Submitted:

27 April 2025

Posted:

28 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Resultats and Discussion

2.1. Dry Matter, Ash and Dietary Fiber Content

| Insoluble fiber fraction | Content (%) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| P. vulgare | C. nobile | O. forsskaolii | L. stoechas | |

| DM Ash NDF ADF ADL HC CC |

24.25 ± 0.04b 4.55 ± 0.01ab 48.23 ±0.70b 27.13± 0.11 b 14.58 ± 0.06a 33.65 ± 0.63b 12.55 ± 0.18c |

21.46 ± 0.03c 3.99 ± 0.01b 41.04± 0.99d 23.94 ±0.24c 6.72± 0.05bc 34.32 ±0.94b 17.22 ±0.19b |

19.87 ± 0.17c 3.67± 0.03b 43.48 ±0.41cd 26.46± 1.01b 7.92 ±0.50 b 35.56 ±0.09b 18.54 ± 0.50b |

27.49 ± 0.12a 6.11 ± 0.02a 62.39 ±0.71a 40.22±1.12a 5.65 ± 0.15c 56.74± 0.87a 34.5 ± 0.97a |

2.2. Extraction Yield, Phenolic Compounds' Content, and DPPH Activity

| Assay | P. vulgare | C. nobile | O. forsskaolii | L. stoechas |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Yield (%) Polyphenols (mg GAE/g DW Flavonoids (mgQE/g DW DPPH IC50 (mg/mL) |

12.42±0.37b 30.45±0.26c 9.03±0.24c 1.79±0.08a |

16.22±0.41a 73.88±0.79a 27.85±0.54a 0.38±0.002b |

17.04±0.85a 60.70±0.62b 19.25±0.20b 0.36± 0.006b |

16.44±0.62a 72.69±0.05a 20.11±0.12b 0.40±0.003b |

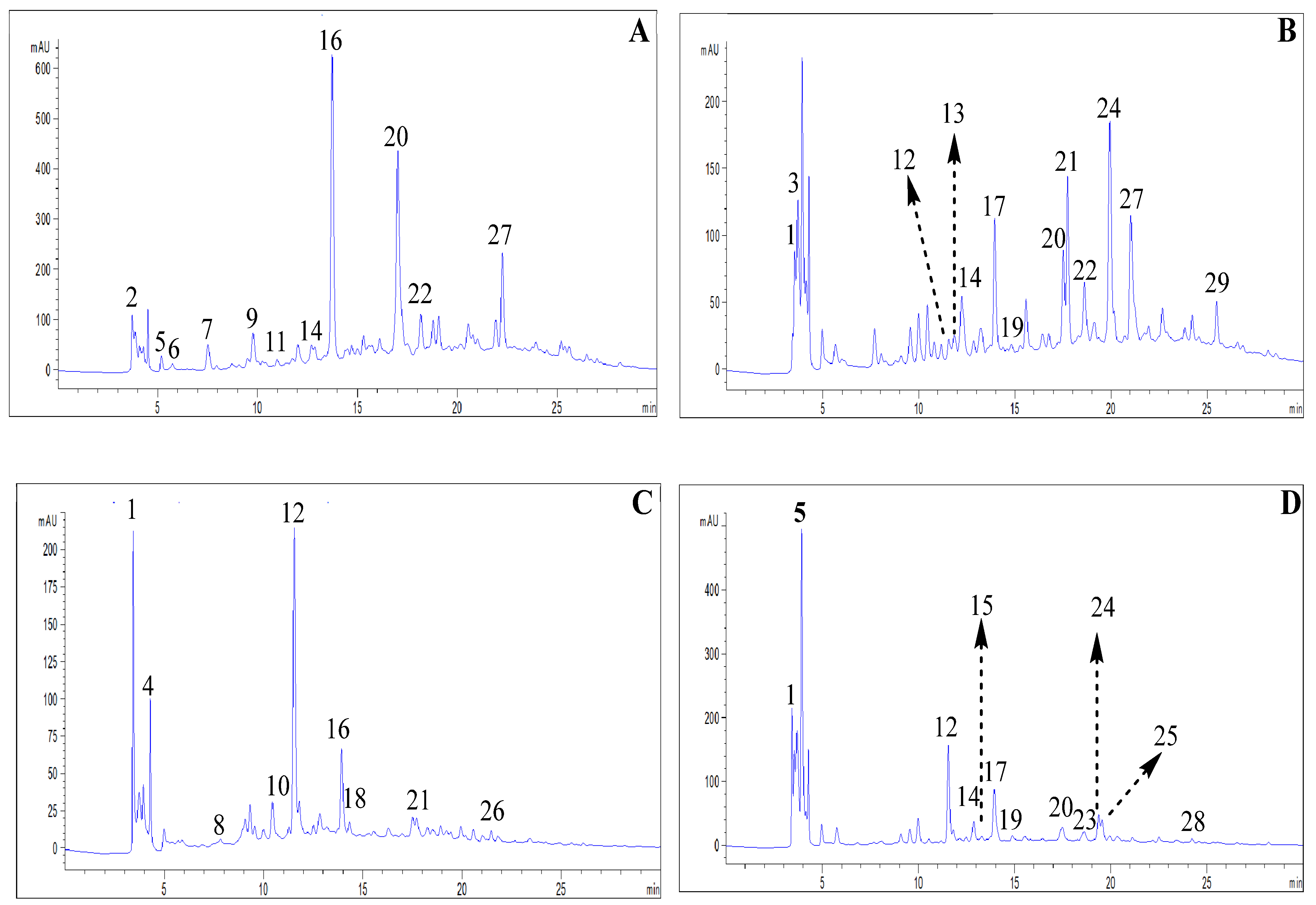

2.3. Compounds Profile Identified in the Aqueous Extract of P. vulgare; C. nobile, O. forsskaolii and L. stoechas

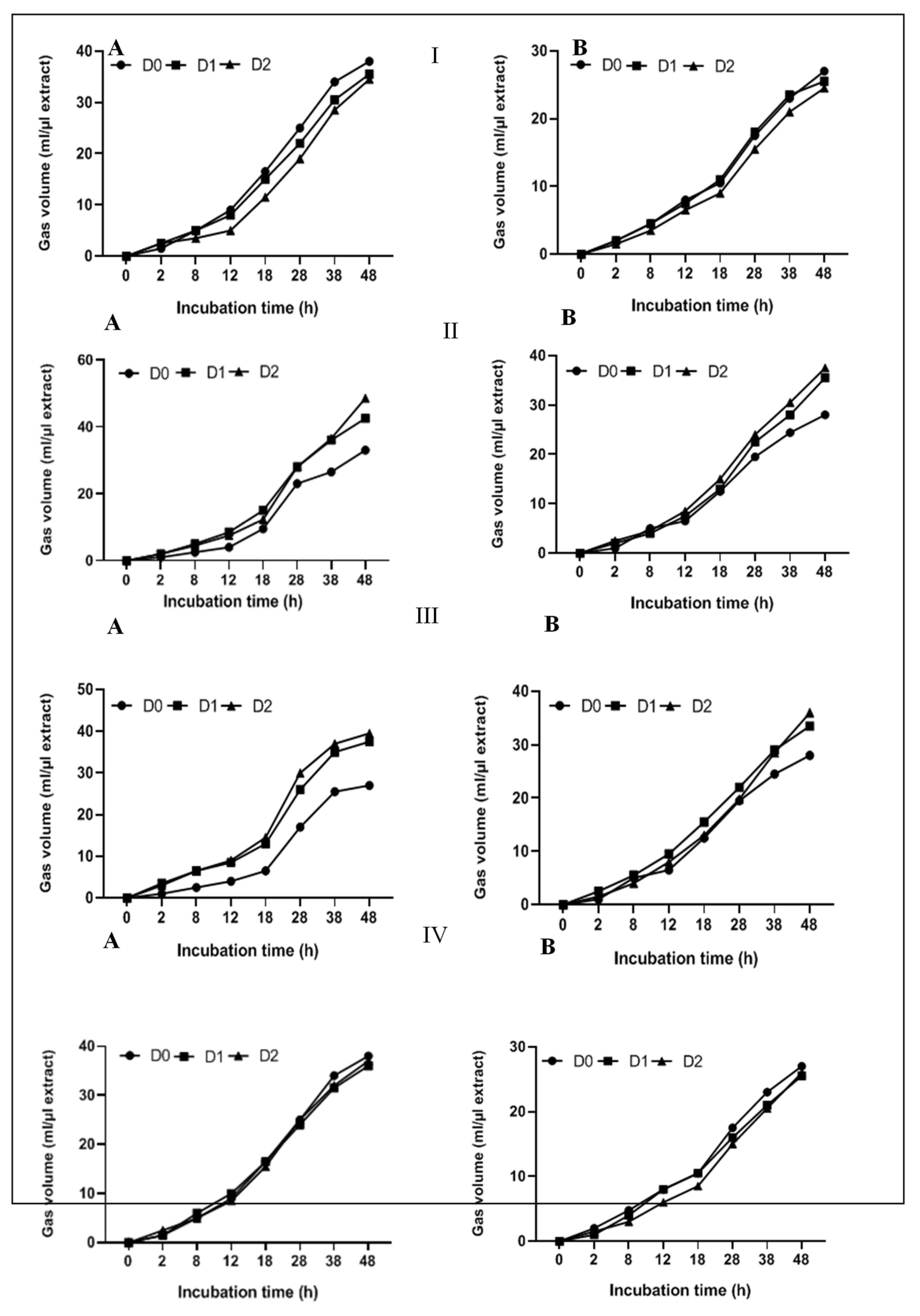

2.4. Effects of Plant Extracts on the In Vitro Kinetics of Gas Production

| Animals | Plants | Doses (µL) | a (mL/DW) |

b (mL/DW) |

c (mL/h) |

gas production (mL at 24 h) | gas production (mL at 48 h) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Sheep |

P. vulgare C. nobile O. forsskaolii L. stoechas |

D0 D10 D20 D0 D10 D20 D0 D10 D20 D0 D10 D20 |

1.98±0.05a 1.15±0.05b 1.49± 0.01b 1.49±0.01b 2.27±0.02a 2.73±0.01a 1.49±0.05b 1.65±0.07b 2.33±0.02a 1.98±0.05a 1.17±0.01b 1.83±0.05a |

104.1 ±0.08b 198.5±1.15a 105 ±0.95b 140.3 ±1.05c 256.43 ±0.46b 261.63 ±0.45a 140.3 ±1.05b 220.23 ±0.20a 219.7 ±0.17a 104.1±0.22b 85.06 ±0.31c 121.53±0.57a |

0.022b 0.032a 0.019b 0.016b 0.022a 0.018ab 0.028c 0.048b 0.055a 0.016 bc 0.022a 0.014 c |

23±1 ±1.08a 18.5 ±2.24b 15.5 ±2.16c 13.5 ±2.64b 24.5±2.06a 23.5 ±1.86a 13.5 ±2.12c 23.5 ±2.26b 26 ±1.18a 23 ±1.46a 21.5 ±1.76b 22 ±1.23ab |

34 ±0.56a 32 ±0.98ab 30 ±1.46b 31 ±2.51b 41 ±1.48a 42 ±2.26a 27 ±2.7c 35.5 ±0.98b 39.5 ±1.12a 33 ±1.8ab 34 ±2.7ab 35 ±2.3a |

||

| Plant effect Dose effect |

0.0038 0.0064 |

0.0006 0.0081 |

<0.0001 0.0067 |

<0.0001 <0.0001 |

<0.0001 <0.0001 |

||||

|

Goats |

P. vulgare C. nobile O. forsskaolii L. stoechas |

D0 D10 D20 D0 D10 D20 D0 D10 D20 D0 D10 D20 |

0.67±0.02b 0.83±0.03b 1.50±0.01a 1.36±0.03a 1.23±0.02a 1.01±0.05a 1.36±0.03a 1.06±0.21a 1.01±0.07a 1.07±0.09b 1.58±0.08a 1.58±0.06a |

93.36±0.08b 78.31±0.04c 165.83±0.98a 67.71±0.01c 172.56±0.23b 177.66±0.11a 67.71 ±0.22b 100.9±0.17a 33.63 ±0.41c 93.36 ±0.89bc 91.6 ±1.71c 96.69±0.64a |

0.072a 0.049b 0.022c 0.012b 0.004ab 0.005a 0.032a 0.028b 0.012c 0.028a 0.020b 0.022b |

14.5 ±0.89a 14.5 ±1.48a 12.5 b±1.16b 16.5 ±1.56c 18.5±1.76b 20±2.16a 16.5±1.34b 19±1.56a 17.5±1.84ab 14.5±2.06a 12.5±2.46b 12 ±1.42b |

25±1.68a 26±1.86a 22.5±2.13b 28 ±1.86c 35 ±2.49b 37±1.46a 27 ±1.56b 32 ±1.27a 33 ±1.15a 27±0.86a 26.5±1.96ab 25 ±1.92b |

||

| Plant effect Dose effect |

<0.0001 0.0006 |

0.002 0.0037 |

0.0002 <0.001 |

<0.0001 <0.0001 |

<0.0001 <0.0001 |

||||

2.5. In Vitro Impact of Plant Extracts on Ruminal Fermentation Parameters

| Plants | Doses | ME (MJ /kg DW) | OMd (%) | VFA (mmol) | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sheep | Goats | Sheep | Goats | Sheep | Goats | ||

|

P. vulgare C. nobile O. forsskaolii L. stoechas |

D0 D10 D20 D0 D10 D20 D0 D10 D20 D0 D10 D20 |

3.86 ±0.41b 5.47 ±0.2a 5.45 ±0.2a 4.18±0.76b 5.54 ±0.34a 5.54 ±0.34a 4.18 ±0.06b 5.54 ±0.87a 5.88 ±0.13a 4.22 ±0.4b 5.26 ±0.47ab 5.33±0.4a |

3.31±0.06b 4.31±0.06a 4.04±0.06ab 5.08±0.74a 4.67±1.94a 4.12 ±1.79a 4.58 ±0.34a 4.92 ±0.95a 4.77 ±0.88a 4.31±0.06a 5.04 ±0.06a 4.97 ±0.27a |

36.93 ±2.66b 42.93 ±1.33a 40.27 ±1.33ab 28.49 ±0.44b 37.38 ±2.22a 37.38±2.22a 28.49 ±0.44b 37.38±3.11a 39.60±0.88a 30.93±2.66b 35.60±3.11a 36.04±2.66a |

29.38±0.44a 29.38±0.44a 27.6±0.44a 31.15±2.22a 32.93±5.77a 34.27±5.33a 31.15±2.22a 33.38±6.22a 32.04±7.55a 29.38±0.44a 27.6±0.44a 27.15 ±1.77a |

0.38 ±0.03b 0.48±0.07a 0.41±0.03b 0.26±0.01b 0.50±0.06a 0.50±0.06a 0.26 ±0.01b 0.50±0.08a 0.56±0.2a 0.42±0.07b 0.57±0.14a 0.56 ±0.07a |

0.28±0.01a 0.28±0.01a 0.23±0.01a 0.33±0.05b 0.38 ±0.15ab 0.40±0.16a 0.33±0.06a 0.39±0.17a 0.35±0.20a 0.28±0.011a 0.23±0.14a 0.22±0.05a |

| Plant effect Dose effect |

0.028 0.0476 |

0.1602 0.6423 |

0.0155 0.0307 |

0.4968 0.101 |

0.0192 0.04 |

0.4968 0.101 |

|

3. Materiel and Methods

3.1. Plant Material

3.2. Animal Material

3.3. Phytochemical Analysis

3.3.1. Dry Matter, Ash and Dietary Fiber Determination

3.3.2. Preparation and Yield of Plant Extracts

3.3.3. Total Polyphenols Détermination

3.3.4. Total Flavonoids Determination

3.3.5. Antioxidant Activity

3.3.6. HPLC Analysis of Plant Aqueous Extracts

3.4. Evaluation of Gas Production In Vitro

3.5. In Vitro Fermentation Parameters

3.6. Statistical Analysis

4. Conclusion

Author Contributions

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. Estimations des émissions de gaz à effet de serre en agriculture : Un manuel pour répondre aux exigences de données des pays en développement; Organisation des Nations Unies pour l'alimentation et l'agriculture. 2015. https://openknowledge.fao.org/items/49ce77d7-499f-49f0-a254-e2210235eaa8.

- Agriculture Victoria. Livestock methane and nitrogen emissions; Agriculture Victoria. 2024. https://agriculture.vic.gov.au.

- Climate and Clean Air Coalition (CCAC). Enteric fermentation and methane reduction; CCAC Coalition. 2024. https://www.ccacoalition.org.

- Patra, A.; Park, T.; Kim, M.; Yu, Z. Rumen methanogens and mitigation of methane emission by anti-methanogenic compounds and substances. J. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. 2017, 8, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, H.; Tan, S.; Chen, S.; Wu, Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, H.; et al. Effects of fermented Yupingfeng on intramuscular fatty acids and ruminal microbiota in Qingyuan black goats. Anim. Sci. J. 2021, 92, 13554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aziz, S.; Ölmez, M.; Nazir, R.; Mobashar, M.; Iqbal, Z.; Naeem, M.I.; Muzaffar, H.A.; Saif, D.; Faizan, M.; Kamran, M. Herbal feed additives for ruminant nutrition. In Abbas, R.Z.; Akhtar, T., Asrar, R., Khan, A.M.A., Saeed, Z., Eds.; Complementary and Alternative Medicine: Feed Additives; Unique Scientific Publishers: Faisalabad, Pakistan, 2024; pp. 15–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouzazi, M.; Tajini, F.; Selmi, H.; Ouerghui, A.; Sebai, H. Ethno-Veterinary Survey on the Traditional Use of Medicinal Plants with Therapeutic Properties in the Northwestern Regions of Tunisia. IOSR J. Agric. Vet. Sci. 2025, 18, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farràs, A.; Mitjans, M.; Maggi, F.; Caprioli, G.; Vinardell, M. P.; López, V. Polypodium vulgare L. (Polypodiaceae) as a source of bioactive compounds: Polyphenolic profile, cytotoxicity, and cytoprotective properties in different cell lines. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 727528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sah, A.; Naseef, P.P.; Kuruniyan, M.S.; Jain, G.K.; Zakir, F.; Aggarwal, G. A Comprehensive Study of Therapeutic Applications of Chamomile. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alharbi, A.A. In vitro and in vivo anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and antioxidant activity of Dhimran (Ocimum forsskaolii Benth) extract and essential oil on carbon tetrachloride-induced hepatotoxicity in mice. Kafkas Univ Vet Fak Derg 2024, 30(5), 729–740. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domingues, P.; Silva, A.; Mendes, F.; Rodrigues, A. Vanillic acid in L. stoechas and its biological activity. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2023, 71(9), 2035–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dupont, J.; Martin, P. Study of insoluble fibers in Mediterranean plants: Comparison between Asteraceae. J. Medit. Bot. 2017, 24(3), 145–157. [Google Scholar]

- George, C.F.; Lawrence, N.; Brian, L.; David, R.M. Critical Factors in Determining Fiber Content of Feeds and Foods and Their Ingredients. J. AOAC Int. 2019, 102, 52–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sebastian, D.M.; Kim, L.J.; Walter, G.; Sonja, de V. Insoluble fibers affect digesta transit behavior in the upper gastrointestinal tract of growing pigs, regardless of particle size. J. Anim. Sci. 2023, 101, 299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chuang, W.-Y.; Lin, L.-J.; Shih, H.-D.; Shy, Y.-M.; Chang, S.-C.; Lee, T.-T. The potential utilization of high-fiber agricultural by-products as monogastric animal feed and feed additives: A review. Animals 2021, 11, 2098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ez Zoubi, Y.; Bousta, D.; Farah, A. A phytopharmacological review of a Mediterranean plant: Lavandula stoechas L. Clin. Phytosci. 2020, 6, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Polcaro, L.M.; Cerulli, A.; Montella, F.; Ciaglia, E.; Masullo, M.; Piacente, S. Chemical Profile and Antioxidant and Tyrosinase Inhibitory Activity of Chamaemelum nobile L. Green Extracts. Cosmetics 2024, 11, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, F.; Nainesh, R.M. Estimation of total phenolic content in selected varieties of Ocimum species grown in different environmental conditions. J. Pharmacogn. Phytochem. 2018, 7(5), 144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Zongo, E.; Busuioc, A.; Meda, R.N.T.; Botezatu, A.V.; Mihaila, M.D.; Mocanu, A.M.; Avramescu, S.M.; Koama, B.K.; Kam, S.E.; Belem, H.; et al. Exploration of the antioxidant and anti-inflammatory potential of Cassia sieberiana DC and Piliostigma thonningii (Schumach.) Milne-Redh, traditionally used in the treatment of hepatitis in the Hauts-Bassins region of Burkina Faso. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tajini, F.; Jelassi, A.; Hamdani, A.; Salem, A.; Abdelhedi, O.; Ouerghui, A.; Sebai, H. Antioxidant Activities and Laxative Effect of Bioactive Compounds from Cynara cardunculus var. sylvestris. Sains Malays. 2024, 53(7), 1617–1630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, X.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Liu, J. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties of quercetin and rutin in C. nobile extracts. nobile extracts. Phytochem. Rev. 2023, 22(2), 223–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndhlala, A.R.; Işık, M.; Kavaz Yüksel, A.; Dikici, E. Phenolic Content Analysis of Two Species Belonging to the Lamiaceae Family: Antioxidant, Anticholinergic, and Antibacterial Activities. Molecules 2024, 29(2), 480. [CrossRef]

- Orskov, E.R.; Macdonald, I. The estimation of protein degradability in the rumen from incubation measurements weighted according to rate of passage. J. Agric. Sci. Camb. 1979, 92, 499–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freitas, R.S.X.d.; da Silva, J.S.; Furtado, A.J.; Perna Junior, F.; de Oliveira, A.L.; Bueno, I.C.d.S. The production of Marandu grass (Urochloa brizantha) extracts as a natural modifier of rumen fermentation kinetics using an in vitro technique. Fermentation 2024, 10, 447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez Ronquillo, M.; Ghavipanje, N.; Sainz-Ramírez, A.; Danaee Celis-Alvarez, M.; Andrea Plata-Reyes, D.; Robles Jimenez, L.E.; Vargas-Bello Perez, E. Effects of plant extracts on in vitro gas production kinetics and ruminal fermentation of four fibrous feeds: towards sustainable animal diets. Chil. J. Agric. Anim. Sci. 2023, 39(3), 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferchichi, A.; Ben Salem, H.; Makkar, H.P.S.; Fodelianakis, S. Influence of phenolic-rich plants on in vitro ruminal fermentation and methane production. Anim. Feed Sci. Technol. 2019, 248, 138–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; et al. Effects of plant polyphenols on rumen fermentation and microbial composition: A review. J. Anim. Sci. 2020, 6(4), 481–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Messaoudi, Z.; El Gharbi, S.; Khammassi, S. Antioxidant and antimicrobial properties of Lavandula stoechas extracts and their effect on ruminant digestion. Environ. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2018, 63, 21–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moghaieb, R.; El-Hack, M.E.A.; Abdelnour, S.A.; Rady, M.O. Incorporation of plant extracts into ruminant diets: Effects on fermentation and digestibility. J. Appl. Anim. Res. 2020, 48(1), 45–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khelil, H.; Amrouche, N.; Ben Salem, H. Impact of plant secondary metabolites on ruminal fermentation and productivity in small ruminants under hot climatic conditions. Afr. J. Agric. Res. 2020, 15(8), 1184-1191. [CrossRef]

- Khouja, M.L.; Boussaid, M. Use of medicinal plants for small ruminants in arid regions. J. Arid Environ. 2013, 96, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Zhang, G.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Y. Effects of high forage/concentrate diet on volatile fatty acid production and the microorganisms involved in VFA production in cow rumen. Animals 2020, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antonius, A.; Pazla, R.; Putri, E.M.; Alma'I, M.I.; Laconi, E.B.; Diapari, D.; Jayanegara, A.; Ardani, L.R.; Marlina, L.; Purba, R.D.; Gopar, R.A.; Negara, W.; Asmairicen, S.; Negoro, P.S. Effects of herbal plant supplementation on rumen fermentation profiles and protozoan population in vitro. Vet. World 2024, 17(5), 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wang, X.; Dai, C.; Tang, W.; Li, J.; Huang, P.; Li, Y.; Ding, X.; Huang, J.; Hussain, T.; Yang, H.; Zhu, M. Effects of dietary energy levels on rumen fermentation, microbiota, and gastrointestinal morphology in growing ewes. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8(12), 6621–6632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Hassan, F.; Peng, L.; Xie, H.; Liang, X.; Huang, J.; Huang, F.; Guo, Y.; Yang, C. Mulberry flavonoids modulate rumen bacteria to alter fermentation kinetics in water buffalo. PeerJ 2022, 10, e14309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowland, I.; Gibson, G.; Heinken, A.; Scott, K.; Swann, J.; Thiele, I.; Tuohy, K. Gut microbiota functions: metabolism of nutrients and other food components. Eur. J. Nutr. 2017, 57(1), 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Soest, P.J.; Robertson, J.B.; Lewis, B.A. Method for dietary fiber, neutral detergent fiber, and nonstarch polysaccharides in relation to animal nutrition. J. Dairy Sci. 1991, 74, 3583–3597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Olsen, S.R.; Sommer, L.E. Phosphorus. Chem. Microbiol. Prop. 1982, 9, 403p. Am. Soc. Agron., Soil Sci. Soc. Am., Madison.

- Tajini, F.; Boualy, Y.; Ouerghui, A. Study of the Nutritional Quality of Phoenix dactylifera L. fruit: Measurement of Biochemical Parameters. Rev. Nat. Technol. 2020, 12(2), 39-49.

- Sarr, S.O.; Fall, A.D.; Gueye, R.; Diop, A.; Sene, B.; Diatta, K.; Ndiaye, B.; Diop, Y.M. Evaluation de l’activité antioxydante des extraits des feuilles de Aphania senegalensis (Sapindaceae) et de Saba senegalensis (Apocynaceae). Int. J. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2015, 9, 2676–2684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Falleh, H.; Ksouri, R.; Chaieb, K.; Karray-Bouraoui, N.; Trabelsi, N.; Boulaaba, M.; Abdelly, C. Phenolic composition of Cynara cardunculus L. organs, and their biological activities. C. R. Biol. 2008, 331, 372–379. [CrossRef]

- Jedidi, S.; Selmi, H.; Aloui, F.; Rtibi, K.; Jridi, M.; Chaâbane, A.; Sebai, H. Comparative studies of phytochemical screening, HPLC-PDA-ESI-MS/MS-LC-HRESIMS analysis, antioxidant capacity, and in vitro fermentation of officinal sage (Salvia officinalis L.) cultivated in different biotopes of Northwestern Tunisia. Chem. Biodivers. 2019, 10, 1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menke, K.H.; Steingass, H. Estimation of the energetic feed value obtained from chemical analysis and in vitro gas production using rumen fluid. Anim. Res. Dev. 1988, 28, 7–55. [Google Scholar]

| Peaks numbers | Compoundsa | RTb | P. vulgare | C. nobile | O. forsskaolii | L. stoechas |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 |

Ascorbic acid Shikimic acid Apigenine-7-O-glucoside Apigenin Gallic acid 5-O-caffeoylquinic acid 3-O-caffeoylquinic acid Rosmarinic acid Hyperoside Kaempferol 3,5-Dicaffeoylquinic acid Chlorogenic acid Résorcinol Catechin Vanillic acid Catechol Epicatechin Syringic acid Cafeic acid Ellagic acid Luteolin Sinapic acid p-Coumaric acid Ferulic acid m-Coumaric acid Quercetin Myricetin Cinnamic acid Ferulic-1-O-glucoside acid |

3.69 3.71 3.93 4.29 5.18 5.74 7.51 7.83 9.77 10.44 10.98 11.50 11.84 12.70 13.29 13.73 13.94 14.32 14.88 17.02 17.74 18.17 18.61 19.36 19.55 21.80 22.26 24.22 25.49 |

- 2.52 - - 0.88 0.50 2.29 - 2.75 - 0.41 - - 1.37 - 22.12 - - - 20.59 - 3.68 - - - - 6.89 - - |

5.81 - 9.39 - - - - - - - - 0.99 1.31 3.92 - - 5.80 - 0.34 3.92 6.83 3.13 - 10.42 - - 7.56 - 1.79 |

14.22 - - 6.89 - - - 1.06 - 3.76 - 23.53 - - - 7.63 - 1.17 - - 1.97 - - - - 0.51 - - - |

9.44 - - 21.40 - - - - - - - 10.30 - 2.56 0.66 - 7.63 - 0.73 2.65 - - 1.94 3.02 2.45 - - 0.41 - |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).