1. Introduction

Composites materials are critical in many applications, and they can replace metallic materials in many systems or goods. The potential applications of ceramic matrix composites reinforced with long continuous ceramic fibers range from room temperature to very high temperature, in ambient or severe environments [

1]. The large variety of possible combinations of matrix and fiber types allows the design of composite materials tailored to application requirements and performances. The composite engineering provides materials with properties superior to the properties of constituents considered separately. Fiber reinforced composites are heterogeneous and anisotropic materials. Taking into account the respective contribution of constituents (fibers, matrix, flaws and interfaces) in the mechanical behavior requires multiscale approach-based analyses [

2]. Questions relative to proper characterization and safe prediction of the mechanical behavior and the failure of composite components are still open.

Tensile testing is a simple and fundamental materials science and engineering test that provides directly mechanical characteristics of materials. However, some extrinsic difficulties may arise from specimen gripping, alignment and material high cost. Therefore certain authors recommended the flexural test during the development stage of a ceramic-fiber composite system, arguing that it can be carried out on small easily prepared specimens using simple jigs [

3]. Authors were also interested in flexural testing with a view to predicting ultimate tensile strength. But, material-induced intrinsic difficulties arise such as the calculation of the flexural strength from the experimental force data, the damage prior to ultimate failure and the influence of stress gradient, specimen size and fabric orientation on the mechanical behavior.

In tensile specimens, during uniaxial tension, a uniform stress-state operates at macroscopic level, and diffuse matrix cracking occurs prior to ultimate failure from a critical fiber [

4]. The following mechanisms during flexural tests on relatively long thin specimens were described [

5] : « First, multiple cracking occurs on the tensile surface at the same stress as in the tension test. Following matrix cracking, the neutral axis of the beam shifts toward the compressive surface. The compressive stresses are enlarged whereas the tensile stresses are relaxed compared to the stresses in the uncracked beam. After further loading, the peak load is dictated by damage in the compressive side of the beam, and involves fiber buckling and matrix fragmentation ». A numerical analysis of the flexural behavior of a laminated ceramic matrix composite considering the constitutive tensile-compressive behavior of each layer and the constitutive shear behavior of the interlaminar regions showed that the neutral axis of the flexure beam migrates towards the compressive side due to progressive fiber failure in the tensile layers [

6]. Delamination cracks were observed on Nicalon SiC/Al

2O

3 [

7], and in both transverse and edge-on orientations on Nextel /SiC [

8], and in transverse orientation on Nicalon /SiC [

8] leading to specimen collapse rather than separation. By contrast, specimen fracture in two pieces was observed on Nicalon /SiC composites in edge-on orientation [

8,

9] (the SiC matrix of which is twice as stiff as the Nicalon fibers), The load was reported to be transferred equally between the plies [

8].

Several values of ultimate flexural strength (UFS) have been reported in the literature for various composites including C/C-SiC [

10], Nicalon/C, Nicalon/CAS, Nicalon/LAS [

12], Nicalon/SiC [

5,

8,

9,

13,

14,

15], Nextel/SiC [

8], Carbon-reinforced Borosilicate glass [

16].

The UFS were found larger than the UTS (Ultimate Tensile Strength). Certain authors attributed this trend to the shift of the neutral axis [

7]. Using an experimental and numerical approach [

10] it was shown that the trend is partially explained by the differing tensile and compression stress-strain behaviors and further by the work of fracture beyond maximum load. In [[

11] the higher the strength ratio was observed when the more the load-deflection curve deviated from linearity. The strength ratio depended most strongly on the behavior of the uniaxial stress-strain curve after the ultimate tensile strength; materials that failed gracefully tended to exhibit higher strength ratio.

The UFS/UTS ratio displayed variability, and depended on the method of determination of flexural strengths. Values of UFS/UTS < 1.5 were obtained using micromechanics based approaches [

12,

13]. Quite larger ratios (>3) and larger UFS were obtained when the flexural strength was calculated using the simple elastic beam equation [

3,

8,

9,

14,

15,

17,

18]. In [

6] it was shown that ordinary beam equations cannot be used to describe the behavior. These equations led to the following high values of the flexural strength of Nicalon/SiC:

- in transverse configuration : 320 MPa [

8,

9], 350 MPa [

5,

15]

- in edge-on configuration : 500 MPa [

9], 430 MPa [

8],

- on 3D fabric reinforced composite: 514 MPa [

14].

Smaller values were obtained using micromechanics based approach on in edge-on configuration: 213 & 187 MPa, (UFS/UTS ratio ~ 1.26) were obtained from only two tensile tests and two four-point flexure tests [

13]. Additionally, it is worth mentioning that composite Weibull modulus of ~ 15 was derived from these experimental data through Monte Carlo simulations [

13]. The authors recognized that a large number of tests is needed to ascertain composite Weibull modulus accurately.

It was observed that the UFS of the Nicalon/Al2O3 and the Nicalon/SiC composites calculated using

ordinary beam equations was not noticeably affected by specimen length increase [

8] whereas there was a significant increase in the UFS of Nicalon/SiC composite when the specimen width was increased [

8].

Tension-bending relations are required for predicting the tensile strength from the flexural strength, or vice-cersa. The bending moment and neutral axis shifting were introduced in models that did not include the physics-based damage phenomena and required asumptions on the stress profile in the bending specimens [

11,

13,

17,

19]. The tensile behavior derived from the bending curve, showed qualitative but not satisfactory agreement with the experimental tensile behavior. The experimental data base was scarce, and not statistically significant [

11,

13,

17]. A few authors recognized the contribution of fiber to flexural ultimate fracture [

12,

13,

20]. The Foster’s analysis [

20] related the nominal bend strength of Titanium/SiC Metal Matrix Composite to fiber bundle strength and to matrix yield strength, and used a Local Load Sharing simulation model to study the evolution of fiber damage.

In most cases, the vicious circle in the analysis of flexural strength data was not broken. Which means that models of flexural behavior could not be compared to experimental behavior, due to the lack of an accepted equation for the calculation of empirical flexural stresses from experimental forces. In comparison, this exercise is straightforward for tensile strengths that are calculated from experimental forces using a simple and accepted equation. An attempt to overcome this difficulty is proposed in the present paper by using three different and independent approaches for the determination of flexural strength : (1) finite element analysis of stress-state, (2) fiber bundle- based approach, (3) stress-strain Hooke relation. The simple equation of elastic beam theory was also used for evaluation purpose.

The present paper investigates the flexural strength of CVI 2D woven SiC/SiC composite with respect to avalable tensile strength results [

4]. It proposes a multiscale approach that recognizes the underlying contribution to failure of fiber tows, single filaments and the critical filament in a tow after matrix damage. The variability of strength data is characterized using the construction of p-quantile diagrams and the Weibull approach. An exact relation between tensile and flexural strengths is proposed. Important trends in the effects of size, stress gradient, tension-flexure relations, strength of critical filament in a tow and populations of critical flaws are established and discussed

2. Background : The Ultimate Failure Under Tensile Loading Parallel to a Fiber Direction

During tensile tests parallel to a principal fiber direction, ceramic matrix composites exhibit a response depending on the respective Young’s moduli of fibers and matrix. Those composites like the SiC/SiC with high matrix modulus and quite strong fiber/matrix interfaces display non linear deformations that result from transverse cracking in the matrix (the cracks are perpendicular to fibres in the loading direction) and limited fiber/matrix debonding. Saturation of matrix damage is indicated by a point of inflection at about 0.4% strain for those composites with a weak interphase, whereas it occurs at higher stress on those composites with a strengthened fibre/matrix interphase.

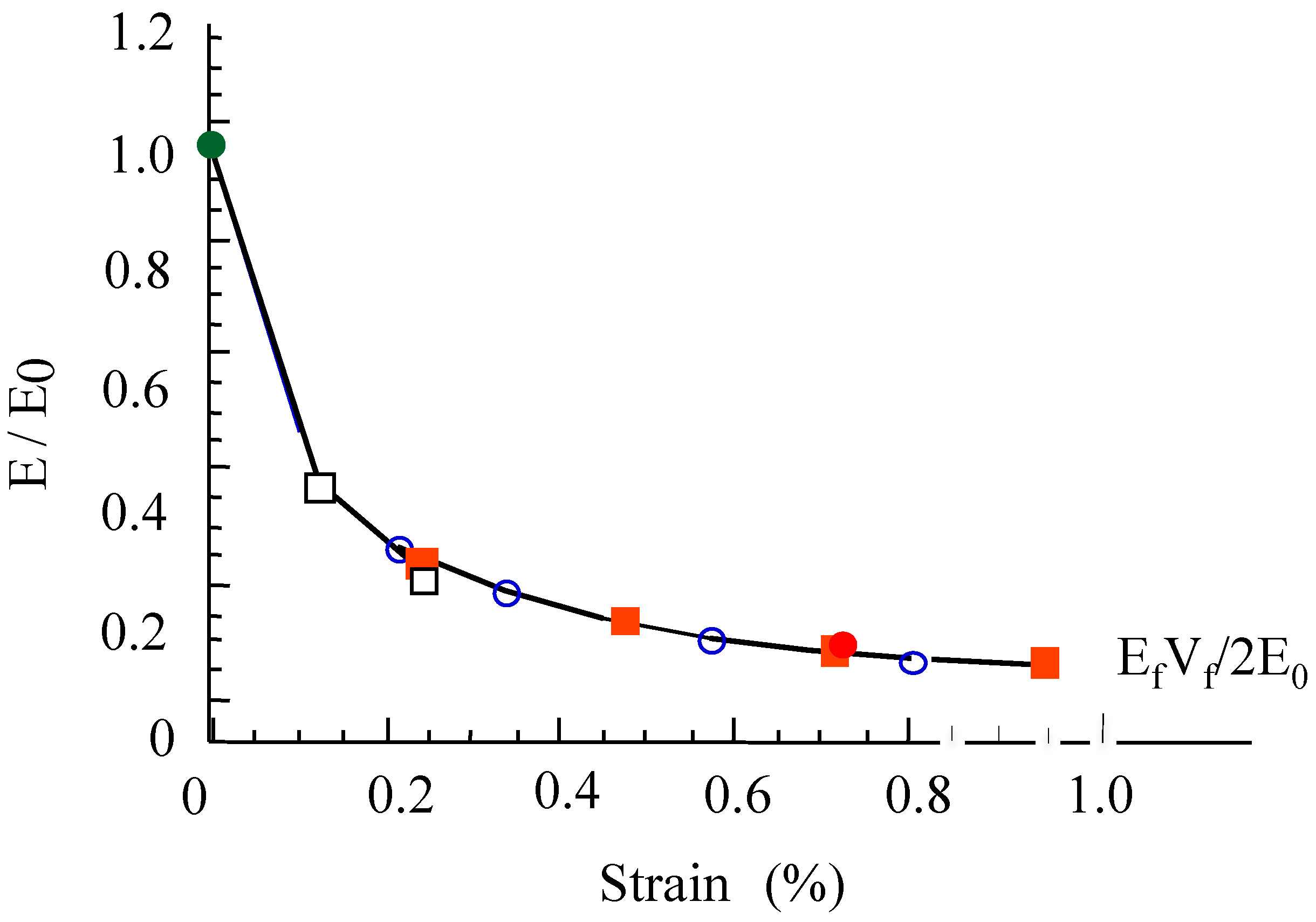

Figure 1 shows the correlative decrease of composite elastic modulus that reflects the increasing damage and the decreasing load carrying capacity of the matrix [

2]. The load is transferred to longitudinal tows that carry the whole load after matrix cracking saturation. The analysis of acoustic emission signals indicate that fracture of filaments starts at strains > 0.6%. The composite elastic modulus reaches the minimum dictated by the debonded longitudinal filaments according to the following rule of mixture:

Vf is the volume fraction of fibres oriented in the loading direction, Ef is fibre elastic modulus.

It was established [

4] that the ultimate failure of composite under

strain-controlled condition of tensile loading is caused by an overload resulting from the friction of pull-out broken fibres against matrix and transferred evenly to the surviving fibers. The overload increases steadily with the number of broken fibers so that the reinforcing tows are subjected to a

force-controlled process although

constant strain rate is applied. The critical fiber which initiates the instability is that when the overload exceeds the filament strength gradient in a tow. The closed form equations that were established for the criterion of initiation and propagation of filament failure in a tow led to a closed form equation for tow and composite strength. The theoretical strength of the critical filament is defined by its rank in the cumulative distribution of filament strengths in a tow, and by the maximum on the tow force-strain curve. The following exact equation of the theoretical strength

f(

P=c), was found to lead to satisfactory predictions of composite tensile ultimate strength [

4]:

where

P is failure probability,

αc is failure probability the critical filament strength,

m and

σ0 are the Weibull statistical parameters pertinent to filament strengths,

V is the volume,

V is the reference volume (1m

2),

is the mean stress, Γ is the gamma function,

Equation (2) was found to be more appropriate than equations proposed in the literature that misestimated significantly the strength [

4]. It is worth pointing out that equation (2) shows that the theoretical strength

σf(

P=αc) takes a unique value when statistical parameters are invariant with tow specimens of identical dimensions [

4,

21]. However, experimental results show that the rank and the strength of critical flament are affected by structural effects like local friction. The associated strength scatter was attributed to the variation in friction induced overload resulting from variability in fiber/matrix interface characteristics and filament surface roughness.

Under these conditions of strain-controlled loading, and in the absence of pull-out friction from broken fibers, the fracture would be dictated by the strength of the strongest filament. The force-strain curve would exhibit a smooth and stable force decrease.

3. Experimental : Material and Procedure

The experimental results were generated in a previous paper [

22,

23]. The 3-point bending tests were performed on 2D woven SiC/SiC composite specimens made via chemical vapor infiltration (CVI) [

22,

23]. SiC/SiC was reinforced by aboutf SiC Nicalon fibres in a plain weave configuration. The testspecimens were cut out of plates 3.3 mm thick. Two batches of straight bars (8x80x3.3 mm

3) for the symmetric and asymmetric 3-pt bending tests that generate symmetric and asymmetric stress gradients.

The flexural specimens were loaded edge-on parallel to the woven plies, in order to prevent delamination between layers and thus, compare properly tension and bending results. Furthermore, the specimens were relatively thin (height/span length = 0.1) so that the relative shear stress was minimized. The displacement rate was chosen so as to obtain the same strain rate of 4 10

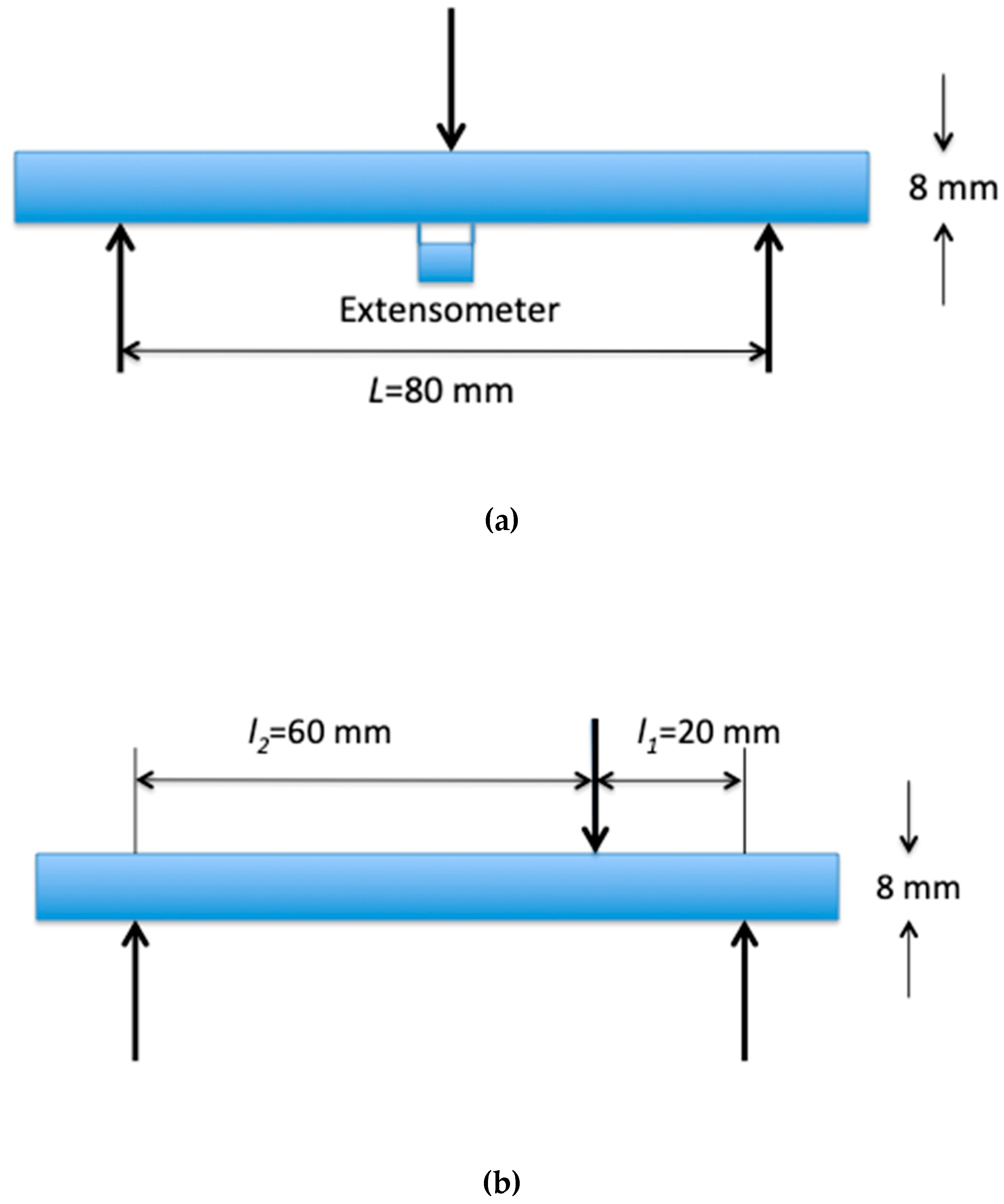

-4 %/s in the outer tensile face as for the tensile testspecimens. Strains in the outer tensile face were measured using an extensometer with a 10 mm gauge length (

Figure 2a).

The experimental results of tensile tests were reported in a previous paper. The two batches of each 12 tensile SiC/SiC specimens were manufactured together with the batches of bending specimens: a batch of small (V

1= 8x30x3.3 mm

3) and a batch of large (V

2 = 16x120x3.3 mm

3) dogbone shaped-specimens [

22,

23]. The flexural and the smaller tensile specimens had identical cross-section dimensions. The strain rate was 4 10

-4 %. Strains were measured using an extensometer over a 25 mm gauge length

4. Determination of Flexural Strength

4.1. Finite Element Analysis

A mesh of 4x40 quadrilateral elements (size : 2x2 mm

2) was constructed for the finite element analysis of the stress-state [

11]. The size of elements was selected according to that of Representative Volume Element. The boundary conditions reproduced the loading conditions in the 3-pt bending tests as described above : (i) displacements applied through the upper roller, (ii) plane stress conditions. The compressive behaviour was taken to be linear although a slight non linearity has been reported by McNulty and Zok [

5]. The contribution of damage to deformations in the tensile part of specimens was taken into account using the Young's modulus-strain relationship determined from the strain-stress behaviour obtained during tensile tests [

1,

2] (

Figure 2). For this purpose, strains were computed first for the initial value of composite Young’s modulus (226 GPa:

Table 1). Then, for the same applied displacement, they were computed for values of Young’s modulus corresponding to the current strain-state. The procedure was iterated until the discrepancy between strains at two successive steps was negligible. The tensile response was assumed to be orthotropic, with non coupled tow directions. Since the specimens were loaded parallel to the plies, the transverse properties were neglected.

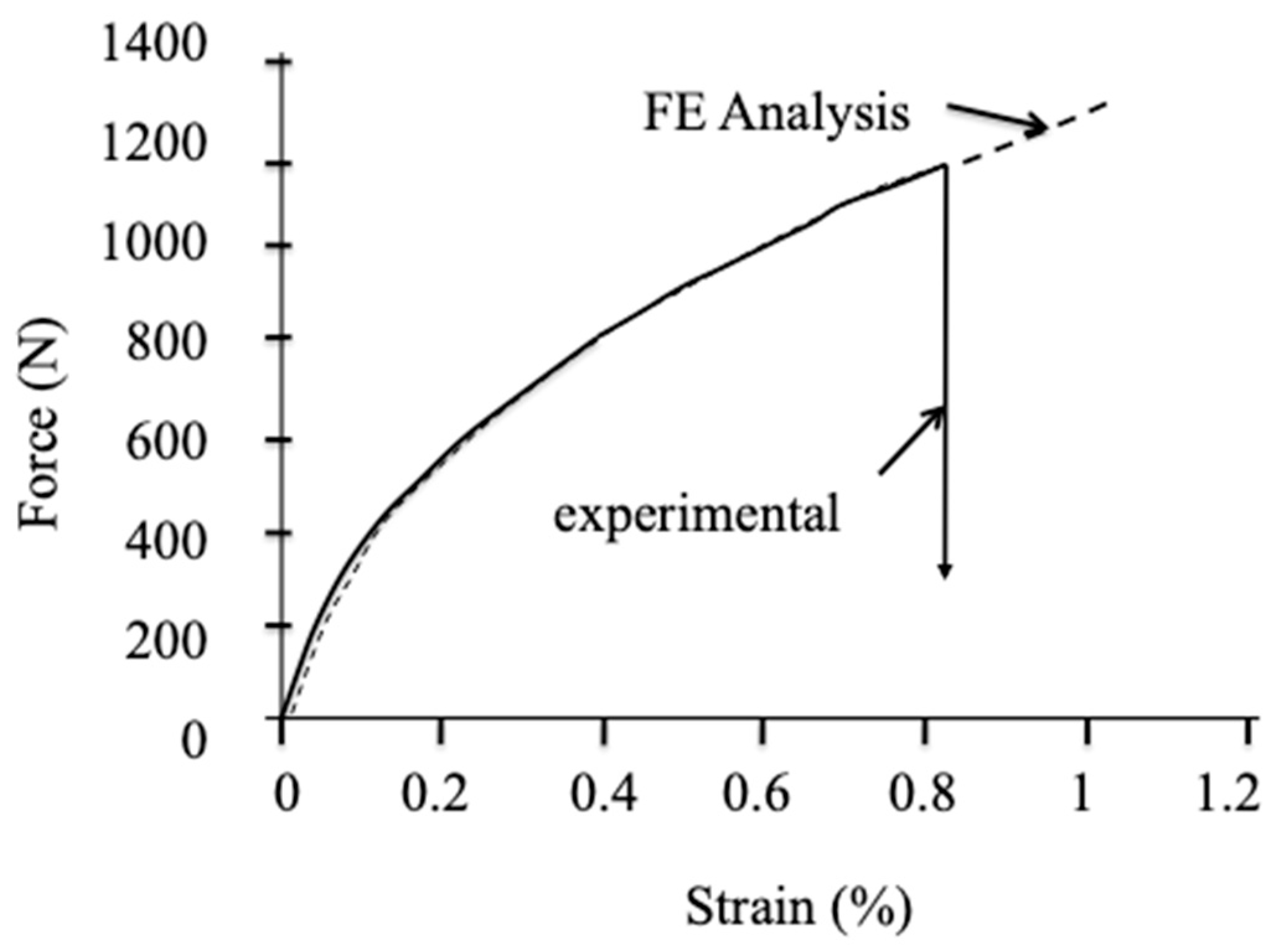

The finite element computations provided the strain- and stress-fields for various applied forces. The force-strain curves relate the applied forces and the corresponding strains located in the outer face on the force axis. The ultimate strength is given by the maximum tensile stress computed for the failure force measured during the tests.

4.2. Elastic Beam Theory

The flexural strength under symmetric 3-point bending was alternately derived using the following formulae based on the elastic beam theory for homogeneous isotropic solid:

where

Fm is the maximum applied force;

L is the outer span length,

b is the mean width and

h is the mean thickness of the test specimen.

This equation is based on the following assmptions:

- The beam is symmetrical about neutral plane

- The beam is a straight bar of homogeneous and linearly elastic material

- The transverse plane sections remain plane and normal to the longitudinal fibres after bending (Bernoulli’s assumption).

- The fixed relationship between stress and strain (Young’s modulus) for the beam material is the same for tension and compression.

The behavior of beams made of CFRC composites is different from that of homogeneous elastic materials as soon as matrix damage initiates. This equation was used although its applicability to fiber-reinforced CMC is questionned, in order to evaluate error on estimated strength.

4.3. Strength Estimated from Measured Strain at Failure

The flexural strength is related to the maximum strain at failure in the outer tensile surface of bending specimen by the Hooke equation:

where

εmax is the maximum strain in the outer surface of specimens, and

E(εmax) is the corresponding value of Young’s modulus, which was derived from tensile tests, after saturation of matrix cracking [

1]:

E(εmax)=

Emin is given by equation (1).

Ef is the Young’s modulus of filaments,

Vf is the fraction of fibers in the longitudinal axis direction. Assuming a linear strain gradient,

εmax was derived from the measured strain

εmeasured using the following equation:

where

z is the abscissa of

ε(z) on longitudinal axis of specimen,

z=0 for

εmax at midspan, z=5 mm for

εmeasured (half gage length).

L is the span length. The flexural strength was calculated using equations (4) and (5) for the SiC/SiC experimental data given in

Table 1.

4.4. Prediction: The Bundle-Based Approach

It was assumed that the critical tow is completely debonded after saturation of matrix cracking, which is also supported by several results [

1,

2]. It was assumed that failure due to shear is not an issue and our concern is the longitudinal direction stress and its resulting distribution. The fibers are subjected to a bending moment, which generates a stress gradient. The principle of the approach is to define a volume equivalent to the fiber stressed volume under uniform tension on the basis of Weibull statistics, and then to derive the bending strength from the tensile strength for the critical fiber in the tow. It has been shown that multifilament tows are elastic and damage tolerant, whereas single fibers are brittle. The multifilament tows exhibit a non-linear force-strain relation resulting from successive individual fiber breaks under controlled deformation rate [

21]. The fraction of fiber fractures at maximum force defines the critical filament that can initiate the failure of tow [

21]. It is widely accepted that the Weibull model satisfactorily describes the statistical distribution of failure strengths of single filaments under tensile loads [

24].

Symmetric 3-Point Bending

The approach is founded on the following asumptions :

- A tensile tress gradient operated along specimen length

- The stress was considered to be constant through the cross section of filaments in the tensile part of beam. The through thickness stress gradient can be neglected because fiber diameter (12 micrometers) is negligible compared to specimen thickness (4 mm in the tensile part).

- The highest stresses opérâtes on the extreme ply close to the specimen outer surface under tension.

- As discussed in previous papers, fracture is initiated from a critical fiber in the ply subjected to highest tensile longitudinal stresses, after saturation of matrix cracking.

- A linear tensile stress gradient on filaments located at the bottom side of the beam was assumed. It is symmetric with respect to the loading axis:

where

σmax is the peak tensile stress in the ply.

L is the span length. The origin is the center of the specimen, -

L/2<

z<

L/2,

L is the stressed fiber length.

The volume of a statistically equivalent ply subjected to peak tensile stress operating uniformly was defined using the cumulative Weibull distribution of filament strengths

σ [

25]:

where

σ0 is the scale factor,

m is the Weibull modulus,

S is the cross sectional area of a filament,

V0 is a reference volume (

V0=1m

3).

Introducing equation (6) into (7), and integrating it comes :

Equation (9) gives the equivalent filament stressed volume subjected to

σmax operating uniformly:

The cumulative distribution of filament strengths under uniform tension is:

where

σt is fiber tensile strength,

lt is the gauge length.

The relation between the bending and the tensile filament strengths is obtained from equating probabilities:

For the volume fraction of longitudinal fibers

Vf, the flexural strength of composite is related to the strength of tensile specimen by the expression:

and σflex . σflex is composite flexural strength, is the strength of critical filament in flexural specimen, σtr is the strength of tensile specimen, is the tensile strength of the critical fiber in the tensile specimen having gauge length lt. mc is the Weibull modulus of critical filament strength.

It is important to point out that equations (7) to (10) are relative to filament distribution, whereas equations (11) and (12) derive from equations relative to filaments having the same specified probability. Equation (12) corresponds to the critical filament that fails in critical tow at fracture of a tensile or flexural composite testspecimen:

σt(P=αc) is given by equation (2).

Asymmetric 3-point bending

The approach is founded on the same asumptions as above. The following asymmetric linear tensile stress gradient on fibers located at the bottom side of the beam was assumed:

The origin is located on the loading axis, -

l2<

z<

l1, with

l2+

l1=L. l2 and

l1 are defined on

Figure 2.

The probability of failure of a filament under stress

σ, is given by:

Introducing equations (13) and (14) into (15) and integrating it comes :

The effective volume defined by equation (16) is given by the same equation as above for symmetric bending: . As a consequence, the flexural strength is given also by equation (12), which indicates that is not affected by asymmetric stress gradient.

5. Strength Variability

Strength variability was approached using p-quantile diagrams that provide a proper and unbiased way to evaluate the pertinence of normal distribution function. Thus, it was demonstrated that when the plot of the p-quantile

zp vs. strength

σp is linear, it can be concluded that the strength is a Gaussian variable [

24].

The equation of p-quantile diagrams is:

where

P=i/(n+1),

μ = mean,

s = standard deviation,

σp is the value of strength with probability

P, and Φ is the cumulative standard normal distribution of variable

z.

The normal cumulative distribution function (CDF) was calculated using Equation (18) for the values of the mean μ and standard deviation s of the sets of experimental strength data.

The Weibull parameters were derived from

μ and

s, using the 1st moment equations:

where

σl is the characteristic strength.The Weibull cumulative distribution function was calculated using the following equation:

The Weibull function was then validated by comparing the CDF to the reference normal distribution of experimental strength data.

8. Conclusion

Various original results were obtained in this paper on the flexural strength of fiber reinforced SiC/SiC, on its relation with tensile strength and with the strength of the critical filament that triggers failure of a fiber tow. The determination of flexural strengths of fiber reinforced composites is not straightforward, as the classical equation for homogeneous materials and elastic beams was found to significantly overestimate the SiC/SiC value by a factor of 2. The alternative approaches based on either finite element analysis or strain measurement as well as the predictions from tensile strength led to an estimate close to 340 MPa, slightly larger than the value obtained using tensile tests.

The scatter of flexural strengths was characterized satisfactorily by normal and Weibull distribution functions. It was attributed to the sources of variability identified on tensile tests i.e. the variability in the overloading of filaments governed by fiber/matrix interface characteristics. The strengths were related to scatter of critical filament strength around the theoretical value.

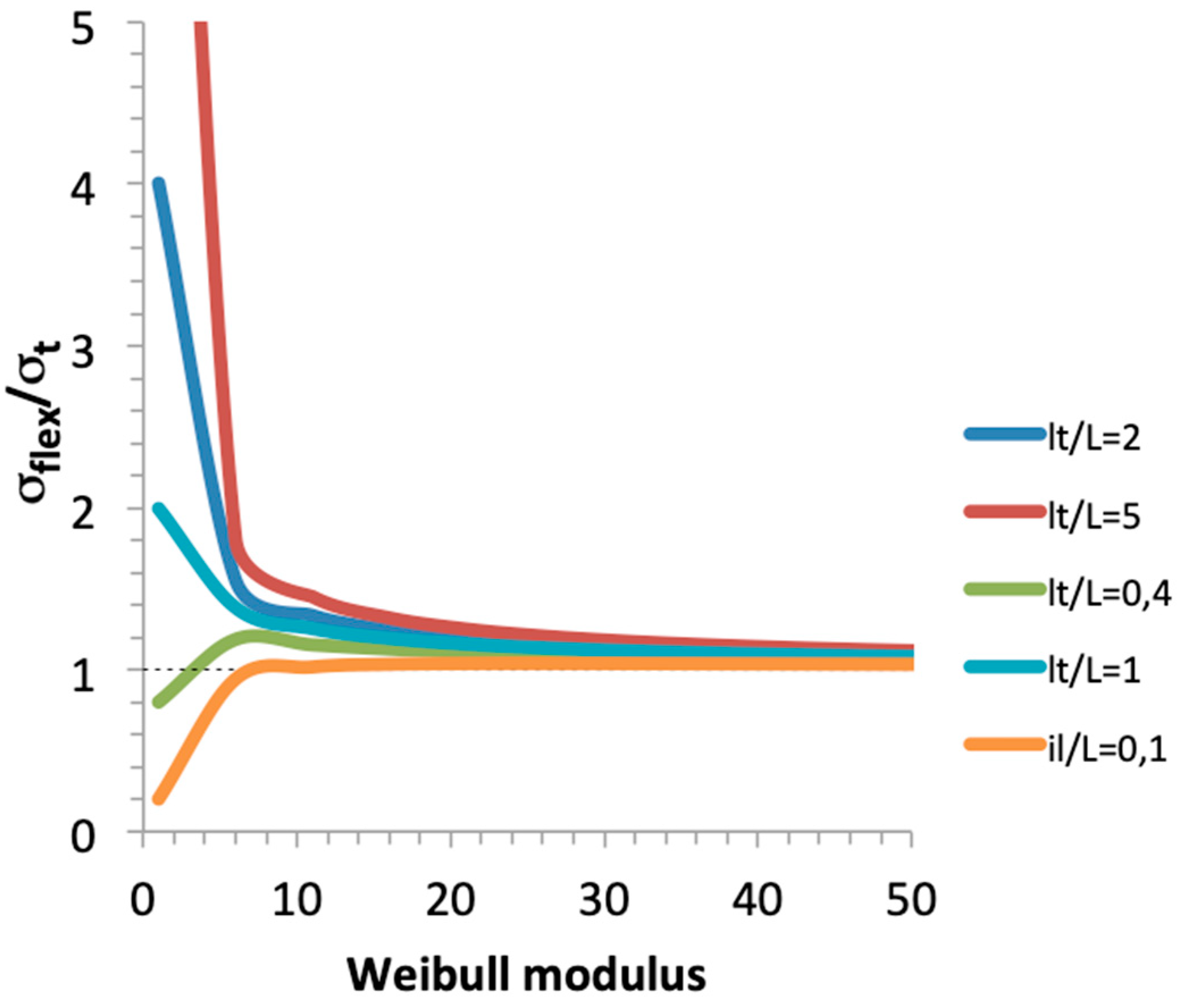

The flexural strengths were slightly larger than the tensile strengths, reflecting a limited specimen size effect. This size effect was attributed to the small equivalent stressed volume of flexural specimens, such that the gauge length was probably below the critical size when the full population of critical flaws is present. The relation between flexural and tensile strengths was satisfactorily predicted using the fiber tow based model. This model appears to be pertinent for those composites which fail from debonded tows after saturation of matrix cracking (which means that they didn’t experience premature failure).

From these results it can be anticipated that small flexural test specimens may be not appropriate for estimating tensile strengths, except when the flexural and tensile strengths follow a unique distribution function. A perequisite for this is to assess the validity of distribution functions using an unbiased approach like the p-quantile based method. Then the pertinence of prediction of tensile strengths will depend on the magnitude of Weibull modulus, as the Weibull modulus is expected to exhibit variability below a critical specimen size. Variability at high values will not affect the predictions. Because of these limitations, small flexural specimens cannot be recommended.

Bending tests on damage tolerant CMCs must be regarded as tests on components. A sophisticated analysis is required to derive stress data. By contrast, tensile testing is more appropriate to determine some generic properties that are useful for material evaluation or as input for models.

Figure 1.

Relative elastic modulus versus strain during tensile tests on 2D woven SiC/SiC composite [

1,

2].

Figure 1.

Relative elastic modulus versus strain during tensile tests on 2D woven SiC/SiC composite [

1,

2].

Figure 2.

The 3-point bending tests : (a) symmetric, (b) asymmetric tests.

Figure 2.

The 3-point bending tests : (a) symmetric, (b) asymmetric tests.

Figure 3.

Example of force stress-strain curve obtained experimentally using symmetric 3-point bending tests. Comparison with computed flexure behavior.

Figure 3.

Example of force stress-strain curve obtained experimentally using symmetric 3-point bending tests. Comparison with computed flexure behavior.

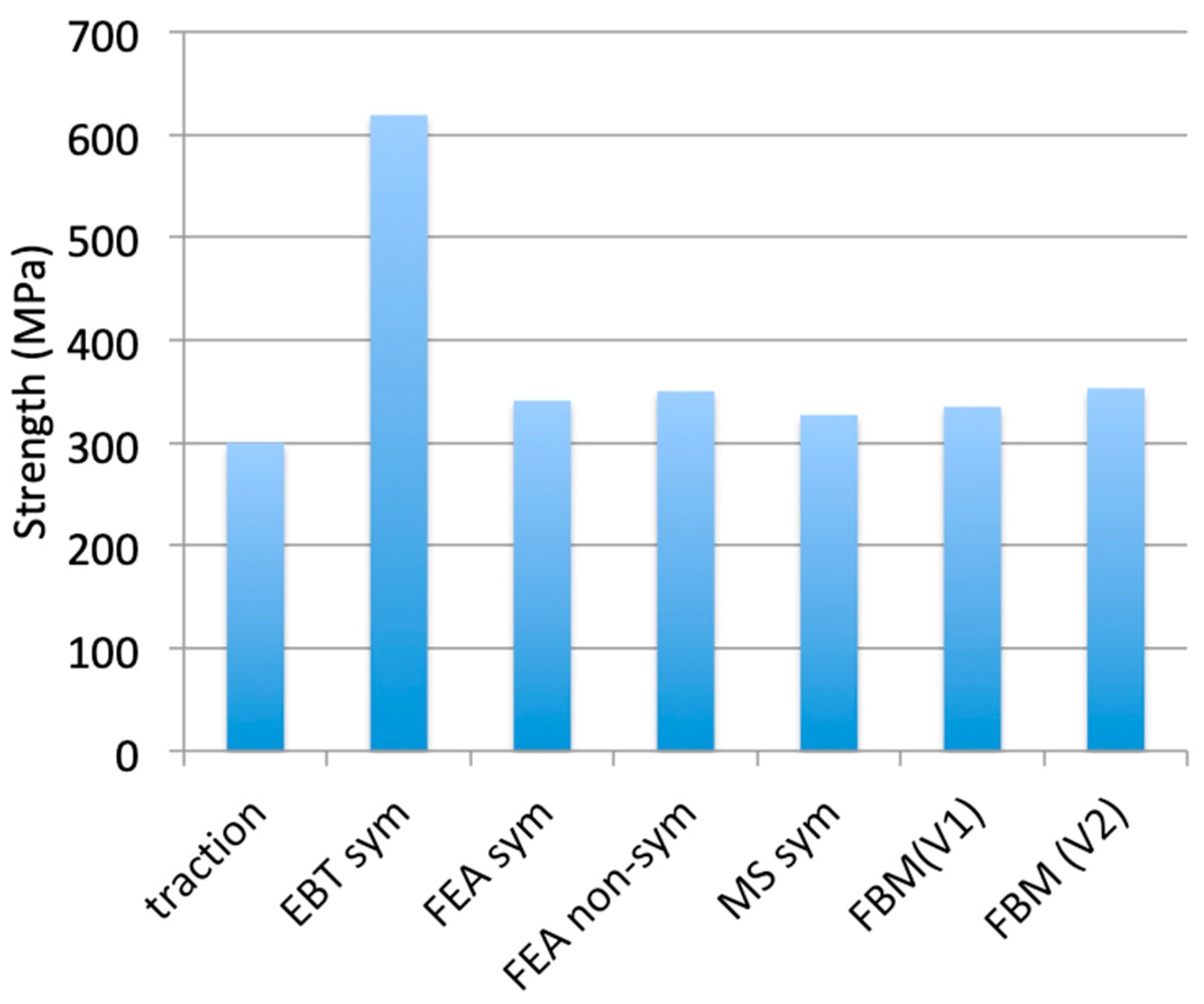

Figure 4.

Average values of flexural strengths determined using various methods: EBT (Elastic Beam Theory), FEA (Finite Element Analysis), MS (Measured Strain), FBM (Fiber Bundle Model). Also plotted is the strength measured using tensile test (traction).

Figure 4.

Average values of flexural strengths determined using various methods: EBT (Elastic Beam Theory), FEA (Finite Element Analysis), MS (Measured Strain), FBM (Fiber Bundle Model). Also plotted is the strength measured using tensile test (traction).

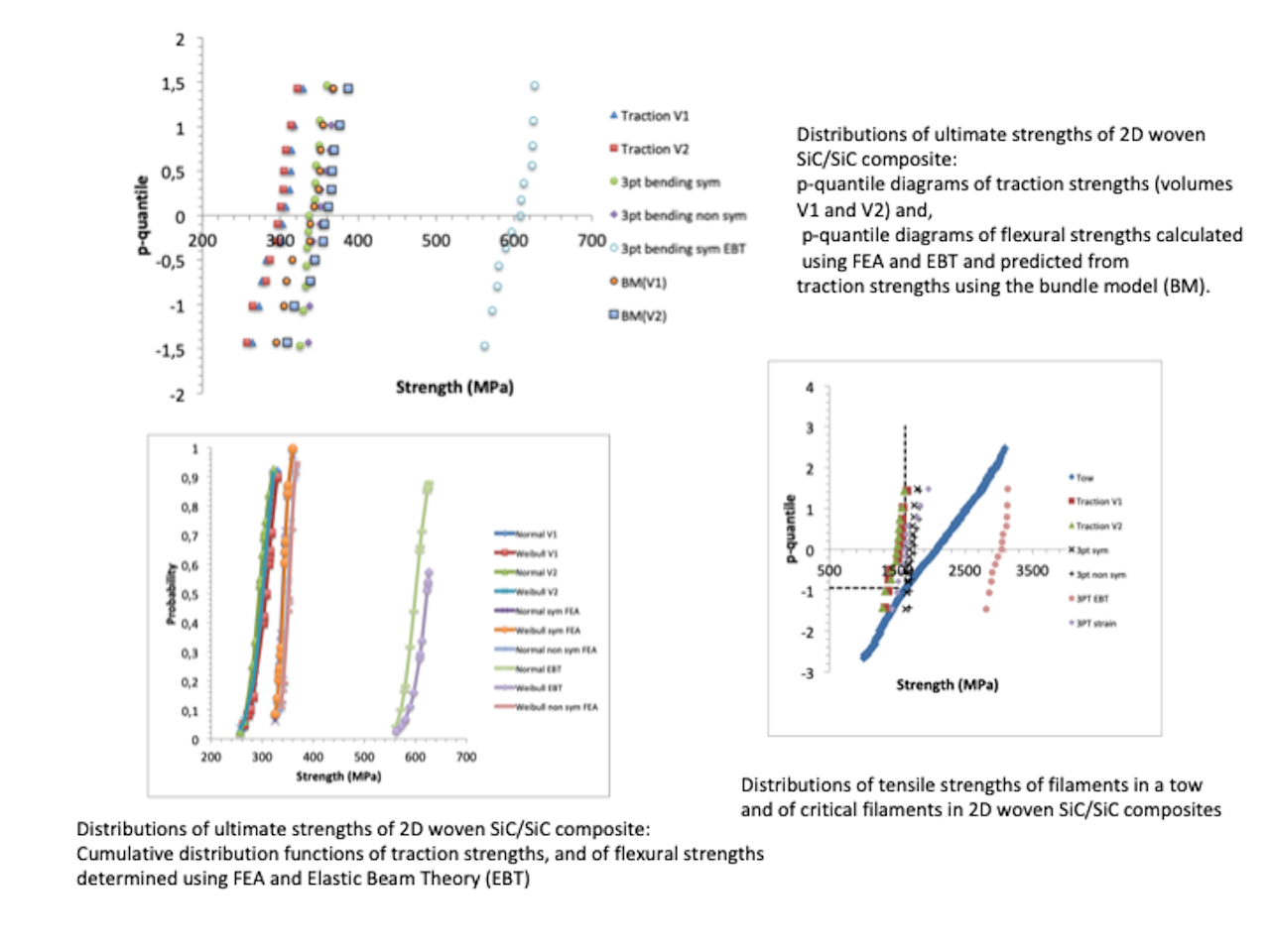

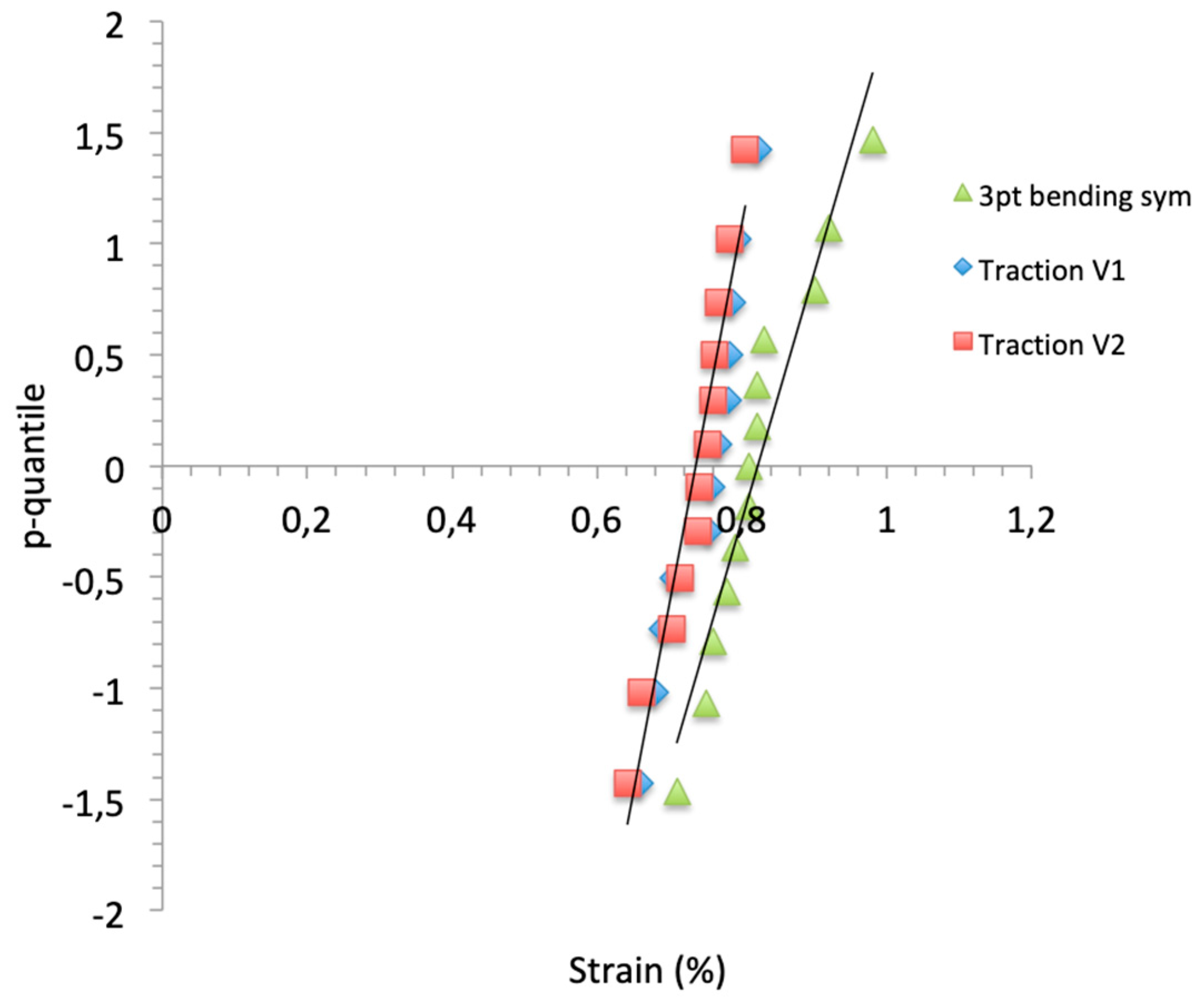

Figure 5.

Plots of p-quantiles vs. strengths in traction and in bending. BM(V1) and BM(V2) refer to strengths predicted using bundle model from tensile strengths of specimens having volume V1 or V2.

Figure 5.

Plots of p-quantiles vs. strengths in traction and in bending. BM(V1) and BM(V2) refer to strengths predicted using bundle model from tensile strengths of specimens having volume V1 or V2.

Figure 6.

Plots of p-quantile vs. strains-to-failure.

Figure 6.

Plots of p-quantile vs. strains-to-failure.

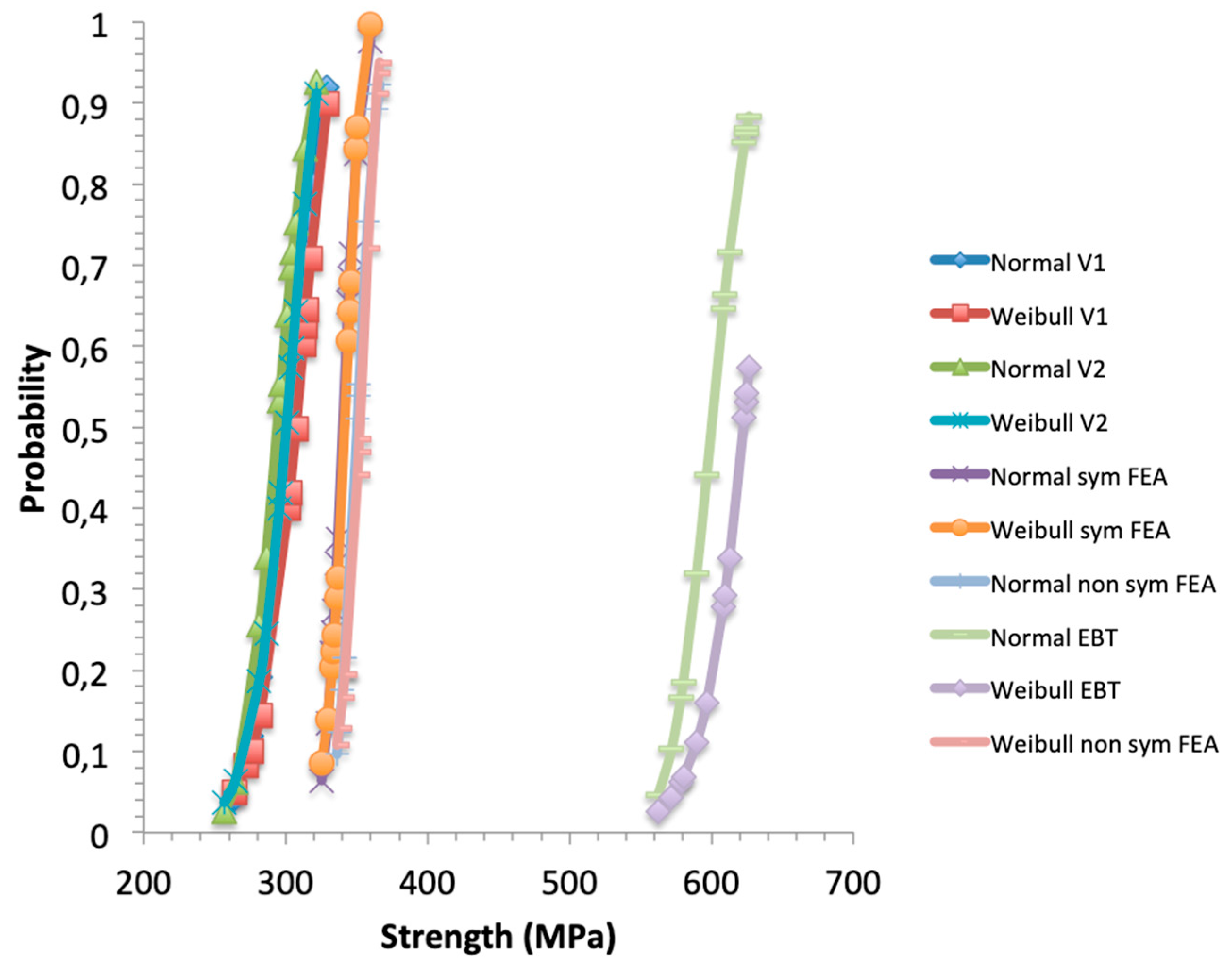

Figure 7.

Normal and Weibull cumulative distributions of traction (referred to as Normal V1 or V2, Weibull V1 or V2), and flexural strengths.

Figure 7.

Normal and Weibull cumulative distributions of traction (referred to as Normal V1 or V2, Weibull V1 or V2), and flexural strengths.

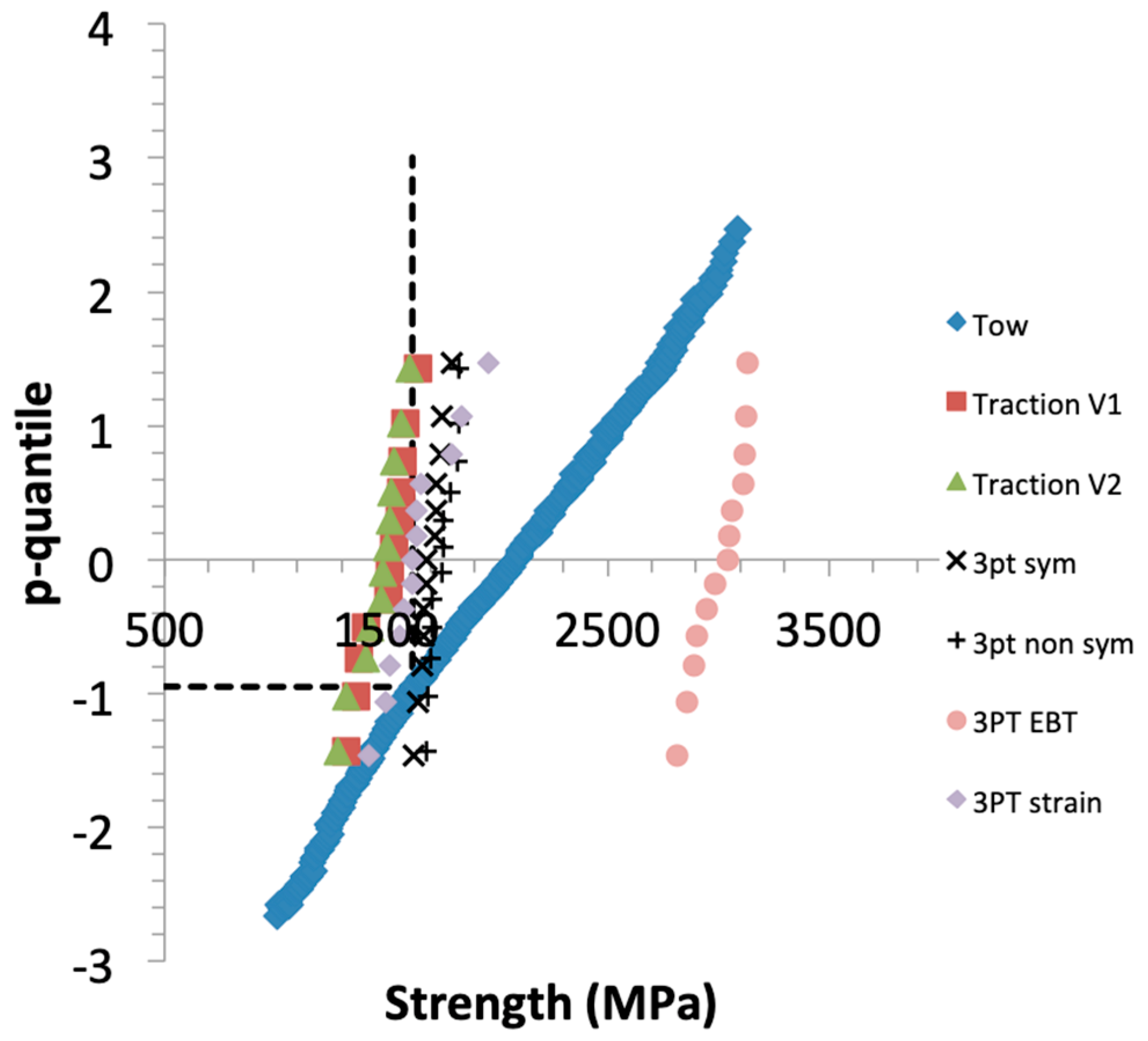

Figure 8.

Plot of filament strengths derived from a tow test, and filament strengths derived from composite strengths. Also indicated (dotted line) is the theoretical strength of a tow under loading at a constant stressing rate σf(P=αc).

Figure 8.

Plot of filament strengths derived from a tow test, and filament strengths derived from composite strengths. Also indicated (dotted line) is the theoretical strength of a tow under loading at a constant stressing rate σf(P=αc).

Figure 9.

Influence of composite Weibull modulus on ratio of flexural to tensile strengths, for various ratios of gauge/span lengths.

Figure 9.

Influence of composite Weibull modulus on ratio of flexural to tensile strengths, for various ratios of gauge/span lengths.

Table 1.

Values of experimental data used for the determination of the flexural strength.

Table 1.

Values of experimental data used for the determination of the flexural strength.

| E0 GPa |

Ef GPa |

Vf

|

εmeasured % |

εmax % |

L mm |

Filament Weibull modulus |

| 226 |

200 |

0.18 |

0.8 |

0.91 |

80 |

5.3 |

Table 2.

Average estimates of flexural ultimate strengths, and predictions using the equation (12) of bundle model. Also reported is the tensile strength.

Table 2.

Average estimates of flexural ultimate strengths, and predictions using the equation (12) of bundle model. Also reported is the tensile strength.

| |

Strength (MPa) |

Ratio σflex/σtraction |

| Traction |

300 |

|

3-pt symmetric

EBT equations |

619

|

2.06 |

3-pt symmetric

FE Analysis |

341

|

1.14 |

3-pt symmetric

Measured Strain (MPa) |

327 |

1.09 |

3-pt asymmetric

FE Analysis (MPa) |

350

|

1.17 |

| 3-pt prediction equation (12) (from traction V1) |

335

|

1.11 |

| 3-pt prediction equation (12) (from traction V2) |

353

|

1.17 |

Table 3.

Coefficients of correlation relative to p-quantiles-strengths diagrams, and normal vs Weibull CDF.

Table 3.

Coefficients of correlation relative to p-quantiles-strengths diagrams, and normal vs Weibull CDF.

| |

p-quantile vs strengths |

normal vs Weibull |

| Traction V1 |

0.96 |

0.98 |

| Traction V2 |

0.97 |

0.98 |

| 3pt symmetric FEA |

0.98 |

0.99 |

| 3pt nonsymmetric FEA |

0.97 |

0.99 |

| 3pt symmetric EBT |

0.99 |

0.97 |

Table 4.

Statistical parameters of composite strength distributions.

Table 4.

Statistical parameters of composite strength distributions.

| |

μMPa) |

s (MPa) |

mc |

σl (MPa) |

| Traction V1 |

300 |

20.74 |

17.3 |

313.8 |

| Traction V2 |

294 |

19.24 |

18.35 |

306.6 |

| 3pt symmetric FEA |

340.18 |

9.8 |

41.69 |

344.66 |

| 3pt nonsymmetric FEA |

350.34 |

11.09 |

37.9 |

355.67 |

| 3pt symmetric EBT |

600 |

22.22 |

32.42 |

629.63 |