Submitted:

03 October 2024

Posted:

04 October 2024

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Data Collection

2.2. Assembly and Annotation of Mitogenome Sequences

2.3. Phylogenetic Analysis

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Bibliographic Survey of Species

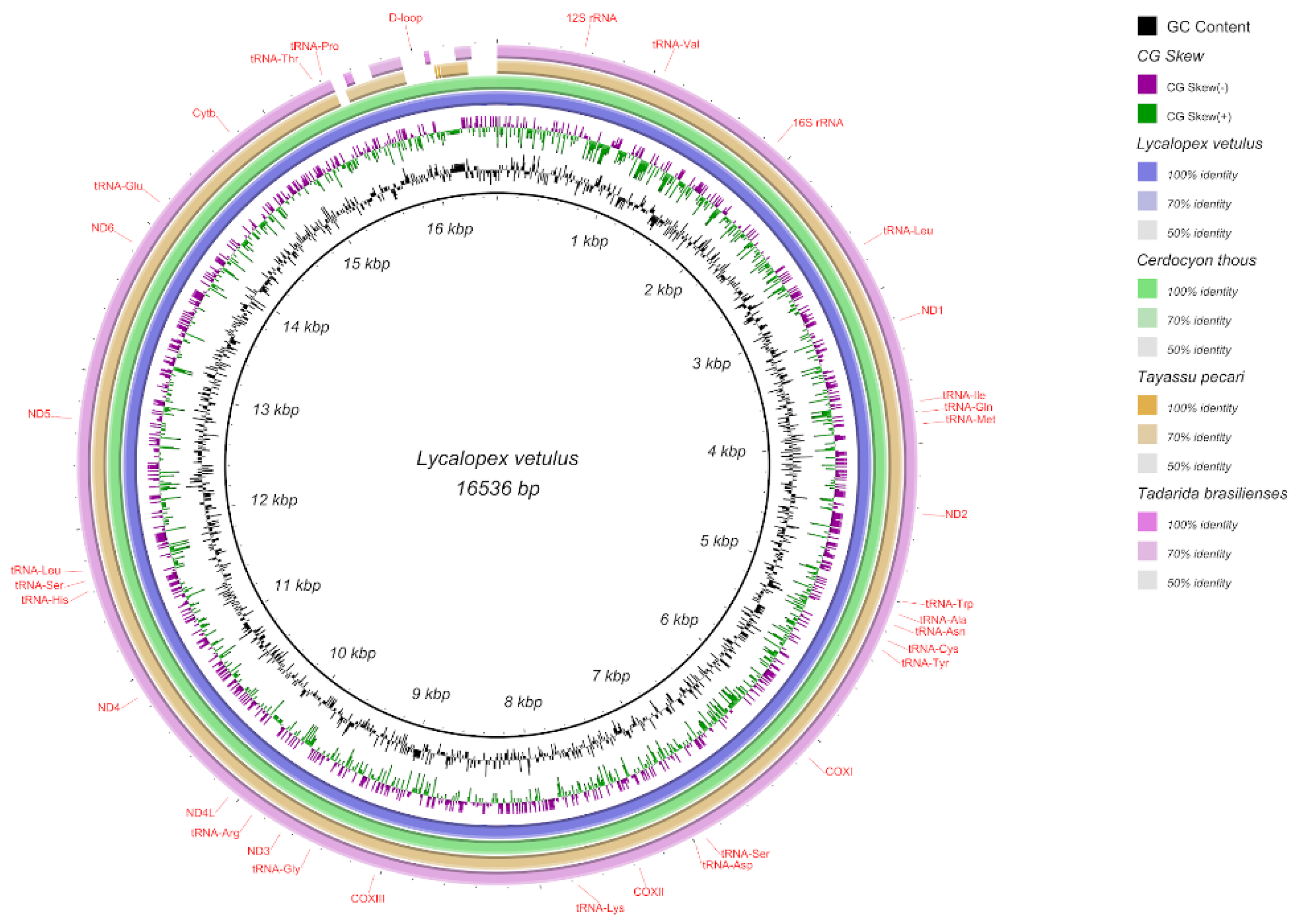

3.2. Assembling, Annotation, and Analysis of Mitochondrial Genomes

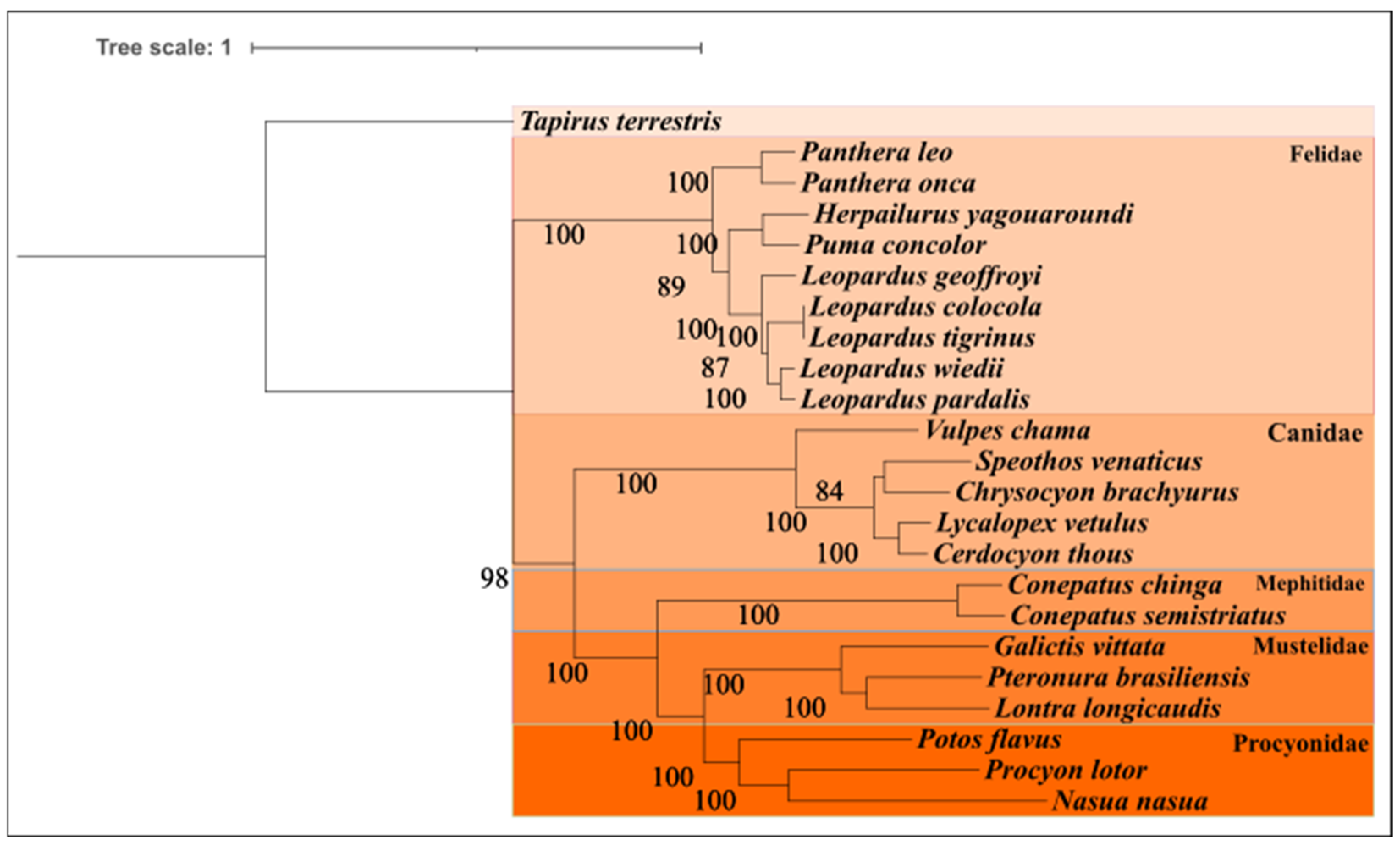

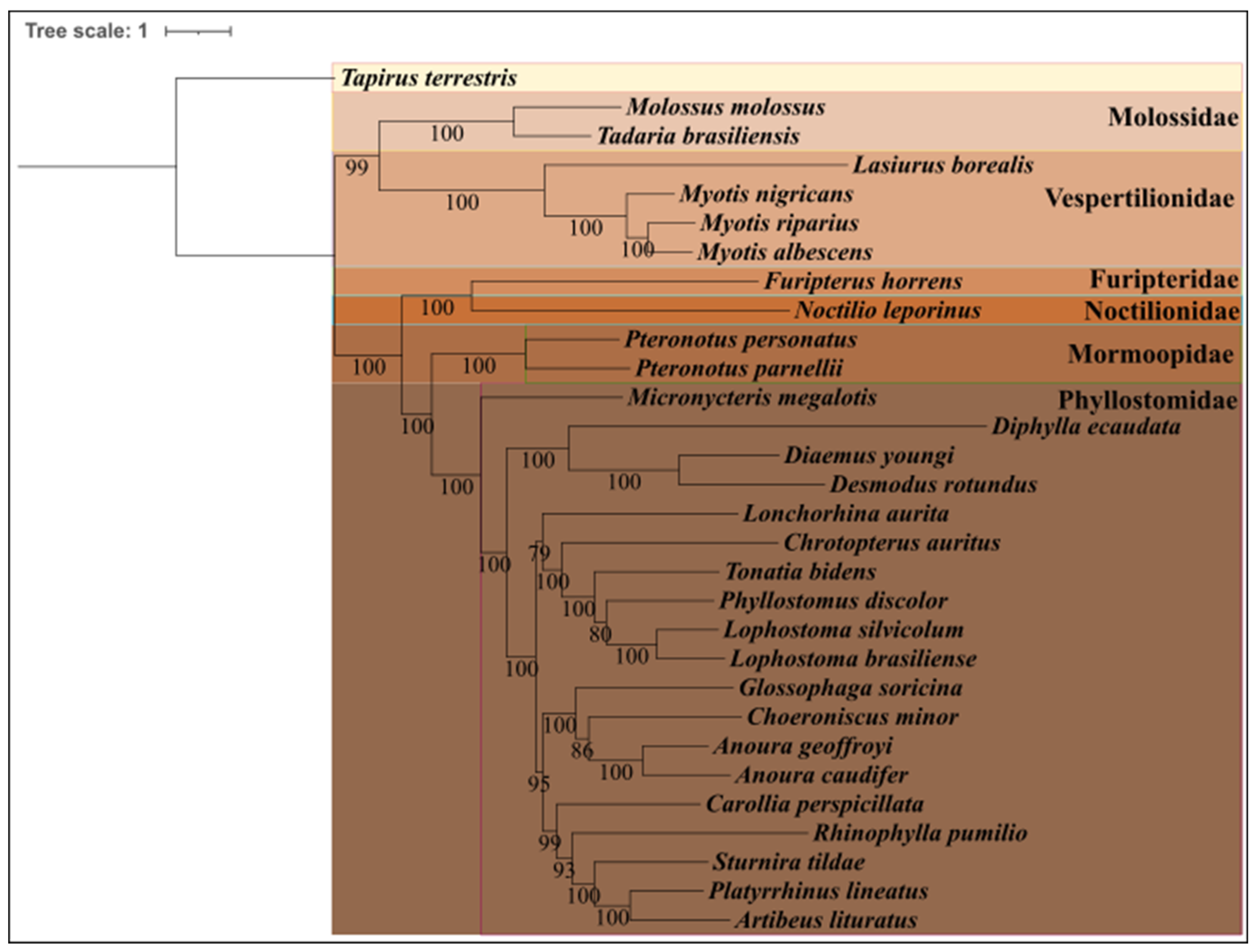

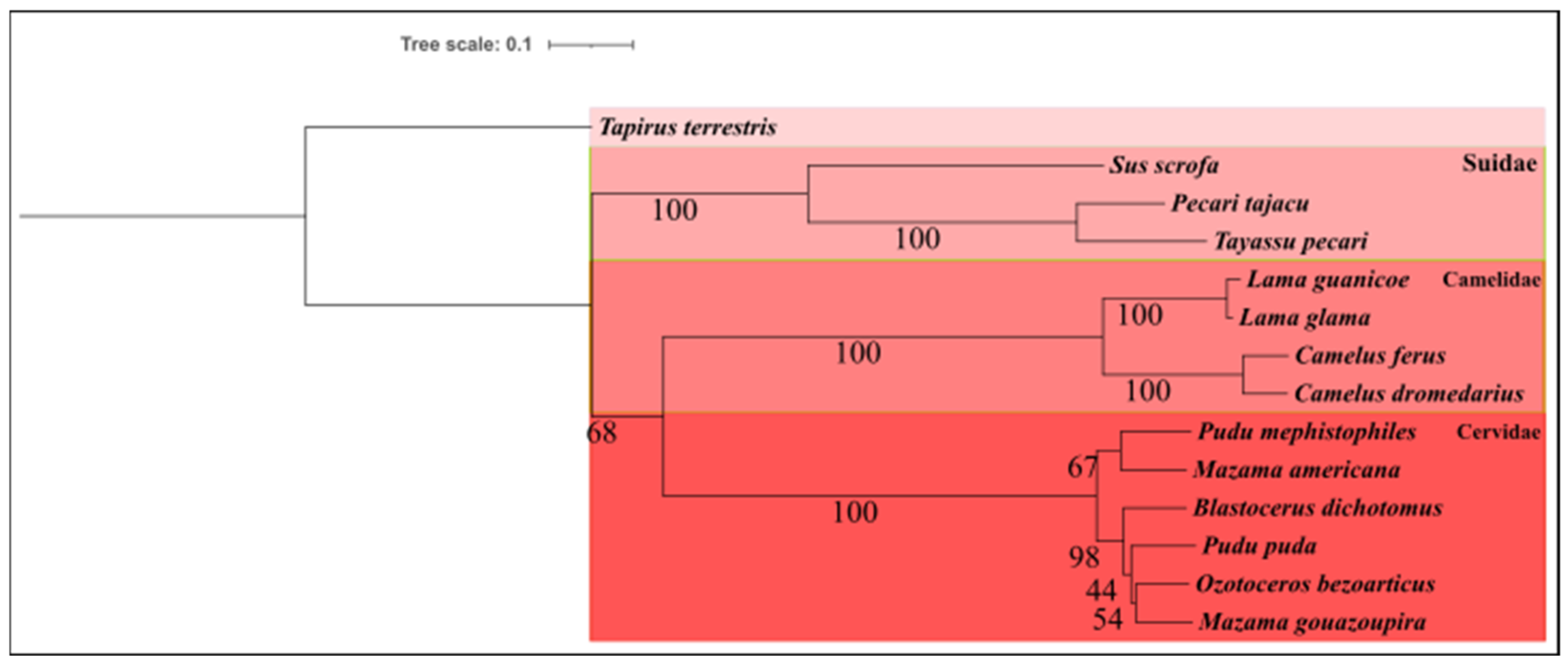

3.2. Phylogenetic Analysis

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Klink, C.A.; Machado, R.B. Conservation of the Brazilian Cerrado. Conserv. Biol. 2005, 19, 707–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vieira, L.T.A.; Azevedo, T.N.; Castro, A.A.J.F.; Martins, F.R. Reviewing the Cerrado’s Limits, Flora Distribution Patterns, and Conservation Status for Policy Decisions. Land Use Policy 2022, 115, 106038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues, A.A.; Macedo, M.N.; Silvério, D.V.; Maracahipes, L.; Coe, M.T.; Brando, P.M.; Shimbo, J.Z.; Rajão, R.; Soares-Filho, B.; Bustamante, M.M.C. Cerrado Deforestation Threatens Regional Climate and Water Availability for Agriculture and Ecosystems. Glob. Change Biol. 2022, 28, 6807–6822. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Latrubesse, E.M.; Arima, E.; Ferreira, M.E.; Nogueira, S.H.; Wittmann, F.; Dias, M.S.; Dagosta, F.C.P.; Bayer, M. Fostering Water Resource Governance and Conservation in the Brazilian Cerrado Biome. Conserv. Sci. Pract. 2019, 1, e77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L.t.a, V.; T.n, A.; A.a.j.f, C.; F.r, M. Reviewing the Cerrado’s limits, flora distribution patterns, and conservation status for policy decisions. 2022.

- Strassburg, B.B.N.; Brooks, T.; Feltran-Barbieri, R.; Iribarrem, A.; Crouzeilles, R.; Loyola, R.; Latawiec, A.E.; Oliveira Filho, F.J.B.; Scaramuzza, C.A. de M.; Scarano, F.R.; et al. Moment of Truth for the Cerrado Hotspot. Nat. Ecol. Evol. 2017, 1, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Fire Factor. In The Cerrados of Brazil; Oliveira, P., Marquis, R., Eds.; Columbia University Press, 2002; pp. 51–68 ISBN 978-0-231-52939-6.

- Medeiros, M.B. de; Fiedler, N.C. Incêndios florestais no parque nacional da Serra da Canastra: desafios para a conservação da biodiversidade. Ciênc. Florest. 2004, 14, 157–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durigan, G. Zero-Fire: Not Possible nor Desirable in the Cerrado of Brazil. Flora 2020, 268, 151612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marinho-Filho, J.; Rodrigues, F.H.G.; Juarez, K.M. 14. The Cerrado Mammals: Diversity, Ecology, and Natural History. In The Cerrados of Brazil: Ecology and Natural History of a Neotropical Savanna; Oliveira, P.S., Marquis, R.J., Eds.; Columbia University Press, 2002; pp. 266–284 ISBN 978-0-231-50596-3.

- Gutiérrez, E.E.; Marinho-Filho, J. The Mammalian Faunas Endemic to the Cerrado and the Caatinga. ZooKeys 2017, 644, 105–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roberge, J.-M.; Angelstam, P. Usefulness of the Umbrella Species Concept as a Conservation Tool. Conserv. Biol. 2004, 18, 76–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jepson, P.; Barua, M. A Theory of Flagship Species Action. Conserv. Soc. 2015, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitecek, S.; Kučinić, M.; Previšić, A.; Živić, I.; Stojanović, K.; Keresztes, L.; Bálint, M.; Hoppeler, F.; Waringer, J.; Graf, W.; et al. Integrative Taxonomy by Molecular Species Delimitation: Multi-Locus Data Corroborate a New Species of Balkan Drusinae Micro-Endemics. BMC Evol. Biol. 2017, 17, 129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grabowski, M.; Wysocka, A.; Mamos, T. Molecular Species Delimitation Methods Provide New Insight into Taxonomy of the Endemic Gammarid Species Flock from the Ancient Lake Ohrid. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2017, 181, 272–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinacho-Pinacho, C.D.; Sereno-Uribe, A.L.; García-Varela, M.; Pérez-Ponce de León, G. A Closer Look at the Morphological and Molecular Diversity of Neoechinorhynchus (Acanthocephala) in Middle American Cichlids (Osteichthyes: Cichlidae), with the Description of a New Species from Costa Rica. J. Helminthol. 2018, 94, e23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boore, J.L. Animal Mitochondrial Genomes. Nucleic Acids Res. 1999, 27, 1767–1780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhong, H.-M.; Zhang, H.-H.; Sha, W.-L.; Zhang, C.-D.; Chen, Y.-C. Complete Mitochondrial Genome of the Red Fox (Vuples Vuples) and Phylogenetic Analysis with Other Canid Species: Complete Mitochondrial Genome of the Red Fox (Vuples Vuples) and Phylogenetic Analysis with Other Canid Species. Zool. Res. 2010, 31, 122–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Formenti, G.; Rhie, A.; Balacco, J.; Haase, B.; Mountcastle, J.; Fedrigo, O.; Brown, S.; Capodiferro, M.R.; Al-Ajli, F.O.; Ambrosini, R.; et al. Complete Vertebrate Mitogenomes Reveal Widespread Repeats and Gene Duplications. Genome Biol. 2021, 22, 120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.R. The Past, Present and Future of Mitochondrial Genomics: Have We Sequenced Enough mtDNAs? Brief. Funct. Genomics 2016, 15, 47–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ICMBio Lista Oficial de Espécies Da Fauna Brasileira Ameaçadas de Extinção.; 2014.

- Jalili, V.; Afgan, E.; Gu, Q.; Clements, D.; Blankenberg, D.; Goecks, J.; Taylor, J.; Nekrutenko, A. The Galaxy Platform for Accessible, Reproducible and Collaborative Biomedical Analyses: 2020 Update. Nucleic Acids Res. 2020, 48, W395–W402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dierckxsens, N.; Mardulyn, P.; Smits, G. NOVOPlasty: De Novo Assembly of Organelle Genomes from Whole Genome Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2017, 45, e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iwasaki, W.; Fukunaga, T.; Isagozawa, R.; Yamada, K.; Maeda, Y.; Satoh, T.P.; Sado, T.; Mabuchi, K.; Takeshima, H.; Miya, M.; et al. MitoFish and MitoAnnotator: A Mitochondrial Genome Database of Fish with an Accurate and Automatic Annotation Pipeline. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2531–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, G.; Li, Y.; Yang, C.; Liu, S. MitoZ: A Toolkit for Animal Mitochondrial Genome Assembly, Annotation and Visualization. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, e63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gruber, A.R.; Lorenz, R.; Bernhart, S.H.; Neuböck, R.; Hofacker, I.L. The Vienna RNA Websuite. Nucleic Acids Res. 2008, 36, W70–W74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Silva, I.B.; Menegídio, F.B.; Garcia, C.; Kavalco, K.F.; Pasa, R. Genetic Chronicle of the Capybara: The Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Hydrochoerus Hydrochaeris. Mamm. Biol. 2024, 104, 459–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Misawa, K.; Kuma, K.; Miyata, T. MAFFT: A Novel Method for Rapid Multiple Sequence Alignment Based on Fast Fourier Transform. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, 3059–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vences, M.; Patmanidis, S.; Kharchev, V.; Renner, S.S. Concatenator, a User-Friendly Program to Concatenate DNA Sequences, Implementing Graphical User Interfaces for MAFFT and FastTree. Bioinforma. Adv. 2022, 2, vbac050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trifinopoulos, J.; Nguyen, L.-T.; von Haeseler, A.; Minh, B.Q. W-IQ-TREE: A Fast Online Phylogenetic Tool for Maximum Likelihood Analysis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2016, 44, W232–235. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, R.J.; Patton, J.; Genoways, H.; Bickham, J. Genic Studies of Lasiurus (Chiroptera, Vespertilionidae) /; Texas Tech University Press,: Lubbock, Tex. :, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Pavan, A.C.; Marroig, G. Integrating Multiple Evidences in Taxonomy: Species Diversity and Phylogeny of Mustached Bats (Mormoopidae: Pteronotus). Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2016, 103, 184–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olifiers, N.; Delciellos, A. New Record of Lycalopex Vetulus (Carnivora, Canidae) in Northeastern Brazil. Oecologia Aust. 2013, 17, 533–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- VELAZCO, P.M.; GARDNER, A.L.; PATTERSON, B.D. Systematics of the Platyrrhinus Helleri Species Complex (Chiroptera: Phyllostomidae), with Descriptions of Two New Species. Zool. J. Linn. Soc. 2010, 159, 785–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mares, M.A.; Willig, M.R.; Lacher, T.E. The Brazilian Caatinga in South American Zoogeography: Tropical Mammals in a Dry Region. J. Biogeogr. 1985, 12, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nascimento, F.F.; Lazar, A.; Menezes, A.N.; Durans, A. da M.; Moreira, J.C.; Salazar-Bravo, J.; D′Andrea, P.S.; Bonvicino, C.R. The Role of Historical Barriers in the Diversification Processes in Open Vegetation Formations during the Miocene/Pliocene Using an Ancient Rodent Lineage as a Model. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e61924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bezerra, A.M.R.; Marinho-Filho, J.; Carmignotto, A.P. A Review of the Distribution, Morphometrics, and Habit of Owl’s Spiny Rat Carterodon Sulcidens (Lund, 1841) (Rodentia: Echimyidae).

- Miotto, R.A.; Rodrigues, F.P.; Ciocheti, G.; Galetti Jr, P.M. Determination of the Minimum Population Size of Pumas (Puma Concolor) Through Fecal DNA Analysis in Two Protected Cerrado Areas in the Brazilian Southeast. Biotropica 2007, 39, 647–654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janis, C.M.; Pough, F.H.; Heiser, J.B. A Vida Dos Vertebrados; Atheneu, 2007; ISBN 978-85-7454-095-5.

- Hofmann, G.S.; Cardoso, M.F.; Alves, R.J.V.; Weber, E.J.; Barbosa, A.A.; de Toledo, P.M.; Pontual, F.B.; Salles, L. de O.; Hasenack, H.; Cordeiro, J.L.P.; et al. The Brazilian Cerrado Is Becoming Hotter and Drier. Glob. Change Biol. 2021, 27, 4060–4073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- ICMBio Cerrado - Plano de Ação Nacional Para Conservação Dos Mamíferos Do Cerrado; 2019.

- ICMbio Plano de Ação Nacional Para Pequenos Mamíferos de Áreas Abertas; 2024.

- Quintela, F.M.; Da Rosa, C.A.; Feijó, A. Updated and Annotated Checklist of Recent Mammals from Brazil. An. Acad. Bras. Ciênc. 2020, 92, e20191004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnusson, W.E. Neotropical Rainforest Mammals: A Field Guide. Environ. Conserv. 1998, 25, 175–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skorupski, J. Characterisation of the Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Critically Endangered Mustela Lutreola (Carnivora: Mustelidae) and Its Phylogenetic and Conservation Implications. Genes 2022, 13, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wei, Q.; Wang, X.; Dong, Y.; Shang, Y.; Sun, G.; Wu, X.; Zhao, C.; Sha, W.; Yang, G.; Zhang, H. Analysis of the Complete Mitochondrial Genome of Pteronura Brasiliensis and Lontra Canadensis. Animals 2023, 13, 3165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tchaicka, L.; Freitas, T.R.O. de; Bager, A.; Luengos Vidal, S.; Lucherini, M.; Iriarte, A.; Novaro, A.; Geffen, E.; Garcez, F.S.; Johnson, W.E.; et al. Molecular Assessment of the Phylogeny and Biogeography of a Recently Diversified Endemic Group of South American Canids (Mammalia: Carnivora: Canidae). 2016.

- Zhao, C.; Zhang, H.; Liu, G.; Yang, X.; Zhang, J. The complete mitochondrial genome of the Tibetan fox (Vulpes ferrilata) and implications for the phylogeny of Canidae. C. R. Biol. 2016, 339, 68–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gregorin, R.; Cirranello, A. Phylogeny of Molossidae Gervais (Mammalia: Chiroptera) Inferred by Morphological Data. Cladistics 2016, 32, 2–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsagkogeorga, G.; Parker, J.; Stupka, E.; Cotton, J.A.; Rossiter, S.J. Phylogenomic Analyses Elucidate the Evolutionary Relationships of Bats. Curr. Biol. CB 2013, 23, 2262–2267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parisi Dutra, R.; Casali, D.D.M.; Missagia, R.V.; Gasparini, G.M.; Perini, F.A.; Cozzuol, M.A. Phylogenetic Systematics of Peccaries (Tayassuidae: Artiodactyla) and a Classification of South American Tayassuids. J. Mamm. Evol. 2017, 24, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zurano, J.P.; Magalhães, F.M.; Asato, A.E.; Silva, G.; Bidau, C.J.; Mesquita, D.O.; Costa, G.C. Cetartiodactyla: Updating a Time-Calibrated Molecular Phylogeny. Mol. Phylogenet. Evol. 2019, 133, 256–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Family | Species | Status and Year IUCN | Status and Year ICMBio | GenBank access |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bradypodidae | Bradypus variegatus (Schinz, 1825) | LC (2022) | LC (2018) | NC_028501.1 |

| Callithrichidae | Callithrix penicillata (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1812) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | NC_030788.1 |

| Callithrichidae | Mico melanurus (É. Geoffroy in Humboldt, 1812) | LC (2016) | LC (2019) | - |

| Canidae | Cerdocyon thous (Linnaeus, 1766) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Canidae | Chrysocyon brachyurus (Illiger, 1815) | NT (2015) | VU (2023) | NC_024172.1 |

| Canidae | Lycalopex vetulus (Lund, 1842) | NT (2019) | VU (2023) | - |

| Canidae | Speothos venaticus (Lund, 1842) | NT (2011) | VU (2023) | NC_053974.1 |

| Caviidae | Cavia aperea (Erxleben, 1777) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | NC_046949.1 |

| Caviidae | Galea spixii (Wagler, 1831) | LC (2016) | LC (2021) | - |

| Caviidae | Kerodon acrobata (Moojen, Locks & Langguth, 1997)* | DD (2016) | VU (2023) | - |

| Cebidae | Alouatta caraya (Humboldt, 1812) | NT (2015) | NT (2012) | NC_064185.1 |

| Cebidae | Aotus infulatus (Kühl, 1820) | - | LC (2012) | KC592390.1 |

| Cebidae | Sapajus apella (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | NC_064167.1 |

| Cebidae | Sapajus libidinosus (Spix, 1823) | NT (2015) | NT (2012) | NC_087899.1 |

| Cervidae | Blastocerus dichotomus (Illiger, 1815) | VU (2016) | VU (2023) | NC_020682.1 |

| Cervidae | Mazama americana (Erxleben, 1777) | DD (2015) | DD (2018) | NC_020719.1 |

| Cervidae | Subulo gouazoubira (Smith,1827) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_020720.1 |

| Cervidae | Ozotoceros bezoarticus (Linnaeus, 1758) | NT (2015) | VU (2023) | NC_020766.1 |

| Chlamyphoridae | Euphractus sexcinctus (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2013) | LC (2018) | NC_028571.1 |

| Chlamyphoridae | Tolypeutes tricinctus (Linnaeus, 1758) | VU (2013) | EN (2023) | NC_028576.1 |

| Cricetidae | Akodon cursor (Winge, 1887) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Akodon lindberghi (Hershkovitz, 1990) | DD (2016) | LC (2021) | - |

| Cricetidae | Akodon montensis (Thomas, 1913) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | NC_025746.1 |

| Cricetidae | Bibimys labiosus (Winge, 1887) | LC (2016) | LC (2021) | - |

| Cricetidae | Calassomys apicalis (Pardiñas, Lessa, Teta, Salazar-Bravo & Camara, 2014)* | - | NT (2021) | - |

| Cricetidae | Calomys callosus (Rengger, 1830) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Calomys expulsus (Lund, 1840) | LC (2016) | LC (2021) | - |

| Cricetidae | Calomys laucha (G. Fischer, 1814) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Calomys tener (Winge, 1887) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Calomys tocantinsi (Bonvicino, Lima & Almeida, 2003) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Cerradomys marinhus (Bonvicino, 2003) | LC (2017) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Cerradomys subflavus (Wagner, 1842) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Oecomys roberti (Thomas, 1904) | LC (2016) | LC (2021) | NC_065749.1 |

| Cricetidae | Euryoryzomys lamia (Thomas, 1901)* | VU (2017) | EN (2023) | - |

| Cricetidae | Gyldenstolpia planaltensis (Avila-Pires, 1972)* | - | EN (2023) | - |

| Cricetidae | Holochilus brasiliensis (Desmarest, 1819) | LC (2016) | LC (2021) | - |

| Cricetidae | Holochilus sciureus (Wagner, 1842) | LC (2016) | LC (2021) | NC_061914.1 |

| Cricetidae | Juscelinomys candango (Moojen, 1965)* | EX (2019) | CR (PEX) (2023) | - |

| Cricetidae | Kunsia tomentosus (Lichtenstein, 1830) | CR (2018) | LC (2021) | - |

| Cricetidae | Microakodontomys transitorius (Hershkovitz, 1993)* | EN (2018) | EN (2023) | - |

| Cricetidae | Necromys lasiurus (Lund, 1841) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Nectomys rattus (Pelzeln, 1883) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Oecomys bicolor (Tomes, 1860) | LC (2016) | LC (2021) | - |

| Cricetidae | Oecomys cleberi (Locks, 1981) | DD (2019) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Oecomys concolor (Wagner, 1845) | LC (2016) | LC (2021) | - |

| Cricetidae | Oligoryzomys moojeni (Weksler & Bonvicino, 2005)* | DD (2017) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Oligoryzomys nigripes (Olfers, 1818) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Oligoryzomys rupestris (Weksler & Bonvicino, 2005)* | DD (2017) | EN (2023) | - |

| Cricetidae | Oligoryzomys stramineus (Bonvicino & Weksler, 1998) | LC (2017) | LC (2020) | NC_039723.1 |

| Cricetidae | Hylaeamys megacephalus (G. Fischer, 1814) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Oxymycterus delator (Thomas, 1903) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Pseudoryzomys simplex (Winge, 1887) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Rhipidomys emiliae (J. A. Allen, 1916) | LC (2016) | LC (2021) | - |

| Cricetidae | Rhipidomys macrurus (Gervais, 1855) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Sooretamys angouya (G. Fischer, 1814) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Cricetidae | Thalpomys cerradensis (Hershkovitz, 1990)* | LC (2017) | VU (2023) | - |

| Cricetidae | Thalpomys lasiotis (Thomas, 1916)* | LC (2017) | EN (2023) | - |

| Cricetidae | Wiedomys cerradensis (Gonçalves, Almeida & Bonvicino, 2005) | DD (2017) | LC (2020) | NC_025747.1 |

| Cuniculidae | Cuniculus paca (Linnaeus, 1766) | LC (2016) | LC (2021) | NC_079967.1 |

| Cyclopedidae | Cyclopes didactylus (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2013) | LC (2018) | NC_028564.1 |

| Dasypodidae | Cabassous tatouay (Desmarest, 1804) | LC (2013) | LC (2018) | NC_028558.1 |

| Dasypodidae | Cabassous unicinctus (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2013) | LC (2018) | NC_028559.1 |

| Dasypodidae | Dasypus novemcinctus (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2013) | LC (2018) | NC_001821.1 |

| Dasypodidae | Dasypus septemcinctus (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2013) | LC (2018) | NC_028569.1 |

| Dasypodidae | Priodontes maximus (Kerr, 1792) | VU (2013) | VU (2023) | NC_028573.1 |

| Dasypodidae | Tolypeutes matacus (Desmarest, 1804) | NT (2013) | NT (2018) | NC_028575.1 |

| Dasypodidae | Tolypeutes tricinctus (Linnaeus, 1758) | VU (2013) | EN (2023) | NC_028576.1 |

| Dasyproctidae | Dasyprocta azarae (Lichtenstein, 1823) | DD (2016) | LC (2021) | - |

| Didelphidae | Caluromys lanatus (Olfers, 1818) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Caluromys philander (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Chironees minimus (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2019) | - | |

| Didelphidae | Cryptonanus agricolai (Moojen, 1943) | DD (2016) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Didelphis albiventris (Lund, 1840) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Didelphis aurita (Wied-Neuwied, 1826) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | NC_057515.1 |

| Didelphidae | Didelphis marsupialis (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2016) | LC (2019) | NC_057518.1 |

| Didelphidae | Gracilinanus agilis (Burmeister, 1854) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | NC_054268.1 |

| Didelphidae | Lutreolina crassicaudata (Desmarest, 1804) | LC (2016) | LC (2019) | NC_057520.1 |

| Didelphidae | Marmosa murina (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Marmosops incanus (Lund, 1840) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Marmosops ocellatus (Tate, 1931) | LC (2016) | DD (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Metachirus nudicaudatus (É. Geoffroy, 1803) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | NC_006516.1 |

| Didelphidae | Micoureus constantiae (Thomas, 1904) | LC (2016) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Micoureus demerarae (Thomas, 1905) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Micoureus paraguayanus (Tate, 1931) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Monodelphis americana (Müller, 1776) | LC (2016) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Monodelphis domestica (Wagner, 1842) | LC (2016) | LC (2019) | NC_006299.1 |

| Didelphidae | Monodelphis kunsi (Pine, 1975) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Monodelphis rubida | LC (2016) | - | |

| Didelphidae | Monodelphis umbristriata (Müller, 1776) | LC (2015) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Monodelphis unistriata (Wagner, 1842)* | CR (2016) | DD (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Philander opossum (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2016) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Thylamys karimii (Petter, 1968) | VU (2016) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Thylamys macrurus (Olfers, 1818) | NT (2014) | LC (2019) | - |

| Didelphidae | Thylamys velutinus (Wagner, 1842) | NT (2016) | LC (2019) | - |

| Echimyidae | Carterodon sulcidens (Lund, 1838)* | DD (2016) | DD (2021) | KU892752.1 |

| Echimyidae | Clyomys bishopi (Thomas, 1909) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | - |

| Echimyidae | Clyomys laticeps (Thomas, 1909) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | KU892753.1 |

| Echimyidae | Dactylomys dactylinus (Desmarest, 1817) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | NC_029876.1 |

| Echimyidae | Phyllomys brasiliensis (Lund, 1840)* | EN (2016) | EN (2023) | - |

| Echimyidae | Proechimys longicaudatus (Rengger, 1830) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | NC_020657.1 |

| Echimyidae | Proechimys roberti (Thomas, 1901) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | NC_039420.1 |

| Echimyidae | Thrichomys apereoides (Lund, 1839) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | KU892773.1 |

| Echimyidae | Trinomys albispinus (I. Geoffroy, 1838) | LC (2016) | LC (2021) | KU892761.1 |

| Echimyidae | Trinomys minor (Reis & Pessôa, 1995) | - | - | - |

| Echimyidae | Trinomys moojeni (Pessôa, Oliveira & Reis, 1992) | EN (2016) | EN (2023) | KX650080.1 |

| Emballonuridae | Peropteryx kappleri (Peters, 1867) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Emballonuridae | Peropteryx macrotis (Wagner, 1843) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Emballonuridae | Rhynchonycteris naso (Wied-Neuwied, 1820) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | CM073095.1 |

| Emballonuridae | Saccopteryx bilineata (Temminck, 1838) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | CM072282.1 |

| Emballonuridae | Saccopteryx leptura (Schreber, 1774) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_036421.1 |

| Erethizontidae | Coendou prehensilis (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2016) | NT (2021) | - |

| Felidae | Herpailurus yagouaroundi (É. Geoffroy Saint-Hilaire, 1803) | LC (2014) | VU (2023) | NC_028311.1 |

| Felidae | Leopardus pardalis (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2014) | LC (2018) | NC_028315.1 |

| Felidae | Leopardus tigrinus (Schreber, 1775) | VU (2016) | EN (2023) | NC_028317.1 |

| Felidae | Leopardus wiedii (Schinz, 1821) | NT (2014) | VU (2023) | NC_028318.1 |

| Felidae | Panthera onca (Linnaeus, 1758) | NT (2016) | VU (2023) | NC_022842.1 |

| Felidae | Puma concolor (Linnaeus, 1771) | LC (2014) | NT (2018) | NC_016470.1 |

| Furipteridae | Furipterus horrens (Cuvier, 1828) | LC (2016) | VU (2023) | NC_048476.1 |

| Hydrochaeridae | Hydrochaeris hydrochaeris (Linnaeus, 1766) | LC (2016) | LC (2020) | BK066995.1 |

| Leporidae | Sylvilagus brasiliensis (Linnaeus, 1758) | EN (2018) | DD (2021) | - |

| Molossidae | Eptesicus diminutus (Osgood, 1915) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Eptesicus furinalis (d’Orbigny e Gervais, 1847) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Eumops auripendulus (Shaw, 1800) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Eumops bonariensis (Peters, 1874) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Eumops glaucinus (Wagner, 1843) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Eumops hansae (Sanborn, 1932) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Eumops perotis (Schinz, 1821) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Histiotus velatus (I. Geoffroy, 1824) | DD (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Lasiurus cinereus (Palisot de Beauvois, 1796) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Lasiurus ega (Gervais, 1856) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Cynomops abrasus (Temminck, 1826) | DD (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Neoplatymops mattogrossensis (Vieira, 1942) | LC (2019) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Cynomops planirostris (Peters, 1866) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Molossops temminckii (Burmeister, 1854) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Molossus rufus (É. Geoffroy, 1805) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Molossus molossus (Pallas, 1766) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_065689.1 |

| Molossidae | Nyctinomops aurispinosus (Peale, 1848) | LC (2019) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Nyctinomops laticaudatus (É. Geoffroy, 1805) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Nyctinomops macrotis (Gray, 1840) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Promops nasutus (Spix, 1823) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Rhogeessa tumida (Genoways e Baker, 1996) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Molossidae | Tadarida brasiliensis (I. Geoffroy, 1824) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | CM061282.1 |

| Mormoopidae | Pteronotus gymnonotus (Wagner, 1843) | LC (2018) | LC (2018) | - |

| Mormoopidae | Pteronotus personatus (Wagner, 1843) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | NC_033353.1 |

| Mustelidae | Eira barbara (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Mustelidae | Galictis cuja (Molina, 1782) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Mustelidae | Galictis vittata (Schreber, 1776) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_053973.1 |

| Mustelidae | Lontra longicaudis (Olfers, 1818) | NT (2020) | LC (2018) | NC_079649.1 |

| Mustelidae | Pteronura brasiliensis (Zimmermann, 1780) | EN (2020) | VU (2023) | NC_071787.1 |

| Myrmecophagidae | Myrmecophaga tridactyla (Linnaeus, 1758) | VU (2013) | VU (2023) | NC_028572.1 |

| Myrmecophagidae | Tamandua tetradactyla (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2013) | LC (2018) | NC_004032.1 |

| Natalidae | Natalus macrourus (Gervais, 1856) | LC (2008) | VU (2018) | - |

| Noctilionidae | Noctilio albiventris (Desmarest, 1818) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Noctilionidae | Noctilio leporinus (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_037137.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Anoura caudifer (É. Geoffroy, 1818) | LC (2019) | LC (2018) | NC_022420.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Anoura geoffroyi (Gray, 1838) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | NC_065676.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Dermanura cinerea (Gervais, 1856) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Artibeus concolor (Peters, 1865) | LC(2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Artibeus lituratus (Olfers, 1818) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_016871.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Artibeus planirostris (Spix, 1823) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Carollia perspicillata (Linnaeus, 1758)) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_022422.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Chiroderma trinitatum (Goodwin, 1958) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Chiroderma villosum (Peters, 1860) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Choeroniscus minor (Peters, 1868) | LC(2016) | LC (2018) | NC_065683.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Chrotopterus auritus (Peters, 1856) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_037132.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Desmodus rotundus (É. Geoffroy, 1810) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_022423.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Diaemus youngii (Jentnik, 1893) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_037133.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Diphylla ecaudata (Spix, 1823) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | NC_037138.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Glossophaga soricina (Pallas, 1766) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_065682.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Lonchophylla bokermanni (Sazima, Vizotto e Taddei, 1978) | EN (2016) | VU (2023) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Lonchophylla dekeyseri (Taddei, Vizzotto e Sazima, 1983)* | EN (2016) | EN (2023) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Lonchorhina aurita (Tomes, 1863) | LC (2015) | NT (2018) | NC_037135.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Macrophyllum macrophyllum (Schinz, 1821) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Glyphonycteris behnii (Peters, 1865) | DD (2016) | DD (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Micronycteris megalotis (Gray, 1842) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_022419.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Micronycteris minuta (Gervais, 1856) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Micronycteris sanborni (Simmons, 1996) | LC (2017) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Mimon bennettii (Gray, 1838) | LC (2018) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Gardnerycteris crenulatum (É. Geoffroy, 1803) | LC (2018) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Phylloderma stenops (Peters, 1865) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Phyllostomus discolor (Wagner, 1843) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_065690.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Phyllostomus elongatus (É. Geoffroy, 1810) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Phyllostomus hastatus (Pallas, 1767) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Platyrrhinus lineatus (É. Geoffroy, 1810) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | ON357734.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Rhinophylla pumilio (Peters, 1865) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_022426.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Sturnira lilium (É. Geoffroy, 1810) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Sturnira tildae (de la Torre, 1959) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | NC_022427.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Tonatia bidens (Spix, 1823) | DD (2016) | LC (2018) | MZ391834.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Lophostoma brasiliense (Peters, 1866) | LC (2016) | LC (2018) | NC_065678.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Lophostoma silvicola (d’Orbigny, 1836) | LC(2016) | LC (2018) | NC_022424.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Trachops cirrhosus (Spix, 1823) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_086900.1 |

| Phyllostomidae | Uroderma bilobatum (Peters, 1866) | LC (2019) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Uroderma magnirostrum (Davis, 1968) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Phyllostomidae | Vampyressa pusilla (Wagner, 1843) | DD (2016) | LC (2018) | - |

| Procyonidae | Nasua nasua (Linnaeus, 1766) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_020647.1 |

| Procyonidae | Potos flavus (Schreber, 1774) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_053977.1 |

| Procyonidae | Procyon cancrivorus (G. Cuvier, 1798) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | PP999026.1 |

| Tapiridae | Tapirus terrestris (Linnaeus, 1758) | VU (2018) | VU (2023) | NC_053962.1 |

| Tayassuidae | Pecari tajacu (Linnaeus, 1758) | LC (2011) | LC (2018) | NC_012103.1 |

| Tayassuidae | Tayassu pecari (Link, 1795) | VU (2012) | VU (2023) | - |

| Vespertilionidae | Eptesicus brasiliensis (Desmarest, 1819) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | - |

| Vespertilionidae | Myotis albescens (É. Geoffroy, 1806) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_036327.1 |

| Vespertilionidae | Myotis nigricans (Schinz, 1821) | LC (2019) | LC (2018) | NC_036318.1 |

| Vespertilionidae | Myotis riparius (Handley, 1960) | LC (2015) | LC (2018) | NC_036317.1 |

| Status abbreviations—DD: Data Deficient; LC: Least Concern; NT: Near Threatened; EN: Endangered; CR: Critically Endangered; *Brazilian Cerrado endemic species | ||||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).