Submitted:

20 July 2025

Posted:

22 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

2.1. Graph Representations and Notation

2.2. Message Passing Neural Networks

2.3. Transformer-Based Language Models

2.4. Comparative Representational Capabilities

3. Comparative Analysis of GNNs and LLMs for Graph-Based Tasks

| Aspect | Graph Neural Networks (GNNs) | Large Language Models (LLMs) |

|---|---|---|

| Input Representation | Native graph structure (adjacency matrix, edge lists) | Sequentialized or textual graph encodings (e.g., node triples, graph prompts) |

| Architecture Bias | Local and relational inductive bias via message passing | Global attention with soft inductive bias to sequence and co-occurrence statistics |

| Scalability | Efficient for sparse and localized graphs; limited by neighborhood explosion in deep GNNs | Highly scalable with sufficient hardware; cost grows quadratically with input length |

| Expressivity | Limited by the 1-WL test; extensions include higher-order GNNs | Capable of learning high-order dependencies; lacks explicit graph inductive priors |

| Pretraining | Domain-specific pretraining schemes (e.g., node masking, graph contrastive learning) | Trained on massive text corpora; general-purpose representations can be repurposed |

| Adaptability to Tasks | Requires task-specific architecture design and training | Zero-shot and few-shot learning enabled by prompting and in-context learning |

| Explainability | More interpretable due to structured graph flow and neighborhood influence | Difficult to interpret due to dense attention and token-level reasoning |

| Integration with External Knowledge | Can directly incorporate structured knowledge graphs as input | Often needs grounding via knowledge injection, retrieval, or augmented prompts |

| Fine-tuning Overhead | Lightweight and efficient on small datasets | Expensive and often impractical without parameter-efficient methods |

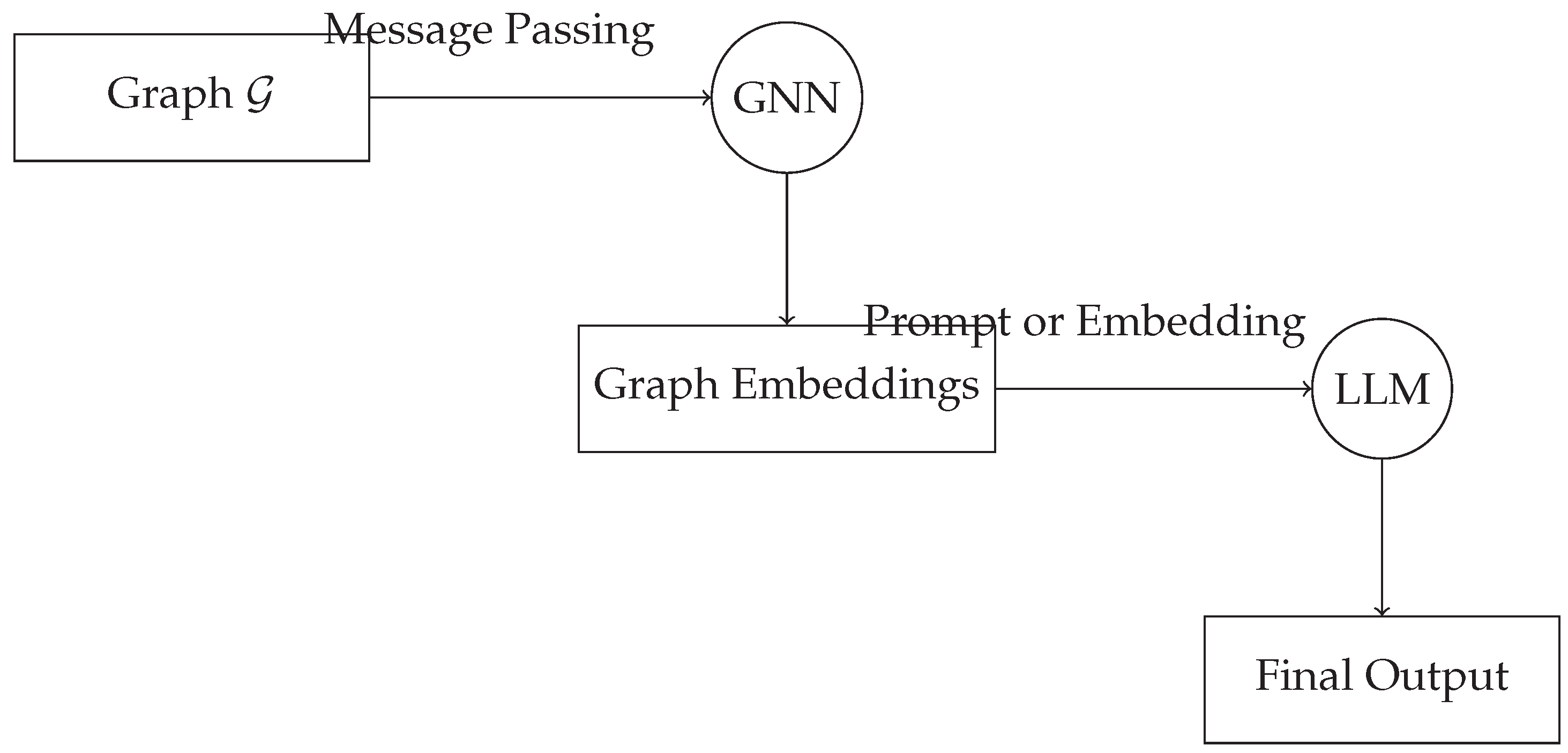

4. Hybrid Architectures: Bridging GNNs and LLMs

5. Applications in the Wild

6. Challenges and Open Problems

7. Future Directions

8. Conclusion

References

- N. M. Kriege. Comparing Graphs: Algorithms & Applications. Phd thesis, TU Dortmund University, 2015.

- Hisashi Kashima, Koji Tsuda, and Akihiro Inokuchi. Marginalized kernels between labeled graphs. In ICLR, pages 321–328, 2003a.

- Christos Louizos, Uri Shalit, Joris M. Mooij, David A. Sontag, Richard S. Zemel, and Max Welling. Causal effect inference with deep latent-variable models. In NeurIPS, 2017.

- A. Schrijver. Theory of Linear and Integer programming. 1986.

- Yixuan He, Xitong Zhang, Junjie Huang, Benedek Rozemberczki, Mihai Cucuringu, and Gesine Reinert. Pytorch geometric signed directed: a software package on graph neural networks for signed and directed graphs. In Learning on Graphs Conference, pages 12–1. PMLR, 2024.

- Lin Ni, Sijie Wang, Zeyu Zhang, Xiaoxuan Li, Xianda Zheng, Paul Denny, and Jiamou Liu. Enhancing student performance prediction on learnersourced questions with sgnn-llm synergy. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, volume 38, pages 23232–23240, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Chuizheng Meng, Sam Griesemer, Defu Cao, Sungyong Seo, and Yan Liu. When physics meets machine learning: A survey of physics-informed machine learning. Machine Learning for Computational Science and Engineering, 1(1):1–23, 2025. [CrossRef]

- Qian Huang, Hongyu Ren, Peng Chen, Gregor Kržmanc, Daniel Zeng, Percy S Liang, and Jure Leskovec. Prodigy: Enabling in-context learning over graphs. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36:16302–16317, 2023.

- U-V Marti and Horst Bunke. The iam-database: an english sentence database for offline handwriting recognition. International journal on document analysis and recognition, 5:39–46, 2002. [CrossRef]

- Christopher Morris, Gaurav Rattan, Sandra Kiefer, and Siamak Ravanbakhsh. SpeqNets: Sparsity-aware permutation-equivariant graph networks. In ICLR, pages 16017–16042, 2022.

- Harold Abelson, Gerald Jay Sussman, and Julie Sussman. Structure and Interpretation of Computer Programs, MIT Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts, 1985. [CrossRef]

- Rex Ying, Ruining He, Kaifeng Chen, Pong Eksombatchai, William L. Hamilton, and Jure Leskovec. Graph convolutional neural networks for web-scale recommender systems. In Proceedings of the 24th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery & Data Mining, KDD 2018, London, UK, August 19-23, 2018, pages 974–983, 2018.

- Giovanni Da San Martino, Nicolò Navarin, and Alessandro Sperduti. A tree-based kernel for graphs. In Proceedings of the Twelfth SIAM International Conference on Data Mining, Anaheim, California, USA, April 26-28, 2012, pages 975–986, 2012.

- Alvaro Arroyo, Bruno Scalzo, Ljubiša Stanković, and Danilo P Mandic. Dynamic portfolio cuts: A spectral approach to graph-theoretic diversification. In ICASSP 2022-2022 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), pages 5468–5472. IEEE, 2022.

- Filip Ekström Kelvinius, Dimitar Georgiev, Artur Toshev, and Johannes Gasteiger. Accelerating molecular graph neural networks via knowledge distillation. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 36:25761–25792, 2023.

- Gal Vardi. On the implicit bias in deep-learning algorithms. Communications of the ACM, 66(6):86–93, 2023. [CrossRef]

- Ze Liu, Yutong Lin, Yue Cao, Han Hu, Yixuan Wei, Zheng Zhang, Stephen Lin, and Baining Guo. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, pages 10012–10022, 2021.

- Christopher Morris, Floris Geerts, Jan Tönshoff, and Martin Grohe. WL meet VC. In ICML, 2023.

- Jake Topping, Francesco Di Giovanni, Benjamin Paul Chamberlain, Xiaowen Dong, and Michael M Bronstein. Understanding over-squashing and bottlenecks on graphs via curvature. In International Conference on Learning Representations, 2021.

- M. Grohe, P. Schweitzer, and D. Wiebking. Deep Weisfeiler Leman. arXiv preprint, 2020.

- Dexiong Chen, Leslie O’Bray, and Karsten Borgwardt. Structure-aware transformer for graph representation learning. In International conference on machine learning, pages 3469–3489. PMLR, 2022.

- Benjamin Chamberlain, James Rowbottom, Davide Eynard, Francesco Di Giovanni, Xiaowen Dong, and Michael Bronstein. Beltrami flow and neural diffusion on graphs. Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, 34:1594–1609, 2021.

- Tao Lei, Wengong Jin, Regina Barzilay, and Tommi S. Jaakkola. Deriving neural architectures from sequence and graph kernels. In ICLR, pages 2024–2033, 2017a.

- J. Klicpera, F. Becker, and S. Günnemann. Gemnet: Universal directional graph neural networks for molecules. arXiv preprint, 2021.

- Simon S. Du, Kangcheng Hou, Ruslan Salakhutdinov, Barnabás Póczos, Ruosong Wang, and Keyulu Xu. Graph neural tangent kernel: Fusing graph neural networks with graph kernels. In NeurIPS 32: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, NeurIPS 2019, December 8-14, 2019, Vancouver, BC, Canada, pages 5724–5734, 2019.

- Tianjin Huang, Tianlong Chen, Meng Fang, Vlado Menkovski, Jiaxu Zhao, Lu Yin, Yulong Pei, Decebal Constantin Mocanu, Zhangyang Wang, Mykola Pechenizkiy, and Shiwei Liu. You can have better graph neural networks by not training weights at all: Finding untrained GNNs tickets. In LoG, 2022.

- Ryan, L. Murphy, Balasubramaniam Srinivasan, Vinayak A. Rao, and Bruno Ribeiro. Janossy pooling: Learning deep permutation-invariant functions for variable-size inputs. In ICLR, 2019.

- Xiaoxin He, Xavier Bresson, Thomas Laurent, Adam Perold, Yann LeCun, and Bryan Hooi. Harnessing explanations: Llm-to-lm interpreter for enhanced text-attributed graph representation learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:2305.19523, arXiv:2305.19523, 2023.

- Francesco Di Giovanni, T Konstantin Rusch, Michael M Bronstein, Andreea Deac, Marc Lackenby, Siddhartha Mishra, and Petar Veličković. How does over-squashing affect the power of gnns? arXiv:2306.03589, arXiv:2306.03589, 2023.

- Haorui Wang, Haoteng Yin, Muhan Zhang, and Pan Li. Equivariant and stable positional encoding for more powerful graph neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2203.00199, arXiv:2203.00199, 2022.

- Beatrice Bevilacqua, Moshe Eliasof, Eli A. Meirom, Bruno Ribeiro, and Haggai Maron. Efficient subgraph GNNs by learning effective selection policies. arXiv preprint, abs/2310.20082, 2023.

- V. M. Zolotarev. One-dimensional stable distributions. Providence, RI, 1986.

- T. Gärtner. Kernels for Structured Data. PhD thesis, University of Bonn, 2005.

- Pablo Barceló, Egor V. Kostylev, Mikaël Monet, Jorge Pérez, Juan L. Reutter, and Juan Pablo Silva. The logical expressiveness of graph neural networks. In ICLR, 2020.

- Songgaojun Deng, Shusen Wang, Huzefa Rangwala, Lijing Wang, and Yue Ning. Graph message passing with cross-location attentions for long-term ili prediction. arXiv preprint arXiv:1912.10202, arXiv:1912.10202, 2019.

- Andrea Cini, Daniele Zambon, and Cesare Alippi. Sparse graph learning from spatiotemporal time series. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 24(242):1–36, 2023.

- He Zhang, Bang Wu, Xingliang Yuan, Shirui Pan, Hanghang Tong, and Jian Pei. Trustworthy graph neural networks: Aspects, methods and trends. arXiv preprint arXiv:2205.07424, arXiv:2205.07424, 2022.

- Ben Day, Cătălina Cangea, Arian R Jamasb, and Pietro Liò. Message passing neural processes. arXiv preprint arXiv:2009.13895, arXiv:2009.13895, 2020.

- Mitchell Black, Zhengchao Wan, Amir Nayyeri, and Yusu Wang. Understanding oversquashing in gnns through the lens of effective resistance. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 2528–2547. PMLR, 2023.

- N. Kriege, M. N. Kriege, M. Neumann, K. Kersting, and M. Mutzel. Explicit versus implicit graph feature maps: A computational phase transition for walk kernels. In IEEE International Conference on Data Mining, pages 881–886, 2014.

- Hisashi Kashima, Koji Tsuda, and Akihiro Inokuchi. Marginalized kernels between labeled graphs. In ICLR, pages 321–328, 2003b.

- Vijay Prakash Dwivedi, Anh Tuan Luu, Thomas Laurent, Yoshua Bengio, and Xavier Bresson. Graph neural networks with learnable structural and positional representations. arXiv preprint arXiv:2110.07875, arXiv:2110.07875, 2021.

- Fredrik, D. Johansson, Vinay Jethava, Devdatt P. Dubhashi, and Chiranjib Bhattacharyya. Global graph kernels using geometric embeddings. In ICLR, pages 694–702, 2014.

- Chaoqi Yang, Ruijie Wang, Shuochao Yao, Shengzhong Liu, and Tarek Abdelzaher. Revisiting over-smoothing in deep gcns. arXiv preprint arXiv:2003.13663, arXiv:2003.13663, 2020.

- M. Wang, L. M. Wang, L. Yu, D. Zheng, Q. Gan, Y. Gai, Z. Ye, M. Li, J. Zhou, Q. Huang, C. Ma, Z. Huang, Q. Guo, H. Zhang, H. Lin, J. Zhao, J. Li, A. J. Smola, and Z. Zhang. Deep graph library: Towards efficient and scalable deep learning on graphs. arXiv preprint.

- Zaïd Harchaoui and Francis R. Bach. Image classification with segmentation graph kernels. In 2007 IEEE Computer Society Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR 2007), 18-23 June 2007, Minneapolis, Minnesota, USA, 2007.

- Alan Thomas, Robert Gaizauskas, and Haiping Lu. Leveraging llms for post-ocr correction of historical newspapers. In Proceedings of the Third Workshop on Language Technologies for Historical and Ancient Languages (LT4HALA)@ LREC-COLING-2024, pages 116–121, 2024.

- Francesco Di Giovanni, T. Konstantin Rusch, Michael Bronstein, Andreea Deac, Marc Lackenby, Siddhartha Mishra, and Petar Veličković. How does over-squashing affect the power of GNNs? Transactions on Machine Learning Research, 2024. ISSN 2835-8856.

- Xavier Glorot and Yoshua Bengio. Understanding the difficulty of training deep feedforward neural networks. In AISTATS, pages 249–256, 2010.

- Bohang Zhang, Shengjie Luo, Liwei Wang, and Di He. Rethinking the expressive power of Gnns via graph biconnectivity. arXiv preprint.

- Liang Yang, Weihang Peng, Wenmiao Zhou, Bingxin Niu, Junhua Gu, Chuan Wang, Yuanfang Guo, Dongxiao He, and Xiaochun Cao. Difference residual graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 30th ACM international conference on multimedia, pages 3356–3364, 2022.

- Matteo Togninalli, M. Elisabetta Ghisu, Felipe Llinares-López, Bastian Rieck, and Karsten M. Borgwardt. Wasserstein weisfeiler-lehman graph kernels. In NeurIPS 32: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, NeurIPS 2019, December 8-14, 2019, Vancouver, BC, Canada, pages 6436–6446, 2019.

- Keyulu Xu, Mozhi Zhang, Stefanie Jegelka, and Kenji Kawaguchi. Optimization of graph neural networks: Implicit acceleration by skip connections and more depth. In ICLR, 2021.

- Tao Lei, Wengong Jin, Regina Barzilay, and Tommi S. Jaakkola. Deriving neural architectures from sequence and graph kernels. In ICLR, pages 2024–2033, 2017b.

- D. Rogers and M. Hahn. Extended-connectivity fingerprints. Journal of Chemical Information and Modeling, (5):742–754, 2010.

- Matthias Fey, Jan Eric Lenssen, Frank Weichert, and Heinrich Müller. Splinecnn: Fast geometric deep learning with continuous b-spline kernels. In 2018 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, CVPR 2018, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, June 18-22, 2018, pages 869–877, 2018.

- D. Flam-Shepherd, T. D. Flam-Shepherd, T. Wu, P. Friederich, and A. Aspuru-Guzik. Neural message passing on high order paths. arXiv preprint, 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafal Karczewski, Amauri H. Souza, and Vikas Garg. On the generalization of equivariant graph neural networks. In ICML, 2024.

- Pinar Yanardag and S. V., N. Vishwanathan. In Deep graph kernels. In Proceedings of the 21th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, Sydney, NSW, Australia, 2015, pages 1365–1374, 2015., August 10-13.

- Nicolás Serrano, Francisco Castro, and Alfons Juan. The rodrigo database. In LREC, pages 19–21, 2010.

- Jinhyeok Choi, Heehyeon Kim, Minhyeong An, and Joyce Jiyoung Whang. Spot-mamba: Learning long-range dependency on spatio-temporal graphs with selective state spaces. arXiv preprint arXiv:2406.11244, arXiv:2406.11244, 2024.

- Chanyoung Chung, Jaejun Lee, and Joyce Jiyoung Whang. Representation learning on hyper-relational and numeric knowledge graphs with transformers. In KDD, 2023.

- T. Maehara and H. NT. A simple proof of the universality of invariant/equivariant graph neural networks. arXiv preprint.

- K. M. Borgwardt. Graph kernels. Phd thesis, Ludwig Maximilians University Munich, 2007.

- P. Indyk and R. Motwani. Approximate nearest neighbors: Towards removing the curse of dimensionality. In ACM Symposium on Theory of Computing, pages 604–613, 1998.

- Yue Wang, Yongbin Sun, Ziwei Liu, Sanjay E Sarma, Michael M Bronstein, and Justin M Solomon. Dynamic graph cnn for learning on point clouds. ACM Transactions on Graphics (tog), 38(5):1–12, 2019b. [CrossRef]

- Kenji Kawaguchi, Zhun Deng, Kyle Luh, and Jiaoyang Huang. Robustness implies generalization via data-dependent generalization bounds. In ICML, 2022.

- V. N. Vapnik and A. Chervonenkis. A note on one class of perceptrons. Avtomatika i Telemekhanika, 24(6):937–945, 1964.

- Judea Pearl. Causality 2002-2020 - introduction. In Hector Geffner, Rina Dechter, and Joseph Y. Halpern, editors, Probabilistic and Causal Inference: The Works of Judea Pearl, volume 36 of ACM Books, pages 393–398. ACM, 2022.

- Arnaud Casteigts, Paola Flocchini, Emmanuel Godard, Nicola Santoro, and Masafumi Yamashita. On the expressivity of time-varying graphs. Theoretical Computer Science, 590:27–37, 2015. [CrossRef]

- S. Shalev-Shwartz and S. Ben-David. Understanding Machine Learning: From Theory to Algorithms. 2014.

- Trang Pham, Truyen Tran, Dinh Q. Phung, and Svetha Venkatesh. Column networks for collective classification. In Proc. of AAAI, pages 2485–2491, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Wolfgang Maass. Bounds for the computational power and learning complexity of analog neural nets. SIAM Journal on Computing, 26(3):708–732, 1997. [CrossRef]

- J. Kazius, R. McGuire, and R. Bursi. Derivation and validation of toxicophores for mutagenicity prediction. Journal Medicinal Chemistry, (13):312–320, 2005. [CrossRef]

- Thomas N Kipf and Max Welling. Variational graph auto-encoders. arXiv preprint arXiv:1611.07308, arXiv:1611.07308, 2016.

- Yassine Zniyed, Thanh Phuong Nguyen, et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems, 36(3):4358–4370, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zeyu Zhang, Lu Li, Shuyan Wan, Sijie Wang, Zhiyi Wang, Zhiyuan Lu, Dong Hao, and Wanli Li. Dropedge not foolproof: Effective augmentation method for signed graph neural networks. In The Thirty-eighth Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems.

- D. Easley and J. Kleinberg. Networks, Crowds, and Markets: Reasoning About a Highly Connected World. Cambridge University Press, 2010.

- Sami Abu-El-Haija, Amol Kapoor, Bryan Perozzi, and Joonseok Lee. N-gcn: Multi-scale graph convolution for semi-supervised node classification. In uncertainty in artificial intelligence, pages 841–851. PMLR, 2020.

- Nesreen K. Ahmed, Theodore L. Willke, and Ryan A. Rossi. Estimation of local subgraph counts. In <italic>2016 IEEE International Conference on Big Data, BigData 2016, Washington DC, USA, December 5-8, 2016, pages 586–595, 2016.

- Hongbin Pei, Bingzhe Wei, Kevin Chen-Chuan Chang, Yu Lei, and Bo Yang. Geom-gcn: Geometric graph convolutional networks. In ICLR, 2020.

- Siddhartha Mishra and T Konstantin Rusch. Enhancing accuracy of deep learning algorithms by training with low-discrepancy sequences. SIAM Journal on Numerical Analysis, 59(3):1811–1834, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Gauthier Guinet, Behrooz Omidvar-Tehrani, Anoop Deoras, and Laurent Callot. Automated evaluation of retrieval-augmented language models with task-specific exam generation. 2024.

- Joan Andreu Sánchez, Verónica Romero, Alejandro H Toselli, Mauricio Villegas, and Enrique Vidal. A set of benchmarks for handwritten text recognition on historical documents. Pattern Recognition, 94:122–134, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Grohe and M. Otto. Pebble games and linear equations. Journal of Symbolic Logic, 80(3):797–844, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Denis Lukovnikov and Asja Fischer. Improving breadth-wise backpropagation in graph neural networks helps learning long-range dependencies. In International Conference on Machine Learning, pages 7180–7191. PMLR, 2021.

- Zonghan Wu, Shirui Pan, Fengwen Chen, Guodong Long, Chengqi Zhang, and S Yu Philip. A comprehensive survey on graph neural networks. IEEE transactions on neural networks and learning systems, 32(1):4–24, 2020.

- Razvan Pascanu, Tomas Mikolov, and Yoshua Bengio. On the difficulty of training recurrent neural networks. In International conference on machine learning, pages 1310–1318. Pmlr, 2013.

- Brandon, M. Brandon M. Anderson, Truong-Son Hy, and Risi Kondor. Cormorant: Covariant molecular neural networks. In NeurIPS 32: Annual Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems 2019, NeurIPS 2019, December 8-14, 2019, Vancouver, BC, Canada, pages 14510–14519, 2019.

- A. Cardon and M. Crochemore. Partitioning a graph in O(|A|log2|V|). Theoretical Computer Science, (1):85 – 98, 1982.

- Pierre Mahé, Nobuhisa Ueda, Tatsuya Akutsu, Jean-Luc Perret, and Jean-Philippe Vert. Extensions of marginalized graph kernels. In ICLR, 2004.

- Floris Geerts and Juan L Reutter. Expressiveness and approximation properties of graph neural networks. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.04661, arXiv:2204.04661, 2022.

- N. Shervashidze, S. V. N. N. Shervashidze, S. V. N. Vishwanathan, T. H. Petri, K. Mehlhorn, and K. M. Borgwardt. Efficient graphlet kernels for large graph comparison. In AISTATS, pages 488–495, 2009.

- R. Paige and R.E. Tarjan. Three partition refinement algorithms. SIAM Journal on Computing, 1987. [CrossRef]

- Liangyue Li, Hanghang Tong, Yanghua Xiao, and Wei Fan. Cheetah: Fast graph kernel tracking on dynamic graphs. In Proceedings of the 2015 SIAM International Conference on Data Mining, Vancouver, BC, Canada, April 30 - May 2, 2015, pages 280–288, 2015.

- Jacob Bamberger, Federico Barbero, Xiaowen Dong, and Michael M. Bronstein. Bundle neural network for message diffusion on graphs. In The Thirteenth International Conference on Learning Representations, 2025.

- Atsushi Suzuki, Atsushi Nitanda, Taiji Suzuki, Jing Wang, Feng Tian, and Kenji Yamanishi. Tight and fast generalization error bound of graph embedding in metric space. In ICML, 2023.

- Jiawei Zhang and Lin Meng. Gresnet: Graph residual network for reviving deep gnns from suspended animation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1909.05729, arXiv:1909.05729, 2019.

- Barbara Hammer. Generalization ability of folding networks. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng., (2):196–206, 2001. [CrossRef]

- Antoine Bordes, Nicolas Usunier, Alberto García-Durán, Jason Weston, and Oksana Yakhnenko. Translating embeddings for modeling multi-relational data. In NeurIPS, 2013.

- M. Datar, N. M. Datar, N. Immorlica, P. Indyk, and V. S. Mirrokni. Locality-sensitive hashing scheme based on p-stable distributions. In ACM Symposium on Computational Geometry, pages 253–262, 2004.

- Guohao Li, Matthias Müller, Bernard Ghanem, and Vladlen Koltun. Training graph neural networks with 1000 layers. In ICML, 2021.

- Kenta Oono and Taiji Suzuki. Optimization and generalization analysis of transduction through gradient boosting and application to multi-scale graph neural networks. In NeurIPS, 2020.

- R. Levie, W. Huang, L. Bucci, M. Bronstein, and G. Kutyniok. Transferability of spectral graph convolutional neural networks. Journal of Machine Learning Research, 22(272):1–59, 2021.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).