Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Material

2.2. Destructive Sampling

2.3. Biomass Composition

2.3.1. Extraction of Biomass Component

2.3.2. Cell Wall Constituents

2.3.3. Water Solubles

2.4. Calculation of Growth and Metabolic Rates

2.5. Trait-Trait Correlation

- is Spearman’s rank correlation coefficient,

- is the difference between the ranks of corresponding values,

- n is the number of observations.

2.6. Exaction of Proteins

2.7. Transcription Factor Identification and Annotation

2.8. Trait-Based Differential Expression Analysis

2.9. Protein-Protein Network Construction

2.10. Computational Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Growth and Sink Strength

| Trait | Fast_growth | Slow_growth | p-value 1 | significance |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dry weight | 27.15 | 21.46 | 0.03 | * |

| glucan | 14.52 | 12.86 | 0.47 | ns |

| hemicellulose | 12.24 | 8.08 | 0.06 | ns |

| lignin | 53.74 | 51.92 | 0.42 | ns |

| sucrose | 71.76 | 52.3 | 3.20E-05 | *** |

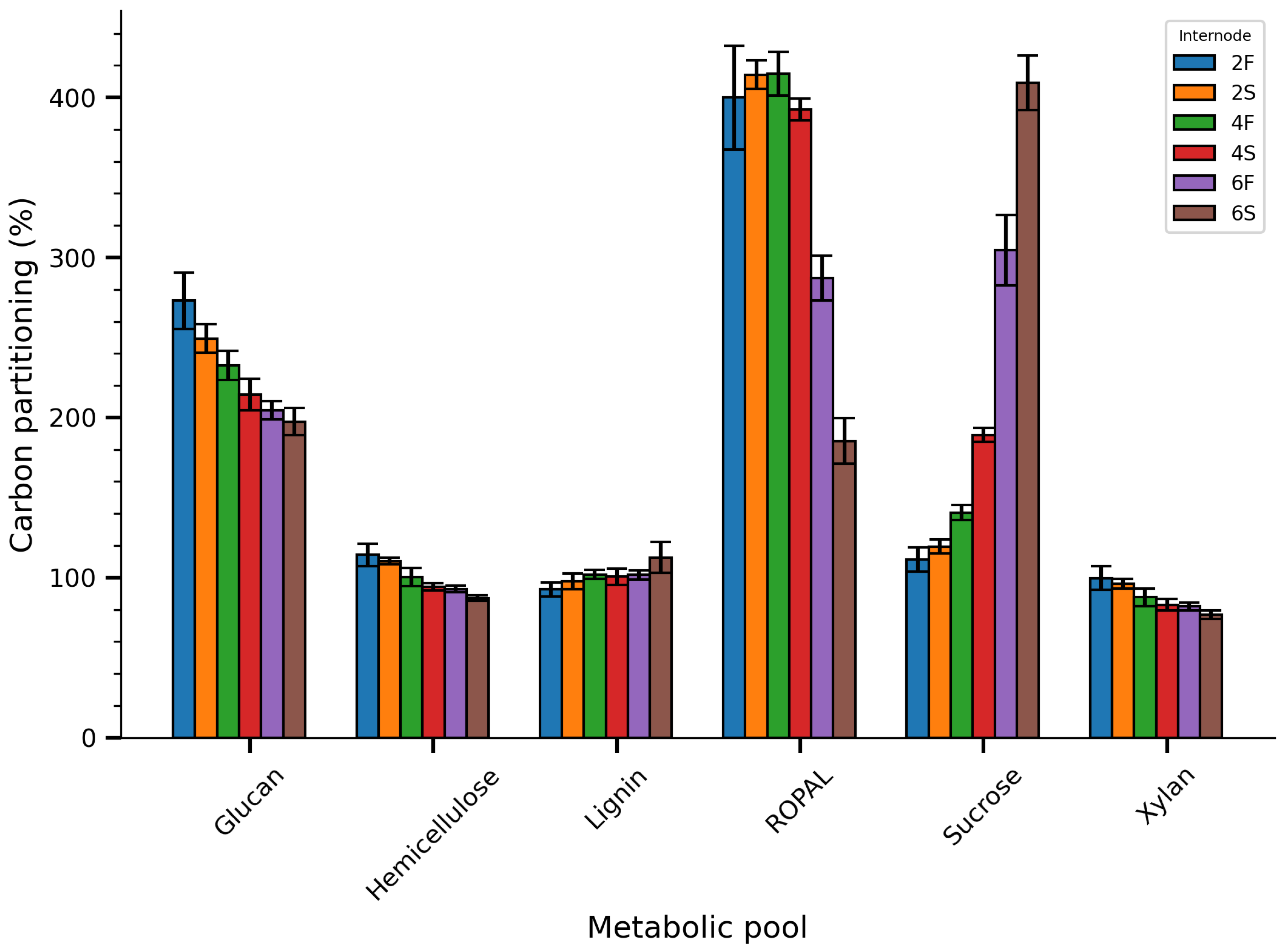

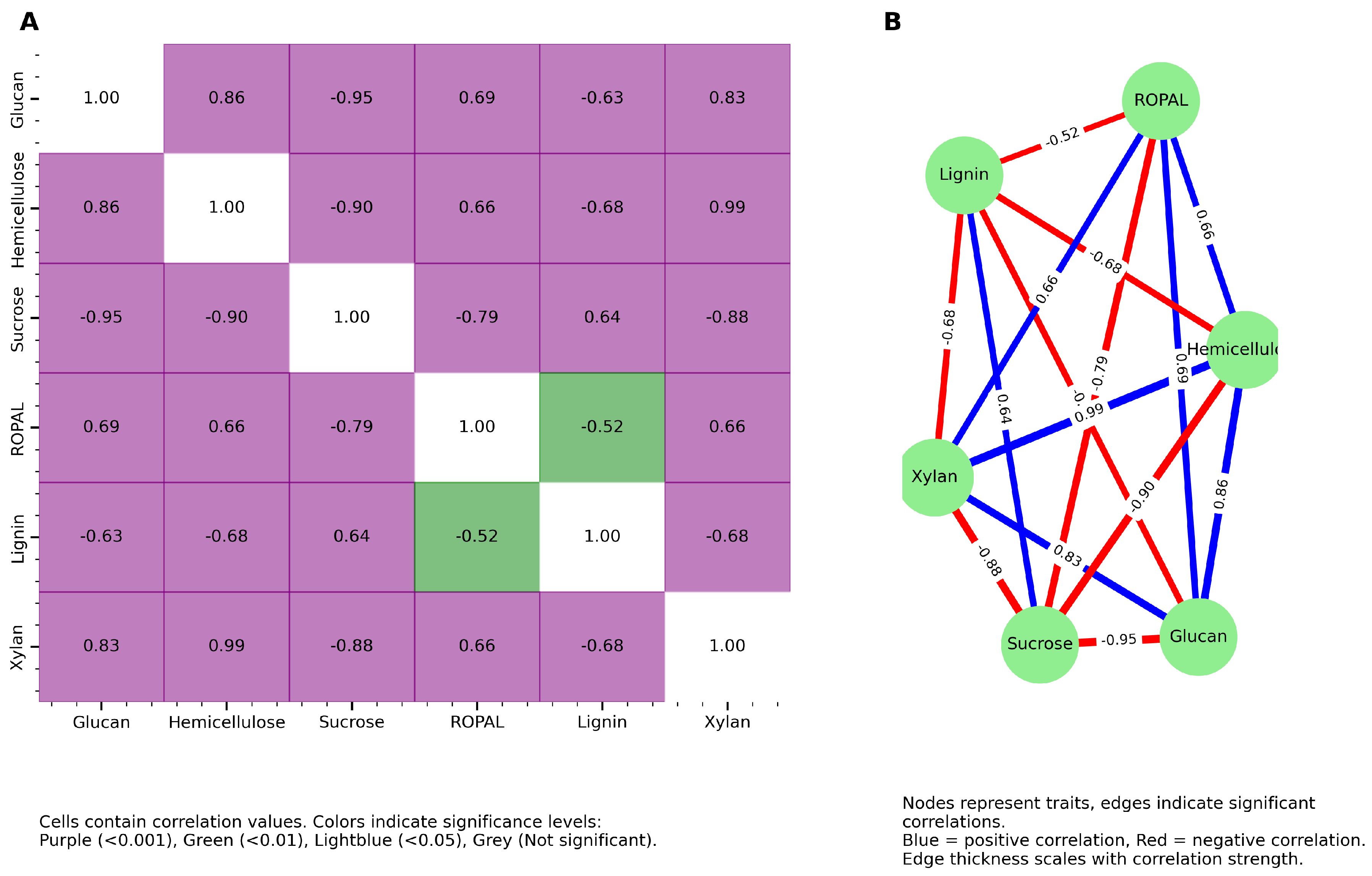

3.2. Carbon Partitioning and Trait-Trait Correlations

3.3. Transcription Factors

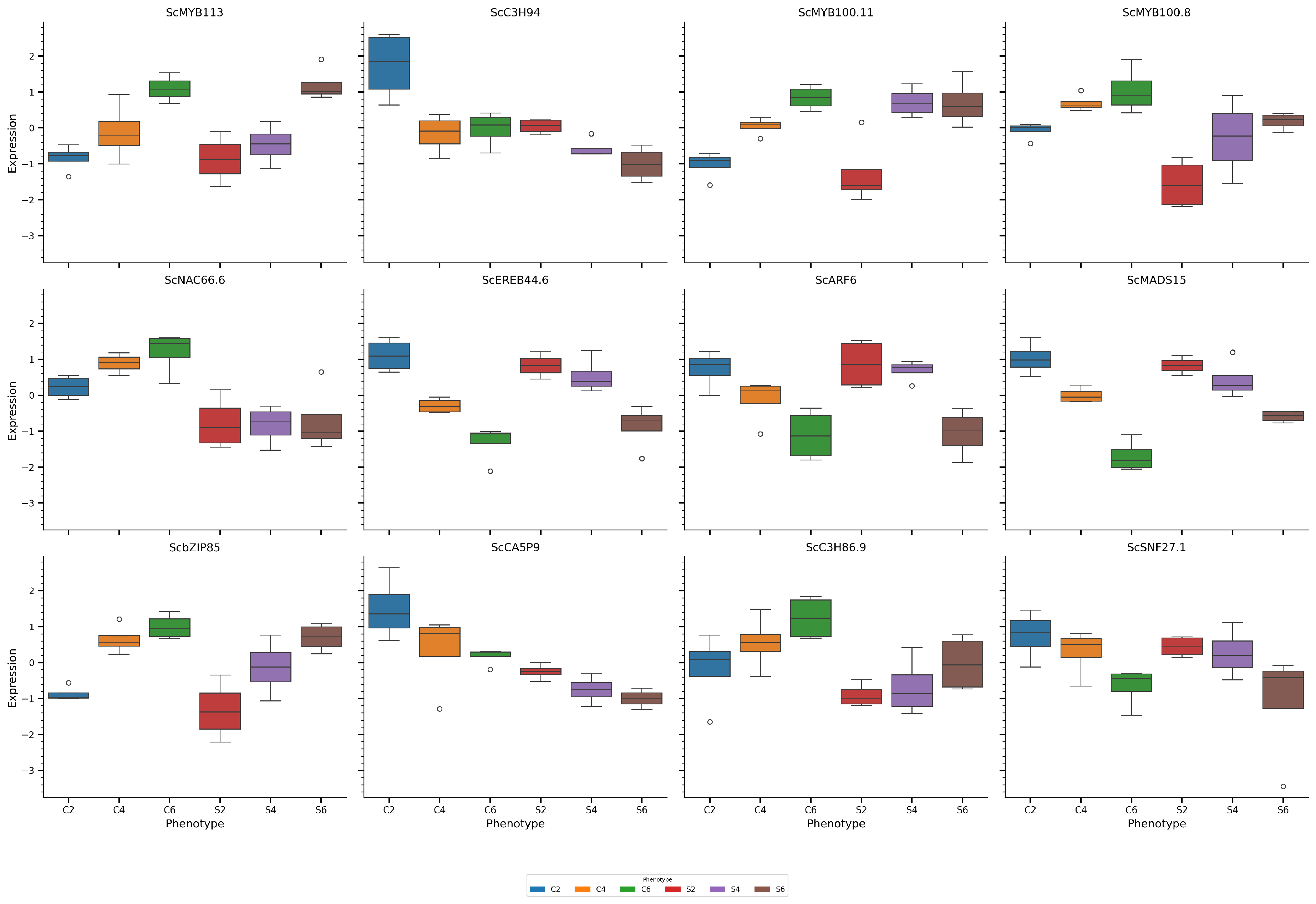

3.4. Transcription Factor Expression

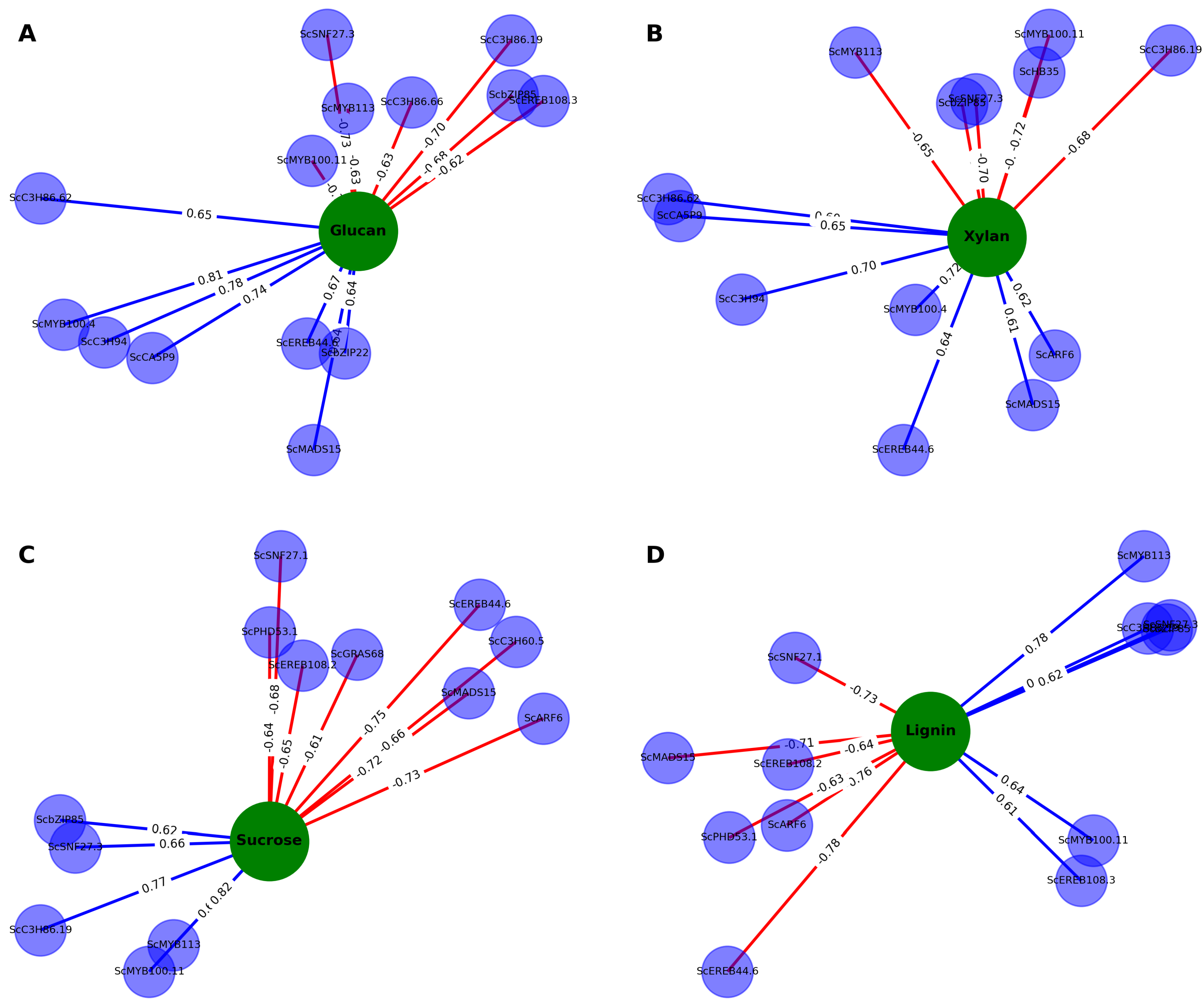

3.5. Protein-Trait Correlation

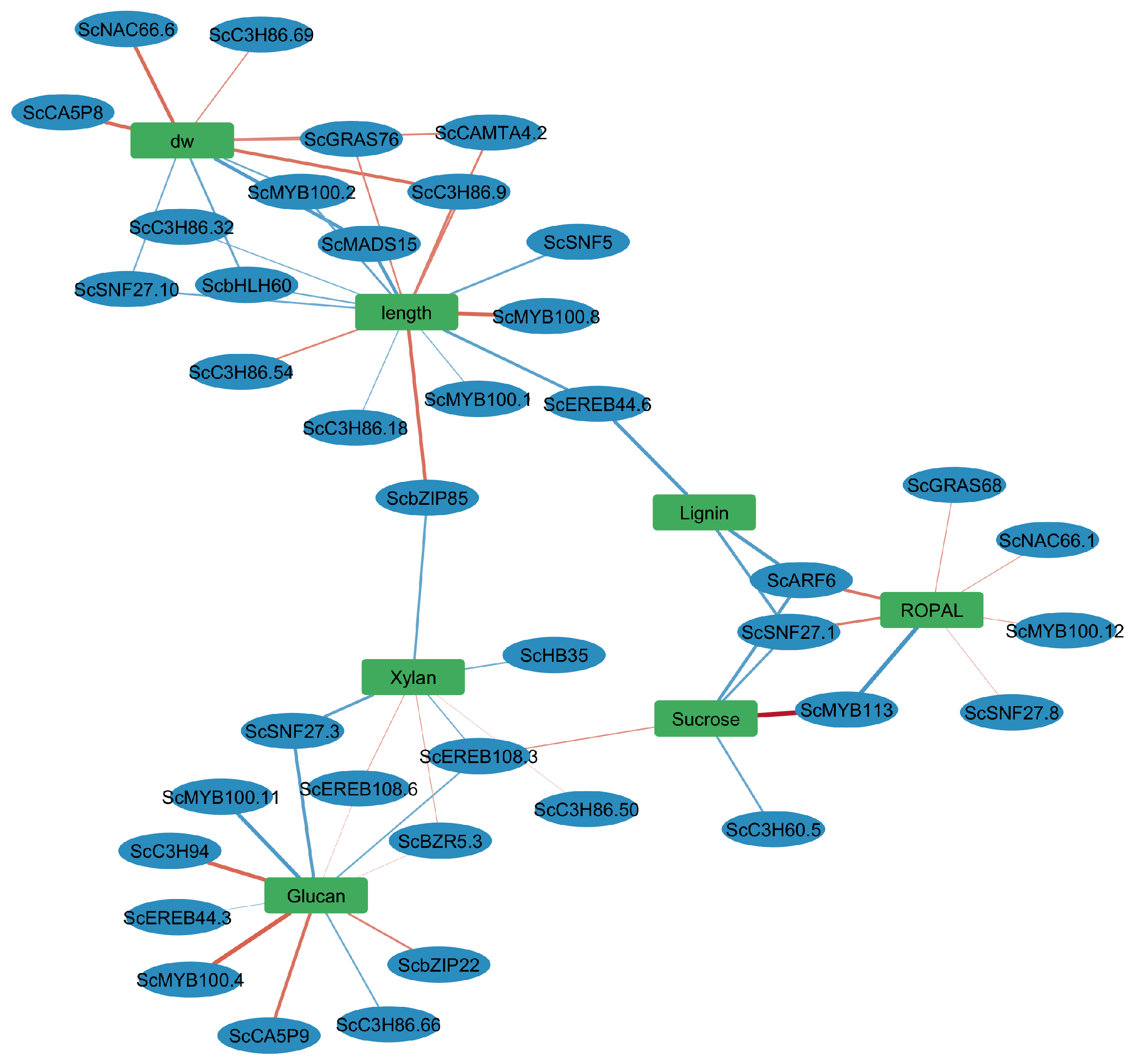

3.6. Gene-Trait Association Network Reveals Modular and Coordinated Regulation of Biomass-Related Traits

3.6.1. A Biomass Cluster: Dry Weight and Elongation

3.6.2. Cell Wall Polysaccharide Cluster: Glucan and Xylan

3.6.3. Intermediary Metabolism (ROPAL), Sucrose, and Lignin

4. Conclusions

References

- Duca, D.; Toscano, G. Biomass Energy Resources: Feedstock Quality and Bioenergy Sustainability. 11, 57.

- Peláez-Samaniego, M.R.; Garcia-Perez, M.; family=Cortez, given=LB, g.i.; Rosillo-Calle, F.; Mesa, J. Improvements of Brazilian Carbonization Industry as Part of the Creation of a Global Biomass Economy. 12, 1063–1086.

- Oh, Y.K.; Hwang, K.R.; Kim, C.; Kim, J.R.; Lee, J.S. Recent Developments and Key Barriers to Advanced Biofuels: A Short Review. 257, 320–333.

- Nations, U. Transforming Our World: The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development. 1, 41.

- European Commission. The European Green Deal. COM (2019) 640 Final. 11, 2019.

- Muscat, A.; Olde, E.M.; Ripoll-Bosch, R.; Van Zanten, H.H.E.; Metze, T.A.P.; Termeer, C.J.A.M.; Ittersum, M.; Boer, I.J.M. Principles, Drivers and Opportunities of a Circular Bioeconomy. 2, 561–566. [CrossRef]

- Kebrom, T.H.; McKinley, B.; Mullet, J.E. Dynamics of Gene Expression during Development and Expansion of Vegetative Stem Internodes of Bioenergy Sorghum. 10, 159. [CrossRef]

- Lingle, S.E. Seasonal Internode Development and Sugar Metabolism in Sugarcane. 37, 1222–1227.

- Martin, A.; Palmer, W.; Brown, C.; Abel, C.; Lunn, J.; Furbank, R.; Grof, C.P.L. A Developing Setaria Viridis Internode: An Experimental System for the Study of Biomass Generation in a C4 Model Species. 9, 45. [CrossRef]

- Botha, F.C.; Scalia, G.; Marquardt, A.; Wathen-Dunn, K. Sink Strength During Sugarcane Culm Growth: Size Matters. [CrossRef]

- Yanagui, K.; Camargo, E.L.; family=Abreu, given=Luís Guilherme F, p.u.; Nagamatsu, S.T.; Fiamenghi, M.B.; Silva, N.V.; Carazzolle, M.F.; Nascimento, L.C.; Franco, S.F.; Bressiani, J.A. Internode Elongation in Energy Cane Shows Remarkable Clues on Lignocellulosic Biomass Biosynthesis in Saccharum Hybrids. 828, 146476.

- Chen, R.; Fan, Y.; Yan, H.; Zhou, H.; et.al.. Enhanced Activity of Genes Associated With Photosynthesis, Phytohormone Metabolism and Cell Wall Synthesis Is Involved in Gibberellin-Mediated Sugarcane Internode Growth. 11, 570094, [33193665]. [CrossRef]

- Mason, P.J.; Hoang, N.V.; Botha, F.C.; Furtado, A.; Marquardt, A.; Henry, R.J. Comparison of the Root, Leaf and Internode Transcriptomes in Sugarcane (Saccharum Spp. Hybrids). 4, 167–178.

- Wang, M.; Li, A.M.; Liao, F.; Qin, C.X.; Chen, Z.L.; Zhou, L.; Li, Y.R.; Li, X.F.; Lakshmanan, P.; Huang, D.L. Control of Sucrose Accumulation in Sugarcane (Saccharum Spp. Hybrids) Involves miRNA-mediated Regulation of Genes and Transcription Factors Associated with Sugar Metabolism. 14, 173–191. [CrossRef]

- Ferreira, S.S.; Hotta, C.T.; Poelking, V.G.d.C.; Leite, D.C.C.; Buckeridge, M.S.; Loureiro, M.E.; Barbosa, M.H.P.; Carneiro, M.S.; Souza, G.M. Co-Expression Network Analysis Reveals Transcription Factors Associated to Cell Wall Biosynthesis in Sugarcane. 91, 15–35.

- Vélez-Bermúdez, I.C.; Schmidt, W. The Conundrum of Discordant Protein and mRNA Expression. Are Plants Special? 5, 619.

- Broun, P. Transcription Factors as Tools for Metabolic Engineering in Plants. 7, 202–209.

- Grotewold, E. Transcription Factors for Predictive Plant Metabolic Engineering: Are We There Yet? 19, 138–144.

- Braun, E.L.; Dias, A.P.; Matulnik, T.J.; Grotewold, E. Chapter Five Transcription Factors and Metabolic Engineering: Novel Applications for Ancient Tools. In Recent Advances in Phytochemistry; Romeo, J.T.; Saunders, J.A.; Mattews, B.F., Eds.; Elsevier; Vol. 35, pp. 79–109. [CrossRef]

- Capell, T.; Christou, P. Progress in Plant Metabolic Engineering. 15, 148–154.

- Reverter, A.; Hudson, N.J.; Nagaraj, S.H.; Pérez-Enciso, M.; Dalrymple, B.P. Regulatory Impact Factors: Unraveling the Transcriptional Regulation of Complex Traits from Expression Data. 26, 896–904.

- Hudson, N.J.; Reverter, A.; Dalrymple, B.P. Beyond Differential Expression: The Quest for Causal Mutations and Effector Molecules. 10, 83. https://doi.org/10.1186/1471-2164-10-83. [CrossRef]

- Botha, F.C.; Marquardt, A. Metabolic Control of Sugarcane Internode Elongation and Sucrose Accumulation. 14, 1487.

- Berding, N.; Marston, D.H. Operational Validation of the Efficacy of Spectracane, a High-Speed Analytical System for Sugarcane Quality Components. pp. 445–459.

- Pisanó, I.; Gottumukkala, L.; Hayes, D.J.; Leahy, J.J. Characterisation of Italian and Dutch Forestry and Agricultural Residues for the Applicability in the Bio-Based Sector. 171, 113857. [CrossRef]

- Sluiter, A.; Hames, B.; Ruiz, R.; Scarlata, C.; Sluiter, J.; Templeton, D.; family=Crocker, given=DLAP, g.i. Determination of Structural Carbohydrates and Lignin in Biomass. 1617, 1–16.

- Hayes, D.J. Development of near Infrared Spectroscopy Models for the Quantitative Prediction of the Lignocellulosic Components of Wet Miscanthus Samples. 119, 393–405.

- Bhagia, S.; Nunez, A.; Wyman, C.E.; Kumar, R. Robustness of Two-Step Acid Hydrolysis Procedure for Composition Analysis of Poplar. 216, 1077–1082.

- Yang, S.; Logan, J.; Coffey, D. Mathematical Formulae for Calculating the Base Temperature for Growing Degree Days. 74, 61–74.

- Marquardt, A.; Henry, R.J.; Botha, F.C. Effect of Sugar Feedback Regulation on Major Genes and Proteins of Photosynthesis in Sugarcane Leaves. 158, 321–333.

- Love, M.I.; Huber, W.; Anders, S. Moderated Estimation of Fold Change and Dispersion for RNA-seq Data with DESeq2. 15, 1–21.

- Robinson, M.D.; Oshlack, A. A Scaling Normalization Method for Differential Expression Analysis of RNA-seq Data. 11, 1–9.

- Subramanian, A.; Tamayo, P.; Mootha, V.K.; Mukherjee, S.; Ebert, B.L.; Gillette, M.A.; Paulovich, A.; Pomeroy, S.L.; Golub, T.R.; Lander, E.S. Gene Set Enrichment Analysis: A Knowledge-Based Approach for Interpreting Genome-Wide Expression Profiles. 102, 15545–15550.

- Ruxton, G.D. The Unequal Variance T-Test Is an Underused Alternative to Student’s t-Test and the Mann–Whitney U Test. 17, 688–690.

- Benjamini, Y.; Hochberg, Y. On the Adaptive Control of the False Discovery Rate in Multiple Testing with Independent Statistics. 25, 60–83.

- Lingle, S.E.; Thomson, J.L. Sugarcane Internode Composition During Crop Development. 5, 168–178. [CrossRef]

- De Souza, A.P.; Leite, D.C.; Pattathil, S.; Hahn, M.G.; Buckeridge, M.S. Composition and Structure of Sugarcane Cell Wall Polysaccharides: Implications for Second-Generation Bioethanol Production. 6, 564–579.

- Chen, L.; Dou, P.; Li, L.; Chen, Y.; Yang, H. Transcriptome-Wide Analysis Reveals Core Transcriptional Regulators Associated with Culm Development and Variation in Dendrocalamus Sinicus, the Strongest Woody Bamboo in the World. 8.

- Zhong, R.; Richardson, E.A.; Ye, Z.H. The MYB46 Transcription Factor Is a Direct Target of SND1 and Regulates Secondary Wall Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. 19, 2776–2792.

- Xie, L.; Wen, D.; Wu, C.; Zhang, C. Transcriptome Analysis Reveals the Mechanism of Internode Development Affecting Maize Stalk Strength. 22, 49.

- Becker, A.; Theißen, G. The Major Clades of MADS-box Genes and Their Role in the Development and Evolution of Flowering Plants. 29, 464–489. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Ye, D.; Xing, J.; Duan, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, M. Ethephon-Regulated Maize Internode Elongation Associated with Modulating Auxin and Gibberellin Signal to Alter Cell Wall Biosynthesis and Modification. 290, 110196.

- Ohme-Takagi, M.; Shinshi, H. Ethylene-Inducible DNA Binding Proteins That Interact with an Ethylene-Responsive Element. 7, 173–182. [CrossRef]

| Trait | Phenotype1 | Young2 | Mature3 | |||||||

| mean | p-adj | Tukey4 | mean | p-adj | Tukey4 | mean | p-adj | Tukey4 | ||

| length mm internode−1 |

-50.81 | <0.001 | ** | 58.1 | <0.001 | ** | -1.28 | 1 | ns | |

| Dry weight g internode−1 |

-11.2 | <0.001 | ** | 7.58 | <0.001 | ** | 4.02 | 0.03 | ** | |

| Water soluble | mg | |||||||||

| Total sugar | 31.59 | 0.1789 | ns | 182.46 | <0.001 | ** | -40.68 | 0.192 | ns | |

| Sucrose | 40.49 | 0.2794 | ns | 241.43 | <0.001 | ** | 31.01 | 0.6912 | ns | |

| Cellobiose | -0.02 | 0.9413 | ns | 2.86 | <0.001 | ** | -1.72 | <0.001 | ** | |

| Glucose | -4.68 | 0.5813 | ns | -32.07 | <0.001 | ** | -38.3 | <0.001 | ** | |

| Fructose | -4.03 | 0.5764 | ns | -28.49 | <0.001 | ** | -31.89 | <0.001 | ** | |

| Galactose | -0.14 | 0.3249 | ns | -1.15 | <0.001 | ** | 0.23 | 0.7982 | ns | |

| Arabinose | -0.02 | 0.2764 | ns | -0.13 | <0.001 | ** | -0.01 | 0.9997 | ns | |

| Cell wall | mg | |||||||||

| Total sugar | -23.28 | 0.0737 | ns | -83.81 | <0.001 | ** | -56.64 | <0.001 | ** | |

| Hexosans | -17.02 | 0.0764 | ns | -61.57 | <0.001 | ** | -45.28 | <0.001 | ** | |

| Glucan | -16.76 | 0.0759 | ns | -60.17 | <0.001 | ** | -45.42 | <0.001 | ** | |

| Mannan | -0.1 | 0.1828 | ns | -0.43 | 0.0012 | ** | 0.06 | 0.9992 | ns | |

| Galactan | -0.17 | 0.3208 | ns | -0.97 | 0.0046 | ** | 0.07 | 1 | ns | |

| Pentosans | -6.36 | 0.0739 | ns | -21.09 | <0.001 | ** | -9.64 | 0.0556 | ns | |

| Xylan | -5.28 | 0.0952 | ns | -18.54 | <0.001 | ** | -9.85 | 0.0712 | ns | |

| Arabinan | -0.96 | 0.0792 | ns | -3.51 | <0.001 | ** | -1.6 | 0.1171 | ns | |

| Rhamnan | -0.02 | 0.5405 | ns | -0.19 | 0.0011 | ** | 0.09 | 0.5463 | ns | |

| Glucoronic-acid | 0.31 | 0.4683 | ns | 1.29 | 0.5724 | ns | 1.05 | 0.7981 | ns | |

| Hemicellulose5 | -6.25 | 0.0856 | ns | -22.24 | <0.001 | ** | -11.36 | 0.0311 | ** | |

| mg | ||||||||||

| Lignin | Klason lignin | 2.85 | 0.6771 | ns | 21.86 | <0.001 | ** | 43.48 | <0.001 | ** |

| AS lignin | -0.36 | 0.4546 | ns | -3.39 | <0.001 | ** | 2.7 | 0.001 | ** | |

| mg | ||||||||||

| Other | ROPAL6 | -22.7 | 0.4576 | ns | -170.9 | <0.001 | ** | -6.29 | 1 | ns |

| Trait | Positive correlation | Negative correlation | ||||

| TF 1 | Correlation | p-value | TF 1 | Correlation 1 | p-value | |

| length | ScMYB100 | 0.774 | 9.07E-06 | ScC3H86 | -0.581 | 2.92E-03 |

| ScbZIP85 | 0.747 | 2.76E-05 | ScbHLH60 | -0.618 | 1.29E-03 | |

| ScC3H86 | 0.683 | 2.34E-04 | ScSNF27 | -0.636 | 8.30E-04 | |

| ScCAMTA4 | 0.653 | 5.45E-04 | ScSNF5 | -0.663 | 4.12E-04 | |

| ScGRAS76 | 0.629 | 9.84E-04 | ScMADS15 | -0.738 | 3.79E-05 | |

| ScEREB44 | -0.710 | 1.01E-04 | ||||

| Dry weight | ScC3H86 | 0.596 | 2.11E-03 | ScMADS15 | -0.750 | 2.41E-05 |

| ScGRAS76 | 0.624 | 1.11E-03 | ScbHLH60 | -0.661 | 4.43E-04 | |

| ScCAMTA4 | 0.637 | 8.12E-04 | ScMYB100 | -0.632 | 9.15E-04 | |

| ScC3H86 | 0.732 | 4.72E-05 | ScSNF27 | -0.620 | 1.24E-03 | |

| ScCA5P8 | 0.755 | 1.99E-05 | ||||

| ScNAC66 | 0.759 | 1.70E-05 | ||||

| Glucan | ScMYB100 | 0.811 | 1.52E-06 | ScEREB44 | -0.548 | 5.57E-03 |

| ScC3H94 | 0.778 | 7.71E-06 | ScEREB108 | -0.625 | 1.10E-03 | |

| ScCA5P9 | 0.736 | 4.09E-05 | ScC3H86 | -0.631 | 9.39E-04 | |

| ScbZIP22 | 0.644 | 6.88E-04 | ScSNF27 | -0.731 | 4.93E-05 | |

| ScEREB108 | 0.530 | 7.78E-03 | ||||

| ScBZR5 | 0.527 | 8.11E-03 | ||||

| Xylan | ScEREB108 | 0.556 | 4.76E-03 | ScSNF27 | -0.700 | 1.40E-04 |

| ScBZR5 | 0.555 | 4.87E-03 | ScbZIP85 | -0.679 | 2.66E-04 | |

| ScC3H86 | 0.526 | 8.33E-03 | ScHB35 | -0.613 | 1.44E-03 | |

| Sucrose | ScMYB113 | 0.824 | 7.58E-07 | ScC3H60 | -0.661 | 4.35E-04 |

| ScEREB108 | 0.593 | 2.25E-03 | ScSNF27 | -0.681 | 2.49E-04 | |

| ScARF6 | -0.733 | 4.61E-05 | ||||

| Lignin | ScEREB44 | -0.755 | 1.99E-05 | |||

| ScARF6 | -0.753 | 2.17E-05 | ||||

| ScSNF27 | -0.718 | 7.83E-05 | ||||

| ROPAL | ScARF6 | 0.712 | 9.57E-05 | ScMYB113 | -0.805 | 2.10E-06 |

| ScSNF27 | 0.679 | 2.68E-04 | ||||

| ScGRAS68 | 0.570 | 3.64E-03 | ||||

| ScNAC66 | 0.562 | 4.29E-03 | ||||

| ScSNF27 | 0.539 | 6.62E-03 | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).