Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Results

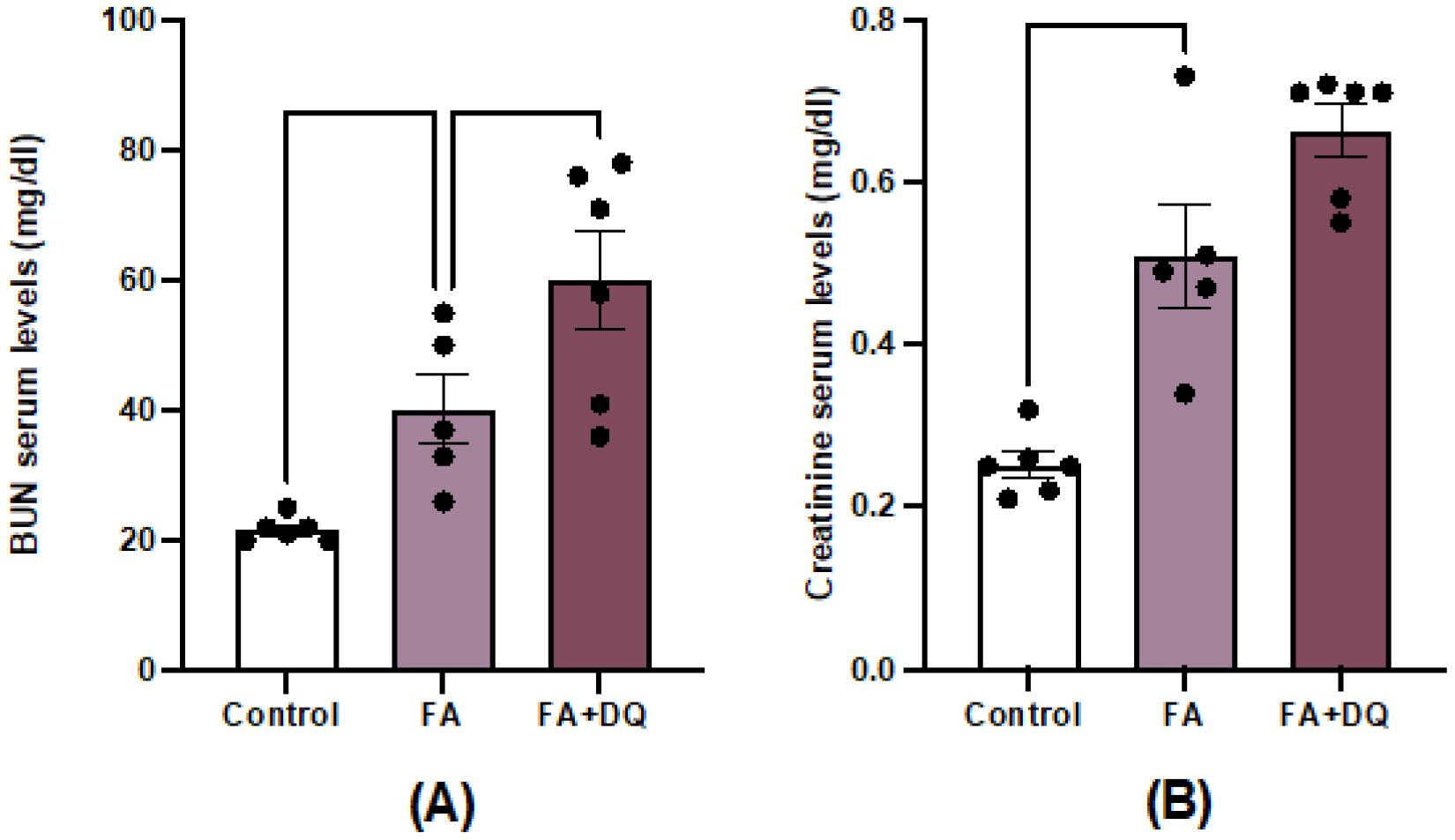

2.1. Treatment with Dasatinib Plus Quercetin Did Not Prevent Renal Dysfunction in AKI-FAN

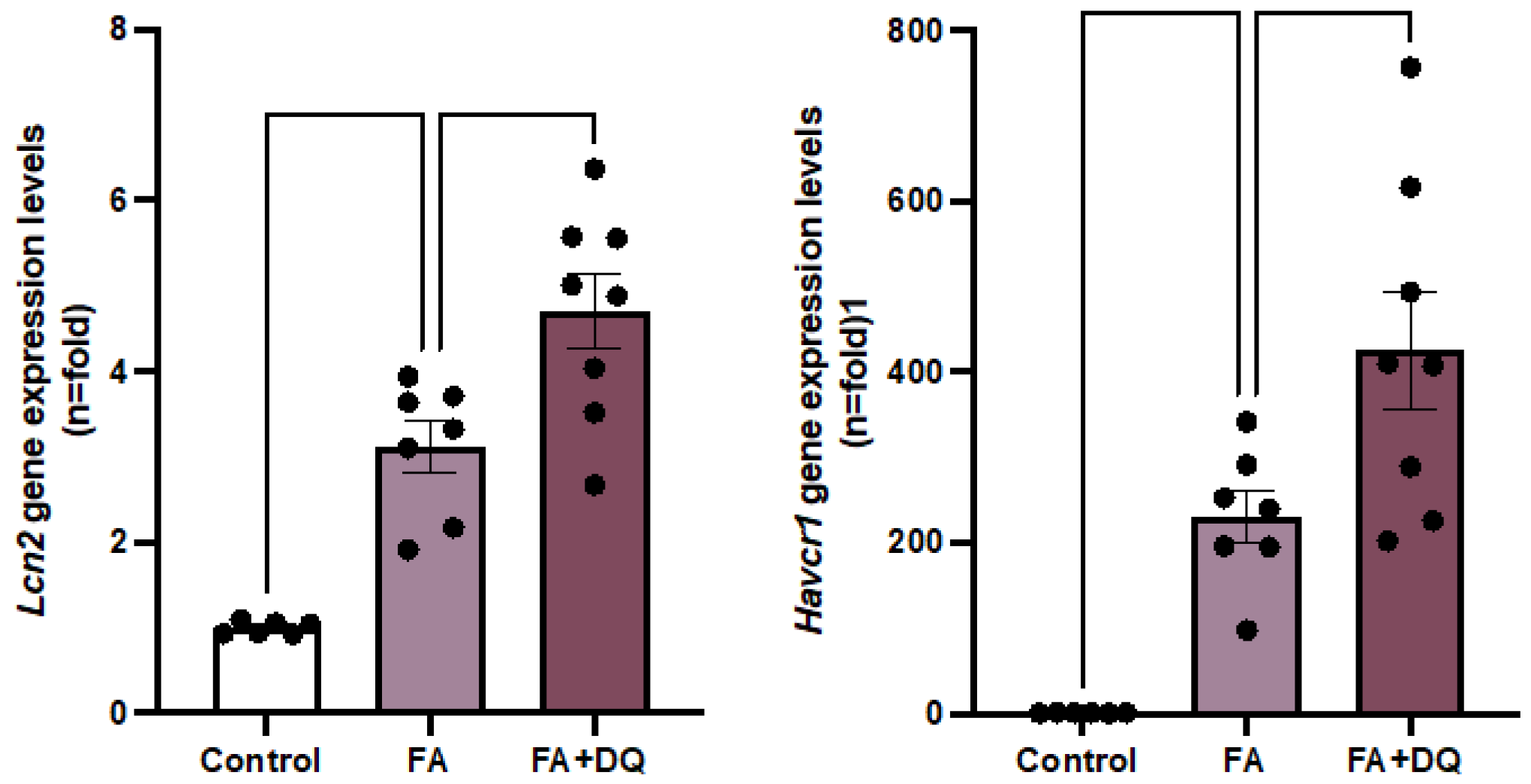

2.2. Dasatinib Plus Quercetin Increased the Gene Expression of Kidney Damage Biomarkers in AKI-FAN

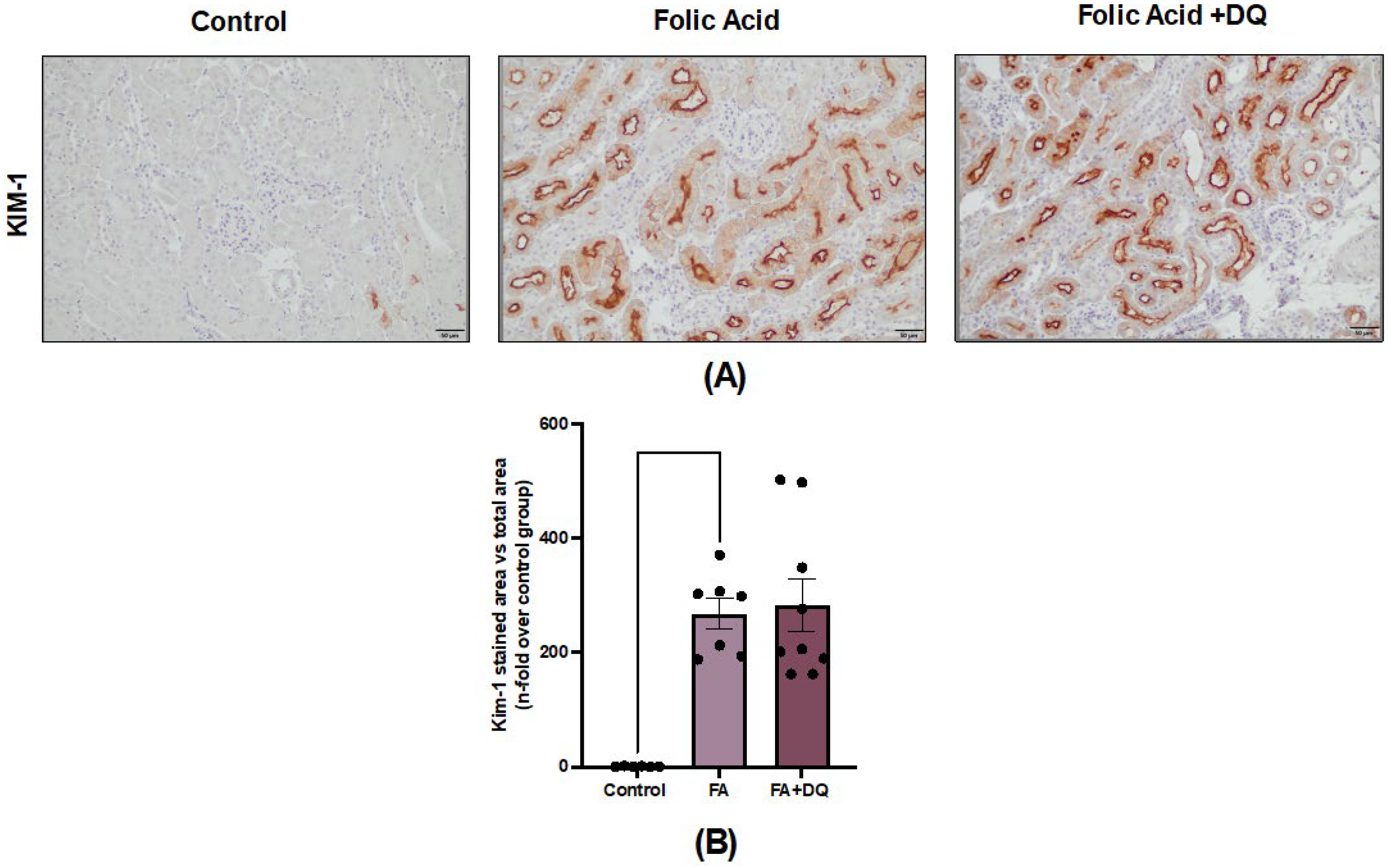

2.3. Dasatinib and Quercetin Did Not Modify the Tubular Damage Marker KIM-1 in AKI-FAN

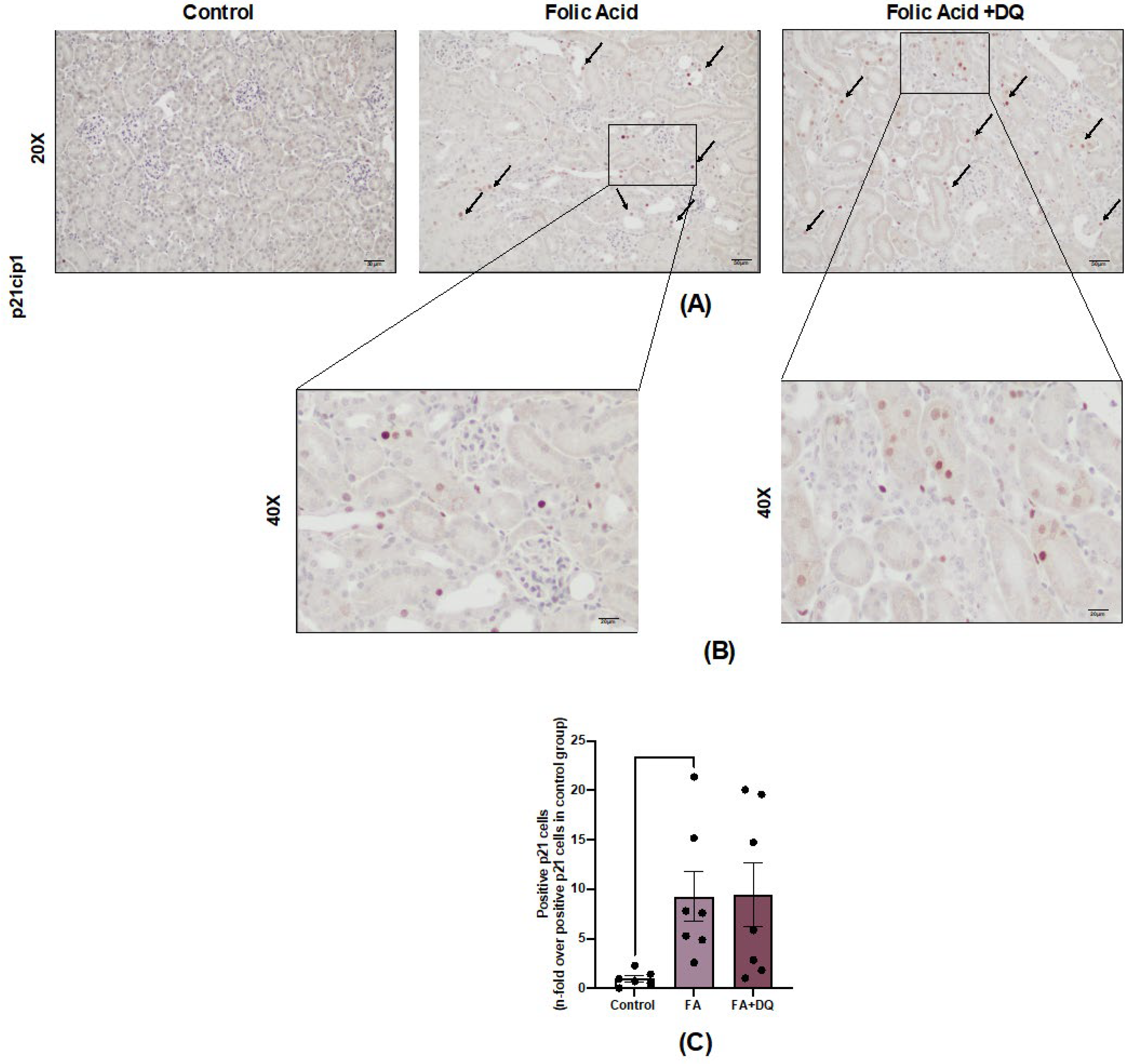

2.4. Dasatinib Plus Quercetin Did Not Modify the Number of Senescent Cells in AKI-FAN

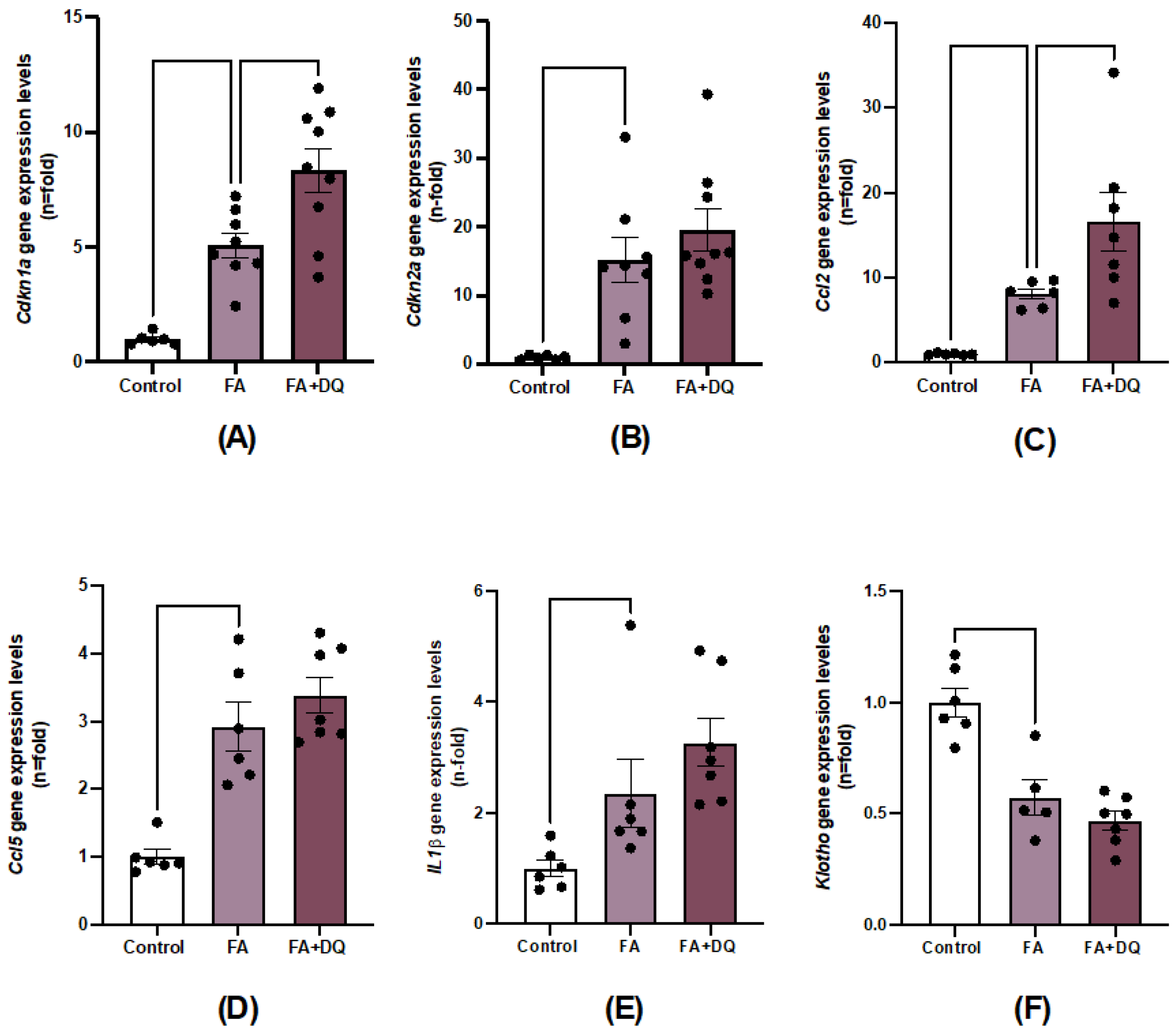

2.5. Dasatinib Plus Quercetin and Senescence-Associated Biomarkers

2.6. Dasatinib Plus Quercetin Did Not Increase Apoptosis during AKI-FAN

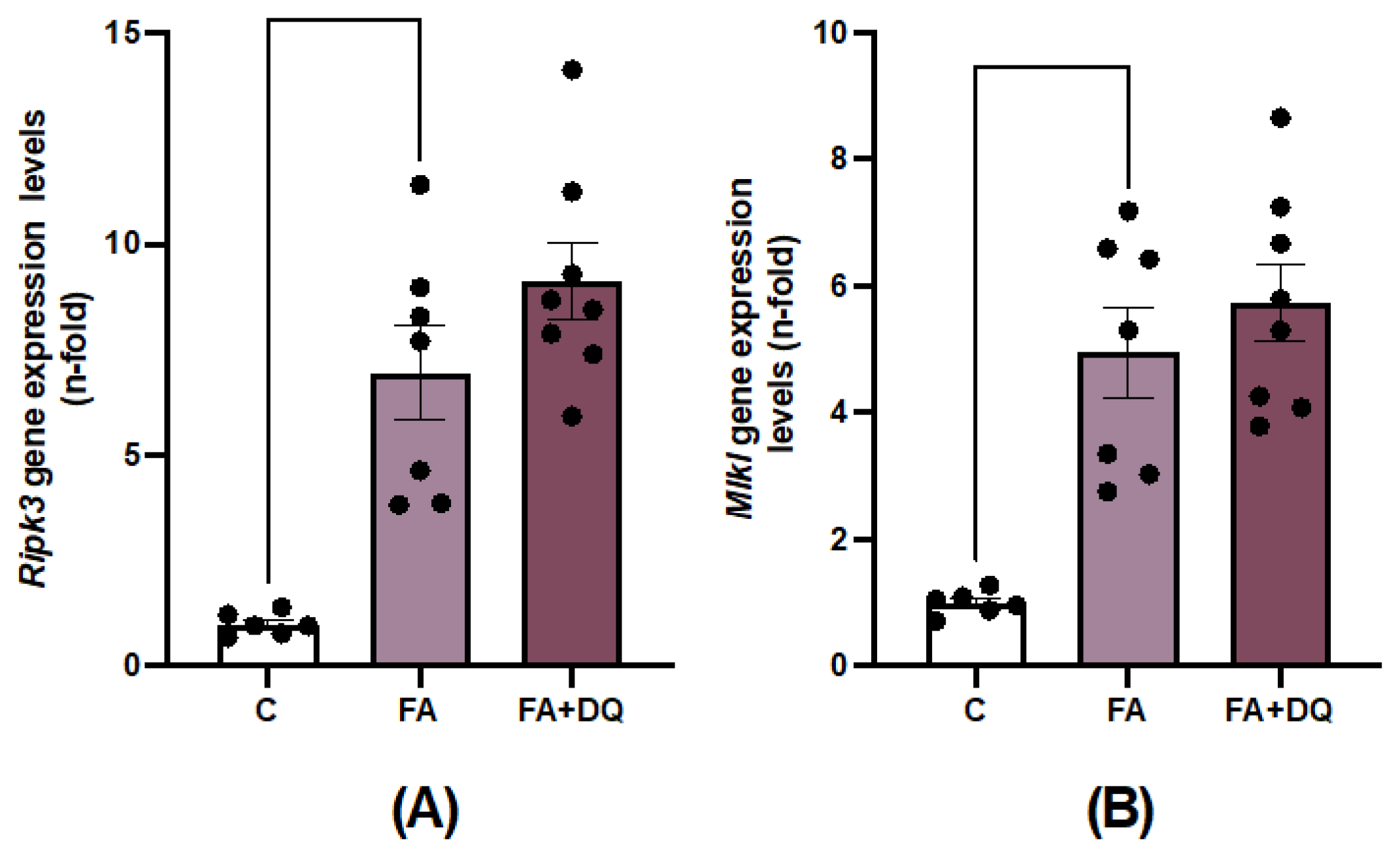

2.7. Dasatinib Plus Quercetin Did Not Modify Necroptosis Pathway Activation in AKI-FAN

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Animals

4.2. Folic acid Model (AKI-FAN)

4.3. Gene Expression Studies

4.4. Immunohistochemistry

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AKI | Acute Kidney Injury |

| CKD | Chronic Kidney disease |

| D&Q | Dasatinib (D) and Quercetin (Q) |

| SASP | Senescence-associate secretory phenotype |

References

- Rodrigues FB, Bruetto RG, Torres US, Otaviano AP, Zanetta DMT, Burdmann EA. Incidence and Mortality of Acute Kidney Injury after Myocardial Infarction: A Comparison between KDIGO and RIFLE Criteria. PLoS One 2013;8. [CrossRef]

- Gameiro J, Fonseca JA, Outerelo C, Lopes JA. Acute kidney injury: From diagnosis to prevention and treatment strategies. J Clin Med 2020;9. [CrossRef]

- Havaldar AA, Sushmitha EAC, Shrouf S Bin, H. S M, N M, Selvam S. Epidemiological study of hospital acquired acute kidney injury in critically ill and its effect on the survival. Sci Rep 2024;14. [CrossRef]

- Tamargo C, Hanouneh M, Cervantes CE. Treatment of Acute Kidney Injury: A Review of Current Approaches and Emerging Innovations. J Clin Med 2024;13. [CrossRef]

- Gameiro J, Fonseca JA, Outerelo C, Lopes JA. Acute kidney injury: From diagnosis to prevention and treatment strategies. J Clin Med 2020;9. [CrossRef]

- Mehta RL, Cerdá J, Burdmann EA, Tonelli M, García-García G, Jha V, Susantitaphong P, Rocco M, Vanholder R, Sever MS, Cruz D, Jaber B, Lameire NH, Lombardi R, Lewington A, Feehally J, Finkelstein F, Levin N, Pannu N, Thomas B, Aronoff-Spencer E, Remuzzi G. International Society of Nephrology’s 0by25 initiative for acute kidney injury (zero preventable deaths by 2025): A human rights case for nephrology. The Lancet 2015;385:2616–43. [CrossRef]

- Negi S, Wada T, Matsumoto N, Muratsu J, Shigematsu T. Current therapeutic strategies for acute kidney injury. Ren Replace Ther 2023;9. [CrossRef]

- Ortiz A, Roger M, Jiménez VM, Perez JCR, Furlano M, Montero AM, Pérez NM, et al. RICORS2040: The need for collaborative research in chronic kidney disease. Clin Kidney J 2022;15:372–87. [CrossRef]

- Chang-Panesso M. Acute kidney injury and aging. Pediatric Nephrology 2021;36:2997–3006. [CrossRef]

- Huang W, Hickson LTJ, Eirin A, Kirkland JL, Lerman LO. Cellular senescence: the good, the bad and the unknown. Nat Rev Nephrol 2022;18:611–27. [CrossRef]

- Sturmlechner I, Durik M, Sieben CJ, Baker DJ, Van Deursen JM. Cellular senescence in renal ageing and disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2017;13:77–89. [CrossRef]

- López-Otín C, Blasco MA, Partridge L, Serrano M, Kroemer G. Hallmarks of aging: An expanding universe. Cell 2023;186:243–78. [CrossRef]

- O’Sullivan EA, Wallis R, Mossa F, Bishop CL. The paradox of senescent-marker positive cancer cells: challenges and opportunities. Npj Aging 2024;10:41. [CrossRef]

- Rayego-Mateos S, Marquez-Expósito L, Rodrigues-Diez R, Sanz AB, Guiteras R, Doladé N, Rubio-Soto I, Manonelles A, Codina S, Ortiz A, Cruzado JM, Ruiz-Ortega M, Sola A. Molecular Mechanisms of Kidney Injury and Repair. Int J Mol Sci 2022;23. [CrossRef]

- Li Y, Lerman LO. Cellular Senescence: A New Player in Kidney Injury. Hypertension 2020;76:1069–75. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Zhang H, Yi X, Dou Q, Yang X, He Y, Chen J, Chen K. Cellular senescence of renal tubular epithelial cells in acute kidney injury. Cell Death Discov 2024;10. [CrossRef]

- Sanz AB, Sanchez-Niño MD, Ramos AM, Ortiz A. Regulated cell death pathways in kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2023;19:281–99. [CrossRef]

- Ruiz-Ortega M, Rayego-Mateos S, Lamas S, Ortiz A, Rodrigues-Diez RR. Targeting the progression of chronic kidney disease. Nat Rev Nephrol 2020;16:269–88. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Livingston MJ, Ma Z, Hu X, Wen L, Ding HF, Zhou D, Dong Z. Tubular cell senescence promotes maladaptive kidney repair and chronic kidney disease after cisplatin nephrotoxicity. JCI Insight 2023;8. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Zhang H, Yi X, Dou Q, Yang X, He Y, Chen J, Chen K. Cellular senescence of renal tubular epithelial cells in acute kidney injury. Cell Death Discov 2024;10. [CrossRef]

- Kurella M, Chertow GM, Fried LF, Cummings SR, Harris T, Simonsick E, Satterfield S, Ayonayon H, Yaffe K. Chronic kidney disease and cognitive impairment in the elderly: The Health, Aging, and Body Composition study. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2005;16:2127–33. [CrossRef]

- Li C, Shen Y, Huang L, Liu C, Wang J. Senolytic therapy ameliorates renal fibrosis postacute kidney injury by alleviating renal senescence. FASEB Journal 2021;35. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Pitcher LE, Prahalad V, Niedernhofer LJ, Robbins PD. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: senolytics and senomorphics. FEBS Journal 2023;290:1362–83. [CrossRef]

- Robbins PD, Jurk D, Khosla S, Kirkland JL, Lebrasseur NK, Miller JD, Passos JF, Pignolo RJ, Tchkonia T, Niedernhofer LJ. Senolytic Drugs: Reducing Senescent Cell Viability to Extend Health Span n.d.

- Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, Gower AC, Ding H, Giorgadze N, Palmer AK, Ikeno Y, Hubbard GB, Lenburg M, O’hara SP, Larusso NF, Miller JD, Roos CM, Verzosa GC, Lebrasseur NK, Wren JD, Farr JN, Khosla S, Stout MB, McGowan SJ, Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H, Gurkar AU, Zhao J, Colangelo D, Dorronsoro A, Ling YY, Barghouthy AS, Navarro DC, Sano T, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ, Kirkland JL. The achilles’ heel of senescent cells: From transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015;14:644–58. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Pitcher LE, Prahalad V, Niedernhofer LJ, Robbins PD. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: senolytics and senomorphics. FEBS Journal 2023;290:1362–83. [CrossRef]

- Deepika, Maurya PK. Health Benefits of Quercetin in Age-Related Diseases. Molecules 2022;27. [CrossRef]

- Guo X, Wen S, Wang J, Zeng X, Yu H, Chen Y, Zhu X, Xu L. Senolytic combination of dasatinib and quercetin attenuates renal damage in diabetic kidney disease. Phytomedicine 2024;130. [CrossRef]

- Guerrero-Mauvecin J, Villar-Gómez N, Rayego-Mateos S, Ramos AM, Ruiz-Ortega M, Ortiz A, Sanz AB. Regulated necrosis role in inflammation and repair in acute kidney injury. Front Immunol 2023;14. [CrossRef]

- Lane BR. Molecular markers of kidney injury. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations 2013;31:682–5. [CrossRef]

- Ichimura T, Hung CC, Yang SA, Stevens JL, Bonventre J V. Kidney injury molecule-1: a tissue and urinary biomarker for nephrotoxicant-induced renal injury 2004.

- Marquez-Exposito L, Tejedor-Santamaria L, Santos-Sanchez L, Valentijn FA, Cantero-Navarro E, Rayego-Mateos S, Rodrigues-Diez RR, Tejera-Muñoz A, Marchant V, Sanz AB, Ortiz A, Goldschmeding R, Ruiz-Ortega M. Acute Kidney Injury is Aggravated in Aged Mice by the Exacerbation of Proinflammatory Processes. Front Pharmacol 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Di Micco R, Krizhanovsky V, Baker D, d’Adda di Fagagna F. Cellular senescence in ageing: from mechanisms to therapeutic opportunities. Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol 2021;22:75–95. [CrossRef]

- Martin-Sanchez D, Ruiz-Andres O, Poveda J, Carrasco S, Cannata-Ortiz P, Sanchez-Niño MD, Ruiz Ortega M, Egido J, Linkermann A, Ortiz A, Sanz AB. Ferroptosis, but not necroptosis, is important in nephrotoxic folic acid-induced AKI. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology 2017;28:218–29. [CrossRef]

- Robbins PD, Jurk D, Khosla S, Kirkland JL, Lebrasseur NK, Miller JD, Passos JF, Pignolo RJ, Tchkonia T, Niedernhofer LJ. Senolytic Drugs: Reducing Senescent Cell Viability to Extend Health Span n.d.

- Islam MT, Tuday E, Allen S, Kim J, Trott DW, Holland WL, Donato AJ, Lesniewski LA. Senolytic drugs, dasatinib and quercetin, attenuate adipose tissue inflammation, and ameliorate metabolic function in old age. Aging Cell 2023;22. [CrossRef]

- Saccon TD, Nagpal R, Yadav H, Cavalcante MB, Nunes ADDC, Schneider A, Gesing A, Hughes B, Yousefzadeh M, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL, Niedernhofer LJ, Robbins PD, Masternak MM. Senolytic Combination of Dasatinib and Quercetin Alleviates Intestinal Senescence and Inflammation and Modulates the Gut Microbiome in Aged Mice. Journals of Gerontology - Series A Biological Sciences and Medical Sciences 2021;76:1895–905. [CrossRef]

- Xu M, Pirtskhalava T, Farr JN, Weigand BM, Palmer AK, Weivoda MM, Inman CL, Ogrodnik MB, Hachfeld CM, Fraser DG, Onken JL, Johnson KO, Verzosa GC, Langhi LGP, Weigl M, Giorgadze N, LeBrasseur NK, Miller JD, Jurk D, Singh RJ, Allison DB, Ejima K, Hubbard GB, Ikeno Y, Cubro H, Garovic VD, Hou X, Weroha SJ, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ, Khosla S, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat Med 2018;24:1246–56. [CrossRef]

- Xu M, Pirtskhalava T, Farr JN, Weigand BM, Palmer AK, Weivoda MM, Inman CL, Ogrodnik MB, Hachfeld CM, Fraser DG, Onken JL, Johnson KO, Verzosa GC, Langhi LGP, Weigl M, Giorgadze N, LeBrasseur NK, Miller JD, Jurk D, Singh RJ, Allison DB, Ejima K, Hubbard GB, Ikeno Y, Cubro H, Garovic VD, Hou X, Weroha SJ, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ, Khosla S, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL. Senolytics improve physical function and increase lifespan in old age. Nat Med 2018;24:1246–56. [CrossRef]

- Hickson LTJ, Langhi Prata LGP, Bobart SA, Evans TK, Giorgadze N, Hashmi SK, Herrmann SM, Jensen MD, Jia Q, Jordan KL, Kellogg TA, Khosla S, Koerber DM, Lagnado AB, Lawson DK, LeBrasseur NK, Lerman LO, McDonald KM, McKenzie TJ, Passos JF, Pignolo RJ, Pirtskhalava T, Saadiq IM, Schaefer KK, Textor SC, Victorelli SG, Volkman TL, Xue A, Wentworth MA, Wissler Gerdes EO, Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL. Senolytics decrease senescent cells in humans: Preliminary report from a clinical trial of Dasatinib plus Quercetin in individuals with diabetic kidney disease. EBioMedicine 2019;47:446–56. [CrossRef]

- Zhu X, Zhang C, Liu L, Xu L, Yao L. Senolytic combination of dasatinib and quercetin protects against diabetic kidney disease by activating autophagy to alleviate podocyte dedifferentiation via the Notch pathway. Int J Mol Med 2024;53. [CrossRef]

- Huang Y, Wang B, Hassounah F, Price SR, Klein J, Mohamed TMA, Wang Y, Park J, Cai H, Zhang X, Wang XH. The impact of senescence on muscle wasting in chronic kidney disease. J Cachexia Sarcopenia Muscle 2023;14:126–41. [CrossRef]

- Schafer MJ, White TA, Iijima K, Haak AJ, Ligresti G, Atkinson EJ, Oberg AL, Birch J, Salmonowicz H, Zhu Y, Mazula DL, Brooks RW, Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H, Pirtskhalava T, Prakash YS, Tchkonia T, Robbins PD, Aubry MC, Passos JF, Kirkland JL, Tschumperlin DJ, Kita H, LeBrasseur NK. Cellular senescence mediates fibrotic pulmonary disease. Nat Commun 2017;8. [CrossRef]

- Manavi Z, Melchor GS, Bullard MR, Gross PS, Ray S, Gaur P, Baydyuk M, Huang JK. Senescent cell reduction does not improve recovery in mice under experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) induced demyelination. J Neuroinflammation 2025;22:101. [CrossRef]

- Nieto M, Könisgberg M, Silva-Palacios A. Quercetin and dasatinib, two powerful senolytics in age-related cardiovascular disease. Biogerontology 2024;25:71–82. [CrossRef]

- Molitoris BA. Therapeutic translation in acute kidney injury: The epithelial/endothelial axis. Journal of Clinical Investigation 2014;124:2355–63. [CrossRef]

- Ferenbach DA, Bonventre JV. Mechanisms of maladaptive repair after AKI leading to accelerated kidney ageing and CKD. Nat Rev Nephrol. 2015;11(5):264-76. [CrossRef]

- Andrade L, Rodrigues CE, Gomes SA, Noronha IL. Acute Kidney Injury as a Condition of Renal Senescence. Cell Transplant 2018;27:739–53. [CrossRef]

- Megyesi J, Udvarhelyi N, Safirstein RL, Price PM. The p534ndependent activation of transcription of p21WAF1/C1P1/SD*1 after acute renal failure. 1996.

- Megyesi J, Safirstein RL, Price PM. p21 Affects Cisplatin Renal Failure Induction of p21 WAF1/CIP1/SDI1 in Kidney Tubule Cells Affects the Course of Cisplatin-induced Acute Renal Failure. vol. 101. 1998.

- Nishioka S, Nakano D, Kitada K, Sofue T, Ohsaki H, Moriwaki K, Hara T, Ohmori K, Kohno M, Nishiyama A. The cyclin-dependent kinase inhibitor p21 is essential for the beneficial effects of renal ischemic preconditioning on renal ischemia/reperfusion injury in mice. Kidney Int 2014;85:871–9. [CrossRef]

- Megyesi J, Andrade L, Vieira JM, Safirstein RL, Price PM. Coordination of the cell cycle is an important determinant of the syndrome of acute renal failure n.d.

- Hochegger K, Koppelstaetter C, Tagwerker A, Huber JM, Heininger D, Mayer G, Rosenkranz AR. p21 and mTERT are novel markers for determining different ischemic time periods in renal ischemia-reperfusion injury. Am J Physiol Renal Physiol 2007;292:762–8.

- Price PM, Safirstein RL, Megyesi J. The cell cycle and acute kidney injury. Kidney Int 2009;76:604–13. [CrossRef]

- Chen J, Zhang H, Yi X, Dou Q, Yang X, He Y, Chen J, Chen K. Cellular senescence of renal tubular epithelial cells in acute kidney injury. Cell Death Discovery 2024 10:1 2024;10:1–13. [CrossRef]

- Della Vedova L, Baron G, Morazzoni P, Aldini G, Gado F. The Potential of Polyphenols in Modulating the Cellular Senescence Process: Implications and Mechanism of Action. Pharmaceuticals 2025;18. [CrossRef]

- Ren Q, Guo F, Tao S, Huang R, Ma L, Fu P. Flavonoid fisetin alleviates kidney inflammation and apoptosis via inhibiting Src-mediated NF-κB p65 and MAPK signaling pathways in septic AKI mice. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2020;122. [CrossRef]

- Ge C, Xu M, Qin Y, Gu T, Lou D, Li Q, Hu L, Nie X, Wang M, Tan J. Fisetin supplementation prevents high fat diet-induced diabetic nephropathy by repressing insulin resistance and RIP3-regulated inflammation. Food Funct 2019;10:2970–85. [CrossRef]

- Chenxu G, Xianling D, Qin K, Linfeng H, Yan S, Mingxin X, Jun T, Minxuan X. Fisetin protects against high fat diet-induced nephropathy by inhibiting inflammation and oxidative stress via the blockage of iRhom2/NF-κB signaling. Int Immunopharmacol 2021;92. [CrossRef]

- Ren Q, Tao S, Guo F, Wang B, Yang L, Ma L, Fu P. Natural flavonol fisetin attenuated hyperuricemic nephropathy via inhibiting IL-6/JAK2/STAT3 and TGF-β/SMAD3 signaling. Phytomedicine 2021;87. [CrossRef]

- Ju HY, Kim J, Han SJ. The flavonoid fisetin ameliorates renal fibrosis by inhibiting SMAD3 phosphorylation, oxidative damage, and inflammation in ureteral obstructed kidney in mice. Kidney Res Clin Pract 2023;42:325–39. [CrossRef]

- Prasath GS, Subramanian SP. Modulatory effects of fisetin, a bioflavonoid, on hyperglycemia by attenuating the key enzymes of carbohydrate metabolism in hepatic and renal tissues in streptozotocin-induced diabetic rats. Eur J Pharmacol 2011;668:492–6. [CrossRef]

- Liu AB, Tan B, Yang P, Tian N, Li JK, Wang SC, Yang LS, Ma L, Zhang JF. The role of inflammatory response and metabolic reprogramming in sepsis-associated acute kidney injury: mechanistic insights and therapeutic potential. Front Immunol 2024;15. [CrossRef]

- Ren Q, Guo F, Tao S, Huang R, Ma L, Fu P. Flavonoid fisetin alleviates kidney inflammation and apoptosis via inhibiting Src-mediated NF-κB p65 and MAPK signaling pathways in septic AKI mice. Biomedicine and Pharmacotherapy 2020;122. [CrossRef]

- Valentijn FA, Knoppert SN, Pissas G, Rodrigues-Diez RR, Marquez-Exposito L, Broekhuizen R, Mokry M, Kester LA, Falke LL, Goldschmeding R, Ruiz-Ortega M, Eleftheriadis T, Nguyen TQ. Ccn2 aggravates the immediate oxidative stress–dna damage response following renal ischemia–reperfusion injury. Antioxidants 2021;10. [CrossRef]

- Rayego-Mateos S, Marquez-Exposito L, Basantes P, Tejedor-Santamaria L, Sanz AB, Nguyen TQ, Goldschmeding R, Ortiz A, Ruiz-Ortega M. CCN2 Activates RIPK3, NLRP3 Inflammasome, and NRF2/Oxidative Pathways Linked to Kidney Inflammation. Antioxidants 2023;12. [CrossRef]

- Xu M, Tchkonia T, Ding H, Ogrodnik M, Lubbers ER, Pirtskhalava T, White TA, Johnson KO, Stout MB, Mezera V, Giorgadze N, Jensen MD, LeBrasseur NK, Kirkland JL. JAK inhibition alleviates the cellular senescence-associated secretory phenotype and frailty in old age. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015;112:E6301–10. [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Silva D, López-Abellán MD, Martínez-Navarro FJ, García-Castillo J, Cayuela ML, Alcaraz-Pérez F. Development of a Short Telomere Zebrafish Model for Accelerated Aging Research and Antiaging Drug Screening. Aging Cell 2025. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Pitcher LE, Prahalad V, Niedernhofer LJ, Robbins PD. Targeting cellular senescence with senotherapeutics: senolytics and senomorphics. FEBS Journal 2023;290:1362–83. [CrossRef]

- Kuro-O* M, Matsumura Y, Aizawa H, Kawaguchi H, Suga T, Utsugi T, Ohyama Y, Kurabayashi M, Kaname T, Kumek E, Iwasakik H, Iida A, Shiraki-Iida T, Nishikawa# S, Nagai R, Yo-Ichi Nabeshima &. Mutation of the mouse klotho gene leads to a syndrome resembling ageing. vol. 390. 1997.

- Izquierdo MC, Perez-Gomez M V., Sanchez-Niño MD, Sanz AB, Ruiz-Andres O, Poveda J, Moreno JA, Egido J, Ortiz A. Klotho, phosphate and inflammation/ageing in chronic kidney disease. Nephrology Dialysis Transplantation 2012;27. [CrossRef]

- Li S, Yu L, He A, Liu Q. Klotho inhibits unilateral ureteral obstruction-induced endothelial-to-mesenchymal transition via TGF-β1/Smad2/Snail1 signaling in mice. Front Pharmacol 2019;10. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Langhi Prata LGP, Wissler Gerdes EO, Machado J, Netto E, Pirtskhalava T, Giorgadze N, Tripathi U, Inman CL, Johnson KO, Xue A, Palmer AK, Chen T, Schaefer K, Justice JN, Nambiar AM, Musi N, Kritchevsky SB, Chen J, Khosla S, Jurk D, Schafer MJ, Tchkonia T, Kirkland JL. Orally-active, clinically-translatable senolytics restore a-Klotho in mice and humans 2022.

- Castillo RF. Pathophysiologic Implications and Therapeutic Approach of Klotho in Chronic Kidney Disease: A Systematic Review. Laboratory Investigation 2023;103. [CrossRef]

- Wang C, Jurk D, Maddick M, Nelson G, Martin-ruiz C, Von Zglinicki T. DNA damage response and cellular senescence in tissues of aging mice. Aging Cell 2009;8:311–23. [CrossRef]

- Zhu Y, Tchkonia T, Pirtskhalava T, Gower AC, Ding H, Giorgadze N, Palmer AK, Ikeno Y, Hubbard GB, Lenburg M, O’hara SP, Larusso NF, Miller JD, Roos CM, Verzosa GC, Lebrasseur NK, Wren JD, Farr JN, Khosla S, Stout MB, McGowan SJ, Fuhrmann-Stroissnigg H, Gurkar AU, Zhao J, Colangelo D, Dorronsoro A, Ling YY, Barghouthy AS, Navarro DC, Sano T, Robbins PD, Niedernhofer LJ, Kirkland JL. The achilles’ heel of senescent cells: From transcriptome to senolytic drugs. Aging Cell 2015;14:644–58. [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Exposito L, Tejedor-Santamaria L, Santos-Sanchez L, Valentijn FA, Cantero-Navarro E, Rayego-Mateos S, Rodrigues-Diez RR, Tejera-Muñoz A, Marchant V, Sanz AB, Ortiz A, Goldschmeding R, Ruiz-Ortega M. Acute Kidney Injury is Aggravated in Aged Mice by the Exacerbation of Proinflammatory Processes. Front Pharmacol 2021;12. [CrossRef]

- Baar MP, Brandt RMC, Putavet DA, Klein JDD, Derks KWJ, Bourgeois BRM, Stryeck S, Rijksen Y, van Willigenburg H, Feijtel DA, van der Pluijm I, Essers J, van Cappellen WA, van IJcken WF, Houtsmuller AB, Pothof J, de Bruin RWF, Madl T, Hoeijmakers JHJ, Campisi J, de Keizer PLJ. Targeted Apoptosis of Senescent Cells Restores Tissue Homeostasis in Response to Chemotoxicity and Aging. Cell 2017;169:132-147.e16. [CrossRef]

- Marquez-Exposito L, Tejedor-Santamaria L, Valentijn FA, Tejera-Muñoz A, Rayego-Mateos S, Marchant V, Rodrigues-Diez RR, Rubio-Soto I, Knoppert SN, Ortiz A, Ramos AM, Goldschmeding R, Ruiz-Ortega M. Oxidative Stress and Cellular Senescence Are Involved in the Aging Kidney. Antioxidants 2022;11. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).