1. Introduction

Breast cancer is an escalating public health concern globally, but its incidence in Bangladesh indicates unique challenges associated with the country’s socio-economic, healthcare, and cultural landscape[

1,

2,

3]. This increase in breast cancer cases, while aligned with global trends, poses significant burdens on its resource-limited healthcare infrastructure. Notably, breast cancer cases in Bangladesh are frequently present in the advanced stages[

4]. Limited screening programs and delayed healthcare-seeking behavior contribute to poorer survival rates and higher mortality compared to more developed countries, further compounding national healthcare challenges[

5].

While reproductive factors—such as age at menarche, age at first childbirth, parity, and contraceptive use—are well-established contributors to breast cancer risk, much of the research linking these factors to specific breast cancer subtypes has been conducted in high-income countries[

6,

7]. These studies often fail to account for the distinct reproductive practices and behaviors observed in low- and middle-income settings, such as early marriage, early motherhood, and limited contraceptive use. In Bangladesh, these unique reproductive patterns are shaped by cultural norms and economic factors that potentially influence the etiology of breast cancer.

Specifically, the distribution of hormone receptor-positive (HR+) and triple-negative breast cancer (TNBC) subtypes differs between populations[

8]. HR+ breast cancers, which are driven by hormonal factors and often have better prognoses, tend to be more common in high-income settings where delayed childbearing and widespread contraceptive use are prevalent[

9,

10,

11,

12]. In contrast, TNBC, characterized by its aggressive nature, lack of targeted hormonal therapies, and poor survival outcomes, is more frequently observed in younger women and populations with distinct reproductive behaviors, such as those found in Bangladesh[

13,

14,

15,

16]. However, the interplay between these reproductive factors and breast cancer subtype prevalence remains underexplored in Bangladesh.

This gap in the literature highlights the critical need to examine the contributions of reproductive and demographic factors to breast cancer risk in Bangladesh, with a focus on HR+ and TNBC subtypes. Despite their distinct clinical implications, little is known about the correlation between these subtypes and reproductive history within low-resource settings. Such insights could significantly advance our understanding of breast cancer etiology in Bangladesh, enabling more tailored prevention strategies and subtype-specific interventions.

This study addresses the critical need for localized data by investigating the relationships among reproductive factors, demographic variables, and breast cancer subtypes among Bangladeshi women. Utilizing advanced machine learning (ML) approaches—including XGBoost, Random Forest, Support Vector Machine, Logistic Regression with Lasso Regularization, and standard Logistic Regression—paired with Shapley-based interpretability techniques, this research aims to uncover key predictors for HR+ and TNBC[

17]. By contextualizing these findings within the unique reproductive and socio-demographic landscape of Bangladesh, this study provides a nuanced understanding of the factors influencing breast cancer risk as evidenced by a tertiary cancer hospital. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first investigation of its kind targeting Bangladeshi women. The results hold significant potential to fill existing knowledge gaps, guide evidence-based public health policies, and improve clinical strategies, thereby contributing to global efforts to reduce disparities in breast cancer prevention and outcome.

2. Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This case-control study was conducted at the National Institute of Cancer Research and Hospital (NICRH), a public tertiary care hospital in Dhaka, Bangladesh. NICRH is one of the largest referral centers in the country and provides multidisciplinary cancer care. Data were collected between January 2021 and December 2021.

2.2. Study Population

The study included 929 Bangladeshi women aged 18 to 75 years, comprising 486 cases and 443 age-matched controls. Patients with histopathologically confirmed breast cancer patients were treated at the NICRH during the study period. Controls were cancer-free women selected from among hospital visitors accompanying patients in other departments. Controls were matched with cases by age within a ±5-year range and district of residence to account for regional disparities in healthcare access.

2.3. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

Cases: Women with confirmed histopathological diagnoses of breast cancer. The exclusion criteria included a history of other malignancies or incomplete medical records.

Controls: Women without a history of cancer. The exclusion criteria were malignancies or reproductive health conditions that could confound the analysis.

2.4. Data Collection

Data were collected through structured interviews and medical records. A team of six trained physicians conducted face-to-face interviews following standardized protocols to minimize bias. For participants with no literacy, the consent form was read aloud in the presence of a family member. To ensure high data quality, the data collectors received comprehensive training on the study protocols and collection techniques. Instruments were pretested on a similar population to address potential issues prior to formal data collection. Field supervisors conducted periodic quality checks for completeness and accuracy, resolving discrepancies or missing data through follow-up with the collection team.

3. Variables Assessed

3.1. Primary Outcome Variable

The primary outcome variable was the breast cancer diagnosis, which was confirmed by histopathology. Patients were classified into three groups: "No Cancer," " TNBC," and "HR+" to reflect the two major breast cancer subtypes examined in this study.

3.2. Independent Variables

Socio-Demographic Factors: Age, education level (0–5 years, 6–12 years, 13–20 years), residential area (rural, urban, metropolitan), and employment status (unemployed, employed).

Reproductive Factors: Age at menarche, age at first marriage, age at first childbirth, gaps between menarche and first childbirth, and first marriage and first childbirth; parity (categorized as 0, 1, or >1 child), type of delivery (vaginal, cesarean, or both), menstrual regularity (regular or irregular), menopausal status (premenopausal or postmenopausal) and abortion history (categorized as no abortion, 1, or ≥2 abortions).

Anthropometric Measures: Body mass index (BMI) was calculated using height and weight measurements and categorized as underweight (<18.5 kg/m²), normal (18.5–24.9 kg/m²), and obese (≥25 kg/m²) based on WHO guidelines.

3.3. Experimental Design

A machine learning-based predictive analysis was conducted to identify the features most associated with breast cancer subtypes, including TNBC and HR+ cases. The experimental design included comprehensive preprocessing, the application of diverse machine learning models, and rigorous evaluation using stratified cross-validation and performance comparison metrics. Shapley values were employed for model explainability to highlight the key predictors of breast cancer subtypes in Bangladeshi women.

3.4. Data Preprocessing and Model Training

Numeric variables, including age, age at first marriage, age at first childbirth, age at menarche, gaps between menarche and first childbirth, and first marriage and first childbirth were normalized using min-max scaling to standardize their range. Additionally, socio-demographic and reproductive variables, such as residential area, employment status, parity, delivery type, menstrual status, and nutrition, were one-hot encoded to facilitate machine learning analysis. The target variable (type) was categorized into three levels: "No Cancer," "HR+," and "TNBC."

For model training and evaluation, the dataset was divided into 80% training and 20% testing subsets using stratified sampling to maintain the class balance across the subcategories. Stratified 5-fold cross-validation was employed during training to ensure robust evaluation and mitigate overfitting, while preserving class proportions within each fold. This approach ensured that the models are trained using representative and balanced data.

Five machine learning models were trained and evaluated to ensure a comprehensive analysis. Logistic Regression was used as a baseline model, whereas Logistic Regression with Lasso Regularization added feature selection by penalizing less important predictors. Support Vector Machines (SVM) with a radial kernel handled non-linear relationships in the data, Random Forest built an ensemble of decision trees for robust predictions, and XGBoost, leveraging gradient boosting, was employed. The performance of each model was evaluated using metrics derived from confusion matrices, including the sensitivity, specificity, precision, recall, F1-score, and balanced accuracy. Additionally, the multiclass Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) Curve (AUC) was calculated to assess the predictive power of the model for each breast cancer subtype.

3.5. Explainability of ML Models

Shapley values were employed to explain the contribution of each feature to the model predictions, to ensure the interpretability of the machine learning models used in predicting breast cancer subtypes. Shapley values, derived from cooperative game theory, quantify the impact of individual features on the model's output. This allowed us to systematically evaluate the relative importance of socio-demographic and reproductive factors in distinguishing between HR+ and TNBC cases.

Three specific approaches were utilized to analyze and visualize the results using Shapley values:

Global Feature Importance with Confidence Intervals: Shapley values were averaged across all data points to compute the global feature importance for each subtype for a comprehensive view of how individual features contributed to the subtypes of cancer in our dataset. These averages, along with 95% confidence intervals, were plotted to identify the features that significantly influenced the prediction of HR+ and TNBC cases. Values below zero indicate a negative contribution to the prediction, whereas values above zero signify a positive contribution. Significance testing was conducted using the Wilcoxon signed-rank test, and features with a significance greater than zero (p-value < 0.05) for each subtype were highlighted.

Comparative Analysis of Feature Importance: To further evaluate the relative contributions of features, we conducted pairwise comparisons of Shapley values for HR+ and TNBC cases. Features were grouped into three categories based on their importance: those with higher predictive relevance for TNBC (μ_TN > μ_HR+), those with higher predictive relevance for HR+ (μ_TN < μ_HR+), and those with equal predictive relevance for both subtypes (μ_TN = μ_HR+).

Visualization of Trends in Numeric Features: Shapley values for numeric features were plotted against their feature values to capture trends and patterns of predictive importance. For each numeric feature, scatterplots were created, with individual Shapley values represented as points and smoothed trend lines indicating the average impact of the feature values on the predictions.

The goal of these Shapley-based analysis was to provide interpretable insights and enable a clear understanding of the influence of socio-demographic and reproductive factors on the prediction of breast cancer subtypes.

3.6. Ethical Considerations

The study protocol was approved by the National Institute for Cancer Research and Hospital Ethics Committee (Ref: NICRH/Ethics/2021/89). Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants. Data confidentiality and anonymity were strictly maintained, and all data were stored securely in a password-protected database.

4. Results

Table 1.

Distribution of socio-demographic and reproductive characteristics across breast cancer subtypes (No Cancer, HR+, and TNBC) in the study population. The categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages n (%), while continuous variables are shown as mean (standard deviation). P-values correspond to chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables, assessing differences across the three subtypes.

Table 1.

Distribution of socio-demographic and reproductive characteristics across breast cancer subtypes (No Cancer, HR+, and TNBC) in the study population. The categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages n (%), while continuous variables are shown as mean (standard deviation). P-values correspond to chi-square tests for categorical variables and ANOVA for continuous variables, assessing differences across the three subtypes.

| |

Breast Cancer Subtypes |

|

| Features |

No Cancer |

HR+ |

TNBC |

P-value |

| Breast Cancer Subtype |

443 (100%) |

246 (100%) |

240 (100%) |

|

| Residential Area (n (%)) |

|

|

|

|

| Rural |

98 (22.12%) |

188 (76.42%) |

146 (60.83%) |

0.000 |

| Urban |

107 (24.15%) |

48 (19.51%) |

80 (33.33%) |

0.000 |

| Metropolitan |

238 (53.72%) |

10 (4.07%) |

14 (5.83%) |

0.000 |

| Employment Status |

|

|

|

|

| Unemployed |

351 (79.23%) |

241 (97.97%) |

224 (93.33%) |

0.000 |

| Employed |

92 (20.77%) |

5 (2.03%) |

16 (6.67%) |

0.000 |

| Education Level |

|

|

|

|

| 0-5 Years |

89 (20.09%) |

198 (80.49%) |

190 (79.17%) |

0.000 |

| 6-12 Years |

243 (54.85%) |

37 (15.04%) |

37 (15.42%) |

0.000 |

| 13-20 Years |

111 (25.06%) |

11 (4.47%) |

13 (5.42%) |

0.000 |

| Parity |

|

|

|

|

| <=1 |

254 (57.34%) |

131 (53.25%) |

119 (49.58%) |

0.142 |

| > 1 |

189 (42.66%) |

115 (46.75%) |

121 (50.42%) |

0.142 |

| Type of Delivery |

|

|

|

|

| Normal Vaginal Delivery (NVD) |

258 (58.24%) |

188 (76.42%) |

163 (67.92%) |

0.000 |

| Cesarean Section (CS) |

144 (32.51%) |

31 (12.6%) |

25 (10.42%) |

0.000 |

| Both Type (CS+NVD) |

41 (9.26%) |

27 (10.98%) |

52 (21.67%) |

0.000 |

| Type of Menstruation |

|

|

|

|

| Regular |

369 (83.3%) |

171 (69.51%) |

161 (67.08%) |

0.000 |

| Irregular |

74 (16.7%) |

75 (30.49%) |

79 (32.92%) |

0.000 |

| Menstrual Status |

|

|

|

|

| Premenopausal |

276 (62.3%) |

130 (52.85%) |

98 (40.83%) |

0.000 |

| Postmenopausal |

167 (37.7%) |

116 (47.15%) |

142 (59.17%) |

0.000 |

| Abortion |

|

|

|

|

| No |

339 (76.52%) |

148 (60.16%) |

177 (73.75%) |

0.000 |

| Yes = 1 |

89 (20.09%) |

84 (34.15%) |

41 (17.08%) |

0.000 |

| Yes > = 2 |

15 (3.39%) |

14 (5.69%) |

22 (9.17%) |

0.000 |

| Body Mass Index (BMI) |

|

|

|

|

| Healthy |

138 (31.15%) |

107 (43.5%) |

98 (40.83%) |

0.000 |

| Obese |

298 (67.27%) |

127 (51.63%) |

127 (52.92%) |

0.000 |

| Undernutrition |

7 (1.58%) |

12 (4.88%) |

15 (6.25%) |

0.000 |

| Age (Mean (SD)) |

41.05 (11.4) |

43.00 (10.4) |

45.04 (10.2) |

0.000 |

| Age at First Marriage |

17.73 (3.54) |

17.46 (3.00) |

18.55 (3.19) |

0.001 |

| Age at First Baby |

19.80 (3.82) |

19.57 (3.29) |

20.91 (3.65) |

0.000 |

| Age at Menarche |

12.64 (1.09) |

12.05 (1.21) |

13.03 (0.37) |

0.000 |

| Gap Between Menarche and First Baby |

7.17 (3.84) |

7.52 (3.26) |

7.88 (3.59) |

0.048 |

| Gap Between First Marriage and First Baby |

2.07 (1.71) |

2.11 (1.42) |

2.36(1.78) |

0.082 |

4.1. Study Population Characteristics

The cohort consisted of 443 women without any breast cancer diagnosis, 246 HR+ cases, and 240 TNBC cases. The majority of HR+ and TNBC patients resided in rural areas (76.4% and 60.8%, respectively), whereas a larger proportion of cancer-free individuals lived in metropolitan regions (53.7%). Employment status, education level, and reproductive factors showed significant variation across subtypes, with higher employment among the cancer-free group (20.8%) compared to the HR+ (2.0%) and TNBC (6.7%) groups.

Women with HR+ and TNBC subtypes had lower educational attainment (80.5% and 79.2% had ≤5 years of education, respectively) compared to the cancer-free group (20.1%). Reproductive factors also varied significantly, with patients with TNBC having the highest rate of multiple abortions (9.2% with ≥2 abortions) and a higher proportion of postmenopausal women (59.2%). Menstrual irregularities were more common among HR+ (30.5%) and TNBC (32.9%) patients than in cancer-free women (16.7%).

Regarding age-related factors, TNBC cases had the highest mean age (45.0 ± 10.2 years), followed by HR+ (43.0 ± 10.4) and cancer-free individuals (41.0 ± 11.4) (p < 0.001). Similarly, the age at menarche was significantly higher in TNBC patients (13.03 years) than in HR+ (12.05 years) and cancer-free individuals (12.64 years) (p < 0.001). The gaps between reproductive milestones, such as menarche to first childbirth and first marriage to first childbirth, were longer in patients with TNBC (p = 0.048 and p = 0.082, respectively), indicating distinct reproductive patterns.

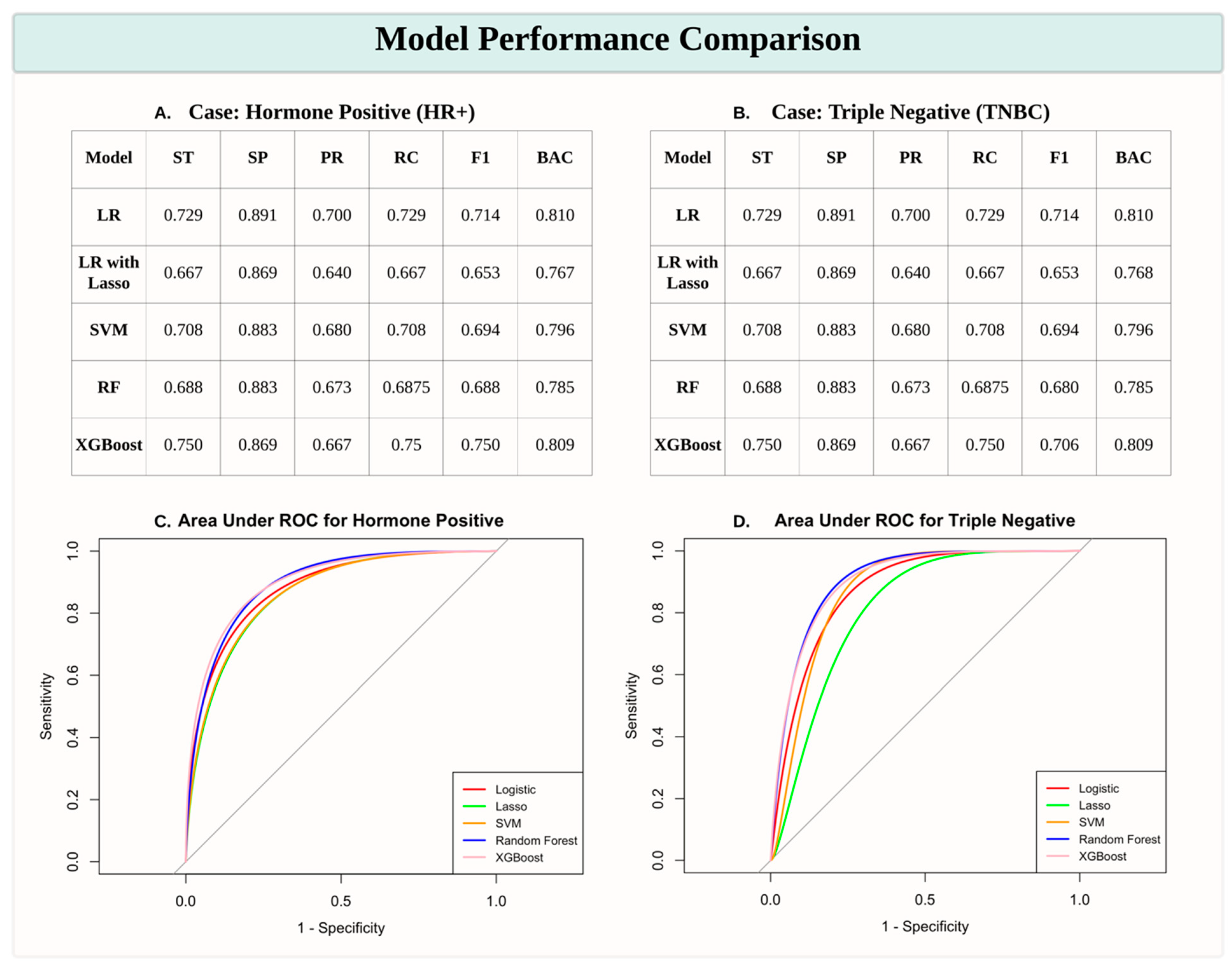

4.2. Model Comparison

The performance of various machine learning models in predicting the HR+ and TNBC subtypes was assessed using sensitivity (ST), specificity (SP), precision (PR), recall (RC), F1 score (F1), and balanced accuracy (BAC). Among the models, XGBoost consistently demonstrated superior performance, achieving the highest sensitivity (0.750 for both HR+ and TNBC cases) and F1 scores (0.750 and 0.706 for HR+ and TNBC, respectively), indicating its robustness in handling data complexity. Logistic Regression (LR) also performed well, with comparable balanced accuracy (0.810 for both subtypes), while Logistic Regression with Lasso Regularization (LR with Lasso) showed relatively lower scores across most metrics. The Support Vector Machine (SVM) and Random Forest (RF) models achieved moderate performance, with balanced accuracy ranging from 0.785 to 0.796. ROC curves further validated the effectiveness of these models, with XGBoost exhibiting the highest area under the curve (AUC) values, particularly for HR+ predictions. These results highlight that XGBoost is the most effective model for distinguishing breast cancer subtypes in this study.

Figure 1.

Model Performance Comparison for Predicting Breast Cancer Subtypes. (A, B) Tables presenting performance metrics for predicting HR+ and TNBC subtypes across various machine learning models, including Logistic Regression (LR), Logistic Regression with Lasso Regularization (LR with Lasso), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and XGBoost. Metrics include Sensitivity (ST), Specificity (SP), Precision (PR), Recall (RC), F1 Score (F1), and Balanced Accuracy (BAC). (C, D) Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves with Area Under the Curve (AUC) scores for HR+ (C) and TNBC (D) predictions, illustrating model performance in distinguishing breast cancer subtypes. XGBoost consistently demonstrates robust performance, particularly for HR+ cases.

Figure 1.

Model Performance Comparison for Predicting Breast Cancer Subtypes. (A, B) Tables presenting performance metrics for predicting HR+ and TNBC subtypes across various machine learning models, including Logistic Regression (LR), Logistic Regression with Lasso Regularization (LR with Lasso), Support Vector Machine (SVM), Random Forest (RF), and XGBoost. Metrics include Sensitivity (ST), Specificity (SP), Precision (PR), Recall (RC), F1 Score (F1), and Balanced Accuracy (BAC). (C, D) Receiver Operating Characteristic (ROC) curves with Area Under the Curve (AUC) scores for HR+ (C) and TNBC (D) predictions, illustrating model performance in distinguishing breast cancer subtypes. XGBoost consistently demonstrates robust performance, particularly for HR+ cases.

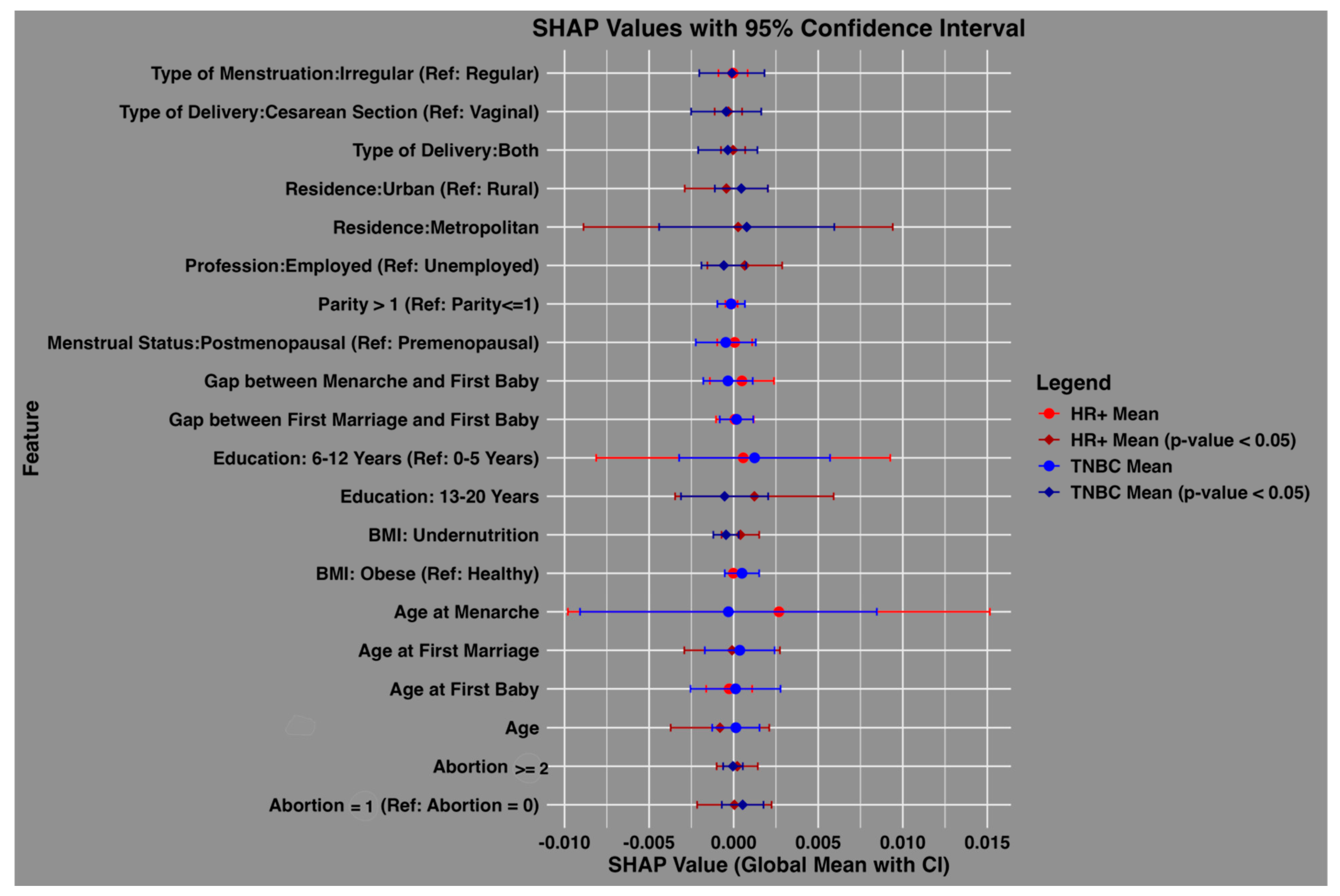

4.3. Feature Importance and Comparative Analysis

Figure 2 compares the feature importance for HR+ and TNBC cases among Bangladeshi women. The global mean SHAP values, with 95% confidence intervals, highlight features that influence subtype predictions. Significant predictors (p-values < 0.05) for both subtypes included the type of delivery (both vaginal and cesarean), residence, employment status, education level (13–20 years), BMI (undernutrition), and abortion history. Age at first marriage and age emerged as uniquely significant predictors of HR+ cases, reflecting subtype-specific demographic and reproductive patterns.

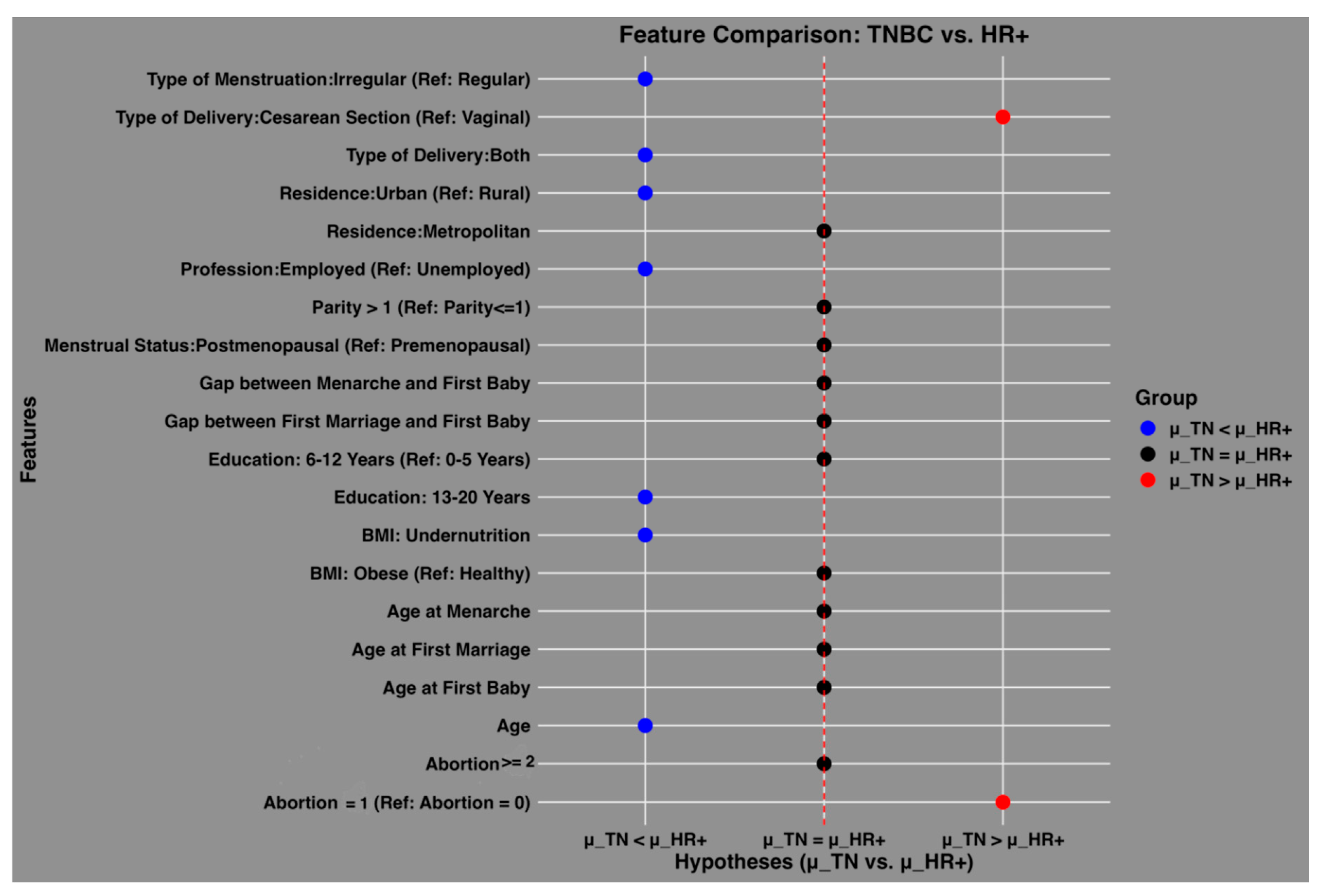

Figure 3 illustrates the relative contributions of socio-demographic and reproductive features in predicting TNBC and HR+ cases among Bangladeshi women. The x-axis represents the three tested hypotheses using Wilcoxon paired comparisons: μ_TN > μ_HR+ (greater importance for TNBC), μ_TN = μ_HR+ (equal importance), and μ_TN < μ_HR+ (greater importance for HR+). The y-axis lists the features, and their positions indicate their relative contribution. Blue dots represent features with greater importance for TNBC prediction, whereas red dots indicate features more relevant for HR+ cases. Black dots signify features with no significant difference in contribution between subtypes.

Key findings include a greater mean importance for HR+ cases for features such as irregular type of menstruation, both vaginal and cesarean delivery types, urban residence, employment status, higher education levels (13–20 years), undernutrition (low BMI), and age. Conversely, cesarean delivery and a history of two or more abortions were significantly more important predictors of TNBC. Features represented by black dots, such as other types of menstruation and reproductive factors, showed equal relevance across both subtypes. This analysis highlights the distinct and shared predictive patterns for the two subtypes of breast cancer.

Figure 3.

Relative contributions of features to the prediction of triple-negative (TN) and HR+ breast cancer cases among Bangladeshi women. The x-axis represents the three tested hypotheses using Wilcoxon paired comparisons: μ_TN>μ_HR+ (greater importance for TN cases), μ_TN=μ_HR+ (no difference in importance), and μ_TN<μ_HR+ (greater importance for HR+ cases). The y-axis displays the features, with their labels positioned relative to their contribution. Blue dots indicate features that are more important for predicting triple-negative cases, while red dots represent features that are more important for hormone receptor-positive cases. The central black dots are feature for which the average importance is not significantly different between TN and HR+ cases, suggesting equal relevance for both subtypes.

Figure 3.

Relative contributions of features to the prediction of triple-negative (TN) and HR+ breast cancer cases among Bangladeshi women. The x-axis represents the three tested hypotheses using Wilcoxon paired comparisons: μ_TN>μ_HR+ (greater importance for TN cases), μ_TN=μ_HR+ (no difference in importance), and μ_TN<μ_HR+ (greater importance for HR+ cases). The y-axis displays the features, with their labels positioned relative to their contribution. Blue dots indicate features that are more important for predicting triple-negative cases, while red dots represent features that are more important for hormone receptor-positive cases. The central black dots are feature for which the average importance is not significantly different between TN and HR+ cases, suggesting equal relevance for both subtypes.

Figure 4 highlights key numerical features influencing breast cancer subtype predictions by showing how Shapley values vary with change in the feature value. For HR+ cases (Panel A), age-related features, such as age at menarche and age at first birth, showed a decreasing trend in predictive importance as values increase, suggesting that younger ages at these reproductive milestones contribute more to model predictions. The gap between the first marriage and first birth exhibits a relatively stable trend, with a slight increase at wider gaps. In contrast, for TNBC cases (Panel B), an opposite trend was observed for the gap between first marriage and first baby, where an increasing gap was associated with stronger predictive importance. Additionally, age-related features, such as age at first birth and age at menarche, exhibit varying levels of importance across different values.

5. Discussion

Our study provides crucial insights into the predictors of HR+ and TNBC subtypes among Bangladeshi women, highlighting distinct risk factors that differ from those observed in other high-income countries. The application of machine learning models enabled a robust analysis of these risk factors and provided valuable insights into their contribution in HR+ and TNBC classification. Among the models tested, XGBoost demonstrated the highest predictive accuracy, supporting its utility in clinical decision-making for breast cancer diagnosis and subtype classification. The integration of the Shapley values allowed for explainability in our models, identifying key predictors for each breast cancer subtype. Our findings highlight the critical role of socioeconomic and reproductive factors in shaping breast cancer subtypes among Bangladeshi women, revealing both alignments and divergences with global trends observed in developed nations. While the established literature in high-income countries emphasizes delayed childbearing, prolonged hormonal exposure, and obesity as primary risk factors for breast cancer[

18], our study suggests a more nuanced interplay of economic, reproductive, and demographic determinants in Bangladesh.

5.1. Socioeconomic Disparities and Breast Cancer Risk

One of the key findings of this study is the strong association between residence in a metropolitan area and an increased risk for both HR+ and TNBC. This aligns with global patterns where urbanization is linked to increased breast cancer incidence due to lifestyle factors such as diet, pollution, and delayed reproduction[

19]. However, a unique observation is that residing in an urban (non-metropolitan) area is predictive of TNBC but appears to be protective for HR+. This suggests that the urban-rural divide in Bangladesh may reflect distinct environmental and healthcare access disparities that differ from those of developed nations, where urbanization is generally associated with an overall increase in breast cancer risk.

Employment status also emerged as a significant factor, with employment predicting a higher risk of HR+ while being protective for TNBC. This is in contrast to findings from developed nations, where employment is often correlated with better healthcare access and preventative care, potentially reducing breast cancer risk[

20]. In Bangladesh, this trend may reflect occupational stress, exposure to environmental toxins, or differences in access to reproductive healthcare among working women.

Education level also demonstrated an intriguing trend—higher education (13–20 years) was predictive of HR+ but protective for TNBC. This deviates from the patterns seen in high-income countries, where higher education typically correlates with lower TNBC breast cancer risk due to better health awareness and access to medical care[

21]. In Bangladesh, higher education may be linked to delayed childbirth and changes in reproductive behavior, thereby increasing HR+ risk while reducing exposure to risk factors associated with TNBC.

5.2. Reproductive Health and Breast Cancer Subtypes

Reproductive factors play a crucial role in shaping breast cancer risk, with BMI undernutrition being significantly predictive of HR+ but protective for TNBC. This contrasts with developed nations, where obesity is a well-established risk factor for HR+, whereas undernutrition is rarely considered a major determinant[

22]. The protective effect of undernutrition on TNBC suggests that metabolic and nutritional deficiencies may influence the aggressive nature of breast cancer subtypes differently in South Asian populations.

Cesarean section as a mode of delivery was found to be protective against TNBC, whereas abortion (≥1) was predictive of TNBC risk. This contradicts global trends, in which reproductive surgeries and terminations have not shown consistent subtype-specific effects[

23]. The association between cesarean delivery and reduced TNBC risk may reflect underlying health-seeking behaviors or unmeasured confounders such as gestational health complications that influence long-term cancer risk.

Age-related reproductive factors showed distinct trends. Age at menarche and age at first childbirth showed a decreasing trend in predictive importance with increasing values, suggesting that a younger reproductive age is more strongly associated with HR+ risk. This is in line with studies in developed nations that link early menarche and early first childbirth to prolonged hormonal exposure, thereby increasing the HR+ incidence[

24,

25,

26,

27]. However, the gap between first marriage and first childbirth demonstrated the opposite trend; an increasing gap was strongly predictive of TNBC. This pattern has not been widely documented in developed nations and may reflect cultural and societal pressures in Bangladesh, where extended gaps between marriage and childbirth may be influenced by economic instability, infertility, or prolonged exposure to social stressors. These findings contribute to the growing body of literature on breast cancer epidemiology in low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) and underscore the urgent need for targeted prevention and treatment strategies tailored to the Bangladeshi population.

6. Challenges and Policy Recommendations

One of the major challenges in conducting this study was the lack of a centralized electronic health record (EHR) system in Bangladesh. The absence of standardized medical records makes it difficult to track patient histories, perform longitudinal analyses, and ensure accurate data. Instead, data collection relied on patient interviews and self-reported reproductive histories, which may have introduced a recall bias. Developing a national cancer registry can help mitigate these issues by systematically documenting cancer cases, treatment outcomes, and risk factors.

Additionally, genetic testing and molecular profiling are not widely available in Bangladesh, which limits our ability to incorporate genetic risk factors into the analysis. In developed countries, genetic predispositions, such as BRCA mutations, are key determinants of breast cancer risk, particularly in TNBC cases. Expanding access to genetic testing could provide more comprehensive insights into hereditary cancer risk in Bangladesh and inform personalized treatment approaches.

Our findings underscore the need for tailored breast cancer prevention and treatment strategies in Bangladesh. Given the observed socioeconomic and reproductive disparities, public health interventions should prioritize education on reproductive health, nutrition, and cancer screening programs, particularly for women in metropolitan areas. The association between employment and HR+ risk suggests the need for workplace health policies that promote cancer awareness and facilitate early detection programs.

Furthermore, the distinct reproductive patterns in Bangladesh necessitate localized treatment guidelines that account for factors such as early menarche, a high prevalence of cesarean deliveries, and extended gaps between marriage and first childbirth. Unlike treatment approaches in developed nations, which focus on risk mitigation through hormonal therapies and lifestyle modifications, Bangladeshi women may benefit from interventions that address nutritional deficiencies, metabolic health, and culturally specific reproductive practices.

7. Future Research Directions

While this study provides important insights into breast cancer risk factors in Bangladesh, further research is needed to validate these findings in larger multi-center cohorts. Future studies should aim to incorporate genetic profiling, lifestyle factors, and longitudinal follow-up to better understand the interplay between reproductive behaviors and breast cancer risk. Additionally, investigating potential environmental and dietary factors unique to the Bangladeshi population could offer further explanations for the observed subtype distributions.

Another crucial avenue for research is the development of AI-driven diagnostic tools tailored to LMICs. Given the success of XGBoost in our study, future efforts should explore its integration into real-world clinical settings and assess its utility in aiding physicians in risk assessment and subtype classification. The adoption of ML-based tools in oncology has the potential to bridge healthcare gaps in resource-limited environments, making early detection more accessible and cost-effective.

8. Conclusions

This study provides novel insights into the distinct socio-demographic and reproductive predictors of HR+ and TNBC subtypes in Bangladeshi women. Our findings highlight the importance of tailored public health interventions, improved healthcare accessibility, and the potential of machine learning models for breast cancer risk prediction. Addressing the disparities identified in this study through policy changes, increased awareness, and enhanced screening efforts could lead to better breast cancer outcomes in Bangladesh. Further research is needed to explore the underlying biological mechanisms driving these associations and to develop interventions that bridge the gap between global breast cancer prevention guidelines and local epidemiological realities.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study protocol was approved by the National Institute for Cancer Research and Hospital Ethics Committee (Ref: NICRH/Ethics/2021/89).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent was obtained from all the participants.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Conflicts of Interest

Authors declared no conflict of interest.

References

- Hamid F, Roy T. Unveiling Sociocultural Barriers to Breast Cancer Awareness Among the South Asian Population: Case Study of Bangladesh and West Bengal, India. JMIR Hum Factors. 2025 Jan 10;12:e53969. [CrossRef]

- Urbanization in Bangladesh The Prevalence of Breast Cancer Brings Unique Challenges - The ASCO Post [Internet]. [cited 2024 Mar 11]. Available from: https://ascopost.com/issues/october-25-2021/urbanization-in-bangladesh-the-prevalence-of-breast-cancer-brings-unique-challenges/.

- Wilkinson L, Gathani T. Understanding breast cancer as a global health concern. Br J Radiol. 2022 Feb 1;95(1130):20211033. [CrossRef]

- Hossain MS, Ferdous S, Karim-Kos HE. Breast cancer in South Asia: A Bangladeshi perspective. Cancer Epidemiology. 2014 Oct 1;38(5):465–70. [CrossRef]

- Ma H, Bernstein L, Pike MC, Ursin G. Reproductive factors and breast cancer risk according to joint estrogen and progesterone receptor status: a meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Breast Cancer Res. 2006;8(4):R43. [CrossRef]

- Bui OT, Tran HT, Nguyen SM, Dao TV, Bui QV, Pham AT, et al. Menstrual and Reproductive Factors in Association With Breast Cancer Risk in Vietnamese Women: A Case-Control Study. Cancer Control : Journal of the Moffitt Cancer Center. 2022 Nov 12;29:10732748221140206. [CrossRef]

- Xie F, Liu L, Yang H, Liu M, Wang S, Guo J, et al. The Impact of Reproductive Factors on the Risk of Breast Cancer by ER/PR and HER2: A Multicenter Case-Control Study in Northern and Eastern China. Oncologist. 2022 Jan 28;27(1):e1–8. [CrossRef]

- Linnenbringer E, Geronimus AT, Davis KL, Bound J, Ellis L, Gomez SL. Associations between breast cancer subtype and neighborhood socioeconomic and racial composition among Black and White women. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2020;180(2):437–47. [CrossRef]

- Bae SY, Kim S, Lee JH, Lee H chul, Lee SK, Kil WH, et al. Poor prognosis of single hormone receptor- positive breast cancer: similar outcome as triple-negative breast cancer. BMC Cancer. 2015 Mar 18;15:138. [CrossRef]

- Lehrer S, Green S, Rosenzweig KE. Affluence and Breast Cancer. Breast J. 2016 Sep;22(5):564–7. [CrossRef]

- Beaujouan É, Sobotka T. Late childbearing continues to increase in developed countries. Population & Societies. 2019 Oct 9;562(1):1–4.

- World Contraceptive Use | Population Division [Internet]. [cited 2025 Jan 31]. Available from: https://www.un.org/development/desa/pd/data/world-contraceptive-use.

- Aysola K, Desai A, Welch C, Xu J, Qin Y, Reddy V, et al. Triple Negative Breast Cancer – An Overview. Hereditary Genet. 2013;2013(Suppl 2):001. [CrossRef]

- Zagami P, Carey LA. Triple negative breast cancer: Pitfalls and progress. npj Breast Cancer. 2022 Aug 20;8(1):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Francies FZ, Hull R, Khanyile R, Dlamini Z. Breast cancer in low-middle income countries: abnormality in splicing and lack of targeted treatment options. Am J Cancer Res. 2020 May 1;10(5):1568–91.

- Islam MdS, Hussain MdA, Islam S, Mahumud RA, Biswas T, Islam SMS. Age at menarche and its socioeconomic determinants among female students in an urban area in Bangladesh. Sexual & Reproductive Healthcare. 2017 Jun 1;12:88–92. [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan M, Najmi A. The Many Shapley Values for Model Explanation. In: Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Machine Learning [Internet]. PMLR; 2020 [cited 2025 Apr 17]. p. 9269–78. Available from: https://proceedings.mlr.press/v119/sundararajan20b.html.

- Momenimovahed Z, Salehiniya H. Epidemiological characteristics of and risk factors for breast cancer in the world. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press). 2019 Apr 10;11:151–64. [CrossRef]

- Song M, Huang X, Wei X, Tang X, Rao Z, Hu Z, et al. Spatial patterns and the associated factors for breast cancer hospitalization in the rural population of Fujian Province, China. BMC Women’s Health. 2023 May 9;23(1):247. [CrossRef]

- Where You Live, Work, Learn and Play Can Affect Breast Health - HealthyWomen [Internet]. [cited 2025 Mar 13]. Available from: https://www.healthywomen.org/your-care/social-determinents-of-health.

- Sen KK, Nilima S, Zahura FT, Bari W. Do education and living standard matter in breaking barriers to healthcare access among women in Bangladesh? BMC Public Health. 2023 Jul 26;23(1):1431. [CrossRef]

- Neuhouser MarianL, Aragaki AK, Prentice RL, Manson JE, Chlebowski R, Carty CL, et al. Overweight, Obesity and Postmenopausal Invasive Breast Cancer Risk. JAMA Oncol. 2015 Aug;1(5):611–21. [CrossRef]

- Rakoczy K, Kaczor J, Sołtyk A, Jonderko L, Sędzik M, Lizon J, et al. Pregnancy, abortion, and birth control methods’ complicity with breast cancer occurrence. Molecular and Cellular Endocrinology. 2024 Sep 1;590:112264. [CrossRef]

- Horn J, Vatten LJ. Reproductive and hormonal risk factors of breast cancer: a historical perspective. Int J Womens Health. 2017 Apr 27;9:265–72. [CrossRef]

- Lambertini M, Santoro L, Del Mastro L, Nguyen B, Livraghi L, Ugolini D, et al. Reproductive behaviors and risk of developing breast cancer according to tumor subtype: A systematic review and meta-analysis of epidemiological studies. Cancer Treat Rev. 2016 Sep;49:65–76. [CrossRef]

- Anderson KN, Schwab RB, Martinez ME. Reproductive Risk Factors and Breast Cancer Subtypes: A Review of the Literature. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2014 Feb;144(1):1–10. [CrossRef]

- Menarche, menopause, and breast cancer risk: individual participant meta-analysis, including 118 964 women with breast cancer from 117 epidemiological studies. Lancet Oncol. 2012 Nov;13(11):1141–51. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).