1. Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (KOA) is a degenerative joint disease characterized by the gradual breakdown of cartilage in the knee joint. It is the most common type of arthritis, affecting millions worldwide [

1]. The World Health Organization (WHO) assesses that by 2025 the number of elderly population will grow by 414% compared to the year 1990 [

2]. Moreover, estimates suggest that the proportion of people aged 65 and above will reach 16% of the worldwide population [

3]. Thus, this phenomenon leads to an increase in cases of prevalence of KOA [

1]. A study confirmed that KOA in American adults is responsible for 80% of the total osteoarthritis cases and affects about 20% of those over 45 years old [

4]. The data from the third National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES III) highlighted that about 40% of participants aged over 60 had KOA [

5]. This disease has an important impact on affected persons’ quality of life; the progressive and chronic condition and high prevalence also affect the socio-economic status.

Besides old age, obesity can be a trigger or aggravating factor [

6]. Excess weight puts added stress on the knee joints, accelerating cartilage degeneration. Obesity is associated with a weak inflammation stage, and the deterioration of cartilage may be attributed to an imbalance between pro-inflammatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, leading to destructive effects [

7]. Adipose tissue plays a crucial role in the development and progression of KOA through metabolic, biomechanical, and pro-inflammatory factors that trigger illness. It has been recognized as a powerful internal endocrine organ due to its ability to release biologically active adipokines, such as adiponectin (ACRP-30), a 244 amino acid polypeptide that participates in various physiological and pathological processes. The expression of ACRP-30 in serum and adipose tissue is reduced in individuals with obesity [

8]. It represents the majority of adipokines from circulation, being structurally homologous to tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α) [

9]. It has been observed that ACRP-30 manifests the anti-inflammatory potential by downregulating cytokines with pro-inflammatory properties, e.g., TNF-α and interleukin-6 (IL-6), and stimulating the expression of cytokines with anti-inflammatory attributes [

10]. TNF-α seems to have a crucial function in the breakdown of cartilage matrix and KOA. It has the ability to stimulate the generation of matrix metalloproteinases, IL-6, and prostaglandins, while also downregulating the production of type II collagen and proteoglycans [

11]. In the Dutch study, it was observed that the ex vivo level of TNF-α from whole blood samples stimulated with lipopolysaccharide was related to the radiological progression of KOA over 2 years [

12]. IL-10 is another important biomarker, being able to interfere with TNF-α production and other mediated events correlated with osteoarthritis development [

13], hence, indicating the significance of a controlled equilibrium between anti-inflammatory and pro-inflammatory cytokines in maintaining the health of the joints. KOA progression is known to be linked to an elevated production of TNF-α and IL-10 in whole blood, findings suggesting that concentrations of local and circulating cytokines decrease in advanced KOA compared to moderate cases [

14].

Early identification of patients at risk of developing KOA and anticipation or correction of predisposing factors are essential in disease management. Diagnosis is usually based on the patient’s history and clinical features according to the American College of Rheumatology criteria for the diagnosis of KOA [

15]. Nevertheless, in several cases, particularly in patients displaying suspected clinical characteristics, the verification of KOA or the assessment of joint involvement may necessitate the execution of radiography or magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans [

16]. Systemic biomarkers of KOA have extensively been searched especially in urine and serum samples, however, their concentrations could be influenced by any joint, which can interfere with diagnosis. Furthermore, KOA is characterized by the degradation of cartilage and other local tissues involved, thus synovial fluid (SF) seems to be suitable for studies due to its direct contact with the affected cartilage.

Led by the plethora of addressed evidence, the aim of the present study was to identify specific biomarkers alike ACRP-30, IL10, TNF-α, and IL-6 in SF and correlate them with patients’ clinical data.

2. Materials and Methods

Patient Selection

The group involved in the present study consists of 24 patients over 50 years of age, diagnosed with KOA in our Outpatient Physical Rehabilitation Center, in Timisoara, Romania, between January 2022 and September 2023. Every patient who was included in the study group homologized with the inclusion criteria, signed a consent agreement form, and did not carry out any of the exclusion criteria. The present study was guided according to the Declaration of Helsinki and the design was approved by the Local Ethical Committee at the “Victor Babes” Medical University of Timisoara, Romania (75/10.12.2021).

The inclusion criteria for subjects were as follows:

Written consent for participation signed;

Age > 50 years at diagnosis;

-

Accomplishing the criteria of the KOA diagnosis according to the American College of Rheumatology: pain at the level of knee + at least one of the following conditions:

Existence of the joint effusion identified and aspirated by ultrasound guidance;

None of the exclusion criteria.

The exclusion criteria for subjects were as follows:

Age < 50 years at diagnosis

Previous surgical intervention on the target knee

Anterior injections with steroids or hyaluronans to the target knee (in the last 6 month)

The presence of knee infections or an infection within 3 months before enrollment

History of knee trauma (in the last 6 month)

Clinical Evaluation

Demographic data were collected, including gender, age as well as body mass index (BMI), the presence of knee pain, crepitus, joint stiffness, and clinical joint effusion. Pain, stiffness, and function were evaluated using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC), composed of three subscales, including pain (5 items, 0–20 points), joint stiffness (2 items, 0–8 points) and physical function (17 items, 0–68 points). The final score for the WOMAC was determined by adding the aggregate scores for pain, stiffness, and physical function. Scores range from 0 to 96 for the total WOMAC where 0 represents the best health status and 96 the worst possible status. The higher the score, the poorer the function [

17]. Pain assessment in these patients includes the use of a generic unidimensional Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) also.

Body mass index (BMI) was calculated on the day of the joint fluid collection according to the formula:

Imaging

All patients performed a supine X-ray, the target knee was scanned from both, anterio-posterior and lateral views. Then, the stage of KOA was assessed according to the Kellgren–Lawrence (K-L) scale [

7]. The K-L scale uses five grades (none, doubtful, minimal, moderate, and severe) to classify the severity of KOA and is one of the most used classification methods. Its explanation is as follows:

None/ grade 0 = definite absence of X-ray changes of osteoarthritis

Doubtful/ grade 1 = uncertain joint space narrowing, uncertain osteophytic lipping

Minimal/ grade 2 = definite joint space narrowing and osteophytes

Moderate/ grade 3 = moderate multiple osteophytes, definite narrowing of joint space, sclerosis, and eventual deformity of bone ends

Severe/ grade 4 = large osteophytes, significant narrowing of joint space, marked sclerosis and obvious deformation of bone ends.

Ultrasound was performed using an ESAOTE MyLab Omega (ESAOTE Spa, Italy) ultrasound device and a 6-19 MHz linear array transducer, immediately after the clinical evaluation to confirm the joint effusion as well as to guide the fluid aspiration.

All evaluations were achieved by the same physician, in order to avoid intrasession variability.

Obtaining and Evaluation of the Material

The specimen of SF was obtained from the suprapatellar recess by ultrasound guided aspiration. The volume was then aliquoted, frozen, and stored at -80 ºC for further analysis. SF samples were defrosted on the day of testing, one aliquot for a single test and evaluation of IL-10, IL-6, and TNF-α concentrations were performed using commercial ELISA kits: Invitrogen IL10 Human ELISA Kit EHIL10 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc.), Invitrogen IL6 Human ELISA Kit EH2IL6 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc), Invitrogen TNF alpha Human ELISA Kit KHC3011 (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc). To assess the concentration of adiponectin, the following ELISA kit was used: Adiponectin (total) ELISA Kit (Immunodiagnostik AG).

The protocols were respected according to manufacturers’ instructions and the measurements were done at the Department of Biochemistry, “Victor Babes” Medical University of Timisoara, Romania, using a GloMax® Discover Microplate Reader (Promega Inc, USA). All experiments were performed in duplicate, the mean value of two separate measurements was used as a result.

Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using the GraphPad Prism version 6.0.0 software for Windows (GraphPad Software, La Jolla California USA). D’Agostino & Pearson test, Anderson-Darling test, Shapiro-Wilk test, and Kolmogorov-Smirnov test were applied to analyze data. Correlations were done with the two-tailed Spearman test. All the presented experimental data are as means ±standard deviation (SD). The obtained statistically significant differences between results were highlighted with * (* p < 0.1; ** p < 0.01; *** p < 0.001; **** p < 0.0001). The evaluation of the correlation’s strength was conducted using the subsequent points of reference: r = 1-full correlation, 0.9 < r < 1.0-almost complete correlation, 0.7 < r ≤0.9-very strong correlation, 0.5 < r≤0.7-strong correlation, 0.3 < r ≤0.5-medium correlation,1 < r ≤0.3—weak correlation, 0.0 < r ≤0.1-very weak correlation, and r = 0-no correlation.

3. Results

The studied group consisted of 24 patients respecting the inclusion criteria, with a close distribution of both sexes, 10 males (41.7%) and 14 females (58.3%). The demographic and clinical characteristics are presented in

Table 1. The mean age was 67 years, and the BMI indicates that most of the subjects involved were overweight. The calculated K-L score shows that the majority of patients present grade 2/3 KOA, with possible joint space narrowing, moderate multiple osteophytes, sclerosis, and eventual deformity of bone ends. In addition, most subjects manifest moderate pain, but significant rigidity. The Physical Function score highlights that the Activities of Daily Living (ADLs) are moderately affected. The WOMAC Pain subscale and The Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) suggest similar moderate pain and discomfort in most cases.

The mean values of ACRP-30(ng/mL), IL-6(pg/µL), IL-10 (ng/µL) and TNF-α (pg/mL) levels presented in SF are presented in

Table 2.

When comparing demographic and clinical characteristics of the studied group with biomarkers found in patients’ SF (

Table 3), significant correlations were found between age and ACRP-30 (p=0.0451, r=-0.412), advancing in age being associated with a reduction in adiponectin levels. Also, the IL-10 values are lower in cases where the intensity of the pain is more pronounced (p=0.0405, r=-0.421). BMI was as well associated with the reduction of both tested interleukins (p=0.168 for IL-6 and p=0.104 for IL-10). Stiffness was related to IL-10 reduction (p=0.15, r=-0.302).

When analyzing the interdependence of the monitored biomarkers, significant positive correlations were obtained between ACRP-30 and IL-6, adiponectin levels being associated with IL-6 augmentation levels (p=0.045, r=0.413). The increased values of IL-6 were also associated with the significant increase of IL-10 values (p=3.42e-07, r=0.837).

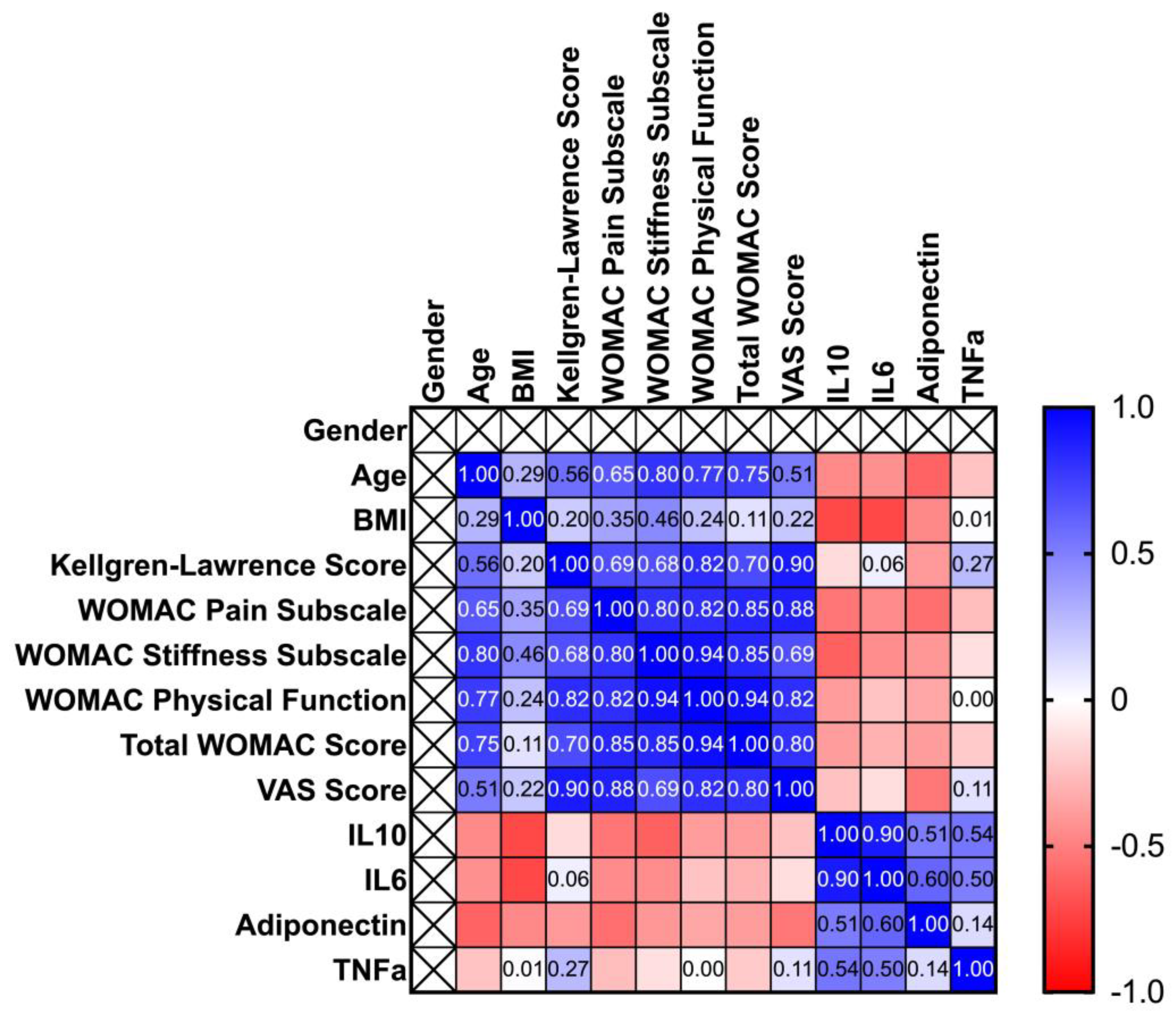

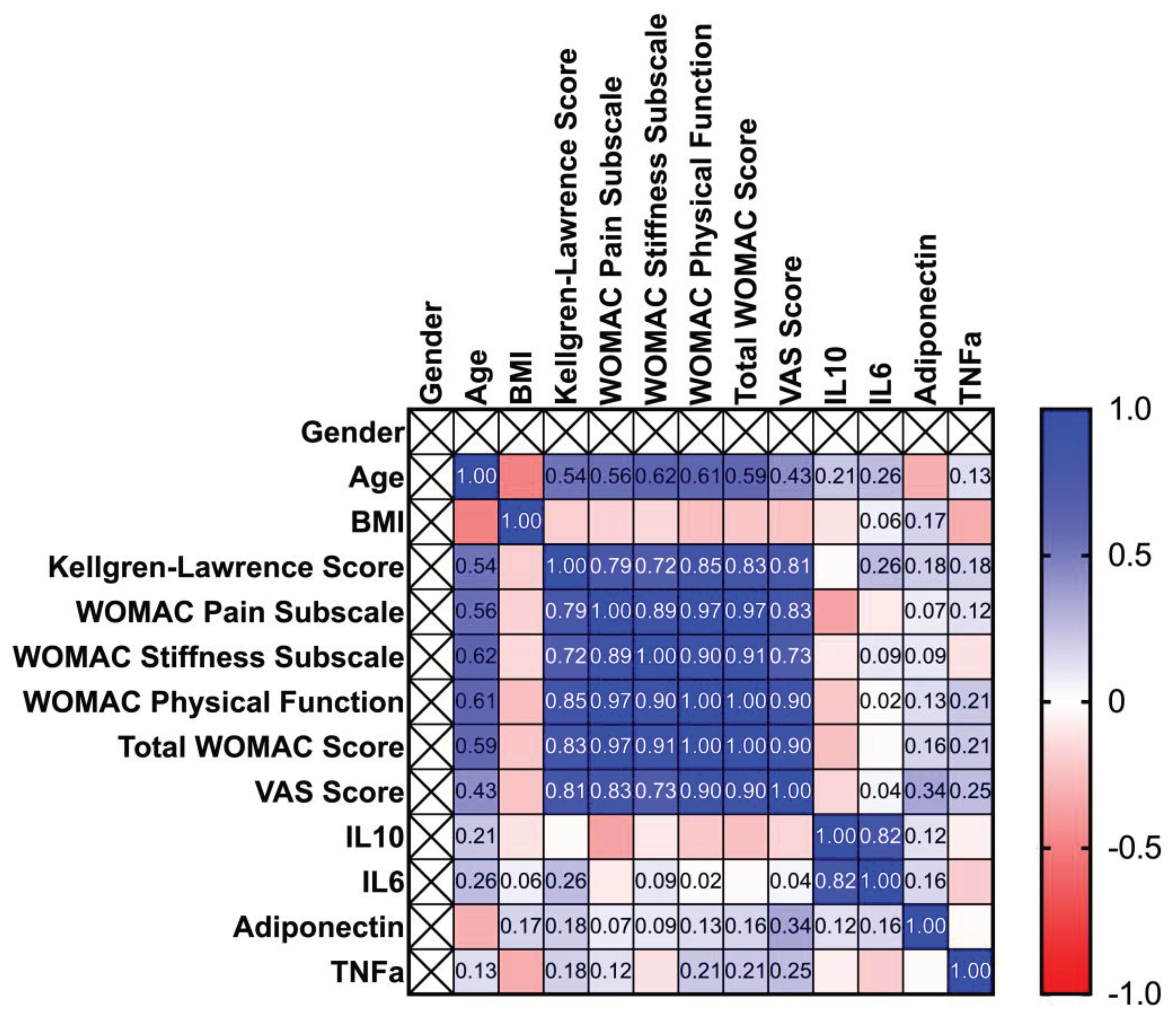

The next step of the study was to stratify the patients by gender, in order to identify some characteristics specific for men/women. Spearman correlation matrixes are depicted in

Figure 1 and

Figure 2 as heatmaps. In the case of both sexes, age is positively correlated to WOMAC Pain subscale, WOMAC stiffness subscale, WOMAC ADL and Total WOMAC scores. Though in case of males, stiffness is more related to age (p=0.0079, r=0.7993), compared to women (p=0.0203, r=0.6223). The KOA severity is positively correlated to the WOMAC pain subscale score, stiffness, ADL, VAS scores, and total WOMAC score. However, the progression of the disease tends to increase more intensively total WOMAC score’s values in the case of women (p=0.00031, r=0.8342), comparing with men (p=0.0289, r=7013). The WOMAC pain subscale score is also positively correlated to stiffness, ADL, and total WOMAC scores, which are more pronounced in the case of women (p=6.14465e-05, 2.3125e-07 and respectively 6.82739e-08), compared to men (p=0.00939,0.00566, and respectively 0.00150). Regarding interleukins and BMI, significant correlations were observed only in the case of men (p=0.0239 for IL-10 and 0.02335 for IL-6). The whole correlation analysis is detailed in

Supplementary File S1.

4. Discussion

KOA remains a significant health problem and identification of risks for incidence or disease progression remains challenging, as radiography, the most common method of identification is not sensitive enough, especially in case of molecular changes that can occur in affected cartilage and bone [

18]. The aim of the present work was to correlate the patients’ clinical data with specific biomarkers alike ACRP-30, IL10, TNF-α and IL-6 found in SF.

Analyzing demographic data, in the present study it was observed that women had a slightly higher prevalence compared to men (58.3% vs 41.7%). A moderately higher prevalence among women was also observed in several studies, thus a recent review including 88 studies with 10,081,952 subjects observed that the proportion of prevalence and incidence in females/males were 1.69 (95% CI, p<0⋅00) and 1.39 (95% CI, p<0⋅00), respectively [

19]. It was also noticed that the majority of subjects with KOA were overweight in our study. Previous research studies investigated whether age and BMI can facilitate the identification of accelerated KOA compared with the common form of the illness. They concluded that older people with higher BMI and other injuries, were more liable to develop accelerated KOA than the common form [

20].

One of the most common methods of classification of KOA is the use of K-L scale [

21,

22]. In this case, results highlighted that 2/3 were the most encountered grades, bringing out that patients with joint effusion present minimal to moderate score of KOA. However, patients complain of moderate pain, but more pronounced stiffness, which affects ADL. Thus, in our case, pain and discomfort seem not to be the major cause of alarm for patients, but rather the affectation of joint elasticity. A recent study confirmed that the incidence of pain and tenderness in the case of KOA is 36.8–60.7%, this being most often accompanied by limited activity, joint deformities, bone rub feeling, and muscle atrophy [

23]. Biomarkers serve as essential tools for predicting disease and distinguishing between pathological and physiological events. Essentially, biomarkers can provide a pathway for studying the early progression of KOA. ACRP-30 is secreted by white adipose tissue and is usually found in SF and cartilage tissues of patients with KOA [

24,

25]. The role of adipokine in KOA remains indefinite. Certain researchers found out a protective effect of ACRP-30 in KOA [

10,

26], while others observed no correlation [

27], or on the contrary, a positive correlation, ACRP-30 being associated with both radiological and clinical severity of KOA [

28]. In our study, a new association was found, between age and ACRP-30, advancing age being correlated with the reduction of ACRP-30 levels. In addition, adiponectin levels were positively associated with IL-6 augmentation levels. A similar effect was observed in another study, where the association of proinflammatory agents with ACRP-30 was analyzed in the SF of arthritis patients. Results showed that ACRP-30 functioned synergistically with IL-1β to activate IL-8 and IL-6 expression in synoviocytes [

29]. Another research showed that in cultured chondrocytes, ACRP-30 treatment increased in a dose-dependent manner the pro-inflammatory factors such as IL-6, inducible nitric oxide synthase, and metalloproteases [

30]. Contrarily, Udomsinprasert et al. observed that ACRP-30 levels from SL were negatively associated with C-reactive protein and IL-6 levels and positively correlated with 25(OH)D levels in KOA affected patients [

31].

Furthermore, the increased values of IL-6 were also associated with the significant increase of IL-10 values (

Table 4). IL-10 is a cytokine with significant anti-inflammatory potential, that broadly has to downregulate proinflammatory cytokine activity. Similar to our findings, Mabey and colleagues observed that median plasma levels of proinflammatory cytokines (IL-6) and anti-inflammatory ones (IL-2, IL-4, IL-10) were significantly superior in patients with KOA compared to healthy subjects (controls) [

32]. A significant upregulation of IL-10 was discovered in patients subjected to physical exercises, compared to sedentary ones. In a study, in the exercise-group, over the 3 hours post physical effort, IL-10 remained augmented, and unchanged over time in the non-exercise group. Instead, IL-6 showed significant increases over time in both groups [

33]. Also, the IL-10 values were found lower in cases where the intensity of the pain and stiffness were more pronounced. Interleukins’ reduction was also associated to BMI. Thus, the heavier the patients, the lower the amount of cytokine was observed (p=0.168 for IL-6 and p=0.104 for IL-10).

Proinflammatory cytokines including IL-6 and TNF-α have been demonstrated to present catabolic effects by reducing collagen synthesis or increasing matrix metalloproteinases [

32]. Instead, immunoregulatory and anti-inflammatory cytokines, such as IL-10, suppress proinflammatory ones expression and stimulate cartilage synthesis [

34]. A disequilibrium in the anabolic and catabolic processes in affected joints results in the degradation and depletion of cartilage, processes that may be directly affected by cytokine imbalance.

When data were analyzed stratified by sex, it was observed that in the case of males, rigidity is more related to age (p=0.0079), compared to women (p=0.0203). Moreover, in men, a significant relationship was observed between BMI and interleukins. The disease tends to increase more intensively the total WOMAC values (p=0.00031) in women compared with men (p=0.0289). The WOMAC pain subscale score is also positively correlated to stiffness, ADL, and total WOMAC scores, which are more pronounced in the case of women. These data suggest that women with KOA are more sensitive to pain and articular rigidity. The anatomical variances between females and males could potentially have an impact in the evolution of the disease, but also on the symptomatic manifestations, consisting of thinner patellae, narrower femurs, larger quadriceps angles, and variations in tibial condylar size [

35].

5. Conclusions

Knee osteoarthritis remains a challenging problem affecting millions of people daily. Biomarkers for this disease are continuously researched. In the present study, IL-6, TNF-α, IL-10, and adiponectin were studied. Results highlighted a significant correlation between age and ACRP-30, and ACRP-30 and IL-6, suggesting that advanced age may contribute to adiponectin reduction, and this also manifests a synergistic effect with IL-6. At the same time, IL-6 increase attracts IL-10 augmentation. Comparing men with women, it was observed that men’s age is more related to rigidity, and IL-6 and IL-10 are directly correlated to BMI. Rather, women seem to be more sensitive to pain and stiffness.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.I.; methodology, D.N. and P.C,; software, I.I.; validation, C.M. and I.I.; formal analysis, C.M.; investigation, P.C. and D.N; writing—original draft preparation, I.I. and A.A.; writing—review and editing, C.M.; visualization, C.M.; supervision, C.M.; project administration, C.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by “Victor Babes” University of Medicine and Pharmacy Timisoara, Doctoral School.

Institutional Review Board Statement

“The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of “Victor Babes” Medical University of Timisoara, Romania (75/10.12.2021).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Sulastri, D.; Arnadi, A.; Afriwardi, A.; Desmawati, D.; Amir, A.; Irawati, N.; Yanis, A.; Yusrawati, Y. Risk factor of elevated matrix metalloproteinase-3 gene expression in synovial fluid in knee osteoarthritis women. PLoS One 2023, 18(3), e0283831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, Y.; Jordan, J.M. Epidemiology of osteoarthritis. Clin. Geriatr. Med. 2010, 26, 355–369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blajovan, M.D.; Arnăutu, D.A.; Malița, D.C.; Tomescu, M.C.; Faur, C.; Arnăutu, S.F. Fall Risk in Elderly with Insomnia in Western Romania—A Retrospective Cross-Sectional Study. Medicina (Kaunas) 2023, 59, 718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wallace, I.J, Worthington, S.; Felson, D.T.; Jurmain, R.D.; Wren, K.T.; Maijanen, H.; Woods, R.J.; Lieberman, D.E. Knee osteoarthritis has doubled in prevalence since the mid-20th century. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2017, 114, 9332–9336.

- Hannan, M.T.; Felson, D.T.; Anderson, J.J.; Naimark, A.; Kannel, W.B. Estrogen use and radiographic osteoarthritis of the knee in women. Arthritis Rheum. 1990, 33, 525–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felson, D.T.; Zhang, Y.; Anthony, J.M.; Naimark, A.; Anderson, J.J. Weight loss reduces the risk for symptomatic knee osteoarthritis in women: The framingham study. Ann. Intern. Med. 1992, 116, 535–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jarecki, J.; Małecka-Massalska, T.; Polkowska, I.; Potoczniak, B.; Kosior-Jarecka, E.; Szerb, I.; Tomaszewska, E.; Gutbier, M.; Dobrzyński, M.; Blicharski, T. Level of Adiponectin, Leptin and Selected Matrix Metalloproteinases in Female Overweight Patients with Primary Gonarthrosis. J. Clin. Med. 2021, 10, 1263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frühbeck, G.; Catalán, V.; Rodríguez, A.; Gómez-Ambrosi, J. Adiponectin-leptin ratio: A promising index to estimate adipose tissue dysfunction. Relation with obesity-associated cardiometabolic risk. Adipocyte 2018, 7, 57–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honsawek, S.; Tanavalee, A.; Yuktanandana, P. Elevated Circulating and Synovial Fluid Endoglin Are Associated with Primary Knee Osteoarthritis Severity. Arch Med Res 2009, 40, 590–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Honsawek, S.; Chayanupatkul, M. Correlation of Plasma and Synovial Fluid Adiponectin with Knee Osteoarthritis Severity. Arch. Med. Res. 2010, 41, 593–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stannus, O.; Jones, G.; Cicuttini, F.; Parameswaran, V.; Quinn, S.; Burgess, J.; Ding, C. Circulating levels of IL-6 and TNF-α are associated with knee radiographic osteoarthritis and knee cartilage loss in older adults. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2010, 18, 1441–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Botha-Scheepers, S.; Watt, I.; Slagboom, E.; De Craen, A.J.M.; Meulenbelt, I.; Rosendaal, F.R.; Breedveld, F.C.; Huizinga, T.W.; Kloppenburg, M. Innate production of tumour necrosis factor alpha and interleukin 10 is associated with radiological progression of knee osteoarthritis. Ann Rheum Dis. 2008, 67, 1165–1169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Behrendt, P.; Häfelein, K.; Preusse-Prange, A.; Bayer, A.; Seekamp, A.; Kurz, B. IL-10 ameliorates TNF-α induced meniscus degeneration in mature meniscal tissue in vitro. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2017, 18, 197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barker, T.; Rogers, V.E.; Henriksen, V.T.; Trawick, R.H.; Momberger, N.G.; Lynn Rasmussen, G. Circulating IL-10 is compromised in patients predisposed to developing and in patients with severe knee osteoarthritis. Sci Rep 2021, 11, 1812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heidari, B. Knee osteoarthritis diagnosis, treatment and associated factors of progression: Part II. Casp J Intern Med 2011, 2, 249–255. [Google Scholar]

- Karim, M.R. Jiao, J.; Dohmen, T.; Cochez, M.; Beyan, O.; Rebholz-Schuhmann, D.; Decker, S. DeepKneeExplainer: Explainable Knee Osteoarthritis Diagnosis from Radiographs and Magnetic Resonance Imaging. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 39757–39780. [CrossRef]

- Jung, Y.O.; Do, J.H.; Kang, H.J.; Yoo, S.A.; Yoon, C.H.; Kim, H.A.; Cho, C.S.; Kim, W.U. Correlation of sonographic severity with biochemical markers of synovium and cartilage in knee osteoarthritis patients. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2006, 24, 253–259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Attur, M.; Krasnokutsky-Samuels, S.; Samuels, J.; Abramson, S.B. Prognostic biomarkers in osteoarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2013, 25, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cui, A.; Li, H.; Wang, D.; Zhong, J.; Chen, Y.; Lu, H. Global, regional prevalence, incidence and risk factors of knee osteoarthritis in population-based studies. EClinicalMedicine 2020, 29-30, 100587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Driban, J.B.; Eaton, C.B.; Lo, G.H.; Price, L.L.; Lu, B.; Barbe, M.F.; McAlindon, T.E. Overweight older adults, particularly after an injury, are at high risk for accelerated knee osteoarthritis: data from the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Clin Rheumatol. 2016, 35, 1071–1076. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kellgren, J.H.; Lawrence, J.S. Radiological assessment of osteo-arthrosis. Ann Rheum Dis 1957, 16, 494–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macri, E.M.; Runhaar, J.; Damen, J.; Oei, E.H.G.; Bierma-Zeinstra, S.M.A. Kellgren/Lawrence Grading in Cohort Studies: Methodological Update and Implications Illustrated Using Data From a Dutch Hip and Knee Cohort. Arthritis Care Res 2022, 74, 1179–1187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, L.; Zhou, G.; Yang, W.; Liu, J. Guidelines for the diagnosis and treatment of knee osteoarthritis with integrative medicine based on traditional Chinese medicine. Front Med 2023, 10, 1260943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ilia, I.; Nitusca, D.; Marian, C. Adiponectin in Osteoarthritis: Pathophysiology, Relationship with Obesity and Presumptive Diagnostic Biomarker Potential. Diagnostics 2022, 12, 455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, J.; Xu, J.; Wang, K.; Zhu, Q.; Cai, J.; Ren, J.; Zheng, S.; Ding, C. Associations between circulating adipokines and bone mineral density in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study. BMC Musculoskelet Disord. 2018, 19, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, S.; Xu, J.; Xu, S.; Zhang, M.; Huang, S.; He, F.; Yang, X.; Xiao, H.; Zhang, H.; Ding, C. Association between circulating adipokines, radiographic changes, and knee cartilage volume in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Scand J Rheumatol. 2016, 45, 224–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berry, P.A.; Jones, S.W.; Cicuttini, F.M.; Wluka, A.E.; MacIewicz, R.A. Temporal relationship between serum adipokines, biomarkers of bone and cartilage turnover, and cartilage volume loss in a population with clinical knee osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 2011, 63, 700–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cuzdan Coskun, N.; Ay, S.; Evcik, F.D.; Oztuna, D. Adiponectin: is it a biomarker for assessing the disease severity in knee osteoarthritis patients? Int J Rheum Dis 2017, 20, 1942–1949. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.A.; Choi, H.M.; Lee, S.H.; Yang, H.I.; Yoo, M.C.; Hong, S.J.; Kim, K.S. Synergy between adiponectin and interleukin-1β on the expression of interleukin-6, interleukin-8, and cyclooxygenase-2 in fibroblast-like synoviocytes. Exp Mol Med. 2012, 44, 440–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, Q.; Hu, Z.C.; Shen, L.Y.; Shang, P.; Xu, H.Z.; Liu, H.X. Association of osteoarthritis and circulating adiponectin levels: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lipids Health Dis 2018, 17, 189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udomsinprasert, W.; Manoy, P.; Yuktanandana, P.; Tanavalee, A.; Anomasiri, W.; Honsawek, S. Decreased Serum Adiponectin Reflects Low Vitamin D, High Interleukin 6, and Poor Physical Performance in Knee Osteoarthritis. Arch Immunol Ther Exp (Warsz) 2020, 68, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mabey, T.; Honsawek, S.; Tanavalee, A.; Yuktanandana, P.; Wilairatana, V.; Poovorawan, Y. Plasma and synovial fluid inflammatory cytokine profiles in primary knee osteoarthritis. Biomarkers 2016, 21, 639–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helmark, I.C.; Mikkelsen, U.R.; Børglum, J.; Rothe, A.; Petersen, M.C.; Andersen, O.; Langberg, H.; Kjaer, M. Exercise increases interleukin-10 levels both intraarticularly and peri-synovially in patients with knee osteoarthritis: a randomized controlled trial. Arthritis Res Ther 2010, 12, R126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Van Meegeren, M.E.R.; Roosendaal, G.; Jansen, N.W.D.; Wenting, M.J.G.; Van Wesel, A.C.W.; Van Roon, J.A.G.; Lafeber, F.P. IL-4 alone and in combination with IL-10 protects against blood-induced cartilage damage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2012, 20, 764–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hame, S.L.; Alexander, R.A. Knee osteoarthritis in women. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2013, 6, 182–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).