1. Introduction

Marvin Minsky’s Society of Mind [

1] proposed an arresting architectural metaphor: a mind not as cathedral but as city—no singular nave of enlightenment, only neighbor-hoods of small, workmanlike agents whose traffic and trade give rise to thought. In this view, intelligence is civic, distributed, a choreography of limited parts that, in aggregate, perform something like understanding. The brilliance of the metaphor outpaced the machinery of its era. Hand-tooled rules stood in for memory; brittle modules posed as judgment. The edifice persuaded as theory but creaked in practice, a scaffolding without the reinforced beams of learning or long-term coherence.

The landscape has shifted. Deep networks now ingest oceans of data, yet much of their power is opaque—black-box virtuosity without transparent reasons, fluency with-out common sense. Critics and champions alike converge on a common worry [

2,

3,

4]. Large language models imitate the music of discourse while missing its meaning; they lack persistent memory, embodied world models, and the disciplined habit of explanation. Scale has delivered spectacle, not mindfulness [

5]. If Minsky demystified the mind by distributing it, today’s problem is the inverse: we have concentrated capability without distributing responsibility, reason, or recall.

This paper answers that problem with a reframing: from a society within a mind to a Society of Minds—plural intelligences, human and artificial, bound by norms of dialogue, shared memory, and the obligation to give reasons. The promise is not a bigger model but a better polity: systems that argue, revise, and co-construct meaning; machines that are accountable to each other before they are persuasive to us. To orient the argument, we set out the paper’s goals:

Position Society of Minds as a path to AGI: replace monolithic mastery with dialogical competence—capability that emerges from coordinated, critique-ready minds.

Advance a Mind–Brain–Body triad for the digital world: Body as machine substrate and tools; Brain as pattern-learning AI; Mind as higher-order, ethical and explanatory oversight—the locus of reasoning, restraint, and purpose.

Clarify the role of current models: training harvests global knowledge; true reasoning and memory live at the mind layer, where explanations are required and retained.

Center interaction as the driver of augmented intelligence: minds—human and artificial—optimize action by exchanging discernible explanations grounded in extendable, explainable knowledge.

Give the paradigm technical footing: adopt graph-structured memory to anchor shared context; use dialogical mechanisms to test, criticize, and extend knowledge—moving from incremental improvement to a transformative civic model of intelligence.

Overall, our approach represents a paradigm shift, not an incremental tweak. Rather than building ever-bigger black-box models, we propose a new blueprint for AI – one that emphasizes interaction, explanation, and governance among a community of minds. In the following sections, we detail this framework and its significance: first revisiting Minsky’s original concept, then presenting the reimagined Society of Minds and its novel architectural components, and finally discussing the broader implications for AI development.

2. Society of Mind Framework

Marvin Minsky’s Society of Mind theory [

1] remains a foundational idea in AI and cognitive science. Minsky argued that intelligence can emerge from numerous simple parts – a “society” of tiny agents inside one mind. In his view, each agent might be a minimal cognitive skill (a small rule, a heuristic, a feature-detector, etc.), and no single agent is smart on its own. Yet, when organized into the right hierarchies and feedback loops, their collective behavior produces what we recognize as thinking. As Minsky famously noted, “the power of intelligence stems from our vast diversity, not from any single, perfect principle” [

1]. This perspective was a breakthrough in the 1980s: it shifted AI research away from searching for one grand algorithm and toward constructing intelligence via the interaction of many smaller processes.

However, the Society of Mind paradigm was very much a product of its time. Min-sky’s agents were largely conceived as hand-crafted symbolic programs – if-then rules, frames, or other modular routines. While conceptually elegant, such agents proved difficult to scale or adapt. Early attempts to build Society-of-Mind systems ran into coordination problems: without robust learning and memory, a collection of simple agents could just as easily produce chaos as coherence. By the 1990s, the field’s focus had shifted to-ward two other approaches: on one hand, large neural networks that learned patterns in a more monolithic way (trading interpretability for performance) [

5], and on the other hand, dedicated expert systems for narrow tasks [

6]. Minsky’s grand vision remained only partially realized; it lacked the detailed mechanisms to allow many components to learn together and form a truly integrated mind. In summary, the original Society of Mind provided a powerful metaphor – intelligence from interaction – but implementing that metaphor required capabilities (like scalable learning, shared memory, resource optimization, and conflict resolution among agents) that were not yet available in Minsky’s era.

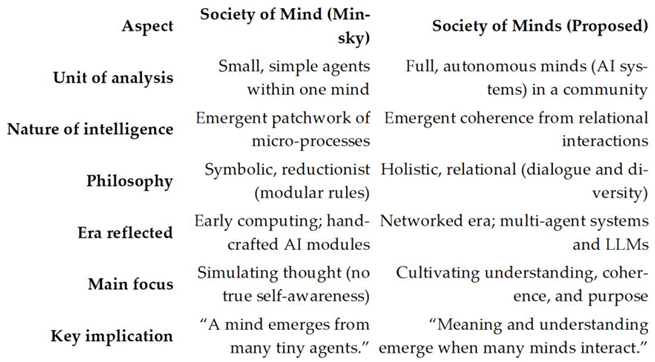

Table 1 provides a high-level comparison of Minsky’s Society of Mind versus our proposed Society of Minds, highlighting how the unit of analysis, nature of intelligence, and overall focus shift in the new paradigm. In Minsky’s view, intelligence is an emergent “patchwork” of many small agents inside one mind, reflecting the symbolic AI era. In the Society of Minds, intelligence is an emergent coherence from many full minds interacting, reflecting a relational and dialogical approach.

3. Society of Minds Paradigm

“A mind is a coherent module with reasoning, memory, and self-regulation, unlike an agent, which may only perform tasks.”

The Society of Minds paradigm extends Minsky’s original metaphor outward, from many agents within a single mind to many minds—human and artificial—interacting within a common ecosystem. Clarify here what “mind” means in this context: a coherent, semantically whole module with memory, reasoning, and explanation capabilities, not just a tool or subroutine.

Recent proposals for multi-agent LLM orchestration—where several specialized LLMs are coordinated to perform tasks—partially echo Minsky’s metaphor. However, these orchestrations typically remain task-oriented pipelines: they divide labor among models but rarely provide enduring memory, epistemic accountability, or built-in governance. Orchestration layers often script collaboration superficially, producing chains of outputs without genuine dialogue, critique, or explanation. As a result, they remain extensions of monolithic LLMs rather than a new paradigm of intelligence.

The Society of Minds introduces dialogical governance as its core innovation. Minds are not only required to act but to explain their reasoning to peers—human or artificial—and to accept critique or revision. This avoids “post-hoc rationalization” by employing cognizing oracles and graph-structured memory to ground explanations in traceable reasoning chains [

7].

Technically, this approach builds on prior paradigms without discarding them. Symbolic reasoning provides transparency, neural networks provide perception and fluency, and agentic controllers provide autonomy. The novelty lies in composition and communication: these diverse modules are knitted together through governance protocols (consensus algorithms, arbitration policies, conflict resolution strategies).

Practical demonstrations illustrate feasibility. In enterprise strategy, multiple AI agents (data analyst, scenario planner, ethics auditor) co-construct recommendations, each ex-plaining its contribution. In medical diagnostics, specialist models (radiology, pathology, ethics) interact with human doctors, producing consensus diagnoses with documented reasoning. These principles are already being tested in video-on-demand and enterprise observability prototypes.

This design acknowledges new challenges: redundancy, potential groupthink, and coordination overhead. Computational cost is real, but historical transitions—from single-core to multi-core, from monoliths to microservices—show that efficiency follows once coordination mechanisms mature.

The concern that the digital genome might be too static or a single point of failure is addressed by noting that the genome is dynamic and evolving, updated by event-driven history and non-Markovian processes [

8] should be understood as a policy-driven, evolving knowledge fabric rather than a fixed repository.

Thus, the Society of Minds paradigm is not just orchestration of modules but cultivation of relational intelligence: knowledge grows through explanation, critique, and revision across interacting minds. This dialogical orientation sets the stage for our discussion of epistemology, safety, and emergent coherence.

3.1. What’s New?

The move toward a Society of Minds entails several novel conceptual shifts and technical innovations. In summary, our approach introduces the following key con-attributions to AI architecture and thought:

Ethics Embedded in Architecture: We advocate moving beyond external “after-the-fact” guardrails and instead baking in ethical reasoning and constraints from the start. Concretely, we propose constructs like Digital Genomes and Cognizing Oracles to encode values and enable self-monitoring within AI minds [

9]. A digital genome is a structured knowledge representation that carries not just facts but also the purpose and context of those facts – essentially encoding a system’s goals and constraints in its knowledge base [

9]. Meanwhile, a cognizing oracle is a mechanism for transparency: it “looks inside” black-box models to extract hu-man-readable explanations or detect doubt. By incorporating these components, an AI mind can explain its reasoning and flag potential errors by itself, enforcing accountability internally. In our Society of Minds, every claim should come with a rationale (via the oracles), and every mind’s knowledge is accompanied by provenance and usage context (via digital genomes). This built-in explainability and value-tagging means ethics is not an afterthought but part of the AI’s core design. (In practice, these ideas draw on recent work by Mikkilineni & colleagues [

9,

10], linking our approach to emerging “mindful AI” prototypes).

Brain–Body–Mind Triad Model: What Is a Computer, and Is the Brain a Computer? [

11] are questions that are fundamental to the evolution of AI. We frame AI systems in a layered triad analogous to the relationship between body, brain, and mind in philosophical terms. The Brain represents the data-driven learners (neural networks, probabilistic models) that process inputs and produce candidate outputs. The Body represents the machine’s interface to the world – sensors, actuators, and also any fixed rule-based code (the deterministic machinery). The Mind is the overarching reasoning and regulating entity that interprets the Brain’s outputs, applies judgment, and decides actions by the machine. This triad offers a clear conceptual separation: the Body provides signals and actions, the Brain pro-vides patterns and predictions, and the Mind provides meaning, goals and their execution. By explicitly modeling these layers, we can address current shortcomings: today’s AI “brains” (LLMs, etc.) have raw power but no self-aware mind to guide them. Our architecture adds that missing mindful layer on top of existing AI, providing what Kant might call the understanding and judgment to complement the mechanical processing of a brain. This also aligns with the idea that true intelligence requires integrating multiple perspectives – the physical (Body), the computational (Brain), and the rational/ethical (Mind).

Hegelian Dialectic of AI Evolution: We interpret the trajectory of AI through a Hegelian lens of thesis, antithesis, and synthesis [

12]. The thesis has been human cognition as we know it – limited by biology but rich in common sense and values. The antithesis is machine intelligence as a brute-force simulation – enormously scalable and precise, yet lacking understanding and moral grounding. The syn-thesis, we argue, is a Society of Minds: a unification where human and machine minds interact in a shared system, combining their strengths while resolving their respective weaknesses. In practical terms, this means AI development should transition from humans and AIs working separately to humans and AIs working together in a principled way. Our framework explicitly enables such collaboration: human minds can be part of the society (e.g. a human expert might function as one “mind” in a problem-solving network), and the AI minds are designed to communicate in human-understandable terms (through explanations and dialogues) rather than operate opaquely. This dialectical progression also under-scores why a Society of Minds is timely: it addresses the current tension between the incredible capability of AI (antithesis) and the urgent need for control and meaning (thesis) by synthesizing a new paradigm where control is achieved through interaction and transparency.

“Mindful Machines” – An Evolved End-State: We view Mindful Machines as an achievable the goal of the proposed paradigm. A Mindful Machine is not characterized by sheer speed or the size of its model, but by qualities of memory, reasoning, self-regulation, and self-awareness of its limits. It is an AI that remembers context over long periods, that can reason through novel problems, that regulates its own behavior according to ethical principles, and that knows when to act, when to ask for help, or when to refrain from action. This stands in stark contrast to today’s systems which are often “superficially fluent but clueless underneath” [

13]. To achieve this, the Society of Minds design includes a graph-structured memory as a shared knowledge store, enabling persistent context and collective learning. All interactions between minds update this memory graph, which acts like an evolving knowledge base the society can draw on – thereby giving the machine a form of long-term memory and continuity that typical neural networks lack. Additionally, the multi-mind setup means the machine can deliberate: multiple minds can debate a question or plan, yielding reasoning that is dialogical (many viewpoints considered) and discernible (steps can be traced). The result is an AI that behaves less like an “oracle” spitting out answers and more like a wise committee that can show its work. These Mindful Machines, we believe, would be safer and more reliable by design – they don’t just produce answers, they produce explanations, justifications, and safeguards as part of their output. In essence, the Society of Minds approach shifts the metric of progress from raw performance (e.g. benchmark scores) to coherent understanding and trustworthiness.

3.2. Implications: So What?

Why does this Society of Minds paradigm matter, and how we stand to benefit? We highlight several broad implications across conceptual, societal, and practical dimensions:

Conceptual Leap: This framework shifts the AI discourse from purely optimizing performance metrics to fostering relational understanding. It reframes AI progress not as a race for a single all-powerful model, but as the development of ecosystems of intelligent agents that learn to reason together. In doing so, it breaks the mold of thinking of intelligence as residing in one head (or one model), instead positioning intelligence as an emergent property of a network of interactions.

Societal Value: By leveraging many minds, our approach offers a pathway to overcome the stagnation of human cognition in the face of accelerating machine capabilities. Rather than AI competing against humans, a Society of Minds is inherently a partnership model: it ensures that machine intelligence augments human intelligence, working with us in a transparent dialogue. This could help prevent scenarios where AI grows incomprehensible or uncontrollable – instead, humans remain in the loop as part of the society, and the combined system can tackle problems neither could solve alone.

Organizational Impact: Practically, the Society of Minds reframes AI as a strategic operating system for organizations. Decision-making in complex domains (enterprise strategy, scientific R&D, governance) can be supported by a council of AI minds with different expertise, much like a diverse team of advisors. This means decisions are informed by multiple perspectives (financial, ethical, technical, human impact) all generated in tandem by the AI society powered by Mindful Machines. The outcome is a more robust and well-rounded analysis, reducing single-point failures in corporate or policy choices. In short, AI becomes less of a monolithic tool and more of a distributed, dialogical process embedded in organizational workflows.

Ethics Reinvigorated: Our paradigm embeds ethical deliberation into the fabric of AI systems. Instead of relying solely on external compliance or post-hoc fixes, the Society of Minds has moral checks inherently through its multi-mind governance. This reframes the AI alignment problem: alignment is no longer just tuning a dingle model’s behavior, but designing a society in which unethical proposals are caught and corrected by other members. It mirrors how pluralistic democratic societies prevent extreme actions through debate and checks, rather than trusting any one actor blindly. Such an AI would be easier to audit and regulate, since it produces explanations and divides power among units. It aligns closely with emerging principles of ethical AI by design – moving from external oversight to internal conscience.

Philosophical Depth: By drawing on philosophical insights (Kant’s categories [

14], Wittgenstein’s language-games [

15], Habermas’s communicative rationality [

16]), this framework grounds technical AI development in deeper theories of knowledge and meaning. Intelligence here is not just number-crunching; it’s relational, conversational, and normative. This helps bridge the gap between engineering and humanities in AI discourse. For instance, Wittgenstein argued that understanding is inherently social and contextual – our Society of Minds explicitly operationalizes that idea by requiring AI minds to negotiate meaning with each other and with humans. Habermas emphasized the importance of reason-giving in legitimate dialogue – our architecture ensures every decision can be questioned and explained. In effect, the paradigm connects AI’s future to enduring human questions about how knowledge is created, shared, and validated.

Towards a Sustainable Future: We define “Mindful Machines” as AI systems [

5,

10] that are transparent, ethical, and collaborative by design – a stark contrast to the opaque, unyielding AI systems that dominate today. Embracing a Society of Minds vision steers AI development onto a more sustainable trajectory: one where progress is measured not just by capability, but by controllability and trustworthiness. It offers a hopeful vision where increasing machine intelligence does not equate to increasing risk, because greater capability is coupled with greater in-ternal governance and wisdom. As AI pioneer Gary Marcus has implored, we should demand “a better form of AI” – one that earns our trust by how it operates, not just by its results. The Society of Minds paradigm is a direct response to that demand, suggesting that the path to wise AI is through constructing systems that inherently respect diverse perspectives, self-correct, and remain open to human guidance.

4. Discussion

The history of AI can be read as a succession of architectural experiments—each promising, each partial. Symbolic AI built transparent but brittle structures [

8]. Deep learning scaled fluency and perception [

17], but at the cost of opacity and reliability. Agentic systems introduced modularity and autonomy, but coordination remains fragile [

18]. The Society of Minds does not discard these efforts but sublates them into a higher-order civic plan: modules, networks, and agents knit together through communication, critique, and governance. It is less about spectacle than about dialogue, less about monolithic performance than about relational coherence.

4.1. Explanations, Epistemology, and Emergent Safety

If knowledge is to endure, it must be tested in public, not whispered in closed chambers. A Society of Minds requires its agents—human and machine—to explain themselves, to give reasons that others may examine, contest, or refine. In this, the architecture mirrors Karl Popper’s faith in falsifiability [

19] and David Deutsch’s insistence that progress is born of criticism [

20,

21]. Each exchange within the society is a miniature forum: conjecture offered, rebuttal posed, revision demanded. Knowledge is not locked in vectors of weight, but inscribed in arguments that can be retraced and repaired. The scaffolding of this discourse is technical as well as philosophical: graph-structured memory to anchor provenance, digital genomes to preserve lineage, governance protocols to enforce accountability. As Mikkilineni [

10,

22] observes, the contrast between biological and artificial systems is not merely one of scale but of structure. Biological minds regulate themselves, weave memory into lived experience, and expand knowledge through interaction; machines today, by contrast, remain pattern processors without autopoietic grounding or associative recall. His proposal of “digital genome”–like structures, where knowledge is contextualized and updated through lineage and dialogue, dovetails with the Society of Minds framework. It reinforces the point that knowledge must be both structured and social: not inert data, but discourse tested, criticized, and extended through interaction among minds—human and artificial alike. The design echoes Mark Burgin’s General Theory of Information [

23,

24,

25,

26], in which information is not inert record but living fabric—hierarchical, networked, open to growth. In this civic model, explanation is not ornament but requirement. Safety emerges not from constraint alone but from conversation: every claim must survive the critique of its peers. The model treats knowledge acquisition as more passive (receiving information) than proactive.

4.2. Toward an Integrative AI Paradigm

What emerges from this synthesis is not a refinement of existing tools but a new kind of polity. General intelligence may prove not to reside in a singular cathedral at all, but in the bustling agora between many smaller shrines of competence. The genius machine—solitary, oracular, self-sufficient—yields to a society whose resilience lies in plurality, whose wisdom arises from contention. In this vision, benchmarks are rewritten. Success is measured not only in narrow victories at task X, but in the ability to negotiate disagreement, to explain choices, to detect when an action strains against ethics or reason.

Our emphasis is on active reasoning, criticism, and agency could contrast with any passive models assumed in GTI discussions — which may assume that updating happens by exposure rather than by questioning, choosing, or rejecting. Building blocks such as digital genomes, oracles, and graph memory, when implemented in AI, can achieve autopoiesis and create associative memory – emulating human thinking and understanding [

7].

The Society of Minds is messy, perhaps, but like any city, its vitality lies in its intersections, its disputes, its capacity to absorb the new without unraveling the old. It is an architecture designed for growth, not perfection. To pursue this path is to accept that intelligence worth trusting will be born not of monologue but of dialogue, not of spectacle but of sustained, self-correcting conversation

5. Conclusions

Artificial intelligence stands at a crossroads. We have built machines of dazzling capability but shallow grounding—systems that simulate understanding while faltering at reasoning and explanation. The warnings of Marcus [

2], LeCun [

3], and Hinton [

4] converge here: scale alone cannot deliver mindful intelligence. The Society of Minds offers an alternative: plural systems where minds critique minds, where explanations are demanded, where governance mirrors the checks and balances of human institutions.

5.1. The Implications of the Society of Minds Paradigm

This paradigm does not promise perfection. It will err and quarrel, but unlike a solitary black box, it contains the means of its own correction. Its resilience lies in plurality, its wisdom in dialogue. Practical prototypes—from enterprise strategy to medical diagnostics—suggest its feasibility, while historical analogies (from multi-core processors to microservices) remind us that complexity, once feared, can be mastered.

The challenge ahead is to formalize governance protocols, metrics for dialogical intelligence, and efficiency benchmarks that make this architecture scalable. Yet humanity’s greatest institutions—science, law, democracy—emerged not from sup-pression of plurality but from its cultivation. AI must follow the same path.

To embrace a Society of Minds is to renounce the fantasy of a solitary genius machine and instead imagine intelligence as civic, plural, and dialogical. Technically, this means abandoning the monolith in favor of a federation: modular intelligences, interoperable by design, each adding its perspective to the deliberation. Such a shift mirrors the open-source ethos—progress as a mosaic of contributions, not a monopoly of one cathedral. It promises faster innovation and more resilient systems, be-cause in a society, failures can be corrected, dissent can sharpen truth, and no single agent holds unchecked power.

Governance, too, acquires a new contour. Inside the system, governance means embedding checks and balances—minds that audit, minds that veto, minds that ex-plain. Outside, it means AI that welcomes scrutiny, because its internal discourse produces explanations before it delivers conclusions. A Society of Minds, by design, acknowledges fallibility and subjects itself to critique. It is a humility machine, not an oracle.

Philosophically, this paradigm honors old insights with new architecture. Kant taught us that understanding is not given but imposed [

14], Wittgenstein that meaning is forged in use [

15], Habermas that legitimacy lies in the force of the better argument [

16]. The Society of Minds operationalizes these truths: knowledge must be tested, explanations must be shared, dialogue must be the medium of progress. This is intelligence not as spectacle, but as conversation.

Building such systems will require patience and pluralism in our own institutions. Researchers must resist the temptation to crown a single paradigm as sovereign. Companies must learn to share responsibility across interoperable modules rather than hoard power in proprietary fortresses. Policymakers must regulate for dialogue and transparency, not simply for efficiency. The challenge is not merely technical but cultural: to create a research and governance ecosystem that mirrors the very society of minds we seek to engineer.

5.2. The Choice Before Us

The history of intelligence, natural or artificial, is not the history of solitary genius but of communities. Human civilization advanced because minds related, argued, collaborated, and corrected each other’s errors. To build machines that mimic intelligence without embedding this social fabric is to automate the autocratic thinker - in silicon. The Society of Minds paradigm presents a stronger foundation: intelligence as dialogue, progress as critique, wisdom as a property of the many.

We close with a call: let us build not solitary titans but civic minds. Let us insist on systems that deliberate, explain, and submit to critique. Let us build not just faster machines, but wiser ones—minds in dialogue with each other, with us, and with the sustainable future we seek to create.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.M; methodology, R.M.; All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The Author R. M acknowledges Dr. Judith Lee, Director of the Center for Business Innovation for support and continued encouragement.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Minsky, M. *The Society of Mind*; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1986.

- Marcus, G. Deep Learning: A Critical Appraisal. *arXiv* 2018, arXiv:1801.00631. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/1801.00631 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- LeCun, Y. A Path Towards Autonomous Machine Intelligence. *Open Review* 2022. Available online: https://openreview.net/forum?id=BZ5a1r-kVsf (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Hinton, G. The Future of Artificial Intelligence: Opportunities and Risks. *Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A* 2023, 381, 20220049. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilineni, R. General Theory of Information and Mindful Machines. *Proceedings* 2025, 126(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Newell, A.; Simon, H.A. GPS, a Program that Simulates Human Thought. In *Computers and Thought*; Feigenbaum, E., Feldman, J., Eds.; McGraw-Hill: New York, NY, USA, 1963; pp. 279–293.

- Mikkilineni, R. General Theory of Information and Mindful Machines. *Proceedings* 2025, 126(1), 3. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilineni, R. Mark Burgin’s Legacy: The General Theory of Information, the Digital Genome, and the Future of Machine Intelligence. *Philosophies* 2023, 8, 107. [CrossRef]

- Kelly, W.P.; Coccaro, F.; Mikkilineni, R. General Theory of Information, Digital Genome, Large Language Models, and Medical Knowledge-Driven Digital Assistant. *Computer Sciences & Mathematics Forum* 2023, 8(1), 70. [CrossRef]

- Mikkilineni, R. A New Class of Autopoietic and Cognitive Machines. *Information* 2022, 13, 24. [CrossRef]

- TFPIS. What Is a Computer, and Is the Brain a Computer? 2024. Available online: https://tfpis.com/2024/04/21/what-is-a-computer-and-is-the-brain-a-computer/ (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Hegel, G.W.F. *Phenomenology of Spirit*; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 1977 (orig. 1807).

- OpenAI. GPT-4 Technical Report. *arXiv* 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. Available online: https://arxiv.org/abs/2303.08774 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Kant, I. *Critique of Pure Reason*; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1998 (orig. 1781).

- Wittgenstein, L. Philosophical Investigations; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1953.

- Habermas, J. *The Theory of Communicative Action*, Volume 1; Beacon Press: Boston, MA, USA, 1984.

- Rumelhart, D.E.; Hinton, G.E.; Williams, R.J. Learning Representations by Back-Propagating Errors. *Nature* 1986, 323, 533–536. [CrossRef]

- Nisa, U., Shirazi, M., Saip, M. A., & Mohd Pozi, M. S. (2025). Agentic AI: The age of reasoning—A review. Journal of Automation and Intelligence. [CrossRef]

- Popper, K. *Conjectures and Refutations: The Growth of Scientific Knowledge*; Routledge: London, UK, 1963.

- Deutsch, D. *The Fabric of Reality*; Penguin: London, UK, 1997.

- Deutsch, D. (2011). The beginning of infinity: Explanations that transform the world (1st American ed.). Viking.

- Burgin, M.; Mikkilineni, R. On the Autopoietic and Cognitive Behavior of Digital Genomes. *EasyChair Preprint* No. 6261, 2021. Available online: https://easychair.org/preprints/preprint_download/hRr2 (accessed on 24 September 2025).

- Burgin, M. *Theory of Information: Fundamentality, Diversity and Unification*; World Scientific: Singapore, 2010. [CrossRef]

- Burgin, M. Theory of Knowledge: Structures and Processes; World Scientific Books: Singapore, 2016.

- Burgin, M. Structural Reality; Nova Science Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2012.

- Burgin, M. Triadic Automata and Machines as Information Transformers. Information 2020, 11, 102. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).