1. Introduction

The 2023 Global Burden of Disease Study estimated that 595 million people globally experience osteoarthritis (OA) and projected that close to 1 billion people will have some form of OA by 2050 [

1]. This group also reported that over half of the cases may occur at the knee. The results of this study align with others that reported a higher incidence of knee OA in females than males [

2,

3]. Unfortunately, researchers have found that knee OA can adversely affect function and quality of life [

4,

5,

6].

Patellofemoral pain (PFP) is a common, chronic knee condition [

7]. While the exact number of those with PFP is unknown [

8], PFP has been reported in at least 25% of knee pain complaints [

7], with some estimates as high as 45% [

9]. A concern is that PFP may contribute to knee OA [

10,

11,

12,

13]. Like knee OA, more females experience PFP in higher numbers than males [

7]. Ongoing pain leads to reduced physical activity levels, anxiety, kinesiophobia, and catastrophizing, all of which negatively affect quality of life in females with PFP [

5,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19]. This pattern underscores the need to understand the pathophysiology of PFP.

PFP is multifactor problem thought to result from a loss of tissue homeostasis from excessive patellofemoral joint (PFJ) loading [

20]. Excessive loading can result from various interactions between the patella and femur. Increased patella lateralization (based on a static, nonweight bearing measure) may increase lateral PFJ loading by directing ground reaction forces to the lateral patellar facet [

21,

22]. Increased lateral (valgus) PFJ loading can result from altered lower extremity kinematics, like increased hip adduction, hip internal rotation, and knee valgus during weight bearing tasks [

23,

24,

25].

PFP is diagnosed based on common impairments such as pain during activities that require the loading on a flexed knee (e.g., running, squatting, kneeling, and stair ambulation) [

7]. Many patients undergo imaging that provides limited, if any, information. Prior works have reported that degenerative changes likely are not evident on radiographs for 20 or more years after onset [

26,

27]. Furthermore, van der Heijden et al [

28,

29] reported no association between PFP and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) features and no differences in cartilage loss in young adults with and without PFP. These findings highlight the need for other ways to detect degenerative changes before they become evident on imaging.

Recent advances in biomarker research have identified matrix metalloproteinase-9 (MMP-9) as a potential indicator of cartilage degradation and inflammation in individuals with OA [

30]. MMP-9, an enzyme upregulated by inflammatory cytokines, is elevated in individuals with OA [

30,

31]. Specifically, MMP-9 leads to OA by breaking down the extracellular matrix that includes collagen. To date, researchers have not examined the presence of inflammatory biomarkers in individuals with PFP. Because PFP is a chronic condition that may lead to knee OA, it is plausible that MMP-9 may be elevated in this patient population. Understanding the role of MMP-9 may lead to improved therapeutic strategies for treating PFP as a potential way to slow and/or prevent degenerative changes associated with OA.

The primary purpose of this study was to compare MMP-9 in females with and without PFP. The secondary purpose was to determine if patella position, lower extremity kinematics during a single-leg squat (SLS), and/or pain were associated with MMP-9 in a subset of females with PFP. We hypothesized that females with PFP would have significantly greater MMP-9 levels than controls. We also hypothesized that a positive association would exist between MMP-9 levels and a) static patella position, b) hip and knee kinematics during a SLS, and c) pain in females with PFP.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Research Design

An observational, cohort design was used for this investigation. To test the hypothesis for the investigation’s primary aim, all subjects provided a blood sample. To test the hypothesis for the investigation’s secondary aim, only data from a subset of subjects with PFP and a complete data set were used.

2.2. Subjects

Subjects were recruited in the greater Central Savannah River Area by placing flyers on 2 campuses of a local university, at area fitness clubs, and at an academic medical center sports medicine clinic. Only females participated since they are more likely to experience PFP and because of the possibility of naturally occurring sex differences in MMP-9 levels [

32,

33,

34]. Thirty-nine females with PFP and 30 controls participated (

Table 1). The subjects’ age ranged from 18 to 34 years. This age range was selected because of an increased prevalence of OA onset after age 40 [

35]. Inclusion and exclusion criteria were based on prior works [

33,

36]. All subjects were recreationally active, defined as exercising at least 30 minutes 3 times a week for at least the past 6 months. Subjects with PFP met additional criteria regarding their anterior knee pain: a) rated at least a 3 on a 10-cm visual analog scale (VAS) during activities of daily living or recreation (e.g., running, walking, squatting, stair ambulation) over the previous week, b) insidious onset for at least 4 weeks, c) provoked by at least 3 of the following: during or after activity, prolonged sitting, stair ambulation, or squatting. None of the subjects with PFP had sought rehabilitation or undergone any prior movement retraining program to improve SLS mechanics. Individuals with the following were excluded from study participation: a) previous lower extremity surgery or significant injury, b) recurrent patella dislocation or subluxation, c) patella tendon or iliotibial band tenderness, and d) hip or lumbar spine referred pain. The most painful knee was tested for subjects with PFP [

33]; controls used the limb that was determined in a random fashion. Five subjects with PFP reported bilateral symptoms. Subjects were enrolled consecutively as they met the inclusion criteria and signed an informed consent document approved by the Augusta University Institutional Review Board.

Prior to data collection, all subjects received an x-ray (sagittal plane and sunrise views) to ensure that none had evidence of degenerative changes to the PFJ. The experienced orthopaedic surgeon (D.M.H.), blind to subject group, interpreted all images. No subject showed signs of degradation to the PFJ. Subjects with PFP also completed a 10-cm VAS to report their usual amount of pain during activity for the prior week [

37]. Measures were recorded to the nearest 1/10

th of a cm.

2.3. Plasma Collection and Measurement of MMP-9 Levels

Blood samples were collected in a plasma blood collection tube. Next, samples were centrifuged in a swinging bucket rotor at room temperature for 20 minutes at 1200 rpm. Afterward, plasma was aliquoted into cryovials and stored at -80˚ C until processed.

Plasma levels of MMP-9 were measured using sandwich immuno-assay on an automated enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (ELISA) (ELLA, Biotechne, MN, USA). The plasma (35ul) was diluted by adding assay buffer (35ul) and 50ul of the diluted plasma was added to the ELLA plate along with other reagents, as recommended by the manufacturer. The plate was then loaded into the automated ELISA for processing. The plasma MMP-9 levels were then downloaded, expressed as ng/mL, and used for statistical analysis.

2.4. Static Patella Position

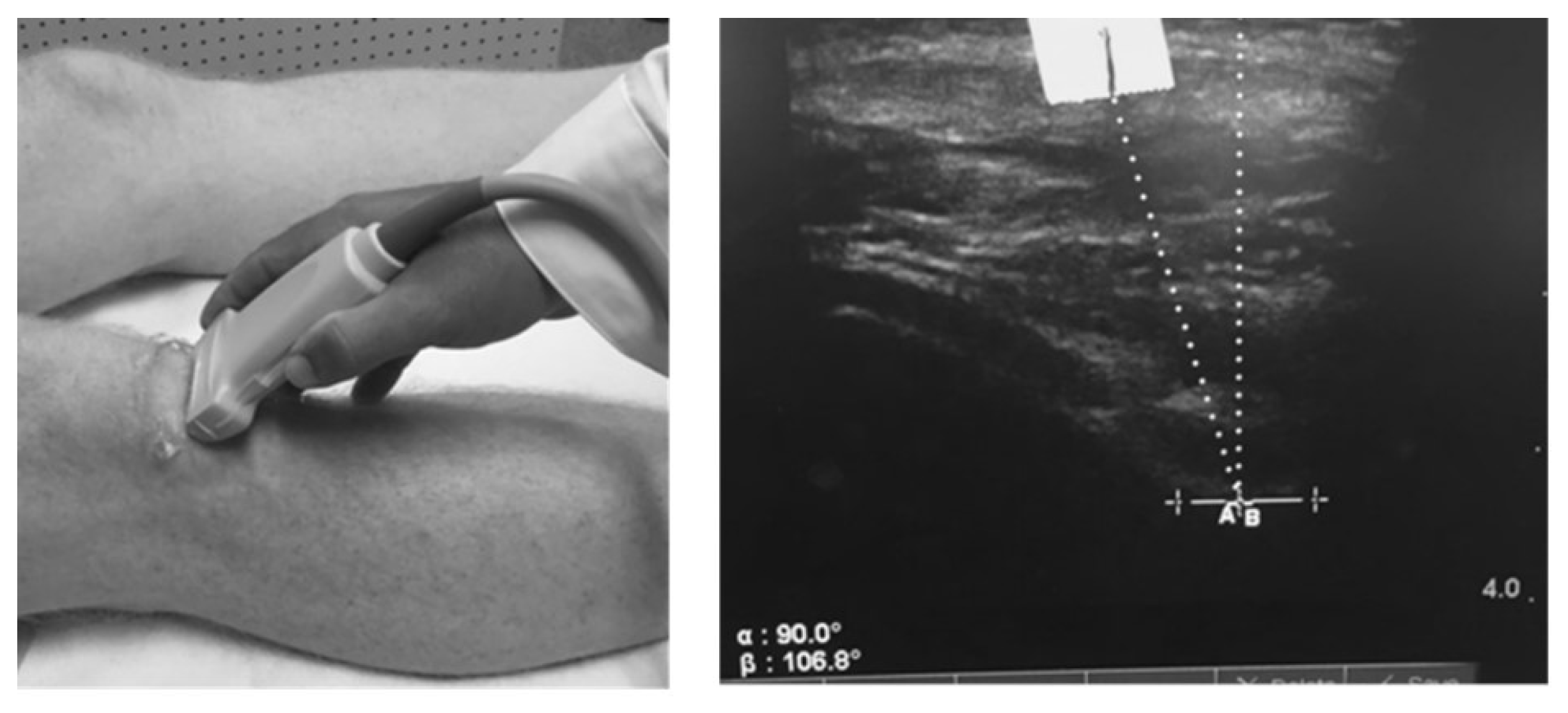

We measured the patella offset angle (RAB angle) using diagnostic ultrasound as described by Anilo et al [

38]. Briefly, Anillo et al developed the RAB angle to quantify patella lateralization or medialization relative to the lowest part of the femoral trochlear groove. The RAB angle was measured as follows: 1) a vertical line perpendicular to the lowest aspect of the femoral trochlea and 2) a line from the lowest aspect of the femoral trochlea to the inferior pole of the patella (

Figure 1). An angle formed with the line from the lowest aspect of the femoral trochlea to the inferior patellar pole directed toward the lateral aspect of the knee represented patella lateralization. For testing, subjects were positioned in supine with the quadriceps relaxed and the lower extremity in a neutral position. One examiner (D.C.H.) took 2 measures of the test knee. All RAB angles were recorded to the nearest 1/10

th of a degree; the average of 2 measures was used for statistical analysis.

2.5. Hip and Knee Kinematics during a Single Leg Squat

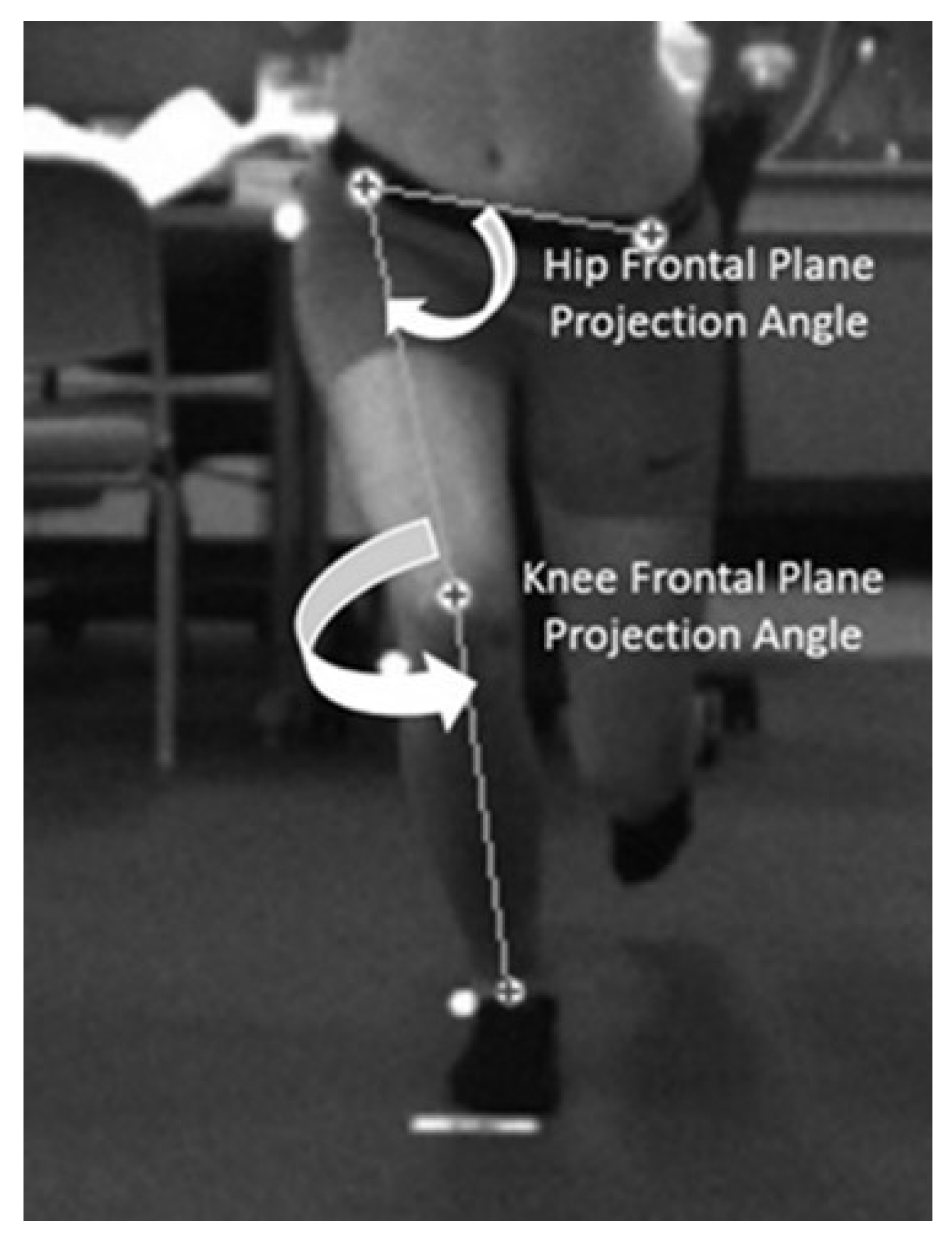

Hip and knee kinematics, collected with a 2-dimensional (2D) motion capture system (Simi Motion®, Unterschleinβheim, DEU), were quantified using the dynamic valgus index (DVI), a combined measure of hip and knee motion [

39]. Twelve-mm spherical retroreflective markers were placed on the anterior surfaces of the following landmarks: left and right anterior superior iliac spine (ASIS), midpoint of the knee on the test extremity, and the midpoint between the medial and lateral malleolus of the ankle on the test extremity. These markers were used to measure the hip and knee frontal plane projection angles (FPPA). Markers also were placed on the greater trochanter, knee joint line, and lateral malleolus to measure knee flexion. For testing, subjects stood 2.5 m away from one camera placed in the frontal plane and another in the sagittal plane. Subjects performed the SLS barefooted. The investigator instructed subjects to cross their arms over their chest and to squat as low as possible; they received no instruction on hip, knee, or foot position. Subjects squatted at least 50˚ of knee flexion (determined by visual inspection) to the beat of a metronome set at 40 beats per minute. They performed 3 practice and 5 test trials of the SLS. The motion capture system, operating at 100 Hz, recorded all data.

A 2

nd-order low-pass filter, using a 6 Hz cutoff frequency, tracked and smoothed all video data. We measured the DVI at the point of peak knee flexion (the angle between the greater trochanter, lateral knee joint line, and lateral malleolus). The knee FPPA (

Figure 2) was 180˚ minus the angle between the ASIS and mid-point of the knee and the mid-point of the knee to the mid-point of the ankle on the test limb [

39]. The DVI (

Figure 2) was 90˚ minus the angle between the ipsilateral and contralateral ASIS and ipsilateral ASIS and the mid-point of the distal femur (hip FPPA) plus the knee FPPA [

39]. All angles were measured to the nearest 1/10

th of a degree. The average of 5 trials for peak DVI was used for statistical analysis.

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Means, standard deviations, and 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for MMP-9 levels for all subjects. The same were calculated for RAB angles, peak DVI, and pain in the subset of subjects with PFP who completed these additional assessments. An independent

t-test was used to compare MMP-9 levels between females with PFP and controls. Pearson product correlation coefficients were used to determine associations between MMP-9, RAB angle, peak DVI, and pain in the subset of subjects with PFP. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28 (IBM Corp, Armonk, NY, USA); the level of significance was established at the 0.05 level. We hypothesized an increase in the measured variables; thus, we used a one-tailed test to maximize statistical power [

40].

3. Results

3.1. Comparison of MMP-9 Levels in Females with PFP and Control

Females with PFP had MMP-9 levels 25.6% higher than controls (t(66.6) = 1.86, p = 0.03). Average MMP-9 values for females with PFP were 72.7 (38.3) ng/mL (95% CI, 60.3 – 85.1) and controls were 58.0 (27.3) ng/mL (95% CI, 47.8 – 68.2).

3.2. Associations between MMP-9 levels, RAB Angle, DVI, and Pain in Females with PFP

Twenty-three subjects with PFP completed this part of the investigation. The average RAB angle was 14.6 (8.7) degrees (95% CI, 10.9 – 18.4), the average DVI 34.5 (11.6) degrees (95% CI, 29.5 – 39.5), and average VAS 4.1 (1.4) cm (95% CI, 3.5 – 4.7). These females demonstrated a signficant, positive association between MMP-9 levels and the RAB angle (r = 0.38, p = 0.04) and a significant, inverse association between MMP-9 levels and the DVI (r = -0.50, p = 0.007). A non-significant association (r = 0.12, p = 0.29) existed between MMP-9 levels and pain.

4. Discussion

PFP is a common, multifactor problem believed to result from PFJ overload either from an altered patella position and/or faulty lower extremity kinematics [

41]. More concerning is that PFP is considered a risk factor for the development of knee OA [

11,

12]. To date, most research directed toward understanding PFP pathology has been directed toward structural approaches (e.g., imaging and biomechanical models). This study’s uniqueness was taking a biological approach by examining MMP-9, an inflammatory biomarker, in young, adult females with PFP and normal knee radiographs.

4.1. Comparison of MMP-9 Levels in Females with PFP and Control

Results from this study supported the primary hypothesis that females with PFP would exhibit significantly higher levels of MMP-9 than controls. This finding has provided preliminary evidence that young, adult females with PFP have elevated inflammatory biomarkers found in individuals with knee OA [

30,

31]. It also has afforded additional evidence that PFP is not necessarily a self-limiting condition but one of ongoing pathology [

12,

42,

43,

44]. Quantifying the degree of pathology has been a challenge with those with PFP, given the lack of useful information gained from radiographs and MRI [

28,

29]. None of the subjects in the current study had degenerative changes on radiographs and aligned with the limited usefulness of imaging. Therefore, MMP-9 may provide insight into degenerative knee changes in those with PFP prior to them becoming evident on imaging. Future studies are needed to make this determination.

To date, only 2 other works have examined biomarkers in those with PFP. Murphy et al [

45] compared serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (s-COMP), a biomarker indicative of cartilage degradation, in 18 individuals with and without chondromalacia patellae (another term used to characterize PFP). Subjects with chondromalacia patellae exhibited greater s-COMP levels compared to controls. Our previous report [

41] analyzed and compared C-telopeptide fragments of type II collagen (CTX-II) in females with and without PFP and found no differences. Both investigations relied on a single biomarker to differentiate between subjects with and without PFP. Cibere et. al [

46] examined biomarkers in those with knee OA and concluded that use of this single biomarker may not have been robust enough to identify “true” degenerative changes . The paucity of available evidence supports the need for future studies aimed at identifying and understanding biomarkers associated with PFP.

4.2. Associations between MMP-9 levels, Pain, RAB Angle, and DVI in Females with PFP

Results from this study partially supported these hypotheses. We hypothesized a positive association between MMP-9 and the RAB angle since increased patellar lateralization is a specific characteristic of PFJ OA [

47]. Study findings (

r = 0.38,

p = 0.04) supported this hypothesis. We also hypothesized a positive association between MMP-9 and the DVI since an increased DVI during a SLS could cause increased valgus loads and irritation to the PFJ [

39]. Although a significant association (

r = -0.50,

p = 0.007) existed, it was an inverse, not positive, one. A possible reason for this finding may have been that subjects with higher MMP-9 levels avoided hip adduction and knee abduction, combined motions leading to knee valgus loads, during the SLS. This finding may suggest that explaining PFP based on a strict movement-based, biomechanical model may not necessarily explain PFP pathology [

48]. Finally, a weak correlation (

r = 0.12,

p = 0.29) existed between MMP-9 and pain.

A possible limitation of analyzing data for the entire cohort of females with PFP who completed the patella position and kinematics procedures may be RAB angle variability. RAB angles ranged from 1.0 to 33.5 degrees. Based on the theory that greater patella lateralization can lead to greater increased PFJ loading, a secondary analysis was conducted. For this purpose, we performed correlation analyses between MMP-9 levels, RAB angle, DVI, and pain in subjects with a high RAB angle (

n = 14), defined as greater than 13 degrees [

38]. Results from this analysis showed stronger associations between MMP-9 levels and the RAB angle (

r = 0.52,

p = 0.03), DVI (

r = -0.78,

p < 0.001), and pain (

r = 0.38,

p = 0.09). Though not significant, the increased association with pain in subjects with greater patellar lateralization has provided preliminary evidence of the influence that patella lateralization could have on PFJ inflammation. Future investigations should further examine this association in subjects with a higher RAB angle.

4.3. Limitations

This study has limitations. First, the study only enrolled females since they are more than 2 times likely to experience PFP than males [

32,

33]. Also, naturally occurring sex differences in MMP-9 levels could exist [

34,

49]. Therefore, we cannot generalize our findings to males with PFP. Another limitation is the use of a biomarker to suggest degenerative changes. While useful to monitor disease progression, biomarkers are only an indirect manner for assessing degenerative changes. However, elevated MMP-9 levels may help clinicians identify females with PFP who may benefit from early rehabilitation [

44]. Finally, this study is cross-sectional, and it is unknown if subjects with PFP will continue to exhibit elevated MMP-9 levels over time. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine the progression of MMP-9 levels, if any, over time.

4.4. Future Direction and Conclusion

A major strength of this investigation is the identification of MMP-9, an inflammatory biomarker associated with knee OA, in a cohort of young, adult females with PFP. This finding highlights possible degenerative changes occurring much sooner than changes becoming evident on imaging. Knowing this information supports the need for early interventions to address impairments associated with PFP. Our results also suggest that MMP-9 could serve as a possible biomarker for diagnostic and prognostic purposes. To definitively determine if MMP-9 is a precursor to knee OA onset, investigators should continue to examine changes in both bone structure and MMP-9 levels over time in young, adult females with PFP.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.A.B.; methodology, L.A.B., S.P., D.C.H.; formal analysis, L.A.B., S.P., D.C.H.; investigation, L.A.B., S.P., D.C.H., D.M.H.; resources, L.A.B.; data curation, L.A.B.; writing—original draft preparation, L.A.B., S.P., D.C.H.; writing—review and editing, L.A.B., S.P., D.C.H., D.M.H.; funding acquisition, L.A.B., D.M.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

Research reported in this publication was supported by the National Institute on Aging of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R15AG063105. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Institutional Review Board of Augusta University (1480126).

Informed Consent Statement

Written informed consent has been obtained from the subjects to publish this paper.

Data Availability Statement

Data from this study are available on request to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- GBD 2021 Osteoarthritis Collaborators. Global, regional, and national burden of osteoarthritis, 1990-2020 and projections to 2050: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021. Lancet Rheumatol 2023, 5, e508-e522. [CrossRef]

- Hame, S.L.; Alexander, R.A. Knee osteoarthritis in women. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2013, 6, 182-187. [CrossRef]

- Lawrence, R.C.; Felson, D.T.; Helmick, C.G.; Arnold, L.M.; Choi, H.; Deyo, R.A.; Gabriel, S.; Hirsch, R.; Hochberg, M.C.; Hunder, G.G.; et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part II. Arthritis Rheum 2008, 58, 26-35. [CrossRef]

- Vitaloni, M.; Botto-van Bemden, A.; Sciortino Contreras, R.M.; Scotton, D.; Bibas, M.; Quintero, M.; Monfort, J.; Carné, X.; de Abajo, F.; Oswald, E.; et al. Global management of patients with knee osteoarthritis begins with quality of life assessment: a systematic review. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2019, 20, 493. [CrossRef]

- Pazzinatto, M.F.; Silva, D.O.; Willy, R.W.; Azevedo, F.M.; Barton, C.J. Fear of movement and (re)injury is associated with condition specific outcomes and health-related quality of life in women with patellofemoral pain. Physiother Theory Pract 2022, 38, 1254-1263. [CrossRef]

- Glaviano, N.R.; Kew, M.; Hart, J.M.; Saliba, S. Demographic and epidemiological trends in patellofemoral pain. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2015, 10, 281-290, doi: .

- Willy, R.W.; Hoglund, L.T.; Barton, C.J.; Bolgla, L.A.; Scalzitti, D.A.; Logerstedt, D.S.; Lynch, A.D.; Snyder-Mackler, L.; McDonough, C.M. Patellofemoral Pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2019, 49, CPG1-CPG95. [CrossRef]

- Sánchez, M.B.; Selfe, J.; Callaghan, M.J. The prevalence of patellofemoral pain in the Rugby League World Cup (RLWC) 2021 spectators: A protocol of a cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2021, 16, e0260541. [CrossRef]

- Rothermich, M.A.; Glaviano, N.R.; Li, J.; Hart, J.M. Patellofemoral pain: epidemiology, pathophysiology, and treatment options. Clin Sports Med 2015, 34, 313-327. [CrossRef]

- Crossley, K.M.; Callaghan, M.J.; Linschoten, R. Patellofemoral pain. Br J Sports Med 2016, 50, 247-250. [CrossRef]

- Eijkenboom, J.F.A.; Waarsing, J.H.; Oei, E.H.G.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A.; van Middelkoop, M. Is patellofemoral pain a precursor to osteoarthritis?: Patellofemoral osteoarthritis and patellofemoral pain patients share aberrant patellar shape compared with healthy controls. Bone Joint Res 2018, 7, 541-547. [CrossRef]

- Antony, B.; Jones, G.; Jin, X.; Ding, C. Do early life factors affect the development of knee osteoarthritis in later life: a narrative review. Arthritis Res Ther 2016, 18, 202. [CrossRef]

- Brenneis, M.; Junker, M.; Sohn, R.; Braun, S.; Ehnert, M.; Zaucke, F.; Jenei-Lanzl, Z.; Meurer, A. Patellar malalignment correlates with increased pain and increased synovial stress hormone levels-A cross-sectional study. PLoS One 2023, 18, e0289298. [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.E.; Moffatt, F.; Hendrick, P.; Bateman, M.; Rathleff, M.S.; Selfe, J.; Smith, T.O.; Logan, P. The experience of living with patellofemoral pain-loss, confusion and fear-avoidance: a UK qualitative study. BMJ Open 2018, 8, e018624. [CrossRef]

- Maclachlan, L.R.; Collins, N.J.; Hodges, P.W.; Vicenzino, B. Psychological and pain profiles in persons with patellofemoral pain as the primary symptom. Eur J Pain 2020, 24, 1182-1196. [CrossRef]

- Hott, A.; Brox, J.I.; Pripp, A.H.; Juel, N.G.; Liavaag, S. Predictors of pain, function, and change in patellofemoral pain. Am J Sports Med 2020, 48, 351-358. [CrossRef]

- Priore, L.B.; Azevedo, F.M.; Pazzinatto, M.F.; Ferreira, A.S.; Hart, H.F.; Barton, C.; de Oliveira Silva, D. Influence of kinesiophobia and pain catastrophism on objective function in women with patellofemoral pain. Phys Ther Sport 2019, 35, 116-121. [CrossRef]

- Glaviano, N.R.; Baellow, A.; Saliba, S. Physical activity levels in individuals with and without patellofemoral pain. Phys Ther Sport 2017, 27, 12-16. [CrossRef]

- Glaviano, N.R.; Holden, S.; Bazett-Jones, D.M.; Singe, S.M.; Rathleff, M.S. Living well (or not) with patellofemoral pain: a qualitative study. Phys Ther Sport 2022, 56, 1-7. [CrossRef]

- Post, W.R.; Dye, S.F. Patellofemoral pain: an enigma explained by homeostasis and common sense. Am J Orthop 2017, 46, 92-100.

- Kim, Y.M.; Joo, Y.B. Patellofemoral osteoarthritis. Knee Surg Relat Res 2012, 24, 193-200. [CrossRef]

- Wyndow, N.; Collins, N.; Vicenzino, B.; Tucker, K.; Crossley, K. Is there a biomechanical link between patellofemoral pain and osteoarthritis? a narrative review. Sports Med 2016, 46, 1797-1808. [CrossRef]

- Souza, R.B.; Powers, C.M. Differences in hip kinematics, muscle strength, and muscle activation between subjects with and without patellofemoral pain. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 2009, 39, 12-19. [CrossRef]

- Salsich, G.B.; Graci, V.; Maxam, D.E. The effects of movement pattern modification on lower extremity kinematics and pain in women with patellofemoral pain. Journal of Orthopaedic and Sports Physical Therapy 2012, 42, 1017-1024. [CrossRef]

- Powers, C.M. The influence of abnormal hip mechanics on knee injury: a biomechanical perspective. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2010, 40, 42-51. [CrossRef]

- Collins, N.J.; Oei, E.H.G.; de Kanter, J.L.; Vicenzino, B.; Crossley, K.M. Prevalence of radiographic and magnetic resonance imaging features of patellofemoral osteoarthritis in young and middle-aged adults with persistent patellofemoral pain. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2019, 71, 1068-1073. [CrossRef]

- Poole, A.R. Can serum biomarker assays measure the progression of cartilage degeneration in osteoarthritis? Arthritis Rheum 2002, 46, 2549-2552. [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, R.A.; de Kanter, J.L.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.; Verhaar, J.A.; van Veldhoven, P.L.; Krestin, G.P.; Oei, E.H.; van Middelkoop, M. Structural abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging in patients with patellofemoral pain: a cross-sectional case-control study. Am J Sports Med 2016, 44, 2339-2346. [CrossRef]

- van der Heijden, R.A.; Oei, E.H.; Bron, E.E.; van Tiel, J.; van Veldhoven, P.L.; Klein, S.; Verhaar, J.A.; Krestin, G.P.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.; van Middelkoop, M. No difference on quantitative magnetic resonance imaging in patellofemoral cartilage composition between patients with patellofemoral pain and healthy controls. Am J Sports Med 2016, 44, 1172-1178. [CrossRef]

- Slovacek, H.; Khanna, R.; Poredos, P.; Jezovnik, M.; Hoppensteadt, D.; Fareed, J.; Hopkinson, W. Interrelationship of Osteopontin, MMP-9 and ADAMTS4 in Patients With Osteoarthritis Undergoing Total Joint Arthroplasty. Clin Appl Thromb Hemost 2020, 26, 1076029620964864. [CrossRef]

- Zeng, G.Q.; Chen, A.B.; Li, W.; Song, J.H.; Gao, C.Y. High MMP-1, MMP-2, and MMP-9 protein levels in osteoarthritis. Genet Mol Res 2015, 14, 14811-14822. [CrossRef]

- Boling, M.; Padua, D.; Marshall, S.; Guskiewicz, K.; Pyne, S.; Beutler, A. Gender differences in the incidence and prevalence of patellofemoral pain syndrome. Scand J Med Sci Sports 2010, 20, 725-730. [CrossRef]

- Ferber, R.; Bolgla, L.; Earl-Boehm, J.E.; Emery, C.; Hamstra-Wright, K. Strengthening of the hip and core versus knee muscles for the treatment of patellofemoral pain: a multicenter randomized controlled trial. J Athl Train 2015, 50, 366-377. [CrossRef]

- Mouritzen, U.; Christgau, S.; Lehmann, H.J.; Tankó, L.B.; Christiansen, C. Cartilage turnover assessed with a newly developed assay measuring collagen type II degradation products: influence of age, sex, menopause, hormone replacement therapy, and body mass index. Ann Rheum Dis 2003, 62, 332-336. [CrossRef]

- Cui, A.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 29-30, 100587. [CrossRef]

- Gwynne, C.R.; Curran, S.A. Two-dimensional frontal plane projection angle can identify subgroups of patellofemoral pain patients who demonstrate dynamic knee valgus. Clin Biomech 2018, 58, 44-48. [CrossRef]

- Crossley, K.M.; Bennell, K.L.; Cowan, S.M.; Green, S. Analysis of outcome measures for persons with patellofemoral pain: Which are reliable and valid? Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2004, 85, 815-822. [CrossRef]

- Anillo, R.; Villanueva, E.; León, D.; Pena, A. Ultrasound diagnosis for preventing knee injuries in Cuban high-performance athletes. MEDICC Review 2009, 11, 21-28.

- Scholtes, S.A.; Salsich, G.B. A dynamic valgus index that combines hip and knee angles: assessment of utility in females with patellofemoral pain. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2017, 12, 333-340.

- Fleming, K.K.; Bovaird, J.A.; Mosier, M.C.; Emerson, M.R.; LeVine, S.M.; Marquis, J.G. Statistical analysis of data from studies on experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. J Neuroimmunol 2005, 170, 71-84. [CrossRef]

- Bolgla, L.A.; Gordon, R.; Sloan, G.; Pretlow, L.G.; Lyon, M.; Fulzele, S. Comparison of patella alignment and cartilage biomarkers in young adult females with and without patellofemoral pain: a pilot study. Int J Sports Phys Ther 2019, 14, 46-54.

- Crossley, K.M.; van Middelkoop, M.; Barton, C.J.; Culvenor, A.G. Rethinking patellofemoral pain: Prevention, management and long-term consequences. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2019, 33, 48-65. [CrossRef]

- Roemer, F.W.; Kwoh, C.K.; Fujii, T.; Hannon, M.J.; Boudreau, R.M.; Hunter, D.J.; Eckstein, F.; John, M.R.; Guermazi, A. From early radiographic knee osteoarthritis to joint arthroplasty: Determinants of structural progression and symptoms. Arthritis Care Res 2018. [CrossRef]

- Stefanik, J.J.; Guermazi, A.; Roemer, F.W.; Peat, G.; Niu, J.; Segal, N.A.; Lewis, C.E.; Nevitt, M.; Felson, D.T. Changes in patellofemoral and tibiofemoral joint cartilage damage and bone marrow lesions over 7 years: the Multicenter Osteoarthritis Study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016, 24, 1160-1166. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, E.; FitzGerald, O.; Saxne, T.; Bresnihan, B. Increased serum cartilage oligomeric matrix protein levels and decreased patellar bone mineral density in patients with chondromalacia patellae. Ann Rheum Dis 2002, 61, 981-985. [CrossRef]

- Cibere, J.; Zhang, H.; Garnero, P.; Poole, A.R.; Lobanok, T.; Saxne, T.; Kraus, V.B.; Way, A.; Thorne, A.; Wong, H.; et al. Association of biomarkers with pre-radiographically defined and radiographically defined knee osteoarthritis in a population-based study. Arthritis Rheum 2009, 60, 1372-1380. [CrossRef]

- Kalichman, L.; Zhang, Y.; Niu, J.; Goggins, J.; Gale, D.; Felson, D.T.; Hunter, D.J. The association between patellar alignment and patellofemoral joint osteoarthritis features--an MRI study. Rheumatology 2007, 46, 1303-1308. [CrossRef]

- Van Cant, J. Unmasking the Culprit: Reframing Pain in Research and Management of Patellofemoral Pain. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2025, 55, 75-77. [CrossRef]

- Kolhe, R.; Owens, V.; Sharma, A.; Lee, T.J.; Zhi, W.; Ghilzai, U.; Mondal, A.K.; Liu, Y.; Isales, C.M.; Hamrick, M.W.; et al. Sex-specific differences in extracellular vesicle protein cargo in synovial fluid of patients with osteoarthritis. Life (Basel) 2020, 10, 337. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).