1. Introduction

As electronic packaging continues to advance toward higher performance and greater integration density, the ongoing miniaturization of chip dimensions and the widespread adoption of advanced packaging technologies have enabled the vertical stacking of multiple dies. This paradigm shift effectively reduces signal propagation delays and significantly enhances system-level integration and overall performance. However, the increasing number of stacked chips, coupled with reduced feature sizes and elevated packaging densities, introduces a host of new reliability challenges. These include thermal management issues, electromigration, thermomigration, time-dependent dielectric breakdown (TDDB), and various interacting degradation mechanisms [

1,

2,

3,

4]. Among these, TDDB has emerged as a particularly critical reliability concern. This is primarily due to the narrowing spacing between metal interconnects, increased electric field strengths, and elevated operating temperatures-factors that synergistically accelerate the onset and progression of TDDB failure mechanisms [

5,

6,

7,

8]. TDDB not only undermines device longevity and operational stability but can also precipitate catastrophic system-level failures. Consequently, the accurate characterization, modeling, and analysis of TDDB-induced degradation in both devices and interconnect structures—as well as the underlying failure mechanisms—have become essential and increasingly complex focal points in the field of integrated microsystem reliability.

TDDB refers to a progressive degradation mechanism wherein prolonged electrical stress induces the gradual migration of atoms within the dielectric layer, ultimately leading to the formation of conductive paths. This process results in a gradual increase in leakage current, culminating in catastrophic dielectric failure via electrical breakdown. In the initial stages of TDDB, the variation in leakage current remains relatively modest. However, as the duration and intensity of electrical stress increase, the leakage current begins to rise at an accelerating rate, eventually exhibiting a sharp exponential surge that signifies imminent dielectric failure. Under higher electric fields, dielectric materials exhibit significantly reduced electrical stability, which promotes the rapid nucleation and growth of conductive filaments (CFs). Consequently, both the magnitude and the rate of change of leakage current increase substantially [

8,

9]. This behavior imposes stringent reliability requirements on the selection and design of dielectric materials used in semiconductor integrated circuits (ICs) [

10]. Therefore, it is crucial to conduct in-depth investigations into the behavioral characteristics of TDDB under diverse operational conditions.

Traditionally, TDDB characterization has primarily focused on gate oxides in transistors. In response to the complex nature of TDDB under various stress conditions, numerous empirical and physics-based lifetime models have been proposed. These include the E model, 1/E model, E

1/2 model, power-law model, and fatigue damage model [

12,

13,

14,

15]. A. Vici introduced a multi-level-independent defect generation framework to describe the evolution of defects in gate oxides under TDDB stress. This approach assumes that defect generation within the dielectric is proportional to both the energy and the quantity of injected charge carriers [

15]. Building upon this foundation, Vici further developed an analytical Markov-based model capable of predicting TDDB failure times in metal–oxide–semiconductor (MOS) systems under arbitrary voltage and temperature stress conditions [

16], thereby enabling accurate reliability estimation across a wide range of operational scenarios. In contrast, S. Peng proposed an electron pathway generation model tailored for intra-layer dielectrics in copper interconnects, where defect formation arises from the diffusion of metal ions within the dielectric matrix [

17]. However, as device dimensions continue to scale down, process variations increasingly influence structural integrity and reliability. For instance, in [

18], a novel comprehensive modeling approach was proposed to assess the impact of line-edge roughness (LER) on TDDB behavior. Their findings revealed that LER not only significantly reduces the scale parameter of the Weibull distribution but also decreases the shape parameter, indicating a broader variability in time-to-failure distributions. Additionally, studies in [

19,

20] presented a time-to-failure model incorporating LER effects for predicting TDDB reliability in scaled copper interconnects. The validity and accuracy of the model were rigorously evaluated, demonstrating its applicability across conventional and spacer-defined nanoscale patterning techniques. These results underscore the criticality of accounting for LER-induced variability in reliability assessments. Despite these advancements in modeling dielectric degradation within devices and packaging structures, there remains a notable gap in the development of circuit-level TDDB degradation models that incorporate LER effects in advanced interconnect architectures. Hence, it is essential to establish a SPICE-compatible lifetime prediction model that integrates LER-induced variability, enabling a more holistic and realistic reliability evaluation of modern electronic systems.

In this study, a physics-based SPICE-compatible degradation model is developed for inter-metal dielectric layers, specifically designed to incorporate the effects of breakdown (BD)-induced failures and LER-induced resistance degradation on circuit-level performance simulations in advanced packaging interconnect structures. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows.

Section 2 provides an overview of the relevant research background and simulation methodologies associated with the electron pathway generation (EPG) model.

Section 3 presents a comprehensive description of the proposed modeling framework, including the development of the SPICE degradation model, the LER-based process variation model, and their integration into the overall simulation environment.

Section 4 offers an in-depth analysis and discussion of the simulation results, highlighting the impact of TDDB and LER on circuit performance degradation. Finally,

Section 5 concludes the paper with a summary of key findings and potential directions for future work.

2. Review of EPG Model For TDDB

This section begins with an overview of the EPG model for time-dependent dielectric breakdown (TDDB), as proposed in [

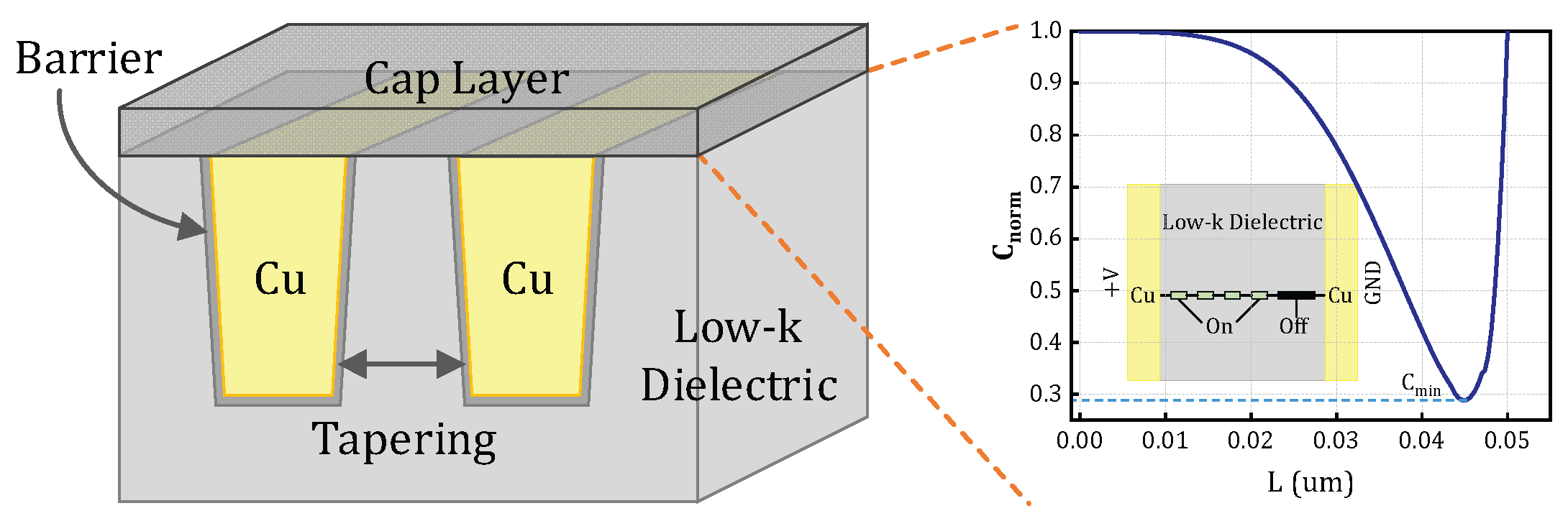

17]. As illustrated in

Figure 1, this model focuses on the metal–insulator–metal (MIM) structure and analytically examines the time evolution of metal ion concentration within the dielectric layer. By introducing a concentration threshold criterion, the model enables the prediction of the dielectric time-to-failure (TTF). Based on the insights obtained from the EPG model, barrier metal ions are injected into the dielectric layer under electrical stress. In this study, particular attention is given to the two-dimensional diffusion behavior of these ions at the interface between the inter-metal dielectric (IMD) and the oppositely charged metal electrodes. Simulation results indicate that TDDB-induced failure predominantly initiates within this interfacial region.

In the proposed framework, the local electrical conductivity is assumed to be proportional to the hopping probability of electrons between adjacent defect centers. As metal ion diffusion progresses, defects are generated within the dielectric matrix, acting as potential sites for electron localization originating from the metal electrodes. These interconnected defect centers collectively form a distributed resistive network. The resistance between any two defect centers i and j is determined according to Equations (1) and (2), which govern the electron transport characteristics within the evolving conductive pathways.

where

is the distance between

and

centers, a is the radius of electron localization at this type of centers (analog of Bohr’s radius), which can reach 100Å,

is the energy barrier between centers,

is the Boltzmann constant, T is the absolute temperature,

is the thermal energy, and

is the ion concentration at the considered interface as a function of spatial coordinates and time.

Figure 1 illustrates the corresponding resistive network within the IMD at an arbitrary time, along with the ion concentration distribution along the conduction path from point (0, d) connecting the metal electrodes. According to Equation (1) and (2), a higher ion concentration corresponds to a lower resistance. When the total resistance along the (0, d) path decreases to a predefined threshold, the formation of an electrical conduction path is considered to occur, indicating the onset of TDDB failure. Due to the exponential dependence of resistance on the distance between adjacent conductive centers, the total resistance along the (0, d) path is predominantly determined by the largest individual resistance—that is, the location with the lowest ion concentration in the dielectric layer. Consequently, the threshold resistance of the conduction path can be reasonably approximated as being governed by the minimum ion concentration. The normalized ion concentration distribution, defined as

, is governed by the ion transport equation under an applied electric field, as described by Equation (3) and (4).

The boundary conditions are given by

where

is the metal ion flux,

is the diffusion coefficient,

is the drift velocity of metal ions,

is the activation energy , q is the elementary charge, E is the electric field, The distance d is considered to be the minimum spacing between two metal lines within the IMD.

In the one-dimensional case, the governing drift-diffusion equation, along with the corresponding boundary and initial conditions, can be expressed as in Equations (5), (6), and (7).

The boundary conditions are given by

The initial condition is defined as

3. TDDB SPICE Modeling Method

In this section, a macroscopic characterization of the TDDB mechanism in the dielectric layer is presented, based on the physical evolution of CF formation. Accordingly, a SPICE-compatible degradation model is proposed to enable circuit-level simulation and reliability assessment of TDDB effects under various operational conditions. Further, a LER-based process variation model is introduced to account for manufacturing-induced dimensional and structural fluctuations in interconnect geometries. Finally, an integrated modeling and simulation framework is established, incorporating LER-aware effects into the TDDB degradation model. This framework enables comprehensive characterization of dielectric failure mechanisms at both device and circuit levels, facilitating more accurate reliability predictions for advanced electronic packaging technologies.

3.1. CF Compact Model

In inter-metal dielectric layer, atoms gradually accumulate along preferential diffusion paths due to electrostatic forces, eventually forming a narrow conductive filament (CF) that bridges the two electrodes. Once the CF is fully formed, the dielectric undergoes a significant increase in electrical conductivity, leading to a sharp decline in its insulating capability. This transition initiates a cascade of electrochemical and thermochemical reactions within the dielectric layer. For instance, under certain conditions, the CF may induce device thermal expansion or fracture, increased signal transmission loss, and delay, all of which adversely affect the stability and reliability of the dielectric interface.

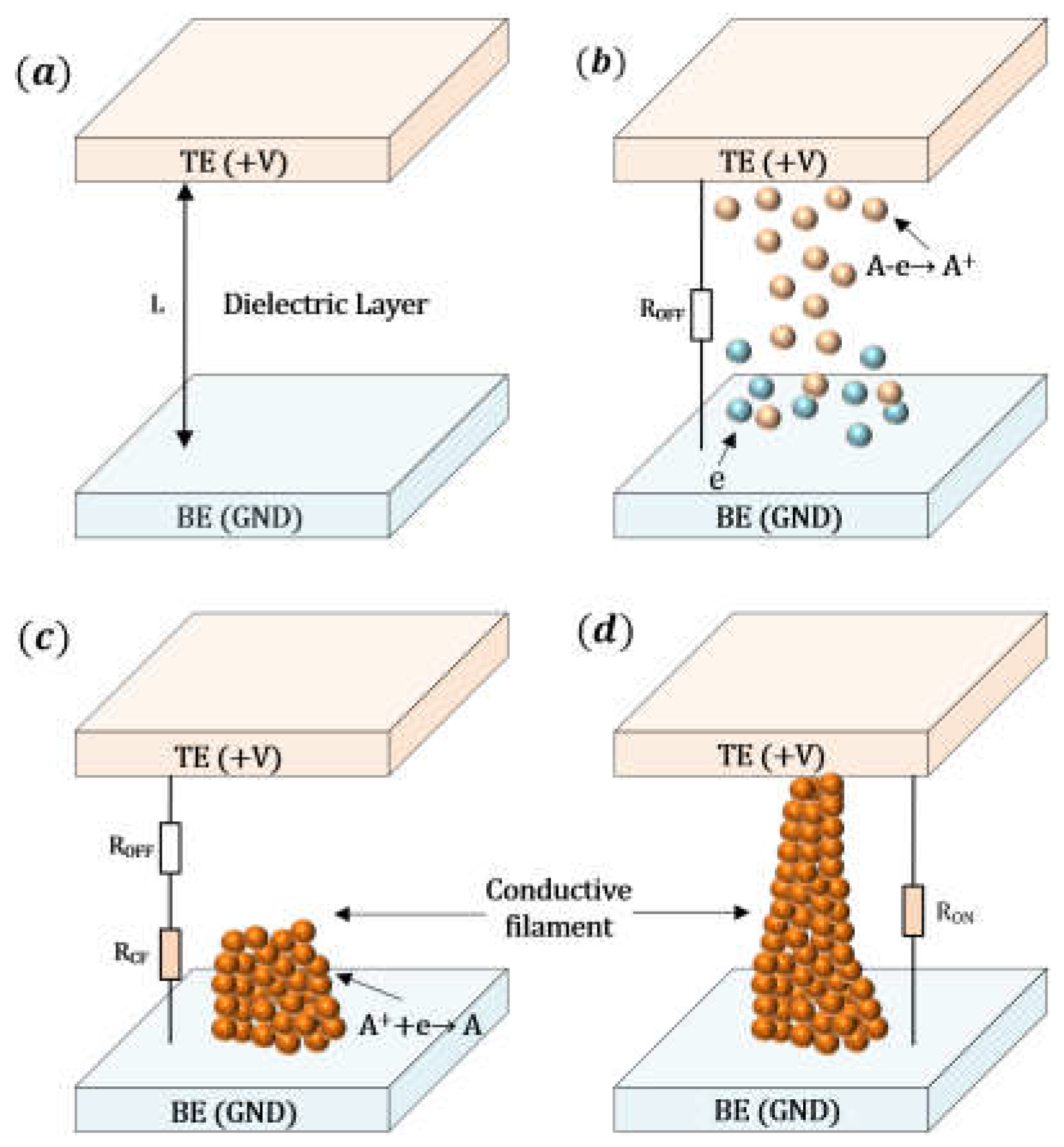

The formation process of the CF is illustrated in

Figure 2 [

21].

Figure 2 (a) illustrates the initial off-state, where no defects are generated within the dielectric layer and atoms do not undergo migration. Upon applying a forward bias to the active electrode, electrochemical reactions occur at the interface between the active electrode and the dielectric, resulting in atom A losing an electron

, as shown in

Figure 2 (b). Subsequently, the

migrate under the influence of the electric field toward the inert electrode, where they capture an electron near the inert electrode, forming

. These A atoms gradually accumulate within the dielectric layer, initially forming a narrow CF in the longitudinal direction, followed by lateral growth as depicted in

Figure 2 (c). Eventually, a tapered CF connecting the top and bottom electrodes is formed, as shown in

Figure 2 (d).

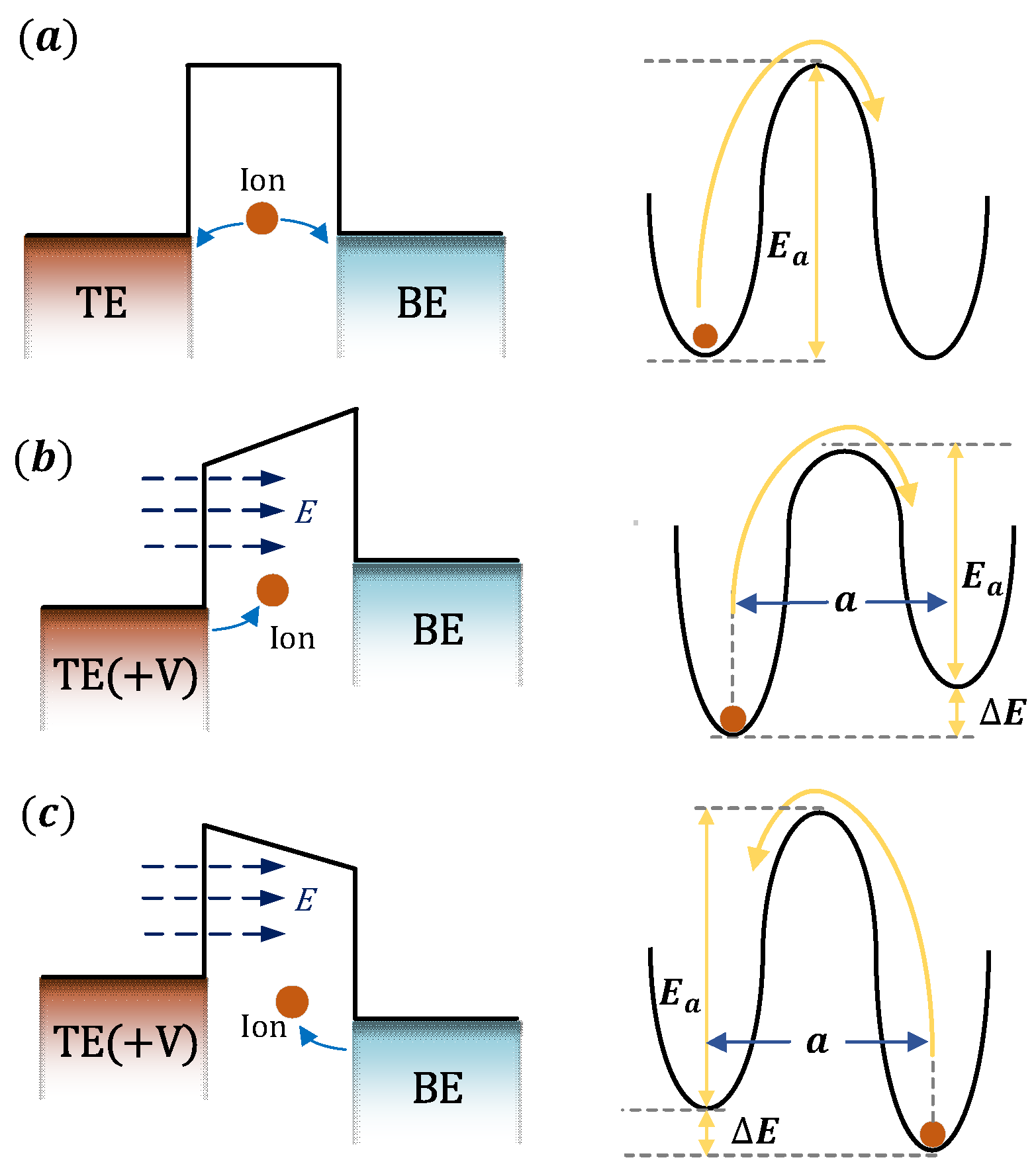

At the macroscopic level, the formation of the CF can be described as the drift of ions and accumulation of atoms [

22]. As shown in

Figure 3 (a), in the absence of an external electric field, the initial migration energy barrier for ions is

. Under this condition, ion migration is random, with equal probabilities of moving left or right, both given by

. Once an external voltage is applied to the active electrode (top electrode, TE), the migration energy barrier changes: the barrier height for ion migration toward the inert electrode (bottom electrode, BE) decreases to

, as shown in

Figure 3 (b), while the barrier height for migration toward the TE increases to

, as shown in

Figure 3 (c). Under the presence of an external electric field E, work is performed on charged ions, altering their potential energy. The change in potential energy for ions moving along the direction of the electric field is

, while for those moving in the opposite direction, it is

. Consequently, under the influence of the external electric field, the migration energy barriers for ions moving to the left and right become

and

. Under these conditions, the ion migration rates to the left and right can be expressed as

where,

is the attempt frequency,

is the field acceleration factor,

is the ion charge number. The drift velocity of the ions

is then calculated as

where,

is the applied voltage,

.

Based on the ion drift velocity, the ion drift flux

can be calculated as

The formation of the CF within the dielectric is primarily attributed to ion drift and atomic accumulation. Given a time interval dt the change in CF length is denoted as

During this interval, the number of ions drifting through a cross-sectional area S and contributing to CF growth can be calculated based on the increase in the number of atoms within a volume

. Accordingly, the longitudinal growth of the CF can be described by

where, t is the time,

is the longitudinal displacement of ions, n is the atomic density, h and

corresponds to the length and diameter of the CF, respectively.

Within a given time interval

, the change in the base diameter of the CF is denoted as

, resulting in a corresponding volume change of

, Accordingly, the lateral growth of the CF diameter can be expressed as

As atoms continuously accumulate within the dielectric layer, its electrical properties progressively degrade, ultimately compromising device reliability. Upon the CF bridging the top and bottom electrodes, the dielectric transitions into a low-resistance state. This facilitates a substantial current flow through the dielectric, potentially inducing electrical breakdown and further exacerbating reliability concerns. By jointly solving Equations (10)-(13), the temporal evolution of the CF’s vertical length

and lateral diameter

can be quantitatively described as

3.2. TDDB SPICE Model

According to the compact model described in Section A, the resistivity of the dielectric layer gradually decreases with the accumulation of atoms. The failure time of the dielectric layer is defined as the moment when the CF penetrates through it. Initially, there is no atomic accumulation within the dielectric layer, and its initial resistance can be calculated as

where,

is the resistivity of the dielectric layer,

is the thickness of the dielectric, and

is the bottom area of the CF. In this initial state, the dielectric layer exhibits excellent insulating properties, low dielectric loss, and favorable transmission characteristics. Under the influence of physical fields such as temperature and electric field, defects gradually emerge within the dielectric layer, leading to atomic migration. As atoms continue to accumulate, the size of the CF increases progressively, while the resistance, insulation, and other characteristics of the dielectric layer begin to deteriorate. During this process, the resistance of the dielectric layer becomes determined by the size of the CF, and can be expressed as

where,

is the resistivity of the dielectric layer after the formation of the CF, and

is the length of the CF.

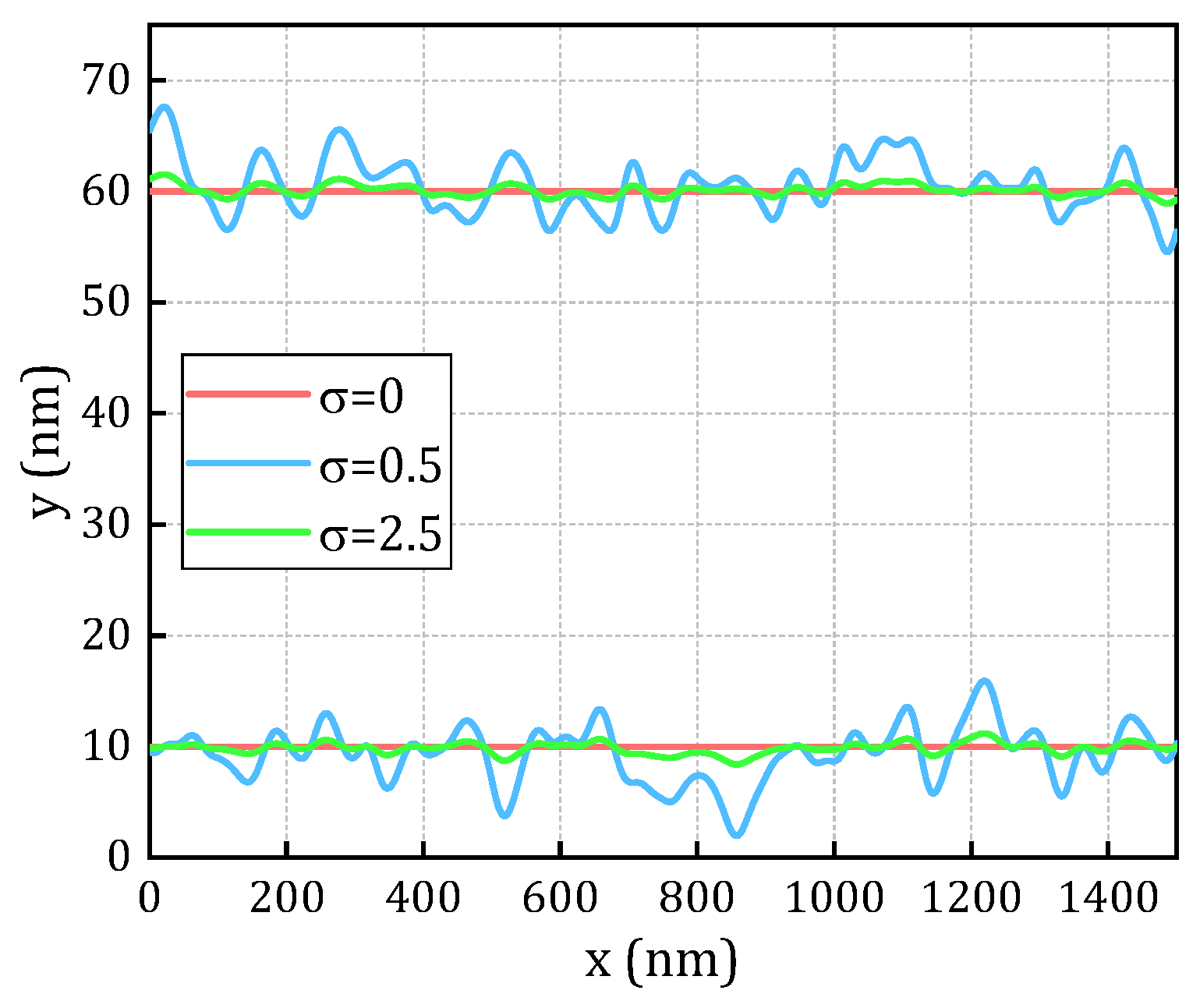

3.3. Process Variation Model

LER and line-to-line spacing (L2L) variations are critical factors affecting the performance of nanoscale devices and interconnects, particularly leading to significant degradation in TDDB performance and reliability. To effectively quantify and evaluate the impact of LER on TDDB effect, a Fourier synthesis technique is developed based on the PSD derived from a Gaussian autocorrelation function (ACF), as reported in [

23], to simulate and generate LER profiles. In this approach, the material structure is subdivided into N discrete microcells, and a random phase is assigned to each cell to ensure the stochastic nature and realistic matching of the simulation. The amplitude of the LER generated by the random phase is constrained by the PSD of the Gaussian ACF, thereby ensuring compliance with the statistically observed distribution characteristics from experiments. Specifically, this method characterizes the LER features by

where

is the PSD of the Gaussian ACF,

and

represent the correlation length and root mean square (RMS) amplitude of the LER profile, respectively. The wave vector

is defined as

.

is the spacing between two adjacent segments, which should be much smaller than

to ensure adequate discretization resolution. In this study,

=0.5, which is significantly smaller than

, typically ranging from 20 to 50 nm [

24], with

=30nm.

Figure 4 illustrates the Gaussian ACF and randomly generated LER profiles for a dielectric layer length of 50 nm and RMS amplitudes

of 0, 0.5, and 2.5nm, respectively.

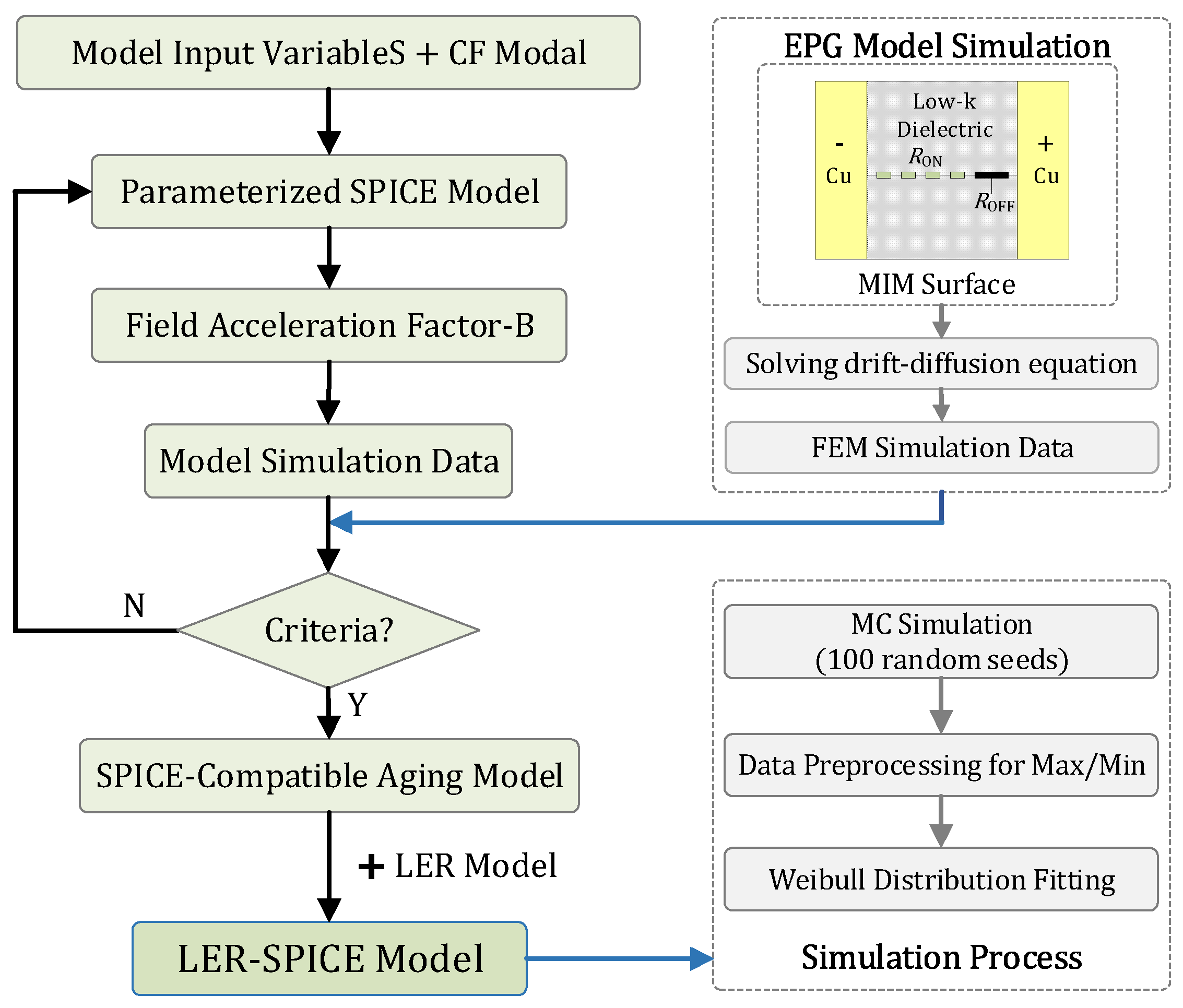

3.4. TDDB SPICE Modeling Framework

The overall framework of the proposed TDDB SPICE modeling approach is illustrated in

Figure 5. The CF model is first combined with the required input parameters to establish a compact representation of the CF evolution process, based on Equations (14)-(17). The EPG model is then employed to simulate the TDDB failure mechanism in the dielectric layer in the BEOL metal interconnect structure, to capture the evolution of metal ion concentration within the dielectric and thereby evaluate and calibrate the proposed degradation model. Following the methodology described in this section, a parameterized SPICE model is developed to describe the TDDB behavior of the MIM structure. Using simulation data obtained from the EPG model, the field acceleration factor B is extracted by fitting, and a SPICE-based degradation model is constructed to characterize the temporal evolution of current and resistance, as well as to enable lifetime prediction. To validate the model’s applicability under varying operational and process conditions, comparisons were conducted by adjusting key model parameters (such as activation energy

and dielectric layer thickness L), voltage excitation conditions (rectangular and sinusoidal waveforms), and simulations based on the EPG model. Moreover, to assess the impact of process variations on device reliability, a process tolerance model was integrated into the SPICE degradation model, followed by simulation analyses under different stress amplitudes. During this procedure, to ensure the reliability of the experimental data, Monte Carlo simulations were performed using 100 random seeds generated according to the power spectral density function, yielding 100 sets of experimental data. Subsequently, data processing involved excluding outliers by removing the top and bottom 10 datasets. Finally, the Weibull distribution model was applied for fitting and analysis to characterize the failure behavior. Under different stress conditions, the characteristic failure time (t

BD,63%) was extracted from the fitting results and employed as a critical reference metric for device reliability evaluation.

4. Results and Discussions

This section begins with an analysis of the TTF simulation results obtained from the EPG model. Based on these results, a field-acceleration-factor-based SPICE-compatible degradation model is developed, providing a quantitative framework for predicting device degradation under various stress conditions. Building upon this foundation, a process tolerance model is incorporated into the SPICE degradation framework to account for manufacturing-induced variability. A total of 100 independent datasets are generated through Monte Carlo simulations, each representing a statistically significant variation in process parameters derived from the PSD function. The failure behavior of these datasets is characterized using the Weibull distribution model, ultimately yielding the characteristic failure time tBD,63%.

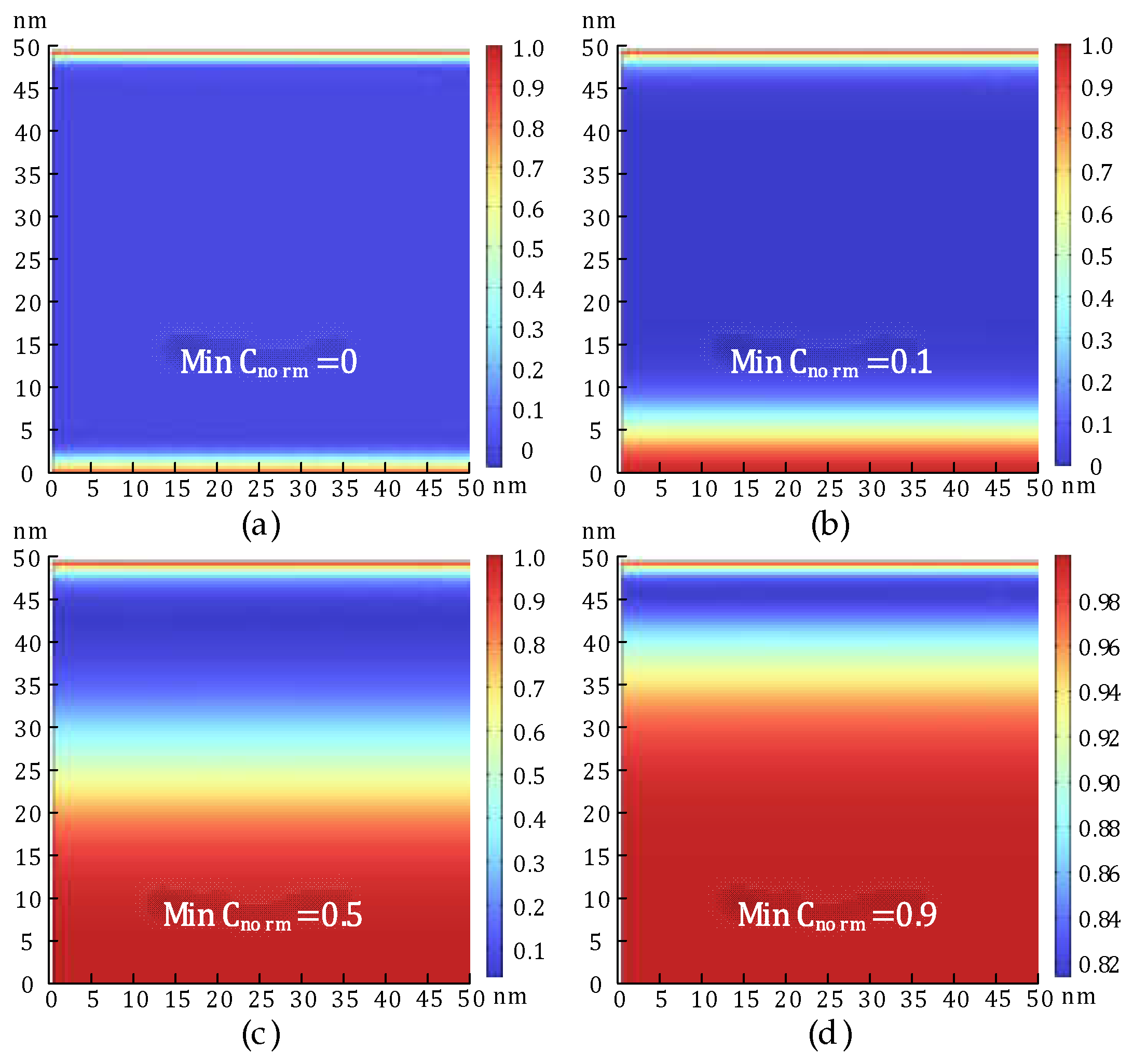

4.1. Simulation Results of the EPG Model

Based on the EPG model outlined in Section II, a normalized minimum ion concentration threshold of

is defined along the path (0, d) to serve as the failure criterion for dielectric breakdown. As illustrated in

Figure 1, one terminal of the structure is connected to the supply voltage

, while the other is grounded (GND), with the dielectric material occupying the intervening region. Finite element simulations are performed using the structural configuration shown in

Figure 1 and the parameter set detailed in

Table 1, aimed at solving the drift-diffusion equation governing ion transport under electrical and thermal stress conditions. The temporal evolution of

within the MIM structure is depicted in

Figure 6, demonstrating the progressive accumulation of mobile ions leading to conductive filament formation.

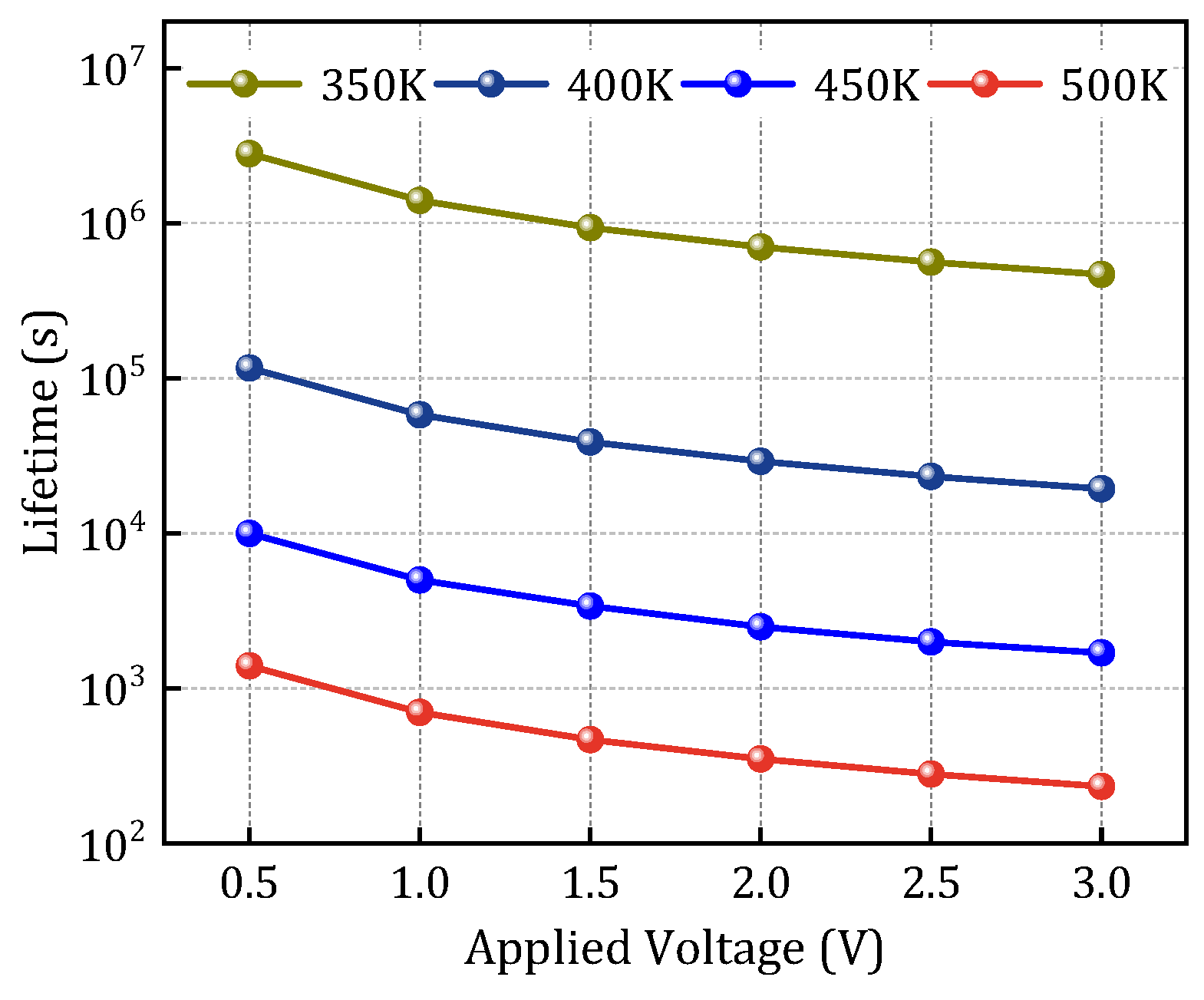

Figure 7 summarizes the extracted TTF results under varying temperature and voltage bias conditions, highlighting the dependence of TDDB degradation on operational stress factors.

4.2. Validation of the SPICE Degradation Model

Using the structure depicted in

Figure 1 and the parameter values summarized in

Table 2, a SPICE-compatible degradation model is established based on the theoretical foundation of EPG model. TTF data obtained from finite element simulations under conditions of V=1 V and T=370 K is utilized as training samples for model calibration. Through curve fitting of the simulation data, the field acceleration factor is extracted as B=3.15. To validate the model’s predictive capability across different operating conditions, the resistance degradation behavior predicted by the SPICE model is compared with FEM simulation results under varying voltage and temperature levels. The validation is performed over a temperature range of 350 K to 450 K and a voltage range of 0.5 V to 3 V. The relative errors between the SPICE model predictions and numerical results are summarized in

Table 3, demonstrating excellent agreement with all relative errors remaining below 2.5%, thereby confirming the model's accuracy and robustness across a wide range of stress conditions.

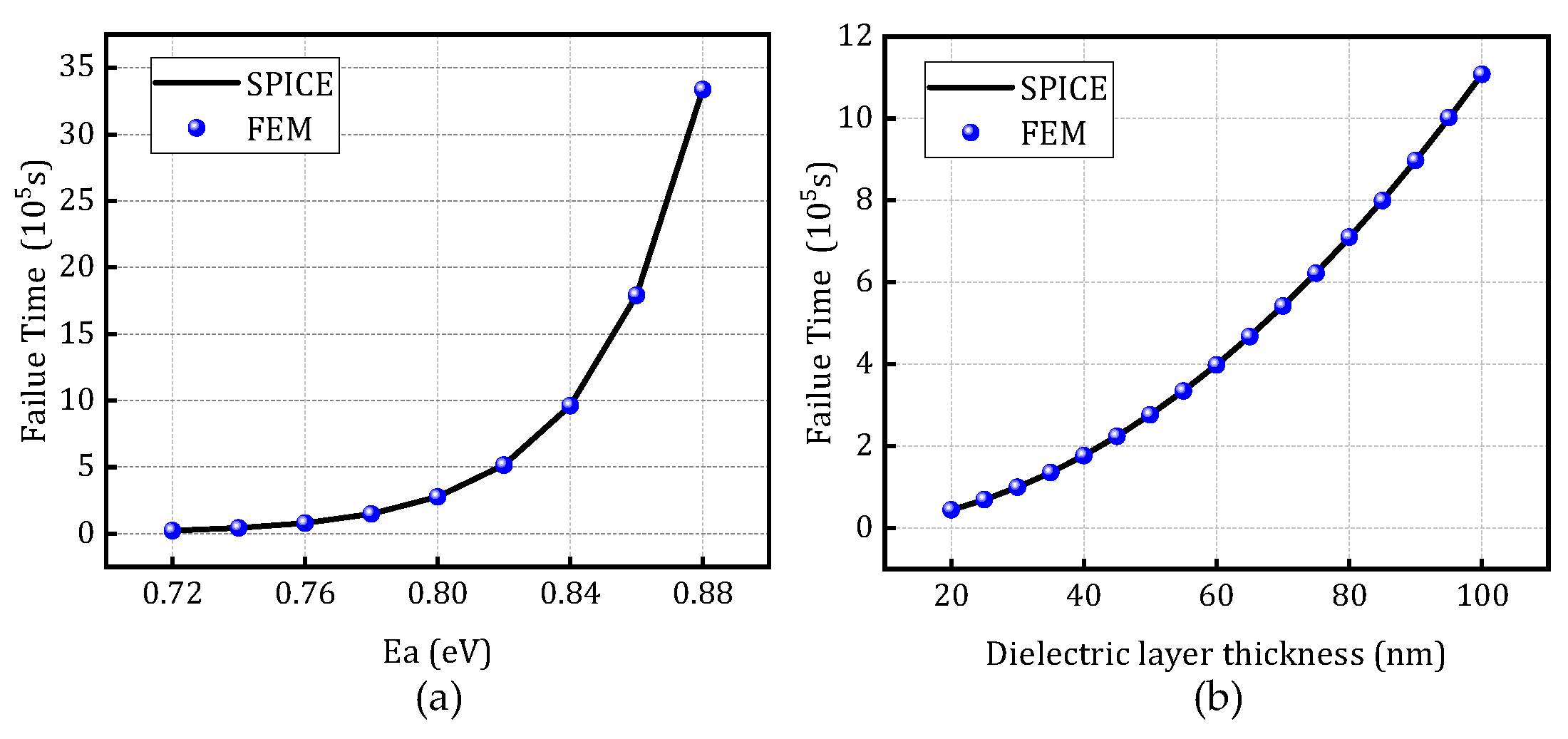

To validate the scalability of the constructed model,

Figure 8 presents a comparison between the finite element simulation results and the resistance degradation model under varying activation energies and dielectric thicknesses, at a temperature of 370 K and voltage of 1 V, based on the SPICE degradation model.

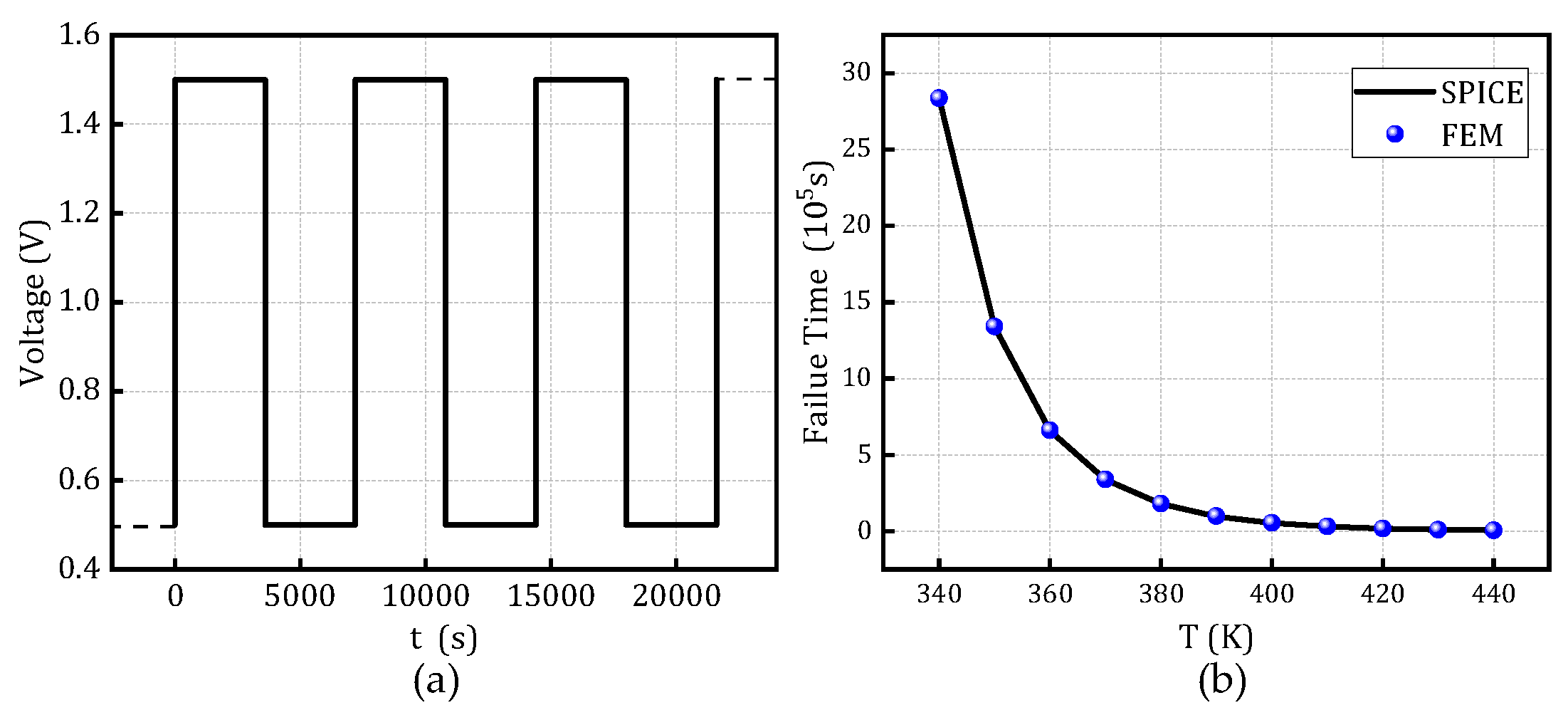

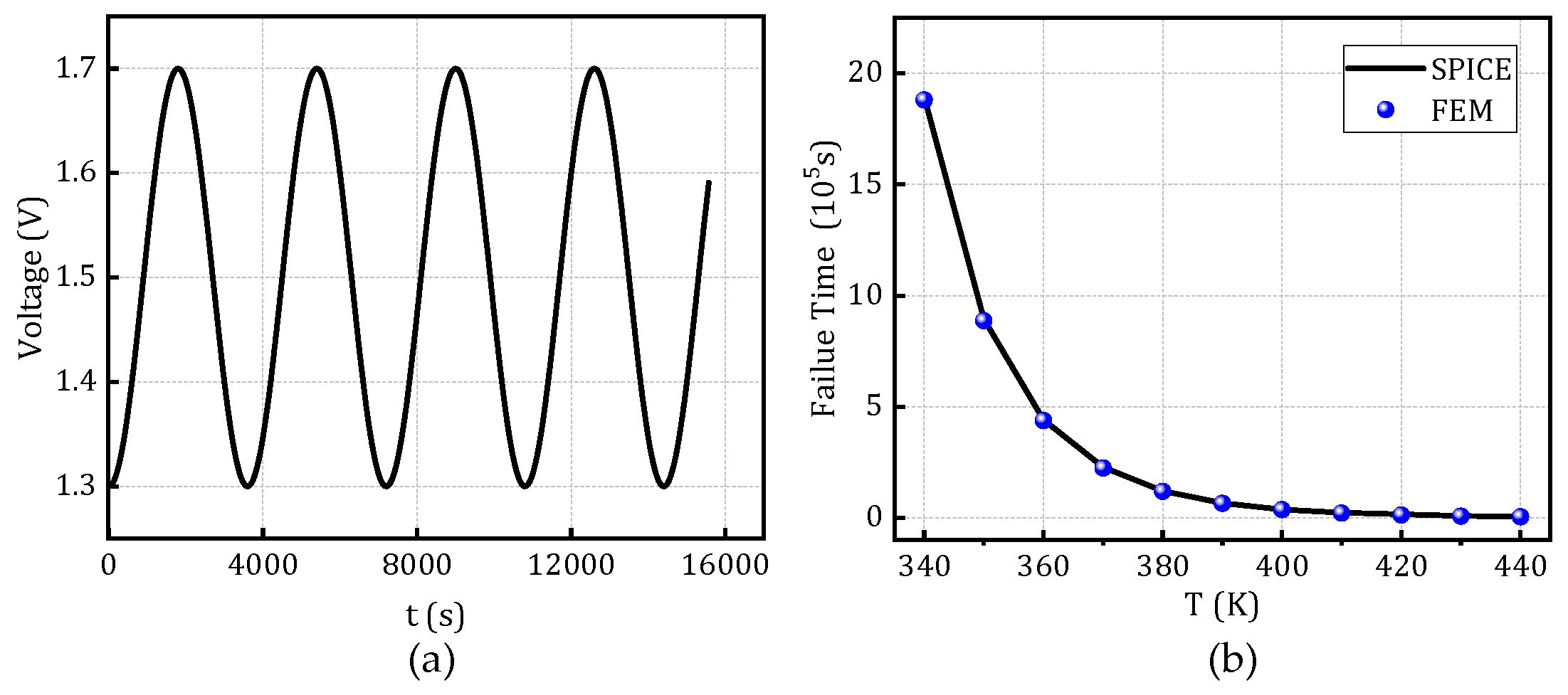

Figure 9 and

Figure 10 illustrate the comparison of time-to-failure under rectangular and sinusoidal voltage waveforms, respectively, at different temperatures while keeping all other parameters constant. These analyses aim to evaluate the applicability and robustness of the model under various operating conditions, demonstrating its adaptability to different stress scenarios.

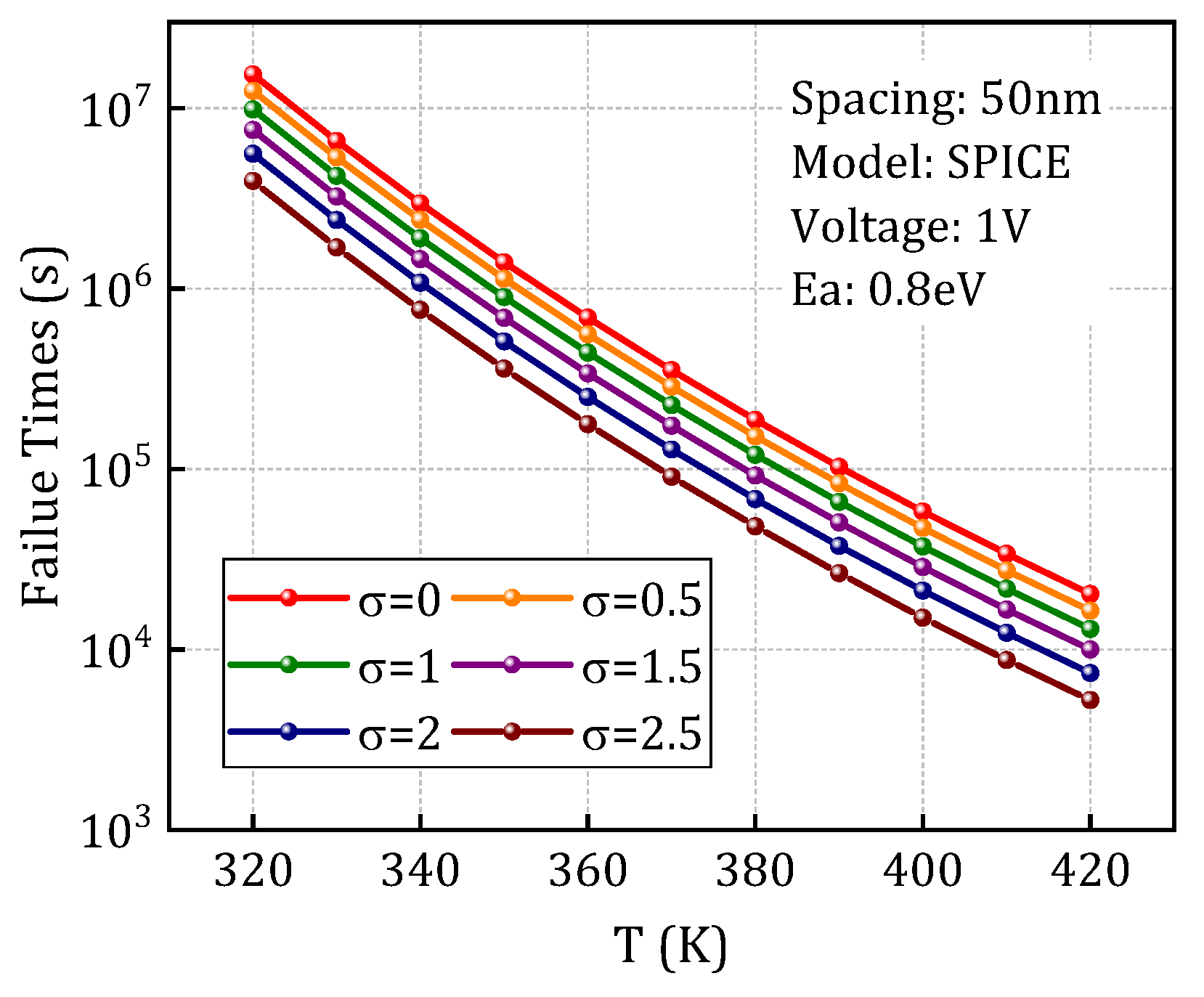

4.3. Analysis of Weibull Distribution Model Results

Further, the process tolerance model depicted in Section III-B is integrated to account for the influence of inevitable process variations on the degradation behavior of dielectric layers. By leveraging the statistical distribution characteristics of the PSD function, appropriate random seeds were generated to simulate the variability induced by LER. As shown in

Figure 11, the time-to-failure (TTF) was evaluated across different LER amplitude levels defined by the PSD function. The results reveal a pronounced reduction in failure time with increasing LER amplitude, indicating that LER accelerates the degradation process. As shown in

Figure 11, the TTF is evaluated across different LER amplitude levels defined by the PSD function. The results reveal a pronounced reduction in failure time with increasing LER amplitude, indicating that LER accelerates the degradation process. The results indicate that as the LER amplitude increases, the failure time decreases significantly, demonstrating the acceleration effect of LER on the degradation rate. This highlights the nonlinear amplification of microscopic geometric perturbations on macroscopic degradation behavior.

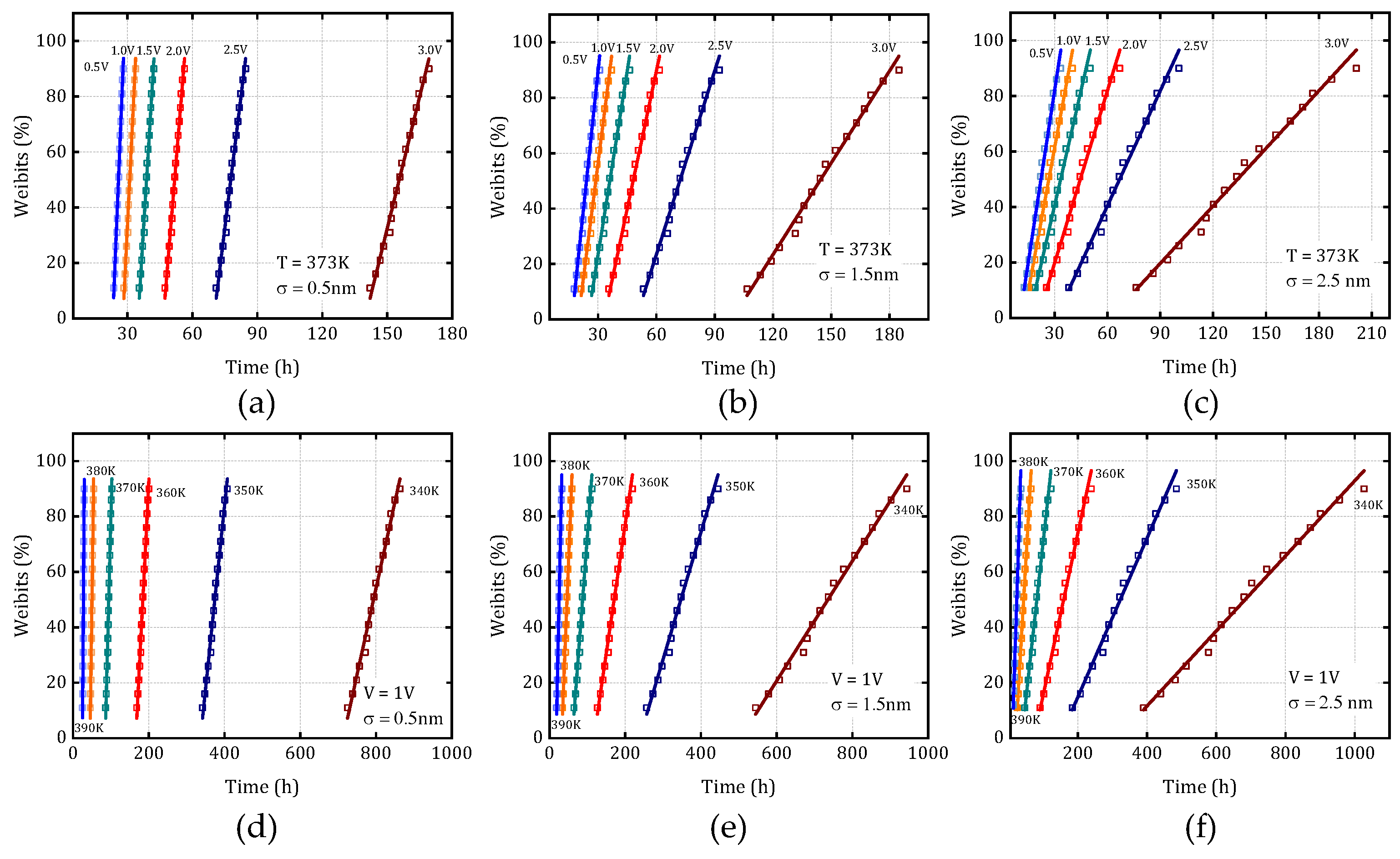

Subsequently, 100 independent random seeds are generated to perform multiple simulation trials. The resulting 100 TTF datasets are then sorted in ascending order. To mitigate the influence of extreme values on the statistical analysis, the lowest and highest 10% of the data points are excluded as outliers. The remaining 80 datasets are utilized to fit a Weibull distribution model, enabling the extraction of key statistical parameters characterizing the degradation behavior.

Figure 12 illustrates the Weibull distribution characteristics corresponding to different LER amplitudes under varying temperature conditions (Figures 12a–c) and voltage levels (Figures 12d–f). From these distributions, the characteristic failure time associated with a 63.2% cumulative failure probability-denoted as t

BD,63%- is extracted and defined as the dielectric layer’s failure time under each stress condition. The results demonstrate that variations in LER amplitude lead to significant shifts in the shape and scale parameters of the Weibull distribution. Furthermore, changes in temperature and voltage are shown to amplify the degradation model’s sensitivity to stochastic process variations. This highlights the pronounced impact of LER on the inherent randomness and uncertainty in the resistance degradation process. Importantly, it also reveals that environmental stressors such as temperature and voltage can markedly alter the statistical dynamics of TDDB degradation, emphasizing the necessity of incorporating both process variability and operational conditions into reliability modeling and prediction frameworks.

5. Conclusions

This paper proposes a SPICE degradation simulation model for the TDDB effect in dielectric layers within devices and packages, aimed at analyzing the TDDB behavior of dielectric layers in back-end processes. The model’s accuracy under various excitation conditions and dimensional parameters was validated through finite element simulations. Subsequently, a process tolerance model incorporating the power spectral density function was introduced to quantitatively characterize LER in the dielectric layer. Combined with 100 Monte Carlo simulation runs, the impact of LER on time-to-failure was further investigated. The results demonstrate that variations in LER amplitude significantly affect the shape and scale parameters of the Weibull distribution, while different temperature and voltage conditions further amplify the degradation model’s sensitivity to stochastic perturbations. By fitting these data to the Weibull distribution, the characteristic failure time tBD,63% under varying voltage, temperature, and LER amplitude conditions was obtained.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. Conceptualization, D.-W. W.; methodology, S.-C. Z. and D.-W. W.; software, S.-S. L.; validation, S.-C. Z., N. Y., and D.-W. W.; formal analysis, Y. J.; investigation, S.-C. Z. and Y.-H. S.; resources, Y.-H. S.; data curation, Y. J.; writing—original draft preparation, H.-G. W.; writing—review and editing, L. H.; visualization, H.-G. W.; supervision, D.-W. W.; project administration, L. H.; funding acquisition, S.-C. Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science Foundation of Zhejiang Province, grant number LD24F040005 and the Scientific Research Fund of Zhejiang Provincial Education Department, grant number Y202455375.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no competing interests.

References

- Long, Y.; Lv, M.; He, H. Failure Mechanism and Predictive Modeling for Microbump Interconnects Drop Life Under Diverse Impact Angles in Advanced Packaging. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Relib. 2024, 24, 241–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arriola, E.R.; Ubando, A.T.; Gonzaga, J.A.; Lee, C.-C. Wafer-Level Chip-Scale Package Lead-Free Solder Fatigue: A Critical Review. Eng. Fail. Anal., 2023, 144, 106986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tiwary, N.; Ross, G.; Vuorinen, V.; Paulasto-Krockel, M. Impact of Inherent Design Limitations for Cu–Sn SLID Microbumps on Its Electromigration Reliability for 3D ICs. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2023, 70, 222–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, K.-Y.; Na, S.; Kim, B.-J.; Lee, H.-J. Atomic Diffusion and Electrical Reliability of NiAl/SiO2 Interconnect: Breakdown Voltage and TDDB Characteristics. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2024, 30, 7981–7987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sune, J.; Wu, E.Y.; Lai, W.L. Statistics of Competing Post-Breakdown Failure Modes in Ultrathin MOS Devices. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2006, 53, 224–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chu, E.; Luo, Y.; Gupta, P. Design Impacts of Back-End-of-Line Line Edge Roughness. IEEE Trans. Semicond. Manufact. 2020, 33, 32–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.C.; Dunne, G.T.; Matocha, K.S.; Cheung, K.P.; Suehle, J.S.; Sheng, K. Reliability Issues of SiC MOSFETs: A Technology for High-Temperature Environments. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Relib. 2010, 10, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatheja, K.; Jin, X.; Strong, M.; Chen, D. Fast Gate Leakage Current Monitor With Large Dynamic Range. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II 2021, 68, 1690–1694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Peng, B.; Yuan, L.; Zhang, Y.; Jia, R. Impact of Process on Gate Leakage Current and Time-Dependent Dielectric Breakdown Failure Mechanisms of 4H-SiC MOS Capacitors. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2024, 71, 4039–4044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, I.; Chanawala, P.; Singh, R.; Sheikholeslam, S.A.; Ivanov, A. CMOS Reliability From Past to Future: A Survey of Requirements, Trends, and Prediction Methods. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Relib. 2022, 22, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aviñó-Salvadó, O.; Buttay, C.; Bonet, F.; Raynaud, C.; Bevilacqua, P.; Rebollo, J.; Morel, H.; Perpiñà, X. Physics-Based Strategies for Fast TDDB Testing and Lifetime Estimation in SiC Power MOSFETs. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2024, 71, 5285–5295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vecchi, S.; Padovani, A.; Pavan, P.; Puglisi, F.M. From Accelerated to Operating Conditions: How Trapped Charge Impacts on TDDB in SiO₂ and HfO₂ Stacks. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Relib. 2024, 24, 194–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, H.-C.; Syu, J.-Y.; Wang, H.-H.; Liu, Y.-C.; Kao, K.-S.; Chang, T.-C. Power Cycling Modeling and Lifetime Evaluation of SiC Power MOSFET Module Using a Modified Physical Lifetime Model. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Relib. 2024, 24, 142–153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, J.R. The Lucky Electron Model for TDDB in Low-k Dielectrics. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Relib. 2016, 16, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vici, A.; Degraeve, R.; Kaczer, B.; Franco, J.; Van Beek, S.; De Wolf, I. A Multi-Energy Level Agnostic Approach for Defect Generation during TDDB Stress. Solid-State Electronics 2022, 193, 108298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vici, A.; Degraeve, R.; Franco, J.; Kaczer, B.; Roussel, P.J.; De Wolf, I. Analytical Markov Model to Calculate TDDB at Any Voltage and Temperature Stress Condition. IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2023, 70, 6512–6519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, S.; Zhou, H.; Kim, T.; Chen, H.-B.; Tan, S.X.-D. Physics-Based Compact TDDB Models for Low- k BEOL Copper Interconnects With Time-Varying Voltage Stressing. IEEE Trans. VLSI Syst. 2018, 26, 239–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, E.; Muralidhar, R.; Shaw, T.; Li, B.; Kim, A.; Stathis, J.; Bonilla, G. A New and Holistic Modelling Approach for Impact of Line-Edge Roughness on Dielectric Reliability. In Proceedings of the 2017 IRPS; IEEE: Monterey, CA, USA, April, 2017; pp. 5B-5.1–5B-5.8. [Google Scholar]

- Stucchi, M.; Roussel, P.J.; Tokei, Z.; Demuynck, S.; Groeseneken, G. A Comprehensive LER-Aware TDDB Lifetime Model for Advanced Cu Interconnects. IEEE Trans. Device Mater. Relib. 2011, 11, 278–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.Y.; Silvestre, M.C.; Selvam, A.; Ramanathan, E.; Ordonio, C.; Schaller, J.; Shen, T.; Yeap, K.B.; Capasso, C.; Justison, P.; et al. An Investigation of Process Dependence of Porous IMD TDDB. In Proceedings of the 2015 IRPS; IEEE: Monterey, CA, USA, April 2015; p. PI.1.1-PI.1.4.

- Shimeng Yu; Wong, H.-S.P. Compact Modeling of Conducting-Bridge Random-Access Memory (CBRAM). IEEE Trans. Electron Devices 2011, 58, 1352–1360.

- J. Guy et al., “Investigation of Forming, SET, and Data Retention of Conductive-Bridge Random-Access Memory for Stack Optimization,” IEEE Trans. Electron Devices, Nov. 2015,62,3482–3489.

- D. Kocaay, Ph. J. Roussel, K. Croes, I. Ciofi, Y. Saad, and I. De Wolf, “LER and spacing variability on BEOL TDDB using E-field mapping: Impact of field acceleration,” Microelectronics Reliability, Sep. 2017, 76–77, 131–135.

- Bashir, M.; Kim, D.H.; Athikulwongse, K.; Lim, S.K.; Milor, L. Backend Low-k TDDB Chip Reliability Simulator. In Proceedings of the 2011 IRPS; IEEE: Monterey, CA, USA, April 2011; p. 2C.2.1-2C.2.10.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of advanced interconnect with low-κ substrate and the related TDDB process.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of advanced interconnect with low-κ substrate and the related TDDB process.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of CF formation in dielectric layer. (a) Initial state, (b) ion migration process, (c) formation process, and (d) formed CF.

Figure 2.

Schematic diagram of CF formation in dielectric layer. (a) Initial state, (b) ion migration process, (c) formation process, and (d) formed CF.

Figure 3.

The definition of ion activation energy and migration barriers. (a) No external electric field, (b) migration towards BE under an external electric field, and (c) migration towards TE under an external electric field. a represents the effective hopping distance.

Figure 3.

The definition of ion activation energy and migration barriers. (a) No external electric field, (b) migration towards BE under an external electric field, and (c) migration towards TE under an external electric field. a represents the effective hopping distance.

Figure 4.

LER profile generated from Gaussian autocorrelation function.

Figure 4.

LER profile generated from Gaussian autocorrelation function.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the proposed TDDB SPICE modeling framework.

Figure 5.

Schematic diagram of the proposed TDDB SPICE modeling framework.

Figure 6.

Time-dependent in the MIM structure.

Figure 6.

Time-dependent in the MIM structure.

Figure 7.

Time-to-failure from FEM simulations under various temperatures and voltages.

Figure 7.

Time-to-failure from FEM simulations under various temperatures and voltages.

Figure 8.

Comparison of time-to-failure between the SPICE degradation model and fem: (a) different activation energies and (b) dielectric layer thickness.

Figure 8.

Comparison of time-to-failure between the SPICE degradation model and fem: (a) different activation energies and (b) dielectric layer thickness.

Figure 9.

Time-to-failure distribution of the SPICE degradation model and FEM under rectangular voltage waveforms at different temperatures.

Figure 9.

Time-to-failure distribution of the SPICE degradation model and FEM under rectangular voltage waveforms at different temperatures.

Figure 10.

Time-to-failure distribution of the SPICE degradation model and FEM under sinusoidal voltage waveforms at different temperatures.

Figure 10.

Time-to-failure distribution of the SPICE degradation model and FEM under sinusoidal voltage waveforms at different temperatures.

Figure 11.

Comparison of time-to-failure at different amplitude values under varying temperatures.

Figure 11.

Comparison of time-to-failure at different amplitude values under varying temperatures.

Figure 12.

(a–c) Weibull distributions for different σ values under varying voltages and (d–f) Weibull distributions for different σ values under varying temperatures, Markers represent simulation data, and lines correspond to fitted Weibull distribution curves.

Figure 12.

(a–c) Weibull distributions for different σ values under varying voltages and (d–f) Weibull distributions for different σ values under varying temperatures, Markers represent simulation data, and lines correspond to fitted Weibull distribution curves.

Table 1.

Input Parameter Values of the EPG Model.

Table 1.

Input Parameter Values of the EPG Model.

| Param |

Values |

Units |

|

0.8 |

eV |

|

2.9 |

- |

|

370 |

K |

|

2.24⨯10-11

|

m2/s |

|

1.38⨯10-23

|

- |

|

1 |

V |

Table 2.

Input Parameters of the SPICE Degradation Model.

Table 2.

Input Parameters of the SPICE Degradation Model.

| Param |

Values |

Units |

|

2.86 |

eV |

| k |

1.38e-23 |

J/K |

|

0.2 |

nm |

|

1 |

- |

|

1.6e-19 |

C |

|

0.9 |

- |

|

5e12 |

Hz |

Table 3.

Relative Error Between the SPICE Degradation Model and FEM.

Table 3.

Relative Error Between the SPICE Degradation Model and FEM.

| T(K) |

Voltage (V) |

R.E% |

T(K) |

Voltage (V) |

R.E% |

| 350 |

0.5 |

1.39 |

410 |

0.5 |

1.18 |

| 350 |

1.0 |

1.19 |

410 |

1.0 |

1.81 |

| 350 |

1.5 |

0.99 |

410 |

1.5 |

1.81 |

| 350 |

2.0 |

0.52 |

410 |

2.0 |

0.55 |

| 350 |

2.5 |

1.66 |

410 |

2.5 |

1.02 |

| 350 |

3.0 |

2.12 |

410 |

3.0 |

1.02 |

| 370 |

0.5 |

0.49 |

430 |

0.5 |

1.37 |

| 370 |

1.0 |

0.90 |

430 |

1.0 |

1.68 |

| 370 |

1.5 |

0.68 |

430 |

1.5 |

1.84 |

| 370 |

2.0 |

0.45 |

430 |

2.0 |

0.84 |

| 370 |

2.5 |

0.20 |

430 |

2.5 |

0.90 |

| 370 |

3.0 |

0.81 |

430 |

3.0 |

1.60 |

| 390 |

0.5 |

1.18 |

450 |

0.5 |

0.93 |

| 390 |

1.0 |

1.81 |

450 |

1.0 |

2.38 |

| 390 |

1.5 |

1.81 |

450 |

1.5 |

1.77 |

| 390 |

2.0 |

0.55 |

450 |

2.0 |

1.03 |

| 390 |

2.5 |

1.02 |

450 |

2.5 |

0.91 |

| 390 |

3.0 |

1.02 |

450 |

3.0 |

1.54 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).