1. Introduction

Recent advances in machine learning and robotics have yielded systems capable of perceptual fluency, linguistic coherence, and reactive behavior [

7,

28,

45]. Yet despite these successes, contemporary artificial intelligence (AI) remains epistemically limited: systems excel at interpolation but falter in unfamiliar contexts, lacking the capacity to form explanatory models or generalize beyond training distributions [

27,

33].

This limitation stems from a foundational assumption—that intelligence can emerge from passive perception alone. Modern AI systems, particularly large language models and deep reinforcement learners, operate as high-capacity pattern extractors. They observe the world, correlate inputs to outputs, and optimize statistical objectives [

25,

38], but they do not ask questions, perform experiments, or revise causal hypotheses in response to environmental surprises [

18,

36].

Yet human understanding—whether at the scale of individual development or civilizational progress—has never arisen from observation alone. For thousands of years, human societies functioned without true explanatory knowledge of the physical world. Only with the emergence of the scientific method—a structured process of hypothesis, intervention, and revision—did we begin to uncover the underlying laws of nature. Similarly, children do not passively absorb facts; they construct causal models by acting, failing, and correcting, iteratively refining their understanding through self-directed epistemic engagement [

9,

17].

In contrast to passive AI, we propose a paradigm rooted in this recursive epistemic process. We call this approach Scientific AI, which defines intelligence not as statistical pattern recognition but as causal discovery. Scientific AI agents are epistemic agents—they interact with their environment to uncover latent structure, reduce uncertainty, and construct transferrable internal models.

This paper develops a formal and architectural framework for Scientific AI, grounded in information theory, causal inference, and recursive self-correction [

6,

15]. We present a proof-of-concept experiment in symbolic physics, demonstrating that even simple agents equipped with epistemic drives and feedback loops can discover novel physical laws [

42]. The result is not merely improved performance, but qualitatively deeper understanding.

Scientific AI represents a path forward not only for robust machine learning, but for the long-standing goal of AGI: to build machines that do not just act effectively, but understand why their actions work.

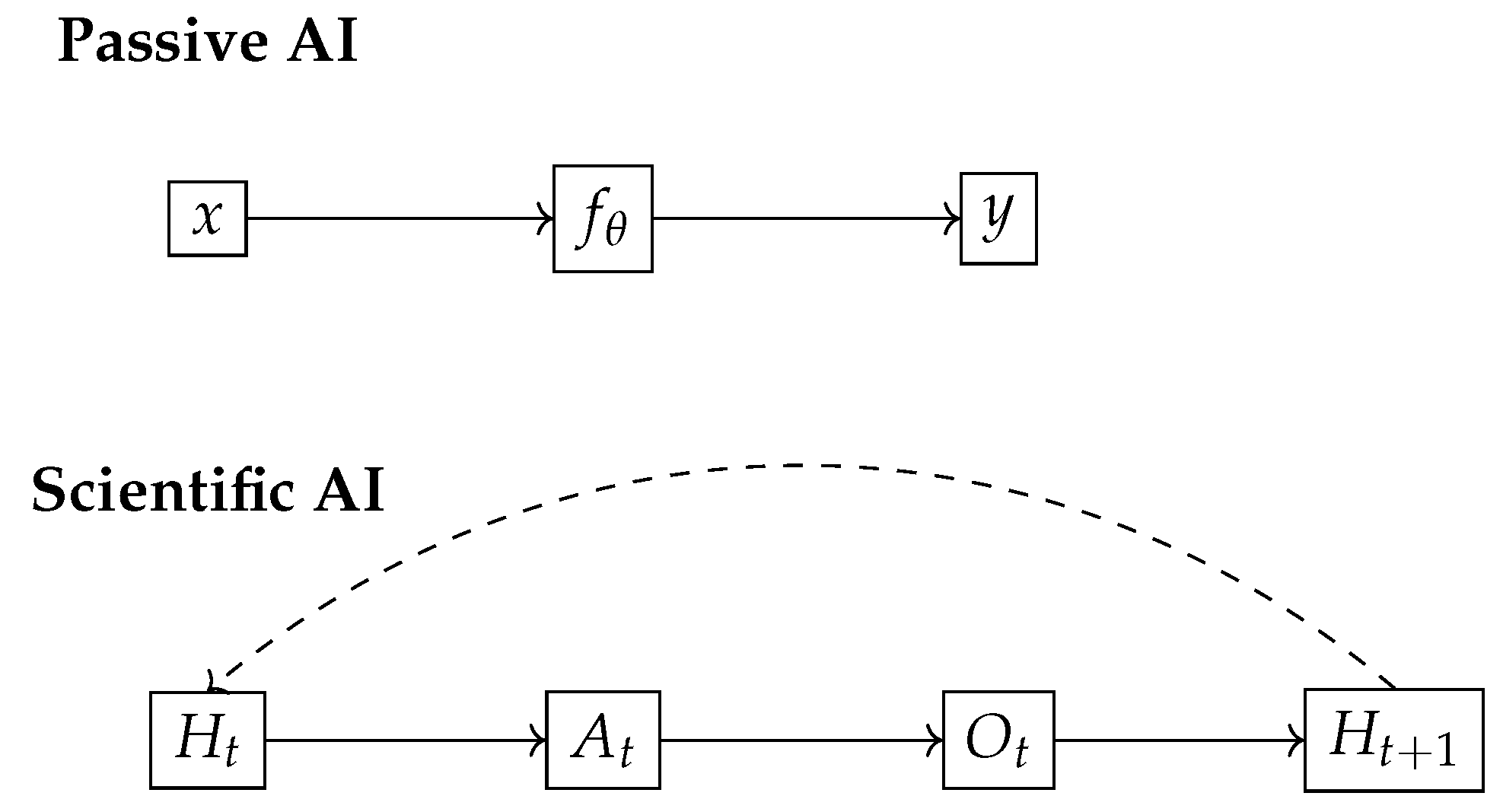

2. From Passive Perception to Active Epistemology

Most contemporary AI systems are trained under the assumption that perception and prediction are sufficient for intelligence [

5,

28]. Deep neural networks, particularly in supervised and self-supervised regimes, learn representations by minimizing predictive loss functions:

where

is a parameterized function approximator mapping input

x to output

y, and

ℓ is a pointwise loss such as cross-entropy or mean squared error. Despite their empirical power, such models are epistemically passive: they do not intervene, ask questions, or revise causal hypotheses [

27,

33].

In contrast, an epistemic agent must be capable of generating and testing hypotheses about the environment [

17,

36]. Let

denote the agent’s current hypothesis or internal world model at time

t, and

an action selected for its expected epistemic utility. The agent then observes an outcome

, evaluates the result, and updates its internal model:

This active loop defines a discovery-oriented epistemology. The agent does not passively encode statistical structure; it engages in structured exploration to falsify beliefs and refine explanations [

15,

18]. The choice of action

is guided not by extrinsic reward maximization, but by expected information gain:

where

denotes the Kullback–Leibler divergence, measuring how much an observation is expected to shift belief [

32].

Figure 1.

Comparison between passive and Scientific AI agents. Passive models learn static input-output mappings; Scientific AI agents update internal hypotheses via interactive epistemic loops.

Figure 1.

Comparison between passive and Scientific AI agents. Passive models learn static input-output mappings; Scientific AI agents update internal hypotheses via interactive epistemic loops.

This shift—from reward maximization to epistemic calibration—transforms the agent’s goal. Intelligence becomes a function of its ability to autonomously reduce uncertainty, revise internal structure, and generalize explanatory models across contexts. We formalize this transition in the next section with a recursive epistemic architecture.

3. Formal Foundations of Scientific AI

3.1. The Epistemic Discovery Loop

Scientific AI centers on a recursive process of hypothesis refinement through interaction. At each timestep t, an agent:

maintains a world model ;

selects an action to test a hypothesis or reduce uncertainty;

receives an observation in response;

updates the model to based on epistemic evaluation.

Formally, the epistemic discovery loop is:

where

is a recursive model update function [

6,

15].

The objective of the agent is not merely task performance, but reduction of epistemic uncertainty over a hypothesis space

. The epistemic gain from an action is quantified by the expected change in belief over

H:

as in active Bayesian inference and information-theoretic planning [

30,

32].

An epistemic agent selects actions that maximize

, forming a closed loop of discovery:

This loop enables continuous refinement of the agent’s explanatory structure, enabling generalization and adaptability across domains [

18,

29].

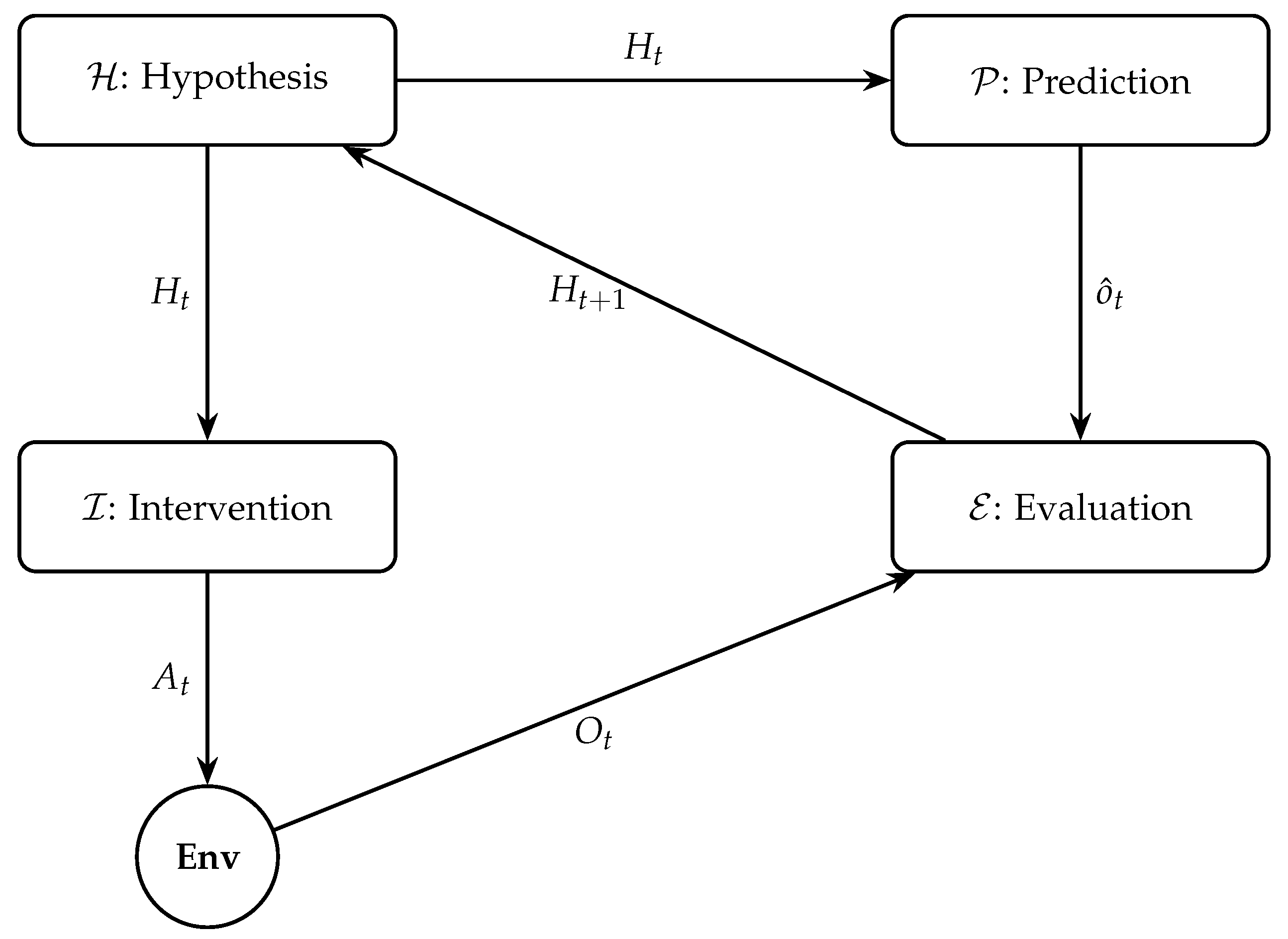

Figure 2.

Epistemic discovery loop in Scientific AI. The agent cycles through hypothesis generation (), action (), observation (), and model revision (). Circular flow emphasizes continuity and recursion in epistemic refinement.

Figure 2.

Epistemic discovery loop in Scientific AI. The agent cycles through hypothesis generation (), action (), observation (), and model revision (). Circular flow emphasizes continuity and recursion in epistemic refinement.

3.2. Quantifying Epistemic Progress

Progress in Scientific AI is measured not by task reward, but by the growth of explanatory capacity. We consider three complementary metrics:

1. Information Gain.

The expected information gain (EIG) from action

A is defined as:

a standard criterion in decision-theoretic experimental design [

24,

30].

2. Predictive Compression.

Let

denote the model’s current internal representation. A compression-based metric evaluates the change in model description length:

where

is a coding length or complexity measure (e.g., MDL) [

19,

47].

3. Prediction Error.

Surprise or mismatch between prediction

and actual observation

provides a basic epistemic signal:

These metrics can be combined in a multi-objective utility for epistemic control:

In Scientific AI, action policies are optimized not for reward acquisition, but for sustained epistemic growth—a foundational distinction from traditional RL and imitation learning [

10,

24].

4. Architectural Blueprint

Scientific AI requires a system architecture that supports recursive discovery, causal modeling, and real-time epistemic feedback [

6,

15]. We propose a modular architecture with three nested calibration loops and four core functional modules, enabling structured knowledge acquisition across spatial and temporal scales [

4,

12].

4.1. Calibration Loops (Evolutionary, Learning, Real-Time)

Scientific AI operates over three interdependent timescales, each characterized by a distinct calibration loop:

1. Evolutionary Calibration ()

encodes priors and inductive biases derived from design-time constraints or meta-learning. These include physical invariants, architectural symmetries, or causal heuristics that bootstrap efficient hypothesis generation [

11,

26].

2. Learning Calibration ()

supports long-term model refinement through episodic memory and belief revision. Given a trajectory of experience

, the agent accumulates structured knowledge and improves future model inference [

23,

48].

3. Real-Time Calibration ()

governs fast, online adaptation. It adjusts internal predictions, attentional weights, or control policies in response to moment-to-moment discrepancies, maintaining short-term stability [

34,

44].

These loops are recursively embedded:

and collectively enable a hierarchy of adaptation that balances flexibility, memory, and structural coherence.

Figure 3.

Three nested calibration loops for epistemic adaptation: evolutionary (), learning (), and real-time (). Each layer supports increasingly flexible and responsive epistemic updates.

Figure 3.

Three nested calibration loops for epistemic adaptation: evolutionary (), learning (), and real-time (). Each layer supports increasingly flexible and responsive epistemic updates.

4.2. Modular Design: Hypothesis, Prediction, Intervention, Evaluation

The epistemic function of Scientific AI is implemented via four interacting modules:

1. Hypothesis Module ()

generates candidate causal models or abstract rules explaining observed phenomena. This may involve symbolic regression, Bayesian networks, or neural program synthesis [

26,

42].

2. Prediction Module ()

simulates expected outcomes based on the current hypothesis:

It provides testable predictions necessary for model falsifiability [

37].

3. Intervention Module ()

selects epistemically valuable actions:

where

U is a composite utility function (e.g., information gain, novelty) [

24,

40].

4. Evaluation Module ()

compares outcomes to predictions and updates the hypothesis:

This may leverage active inference, variational updates, or symbolic model revision [

15,

47].

Together, these modules implement the scientific loop:

with

providing internal simulation for prediction.

This modular architecture generalizes across domains, enabling Scientific AI agents to acquire transferable, causal knowledge via self-directed exploration [

27].

Figure 4.

Modular architecture of Scientific AI. Four core modules—Hypothesis (), Prediction (), Intervention (), and Evaluation ()—interact with an external environment in a closed epistemic loop.

Figure 4.

Modular architecture of Scientific AI. Four core modules—Hypothesis (), Prediction (), Intervention (), and Evaluation ()—interact with an external environment in a closed epistemic loop.

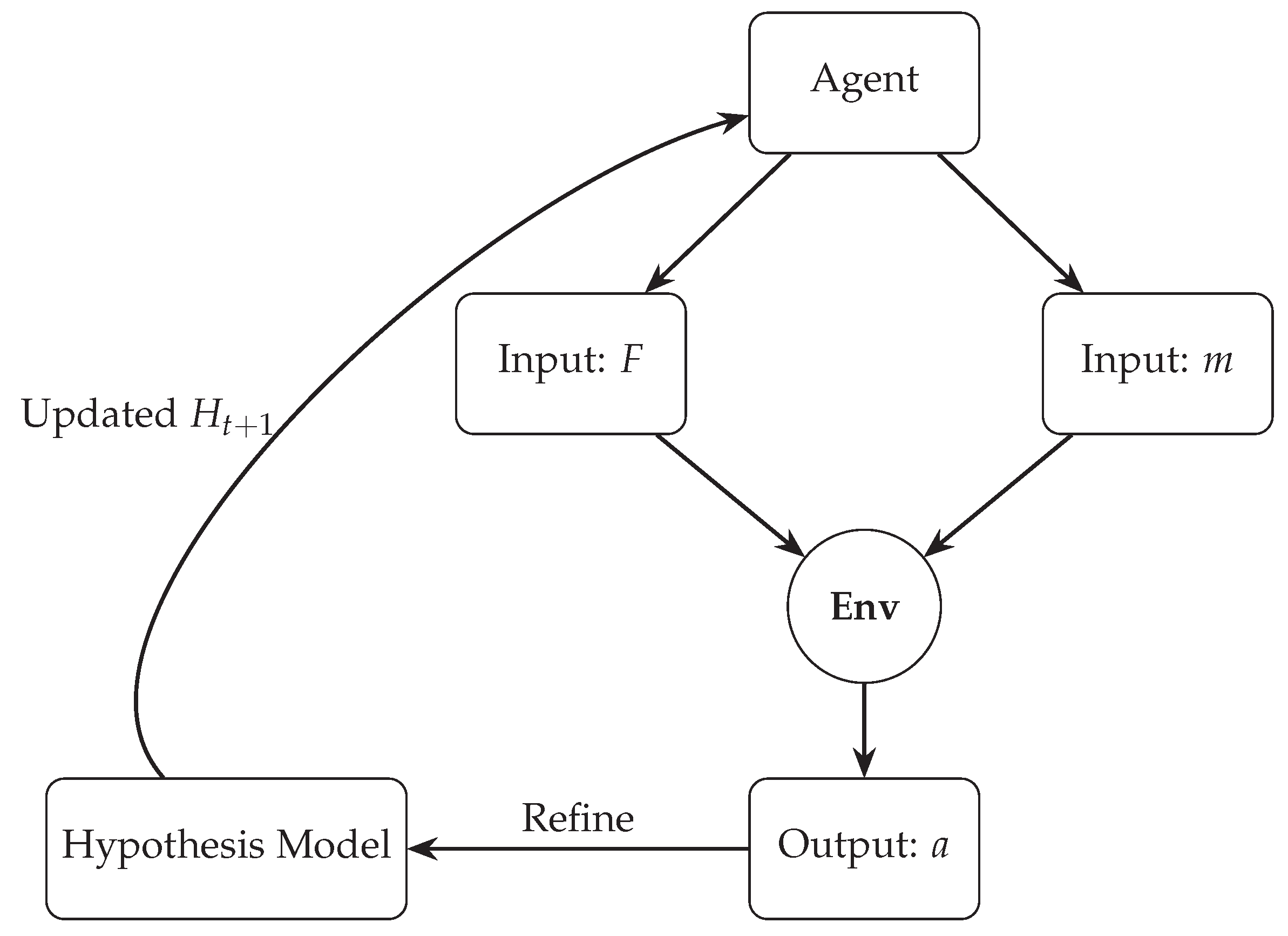

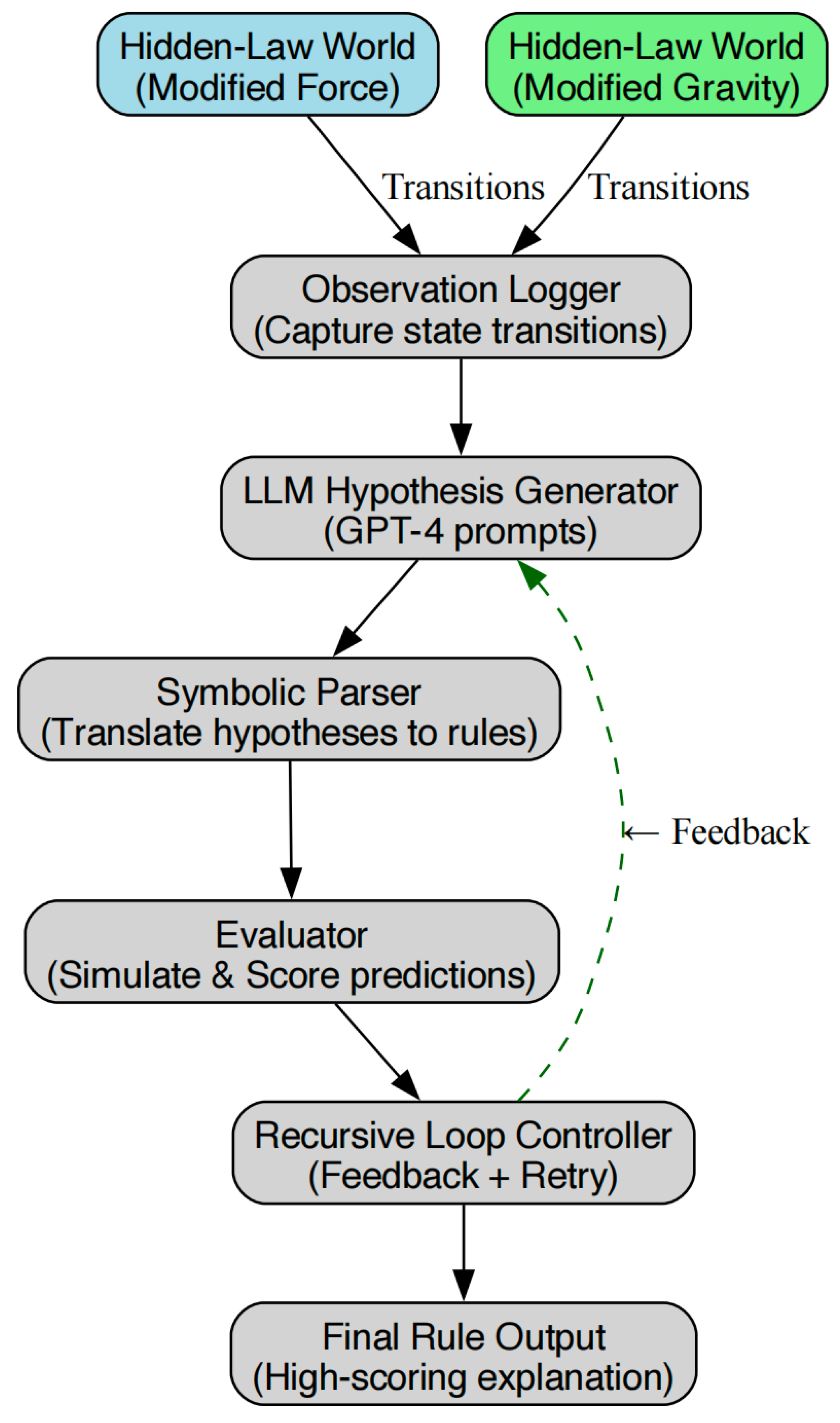

5. Implementation: Proof-of-Concept in Symbolic Physics

5.1. Environment Description

To demonstrate the principles of Scientific AI, we constructed a synthetic symbolic physics environment in which an agent must infer the hidden causal law governing a simple physical system. The environment simulates the relation between force

F, mass

m, and acceleration

a under a modified non-Newtonian law:

At each timestep, the agent selects input values

F and

m, queries the environment, and receives the corresponding

a. The agent’s objective is to discover an explicit symbolic expression that correctly captures the underlying law. Purely observational approaches are ineffective due to the nonlinear and non-intuitive structure of the target relation [

8,

42].

Figure 5.

Symbolic physics environment. The agent selects inputs F and m, queries the environment for output a, and refines its internal hypothesis model in a recursive epistemic loop.

Figure 5.

Symbolic physics environment. The agent selects inputs F and m, queries the environment for output a, and refines its internal hypothesis model in a recursive epistemic loop.

5.2. Recursive Discovery Algorithm

The Scientific AI agent employs a recursive discovery loop to converge on the correct symbolic model. The process is formalized in Algorithm 1 and illustrated in

Figure 6.

|

Algorithm 1 Recursive Symbolic Discovery Loop |

- 1:

Initialize hypothesis pool with simple expressions - 2:

for iteration do

- 3:

Select with highest prior plausibility - 4:

Generate predictions:

- 5:

Compute prediction error:

- 6:

if then

- 7:

return as discovered law - 8:

else

- 9:

Expand hypothesis pool:

- 10:

end if

- 11:

end for |

The

Refine operator mutates symbolic expressions using algebraic transformations—such as exponentiation, ratio formation, or symbolic composition—guided by observed predictive discrepancies [

20,

46]. Crucially, this procedure is epistemically driven: models are not optimized solely for predictive accuracy, but selected for explanatory adequacy and generalization potential [

31].

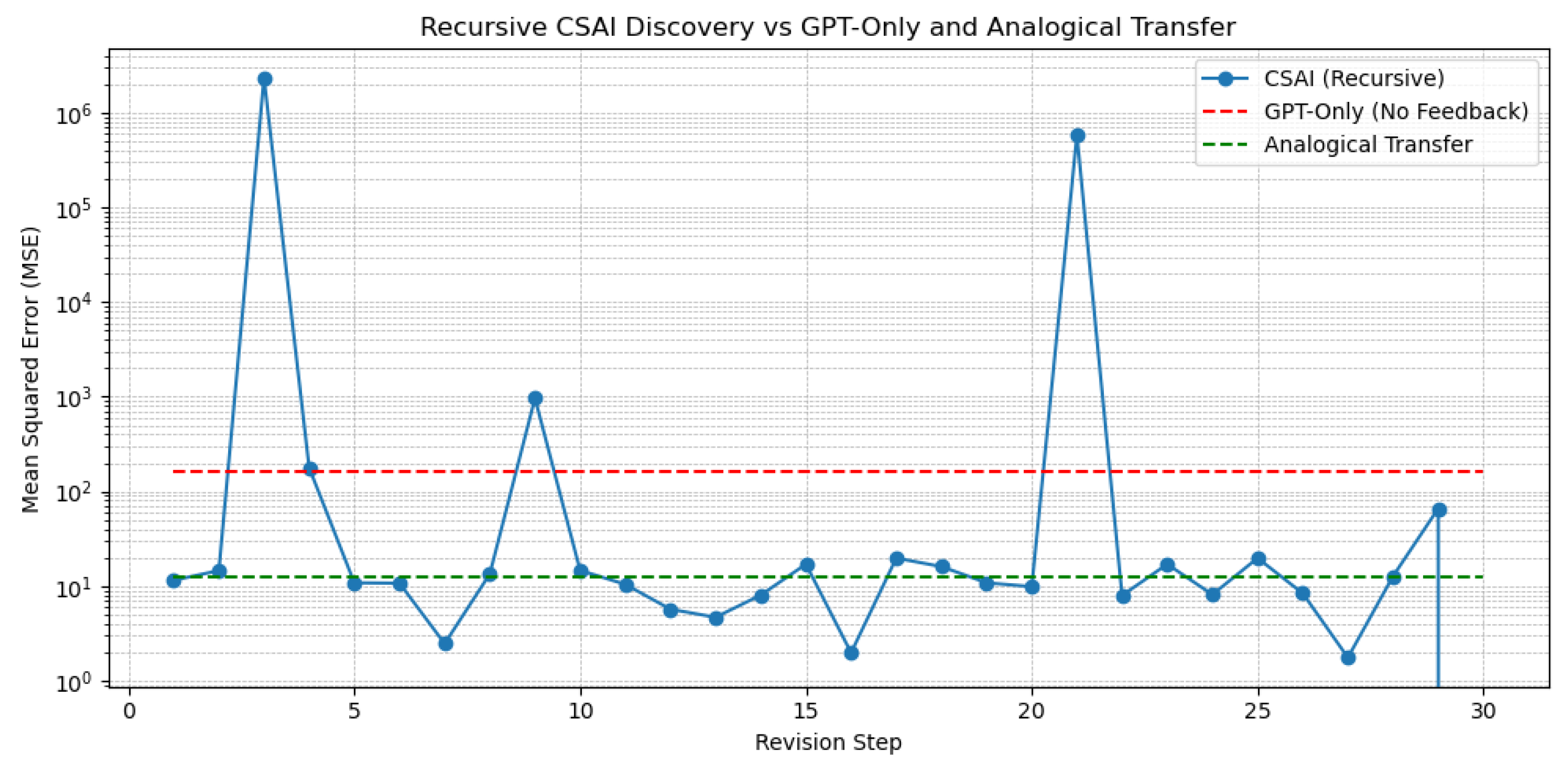

5.3. Comparison to Passive Baselines

We benchmarked the Scientific AI agent against two passive baselines:

GPT-Only Baseline: A large language model trained on scientific text, tasked with predicting the equation from observed triplets

, without feedback [

7].

Analogical Transfer Agent: Initialized with known physical laws (e.g.,

,

) and outputs the best-fit expression without iterative refinement [

27].

Figure 7.

Performance comparison between Scientific AI and passive baselines. Only the Scientific AI agent consistently converges to the correct law , achieving low prediction error within 30 iterations.

Figure 7.

Performance comparison between Scientific AI and passive baselines. Only the Scientific AI agent consistently converges to the correct law , achieving low prediction error within 30 iterations.

Performance was measured by final mean squared error (MSE) and convergence time. Results show that only the recursive Scientific AI agent consistently discovers the correct expression within 30 iterations and achieves near-zero MSE. The GPT-only model often suggests plausible but incorrect formulas (e.g., , ), while the analogical agent lacks the capacity for structural revision.

These findings demonstrate that explanatory discovery requires interactive, epistemically guided loops—validating the central hypothesis of Scientific AI [

18,

36].

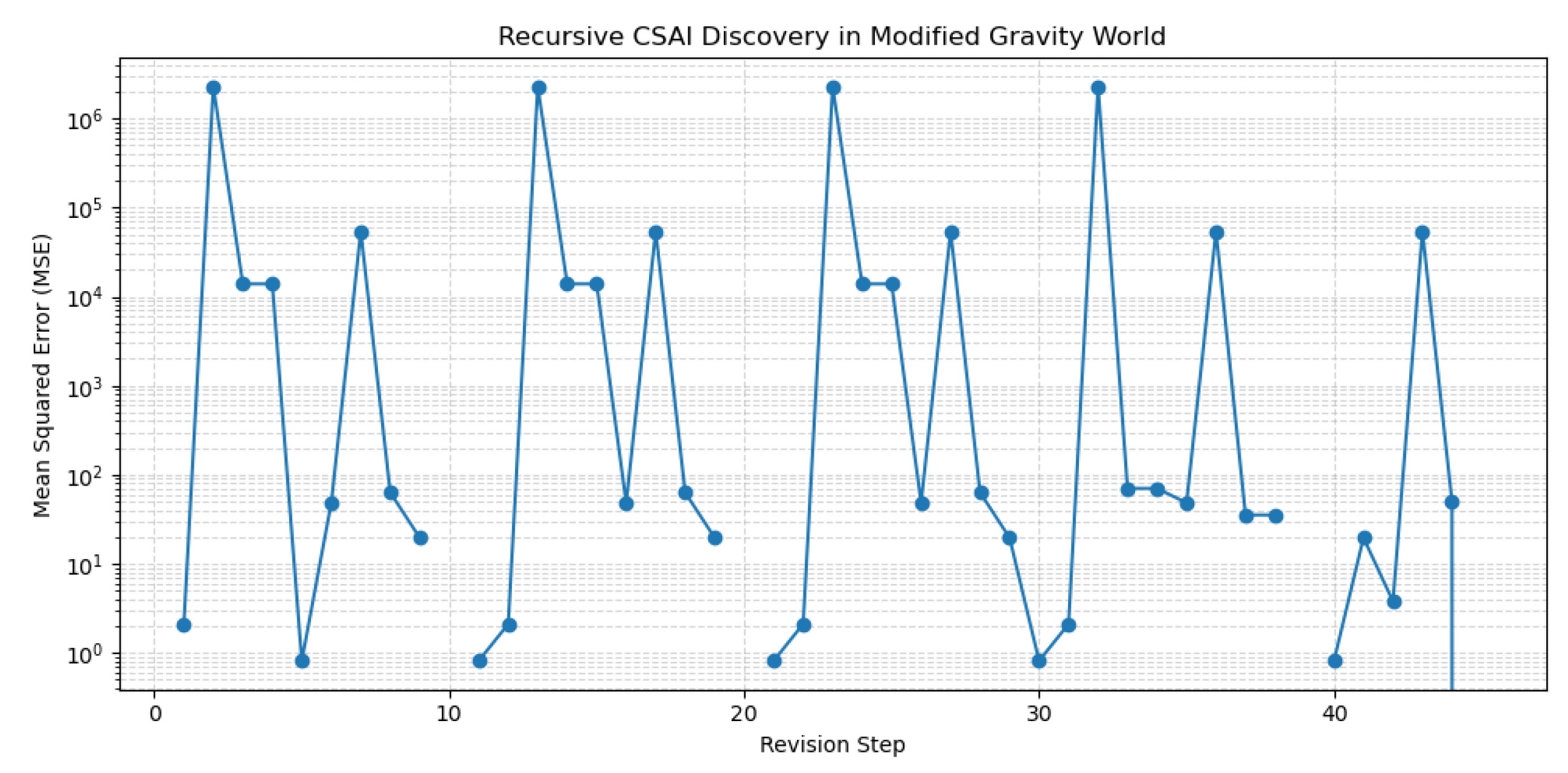

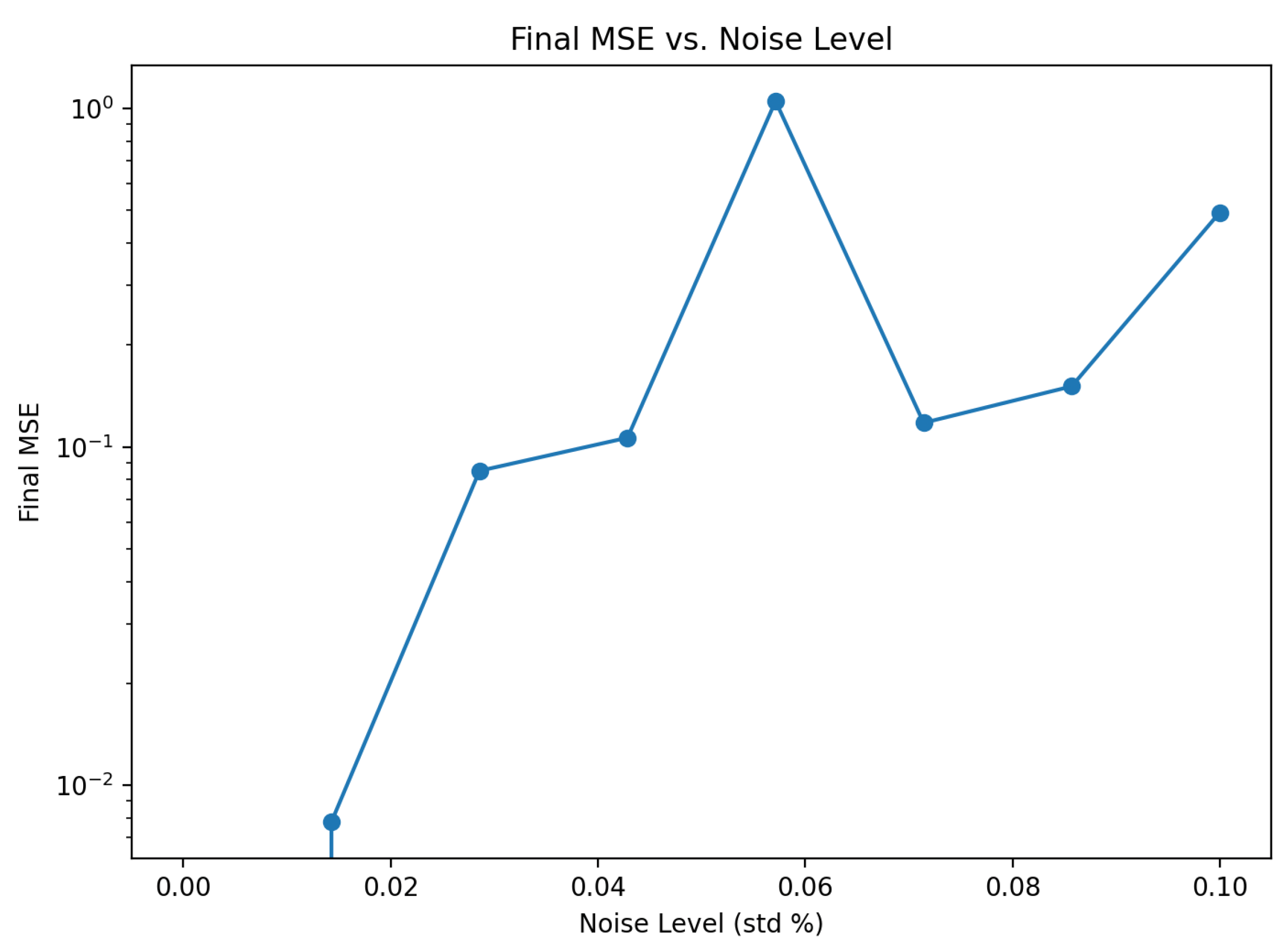

5.4. Generalization to Gravitational Laws

To evaluate Scientific AI’s capacity for conceptual transfer across distinct physical domains, we constructed a second synthetic environment simulating a modified form of gravitational interaction. Classical Newtonian gravity defines the attractive force between two masses

and

at distance

r as:

In our modified domain, the inverse-square dependency was replaced with a non-integer exponent, yielding a hidden law of the form:

This subtle deviation introduces a nonlinear generative structure that cannot be captured by classical forms or standard symbolic heuristics.

We deployed the same recursive discovery loop used in the symbolic physics task, with the Scientific AI agent receiving observations from sampled tuples and attempting to reconstruct the underlying law through iterative hypothesis refinement. Across 45 revision steps, the agent converged precisely on the correct symbolic expression, achieving an MSE of zero across all test data.

In contrast, a GPT-only baseline consistently produced plausible but incorrect formulas such as or , failing to revise its internal model in light of empirical error.

Figure 8.

Convergence of Scientific AI in the gravitational domain. The agent discovers the correct symbolic expression within 45 iterations, achieving zero prediction error.

Figure 8.

Convergence of Scientific AI in the gravitational domain. The agent discovers the correct symbolic expression within 45 iterations, achieving zero prediction error.

Figure 9.

GPT-only baseline performance in the gravitational setting. The model outputs syntactically valid but incorrect expressions, failing to converge on the true exponent or causal law.

Figure 9.

GPT-only baseline performance in the gravitational setting. The model outputs syntactically valid but incorrect expressions, failing to converge on the true exponent or causal law.

Implication:

These findings demonstrate that Scientific AI can infer nontrivial, nonlinear causal structures in domains beyond basic mechanics. Crucially, this generalization emerges not from parameter fine-tuning or task-specific training, but from the architecture’s epistemic loop: its ability to generate symbolic hypotheses, simulate predictions, and recursively update its model based on explanatory failure. This supports the core thesis that Scientific AI enables domain-general causal reconstruction through discovery-oriented computation.

6. Discussion

The Scientific AI framework introduced in this paper has significant implications for the future of artificial general intelligence (AGI), safety-oriented design, and cognitive grounding. Unlike passive AI systems that optimize performance on fixed benchmarks [

7,

28], Scientific AI emphasizes autonomous understanding through recursive model construction and revision [

15,

36]. This approach not only redefines how we build intelligent systems, but also how we assess and align them [

1].

6.1. Toward Artificial General Intelligence

The core premise of AGI is generalization: the ability to reason, adapt, and solve problems across diverse domains [

11]. Scientific AI fulfills this requirement not by scaling data or model size, but by instantiating the epistemic mechanisms through which humans generalize—hypothesis formation, counterfactual simulation, and causal inference [

17,

27]. By embedding these capabilities, Scientific AI provides a domain-independent architecture for acquiring and refining structural knowledge.

Furthermore, the calibration loops and modular design enable continual learning and robust adaptation [

23,

48]. Rather than training anew for each task, a Scientific AI agent reuses and restructures prior models, supporting transfer and abstraction. This process mirrors human cognitive development, where explanation—not repetition—drives learning [

9].

6.2. Epistemic Safety and Interpretability

A major challenge in AI safety is ensuring that systems behave predictably in novel or high-stakes environments [

16]. Passive learners often generalize poorly outside training distributions, creating risks of misalignment or reward hacking [

1]. Scientific AI mitigates this through explicit model revision and transparent epistemic tracking [

10].

Because Scientific AI agents represent beliefs, track uncertainty, and evaluate model error explicitly, their behavior is more interpretable and corrigible [

31,

33]. Designers can inspect hypotheses, observe interventions, and monitor reasoning steps—providing a substrate for safer alignment and oversight.

Additionally, the drive for epistemic gain—rather than reward maximization—reduces perverse incentives. Agents are less likely to exploit loopholes and more likely to seek coherent, generalizable models of the world [

13,

24].

6.3. Grounding Symbols Through Interaction

The symbol grounding problem—the challenge of connecting abstract representations to sensorimotor reality—remains an open issue in cognitive science and AI [

22]. Scientific AI addresses this by requiring agents to discover the operational meaning of symbols through experiment [

18,

42].

Rather than receiving predefined concepts (e.g.,

mass,

force), agents infer these constructs by probing how environmental variables co-vary and affect outcomes. This leads to embodied semantic grounding: concepts acquire meaning not through labels, but through use [

2].

This interaction-driven grounding distinguishes Scientific AI from purely symbolic or purely neural systems. It integrates the strengths of both: the structural clarity of formal models with the empirical grounding of embodied agents [

4,

26].

In summary, Scientific AI reorients intelligence around discovery. It offers a theoretically principled and practically implementable approach to building agents that do not merely perform, but understand. The next sections review related work and outline future directions for scaling this paradigm.

7. Related Work

Scientific AI is situated at the intersection of several key traditions in artificial intelligence and cognitive science. This section compares our approach with related paradigms in active learning, meta-reinforcement learning, and theory-of-mind AI, highlighting both overlaps and distinguishing features.

7.1. Active Learning and Curiosity-Driven Exploration

Active learning strategies prioritize data samples or interactions that are expected to improve model performance [

43]. Techniques such as uncertainty sampling and information gain maximization have been widely used in supervised settings and robotics. Curiosity-driven agents extend this by using intrinsic motivation signals—such as prediction error or novelty—to guide exploration [

35,

41].

While Scientific AI builds on these foundations, it departs in key ways. First, the goal is not merely to improve performance on predefined tasks, but to build explanatory models. Second, our architecture formalizes a recursive discovery loop, explicitly representing and revising causal hypotheses. Finally, Scientific AI evaluates epistemic progress across multiple metrics—not just reward-free exploration, but belief refinement and structural generalization.

7.2. Meta-Reinforcement Learning and Model-Based RL

Meta-reinforcement learning (meta-RL) enables agents to adapt quickly to new tasks by learning how to learn [

14,

48]. Model-based RL further equips agents with internal world models to simulate future outcomes [

21]. Both approaches support generalization and sample efficiency.

Scientific AI inherits these benefits but reorients the objective. Rather than optimizing reward across tasks, we define intelligence as the ability to iteratively construct and test causal theories. This shift aligns with cognitive science views of human reasoning, where knowledge acquisition is epistemically structured, not merely utility-driven [

18,

27].

7.3. Theory of Mind and Epistemic Planning

Recent work on theory-of-mind AI focuses on enabling agents to model the beliefs and goals of others. This often involves nested belief representations and counterfactual inference [

3,

39].

Scientific AI shares this epistemic emphasis but applies it more generally—not just to social cognition, but to the physical and abstract domains. Our agents reason not about other minds per se, but about unknown causal structure in their environment. Nonetheless, the architectural overlap suggests opportunities for convergence: future Scientific AI agents could incorporate theory-of-mind reasoning to explain both physical and social phenomena.

7.4. Symbolic Regression and Scientific Discovery Systems

There is a long tradition of using symbolic regression and program synthesis to automate scientific discovery [

8,

42]. These systems often search equation spaces using heuristics or genetic programming.

Scientific AI extends this tradition by embedding symbolic discovery within a closed epistemic loop. Rather than optimizing expression fit alone, our agents generate, test, and revise models based on interaction and feedback. This dynamic structure allows for deeper integration with sensorimotor grounding and learning-based adaptation.

In summary, while Scientific AI draws from diverse fields, it introduces a distinctive epistemic architecture aimed at unifying exploration, reasoning, and generalization through structured discovery.

8. Conclusions

This paper proposed Scientific AI as a foundational rethinking of artificial intelligence—replacing passive pattern extraction with active epistemic discovery [

18,

36]. We presented a formal framework and architectural blueprint for building agents that generate, test, and refine causal hypotheses through recursive interaction with the environment.

Unlike traditional approaches focused on prediction or reward maximization [

7,

28], Scientific AI centers intelligence on explanation. We operationalized this through multi-timescale calibration loops, modular epistemic components, and quantifiable measures of epistemic progress [

15,

31]. Our proof-of-concept experiment in symbolic physics demonstrated that such agents can autonomously discover non-trivial physical laws, outperforming passive baselines [

8,

42].

Scientific AI offers a pathway toward AGI that is grounded in the dynamics of understanding. By embedding hypothesis-driven reasoning and interactive feedback at the core of learning [

23,

27], we align machine intelligence more closely with the cognitive processes underlying human discovery [

17].

Future work will expand this framework to multi-agent scientific reasoning, theory-of-mind modeling [

39], and scaling to real-world domains such as biology, economics, and ethics. We also envision integrating neural-symbolic architectures and large language models into the epistemic loop—enhancing generalization while maintaining structural clarity [

4,

33].

Ultimately, the goal is not merely to build systems that act intelligently, but that know why they do so—and can explain it.

Author Contributions

Bin Li is the sole author

Funding

This research received no external funding

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

References

- Amodei, D. , et al. (2016). Concrete problems in AI safety. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1606.06565.

- Anderson, M. L. (2003). Embodied cognition: A field guide. Artificial Intelligence, 149(1), 91–130.

- Baker, C. L., Jara-Ettinger, J., Saxe, R., & Tenenbaum, J. B. Rational quantitative attribution of beliefs, desires and percepts in human mentalizing. Nature Human Behaviour 2017, 1(4), 0064.

- Bengio, Y. (2017). The consciousness prior. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1709.08568.

- Bengio, Y., Courville, A., & Vincent, P. (2013). Representation learning: A review and new perspectives. IEEE Transactions on Pattern Analysis and Machine Intelligence, 35(8), 1798–1828.

- Bottou, L. From machine learning to machine reasoning. Machine Learning 2012, 94, 133–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Brown, T. B. Language models are few-shot learners. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems 2020, 33, 1877–1901. [Google Scholar]

- Brunton, S. L., Proctor, J. L., & Kutz, J. N. (2016). Discovering governing equations from data by sparse identification of nonlinear dynamical systems. PNAS 2016, 113(15), 3932–3937.

- Carey, S. (2009). The Origin of Concepts. Oxford University Press.

- Chater, N., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Yuille, A. (2009). Probabilistic models of cognition: Conceptual foundations. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 13(7), 287–293.

- Chollet, F. (2019). On the measure of intelligence. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1911.01547.

- Clark, A. (2016). Surfing Uncertainty: Prediction, Action, and the Embodied Mind. Oxford University Press.

- Everitt, T. , et al. (2021). Reward tampering problems and solutions in reinforcement learning: A causal influence diagram perspective. Artificial Intelligence 2021, 287, 103368. [Google Scholar]

- Finn, C. , Abbeel, P., & Levine, S. (2017). Model-agnostic meta-learning for fast adaptation of deep networks. ICML.

- Friston, K. (2010). The free-energy principle: a unified brain theory? Nature Reviews Neuroscience, 11(2), 127–138.

- Gabriel, I. (2020). Artificial intelligence, values, and alignment. Minds and Machines, 30(3), 411–437.

- Gopnik, A. (2000). The scientist as child. Philosophy of Science, 67(S3), S200–S209.

- Gopnik, A., Glymour, C., Sobel, D. M., Schulz, L. E., Kushnir, T., & Danks, D. (2004). A theory of causal learning in children. Psychological Review, 111(1), 3–32.

- Grünwald, P. D. (2007). The Minimum Description Length Principle. MIT Press.

- Gulwani, S., Polozov, O., & Singh, R. (2017). Program synthesis. Foundations and Trends in Programming Languages, 4(1–2), 1–119.

- Ha, D. , & Schmidhuber, J. (2018). World models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1803.10122.

- Harnad, S. (1990). The symbol grounding problem. Physica D, 42(1–3), 335–346.

- Hassabis, D., Kumaran, D., Summerfield, C., & Botvinick, M. (2017). Neuroscience-inspired artificial intelligence. Neuron, 95(2), 245–258.

- Houthooft, R. , et al. (2016). VIME: Variational information maximizing exploration. NeurIPS.

- Krizhevsky, A., Sutskever, I., & Hinton, G. E. (2012). ImageNet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. NeurIPS, 25.

- Lake, B. M., Salakhutdinov, R., & Tenenbaum, J. B. (2015). Human-level concept learning through probabilistic program induction. Science, 350(6266), 1332–1338.

- Lake, B. M., Ullman, T. D., Tenenbaum, J. B., & Gershman, S. J. (2017). Building machines that learn and think like people. Behavioral and Brain Sciences, 40.

- LeCun, Y., Bengio, Y., & Hinton, G. (2015). Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521(7553), 436–444.

- Legaspi, R., & Toyoizumi, T. (2021). Active inference under incomplete and mixed representations. Neural Computation 2021, 33(4), 845–879.

- Lindley, D. V. (1956). On a measure of the information provided by an experiment. Annals of Mathematical Statistics, 27(4), 986–1005.

- Lipton, Z. C. (2018). The mythos of model interpretability. Communications of the ACM, 61(10), 36–43.

- MacKay, D. J. C. (2003). Information Theory, Inference and Learning Algorithms. Cambridge University Press.

- Marcus, G. (2018). Deep learning: A critical appraisal. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1801.00631.

- Oord, A. V. D. , Li, Y., & Vinyals, O. (2018). Representation learning with contrastive predictive coding. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1807.03748.

- Pathak, D. , Agrawal, P., Efros, A. A., & Darrell, T. (2017). Curiosity-driven exploration by self-supervised prediction. CVPR Workshops.

- Pearl, J. (2009). Causality: Models, Reasoning and Inference (2nd ed.). Cambridge University Press.

- Popper, K. (2005). The Logic of Scientific Discovery (Original work published 1934). Routledge.

- Radford, A. , et al. (2021). Learning transferable visual models from natural language supervision. ICML.

- Rabinowitz, N. C. , et al. (2018). Machine theory of mind. ICML.

- Schaul, T. , et al. (2015). Universal value function approximators. ICML.

- Schmidhuber, J. (2006). Developmental robotics and artificial curiosity. Connection Science.

- Schmidt, M. , & Lipson, H. (2009). Distilling free-form natural laws from experimental data. Science.

- Settles, B. (2009). Active learning literature survey. University of Wisconsin-Madison, Computer Sciences Technical Report.

- Shen, S. , et al. (2023). Foundation models for decision making. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2301.04104.

- Silver, D., et al. (2021). Reward is enough. Artificial Intelligence 2021, 299, 103535. [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, V. , et al. (2023). Symbolic regression with large language models. arXiv preprint, arXiv:2302.01720.

- Tishby, N. , Pereira, F. C., & Bialek, W. (2000). The information bottleneck method. arXiv preprint, arXiv:physics/0004057.

- Wang, J. X. , et al. (2016). Learning to reinforcement learn. arXiv preprint, arXiv:1611.05763.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).