Submitted:

28 April 2025

Posted:

29 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

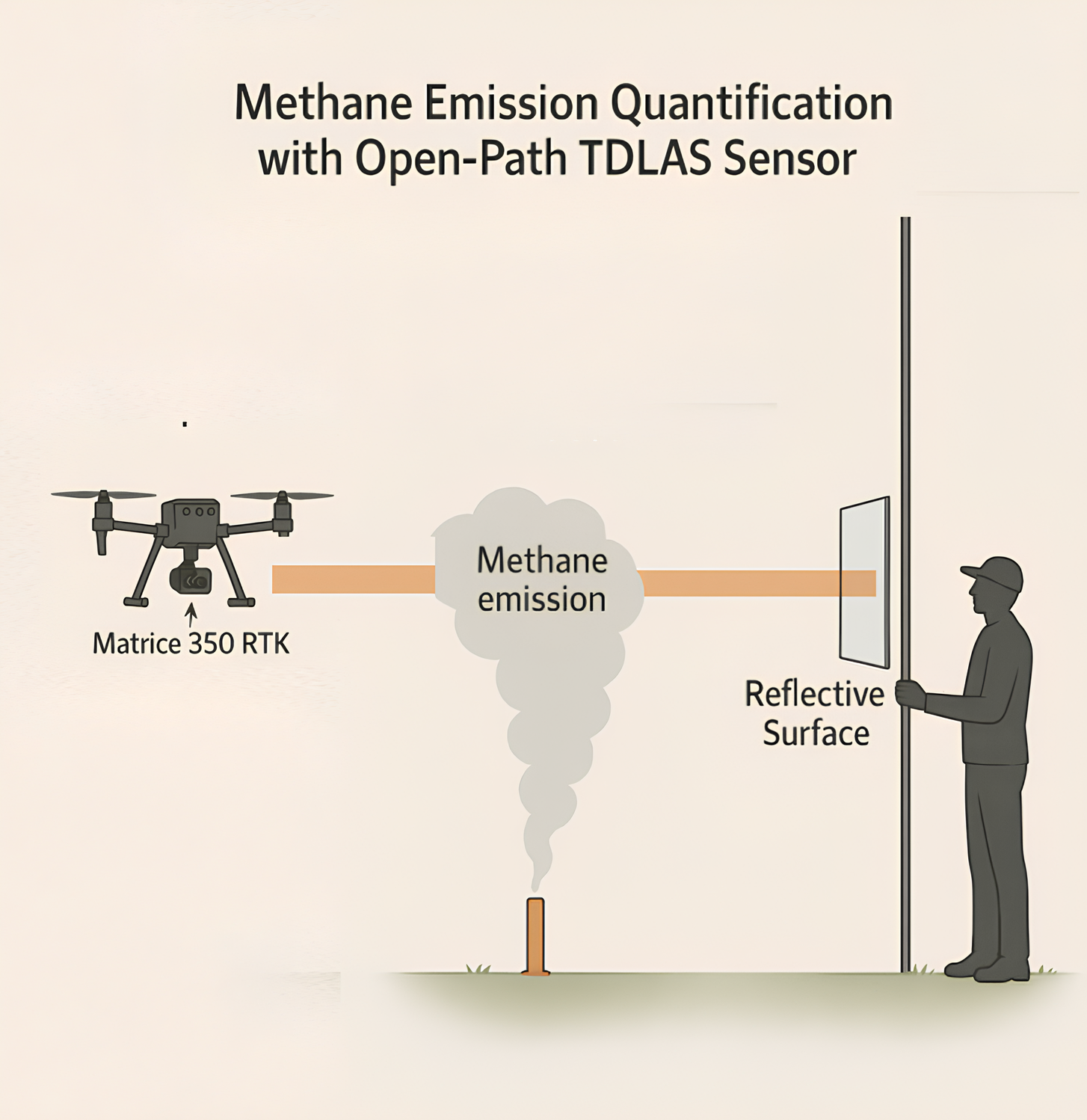

2.1. UAV Platform and Instrumentation

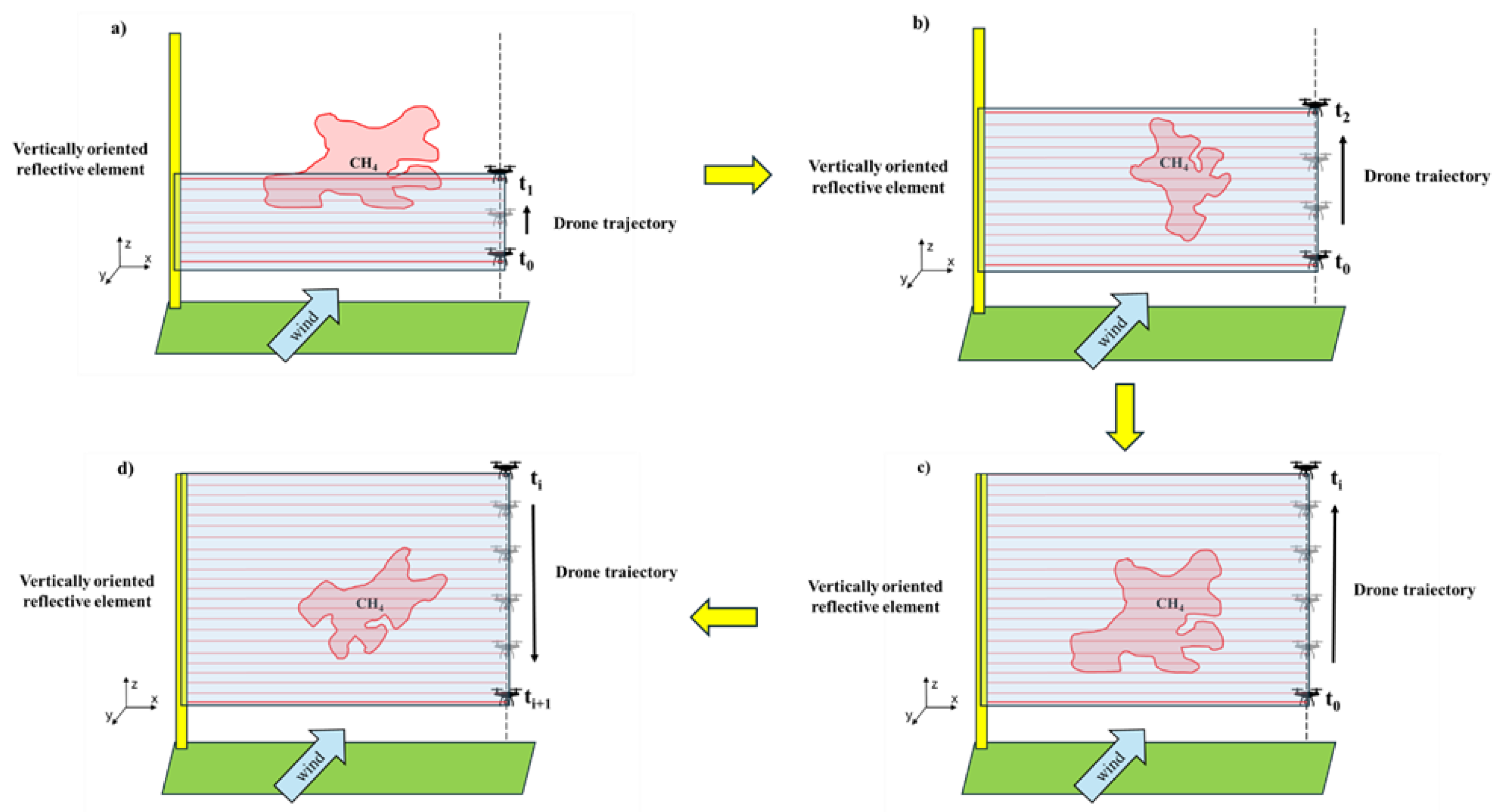

2.2. Mass-Balance Approach

2.2.1. Conversion from ppm-m to Integrated Concentration (g m⁻²)

2.2.2. CH4 Background Measurements

2.2.3. Wind Measurements

2.3. Controlled Release Test

3. Results and Discussion

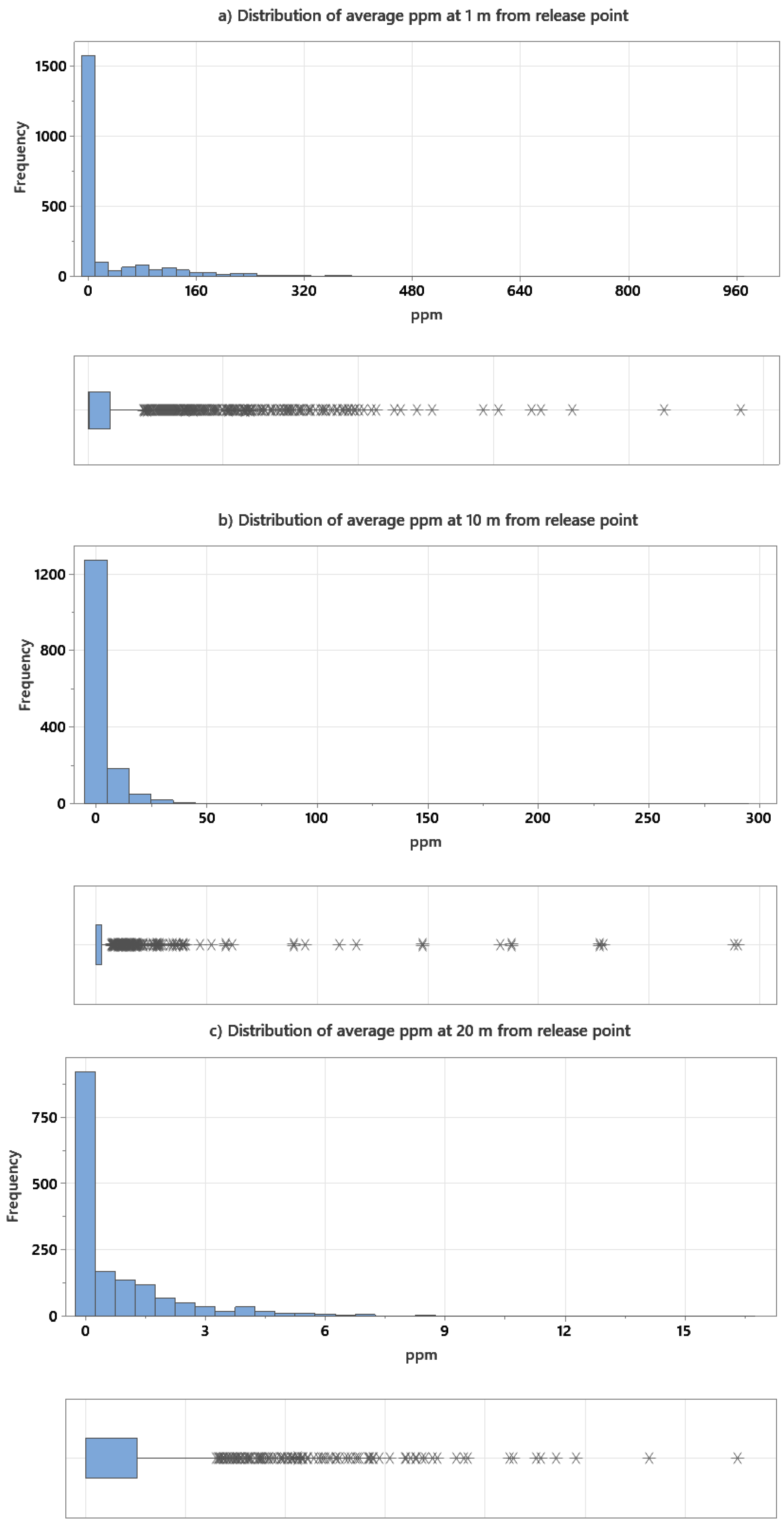

3.1. CH4 Concentration Measurements

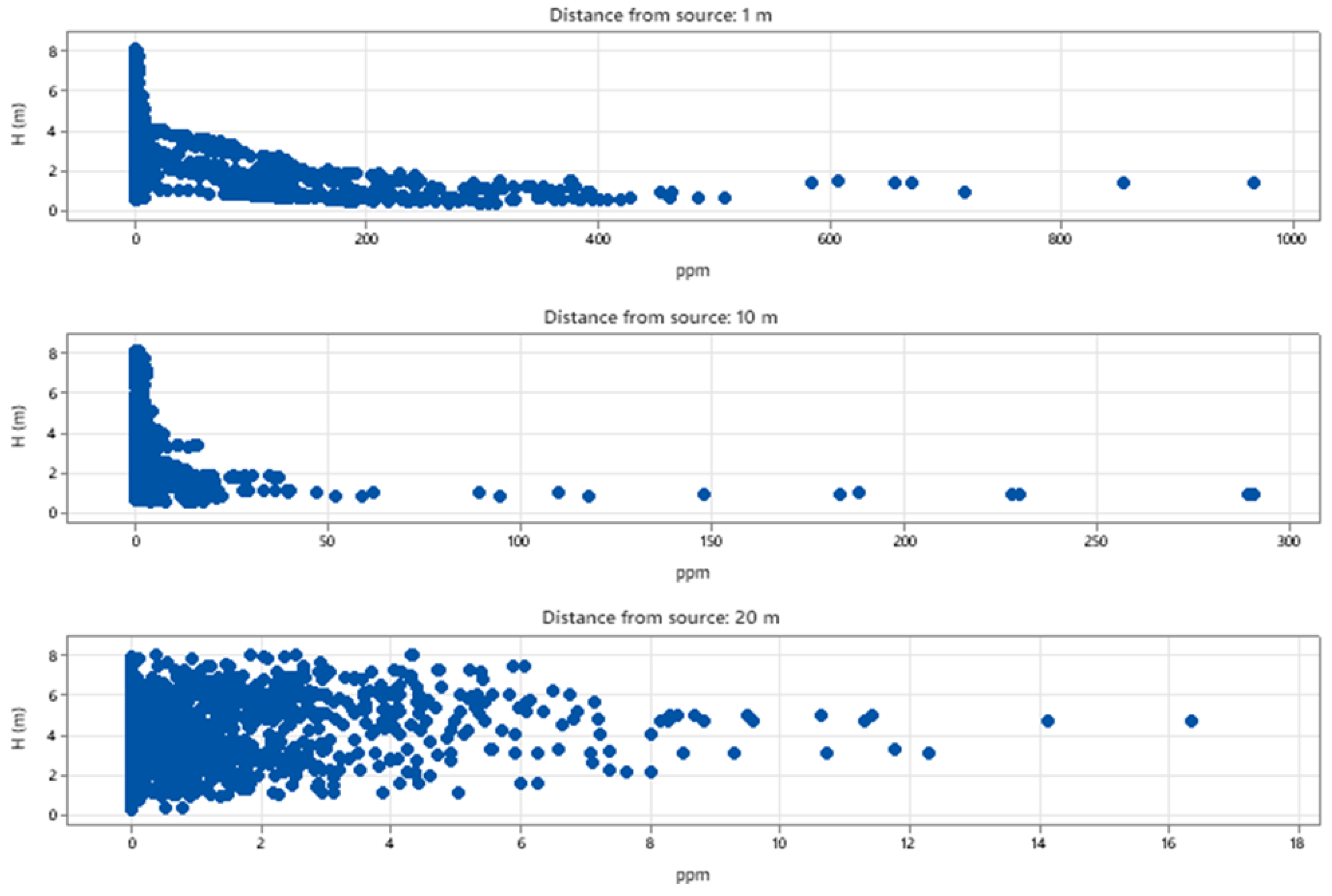

3.2. Vertical Distribution of Average CH4 Concentrations

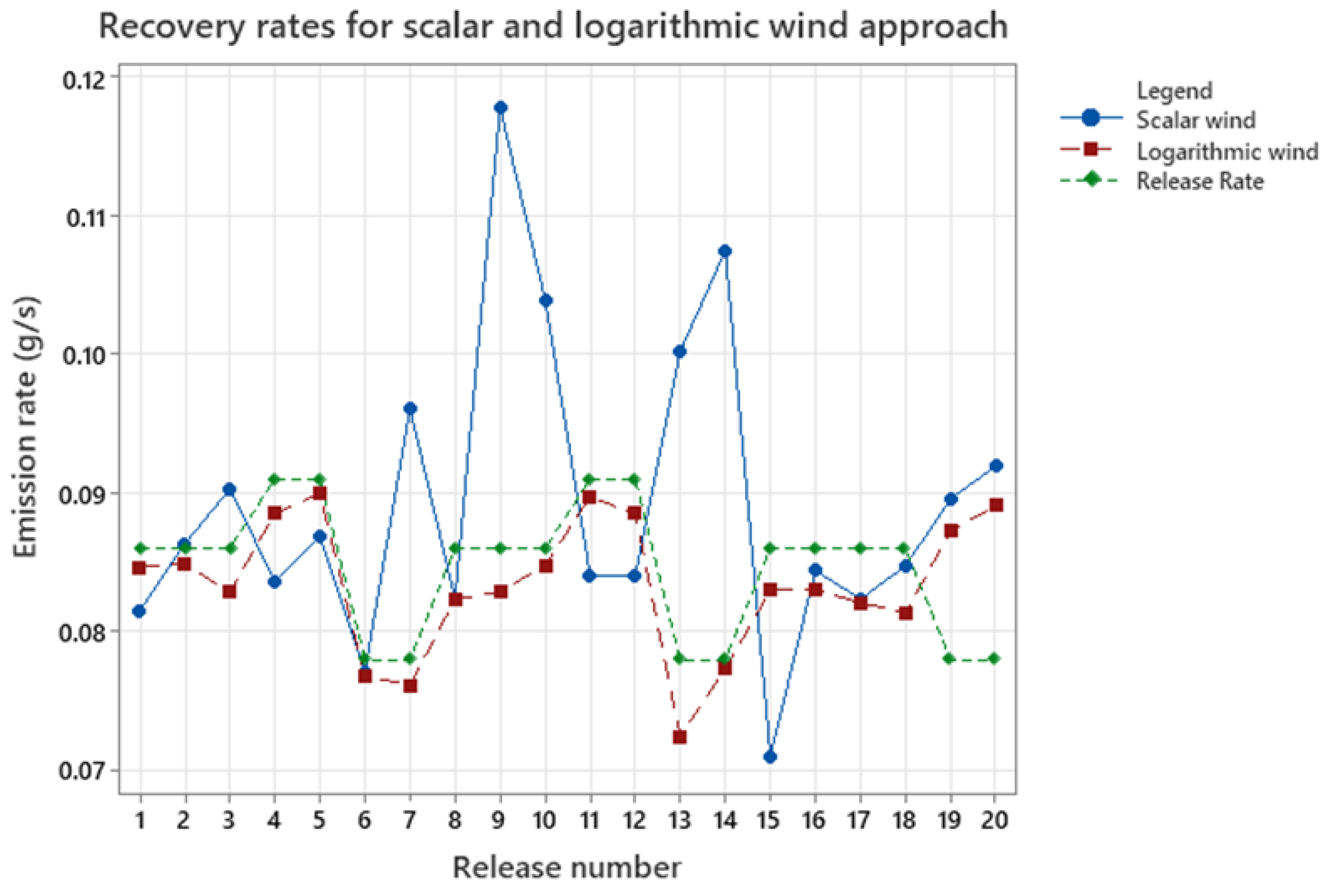

3.3. Emission Estimates

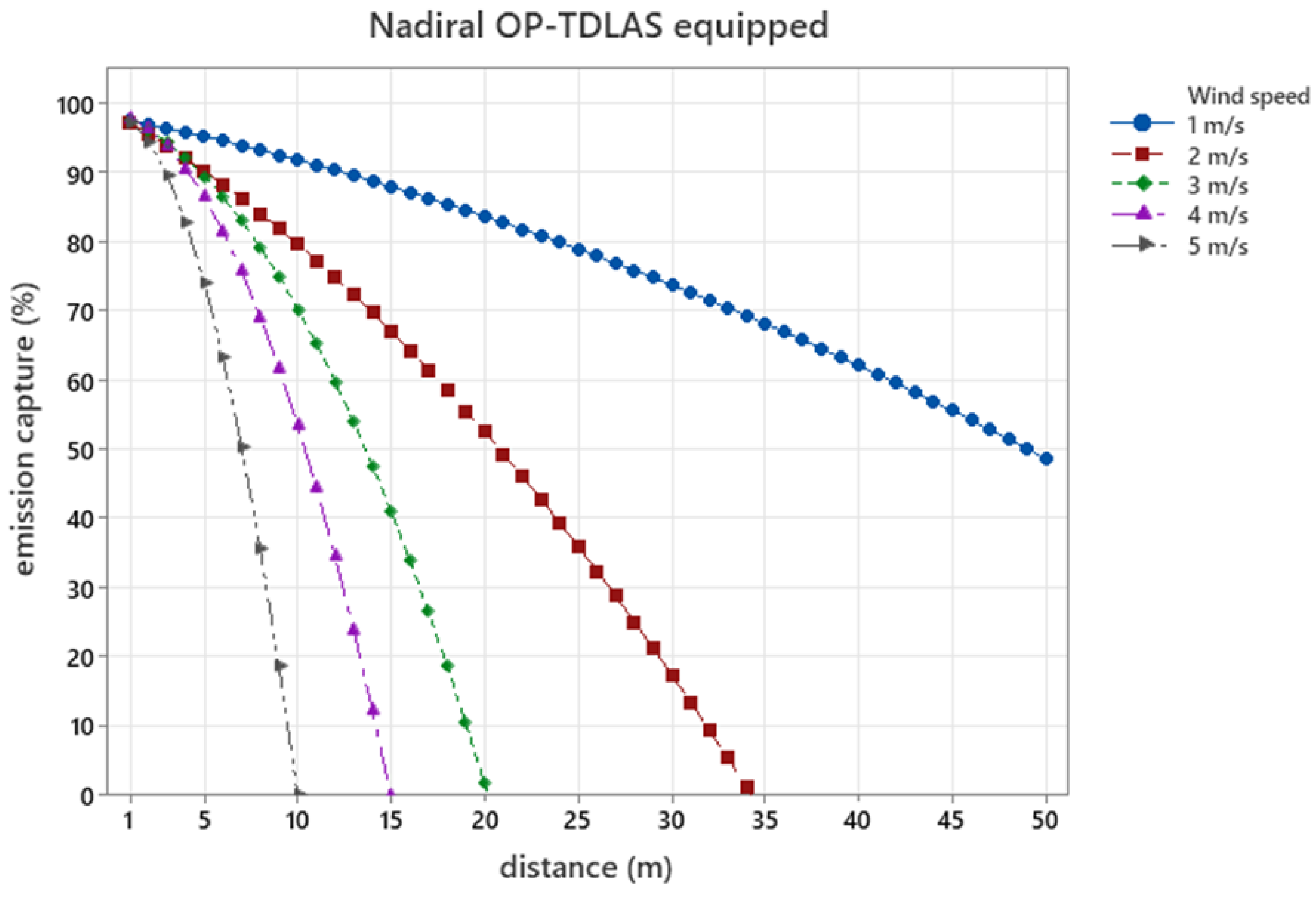

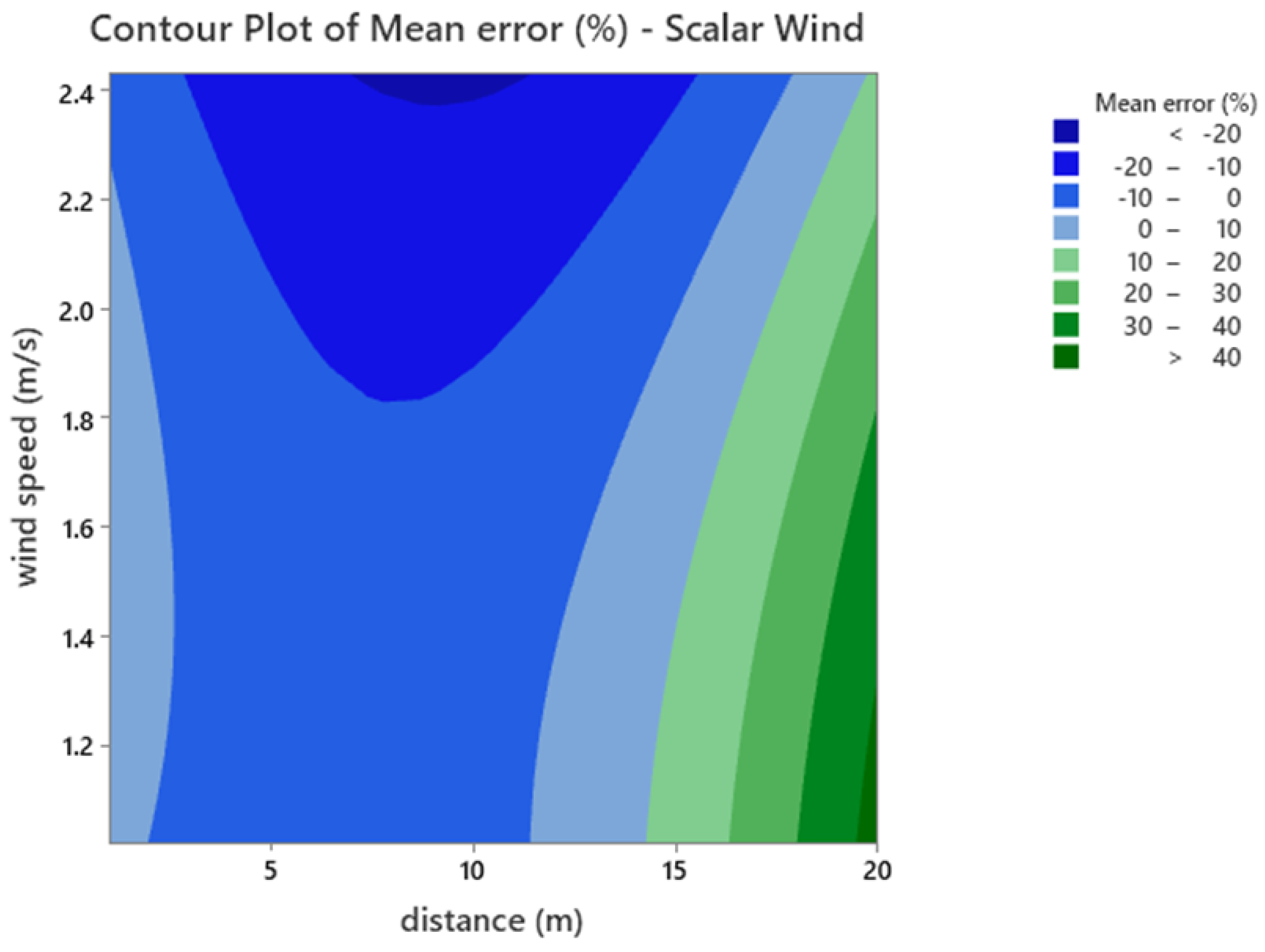

3.4. Optimal Conditions

4. Conclusions

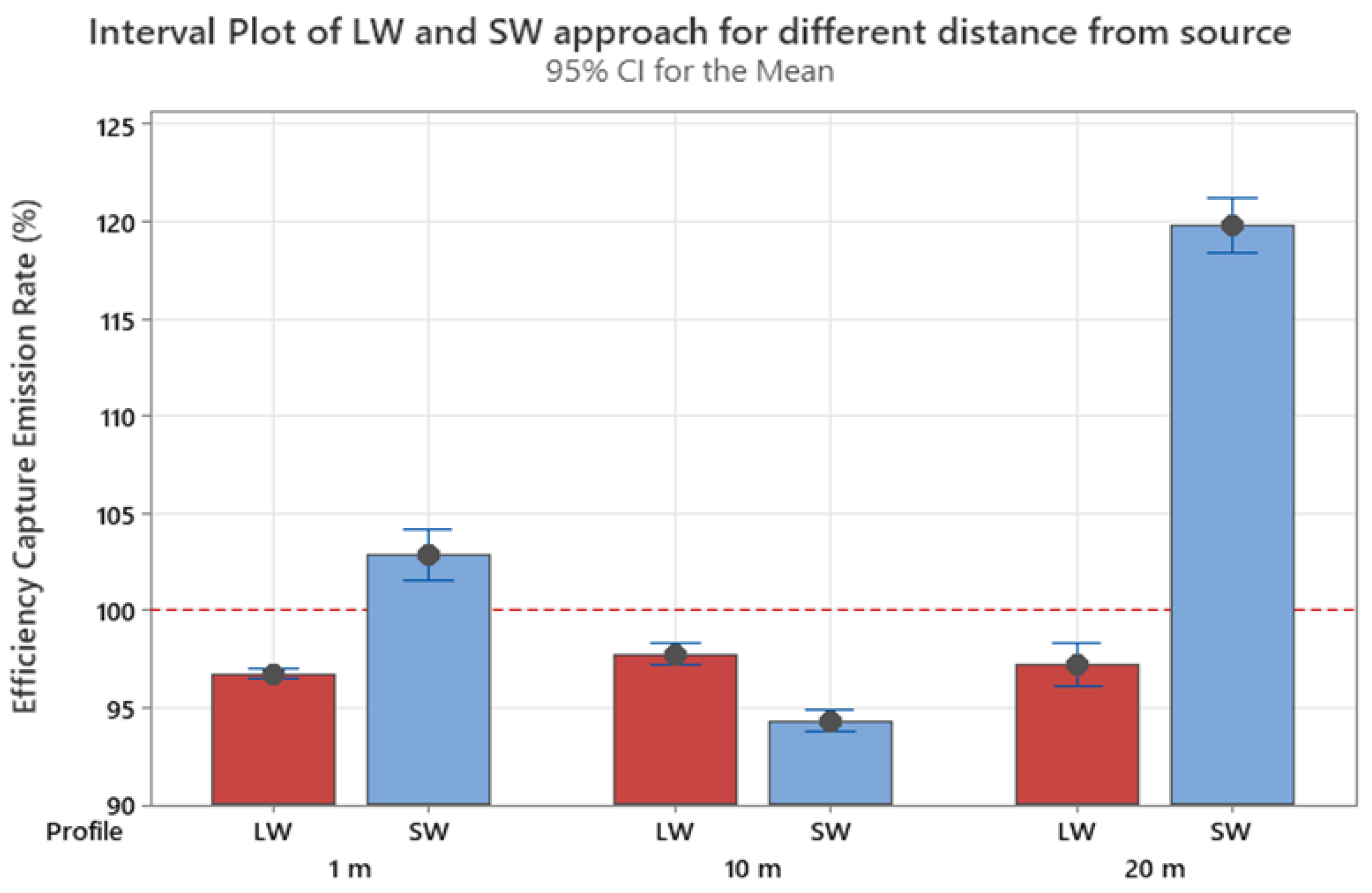

- The recoveries calculated using the LW approach were on average 98%, regardless of the downwind distance from the source.

- The recoveries calculated using the SW approach showed more variable trends with distance, with good correspondence near the source (102%) and marked overestimation at 20 m from the source (120%).

- Experimentally, it was observed that a minimum of 4 scans was sufficient for the LW approach, while it is recommended to increase this number for the SW approach in order to reduce the plume variability induced by atmospheric turbulence.

- Due to the short time required to perform 4 scans (about 40 seconds) and the manoeuvrability of the retroreflector panel, it was easy to ensure the perpendicularity of the plane to the wind during each test. Therefore, wind direction variability was negligible.

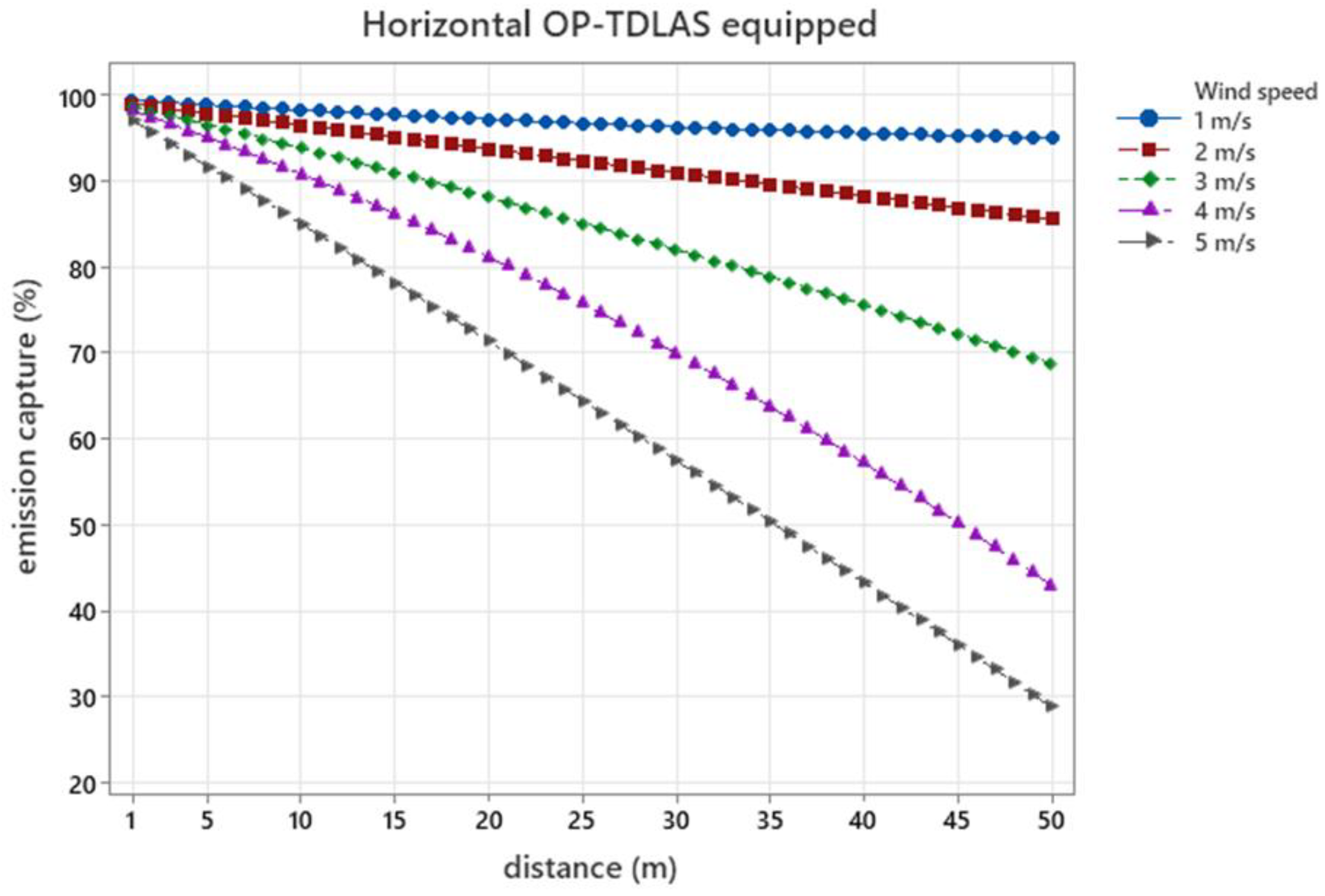

- The results were consistent with numerical simulations carried out using a Lagrangian particle model for pollutant dispersion in the atmosphere, considering two different scenarios: one with a horizontal path and the other with a vertical path for the laser sensor.

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- IPCC, 2021: Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change [Masson-Delmotte, V., P. Zhai, A. Pirani, S.L. Connors, C. Johnson D. and Heltzel R., “Methane emissions measurements of natural gas components using a utility terrain vehicle and portable methane quantification system”. Atmospheric Environment, Volume 144, 2016, Pages 1-7. ISSN 1352-2310. [CrossRef]

- IEA, 2023. World Energy Outlook 2023, IEA, Parigi https://www.iea.org/reports/world-Energy-Outlook-2023, Licenza: CC BY 4.0 (rapporto); CC BY NC SA 4.0 (Allegato A).

- Zavala-Araiza, D, et al. 2018. Methane emissions from oil and gas production sites in Alberta, Canada. Elem Sci Anth, 6: 27. [CrossRef]

- Chan E., Worthy D.E.J., Chan D., Ishizawa M., Moran M.D., Delcloo A., Vogel F., 2020. Eight-year estimates of methane emissions from oil and gas operations in western Canada are nearly twice those reported in inventories. Environ. Sci. Technol., 54, pp. 14899-14909.

- Cusworth, D.H., Bloom, A.A., Ma, S. et al., 2021. A Bayesian framework for deriving sector-based methane emissions from top-down fluxes. Commun Earth Environ 2, 242 (2021). [CrossRef]

- MacKay, K., Lavoie, M., Bourlon, E. et al. 2021. Methane emissions from upstream oil and gas production in Canada are underestimated. Sci Rep 11, 8041 (2021). [CrossRef]

- Olczak M., Piebalgs A., Balcombe P., 2023. A global review of methane policies reveals that only 13% of emissions are covered with unclear effectiveness. One Earth, Volume 6, Issue 5, Pages 519-535. ISSN 2590-3322. [CrossRef]

- Desjardins R.L., Worth D.E., Pattey E., VanderZaag A., Srinivasan R., Mauder M., Worthy D., Sweeney C., Metzger S., 2018. The challenge of reconciling bottom-up agricultural methane emissions inventories with top-down measurements. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, Volume 248, Pages 48-59. ISSN 0168-1923. [CrossRef]

- Dubey L., Cooper J., Staffell I., Hawkes A., Balcombe P., 2023. Comparing satellite methane measurements to inventory estimates: A Canadian case study. Atmospheric Environment: X, Volume 17, 100198. ISSN 2590-1621. [CrossRef]

- Sadavarte P., Pandey S., Maasakkers J.D., Lorente A., Borsdorff T., Denier van der Gon H., Houweling S., Aben I., 2021. Methane Emissions from Superemitting Coal Mines in Australia Quantified Using TROPOMI Satellite Observations. Environmental Science & Technology 2021 55 (24), 16573-16580. [CrossRef]

- Yeşiller N., Hanson J.L., Manheim D.C., Newman S., Guha A., 2022. Assessment of methane emissions from a California landfill using concurrent experimental, inventory, and modeling approaches. Waste Management, Volume 154, Pages 146-159. ISSN 0956-053X. [CrossRef]

- Liu Y., Paris J.D., Vrekoussis M., Quéhé P.Y, Desservettaz M., Kushta J., Dubart F., Demetriou D., Bousquet P., Sciare J., 2023. Reconciling a national methane emission inventory with in-situ measurements. Science of The Total Environment, Volume 901, 165896. ISSN 0048-9697. [CrossRef]

- Brandt, A. R. Heath, G.A., Kort, E.A. O’Sullivan, F., Pétron, G., Jordaan, S.M., Tans, P., Wilcox, J., Gopstein, A.M., Arent, D., Wofsy, S., Brown, N.J., Bradley, R., Stucky, G.D., Eardley, D., Harriss, R., 2014. Methane leaks from North American natural gas systems. Science 343, 733–735. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/260211785.

- Heath, G., Warner, E., Steinberg, D., Brandt, A. R., 2015. Estimating U. S. Methane Emissions from the Natural Gas Supply Chain: Approaches, Uncertainties, Current Estimates, and Future Studies.

- Brandt, A.R., Heath, G.A., Coole, D. 2016. Methane Leaks from Natural Gas Systems Follow Extreme Distributions. Environ. Sci. Technol. [CrossRef]

- Alvarez, R. A., Zavala-Araiza D., Lyon, D.R., Allen, D.T., Barkley, Z.R., Brandt, A.R., Davis, K.J., Scott C. Herndon, S.C., Jacob, D.J., Karion, A., Kort, E.A., Lamb, B.K., Lauvaux, T., Maasakkers J. D., Marchese, A.J., Omara, M., Pacala, S. W., Peischl, J., Robinson, A.L., Shepson, P.B., Sweeney, C., Townsend-Small, A., Wofsy, S.C., Hamburg, S.P., 2018. Assessment of methane emissions from the U.S. oil and gas supply chain. Science. eaar7204 (2018). https://www.researchgate.net/publication/325916333_Assessment_of_methane_emissions_from_the_US_oil_and_gas_supply_chain.

- Zhang S., Ma J., Zhang X., Guo C., 2023. Atmospheric remote sensing for anthropogenic methane emissions: Applications and research opportunities. Science of The Total Environment, Volume 893, 164701. ISSN 0048-9697. [CrossRef]

- Shaw Jacob T., Allen G., Pitt J., Mead M.I., Purvis R.M., Dunmore R., Wilde S., Shah A., Barker P., Bateson P., Bacak A., Lewis A.C., Lowry D., Fisher R., Lanoisellé M., Ward R.S., 2019. A baseline of atmospheric greenhouse gases for prospective UK shale gas sites. Science of The Total Environment, Volume 684, Pages 1-13. ISSN 0048-9697. [CrossRef]

- Knox, S. H., and Coauthors, 2019. FLUXNET-CH4 Synthesis Activity: Objectives, Observations, and Future Directions. Bull. Amer. Meteor. Soc., 100, 2607–2632. [CrossRef]

- Wu T, Cheng J, Wang S, He H, Chen G, Xu H, Wu S., 2023. Hotspot Detection and Estimation of Methane Emissions from Landfill Final Cover. Atmosphere. 14(11):1598. [CrossRef]

- Gazola B., Mariano E., Mota Neto L.V., Rosolem C.A., 2024. Greenhouse gas and ammonia emissions from a maize-soybean rotation under no-till as affected by intercropping with forage grass and nitrogen fertilization. Agricultural and Forest Meteorology, Volume 345, 109855. ISSN 0168-1923. [CrossRef]

- Stadler C., Fusé V.S., Linares S., Guzmán S.A., Juliarena M.P., 2024. Accessible sampling methodologies to quantify the net methane emission from landfill cells. Atmospheric Pollution Research, Volume 15, Issue 3, 102011. ISSN 1309-1042. [CrossRef]

- Zazzeri G., Lowry D., Fisher R.E., France J.L., Lanoisellé M., Nisbet E.G., 2015. Plume mapping and isotopic characterisation of anthropogenic methane sources. Atmospheric Environment, Volume 110, Pages 151-162. ISSN 1352-2310. [CrossRef]

- Johnson M.R., Tyner D.R., Szekeres A.J., 2021. Blinded evaluation of airborne methane source detection using Bridger Photonics LiDAR. Remote Sensing of Environment, Volume 259, 2021,112418. ISSN 0034-4257. [CrossRef]

- Fischer J.C., Cooley D., Chamberlain S., Gaylord A., Griebenow C.J., Hamburg S.P., Salo J., Schumacher R., Theobald D., Ham J., 2017. Rapid, Vehicle-Based Identification of Location and Magnitude of Urban Natural Gas Pipeline Leaks. Environmental Science & Technology 51 (7), 4091-4099. [CrossRef]

- Lowry D., Fisher R.E., France J.L., Coleman M., Lanoisellé M., Zazzeri G., Nisbet E.G., Shaw Jacob T., Allen G., Pitt J., Ward R.S., 2020. Environmental baseline monitoring for shale gas development in the UK: Identification and geochemical characterisation of local source emissions of methane to atmosphere. Science of The Total Environment, Volume 708, 2020, 134600. ISSN 0048-9697. [CrossRef]

- Ayasse, A.K., Thorpe, A.K., Cusworth, D.H., Kort, E.A., Negron, A.G., Heckler, J., Asner, G., Duren, R.M., 2022. Methane remote sensing and emission quantification of offshore shallow water oil and gas platforms in the Gulf of Mexico. Environ. Res. Lett. 17. [CrossRef]

- Wang, M., Shi, W., Tang, J., 2011. Water property monitoring and assessment for China’s inland Lake Taihu from MODIS-Aqua measurements. Remote Sens. Environ. 115, 841–854. [CrossRef]

- O'Shea, S. J., Allen, G., Gallagher, M. W., Bower, K., Illingworth, S. M., Muller, J. B. A., Jones, B. T., Percival, C. J., Bauguitte, S. J.-B., Cain, M., Warwick, N., Quiquet, A., Skiba, U., Drewer, J., Dinsmore, K., Nisbet, E. G., Lowry, D., Fisher, R. E., France, J. L., Aurela, M., Lohila, A., Hayman, G., George, C., Clark, D. B., Manning, A. J., Friend, A. D., and Pyle, J.,2014. Methane and carbon dioxide fluxes and their regional scalability for the European Arctic wetlands during the MAMM project in summer 2012. Atmos. Chem. Phys., 14, 13159–13174. [CrossRef]

- Heimburger, AMF, et al, 2017. Assessing the optimized precision of the aircraft mass balance method for measurement of urban greenhouse gas emission rates through averaging. Elem Sci Anth, 5: 26. [CrossRef]

- Tong X., van Heuven S., Scheeren B., Kers B., Hutjes R., Chen H., 2023. Aircraft-Based AirCore Sampling for Estimates of N2O and CH4 Emissions. Environmental Science & Technology 57 (41), 15571-15579. [CrossRef]

- Shaw, J.T.; Shah, A., Han, Y; Allen, G. 2021. Methods for quantifying methane emissions using unmanned aerial vehicles: a review. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A.3792020045020200450. [CrossRef]

- Lavoie T.N., Shepson P.B., Cambaliza M.O.L., Stirm B.H., Karion A., Sweeney C., Yacovitch T.I., Herndon S.C., Lan X., and Lyon D., 2015. Aircraft-Based Measurements of Point Source Methane Emissions in the Barnett Shale Basin. Environmental Science & Technology 49 (13), 7904-7913. [CrossRef]

- Gasbarra D., Toscano P., Famulari D., Finardi S., Di Tommasi P., Zaldei A., Carlucci P., Magliulo E., Gioli B., 2019. Locating and quantifying multiple landfills methane emissions using aircraft data. Environmental Pollution, Volume 254, Part B, 112987. ISSN 0269-7491. [CrossRef]

- Kunkel W.M., Carre-Burritt A.E., Aivazian G.S., Snow N.C., Harris J.T., Mueller T.S., Roos P.A., and Thorpe M.J., 2023. Extension of Methane Emission Rate Distribution for Permian Basin Oil and Gas Production Infrastructure by Aerial LiDAR. Environmental Science & Technology 57 (33), 12234-12241. [CrossRef]

- Gaudioso D., 2022. Le emissioni di metano in Italia - Stime di emissione e priorità di intervento per la loro riduzione – giugno 2022. https://www.wwf.it/cosa-facciamo/pubblicazioni/le-emissioni-di-metano-initalia/.

- Fosco, D., De Molfetta, M., Renzulli, P., & Notarnicola, B., 2024. Progress in monitoring methane emissions from landfills using drones: an overview of the last ten years. Science of The Total Environment, 945, 173981. [CrossRef]

- Yao, H.; Qin, R.; Chen, X. 2019. Unmanned Aerial Vehicle for Remote Sensing Applications—A Review. Remote Sens., 11, 1443. [CrossRef]

- Vinković K., Andersen T., de Vries M., Bert Kers B., van Heuven S., Peters W., Hensen A., van den Bulk P., Chen H., 2022. Evaluating the use of an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV)-based active AirCore system to quantify methane emissions from dairy cows. Science of The Total Environment, Volume 831, 154898. ISSN 0048-9697. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T.; Vinkovic, K.; de Vries, M.; Kers, B.; Necki, J.; Swolkien, J.; Roiger, A.; Peters, W.; Chen, H. 2021. Quantifying methane emissions from coal mining ventilation shafts using an unmanned aerial vehicle (UAV)-based active AirCore system, Atmospheric Environment: X, Volume 12, 100135, ISSN 2590-1621. [CrossRef]

- Andersen, T., Zhao, Z., de Vries, M., Necki, J., Swolkien, J., Menoud, M., Röckmann, T., Roiger, A., Fix, A., Peters, W., and Chen, H., 2023. Local-to-regional methane emissions from the Upper Silesian Coal Basin (USCB) quantified using UAV-based atmospheric measurements, Atmos. Chem. Phys., 23, 5191–5216. [CrossRef]

- Allen G., Hollingsworth P., Kabbabe K., Pitt J.R., Mead M.I., Illingworth S., Roberts G., Bourn M., Shallcross D.E., Percival C.J., 2019. The development and trial of an unmanned aerial system for the measurement of methane flux from landfill and greenhouse gas emission hotspots. Waste Management, Volume 87, Pages 883-892, ISSN 0956-053X. [CrossRef]

- Ali N.B.H., Abichou T. and Green R., 2020. Comparing estimates of fugitive landfill methane emissions using inverse plume modeling obtained with Surface Emission Monitoring (SEM), Drone Emission Monitoring (DEM), and Downwind Plume Emission Monitoring (DWPEM). Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association, 70:4, 410-424. [CrossRef]

- Yong, H.; Allen, G.; Mcquilkin, J.; Ricketts, H.; Shaw, J.T., 2024. Lessons learned from a UAV survey and methane emissions calculation at a UK landfill. Waste Management, Volume 180, Pages 47-54. ISSN 0956-053X. [CrossRef]

- Yang, S., Talbot, R.W., Frish, M.B., Golston, L.M., Aubut, N.F., Zondlo, M.A., Gretencord, C., McSpiritt, J., 2018. Natural Gas Fugitive Leak Detection Using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle: Measurement System Description and Mass Balance Approach. Atmosphere, Volume 9, 383. [CrossRef]

- Golston, L.M.; Aubut, N.F.; Frish, M.B.; Yang, S.; Talbot, R.W.; Gretencord, C.; McSpiritt, J.; Zondlo, M.A., 2018. Natural Gas Fugitive Leak Detection Using an Unmanned Aerial Vehicle: Localization and Quantification of Emission. Rate. Atmosphere 9, 333. [CrossRef]

- Desjardins, R. L; Denmead, O.T.; Harper, L.; McBain, M.; Masse´, D.; Kaharabata, S.; 2004. Evaluation of a micrometeorological mass balance method employing an open-path laser for measuring methane emissions. Atmospheric Environment, Volume 38, Issue 39, Pages 6855-6866, ISSN 1352-2310. [CrossRef]

- Gålfalk M, Nilsson Påledal S, Bastviken D., 2021. Sensitive Drone Mapping of Methane Emissions without the Need for Supplementary Ground-Based Measurements. ACS Earth Space Chemistry; 5(10):2668-2676. [CrossRef]

- De Molfetta, M., Fosco, D., Renzulli, P. A., & Notarnicola, B., 2025. Identification and treatment of false methane values produced by the TDLAS technology equipped on UAVs. Integrated Environmental Assessment and Management. [CrossRef]

- Allen, G., Williams, P., Ricketts, H., Shah, A., Hollingsworth, P., Kabbabe, K., Helmore, J., Finlayson, A., Robinson, R., Rees-White, T., Beaven, R., Scheutz, C., Fredenslund, A., 2018. Validation of landfill methane measurements from an unmanned aerial system. Project SC 160006. Bristol, UK: Environment Agency. Available online: https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/684501/Validation_of_landfill_methane_measurements_from_an_unma nned_aerial_system_-_report.pdf.

- Allen G., Hollingsworth P., Kabbabe K., Pitt J.R., Mead M.I., Illingworth S., Roberts G., Bourn M., Shallcross D.E., Percival C.J., 2017. The development and trial of an unmanned aerial system for the measurement of methane flux from landfill and greenhouse gas emission hotspots. Waste Management, Volume 87, Pages 883-892, ISSN 0956-053X. [CrossRef]

- Morales, R., Ravelid, J., Vinkovic, K., Korbeń, P., Tuzson, B., Emmenegger, L., Chen, H., Schmidt, M., Humbel, S., and Brunner, D., 2022. Controlled-release experiment to investigate uncertainties in UAV-based emission quantification for methane point sources. Atmos. Meas. Tech., 15, 2177–2198. [CrossRef]

- Abichou, T.; Bel Hadj Ali, N.; Amankwah, S.; Green, R.; Howarth, E.S. 2023. Using Ground- and Drone-Based Surface Emission Monitoring (SEM) Data to Locate and Infer Landfill Methane Emissions. Methane, 2, 440-451. [CrossRef]

- Fosco, D., Molfetta, M. D., Renzulli, P., Notarnicola, B., Carella, C., & Fedele, G., 2025. Innovative drone-based methodology for quantifying methane emissions from landfills. Waste Management, Vol. 195, pp. 79–91. [CrossRef]

- Corbett, A.; Smith, B., 2022. A Study of a Miniature TDLAS System Onboard Two Unmanned Aircraft to Independently Quantify Methane Emissions from Oil and Gas Production Assets and Other Industrial Emitters. Atmosphere, 13, 804. [CrossRef]

- Cossel, K. C., Waxman, E. M., Hoenig, E., Hesselius, D., Chaote, C., Coddington, I., and Newbury, N. R., 2023. Ground-to-UAV, laser-based emissions quantification of methane and acetylene at long standoff distances. Atmos. Meas. Tech., 16, 5697–5707. [CrossRef]

- Soskind M.G., Li N.P., Moore D.P., Chen Y., Wendt L.P., McSpiritt J., Zondlo M.A., Wysocki G., 2023. Stationary and drone-assisted methane plume localization with dispersion spectroscopy. Remote Sensing of Environment, Volume 289, 113513, ISSN 0034-4257. [CrossRef]

- Shokri, A. 2018. Application of Sono–photo-Fenton process for degradation of phenol derivatives in petrochemical wastewater using full factorial design of experiment. Int J Ind Chem 9, 295–303. [CrossRef]

- Baştürk, E.; Alver, A. 2019. Modeling azo dye removal by sono-fenton processes using response surface methodology and artificial neural network approaches. Journal of Environmental Management, Volume 248, 109300. ISSN 0301-4797. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.Q.; Lee, B.C.Y.; Ong, S.L.; Hu, J.Y. 2021. Application of a Multiobjective Artificial Neural Network (ANN) in Industrial Reverse Osmosis Concentrate Treatment with a Fluidized Bed Fenton Process: Performance Prediction and Process Optimization. ACS ES&T Water 2021 1 (4), pages 847-858. [CrossRef]

| Date | Number test | Time (Take off – Landing) |

Downwind distance [m] |

Release Rate [g s-1] |

Mean Wind speed [m s-1] |

Mean Wind direction [deg Nord] |

Angle between wind and plane [deg Nord] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 15/01/2024 | 1 | 11:28:05 - 11:28:54 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.006 | 2.32 ± 0.34 | 266 ± 20 | 82 ± 20 |

| 2 | 11:35:03 - 11:35:52 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.007 | 2.41 ± 0.30 | 294 ± 28 | 84 ± 28 | |

| 3 | 11:42:22 - 11:43:12 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.009 | 2.02 ± 0.32 | 313 ± 18 | 84 ± 18 | |

| 4 | 12:00:05 - 12:00:52 | 10 | 0.091 ± 0.009 | 1.33 ± 0.15 | 311 ± 16 | 87 ± 16 | |

| 5 | 12:06:26 - 12:07:07 | 10 | 0.091 ± 0.008 | 1.77 ± 0.25 | 288 ± 25 | 96 ± 25 | |

| 6 | 12:20:03 - 12:20:54 | 20 | 0.078 ± 0.007 | 2.42 ± 0.62 | 302 ± 20 | 98 ± 20 | |

| 7 | 12:26:01 - 12:26:51 | 20 | 0.078 ± 0.006 | 2.43 ± 0.77 | 299 ± 26 | 101 ± 30 | |

| 16/01/2024 | 8 | 15:24:16 - 15:25:01 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.007 | 1.64 ± 0.30 | 302 ± 27 | 81 ± 27 |

| 9 | 15:31:01 - 15:31:53 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.009 | 1.97 ± 0.51 | 288 ± 31 | 101 ± 25 | |

| 10 | 15:39:12 - 15:40:00 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.007 | 1.33 ± 0.18 | 143 ± 21 | 104 ± 21 | |

| 11 | 15:47:01 - 15:47:52 | 10 | 0.091 ± 0.008 | 1.28 ± 0.08 | 283 ± 18 | 86 ± 21 | |

| 12 | 15:52:25 - 15:53:04 | 10 | 0.091 ± 0.007 | 1.49 ± 0.21 | 247 ± 15 | 92 ± 23 | |

| 13 | 15:57:12 - 15:58:01 | 20 | 0.078 ± 0.007 | 1.96 ± 0.27 | 304 ± 25 | 91 ± 25 | |

| 14 | 16:05:42 - 16:06:33 | 20 | 0.078 ± 0.007 | 1.46 ± 0.25 | 259 ± 23 | 103 ± 42 | |

| 17/01/2024 | 15 | 10:19:18 - 10:20:02 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.008 | 1.91 ± 0.11 | 96 ± 18 | 88 ± 18 |

| 16 | 10:30:02 - 10:30:52 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.008 | 1.77 ± 0.07 | 64 ± 12 | 85 ± 12 | |

| 17 | 10:35:27 - 10:36:03 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.006 | 1.93 ± 0.05 | 92 ± 16 | 102 ± 16 | |

| 18 | 10:45:01 - 10:45:47 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.009 | 1.02 ± 0.08 | 69 ± 21 | 82 ± 19 | |

| 19 | 11:02:07 - 11:02:56 | 10 | 0.091 ± 0.007 | 0.97 ± 0.10 | 299 ± 23 | 86 ± 23 | |

| 20 | 11:09:03 - 11:09:49 | 10 | 0.091 ± 0.008 | 1.02 ± 0.18 | 280 ± 16 | 86 ± 21 |

| Date | Number test | Downwind distance [m] |

Release Rate [g s-1] |

LW Approach [g s-1] |

SW Approach [g s-1] |

LW | SW |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean Absolute Error |

Mean Absolute Error |

||||||

| 15/01/2024 | 1 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.006 | 0.085 ± 0.004 | 0.082 ± 0.002 | 3.6% | 5.2% |

| 2 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.007 | 0.085 ± 0.002 | 0.086 ± 0.003 | 2.1% | 2.3% | |

| 3 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.009 | 0.083 ± 0.002 | 0.090 ± 0.002 | 3.8% | 5.1% | |

| 4 | 10 | 0.091 ± 0.009 | 0.089 ± 0.006 | 0.084 ± 0.004 | 6.0% | 8.4% | |

| 5 | 10 | 0.091 ± 0.008 | 0.090 ± 0.007 | 0.087 ± 0.004 | 5.5% | 5.3% | |

| 6 | 20 | 0.078 ± 0.007 | 0.077 ± 0.012 | 0.077 ± 0.006 | 6.8% | 5.4% | |

| 7 | 20 | 0.078 ± 0.006 | 0.076 ± 0.010 | 0.096 ± 0.007 | 10.3% | 23.2% | |

| 16/01/2024 | 8 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.007 | 0.082 ± 0.002 | 0.082 ± 0.003 | 4.5% | 4.6% |

| 9 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.009 | 0.083 ± 0.002 | 0.118 ± 0.004 | 3.6% | 36.9% | |

| 10 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.007 | 0.085 ± 0.003 | 0.104 ± 0.003 | 1.9% | 20.8% | |

| 11 | 10 | 0.091 ± 0.008 | 0.090 ± 0.004 | 0.084 ± 0.004 | 3.2% | 8.0% | |

| 12 | 10 | 0.091 ± 0.007 | 0.089 ± 0.007 | 0.084 ± 0.005 | 4.0% | 8.0% | |

| 13 | 20 | 0.078 ± 0.007 | 0.072 ± 0.005 | 0.100 ± 0.006 | 8.9% | 28.4% | |

| 14 | 20 | 0.078 ± 0.007 | 0.077 ± 0.002 | 0.107 ± 0.008 | 5.5% | 37.8% | |

| 17/01/2024 | 15 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.008 | 0.083 ± 0.002 | 0.071 ± 0.002 | 3.6% | 17.4% |

| 16 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.008 | 0.083 ± 0.001 | 0.084 ± 0.002 | 3.5% | 2.4% | |

| 17 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.006 | 0.082 ± 0.002 | 0.082 ± 0.003 | 4.5% | 4.4% | |

| 18 | 1 | 0.086 ± 0.009 | 0.081 ± 0.003 | 0.085 ± 0.004 | 5.4% | 3.8% | |

| 19 | 10 | 0.091 ± 0.007 | 0.087 ± 0.005 | 0.090 ± 0.006 | 5.8% | 5.8% | |

| 20 | 10 | 0.091 ± 0.008 | 0.089 ± 0.004 | 0.092 ± 0.008 | 4.1% | 6.7% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).