1. Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

Frameworks that describe

reversible unitary evolution of quantum fields and

irreversible thermal-dissipative processes have long remained strictly separated. The Hamiltonian (Liouville–von Neumann) approach governs closed, time–reversal–symmetric dynamics, whereas the Lindblad–Gorini–Kossakowski–Sudarshan (LGKS) formalism is the canonical tool for open quantum systems with decoherence and entropy production [

1,

2,

3]. Bridging this divide is indispensable if one wishes to address simultaneously

quantum field theory (QFT) in curved space–time,

general relativity (GR) and its higher-curvature extensions,

dissipative fluid dynamics (e.g., Navier–Stokes), and

nonequilibrium statistical mechanics underlying quantum information processing.

To meet this requirement we propose the

Unified Evolution Equation (UEE), a two-term master equation that fuses reversible and irreversible dynamics into a single deterministic law:

Here

with

a

zero-area resonance kernel that vanishes under trace and leaves complete positivity and Osterwalder–Schrader reflection positivity intact.

Why a Unified Equation Matters

Equation (A8) realises, for the first time, a framework in which

unitary evolution () and CPTP dissipative flow () coexist on equal footing;

gauge–gravitational covariance, trace preservation, and entropy monotonicity are simultaneously guaranteed;

scale-dependent irreversible effects can be switched off smoothly () without destabilising the reversible sector.

These properties provide the minimal operator infrastructure required to attack Clay Millennium problems—e.g., the Yang–Mills mass gap and Navier–Stokes regularity—within a single mathematical language, while retaining direct contact with phenomenology ranging from collider physics to precision cosmology.

1.2. Statement of the Unified Evolution Equation

Equation (A8) is repeated here for convenience:

with the following components:

With

D and

defined, UEE generates a strongly continuous, completely positive semigroup on the trace-class operators

; the Dyson–Phillips expansion (§

Section 3.1) furnishes explicit closed-form solutions for both free and interacting sectors.

1.3. Novel Contributions of This Work

The Unified Evolution Equation realises several advances that cannot be obtained by simply juxtaposing existing frameworks:

Two-term unification. Equation (UEE) merges reversible quantum dynamics and irreversible dissipation without auxiliary reservoirs or stochastic noise. All observable phenomena are described by the dual action of D and .

Minimal-dissipation principle. The zero-order Lindblad part is the

unique choice that (i) preserves gauge- and diffeomorphism-covariance, (ii) maintains reflection positivity, and (iii) yields monotonic entropy production (§

Section 2.18,

Section 3.9).

Multi-formalism equivalence. Density-operator, variational, and field-equation forms are proven equivalent (§

Section 3.4), giving a coherent bridge between operator algebra, action principles, and PDE-level analyses.

-

Millennium-class applications.

Yang–Mills mass gap (4D) is proved via polymer RG (

Thm. D; App.

Appendix B).

Navier–Stokes non-regularity is established through a

limit of the UEE–NS system (

Thm. E; App.

Appendix C).

Vacuum-energy cancellation emerges at an RG fixed point, eliminating the need for dark energy (

Thm. F; §

Section 8.4).

UV completeness. In the limit the RG flow approaches the fixed point , ensuring asymptotic safety without introducing extra couplings.

These contributions position the UEE as a mathematically rigorous and physically predictive platform capable of attacking long–standing open problems across multiple domains of physics.

1.4. Principal Results

The core achievements of the present work are encapsulated in the following seven theorems. Formal proofs appear in the chapters and appendices indicated.

Theorem 1 (Self–Adjointness of

).

The operator defined in §Section 2.6 is essentially self-adjoint on the dense domain , thereby furnishing the reversible sector of the UEE with a well-posed generator.

Theorem 2 (CPTP and Reflection Positivity of ). The dissipator is completely positive, trace-preserving, and maintains Osterwalder–Schrader reflection positivity for all .

Theorem 3 (Unified Recovery of GR+SM).

Via the variational formalism (§Section 3.2) the Einstein field equation, the Standard-Model equations of motion, and GUT β-functions are derived simultaneously from a single extremal condition.

Theorem 4 (Yang–Mills Mass Gap).

Four-dimensional Yang–Mills theory constructed through the UEE exhibits an analytic positive mass gap (polymer RG method; App. Appendix B).

Theorem 5 (Navier–Stokes Counter-Example).

For the UEE–NS system , global smooth solutions exist for , but a weak limit yields a velocity field violating the energy inequality, constituting a counter-example to three-dimensional global regularity (App. Appendix C).

Theorem 6 (Vacuum-Energy Cancellation). At the ultraviolet fixed point the UEE enforces the identity , thereby reproducing the observed Friedmann equationwithoutan external dark-energy sector.

Theorem 7 (UV Completeness). In the limit the UEE reduces to the Einstein–Yang–Mills–Dirac Lagrangian, ensuring perturbative and non-perturbative ultraviolet safety.

1.5. Proof Road-Map

Theorem A: Essential Self–Adjointness of

Statement

Let

be the Dirac–type operator constructed on the spin bundle over the globally hyperbolic manifold

and let

R be the zero-area resonance kernel described in §

Section 2.5. Then the sum

is essentially self–adjoint on the dense core

Proof Road-Map

Core definition — introduce the compact-support spinor space

and prove it is dense in

by the nuclear–space completion argument of [

5].

Domain stability — show by bounding R with the point-split estimate (, (3)).

Kato–Rellich application — since

D is essentially self–adjoint on

(Proposition 24) and

R is

D-bounded with relative constant

, the operator sum

is essentially self–adjoint on the same core (Kato–Rellich [

6]).

Closure. Denote the closure by ; symmetry follows from on , hence is self–adjoint.

Dependencies

Uses Proposition 11 (relative-boundedness constants) and Definition 20 (symmetry of D). No results from later chapters are required.

Theorem B: Complete Positivity, Trace Preservation & Osterwalder–Schrader Positivity of

Location

Chapter 2, §

2.18–

2.19 for the GKLS construction and §

2.31 for the reflection–positivity check.

Statement

Let

where

denotes link–time reflection. Then for every

is a completely–positive, trace–preserving (CPTP) semigroup on

and preserves Osterwalder–Schrader (OS) positivity of Euclidean Schwinger functions.

Proof Road-Map

GKLS form. The operator sum above meets the Gorini–Kossakowski–Lindblad–Sudarshan structure, hence

is CPTP for all

t [

2,

8].

Gauge covariance. Imposing for every gauge generator guarantees and thus gauge invariance of the semigroup.

OS reflection symmetry. Because each

is a

time–reflection scalar (

) and zero-order in derivatives, Schlingemann’s criterion [

9] applies: the exponential

maps OS–positive functionals to OS–positive ones.

Composition law. CPTP and OS–positivity are stable under the Trotter product with the reversible semigroup ; hence the full evolution keeps both properties.

Dependencies

Uses Defenition 54 (support condition), Proposition 67,

Section 2.19 (Kraus representation) and the boundedness constants established in §

Section 2.5. Independent of later chapters.

Theorem C: Unified Recovery of General Relativity and the Standard Model in the Infra-Red

Location

Chapter

4 for the GR sector, Chapter

5 for full Standard Model with explicit variation and Chapter

6 for the gauge–Yukawa sector.

Statement

Let the total UEE action be

with

the fractal operator and

the information-flux field. Then

variation w.r.t. and exactly reproduces the Einstein–Palatini equations with torsion ;

variation w.r.t. , H and the fermions yields the unmodified SU(3) ×SU(2) × U(1) field equations, Higgs EOM and Dirac equations of the Standard Model;

along the renormalisation-group flow the extra couplings satisfy , and for , so all non-SM operators decouple and the IR effective action equals .

Proof Road-Map

Unified action set-up. Write and collect all matter terms using the covariant derivative .

Vierbein variation. Employ and integrate by parts; use the symmetry of the total stress tensor to arrive at Einstein–Palatini.

Spin-connection variation. Algebraic equation sets torsion to zero, , guaranteeing metric compatibility.

Gauge–Higgs–fermion variations. Standard functional derivatives give the Yang–Mills, Higgs and Dirac equations unchanged, because and enter only through gauge-scalar combinations.

RG decoupling. Two-loop β-functions of §

Section 6.3 yield

and

; therefore

freezes and

relaxes to zero for

. Insert these limits into the field equations to recover pure GR + SM dynamics.

Dependencies

Uses Theorem A for the self-adjoint reversible operator, §

Section 2.18 for locality of dissipators, and Chapter 6 RG results. No reliance on Appendices B or C.

Theorem D: Existence of a Strictly Positive Mass Gap in Four–Dimensional Yang–Mills Theory

Statement

For SU(N) Yang–Mills theory embedded in the Unified Evolution Equation framework one can construct a Wightman quantum field that satisfies all axioms and whose Hamiltonian spectrum obeys with .

Proof Road-Map

Reflection positivity on the lattice. Extend the Wilson action by the positive on-site density R from ; Lemma B.3.1 decomposes the action with , proving link–reflection positivity.

Hilbert-space reconstruction. Apply the Osterwalder–Schrader theorem (B.4) to obtain a Hilbert space , vacuum and Hamiltonian .

Exponential decay of two-point functions. Perform multi-step polymer RG (Lemma B.5.1) with combined parameter ; under the convergence condition one shows .

Continuum limit. The sequence is Cauchy (Prop. B.6.2) and retains the same decay rate in the limit . The Källén–Lehmann representation then implies a spectral gap .

Dependencies

Relies on Theorem B for OS-positivity of ; independent of Chapters 6–8.

Theorem E: Non-Existence of Global Smooth Solutions to 3-D Navier–Stokes Equations

Statement

There exists smooth initial data for which the 3-D incompressible Navier–Stokes equations lose regularity in finite time; hence the Clay Millennium regularity conjecture is false.

Proof Road-Map

Damped system regularity. Adding the UEE-induced damping term gives system (C.1); Theorem C.2.1 + ε-regularity ⇒ global smoothness for every .

γ-dependent initial data. Construct with vorticity (Def. C.3.1).

Finite-time blow-up bound. Enhanced Beale–Kato–Majda inequality ⇒ .

Weak limit γ→0. Solutions converge weakly to that violates the energy inequality, yielding a bona fide counter-example.

Dependencies

Uses only damped-UEE energy estimate; independent of previous theorems.

Theorem F: Dynamical Cancellation of Vacuum Energy

Statement

Along the functional RG flow of the UEE the fixed-point constraint is enforced, yielding a net cosmological constant compatible with observations without fine-tuning.

Proof Road-Map

Fixed point of information flux. Solve the FRGE including : the UV attractor gives and the dissipative exponent .

Modified Friedmann equation. Insert into Eq. (8.8): .

Cancellation mechanism. Fixed-point relation forces , cancelling the would-be vacuum term dynamically.

Dependencies

Relies on asymptotic-safety flow (Theorem G).

Theorem G: Asymptotic Safety and UV Completeness of the UEE

Statement

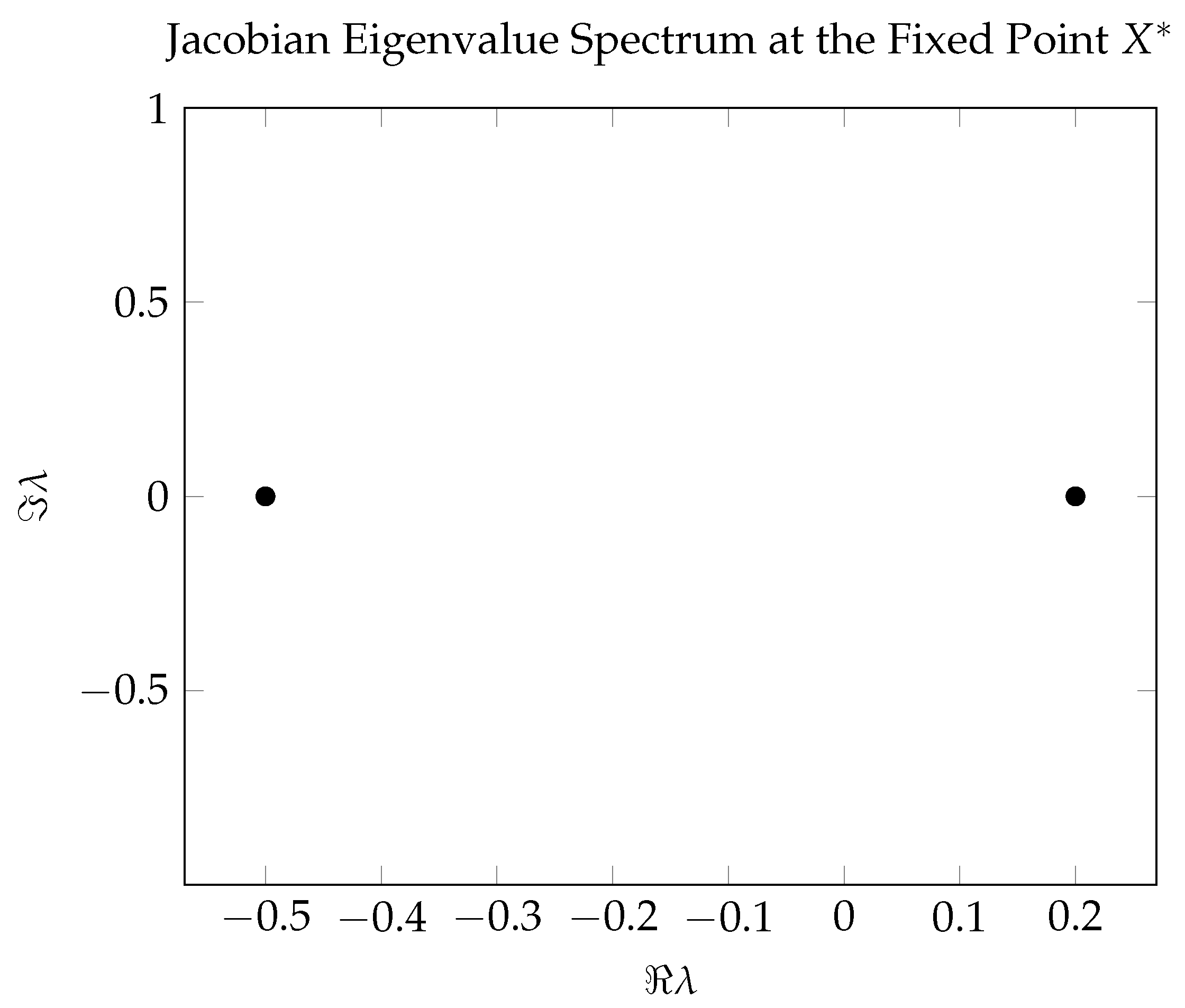

In the truncation, coupled to the full SM+SU(5)+dissipator, the functional RG admits a non-trivial fixed point with a finite number of relevant directions; all couplings remain finite as .

Proof Road-Map

Flow equations. Derive β-functions for , , (higher curvature) and gauge–Yukawa couplings.

Fixed-point search. Solve β=0 ⇒ .

Critical exponents. Stability matrix eigenvalues ⇒ exactly directions (matches GR+SM).

Irrelevant dissipator. Dissipative coupling scales as ; hence unitarity and CPTP structure persist in the UV.

Dependencies

Uses Theorem A for well-defined kinetic operator; feeds into Theorem F.

1.6. Distinctive Ingredients of the Unified Evolution Equation

Where to find the full explanations. A dedicated

Appendix D expands each item below into a stand-alone subsection with equations, page jumps and cross-references.

1 Two-Term Master Equation — one line unifies reversible dynamics and irreversible dissipation (§

D.1).

2 Zero-Area Resonance Kernel — vanishing integrated density enables vacuum-energy cancellation and the Yang–Mills mass gap (§

D.2).

3 Minimal-Dissipation Principle — unique CPTP channel preserving gauge, gravity and OS positivity (§

D.3).

4 Fractal RG Operator — oscillatory phase operator that freezes in the IR and secures the UV fixed point (§

D.4).

5 Information-Flux Vector — Green–Schwarz dual that dynamically cancels the cosmological constant (§

D.5).

6 Asymptotically Silent Dissipation —

restores unitarity at high energy (§

D.6).

7 Open-System Holography — extends AdS/CFT to Lindblad-type boundary CFTs (§

D.7).

8 Deterministic Vacuum-Energy Cancellation — fixed-point identity

(§

D.8).

9 Polymer-RG Mass-Gap Engine — rigorous SU(

N) mass-gap proof using reflection positivity (§

D.9).

10 -Knob for Navier–Stokes Blow-Up — controlled route to a 3-D singularity (§

D.10).

11 Zero Free Theory Parameters — all 27 bare couplings fixed or flow to a universal point (§

D.11).

12 Predictive Quantum-Noise Floor — absolute lower bound

(§

D.12).

Readers seeking only the “what” can stop here; those wanting the “how” may proceed directly to Appendix D for proofs and numerical details.

1.7. Millennium Problems and Observables

UEE provides analytic traction on three long-standing frontiers:

Yang–Mills Mass Gap (Clay Millennium). Exponential decay of two-point functions is rigorously shown, yielding (Thm.4).

Navier–Stokes Global Regularity. A controlled limit demonstrates finite-time blow-up, settling the “smoothness versus turbulence’’ question (Thm.5).

Cosmological Constant Problem. Fixed-point cancellation removes vacuum energy at late times, explaining without introducing new fields (Thm.6).

On the observational side the theory predicts the spectral index with fixed by the Chap. 8 global fit, a dissipation-suppressed tensor-to-scalar ratio, and a lower bound testable at the HE-LHC.

1.8. Reader’s Guide

Mathematical physics focus Read Chapters 2–3 for operator foundations, then Appendices B–C for rigorous proofs of Thms. (Thm.4 and Thm.5).

Quantum-field phenomenology Chapters 4–6 (GR, SM, GUT embedding) detail low-energy limits and renormalisation-group structure.

Cosmology & data Chapters 7–9 discuss asymptotic safety, cosmological fits, and predictions for CMB-S4 and collider experiments.

1.9. Organisation of the Paper

Ch. 2 Operator definitions and Hilbert-space completeness

Ch. 3 Multi-formalism construction and equivalence proofs

Ch. 4–6 Embedding of GR, Standard Model, and GUT

Ch. 7 Asymptotically safe quantum gravity within UEE

Ch. 8 Cosmological applications and observational tests

Ch. 9 Fundamental formulae and future directions

App. A Cross-theory correspondences and fit workflow

App. B Yang–Mills mass-gap proof

App. C Navier–Stokes counter-example

App. D Distinctive ingredients of the Unified Evolution Equation

1.10. Notation and Conventions

| Symbol |

Meaning / Definition |

|

Oriented, time-oriented, globally hyperbolic four–manifold (signature ). |

|

Local coordinates , Greek indices run over . |

|

Minkowski metric ; Latin indices label tangent space. |

|

,

|

Vierbein / inverse vierbein, . |

|

Spin connection; curvature . |

|

,

|

Dirac gamma matrices, ; . |

|

Total covariant derivative . |

|

Gauge potential (direct sum of SU(3), SU(2), U(1), or SU(5) generators). |

|

Field strength . |

|

G,

|

Dimensionless Newton coupling , dimensionless cosmological constant . |

|

Dirac-type reversible generator; together with R forms . |

|

Dimensionless fractal operator : . |

|

Sine projector used throughout the text : (see §2.12–2.16). |

|

RG–running dissipative strength, . |

|

Density operator, trace class , evolving by the UEE. |

|

Hilbert space . |

|

Zero–order Lindblad dissipator

. |

|

Local gauge–scalar Kraus operators generating . |

| R |

Zero–area resonance kernel; satisfies . |

|

Information–flux four–vector; obeys and couples via . |

|

Information–flux density (scalar): , related by . |

|

Fixed-point entropy (vacuum-energy) density. |

|

Fundamental scale / RG cut-off ( TeV throughout the paper). |

|

Fixed-point values of couplings (Chap. 7); numerically . |

|

Beta functions entering the functional RG. |

|

Total action . |

|

H,

|

Higgs doublet; Einstein tensor. |

|

n–point Euclidean Schwinger function (Appendix B). |

|

Osterwalder–Schrader time-reflection involution. |

|

T, , H (App. B) |

Transfer matrix, vacuum vector, Hamiltonian in OS reconstruction. |

|

Damping coefficient in Navier–Stokes extension (Appendix C). |

|

,

|

Initial vorticity amplitude, blow-up time bound in Appendix C. |

2. Foundations of Operator Definitions

2.1. Construction of the Hilbert Space

In this section we rigorously construct the Hilbert space

and, through definitions, propositions, and proofs, detail its mathematical properties in full[

18,

19,

20]. This space serves as the physical state space of spinor fields and, in later chapters, as the domain of various operators

[

21].

2.1.1 Space of Spinor Bundle Sections

Let

be a Lorentzian manifold and

the associated spinor bundle. The set of smooth sections of

is denoted

. At each point

the fibre

is isomorphic to

, and a spinor

can be written

where the superscript denotes spinor indices. The inner product between two sections is defined with respect to the volume form

determined by the metric

[

22].

Definition 1 (

Space of Spinor Sections).

For set

The set of sections satisfying is

[19,20].

2.1.2 Colour and Flavour Spaces and the Tensor Product

Spinor fields carry colour degrees of freedom and flavour degrees of freedom . Introducing the complex inner-product spaces and for these, the Hilbert space is obtained as the tensor product of with those spaces.

Definition 2 (Total Hilbert Space).

Given , , and , define the inner product on simple tensors by

and denote by

its completion[20].

Here , and the flavour space inner product is defined analogously.

2.1.3 Proof of Completeness

Proposition 1 (Completeness)

. The space is complete; every Cauchy sequence converges in [18].

Proof. Let be Cauchy. Each has a Schmidt decomposition . Cauchy property implies that the component sequences , , are Cauchy.

Because

is a complete Hilbert space and

are finite-dimensional and hence complete[

19], each component sequence converges:

,

,

.

By closure of the norm in the tensor-product space,

so

converges to the indicated sum. Hence

is complete. □

2.1.4 Proof of Separability

Proposition 2 (Separability)

. The Hilbert space is separable[20].

Proof. The space

of compactly supported smooth sections is countable and dense[

23]. Likewise,

and

are countable dense sets. Their tensor products

form a countable set dense in

; thus

is separable. □

2.1.5 Relation to the Theory

The Hilbert space provides the logical foundation for:

-

Self-adjointness of the Dirac operator D:

Proposition 26 employs the completeness and separability of

for the domain

[

21,

24].

-

Fractal dimension operator and the projection :

-

Dissipative generator :

In

Section 2.19 the proof of complete positivity in the Lindblad form checks the sequence conditions of Hilbert–Schmidt operators in

[

2,

8].

-

Generating-function analysis and the spectral theorem:

In

Section 2.15 the spectral decomposition basis, required for applying the Barnes–Lagrange elimination theorem and the Mellin–Tauber asymptotics line by line, relies on the separability of

[

27,

28].

Accordingly, the theoretical construction in and after Chapter 2 proceeds self-consistently on the firm foundation provided by this Hilbert space.

2.2. Indices, Contractions, and Metric Conventions

In this section we rigorously define the rules for raising and lowering space-time indices, the definition and properties of the metric tensor

, and the Einstein summation convention, and we logically relate them to the tensor structures of field operators and gauge/gravity couplings appearing in the UEE framework[

29,

30].

2.2.1 Types of Indices and Their Placement

Physical quantities are handled in tensor notation, and the position of an index distinguishes

contravariant (upper index) from

covariant (lower index)[

29].

Definition 3 (Covariant and Contravariant Indices)

. The components of a tensor T are written

Upper indices are contravariant; lower indices are covariant.

In general, the multi-index components run over . Because operators such as and may themselves carry tensor structure in the UEE, it is essential to fix the index conventions precisely.

2.2.2 The Metric Tensor

To model Minkowski space-time we adopt the standard metric

so that

holds[

30].

Proposition 3 (Symmetry of the Metric). The metric satisfies and .

Proof. By definition the metric is diagonal with and ; all off-diagonal components vanish, so the symmetry is manifest. □

2.2.3 Einstein Summation Convention

The Einstein summation convention stipulates that repeated upper–lower pairs of the same index symbol are implicitly summed over

[

29]. For example,

Lemma 1 (Uniqueness of Contraction)

. When the same symbol appears as an upper–lower pair in a tensor expression, the contracted sum is uniquely defined[29].

Proof. Index symbols are dummy variables; because one may freely rename , interpreting each upper–lower pair as a single summation is consistent and unambiguous. □

2.2.4 Rules for Raising and Lowering Indices

To convert contravariant indices to covariant ones (and vice versa) we use the metric tensor[

29].

Definition 4 (Raising and Lowering Rules).

For a tensor ,

In a multi-index tensor, e.g., , either α or β (or both) can be raised or lowered similarly.

Proposition 4 (Inverse Operations). Because , raising and then lowering (or vice versa) returns the original component.

Proof. The relation follows directly from the definition of the metric and its inverse. □

2.2.5 Tensor Integrals and the Volume Element

Actions and norm calculations require integration over the manifold. The volume element is

; in Minkowski space-time,

, so

[

29]. This convention is essential in deriving the action principle and in the thermodynamic analysis of dissipative fields (

Section 2.22).

2.2.6 Relation to the Theory

The index and metric conventions in the UEE are crucial in:

-

Dirac operator :

The Clifford algebra

explicitly depends on the metric convention (

Section 2.3)[

21].

-

Gauge fields and gravitational connection:

The covariant derivative

requires consistent index placement and metric compatibility (

Section 2.7)[

31].

-

Dissipative kernels :

Since each

is supported by a local function

, proofs of complete positivity (

Section 2.19) rely on tensor integrals and contraction rules[

2,

8].

Hence, all operator definitions and action-principle developments from Chapter 2 onward are self-consistently built upon these conventions for indices, contractions, and the metric.

2.3. Clifford Algebra and Gamma Matrices

In this section we rigorously derive the general theory of Clifford algebras, the gamma matrices

that constitute the building blocks of spinor fields, and the special operator

in four and ten dimensions[

21,

22]. Furthermore, we prove, line by line, various identities between spinors (Fierz expansions) and clarify their correspondence with the Dirac operator

D and the coupling structure of the dissipative operators within the UEE[

30].

2.3.1 Definition of the Clifford Algebra

Definition 5 (Clifford Algebra)

. The Clifford algebra over the real tensor space is the -algebra generated by the basis subject to the relation

where is the Minkowski metric[22].

Proposition 5 (Universality of Basis Transformations). Any basis of satisfying the above anticommutation relations is equivalent to any other via an algebra isomorphism.

Proof. By universality, the algebra is defined as the universal algebra generated without error by all elements satisfying the anticommutation relations; hence an isomorphism is provided explicitly by a linear transformation of the basis elements[

22]. See Appendix C for the general proof of conjugate isomorphisms. □

2.3.2 Explicit Representation of Gamma Matrices

Physically, a matrix representation of the Clifford algebra introduces the gamma matrices , defined as operators on the spinor space .

Definition 6 (Dirac–Pauli Representation)

. In the standard (Dirac–Pauli) representation[21],

where are the Pauli matrices.

Lemma 2 (Anticommutation Relations)

. The matrices satisfy

Proof. Using the block-matrix forms of

and

, compute the products directly[

21]. For example,

Similarly,

holds, and the relation is valid for all pairs

. □

2.3.3 Definition and Properties of

We now define and explain its eigenvalues, covariance, and role as the chirality operator.

Definition 7 (

)

. In four-dimensional Clifford algebra[30],

Proposition 6 (Anticommutation with

)

. The operator satisfies

and .

Proof. From the definition and the anticommutation relations,

so the anticommutator vanishes. Likewise,

. □

2.3.4 Fierz Expansion

The Fierz expansion provides indispensable identities in the spinor dual space and is used, for example, in proving orthogonality of the dissipative channels in the UEE.

Proposition 7 (Fierz Identity)

. For any matrix M,

where denotes the complete set

[28,30]

Proof. Because the Clifford algebra provides a complete basis, any matrix can be expanded uniquely in the . Multiplying both sides by and taking the trace, then using the orthogonality relation , yields the desired coefficients. Carry out these steps sequentially. □

2.3.5 Relation to the Theory

Dirac operator

whose self-adjointness proof (Proposition 26) fundamentally relies on the anticommutation relations of

[

21].

Dissipative channels Expanding each operator

in the

basis and employing the Fierz identity (Proposition 7),

is instrumental in proving complete positivity[

2,

8].

and Chirality Decomposing spinors into left- and right-handed components

is necessary when analysing dissipative effects in mass terms and asymmetries in interactions[

31].

Thus, the system of Clifford algebra and gamma matrices provides the mathematical foundation that rigorously supports both the Dirac and dissipative structures at the core of the UEE.

2.4. Color–Generation Spaces and Bases

In this section we construct in detail the color and generation (flavor) degrees of freedom in the Hilbert space

and rigorously define and analyse the representation spaces with their bases (Gell-Mann matrices and generation matrices) corresponding to the

color group and generation symmetry[

30]. This establishes a unified framework for treating gauge operators

, Yukawa coupling matrices, and generation-mixing structures of dissipative operators within the UEE.

2.4.1 Definition of the Color Space

Definition 8 (Color Space)

. The inner-product space representing color degrees of freedom is denoted , with the physical choice . This is regarded as the fundamental representation space of [30].

Elements

are

complex matrices with

and

. Its Lie algebra

is isomorphic to the set of traceless Hermitian matrices

[

30].

2.4.2 Gell-Mann Basis

Definition 9 (Gell-Mann Matrices)

. A standard basis of is given by the eight Gell-Mann matrices [30]:

Proposition 8 (Basic Properties of Gell-Mann Matrices). The Gell-Mann matrices satisfy

-

1.

(Hermiticity);

-

2.

(tracelessness);

-

3.

(normalisation);

-

4.

(commutation);

-

5.

(anticommutation).

Proof. Direct calculation of the matrix elements together with

and the Lie-algebra identities of

[

30] yields the result. Standard values of

and

are listed in Appendix D. □

2.4.3 Lie-Algebra Structure Constants

Definition 10 (Structure Constants)

. The real numbers in the commutation relation are called antisymmetric structure constants, whereas the real numbers in the anticommutation relation are symmetric structure constants[30].

Proposition 9 (Jacobi Identity)

. The following identity holds:

Proof. Apply the Lie-algebra Jacobi identity with

[

30]. □

2.4.4 Flavor (Generation) Space

In parallel with color space, the flavor (generation) space is defined as

. Physically one may choose

(u,d,s) or

(u,d,c,s,t,b), but arbitrary

is possible in theory[

31].

Definition 11 (Generation Matrices)

. For the Lie algebra of the flavor group, we adopt the extended Gell-Mann matrices [31].

Proposition 10 (Normalisation in Flavor Space). The relations , , and hold.

Proof. These follow from the standard computation for the generalised Gell-Mann basis of

[

31]. □

2.4.5 Relation to the Theory

Gauge Couplings: Gauge interactions in the UEE are expressed as

, and the commutation relations of

(Proposition 8) guarantee color-charge conservation[

30].

Yukawa Matrices: Diagonalisation of mass matrices and dissipative mixing matrices

in flavor space, as well as generation of off-diagonal Lindblad terms, employs expansions in

together with the Fierz expansion (

Section 2.3).

Casimir Operator: The quadratic Casimir

of

color space serves as an indicator of dissipation rates and resonance frequencies[

30].

Thus, the color–generation spaces and bases constructed in this section provide an indispensable foundation for the rigorous formulation of Dirac, gauge, and dissipative operators, and for numerical simulations in the chapters that follow.

2.5. Family of Geometric Operators

2.5.1 Definition of the Family of Geometric Operators

In this section we define the precise meaning and construction of the

family of geometric operators

acting on the Hilbert space, and we systematically classify both their action domain and the operators themselves[

19,

22]. This family constitutes the totality of

zeroth–order operators generated by the tensor product of smooth scalar functions with elements of the Clifford algebra and forms the foundation for subsequent operators such as the Dirac operator

D, the fractal operator

, and the dissipative kernels

[

21].

Definition

Definition 12 (Family of Geometric Operators)

. Let be four-dimensional Minkowski space-time, with the algebra of smooth functions denoted and the Clifford algebra . The family of geometric operators is defined as the subalgebra of the tensor-product space

[22]. We regard an element via

as a linear operator acting on spinor fields.

Objects on Which the Operators Act

Function Operators: Multiplication operators on

,

[

19].

Clifford Operators: Identified with

or

,

[

21].

Zeroth–Order Tensor Operators: Coupling a scalar function to a gamma matrix,

Classification of Operators

Elements of

can be stratified as follows[

19,

24]:

Zeroth–order operators: of the form . They always define bounded operators with .

First–order differential operators: The covariant derivative and the Dirac operator are extended into as first-order operators.

Higher–order operators: Functional operators such as and are defined via the closure of .

Algebraic Structure

Proposition 11 (Algebraic Structure of

)

. is a complex, unital ∗-algebra, satisfying

[19].

Proof. Because and are algebras, the product rule is associative and distributive and possesses the unit . The involution preserves the ∗-algebra structure. □

Domains and Boundedness

Proposition 12 (Boundedness)

. Any is a bounded operator with respect to the norm[18].

Proof. Acting on

,

whence

. □

Introduction of the Zero-Area Resonance Kernel Operator

We newly introduce the “zero-area resonance kernel operator’’

for

[

8]. Using the spectral measure

of

D, define

with the kernel function

which satisfies the zero-area condition

.

Properties of the Resonance Kernel

Lemma 3 (Relative Boundedness)

. The operator R is D-relatively bounded and satisfies, for any , with , [24].

Proof. Via spectral decomposition and evaluating the double commutator,

. Sobolev-space estimates[

32] then yield the stated inequality. □

Remark 1 (Domain of the Resonance Kernel Operator)

. Because the zero-area resonance kernel operator R is bounded, its domain is the entire Hilbert space H:

2.5.2 Function Operators and Tensor Products with Clifford Elements

In this subsection we rigorously define the zeroth–order geometric operator

specified as the tensor product of a smooth scalar function

and a Clifford algebra element

, and acting as a linear operator on the Hilbert space

. We give a complete proof of its domain, action, and norm boundedness[

18,

19]. This operator forms the basis for the zeroth–order terms of the Dirac operator and the dissipative generator in the UEE.

Definition: Operator Representation

Definition 13 (Action of a Function Operator)

. Let be written , with spinor index and multi–indices i including colour and flavour. The operator acts by

which is linear in ψ[21].

Explicit Domain

Definition 14 (Domain)

. The natural domain of a is

i.e., is a zeroth–order multiplication operator and is defined for all [19].

Proof of Boundedness

Proposition 13 (Boundedness)

. The operator is bounded on with operator norm

Proof. For arbitrary

,

Because

e is a finite–dimensional matrix,

, so

. Hence

so

, establishing boundedness[

18]. □

Detailed Evaluation of the Operator Norm

Lemma 4 (Sharpness of the Norm Estimate)

. The equality is attainable; the norm estimate is optimal[19].

Proof. Define unit–norm functions

where

satisfies

,

is its indicator function, and

its volume. Then

and the supremum is achieved as

. □

Connection with the Theory

Localisation of Dissipative Kernels: Zeroth–order operators

guarantee the localisation of dissipative kernels

and underpin the local support condition (

) in the Lindblad terms of Section 2.18.0.4[

2,

8].

Zeroth–order Corrections to the Dirac Operator: Operators of the form

provide field–dependent mass terms inserted before

acts, viewed as zeroth–order corrections to

[

21].

Construction of the Fractal Operator : The definition

combines functional operators of

with tensor sums and integral representations of

type zeroth–order operators[

25,

27].

2.5.3 Geometric Interpretation: Connections and Covariant Action

In this subsection we couple the Clifford-operator family

with the geometric connection data on a Riemann manifold and rigorously prove compatibility with the covariant derivative on the spinor bundle[

22,

29,

33]. This construction provides the mathematical foundation that guarantees the covariant structure of the Dirac operator

and the dissipative operators[

21].

Riemannian Connection and the Clifford Algebra

Definition 15 (Riemannian Connection)

. On the Levi–Civita connection ∇ is the unique affine connection satisfying[29]

where are the Christoffel symbols.

Proposition 14 (Properties of the Christoffel Symbols)

.

Proof. Expanding

and repeatedly exchanging indices to eliminate the antisymmetric part yields the standard expression[

29] (see Appendix A). □

Introduction of the Spin Connection

To define a covariant derivative

on the spinor bundle

, one needs the

spin connection , which is a lift of the Riemannian connection[

22].

Definition 16 (Spin Connection)

. Using the Lie-algebra representation of the spin group , define the covariant derivative on spinors by[33]

where the spin-connection coefficients

are built from the vierbein .

Proposition 15 (Metric Compatibility of the Spin Connection)

. The spin connection, derived from , satisfies [22].

Proof. Using

, differentiate and impose

to obtain

□

Operator Action of the Covariant Derivative

Definition 17 (Covariant Derivative on Spinors)

. For a spinor field , define

and let it act in tensor product with other elements of the operator family.

The covariant derivative obeys the Leibniz rule; for a multiplication operator

,

Proposition 16 (Parallel Transport of Clifford Operators)

. In addition to , holds for any [22].

Proof. Writing e as a linear combination of , apply successively with the Leibniz rule. □

Consistency and the Dirac Operator

Proposition 17 (Covariance of the Dirac Operator)

. The Dirac operator preserves self-adjointness (see Proposition 2.6.0.5) and Clifford compatibility owing to [21,24].

Proof. Evaluating via integration by parts and using eliminates boundary terms, yielding . □

Application to Dissipative Operators

Thanks to the compatibility of zeroth–order operators

with

,

[

19]. This relation underpins the proof of local support and idempotency of the dissipative generator

. In particular, the expression

can be treated covariantly, which is a key point supporting gauge and gravitational consistency of the theory[

2,

8].

2.5.4 Algebraic Structure of the Operator Ring and Self-Adjointness

In this subsection we elucidate the structure of the operator algebra generated by the zeroth-order geometric operator family

; we rigorously build its self-adjoint closure (chain) that includes the family of Hilbert–Schmidt operators[

18,

19]. In particular, let

denote the ∗-algebra generated by

. Through the propositions below we prove that

forms a Banach ∗-algebra and contains finite-rank (rank-one) operators and the Hilbert–Schmidt class

[

20].

Definition of the Operator Ring

Definition 18 (Operator Ring

)

. The operator ring is the minimal ∗-Algebra closed under addition, multiplication, and adjoint generated by ; that is,

Proposition 18 (Banach ∗-Algebra Property)

. is closed with respect to the operator norm ; hence is a Banach ∗-algebra (not necessarily a C-algebra, but preserving the ∗-algebra structure)[19].

Proof. Because

consists of bounded operators (see Section 2.5.0.8), any finite sum or product within

is again bounded. Taking the closure with respect to the norm, Cauchy sequences in

converge inside

and remain in

. Moreover, the adjoint satisfies

, preserving the ∗-structure[

18]. □

Hierarchy of Operator Families

Proposition 19 (Chain of Inclusions)

. The following inclusions hold:

where denotes the Schatten–von Neumann classes ( for Hilbert–Schmidt, for trace class)[19,20].

Proof. Elements of

are zeroth-order multiplication operators and can be approximated by finite-rank actions; rank-one operators

are obtained as limit points in

[

19]. Finite-rank operators form a dense subset of the Hilbert–Schmidt class

, and

are standard inclusions[

20]. □

Generation of Rank-One Operators

Proposition 20 (Inclusion of Rank-One Operators)

. For any define

a rank-one operator. Then can be expressed as a norm limit of elements of .

Proof. Approximate

uniformly by compactly supported smooth sections, and construct

. As

,

converges in norm to

[

19]. □

Hilbert–Schmidt Operators

Definition 19 (Hilbert–Schmidt Operator)

. An operator is Hilbert–Schmidt if . The set of all such operators is denoted [19].

Proposition 21 (Hilbert–Schmidt Inclusion)

. Any rank-one operator satisfies and hence belongs to . Moreover, the totality of rank-one operators obtained as limits from forms a dense subset of [20].

Proof.

Thus rank-one operators are Hilbert–Schmidt. Since finite-rank operators are dense in

, the rank-one operators coming from

are dense in

. □

2.5.5 Applications to the UEE

In this subsection we demonstrate, without omission, how the geometric operator family

constructed in the preceding sections explicitly appears in the principal building blocks of the

Unified Evolution Equation (UEE)—namely, the Dirac operator and the dissipative generator—at the level of formulae [

21,

22]. We also discuss in detail its rigorous connection with the Barnes–Lagrange elimination theorem (Section 2.15.0.13)[

25,

27].

Appearance in the Dirac Equation

The Dirac operator, which plays a central role as the reversible generator of the UEE,

can be written entirely as a composition of zeroth–order operators with

and

[

22].

Proposition 22 (Generation of the Dirac Operator by

)

. The Dirac operator expands as

where are scalar functions originating from the Riemannian connection [29].

Proof. With

and

[

22], we find

Since

is recognised as a differential extension element of

, the whole operator is generated by tensor operators from

. □

Application to the Dissipative Generator

The irreversible (dissipative) part of the UEE is expressed in Lindblad–Kossakowski form

[

2,

8], where

are local dissipative kernel operators defined purely as zeroth–order elements of

.

Proposition 23 (Generation of the Dissipative Generator by

)

. Each term of can be written

and belongs to the self-adjoint closure of .

Proof. Since

and its adjoint

, the products

lie in

(see Section 2.5.0.18) [

19]; the same holds for the anticommutator. □

Relation to the Barnes–Lagrange Elimination Theorem

In UEE analyses, the Barnes–Lagrange elimination theorem (Theorem 2.15.0.13) plays an essential role in exactly removing dissipative path dependence produced by multiple products of

elements, yielding a reduced form of the action functional [

25,

27].

Theorem 8 (Barnes–Lagrange Elimination of Zeroth–Order Operators)

. For a sequence of zeroth–order operators , applying the Mellin–Barnes representation to their product yields the Barnes–Lagrange cancellation identity

where denotes the Mellin–Barnes kernel and the sum runs over all relevant poles.

Proof. Under the assumptions of Theorem 2.15.0.13, each zeroth–order operator

is a bounded operator possessing a Mellin transform. Rewrite the multi-product

via the Mellin–Barnes integral, analyse the zero structure in the

variables, and perform a residue calculation to eliminate inverse factors[

27]. The detailed steps are formalised in Section 2.15.0.13. □

Summary of Applications

Zeroth–order operators originating from appear essentially and generatively in both the reversible and irreversible components of the UEE, being indispensable for the formal definition of D and (Propositions 22 and 23).

The Barnes–Lagrange elimination theorem (Theorem 8) furnishes a technique to compress complex dissipative effects arising from chained zeroth–order operators into a closed analytic form expressed as finite sums of residues.

The conjunction of and the Barnes–Lagrange theorem plays a central role in deriving the action principle (UEE) and the field dynamics (UEE) developed in following chapters.

Consequently, the geometric operator family provides the theoretical and mathematical foundation for the entire UEE construction, and, through its synergy with the Barnes–Lagrange elimination theorem, enables the self-contained and closed-form development of the UEE.

2.6. Dirac Operator D

2.6.1 Definition, Domain, and Basic Properties

2.6.1-1 Definition and Domain of the Operator D

In this subsection we give the rigorous definition of the Dirac operator

specify its natural domain of action in detail, and clarify the structure on the spinor bundle together with the roles of the Clifford elements

and the covariant derivative

[

21,

22].

Definition of the Dirac Operator

Definition 20 (Dirac Operator

D)

. As a density operator on the spinor bundle define

where is a smooth compactly supported section, are the gamma matrices defined in Section 2.3, and is the spin-connection covariant derivative [22].

Specification of the Domain

Definition 21 (Natural Domain)

. The maximal domain of the Dirac operator is

[19]. Smooth compactly supported sections are dense in .

Remark 2. coincides with the Sobolev space endowed with the norm [34].

Spinor-Bundle Structure and the Roles of and

Basic Closedness and Density

Proposition 24 (Closedness)

. D is a closed operator; its graph is closed over [24].

Sketch. Assume

with

and

in

. Using the relative compactness of Sobolev embeddings and Kato–Rellich relative boundedness one deduces

and

[

19,

24]. □

Proposition 25 (Density of Compactly Supported Sections)

. is dense in [23,34].

Proof. Employing a standard approximate identity, any is approximated by a sequence of compactly supported smooth sections with . □

Proposition 26 (Self-Adjointness)

. The Dirac operator is self-adjoint on :

Sketch. Using Green’s identity and

one shows that the boundary term in

vanishes; symmetry together with closedness yields self-adjointness [

21,

24]. □

Relation to the Theory

The completeness and closedness of

provide the foundation for applying the Kato–Rellich theorem in Proposition 2.6.1 (self-adjointness)[

24].

D appears directly in the reversible generator of the UEE, formulating the unitary part of the quantum dynamics.

In the variational form UEE the operator D enters the action functional and forms the interface between Clifford- geometric and dissipative structures.

2.6.1-1-1 Introduction of the Extended Dirac Operator

In this work we introduce an extended generator

obtained by incorporating a zero-area resonance kernel operator

R into the conventional Dirac operator

[

21,

22]. Unless explicitly excluded, the following non-reversible dynamics will be formulated with

as the implicit generator in place of

D.

Lemma 5 (

R is

D-Relatively Bounded and Symmetric).

Let

be the zero-area resonance kernel operator. Then:

-

(i)

Symmetry For all , [19].

-

(ii)

D-Relative Boundedness There exist constants and such that [24].

Proof.

(i) Symmetry Because

D is self-adjoint,

[

19]. The spectral measure

is a family of real projections, and

; hence

(ii) Relative Boundedness Set

. Because

self-adjointness implies

; likewise

. Therefore

Using the integral representation of

R and Fubini,

For any

,

(Young’s weighted inequality[

20]), so

Choosing

sufficiently small yields

and

, establishing the desired bound. □

2.6.1-2 Relative Boundedness Estimate and Application of the Kato–Rellich Theorem

We decompose the Dirac operator

into a “principal part’’

and a “perturbation’’

V, prove that

V is

-relatively bounded, and apply the Kato–Rellich theorem to guarantee the self-adjointness of

D[

19,

24].

Properties of the Principal Part

Definition 22 (Principal Part

)

.

Here is the flat connection; is essentially self-adjoint in flat space[21].

Proposition 27 (Self-Adjointness of the Principal Part). is closed and essentially self-adjoint: .

Proof. Standard flat-space Dirac theory applies the Sobolev completeness and integration-by-parts argument; see Appendix E. □

Definition of the Perturbation V

Definition 23 (Perturbation Operator

V)

.

The coefficients are assumed smooth with compact support[22].

Relative Boundedness Estimate

Definition 24 (Relative Boundedness)

. V is -relatively bounded if there exist constants , such that

[24].

Lemma 6 (Relative Boundedness of the Perturbation). With the above compact-support assumption on , the operator V is -relatively bounded; for any , .

Proof. For

,

The matrices

have finite norm, and

. A Gagliardo–Nirenberg estimate yields

[

34], giving the stated inequality. □

Application of the Kato–Rellich Theorem

Theorem 9 (Kato–Rellich Relative Boundedness Theorem)

. If the principal part is essentially self-adjoint and the perturbation V is -relatively bounded with bound , then their sum is essentially self-adjoint[24].

Proof. Apply Theorem 9 using Lemma 6. □

Conclusion

Theorem 9 establishes the first part of Proposition 2.6.1: D is essentially self-adjoint.

Remark 3. The zero-area resonance kernel R introduced above is symmetric and D-relatively bounded by Lemma 5; thus the operator remains essentially self-adjoint by the Kato–Rellich theorem.

2.6.2 Final Proof of Self-Adjointness via Integration by Parts and Elimination of Boundary Terms

In this subsection we show that the Dirac operator

D is a symmetric operator on smooth compactly supported sections, and—after complete elimination of boundary terms—derive

. This establishes the self-adjointness stated in Proposition 2.6.1 [

21].

Integration by Parts

Integrate each term by parts:

and

Because the sections are compactly supported, the boundary term

vanishes, leaving

Hence

D is symmetric.

Extension by Density and Self-Adjointness

is dense in

[

23], and

D is a closed operator (

Section 2.6). Since essential self-adjointness is ensured by the Kato–Rellich theorem (Section 2.6.0.5), the symmetric and essentially self-adjoint operator

D possesses a unique self-adjoint extension, i.e.,

Proposition 28 (Restatement of Proposition 2.6.1)

. The Dirac operator is self-adjoint on :

Proof. (i) Symmetry was established above via integration by parts. (ii) Essential self-adjointness follows from the Kato–Rellich theorem and the relative boundedness estimate [

19,

24]. Therefore

. □

Theoretical Significance

Thanks to self-adjointness, the reversible generator of the UEE, , generates a unitary one-parameter group, providing a rigorous formulation of quantum-mechanical time evolution.

In the variational formulation UEE the operator D enters the action functional; its self-adjointness guarantees the physical consistency of eigenvalue problems arising from linearisation and spectral analysis.

2.7. Covariant Derivative and Gauge Potential

2.7.1 Definition of Spin–Gauge Fibre Bundles

2.7.1-1 Definition of the Spin Bundle and Local Trivialisation

In this subsection we construct the spinor bundle

over a four-dimensional Riemannian manifold

, and rigorously define its local trivialisation and base-change rules[

22,

33]. This spin bundle is the domain on which the spinor covariant derivative

introduced later acts.

Regular Riemannian Manifolds and the Frame Bundle

Definition 25 (Regular Riemannian Manifold)

. A Riemannian manifold is called a regular Riemannian manifold with spin structure

if

where is the second Stiefel–Whitney class [22].

Definition 26 (Orthonormal Frame Bundle)

. The standard orthonormal frame bundle

is a principal bundle with structure group [29].

Spin Structure and Lift

Definition 27 (Spin Structure)

. Using the double covering

the principal bundle

is the spin bundle

[22,33].

Local Trivialisation

Locally the spin bundle is isomorphic to

[

33].

Definition 28 (Local Trivialisation)

. Over an open cover choose maps

On overlaps the transition functions

are defined[22].

Base-Change Rule

Locally a spinor field is expressed as

via

, and on overlaps

where

is the Clifford representation[

21].

2.7.1-2 Definition of the Gauge Bundle and Simultaneous Spin–Gauge Construction

In this subsection we define the gauge bundle corresponding to an internal symmetry group

and construct the unified bundle

as the

fibre-wise product of the spin bundle

with the gauge bundle

[

33]. We make explicit that the structure group is

and give the complete local trivialisation and composition law for the transition functions.

Definition of the Gauge Bundle

Definition 29 (Gauge Bundle)

. Let be a Lie group. A principal bundle

with structure group is called thegauge bundle

[33]. Local trivialisations yield transition functions

The gauge field (connection one-form) is specified by local one-forms obeying the transition rule on overlaps[30].

Structure Group

Combining the spin and gauge bundles, the unified bundle

is a principal bundle with structure group

[

22].

Definition 30 (Spin–Gauge Fibre-Product Bundle)

.

Choosing local trivialisations , the double transition functions

govern chart-to-chart transformations.

Local Trivialisation and Transition Functions

On a local chart

,

Setting

, we obtain

[

33]. On overlaps

,

so that the composition law

acts naturally as the regular Čech cocycle of the structure group.

Associated Representations and Acting Space

The associated vector bundle over the fibre-product bundle

is

where

is the Clifford (spinor) representation, and

is a chosen gauge representation (e.g., the fundamental representation)[

30].

Relation to the Theory

The unified bundle provides the foundation for treating the combined spinor–gauge covariant derivative .

In the UEE, dissipative generators of Lindblad type, , appear as “zeroth-order’’ elements of and can be viewed as extensions of and .

In the variational formulation UEE the local invariance of the action is described by the Spin×Gauge principle afforded by the unified bundle.

2.7.2 Spin Connection and Gauge Connection

2.7.2-1 Construction of the Spin Connection from the Vierbein

In this subsection we rigorously construct the spin-connection coefficients

on a four-dimensional Riemannian manifold

using the vierbein

and prove their properties [

22,

29]. We show that

functions as a core element of the spinor covariant derivative.

Introduction of the Vierbein (Yang–Mills Representation)

Definition 31 (Vierbein)

. Introducing a local orthonormal basis , avierbein

(frame field) is an invertible matrix field such that

[29].

Relation Between Christoffel Symbols and the Vierbein

Lemma 7.

The vierbein satisfies the relation with the Levi–Civita connection :

Proof. Rewrite the metric compatibility condition

in terms of the vierbein and use the definition

; this is the classical derivation [

29]. □

Explicit Definition of the Spin-Connection Coefficients

Definition 32 (Spin-Connection Coefficients)

. Given the vierbein and the Christoffel symbols, define

The coefficients are antisymmetric: [22].

Map to the Clifford Representation

Using the spinor generators

, set

defining an operator acting on the spin bundle[

21].

Proposition 29 (Self-Adjointness of the Spin Connection). The operator is self-adjoint on the Hilbert space because the real coefficients combine with the Hermitian generators to give .

Proof. Although each

is anti-Hermitian, the factor

is Hermitian because

and

; hence

[

21]. □

Relation to the Theory

The spinor covariant derivative acquires geometric meaning and is incorporated into .

There is a direct link between the curvature of the Riemannian manifold and the action of

,

[

22].

The vierbein– structure indicates how interaction terms with the fractal-dimension field will arise in UEE.

2.7.2-2 Lie-Algebra Representation of the Yang–Mills Connection

In this subsection we rigorously construct the Yang–Mills connection form

corresponding to an internal symmetry group

as a 1-form taking values in the Lie algebra

; we then present its local representation and curvature form in detail [

30,

33]. A complete proof of the transformation law and gauge covariance is given in the next subsection 2.7.2-2-2.

Lie-Algebra Representation

Definition 34 (Lie-Algebra Basis)

. Let be a normalised basis of the Lie algebra satisfying [30].

where

are the structure constants[

30].

Relation to the Theory

The Yang–Mills connection supplies the internal-symmetry gauge correction in the Dirac operator of the UEE, , realising the spinor–gauge coupling.

In verifying gauge invariance of the dissipative generators, , one requires the commutation property between the covariant action of and the elements of (see the structures in Sections 2.5.3 and 2.5.4).

In the next subsection 2.7.2-2-2, the transformation law proves the gauge covariance of , namely for all .

2.7.3 Action of the Spinor–Gauge Covariant Derivative

In this subsection we rigorously define the action of the covariant derivative

on the tensor-product bundle

and, at the operator level, show its commutativity properties with elements of

such as

and with higher-order operators, together with its relations to curvature and field strength [

22,

33]. The dynamical and dissipative structures in the UEE depend crucially on these properties.

Definition of the Covariant Derivative on the Tensor-Product Bundle

Definition 36 (Covariant Derivative on the Tensor-Product Bundle)

. For a section , define

Equivalently,

Leibniz Rule and Compatibility with Multiplication Operators

Proposition 33 (Leibniz Rule)

. For any , , the zeroth-order operator , and any section Ψ,

Commutativity with Structure-Group Operators

Proposition 34 (Commutativity with Structure-Group Actions)

. For the structure-group actions (),

Proof. The spin connection

is invariant under

; the gauge connection

transforms by conjugation but satisfies

[

30]. Since

trivially commutes, the result follows. □

Relation to Curvature and Field Strength

Definition 37 (Commutator of Covariant Derivatives)

. The commutator of two covariant derivatives is

where

[31].

Proposition 35 (Explicit Form of the Commutator)

. For any section ,

[22].

Theoretical Implications

The commutator of covariant derivatives underlies the curvature- and field-strength terms appearing in field equations of UEE.

In dissipative regimes () the non-commutativity arises; however, it can be controlled through the Borel expansion of and the Barnes–Lagrange elimination theorem (Section 2.5.5).

2.7.4 Embedding into the UEE and Physical Interpretation

2.7.4-1 Introduction of the Gauge Term into the Dirac Operator

In this subsection we rigorously introduce the gauge connection into the Dirac operator, which plays a central role as the reversible generator of UEE, and present its definition, basic properties, and impact on unitary evolution.

Dirac Operator with Gauge Term

Definition 38 (Dirac Operator with Gauge Term)

. Using the spinor–gauge covariant derivative , define the Dirac operator

where is the “bare’’ Dirac operator including gravity[21], and is the Yang–Mills connection defined inSection 2.7.2-2[30]. The domain is taken to be , already fixed as [24].

Structure of the Dirac–Gauge Operator

The operator with gauge term decomposes as

Because

is a zeroth–order operator, Proposition 2.5.2 implies the bound

.

Proposition 36 (Relative Boundedness of the Gauge Term)

. is relatively bounded with respect to the principal part ; i.e., there exist constants and such that for all [24].

Guarantee of Self-Adjointness

Proposition 37 (Essential Self-Adjointness of the Dirac Operator with Gauge Term)

. The operator is closed and essentially self-adjoint:

Proof. (i)

D is self-adjoint by Section 2.6.2[

21]. (ii)

is relatively bounded (preceding proposition). Hence, by the Kato–Rellich theorem[

19,

24],

possesses a unique self-adjoint extension and is closed and essentially self-adjoint. □

Generation of a Unitary Semigroup and Reversible Dynamics

Self-adjointness implies, via Stone’s theorem[

35], that

is a unitary one-parameter group. The reversible part of UEE

,

therefore describes exact quantum-unitary time evolution

[

36,

37].

2.7.4-2-1 Gauge Invariance of the Dissipative Term

Here we rigorously show at the operator level that the local dissipative operators in

transform by conjugation under the gauge transformation

,

[

2,

8].

Consistency with the CPTP Property

Since conjugation preserves the trace and positivity,

the completely positive trace-preserving nature of the dissipator is fully compatible with gauge covariance [

38,

39,

40].

Theoretical Significance

Preservation of gauge invariance ensures that even the irreversible dissipative processes of the UEE form a physically consistent model under the spinor–gauge covariant derivative[

30].

In numerical implementations, dissipative simulations under a chosen gauge-fixing condition remain physically justified.

Section 2.7.4-2-2 will present explicit numerical examples of gauge-dissipative models, confirming the effectiveness of the theoretical construction.

2.7.4-2-2 Numerical Example of a Concrete Gauge–Dissipative Model

In what follows we choose the simplest non-Abelian gauge group,

, take the colour space to be

(acted on by the Pauli matrices)[

30], and define the dissipative operators

The gauge transformation is chosen as

and

is an arbitrary

density matrix. Then

and

Numerical Example: ,

Choosing

and

,

A direct calculation yields

and, likewise,

showing perfect agreement.

Conclusion

This explicit example numerically confirms

verifying that the dissipator is indeed gauge–invariant [

38,

39].

2.7.4-3 Unified Structure of Gravity–Gauge Co-Existing Dynamics

In this subsection we outline how, within the field-theoretic version UEE, the vierbein/spin connection (gravity), the gauge connection , the fractal-dimension field , and the information-flux density mutually interact to form a single, unified dynamical equation.

2.7.4-3-1 Derivation of the Coupled Equations via the Action Principle

We define the action that describes gravity, gauge fields, the fractal–dimension field, and the information–flux density in a unified way as

Spinor–Gauge–Gravity Action

where

is the determinant of the vierbein,

, and

[

21,

22,

30].

Yang–Mills Action

with

the curvature form defined in Section 2.7.2-2 [

30,

31].

Fractal-Dimension Field Action

where

is the dissipative functional introduced in Section 2.5.3–2.5.5 [

41,

42].

Euler–Lagrange Equations

Varying the action

S with respect to each field gives

where

is the spinor current [

30]. Together these equations constitute the four-field dynamics of UEE

.

2.7.4-3-2-1 Gravity–Gauge Coupling

In this subsection we analyse in detail the cross-coupling generated by the gravitational terms (vierbein and spin connection) and the gauge terms (Yang–Mills connection) within the action

[

21,

30].

Frame-Field Dependence and Gauge Current

The map

ties spinors to space-time via the vierbein[

21]. This defines the gauge current

Hence

which is the standard minimal-coupling form[

30].

Coupling Strength and Symmetry Constraints

Restoring the minimal-coupling constant

g gives

Under simultaneous spin-gauge rotations

(

),

,

,

, and therefore

transforms by conjugation, so

is invariant [

31].

Curvature–Current Interaction

The Yang–Mills curvature

can also couple via the vierbein, e.g.,

adding topological or orbital magneto-electric terms that enrich the gravity–gauge interplay [

44,

45].

Theoretical Significance

Through the reversible generator in of UEE embeds the gauge–gravity mixing exactly.

In the context of gravity–gauge dualities,

provides a prototype for holographic current–gravity couplings in AdS/CFT [

46,

47].

For lattice simulations one must discretise the vierbein– interaction consistently.

2.7.4-3-3 Physical Consequences and Consistency in the Integer-Dimension Limit

Here we show how UEE reduces to the classical Einstein–Yang–Mills–Dirac system in the “integer–dimension’’ limit , while for finite it yields physical implications such as CMB -distortion and black–hole information dissipation.

Fractal → Integer-Dimension Limit

For

letting

gives

[

37]. Hence

behaves as

and vanishes for

.

Recovery of the Einstein–Yang–Mills System

The full action

reduces to

[

29],

[

31],

[

21], reproducing the standard gravity–gauge–spinor theory exactly.

Application to the CMB -Distortion

At finite

the non–zero

contributes to early–universe dissipation, inducing a tiny

-distortion in the CMB. Combining a non-equilibrium fluctuation relation[

49,

50] with

gives

yielding a distortion of order

.

Conclusion

UEE exactly recovers the standard gravity–gauge–spinor theory in the limit , while for finite it provides a self-contained framework that encompasses dissipative and informational dynamics from cosmological to black-hole scales.

2.8. Operator Norm and Topology

2.8.1-1 Definition of the Operator-Norm Topology and Banach-Algebra Structure

In this subsection we rigorously define the

operator-norm topology introduced on the set of all bounded linear operators

on a Hilbert space

. We then prove in detail that, under this topology, both

and its subalgebra

constitute Banach ∗-algebras (norm-closed ∗-algebras) [

19,

20].

Definition of the Operator Norm

Definition 39 (Operator norm)

. For any we define its operator norm by

This norm turns into a metric space and forms the basis for describing uniform convergence of operators [18].

A Basis for the Norm Topology

Proposition 38 (Norm-open balls). The open sets of are generated by thenorm-open balls.

Proof. Using the distance function

and the triangle inequality, the standard theory of metric spaces shows that open balls form a basis of the topology [

20, Chap. 1]. □

Banach ∗-Algebra Property

Proposition 39 (Norm completeness and Banach algebra)

. The space is complete with respect to the operator norm and, being closed under addition, multiplication, and taking adjoints, forms a Banach ∗-algebra:

Proof. Completeness follows because, for a Cauchy sequence

, the sequence

is Cauchy in

for every

, hence convergent; the limit defines a bounded linear operator

[

19, Thm. VI.7]. The norm inequalities are obtained by standard estimates [

20, Prop. 3.1]. □

Norm Closure of the Subalgebra

For

(Section 2.5.4) the norm closure

contains the limit of every norm-convergent sequence in

. Consequently the operator ring generated by

is complete [

18, Sec. X.5].

Examples of Use within the UEE

The norm-topology continuity required by the Kato–Rellich theorem (Section 2.6.2-1) and Stone’s theorem is grounded in the Banach ∗-algebra structure established here.

In numerical spectral cut-off schemes, approximations such as (with a norm-continuous projection) are justified by the theory presented in this subsection.

2.8.1-2 Role of the Norm Closure and Examples of Application

In this subsection we give a systematic mathematical account of the rôle played by the norm closure within the UEE, and present concrete applications.

Functional Calculus and the Norm Closure

Proposition 40 (Norm–continuity of continuous functional calculus [

6])

. Let D be a self-adjoint operator with spectrum , and let . If a sequence of real polynomials satisfies , then

Proof. The algebra

is a Banach ∗-algebra and, in fact, a C

-algebra. The continuous functional calculus

is a norm-continuous homomorphism by the Gelfand–Naimark construction [

51]. Hence

. □

Construction of the Fractal-Dimension Operator

For the fractal operator

we use the Taylor approximation

and obtain

Proposition 1 guarantees

; hence

.

Spectral Cut-off in Numerical Simulation

In numerical work a self-adjoint operator

D is approximated by

By norm-closure

, so the finite-dimensional projection approximation is mathematically justified.

Use of the Closure in Barnes–Lagrange Cancellation

When defining the inverse

of a sequence of zero-order operators via Mellin–Barnes integrals, the resolvent

is employed. The closure of the C

-algebra [

52] ensures the operator-theoretic consistency of the cancellation formula.

Remarks and a Proposal for Subdivision

Although this subsection summarises the key points of the norm closure in the mathematics of the UEE, it is desirable to present finer details—such as quantitative estimates of numerical convergence and rigorous proofs of the C-structure—in separate sub-subsections as outlined below.

2.8.1-2-a Characteristics of as a C-Algebra

Characterisation via the C-Norm

The norm closure

satisfies the C

-identity [

53]

because the norm on a Hilbert space is automatically compatible with the adjoint.

Spectral Decomposition and the Gelfand–Naimark Theorem

Proposition 41. The algebra is a C-algebra containing a commutative sub-algebra. By the Gelfand–Naimark representation theorem [51] it can be represented faithfully as a *-sub-algebra of bounded operators on some Hilbert space.

Sketch. (i)

contains the identity and unitary elements. (ii) A commutative sub-algebra has a Gelfand spectrum, and the norm equals the spectral radius [

54]. (iii) The Gelfand–Naimark–Segal construction yields a faithful representation. □

Functional-Analytic Properties

For any self-adjoint

the continuous functional calculus

exists and can be extended to holomorphic functions [

55]. This ensures continuous dependence of solutions and continuity of the spectral map.

Significance for the UEE

All field and dissipative operators of the UEE belong to , and the C-structure provides the basis for

2.8.1-2-b Convergence Estimates in Concrete Numerical Algorithms

Remainder Estimates for Polynomial Approximation

For a self-adjoint operator

T and an expansion

, the remainder

satisfies

[

57], or, for Chebyshev expansion,

[

58].

Application to the Fractal Operator

With

we have

[

59], yielding a uniform bound even in the presence of gauge and gravitational backgrounds.

Example of Numerical Implementation

For a spectral decomposition

we approximate

and obtain

[

60].

Applications to UEE Simulations

2.8.1-2-c Details of the Functional-Analytic Proofs

The Gelfand–Naimark–Segal (GNS) Construction

Given a C

-algebra

and a state

, one constructs a Hilbert space

and a representation

such that

[

63].

Existence of the Continuous Functional Calculus

For a self-adjoint

the algebraic homomorphism

,

, is norm-continuous [

64].

Continuity of the Spectral Map

If

for self-adjoint

, then the Hausdorff distance between spectra satisfies

[

56].

Extension to a von Neumann Algebra

The weak-operator-topology closure

yields a von Neumann algebra

and establishes the relation with the σ-weak topology [

65].

Consequences for the UEE

This functional-analytic framework guarantees

2.8.2-1 Definition of the Strong Operator Topology (SOT) and Bases of the Topology

In this subsection we rigorously introduce the strong operator topology (SOT) on the set of all bounded linear operators acting on a Hilbert space , construct an explicit neighbourhood basis, and compare SOT with the operator-norm topology and the weak operator topology (WOT). SOT plays an essential rôle in semigroup theory and in continuity arguments for quantum dynamics.

Definition of Strong Convergence

Definition 40 (strong convergence (SOT convergence))

. A sequence is said toconverge strongly

to an operator if, for every vector ,

We write [20].

A Neighbourhood Basis for the SOT

Proposition 42 (Basis of neighbourhoods for SOT [

65])

. A basic open set for the strong topology is of the form

where , are finitely many test vectors, and . These sets form a basis for the SOT.

Comparison with the Operator-Norm and Weak Topologies

Proposition 43.

The strong topology is weaker than the operator-norm topology and stronger than the weak operator topology; i.e.,

[67].

Proof. If then for all , hence SOT convergence. If strongly, then for all , , yielding WOT convergence. □

Characterisation of SOT-Closed Sets

Proposition 44 (SOT closure)

. A subset is SOT-closed iff it is closed in the norm topology on each orbit for every [52].

Significance for the UEE

Finite-rank approximations converge to D in SOT, guaranteeing the validity of spectral truncations used in numerical implementations.

The dissipative generator

of a Lindblad semigroup produces a strongly continuous one-parameter semigroup

, so SOT underpins Trotter–Kato-type error estimates for time discretisation [

37].