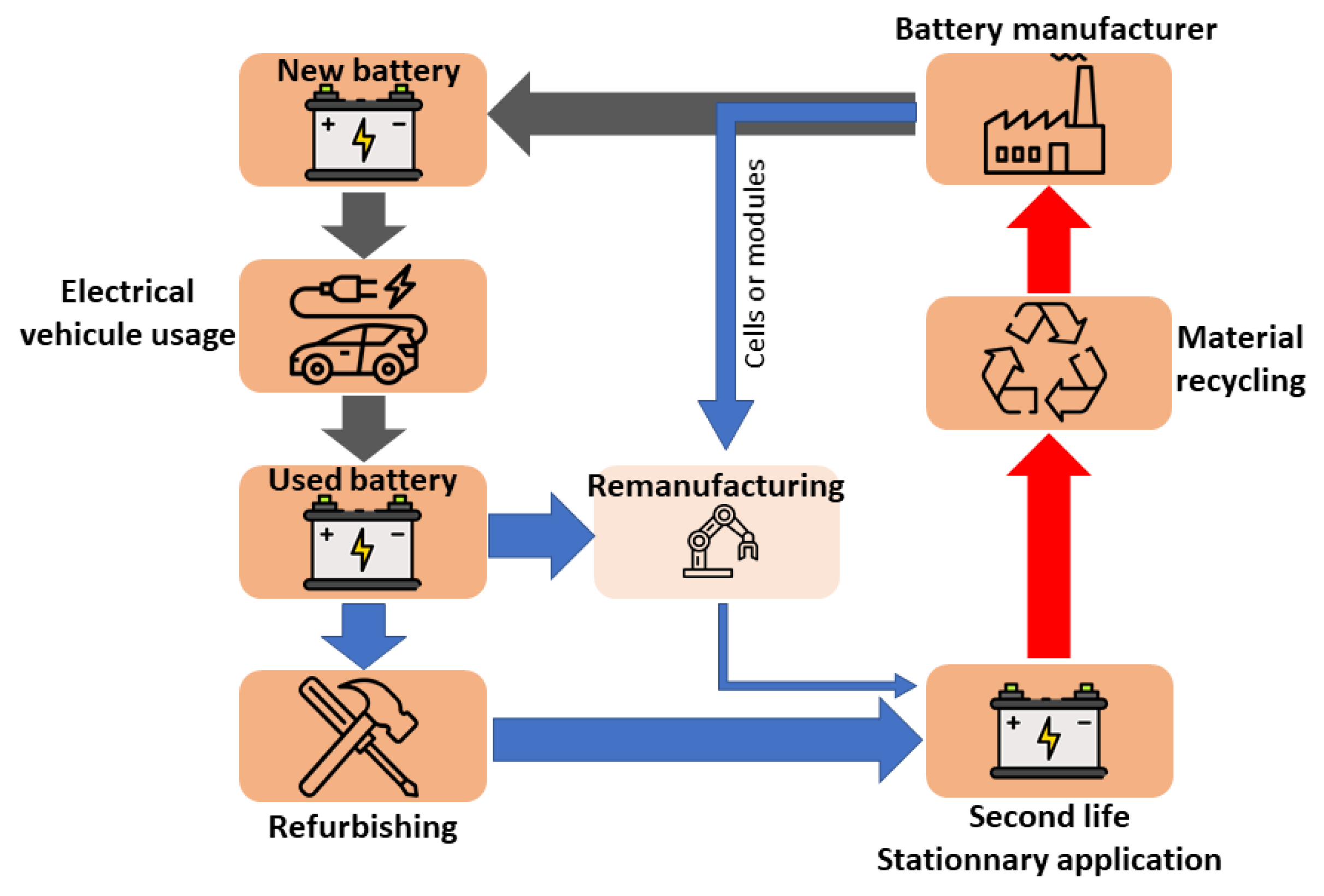

2.2. Residual Value in Battery Industry

2.3. Definition of Residual Value in Power Electronics

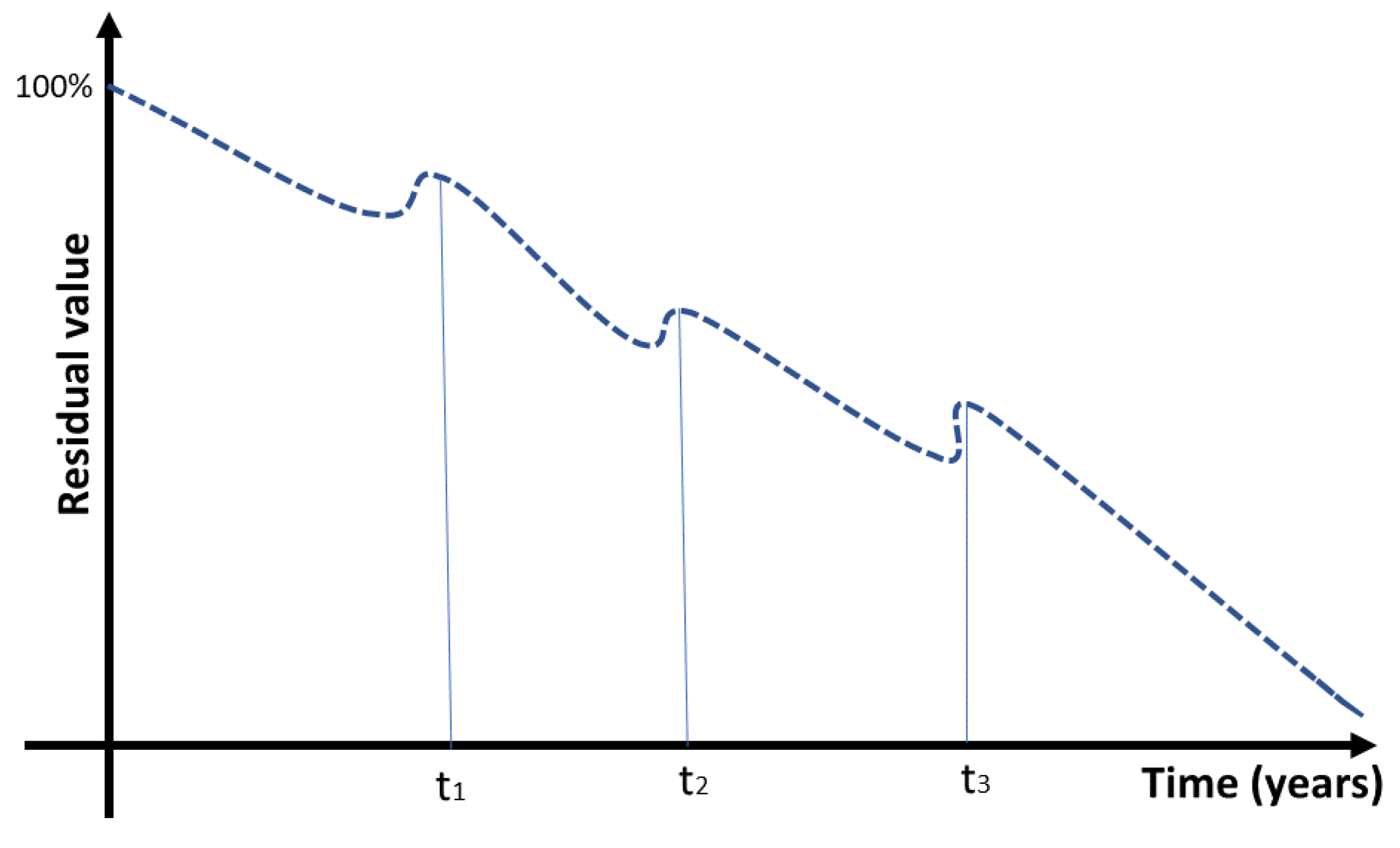

- Residual value is based on usage time and the remaining operational life, following a depreciation model linked to reliability.

- Requalification process costs are additional costs that reduce monetary value but increase functional residual value.

- If the extraction of a component or module from its converter is impossible or would cause damage, its value is considered zero.

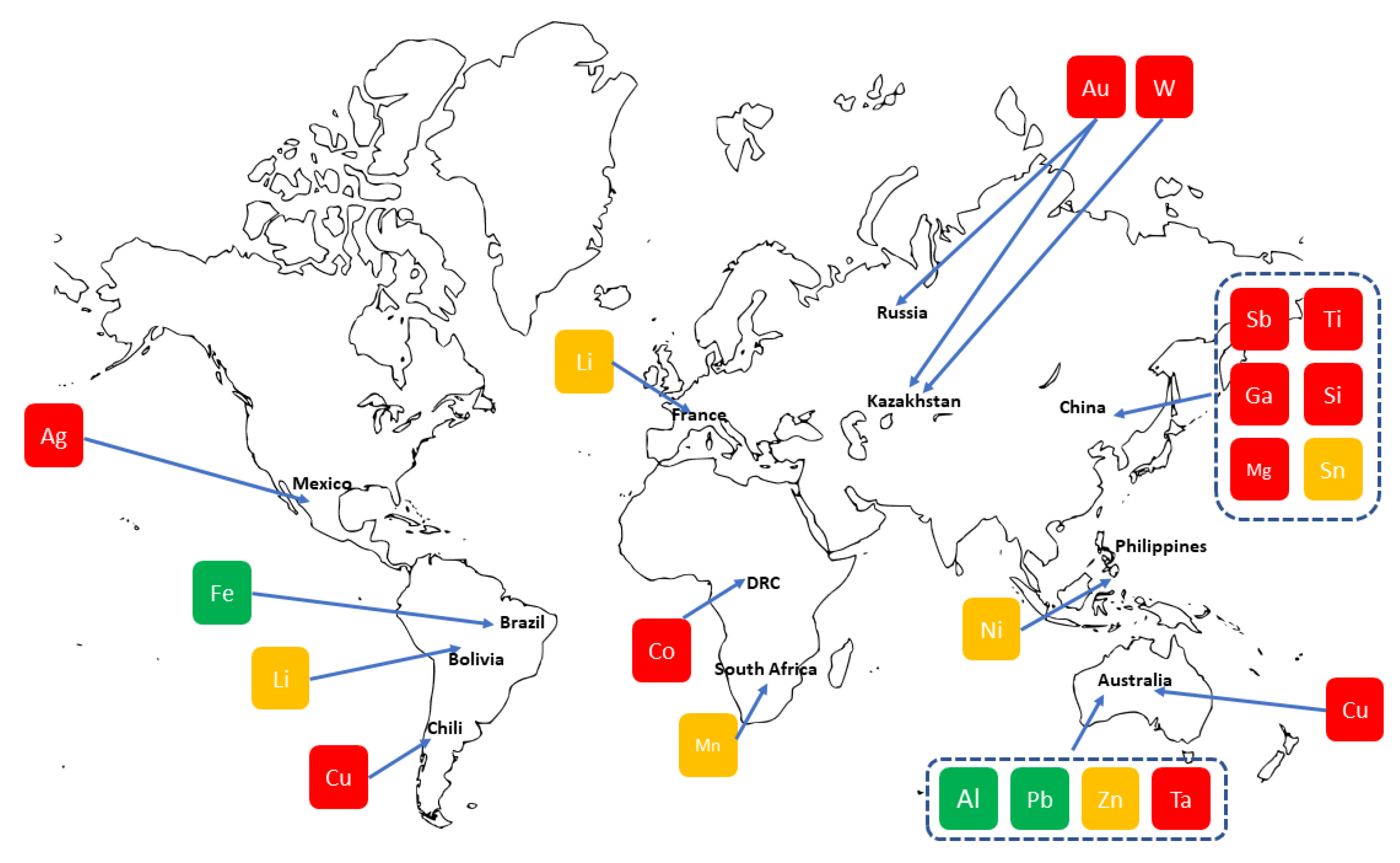

- The value can be adjusted by a correction factor during singular events related to socio-economic context and supply difficulties (e.g. geopolitical constraints).

3. Monitoring of the Remaining Lifetime

3.1. Basics of Physics of Failure

- ○

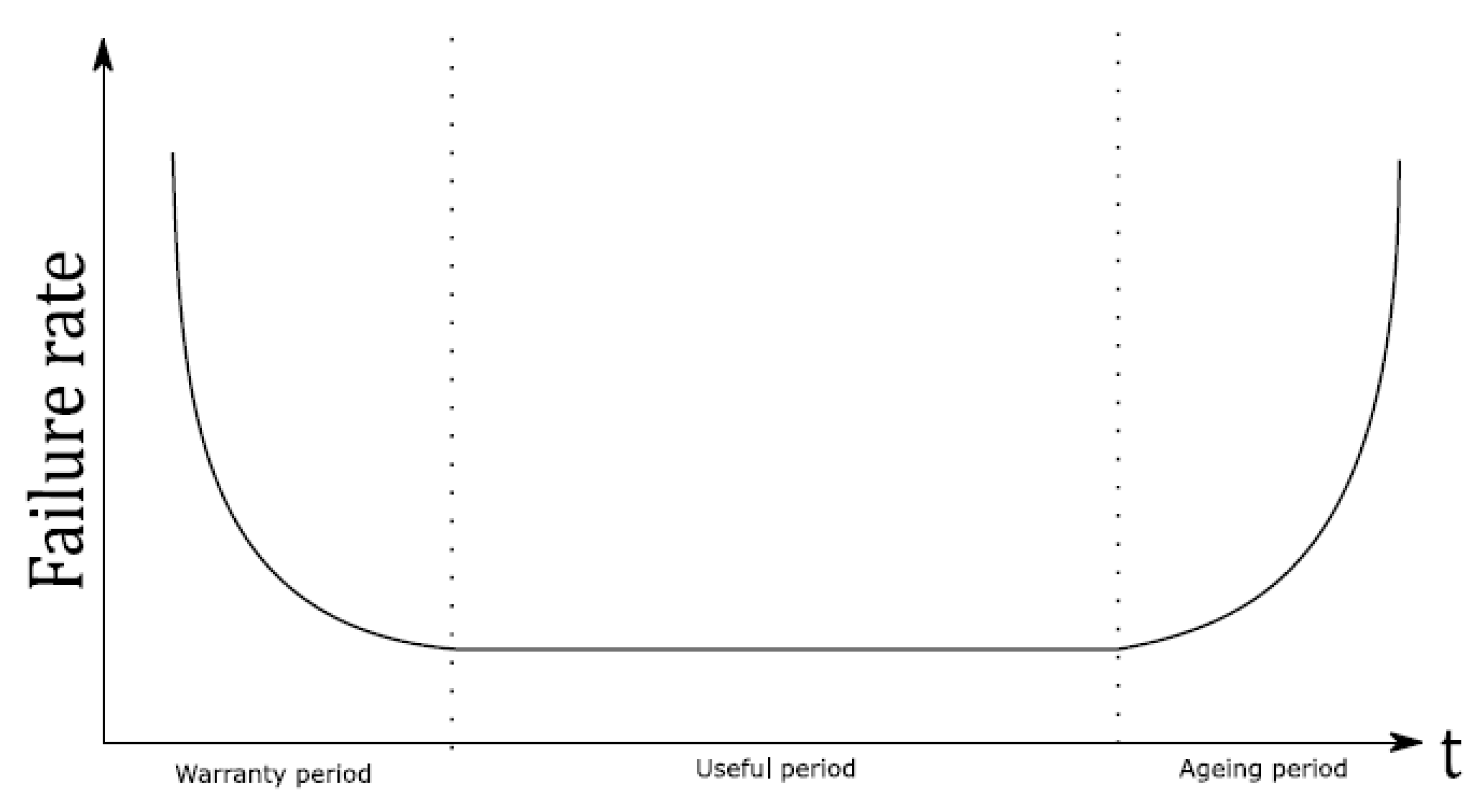

- Warranty period: Failures occurring during this period are typically due to manufacturing defects and are not considered in reliability studies. For instance, photovoltaic module manufacturers typically guarantee 5 years against mechanical failures.

- ○

- Useful life period: This represents the majority of a product’s life, where fatigue and wear have not yet significantly impacted the component.

- ○

- End-of-life period: Failure rate increases rapidly during this phase due to wear-out phenomena.

3.2. Failure Mechanisms

3.2. Lifetime Monitoring Methods

3.3. Temperature-Based Models for Lifetime Monitoring

- Universal lifespan estimation: the method must be able to evaluate the remaining lifespan of all components.

- Easy integration: the method should be lightweight and not add unnecessary sensors to all components.

- Standardized system approach: the approach should be based on standardized systems that are produced on a large scale.

- State observer creation: a detailed study should allow the creation of an observer that links the thermal parameters of each component to the operational conditions of the converter.

- Embedded observers: the state observer can be embedded in the converter, evaluating the remaining lifespan in real time, avoiding the need to store the mission profile.

- Minimal sensor addition: to minimize costs and maintain reliability, no additional sensors (or very few) should be added to the system.

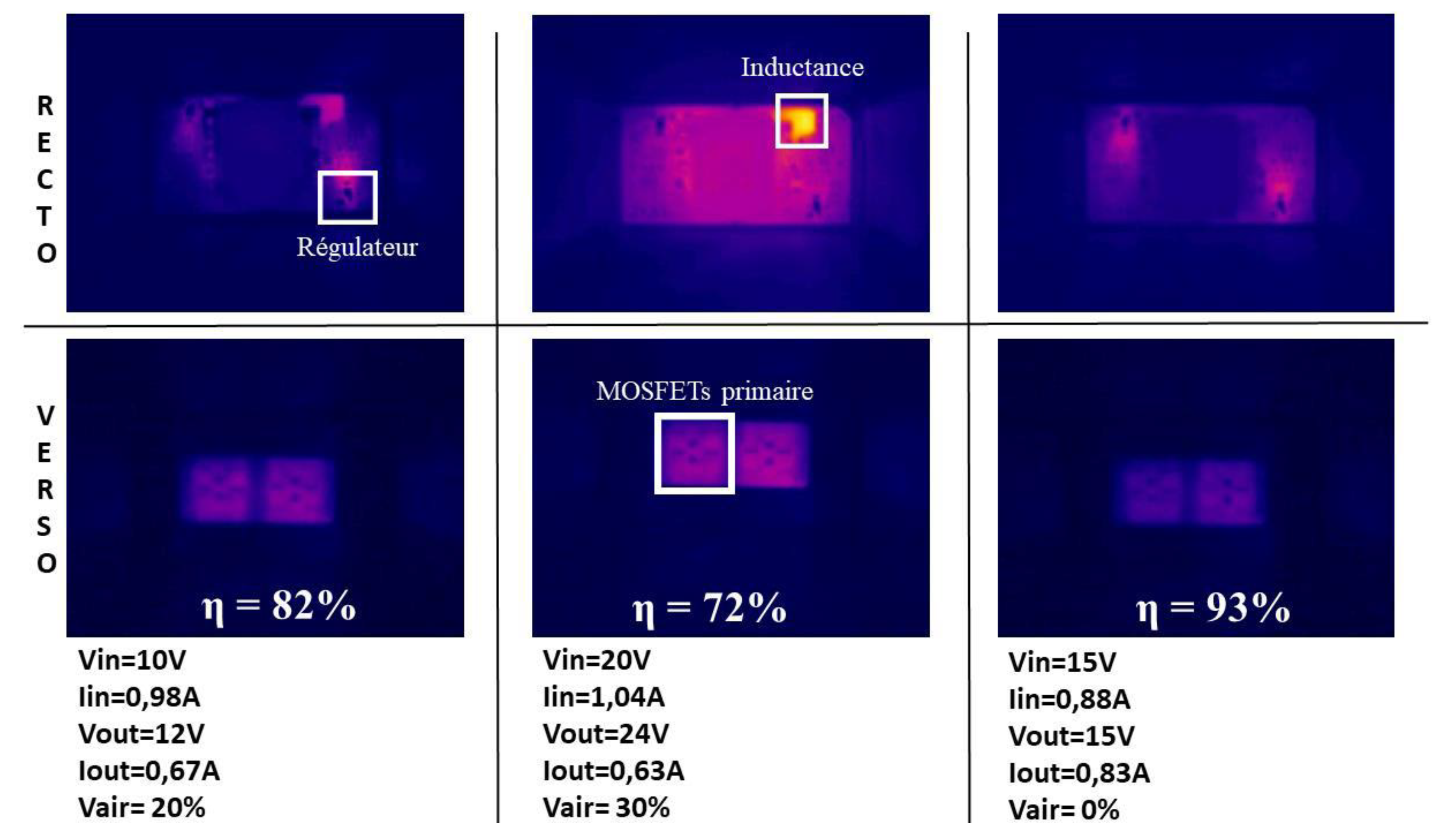

- Data collection of temperature: data is collected through thermal imaging and test benches to replicate real operational conditions.

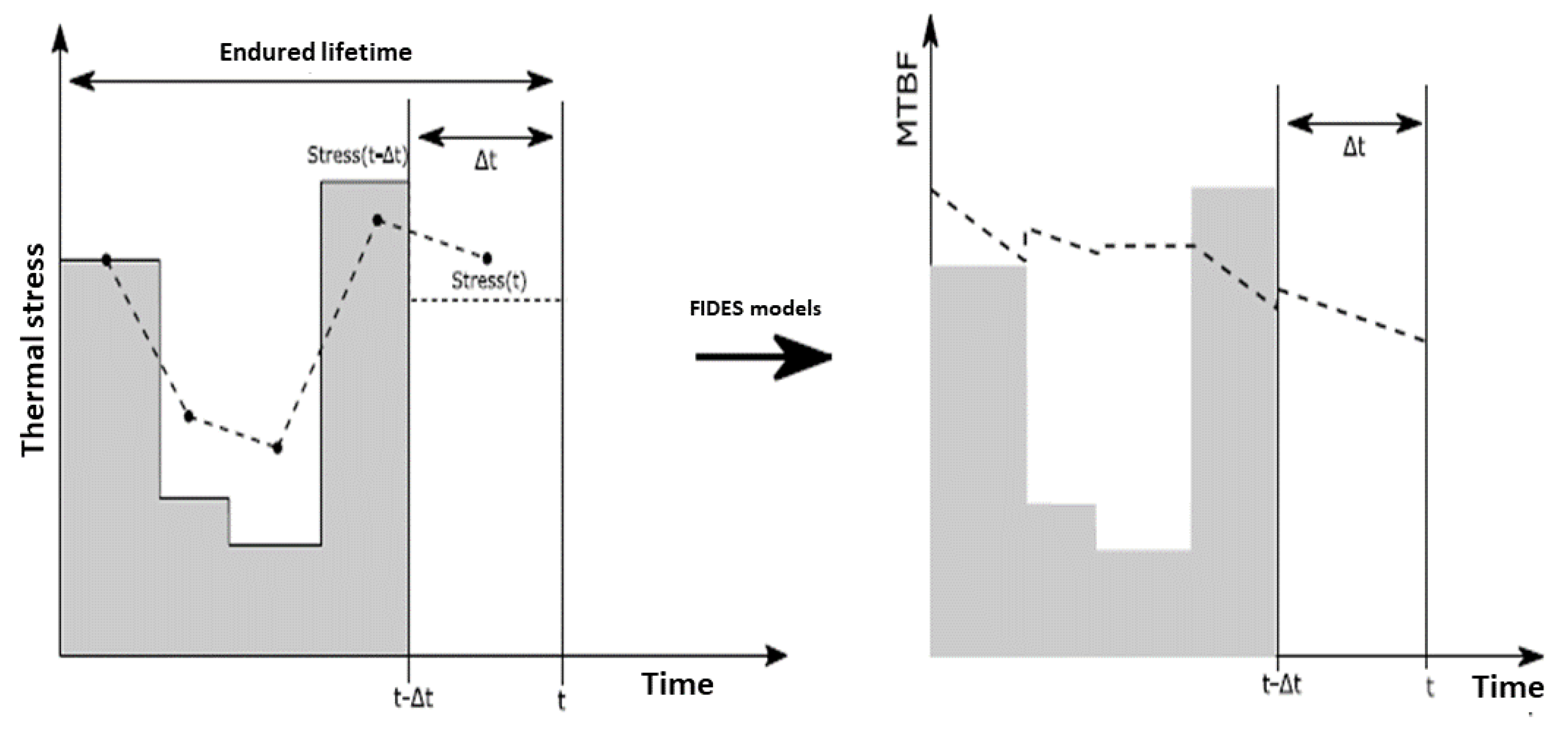

- Building statistical models: the collected thermal data will be used to construct statistical models, combining empirical results and FIDES reliability models.

- Integration into the converter microcontroller: the improved FIDES reliability models are integrated into the converter’s microcontroller to track the remaining lifespan of each component based on the operating conditions of the converter.

3.4. The Description of the Methodology

3.4.1. Collecting Data

3.4.2. Component’s Temperature Models Creation

3.4.1. Real-Time Predictive Algorithm

4. The Impact of Disassembly on the Remaining Lifetime

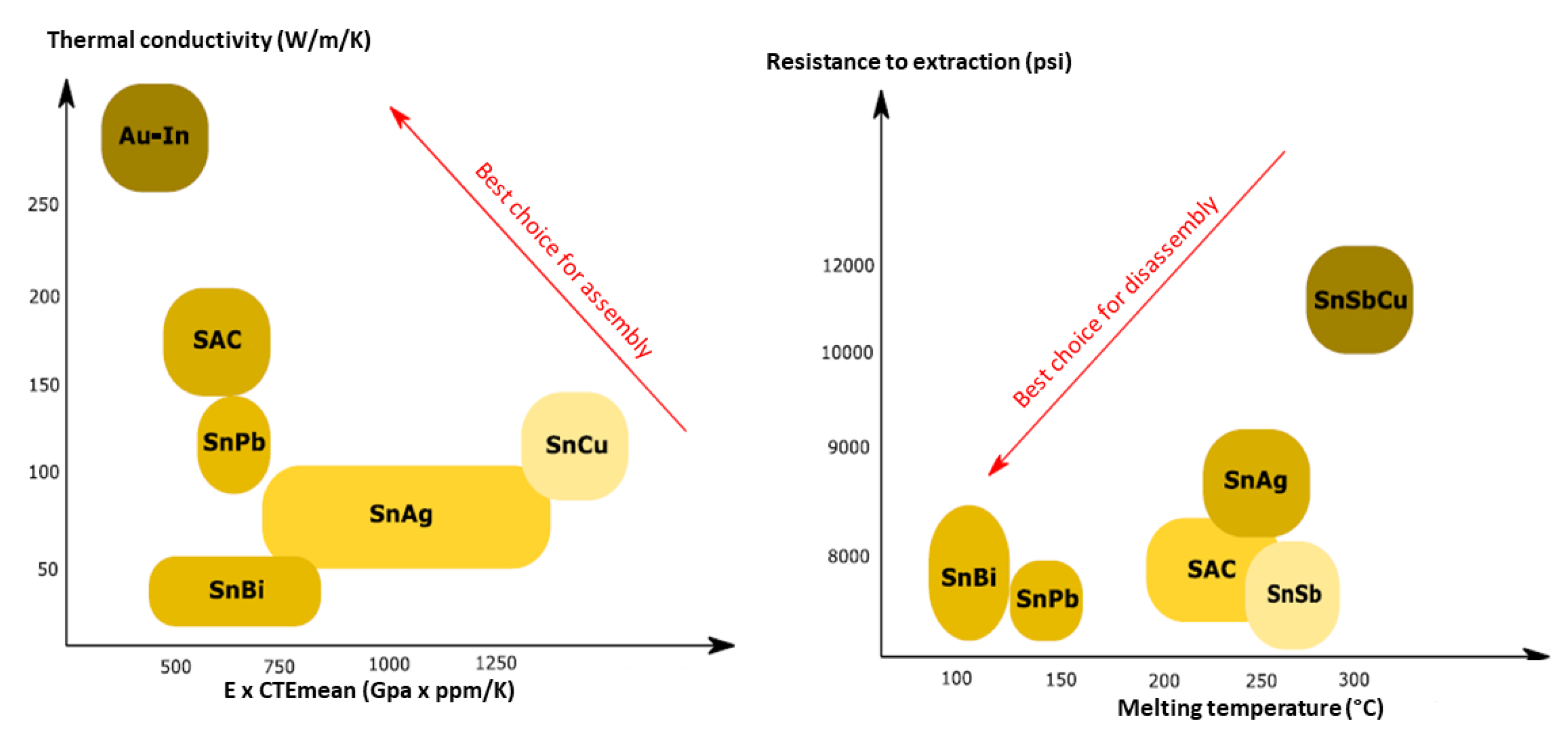

4.1. Disassembly Methods

| Methods | Tools | Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|---|---|

| Surface scraping | Pruning shears | Not polluting High volumes |

- The host PCB is destroyed - Requires cleaning - The component is still attached to a part of the PCB |

| Manually | Soldering iron + solder braid | Easy to implement | - Requires manual labor - Slow and inefficient for small components |

| Hot air | Hot air gun | Not polluting and fast | - Low precision control - Poor energy efficiency - Component temperature rise |

| Infrared ovens | Radiator + vibration | Not polluting and fast | Thermal damaging |

| Soldering ovens | Reflow oven + vibration | - Fast for assembly line processing - Efficient for large volumes of defective PCBs |

Non-targeted heat |

| Chemical | Epoxy treatment solutions or tin alloy dissolution solutions. | - Directly targets the solder - Low labor requirement |

- Polluting - Risk of damaging the component |

| Automatic | Robotic arm | Targeted heat | - Low throughput - Expensive |

- Preheating Phase: the PCB temperature gradually rises from ambient temperature to ~150°C, with a controlled ramp-up rate (0.75°C to 2°C per second). This step prevents thermal shock and eliminates residual chemicals.

- Soaking Phase: temperature stabilization ensures uniform heating across all components. During this phase, the flux in the solder paste activates, removing oxides from component leads and PCB pads to enhance electrical contact.

- Reflow Phase: solder particles melt and form metallurgical bonds between component pins and copper traces. The peak temperature must be high enough to liquefy the solder while avoiding component degradation.

- Cooling Phase: the PCB naturally cools using a fan, allowing the solder to solidify. This phase is critical for assembly but less relevant for disassembly, where precise cooling control is unnecessary.

| Type of Solder | Characteristics |

|---|---|

| Lead-based solder | Lead-containing solder alloys melt at relatively low temperatures (~180°C). However, due to environmental concerns, lead was banned after the 2011 European RoHS directive. These alloys typically contain 60% tin and 40% lead (e.g. Sn62Pb36Ag2 or Sn63Pb37). |

| Lead free solder | These alloys comply with the RoHS directive and are typically composed of 90% tin. They require higher melting temperatures (up to 270°C) and are more expensive. |

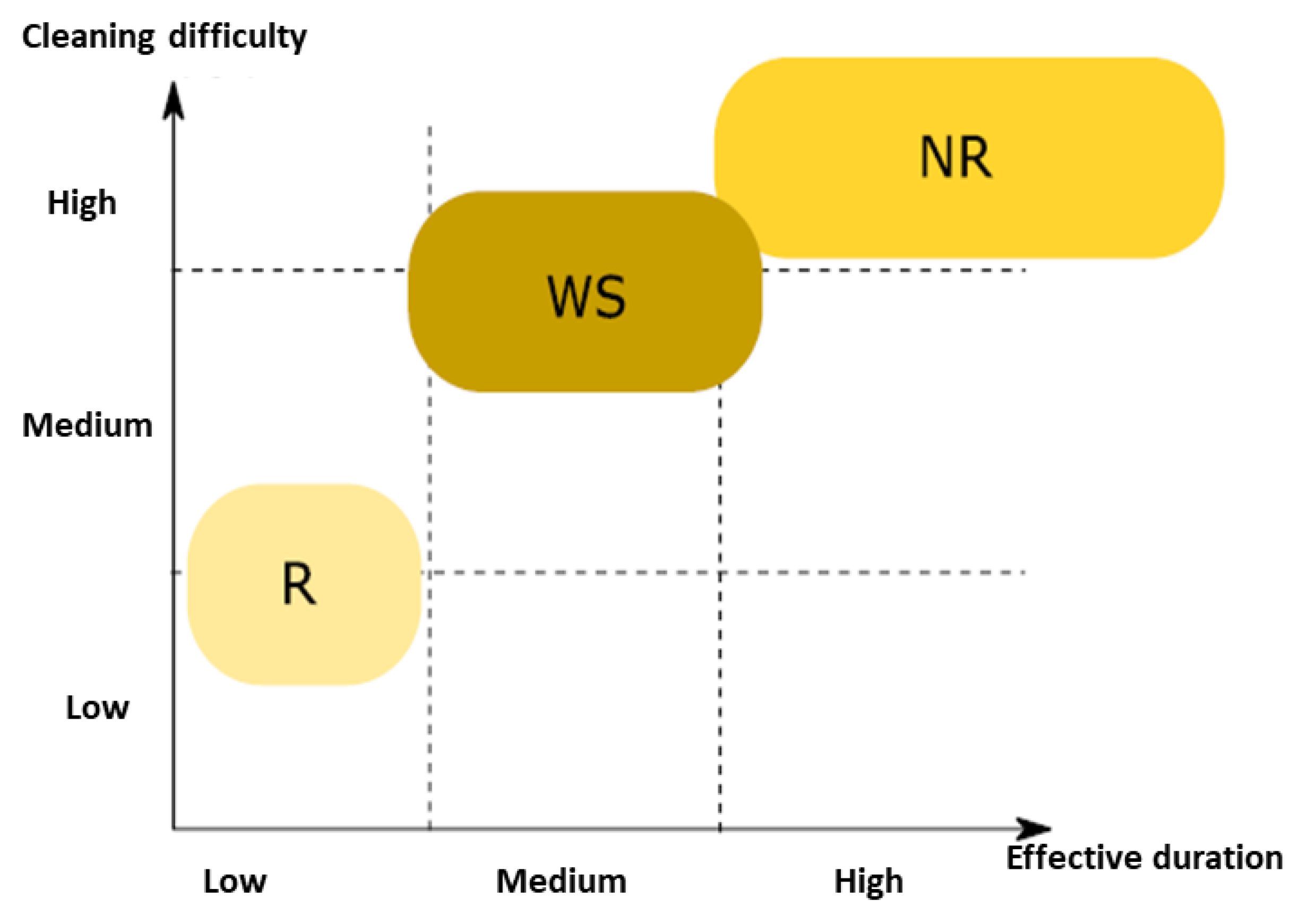

- Rosin-based (R): requires minimal cleaning, common in consumer electronics.

- Inorganic acid flux (NR): leaves minimal residue, used in industrial applications.

- Water-Soluble (WS): easily washable, environmentally preferred (less polluting) but requires additional cleaning steps.

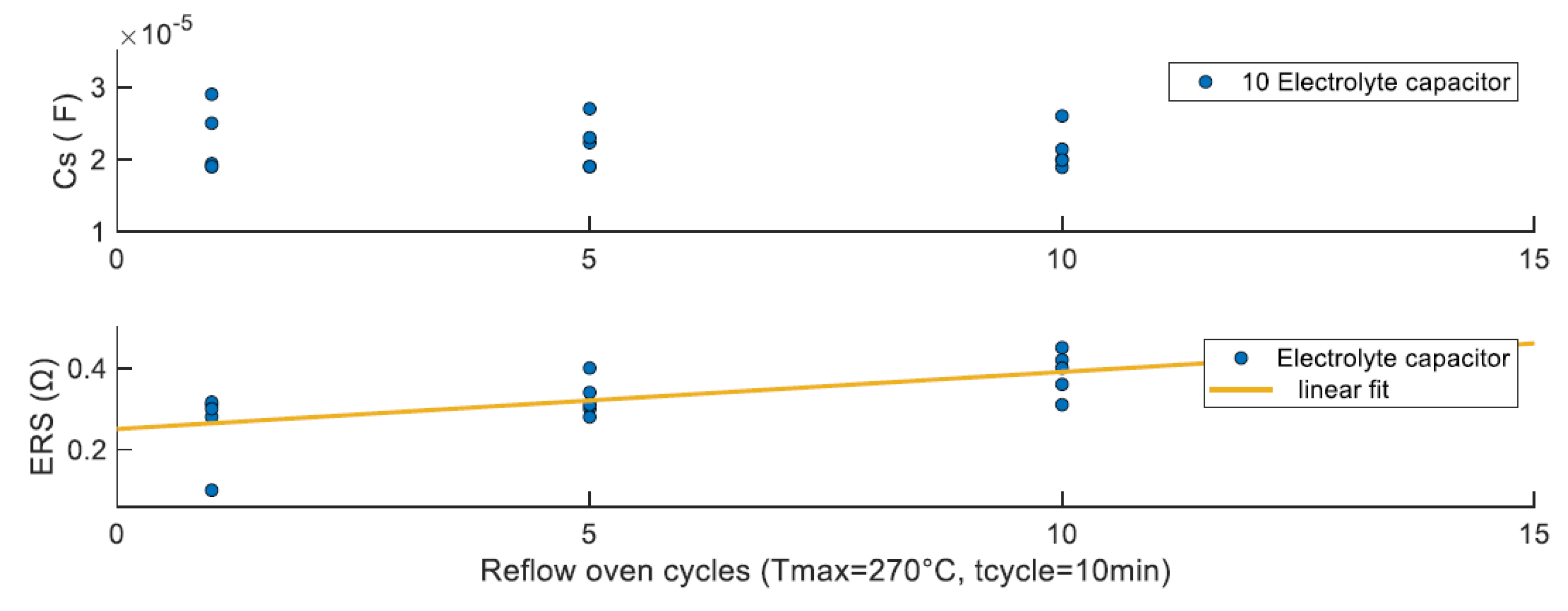

4.2. The Impact of Disassembly on SMD Electrolytic Capacitors

4.2.1. Aging Mechanisms of Capacitors

- A hermetically sealed aluminum casing to prevent electrolyte leakage.

- Stacked aluminum foils and insulating layers impregnated with electrolytes.

- A rubber sealing disc and a cover to maintain integrity.

- Two terminals: one connecting the anode foils and the other the cathode foils.

- Breakdown of the oxide dielectric layer.

- Electrolyte depletion and changes in its properties.

- Leakage of electrolytes through seals or self-regeneration of the oxide layer.

- Increase in ESR – indicating higher internal resistance.

- Decrease in Capacitance – resulting from dielectric deterioration.

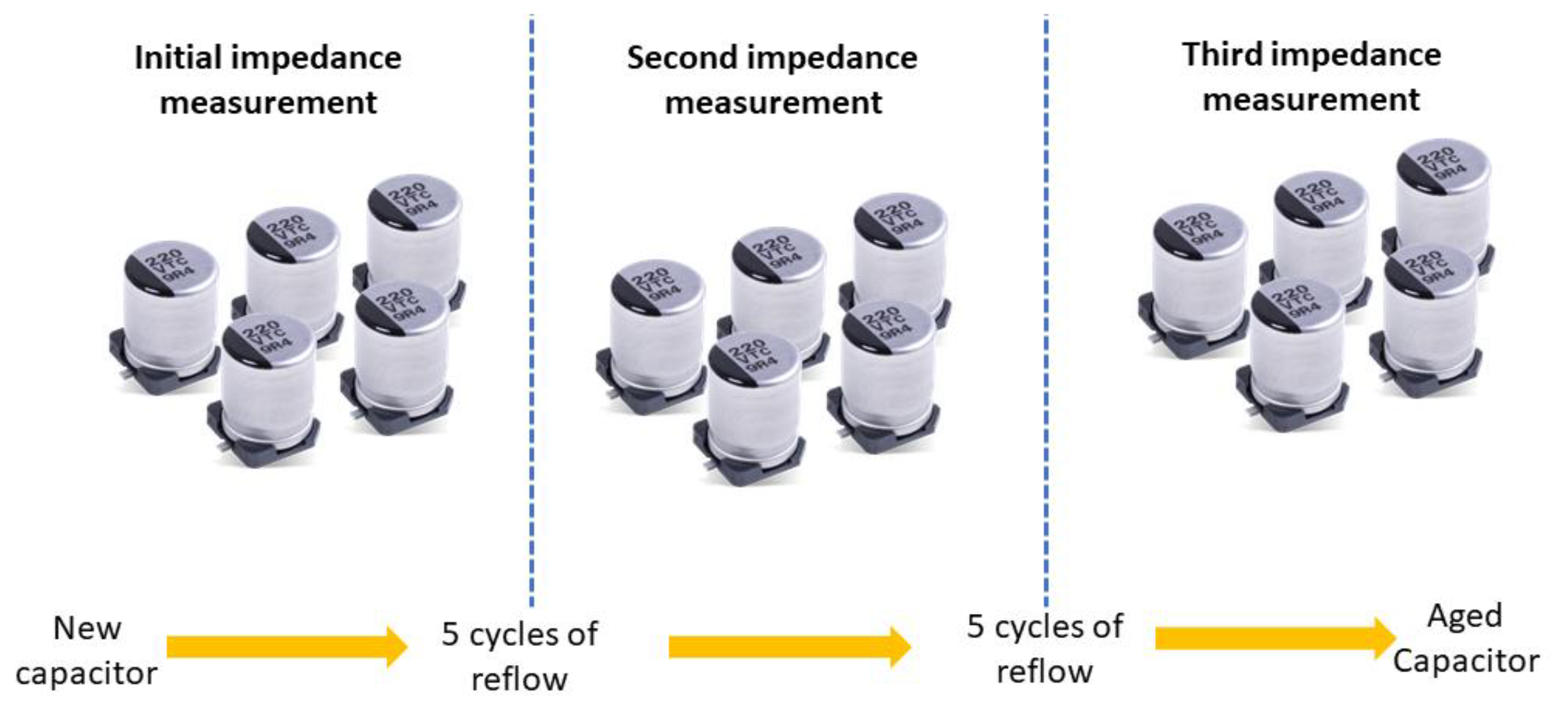

4.2.2. Aging Experimental Setup

| Parameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Capacity | 33 μF |

| Maximum temperature | 105°C |

| Nominal voltage | 7 V |

| ESR max (120Hz,20°C) | 300mOhm |

| Theoretical MTBF | 5 years |

4.3. The Impact of Disassembly on a SMD HF Planar Transformer

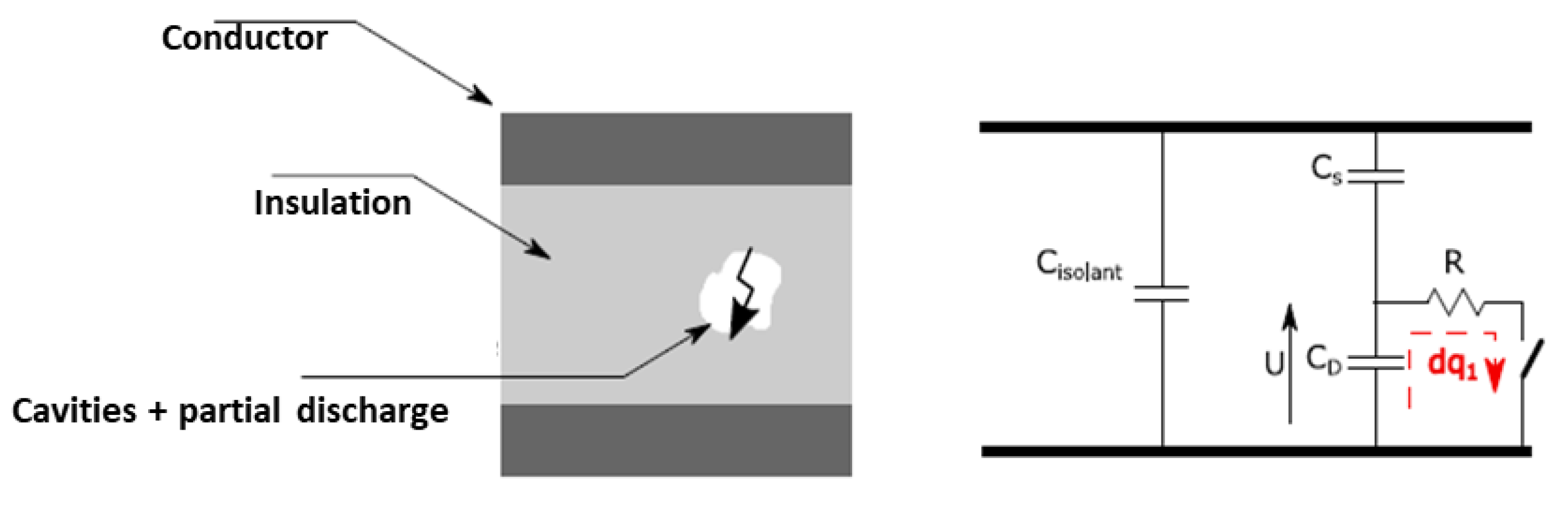

4.3.1. Aging Mechanisms and Experimental Results

- Insulation Breakdown: Insulation materials (e.g. epoxy resin, PVC, mica) degrade over time due to temperature stress, leading to cracks and reduced dielectric properties. Partial discharge tests, primary-secondary capacitance, and parallel resistance measurements can indicate insulation wear.

- Magnetic Core Aging: The ferrite core is thermally stable, but the adhesive bonding between core sections deteriorates over time, causing misalignment. This misalignment alters the magnetizing inductance, which serves as an indicator of core degradation.

- b>Winding and PCB Deterioration: Copper winding insulation weakens, and PCB deformations due to heat lead to microcracks. Oxidation of exposed copper and solder joint movement affect transformer structure and leakage inductance. Resonance frequency changes can indicate dielectric aging of windings.

4.3.2. Experimental Set Up

- Magnetizing inductance (measured with an impedance meter with an open-circuited secondary)

- Leakage inductance (measured with a short-circuited secondary)

- Primary-to-secondary capacitance (measured with both windings short-circuited)

- Partial discharge inception voltage, which indicates insulation degradation under high voltage

- Magnetizing inductance decreased by ~20% after 20 cycles.

- Leakage inductance and primary-secondary capacitance showed no significant trend due to initial component variability and measurement noise.

- A partial discharge inception voltage dropped by ~20%, indicating insulation degradation.

4.3.3. Link with the Remaining Lifetime

6. Conclusion and Discussion

- Reuse Rate: an empirical value based on repair experiments, indicating how many times a component can be successfully reused. This factor integrates functional complexity into the assessment.

- Environmental Impact & Reuse Costs: a theoretical indicator combining disassembly tools, time, energy consumption, and environmental footprint.

- Remaining Lifetime (RLT): a component retains its value if its remaining lifespan is significant.

- FIDES failure models, an empirical reliability calculation framework for electronic components and systems.

- Experimental methods using infrared (IR) thermal imaging to capture component degradation.

Key Research Contributions:

- Residual Value Function Modeling: a generic function for residual value estimation is introduced, incorporating parameters like Mean Time Between Failures (MTBF). Inspired by methodologies in the automotive sector, this quantification aids end-of-use decision-making during diagnostic phases.

- Reuse Rate Estimation for Passive Components: a method for estimating the reuse rate of passive components is proposed. Accelerated aging tests, particularly reflow oven cycling, provides degradation trends. Results suggest that robust components, like transformers, may outlast their datasheet specifications, whereas fragile components, such as electrolytic capacitors, degrade rapidly, making their reuse challenging.

-

Real-Time MTBF Estimation for Power Converters: a real-time MTBF estimation method is developed for standard power converters. This involves:

- Pre-use temperature data collection using thermal cameras and test benches.

- Statistical modeling based on collected data, integrated with FIDES reliability models and empirical results.

- Embedded implementation in the converter’s microcontroller for continuous health monitoring, allowing real-time tracking of each component’s remaining lifespan.

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- STEFFEN: Will, SANDERSON, Regina Angelina, TYSON, Peter D., et al. Global change and the earth system: a planet under pressure. Springer Science & Business Media. 2006.

- DIEDEREN, A. M. Metal minerals scarcity: A call for managed austerity and the elements of hope. TNO Defence, Security and Safety, 2009, p. 2.

- Critical Raw Materials Resilience: Charting a path towards greater security and sustainability document date : 02/09/2020 – Created by GROW.R.2.DIR – Publication date n/a Last update 03/09/2020.

- Rockström, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S., III; Lambin, E.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. Planetary boundaries: exploring the safe operating space for humanity. Ecol. Soc. 2009, 14, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VENN, Fiona. The oil crisis. Routledge. 2016.

- LENTON, Timothy M., ROCKSTRÖM, Johan, GAFFNEY, Owen, et al. Climate tipping points—too risky to bet against. 2019.

- SACHS, Jeffrey, KROLL, Christian, LAFORTUNE, Guillame, et al. Sustainable development report 2022. Cambridge University Press. 2022.

- S&P Global. (2022). The Future of Copper: Will the Looming Supply Gap Short-circuit the Energy Transition? IHS Markit. Retrieved from https://cdn.ihsmarkit.com/www/pdf/1022/The-Future-of-Copper_Full-Report_SPGlobal.pdf.

- Le marché de l’automobile d’occasion rembraye [archive] « Copie archivée » (version du 22 avril 2012 sur l’Internet Archive) - Emmanuel Egloff, Le Figaro, 21 avril 2011.

- Gupta, S.M.; Güngör, A.; Govindan, K.; Özceylan, E.; Kalaycı, C.B.; Piplani, R. Responsible & sustainable manufacturing. International Journal of Production Research 2020, 58, 7181–7182. [Google Scholar]

- Feltham, G.A.; Ohlson, J.A. Uncertainty Resolution and the Theory of Depreciation Measurement. J. Account. Res. 1996, 34, 209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, J.; Qiu, Q. Depreciation Rate by Industrial Sector and Profit after Tax in China. Chin. Econ. 2021, 55, 111–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiteux, M. L’amortissement dépréciation des automobiles. Revue de statistique appliquée 1956, 4, 57–73. [Google Scholar]

- Cote Argus RENAULT Kangoo, la valeur de référence - L’argus (largus.fr).

- Shafiulla, B. Marketing Strategies of Car Makers in the Pre-Owned Car Market in India. Indian Journal of Marketing 2012, 42, 8–16. [Google Scholar]

- Prado, S.M.; et al. The European used-car market at a glance: Hedonic resale price valuation in automotive leasing industry. Economics Bulletin 2009, 29, 2086–2099. [Google Scholar]

- SENTENAC-CHEMIN, Elodie et LANTZ, Frédéric. ANALYSE DES TENDANCES ETDES RUPTURES SURLE MARCHE AUTOMOBILE FRANCAIS.

- Second-life EV batteries: The newest value pool in energy storage by Hauke Engel, Patrick Hertzke, and Giulia Siccard.

- CORON, Eddy. Diagnostic d’état de santé des batteries au lithium utilisées dans les véhicules électriques et destinées à des applications en seconde vie. 2021. Thèse de doctorat. Université Grenoble Alpes [2020-....].

- Second Life-Batteries As Flexible Storage For Renewables Energies.

- https://op.europa.eu/en/publication-detail/-/publication/c6199b83-a368-4853-8bed-bc678404221e.

- Montoya-Bedoya, S.; Sabogal-Moncada, L.A.; Garcia-Tamayo, E.; Martínez-Tejada, H.V. A circular economy of electrochemical energy storage systems: Critical review of SOH/RUL estimation methods for second-life batteries. Green Energy and Environment 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serzhena, T. The circular economy on South Korea. The case of Samsung. Hungarian Agricultural Engineering 2019, 36, 75–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davis, N.T.; Hoomaan, E.; Agrawal, A.K.; Sanayei, M.; Jalinoos, F. Foundation reuse in accelerated bridge construction. Journal of Bridge Engineering 2019, 24, 05019010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkes, A.G. A Bivariate Exponential Distribution with Applications to Reliability. J. R. Stat. Soc. Ser. B Statistical Methodol. 1972, 34, 129–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mccool, J.I. Using the Weibull Distribution: Reliability, Modeling, and Inference; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Balasooriya, U.; Balakrishnan, N. Reliability sampling plans for lognormal distribution, based on progressively-censored samples. IEEE Trans. Reliab. 2000, 49, 199–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Guerrero, J.M.; Blaabjerg, F. A review of the state of the art of power electronics for wind turbines. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2009, 24, 1859–1875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, P.; Shirgaokar, A.; Arunachalam, D. Norris–Landzberg Acceleration Factors and Goldmann Constants for SAC305 Lead-Free Electronics. J. Electron. Packag. 2012, 134, 031008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peck, D.S. Comprehensive model for humidity testing correlation. In : 24th International Reliability Physics Symposium. IEEE, 1986. p. 44-50.

- D'Antuono, P. An analytical relation between the Weibull and Basquin laws for smooth and notched specimens and application to constant amplitude fatigue. Fatigue Fract. Eng. Mater. Struct. 2019, 43, 991–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- https://www.fides-reliability.org/Li, D.; Li, X. Study of degradation in switching mode power supply based on the theory of PoF. In Proceedings of the International Conference Computing Science and Service Systems, Nanjing, China, 11–13 August 2012; pp. 1976–1980.

- Jiang, N.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.Q.; Sun, L.; Long, W.M.; He, P.; Xiong, M.Y.; Zhao, M. Reliability issues of lead-free solder joints in electronic devices. Sci. Technol. Adv. Mater. 2019, 20, 876–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Susinni, G.; Rizzo, S.A.; Iannuzzo, F. Two Decades of Condition Monitoring Methods for Power Devices. Electronics 2021, 10, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AGARWAL, Mridul, PAUL, Bipul C., ZHANG, Ming, et al. Circuit failure prediction and its application to transistor aging. In : 25th IEEE VLSI Test Symposium (VTS’07). IEEE, 2007. p. 277-286.

- Parsley, M. The use of thermochromics liquid crystals in research applications, thermal mapping and non-destructive testing.

- Brekel, W.; Duetemeyer, T.; Puk, G.; Schilling, O. Time Resolved in situ Tvj Measurements of 6.5 kV IGBTs during Inverter Operation. In Proceedings of the PCIM Europe 2009: International Exhibition & Conference for Power Electronics Intelligent Motion Power Quality, Nurember, Germany, 12–14 May 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Motto, E.R.; Donlon, J.F. IGBT module with user accessible on-chip current and temperature sensors. In Proceedings of the Twenty-Seventh Annual IEEE Applied Power Electronics Conference and Exposition (APEC), Orlando, FL, USA, 5–9 February 2012; pp. 176–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ka, I.; Avenas, Y.; Dupont, L.; Vafaei, R.; Thollin, B.; Crebier, J.C.; Petit, M. Instrumented chip dedicated to semiconductor temperature measurements in power electronic converters. In Proceedings of the IEEE Energy Conversion Congress and Exposition (ECCE), Milwaukee, WI, USA, 18–22 September 2016; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Jasperneite, J.; Sauter, T.; Wollschlaeger, M. Why We Need Automation Models: Handling Complexity in Industry 4.0 and the Internet of Things. IEEE Ind. Electron. Mag. 2020, 14, 29–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheraghi, M.; Karimi, M.; Booin, M.B. An investigation on acoustic noise emitted by induction motors due to magnetic sources. In Proceedings of the 9th Annual Power Electronics, Drives Systems and Technologies Conference (PEDSTC), Tehran, Iran, 13–15 February 2018; pp. 104–109. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, H.; Wang, X.; Zhu, C.; Li, W.; He, X. Investigation and emulation of junction temperature for high-power IGBT modules considering grid codes. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2018, 6, 930–940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunger, T.; Schilling, O. Numerical investigation on thermal crosstalk of silicon dies in high voltage IGBT modules. In Proceedings of the PCIM International Exhibition & Conference for Power Electronics, Intelligent Motion, Power Quality, Nuremberg, Germany, 27–29 May 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Ceccarelli, L.; Luo, H.; Iannuzzo, F. Investigating SiC MOSFET body diode’s light emission as temperature-sensitive electrical parameter. Microelectron. Reliab. 2018, 88–90, 627–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, K.; Stalin, T.; Ramberg, H.; Wenske, J.; Wetter, G.; Karlsson, R.; Thiringer, T. Field-Experience Based Root-Cause Analysis of Power-Converter Failure in Wind Turbines. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2014, 30, 2481–2492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peyghami, S.; Palensky, P.; Blaabjerg, F. An Overview on the Reliability of Modern Power Electronic Based Power Systems. IEEE Open J. Power Electron. 2020, 1, 34–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kauzlarich, J.J. The Palmgren-Miner Rule Derived; Tribology Series; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1989; pp. 175–179. [Google Scholar]

- Rahmani, B.; Rio, M.; Lembeye, Y.; Crebier, J.-C. Design for reuse: Residual value monitoring of power electronics’ components. Procedia CIRP 2022, 109, 140–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahmani, B.; Lembeye, Y.; Crebier, J.-C.; Rio, M. Analysis of passive power components reuse. In PCIM Europe Digital Days 2021: International Exhibition and Conference for Power Electronics, Intelligent Motion, Renewable Energy and Energy Management. VDE Verlag. 2021; pp. 1–8.

| Type of Condition Monitoring Methods | The Method | Measured Quantity |

|---|---|---|

| Electrical methods: in contact with the Component | Saturation current | Vce-Vds |

| Threshold gate voltage | Vge-Vgs | |

| On voltage | Vce-Vd | |

| Di/dt variation | The device’s current | |

| Thermal methods (with a sensor) | Thermal analysis chip (TTC) | Thermal resistance |

| Acoustic methods (no contact) | Acoustic waves | Wavelength or harmonic distortions |

| Optical methods (no contact) | photodiodes sensors | Light intensity |

| Infrared camera | wavelength |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).