1. Introduction

The rapid development of large language models (LLMs) has ushered in a new era of machine intelligence, where models trained on vast corpora of text can generate human-like language, translate across domains, and solve a wide range of general-purpose tasks [

1,

2]. While initially conceived as tools for natural language processing, LLMs are now making inroads into the domain of scientific research [

3,

4,

5,

6,

7]. Their ability to process and synthesize information from millions of scientific documents has enabled a new form of knowledge automation—supporting hypothesis generation, experiment design, molecular discovery, and more. In fields such as materials science, physics, chemistry, molecular biology, and climate modeling, LLMs are emerging as both cognitive assistants and collaborators [

1,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12].

Recent studies highlight this trend vividly. For example, Bran et al. demonstrated an autonomous agent powered by an LLM that discovers novel chemical reactions without human intervention [

13,

14]. Szymanski et al. integrated LLM-driven retrosynthesis tools with robotic laboratories to accelerate materials discovery, synthesizing dozens of novel compounds in under three weeks [

15]. In biomedicine, LLMs have been deployed to mine hypotheses from biomedical corpora and recommend plausible molecular targets for therapeutic interventions [

8]. Across disciplines, these systems are increasingly embedded within autonomous scientific platforms, redefining how researchers navigate literature, explore ideas, and orchestrate experiments [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20,

21]. This proliferation of LLMs in natural sciences raises a pivotal question: can these models do more than process language? Can they reason scientifically? Despite their surface-level fluency and impressive performance on general intelligence benchmarks, current LLMs exhibit striking limitations in tasks that require scientific reasoning [

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29]. When asked to infer causal relationships, derive equations, validate physical consistency, or coordinate multiple steps in a hypothesis-testing workflow, LLMs frequently fail in ways that expose a fundamental misunderstanding of the structure and logic of science. They may, for example, confuse correlation with causation, hallucinate physically impossible outcomes, or produce dimensionally inconsistent expressions. These failures are not mere technicalities—they are symptomatic of an architectural misalignment between how current LLMs represent knowledge and how scientific reasoning is actually structured.

To understand this gap, it is useful to distinguish between linguistic and scientific intelligence. Language tasks, such as summarization or translation, depend largely on recognizing patterns of usage and co-occurrence across tokens. Scientific reasoning, by contrast, involves modeling latent structures—causal graphs, systems of equations, spatial constraints, logical implications—and systematically manipulating them to derive testable conclusions. Where language is fluid and probabilistic, science is rigid and rule-bound. Where language is contextual, science demands internal coherence and reproducibility. Current LLMs are, at their core, sophisticated pattern recognizers trained to predict the next token in a sequence. They have no inherent understanding of what a “hypothesis” is, or how it relates to “evidence” or “experimental conditions.” They lack an internal model of physical reality and cannot differentiate between plausible and implausible outcomes based on first principles [

30,

31,

32,

33,

34,

35]. To understand this gap, it is useful to distinguish between linguistic and scientific intelligence. The following comparison outlines their key differences:

Table 1.

Scientific Reasoning vs. Language Prediction Tasks.

Table 1.

Scientific Reasoning vs. Language Prediction Tasks.

| Scientific Reasoning |

General Language Tasks |

| Hypothesis formation (testable, falsifiable) |

Pattern recognition from text corpora |

| Causal inference (cause → effect) |

Co-occurrence statistics (association-based) |

| Dimensional consistency (units, scales) |

Surface-level fluency (grammar, semantics) |

| Constraint satisfaction (physical, logical laws) |

Rarely enforce constraints explicitly |

| Model-based reasoning (e.g. equations, graphs) |

Sequence-based next-token prediction |

| Multi-step abstraction and deduction |

Local, shallow contextual modeling |

In scientific applications, this disconnect often manifests as hallucinations—statements that are grammatically correct but factually or logically incorrect. More critically, LLMs struggle to follow or construct multi-step reasoning chains, a key capability required for tasks such as evaluating the effects of a variable in an experiment or deducing the underlying law from observed data.

This problem is particularly acute in fields that depend heavily on symbolic reasoning and mathematical rigor. In materials science, for example, LLMs may propose synthesis conditions that violate known thermodynamic constraints. In molecular biology, they may confuse the directionality of interactions in signaling pathways [

15,

36,

37,

38,

39]. In theoretical physics, they may generate mathematically nonsensical derivations. Such errors limit the utility of LLMs not because they lack information, but because they lack structure [

40,

41,

42]. The dominant response to these shortcomings has been to scale. Following the “bigger-is-better” paradigm, research groups have trained ever-larger models in the hope that more parameters and more data will lead to deeper understanding. Indeed, scaling laws observed in recent studies suggest that performance continues to improve as models grow large. Yet scientific reasoning has not seen proportional gains. While larger LLMs are better at recalling facts and mimicking styles, they still fail in tasks that require constraint satisfaction, logical deduction, or causal inference. This suggests that the limitations are not simply a matter of insufficient scale, but of inappropriate architecture. If LLMs are to become truly useful collaborators in scientific discovery, they must move beyond linguistic mimicry to engage with the logic and structure of science itself. They must learn not just to generate text, but to understand variables, relationships, and systems. This will require a fundamental shift in how LLMs are built and evaluated. Instead of optimizing purely for token prediction, we must design architectures that reflect the demands of scientific reasoning: modularity, constraint handling, symbolic integration, and physical grounding.

In this Perspective, we propose that the next generation of scientific LLMs must be reimagined as structure-augmented architectures—models that combine the fluency of language with the rigor of reasoning. We begin by analyzing the architectural limitations of current LLMs in

Section 2, then present a set of concrete design principles for structure-augmented models in

Section 3. Finally, we discuss how such systems can be embedded within an open, collaborative ecosystem for scientific research.

2. Current Architectural Limitations of LLMs in Science

Despite their remarkable capabilities in natural language tasks, current LLMs are fundamentally limited in their ability to perform scientific reasoning. These limitations are not incidental or easily solvable by additional data or fine-tuning—they are architectural. To understand why LLMs struggle with science, we must examine the design of these models and the assumptions that underlie their construction. At the core of most LLMs is the transformer architecture, built to optimize the next-token prediction objective over large text corpora. While this setup is highly effective for capturing linguistic patterns and statistical correlations in text, it lacks inductive biases, memory structures, and reasoning mechanisms that are critical for the types of structured thought that science demands. Below, we articulate four key architectural limitations that inhibit current LLMs from functioning as effective scientific collaborators.

2.1. Lack of a World Model or Physical Grounding

LLMs operate entirely within the space of language and token sequences. They have no intrinsic representation of the physical world, nor any direct mechanism for encoding or manipulating spatial, temporal, or causal structures. This is in stark contrast to how scientists reason—by building models of the world that obey physical laws and support extrapolation. For example, an LLM may generate a sequence describing a chemical reaction but has no understanding of reaction kinetics, energy barriers, or mass conservation. It may predict molecular structures that are syntactically valid (e.g., correct SMILES notation) but chemically implausible. Without grounding in physical or spatial reality, LLMs cannot differentiate between possible and impossible outcomes—resulting in plausible but incorrect hallucinations. This lack of grounding leads to dangerous errors in critical applications. In materials science, an LLM might suggest synthesis conditions that violate thermodynamic feasibility. In biology, it may misrepresent causal pathways in regulatory networks. In physics, it might produce equations that look correct but violate dimensional consistency or conservation laws.

2.2. Absence of Structural Inductive Bias

Scientific knowledge is not only linguistic—it is structural. Concepts such as equations, chemical graphs, mechanistic pathways, and experimental workflows have defined relational and modular structures. However, current LLMs treat all text as linear token streams, with no inherent bias toward capturing or leveraging these scientific forms. This creates problems in tasks that require graph-based reasoning (e.g., reaction networks), tensor calculus (e.g., in fluid mechanics), or modular abstraction (e.g., in designing experimental protocols). Without the ability to represent or manipulate these structures, LLMs are unable to engage with the compositional and hierarchical nature of scientific reasoning. For example, in drug discovery, understanding the pharmacokinetics of a molecule requires reasoning about spatial configuration, time-resolved interactions, and multiscale systems. In engineering, designing a reactor requires coordinating multiple interdependent parameters and components. These forms of knowledge cannot be efficiently captured by flat token sequences alone.

2.3. Inability to Enforce Domain-Specific Constraints

Unlike general language generation, scientific reasoning is governed by hard constraints—dimensional analysis, conservation laws, empirical boundaries, symmetries, and formal logic. Current LLMs lack mechanisms to enforce or even recognize such constraints during inference. As a result, they often generate scientifically invalid or self-inconsistent outputs. For example, LLMs have been shown to violate unit consistency in physics equations, confuse molarity and mass in chemistry, or ignore stoichiometric balance in reactions. These are not errors of memorization but of representation—because the models lack architectures that can enforce such constraints structurally, not just statistically. The failure to honor such constraints makes LLMs unreliable in domains where precision and consistency are non-negotiable. This stands in contrast to scientific practice, where the validity of an idea often hinges on its ability to obey such constraints before it can be experimentally tested.

2.4. Flat and Undifferentiated Contextual Reasoning

Transformer-based LLMs process all tokens within a fixed-length context window, treating them with largely uniform attention. While this enables efficient general-purpose processing, it limits the model's ability to differentiate between fundamentally different types of information—e.g., assumptions, background knowledge, observations, hypotheses, and conclusions. Scientific reasoning often involves multiple layers of abstraction: one must distinguish between prior theory, observed evidence, experimental interventions, and desired outcomes. Current LLMs have no mechanism for encoding or reasoning across such layers. This results in reasoning that is shallow, conflated, and often circular. For example, when asked to derive a conclusion from a set of experimental conditions, an LLM may simply reproduce common conclusions associated with similar conditions in its training data—without checking whether those conclusions logically follow from the premises at hand. This undermines the reproducibility, falsifiability, and deductive rigor that are hallmarks of scientific reasoning.

These limitations are not merely inconvenient—they are symptomatic of an architectural design paradigm that was not built for science. The transformer architecture was optimized for linguistic coherence, not epistemic validity. Scientific reasoning, by contrast, demands structure, constraint, abstraction, and verification. Unless we confront these limitations directly, scaling alone will not be sufficient to close the gap. Larger models will produce more fluent text, but not necessarily better science. The path forward requires a fundamental rethinking of how we build LLMs for scientific reasoning—a theme we explore in the next section.

3. Towards Structure-Augmented LLM Architectures

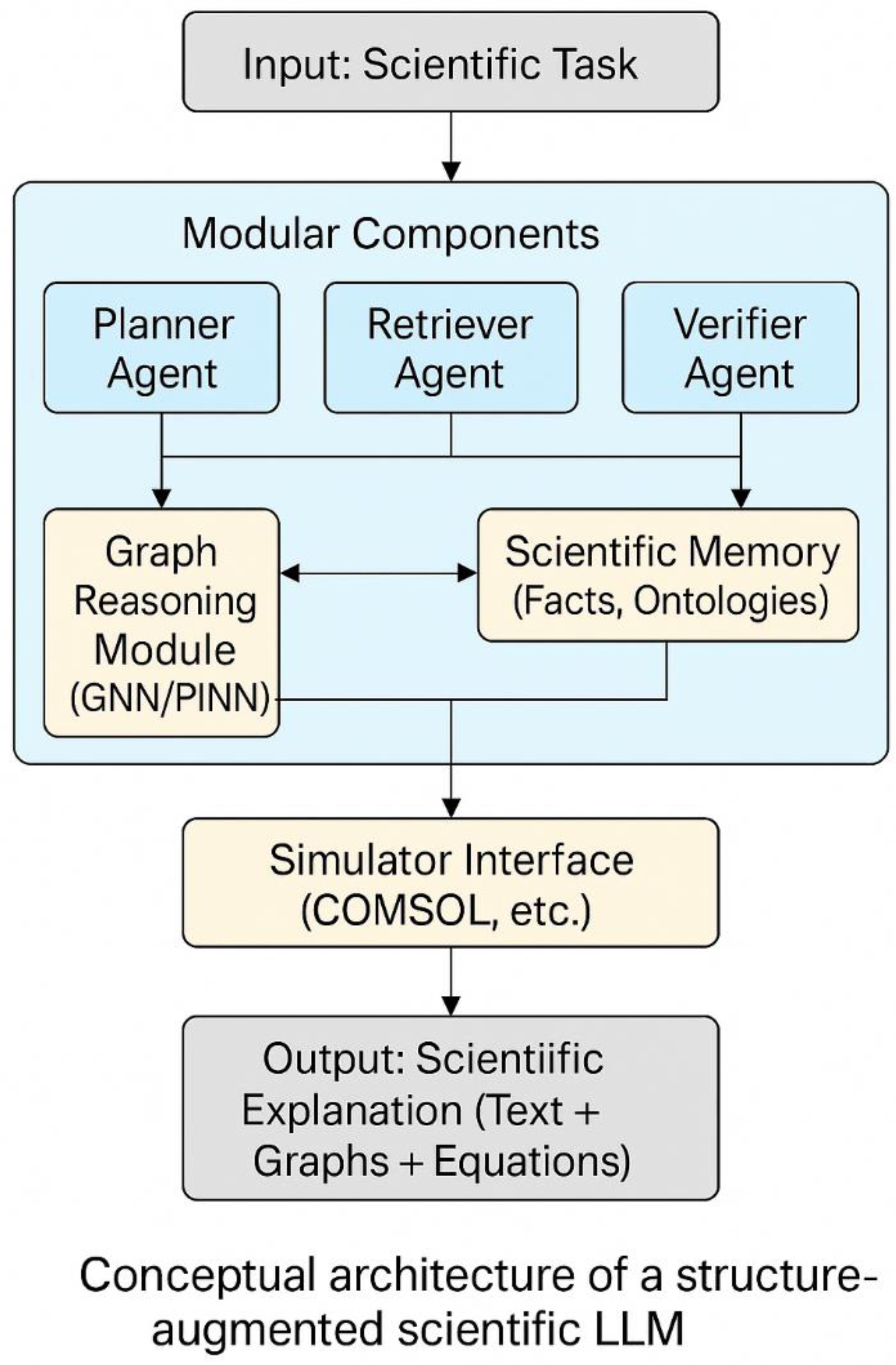

To overcome the architectural limitations discussed above, we argue for a shift in design philosophy—from scaling general-purpose language models to constructing structure-augmented LLMs specifically tailored for scientific reasoning. This next generation of models must integrate domain-specific structure, modular reasoning capabilities, and mechanisms for physical and logical consistency. Such architectures should not only process language but represent relationships, manipulate symbols, and enforce scientific constraints (

Figure 1). We propose two core strategies to enable this transition: (1) embedding graph-based inductive biases through graph neural networks (GNNs), and (2) orchestrating modular LLM agents in a collaborative multi-agent framework. Together, these approaches can transform LLMs from statistical sequence predictors into physically grounded, logically coherent, and experimentally useful scientific engines.

3.1. Graph Neural Networks as Structured Reasoning Modules

Scientific knowledge is often encoded not in flat text, but in graphs: molecular structures, reaction networks, process flows, causal diagrams, and knowledge ontologies. These representations capture relational, compositional, and hierarchical dependencies that are essential for understanding and manipulating scientific systems. Traditional transformer-based LLMs, which operate on token sequences, are poorly suited for these tasks. To bridge this gap, we propose integrating graph neural networks (GNNs) as structural reasoning modules within or alongside LLMs. GNNs excel at capturing local and global topological patterns within graphs, and have demonstrated state-of-the-art performance in chemistry, materials science, and biophysics. For example, molecular GNNs can predict material properties, simulate interactions, and identify functional groups based on atomic connectivity. In scientific LLMs, GNNs can serve as:

Input encoders for converting structured scientific data (e.g. SMILES, experimental workflows, reaction trees) into embeddings.

Reasoning backends that compute transformations, aggregate evidence, or simulate dynamic processes on graphs.

Symbolic scaffolds that enforce chemical valence rules, physical constraints, or logical hierarchies during generation.

The integration can follow multiple pathways:

Loosely coupled: an LLM queries a GNN as an external module during inference (e.g., for molecular validation).

Tightly coupled: LLM and GNN are co-trained, with shared attention layers enabling hybrid token-graph contextualization.

Graph-aware tokenization: replacing standard word tokens with graph nodes and edges, enabling mixed-sequence/graph encoding.

Such hybrid models have already shown early promise in chemical reaction prediction, drug discovery, and material synthesis planning. By embedding graph priors into the reasoning process, LLMs gain the ability to reason over structure, not just sequence, greatly enhancing their scientific utility.

3.2. Multi-Agent LLM Architectures for Modular Scientific Collaboration

Scientific reasoning is rarely a solitary endeavor. It involves multiple roles—a planner who poses the question, an analyst who gathers relevant evidence, a modeler who simulates or derives outcomes, and a verifier who checks consistency. Human scientists naturally distribute these functions across team members or cognitive modules. By analogy, we argue that future scientific LLMs should adopt a multi-agent architecture, in which specialized LLMs act as collaborative scientific agents. This approach draws inspiration from recent advances in LLM swarms, LLM-based operating systems, and autonomous research agents, which demonstrate that different LLMs (or LLM instances) can be assigned distinct cognitive roles and work together through structured dialogues. In the context of science, this enables a division of cognitive labor that is more scalable, interpretable, and resilient than monolithic models.

A proposed structure may involve:

A Planner Agent that formulates research questions, decomposes tasks, and defines constraints.

A Retriever Agent that searches literature, databases, or prior results for relevant knowledge.

A Modeling Agent that simulates systems, solves equations, or builds mechanistic models (possibly via GNNs or PINNs).

A Verifier Agent that checks consistency with domain constraints (e.g. units, logic, empirical laws).

A Communicator Agent that composes coherent natural language outputs or documentation.

These agents can interact through structured protocols, such as chain-of-thought dialogues, role-based turn-taking, or shared memory workspaces. Importantly, each agent can be independently trained or fine-tuned, allowing for modular updates, domain customization, and system-wide interpretability.

In materials research, for example, a planner agent could define a target property (e.g., thermal conductivity > 10 W/mK), a retriever could find known materials with similar characteristics, a modeler could simulate candidates using GNNs or DFT-based approximations, and a verifier could flag inconsistencies or violations of known synthesis constraints. The communicator would then present a ranked list of candidate materials with explanatory rationale. This multi-agent scientific operating system has the potential to transform LLMs from stateless generators into coordinated, goal-driven collaborators, capable of reproducing core aspects of the scientific method.

3.3. Beyond Language: Interfacing with Simulation and Experiment

In addition to reasoning over structure and coordinating agents, structure-augmented LLMs must interface with the physical world—not only by referencing experimental data, but by interacting with simulators, instruments, and experimental protocols. Language alone is insufficient for this task; what’s needed is a multi-modal integration layer that allows LLMs to:

Send and receive data from simulators (e.g., COMSOL, LAMMPS, Gaussian).

Generate scripts or configurations for experimental platforms.

Interpret tabular, image-based, or spectral data.

Adjust hypotheses based on empirical feedback.

Such integration transforms LLMs into cyber-physical systems embedded in scientific workflows. With graph-structured reasoning and multi-agent control, these models can perform closed-loop optimization, adaptive experimentation, or hypothesis refinement—hallmarks of the scientific process. To unlock their full potential in science, LLMs must be fundamentally re-engineered. Structure-augmented LLMs offer a powerful new paradigm, grounded in two key innovations:

Graph neural networks provide the representational backbone to reason over scientific structures, from molecules to experimental workflows.

Multi-agent LLM systems enable role-specialized collaboration, emulating the division of labor and iterative refinement found in real-world science.

Together, these elements can transform LLMs into reasoning machines capable of discovery, verification, and collaboration—moving beyond language to embody the logic of science itself.

4. Outlook: Building Cognitive Infrastructure for the Next Scientific Paradigm

If LLMs are to become true collaborators in science—not just tools for information retrieval or linguistic augmentation—they must be reconceptualized as cognitive infrastructure: intelligent systems that participate meaningfully in the generation, validation, and communication of scientific knowledge. The architecture of these systems must reflect the epistemic structure of science, not just the grammar of human language. But beyond architecture, realizing this vision will require transformation across the broader scientific ecosystem.

4.1. Toward Domain-Specific, Open Scientific Models

One of the major bottlenecks in current LLM development for science is that most state-of-the-art models remain proprietary, opaque, and general-purpose. Their training corpora are undisclosed, their optimization objectives are misaligned with scientific needs, and their internal reasoning processes are difficult to interpret. This hinders scientific reproducibility and innovation. We advocate for the development of open, domain-specialized scientific LLMs—models that are:

Trained on curated scientific corpora including literature, protocols, datasets, and simulations;

Finetuned for specific domains such as materials science, structural biology, physical chemistry, or earth systems science;

Evaluated not only on linguistic benchmarks but on scientific reasoning tasks, including physical law consistency, dimensional correctness, hypothesis generation, and symbolic manipulation.

Community-driven projects such as the OpenBioLLM, MaterialsGPT, and Galactica offer promising prototypes in this direction. What is needed now is sustained funding, institutional coordination, and public infrastructure to support the training, maintenance, and ethical governance of such models across disciplines.

4.2. Toward Multi-Modal Scientific Operating Systems

LLMs must evolve from standalone chatbots to become components of multi-modal scientific operating systems that integrate text, code, simulation, and experimentation. This entails:

Interfacing with electronic lab notebooks (ELNs), simulation environments, robotic synthesis platforms, and digital twins;

Coordinating agents that specialize in literature mining, hypothesis generation, experimental design, and data analysis;

Enabling closed-loop experimentation, where models can plan, execute, and learn from real-world data streams;

Supporting dynamic ontologies that update as scientific understanding evolves.

Such systems will not only accelerate discovery but democratize it—enabling smaller labs, citizen scientists, and under-resourced institutions to leverage powerful AI-driven methodologies with minimal infrastructure.

4.3. Toward Scientific Interpretability and Model Trust

In science, explanation is as important as prediction. An LLM that proposes a new material or mechanism must also be able to articulate why it is plausible, how it compares with prior knowledge, and under what assumptions it holds. Trust in scientific LLMs will depend not only on accuracy, but on transparency, consistency, and interpretability. To support this, future LLMs should include:

Explicit representation of assumptions and constraints;

Traceable reasoning chains (e.g., symbolic proofs, derivation steps);

Graphical or mathematical summaries of hypotheses;

Interfaces for human feedback, correction, and counterfactual testing.

Incorporating explainable AI (XAI) principles into the core of scientific LLM design will be essential, not only for user trust but for integration with peer review, regulatory scrutiny, and publication standards.

4.4. Scientific LLMs as Institutional Collaborators

Perhaps most importantly, the development of scientific LLMs should not be confined to tech companies or academic labs alone. Just as supercomputers and synchrotrons became national infrastructure for computation and experimentation, scientific LLMs should be treated as shared intellectual infrastructure.

This invites a broader conversation about:

Who governs these models and how?

How are biases and errors identified and corrected?

How do we balance open access with responsible deployment?

What new roles emerge for scientists as curators, trainers, and validators of machine-generated hypotheses?

We propose the formation of international LLM science consortia—cross-disciplinary, cross-sector initiatives that oversee the development of models, the curation of benchmarks, and the evaluation of societal impacts. These consortia could help define standards, coordinate data sharing, and promote equitable access to LLM capabilities across the globe.

The next paradigm of science will be defined not only by what we study, but by how we think—and with whom. As LLMs continue to evolve, they offer an opportunity to reshape the cognitive workflows of scientific discovery. But this will only be possible if we move beyond linguistic scaling, and toward architectures that reflect the structure, logic, and ethics of science. Structure-augmented LLMs, powered by graph-based reasoning and modular multi-agent collaboration, represent a critical step in this direction. When embedded within open, transparent, and interdisciplinary ecosystems, they can form the backbone of a new scientific infrastructure—one that is more intelligent, accessible, and collaborative than ever before. In this future, scientists and models will work side-by-side—not in competition, but in co-evolution—toward discoveries neither could achieve alone.