Submitted:

25 April 2025

Posted:

26 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Taxon Sampling and Sequencing

2.2. Genome Composition and Codon Usage

2.3. Substitution Rate and Phylogenetic Analyses

3. Results

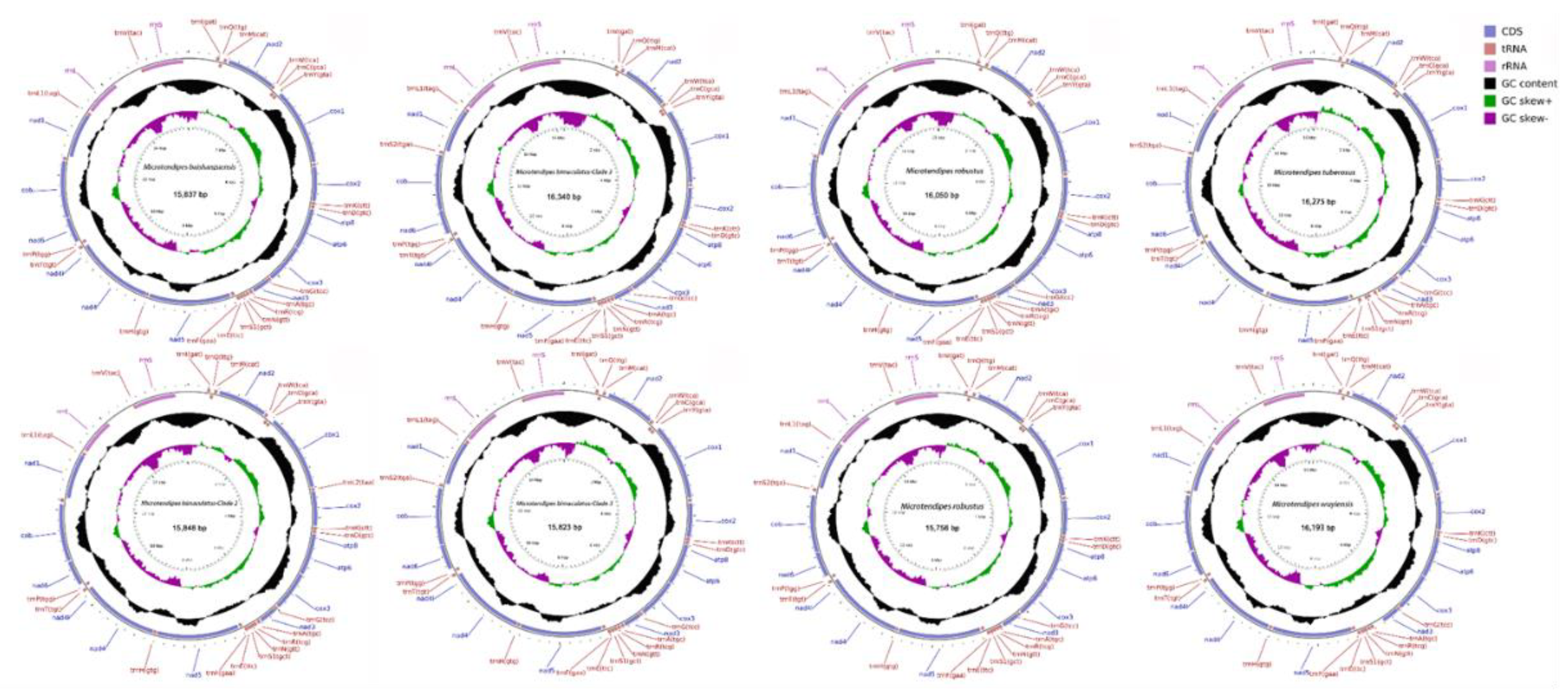

3.1. Genome Organization

3.2. Nucleotide Composition

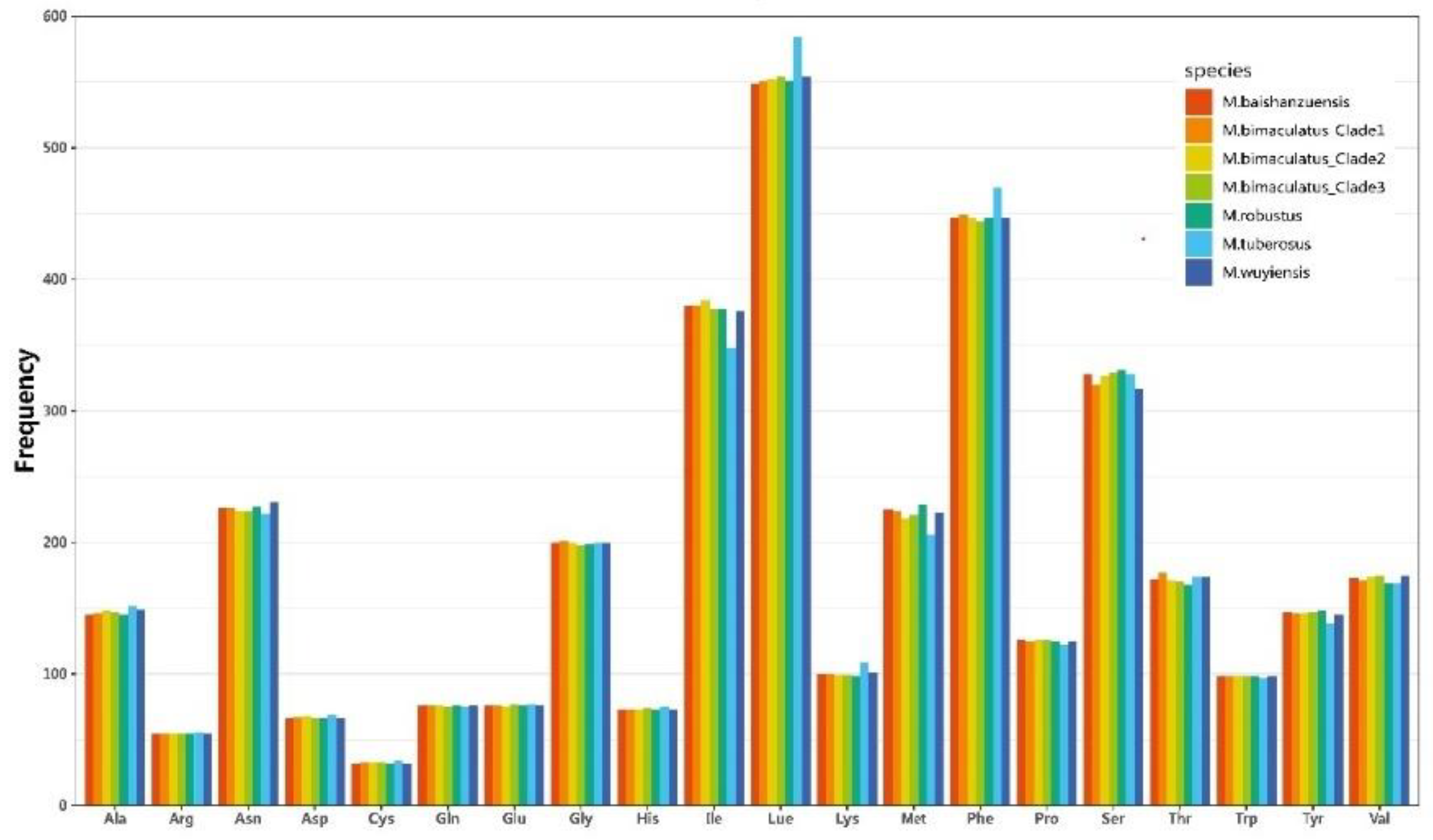

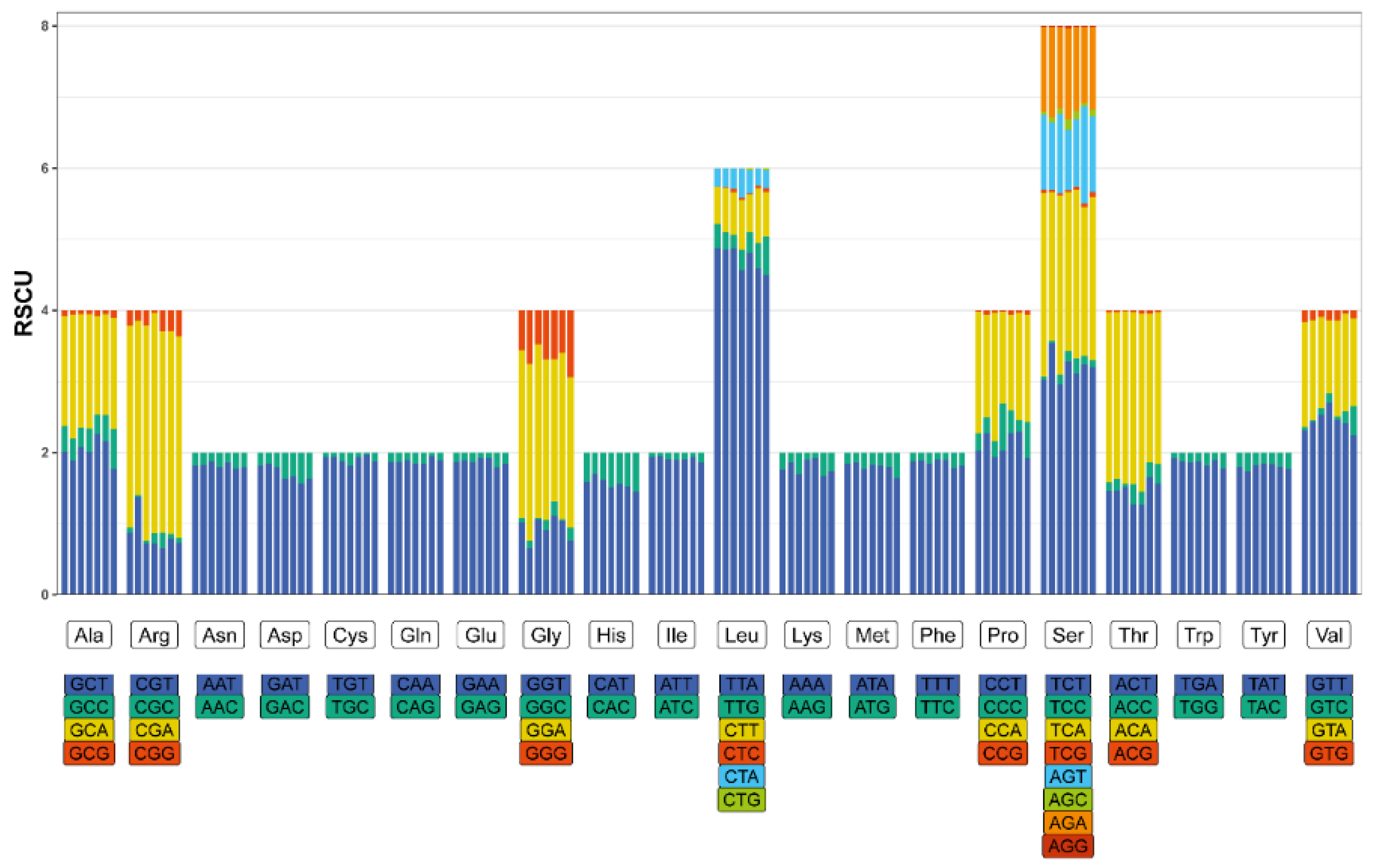

3.3. Protein-Coding Genes and Codon Usage

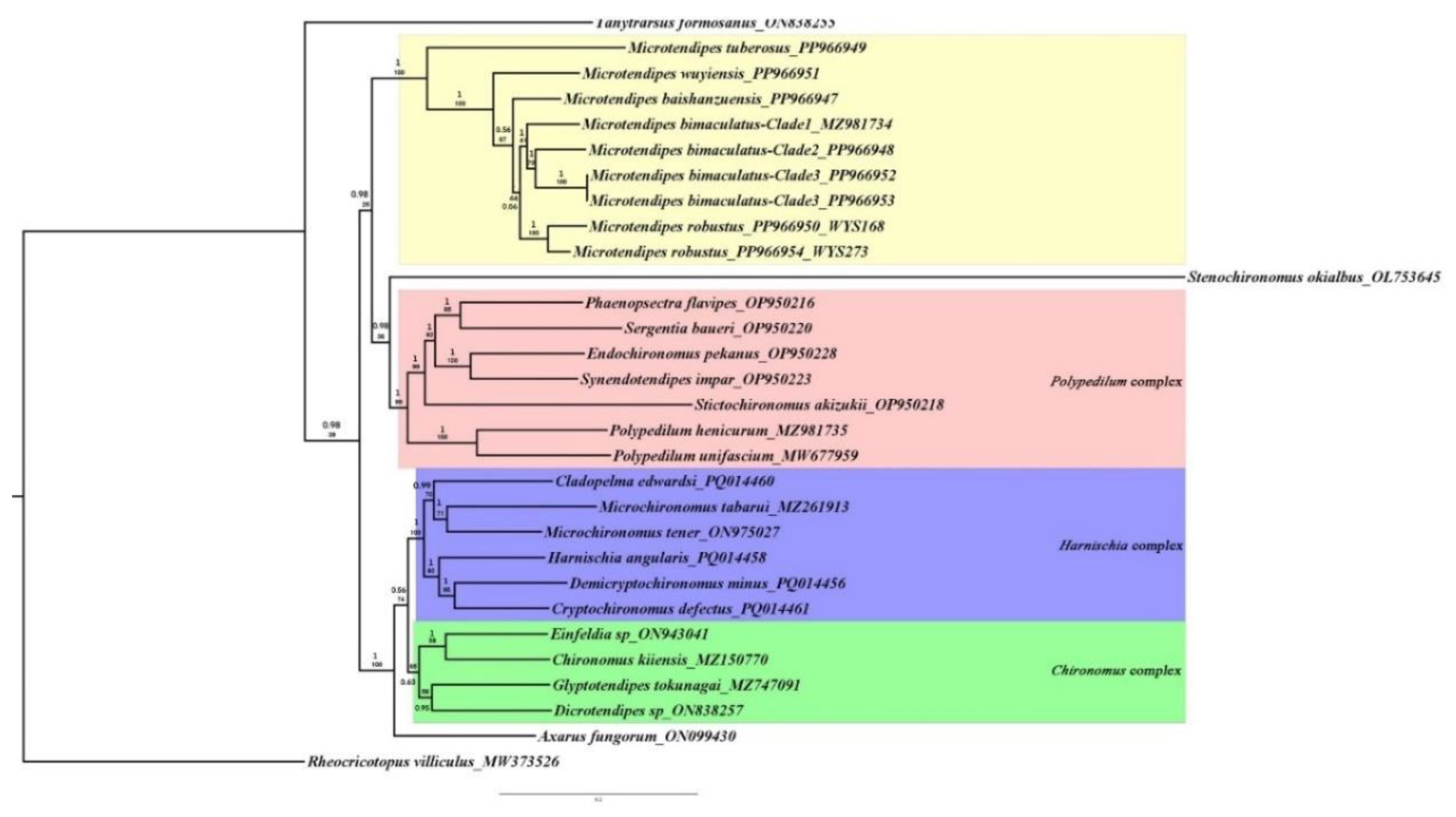

3.4. Phylogeny of Chironominae

4. Discussion

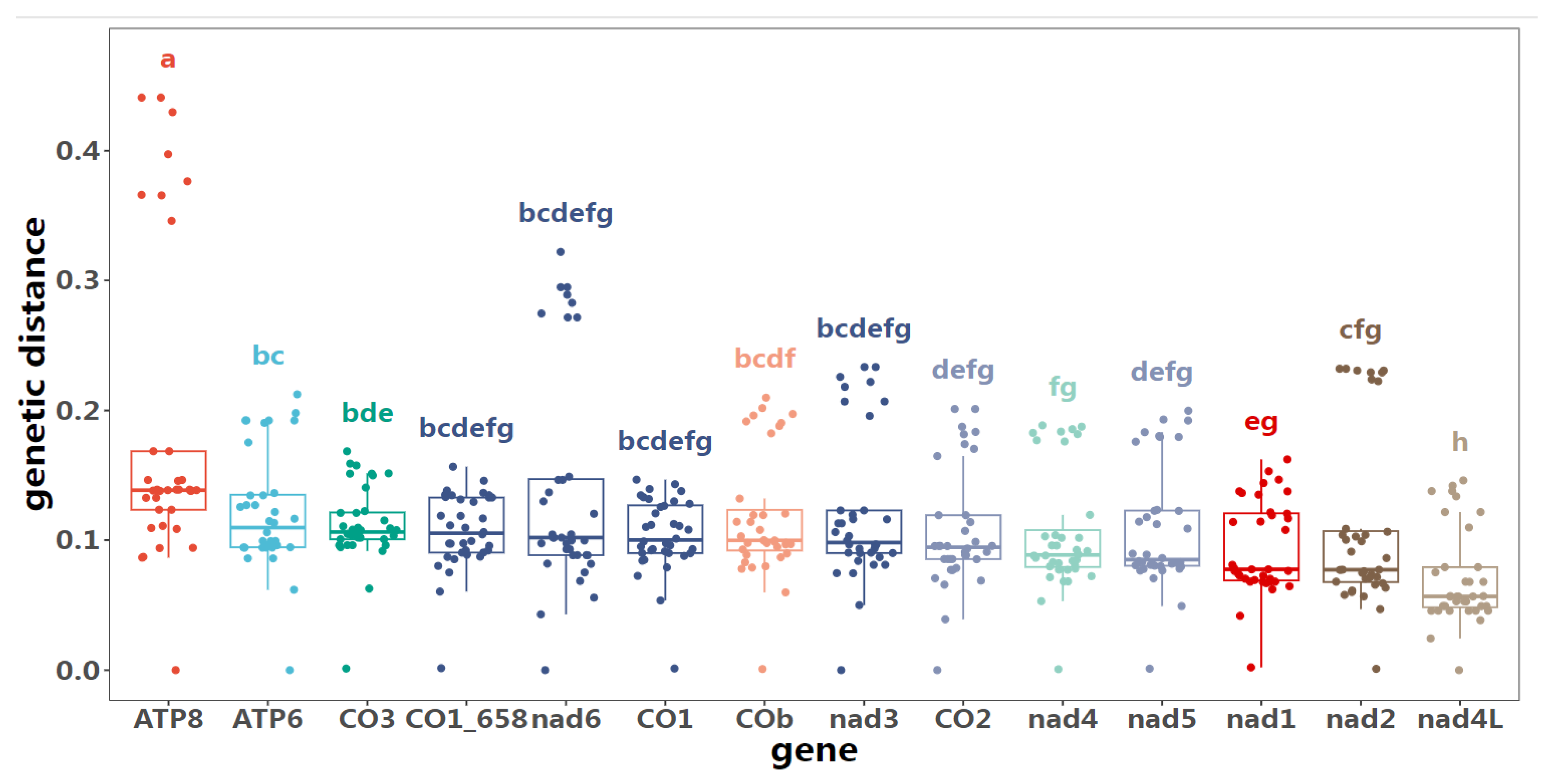

4.1. 658 bp COI Based Barcode vs Mitogenome-Based Barcode

4.2. Phylogenetic Position of Microtendipes

4.3. Phylogeny Within Microtendipes

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Cameron, S.L. Insect Mitochondrial Genomics: Implications for Evolution and Phylogeny. Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2014, 59, 95–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, L.P.; Zheng, F.Y.; Bai, J.; Wang, J.M.; Li, X.J. Comparative analysis of mitogenomes among six species of grasshoppers (Orthoptera: Acridoidea: Catantopidae) and their phylogenetic implications in wing-type evolution. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2020, 159, 1062–1072. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, J.; Chen, X.; Li, C.; Song, Y.H. Mitogenome and phylogenetic analysis of typhlocybine leafhoppers (Hemiptera: Cicadellidae). Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 10053. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, C.; Zhu, X.; Wang, Y.; Dong, X.; Yang, R.; Tang, Z.; Bu, W. Mitogenomes Provide Insights into the Species Boundaries and Phylogenetic Relationships among Three Dolycoris Sloe Bugs (Hemiptera: Pentatomidae) from China. Insects. 2024, 15, 134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, W.M.A.; Moustafa, M.A.M.; Thu, M.J.; et al. Comparative mitogenomics elucidates the population genetic structure of Amblyomma testudinarium in Japan and a closely related Amblyomma species in Myanmar. Evol. appl. 2022, 15, 1062–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamoto, K.; Sakaue, S.; Matsuda, K.; et al. Genetic and phenotypic landscape of the mitochondrial genome in the Japanese population. Commun. Biol. 2020, 3, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boore, J.L. Animal mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic. Acids. Res. 1999, 27, 1767–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Finstermeier, K.; Zinner, D.; Brameier, M.; et al. A mitogenomic phylogeny of living primates. PloS. one. 2013, 8, e69504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, Q.; Li, F.; Zheng, J.; Liu, C.; Wang, A.; Yang, Y.; Gu, Z. Mitogenomic phylogeny of Cypraeidae (Gastropoda: Mesogastropoda). Front Ecol Evol. 2023, 11, 1138297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irwin, A.R.; Strong, E.E.; Kano, Y.; Harper, E.M.; Williams, S.T. Eight new mitogenomes clarify the phylogenetic relationships of Stromboidea within the caenogastropod phylogenetic framework. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 158, 107081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, M.J.; Zakaria, S.S. Enhancing mitogenomic phylogeny and resolving the relationships of extinct megafaunal placental mammals. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2021, 158, 107082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poliseno, A.; Feregrino, C.; Sartoretto, S.; Aurelle, D.; Wörheide, G.; McFadden, CS.; Vargas, S. Comparative mitogenomics, phylogeny and evolutionary history of Leptogorgia (Gorgoniidae). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2017, 115, 181–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Timmermans, M.J.T.N.; Lees, D.C.; Simonsen, T.J. Towards a mitogenomic phylogeny of Lepidoptera. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2014, 79, 169–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fang, X.; Wang, X.; Mao, B.; et al. Comparative mitogenome analyses of twelve non-biting flies and provide insights into the phylogeny of Chironomidae (Diptera: Culicomorpha). Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 9200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.Y.; Chen, M.H.; Sun, L.; Wang, R.H.; Li, C.H.; Gresens, S.; Li, Z.; Lin, X.L. New mitogenomes from the genus Cricotopus (Diptera: Chironomidae, Orthocladiinae): Characterization and phylogenetic implications. Arch Insect Biochem Physiol. 2024, 115, e22067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.L.; Liu, Z.; Yan, L.P.; Duan, X.; Bu, W.J.; Wang, X.H.; Zheng, C.G. Mitogenomes provide new insights of evolutionary history of Boreheptagyiini and Diamesini (Diptera: Chironomidae: Diamesinae). Ecol Evol. 2022, 12, e8957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; He, F.X.; Li, X.B.; Aishan, Z.; Lin, X.L. New mitogenomes of the Polypedilum generic complex (Diptera: Chironomidae): characterization and phylogenetic implications. Insects. 2023, 14, 238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawai, K.; Kawaguchi, K.; Kodama, A.; Saito, H. Fundamental studies on acid-tolerant chironomids in Japan. Limnology. 2019, 20, 101–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinder, L.C.V. Biology of freshwater Chironomidae. Annu Rev Entomol. 1986, 31, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martel-Cea, A.; Astorga, G.A.; Hernández, M.; Caputo, L.; Abarzúa, A.M. Modern chironomids (Diptera: Chironomidae) and the environmental variables that influence their distribution in the Araucanian lakes, south-central Chile. Hydrobiologia. 2021, 848, 2551–2568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozeretska, I.; Serga, S.; Kovalenko, P.; Gorobchyshyn, V.; Convey, P. Belgica antarctica (Diptera: Chironomidae): A natural model organism for extreme environments. Insect Science. 2022, 29, 2–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qi, X.; Wang, X.H. A review of Microtendipes Kieffer from China (Diptera: Chironomidae). Zootaxa. 2006, 1108, 37–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, H.; Niitsuma, H. Review of the Japanese Microtendipes (Diptera: Chironomidae: Chironominae), with description of a new species. Zootaxa. 2017, 4320, 535–553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, C.; Wang, L.; Lei, T.; Qi, X. New color-patterned species of Microtendipes Kieffer, 1913 (Diptera: Chironomidae) and a deep intraspecific divergence of species by DNA barcodes. Insects 2023, 14, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, J.K.; Lei, T.; Gu, J.J.; Song, C.; Qi, X. Codon bias analysis of the mitochondrial genome reveals natural selection in the nonbiting midge Microtendipes umbrosus Freeman, 1955 (Diptera: Chironomidae). The Pan-Pacific Entomologist 2023, 99, 217–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sæther, O.A. Female genitalia in Chironomidae and other Nematocera: morphology, phylogenies, keys. Bull Fish Res Board Can. 1977, 197, 1–209. [Google Scholar]

- Sasa, M. Chironomidae of Japan: Checklist of species recorded, key to males and taxonomic notes. NIES Res Rep. 1989, 125, 1–177. [Google Scholar]

- Cranston, P.S.; Hardy, N.B.; Morse, G.E. A dated molecular phylogeny for the Chironomidae (Diptera). Syst Entomol. 2012, 37, 172–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Folmer, O.; Black, M.; Hoeh, W.; Lutz, R.; Vrijenhoek, R. DNA primers for amplification of mitochondrial oxidase subunit I from diverse metazoan invertebrates. Mol Mar Biol Biotechnol. 1994, 3, 294–299. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Lin, X.L.; Wang, Q.; Wang, XH. DNA barcodes successfully delimit morphospecies in a superdiverse insect genus. Zool Scr. 2018, 47, 311–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, G.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, S. MitoZ: a toolkit for animal mitochondrial genome assembly, annotation and visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dierckxsens, N.; Mardulyn, P.; Smits, G. NOVOPlasty: De novo assembly of organelle genomes from whole genome data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, e18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Prjibelski, A.; Antipov, D.; Meleshko, D.; Lapidus, A.; Korobeynikov, A. Using SPAdes de novo assembler. Current Protocols in Bioinformatics. 2020, 70, e102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stothard, P.; Wishart, D.S. Circular genome visualization and exploration using CGView. Bioinformatics. 2005, 21, 537–539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, A.; Jühling, F.; Al-Arab, M.; Bernhart, S.H.; Reinhardt, F.; Stadler, P.F.; Middendorf, M.; Bernt, M. Improved annotation of protein-coding genes boundaries in metazoan mitochondrial genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, 10543–10552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, W.; Sipos, B.; Zhao, L. SeqKit2: A Swiss army knife for sequence and alignment processing. iMeta. 2024, 5, e191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rice, P.; Longden, I.; Bleasby, A. EMBOSS: the European molecular biology open software suite. Trends in genetics. 2000, 16, 276–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wickham, H.; Chang, W.; Wickham, M.H. Package ‘ggplot2’. Create elegant data visualisations using the grammar of graphics. Version. 2016, 2, 1–189. [Google Scholar]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: improvements in performance and usability. Molecular biology and evolution. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Kumar, S. MEGA11: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 11. Mol Biol Evol. 2021, 38, 3022–3027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stamatakis, A. RAxML version 8: a tool for phylogenetic analysis and post-analysis of large phylogenies. Bioinformatics. 2014, 30, 1312–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ronquist, F.; Teslenko, M.; Van der Mark, P.; Ayres, D.L.; Darling, A.; Höhna, S.; Larget, B.; Liu, L.; Suchard, M.A.; Huelsenbeck, J.P. MRBAYES 3.2: Efficient Bayesian phylogenetic inference and model selection across a large model space. Syst. Biol. 2012, 61, 539–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanfear, R.; Frandsen, P.B.; Wright, A.M.; Senfeld, T.; Calcott, B. PartitionFinder 2: new methods for selecting partitioned models of evolution for molecular and morphological phylogenetic analyses. Mol Biol Evol. 2017, 34, 772–773. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Letunic, I.; Bork, P. Interactive Tree of Life (iTOL) v5: an online tool for phylogenetic tree display and annotation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2021, 49, W293–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.L.; Stur, E.; Ekrem, T. Exploring genetic divergence in a species-rich insect genus using 2790 DNA barcodes. PLoS. One. 2015, 10, e0138993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meier, R.; Shiyang, K.; Vaidya, G.; Ng, P.K.L. DNA barcoding and taxonomy in diptera: A tale of high intraspecific variability and low identification success. Syst Biol. 2006, 55, 715–728. [Google Scholar]

- Yeo, D.; Puniamoorthy, J.; Ngiam, R.W.; Meier, R. Towards holomorphology in entomology: rapid and cost-effective adult–larva matching using NGS barcodes. Syst. entomol. 2018, 43, 678–691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Epler, J.H.; Ekrem, T.; Cranston, P.S. 10. The larvae of Holarctic Chironominae (Diptera: Chironomidae)–Keys and diagnoses. Chironomidae of the Holarctic Region. Keys and diagnoses. Part 1 2013, 387–556. [Google Scholar]

| Species | Accession No. | Species | Accession No. |

|---|---|---|---|

| Axarus fungorum | ON099430 | Demicryptochironomus minus | PQ014456 |

| Chironomus kiiensis | MZ150770 | Cryptochironomus defectus | PQ014461 |

| Microchironomus tabarui | MZ261913 | Cladopelma edwardsi | PQ014460 |

| Microtendipes bimaculatus-Clade1 | MZ981734 | Dicrotendipes sp. | ON838257 |

| Microtendipes bimaculatus-Clade2 | PP966948* | Einfeldia sp. | ON943041 |

| Microtendipes bimaculatus-Clade3 | PP966952* | Endochironomus pekanus | OP950228 |

| Microtendipes bimaculatus-Clade3 | PP966953* | Glyptotendipes tokunagai | MZ747091 |

| Microtendipes baishanzuensis | PP966947* | Microchironomus tener | ON975027 |

| Microtendipes tuberosus | PP966949* | Phaenopsectra flavipes | OP950216 |

| Microtendipes wuyiensis | PP966951* | Sergentia baueri | OP950220 |

| Microtendipes robustus | PP966950* | Stictochironomus akizukii | OP950218 |

| Microtendipes robustus | PP966954* | Synendotendipes impar | OP950223 |

| Polypedilum henicurum | MZ981735 | Synendotendipes sp.1 | OP950221 |

| Species | Whole Genome | PCG | tRNA | |||||||||||||

| Length (bp) |

AT% | AT -Skew% |

GC% | GC- Skew% |

Length (bp) |

AT% | AT- Skew% |

GC% | GC- Skew% |

Length (bp) |

AT% | AT- Skew% |

GC% | GC- Skew% |

||

| M. bimaculatus | 15827 | 80.41 | 1.08 | 19.59 | -18.13 | 11121 | 77.84 | -17.69 | 22.16 | 1.62 | 1578 | 82.76 | -3.67 | 17.24 | 29.41 | |

| M. bimaculatus | 15848 | 80.1 | 1.88 | 19.9 | -18.87 | 11121 | 77.63 | -17.66 | 22.37 | 0.88 | 1583 | 82.56 | -3.76 | 17.44 | 28.99 | |

| M. bimaculatus | 16340 | 80.28 | 2.62 | 19.72 | -20.73 | 11106 | 77.06 | -17.91 | 22.94 | -1.65 | 1575 | 82.67 | -3.69 | 17.33 | 29.67 | |

| M. bimaculatus | 15823 | 79.76 | 2.66 | 20.24 | -20.3 | 11106 | 77.02 | -17.94 | 22.98 | -1.57 | 1583 | 82.82 | -3.43 | 17.18 | 30.15 | |

| M. baishanzuensis | 15837 | 80.35 | 2.08 | 19.65 | -19.54 | 11121 | 77.8 | -17.32 | 22.2 | 1.90 | 1577 | 82.18 | -3.70 | 17.82 | 31.67 | |

| M. tuberosus | 16257 | 79.97 | 2.61 | 20.03 | -19.74 | 11154 | 76.94 | -19.16 | 23.06 | 0.16 | 1595 | 82.88 | -2.43 | 17.12 | 27.47 | |

| M. robustus | 15756 | 80.12 | 2.10 | 19.88 | -18.97 | 11109 | 77.5 | -18.04 | 22.5 | 0.56 | 1593 | 82.93 | -2.95 | 17.07 | 29.41 | |

| M. robustus | 16050 | 80.77 | 1.67 | 19.23 | -18.04 | 11109 | 78.09 | -17.92 | 21.91 | 2.38 | 1582 | 82.62 | -3.29 | 17.38 | 31.64 | |

| M. wuyiensis | 16193 | 79.19 | 2.34 | 20.81 | -22.26 | 11118 | 76.07 | -18.13 | 23.93 | 0.56 | 1587 | 82.61 | -3.16 | 17.39 | 28.99 | |

| Species | rRNA | CR | ||||||||||||||

| Length (bp) |

AT% | AT -Skew% |

GC% | GC- Skew% |

Length (bp) |

AT% | AT- Skew% |

GC% | GC- Skew% |

|||||||

| M. bimaculatus | 1492 | 82.44 | 5.05 | 17.56 | 12.98 | 726 | 94.9 | -8.27 | 5.1 | -56.76 | ||||||

| M. bimaculatus | 1494 | 82.26 | 4.48 | 17.74 | 16.23 | 408 | 94.36 | -2.33 | 5.64 | -47.83 | ||||||

| M. bimaculatus | 1496 | 82.29 | 4.79 | 17.71 | 13.96 | 1266 | 94.55 | 0.58 | 5.45 | -62.32 | ||||||

| M. bimaculatus | 1498 | 82.31 | 4.94 | 17.69 | 13.96 | 922 | 94.14 | 0 | 5.86 | -55.56 | ||||||

| M. baishanzuensis | 1492 | 82.51 | 4.30 | 17.49 | 13.41 | 798 | 94.74 | -9.52 | 5.26 | -57.14 | ||||||

| M. tuberosus | 1508 | 81.43 | 3.92 | 18.57 | 14.29 | 664 | 94.58 | 5.41 | 5.42 | -72.22 | ||||||

| M. robusts | 1488 | 82.39 | 4.73 | 17.61 | 15.27 | 727 | 96.42 | 0.72 | 3.58 | -53.85 | ||||||

| M. robusts | 1490 | 82.42 | 5.05 | 17.58 | 13.74 | 615 | 95.45 | -0.85 | 4.55 | -35.71 | ||||||

| M. wuyiensis | 1501 | 81.48 | 5.65 | 18.52 | 12.23 | 338 | 95.56 | -3.41 | 4.44 | -46.67 | ||||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).