1. Introduction

Patellofemoral pain (PFP) is one of the most common, yet difficult, knee problems to manage. While the exact number of individuals with PFP is unknown, estimates have ranged from 25% to as high as 45% of knee pain complaints [

1,

2]. Researchers believe that PFP may be a precursor to knee osteoarthritis (OA) [

3,

4,

5]. PFP and knee OA have similar features and females are more likely than males to develop each pathology [

2,

6]. More concerning is the negative effect that PFP and knee OA can have on function, quality of life, physical activity, and mental health [

7,

8,

9,

10,

11].

PFP is a diagnosis made primarily from self-reported pain either around or behind the patella during activities that require loading on a flexed knee (e.g., running, jumping, stair ambulation, and squatting). More challenging is that radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) provide little, if any, information regarding degenerative cartilage changes [

12,

13]. Poole et al. [

14] have stated that degenerative changes may not become evident for over 20 years.

Detecting knee degenerative changes typically has focused on anatomic derangements and not the underlying molecular pathogenesis [

15]. Furthermore, pain and anatomic changes are not necessarily associated, especially early in the disease process [

16,

17]. Understanding the molecular causes may help identify early patellofemoral joint degeneration and support early intervention. Lotz et al. [

18] have emphasized the importance of biomarkers in preventing and managing knee OA. We believe that biomarkers may provide important information regarding PFP as well.

To date, only 2 studies have examined cartilage degradation biomarkers in individuals with PFP. Murphy et al. [

19] reported increased levels of serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein, a biomarker indicative of cartilage degradation, in subjects with (

n = 18) and without (

n = 14) chondromalacia patella (another term used to describe PFP). However, Bolgla et al. [

20] found no differences in C-telopeptide fragments of type II collagen (CTX-II) between females with (

n = 18) and without (

n = 12) PFP. Limitations existed with both studies. First, they used a single biomarker that may not be robust enough to characterize PFP pathophysiology [

21,

22]. Second, these works were cross-sectional and did not examine changes in biomarker levels over time in those with PFP. Finally, while these works examined pain levels, they did not include any reliable, validated patient-reported outcome measures related to function and quality of life.

The purpose of this study was two-fold. The first purpose was to compare a cluster of biomarkers between females with and without PFP. The second purpose was to determine changes in the biomarker levels, pain, and function/quality of life in females with PFP over a 6-month period. We hypothesized the following: 1) females with PFP would have significantly higher biomarker levels than controls and 2) females with PFP would continue to have elevated biomarkers levels, pain levels, and lower function/quality of life at 6 months.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Subjects

An a priori power analysis was calculated using G*Power (v3.1.9.7) [

23]. Based on a large effect size (d = 0.80), α = 0.05 and β = 0.20, the analysis suggested a minimum of 26 subjects needed to obtain statistical power. Subjects were recruited from the greater Augusta, GA area via word-of mouth and recruitment flyers. Only females were recruited due to naturally occurring sex differences in the biomarkers [

24]. Thirty females with PFP and 30 controls participated. Subjects’ age ranged from 18 to 33 years since the incidence of knee OA is most likely to occur after 40 years [

25]. Inclusion and exclusion criteria have been described before [

26]. Briefly, subjects were recreationally active, defined as exercising at least 30 minutes 3 times a week for at least the past 6 months. Subjects with PFP met additional criteria regarding their anterior knee pain: a) rated at least a 3 on a 10-cm visual analog scale (VAS) during activities of daily living or recreation (e.g., running, walking, squatting, stair ambulation) over the previous week, b) insidious onset for at least 4 weeks, c) provoked by at least 3 of the following: during or after activity, prolonged sitting, stair ambulation, or squatting. None of the subjects with PFP had sought rehabilitation either before or during any time of the study. Individuals with the following were excluded from study participation: a) previous lower extremity surgery or significant injury, b) recurrent patella dislocation or subluxation, c) patella tendon or iliotibial band tenderness, and d) hip or lumbar spine referred pain. The most painful knee was tested for subjects with PFP [

26]; controls used the limb that was determined in a random fashion. Five subjects with PFP reported bilateral symptoms. Subjects were enrolled consecutively as they met the inclusion criteria and signed an informed consent document approved by the Augusta University Institutional Review Board (1480126). All aspects of the study were conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

To ensure that subjects did not have any evident joint degenerative changes to the patellofemoral joint, they received an x-ray (sagittal plane and sunrise views) prior to data collection. The experienced orthopaedic surgeon (D.M.H.) was blinded to each subject’s group assignment and interpreted all images. No subject showed signs of knee (tibiofemoral) or patellofemoral joint degradation.

2.2. Cartilage Biomarker Sample Collection

Based on prior works, we assessed a cluster of cartilage biomarkers [

21]. CTX-II, a cartilage degradation biomarker, has been known to be elevated in individuals with radiographically-defined knee OA [

21,

27]. More importantly, CTX-II levels can decrease with rehabilitation [

28,

29]. The other biomarker, C-propeptide II (CP-II), is a type II synthesis cartilage biomarker shown to be higher in those without knee OA [

21].

2.2.1. Urine Analysis

Subjects with and without PFP provided an early morning, second void urine sample, which was processed and stored at -80˚ C until the time for analysis [

28]. All data were deidentified and analyzed in duplicate using a commercially available enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) based on a mouse monoclonal antibody raised against the EKGPDP sequence of human CTX-II (Urine CartiLaps

® ELISA (CTX-II); BioVendor, LLC; Asheville, NC, USA). CTX-II was corrected for urinary creatinine concentration using the following formula per manufacturer’s instruction: corrected CTX-II (ng/mmol) = [1000 X Urine CartiLaps (ng/ml)]/ creatinine (mmol/L). Subjects with PFP returned to the laboratory for repeat measures 6 months later.

2.2.2. Serum Analysis

Blood samples were collected in serum blood collection tubes and placed in a vertical position for 30 minutes. Afterward, samples were centrifuged in a swinging bucket rotor at room temperature for 20 minutes at 1200 g, in accordance with manufacturer’s instructions. Samples were stored at -80˚ C until the time for analysis. All data were deidentified and analyzed in triplicate using a commercially available ELISA based on a primary rabbit polyclonal antiserum specific for CP-II (CP-II ELISA; IBEX Pharmaceuticals; Montreal, QC, CA). CP-II levels were expressed in ng/L. Subjects with PFP returned to the laboratory for repeat measures 6 months later.

2.2.3. Data Reduction

All CTX-II and CP-II data were log-transformed to minimize the influence of outliers [

28]. The log transformation process converted CTX-II and CP-II to unitless measures. The biomarkers were expressed as a ratio by dividing CTX-II by CP-II (CTX-II:CP-II) [

21]. A higher value suggested greater cartilage degradation than cartilage synthesis.

2.3. Pain and Function/Quality of Life

2.3.1. Pain Measures

Subjects with PFP used a 10-cm VAS to rate their pain during activity over the previous week. Pain during activity over the previous week was used due to its established reliability, responsiveness, and validity for those with PFP [

30]. The extreme left side of the VAS represented “no pain” and the extreme right side represented “worst pain imaginable.” Subjects drew a perpendicular line on the VAS to show the position that best described pain during activity over the previous week. The distance from the extreme left side of the VAS to the perpendicular line drawn by the subject was measured to the nearest 1/10th of a cm and used for statistical analysis. Subjects with PFP returned to the laboratory for repeat measures 6 months later.

2.3.2. Function/Quality of Life Measures

Subjects with PFP completed the Knee injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Scores-Patellofemoral (KOOS-PF) subscale at baseline and 6 months. The KOOS-PF is an 11-item patient-reported outcome measure designed to assess function and quality of life in individuals with PFP [

31]. Hoglund et al. [

32,

33] recommend using the KOOS-PF for clinical and research purposes based on its established content validity, reliability, and responsiveness. The KOOS-PF is scored on a 0-100 scale. A higher value suggests greater function and quality of life. The minimal important change (MIC) for the KOOS-PF is 14.2 points [

31]. Subjects with PFP returned to the laboratory for repeat measures 6 months later.

2.4. Statistical Analysis

Means and standards deviations were calculated for all dependent measures. An independent t-test was used to compare CTX-II:CP-II levels in females with and without PFP at baseline. A separate independent t-test was used to compare the 6-month CTX-II:CP-II levels in females with PFP to control levels collected at baseline. Paired t-tests were used to compare baseline and 6-month CTX-II:CP-II, VAS, and KOOS-PF values for females with PFP. The level of significance was at the 0.05 level. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA).

3. Results

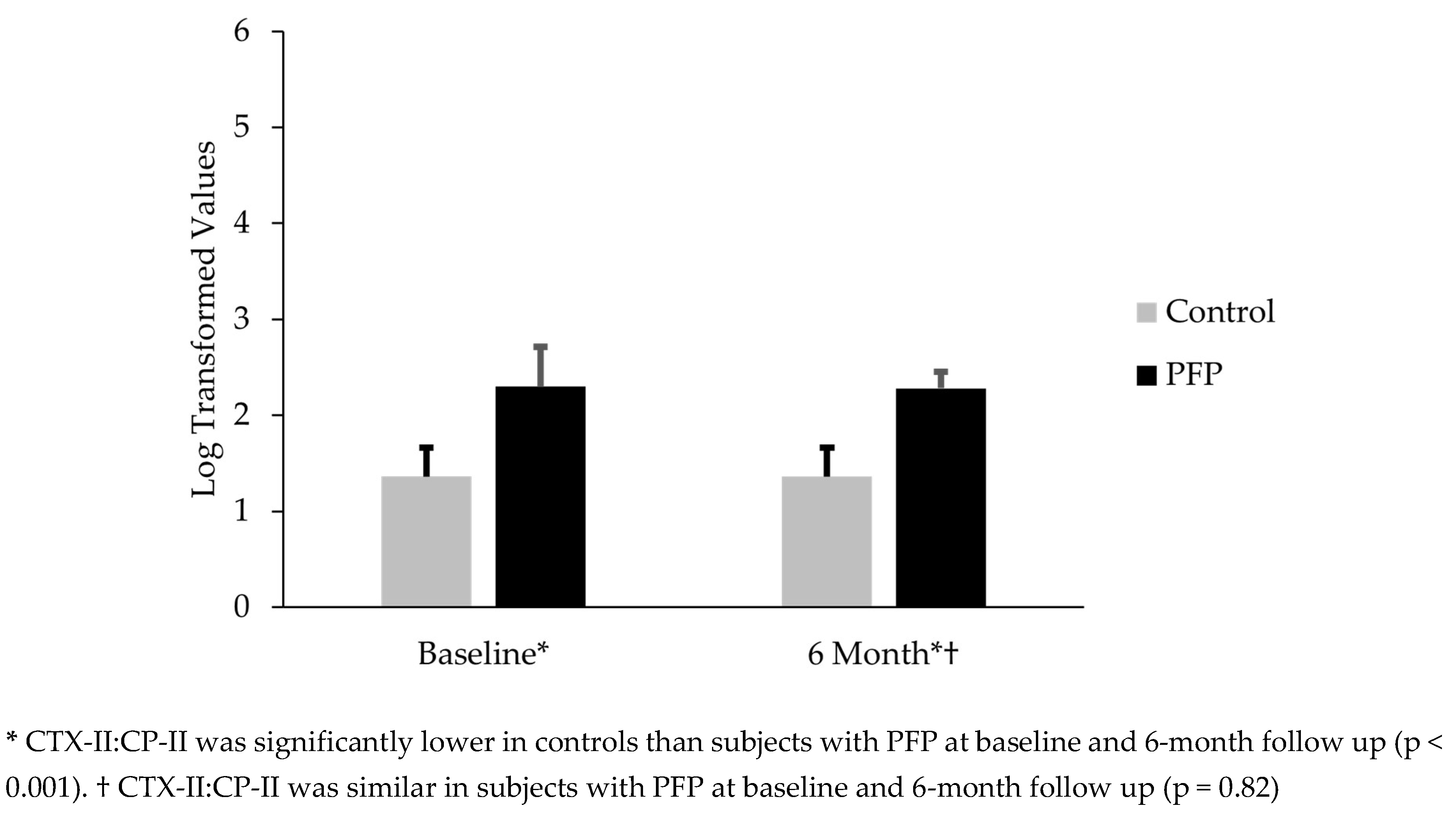

3.1. Comparison of CTX-II:CP-II in Females with PFP and Controls

Thirty females with PFP and 30 controls participated; subjects were similar with respect to age, mass, and height (

Table 1). Females with PFP had CTX-II:CP-II levels that were 69.1% greater than controls (mean difference = 0.94; t(58) = 10.1; p < 0.001) (

Figure 1). The CTX-II:CP-II values for subjects with PFP at 6 months were 67.6% higher than the control’s baseline levels (mean difference 0.92; t(58) = 14.6; p < 0.001) (

Figure 1).

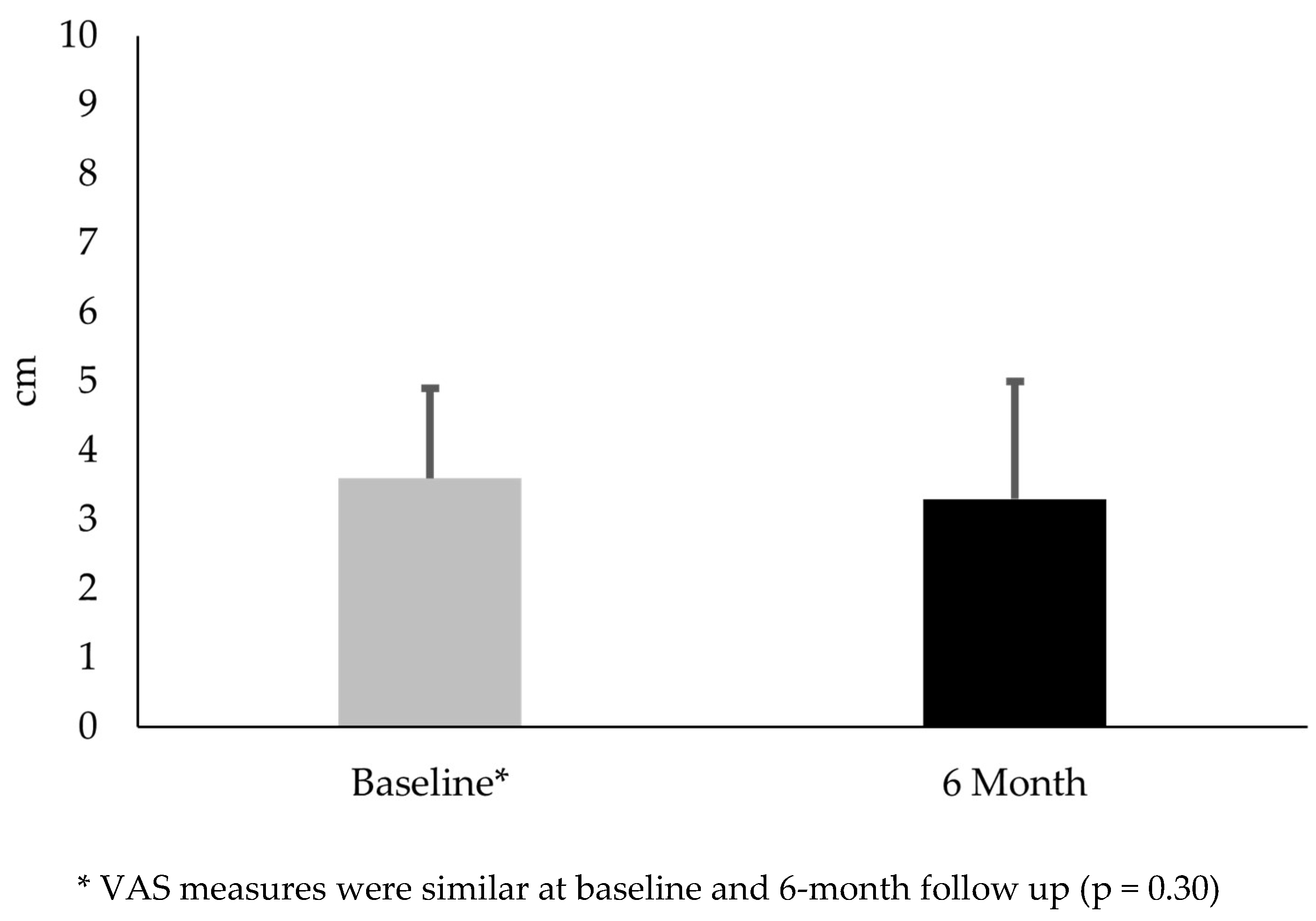

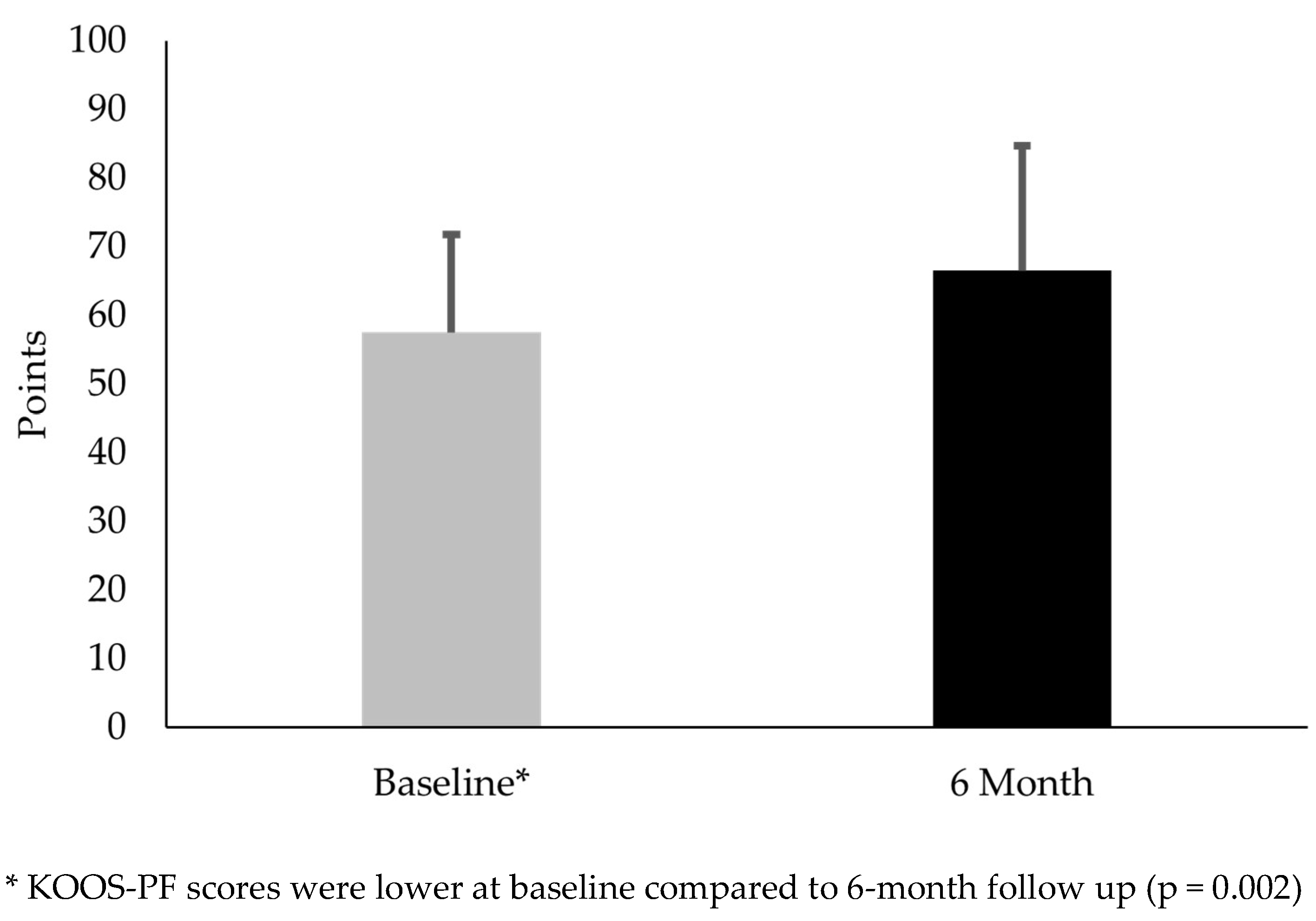

3.2. Comparison of CTX-II:CP-II, VAS, and KOOS-PF in Females with PFP at Baseline and 6-Month Follow Up

Thirty females with PFP participated in this part of the study. No difference existed between CTX-II:CP-II from baseline to the 6-month follow up (mean difference -0.02; t(29) = .23; p = 0.82) (

Figure 1). No difference existed in VAS from baseline to the 6-month follow up (mean difference -0.38; t(29) = 1.1; p = 0.30) (

Figure 2). KOOS-PF scores were 15.7% higher at 6 months than baseline (mean difference 9.0; t(29) = 3.36; p = 0.002) (

Figure 3).

4. Discussion

PFP is a common knee problem believed to be a risk factor for the development of knee OA. A challenge is that PFP is diagnosed based on subjective signs and symptoms and imaging provides limited information. Cartilage biomarkers may provide important insight because they may detect biological changes prior to structural changes being evident with imaging [

15]. The current study is the first to examine a cluster of degenerative cartilage biomarkers in females with and without PFP.

4.1. Comparison of CTX-II:CP-II Between Females With and Without PFP at Baseline

Our results supported the first hypothesis as females with PFP had significantly higher CTX-II:CP-II levels than controls. This finding was clinically important because it contributes to the current body of knowledge that PFP may contribute to knee OA onset [

4]. Understanding possible degenerative changes has been challenging given the limited usefulness of imaging [

12,

13]. Moreover, degenerative changes can have a lengthy latency period and not be evident for over 20 years following PFP onset [

14].

Cibere et al. [

21] examined 10 biomarkers in 201 individuals with knee pain. They found that individuals with radiographically defined knee OA were 3.4 times more likely to have elevated levels of CTX-II:CP-II than those with pain but no degenerative changes. Notably, all subjects in the current study had radiographs that showed no signs of degenerative changes; yet those with PFP had elevated CTX-II:CP-II levels. This finding suggested that CTX-II:CP-II may detect excessive cartilage turnover prior to visible structural changes.

Our pilot work compared CTX-II levels in those with and without PFP and found no between-group differences [

20]. A limitation of this study was the use of a single biomarker to characterize the pathophysiology of a complex knee problem such as PFP. Results from the current study have highlighted the importance of using a cluster of biomarkers to identify differences.

In summary, CTX-II:CP-II may serve as a biomarker that can identify those with PFP who may be at higher risk for developing knee OA. However, additional studies are needed to establish normative values and determine clinically meaningful elevated values across age and sex. Long-term longitudinal studies also are needed to determine changes in CTX-II:CP-II over time in combination with MRI changes.

4.2. Comparison of CTX-II:CP-II, VAS, and Koos-PF Values Between Females with PFP at Baseline and 6 Months

A strength of this study was its prospective nature, allowing the ability to assess natural changes over time without intervention. Most important was that the females with PFP continued with their usual activities. At the end of this period, CTX-II:CP-II levels remained significantly higher than those for controls at baseline. This pattern of persistent biomarker elevation may indicate ongoing abnormal cartilage metabolism that could lead to joint deterioration. Additional longitudinal studies are needed to make this determination.

Regarding the clinical measures, females with PFP had similar VAS scores at 6 months. This finding suggested that symptoms associated with PFP remained relatively stable. Interestingly, these subjects had an average 9.0-point increase in the KOOS-PF. While this change was statistically significant, it did not exceed the MIC. The MIC, the minimal amount of change deemed meaningful to a patient, highlighted an important distinction between statistical significance and clinical meaningfulness [

34]. In other words, an increase from a statistical standpoint did not necessarily translate into a meaningful difference in function and quality of life from the subjects’ perspective. The increased KOOS-PF scores suggested that females with PFP experienced subtle increases in function without any changes in cartilage degradation biomarker levels and pain.

4.3. Clinical Implications

Our findings are clinically important because they provide additional evidence that PFP is not a benign condition but one of ongoing pathology. They suggest that females with PFP and elevated biomarkers may have experienced early biological changes that could lead to patellofemoral joint degradation. This pattern highlights the importance of early detection and additional information regarding prognosis. For example, examining CTX-II:CP-II levels with other clinical measures like lower extremity kinematics, strength, and flexibility may help identify females with PFP who may be at a higher risk for a poor outcome. Identifying this cohort in a timely manner could lead to early rehabilitation that can reduce CTX-II levels [

28,

29].

4.4. Limitations

This study has limitations that deserve consideration. While a strength of this study was a “wait-and-see” period, this duration most likely was not sufficient to detect subtle changes. We purposefully only included females due to naturally occurring differences in biomarker levels, precluding the ability to generalize findings to males with PFP. Although cartilage biomarkers are useful for monitoring disease progression, they are only indirect measures. Longitudinal studies are needed to simultaneously examine biomarker and structural (via MRI) changes over time. Finally, we limited our age range to young adults, and it is unknown if other age ranges, especially adolescents, have elevated CTX-II:CP-II levels.

5. Conclusions

This study was unique because it was the first to examine a cluster of cartilage degradation biomarkers in females with PFP. Study findings show that females with PFP have elevated CTX-II:CP-II levels than controls and remain elevated at 6 months. Our results have added to current evidence suggesting a link between PFP and knee OA onset. This information also highlighted the possible use of this biomarker for prognostic purposes. Future works are needed to determine the long-term effects that elevated CTX-II:CP-II levels have on joint health and if levels reduce with rehabilitation.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A.B.; methodology, L.A.B., T. V. C-M.; formal analysis, L.A.B., T. V. C-M.; investigation, L.A.B., T. V. C-M., M.G., M.O., B.B., J.C., and D.M.H.; resources, L.A.B.; data curation, L.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.A.B., T. V. C-M., M.G., M.O., B.B, J.C; writing—review and editing, L.A.B., T. V. C-M., M.G., M.O., B.B., J.C., and D.M.H.; funding acquisition, L.A.B., T. V. C-M., D.M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15AG063105. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Augusta University (1480126).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the subjects to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Rothermich, M.A.; Glaviano, N.R.; Li, J.; Hart, J.M. Patellofemoral pain: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment options. Clin Sports Med 2015, 34, 313–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Willy, R.W.; Hoglund, L.T.; Barton, C.J.; Bolgla, L.A.; Scalzitti, D.A.; Logerstedt, D.S.; Lynch, A.D.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; McDonough, C.M. Patellofemoral pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2019, 49, CPG1–CPG95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Crossley, K.M.; van Middelkoop, M.; Barton, C.J.; Culvenor, A.G. Rethinking patellofemoral pain: Prevention, management and long-term consequences. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2019, 33, 48–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eijkenboom, J.F.A.; Waarsing, J.H.; Oei, E.H.G.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; van Middelkoop, M. Is patellofemoral pain a precursor to osteoarthritis?: Patellofemoral osteoarthritis and patellofemoral pain patients share aberrant patellar shape compared with healthy controls. Bone Joint Res 2018, 7, 541–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.J.; Oei, E.H.G.; de Kanter, J.L.; Vicenzino, B.; Crossley, K.M. Prevalence of radiographic and magnetic resonance imaging features of patellofemoral osteoarthritis in young and middle-aged adults with persistent patellofemoral pain. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019, 71, 1068–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferre, I.M.; Roof, M.A.; Anoushiravani, A.A.; Wasterlain, A.S.; Lajam, C.M. Understanding the observed sex discrepancy in the prevalence of osteoarthritis. JBJS Rev 2019, 7, e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitaloni, M.; Botto-van Bemden, A.; Sciortino Contreras, R.M.; Scotton, D.; Bibas, M.; Quintero, M.; Monfort, J.; Carné, X.; de Abajo, F.; Oswald, E.; et al. Global management of patients with knee osteoarthritis begins with quality of life assessment: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019, 20, 493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pazzinatto, M.F.; Silva, D.O.; Willy, R.W.; Azevedo, F.M.; Barton, C.J. Fear of movement and (re)injury is associated with condition specific outcomes and health-related quality of life in women with patellofemoral pain. Physiother Theory Pract 2022, 38, 1254–1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glaviano, N.R.; Holden, S.; Bazett-Jones, D.M.; Singe, S.M.; Rathleff, M.S. Living well (or not) with patellofemoral pain: a qualitative study. Phys Ther Sport 2022, 56, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maclachlan, L.R.; Collins, N.J.; Hodges, P.W.; Vicenzino, B. Psychological and pain profiles in persons with patellofemoral pain as the primary symptom. Eur J Pain 2020, 24, 1182–1196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GBD 2021 Osteoarthritis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990-2020 and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol 2023, 5, e508–e522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heijden, R.A.; de Kanter, J.L.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.; Verhaar, J.A.; van Veldhoven, P.L.; Krestin, G.P.; Oei, E.H.; van Middelkoop, M. Structural abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging in patients with patellofemoral pain: a cross-sectional case-control study. Am J Sports Med 2016, 44, 2339–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van der Heijden, R.A.; Oei, E.H.; Bron, E.E.; van Tiel, J.; van Veldhoven, P.L.; Klein, S.; Verhaar, J.A.; Krestin, G.P.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.; van Middelkoop, M. No difference on quantitative magnetic resonance imaging in patellofemoral cartilage composition between patients with patellofemoral pain and healthy controls. Am J Sports Med 2016, 44, 1172–1178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poole, A.R. Can serum biomarker assays measure the progression of cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum 2002, 46, 2549–2552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraus, V.B.; Karsdal, M.A. Clinical monitoring in osteoarthritis: biomarkers. Osteoarthr Cartil 2022, 30, 1159–1173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bedson, J.; Croft, P.R. The discordance between clinical and radiographic knee osteoarthritis: a systematic search and summary of the literature. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2008, 9, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Middelkoop, M.; Macri, E.M.; Eijkenboom, J.F.; van der Heijden, R.A.; Crossley, K.M.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; de Kanter, J.L.; Oei, E.H.; Collins, N.J. Are patellofemoral joint alignment and shape associated with structural magnetic resonance imaging abnormalities and symptoms among people with patellofemoral pain? Am J Sports Med 2018, 46, 3217–3226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lotz, M.; Martel-Pelletier, J.; Christiansen, C.; Brandi, M.L.; Bruyere, O.; Chapurlat, R.; Collette, J.; Cooper, C.; Giacovelli, G.; Kanis, J.A.; et al. Value of biomarkers in osteoarthritis: current status and perspectives. Ann Rheum Dis 2013, 72, 1756–1763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; FitzGerald, O.; Saxne, T.; Bresnihan, B. Increased serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein levels and decreased patellar bone mineral density in patients with chondromalacia patellae. Ann Rheum Dis 2002, 61, 981–985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolgla, L.A.; Gordon, R.; Sloan, G.; Pretlow, L.G.; Lyon, M.; Fulzele, S. Comparison of patella alignment and cartilage biomarkers in young adult females with and without patellofemoral pain: a pilot study. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2019, 14, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibere, J.; Zhang, H.; Garnero, P.; Poole, A.R.; Lobanok, T.; Saxne, T.; Kraus, V.B.; Way, A.; Thorne, A.; Wong, H.; et al. Association of biomarkers with pre-radiographically defined and radiographically defined knee osteoarthritis in a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 2009, 60, 1372–1380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, F.M. Biomarkers: in combination they may do better. Arthritis Res Ther 2009, 11, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.G.; Buchner, A. G*Power 3: a flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav Res Methods 2007, 39, 175–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mouritzen, U.; Christgau, S.; Lehmann, H.J.; Tankó, L.B.; Christiansen, C. Cartilage turnover assessed with a newly developed assay measuring collagen type II degradation products: influence of age, sex, menopause, hormone replacement therapy, and body mass index. Ann Rheum Dis 2003, 62, 332–336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 29-30, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferber, R.; Bolgla, L.; Earl-Boehm, J.E.; Emery, C.; Hamstra-Wright, K. Strengthening of the hip and core versus knee muscles for the treatment of patellofemoral pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Athl Train 2015, 50, 366–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arunrukthavon, P.; Heebthamai, D.; Benchasiriluck, P.; Chaluay, S.; Chotanaphuti, T.; Khuangsirikul, S. Can urinary CTX-II be a biomarker for knee osteoarthritis? Arthroplasty 2020, 2, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chmielewski, T.L.; Trumble, T.N.; Joseph, A.M.; Shuster, J.; Indelicato, P.A.; Moser, M.W.; Cicuttini, F.M.; Leeuwenburgh, C. Urinary CTX-II concentrations are elevated and associated with knee pain and function in subjects with ACL reconstruction. Osteoarthr Cartil 2012, 20, 1294–1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotterud, J.H.; Reinholt, F.P.; Beckstrom, K.J.; Risberg, M.A.; Aroen, A. Relationship between CTX-II and patient characteristics, patient-reported outcome, muscle strength, and rehabilitation in patients with a focal cartilage lesion of the knee: a prospective exploratory cohort study of 48 patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2014, 15, 99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, K.M.; Bennell, K.L.; Cowan, S.M.; Green, S. Analysis of outcome measures for persons with patellofemoral pain: Which are reliable and valid? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004, 85, 815–822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crossley, K.M.; Macri, E.M.; Cowan, S.M.; Collins, N.J.; Roos, E.M. The patellofemoral pain and osteoarthritis subscale of the KOOS (KOOS-PF): development and validation using the COSMIN checklist. Br J Sports Med 2018, 52, 1130–1136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoglund, L.T.; Scalzitti, D.A.; Bolgla, L.A.; Jayaseelan, D.J.; Wainwright, S.F. Patient-reported outcome measures for adults and adolescents with patellofemoral pain: a systematic review of content validity and feasibility using the COSMIN methodology. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2023, 53, 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoglund, L.T.; Scalzitti, D.A.; Jayaseelan, D.J.; Bolgla, L.A.; Wainwright, S.F. Patient-reported outcome measures for adults and adolescents With patellofemoral pain: a systematic review of construct validity, reliability, responsiveness, and interpretability using the COSMIN methodology. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2023, 53, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McGlothlin, A.E.; Lewis, R.J. Minimal clinically important difference: defining what really matters to patients. JAMA 2014, 312, 1342–1343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).