Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

24 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Screening for Active Ingredients and Gastric Cancer Targets

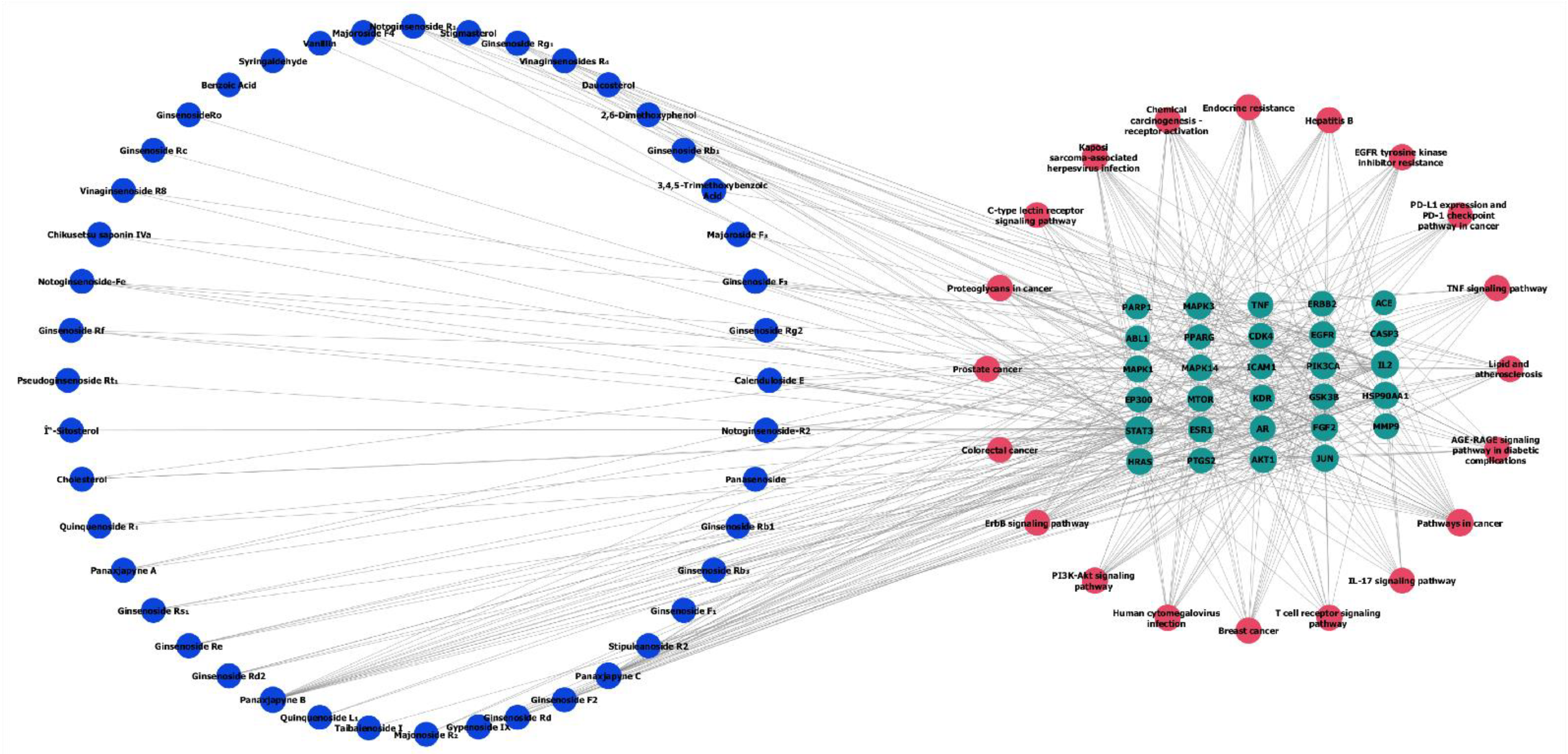

2.2. Main Components and Targets Associated with Gastric Cancer

2.3. Potential Functions and Pathways Associated with Targets for GC Treatment

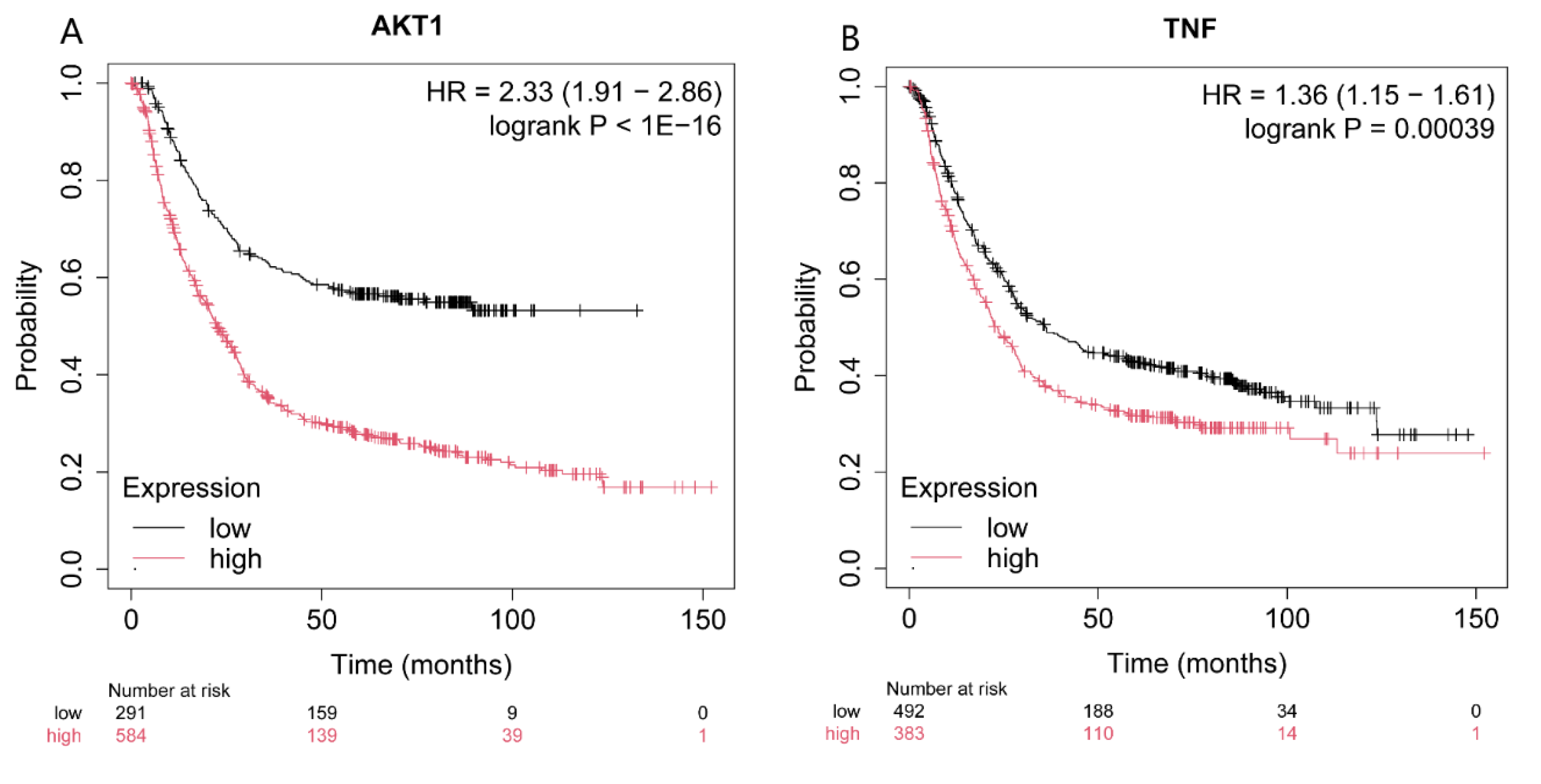

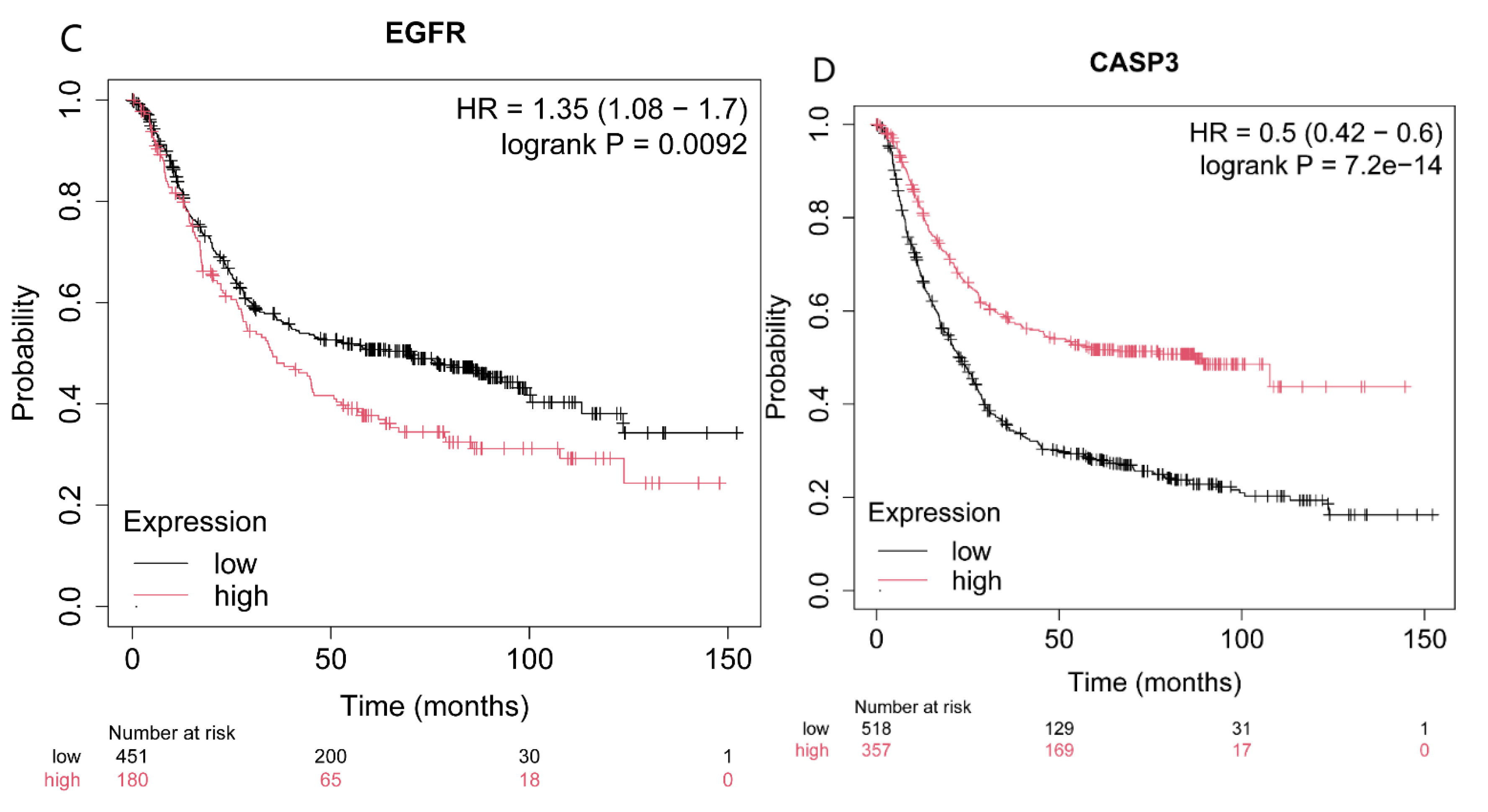

2.4. Effect on Four Genes Expression Associated with Patients’ Survival Period

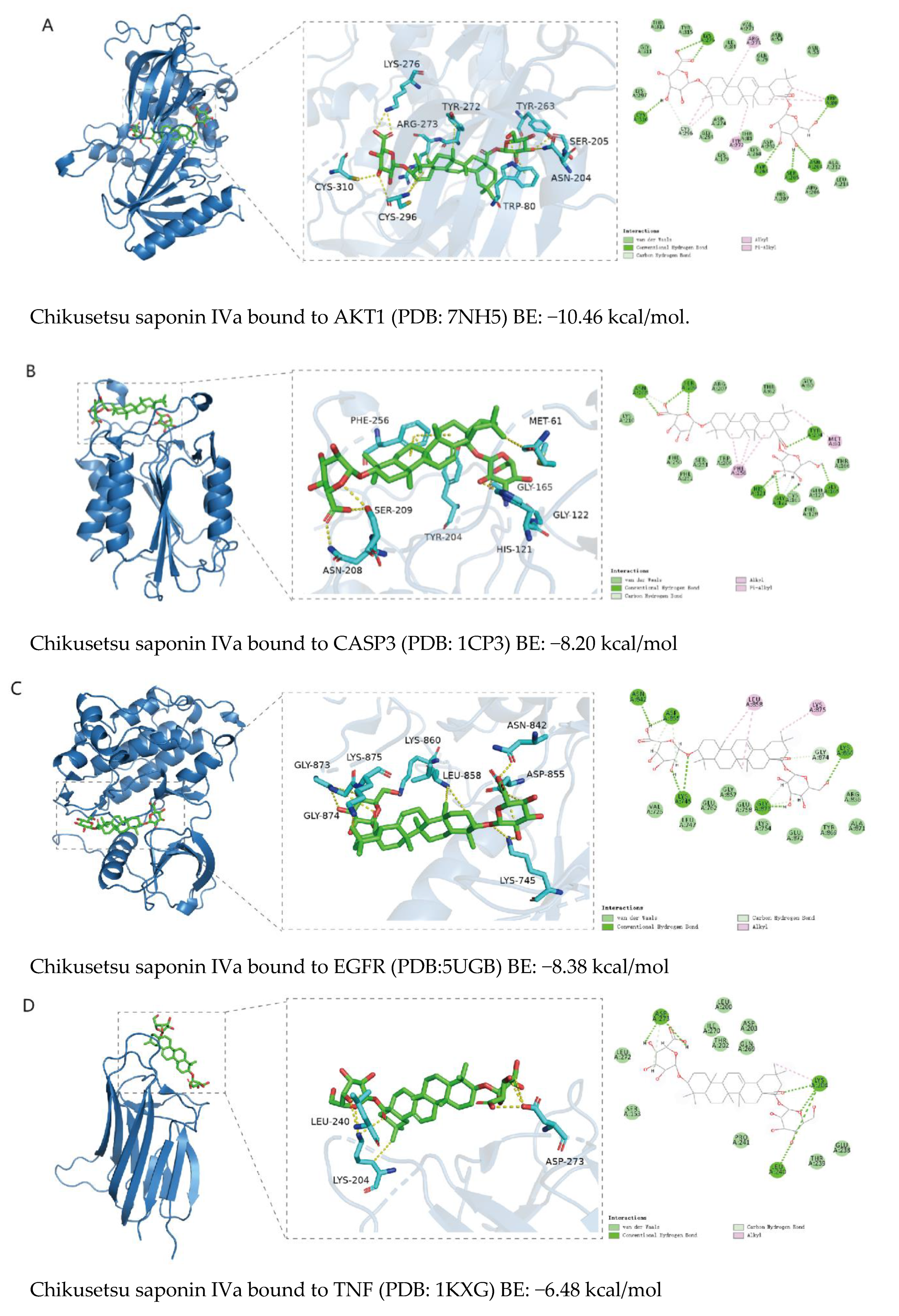

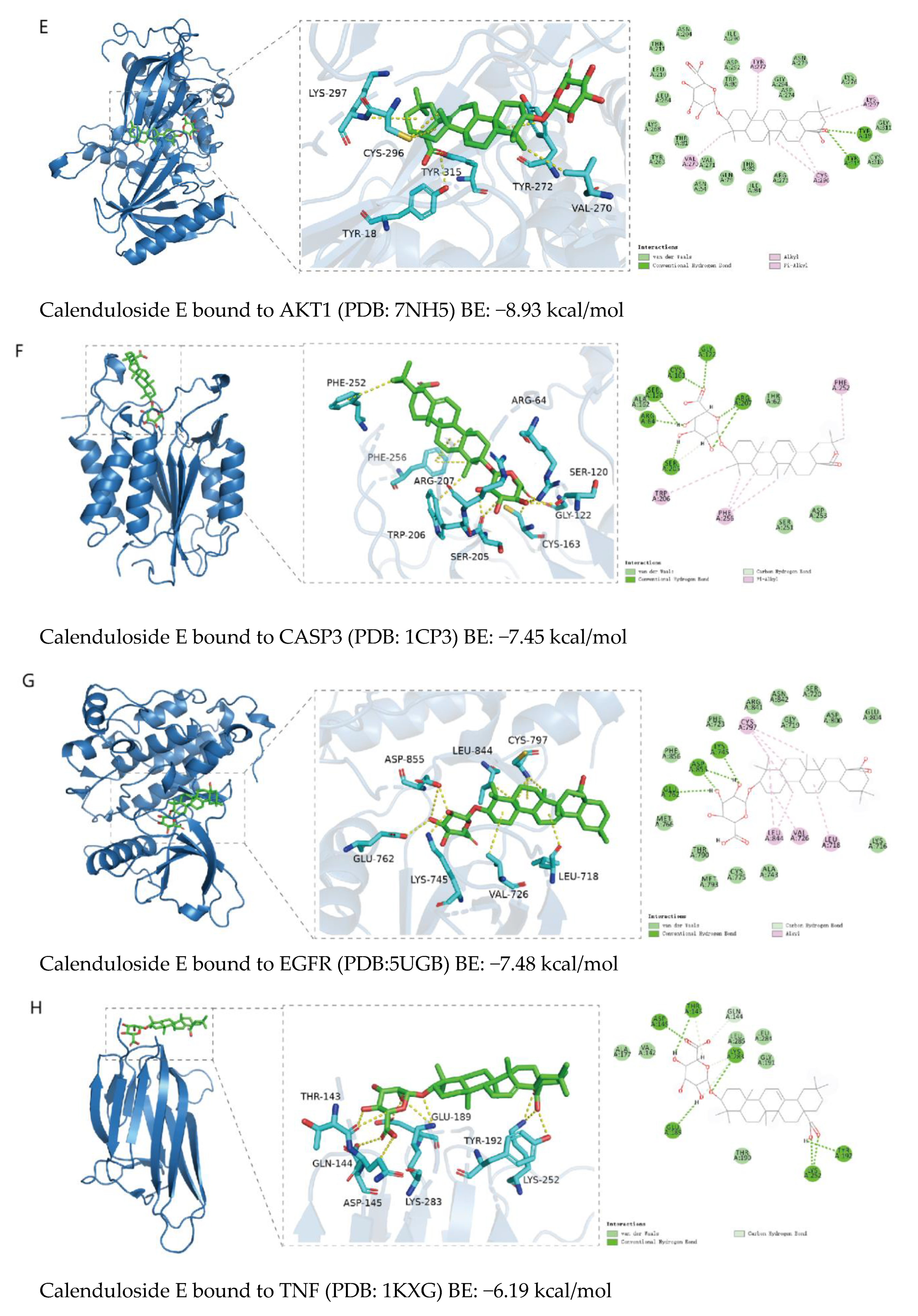

2.5. Binding Ability Between Main Active Compounds and Protein Targets

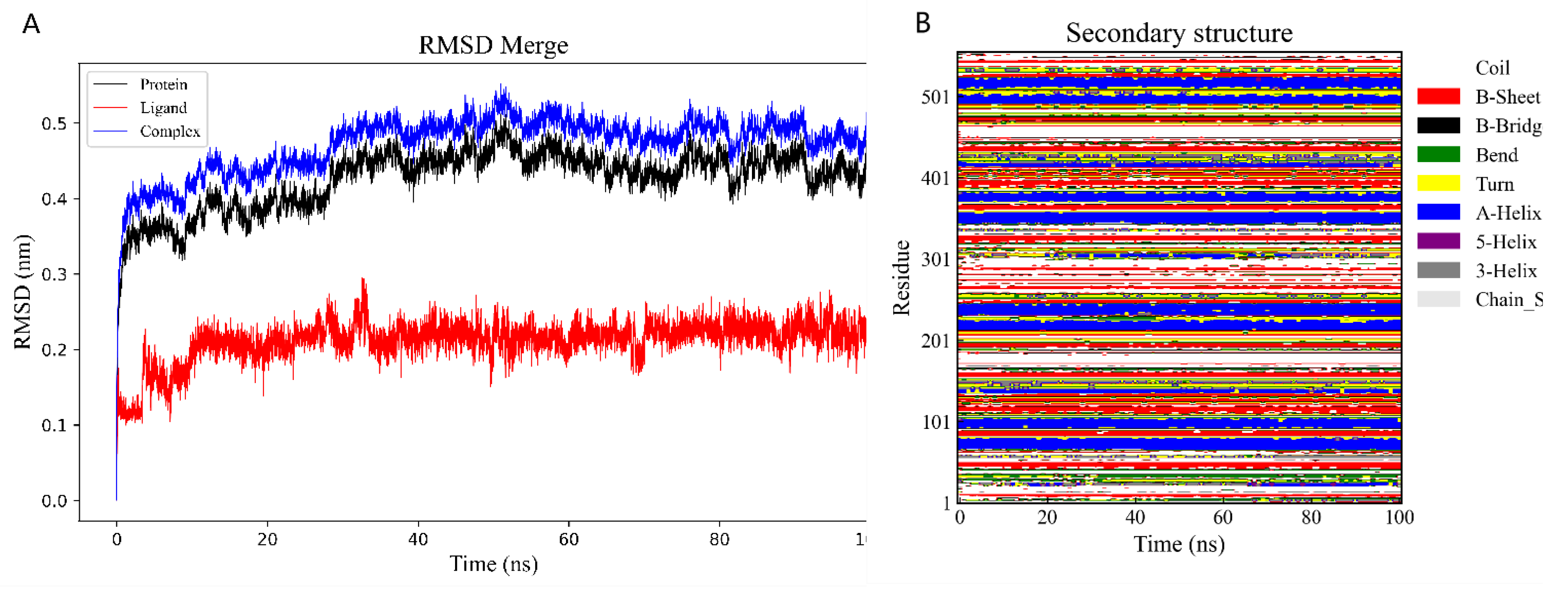

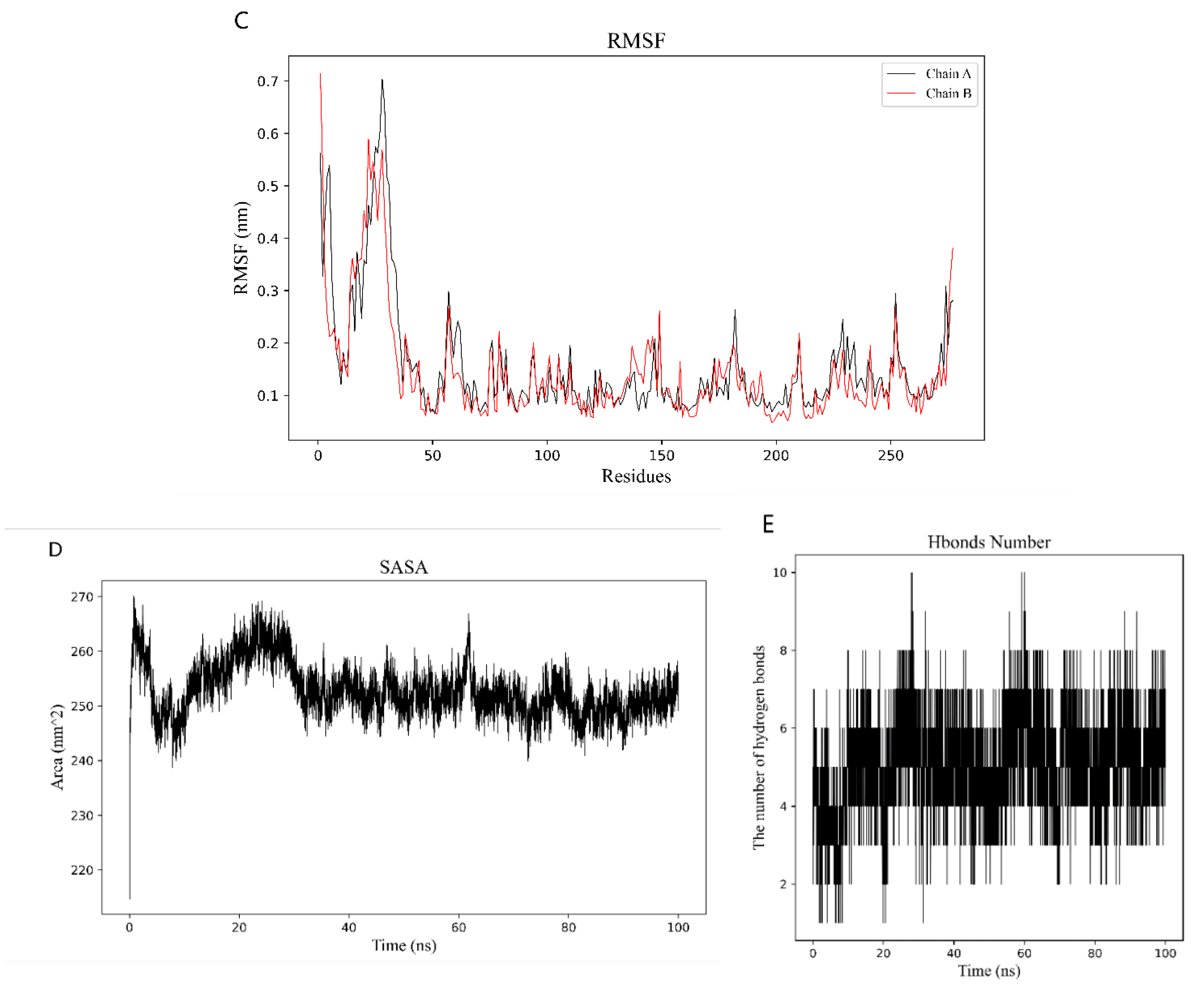

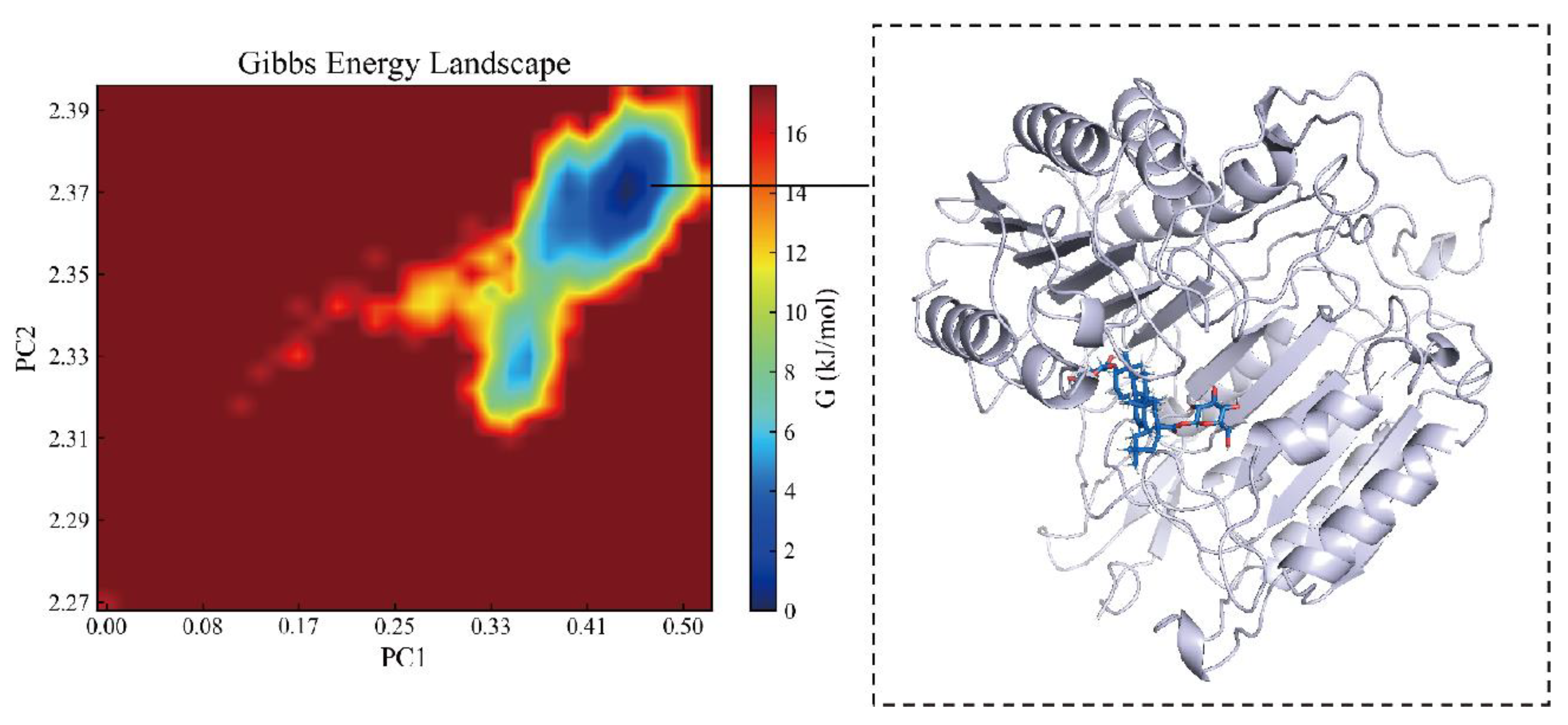

2.6. Binding Energy and Stability of Chikusetsu Saponin IVa–CASP3

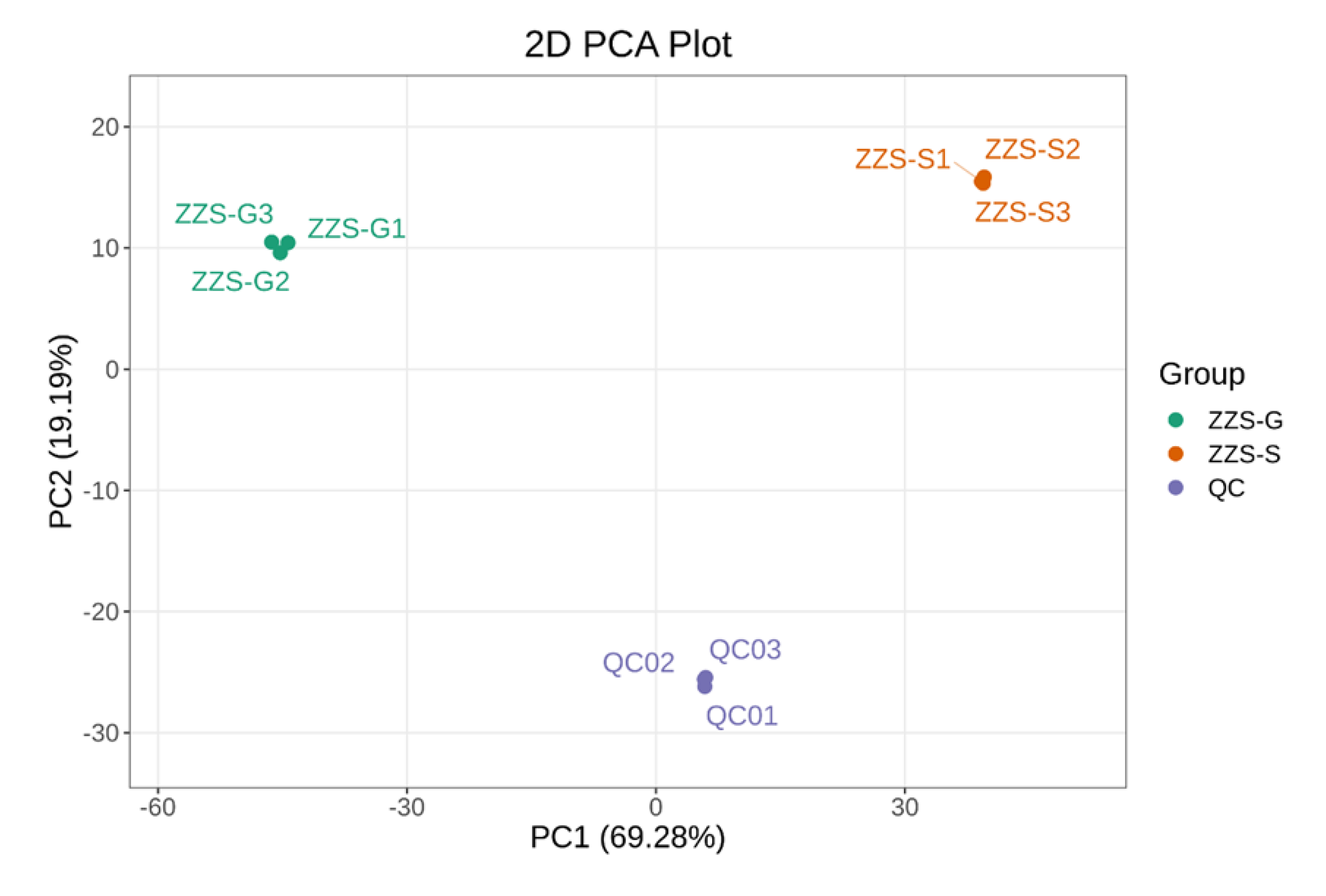

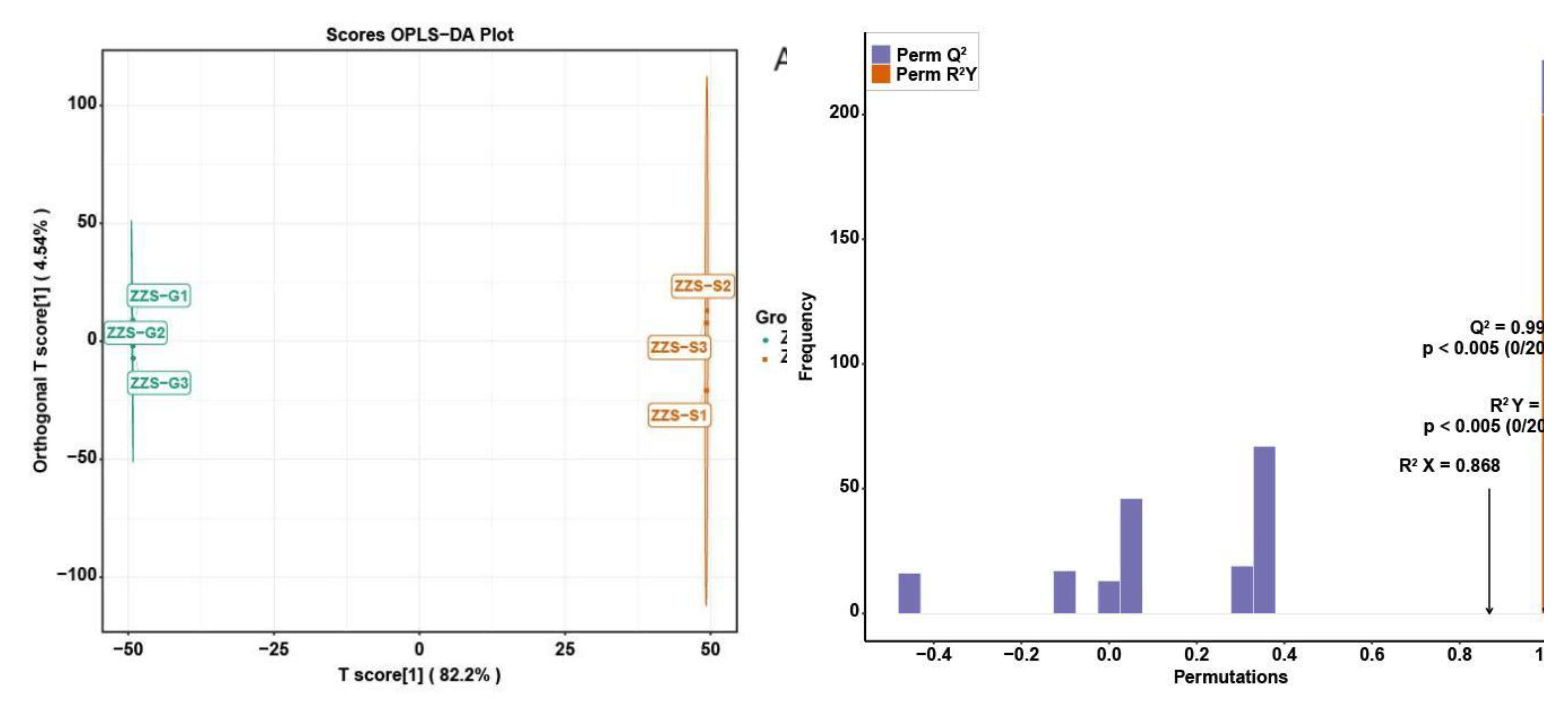

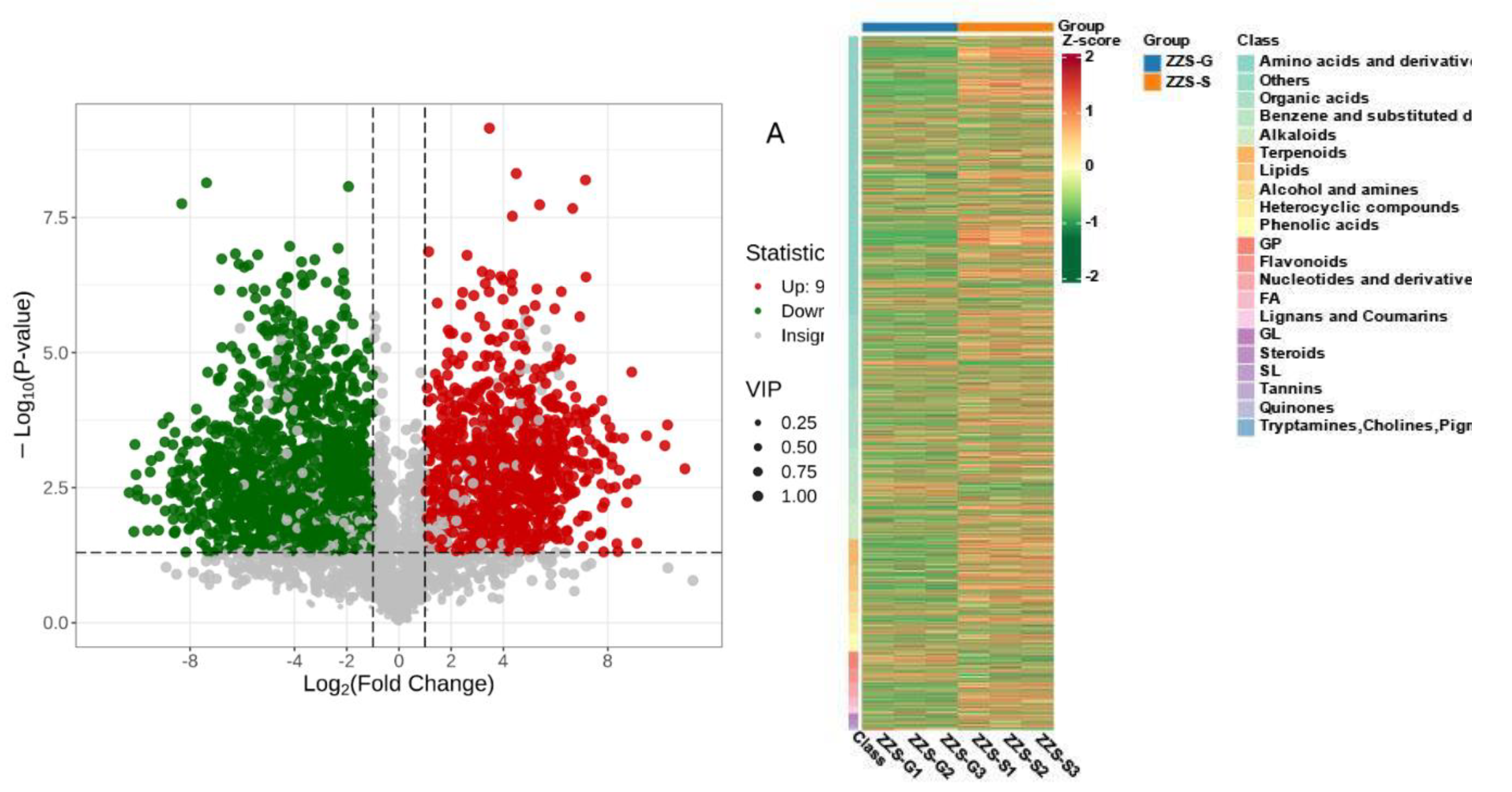

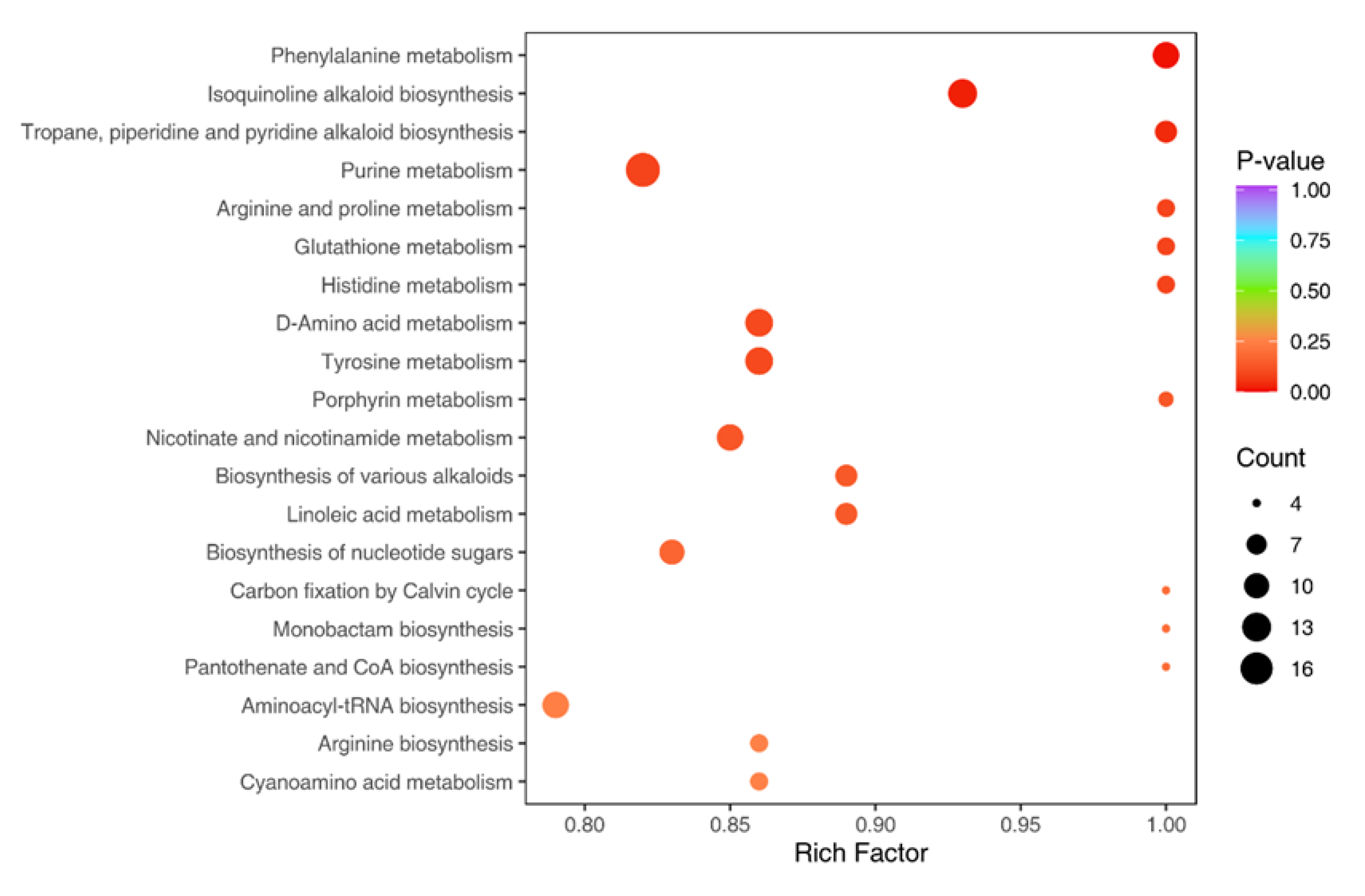

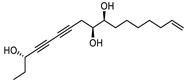

2.7. Analysis of Major Components and Differential Metabolites in Panax japonicus

2.8. MTS Experimental Results Analysis

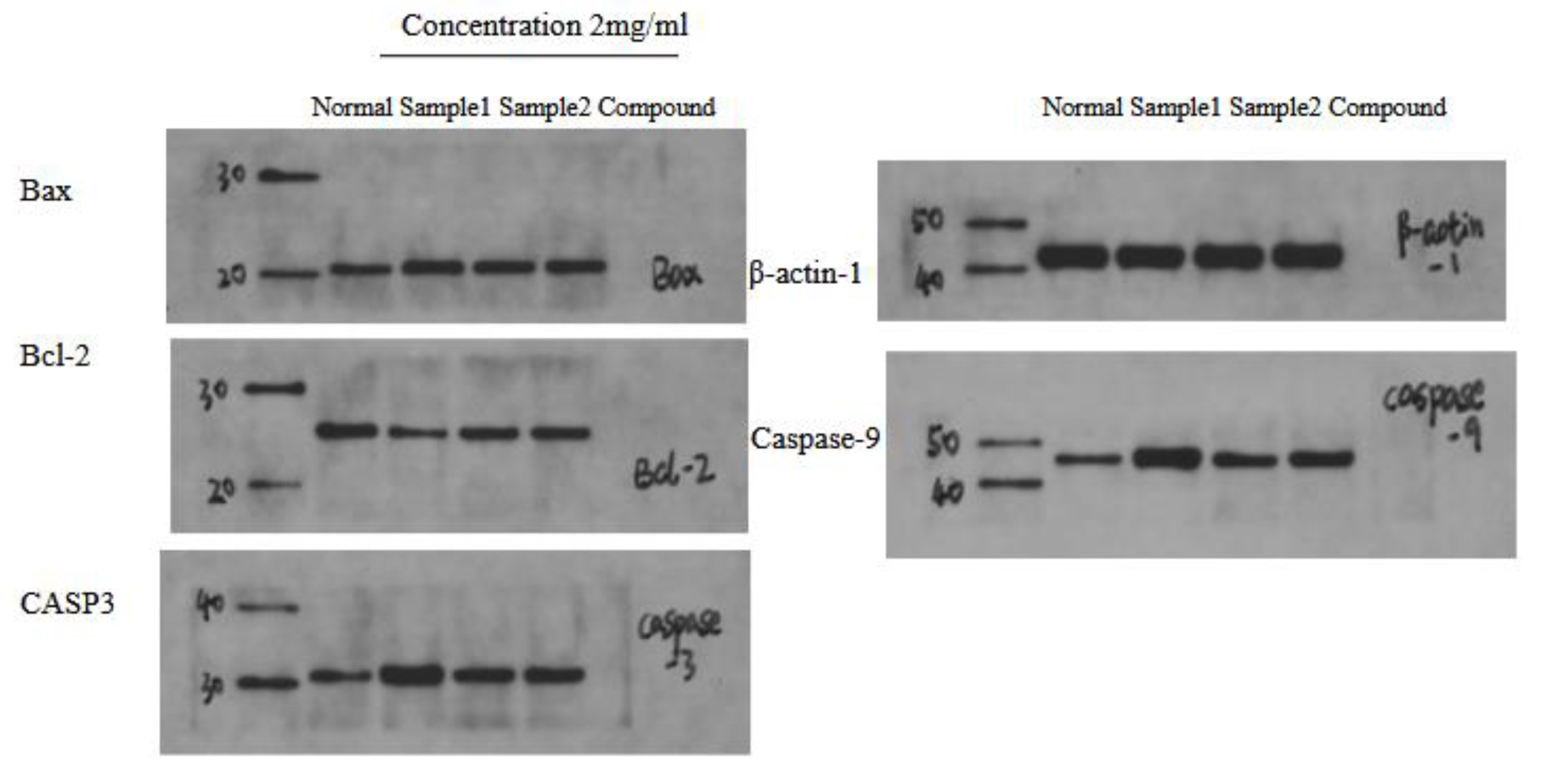

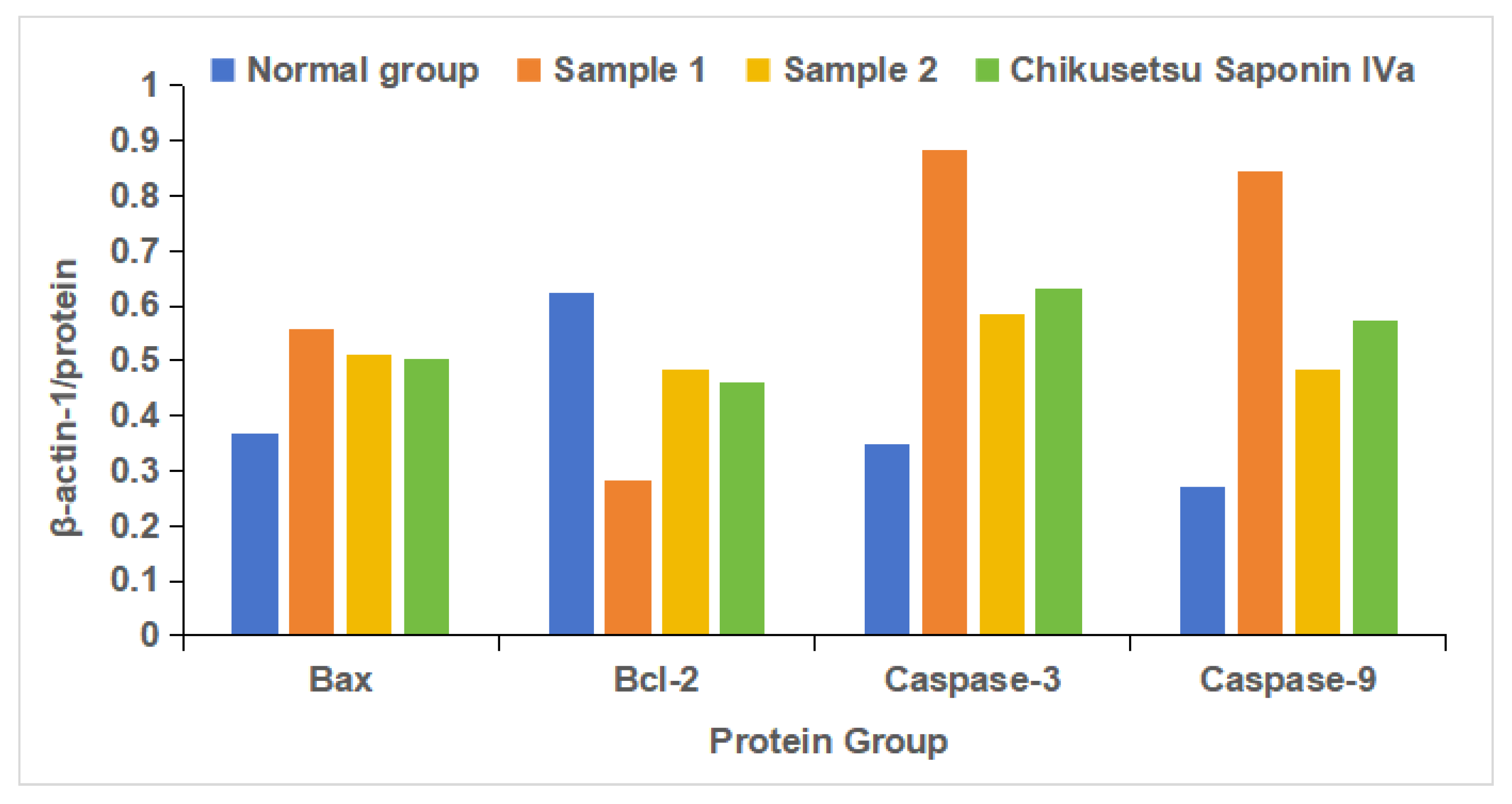

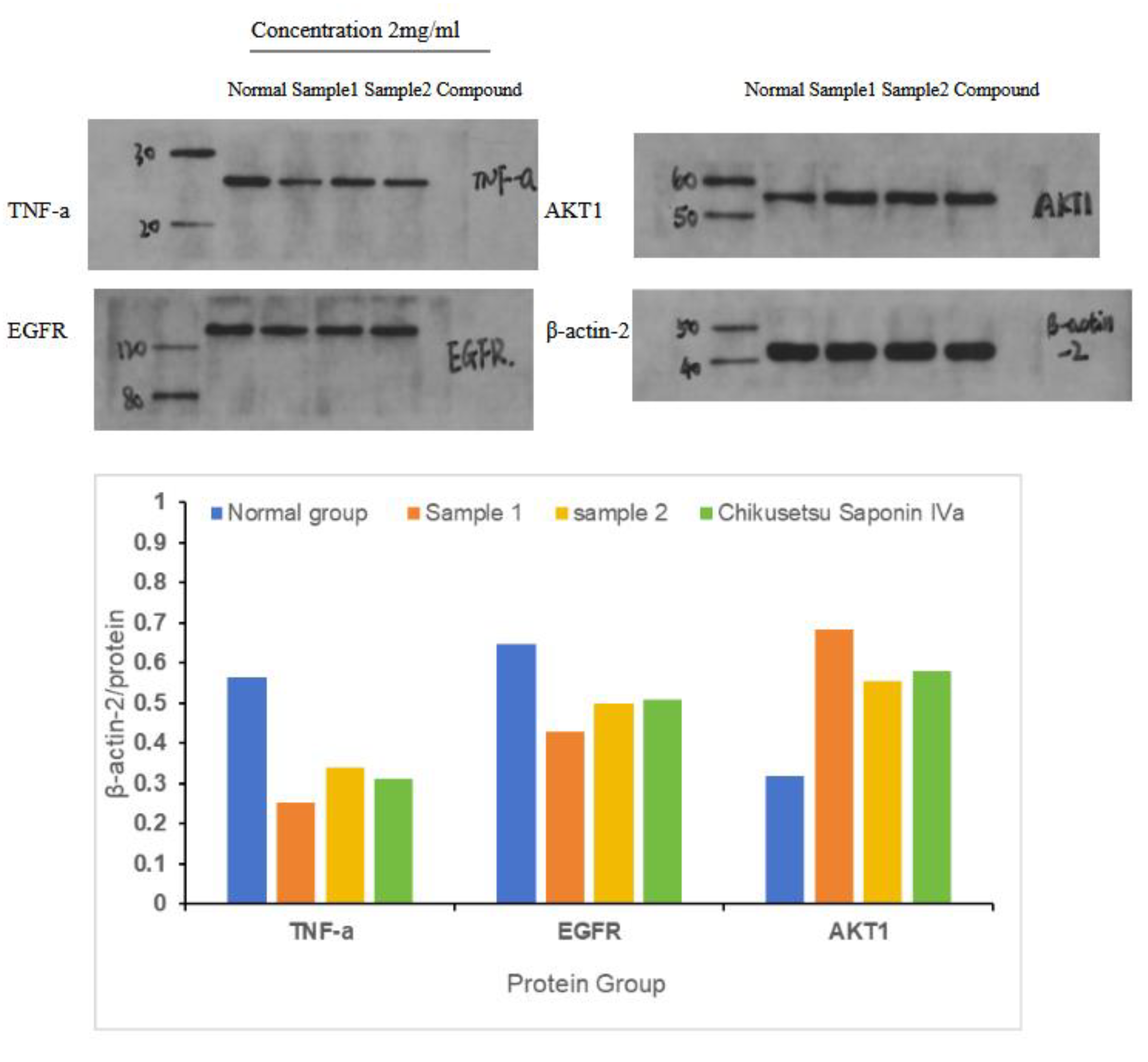

2.9. Western Blot Results Analysis

3. Discussion

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Medicinal Materials, Chemicals

4.2. Collection of Main Active Compounds and Corresponding Targets

4.3. Collection of Disease-Related Targets

4.4. Protein–Protein Interaction (PPI) Network Analysis

4.5. Gene Ontology Term Enrichment and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes Pathway Enrichment Analysis

4.6. Survival Analysis

4.7. Molecular Docking Analysis

4.8. Molecular Dynamics Simulations and Calculation of Binding Free Energies

4.9. Untargeted Metabolomics

4.10. MTS Cell Inhibition Rate

4.11. Western Blotting

5. Conclusions

Declaration of competing interests

Authors’ contributions

Funding information

Acknowledgments

Abbreviations

| Full name | Abbreviation |

| Gastric cancer | GC |

| Encyclopedia of Traditional Chinese Medicine | ETCM |

| Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes | KEGG |

| Gene Ontology | GO |

| Molecular Dynamics | MD |

| Root-Mean-Square Deviation | RMSD |

| Root Mean Square Fluctuation | RMSF |

| Molecular Mechanics Poisson-Boltzmann Surface Area | MMPBS |

| Fetal Bovine Serum | FBS |

| Enhanced Chemiluminescence | ECL |

| Image-Pro Plus | IPP |

| Dried P. japonicus var. major Group | ZZS-G |

| Fresh P. japonicus var. major Group | ZZS-S |

References

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: A Cancer Journal for Clinicians. 2024, 74, 229–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ajani, J.A.; D’Amico, T.A.; Bentrem, D.J.; Chao, J.; Cooke, D.; Corvera, C.; Das, P.; Enzinger, P.C.; Enzler, T.; Fanta, P.; Farjah, F.; Gerdes, H.; Gibson, M.K.; Hochwald, S.; Hofstetter, W.L.; Ilson, D.H.; Keswani, R.N.; Kim, S.; Kleinberg, L.R.; Klempner, S.J.; Lacy, J.; Ly, Q.P.; Matkowskyj, K.A.; McNamara, M.; Mulcahy, M.F.; Outlaw, D.; Park, H.; Perry, K.A.; Pimiento, J.; Poultsides, G.A.; Reznik, S.; Roses, R.E.; Strong, V.E.; Su, S.; Wang, H.L.; Wiesner, G.; Willett, C.G.; Yakoub, D.; Yoon, H.; McMillian, N.; Pluchino, L.A. Gastric Cancer, Version 2.2022, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. Journal of the National Comprehensive Cancer Network. 2022, 20, 167–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vijayalakshmi, S.; D. -Yoo, S.; D.-Kim, G.; Chelliah, R.; Barathikannan, K.; S.-Aloo, O.; Tyagi, A.; Yan, P.; Shan, L.; Gebre, T.S.; Oh, D.-H. Fermented Perilla frutescens leaves and their untargeted metabolomics by UHPLC-QTOF-MS reveal anticancer and immunomodulatory effects. Food Bioscience. 2023, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wang, R.; Na, Z.; Liang, S.; Wu, F.; Xie, H.; Zhang, X.; Xu, W.; Wang, X. Network Pharmacology Analysis of Liquid-Cultured Armillaria ostoyae Mycelial Metabolites and Their Molecular Mechanism of Action against Gastric Cancer. Molecules. 2024, 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, K.; Cao, W.; He, Z.; Liu, L.; Guo, J.; Dong, L.; Song, J.; Wu, Y.; Zhao, Y. Network medicine analysis for dissecting the therapeutic mechanism of consensus TCM formulae in treating hepatocellular carcinoma with different TCM syndromes. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, D.; Yuan, L.; Ma, X.; Meng, F.; Xu, D.; Jia, S.; Wang, Z.; Li, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Nan, Y. The mechanism of polyphyllin in the treatment of gastric cancer was verified based on network pharmacology and experimental validation. Heliyon. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ji, Y.; Liu, Y.; Hu, J.; Cheng, C.; Xing, J.; Zhu, L.; Shen, H.; Silvestre, S.M. Exploring the Molecular Mechanism of Astragali Radix-Curcumae Rhizoma against Gastric Intraepithelial Neoplasia by Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking. Evidence-Based Complementary and Alternative Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Wei, Y.; Yu, X.; Tang, J.; Yin, L.; Wu, Z.; Zhang, J.; Gao, Y. Analysis of Network Pharmacology and Molecular Docking on Radix Pseudostellariae for Its Active Components on Gastric Cancer. Applied Biochemistry and Biotechnology. 2022, 195, 1968–1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zoi, V.; Galani, V.; Lianos, G.D.; Voulgaris, S.; Kyritsis, A.P.; Alexiou, G.A. The Role of Curcumin in Cancer Treatment. Biomedicines. 2021, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda-Madej, A.; Viscardi, S.; Szewczyk, W.; Topola, E. Natural Alkaloids in Cancer Therapy: Berberine, Sanguinarine and Chelerythrine against Colorectal and Gastric Cancer. International Journal of Molecular Sciences. 2024, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.-W.; Liu, C.-H.; Du, K.-C.; Meng, D.-L. Polyhydroxyl guaianolide terpenoids as potential NF-кB inhibitors induced cytotoxicity in human gastric adenocarcinoma cell line. Bioorganic Chemistry. 2020, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rauf, A.; Wilairatana, P.; Joshi, P.B.; Ahmad, Z.; Olatunde, A.; Hafeez, N.; Hemeg, H.A.; Mubarak, M.S. Revisiting luteolin: An updated review on its anticancer potential. Heliyon. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, X.; Sun, K.; Jin, X.; Wu, X.; Xia, M.; Sun, Y.; Feng, L.; Li, G.; Wan, X.; Chen, C. Review on active components and mechanism of natural product polysaccharides against gastric carcinoma. Heliyon. 2024, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, S.; Yin, J.; Bai, Z.; Zhang, Z. Effects of taxol resistance gene 1 on the cisplatin response in gastric cancer. Oncology Letters. 2018. [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- J. -Liu, Z.; Liu, J.; D.-Wang, X.; Luo, Q.; Liu, Z. Activity tracking isolation of Gelsemium elegans alkaloids and evaluation of their antihuman gastric cancer activity in vivo. Chinese Journal of Analytical Chemistry. 2021, 49, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, S.; Hu, Y.; Chen, J.; Wang, X.; Zhang, C.; Liu, Q.; Cai, G.; Wang, H.; Zheng, J.; Wang, Q.; Zhong, L.; Yang, B.; Zhou, S.; Liu, Y.; Han, F.; Wang, J.; Wang, J. Marine fungus-derived alkaloid inhibits the growth and metastasis of gastric cancer via targeting mTORC1 signaling pathway. Chemico-Biological Interactions. [CrossRef]

- Li, H.Y.; Wang, H.Y.; Na, L.S.; Jin, C.H.; Wang, J.L. Ideal solution ranking based on principal component analysis, orthogonal partial least squares discriminant analysis and weighted approximation-gray Evaluating the quality of bead ginseng from different origins by correlation fusion modeling. Chinese Traditional and Herbal Drugs. 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Dan, L.; Gao, T.; Zhang, Y.; Gong, C.; Liu, C.; Li, Y.; Song, X. Panacis majoris Rhizoma: A Comprehensive Review of Phytochemistry, Pharmacology and Clinical Applications. Records of Natural Products. 2024, 53–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Ji, J.; Zhang, J.; Hou, X.; Fu, X.; Luo, Y.; Mei, Z.; Feng, Z. Anti-inflammatory and osteoprotective effects of Chikusetsusaponin Ⅳa on rheumatoid arthritis via the JAK/STAT signaling pathway. Phytomedicine. 2021, 93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Li, X.; Zhou, L.; Jin, Y. Effects of total saponins from Panacis majoris Rhizoma and its degradation products on myocardial ischemia-reperfusion injury in rats. Biomedicine & Pharmacotherapy. [CrossRef]

- Zuo, T.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, R.; Ni, D.; Yuan, Y.; Zhang, S. Characterization of chikusetsusaponin IV and V induced apoptosis in HepG2 cancer cells. Molecular Biology Reports. 2022, 49, 4247–4255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, L.; Zhou, R.; He, Y.; Meng, M.; Hu, J.; Liu, Y.; Pan, Y.; Tang, Z.; Yue, Z. Total saponins from Rhizoma Panacis Majoris inhibit proliferation, induce cell cycle arrest and apoptosis and influence MAPK signalling pathways on the colorectal cancer cell. Molecular Medicine Reports. 2021, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.-H.; Li, D.-J.; He, H.-B.; Li, X.-M.; Ding, Y.-H.; Zhang, Y.-F.; Xu, H.-Y.; Feng, M.-L.; Xiang, C.-Q.; Zhou, J.-G.; Zhang, J.-H.; Liu, H.-J. Saponins from Rhizoma Panacis Majoris attenuate myocardial ischemia/reperfusion injury via the activation of the Sirt1/Foxo1/Pgc-1α and Nrf2/antioxidant defense pathways in rats, Pharmacognosy Magazine. 2018, 14. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, M.X.; Fang, F.; Yang, Y.; Fan, J.L.; Yuan, P. Protective effect of ginsenoside Rg1 on hypoxic-ischemic brain injury and neuronal apoptosis in young rats. Journal of Xi an Jiaotong University, 7652. [Google Scholar]

- Ai, Z.; Liu, S.; Zhang, J.; Hu, Y.; Tang, P.; Cui, L.; Wang, X.; Zou, H.; Li, X.; Liu, J.; Nan, B.; Wang, Y. Ginseng Glucosyl Oleanolate from Ginsenoside Ro, Exhibited Anti-Liver Cancer Activities via MAPKs and Gut Microbiota In Vitro/Vivo. Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry 2024, 72, 7845–7860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, X.; Zhu, M.; Zhu, Z.; Tang, W.; Zhang, H.; Chen, Y.; Liu, F.; Zhang, Y. Ginsenoside Re inhibits non-small cell lung cancer progression by suppressing macrophage M2 polarization induced by AMPKα1/STING positive feedback loop. Phytotherapy Research. 2024, 38, 5088–5106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mansour, H.S.; El-wahab, H.A.A.A.; Ali, A.M.; Aboul-Fadl, T. Inversion kinetics of some E/Z 3-(benzylidene)-2-oxo-indoline derivatives and their in silico CDK2 docking studies. RSC Advances. 2021, 11, 7839–7850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sargsyan, K.; Grauffel, C.; Lim, C. How Molecular Size Impacts RMSD Applications in Molecular Dynamics Simulations. Journal of Chemical Theory and Computation. 2017, 13, 1518–1524. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, E.; Sun, H.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Liu, H.; Zhang, J.Z.H.; Hou, T. End-Point Binding Free Energy Calculation with MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA: Strategies and Applications in Drug Design. Chemical Reviews. 2019, 119, 9478–9508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, G.; Shukla, R.; Singh, T.R. Identification of small molecules against the NMDAR: an insight from virtual screening, density functional theory, free energy landscape and molecular dynamics simulation-based findings. Network Modeling Analysis in Health Informatics and Bioinformatics. 2022, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wiggins, T.; Kumar, S.; Markar, S.R.; Antonowicz, S.; Hanna, G.B. Tyrosine, Phenylalanine, and Tryptophan in Gastroesophageal Malignancy: A Systematic Review, Cancer Epidemiology. Biomarkers & Prevention. 2015, 24, 32–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, T.; Li, Z. ; X.-Deng, M.; Jiang, K.; Liu, D.; H.-Zhang, H.; Shi, T.; L.-Liu, Y.; H.-Wen, X.; Q.-Li, E.; Wang, Z. Isolation, synthesis and bioactivity evaluation of isoquinoline alkaloids from Corydalis hendersonii Hemsl. against gastric cancer in vitro and in vivo. Bioorganic & Medicinal Chemistry. [CrossRef]

- Mochalski, P.; Leja, M.; Ślefarska-Wolak, D.; Mezmale, L.; Patsko, V.; Ager, C.; Królicka, A.; Mayhew, C.A.; Shani, G.; Haick, H. Identification of Key Volatile Organic Compounds Released by Gastric Tissues as Potential Non-Invasive Biomarkers for Gastric Cancer. Diagnostics, /: 13. https, 2075. [Google Scholar]

- Bednarz-Misa, I.; Fleszar, M.G.; Fortuna, P.; Lewandowski, Ł.; Mierzchała-Pasierb, M.; Diakowska, D.; Krzystek-Korpacka, M. Altered L-Arginine Metabolic Pathways in Gastric Cancer: Potential Therapeutic Targets and Biomarkers. Biomolecules, /: 11. https, 2218. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Liu, C.; Guo, J.; et al. Recent advances in research on non-medicinal parts of Panacis Japonici Rhizoma and Panax japonicus var. major. Chinese Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine. 2025.

- Zhang ZQ, Cao L, Song L, et al. Historical evolution and application prospects of Panax japonicus var. Historical evolution and application prospects of Panax japonicus var. major like medicinal herbs. Yunnan Journal of Traditional Chinese Medicine and Materia Medica. 2012, 33(09), 68–71. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, X.; Inta, A.; Yang, X.; Pandith, H.; Disayathanoowat, T.; Yang, L. An Investigation of the Effect of the Traditional Naxi Herbal Formula Against Liver Cancer Through Network Pharmacology, Molecular Docking, and In Vitro Experiments. Pharmaceuticals. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, S.; Liang, X.; Wang, Z.; Jin, H.; Zou, L.; Yang, J. Potential Mechanism of Tibetan Medicine Liuwei Muxiang Pills against Colorectal Cancer: Network Pharmacology and Bioinformatics Analyses. Pharmaceuticals. 2024, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, D.; Dai, J.; Yuan, Y.; Jiang, H.; Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Tao, L.; Sheng, J.; Tian, Y. Exploration of anti-osteoporotic peptides from Moringa oleifera leaf proteins by network pharmacology, molecular docking, molecular dynamics and cellular assay analyses. Journal of Functional Foods. 2024, 116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siddiqui, A.J.; Elkahoui, S.; Alshammari, A.M.; Patel, M.; Ghoniem, A.E.M.; Abdalla, R.A.H.; Dwivedi-Agnihotri, H.; Badraoui, R.; Adnan, M. Mechanistic Insights into the Anticancer Potential of Asparagus racemosus Willd. Against Triple-Negative Breast Cancer: A Network Pharmacology and Experimental Validation Study. Pharmaceuticals. [CrossRef]

- Yu, F.; Zhao, L.; Chu, S. TCHH as a Novel Prognostic Biomarker for Patients with Gastric Cancer by Bioinformatics Analysis. Clinical and Experimental Gastroenterology. 2024, 17, 61–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Quickelberghe, E.; De Sutter, D.; van Loo, G.; Eyckerman, S.; Gevaert, K. A protein-protein interaction map of the TNF-induced NF-κB signal transduction pathway. Scientific Data. 2018, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, Z.; Xu, S.; Jiang, L.; Tan, Z.; Wang, J. A Systematic Pan-Cancer Analysis of CASP3 as a Potential Target for Immunotherapy. Frontiers in Molecular Biosciences. 2022, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimoi, T.; Hashimoto, J.; Sudo, K.; Shimomura, A.; Noguchi, E.; Shimizu, C.; Yunokawa, M.; Yonemori, K.; Yoshida, H.; Yoshida, M.; Kato, T.; Kinoshita, T.; Fukuda, T.; Fujiwara, Y.; Tamura, K. ; Hotspot mutation profiles of AKT1 in Asian women with breast and endometrial cancers, BMC Cancer, 2021, 21. [CrossRef]

- Kondo, T.; Kikuchi, O.; Yamamoto, Y.; Sunami, T.; Wang, Y.; Fukuyama, K.; Saito, T.; Nakahara, H.; Minamiguchi, S.; Kanai, M.; Sueyoshi, A.; Muto, M. Colorectal cancer harboring EGFR kinase domain duplication response to EGFR tyrosine kinase inhibitors. The Oncologist. 2025, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Wu, Z.; Yuan, L.; Chen, X.; Huang, H.; Cheng, F.; Shen, W. Hesperidin inhibits colon cancer progression by downregulating SLC5A1 to suppress EGFR phosphorylation. Journal of Cancer. 2025, 16, 876–887. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Chen, W.; Li, Q.; Yang, R.; Lin, X.; Han, P.; Huang, X.; Hu, H.; Luo, M.L. AKT1E17K-Interacting lncRNA SVIL-AS1 Promotes AKT1 Oncogenic Functions by Preferentially Blocking AKT1E17K Dephosphorylation. Advanced Science. 2025. [CrossRef]

- National Pharmacopoeia Committee. Pharmacopoeia of the People’s Republic of China (I); China Pharmaceutical Science andTechnology Press: Beijing, China, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, S.; Chen, X.; Cheng, J.; Cai, T.; Wu, X.; Cheng, Z.; Qi, S.; Qi, Z. Calunduloside E inhibits HepG2 cell proliferation and migration via p38/JNK-HMGB1 signalling axis. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences. 2021, 147, 18–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Li, X.; Shi, Y.; Chen, T.; Xu, Z.; Wang, P.; Yu, M.; Chen, W.; Li, B.; Jing, Z.; Jiang, H.; Fu, L.; Gao, W.; Jiang, Y.; Du, X.; Gong, Z.; Zhu, W.; Yang, H.; Xu, H. ETCM v2.0: An update with comprehensive resource and rich annotations for traditional Chinese medicine. Acta Pharmaceutica Sinica B. 2023, 13, 2559–2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gfeller, D.; Grosdidier, A.; Wirth, M.; Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissTargetPrediction: a web server for target prediction of bioactive small molecules. Nucleic Acids Research. [CrossRef]

- Safran, M.; Dalah, I.; Alexander, J.; Rosen, N.; Stein, T.I.; Shmoish, M.; Nativ, N.; Bahir, I.; Doniger, T.; Krug, H.; Sirota-Madi, A.; Olender, T.; Golan, Y.; Stelzer, G.; Harel, A.; Lancet, D. GeneCards Version 3: the human gene integrator. Database. 2010, baq020–baq020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamosh, A. Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man (OMIM), a knowledgebase of human genes and genetic disorders. Nucleic Acids Research. 2004.33, D514–D517. [CrossRef]

- Otasek, D.; Morris, J.H.; Bouças, J.; Pico, A.R.; Demchak, B. Cytoscape Automation: empowering workflow-based network analysis. Genome Biology. 2019, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tambouratzis, T. An artificial neural network based approach for online string matching/filtering of large databases. International Journal of Intelligent Systems. 2010, 25, 365–385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherman, B.T.; Hao, M.; Qiu, J.; Jiao, X.; Baseler, M.W.; Lane, H.C.; Imamichi, T.; Chang, W. DAVID: a web server for functional enrichment analysis and functional annotation of gene lists (2021 update). Nucleic Acids Research. 2022, 50, W216–W221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, Q.; Lv, Q.; Wu, R. Mining expression and prognosis of FOLR1 in ovarian cancer by using Oncomine and Kaplan-Meier plotter Pteridines. 2019, 30, 158–164. 30. [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Fang, X.; Lu, Y.; Wang, S. The PDB bind database: collection of binding affinities for protein-ligand complexes with known three-dimensional structures. J Med Chem, 2977. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Der Spoel, D.; Lindahl, E.; Hess, B.; Groenhof, G.; Mark, A.E.; Berendsen, H.J.C. GROMACS: Fast, flexible, and free. Journal of Computational Chemistry. 2005, 26, 1701–1718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abraham, M.J.; Murtola, T.; Schulz, R.; Páll, S.; Smith, J.C.; Hess, B.; Lindahl, E. GROMACS: High performance molecular simulations through multi-level parallelism from laptops to supercomputers. SoftwareX, -2. [CrossRef]

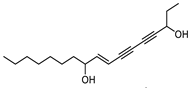

| Compound name | Compound structure | Degree | Betweenness | Closeness |

| Panaxjapyne C |  |

45.0 | 8,980.48 | 0.23108666 |

| Panaxjapyne B |  |

45.0 | 8,888.03 | 0.22919509 |

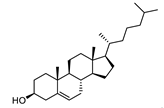

| Cholesterol |  |

22.0 | 2,596.21 | 0.20512821 |

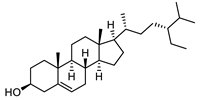

| β-Sitosterol |  |

19.0 | 1,565.01 | 0.20363636 |

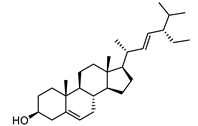

| Stigmasterol |  |

17.0 | 1,001.37 | 0.20071685 |

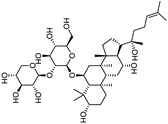

| Notoginsenoside R2 |  |

13.0 | 759.52 | 0.19421965 |

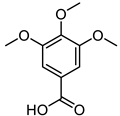

| 3,4,5TrimethoxybenzoicAcid |  |

12.0 | 3,169.00 | 0.19156215 |

| Compound name | Compound structure | Degree | Betweenness | Closeness |

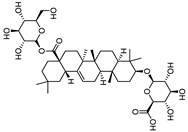

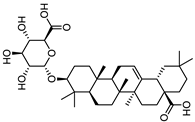

| ChikusetsusaponinIVa |  |

12.0 | 1,601.09 | 0.20664206 |

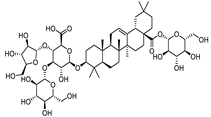

| Stipuleanoside R2 |  |

11.0 | 739.68 | 0.20023838 |

| Calenduloside E |  |

11.0 | 782.38 | 0.20715167 |

| CASP3–Chikusetsu saponin IVa | |

| Van der Waals force | −70.74 ± 1.28 |

| EEL | −54.74 ± 1.96 |

| EGB | 78.59 ± 4.05 |

| ESURF | −9.88 ± 0.09 |

| ΔGGAS | −125.48 ± 2.34 |

| ΔGSOLV | 68.70 ± 4.05 |

| ΔTotal | −56.77 ± 4.68 |

| Protein name | Degree | Protein name | Degree |

| AKT1 | 96 | MAPK14 | 61 |

| TNF | 93 | GSK3B | 59 |

| EGFR | 87 | MAPK1 | 59 |

| CASP3 | 84 | KDR | 58 |

| STAT3 | 84 | EP300 | 58 |

| JUN | 83 | HRAS | 58 |

| ESR1 | 78 | FGF2 | 56 |

| HSP90AA1 | 74 | PARP1 | 54 |

| ERBB2 | 73 | IL2 | 53 |

| MMP9 | 73 | ICAM1 | 48 |

| MAPK3 | 69 | CDK4 | 47 |

| MTOR | 69 | ABL1 | 46 |

| PTGS2 | 67 | AR | 44 |

| PPARG | 67 | ACE | 34 |

| PIK3CA | 62 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).